Abstract

The pharmacodynamics of an investigational glycopeptide, LY333328 (LY), alone and in combination with gentamicin, against one vancomycin-susceptible and two vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium strains were studied with a multiple-dose, in vitro pharmacodynamic model (PDM). Dose-range data for the PDM studies were obtained from static time-kill curve studies. In PDM experiments conducted over 48 h, peak LY concentrations of 0.1× and 1× the MIC every 24 h and peak gentamicin concentrations of 18 μg/ml every 24 h (Gq24h) and 6 μg/ml every 8 h (Gq8h) were studied alone and in the four possible LY-gentamicin combinations. Compared to either antibiotic alone, LY-gentamicin combination regimens produced significantly higher apparent killing rates (KRs) calculated during the initial 2 h postdosing. The mean KRs for LY or gentamicin alone versus those for the LY-gentamicin combination regimens were 0.35 ± 0.55 log10 CFU/ml/h (95% confidence interval [CI95%], 0 to 0.70) and 1.46 ± 0.71 log10 CFU/ml/h (CI95%, 1.01 to 1.91), respectively (P < 0.0001). Bacterial killing at 48 h (BK48), which was calculated by subtracting the bacterial counts at 48 h from the initial inoculum, with a negative value indicating net growth, was also significantly greater. The mean BK48s were −0.69 ± 0.44 log10 CFU/ml (CI95%, −0.41 to −0.97) and 3.72 ± 2.28 log10 CFU/ml (CI95%, 2.28 to 5.17) for LY or gentamicin alone versus LY-gentamicin combination regimens, respectively (P < 0.0001). None of the 12 regimens with LY or gentamicin alone but 75% (9 of 12) of the LY-gentamicin combination regimens were bactericidal. Eighty-three percent (10 of 12) of the LY-gentamicin combination regimens also demonstrated synergy. No significant differences between the pharmacodynamics of LY-gentamicin combination regimens containing Gq24h versus those containing Gq8h were detected.

Over the past decade, a significant increase in the prevalence of nosocomial enterococcal infections has been observed (11). Of greater concern has been the notable rise in multiple-drug-resistant strains and the difficulty encountered in the treatment of such pathogens (8, 10, 11, 19). In the United States, the prevalence of vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE), most commonly in Enterococcus faecium and frequently in association with multiple-drug resistance, increased 20-fold from 1989 to 1995 (7). VRE are often responsible for severe infections for which the antibiotic selection is limited for patients with significant comorbid diseases. These factors may explain the reported associations between vancomycin resistance and the increased mortality rates among patients with enterococcal bacteremia (4, 5, 18).

The treatment of systemic enterococcal infections is directed by antibiotic susceptibilities and may include single agents or combinations of penicillins, glycopeptides, aminoglycosides, quinolones, and other antibiotics (10). As levels of resistance continue to increase, antibiotic selection becomes more limited, and in some cases an appropriate antibiotic is unavailable. There is an urgent need for new antibiotics with activity against multiple-drug-resistant Enterococcus, specifically VRE. Preliminary susceptibility studies have demonstrated the promising activity of a class of glycopeptide derivatives which are related to vancomycin (9, 14, 15). Static time-kill curve studies of one compound, LY333328 (LY), have shown that it has dose-dependent, bactericidal activity against Enterococcus spp. including those with high-level resistance to vancomycin (16, 21). Only a few studies have investigated the potential for synergy between LY and gentamicin against aminoglycoside-sensitive, vancomycin-resistant strains (12, 20). Furthermore, there are no published data regarding the use of LY in combination with gentamicin administered once daily (Gq24h) versus the use of LY in combination with gentamicin administered thrice daily (Gq8h) against enterococcus.

The primary purpose of this research was to characterize the activity of LY against vancomycin-resistant E. faecium with a multiple-dose, in vitro pharmacodynamic model (PDM). The research included comparisons of (i) LY or gentamicin alone versus LY-gentamicin combination regimens (i.e., synergy) and (ii) LY-gentamicin combination regimens containing Gq24h versus the same combination regimens but with Gq8h against VRE in a PDM.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

Three E. faecium isolates obtained from cultures of blood were studied. The strains included a vancomycin-susceptible strain (strain 1338), PCR-positive vanB strain 563, and PCR-positive vanA strain 561. All strains had low-level aminoglycoside resistance.

Antibiotics and in vitro susceptibility testing.

LY (Eli Lilly & Co., Indianapolis, Ind.), vancomycin (Eli Lilly & Co.), teicoplanin (Merrel Dow, Laval, Quebec, Canada), and gentamicin (Schering Corp. Ltd,. Pointe-Claire, Quebec, Canada) MICs were determined in Mueller-Hinton broth (MHB; Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.) supplemented with 25 μg of calcium per ml and 12.5 μg of magnesium per ml by the broth macrodilution method described by the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards (13). Vancomycin and teicoplanin MICs were determined to confirm the phenotypic designations of the isolates. Gentamicin MICs were determined to select isolates with low-level aminoglycoside resistance. MICs were verified in triplicate on separate occasions.

Static time-kill curve studies.

Dose-range data for the PDM studies were obtained from static time-kill curve experiments. Single-dose, static time-kill curve experiments were conducted over 24 h for LY alone and for LY in combination with gentamicin against all strains (20, 21). Static time-kill curve studies were performed in flasks containing total volumes of 10 ml. The volume of water used from drug stock solutions was limited to 0.1 ml. The bacteria were grown to the logarithmic phase by inoculating cation-supplemented MHB (CSMHB) which was incubated in a shaking water bath at 37°C for 1.5 h. One-milliliter aliquots containing 108 CFU/ml were added to 9 ml of CSMHB to yield an initial inoculum of approximately 107 CFU/ml. This initial inoculum was selected for all static time-kill curve and PDM experiments to enable the detection of synergy between LY and gentamicin. LY concentrations of 1×, 10×, 20×, 50×, and 100× the MIC were studied alone and in combination with gentamicin concentrations of 6 μg/ml. LY concentrations were empirically selected, whereas the gentamicin concentration was based on the levels achieved in blood with traditional dosage regimens (i.e., 1 to 1.5 mg/kg of body weight given every 8 h). Samples (0.1 ml) were collected at 0, 1, 2, 4, 8, and 24 h. Samples were serially diluted in normal saline at 4°C; 10- and 100-μl aliquots were plated in duplicate onto blood agar, and the plates were incubated at 35°C for 24 h. Viable colonies present at between 10 and 100 per plate were counted, and a lower limit of detection of 102 CFU/ml was used. All experiments were performed in triplicate on separate occasions.

Residual antibiotic effects were assessed during initial experiments by running concurrent samples which were washed twice to remove antibiotic. Washing was performed by centrifugation at 4,000 × g for 10 min, decanting of the supernatant, and resuspension of the pellet in CSMHB. The colony counts from unwashed and washed samples were compared.

PDM studies.

A multiple-dose, one-compartment PDM was used to simulate the treatment of bacteremic infections over 48 h (6). The central chambers (690 ml) contained CSMHB which was stirred with magnetic bars and heated to 37°C in a water bath. The bacteria were grown to the logarithmic phase in flasks and were injected into the central chambers to provide initial inocula of approximately 107 CFU/ml. Bacterial growth, as confirmed by colony counts, was permitted for 1 h following inoculation and for another hour during equilibration of the PDM.

Antibiotic doses were injected into the central chambers at appropriate intervals to produce the desired peak and trough concentrations. All antibiotic concentrations in the PDM represented steady-state, free levels which simulate the active antibiotic component. Free antibiotic concentrations in vivo, which are dependent on protein binding and which are proportionally related to the total concentrations in serum, can be calculated for antibiotics with known levels of protein binding (i.e., 77% for LY on the basis of data from studies with animals).

Because the primary purpose of the PDM studies was to investigate the potential for synergy between LY and gentamicin, low concentrations of the investigational compound, LY, were used. The static time-kill curve experiments demonstrated maximal activity (i.e., less than the lower limit of detectable colonies at 24 h) for all LY-gentamicin combination regimens containing LY at ≥10× the MIC, and therefore, only the lowest LY concentration of 1× the MIC was selected for use in the PDM studies (20, 21). An even lower sub-MIC of 0.1× the MIC was also chosen to study potential synergy between LY and gentamicin. On the other hand, gentamicin is an established antibiotic which would be used only in combination for the treatment of enterococcal infections. As a result, clinically relevant gentamicin concentrations were used including peak levels of 18 μg/ml in regimens containing Gq24h and 6 μg/ml in regimens containing Gq8h. All LY and gentamicin dosage regimens were studied alone and in the four possible LY-gentamicin combinations.

When LY or gentamicin was tested alone, fresh CSMHB was pumped through the central chambers at flow rates producing half-lives of either 24 h for LY or 2 h for gentamicin. During studies with the drug combinations, fresh broth or LY-supplemented broth was delivered by separate computerized pumps at flow rates that concurrently produced the LY and gentamicin half-lives (1). Samples (0.1 ml) were collected at 0, 1, 2, 5 or 6, 24, 25, 26, 29 or 30, and 48 h. During experiments with Gq8h only, samples were also collected at 8, 10, 16, 18, 32, 34, 40, and 42 h. The samples were then processed as described above for the time-kill curve experiments. The pharmacokinetic profiles obtained in the PDM were verified by determining gentamicin concentrations by immunoassay (TDx; Abbott, Chicago, Ill.) in the samples obtained at 2, 6, and 24 h. All experiments were performed in triplicate on separate occasions.

For both static time-kill curve and PDM experiments, bacterial killing curves were constructed by plotting the mean log10 CFU per milliliter versus time. Activity including apparent kill rates (KRs) during the initial 2 h postdosing, and the bacterial killing (BK) at 24 h (BK24) and 48 h (BK48) were measured. BK was calculated by subtracting the bacterial counts at 24 or 48 h from the initial inoculum, with negative values indicating net growth. Results from the PDM studies were used to compare the activity of LY or gentamicin alone to the activities of the LY-gentamicin combination regimens. Bactericidal activity was defined as a BK of ≥3 log10 CFU/ml at 24 or 48 h. Synergy was determined from PDM experiments and was defined as a ≥2 log10 decrease in the numbers of CFU per milliliter between the combination and its most active constituent at 24 and 48 h when at least one of the agents was present at a concentration that did not affect the growth curve of the test organism when the agent was used alone (17). Finally, the activities of Gq24h- versus Gq8h-containing combination regimens were compared. Statistical comparisons were performed by a t test (α = 0.05).

RESULTS

Susceptibility testing.

Vancomycin, teicoplanin, LY, and gentamicin MICs were 0.5, 0.25, 0.06, and 16 μg/ml, respectively for strain 1338 (vancomycin sensitive), 16, 0.5, 0.03, and 32 μg/ml, respectively, for strain 563 (vanB), and 512, 32, 0.25, and 16 μg/ml, respectively, for strain 561 (vanA). Isolate 1338 was vancomycin and teicoplanin sensitive. Strain 563 demonstrated low-level vancomycin resistance and teicoplanin sensitivity, whereas strain 561 had high-level vancomycin resistance and teicoplanin resistance. The LY MICs were similar for strain 1338 and strain 563, but the LY MIC for strain 561 was higher. All strains demonstrated low-level aminoglycoside resistance, with MICs of either 16 or 32 μg/ml.

Static time-kill curve study results.

The colony count variation at each time point within and between experiments was less than 10%. In addition, no antibiotic carryover was observed, as detected from the colony counts for unwashed samples. KR and BK24 results from the static time-kill curve studies are presented in Tables 1 and 2, respectively. For LY alone, the KR and BK24 were dose dependent over the concentration range studies for all strains. Variability in parameters was demonstrated between strains. For example, although the KR against 561 (vanA) was less than those against the other strains at 1×, 10×, and 20× the MIC, it was higher than those against the other strains at 50× and 100× the MIC. Furthermore, LY at 20× the MIC was bactericidal against 1338 (vancomycin susceptible) and 561 (vanA) but was not bactericidal against 563 (vanB) until the concentration was 100× the MIC.

TABLE 1.

Time-kill curve KRs for LY alone and in combination with gentamicina

| LY concn (× MIC) | KR (log10 CFU/ml/h)

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1338

|

563 (vanB)

|

561 (vanA)

|

||||

| LY | LY + G | LY | LY + G | LY | LY + G | |

| 1× | 0.73 | 3.53 | 0.69 | 1.27 | 0.35 | 0.53 |

| 10× | 2.40 | 3.69 | 1.90 | 2.98 | 0.43 | 1.35 |

| 20× | 2.30 | 4.10 | 1.90 | 3.55 | 0.89 | 2.90 |

| 50× | 2.95 | 3.80 | 1.93 | 3.01 | 3.21 | 4.34 |

| 100× | 3.00 | 5.00 | 3.48 | 5.00 | 5.00 | 5.00 |

The KR was calculated during the initial 2 h postdosing. G, gentamicin.

TABLE 2.

BK24 time-kill curves for LY alone and in combination with gentamicina

| LY concn (× MIC) | BK24 (log10 CFU/ml)

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1338

|

563 (vanB)

|

561 (vanA)

|

||||

| LY | LY + G | LY | LY + G | LY | LY + G | |

| 1× | 0.03 | 5.00 | −1.44 | 3.14 | −1.10 | 4.03 |

| 10× | 2.64 | 5.00 | 1.03 | 5.00 | 1.39 | 5.00 |

| 20× | 3.72 | 5.00 | 1.12 | 5.00 | 3.00 | 5.00 |

| 50× | 5.00 | 5.00 | 1.64 | 5.00 | 5.00 | 5.00 |

| 100× | 5.00 | 5.00 | 3.88 | 5.00 | 5.00 | 5.00 |

BK24 was calculated by subtracting the bacterial count at 24 h from the initial inoculum, with a negative value indicating net growth. G, gentamicin.

Compared to LY alone, LY-gentamicin combination regimens produced higher KRs; however, the difference was not statistically significant. The mean KRs for LY alone and the LY-gentamicin combination regimens were 2.1 log10 CFU/ml/h (95% confidence interval [CI95%], 1.3 to 2.8) and 3.3 log10 CFU/ml/h (CI95%, 2.6 to 4.1), respectively (P > 0.05). Compared to LY alone, LY-gentamicin combination regimens increased the BK24 significantly, with mean values of 2.4 log10 CFU/ml (CI95%, 1.2 to 3.6) and 4.8 log10 CFU/ml (CI95%, 4.5 to 5.1), respectively (P < 0.0001). The addition of gentamicin lowered the bactericidal concentrations of LY (i.e., the LY concentration required to kill ≥3 log10 CFU/ml) significantly to 1× the MIC against all strains.

PDM study results.

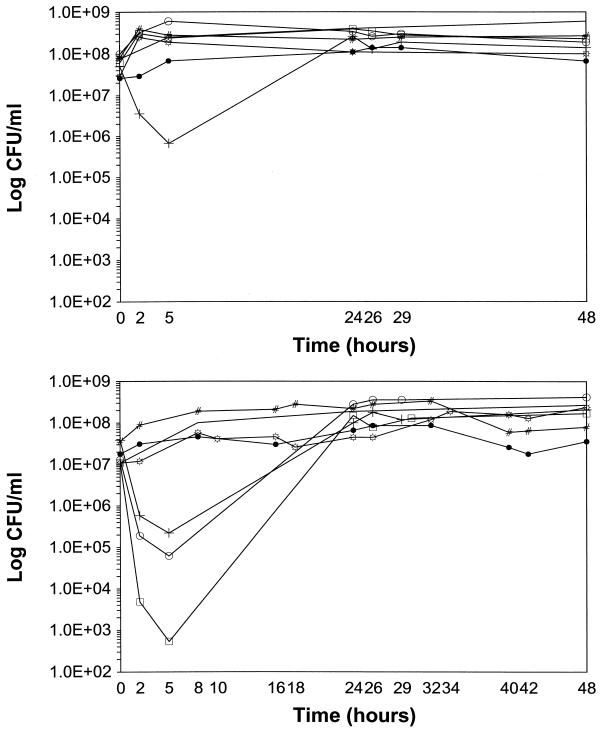

The pharmacokinetic profiles in the central chambers of the PDM were verified by gentamicin concentration determinations. Extrapolated peak levels and calculated elimination rates (i.e., half-lives) were within 10% of the expected values (i.e., peak level = 18 or 6 mg/liter and half-life = 2 h). The colony count variation at each time point within and between experiments was less than 10%. In addition, no antibiotic carryover was observed, as detected from the colony counts for unwashed samples. PDM killing curves for LY alone at 0.1× and 1× the MIC are depicted in Fig. 1A. LY at 0.1× the MIC produced no bacterial killing, with net growth at 24 and 48 h. Although the first doses of LY at 1× the MIC produced modest KRs of 0.57, 0, and 0.17 log10 CFU/ml/h against strains 1338, 563 (vanB), and 561 (vanA), respectively, regrowth to the initial inoculum occurred at 24 h. Second doses of LY had minimal KRs against all strains tested. PDM killing curves for Gq24h and Gq8h alone are presented in Fig. 1B. The Gq8h regimen had no activity, whereas the first doses of the Gq24h regimen produced notable killing of all strains. Again, regrowth to the initial inoculum occurred at 24 h.

FIG. 1.

(A) BK curves for LY against E. faecium in a multiple-dose, in vitro PDM. −, growth control; ○, LY at 0.1× the MIC against strain 1338 (vancomycin sensitive); +, LY at 1× the MIC against strain 1338 (vancomycin sensitive); □, LY at 0.1× the MIC against strain 563 (vanB); #, LY at 1× the MIC against strain 563 (vanB); ●, LY at 0.1× the MIC against strain 561 (vanA); ☼, LY at 1× the MIC against strain 561 (vanA). (B) BK curves for regimens with Gq24h and Gq8h against E. faecium in a multiple-dose, in vitro PDM. −, growth control; ○, Gq24h against strain 1338 (vancomycin sensitive); +, Gq24h against strain 563 (vanB); □, Gq24h against strain 561 (vanA); #, Gq8h against strain 1338 (vancomycin susceptible); ●, Gq8h against strain 563 (vanB); ☼, Gq8h against strain 561 (vanA).

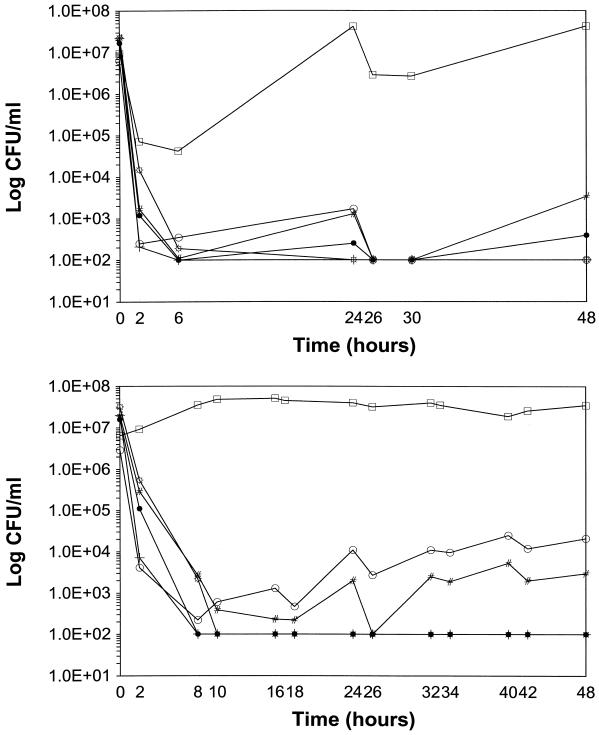

PDM killing curves for LY-Gq24h and LY-Gq8h combination regimens are depicted in Fig. 2A and B, respectively. Compared to either drug alone, the LY-gentamicin combination regimens produced significantly higher KRs, with mean values of 0.35 ± 0.55 log10 CFU/ml/h (CI95%, 0 to 0.70) and 1.46 ± 0.71 log10 CFU/ml/h (CI95%, 1.01 to 1.91), respectively (P < 0.0001). BK48 was also significantly greater, with mean values of −0.69 ± 0.44 log10 CFU/ml (CI95%, −0.41 to −0.97) and 3.72 ± 2.28 log10 CFU/ml (CI95%, 2.28 to 5.17) for LY or gentamicin alone versus the combination regimens, respectively (P < 0.0001). None of the regimens with LY or gentamicin alone were bactericidal, whereas 75% (9 of 12) of the LY-gentamicin combination regimens were bactericidal at both 24 and 48 h. The exceptions were regimens containing LY at 0.1× the MIC against strain 563 (vanB), which had regrowth to the level of the initial inoculum at 24 and 48 h, and the regimen with LY at 0.1× the MIC and Gq8h against strain 1338 (vancomycin susceptible), which produced BKs of 2.41 and 2.13 log10 CFU/ml at 24 and 48 h, respectively. Eighty-three percent (10 of 12) of the LY-gentamicin combination regimens were synergistic at both 24 and 48 h. The exceptions again included the regimen containing LY at 0.1× the MIC against strain 563 (vanB).

FIG. 2.

(A) BK curves for LY in combination with Gq24h against E. faecium in a multiple-dose, in vitro PDM. ○, LY at 0.1× the MIC against strain 1338 (vancomycin sensitive); +, LY at 1× the MIC against strain 1338 (vancomycin sensitive); □, LY at 0.1× the MIC against strain 563 (vanB); #, LY at 1× the MIC against strain 563 (vanB); ●, LY at 0.1× the MIC against strain 561 (vanA); ☼, LY at 1× the MIC against strain 561 (vanA). (B) BK curves for LY in combination with Gq8h against E. faecium in a multiple-dose, in vitro PDM. ○, LY at 0.1× the MIC against strain 1338 (vancomycin sensitive); +, LY at 1× the MIC against strain 1338 (vancomycin sensitive); □, LY at 0.1× the MIC against strain 563 (vanB); #, LY at 1× the MIC against strain 563 (vanB); ●, LY at 0.1× the MIC against strain 561 (vanA); ☼, LY at 1× the MIC against strain 561 (vanA).

There was no statistically significant difference in the pharmacodynamic parameters of LY-gentamicin combination regimens containing Gq24h versus those containing Gq8h. The mean KRs were 1.92 ± 0.51 log10 CFU/ml/h (CI95%, 1.38 to 2.46) and 1.01 ± 0.59 log10 CFU/ml/h (CI95%, 0.39 to 1.62) for the regimens containing Gq24h and Gq8h, respectively (P > 0.05). Mean BK48s were also similar, with values of 3.91 ± 2.31 log10 CFU/ml (CI95%, 1.48 to 6.33) and 3.54 ± 2.45 log10 CFU/ml (CI95%, 0.97 to 6.11) for the regimens containing Gq24h and Gq8h, respectively (P > 0.05).

DISCUSSION

The methodology, antibiotic concentrations, bacterial inoculum, and measured endpoints can all influence the results of synergy testing (2). Traditional techniques (i.e., checkerboards and static time-kill curve studies) and the extrapolation of their results to the in vivo situation have obvious limitations. In comparison, PDM more closely simulates the antibiotic concentrations observed in vivo and allows the study of multiple-dose regimens over prolonged periods. PDM offers an alternative method for synergy testing and warrants further investigation (2). An important consideration, however, is the variation in PDM studies (i.e., design and analysis), with our infection model, for example, most closely simulating the activities of free antibiotic concentrations obtained from multiple-dose regimens against bacteria in the blood of immunocompromised patients. As a result, methodological standards for the use of synergy testing with the PDM should be developed.

As was consistent with our static time-kill curve data, LY alone at the low doses used in the PDM studies demonstrated little activity (20, 21). In humans, LY dosage regimens and their resulting concentrations are still being studied. In addition, there is controversy regarding the pharmacokinetics of LY, with recent data suggestive of a considerably longer half-life than the 24 h used in this study (3). For reasons discussed earlier, we were conservative in that we selected low LY concentrations (i.e., 0.1× and 1× the MIC) for use in the PDM. This, in addition to the use of a shorter than actual half-life in our experiments, would have, if anything, produced a situation that underestimated the activity of LY.

The significant activities of some regimens with gentamicin alone may have been related to the peak concentrations achieved in the PDM (Fig. 1B). The regimens with Gq8h alone produced peak concentrations (i.e., 6 μg/ml) well below the MICs for the isolates (i.e., 16 to 32 μg/ml) and were relatively inactive. In comparison, the regimens with Gq24h alone had peak levels which approached the MICs (i.e., approximately 0.5× to 1× the MIC) and reduced bacterial counts by at least 2 log10 CFU/ml at 4 h for all strains. Despite this initial activity, however, there was rapid regrowth which began at 5 h and which reached or exceeded the initial inoculum at 24 h. This may have been the result of declining gentamicin concentrations in the PDM, which were approximately 3 μg/ml at 5 h and <0.3 μg/ml at 12 h. Lastly, a phenomenon more difficult to explain was the lack of bacterial killing following administration of the second doses for the regimen with Gq24h.

The detection of synergy between LY and gentamicin against VRE in our study is consistent with previous results (12). Mercier et al. (12) showed in static time-kill curve experiments that LY plus gentamicin was significantly more potent than LY alone against a VRE strain with resistance to multiple drugs. In our study, LY-gentamicin combination regimens produced statistically significant increases in all pharmacodynamic parameters including KR, BK24, and BK48. Eighty-three percent (10 of 12) of the LY-gentamicin combination regimens were synergistic (i.e., ≥2 log10 decrease in the numbers of CFU per milliliter between the combination and its most active constituent) at both 24 and 48 h. Strain variability was demonstrated by the lack of synergy with the regimens containing LY at 0.1× the MIC against strain 563 (vanB). The concentration dependence of synergy testing was also shown by the presence of synergy with the regimens containing LY at 1× the MIC against the same strain. Finally, the regimens with Gq24h alone were more active than those with Gq8h alone; however, no statistically significant differences between the LY-gentamicin combination regimens containing Gq24h versus those containing Gq8h were detected.

Conclusion.

LY is a new glycopeptide with activity against vancomycin-susceptible and vancomycin-resistant E. faecium. Synergy between LY and gentamicin against vancomycin-susceptible E. faecium and VRE was demonstrated by PDM experiments. The activities of combination regimens containing Gq24h were no different from the traditional regimens containing Gq8h. Strain variability in synergy testing was demonstrated by the consistent lack of synergy with one LY concentration-strain combination. Since our data represent those for only three isolates, all of which demonstrated low-level resistance to gentamicin, studies that include more strains with different susceptibilities to LY and gentamicin are needed. The urgent need for new treatments for VRE further warrants pharmacodynamic investigations of LY alone and in combination with other antibiotics.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported in part by Lilly Canada and Lilly Research Laboratories, Indianapolis, Ind. S. A. Zelenitsky was supported by an Eli Lilly Canada Postdoctoral Fellowship. J. A. Karlowsky is supported by a PMAC-HRF/MRC Postdoctoral Fellowship. G. G. Zhanel is the holder of a Merck Frosst Chair in Pharmaceutical Microbiology.

REFERENCES

- 1.Blaser J. In-vitro model for simultaneous simulation of the serum kinetics of two drugs with different half-lives. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1985;15(Suppl. A):125–130. doi: 10.1093/jac/15.suppl_a.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blaser J. Interactions of antimicrobial combinations in vitro: the relativity of synergism. Scand J Infect Dis. 1991;74(Suppl.):71–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chien J, Allerheligen S, Phillips D, Cerimele B, Thomasson H R. Program and abstracts of the 38th Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1998. Safety and pharmacokinetics of single intravenous doses of LY333328 diphosphate (glycopeptide) in healthy men, abstr. A55; p. 18. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Curbelo D E, Koll B S, Wilets I, Raucher B. Program and abstracts of the 37th Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1997. Treatment and outcome of 100 patients with vancomycin resistant enterococcal (VRE) bacteremia, abstr. J7; p. 289. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Edmond M B, Ober J F, Weinbaum D L, et al. Vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium bacteremia: risk factors for infection. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;20:1126–1133. doi: 10.1093/clinids/20.5.1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garrison M W, Vance-Bryan K, Larson T A, Toscano J P, Rotschafer J C. Assessment of effects of protein binding on daptomycin and vancomycin killing of Staphylococcus aureus by using an in vitro pharmacodynamic model. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1990;34:1925–1931. doi: 10.1128/aac.34.10.1925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gaynes, R., and J. Edwards. 1996. National Nosocomial Infection Surveillance System. Nosocomial vancomycin resistant enterococci (VRE) in the United States, 1989-1995: the first 1000 isolates, abstract 13. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 17(5 pt. 2) (Suppl.):18.

- 8.Iwen P C, Kelly D M, Linder J, Hindrichs S H, Dominguez E A, Rupp M E, Patil K D. Change in prevalence and antibiotic resistance of Enterococcus species isolated from blood cultures over an 8-year period. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:494–495. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.2.494. . (Letter.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jones R N, Barrett M S, Erwin M E. In vitro activity and spectrum of LY333328, a novel glycopeptide derivative. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;41:488–493. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.2.488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Landman D, Quale J M. Management of infections due to resistant enterococci: a review of therapeutic options. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1997;40:161–170. doi: 10.1093/jac/40.2.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leclerque R, Courvalin P. Resistance to glycopeptides in enterococci. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;24:545–556. doi: 10.1093/clind/24.4.545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mercier R-C, Houlihan H H, Rybak M J. Pharmacodynamic evaluation of a new glycopeptide, LY333328, and in vitro activity against Staphylococcus aureus and Enterococcus faecium. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:1307–1312. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.6.1307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Approved standard. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically. Wayne, Pa: National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nicas T L, Mullen D L, Flokowitsch J E, Preston D A, Snyder N J, Stratford R E, Cooper R D G. Activities of the semisynthetic glycopeptide LY191145 against vancomycin-resistant enterococci and other gram-positive bacteria. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:2585–2587. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.11.2585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nicas T L, Mullen D L, Flokowitsch J E, Preston D A, Snyder N J, Zweifel S C, Wilkie S C, Rodreguez M J, Thompson R C, Cooper R D G. Semisynthetic glycopeptide antibiotics derived from LY264826 active against vancomycin-resistant enterococci. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:2194–2199. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.9.2194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schwalbe R S, McIntosh A A, Qaiyumi S, Johnson J A, Johnson R J, Furness K M, Holloway W J, Steele-Moore L. In vitro activity of LY333328, an investigational glycopeptide antibiotic, against enterococci and staphylococci. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:2416–2419. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.10.2416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stratton C W. Bactericidal testing. Infect Dis Clin N Am. 1993;7:445–459. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vergis E N, Chow J W, Haydn M K, Snydman D R, Zervos M J, Linden P K, Wagener M M, Muder R R. Program and abstracts of the 37th Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1997. Vancomycin resistance predicts mortality in enterococcal bacteremia: a prospective, multicenter study of 375 patients, abstr. J6; p. 289. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Woodford N, Johnson A P, Morrison D, Speller D C E. Current perspectives on glycopeptide resistance. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1995;8:585–615. doi: 10.1128/cmr.8.4.585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zelenitsky S A, Karlowsky J A, Zhanel G G, Hoban D J, Nicas T. Program and abstracts of the 20th International Congress of Chemotherapy. 1997. Synergistic activity of an investigational glycopeptide, LY333328, and gentamicin against vancomycin-sensitive and vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium, abstr. 4296; p. 150. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zelenitsky S A, Karlowsky J A, Zhanel G G, Hoban D J, Nicas T. Time-kill curves for a semisynthetic glycopeptide, LY333328, against vancomycin-susceptible and vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium strains. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:1407–1408. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.6.1407. . (Letter.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]