Abstract

Objective:

To test the null hypothesis that stainless steel and ceramic brackets show no differences in biofilm adhesion.

Materials and Methods:

Twenty adolescents (6 boys, 14 girls) who had received fixed orthodontic therapy for 18.9 ± 3.2 months were divided into a metal and a ceramic bracket group. Thirty brackets per group were taken from central incisors, canines, and second premolars and quantitatively analyzed for biofilm coverage with the Rutherford backscattering detection method. Five micrographs were obtained per bracket with views from the buccal, mesial, distal, gingival, and occlusal aspects, resulting in a total of 300 images. Biofilm formation between groups was compared using the Mann-Whitney U-test (α = .05).

Results:

Total biofilm formation was 12.5% ± 5.7% (3.3 ± 1.6 mm2) of the surface on metal and 5.6% ± 2.4% (1.5 ± 0.6 mm2) on ceramic brackets. Differences between groups were statistically significant (P < .05). A pairwise comparison of biofilm formation revealed significantly lower biofilm formation on ceramic brackets with respect to intraoral location (central incisor, canine, second premolar) and bracket surface (buccal, mesial, distal).

Conclusions:

The hypothesis was rejected. The results indicate that ceramic brackets exhibit less long-term biofilm accumulation than metal brackets.

Keywords: Orthodontic, Biofilms, Orthodontic brackets, Ceramic, Metal

INTRODUCTION

Thanks to the technical progress of the last decades, today three-dimensional tooth movements can be provided by fixed orthodontic appliances. In most cases, fixed orthodontic treatment consists of applying brackets made of stainless steel.1 Because of the increase in even young adolescents' needs for more esthetic treatment options, the usage of tooth-colored brackets made of ceramics is on the rise.2

However, orthodontic therapy using fixed appliances induces clinical side effects due to the presence of more plaque-retentive niches and impaired mechanical plaque removal.3 Clinical studies have shown an increase in biofilm formation combined with an ecological change of the microbial profile after bracket insertion.4–6 The shift in amount, composition, metabolic activity, and pathogenicity of the oral microflora can lead to generalized gingival inflammation and incipient carious lesions.7–10 The periodontal side effects, apparent in parameters such as pocket probing depths and bleeding on probing,11 are considered to be generally transient.12 In contrast, signs of enamel decalcification, such as white spot lesions at the bracket peripheries, are frequently permanent.13

There is evidence that the bracket material affects the adhesion of bacterial species and plaque accumulation. In clinical studies, surface roughness, surface free energy, and other physicochemical properties of the biomaterials were shown to influence plaque-retaining capacity.14–16

In the literature, there is debate about whether any one particular material has favorable characteristics with respect to biofilm adhesion.15,17,18 Therefore, the aim of this study was to analyze the long-term impact of the bracket material (stainless steel and ceramic) on the extent of biofilm coverage under clinical conditions. Furthermore, the intraoral location and the bracket surface were taken into account.

The null hypothesis of this study was that stainless steel and ceramic brackets show no differences in biofilm adhesion. The standard deviations were assumed to be unknown and unequal.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Hannover Medical School (No. 4347). The examination was performed with the understanding and written consent of each patient or parent if the patient was underage.

Criteria for participating in this study were: fixed appliance treatment with either stainless steel brackets (Mini Mono Brackets, Forestadent, Pforzheim, Germany) or ceramic brackets (Clarity, 3M Unitek, Monrovia, Calif), age 18 or younger, good general health (no infectious or noninfectious diseases, eg, HIV, diabetes), no antibiotic intake in the previous 6 weeks, nonsmoking, no history of periodontal disease, no extensive dental restorations, no professional tooth cleaning, and no use of antibacterial mouth rinses up to 6 weeks before appliance removal. Bracket collection was performed in consecutively debonded patients in a private practice until 10 patients from each sample, metal or ceramic, meeting the inclusion criteria were found. Before start of fixed treatment all patients had received therapy with removable appliances. The remaining malocclusion in the sample ranged from Class I molar relationship to a maximum of 3-mm Class II malocclusion measured from the mesial buccal cusp of the maxillary first molar.

The patients were divided into two groups. Group A comprised patients (three boys and seven girls, aged 13 to 17 years, mean 15.1 ± 1.3 years) treated with metal brackets (mean treatment time: 18.9 ± 2.8 months). Group B was composed of patients (three boys and seven girls, aged 14 to 18 years, mean 16.2 ± 1.2 years) treated with ceramic brackets (mean treatment time: 19.0 ± 3.7 months). Each group consisted of nine right-handed and one left-handed patient. Periodontal evaluation, debonding, and preparation of the brackets and the evaluation of the photomicrographs were performed by the same clinician.

Periodontal Evaluation

On the day of appliance removal, a periodontal examination including pocket probing depth (PPD), bleeding on probing (BOP), and plaque index (PI) of the testing sites was performed before debonding.19,20

PPD and BOP were obtained at six sites per tooth (distobuccal, buccal, mesiobuccal, mesiopalatal, palatal, distopalatal), whereas PI was determined for the buccal side using a marked periodontal probe (WHO DMS probe, Deppeler, Rolle, Switzerland).

Bracket Selection

All archwires were ligated using stainless steel ligatures. About one third of the brackets were additionally fastened with power chains (10 out of 30 in group A, 11 out of 30 in group B).

The brackets were carefully debonded with orthodontic pliers (angled bracket remover, Ortho Organizers, Carlsbad, Calif., and Unitek debonding instrument, 3M Unitek); care was taken to avoid iatrogenic biofilm dislodgement during the removal process. The archwire, steel ligatures, and power chains were then removed. The brackets of the maxillary right central incisor, canine, and second premolar were used. They were rinsed with an air/water syringe to loosen the debris, air-dried, and stored at room temperature in separate boxes until further analysis. Molars were not evaluated in the study as molars were banded.

Quantitative Analysis of Biofilm Formation

Biofilm formation was analyzed using Rutherford backscattering detection (RBSD), a scanning electron microscopy (SEM) technique (LEO 1455VP; Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany).16,21,22 This technique measures the backscattering of high-energy electrons impinging on a sample. Due to different atomic weights, areas with lighter elements (eg, carbon in biofilm) appear as dark surfaces, and areas with heavier elements (eg, iron in stainless steel brackets) appear as bright surfaces. For ceramic brackets, RBSD was carried out in the low-vacuum mode. Biofilm was verified with SEM at high magnification and energy dispersive x-ray spectroscopy (EDX), which permitted the elementary analysis and identification as an organic material (Figure 1A,B). The quantitative analysis was carried out with surface analysis software (Image J 1.43 for Windows; National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Md). After conversion to a binary display, the extent of biofilm coverage was calculated on the basis of the different grey values. Five RBSD photomicrographs per bracket from the mesial, distal, occlusal, gingival, and buccal views were obtained. A total of 60 brackets, 30 stainless steel and 30 ceramic, were examined (20 central incisor, 20 canine, 20 second premolar). Consequently, the analysis of quantitative biofilm formation was based on 300 microphotographs. In order to consider the irregular shape of brackets, sections of the surface were defined (eg, bracket wing, slot) and analyzed separately.

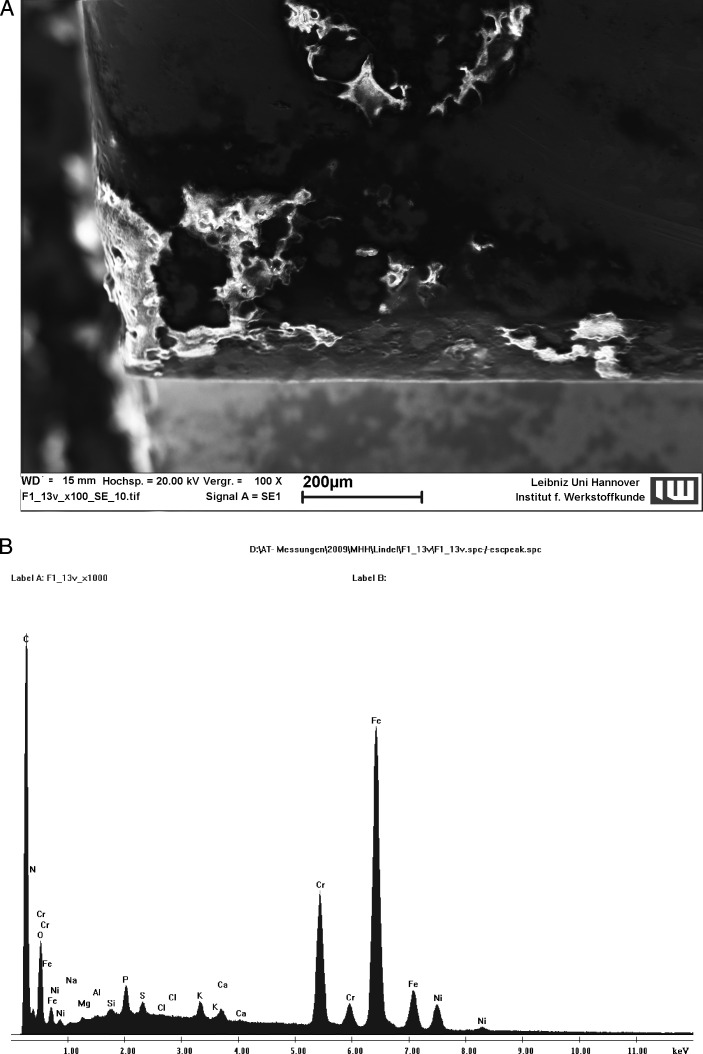

Figure 1.

Verification of the biofilm as an organic material by use of (A) SEM and (B) EDX.

Statistical Analysis

Power and sample sizes were calculated using PASS 2008 (NCSS, Kaysville, Utah). Power calculation revealed that with a sample size of 20, the application of the two-sided Mann-Whitney U-test at the level of 5% would have a power of 93% to detect a threefold increase of biofilm fraction, assuming a standard deviation of half of the biofilm fraction within each group. For the Bonferroni-corrected nominal alpha values .05/5 and .05/3, the power is 72% and 80%, respectively.

Documentation and evaluation of the data were performed with the Statistical Package for Social Sciences, version 17.0 for Windows (SPSS, Chicago, Ill). Firstly, the means and standard deviations of relative biofilm coverage were calculated for each aspect of a bracket. Furthermore, biofilm formation was calculated for each intraoral location and for each group.

The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was applied to test for normal distribution. As data were not distributed normally, a Mann-Whitney U-test was used to compare biofilm formation of each group. All tests were performed two-tailed with a significance level of α = .05. Separate Bonferroni corrections were performed for the comparisons of the intraoral locations and of the different bracket surfaces. Furthermore, data referring to gender, age, and treatment time were evaluated by Mann-Whitney U-test and Fisher exact test. Reproducibility of clinical measurements (PPD) was assessed by repeating measurements within a session and calculated using the method of Bland and Altman.23

RESULTS

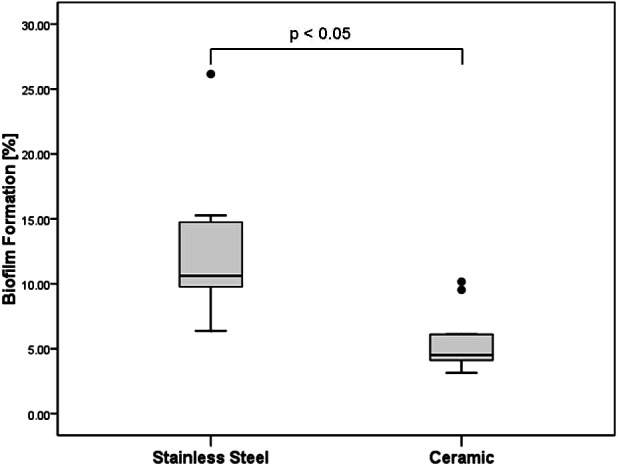

Detection of biofilm was positive on all brackets after removal from the oral cavity. A total surface of 26.3 ± 0.9 mm2 (stainless steel) and 27.2 ± 0.9 mm2 (ceramic) per bracket was analyzed. Figure 2 shows relative biofilm formation on the stainless steel and ceramic brackets. On stainless steel brackets, biofilm formation was observed on 12.5% ± 5.7% (3.3 ± 1.6 mm2) of the total surface and on 5.6% ± 2.4% (1.5 ± 0.6 mm2) on ceramic brackets. The difference between absolute and relative biofilm formation on stainless steel and ceramic was statistically significant (P > .05).

Figure 2.

Total relative biofilm formation on stainless steel and ceramic brackets in a box-plot presentation.

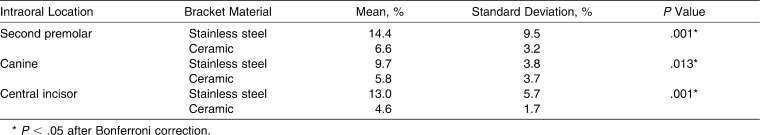

The results of biofilm accumulation with respect to intraoral location (central incisor, second premolar, and canine) are summarized in Table 1. The amount of biofilm was significantly higher on stainless steel brackets than on ceramic brackets (P < .001) for all intraoral locations.

Table 1.

Comparison of Relative Biofilm Formation on Stainless Steel and Ceramic Brackets With Respect to Intraoral Location

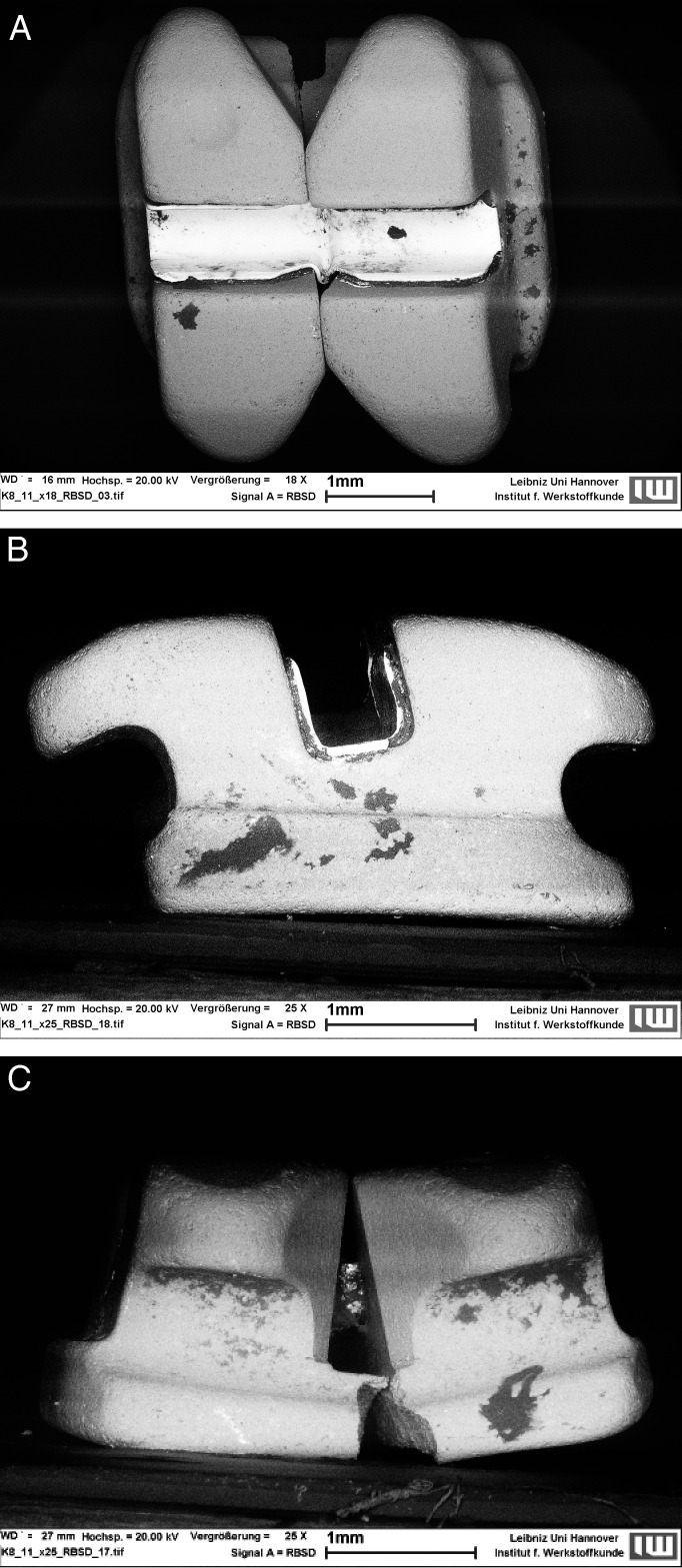

The same applies for the different bracket surfaces, apart from the occlusal and gingival surfaces: these values proved to be not significant (P > .05), as shown in Table 2. In both groups, the lowest values were found on the buccal surfaces. The greatest amount of biofilm was present on mesial and distal surfaces of the stainless steel brackets, and on occlusal and gingival surfaces of the ceramic brackets. Statistical analysis within groups showed significant differences between the bracket surfaces. Figures 3A–C and 4A–C depict representative micrographs of the two bracket materials with perspectives from the buccal, proximal, and gingival views.

Table 2.

Comparison of Relative Biofilm Formation With Respect To Bracket Surface

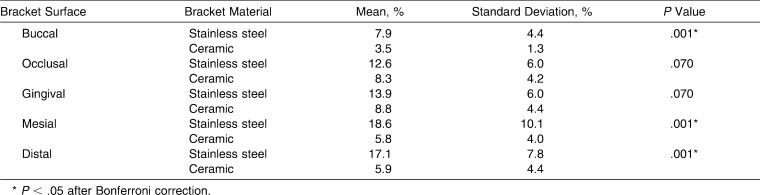

Figure 3a–C.

Representative micrographs of a stainless steel bracket with perspectives from (A) buccal, (B) proximal, and (C) gingival views. Dark areas represent biofilm-covered surfaces.

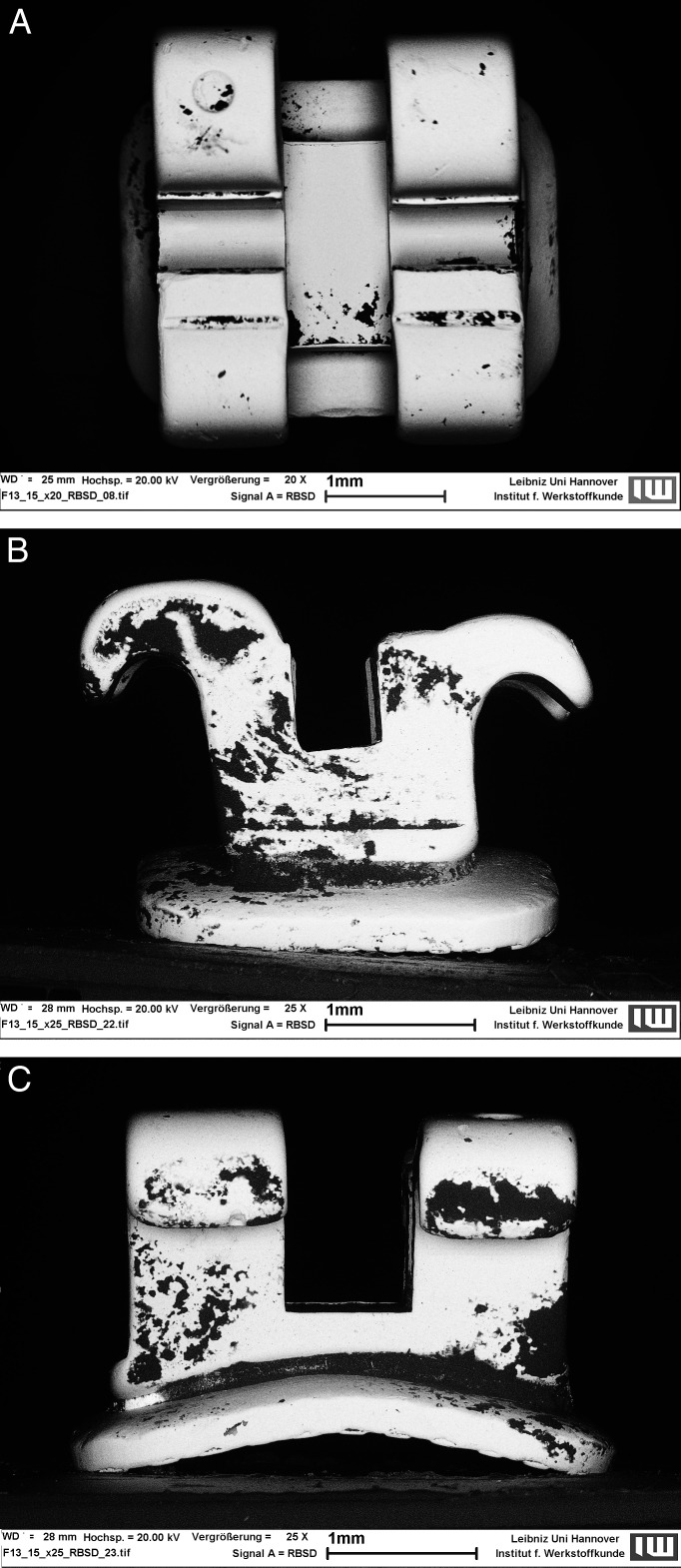

Figure 4a–C.

Micrographs taken from the (A) buccal, (B) proximal, and (C) gingival views showing less biofilm formation on a ceramic bracket.

Statistical analysis of data referring to gender, age, and treatment time showed no significant differences between both groups (P > .05). Regarding the reproducibility of periodontal measurements, the empirical standard deviation for PPD was 0.01 ± 0.01 mm, indicating excellent reproducibility. The periodontal examination showed a greater quantity of plaque accumulation and gingival inflammation in the stainless steel group compared with the ceramic group, but the difference was not significant (P > .05). BOP of the examined sites was positive in 5.6% ± 7.4% (stainless steel group) and in 3.3% ± 1.3% (ceramic group). Mean PI and PPD were 1.7 ± 0.9 mm and 1.8 ± 0.5 mm (stainless steel group), and 1.5 ± 0.8 mm and 1.5 ± 0.2 mm (ceramic group), respectively.

DISCUSSION

After insertion of fixed orthodontic appliances, an initial biofilm is formed on bracket surfaces, clinically resulting in a worsening of periodontal values; but after an initial period, the host-microorganism balance is reestablished.24 However, the bracket surface alters its characteristics over time. On intraoral materials, wear from food and drink, oral hygiene, or corrosion processes can be found.25,26 Such signs of wear could have an influence on surface roughness or surface free energy and would consequently have a significant impact on long-term biofilm formation.27 Therefore, the present investigation was performed after completion of treatment with fixed orthodontic appliances to evaluate the clinical significance of the bracket material on long-term biofilm formation.

There is evidence that the choice of the ligation method has an influence on the amount of biofilm and the gingival conditions. In a clinical study, it was shown that the use of elastomeric rings promotes significant retention of biofilm compared to stainless steel ligatures.28 To minimize the confounder “ligation mode” in the present investigation, all brackets were ligated using stainless steel ligatures. In both groups, an equal number of brackets was additionally covered by a power chain, allowing statistical comparison.

The literature states that posterior teeth tend to be more affected than anterior teeth in terms of plaque accumulation and gingival inflammation.6 To evaluate this impact of intraoral location on biofilm formation, the samples were collected from an anterior, middle, and posterior region of the mouth.

In the present study, long-term biofilm formation on different bracket materials was analyzed in adolescent patients. This age cohort was chosen because it is the major treatment group in orthodontics. To avoid interobserver discrepancies, periodontal evaluation, debonding, and preparation of the brackets, as well as the evaluation of the photomicrographs were performed by the same clinician.

Biofilm formation was quantitatively analyzed using the RBSD technique, as employed in previous studies.21,29 This SEM technique produces photomicrographs that permit a computer-assisted evaluation of the covered surfaces according to a binary display of different grey values. With regard to the reproducibility of this method, the empirical standard deviation for biofilm coverage can be assumed to be lower than 1%, indicating good reproducibility.22

The applied method allows a two-dimensional analysis of biofilm coverage. However, evaluation of biofilm thickness or bacterial diversity is not possible.

Due to material-specific properties, the bracket morphology of metal and ceramic brackets differs. Therefore, selection of bracket types for analysis was performed by regarding the parameters comparable design, similar size, and accessibility. To reduce the remaining discrepancies, the relative amount of biofilm formation was taken into account.

The null hypothesis was rejected because surface analysis revealed significantly lower relative biofilm values on ceramic brackets, regardless of their position, implying a dependency on the material of long-term biofilm formation.

The question of which bracket material is more prone to biofilm adherence and plaque retention is discussed contentiously in the literature. In an in vitro study, metal brackets showed a lower initial affinity to bacterial accumulation (Streptococcus mutans) compared with ceramic or plastic brackets. However, no significant difference in adherence was found over time.17

Another in vivo study compared the plaque-retaining capacity of metal vs ceramic brackets by counting the levels of different bacterial species on the day of debonding. There were no significant differences found in the accumulation of caries-inducing bacterial species. Concerning periodontal pathogens, a species-specific colonization was found, but globally no obvious pattern was identified.18

In contrast to the results of the present study, no favorable bracket material was identified by the use of a molecular biology technique that allowed a qualitative analysis of the adherent biofilm under long-term conditions.

In agreement with the results of the present investigation, other studies indicate a higher plaque affinity of stainless steel brackets. Eliades et al.15 discovered that the critical surface tension and total work of adhesion of stainless steel brackets is higher compared with ceramic or plastic brackets, implying an increased plaque-retaining capacity. When examining the adhesion of lipopolysaccharides of Escherichia coli and Porphyromonas gingivalis, stainless steel brackets exhibited significantly stronger bonds.30 S. mutans also showed a greater affinity to metal brackets compared to ceramics or plastic ones.31

Comparison of the individual bracket surfaces also showed material-specific advantages of ceramic on the buccal, mesial, and distal surfaces. The difference in biofilm adhesion on occlusal and gingival surfaces was not statistically significant, although a positive tendency towards ceramic was detectable. The values indicate that investigation of a larger cohort could result in statistically significant differences.

In both groups, biofilm was chiefly located on surfaces which were fairly protected from mechanical removal. The highest amount of biofilm coverage on metal brackets was found on the mesial and distal surfaces, as corroborated by another in vivo study.22 For both materials, the lowest values were found on buccal aspects, which are more exposed to intraoral shear forces from the muscles, tongue, and salivary flow.6,32

A limitation of the present study is that periodontal parameters were not recorded at the beginning of treatment and before bracket bonding in order to ensure that patients of both groups initially presented similar amounts of oral biofilm. As bracket placement was only performed when no gingival inflammation was present and as the quality of oral hygiene might change over a period of 18 months, this limitation particularly can be neglected.

The evaluation of the periodontal parameters showed no significant differences between the two groups, although a tendency towards favorable results for ceramic brackets was obvious. It is possible that a larger cohort is necessary to evaluate the influence of the bracket material on the periodontium. Future studies should examine whether the difference in biofilm accumulation between metal and ceramic brackets has a clinically significant impact on the development of decalcifications. Those differences might have an impact when selecting bracket material in patients with poor oral hygiene.

CONCLUSIONS

A significantly lower amount of biofilm was found on ceramic brackets than on stainless steel brackets.

The material-specific differences in biofilm formation occurred in all intraoral locations, as well as on most of the bracket surfaces (buccal, mesial, and distal).

With respect to long-term biofilm formation, ceramic brackets appear to exhibit advantageous material properties.

This superiority did not have a significant impact on periodontal parameters.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Professor Dr H. Hecker, Institute of Biostatistics, Hannover Medical School, for assistance with the statistical analysis. Furthermore, we thank Dr M. Sostmann and Dr J. Buken (private orthodontic practice, Hannover, Germany) for their support during the conduction of the study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Thurow R. C. Edgewise Orthodontics 3rd ed. St Louis, Mo: Mosby; 1972. pp. 22–34, 148, 270. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chin M. Y. H. Biofilms in Orthodontics. Haren, Netherlands: Drukkerij G. Van Ark; 2007. p. 16. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boyd R. L. Longitudinal evaluation of a system for self-monitoring plaque control effectiveness in orthodontic patients. J Clin Periodontol. 1983;10:380–388. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1983.tb01287.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee S. M, Yoo S. Y, Kim H. S, Kim K. W, Yoon Y. J, Lim S. H, Shin H. Y, Kook J. K. Prevalence of putative periodontopathogens in subgingival dental plaques from gingivitis lesions in Korean orthodontic patients. J Microbiol. 2005;43:260–265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Paolantonio M, Pedrazzoli V, di Murro C, di Placido G, Picciani C, Catamo G, De Luca M, Piaccolomini R. Clinical significance of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans in young individuals during orthodontic treatment. A 3-year longitudinal study. J Clin Periodontol. 1997;24:610–617. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1997.tb00237.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zachrisson S, Zachrisson B. U. Gingival condition associated with orthodontic treatment. Angle Orthod. 1972;42:26–34. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(1972)042<0026:GCAWOT>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Atack N. E, Sandy J. R, Addy M. Periodontal and microbiological changes associated with the placement of orthodontic appliances. A review. J Periodontol. 1996;67:78–85. doi: 10.1902/jop.1996.67.2.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van Gastel J, Quirynen M, Teughels W, Coucke W, Carels C. Longitudinal changes in microbiology and clinical periodontal variables after placement of fixed orthodontic appliances. J Periodontol. 2008;79:2078–2086. doi: 10.1902/jop.2008.080153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chapman J. A, Roberts W. E, Eckert G. J, Kula K. S, Gonzalez-Cabezas C. Risk factors for incidence and severity of white spot lesions during treatment with fixed orthodontic appliances. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2010;138:188–194. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2008.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ogaard B, Rolla G, Arends J. Orthodontic appliances and enamel demineralization. Part 1. Lesion development. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1988;94:68–73. doi: 10.1016/0889-5406(88)90453-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Naranjo A. A, Trivino M. L, Jaramillo A, Betancourth M, Botero J. E. Changes in the subgingival microbiota and periodontal parameters before and 3 months after bracket placement. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2006;130:275.e17–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2005.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alexander S. A. Effects of orthodontic attachments on the gingival health of permanent second molars. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1991;100:337–340. doi: 10.1016/0889-5406(91)70071-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ogaard B. Prevalence of white spot lesions in 19-year-olds: a study on untreated and orthodontically treated persons 5 years after treatment. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1989;96:423–427. doi: 10.1016/0889-5406(89)90327-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Quirynen M. The clinical meaning of the surface roughness and the surface free energy of intra-oral hard substrata on the microbiology of the supra- and subgingival plaque: results of in vitro and in vivo experiments. J Dent. 1994;22(suppl 1):13–16. doi: 10.1016/0300-5712(94)90165-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eliades T, Eliades G, Brantley W. A. Microbial attachment on orthodontic appliances: I. Wettability and early pellicle formation on bracket materials. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1995;108:351–360. doi: 10.1016/s0889-5406(95)70032-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elter C, Heuer W, Demling A, Hannig M, Heidenblut T, Bach F. W, Stiesch-Scholz M. Supra- and subgingival biofilm formation on implant abutments with different surface characteristics. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2008;23:327–334. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fournier A, Payant L, Bouclin R. Adherence of Streptococcus mutans to orthodontic brackets. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1998;114:414–417. doi: 10.1016/s0889-5406(98)70186-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Anhoury P, Nathanson D, Hughes C. V, Socransky S, Feres M, Chou L. L. Microbial profile on metallic and ceramic bracket materials. Angle Orthod. 2002;72:338–343. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(2002)072<0338:MPOMAC>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Silness J, Loe H. Periodontal disease in pregnancy. II. Correlation between oral hygiene and periodontal condtion. Acta Odontol Scand. 1964;22:121–135. doi: 10.3109/00016356408993968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lang N. P, Adler R, Joss A, Nyman S. Absence of bleeding on probing. An indicator of periodontal stability. J Clin Periodontol. 1990;17:714–721. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1990.tb01059.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Demling A, Heuer W, Elter C, Heidenblut T, Bach F. W, Schwestka-Polly R, Stiesch-Scholz M. Analysis of supra- and subgingival long-term biofilm formation on orthodontic bands. Eur J Orthod. 2009;31:202–206. doi: 10.1093/ejo/cjn090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Demling A, Elter C, Heidenblut T, Bach F. W, Hahn A, Schwestka-Polly R, Stiesch M, Heuer W. Reduction of biofilm on orthodontic brackets with the use of a polytetrafluoroethylene coating. Eur J Orthod. 2010;32:414–418. doi: 10.1093/ejo/cjp142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bland J. M, Altman D. G. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet. 1986;1:307–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ristic M, Vlahovic Svabic M, Sasic M, Zelic O. Clinical and microbiological effects of fixed orthodontic appliances on periodontal tissues in adolescents. Orthod Craniofac Res. 2007;10:187–195. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-6343.2007.00396.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Matasa C. G. Pros and cons of the reuse of direct-bonded appliances. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1989;96:72–76. doi: 10.1016/0889-5406(89)90232-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lin M. C, Lin S. C, Lee T. H, Huang H. H. Surface analysis and corrosion resistance of different stainless steel orthodontic brackets in artificial saliva. Angle Orthod. 2006;76:322–329. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(2006)076[0322:SAACRO]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Quirynen M, Bollen C. M. The influence of surface roughness and surface-free energy on supra- and subgingival plaque formation in man. A review of the literature. J Clin Periodontol. 1995;22:1–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1995.tb01765.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alves de Souza R, Borges de Araujo Magnani M. B, Nouer D. F, Oliveira da Silva C, Klein M. I, Sallum E. A, Goncalves R. B. Periodontal and microbiologic evaluation of 2 methods of archwire ligation: ligature wires and elastomeric rings. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2008;134:506–512. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2006.09.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Heuer W, Elter C, Demling A, et al. Analysis of early biofilm formation on oral implants in man. J Oral Rehabil. 2007;34:377–382. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2842.2007.01725.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Knoernschild K. L, Rogers H. M, Lefebvre C. A, Fortson W. M, Schuster G. S. Endotoxin affinity for orthodontic brackets. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1999;115:634–639. doi: 10.1016/s0889-5406(99)70288-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ahn S. J, Kho H. S, Lee S. W, Nahm D. S. Roles of salivary proteins in the adherence of oral streptococci to various orthodontic brackets. J Dent Res. 2002;81:411–415. doi: 10.1177/154405910208100611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hannig M. Transmission electron microscopy of early plaque formation on dental materials in vivo. Eur J Oral Sci. 1999;107:55–64. doi: 10.1046/j.0909-8836.1999.eos107109.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]