Abstract

Background

The investigation of molecular mechanisms involved in polysaccharides and saponin metabolism is critical for genetic engineering of Polygonatum cyrtonema Hua to raise major active ingredient content. Up to now, the transcript sequences are available for different tissues of P. cyrtonema, a wide range scanning about temporal transcript at different ages’ rhizomes was still absent in P. cyrtonema.

Results

Transcriptome sequencing for rhizomes at different ages was performed. Sixty-two thousand six hundred thirty-five unigenes were generated by assembling transcripts from all samples. A total of 89 unigenes encoding key enzymes involved in polysaccharide biosynthesis and 56 unigenes encoding key enzymes involved in saponin biosynthesis. The content of total polysaccharide and total saponin was positively correlated with the expression patterns of mannose-6-phosphate isomerase (MPI), GDP-L-fucose synthase (TSTA3), UDP-apiose/xylose synthase (AXS), UDP-glucose 6-dehydrogenase (UGDH), Hydroxymethylglutaryl CoA synthase (HMGS), Mevalonate kinase (MVK), 2-C-methyl-D-erythritol 2,4-cyclodiphosphate synthase (ispF), (E)-4-hydroxy-3-methylbut-2-enyl-diphosphate synthase (ispG), 4-hydroxy-3-methylbut-2-enyl diphosphate reductase (ispH), Farnesyl diphosphate synthase (FPPS). Finally, a number of key genes were selected and quantitative real-time PCR were performed to validate the transcriptome analysis results.

Conclusions

These results create the link between polysaccharides and saponin biosynthesis and gene expression, provide insight for underlying key active substances, and reveal novel candidate genes including TFs that are worth further exploration for their functions and values.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12864-022-08421-y.

Keywords: Polygonatum cyrtonema Hua, Transcriptome, Polysaccharides, Saponins, Biosynthesis

Background

Polygonatum cyrtonema Hua (Asparagaceae) is a renowned traditional Chinese herb, and is also an edible plant. It has been widely applied for the treatment of many diseases such as dizziness, coughs et al. [1]. In Chinese Pharmacopoeia, “polygonati rhizoma” is often prescribed as the dried rhizome of Polygonatum cyrtonema Hua, Polygonatum kingianum Coll. et Hemsl and Polygonatum sibiricum Red [2]. A variety of medicinal effective ingredients have been isolated from “polygonati rhizoma” including Polysaccharides, saponins, flavonoids et al., and these effective ingredients exhibit a variety of vital pharmacological activities such as antioxidant, immunomodulatory, and anti-inflammatory et al. [3–5]. The previous research demonstrated the content of these effective ingredients including total polysaccharides and total saponins in P. cyrtonema plants changes with growth environment, cultivation technique, and growth years [6, 7]. This is of great significance for recognizing the biosynthesis and metabolism of polysaccharides and saponins.

Previously, in P. cyrtonema, researchers have revealed that polysaccharides were made of rhamnose, galactose, arabinose, mannose, glucose and fructose [6]. Partial researches verified that, in plant polysaccharides biosynthesis process, β-fructofuranosidase (sacA), hexokinase (HK), fructokinase (scrK), Phosphoglucomutase (PGM) is involved in the biosynthesis of NDP sugars [7–13]. Subsequently, abundant activated NDP-sugar precursors are added to polysaccharide residues promoting plant polysaccharides formation by a series of glycosyltransferase (GT) reactions [14]. In addition, some researches have revealed triterpene saponins biosynthesis pathway, and the number and expression level of partial key enzyme genes vary with the plant species [15–17].

A large volume of transcriptome, proteome and metabolomic have been executed in the post-genomic era [18]. Particularly, cause of the exact quantification of gene expression when lacking a reference genome, transcriptome sequencing (RNA-Seq) has been verified as the most useful, cost-effective technique for the research of metabolic pathways and function gene identification of effective ingredients [19].

In this study, we conducted a comprehensive analysis of the transcriptomes for different growth years rhizome of P. cyrtonema and identified plentiful candidate genes related to polysaccharide and triterpene saponins biosynthesis. The quality of our dataset was verified through quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR). Our results provide a foundation for future researches that tackle the molecular mechanisms of polysaccharide and triterpene saponins biosynthesis in this species.

Results

Total polysaccharide content of P. cyrtonema samples

We extracted polysaccharides from the rhizomes with different growing years of P. cyrtonema. Results reveal that total polysaccharide content increased with the developmental years, the value was highest in three-year rhizomes (16.004%), subsequently decreased from three-year rhizomes to four-year rhizomes. The lowest value emerges in one-year rhizomes (7.76%) (Additional file 1: Fig. S1).

Total saponin content of P. cyrtonema samples

Total saponin from the rhizomes with different growing years of P. cyrtonema were extracted. Results reveal that total saponin content increased with the developmental years, the value was highest in three-year rhizomes, subsequently decreased from three-year rhizomes to four-year rhizomes (Additional file 2: Fig. S2).

Illumina sequencing and de novo transcriptome assembly

The results of sequencing data quality were presented in Additional file 3: Table S1. All these data sets were characterized by Q30 ≥ 94.79%. A total of 62,635 unigenes were generated. These unigenes had a mean length of 1007.11 bp and an N50 value of 1456 bp; 34.14% (21,388) and 63.47% (39,752) of these exceeded 1000 bp and 500 bp in length, respectively (Additional file 4: Fig. S3).

Functional annotation and expression overview of unigenes

Out of the 62,635 unigenes identified in this analysis, 54.31, 38.90, 19.18, 31.14, 48.94, 35.40 and 31.66% unigenes were recorded as significant hits in the NR, SwissProt, KEGG, KOG, eggNOG, GO and Pfam databases, respectively (Table 1). Out of the 34,020 unigenes annotated in the NR database, 59.23, 7.53, 6.03, and 27.21% were mapped to the genes of Asparagus officinalis (Liliaceae), Elaeis guineensis (Arecaceae), Phoenix dactylifera (Palmae), and others, respectively (Additional file 5: Fig. S4). A total of 18,283 of these unigenes were then matched with one or more GO terms and comprise 50 functional groups (Additional file 6: Fig. S5). We found that ‘cellular process’ and ‘metabolic process’ were the most abundant categories within biological processes, while within the molecular function term, ‘binding’ and ‘catalytic activity’ were the most abundant.

Table 1.

Summary of P. cyrtonema unigenes annotated in seven public databases

| Database | Number annotated | Annotated unigene ratio (%) |

|---|---|---|

| NR | 34,020 | 54.31 |

| SwissProt | 24,367 | 38.90 |

| KEGG | 12,015 | 19.18 |

| KOG | 19,503 | 31.14 |

| eggNOG | 30,651 | 48.94 |

| GO | 22,170 | 35.40 |

| Pfam | 19,833 | 31.66 |

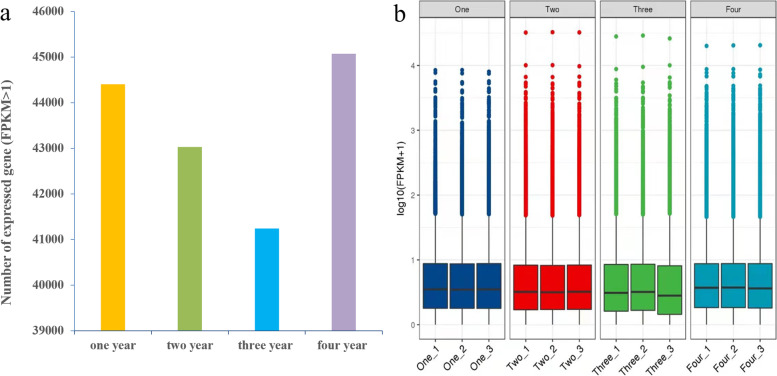

Unigenes with FPKM> 1 was counted in each tissue. The results of this comparison showed that average 44,403, 43,030, 41,245 and 45,076 unigenes were expressed in one-year, two-year, three-year, four-year rhizome samples, respectively (Fig. 1a). Gene expression level was highest in four-year rhizome compared with other rhizomes (Fig. 1b).

Fig. 1.

Expression profiles of genes in different years’s rhizome tissues of P. cyrtonema.a Distributions of average expressed unigenes (FPKM> 1) in the four samples. b Bloxplot of unigenes expressed in the four samples with three duplications, respectively. X-axis represents the different year’s rhizome tissues, and Y- axis shows the log10 (FPKM+ 1) values. Signifcant test of 12 samples is performed using multi-independent sample krukal-wallis test

Identification of genes involved in polysaccharide biosynthesis

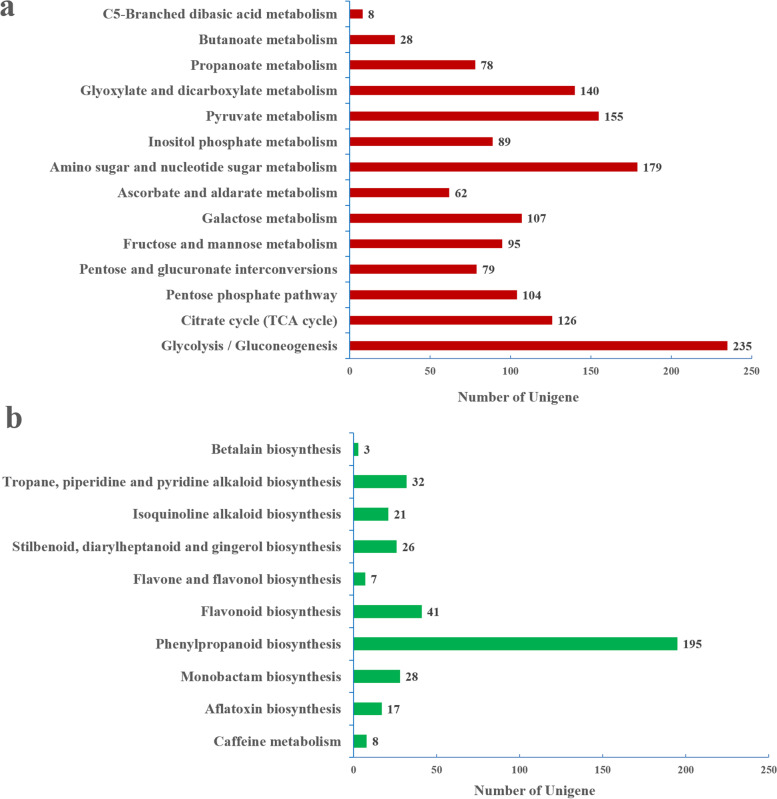

To comprehend the most noteworthy biological processes in P. cyrtonema, a total of 12,015 unigenes were annotated and allocated to 125 pathways (20 subcategories) (Additional file 7: Fig. S6 and Additional file 8: Table S2). The ‘carbohydrate metabolism’ subcategory involved in14 pathways with the largest number of unigenes (235) included glycolysis/gluconeogenesis metabolism. Besides, 588 unigenes were corresponding in polysaccharide biosynthesis pathways, including amino and nucleotide sugar metabolism, fructose and mannose metabolism, glycolysis/gluconeogenesis, and pentose and glucuronate interconversions (Fig. 2a). A total of 10 pathways were allocated to the biosynthesis of other secondary metabolites and the amplest unigenes within this set were marked within the phenylpropanoid biosynthesis pathway (Fig. 2b).

Fig. 2.

KEGG annotation of P. cyrtonema unigenes. a Pathway classifications for carbohydrate metabolism. b Pathway classification for the biosynthesis of other secondary metabolites

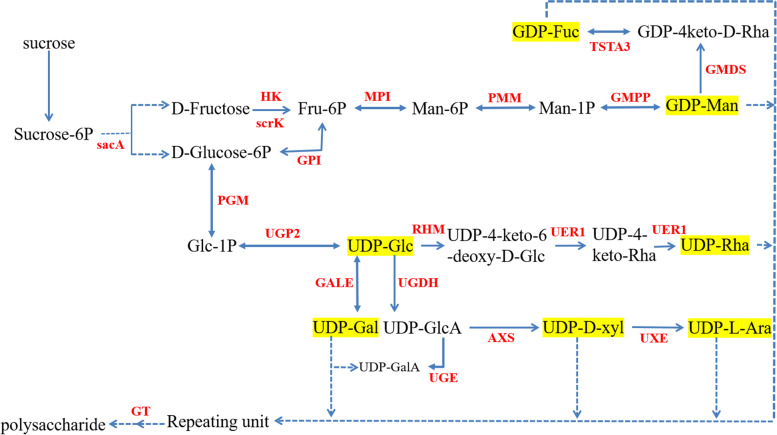

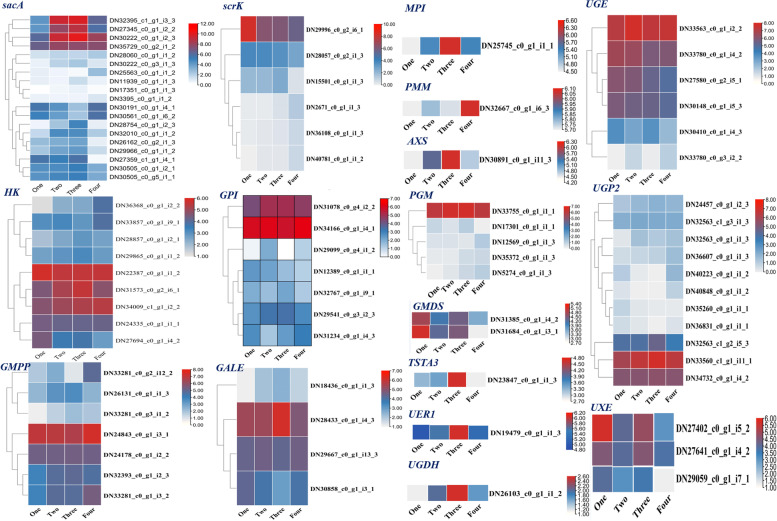

In order to enhance our understanding of polysaccharide biosynthesis, we annotated 274 unigenes involved in amino and nucleotide sugar metabolism (Ko00520) and fructose and mannose metabolism (Ko00051) pathways based on the KEGG database. A total of 89 unigenes encoding key enzymes, including 3,5-epimerase-4-reductase (UER1), UDP-glucose 4-epimerase (GALE), UDP-arabinose 4-epimerase (UXE) et al. (Table 2). These data enabled the identification of genes encoding enzymes involved in polysaccharide biosynthesis using the FPKM approach (Figs. 3 and 4).

Table 2.

Number of unigenes encoding key enzymes involved in polysaccharide biosynthesis in P. cyrtonema

| Enzyme name | EC number | Unigene number |

|---|---|---|

| beta-fructofuranosidase (sacA) | 3.2.1.26 | 19 |

| hexokinase (HK) | 2.7.1.1 | 9 |

| fructokinase (scrK) | 2.7.1.4 | 6 |

| mannose-6-phosphate isomerase (MPI) | 5.3.1.8 | 1 |

| phosphomannomutase (PMM) | 5.4.2.8 | 1 |

| mannose-1-phosphate guanylyltransferase (GMPP) | 2.7.7.13 | 7 |

| GDPmannose 4,6-dehydratase (GMDS) | 4.2.1.47 | 2 |

| GDP-L-fucose synthase (TSTA3) | 1.1.1.271 | 1 |

| glucose-6-phosphate isomerase (GPI) | 5.3.1.9 | 7 |

| phosphoglucomutase (PGM) | 5.4.2.2 | 5 |

| UTP--glucose-1-phosphate uridylyltransferase (UGP2) | 2.7.7.9 | 11 |

| UDP-glucose 4-epimeras (GALE) | 5.1.3.2 | 4 |

| UDP-glucose 4-epimerase (UGE) | 5.1.3.6 | 6 |

| UDP-glucose 6-dehydrogenase (UGDH) | 1.1.1.22 | 1 |

| UDP-apiose/xylose synthase (AXS) | – | 1 |

| UDP-arabinose 4-epimerase (UXE) | 5.1.3.5 | 3 |

| UDP-glucose 4,6-dehydratase (RHM) | 4.2.1.76 | 4 |

| 3,5-epimerase/4-reductase (UER1) | 5.1.3.-1.1.1.- | 1 |

Fig. 3.

Proposed pathways for polysaccharide biosynthesis in P. cyrtonema. Note: Arrows with solid lines represent the identified enzymatic reactions, and arrows with dashed lines represent multiple enzymatic reactions through multiple steps. Activated monosaccharide units, marked in black with yellow background and the enzymes, marked in red

Fig. 4.

Total expression levels of unigenes encoding enzymes involved in polysaccharide biosynthesis. Note: The columns one, two, three and four represent one-year, two-year, three-year and four-year rhizome samples, respectively. Red, blue and grey represent high, medium and low expression levels, respectively

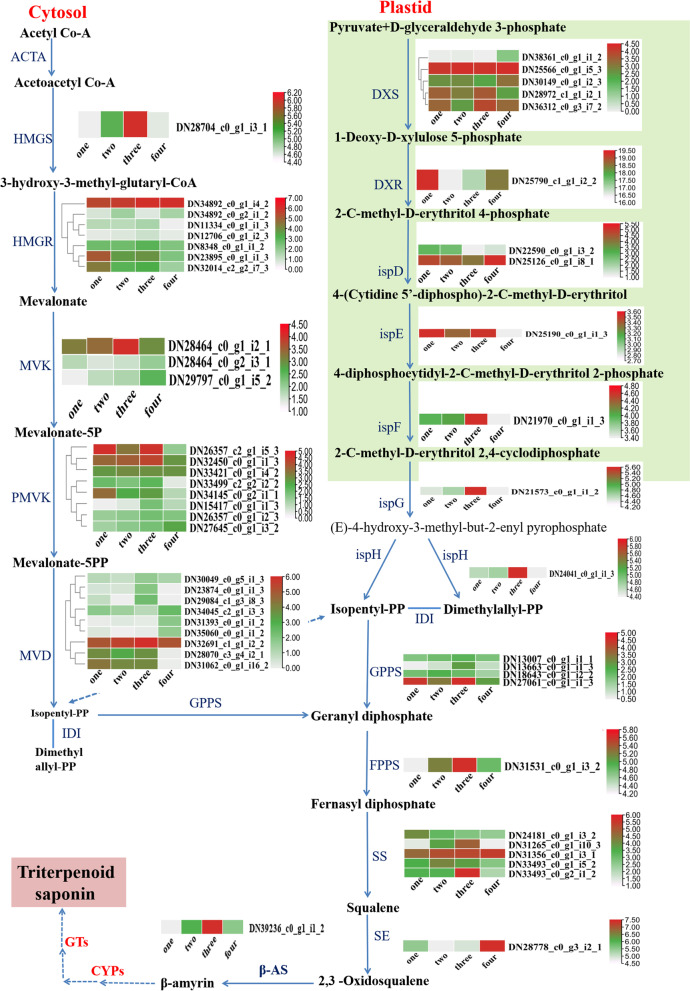

Identification of genes involved in saponins biosynthesis

In order to enhance our understanding of triterpene saponins biosynthesis, we also annotated unigenes involved in terpenoid backbone biosynthesis (Ko00900) and carotenoid biosynthesis (Ko00906) pathways based on the KEGG database. A total of 56 unigenes encoding key enzymes, including hydroxymethylglutaryl CoA synthase (HMGS), mevalonate kinase (MVK), 1-deoxy-D-xylulose-5-phosphate synthase (DXS), 1-deoxy-D-xylulose-5-phosphate reductoisomerase (DXR), geranylgeranyl diphosphate synthase (GGPS), squalene synthase (SS) et al. (Table 3). These data enabled the identification of genes encoding enzymes involved in triterpene saponins biosynthesis using the FPKM approach (Fig. 5).

Table 3.

Number of unigenes encoding key enzymes involved in triterpene saponin biosynthesis in P. cyrtonema

| Enzyme name | EC number | Unigene number |

|---|---|---|

| Acetyl-CoA acetyl transferase (AATC) | 2.3.1.9 | 0 |

| Hydroxymethylglutaryl CoA synthase (HMGS) | 2.3.3.10 | 1 |

| 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase (HMGR) | 1.1.1.34 | 7 |

| Mevalonate kinase (MVK) | 2.7.1.36 | 3 |

| Phosphomevalonate kinase (PMVK) | 2.7.4.2 | 8 |

| Mevalonate diphosphosphate decarboxylase (MVD) | 4.1.1.33 | 9 |

| 1-deoxy-D-xylulose-5-phosphate synthase (DXS) | 2.2.1.7 | 5 |

| 1-deoxy-D-xylulose-5-phosphate reductoisomerase (DXR) | 1.1.1.267 | 1 |

| 2-C-methyl-D-erythritol4-phosphate cytidylyltransferase (ispD) | 2.7.7.60 | 2 |

| 4-diphosphocytidyl-2-C-methyl-D-erythritol kinase (ispE) | 2.7.1.148 | 1 |

| 2-C-methyl-D-erythritol 2,4-cyclodiphosphate synthase (ispF) | 4.6.1.12 | 1 |

| (E)-4-hydroxy-3-methylbut-2-enyl-diphosphate synthas (ispG) | 1.17.7.1 | 1 |

| 4-hydroxy-3-methylbut-2-enyl diphosphate reductase (ispH) | 1.17.7.4 | 1 |

| Isopentenyl-diphosphate Delta-isomerase (IDI) | 5.3.3.2 | 1 |

| Geranyl diphosphate synthase (GPS) | 2.5.1.1 | 3 |

| Geranylgeranyl diphosphate synthase (GGPS) | 2.5.1.29 | 5 |

| Farnesyl diphosphate synthase (FPPS) | 2.5.1.10 | 1 |

| Squalene synthase (SS) | 2.5.1.21 | 5 |

| Squalene epoxidase (SE) | 1.14.14.17 | 1 |

Fig. 5.

Total expression levels of unigenes encoding enzymes involved in triterpene saponin biosynthesis. Note: The columns one, two, three and four represent one-year, two-year, three-year and four-year rhizome samples, respectively. Red, green and grey represent high, medium and low expression levels, respectively

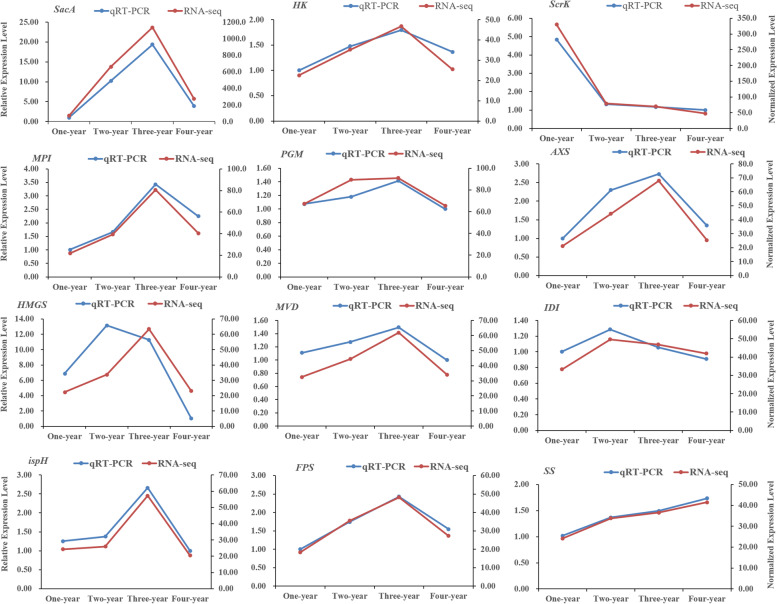

Validation and expression analysis of genes encoding key enzymes

To validated the reliability of transcriptome sequencing data, the expression levels of genes encoding beta-fructofuranosidase (sacA), fructokinase (scrk), mannose-6-phosphate isomerase (MPI), phosphoglucomutase (PGM), UDP-apiose/xylose synthase (AXS), hydroxymethylglutaryl CoA synthase (HMGS), mevalonate diphosphosphate decarboxylase (MVD), isopentenyl-diphosphate delta-isomerase (IDI), farnesyl diphosphate synthase (FPPS) and squalene synthase (SS) et al. were tested by qRT-PCR assays The results revealed the qRT-PCR data for these 16 genes were basically consistent with the RNA-Seq data (Fig. 6, the numerical values of error bar is presented in Additional file 9: Table S3). Generally, the above results revealed that our transcriptome data were reliable for genes temporal expression analysis during the rhizome developmental processes in P. cyrtonema.

Fig. 6.

The expression levels of 12 genes at one-year, two-year, three-year and four-year rhizomes in P. cyrtonema for qRT-PCR and RNA-seq experiment (mean ± SD, n = 3)

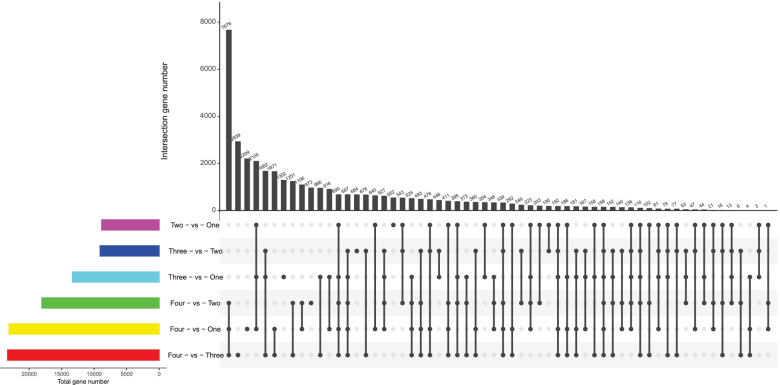

Identification of DEGs

DEGs were recognized in all different developmental rhizomes using FPKM values for unigenes. When one-year rhizomes were set as the control, and 8850, 13,361 and 23,107 different expressed genes (DEGs) (p-value< 0.05 and fold change> 1.5) were identified at two-year, three-year and four-year rhizomes, respectively. When two-year rhizomes were set as the control, a total of 9101 and 18,067 DEG were identified at three-year and four-year rhizomes, respectively. When three-year rhizomes were set as the control, a total of 23,332 DEGs were identified at four-year rhizomes (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Venn diagram of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) among different P. cyrtonema rhizomes samples. Note: the abscissa on the left reflects the number of genes and the ordinate represent different comparison groups, the black dot is used to connect different regions to represent the common gene of different comparison groups and the number of these common genes is displayed by the bar graph on the right

Identification of TFs involved in the biosynthesis of polysaccharides, saponins and other secondary metabolites

A total of 1492 TFs were identified in transcriptome database of P. cyrtonema. Cause of the contents of polysaccharides and saponins all increase from one-year rhizomes to three-year rhizomes, one-year vs three-year contrast was analyzed, 245 TFs were up-regulated and 135 TFs were down-regulated (Table 4). The major TF families were identified in this analysis included AP2/ERF-ERF (107 unigenes), WRKY (106 unigenes), NAC (89 unigenes), bHLH (85 unigenes), C2H2 (84 unigenes), C3H (79 unigenes) and MYB-related (76 unigenes) groups.

Table 4.

Type and number of transcription factors (TFs) of P. cyrtonema

| TF_family | Number of unigenes | Up-regulated unigenes | Down-regulated unigenes |

|---|---|---|---|

| AP2/ERF-AP2 | 10 | 5 | 0 |

| AP2/ERF-ERF | 107 | 26 | 12 |

| AP2/ERF-RAV | 3 | 0 | 2 |

| Alfin-like | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| B3 | 42 | 5 | 4 |

| B3-ARF | 19 | 1 | 0 |

| BBR-BPC | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| BES1 | 8 | 1 | 0 |

| C2C2-CO-like | 6 | 2 | 0 |

| C2C2-Dof | 26 | 9 | 1 |

| C2C2-GATA | 24 | 5 | 3 |

| C2C2-LSD | 5 | 1 | 0 |

| C2C2-YABBY | 6 | 4 | 1 |

| C2H2 | 84 | 13 | 6 |

| C3H | 79 | 8 | 1 |

| CAMTA | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| CPP | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| CSD | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| DBB | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| DBP | 3 | 1 | 0 |

| E2F-DP | 8 | 0 | 0 |

| EIL | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| FAR1 | 64 | 2 | 5 |

| GARP-ARR-B | 7 | 1 | 0 |

| GARP-G2-like | 46 | 6 | 4 |

| GRAS | 33 | 8 | 1 |

| GRF | 11 | 4 | 1 |

| GeBP | 16 | 2 | 1 |

| HB-BELL | 12 | 4 | 0 |

| HB-HD-ZIP | 25 | 6 | 0 |

| HB-KNOX | 8 | 3 | 0 |

| HB-PHD | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| HB-WOX | 6 | 1 | 1 |

| HB-other | 23 | 1 | 1 |

| HRT | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| HSF | 35 | 6 | 8 |

| LIM | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| LOB | 17 | 3 | 0 |

| MADS-M-type | 23 | 0 | 0 |

| MADS-MIKC | 12 | 6 | 1 |

| MYB | 67 | 19 | 4 |

| MYB-related | 76 | 9 | 6 |

| NAC | 89 | 10 | 17 |

| NF-X1 | 3 | 1 | 0 |

| NF-YA | 8 | 0 | 1 |

| NF-YB | 11 | 4 | 1 |

| NF-YC | 9 | 1 | 0 |

| OFP | 12 | 7 | 0 |

| PLATZ | 13 | 2 | 1 |

| RWP-RK | 8 | 0 | 0 |

| S1Fa-like | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| SAP | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| SBP | 22 | 7 | 1 |

| SRS | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| STAT | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| TCP | 24 | 7 | 1 |

| TUB | 21 | 1 | 0 |

| Tify | 25 | 2 | 3 |

| Trihelix | 25 | 1 | 2 |

| ULT | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| VOZ | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| WRKY | 106 | 5 | 31 |

| Whirly | 5 | 1 | 0 |

| bHLH | 85 | 18 | 9 |

| bZIP | 58 | 11 | 4 |

| zf-HD | 9 | 4 | 0 |

| zn-clus | 4 | 1 | 0 |

SSR marker analysis

To develop SSR markers in P. cyrtonema, MISA software was applied to identify the SSRs sites among 62,635 unigenes. A total of 17,351 SSRs were identified (SSR > =1, 13,116 unigenes; SSR > =2, 3159 unigenes; compound SSRs, 1567 unigenes). In 17,357 SSRs founded the mono-nucleotide repeat motifs were the most abundant types (45.51%), followed by di-nucleotide (31.12%), tri-nucleotide (21.79%), hexa-nucleotide (0.67%), tetra-nucleotide (0.66%), and penta-nucleotide tandem repeats (0.25%, Table 5).

Table 5.

Distribution of identified SSRs of P. cyrtonema

| Motif | Repeat numbers | Total | % | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | > 11 | |||

| Mono- | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3838 | 1497 | 2562 | 7897 | 45.51 |

| Di- | 0 | 1769 | 1051 | 656 | 433 | 279 | 179 | 1033 | 5400 | 31.12 |

| Tri- | 2165 | 895 | 389 | 179 | 85 | 46 | 8 | 14 | 3781 | 21.79 |

| Tetra- | 83 | 24 | 6 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 114 | 0.66 |

| Penta- | 31 | 11 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 43 | 0.25 |

| Hexa- | 92 | 13 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 116 | 0.67 |

| Total | 2371 | 2712 | 1452 | 839 | 519 | 4163 | 1685 | 3610 | 17,351 | 100 |

| % | 13.66 | 15.63 | 8.37 | 4.84 | 2.99 | 23.99 | 9.71 | 20.81 | 100 | |

Discussion

P. cyrtonema is a well-known medical and edible plant, and it has a variety of biology activities such as anti-aging, nourishing yin, anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory et al. [3–5]. Although polysaccharides and saponins are the significant effective constituents, however, up to now, genomic data is still unknown and only a copy of transcriptome data without biological duplications for three tissues of P. cyrtonema is available [20], that is obviously inadequate for demonstrating the molecule mechanisms of active constituents’ biosynthesis such as polysaccharide and saponins. In this study, we obtained a more reliable and high-quality assembly result (unigenes with an average length of 1007.11 bp) than previous transcriptome data (mean length 710 bp) in P. cyrtonema, also enriches the types of gene expression data, and facilitate the selection of key candidate genes involved in polysaccharides and saponins biosynthesis, condense the number of candidate genes to be verified.

A large number of unigenes participated in polysaccharide and saponins biosynthesis were identified (Figs. 4 and 5). For polysaccharide biosynthesis pathway, the genes encoding MPI, AXS, TSTA3, UER1, GALE and UGDH enzymes were high expressed in three-year rhizomes compared with other-year rhizomes, and these gene expression pattern is consistent with the accumulation pattern of polysaccharide with the rhizome development from one-year to four-year (Fig. 4, Additional file 1: Fig. S1), while the genes encoding HK and scrk demonstrate opposite pattern of expression against the accumulation of polysaccharide. Similar phenomenon was also observed in previous researches [20–23]. We speculate that MPI, AXS, TSTA3, UER1, GALE and UGDH are underlying key enzyme genes play vital roles in regulating the polysaccharide content of P. cyrtonema rhizomes and HK, scrk are mainly participate in other pathway such as sugar signaling, carbohydrate metabolism et al. [24]. For saponin biosynthesis pathway, the genes encoding HMGS, MVK, ispF, ispG, ispH and FPPS enzymes were high expressed in three-year rhizomes, and these gene expression pattern is consistent with the accumulation pattern of total saponin with the rhizome development (Fig. 5, Additional file 2: Fig. S2). It seems that MEP and MVA pathway all participated in the saponin biosynthesis [15, 17].

Plenty of TFs have been isolated and verified participating in a diversity of plant biological processes including biosynthesis of polysaccharides, saponins and other secondary metabolism processes. In our results, A total of 380 candidate TFs were allocated to the AP2/ERF-ERF, WRKY, NAC, bHLH, C2H2, C3H and MYB-related families; these TFs probably play roles in regulating polysaccharide and saponins biosynthesis. Previous Researches revealed GubHLH3 positively regulates soyasaponin biosynthetic genes in Glycyrrhiza uralensis [25] and the bHLH transcription factors TSAR1 and TSAR2 regulate triterpene saponin biosynthesis in Medicago truncatula [26], A total of 85 candidate unigenes encoding bHLH TFs were identified, of which 18 and 9 were up-regulated in the three-year rhizome compared with other-year rhizome, respectively (Table 4). Over-expression of AtMYB46 gene can enhance mannan content of hemicellulose polysaccharides [27]. A total of 67 candidate unigenes encoding MYB TFs were recognized, of which 19 and 4 were up-regulated in the three-year rhizome, respectively. These up-regulated unigenes are vital for subsequent studies aimed at exploring the regulation of polysaccharide and saponins biosynthesis in P. cyrtonema. The characterization of these unigenes will be beneficial for realizing the molecular mechanisms underlying polysaccharide and saponin biosynthesis.

Materials and methods

Ethics statement

Experimental materials were harvested across China, but the field studies did not involve endangered or protected species. This study was conducted at the in Guizhou Key Laboratory of Propagation and Cultivation on Medicinal Plants in Southwest China, Guiyang, China.

Plant material

P. cyrtonema rhizomes were collected from the teaching and experimental farm of Guizhou University (116°40′E, 39°96′N) and identified as Polygonatum cyrtonema Hua (Asparagaceae) by Professor Hualei Wang (Guizhou University of Agronomy College). All plant samples were cleaned, removed fibrous root, dried on filter paper and then instantly frozen in liquid nitrogen.

Extraction and determination of total polysaccharide and saponins

Total polysaccharides were extracted and detected from freeze-dried rhizomes samples of P. cyrtonema as described in Chinese Pharmacopoeia [2]. Total saponins were extracted and detected by colorimetry. Three repetitions have been done and a statistical analysis been performed by SPSS 22.0 software.

Total RNA extraction, cDNA library construction and sequencing

The total RNA of one-year, two-year, three-year, four-year rhizomes with three biological replicates isolated using an E.Z.N.A. Plant RNA Kit (Omega Biotech Co. Ltd., USA) (Additional file 10: Table S4). RNA quality including integrity and concentration were evaluated using Huang et al.’s method [28]. The RNA-Seq libraries were generated using TruSeq Stranded mRNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina (San Diego, CA, USA). Then qualified libraries were sequenced using an Illumina HiSeqTM 4000 platform (Ouyi biology, Shanghai, China).

De novo assembly and unigene function annotation

Low quality reads were removed before data analysis and high-quality clean reads were used to assemble using Trinity software [29]. For the CDS sequences which had no hits in Blast, ESTScan was used for predicting [30]. According to sequence similarities, functional annotations for unigenes were executed and mapped to seven databases including NCBI non-redundant, Swiss-Prot, KEGG (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes) protein databases, KOG database, eggNOG database, GO and Pfam database. In addition, GO functional annotations were also attained with Nr annotation using the Blast2GO (version 2.5.0) [31]. KEGG Orthology annotations were further conducted using BlastX algorithm against KEGG database.

Differential expression analysis

The quantitative expression level of unigenes for four rhizomes with different growth years were subjected using Expression Analyzer and DisplayER software (EXPANDER) [32]. The abundance of corresponding unigene transcripts were determined by the FPKM method. We compared unigenes that display differences in expression level between two rhizomes (i.e., one-year rhizome vs. two-year rhizome) using DESeq Software [33]. The FDR ≤ 0.001 and the fold change (FC) ≥ 2 were identified as DEGs.

Analysis of transcription factors (TFs)

For transcriptome data, in P. cyrtonema, the open reading frames (ORF) were determined by the getorf software [34]. Then we aligned these ORFs to all TF protein domains using the plant transcription factor database (PlnTFDB) via BLASTX (e-value≤1e− 5) [35].

Real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis

Total RNA was isolated from P. cyrtonema rhizome (one-year, two-year, three-year, four-year) using the E.Z.N.A. Total RNA Kit I (Omega, USA) and reverse-transcribed to cDNA with TaKaRa reverse transcription reagents (TaKaRa Bio, Dalian, China). The elongation factor 1-ɑ (EF1ɑ, TRINITY_DN27092_c0_g5_i1_1) genes were selected as endogenous references for normalization according to its expression level and stability in transcriptome data. Specific primers were designed by primer 3.0 (Additional file 11: Table S5). Real-time PCR was performed by QuantiNova Sybr Green PCR kit (Qiagen). The results of the target gene relative to the reference gene were calculated by the 2-ΔΔCt method [36]. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) of three reactions performed in different 96-well plates. The data were analyzed using CFX Manager™ v3.0.

Conclusion

A comprehensive transcriptome analysis of one-year, two-year, three-year and four-year rhizome with three duplications in P. cyrtonema were executed and abundant genes and TFs related to polysaccharide and saponin biosynthesis and regulation were identified, respectively. In addition, adequate SSRs marker were founded in transcriptome data that provides a significant convenience for the identification of P. cyrtonema plant. We used qRT-PCR technology to validate the results of transcriptome sequence and our results play a vital role in illuminating the polysaccharide and saponin biosynthesis pathways and facilitate future researches involved in accumulation of secondary metabolism in P. cyrtonema.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Figure S1. Total polysaccharide content in tuber of Polygonatum cyrtonema Hua of different growing years.

Additional file 2: Figure S2. Total saponin content in tuber of Polygonatum cyrtonema Hua of different growing years.

Additional file 3: Table S1. The results of sequencing data quality.

Additional file 4: Figure S3. Sequence length distribution for P. cyrtonema transcriptome assembly.

Additional file 5: Figure S4. Species distribution annotated in the NR database for P. cyrtonema.

Additional file 6: Figure S5. GO function annotation of P. cyrtonema transcriptome.

Additional file 7: Figure S6. KEGG functional classifications of the annotated unigenes in P. cyrtonema.

Additional file 8: Table S2. KEGG annotation of all unigenes.

Additional file 9: Table S3. The numerical values of error bar.

Additional file 10: Table S4. RNA information of different samples.

Additional file 11: Table S5. Gene descriptions and primers used for qRT-PCR.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thanks the Guizhou Key Laboratory of Propagation and Cultivation on Medicinal Plants for kindly supplying the experimental material.

Authors’ contributions

Hualei Wang and Dandan Li conceived and designed the experiments. Qing Wang, Keqin Pan, Songshu Chen, HongChang Liu performed the experiments. Dandan Li analyzed the data. Songshu Chen, Jinling Li, and Chunli Luo contributed reagents/materials/analytical tools. Dandan Li drafted the manuscript, and Hualei Wang revised it. All authors discussed and commented on the manuscript. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (#31760421); the Talent Introduction Project of Guizhou University (2019#17) and Guizhou Provincial Science and Technology Department of Support Project ([2020]4Y102).

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) under projects PRJNA755493.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The plant materials are provided by the Guizhou Key Laboratory of Propagation and Cultivation on Medicinal Plants and we have the right to use them. Sampling of plant materials were performed in compliance with institutional, national, and international guidelines. The materials were publicly available for non-commercial purposes. No specific permits were required.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Dandan Li, Email: 1183300979@qq.com.

Qing Wang, Email: 1241808624@qq.com.

Songshu Chen, Email: 429020703@qq.com.

Hongchang Liu, Email: 604957649@qq.com.

Keqin Pan, Email: 1401491722@qq.com.

Jinling Li, Email: 151904742@qq.com.

Chunli Luo, Email: 306469096@qq.com.

Hualei Wang, Email: 13027865861@163.com.

References

- 1.Luo M, Zhang WW, Deng CF, Tan QS, Luo C, Luo S. Advances in studies of medicinal crop Polygonatum cyrtonema Hua. Lishizhen Med Mater Med Res. 2016;27(6):1467–1469. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Committee for the Pharmacopoeia of People Republic China. Pharmacopoeia of P.R. China, part I: Chinese Pharmacopoeia, edition one. 2020. p. 319–20. https://db.ouryao.com/yd2020/.

- 3.Chen H, Feng SS, Sun YJ, Hao ZY, Zheng XK. Advances in studies on chemical constituents of three medicinal plants from Polygonatum mill. and their pharmacological activities. Chin Tradit Herb Drugs. 2015;46(15):2329–2338. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang JX, Wu S, Huang XL, Hu XQ, Zhang Y. Hypolipidemic activity and antiatherosclerotic effect of polysaccharide of Polygonatum sibiricum in rabbit model and related cellular mechanisms. Evid Based Complement Altern Med. 2015;39:1065. doi: 10.1155/2015/391065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wu LH, Lv GY, Li B, Zhang YL, Su J, Chen SH. Study on effect of Polygonatum sibiricum on Yin deficiency model rats induced by long-term overload swimming. China J Chin Mater Med. 2014;39(10):1886–1891. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.He LJ, Gan YP, Lv WD, Rao JF, Yang JM, Yu JS. Monosaccharide composition analysis on polysaccharides in P. cyrtonema by high performance anion-exchange chromatography with pulsed amperometric detection. Chin Tradit Herb Drugs. 2017;47(8):1671–1676. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xie Y, Zhou H, Liu C, Jing Z, Ning L, Zhao Z, Sun G, Zhong Y. A molasses habitat-derived fungus Aspergillus tubingensis XG21 with high β-fructofuranosidase activity and its potential use for fructooligosaccharides production. AMB Express. 2017;7(1):128. doi: 10.1186/s13568-017-0428-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang Y, Zhen L, Tan X, Li L, Wang X. The involvement of hexokinase in the coordinated regulation of glucose and gibberellin on cell wall invertase and sucrose synthesis in grape berry. Mol Biol Rep. 2014;41(12):7899–7910. doi: 10.1007/s11033-014-3683-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Uematsu K, Suzuki N, Iwamae T, Inui M, Yukawa H. Expression of arabidopsis plastidial phosphoglucomutase in tobacco stimulates photosynthetic carbon flow into starch synthesis. J Plant Physiol. 2012;169(15):1454–1462. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2012.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Perezcenci M, Salerno GL. Functional characterization of Synechococcus amylosucrase and fructokinase encoding genes discovers two novel actors on the stage of cyanobacterial sucrose metabolism. Plant Sci. 2014;224(13):95–102. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2014.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bachmann P, Zetsche K. A close temporal and spatial correlation between cell growth, cell wall synthesis and the activity of enzymes of mannan synthesis in Acetabularia mediterranea. Planta. 1979;145(4):331–337. doi: 10.1007/BF00388357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Park JI, Ishimizu T, Suwabe K, Sudo K, Masuko H, Hakozaki H, Nou IS, Suzuki G, Watanabe M. UDP-glucose pyrophosphorylase is rate limiting in vegetative and reproductive phases in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol. 2010;51(6):981–996. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcq057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yin Y, Huang J, Gu X, Barpeled M, Xu Y. Evolution of plant nucleotide-sugar interconversion enzymes. PLoS One. 2011;6(11):e27995. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pauly M, Gille S, Liu L, Mansoori N, Souza A, Schultink A, Xiong G. Hemicellulose biosynthesis. Planta. 2013;238(4):627–642. doi: 10.1007/s00425-013-1921-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ma CH, Gao ZJ, Zhang JJ, Zhang W, Shao JH, Hai MR, Chen JW, Yang SC, Zhang GH. Candidate genes involved in the biosynthesis of triterpenoid saponins in Platycodon grandiflorum identified by transcriptome analysis. Front Plant Sci. 2016;7:673. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.00673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Singh P, Singh G, Bhandawat A, Singh G, Parmar R, Seth R, Sharma RK. Spatial transcriptome analysis provides insights of key genes involved in steroidal saponin biosynthesis in medicinally important herb Trillium govanianum. Sci Rep. 2017;7:45295. doi: 10.1038/srep45295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sun H, Fang L, Xu Z, Sun M, Cong H, Fei Q, Zhong X, Turgry U. De novo leaf and root transcriptome analysis to identify putative genes involved in triterpenoid saponins biosynthesis in Hedera helix L. PLoS One. 2017;12(8):e0182243. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0182243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Matsuda F, Hirai MY, Sasaki E, Akiyama K, Yonekura-Sakakibara K, Provart NJ, Sakurai T, Shimada Y, Saito K. AtMetExpress development: a phytochemical atlas of Arabidopsis development. Plant Physiol. 2010;152(2):566–578. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.148031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang H, He L, Cai L. Computational systems biology. Methods in molecular biology. New York: Humana Press; 2018. Transcriptome sequencing: RNA-Seq; p. 1754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang C, Peng DY, Zhu JH, Zhao DR, Shi YY, Zhang SX, Ma KL, Wu JW, Huang LQ. Transcriptome analysis of Polygonatum cyrtonema Hua: identification of genes involved in polysaccharide biosynthesis. Plant Methods. 2019;15(1):65. doi: 10.1186/s13007-019-0441-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abhijit K, Xiaoxia X, Moore BD. Arabidopsis Hexokinase-Like1 and Hexokinase1 form a critical node in mediating plant glucose and ethylene responses. Plant Physiol. 2012;158(4):1965–1975. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.195636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang SQ, Wang B, Hua WP, Niu JF, Dang KK, Qiang Y, Wang ZY. De novo assembly and analysis of Polygonatum sibiricum transcriptome and identification of genes involved in polysaccharide biosynthesis. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18(9):1950. doi: 10.3390/ijms18091950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stein O, Granot D. Plant Fructokinases: evolutionary, developmental, and metabolic aspects in sink tissues. Front Plant Sci. 2018;9:339. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2018.00339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li NN, Qian WJ, Wang L, Cao HL, Hao XY, Yang YJ, Wang XC. Isolation and expression features of hexose kinase genes under various abiotic stresses in the tea plant (Camellia sinensis) J Plant Physiol. 2017;209:95–104. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2016.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tamura K, Yoshida K, Hiraoka Y, Sakaguchi D, Chikugo A, Mochida K, Kojoma M, Mitsuda N, Saito K, Muranaka T, Seki H. The basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor GubHLH3 positively regulates soyasaponin biosynthetic genes in Glycyrrhiza uralensis. Plant Cell Physiol. 2018;59(4):778–791. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcy046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mertens J, Pollier J, Bossche RV, Lopez-Vidriero I, Franco-Zorrilla JM, Goossens A. The bHLH transcription factors TSAR1 and TSAR2 regulate triterpene saponin biosynthesis in Medicago truncatula. Plant Physiol. 2015;170(1):194. doi: 10.1104/pp.15.01645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim WC, Reca IB, Kim YS, Park S, Thomashow MF, Keegstra K, Han KH. Transcription factors that directly regulate the expression of CSLA9 encoding mannan synthase in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Mol Biol. 2014;84(4–5):577. doi: 10.1007/s11103-013-0154-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huang JZ, Hao XH, Jin Y, Guo XH, Shao Q, Kumar KS, Ahlawat YK, Harry DE, Joshi CP, Zheng YZ. Temporal transcriptome profiling of developing seeds reveals a concerted gene regulation in relation to oil accumulation in Pongamia (Millettia pinnata) BMC Plant Biol. 2018;18(1):140. doi: 10.1186/s12870-018-1356-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guo B, Chen ZY, Lee RD, Scully BT. Drought stress and preharvest aflatoxin contamination in agricultural commodity: genetics, genomics and proteomics. J Integr Plant Biol. 2008;50:1281–1291. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7909.2008.00739.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Iseli C, Jongeneel CV, Bucher P. Proc Int Conf Intell Syst Mol Biol. 1999. ESTScan: a program for detecting, evaluating, and reconstructing potential coding regions in EST sequences; pp. 138–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Conesa A, Gotz S, Garcia-Gomez JM, Terol J, Talon M, Robles M. Blast2GO: a universal tool for annotation, visualization and analysis in functional genomics research. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:3674–3676. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shamir R, Maron-Katz A, Tanay A, Linhart C, Steinfeld I, Sharan R, Shilohy Y, Ran E. EXPANDER-an integrative program suite for microarray data analysis. BMC Bioinformatics. 2005;6:232–244. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-6-232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Anders S, Huber W. Differential expression analysis for sequence count data. Genome Biol. 2010;11:1–12. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-10-r106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rice P, Longden I, Bleasby A. EMBOSS: the European molecular biology open software suite. Trends Genet. 2000;16(6):276–277. doi: 10.1016/S0168-9525(00)02024-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mistry J, Finn RD, Eddy SR, Bateman A, Punta M. Challenges in homology search: HMMER3 and convergent evolution of coiled-coil regions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41(12):e121. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2-ΔΔCt method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Figure S1. Total polysaccharide content in tuber of Polygonatum cyrtonema Hua of different growing years.

Additional file 2: Figure S2. Total saponin content in tuber of Polygonatum cyrtonema Hua of different growing years.

Additional file 3: Table S1. The results of sequencing data quality.

Additional file 4: Figure S3. Sequence length distribution for P. cyrtonema transcriptome assembly.

Additional file 5: Figure S4. Species distribution annotated in the NR database for P. cyrtonema.

Additional file 6: Figure S5. GO function annotation of P. cyrtonema transcriptome.

Additional file 7: Figure S6. KEGG functional classifications of the annotated unigenes in P. cyrtonema.

Additional file 8: Table S2. KEGG annotation of all unigenes.

Additional file 9: Table S3. The numerical values of error bar.

Additional file 10: Table S4. RNA information of different samples.

Additional file 11: Table S5. Gene descriptions and primers used for qRT-PCR.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) under projects PRJNA755493.