Significance

This study uses large-scale news media and social media data to show that nationwide Black Lives Matter (BLM) protests occur concurrently with sharp increases in public attention to components of the BLM agenda. We also show that attention to BLM and related concepts is not limited to these brief periods of protest but is sustained after protest has ceased. This suggests that protest events incited a change in public awareness of BLM’s vision of social change and the dissemination of antiracist ideas into popular discourse.

Keywords: Black Lives Matter, cultural change, social movements

Abstract

We show that Black Lives Matter (BLM) protests shift public discourse toward the movement’s agenda, as captured by social media and news reports. We find that BLM protests dramatically amplify the use of terms associated with the BLM agenda throughout the movement’s history. Longitudinal data show that terms denoting the movement’s theoretically distinctive ideas, such as “systemic racism,” receive more attention during waves of protest. We show that these shocks have notable impact beyond intense, or “viral,” periods of nationwide protest. Together, these findings indicate that BLM has successfully leveraged protest events to engender lasting changes in the ways that Americans discuss racial inequality.

Before social change, there is discussion of social change. For this reason, social scientists who study protest outcomes focus on agenda setting. Once protests and direct action draw attention to a movement’s goals, allies in the media, government, and the private sector may introduce policies that institutionalize the movement’s objectives. It is for this reason that social movement scholars in sociology, political science, and mass communication research have investigated the link between contentious political behavior and public discourse.

A rich literature documents the different ways that protests generate attention for political issues. McAdam and Su (1) show that increased anti–Vietnam War protest resulted in more congressional hearings, and Guillion’s (2, 3) studies of the Civil Rights Movement show protest for Black rights was associated with more discussion of voting and housing rights by the White House, which was followed by a wide range of administrative policies and legislative efforts (4). The political scientist Hans Noel (4) has argued that antialcohol activists in the late 19th century were able to project their message into newspapers, which set the stage for the passage of the 18th Amendment in 1919.

Even though scholars have long understood that protest can lead to changes in public discourse and political agendas, the rise of Black Lives Matter (BLM), and the appearance of antiracist culture in the 2010s raises new questions about the link between activism and discourse change (2, 5–8). How does protest translate into behavioral changes in online platforms such as Google, Twitter, and Wikipedia?

This study addresses a series of questions about how street protest is followed by large shifts in public attention as captured by digital platforms. By doing so, we contribute to an ongoing scholarly analysis of the BLM movement. Early studies examined the emergence of the movement and summarized its history (9, 10). In subsequent years, research on BLM has documented patterns of protest, identified the social contexts that trigger protests, such as police shootings, and examined whether protests are associated with Black political institutions such as National Association for the Advancement of Colored People offices or Black mayors (11). Recently, BLM research has measured the movement’s policy and electoral impacts. Prior studies have shown an association between BLM protest and Democratic vote shares in the 2020 election (12), as well as the reduction of police shooting fatalities (13).

We expand this assessment with an analysis of how BLM protests lead to increased use of antiracist vocabulary on multiple digital platforms. Prior large-scale quantitative research on the movement’s cultural impacts is scant. A handful of earlier studies examined the use of hashtags related to BLM on Twitter, while others claimed that BLM reduced bias in society, with data from volunteers who took an implicit bias test online (14–17).

By establishing a link between BLM’s political rallies and increased use of antiracist terminology, we show how political movements change society beyond the political sphere. Scholars have shown that protest has nonpolitical impacts such as changing school curricula (18), encouraging “ethical consumerism” (19, 20), and suppressing the stock prices of firms that employ unethical labor practices (21). Similarly, BLM aims to change American society by encouraging people to use terms such as “systemic racism,” “White supremacy,” and “mass incarceration,” which are drawn from antiracist theory. This theory argues that social institutions, such as the criminal justice system, reproduce inequality by penalizing social behaviors associated with minority groups and creating differences that encourage society at large to see racial disparities as natural and inevitable (22, 23). Antiracism discourse is distinctive in that it does not view racism as an individual pathology or dysfunction.

This analysis contributes to a larger discussion within the social sciences about the relationship between political action and cultural change. This literature depicts a complex and multidirectional process. Political actions, such as protest, draw attention to issues and shift agendas, while changes in the way that people frame political issues also enable political action. Prior research, for example, has examined how particular forms of media, such as film, are associated with increased protest. Vasi et al.’s (24) study showed how the screening of environmental films is associated with short-term increases in local antifracking protest. Other research shows how social movement frames can be adopted by political groups in successful campaigns for policy change. Using state-level data on political campaigns, McCammon et al.’s (25) study of women’s jury activists showed that the way that legal activists framed women’s participation in juries is associated with new legislation. Similarly, BLM relies on frames that already exist. Activists describe their movement as a continuation of earlier Black freedom struggles (26). The present analysis focuses on what happens after movements emerge and they attempt to bring their ideas to the public through widely accessible digital platforms. We add to this longstanding scholarly discussion with a large-scale computational study of the association between street-level protest and discursive change.

Research Questions and Hypotheses

The primary purpose of this paper is to show that political actions, such as BLM protests, can trigger sustained attention to antiracist ideas. To document this effect, we tracked the use of antiracist terms in four different publicly available datasets. We then correlated vocabulary use data with public data on recent BLM protests that were organized in response to police violence. We use these data to answer the following research questions: 1) Is there an increase in the use of antiracist vocabulary on digital platforms in the period after the start of the BLM movement that is substantially higher than before? 2) How is BLM protest associated with increased attention paid to the movement as measured by the volume of Google searches for the phrase “Black Lives Matter”? 3) When protest increases attention to the phrase “Black Lives Matter,” does it also increase attention to other terms associated with antiracist politics? 4) How does attention to the phrase “Black Lives Matter” and related terms change over multiple waves of protest? 5) Which antiracist terms experienced sustained attention in the period after the George Floyd protests? 6) Did increased and sustained attention given to BLM “spill over” to other related terms? 7) How is BLM protest associated with the use of terms representing the movement’s opposition?

Data Sources Used in This Study

This study aims to empirically measure and assess how BLM protest may be associated with increased attention given to antiracist terms on digital platforms. However, there is no single way to measure how issues are discussed at the national level. Therefore, we have opted for a research strategy where we use multiple publicly available data sources, each of which has strengths and weaknesses. Throughout this study, we largely rely on Google search volume as a measure of public attention. Google search represents popular, rather than elite, attention that is a response to encountering ideas that emerge from a wide range of contexts such as news, face-to-face conversation, or social media. Furthermore, people often use Google when they want to learn about an issue for the first time. We also use Twitter mentions, Wikipedia page visits, and national news media mentions as indicators for attention to BLM. Twitter is a social media platform that is accessible to researchers and that has become a focal point for online political discussions. As a widely used reference, people use Wikipedia to understand current events and issues of ongoing concern, which allows us to assess typical, or baseline, levels of attention given to certain issues. News items, as measured with data from the Media Cloud Application Programming Interface (API) (27), reflect both daily “news cycles” and articles prepared over a longer period. News media data measure elite discourse, as the ideas appearing in news sources reflect what editors and journalists find newsworthy. One analysis briefly uses data from Google Books to assess long-term trends in the use of antiracist terms by book authors.

Terms Representing Antiracist Discourse

To answer questions about the heterogeneous effects of protest, we analyze Google search and Wikipedia page visit data for a wide range of antiracist terms. Using statements made by activists, sociological theory, and our direct observation of BLM events, we created a list of terms (given by SI Appendix, Table S1) that capture the main components of antiracist discourse, such as its mottos, key figures, policy issues, and comparison with prior movements. While we recognize that no list of terms can completely capture every element of a new vocabulary, these terms capture the major themes associated with BLM, and antiracism more generally.

Contemporary social movement theory suggests that the selection of terms should reflect how a movement frames issues, because framing is one of the core tasks performed by activists. Social movement researchers have argued that framing consists of three elements: 1) diagnosing social problems, 2) suggestions of which movement tactics are appropriate, and 3) a prognosis describing the possible outcomes of collective action and which policies are to be effected (28).

BLM’s diagnosis of a major problem in American society was formulated in response to the killing of African Americans at the hands of police. The initial diagnosis of this problem that BLM proffered was that victims of police homicide, such as Michael Brown, Tamir Rice, and Sandra Bland, symbolized a larger pattern of systemic racism. For this reason, BLM activists often evoke their names, and we used them in our analysis. The tactics were denoted by the popular slogans, including the name of the movement. The initial remedy that the movement seeks is directly related to policy changes to address the injustice of policing and carceral systems, such as “defund the police.”

Early interviews with BLM organizers showed the tactic of reframing the movement as the “new wave” of the Civil Rights Movement and the intention to broaden the movement’s scope by referencing systemic racism and White supremacy (26). Therefore, we also paid attention to historical contexts and figures, and the contemporary discussion of identity politics. The comparison between terms used by BLM and keywords associated with earlier civil rights discourse illuminates how today’s activism has expanded and redefined popular discourse on race.

Results

The BLM Movement Coincides with Increased Attention Given to Black Emancipatory Rhetoric.

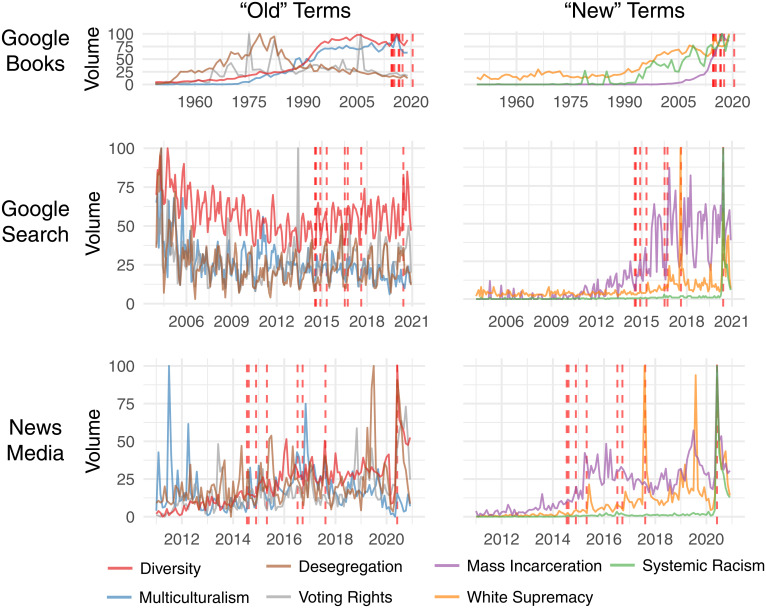

To set the stage for answering questions about BLM protest, we show a dramatic increase in use of terms associated with BLM and antiracist theory in the 2010s. Fig. 1 describes the shift in use of terms associated with BLM, from multiple starting points until 2020. Fig. 1 compares the rise of antiracist terminology with other forms of discourse about racial inequality, such as the earlier Civil Rights Movement. To assess the robustness of the trends, we track these terms in three databases: Google’s digital book archive, Google searches, and news media.

Fig. 1.

Trends in the use of selected antiracist terms. Normalized monthly volume for pre-BLM antiracist terms (Left) and post-BLM antiracist terms (Right). (Top) Google N-grams instances of each term (annual). (Middle) Google searches for each term. (Bottom) National news articles mentioning each term. Red dashed lines correspond to major BLM protest events (29).

To facilitate comparison, Fig. 1 starts with data concerning the use of selected terms in the Google Books database. This comparison is helpful for two reasons. First, book publishing is less susceptible to short-term fluctuations that affect social media and is therefore an indicator of long-term trends. Second, Google Books data underscore the point that people were already changing the way they discussed race before the rise of BLM. The data indicate that the policy issues motivating BLM, such as mass incarceration, began to attract much higher levels of attention as early as 2005. Thus, protest is a process that abruptly elevates certain terms in an environment that is becoming relatively favorable to the movement.

Terms associated with previous forms of racial discourse show either stability, such as “multiculturalism” within national news media, or modest decreases or increases in usage, such as “desegregation” as used in multiple platforms. In contrast, antiracist vocabulary terms show a consistent superlinear trend, where post-2013 usages dramatically increase. Antiracist terms demonstrate a relatively low level of use and then a large upturn in the BLM era. These data suggest an affirmative answer to question 1. BLM protest is followed by a distinct increase in usage of antiracist terms.

BLM Protest Tracks with Google Searches for “Black Lives Matter”.

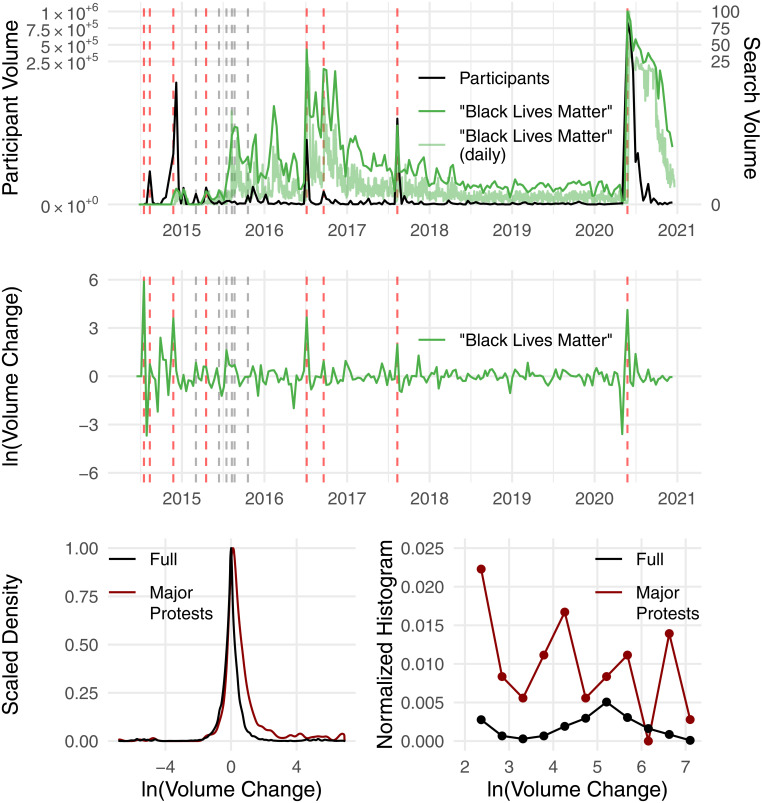

Here we answer question 2 directly by examining the link between protest and antiracist terms. Fig. 2 shows the association between BLM protests and Google searches for the term “Black Lives Matter.” Fig. 2, Top overlays three time series: a count of the estimated number of participants in BLM protests in the United States summed into 8- to 12-d bins, the volume of Google searches for “Black Lives Matter” with the same binning, and a series representing sums across 8- to 12-d bins of Google Search terms. The search volume data are scaled 0 to 100, as Google does not provide absolute search volume data. Data are binned in order to smooth the noise and capture “protest periods” over which protest builds from events in one or several cities to a contagious event across the country. The choice of bin size is further explained in the next subsection of Results.

Fig. 2.

Protests and Google searches are bursty and correlated. (Top) Number of participants at BLM-related protests and volume of Google searches for “Black Lives Matter” (scaled 0 to 100, as Google Trends does not provide absolute search volumes.) (Middle) The change in volume of Google searches, V. Unless otherwise stated, time has been binned such that each point t spans a period of 8 to 12 d designed to fully encapsulate, rather than straddle, protest periods, which occur irregularly. (Bottom Left) Scaled distribution of relative volume of Google searches. Relative volume for all 41 BLM-related search terms during all periods is shown in black, whereas the dark red line shows only protest periods. (Bottom Right) The right tail of a histogram of the data in Bottom Left. In Top and Middle, red and gray dashed lines correspond to major and minor protest events, respectively (minor protest events for only 2015 are pictured). In Top, the upper 3/4 of the vertical axis has been contracted to make visible the variation in the lower fourth.

Fig. 2, Middle shows that abrupt increases, or “spikes,” in searches for “Black Lives Matter” often cooccur with protest events, which are denoted with dashed vertical lines. Fig. 2, Middle takes the data presented in Fig. 2, Top and simplifies it into a single time series denoted the post-over-prior-period ratio in search volume, V. Fig. 2, Middle shows that protests are often followed by attention that is often an order of magnitude or more larger than search volume in the preceding period.

Question 3 asks whether the link between protest and lexical change is limited to “Black Lives Matter” or whether protest also boosts other components of the antiracist lexicon. Fig. 2, Bottom expands the analysis and answers this question. We look at the impact of BLM protest on the use of 41 related antiracist terms. SI Appendix, Table S1 lists these terms, which include names of police shooting victims, slogans, and policy issues. Fig. 2, Bottom shows that the distribution of relative change for all 41 Google search terms combined has a higher mean and a larger right-hand tail during time periods with protest. Fig. 2, Bottom Right, which focuses on the right-hand side of the distribution, shows that days with very “spiky” shifts in attention are much more likely to occur on days with major protests, such as protests associated with the murders of George Floyd and Philando Castile. This suggests that the answer to question 3 is yes—protest is linked with attention increases to many terms associated with the antiracism movement.

Google Search Terms Related to BLM Coactivate.

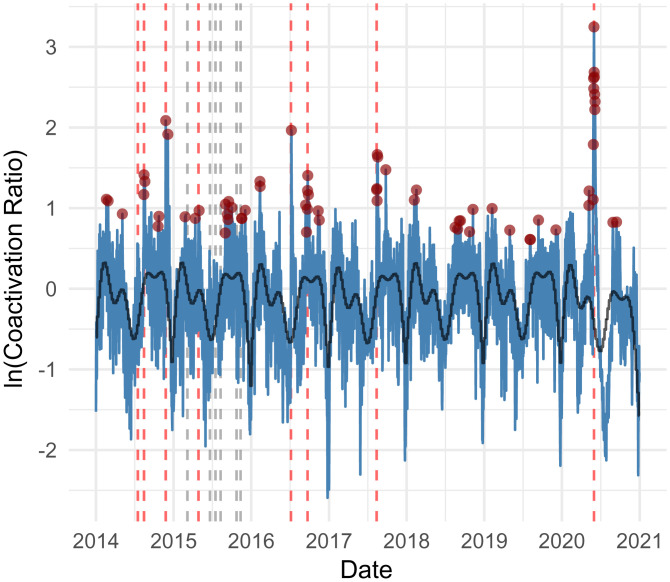

Fig. 3 provides further evidence that BLM protest is generating attention for not only the term “Black Lives Matter” but a wider spectrum of antiracist discourse. To demonstrate the concurrent movement of terms, we plotted the coactivation of these words, which we define as the degree to which a bundle of terms experiences a simultaneous and abrupt shift in attention represented in Google searches. Coactivation captures the idea that multiple measures simultaneously, and abruptly, increase. In contrast, it may be possible that the increase in vocabulary use in Fig. 2 reflects only a handful of terms.

Fig. 3.

Coactivation of Google search terms. Blue lines show the log-ratio of daily coactivation to mean coactivation (60-d window) for all 41 terms. Black line shows GAM prediction from calendar week and absolute time. Red points show significant spikes in coactivation (P < 0.001). Major and minor protest events are indicated by red and gray dashed lines, respectively.

Following Liu and Duyn (30), we define coactivation (C) of a group of terms (G) to be the square root of the sum of the pairwise products of daily search term volumes (): . Coactivation defined in this way is a measure of synchrony designed for “spiky” time series, such as electrical impulse data as found in electroencephalography research.

We compute the coactivation of the 41 terms listed in SI Appendix, Table S1. To answer question 3 and establish that these terms are unusually synchronized on days with BLM protest, one needs to show that coactivation is higher than would be anticipated given the normal fluctuations observed in online search behavior. To estimate whether coactivation on a particular day is unexpected, we fit a normal distribution for a moving 60-d window and compare the daily values to that distribution using a ratio of observed to expected, significance-tested by a z-score. For legibility, Fig. 3 shows the log-ratio of the coactivation of terms within a 60-d window of time.

Since weekdays tend to have greater activity than weekends, we mask the 60-d window such that weekdays are compared to only weekdays, and weekends to only weekends. Thus, the number of observations in the 60-d window is much smaller for weekends, but the observations still span the same period. Fig. 3 shows the ratio of daily coactivation to mean coactivation of the prior 60 d for all pairs of terms from 2014 to 2020. As search engines are often used in educational contexts, there will be natural fluctuations associated with school calendars such as weekends and summer/winter breaks.

To account for these temporal variations, we also present the results of a generalized additive model (GAM) that estimates the effect of time on the coactivation of the selected antiracist terms. The model has two components. The first component comprises nonparametric functions of time, which accounts for daily variations in attention due to academic calendars and other factors. The other component includes multiple linear effects for periods of time with high protest levels, such as June 2020.

The black line in Fig. 3 visualizes predicted coactivation and shows that the abrupt increases in attention can’t be attributed solely to the regular variation in daily use of search engines. The full results of this model are given in SI Appendix, Table S3.

The four largest spikes in collective attention given to antiracism reflect major protest events. The first spike occurs in late 2014, following the hearings for the killers of Michael Brown and Eric Garner, which did not result in indictments, and the killing of Tamir Rice. The second spike occurs in July 2016, which are protests following the killings of Alton Sterling and Philando Castile. The third spike appears in August 2017, corresponding to counterprotests following the Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville. The largest spike is in 2020, which is related to the murder of George Floyd.

The model also allows us to understand the nuanced temporal structure of attention given to the antiracist lexicon. The data show that coactivation increases with the start of the academic term in August, declines sharply during school breaks and holidays, such as winter recess, peaks once again during February, which is Black History Month, and declines sharply during the summer recess. This suggests that some of the variation in attention given to antiracism reflects both routine and modest seasonal variation due to school assignments and the drastic increases seen during demonstrations. This pattern is consistent with prior research on the use of the Google search engine and Wikipedia which finds that school assignments are one of the most common uses for these digital reference tools (31). Future research can attempt to quantify how the typical day-to-day attention given to these terms is related to scholastic activities.

Spikes in Attention to Terms Related to the BLM Agenda Get Larger and More Diverse over Time.

We have established that terms associated with BLM spike during protests. Movements, however, are dynamic, and the impact of protests may vary over time. To answer question 4 about the time-varying effects of protest, we subdivide the search terms into thematic categories. By examining these categories separately, we can understand the discursive evolution of the antiracism movement while taking into account the unique role that particular protests have in creating a platform for selected subsets of ideas.

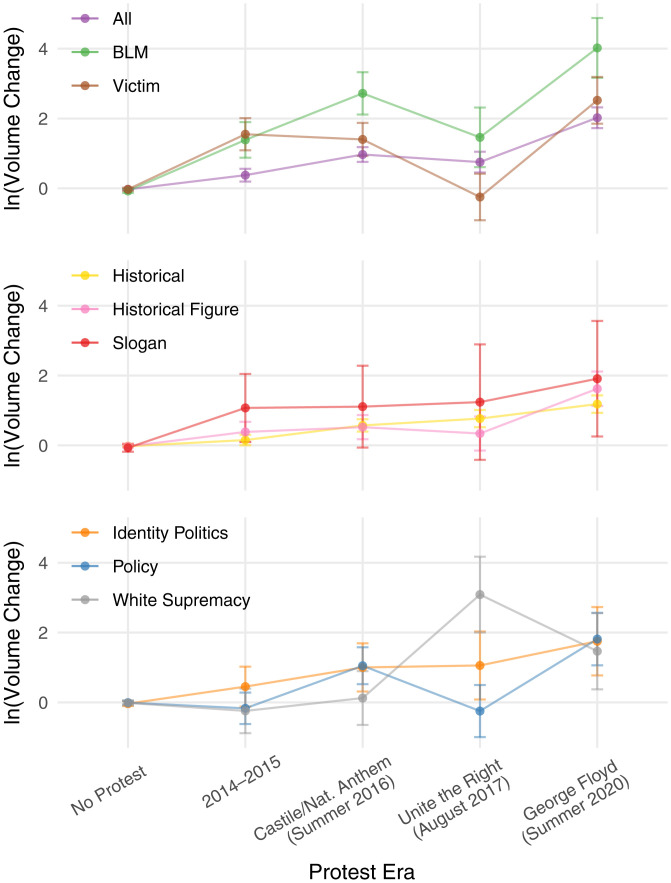

Search terms have been grouped into eight categories representing different components of the BLM agenda (SI Appendix, Table S1). Each category comprises two to eight terms. The next analysis disaggregates the coactivation analysis by protest event and type of term. Fig. 4 shows the way protest built up and cemented the visibility of the movement itself. Using a GAM, we estimated attention shifts during four protest waves: the initial protest wave subsequent to the deaths of Eric Garner, Michael Brown, Tamir Rice, and Freddie Gray; the protests following the deaths of Alton Sterling and Philando Castile and the first wave of National Anthem protests; the protests in response the Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, VA; and the demonstrations in response to George Floyd’s murder. Our baseline category consists of all other time periods outside of these protest waves, including less prominent protests. Then, we looked at the increase of attention to selected categories in these four time periods.

Fig. 4.

Expected change in search volume during protest. GAMs of expected change in search volume during a major protest during four protest “eras.” Search terms are grouped into eight categories, with an additional group, “All,” representing every search term. The first point in every plot represents model intercept: the expected change in search volume when a major protest is not occurring at any time between July 2014 and December 2020. All other points are the bootstrapped coefficients for expected change in search volume of protests of a particular era. Whiskers show 95% CIs.

Here we address a number of modeling issues. First, the spread of protests over a multiday period raises questions about selecting a unit of time during which attention increases may occur, because protest waves occur over multiple days and, in some cases, weeks. Typically, these begin with single-city protest events organized in response to a catalyzing event such as the shooting of a Black civilian by police. As these initial protests grow in attention, they spread to other cities, and attendance grows in an exponential manner before enthusiasm peaks. As shown in Figs. 2 and 3, the subsequent shifts in attention are “bursty” in that they are abrupt and clustered in time. We did not model the data with averages of moving time windows, because that would artificially decrease the variance of theoretically important events: Abrupt attention increases would be averaged out with many days of very little attention (days before the occurrence of the catalytic event.) Similarly, there are problems with using standardized units of time such as weeks or months, because protest waves often cross over multiple days and weeks, and they do so in nonuniform ways. Furthermore, protests began at unpredictable times, which suggests that uniform time bins cannot capture complete protest cycles.

As such, we developed an approach to binning that captures full protest cycles. For each major protest, beginning with the date of the initial event, we measure how many days it takes for 80% of terms to reach their maximum value in the 2 wk following the event. If any term reaches its maximum value in an 8-mo period (defined by Google’s maximum window for daily search data) outside the initial 80% marker, that day becomes the end point for the protest. The duration and catalyzing events for the protests are given in SI Appendix, Table S2. To produce commensurate periods for dates without protest, we bin the interceding days into periods of duration sampled from the protest periods. In order to limit the effect of random binning on the interceding dates, we bootstrap the binning 500 times. GAM results are reported in Fig. 4 for coefficients averaged over these 500 datasets. The GAM models predict search volume increases during BLM protest periods. We fit a model for each of the eight thematic categories, as well as a model for all terms. Each of these models has three components related to time (absolute time, calendar year, and one time-step lag of the dependent variable). The averaged outputs of these bootstrapped models are given in SI Appendix, Table S4.

Generally, all of the models represented by Fig. 4 demonstrate a superlinear increase in expected volume during protests. Our models indicate that over time more terms are spiking and that the spikes are growing larger. Furthermore, we can gain a better understanding of which protests are responsible for elevating particular types of ideas. During the 2014–2015 era, protest boosts all categories except “Policy” and “White Supremacy.” During the 2016 protests, some “policy” terms are expected to spike, but “White supremacy” terms show wide error bars, and there is no statistically significant effect of protest for related terms.

In 2017, however, BLM protests following the Charlottesville Unite the Right event show a somewhat different pattern. Most notably, searches for terms associated with “White supremacy” spike dramatically. Searches for the “Black Lives Matter” category decrease because the discourse is not focused around “police shootings” or police homicide more generally. Similarly, searches for past lynching “victims” do not spike. Searches for terms relating to the “history” of Black struggle, such as “Jim Crow” laws, do spike, but searches for “historical figures” do not, nor do terms for “policy.” “Identity politics” terms do spike; however the 95% CI is wide and comes close to zero, suggesting that some terms within the category spike and others don’t. Finally, the George Floyd protests show the greatest predicted change in volume for all categories except “White supremacy.”

Interest in BLM Is Sustained after the George Floyd Protests.

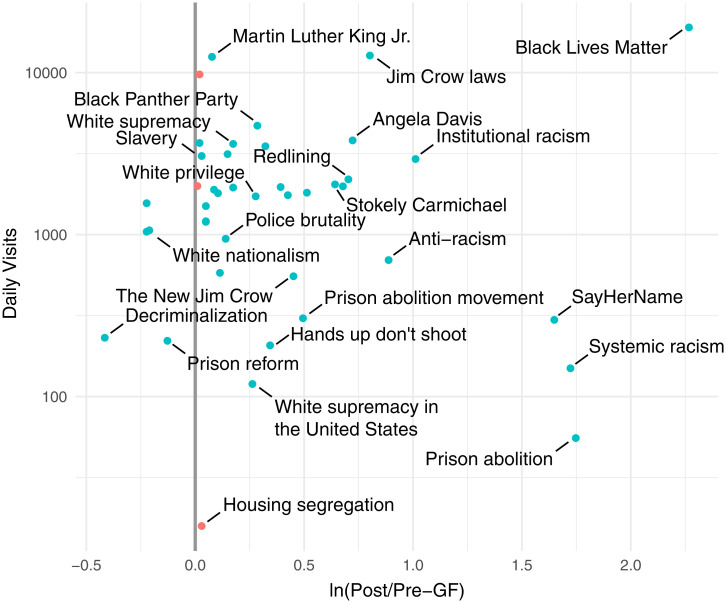

We have established that BLM-related searches spike dramatically during protests. Is attention to the BLM agenda sustained beyond protest periods? This section addresses questions 5 and 6—Does protest trigger sustained attention shifts for antiracism terms and does this “spill over” into other terms? Fig. 5 answers this question by demonstrating protracted interest in BLM following the George Floyd protests. Rather than focus on differences between protest waves, we examine one time period, August to December 2020, and ask which terms experienced simultaneous increases in total attention and increases in attention relative to the baseline for the same period in the previous year. This analysis uses Wikipedia search data because that platform provides raw counts of search terms, which allows us to standardize our attention measurements and directly compare terms. The x-axis in Fig. 5 indicates the logarithm of the ratio of Wikipedia searches in the post–and pre–George Floyd protest eras. The y-axis shows the raw frequency of searches for each term. This allows for simultaneously visualizing popularity and the growth of a term after protest. Fig. 5 shows a wide range of terms associated with BLM and antiracism more generally, all of which have analogs in the Google search terms used earlier in the study.

Fig. 5.

Shift in frequency of Wikipedia page visits after the George Floyd protests. Horizontal axis shows the ratio of expected daily visits during August to December of 2020 compared to the same calendar period of 2019. Vertical axis shows the expected number of page visits in August to December of 2020 (log scale). Blue dots are significant at P < 0.001 as estimated by t-test.

We test for sustained interest in BLM following the spring 2020 George Floyd protests. Using Wikimedia’s representational state transfer (REST) API, we collect daily page visits for 35 pages corresponding to our list of antiracist terms and terms associated with civil rights. Not all terms had corresponding pages, so these counts differ. We compare search behavior in two time periods: August to December in 2020 and 2019. We chose August to December because there will be a natural decrease in attention in the immediate aftermath of protest. We also want to focus on the period of time when students are likely to be searching for terms related to antiracism.

In order to prevent attention surges from biasing estimates away from their baseline, we apply a locally weighted scatterplot smoothing filter with a 60-d window to the daily volume time series. Further, we scale by average daily English Wikipedia visits for each period to account for increased Wikipedia use over time. Smoothing and scaling have slight effects on the results, whereas accounting for seasonality is critical to the accuracy of estimates.

We report post–vs. pre–George Floyd ratios in daily traffic and use a t-test to determine whether average daily visits increased in a statistically significant way following the protests. Additionally, in SI Appendix, Table S6, we report the change in daily volume for news media mentions, Google searches, and Twitter mentions of a set analogous terms using the same method. We find that many pages related to BLM have greater daily traffic post–George Floyd protests of 2020.

The three pages that experienced the most growth, relative to their pre–George Floyd baseline, are “Black Lives Matter,” “Prison abolition,” and “Systemic racism.” The terms that received the most page visits are “Black Lives Matter,” “Jim Crow laws,” and “Martin Luther King, Jr.” It is notable that “Martin Luther King, Jr.” remained popular, but its postprotest increase is very small. This is also true for the page “Slavery.” In contrast, “Black Lives Matter” and “Jim Crow laws” saw very large increases compared to the baseline. Similarly, “prison abolition movement” and “prison abolition” show increased attention, whereas the page “Prison reform” had fewer visits in 2020 than in 2019.

It is worth examining pages that did not have an increase in attention post–George Floyd. These include a number of policy issues that predate the BLM movement, such as decriminalization, prison reform, and housing segregation. An exception is “Redlining,” which refers to governmental and nongovernmental practices relating to housing segregation. This term shows a moderate increase in page visits. The data also show evidence for the hypothesis that BLM protest may have moderately stigmatized White nationalism. Pages for ideas that critique racial hierarchy, such as “White privilege” and “White supremacy,” show small increases in attention. By contrast, the page for “White nationalism” shows a decrease in daily visits. All other data sources show larger decreases in interest in “White nationalism” (46 to 76% reduction; SI Appendix, Table S6).

These modest changes also indicate that engagement with antiracism during and since the George Floyd protests has not focused on White supremacy generally but rather on specific facets of White supremacy and Black liberation. Pages for radical and relatively lesser-known 1960s civil rights leaders Angela Davis and Stokely Carmichael had large increases in traffic, whereas Martin Luther King Jr.’s page shows only a slight increase. One very important historical term, “Slavery” does not have a large increase postprotest. This suggests that protests are increasing the visibility of terms that are associated with BLM’s radical vision.

Opponents of BLM Generate Less Attention than BLM.

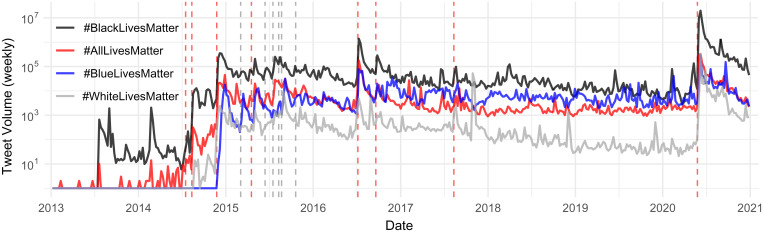

Protest can trigger counterprotesters who dispute a movement’s ideas or policy proposals. For this reason, it is important to examine negative discourse associated with BLM and antiracism more generally. Here, we look at Twitter activity to measure anti-BLM backlash and compare the attention given to its opponents. We track #BlackLivesMatter and three major countermovement hashtags (#AllLivesMatter, #BlueLivesMatter, and #WhiteLivesMatter) across time. Fig. 6 shows the prevalence of these hashtags from the origin of #BlackLivesMatter following the acquittal of the killer of Trayvon Martin, George Zimmerman, on July 13, 2013, through 2020. These data allow us to address question 7 and gain an understanding of how protests generate countermovements.

Fig. 6.

Weekly hashtag volume for #BlackLivesMatter and three opposing terms. Major and minor protest events are indicated by red and gray dashed lines, respectively.

The data show that countermovement discourse happens in tandem with the use of the BLM hashtag, which itself is prompted by street protest associated with police homicide. All three countermovement hashtags emerge or mature during the second half of 2014, parallel to BLM’s emergence as a protest movement. #BlackLivesMatter consistently has greater volume, an order of magnitude or more. There are two major baseline shifts apart from the initial emergence of BLM. The first begins with the homicide of Eric Garner and ends with the decisions by grand juries in late 2014 to not indict police officers Darren Wilson or Daniel Panteleo. A second major shift occurs after the George Floyd protests.

While #BlackLivesMatter and its opponents, #AllLivesMatter and #BlueLivesMatter, show fairly similar patterns, #WhiteLivesMatter, which is more overtly White supremacist, displays distinctive patterns. The use of #WhiteLivesMatter notably declines after the Unite the Right rally, whereas the others hold constant (P < 0.001; SI Appendix, Table S5). This may have happened because Twitter aggressively banned White nationalists in the 6 mo following the rally. Spikes in #WhiteLivesMatter in the years between Unite the Right and George Floyd, such as the Shelbyville, TN “White Lives Matter” rally on October 29, 2017, did not shift the baseline. This hashtag enjoyed a much larger increase in use than the others during the George Floyd protests, although it tapers with a slightly sharper slope than #BlackLivesMatter (P < 0.001; SI Appendix, Table S5). We find that the #WhiteLivesMatter tweet volume was 2.22 orders of magnitude greater after the killing of George Floyd (P < 0.001). However, by the end of 2020, its volume was still more than half an order of magnitude less than #AllLivesMatter or #BlueLivesMatter (<1,000 tweets per d), which are themselves dwarfed by the volume of tweets containing #BlackLivesMatter (>10,000 tweets per d).

This analysis illustrates the importance of using different data sources. Google search data for “Black Lives Matter” (Fig. 2) show a longer and more jagged, or episodic, emergence of public awareness of BLM. This is likely because Twitter may attract users who are more reactive to current events than the general public. This may also reflect underlying differences in how people use these digital platforms. On Twitter, one person may make dozens, even hundreds, of tweets with a particular hashtag, but a single individual is unlikely to make more than a handful of Google queries. In this sense, the more protracted emergence of BLM on Google search, as opposed to Twitter, reflects its more egalitarian character.

These data on the use of countermovement hashtags raise additional questions that can be answered with future research. Numerous scholars have noted that countermovements often intensify when movements use counterproductive tactics, such as riots (32), or are perceived to be using such tactics in experimental settings (33). This raises the hypothesis that tactical choices may have a positive effect on the use of countermovement discourse. Countermovement actions can also complicate this dynamic. In some cases, countermovements can be perceived to be intransigent and thus improve the standing of the original movement, as observed for LGBT+ activism (34) and Occupy Wall Street activism (35). In the BLM case, countermovement actions, such as the Unite the Right assembly in Charlottesville, can turn violent and thus undermine their position. Future research can more thoroughly code BLM events according to tactic and investigate the relationship of tactical choice, public perceptions, and countermovement behaviors.

Discussion

The purpose of this study is to measure and assess the cultural impact of protest. In summary, we focused on the association between BLM protests and search behaviors on platforms such as Google, Twitter, and Wikipedia. We also provided evidence from older forms of media such as books and national news organizations. We found large and consistent effects: Large protests were followed by large increases in attention given to terms associated with BLM. Furthermore, there is evidence that the attention was sustained in many cases. Antiracist discourse received much more attention after the wave of protests against George Floyd’s murder, and the attention given to antiracist terms remained much higher in December 2020 than in the same period in the previous year. Taken together, our evidence indicates that BLM protests succeeded in drawing attention to antiracist theory in a large-scale and consistent way.

Here, it is important to situate our findings within scholarly discussions of social change. This study focuses on the relationship between protest and attention. Much of the analysis focuses on protest as a factor encouraging people to investigate and employ antiracist ideas. However, sociological research on the relationship between culture and political actions suggests an important contextualization of our findings. There is a recursive relationship between protest and attention: Protest generates attention, and attention generates protest. Thus, protest is part of a continuous cycle whereby changes in ideas facilitate political action, and these actions can further cement ideas into the popular imagination.

These data refine the recursive model of culture and action. At times, protests can become a primary mover of public discourse when they are large, spontaneous reactions to catalytic events, such as the killing of a Black person by police. This is especially true of the large, multicity contagious protest periods. It is important to emphasize why such political actions can be so effective in changing how the public understands social problems. In the case of BLM, racialized police homicide, and police homicide more generally, has been a fact of American life for decades. What is new is the response of BLM organizers to consistently leverage these events to generate media attention, aided by new media technologies, such as social media and the mass availability of recording equipment for citizen journalism. This initial push by organizers sets off a cascading feedback loop of 1) dissemination of information about the initial event and earlier protests, 2) public attention, 3) new protests coordinated by BLM organizers, and 4) protest attendance by sympathizers. This cycle is enabled by prior changes in how people think about racial inequality, and, at the same time, the ideas promoted by these protests may frame future discussions of race.

This research also contributes to ongoing discussions of how activists disseminate their ideas in a modern digital society. Computational social scientists have argued that movements operate in a larger “cultural environment,” which includes social media and traditional news media (36). This line of research depicts the link between political action and cultural change in a fairly straightforward way: Activists and their organizations use their resources to amplify the message they prefer in an attempt to have opinion leaders and the public adopt their view (37–40). Particular organizations try to reframe issues by publicizing new policies, introducing new terms, and attracting attention to some issues over others. Often, activists will try to have highly prestigious elites or organizations promote their view in an attempt to legitimize their demands.

The pattern of BLM protest and vocabulary use indicates a different path to cultural change. BLM is a decentralized movement that does not rely on large organizations that lobby for its positions. Rather, it is a movement that has primarily mobilized followers through social media. Furthermore, the protests that have had the largest impact on the use of antiracist vocabulary are often the ones where footage of police violence was widely circulated to the public. This suggests that BLM is a movement whose cultural impact is initially established through the memorialization of specific events. Fig. 4 is suggestive in this regard. Earlier waves of protests increased attention to victims of police violence, which then led to a rise in attention to broader ideas criticizing American society, such as White privilege and systemic racism. Thus, BLM affects American culture by using protests to focus attention first on individual victims and then draw attention to larger policy issues.

The public’s use of a new lexicon is complex. The rise of social movements often triggers dispute and “countermovements” (41). Individuals who oppose a movement may try to mitigate the adoption of a movement’s ideas through the introduction of their own distinct vocabulary. For example, Ince et al. (15) found that hashtag networks for BLM on Twitter frequently included “countermovement” phrases such as “All Lives Matter.” The analysis of countermovement hashtags in the previous section deepens this point. Valence is a related issue. It is possible that movement opponents might use a term in a very different way than originally intended. For example, BLM supporters may use the phrase “White supremacy” to denote patterns of prejudice, while White nationalists may use the same term as a rallying cry. We offer two observations with respect to this point. First, the data presented in the section on countermovements suggest that such usage does occur, although it is small in magnitude. The counter-BLM movement did appear after protest, and, paradoxically, BLM may have provided an opportunity for a small community of White nationalists to propagate their message. Second, computational techniques such as neural network–based natural language understanding and sentiment analysis can be used in future research to establish how much usage of antiracist terms comes from advocates and opponents.

It is also worth noting that people may have significantly different understandings of what policy reforms might be needed to implement a movement’s demands. These differing policy responses reflect people’s beliefs about the nature of a particular social problem such as racism. Dixon and Dundes (42) note that people invoke “racial imaginaries,” or visions of the nature of racial inequalities, when they interpret events such as the shooting of George Floyd. Some will see police violence as idiosyncratic and only a sign of “a few bad apples,” while others see these events as evidence of a larger pattern of systemic racism. This argument suggests that shifts in how people interpret social problems, such as police violence, set the stage for movements like BLM and how people use and interpret the antiracist vocabulary introduced by the movement.

Limitations and Questions for Future Research.

Finally, we review study limitations that can be addressed with future research. First, this study tracks aggregate use patterns. We do not collect information on the individuals who generate the data used in this study, so it is not possible to link antiracist vocabulary to individual characteristics such as age, gender, socioeconomic status, education, race, or ideological positions. However, other researchers have explored the individual factors associated with supporting BLM or using antiracist discourse. Recent polling data suggest that approval of BLM and its policies is correlated with age, race, and political attitudes. In a recent poll of undergraduate students at a midwestern university, Ilchi and Frank (43) find that race and attitudes toward the police correlate with support for BLM. Updegrove et al. (44) used data from a nationally representative sample of 2,114 people to show that older, conservative, and male respondents are less likely to support BLM. Arora and Stout (45) use data from an experiment to show, among other things, that political party is a strong predictor of when a respondent will have a positive feeling toward a letter of support for BLM. None of these studies addresses digital behavior, but they strongly suggest that the use of antiracist terminology would be strongly associated with age, political attitudes, and other social and political characteristics, a hypothesis that can be addressed with future research. These studies can be brought into a dialogue with digital trace data to provide a more comprehensive and nuanced understanding of how BLM protests of the 2010s resulted in large-scale cultural change.

Second, this research does not examine how antiracist words are used. For example, a person who supports BLM is counted in the same way as a person who opposes the movement but uses their name in a social media post. Computational techniques such as sentiment analysis and neural network language models can be used to model how words are used. Third, this is a study of the consequences of the Black Lives Movement through 2020. We found evidence that antiracist vocabulary found greater usage after June 2020, but future political developments could reverse or mitigate that trend.

Four, we note that this study does not seek to establish a causal link between street protest and discursive change. Rather, this is a descriptive study showing that protest is associated with the heightened visibility of an antiracist lexicon, which allows people to create a space where such terms can be discussed. Eventually, the amplification of antiracist discourse might facilitate political change. Subsequent research might search for naturally occurring random variations in protest in order to have the sufficient counterfactual cases needed for a causal identification.

Here we present two related questions for future research. This study does not examine the way discursive change and agenda setting leads to the enactment of policies associated with BLM and antiracism, such as ending qualified immunity for police officers; reparations; or diversity, equity, and inclusion initiatives. Social scientists can track the adoption of these policies to test the hypothesis that a discursive shift precedes the institutionalization of social change. Social scientists can also study the cultural impact of BLM and antiracism on the youngest people in society. A consistent finding in public opinion research is that cohort replacement is a very important driver of social change. Already, multiple studies have begun to document the ways that BLM has changed the way youth think about inequality and how parents speak to their children about race (46).

Conclusion

Often, a movement’s “success” is reflected in widespread acceptance of the movement’s goals, or institutional change such as legislation. Here, we document BLM’s successful injection of the movement’s framing into public discourse. These findings are relevant for researchers interested in social movements and long-term cultural change for two reasons. First, the introduction of antiracist discourse could reflect a pivot toward an alternative pathway to secure a more just future. The participants in the events of 2020 (and earlier BLM protests) have an advantage that previous generations of activists did not: They witnessed the shortcomings of civil rights discourse, diversity and inclusion discourse, and the liberal discourse of “reform.” Today’s activists are not rejecting older movement discourse so much as they are exposing the limitations of such framings. Second, the murder of George Floyd was a catalyst for an interracial coalition of actors and a key moment for organizers who are invested in social change. Our exploration of BLM is framed by the killing of Eric Garner in 2014 and that of George Floyd 6 years later. These events look remarkably similar: middle-aged Black men recorded on video begging for their lives as they are choked to death by police in the street. Yet the collective response to these events is starkly different. In 2014 and 2015, the discursive impacts do not go far beyond the recognition of the existence of racialized police homicide. Progressively, the response evolved to become more expansive, beyond police killings, even beyond policing, to the social structures that create and maintain the conditions of Black life in the United States. This study demonstrates how political organizers have leveraged these tragic events to produce a new collective understanding of society.

The broad discursive response to the George Floyd protests shows it is a mistake to characterize BLM as fundamentally, or exclusively, concerned with policing or even the carceral state. Positions taken by BLM organizers and rhetoricians in publications, interviews, and speeches make clear that policing is only one facet of Black emancipatory politics under the banner of BLM. Legislative and Democratic platform debates have barely touched on the abundance of societal choices leading to the marginalization, exploitation, and disposal of Black life. The deliberate exclusion of Black families from the postwar growth of the middle class and creation of White suburbs (with White suburban tax bases and schools) and Black urban ghettos (47), the withdrawal of already insufficient public funding of community and mental healthcare programs which began in the 1980s and continues today (48, 49), and the dramatic growth of incarceration as the solution to social neglect of Black communities (50) are almost entirely absent from popular media and political discourse, even when it purports to examine and remedy the social position of African Americans.

Even with this awareness, presenting this framing of BLM in the design and discussion of this study has been challenging for its authors. In part, this is because it is easy and perhaps necessary to engage with the dominant mode of discourse. But it is also because the real problems BLM attempts to address, which include the problems of policing, pose a tremendous moral and social structural challenge if we are to begin to resolve them. The narrative and most of the real outcomes of the 1960s Civil Rights Movement have not come close to addressing these problems, and instead focused on the politically and structurally simpler problem of equal protection under the law and tokenized representation in White institutions. BLM is, in part, a response to limited social change and increased policing of Black communities coming out of the social movements of the 1960s. Beyond this, the past 50 years have seen new assaults on Black and other primarily urban minority communities as well as on the working class more generally with the weakening of funding for social programs and education under political control of both parties, which we generally refer to as neoliberalization (49). We implore researchers focusing on BLM and other political actors who want to realize Black liberation to reorient toward this broader framing of BLM. Understanding BLM as a movement that arose in response to the limits of the civil rights era and amid rampant repression of Black communities challenges notions of progress held by many progressives. Addressing the problems raised by this framing may come at the cost of comfort, both emotional and material, for those who occupy positions of racialized privilege. Making this sacrifice offers no guarantee, but it is critical if we are to realize the incomplete goals of previous movements and work toward the restoration of Black communities and Black life.

Materials

Data Sources.

To measure the use of antiracist vocabulary, we obtained data from multiple sources: Google Trends, Google Books, national news, Wikipedia, and Twitter. Each data platform provides unique information about how people are using different terms. SI Appendix provides additional analyses incorporating multiple data sources when appropriate.

Google search.

Google search data were retrieved using the Google Trends API. Google limits the resolution at which data can be downloaded. Daily search volumes were retrieved in 8-mo chunks overlapping by 4 mo. Google does not give access to absolute search volumes and uses a relative 0 to 100 scale where 100 is the maximum daily searches for the requested period. In the GAMs, measurements are taken as a ratio, such that the relative measurements yield the same result as absolute ones.

Google N-grams books.

Google N-grams data were downloaded from http://storage.googleapis.com/books/ngrams/books/20200217/eng/totalcounts-1 and contain measurements through 2019.

Wikipedia page visits.

Wikipedia page visits data were downloaded using the Wikimedia REST API (https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/).

Daily news coverage.

We searched keywords that related to BLM through the Media Cloud API (27) to gather the number of publications that mentioned each keyword per day from January 1, 2013 to December 31, 2020. The source collection contains a total of 271 US national-level news publications, including 17 radio (e.g., NPR) and TV (e.g., CNN) broadcast, 114 digital native (e.g., Vox.com), 108 print native (e.g., NYT), and four others (e.g., Reuters).

Twitter.

Daily counts of tweets were collected through the academic track of Twitter API version 2.0. The academic track allows researchers to access the full archive database of Twitter and collect the daily volume data of tweets that contained searched keywords. See details of the API documentation at https://developer.twitter.com/en/docs/twitter-api/tweets/counts/introduction.

BLM-Related Protests.

The independent variable is obtained from multiple BLM protest datasets that researchers have collected to study the movement. The “Elephrame” dataset is an open source dataset collected since 2014, curated by Alisa Robinson with aid from site users. Data were scraped from https://elephrame.com/textbook/BLM/chart on January 8, 2021. The dataset collected by Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) uses automated searchers to collect news reports of US protests (BLM and otherwise) since May 2020. Data were retrieved using the ACLED Data Export Tool (https://acleddata.com/data-export-tool/) on January 15, 2021.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the Racial Justice Research fund at Indiana University for sponsoring this work. We also thank the following scholars for their support and critical commentary: Michael Schultz, Maria Pope, Victor Ray, Pamela Oliver, Eric Grodsky, James Shanahan, Kenzie Givens, Bradi Heaberlin, Neal Caren, Rob Potter, Marit Rehavi, David S. Meyer, Clem Brooks, and Brian Powell. We thank in particular the anonymous peer reviewers who provided thoughtful and constructive criticism that helped improve the paper. All remaining errors are our own. This research was funded with a grant from the Racial Justice Research Fund at Indiana University, Bloomington. Z.O.D. and H.Y.Y. were partially funded by National Science Foundation Research Traineeship Grant 1735095 “Interdisciplinary Training in Complex Networks and Systems.”

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

See online for related content such as Commentaries.

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.2117320119/-/DCSupplemental.

Data Availability

All study data were sourced from publically available platforms. These data are compiled at https://osf.io/ubptz/. Data processing and modeling code are available upon request.

References

- 1.McAdam D., Su Y., The war at home: Antiwar protests and congressional voting, 1965 to 1973. Am. Sociol. Rev. 67, 696–721 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gillion D. Q., The Political Power of Protest: Minority Activism and Shifts in Public Policy (Cambridge University Press, 2013). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gillion D. Q., Governing with Words: The Political Dialogue on Race, Public Policy, and Inequality in America (Cambridge University Press, 2016). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Noel H., Political Ideologies and Political Parties in America (Cambridge University Press, 2014). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee T., Mobilizing Public Opinion: Black Insurgency and Racial Attitudes in the Civil Rights Era (University of Chicago Press, 2002). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weaver A. A., Does protest behavior mediate the effects of public opinion on national environmental policies? A simple question and a complex answer. Int. J. Sociol. 38, 108–125 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Giugni M., Useless protest? A time-series analysis of the policy outcomes of ecology, antinuclear, and peace movements in the United States, 1977-1995. Mobilization 12, 53–77 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mann L., Protest movements as a source of social change. Aust. Psychol. 28, 69–73 (1993). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boyles A. S., You Can’t Stop the Revolution: Community Disorder and Social Ties in Post-Ferguson America (University of California Press, 2019). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kudesia R. S., Emergent strategy from spontaneous anger: Crowd dynamics in the first 48 hours of the Ferguson shooting. Organ. Sci. 32, 1210–1234 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Williamson V., Trump K. S., Einstein K. L., Black Lives Matter: Evidence that police-caused deaths predict protest activity. Perspect. Polit. 16, 400–415 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Klein Teeselink B., Melios G., Weather to protest: The effect of Black Lives Matter protests on the 2020 presidential election. SSRN [Preprint] (2021). https://ssrn.com/abstract=3809877. Accessed 20 May 2021.

- 13.Campbell T., Black Lives Matter’s effect on police lethal use-of-force. SSRN [Preprint] (2021). https://ssrn.com/abstract=3767097. Accessed 22 February 2021.

- 14.Sawyer J., Gampa A., Implicit and explicit racial attitudes changed during Black Lives Matter. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 44, 1039–1059 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ince J., Rojas F., Davis C. A., The social media response to Black Lives Matter: How Twitter users interact with Black Lives Matter through hashtag use. Ethn. Racial Stud. 40, 1814–1830 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brown M., Ray R., Summers E., Fraistat N., #sayhername: A case study of intersectional social media activism. Ethn. Racial Stud. 40, 1831–1846 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wilkins D. J., Livingstone A. G., Levine M., Whose tweets? The rhetorical functions of social media use in developing the Black Lives Matter movement. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 58, 786–805 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rojas F., From Black Power to Black Studies: How a Radical Social Movement became an Academic Discipline (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2010). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bartley T., Koos S., Samel H., Setrini G., Summers N., Looking behind the Label: Global Industries and the Conscientious Consumer (Indiana University Press, 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Summers N., Ethical consumerism in global perspective: A multilevel analysis of the interactions between individual-level predictors and country-level affluence. Soc. Probl. 63, 303–328 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 21.King B. G., Soule S. A., Social movements as extra-institutional entrepreneurs: The effect of protests on stock price returns. Adm. Sci. Q. 52, 413–442 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bonilla-Silva E., Racism without Racists: Color-Blind Racism and the Persistence of Racial Inequality in the United States (Rowman & Littlefield, 2006). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Feagin J., Systemic Racism: A Theory of Oppression (Routledge, 2013). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vasi I. B., Walker E. T., Johnson J. S., Tan H. F., “No fracking way!” documentary film, discursive opportunity, and local opposition against hydraulic fracturing in the United States, 2010 to 2013. Am. Sociol. Rev. 80, 934–959 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 25.McCammon H. J., Muse C. S., Newman H. D., Terrell T. M., Movement framing and discursive opportunity structures: The political successes of the us women’s jury movements. Am. Sociol. Rev. 72, 725–749 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Clark A. D., Dantzler P. A., Nickels A. E., “Black Lives Matter: (Re)framing the next wave of black liberation” in Research in Social Movements, Conflicts and Change, Solomon J., Ed. (Emerald, 2018), pp. 145–172. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roberts H., et al., Media cloud: Massive open source collection of global news on the open web. ArXiv [Preprint] (2021). https://arxiv.org/abs/2104.03702v3. Accessed 15 May 2021.

- 28.Benford R. D., Snow D. A., Framing processes and social movements: An overview and assessment. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 26, 611–639 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Turner D., “#Resistcapitalism to #fundblackfutures: Black youth, political economy, and the twenty-first century black radical imagination” in Abolition: A Journal of Insurgent Politics, Abolition Collective , Ed. (Abolishing Carceral Society, Common Notions, 2018), vol. 1, pp. 217–227. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu X., Duyn J. H., Time-varying functional network information extracted from brief instances of spontaneous brain activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 4392–4397 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Singer P., et al., “Why we read Wikipedia” in Proceedings of the 26th International Conference on World Wide Web, Barrett R., Ed. (Association for Computing Machinery, 2017), pp. 1591–1600. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wasow O., Agenda seeding: How 1960s black protests moved elites, public opinion and voting. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 114, 638–659 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ayoub P. M., Page D., Whitt S., Pride amid prejudice: The influence of LGBT+ rights activism in a socially conservative society. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 115, 467–485 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fetner T., How the Religious Right Shaped Lesbian and Gay Activism (University of Minnesota Press, 2008). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Milkman R., Luce S., Lewis P. W., Changing the Subject: A Bottom-Up Account of Occupy Wall Street in New York City (Russell Sage, 2013). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bail C. A., The cultural environment: Measuring culture with big data. Theory Soc. 43, 465–482 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Karpf D., Analytic Activism: Digital Listening and the New Political Strategy (Oxford University Press, 2016). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Van Laer J., Van Aelst P., Internet and social movement action repertoires: Opportunities and limitations. Inf. Commun. Soc. 13, 1146–1171 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Maghrabi R. O., Salam A. F., “Social media, social movement and political change: The case of 2011 Cairo revolt” in Proceedings of the International Conference on Information Systems ICIS 2011, Galletta D. F., Liang T.-P., Eds. (Association for Information Systems, 2011), Abstr. 8. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tufekci Z., Twitter and Tear Gas (Yale University Press, 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Meyer D. S., Staggenborg S., Movements, countermovements, and the structure of political opportunity. Am. J. Sociol. 101, 1628–1660 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dixon P. J., Dundes L., Exceptional injustice: Facebook as a reflection of race-and gender-based narratives following the death of George Floyd. Soc. Sci. 9, 231 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ilchi O. S., Frank J., Supporting the message, not the messenger: The correlates of attitudes towards Black Lives Matter. Am. J. Crim. Justice 46, 377–398 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Updegrove A. H., Cooper M. N., Orrick E. A., Piquero A. R., Red states and black lives: Applying the racial threat hypothesis to the Black Lives Matter movement. Justice Q. 37, 85–108 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 45.Arora M., Stout C. T., Letters for black lives: Co-ethnic mobilization and support for the Black Lives Matter movement. Polit. Res. Q. 72, 389–402 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 46.Underhill M. R., Parenting during Ferguson: Making sense of white parents’ silence. Ethn. Racial Stud. 41, 1934–1951 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 47.Freund D. M., Colored Property: State Policy and White Racial Politics in Suburban America (University of Chicago Press, 2007). [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nelson A., Body and Soul: The Black Panther Party and the Fight against Medical Discrimination (University of Minnesota Press, 2011). [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hohle R., Race and the Origins of American Neoliberalism (Routledge, 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 50.Alexander M., West C., The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness (New Press, 2010). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All study data were sourced from publically available platforms. These data are compiled at https://osf.io/ubptz/. Data processing and modeling code are available upon request.