Abstract

Objective:

To compare the reproducibility of landmark identification on three-dimensional (3D) cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) images between procedures based on traditional cephalometric definitions (procedure 1) and those tentatively proposed for 3D images (procedure 2).

Materials and Methods:

A phantom with embedded dried human skull was scanned using CBCT. The acquired volume data were transferred to a personal computer, and 3D images were reconstructed. Eighteen dentists plotted nine landmarks related to the jaws and teeth four times: menton (Me), pogonion (Po), upper-1 (U1), lower-1 (L1), left upper-6 (U6), left lower-6 (L6), gonion (Go), condyle (Cd), and coronoid process (Cp). The plotting reliabilities of the two procedures were compared by calculating standard deviations (SDs) in three components (x, y, and z) of coordinates and volumes of 95% confidence ellipsoid.

Results:

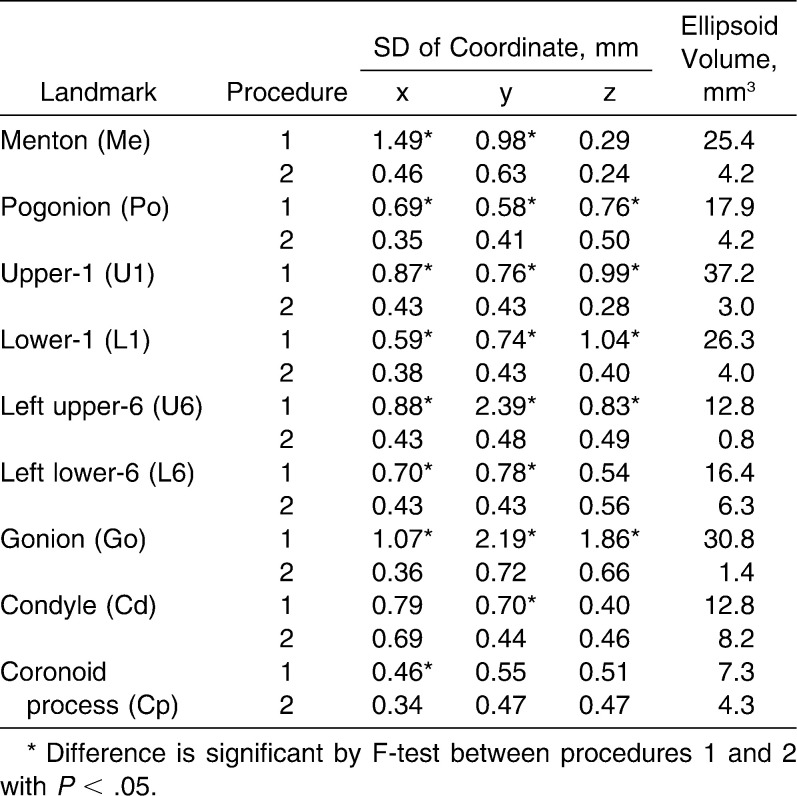

All 27 SDs for procedure 2 were less than 1 mm, and only five of them exceeded 0.5 mm. The variations were significantly different between the two procedures, and the SDs of procedure 2 were smaller than those of procedure 1 in 21 components of coordinates. The ellipsoid volumes were also smaller for procedure 2 than procedure 1, although a significant difference was not found.

Conclusions:

Definitions determined strictly on each three sectional images, such as for procedure 2, were required for sufficient reliability in identifying the landmark related to the jaws and teeth.

Keywords: Reproducibility of results; Cone-beam computed tomography; Anatomy, cross-sectional; Imaging; Three-dimensional

INTRODUCTION

Computed tomography (CT) and cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) allow us to handle images three-dimensionally, and are now widely used for planning and evaluating various dental treatments,1–4 such as orthognathic surgery5–8 and orthodontic treatment.9–12 Some procedures have been proposed for three-dimensional (3D) measurements and are also applied to cephalometric analysis, which has the potential to replace traditional two-dimensional (2D) cephalometric evaluation.11,12 Even in 3D cephalometrics, it would be reasonable to use traditional 2D cephalometric landmarks because we are sufficiently familiar with them and can compare 3D analytic results with large amounts of 2D data that have been accumulated.

The images obtained by CT or CBCT are now generally manipulated as volume data, and we can simultaneously observe three sectional planes—sagittal, coronal, and axial—with the use of ordinarily available 3D software. It is, however, problematic to apply the 2D definitions themselves to 3D analysis because we cannot clearly identify the landmarks on each sectional plane with a 2D definition. Consequently, the reproducibility of landmark identification becomes poor. Although the definitions of landmarks should be modified for 3D analysis, there have been no generally accepted definitions. This is probably attributed to a lack of well-established methods to evaluate the plotting reproducibility of landmarks. There are few reports regarding the reliability of landmarks,13–16 whereas the reproducibility of length or angle measurements has been verified as sufficient for clinical evaluation.10,17–20 In this regard, we modified and proposed the 95% confidence ellipse method for 3D images obtained by CT or CBCT.21,22

The purpose of the present study was to compare the reproducibility of landmark identification on 3D CBCT images between two procedures through the use of the 95% confidence ellipse method. One procedure was based on traditional 2D cephalometric definitions, and the other was tentatively proposed for the landmarks related to the jaws and teeth on 3D images.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Acquisition of CBCT Data and Image Manipulations

An acrylic phantom with embedded human dried skull (Kyoto Kagaku, Kyoto, Japan) was scanned with a flat panel-based CBCT device Alphard Vega (Asahi Roentgen Ind, Kyoto, Japan) under exposure conditions of 80 kVp and 5 mA. The phantom was positioned on a special plate with its occlusal plane horizontally. The scanned area was shaped in a column (20 cm in diameter and 18 cm in height), and the voxel size was 0.39 × 0.39 × 0.39 mm. This study was approved by the Aichi-Gakuin University Institutional Ethics Committee.

Acquired data were stored in DICOM format and transferred to a personal computer to create 3D images employing the volume rendering technique using image analysis software (VG Studio MAX 1.1; Nihon Visual Science, Tokyo, Japan). On the created 3D image, the coordinate system was automatically determined with the origin set at a corner of a cubic matrix (3D volumetric dataset), and it was defined as the initial coordinate (Xi, Yi, and Zi axes). The X axis roughly corresponded to the left-right direction in the phantom's head. The Y and Z axes were set parallel to the anterior-posterior and superior-inferior directions, respectively. The positive directions were the left, posterior, and superior directions for the Xi, Yi, and Zi axes, respectively. The coordinates (x, y, and z) could be determined for each voxel and converted to the actual size in millimeters. On this software, we could simultaneously observe three sectional images along the initially determined coordinate axes and freely chose the optimal slice for plotting certain landmarks (Figure 1). The plotted landmarks could also be marked in two other images, and were revised adequately with reference to these marks.

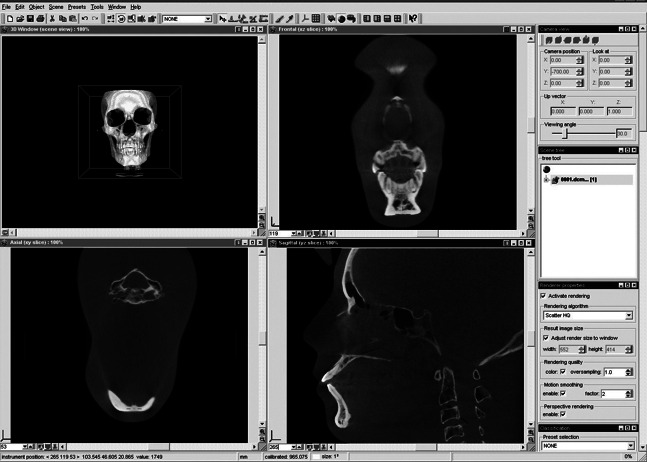

Figure 1.

With the software used, a suitable slice can be freely selected for landmark plotting on sectional images in each of three directions (Xi, Yi, and Zi directions). When a landmark is identified on a slice image, it can be marked automatically on two other slice images.

Methods of Landmark Identification

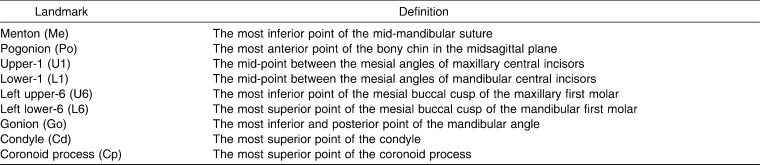

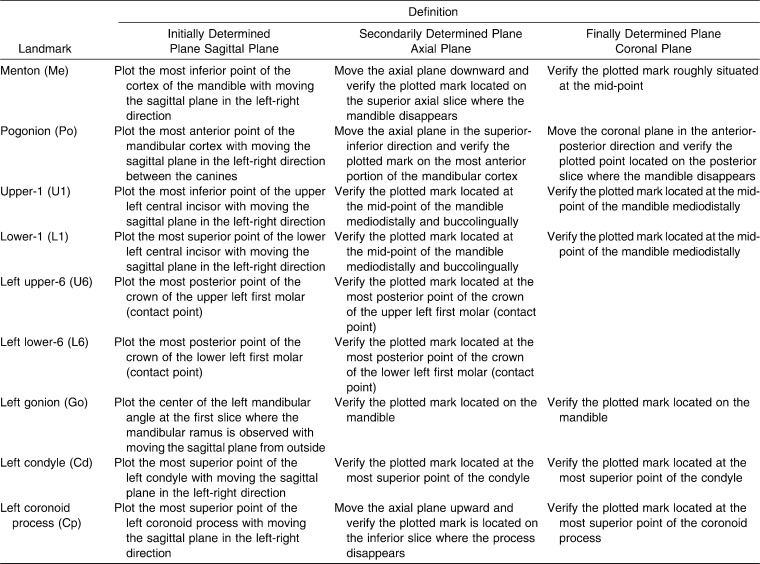

Two procedures were compared for identifying nine landmarks related to the jaw and teeth: menton (Me), pogonion (Po), upper-1 (U1), lower-1 (L1), left upper-6 (U6), left lower-6 (L6), gonion (Go), condyle (Cd), and coronoid process (Cp). One procedure was based on the traditional definitions used in cephalometric analysis (procedure 1, Table 1). Raters could freely determine the landmarks through the use of PC software. The other was an alternative procedure that was tentatively determined by taking 3D volume data into account, and it offered more precise definitions of each sectional image (procedure 2). Based on procedure 2, the landmarks were determined strictly according to the definitions, including the identification order (Table 2).

Table 1.

Landmark Identification Method Based on Cephalometric Definition (Procedure 1)

Table 2.

Tentative Method for Landmark Identification (Procedure 2)

Evaluation of Reproducibility

Eighteen dentists who had more than 3 years of experience in cephalometric analysis identified nine landmarks twice based on the above two procedures. A dentist identified each landmark four times with more than a week interval between identifications. To avoid experience-based bias, the identifications were performed in random order. Nine dentists initially determined the landmarks' coordinates based on procedure 1 twice, and thereafter they identified them based on procedure 2. The remaining nine dentists determined initially performed procedure 2 twice, and then procedure 1. A total of 36 coordinates were determined for a landmark based on each procedure.

Standard deviations (SDs) of coordinates were calculated in x, y, and z components. Twenty-seven components were evaluated for each procedure. The difference in variation was examined between the two procedures using the F-test with a significance of less than .05. In addition, scatter plots and 95% confidence ellipses were created three-dimensionally with statistical software (JMP; SAS Institute Japan, Tokyo, Japan), and the volumes of ellipsoids were calculated.

RESULTS

The variability of landmark identification was expressed as the SD of coordinates for three components (x, y, and z) (Table 3). For procedure 1, SDs of six components (Me's x; L1's z component; U6's y component; and Go's x, y, and z components) were more than 1 mm, while only three components were less than 0.5 mm. All 27 SDs for procedure 2 were less than 1 mm and only five of them exceeded 0.5 mm. The variations were significantly different in 21 components between the two procedures (F-test, P < .05). In these 21 components, the SDs of procedure 2 were smaller than those of procedure 1. Regarding the difference between the observers who initially used procedure 1 and those who first used procedure 2, variations were different in seven components among all 27 coordinate components in nine landmarks (F-test, P < .05). Six of them were observed in procedure 1.

Table 3.

Standard Deviations of Coordinates (x, y, and z Components) and Ellipsoid Volumes in Nine Anatomical Landmarks

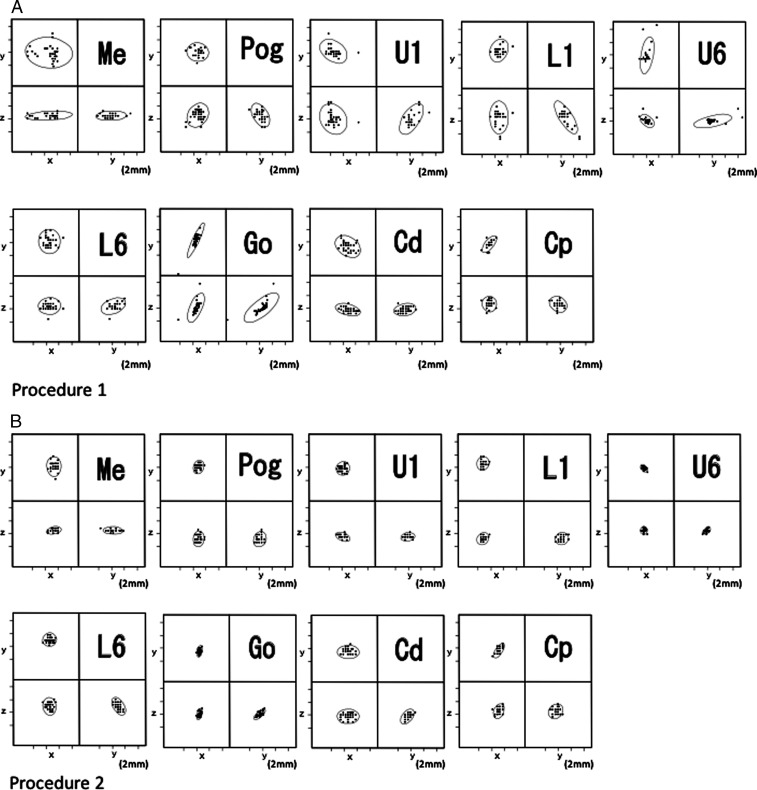

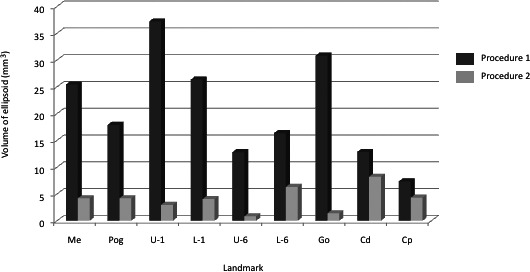

The scatter plots and 95% confidence ellipses are shown in three dimensions (Figure 2). The ellipses for procedure 2 were smaller than those for procedure 1. The volumes of ellipsoids were also smaller for procedure 2 than for procedure 1 (Figure 3). However, these could not be statistically verified because only a phantom was used.

Figure 2.

The 95% confidence ellipses for procedures 1 (A) and 2 (B). The ellipses are smaller in procedure 2 than in procedure 1.

Figure 3.

The volumes of ellipsoids.

DISCUSSION

With the widespread use of CBCT in jaw and maxillofacial regions, 3D measurements are frequently applied to orthognathic surgery and orthodontic treatment. Not only the accuracy but also the reliability or reproducibility of 3D measurements have been verified to be sufficient for clinical use.10,13–21 In many studies,10,17–20 however, the reliability has been tested for measurements of the length or angle created by two or three landmarks, and therefore we cannot exactly identify which landmark is unstable when reliability of the length or angular measurement is insufficient. To solve this problem, the reliability should be evaluated for identifying landmarks themselves.14–16,20

In this regard, a few studies have been reported. With conventional CT data, Kragskov et al.14 reported on the reproducibility of landmarks as the distance between two plots which are made twice by one or two examiners. Park et al.15 assessed intraexaminer reproducibility in a subject. Nineteen landmarks were identified five times in one session by an observer. The observer identified the same landmarks five times in a second session 2 weeks after the first session. The mean and SD of coordinates was compared between the two sessions for three components (x, y, and z components). The SD of procedure 2 in the present study was similar to their results. As the reliability for intraexaminer is generally higher than that for interexaminer, the results of the present study including the interrater reliability would be sufficient. Recently, de Oliveria et al.16 calculated interclass correlation coefficients to test intraobserver and interobserver reliability. They concluded that the reliability was sufficient and emphasized that the differences in mean values were less than 1 mm in the x, y, and z components of coordinates for 80% of 30 landmarks. Taking their results into account, the reliability of procedure 2 might also be sufficient because 22 of 27 coordinate components showed a SD of less than 0.5 mm.

In our previous study with helical CT, we also proposed a method to evaluate the reproducibility of a landmark itself, modifying the 95% confidence ellipse method for 3D images.21 The landmarks related to the jaw and teeth, which were plotted on the axial CT slice, showed relatively wide variations, probably because of the application of 2D cephalometric definitions to 3D images. However, this method allows us to visually interpret the variability of landmark identification. In the present study, therefore, the methods for calculating SDs and confidence ellipses were adopted.

The reliability in procedure 2 was apparently higher than that in procedure 1. We therefore emphasize that the landmarks should be plotted based on strict definitions which are determined based on three separate slice data. Although all landmarks were initially determined on the sagittal plane in the present study, it may be better to initially plot them on other planes for higher reproducibility. The definitions presented here are only an example, and they should be revised continuously, especially the landmarks showing insufficient reproducibility.

A major drawback of the present study was the use of only a phantom. The results, therefore, may be specific to this phantom. However, the methodology which enables us to assess the reproducibility of landmark identification is effective for future studies. Moreover, interobserver and intraobserver reliability is important for this kind of study. Taken together, we shall conduct a study using CBCT data from multiple actual patients.

Advances in computer techniques enable us to handle 3D images and simultaneously visualize three sectional images at right angles to each other using volume data. There may be many ways to identify anatomical landmarks, and a unique and effective procedure to automatically determine the landmarks shall be proposed. However, for the practical use of 2D cephalometry results which have already been accumulated, the procedure presented here is significantly effective because it uses the same landmarks (even with different definitions) as traditional cephalography and does not require special apparatus or particularly expensive software.

CONCLUSION

For sufficient reproducibility in identifying the landmarks related to the jaws and teeth on 3D CBCT images, an alternative is to use the definitions determined strictly on each three sectional image. To establish more reproducible identification, the definitions should be revised continuously through the use of the method presented here.

Acknowledgments

We thank all dentists who plotted landmarks for their cooperation. This study was partially supported by Grant-in-Aids for Scientific Research (20592212) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kawamata A, Ariji Y, Langlais R. P. Three-dimensional computed tomography imaging in dentistry. Dent Clin North Am. 2000;44:395–410. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nakata K, Naitoh M, Izumi M, Ariji E, Nakamura H. Evaluation of correspondence of dental computed tomography imaging to anatomic observation of external root resorption. J Endod. 2009;35:1594–1597. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2009.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hatano Y, Kurita K, Kuroiwa Y, Yuasa H, Ariji E. Clinical evaluation of coronectomy (intentional partial odontectomy) for mandibular third molars using dental computed tomography: a case-control study. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009;67:1806–1814. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2009.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Naitoh M, Nabeshima H, Hayashi H, Nakayama T, Kurita K, Ariji E. Postoperative assessment of incisor dental implants using cone-beam computed tomography. J Oral Implantol. 2010;36:377–384. doi: 10.1563/AAID-JOI-D-09-00080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ariji Y, Kawamata A, Yoshida K, et al. Three-dimensional morphology of the masseter muscle in patients with mandibular prognathism. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2000;29:113–118. doi: 10.1038/sj/dmfr/4600515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Katsumata A, Fujishita M, Maeda M, Ariji Y, Ariji E, Langlais R. P. 3D-CT evaluation of facial asymmetry. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2005;99:212–220. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2004.06.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maeda M, Katsumata A, Ariji Y, et al. 3D-CT evaluation of facial asymmetry in patients with maxillofacial deformities. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2006;102:382–390. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2005.10.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maeda M, Katsumata A, Ariji Y, et al. Changes in skeletal asymmetry after sagittal split ramus osteotomy for patients with mandibular prognathism: three-dimensional computed tomographic assessment. Oral Radiol. 2007;23:10–15. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maki K, Inoue N, Takanishi A, Miller A. J. Computer-assisted simulations in orthodontic diagnosis and the application of a new cone beam X-ray computed tomography. Orthod Craniofac Res. 2003;6(suppl 1):95–101. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0544.2003.241.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Periago D. R, Scarfe W. C, Moshiri M, Scheetz J. P, Silveria A. M, Farman A. G. Linear accuracy and reliability of cone beam CT derived 3-dimensional images constructed using an orthodontic volumetric rendering program. Angle Orthod. 2008;78:387–395. doi: 10.2319/122106-52.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gribel B. F, Gribel M. N, Frazäo D. C, McNamara J. A, Jr, Manzi F. R. Accuracy and reliability of craniometric measurements on lateral cephalometry and 3D measurements on CBCT scans. Angle Orthod. 2011;81:28–37. doi: 10.2319/032210-166.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yitschaky O, Redlich M, Abed Y, Faerman M, Casap N, Hiller N. Comparison of common hard tissue cephalometric measurements between computed tomography 3D reconstruction and conventional 2D cephalometric images. Angle Orthod. 2011;81:13–18. doi: 10.2319/031710-157.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lou L, Lagravere M. O, Compton S, Major P. W, Flores-Mir C. Accuracy of measurements and reliability of landmark identification with computed tomography (CT) techniques in the maxillofacial area: a systematic review. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2007;104:402–411. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2006.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kragskov J, Bosch C, Gyldensted C, Sindet-Pedersen S. Comparison of the reliability of craniofacial anatomic landmarks based on cephalometric radiographs and three-dimensional CT scans. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 1997;34:111–116. doi: 10.1597/1545-1569_1997_034_0111_cotroc_2.3.co_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Park S. H, Yu H. S, Kim K. D. A proposal for a new analysis of craniofacial morphology by 3-dimensional computed tomography. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2006;129:600.e23–600.e34. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2005.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Oliveria A. E, Cevidanes L. H, Phillips C. Observer reliability of three-dimensional cephalometric landmark identification on cone-beam computerized tomography. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2009;107:256–265. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2008.05.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Waitzman A. A, Posnick J. C, Armstrong D. C, Pron G. E. Craniofacial skeletal measurements based on computed tomography: Part I. Accuracy and reproducibility. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 1992;29:112–117. doi: 10.1597/1545-1569_1992_029_0112_csmboc_2.3.co_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cavalcanti M. G. P, Rocha S. S, Vannier M. W. Craniofacial measurements based on 3D-CT volume rendering: implications for clinical applications. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2004;33:170–176. doi: 10.1259/dmfr/13603271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lascala C. A, Panella J, Marques M. M. Analysis of the accuracy of linear measurements obtained by cone beam computed tomography (CBCT-NewTOM) Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2004;33:291–294. doi: 10.1259/dmfr/25500850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lopes P. M. L, Moreira C. R, Perrella A, Antunes J. L, Cavalcanti M. G. P. 3-D volume rendering maxillofacial analysis of angular measurements by multislice CT. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2008;105:224–230. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2007.08.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Muramatsu A, Nawa H, Kimura M. Reproducibility of maxillofacial anatomic landmarks on 3-dimensional computed tomographic images determined with the 95% confidence ellipse method. Angle Orthod. 2008;78:396–402. doi: 10.2319/040207-166.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kimura M, Tokumori K, Nawa H. Reliability of a coordinate system based on anatomical landmarks of the maxillofacial skeleton: an evaluation method for 3-dimensional images obtained by cone-beam computed tomography. Oral Radiol. 2009;25:37–42. [Google Scholar]