Abstract

Background:

Distinguishing men with aggressive from indolent prostate cancer is critical to decisions in the management of clinically localized prostate cancer. Molecular signatures of aggressive disease could help men overcome this major clinical challenge by reducing unnecessary treatment and allowing more appropriate treatment of aggressive disease.

Methods:

We performed a mass spectrometry-based proteomic analysis of normal and malignant prostate tissues from 22 men who underwent surgery for prostate cancer. Prostate cancer samples included Grade Groups (3 to 5), with 8 patients experiencing recurrence and 14 without evidence of recurrence with a mean of 6.8 years of follow-up. To better understand the biological pathways underlying prostate cancer aggressiveness, we performed a systems biology analysis and gene enrichment analysis. Proteins that distinguished recurrent from non-recurrent cancer were chosen for validation by immunohistochemical analysis on tissue microarrays containing samples from a larger cohort of patients with recurrent and non-recurrent prostate cancer.

Results:

24,037 unique peptides (false discovery rate < 1%) corresponding to 3,313 distinct proteins were identified with absolute abundance ranges spanning seven orders of magnitude. Of these proteins, 115 showed significantly (P < 0.01) different levels in tissues from recurrent versus non-recurrent cancers. Analysis of all differentially expressed proteins in recurrent and non-recurrent cases identified several protein networks, most prominently one in which approximately 24% of the proteins in the network were regulated by the YY1 transcription factor (adjusted P < 0.001). Strong immunohistochemical staining levels of three differentially expressed proteins, POSTN, CALR, and CTSD, on a tissue microarray validated their association with shorter patient survival.

Conclusions:

The protein signatures identified could improve understanding of the molecular drivers of aggressive prostate cancer and be used as candidate prognostic biomarkers.

Keywords: prostate cancer, recurrent, PSA, POSTN, CALR, CTSD, YY1, biomarker, prognosis

INTRODUCTION

Prostate cancer is the most commonly diagnosed cancer in US males and is the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths.1 The introduction of prostate-specific antigen (PSA) screening in the 1980s produced a dramatic shift in prostate cancer stage at presentation such that greater than 90% of men currently harbor localized disease.2 Accompanying this shift was an increase in prostate cancer incidence, with an increased number of men with low grade, indolent disease, raising concerns about overdiagnosis and overtreatment of localized disease. Based on these concerns, active surveillance (AS) has become accepted as initial management of low-risk prostate cancer. However, up to 50% of men on AS progress within 5 to 10 years of surveillance, and can die of their disease.3 Likewise, a large portion of men who undergo immediate treatment for intermediate and high risk localized prostate cancer experience disease recurrence, necessitating additional therapies. Management of localized prostate cancer could be aided significantly by better stratifying patients with low-risk cancer most likely to do well on surveillance and better identifying men with high-risk cancer where initial treatment with multimodal therapies could decrease disease recurrence.4

For the past two decades, genomic and transcriptomic approaches have improved our understanding of the molecular changes in prostate cancer initiation and progression and have fueled development of prognostic gene signatures to help with management.5–10 However, the independent predictive power of most of biomarker panels are modest at best and rigorous validation studies are often lacking, leading a recent American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) Expert Panel to recognize the potential of tissue-based molecular biomarkers for risk stratification when added to standard clinical parameters, but only endorsing their use in limited situations when used in combination with routine clinical factors where a clinical decision would likely be affected.11 In addition, transcriptomic tests require specialized laboratories with complex workflows, making them relatively expensive to administer. For many malignancies, protein-based biomarkers, including PSA, have been used in diagnosis, disease monitoring, and treatment selection, with new tissue-based biomarkers being added as companion diagnostics to novel targeted therapies. Many tissue-based biomarkers can be measured in pathology services by immunohistochemistry (IHC), making this technique inexpensive and widely available. Currently, there are very few IHC disease biomarkers routinely used in prostate cancer, and none that are routinely used in prognostication. Previous studies have identified several prognostic biomarker candidates, including annexin A3,12 matrix metalloproteinases and their inhibitors,13 and periostin,14 PTEN,15 and AZGP1.16 Despite these successes, there are very few large-scale proteomics analyses of prostate cancer with the goal of identifying new biomarkers of prognosis.

In recent years, new liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) technologies have allowed systematic studies capable of identifying, quantifying, and characterizing thousands of proteins in biological and clinical samples.17 Differentially expressed proteins can be used to extract biological insights through identification of common biological pathways. However, this approach is encumbered by challenges involving corrections for statistical significance when biologically relevant differences in protein levels can be subtle and therefore challenging to identify over inherent experimental and biological noise. Interpretation of significantly modulated proteins can also be challenging without the context of their relationships or interactions.18 Finally, LC-MS experiments are often subject to under-sampling of peptides during analysis, thereby reducing the overlap of peptide identifications between samples. To help overcome this challenge, we performed LC-MS based proteomic analyses on patient prostate cancer tissue samples and applied a systems biology statistical model to discern proteins and pathways that differ between recurrent and non-recurrent prostate cancer cases treated surgically.19 This approach involves using a weighted average of protein quantitation values across technical replicates, and assigning proteins to categories, allowing categories of proteins to be compared instead of relying on comparison of individual proteins identified in each patient sample.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Prostate Tissue Samples

Prostate tissue samples used in this study were obtained from 22 men who underwent radical prostatectomy for the treatment of clinically localized prostate cancer (Table 1). Prostate tissues and clinical information were collected after obtaining patient informed consent under an Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved protocols (protocol numbers 59490 and 13873). Clinical data included patient age, pre-operative serum Prostate Specific Antigen (PSA) levels, pathological grade and stage of the cancer, and follow-up information. Of the 22 patients included, 8 cases had recurrence of their cancer based on a detectable serum PSA, while 14 showed no recurrence after a mean follow-up of 6.8 years. Samples were stored at −80°C until analysis. Frozen prostate cancer tissues initially were chosen based on the histological findings from adjacent FFPE tissue. Frozen sections were performed on the top and bottom of each selected tissue sample and hematoxylin and eosin stained slides were reviewed by a pathologist. Cancer samples with at least 90% of the epithelial cells determined to be cancerous, and paired non-cancer samples containing no malignant epithelium from the same patients were selected for analysis.

Table 1.

Patient Demographics and Clinical Characteristics

| Non-Recurrent (n = 14) | Recurrent (n = 8) | Population Bias4 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| Mean (SD) | 59.7 (5.3) | 65.6 (8.6) | p - value > 0.05 |

| Median | 59.5 | 68 | |

| Q1, Q3 | 56.5, 62.8 | 57.8, 69.8 | |

| Range | (50 – 69) | (54 – 79) | |

| Gleason Score | |||

| Range | (7 – 8) | (7 – 8) | p - value > 0.03 |

| Preoperative PSA level (ng/mL) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 8.5 (7.6) | 11.5 (6.5) | p - value > 0.05 |

| Median | 6.4 | 9.8 | |

| Q1, Q3 | 5.4, 9.6 | 6.2, 14.9 | |

| Range | (1.9 – 32.6) | (5.4 – 22.5) | |

| Prostate size (g) 1 | |||

| Mean (SD) | 53.7 (14.1) | 67.4 (58.9) | p - value > 0.05 |

| Median | 50.5 | 50.5 | |

| Q1, Q3 | 42.3, 63.5 | 41, 54.5 | |

| Range | (36 – 86) | (36 – 212) | |

| Cancer Index (cm3) 2 | |||

| Mean (SD) | 3.3 (3.2) | 7.5 (4.5) | p - value > 0.02 |

| Median | 2.2 | 7.3 | |

| Q1, Q3 | 1.2, 3.8 | 3.8, 10.2 | |

| Range | (0.1 – 11.3) | (1.8 – 15.1) | |

| Total Cancer Volume (cm3) 3 | |||

| Mean (SD) | 3.6 (3.3) | 7.5 (4.5) | p - value > 0.02 |

| Median | 3 | 7.5 | |

| Q1, Q3 | 1.3, 4.2 | 3.8, 10.2 | |

| Range | (0.1 – 12.1) | (2.2 – 15.1) | |

| PSA at the time of failure (ng/mL) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 0.4 (0.4) | ||

| Median | 0.2 | ||

| Q1, Q3 | 0.1, 0.5 | ||

| Range | (0.1 – 1.2) | ||

| Time between prostatectomy and failure (days) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 16.2 (18.6) | ||

| Median | 8.4 | ||

| Q1, Q3 | 5.5, 16.9 | ||

| Range | (3.2 – 57.8) | ||

| Time after prostatectomy follow-up (months) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 81.6 (25.3) | ||

| Median | 74.2 | ||

| Q1, Q3 | 69.2, 103.2 | ||

| Range | (36.1 – 121.7) | ||

Note:

After radical prostatectomy,

Volume of the 1st cancer/largest,

Volume of all smaller cancer/incidental including the index cancer, and

Mann-Whitney U Test p-value for two independent samples.

Sample Preparation and LC-MS Analysis

Proteins from tissue samples were extracted by adding 800 μL of lysis buffer containing 12.5 mM Tris pH 8.0 (Fisher Scientific), 0.5 mM EDTA (EMD Inc.), 7.5 M urea (Sigma- Aldrich), and 1X protease inhibitor and homogenizing tissues with a PRO-250 (ProScientific) homogenizer. Following lysis, samples were further emulsified using a Branson probe sonicator (Fisher Scientific) with a vibrational amplitude set to 40% and exposing the samples to three 10 s ultrasonication cycles. Samples were centrifuged at 14,000 g for 10 min at 4 °C. Supernatant was collected and proteins were quantified by a micro-bicinchoninic acid (micro BCA) protein assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Disulfide bonds were reduced using 50 μg of protein with Tris(2carboxyethyl) phosphine (TCEP, Sigma-Aldrich) at a final concentration of 10 mM in HPLC grade water (Fisher Scientific) and incubated at room temperature for 1.5 hours. Free sulfhydryl groups were alkylated by adding iodoacetamide (Acros Organics) in 1.5-fold molar excess of TCEP and incubated at room temperature in the dark for 45 min. Samples were digested with sequencing grade modified trypsin (Thermo Fisher Scientific) in a 1:25 enzyme-to-protein ratio and diluting urea concentration to 300 mM using 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate (Sigma-Aldrich). Samples were incubated at 37 °C overnight, dried using a speed vacuum and desalted with C18 ZipTip columns (EMD Millipore). Peptides were reconstituted in 25 μL of 0.1% formic acid (Fisher Scientific) in HPLC grade water for LC-MS analysis.

A Dionex Ultimate Rapid Separation nanoLC 3000 system (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used to load 3 μL of the tryptic peptide mixture onto a C18 trap column (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Reversed phase liquid chromatography was used to separate the tryptic peptides on a 25 cm long C18 column (New Objective) packed with Magic C18 AQ resin (Michrom Bioresources). The chromatography gradient consisted of Buffer A (0.1% formic acid in water) and Buffer B (0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile (Fisher Scientific)) with initial conditions set at 98% and 2% respectively for the first 10 min. Buffer B was increased to 35% over 100 min, increased to 85% over 7 min, and held constant for 5 min before decreasing buffer B to 2% for 15 min. The flow rate was set to 0.6 μL/min. Eluted peptides were ionized with a 1.8 kV on a Nanospray Flex Ion Source (Thermo Fisher Scientific) coupled to a LTQ Orbitrap Elite mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) with capillary temperature set to 200 °C. The Orbitrap was set to acquire full MS1 scans at a resolution of 60,000 from m/z 400 to 1800, with AGC set to 1×106, and maximum injection time of 100 ms. Data dependent acquisition was used to perform MS/MS on the top 10 most abundant +2 and +3 ions (isolation width set to 2.0 Da) in the MS1 scan using collision-induced-dissociation (35 eV, 10 ms). Product ions were detected in the ion trap with 1×106 AGC (50 ms maximum injection time). Dynamic exclusion was enabled for 30 s with an exclusion width of ±1.5 Da. All samples were analyzed in triplicate.

Data Analysis

LC-MS data files were searched using Byonic 2.11.0 (Protein Metrics, San Carlos, CA) against the Swiss-Prot human reference proteome database (2017; 20,484 entries). Search parameters included trypsin digestion with a maximum of two missed cleavages, precursor mass tolerance of 0.5 Da, and fragment mass tolerance of 10 ppm. Fixed cysteine carbamidomethylation, variable methionine oxidation, and asparagine deamination, were also specified. Peptide identifications were filtered to remove those with a >1% false discovery rate (FDR) and those identified with less than two spectra. Quantitative information was extracted from MS1 spectra of all identified peptides using an in-house R script based on the MSnbase package20 as the area under the curve of the extracted ion chromatogram of all remaining peptides after the alignment of the chromatographic runs. Protein abundances were determined using the Generic Integration Algorithm,21 in which each peptide identification extracted area under the curve (AUC) from each prostate cancer tissue sample was compared to the corresponding signal from the non-cancerous tissue sample, and then assigning to those ratios a statistical weight according to the WSPP model.21 Next, the quantitative information was integrated at the protein level, controlling the validity of the null hypothesis at each level (spectrum, peptide, and protein) by plotting the cumulative distributions. Finally, the quantitative information of each technical replicate was integrated by patient using the same algorithm, removing protein-to-patient outliers and proteins with substantial deviation from the of the technical replicates (FDR<0.05). Final statistical comparisons were performed using Student’s-T test.

The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE22 partner repository with the dataset identifier PXD028118.

Systems Biology and Gene Enrichment Analysis

To further interrogate and contextualize the protein differences in recurrent versus non-recurrent patient tissue samples, proteins were functionally annotated with multiple databases: CORUM protein complexes database (03.09.2018),23 and DAVID24 including KEGG, REACTOME, Gene Ontology, and Panther pathways. Protein-to-category outliers (>5% FDR) were removed and remaining proteins were analyzed using The Systems Biology Triangle algorithm to identify their coordinated behavior in complexes, pathways, and/or categories.19 To better understand the molecular mechanisms underlying the coordinated proteins changes detected, we applied a gene enrichment algorithm to determine the transcription factors that drive alterations using the transcription database constructed by Lindblad-Toh et al.25 Finally, significant protein groups were visualized by retrieving protein-protein networks from the String database26 and highlighting interactions with a minimum interaction score of 0.7 in Cytoscape.27 For representation purposes, category and transcription factor information were also added to the networks.

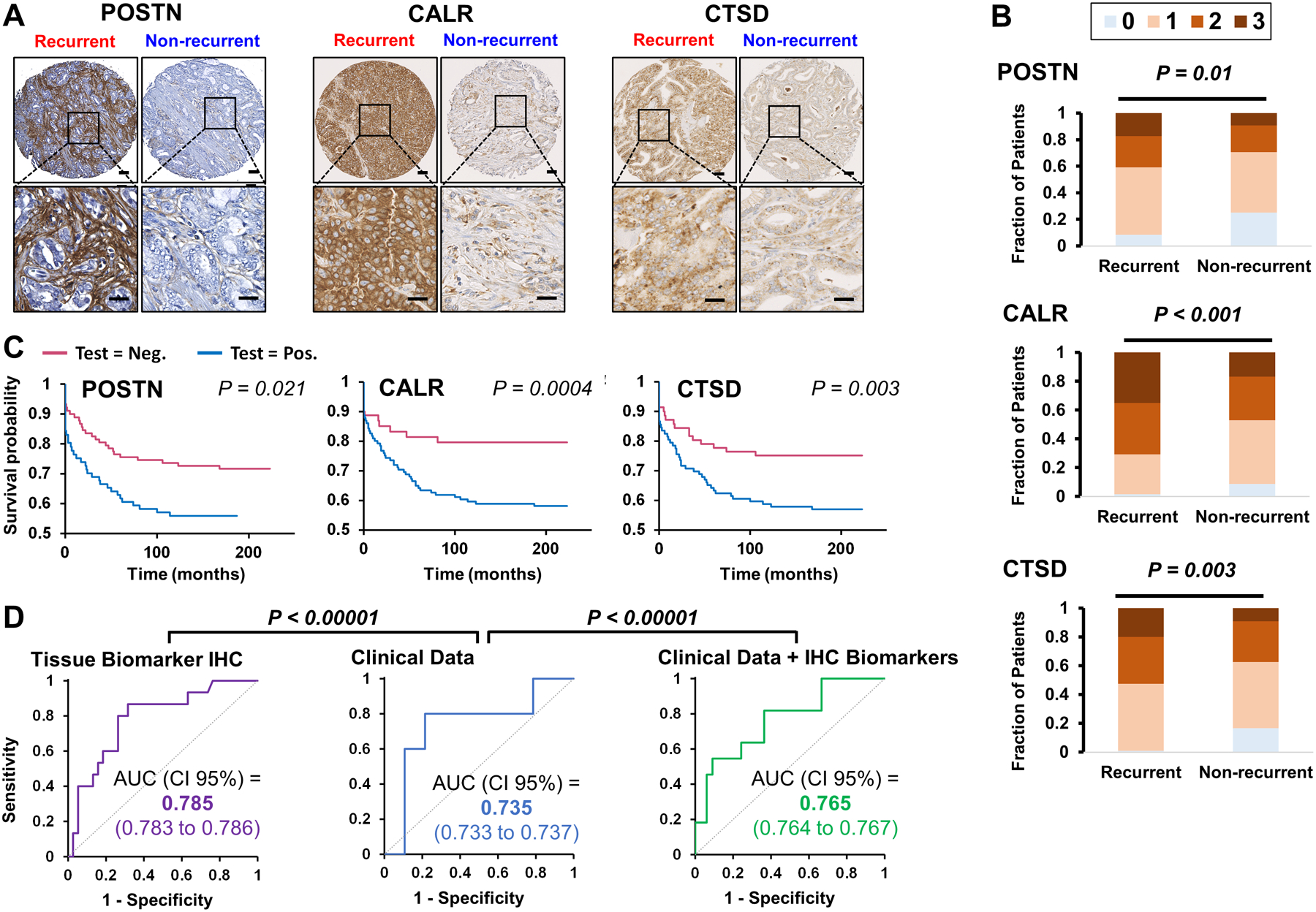

Immunohistochemical Staining of Prostate FFPE Tissue Sections and Tissue Microarrays

Initial IHC staining was performed for POSTN, CALR, CTSD, EPCAM, and RPSA on FFPE prostate tissue sections. Validation of expression and correlation with clinical outcome for POSTN, CALR, and CTSD was carried out on prostate tissue microarrays (TMAs) constructed from radical prostatectomy specimens. Tissues were obtained under an IRB approved protocol and all patients had signed informed consent for use of their tissues and association with clinical data (Protocol Number 11612). The TMAs included 4 cores of cancer and 1 core of corresponding normal from the largest cancer and included 53 cases with recurrence of cancer after surgery and 153 without evidence of recurrence with a median follow-up of 9 years. Paraffin-embedded primary prostate tumor tissues and TMAs were sliced at 4 microns. After incubation for 1 hour at 65 °C, slides were de-paraffinized with Clearify and rehydrated at 100%, 95%, and 70% ethanol. Antigen retrieval was performed in sodium citrate buffer (10 mM) pH 6.0 at 95 °C for 30 min. 2.5% goat serum (Vector Laboratories, CA) was used for blocking at room temperature for 1 hour. Staining was carried out with anti-POSTN (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-398631, 1: 100), anti-CALR (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-166837, 1: 100), anti-CTSD (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-377124, 1:100), anti-Ep-Cam (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, SC25308, 1:100), and anti-laminin R (RPSA) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-74515, 1:100) antibodies overnight at 4 °C. Slides were washed with 1xPBS and incubated with secondary anti-mouse HRP (Vector Laboratories, CA) at room temperature for 1 hour. Slides were developed with DAB reagent (DAKO). Cores were subjected to blind scoring based on intensity of staining from 0 to 3 (0 in negative, 1 is weak positive, 2 is medium positive, and 3 is strong positive, Supplementary Figure 1). Scores for all TMA samples are provided in Supplementary Table 1.

Expression of POSTN, CALR, and CTSD by IHC on tissue microarrays was tested for association with recurrence after surgery by Kaplan-Meier survival analysis and Cox proportional hazards analysis. To test the association between the survival time of patients and POSTN, CALR, and CTSD expression, Kaplan-Meier survival analysis, and Cox proportional hazards analysis were carried out in R applying the functions in the survival library28,29 using the data extracted from the TMA staining, and the time to recurrence using the maximum time of follow-up information available as the endpoint.

Six variables (levels of POSTN, CALR, and CTSD TMA staining scores, preoperative PSA levels, clinical grade group, and clinical path T) were used to construct several linear discrimination analysis (LDA) models to classify prostate cancer patients into recurrent and non-recurrent. The first model used only protein staining scores, the second model used clinical data at time of diagnosis, and the third model used clinical data and protein staining scores. After 10,000 randomizations using a proportion 80:20 of training and test dataset selections, we determined the performance of the LDA models using the median of AUC of all generated models, and Mann-Whitney U Test to determine the statistical significance of the models.

RESULTS

Proteomic Analysis of Prostate Cancer versus Non-Cancerous Tissue Samples

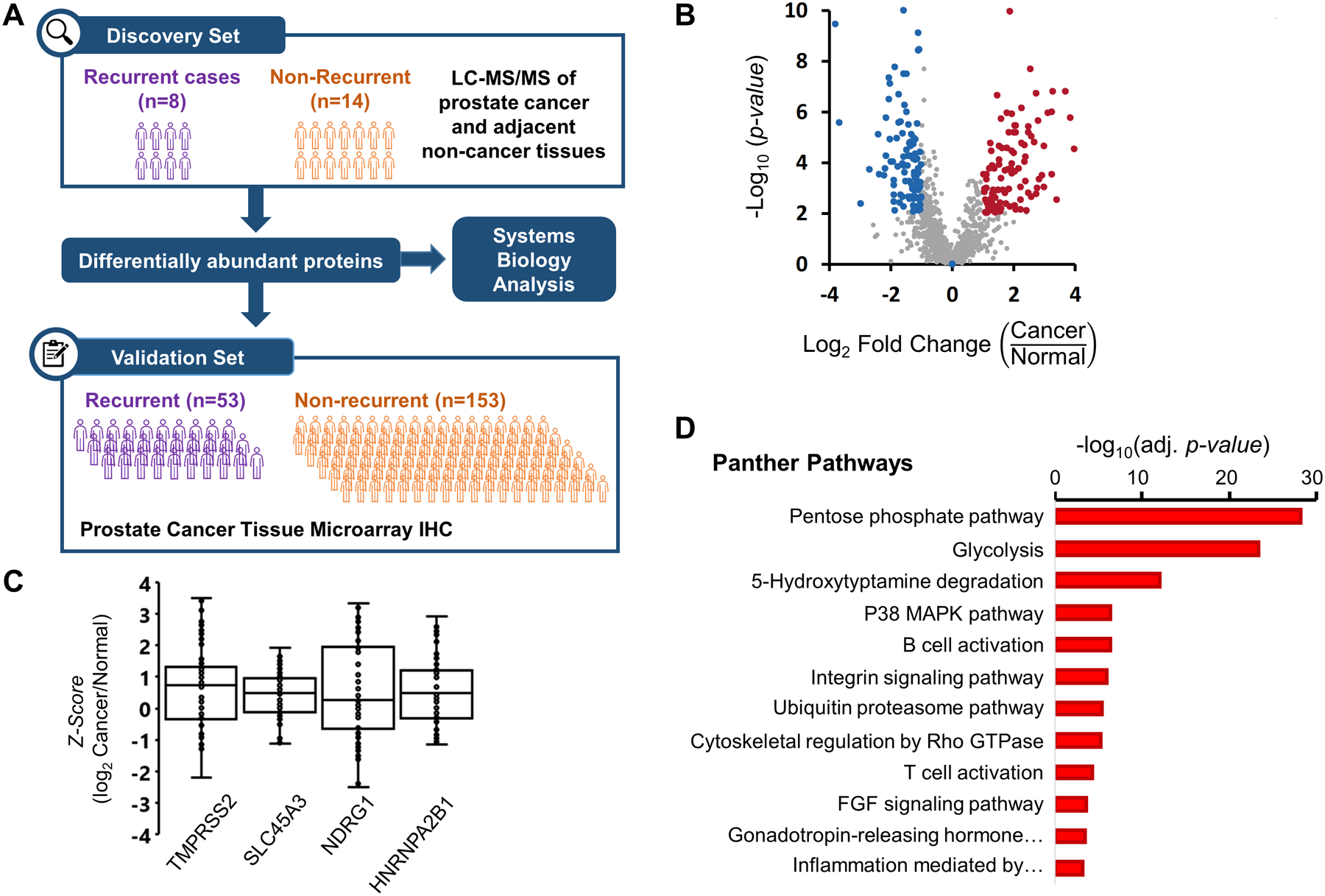

We performed LC-MS based proteomic analysis of 22 patient-matched pairs of prostate cancer and non-cancerous tissue samples from men who had undergone radical prostatectomy (Figure 1A, Table 1). Across all samples, 24,037 peptides were identified, corresponding to 3,313 proteins (after removing contaminants, proteins with single peptide spectrum match identifications, and significant outliers in replicates). The median protein sequence coverage was 16% and the median number of unique peptides for each protein was 8.8. There was high reproducibility between replicates with 96% of the proteins showing concordant differences in paired cancer versus non-cancer samples (P > 0.1 between replicates).

Figure 1.

(A) Experiment Workflow. 22 pairs of samples were subjected to label-free proteomics analysis. The resulting list of protein changes between recurrent and non-recurrent patients were validated using tissue microarrays in 206 patients and investigated using a systems biology approach. (B) Volcano plot of protein fold-changes when comparing between normal and cancer tissue. Highlighted dots representing proteins with P < 0.01 and fold-change greater than 1.5. (C) Box plot of previously published proteins related to prostate cancer. Each point represents one quantification in terms of Z-score at protein level. (D) Overrepresentation analysis according to Panther Pathways. Significant Panther Pathways (FDR < 0.05), according to Fisher’s Exact test and corrected using FDR with four or more proteins.

115 proteins had significantly different levels in prostate cancer compared to non-cancerous tissue (Figure 1B, Supplementary Table 2). Of these, four proteins previously implicated in prostate cancer, TMPRSS2, SLC45A3, NDRG1, and HNRNPA2B1 were identified (Figure 1C), as well as an additional 17 proteins dysregulated in different types of cancers according to the Cancer Gene Census.30 Using the list of proteins with significant (P < 0.01) deviations from the mean, (shaded in Figure 1B), an overrepresentation analysis (Figure 1D) showed enrichment of important pathways in cancer biology (e.g. metabolic pathways such as glycolysis, immune cell activation pathways).

Proteomic Differences Between Recurrent versus Non-Recurrent Prostate Cancer

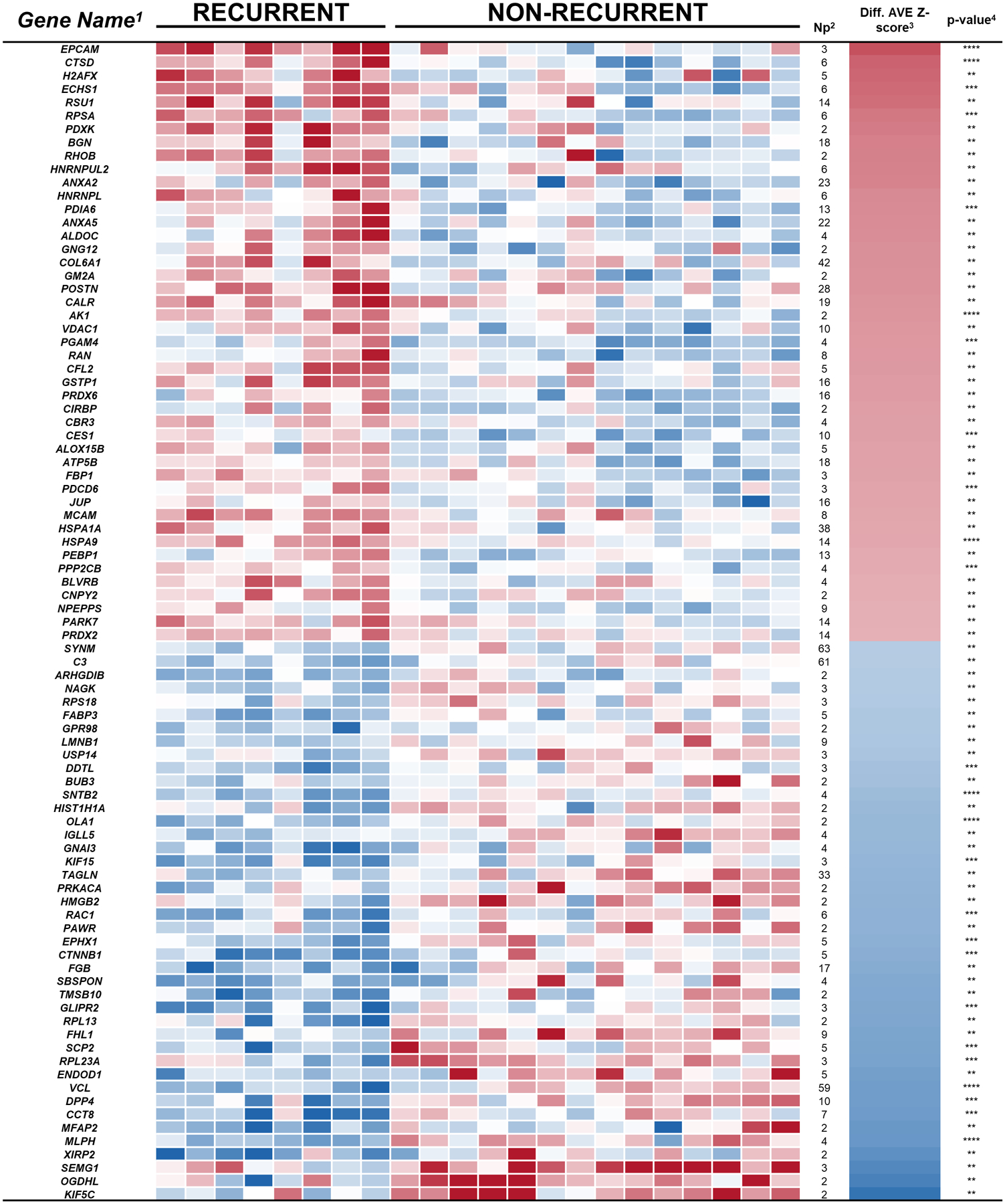

To investigate proteins associated with patient outcome in patient tissue samples, we compared the standardized log2 ratios (T/N), Z-score at the protein level of recurrent patients versus non-recurrent patients using student’s-T test. 115 proteins showed significant differences (P < 0.01) and a fold-change greater than two in patients with recurrent versus non-recurrent disease (Figure 2 and Supplementary Table 2). A subset of the significant proteins included: calcium-binding proteins, chaperones, and chromatin/chromatin-binding proteins, proteins related with translation, and cytoskeletal proteins.

Figure 2. Heat map of significant proteins differences between recurrent versus non-recurrent tissue samples (P < 0.01, Np > 1).

Relative (cancer/normal) levels of proteins with significant differences between tissue samples from recurrent versus non-recurrent prostate cancer patients are shown. The intensity of the color represents the concentration change between prostate cancer and normal (log2) from −4 (blue) to 4 (red), determined by label-free quantification. 1Official Gene Name of Protein FASTA Description, 2Number of unique identified peptides (FDR < 0.01), 3Average of the difference of standardized quantification at protein level (Zq), and 4Student’s t-test p-value for two normalized populations of equal standard deviation.

Potential YY1-Driven Protein Signatures of Recurrent Prostate Cancer

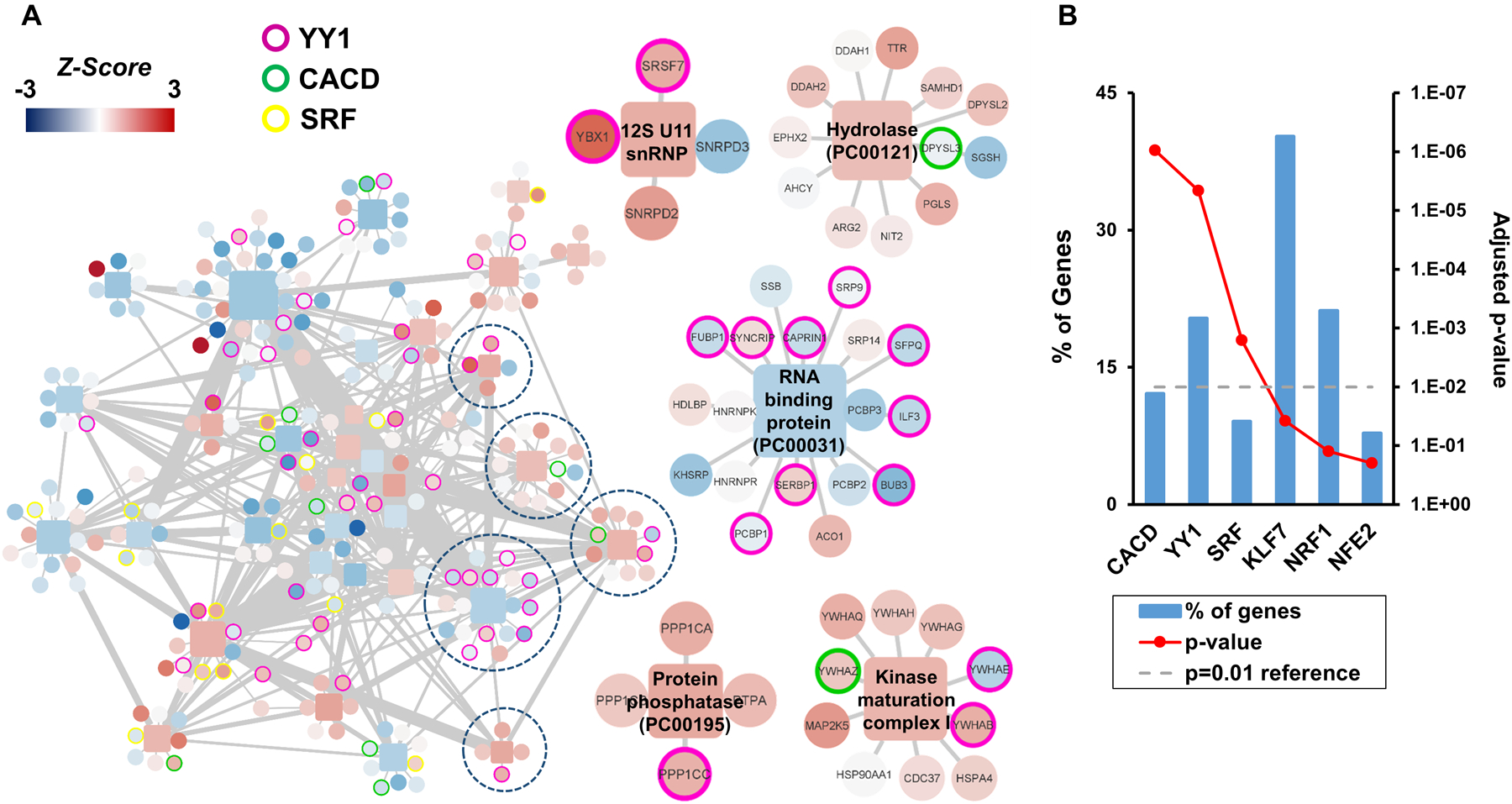

To better understand the underlying factors in prostate cancer outcome, we applied a systems biology approach19 to determine the pathways and biological processes involved in protein differences between patients with recurrent and non-recurrent disease. Quantitative protein information was organized into functional categories using PANTHER repository31 and CORUM protein complexes database23 (containing 1142 protein complexes and 622 different pathways). Of the 3,313 proteins identified in our data set, 73% of the proteins were annotated in the aforementioned databases and a low proportion (2.4%) were assigned as outliers (FDR<0.05) in all prostate cancer tissues. Unlike other approaches such as enrichment or overrepresentation analysis, the Systems Biology Triangle19 approach used all the quantitative information obtained in the proteomics experiment to detect protein coordination within protein complexes and pathways. Finally, in order to simplify the redundancy in the data architecture on the ontologies used to annotate the proteins retrieved by functional category databases, we extracted a list of proteins belonging to different categories between recurrent and non-recurrent, as a network of protein-protein interactions (Figure 3A, Supplementary Table 3) in which we included the most informative description of each pathway or complex.

Figure 3. Systems Biology Analysis.

(A) Protein complex network of significant protein complexes changes (P < 0.01 and N > 3) between recurrent and non-recurrent prostate cancer (left). Magnification of examples of protein clusters of interest (right). The color of the square nodes represents the Z-score of the categories, and circles represent proteins from −4 (blue) to 4 (red). (B) Transcription factor enrichment regulating protein complexes. The functional enrichment analysis of all quantified proteins-belonging complexes showed that CACD, YY1, and SRF transcription factors may play an important role in the recurrence of the prostate cancer.

The systems biology approach detected a network significant subtle protein differences associated with recurrent versus non-recurrent prostate cancer patients. These protein networks are usually tightly co-regulated by a common transcription factor32 that could be driving those changes. Gene enrichment analysis of the protein network related to prostate cancer recurrence, using the transcription database constructed by Lindblad-Toh et al.,25 showed enrichment of three transcription factors: CACD, YY1, and SRF (Figure 3B). CACD regulates the 12% of the genes corresponding to our list of recurrence associated proteins, and has not, to the best of our knowledge, been implicated in prostate cancer in the literature. Yin Yang 1 (YY1) regulates more than 20% of the proteins in the network. YY1 has been shown to promote the epithelial‐mesenchymal transition (EMT) in prostate cancer,33 a cellular program that confers on neoplastic cells the biological traits needed to accomplish the metastatic cascade.34 And, SRF or serum response factor, regulates nearly 9% of the genes in our network and has been related to advanced prostate cancers such as docetaxel resistant prostate cancers.35

Validation of Protein Differences using Prostate Tissue Samples and Tissue Microarrays

To explore the utility of a panel of proteins to differentiate prostate cancer patients with recurrent versus non-recurrent disease, five proteins (POSTN, CALR, CTSD) with significantly increased levels in the LC-MS proteomics analysis in recurrent vs. non-recurrent prostate cancer tissue samples (Figure 2) with commercially available antibodies suitable for IHC analysis were selected for testing in an independent set of patient tissue samples (Supplementary Figure 2). Of the five proteins tested, three (POSTN, CALR, CTSD) were selected for evaluation on a larger patient cohort using tissue microarrays (TMAs) due to their elevated levels in Gleason 4+5 samples compared to benign prostatic hyperplasia and Gleason 3+3 samples. Two proteins (EPCAM and RPSA) were not selected for further validation studies due to their high levels in Gleason 3+3 and 4+4/4+5 cases. Figure 4A shows representative images of IHC staining for POSTN, CALR, and CTSD in tissue of recurrent and non-recurrent patients. IHC levels POSTN, CALR, and CTSD all showed significant correlation with prostate cancer outcome (Figure 4B). We further applied a Cox proportional hazards model (Table 2), and a Kaplan-Meier survival analysis (Figure 4C) to test the correlation of protein expression levels with biochemical recurrence after surgery. The Kaplan-Meier survival curves show significant (P = 0.021, 0.0004, and 0.003) correlation of staining intensity on the TMAs with biochemical recurrence after surgery. Similar results were obtained when we applied the Cox proportional hazards model to the data.

Figure 4.

(A) POSTN, CALR, and CTSD is elevated in tissue of recurrent prostate cancer. Representative IHC images of recurrent and non-recurrent prostate cancer. Scale bars represent 50 microns and 25 microns. (B) POSTN, CALR, and CTSD are positively associated with prostate cancer biochemical recurrence. Strong staining for POSTN, CALR, and CTSD correlates (P = 0.01, P < 0.001, and P = 0.003, respectively), with prostate cancer recurrence (N=124). (C) Kaplan-Meier Survival Analysis. Survival analysis of POSTN, CALR, and CTSD of average TMA staining correlates (P = 0.021, 0.0004, 0.003, respectively) with prostate cancer recurrence. (D). ROC curves of LDA models. The use TMAs staining data of POSTN, CALR, and CTSD alone (purple) or in addition to clinical data (green) improves clinical data (blue) only performance of prostate cancer patient’s classification (P < 0.00001).

Table 2 |.

Cox proportional Hazards Model:

| Parameter Estimate | Hazard Ratio (HR) (95% CI for HR) |

z | Pr(>|z|) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| POSTN | 0.47 | 1.60 (1.04 – 2.48) | 2.12 | 0.034 * |

| CALR | 0.78 | 2.18 (1.28 – 3.70) | 2.88 | 0.0040 ** |

| CTSD | 0.59 | 1.81 (1.12 – 2.93) | 2.46 | 0.016 * |

Likelihood ratio test = 14.32 on 3 df, P = 0.003

Wald test = 12.14 on 3 df, P = 0.007

Score (log-rank) test = 12.82 on 3 df, P = 0.005

To further investigate the prognostic capabilities of the panel of three proteins against the current clinical standard, the performance of the proteins was benchmarked against clinical parameters (calculated from preoperative PSA level, and pathological grade group, and clinical path T). Three different LDA models were generated using tissue biomarkers IHC, using clinical data, or adding to the clinical data the IHC biomarkers tested with 10,000 randomizations to select the training and test datasets with a proportion of 80:20, respectively. The application of averaged LDA model to test datasets, generated the average ROC curves shown in Figure 4D, for tissue biomarkers IHC (purple), clinical data (blue), and clinical data plus IHC biomarkers (green) with 0.785, 0.735, and 0.765 AUC, respectively. The differences in AUCs were statistically significant (P < 0.00001) according to Mann-Whitney U test, showing a clear improvement in the models that include the IHC data of POSTN, CALR, and CTSD.

DISCUSSION

We performed a shotgun proteomics analysis on 22 pairs of prostate tumors and their corresponding adjacent normal tissues to investigate underlying molecular signatures of prostate cancer progression. Upon initial comparison of protein levels in cancerous versus non-cancerous prostate tissue samples, four significant proteins that have been previously implicated in prostate cancer were identified. Transmembrane protease, serine 2 (TMPRSS2) has been shown to promote cell growth, invasion, and metastasis of prostate cancer cells.36 Solute carrier family 45 member 44 (SLC45A3) has been reported as a validated prostate-specific protein with potential utility in prostate cancer diagnosis and treatment.37 Differentiation-related gene 1 protein (NDRG1) has been suggested as a candidate prostate cancer metastasis suppressor gene and potential useful prognostic marker.38,39 Lastly, overexpression of Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoproteins A2/B1 (HNRNPA2B1) has been shown to increase prostate cancer cells proliferation.40 Notably, the differences in expression levels between cancer and non-cancerous tissue of all these proteins were concordant with previous reports.36–40

Enrichment analysis of proteins with significantly different levels in cancerous versus non-cancerous prostate tissue further revealed a variety of pathways important in cancer biology. Key steps of the pentose phosphate shunt pathway have been identified as an important regulators of prostate cancer cell survival41 and the related glucose metabolic pathway, glycolysis, is classic hallmark of cancer42 5-hydroxytryptamine degradation, also known as serotonin metabolism is known to play important roles in a variety of cancers43, and 5-hydroxytryptamine has been reported to cause proliferation in prostate cancer cell lines.44 In prostate cancer, kinases involved in the p38 MAPK signaling pathway are critical in cell differentiation, growth, proliferation, survival, and apoptosis.45 Integrin signaling has been shown to be deregulated in several types of cancer, including prostate cancer.46 Ubiquitin proteasome proteins have been implicated in prostate cancer and the transition to more aggressive castration resistance prostate cancer.47 Cytoskeletal regulation by Rho GTPase includes a family of proteins with roles in oncogenic transformation, tumor invasion, and metastasis, with increased expression reported as prognostic of high-grade prostate carcinomas.48 Together, elevated FGF and MAPK signaling have been reported to bypass androgen receptor dependence in prostate cancer.49 The gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptor signaling pathway is targeted in prostate cancer treatment as gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists and antagonists are a standard therapeutic approach for patients.50 B cell activation, T cell activation, as well as chemokine and cytokine mediated inflammation proteins are involved in prostate cancer extracellular matrix remodeling, epithelial-mesenchymal-transition, angiogenesis, tumor invasion, premetastatic niche creation, extravasation, re-establishment of tumor cells in secondary organs, and remodeling of the metastatic tumor microenvironment.51

Our analysis allowed the identification of a range of differences in protein levels in tissue samples from patients with non-recurrent versus recurrent disease following radical prostatectomy. We identified proteins belonging to important cell biology processes such as chromatin-chromatin-binding proteins (BUB3), cytoskeletal proteins (PDCD6), chaperones (CALR), cell adhesion molecules, intercellular signal molecules (MCAM, POSTN, EPCAM, and RPSA), protein modifying enzymes (DPP4, and CTSD), and important signal transduction elements (RSU1). Another protein of interest detected was GSTP1 which has been described as important in prostate cancer diagnosis.52 Lower levels of GSTP1 were measured in non-recurrent patients compare to recurrent patients. Varriale et al. 2019, suggested that the methylation of GSPT1 could be common to prostate cancer early stages, leading to decreased protein levels; but not in advanced stages.53

BUB3 could play an important role in the control of the cell cycle and recurrence in prostate cancer54 as the checkpoint of kinetochore-microtubule attachment could be impaired due to the observed decrease of this protein, required for the establishment of the mentioned protein complex.54 PDCD6 has been reported to be upregulated in tumor tissue samples from lung, breast, colon cancer, and ovarian cancers and is involved in maintenance of cellular viability.55 Different levels between recurrent and non-recurrent samples in metabolite interconversion enzymes could potentially be explained by metabolic impairment that impacts cancer cells.56 CALR is an androgen-regulated endoplasmic reticulum protein that acts as a chaperone regulating Ca2+, with various studies showing its potential role in prostate cancer metastasis.57,58 In addition, we detected increased levels of cell adhesion molecules, and intercellular signal molecules, such as MCAM (MUC18), in our dataset. The overexpression of these proteins in osteoblastic prostate cancer has been reported to be related to an increase in tumorigenicity in vivo.59 Additional proteins of interest that were observed with significant increased levels in recurrent versus non-recurrent patients in our dataset include: POSTN a secreted protein that has been associated with prostate cancer development and progression,60 EPCAM a protein with expression levels correlated with Gleason score and bone metastasis in prostate cancer patients,61 and RPSA a protein significantly associated with invasion and metastasis in pancreatic cancer.62 Protein-binding activity modulator (PC00095) and protein modifying enzymes (PC00260) such a DPP4, a protein that has been identified as a tumor suppressor gene during progression to castration-resistant prostate cancer,63 was observed to have decreased levels in recurrent prostate cancer. CTSD is a ubiquitous lysosomal aspartic endoproteinase with expression in the stroma of prostate cancer tissue reported to contribute to tumor promotion.64 Lastly, mRNA expression levels of an important signal transduction element, RSU1, was associated with worse prognosis with reduced distant metastasis-free survival and reduced remission –free survival in breast cancer patients.65A systems biology approach using all quantitative information obtained revealed that YY1 transcription factor regulates more than 20% of the coordinated proteins changes detected in prostate tissue that differentiate between recurrent and non-recurrent patients, including CALR which was validated in the tissue microarray IHC staining experiments. The role of YY1 in cancer has been studied in depth66 and is multidimensional. YY1 has been reported to be highly expressed in multiple cancers and is essential for cancer progression.67,68 However, YY1 has also been reported to play a tumor suppressive role.69 Our results align with the idea of the crucial role of YY1 in the maintenance of cellular homeostasis through regulation of transcription, cell proliferation, DNA repair, chromatin remodeling, and apoptosis among other cellular mechanisms,70 and its dysregulation leads to aggressive stages of prostate cancer. Overall, these results suggest that transcription factors that are operational in prostate cancer may be identifiable and provide new opportunities for biological understanding of disease aggressiveness.

With additional validation studies, the inclusion of significant proteins detected in our dataset could improve the clinical prostate cancer patient classification and complement Gleason scores. The inclusion of such molecular information ultimately has the potential to better identify aggressive prostate cancer and signify patients who need to be treated versus those that could opt for active surveillance.

CONCLUSION

Thorough understanding of the protein level differences between recurrent and non-recurrent prostate cancers provide significant insights into potential new molecular indicators of disease aggressiveness and suggest that YY1 dysregulation may lead to more aggressive prostate cancer. The inclusion of POSTN, CALR, and CTSD IHC improve the clinical prostate cancer patient classification and complement clinical group grade and path T.

The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the PRIDE Archive (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/pride/archive/) via the PRIDE partner repository with the data set identifier PXD028118.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure 1. Example of IHC tissue core scoring.

Supplementary Figure 2. IHC results for POSTN, CALR, CTSD, EPCAM, and RPSA on an initial set of prostate tissue samples.

Supplementary Table 1. Tissue microarray scoring data.

Supplementary Table 2. Protein identification and quantitation data from LC-MS/MS proteomics analyses.

Supplementary Table 3. Full category and protein information for protein network shown in Figure 3A.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by CA196387 (JDB and SJP), CA226051 (SJP and JDB), R37CA240822 (TS), and R01CA244281 (TS) from the National Institutes of Health, and Canary Foundation (SJP, JDB, TS).

This manuscript is dedicated to Dr. Sanjiv Sam Gambhir, former Director of the Canary Center, and Professor and Chair of the Stanford Department of Radiology.

REFERENCES

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, Jemal A. Cancer Statistics, 2021. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(1):7–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Draisma G, Boer R, Otto SJ, et al. Lead times and overdetection due to prostate-specific antigen screening: estimates from the European Randomized Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95(12):868–878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Newcomb LF, Thompson IM Jr., Boyer HD, et al. Outcomes of Active Surveillance for Clinically Localized Prostate Cancer in the Prospective, Multi-Institutional Canary PASS Cohort. J Urol. 2016;195(2):313–320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brooks JD. Managing localized prostate cancer in the era of prostate-specific antigen screening. Cancer. 2013;119(22):3906–3909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Seisen T, Roupret M, Gomez F, et al. A comprehensive review of genomic landscape, biomarkers and treatment sequencing in castration-resistant prostate cancer. Cancer Treat Rev. 2016;48:25–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nguyen JK, Magi-Galluzzi C. Unfavorable Pathology, Tissue Biomarkers and Genomic Tests With Clinical Implications in Prostate Cancer Management. Adv Anat Pathol. 2018;25(5):293–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moschini M, Spahn M, Mattei A, Cheville J, Karnes RJ. Incorporation of tissue-based genomic biomarkers into localized prostate cancer clinics. BMC Med. 2016;14:67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lin DW, Nelson PS. Prognostic Genomic Biomarkers in Patients With Localized Prostate Cancer: Is Rising Utilization Justified by Evidence? JAMA Oncol. 2021;7(1):59–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kornberg Z, Cooperberg MR, Spratt DE, Feng FY. Genomic biomarkers in prostate cancer. Transl Androl Urol. 2018;7(3):459–471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Iczkowski KA. Genomic Pathology and Cancer Biomarkers: Prostate Cancer. Crit Rev Oncog. 2017;22(5–6):515–525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eggener SE, Rumble RB, Armstrong AJ, et al. Molecular Biomarkers in Localized Prostate Cancer: ASCO Guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(13):1474–1494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kollermann J, Schlomm T, Bang H, et al. Expression and prognostic relevance of annexin A3 in prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2008;54(6):1314–1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Escaff S, Fernandez JM, Gonzalez LO, et al. Study of matrix metalloproteinases and their inhibitors in prostate cancer. Br J Cancer. 2010;102(5):922–929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tian Y, Choi CH, Li QK, et al. Overexpression of periostin in stroma positively associated with aggressive prostate cancer. PLoS One. 2015;10(3):e0121502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lotan TL, Wei W, Morais CL, et al. PTEN Loss as Determined by Clinical-grade Immunohistochemistry Assay Is Associated with Worse Recurrence-free Survival in Prostate Cancer. Eur Urol Focus. 2016;2(2):180–188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brooks JD, Wei W, Pollack JR, et al. Loss of Expression of AZGP1 Is Associated With Worse Clinical Outcomes in a Multi-Institutional Radical Prostatectomy Cohort. Prostate. 2016;76(15):1409–1419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cox J, Mann M. Quantitative, high-resolution proteomics for data-driven systems biology. Annu Rev Biochem. 2011;80:273–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bensimon A, Heck AJ, Aebersold R. Mass spectrometry-based proteomics and network biology. Annu Rev Biochem. 2012;81:379–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garcia-Marques F, Trevisan-Herraz M, Martinez-Martinez S, et al. A Novel Systems-Biology Algorithm for the Analysis of Coordinated Protein Responses Using Quantitative Proteomics. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2016;15(5):1740–1760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gatto L, Lilley KS. MSnbase-an R/Bioconductor package for isobaric tagged mass spectrometry data visualization, processing and quantitation. Bioinformatics. 2012;28(2):288–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Navarro P, Trevisan-Herraz M, Bonzon-Kulichenko E, et al. General statistical framework for quantitative proteomics by stable isotope labeling. J Proteome Res. 2014;13(3):1234–1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Perez-Riverol Y, Csordas A, Bai J, et al. The PRIDE database and related tools and resources in 2019: improving support for quantification data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47(D1):D442–D450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Giurgiu M, Reinhard J, Brauner B, et al. CORUM: the comprehensive resource of mammalian protein complexes-2019. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47(D1):D559–D563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huang da W, Sherman BT, Zheng X, et al. Extracting biological meaning from large gene lists with DAVID. Curr Protoc Bioinformatics. 2009;Chapter 13:Unit 13 11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lindblad-Toh K, Garber M, Zuk O, et al. A high-resolution map of human evolutionary constraint using 29 mammals. Nature. 2011;478(7370):476–482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Szklarczyk D, Gable AL, Lyon D, et al. STRING v11: protein-protein association networks with increased coverage, supporting functional discovery in genome-wide experimental datasets. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47(D1):D607–D613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Doncheva NT, Morris JH, Gorodkin J, Jensen LJ. Cytoscape StringApp: Network Analysis and Visualization of Proteomics Data. J Proteome Res. 2019;18(2):623–632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Therneau T. A Package for Survival Analysis in R. https://cran.r-project.org/package=survival. 2021. R package version 3.2-12.

- 29.Therneau TM, Grambsch PM. Modeling survival data : extending the Cox model. New York: Springer; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sondka Z, Bamford S, Cole CG, Ward SA, Dunham I, Forbes SA. The COSMIC Cancer Gene Census: describing genetic dysfunction across all human cancers. Nat Rev Cancer. 2018;18(11):696–705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mi H, Muruganujan A, Ebert D, Huang X, Thomas PD. PANTHER version 14: more genomes, a new PANTHER GO-slim and improvements in enrichment analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47(D1):D419–D426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hansson J, Rafiee MR, Reiland S, et al. Highly coordinated proteome dynamics during reprogramming of somatic cells to pluripotency. Cell Rep. 2012;2(6):1579–1592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang T, An Z, Zhang C, et al. hnRNPM, a potential mediator of YY1 in promoting the epithelial-mesenchymal transition of prostate cancer cells. Prostate. 2019;79(11):1199–1210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kashyap V, Bonavida B. Role of YY1 in the pathogenesis of prostate cancer and correlation with bioinformatic data sets of gene expression. Genes Cancer. 2014;5(3–4):71–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lundon DJ, Boland A, Prencipe M, et al. The prognostic utility of the transcription factor SRF in docetaxel-resistant prostate cancer: in-vitro discovery and in-vivo validation. BMC Cancer. 2017;17(1):163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ko CJ, Huang CC, Lin HY, et al. Androgen-Induced TMPRSS2 Activates Matriptase and Promotes Extracellular Matrix Degradation, Prostate Cancer Cell Invasion, Tumor Growth, and Metastasis. Cancer Res. 2015;75(14):2949–2960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xu J, Kalos M, Stolk JA, et al. Identification and characterization of prostein, a novel prostate-specific protein. Cancer Res. 2001;61(4):1563–1568. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bandyopadhyay S, Pai SK, Gross SC, et al. The Drg-1 gene suppresses tumor metastasis in prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2003;63(8):1731–1736. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sharma A, Mendonca J, Ying J, et al. The prostate metastasis suppressor gene NDRG1 differentially regulates cell motility and invasion. Mol Oncol. 2017;11(6):655–669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stockley J, Villasevil ME, Nixon C, Ahmad I, Leung HY, Rajan P. The RNA-binding protein hnRNPA2 regulates beta-catenin protein expression and is overexpressed in prostate cancer. RNA Biol. 2014;11(6):755–765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ros S, Santos CR, Moco S, et al. Functional metabolic screen identifies 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose-2,6-biphosphatase 4 as an important regulator of prostate cancer cell survival. Cancer Discov. 2012;2(4):328–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144(5):646–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sarrouilhe D, Mesnil M. Serotonin and human cancer: A critical view. Biochimie. 2019;161:46–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Siddiqui EJ, Shabbir M, Mikhailidis DP, Thompson CS, Mumtaz FH. The role of serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine1A and 1B) receptors in prostate cancer cell proliferation. J Urol. 2006;176(4 Pt 1):1648–1653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rodriguez-Berriguete G, Fraile B, Martinez-Onsurbe P, Olmedilla G, Paniagua R, Royuela M. MAP Kinases and Prostate Cancer. J Signal Transduct. 2012;2012:169170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Goel HL, Alam N, Johnson IN, Languino LR. Integrin signaling aberrations in prostate cancer. Am J Transl Res. 2009;1(3):211–220. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Voutsadakis IA, Papandreou CN. The ubiquitin-proteasome system in prostate cancer and its transition to castration resistance. Urol Oncol. 2012;30(6):752–761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Engers R, Ziegler S, Mueller M, Walter A, Willers R, Gabbert HE. Prognostic relevance of increased Rac GTPase expression in prostate carcinomas. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2007;14(2):245–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bluemn EG, Coleman IM, Lucas JM, et al. Androgen Receptor Pathway-Independent Prostate Cancer Is Sustained through FGF Signaling. Cancer Cell. 2017;32(4):474–489 e476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fontana F, Marzagalli M, Montagnani Marelli M, Raimondi M, Moretti RM, Limonta P. Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone Receptors in Prostate Cancer: Molecular Aspects and Biological Functions. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(24). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Adekoya TO, Richardson RM. Cytokines and Chemokines as Mediators of Prostate Cancer Metastasis. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(12). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gonzalgo ML, Pavlovich CP, Lee SM, Nelson WG. Prostate cancer detection by GSTP1 methylation analysis of postbiopsy urine specimens. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9(7):2673–2677. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Varriale E, Crocetto F, Cianciulli MR, Palermo E, Vitale A, Benincasa G. Assessment of glutathione-S-Transferase (GSTP1) Methylation Status is a Reliable Molecular Biomarker for Early Diagnosis of Prostatic Intraepithelial Neoplasia. World Cancer Res J. 2019;6:e1384. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Logarinho E, Resende T, Torres C, Bousbaa H. The human spindle assembly checkpoint protein Bub3 is required for the establishment of efficient kinetochore-microtubule attachments. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19(4):1798–1813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hashemi M, Bahari G, Markowski J, Malecki A, Los MJ, Ghavami S. Association of PDCD6 polymorphisms with the risk of cancer: Evidence from a meta-analysis. Oncotarget. 2018;9(37):24857–24868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Seyfried TN, Flores RE, Poff AM, D’Agostino DP. Cancer as a metabolic disease: implications for novel therapeutics. Carcinogenesis. 2014;35(3):515–527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Alur M, Nguyen MM, Eggener SE, et al. Suppressive roles of calreticulin in prostate cancer growth and metastasis. Am J Pathol. 2009;175(2):882–890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wu M, Bai X, Xu G, et al. Proteome analysis of human androgen-independent prostate cancer cell lines: variable metastatic potentials correlated with vimentin expression. Proteomics. 2007;7(12):1973–1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zoni E, Astrologo L, Ng CKY, et al. Therapeutic Targeting of CD146/MCAM Reduces Bone Metastasis in Prostate Cancer. Mol Cancer Res. 2019;17(5):1049–1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cattrini C, Rubagotti A, Nuzzo PV, et al. Overexpression of Periostin in Tumor Biopsy Samples Is Associated With Prostate Cancer Phenotype and Clinical Outcome. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2018;16(6):e1257–e1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hu Y, Wu Q, Gao J, Zhang Y, Wang Y. A meta-analysis and The Cancer Genome Atlas data of prostate cancer risk and prognosis using epithelial cell adhesion molecule (EpCAM) expression. BMC Urol. 2019;19(1):67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wu Y, Tan X, Liu P, et al. ITGA6 and RPSA synergistically promote pancreatic cancer invasion and metastasis via PI3K and MAPK signaling pathways. Exp Cell Res. 2019;379(1):30–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Russo JW, Gao C, Bhasin SS, et al. Downregulation of Dipeptidyl Peptidase 4 Accelerates Progression to Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. Cancer Res. 2018;78(22):6354–6362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pruitt FL, He Y, Franco OE, Jiang M, Cates JM, Hayward SW. Cathepsin D acts as an essential mediator to promote malignancy of benign prostatic epithelium. Prostate. 2013;73(5):476–488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gkretsi V, Louca M, Stylianou A, Minadakis G, Spyrou GM, Stylianopoulos T. Inhibition of Breast Cancer Cell Invasion by Ras Suppressor-1 (RSU-1) Silencing Is Reversed by Growth Differentiation Factor-15 (GDF-15). Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sarvagalla S, Kolapalli SP, Vallabhapurapu S. The Two Sides of YY1 in Cancer: A Friend and a Foe. Front Oncol. 2019;9:1230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Atchison M, Basu A, Zaprazna K, Papasani M. Mechanisms of Yin Yang 1 in oncogenesis: the importance of indirect effects. Crit Rev Oncog. 2011;16(3–4):143–161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhang Q, Stovall DB, Inoue K, Sui G. The oncogenic role of Yin Yang 1. Crit Rev Oncog. 2011;16(3–4):163–197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zhang JJ, Zhu Y, Xie KL, et al. Yin Yang-1 suppresses invasion and metastasis of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma by downregulating MMP10 in a MUC4/ErbB2/p38/MEF2C-dependent mechanism. Mol Cancer. 2014;13:130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gordon S, Akopyan G, Garban H, Bonavida B. Transcription factor YY1: structure, function, and therapeutic implications in cancer biology. Oncogene. 2006;25(8):1125–1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1. Example of IHC tissue core scoring.

Supplementary Figure 2. IHC results for POSTN, CALR, CTSD, EPCAM, and RPSA on an initial set of prostate tissue samples.

Supplementary Table 1. Tissue microarray scoring data.

Supplementary Table 2. Protein identification and quantitation data from LC-MS/MS proteomics analyses.

Supplementary Table 3. Full category and protein information for protein network shown in Figure 3A.