Abstract

Objectives:

To explore effects of the brain renin-angiotensin system (RAS) on cognition.

Design:

Systematic review of experimental (non-human) studies assessing cognitive effects of RAS peptides angiotensin-(3–8) [Ang IV] and angiotensin-(1–7) [Ang-(1–7)] and their receptors, the Ang IV receptor (AT4R) and the Mas receptor.

Results:

Of 450 articles identified, 32 met inclusion criteria. Seven of 11 studies of normal animals found Ang IV had beneficial effects on tests of passive or conditioned avoidance and object recognition. In models of cognitive deficit, eight of nine studies found Ang IV and its analogs (Nle1-Ang IV, dihexa, LVV-hemorphin-7) improved performance on spatial working memory and passive avoidance tasks. Two of three studies examining Ang-(1–7) found it benefited memory. Mas receptor removal was associated with reduced fear memory in one study.

Conclusion:

Studies of cognitive impairment show salutary effects of acute administration of Ang IV and its analogs, as well as AT4R activation. Brain RAS peptides appear most effective administered intracerebroventricularly, close to the time of learning acquisition or retention testing. Ang-(1–7) shows anti-dementia qualities.

Keywords: Renin-angiotensin system, angiotensin IV, angiotensin-(1–7), AT4R, Alzheimer’s disease, cognition

1. Introduction

The renin-angiotensin system (RAS) is instrumental in the maintenance of cardiovascular function and fluid homeostasis in peripheral circulation, and represents one of the most thoroughly investigated enzyme-neuropeptide systems. While commonly associated with vascular-renal functions, pharmacological and genetic research studies have also established the presence of a paracrine RAS within the central nervous system (CNS) which consists of identical components and which acts largely independently of peripheral function (Wright & Harding, 1994). The RAS in the brain is believed to be involved in processes beyond mere hydroelectrolytic homeostatic control; it has been implicated in processes of learning and memory, neuronal differentiation, and nerve regeneration (Llorens and Mendelsohn, 2002), as well as in the pathophysiology of various diseases. Dysregulation in the brain RAS has been reported in studies of patients with Alzheimer’s disease (AD), Parkinson’s disease, and X-linked intellectual disability (Wright & Harding, 2010; Allen et al., 1992; Vervoort et al., 2002).

At the same time, the activation of various recently discovered RAS constituents, such as angiotensin-(1–7) [Ang-(1–7)] and angiotensin-(3–8) [Ang IV], has been linked to neuroprotective effects, observed in animal models of cerebral injury. For example, the hexapeptide Ang IV [Val1-Tyr2-Ile3-His4-Pro5-Phe6 (VYIHPF)] and its various analogs have been found to exert anticonvulsant effects in animal models of epilepsy (Tchekalarova, Kambourova, & Georgiev, 2001; Stragier et al., 2006), protect against cerebral ischemia (Faure et al., 2006a, 2006b, 2008), improve endothelial function in animal models of atherosclerosis (Vinh et al., 2007) and enhance long term potentiation in vitro and in vivo (Kramár et al., 2001, Wayner et al., 2001). Consistent with what would be expected given these results, autoradiography studies have localized binding sites for Ang IV in areas of the brain which are crucial for cognitive processes, including the hippocampus, neocortex, and basal nucleus of Meynert (Chai et al., 2000; Harding et al., 1992; Wright & Harding, 2008).

Ang IV is an endogenous peptide, formed from the degradation of angiotensin II (Ang II). Unlike its parent peptide, the actions of Ang IV and its analogs do not appear to be mediated by either of the Ang II receptors, the type 1 (AT1R) or type 2 receptor (AT2R). Its biological effects are not blocked by classic AT1R and AT2R antagonists losartan and PD123177 (Demaegdt et al., 2004). These findings suggest that the beneficial effects of Ang IV are moderated by a different receptor, which has been termed AT4R (De Gasparo, Catt, Inagami, Wright & Unger, 2000). The development of Ang IV analogs and AT4R ligands as therapeutic interventions has been hindered due to their low blood-brain barrier permeability and metabolic instability, as well as a lack of clarity surrounding the mechanisms by which they exert their effects. Studies have attempted to find smaller molecular derivatives of Ang IV (e.g. the pentapeptide, des-Phe6-Ang IV) which, due to their size, may be more efficacious as drugs; the challenge has been determining whether or not these derivatives confer the same cognitive-enhancing and neuroprotective effects (Benoist et al., 2011). Another derivative that has received increasing attention is Nle-Tyr-Ile-His-Pro-Phe (Nle1-Ang IV), an Ang IV-analog which competes more effectively than native Ang IV for binding sites (Sardinia et al., 1993).

Efforts have been made to decrease the hydrogen bonding potential and to increase the hydrophobicity and metabolic stability of such analogs. Structural modifications of Nle1-Ang IV at the N- and C-terminals has yielded the metabolically stabilized and orally active Nle1-Ang IV derivative, N-hexanoic-tyrosine-isoleucine-(6) aminohexanoic amide (dihexa). Separate from Ang IV analogs, but in a related vein, research has attempted to develop other AT4R ligands, such as LVV-hemorphin-7 [Leu-Val-Val-Tyr-Pro-Trp-Thr-Gln-Arg-Tyr (LVV-H7)]. LVV-H7 is a decapeptide which, although structurally distinct from Ang IV, exhibits similar effects as Ang IV in in vitro assays, such as promoting cellular proliferation (Mustafa, Chai, Mendelsohn, Moeller, & Albiston, 2001) and facilitating K+-evoked acetylcholine (ACh) release in hippocampal slices (Lee, Chai, Mendelsohn, Morris, & Allen, 2001).

Besides Ang IV, Ang-(1–7) represents another metabolite of Ang II which has been the subject of increasing study for its potential therapeutic effects. Ang-(1–7) is a vasodilator peptide which limits the pressor, angiogenic, and proliferative actions of Ang II (Iusuf, Henning, van Gilst, & Roks, 2008). Upon binding to its Mas receptor, Ang-(1–7) elicits the release of prostanoids and nitric oxide (NO; Santos, Campagnole-Santos, & Andrade, 2000), which are crucial intercellular messengers in long term potentiation and memory (Medina and Izquierdo, 1995; Ramakers and Storm, 2002; Shaw et al., 2003). In a study of focal cerebral ischemia, intracerebroventricular (i.c.v.) infusion of Ang-(1–7) in rats significantly increased the density of brain capillaries, improved regional cerebral blood flow, and decreased infarct volume and neurological deficits following permanent middle cerebral artery occlusion (Jiang et al., 2014). In another study, i.c.v. infusion of Ang-(1–7) in hypertensive rats inhibited effects of autophagy (Jiang et al., 2013), a cellular process increased in conditions of stress which regulates the lysosomal degradation of damaged organelles (Shintani & Kionsky, 2004). In these studies, neuroprotective effects were abolished or attenuated by A-779, an antagonist of the Ang-(1–7) receptor, Mas, highlighting the importance of the Ang-(1–7)-Mas axis.

While the brain RAS has effects on a myriad of processes, including angiogenesis, cardiovascular and renal functioning, this review will focus on its effects on cognition. The present review builds upon the literature by critically reviewing the evidence for the procognitive qualities of Ang IV and Ang-(1–7), their receptors (AT4R and Mas), as well as Ang IV analogs (e.g. des-Phe6-Ang IV), metabolically stabilized derivatives (e.g. Nle1-Ang IV, dihexa) and other AT4R ligands (e,g. LVV-H7). We examine studies of experimental models of normal animals as well as animals with induced cognitive impairment. In the latter studies, cognitive impairment is induced by pharmacological blockade of central muscarinic acetylcholine (ACh) receptors with scopolamine hydrobromide (scopolamine), which leads to dysfunction in memory which mimics impairment observed in patients with AD in its early to middle stages (Fisher et al., 2003). Increasing attention has also been paid to the role of central nicotinic ACh receptors in the pathophysiology of AD, given the reduced nicotinic binding observed in AD patients in areas such as the hippocampus and neocortex (Kellar, Whitehouse, Martino-Barrows, Marcus & Price, 1987; Perry et al., 1987; Schroder, Giacobini, Struble, Ziles & Maelicke, 1991; Whitehouse et al., 1986). Blockade of central nicotinic ACh receptors with mecamylamine has been found to impair both humans and animals on cognitive tasks (Olson et al., 2004). Studies of the cognitive effects of the RAS peptides and receptors, in models of impairment induced by the blockade of these two receptor types, are thus included.

A related line of work involves elucidating the mechanism behind the effects of these RAS peptides and receptors. Mechanisms that have been proposed include (1) modulation by voltage-gated calcium channels (VGCCs), given findings that Ang IV induces long term potentiation (LTP) through VGCC-dependent Ca2+ neuronal influx (Davis et al., 2006); (2) the activation of PKMzeta, a fragment of the protein kinase cZeta, which is linked to the maintenance of hippocampal LTP and various types of memory (Serrano et al., 2005, 2008; Pastalkova et al, 2006); and (3) mediation by the dopaminergic system, given that doses of Ang IV which improve learning in rats have also been found to increase stereotype behavior produced by dopaminergic agonists (Braszko et al., 1988), effects which are reliant on the activation of D1 and D2 dopamine receptors (Braun & Chase, 1986). Increases in dopaminergic neurotransmission following intracerebral administration of Ang-(1–7) (Braszko, Holy, Kupryszewski, & Witczuk, 1991; Pawlak et al., 2001), which may be mediated by the action of Ang IV or its derivative des-Phe6-Ang IV (Møeller, Allen, Chai, Zhuo & Mendelsohn, 1998), have also been reported. Therefore, the cognitive effects of acute administration of Ang IV, Ang-(1–7), AT4R-ligands or their analogs in studies modulating proposed mechanistic pathways (e.g. VGCCs, PKMzeta, the dopaminergic system, the cholinergic system) will also be reviewed.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Identification

Experimental (non-human) studies assessing the effects of Ang IV, Ang-(1–7), AT4R, the Mas receptor, and their related agonists and antagonists in models of Alzheimer’s disease, induced memory impairment, as well as no prior impairment were identified from Medline (PubMed), Web of Science, and Embase (Ovid), by searching for all published articles up to the end of July 2017. No date limit was placed on the search. The search was performed on May 24, 2017 and updated on July 31, 2017. Search keywords included angiotensin and rat or mouse or rodent and one of the following: cerebral, cognition, cognitive, dementia, or Alzheimer’s. Further literature searches were conducted by substituting the general term angiotensin for the common abbreviations Ang IV, Ang-(1–7), AT4R and Mas. Searches were also conducted using search terms for large-animal models (e.g. cats, rabbits, primates); however, these returned no results. Bibliographies of eligible articles and reviews were further searched manually for additional references. Unpublished studies were not included given the lack of peer review and the difficulty in assessing internal validity due to poor reporting.

2.2. Selection Criteria

Records were reviewed using the inclusion criteria of: (1) experimental Alzheimer’s disease state or cognitive impairment was induced; (2) one of the angiotensin peptides or its analogs were exogenously applied, or one of the angiotensin receptors was genetically or pharmacologically manipulated or up- or down-regulated by an agonist or antagonist; (3) no other potential neuroprotective agents were additionally administered (i.e. confounded), unless they were proposed to mediate the effects of RAS; (4) assessments of cognition were performed; and (5) there was a control group. A study was included even if criterion (1) was not met (i.e., no impairment was induced) only if it met the second criterion, i.e. there was a manipulation of one of the peptides or receptors under study. Literature reviews, conference abstracts, editorials, correspondence, commentaries, case reports, and case series were excluded. Studies which primarily assessed effects of the relevant angiotensin peptides or receptors but which did not consider cognitive outcomes were excluded.

One investigator (JKH) manually reviewed record titles and abstracts using broad inclusion and exclusion criteria. If an article passed this first-level screening, the second-level screening involved a full-text review.

2.3. Methodological Quality Review

Following the systematic search, the methodological quality of each study was determined using an eight-point scale adapted from the Stroke Therapy Academic Industry Roundtable (STAIR) criteria for standards regarding preclinical neuroprotective and restorative drug development (STAIR, 1999). One point was given for evidence of each of the following: (1) presence of randomization, (2) monitoring of physiological parameters of the animals (not solely maintenance of experimental conditions), (3) evaluation of dose-response relationship, (4) assessment of optimal time window, (5) blinded measurement of outcomes, (6) measurement of outcomes during the acute phase, i.e. days 1–3, (7) measurement of outcome long-term, i.e. days 7–30, and (8) assessment of at least one other brain outcome in addition to cognition, e.g. neuropathology. Study scores can be found in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of study quality on an eight-point scale adapted from Stroke Therapy Academic Industry Roundtable (STAIR) criteria for standards regarding preclinical neuroprotective and restorative drug development (STAIR, 1999).

Used Mas knockout mice; criteria 3 and 4 (assessment of dose-response relationship and optimal time window of exogenous manipulation) did not apply.

2.4. Analysis

For assessment of studies examining Ang IV/AT4R, data were grouped for qualitative analysis by model type: (i) normal animals; (ii) animals with induced cognitive impairment; (iii) animals in which both the RAS and another agent proposed to mediate the RAS were manipulated. Given that there were only four studies examining Ang-(1–7)-Mas effects on cognition, these were assessed together. Meta-analysis was not undertaken given the heterogeneity in study designs in terms of timing (pre-/post-training; pre-/post-testing) and route of administration [intracerebroventricular (i.c.v.), intrahippocampal (i.h.), subcutaneous (s.c.), intraperitoneal (i.p.), oral] of RAS peptides, species (mice vs. rats) and strain (e.g. Wistar vs. Sprague Dawley rats) differences, as well as amounts of the peptide administered and the cognitive tests used. Qualitative review was undertaken to critically appraise and summarize empirical evidence from these disparate studies, in order to identify the most effective RAS peptides or agents as well as routes and timings of administration.

2.5. Cognitive Tests Used in Studies

Cognitive ability is assessed in animal models through behavioral testing. The most common tests include the Morris Water Maze (MWM; Morris, 1984), the Barnes circular maze (Barnes, 1979), and the Spatial Win-Shift (SWSh) task in the Radial Arm Maze (Olton & Samuelson, 1976), all of which evaluate spatial working memory. Fear-, cued-, and contextual-memory are assessed in various conditioning tasks that measure the amount of conditioned responses elicited, freezing behavior, or the time to extinction of a learned response.

2.5.1. Spatial Memory Tasks

Morris Water Maze.

In the MWM task, a black circular tank is filled with water and a black circular platform is placed a distance away from the edges of the tank, submerged below water. Location of the platform is randomly assigned to one of the four quadrants of the tank (NW, NE, SW, SE) and three of the walls are covered with different posters acting as spatial cues. Measures from this test include (1) total swim latency to the platform, (2) swim distance, (3) swim speed, and (4) swim efficiency (calculated by dividing the swim distance by the shortest path from entry to the platform). Acquisition trials (typically five per day for eight consecutive days) permit the animal to swim until the platform is found, or for 120 seconds. Another trial beings following a 30 second rest period. A probe trial consists of removing the platform and the animal swimming the entire 120 seconds to demonstrate the persistence of a learned response.

Measures during probe trials include (1) total time spent in the target quadrant where the platform had been during acquisition trials as well as (2) the number of crossings over the original location of the platform. In a modified version of the MWM task (Pederson, Krishnan, Harding & Wright, 2001), pretraining trials were introduced which consisted of training the animals to escape water by climbing onto a visible platform. This ensured that animals learned a successful escape strategy prior to acquisition trials.

Barnes Circular Maze.

This task utilizes a white, circular platform which contains 18 holes evenly spaced around the circumference. A removable box underneath one of the holes represents an escape tunnel. This box remains in one location, marked by spatial cues, for each rat. There are eight spatial cues on the floor below the platform which are visible from the surface of the maze. The rat is placed in the center of the platform at the start of each trial. Aversive stimuli comprising floodlights as well as an auditory buzzer are utilized in order to provide incentive for the rat to enter the escape tunnel. Acquisition trials (typically three per day for ten days) include 5 minute intervals between trials.

Measures from this test include (1) the numbers of errors made, defined as the lowering of the rat’s head into the wrong hole, (2) the distance traveled, defined as the number of holes probed, and (3) the time taken (latency) to locate the tunnel. Spatial learning performance can be calculated by taking the mean number of errors made and the mean distance travelled for each daily block.

Radial Arm Maze.

The Spatial Win-Shift (SWSh) task utilizes a maze consisting of an octagonal center platform with 8 arms extending from the center. Each arm contains a food dish at the end of the arm. Large, colored shapes on 3 out of 4 of the room walls serve as spatial cues. During habituation sessions, food is scattered all throughout the maze (center, arms, and food dishes) and animals are allowed to freely explore and consume food. During training sessions, food is placed in all 8 arms and 4 arms are blocked. The blocked arms change daily but rats share the same combination each day. Training ends when all 4 open arms are entered or 5 minutes have elapsed. After a 5 minute break, animals are returned to the maze for testing. During testing, the arms which were previously blocked are opened and baited. Rats must remember which arms were previously blocked and enter them to obtain the food reward.

Measures include (1) across-phase errors, which consist of initial entry to an arm entered during the training phase, (2) within-phase errors, which consist of reentry into an arm previously entered during the testing phase, (3) latency to reach the food dish of the first arm visited, (4) time taken to complete the testing phase, and (5) number of correct choices made in sequence before the first error in each session.

Plus Maze.

The plus maze (De Bundel et al., 2009) consists of four closed arms (in the shape of cross) with black walls and visual cues located around the arms. Spontaneous alternation testing is conducted by placing animals in the center of the maze and allowing free exploration for 20 minutes. The number and sequence of arm entries are recorded. An alternation score is counted when a rat visits four different arms for every five consecutive arm entries. Higher scores indicate better spatial working memory for arms which have already been explored.

2.5.2. Fear Memory Tasks

Inhibitory Avoidance task (Step-down task).

A one-trial inhibitory avoidance paradigm (IA) is a hippocampal-dependent learning task in which stepping down from a platform is associated with a footshock, leading to an increase in step-down latency (Bevilaqua et al., 2003). Memory retention is evaluated in a session 24 hours following training. A second retention test may be carried out another 24 hours later. The time taken to step-down is taken as an indicator of memory retention.

Passive Avoidance task (Step-through task).

Similar to the IA task, passive avoidance (PA) behavior is measured in a one-trial learning situation (Ader, Weijnen & Moleman, 1972). This trial utilizes the natural preference of rats for dark environments. After habituation to a dark compartment, rats are placed on an illuminated platform and allowed to enter the dark compartment. After three such trials, a footshock is delivered in the dark compartment (learning trial). Retention is tested 24 hours later by placing the animal on the platform. The time taken to re-enter the dark compartment is taken as an indicator of recall of the passive avoidance response.

Conditioned Avoidance task.

Conditioned avoidance responses (CARs) are studied in a box divided into two equal parts by a wall with a opening in its center (Braszko, 2004). A buzzer (conditioned stimulus, CS) is sounded for 3 seconds. If a rat does not make a positive (+) CAR by moving into the other compartment, an electronic shock (unconditioned stimulus, US) is delivered through the floor of the box until the animal moves to the other side. Acquisition training consists of five daily 20-trial sessions. Measurements include the number of (+) CARs (avoidance responses), calculated as a percentage of the total number of trials.

Auditory Fear Conditioning task.

In this task, animals are introduced to a conditioning chamber which consists of a soundproof box with black walls. During conditioning, animals are first habituated to the chamber for 120 seconds before a tone (CS) is delivered for 30 seconds. The last 2 seconds are paired with a footshock (US). This is the 1CS/US protocol. After a 30 second interval, the animal is removed and returned to its home cage. During the testing phase 24 hours later, the animal is returned to the conditioning chamber and freezing behavior (complete lack of movement, except for respiration) is measured over a period of 5 minutes, recorded for 2 in every 5 seconds (Radwanska et al., 2011). After a 3 hour interval, the animal is put into another same-sized chamber with black and white walls and a unique smell for 180 seconds. Following this, the same tone used during conditioning is presented for another 180 seconds. The presentation of this tone is conducted for two consecutive days, once a day. Freezing is recorded for the entire period as a measure of cued-fear memory.

Contextual Fear Conditioning task.

This task uses the same chamber as the Auditory Fear Conditioning task and either the same 1CS/US habituation protocol or a 3CS/US protocol which consists of two additional shocks with a 90 second interval between them. During the testing phase 24 hours later, the animal is returned to the conditioning chamber and freezing behavior is measured over a period of 10 minutes, recorded for 2 in every 5 seconds (Radwanska et al., 2011). Memory extinction is assessed by exposure to the conditioning chamber for 10 minutes, once a day, for 3 or 5 consecutive days.

2.5.3. Object Recognition.

During this test, animals are placed are placed in a box along with glass or porcelain objects that have no natural significance to the rats (Ennaceur & Meliani, 1992). During two habituation sessions, animals are allowed 3 min to explore the apparatus. The testing session occurs 24 hours following habituation and comprises two trials. In Trial 1, rats are exposed to two identical objects, A1 and A2. Sixty minutes later, in Trial 2, rats are exposed to two objects, one identical to the familiar object, A’, and a new object, B. Measures include (1) time spent exploring objects during Trials 1 and 2, (2) object recognition, calculated as time spent exploring object B minus time spent exploring object A’, (3) total exploration in Trial 2, calculated as time spent exploring both objects A’ and B. In a modified form of this test (Chow et al., 2015), the interval between trials is increased from 1 hour to 1 day. In another adaptation, the objects A1 and A2 are present during the two initial habituation sessions, and during the testing session 24 hours later, one of these objects is present along with a new object B (Gard et al., 2007; Golding et al., 2010).

3. Results

3.1. Methodological Quality

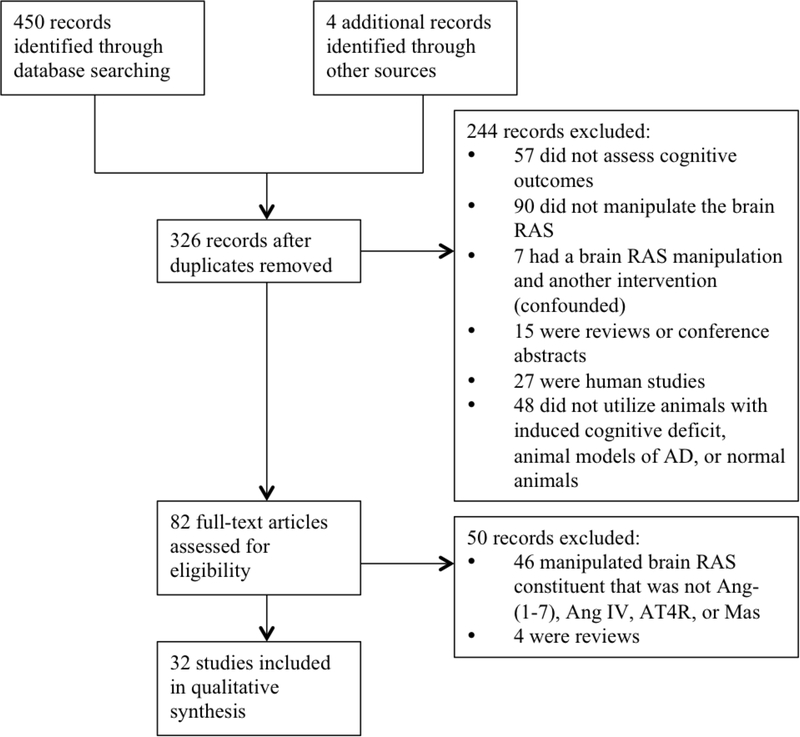

Four hundred and fifty citations were identified in the initial search. As shown in Figure 1, of the 450 citations, 82 underwent full-text review. After application of the full inclusion and exclusion criteria, 32 articles remained. Twenty-nine articles assessed effects of Ang IV and its analogs or AT4R and its agonists or antagonists, and four studies evaluated Ang-(1–7) or its Mas receptor. One study (Bonini et al., 2006) examined both Ang IV and Ang-(1–7). Of the 32 included publications, 27 studied rats, and 5 studied mice.

Figure 1. Summary of study identification process.

AD, Alzheimer’s disease; Ang-(1–7), angiotensin-(1–7); Ang IV, angiotensin IV; AT4R, Ang IV receptor; RAS, Renin-Angiotensin System

The assessment process revealed a number of factors which may have affected study quality. First, no studies described monitoring of physiological parameters (e.g. heart rate) of the animals, though every study noted standardization of living conditions and ensuring animals had habituated to the experimenters and their environment prior to testing. Only four studies (13%) described blinded measurement of outcomes and twenty-one studies (66%) described randomization.

Seventeen studies (53%) evaluated a dose-response relationship and four studies (13%) assessed for optimal time window of exogenous manipulation of the RAS peptide or receptor. All studies assessed cognition during days 1–3 following treatment, and 17 studies (53%) measured longer-term cognition during days 7–30. Five studies (16%) assessed outcomes between days 4–6, and nine studies (28%) did not report further measurement of cognition beyond day 1. Nine studies (28%) assessed a separate neurological outcome (e.g. effects on spinogenesis or excitatory post-synaptic potentials) distinct from visuomotor ability, emotionality, or thirst of the animals.

The range of STAIR scores was 2–5 (mean and modal score = 3), with the exclusion of one study (Lazaroni, Bastos, Moraes, Santos & Pereira, 2015), which used Mas knock-out mice and for which criteria 3 and 4 (dose-response relationship and optimal time window of exogenous manipulation) did not apply. Five studies received a STAIR score of 2, fourteen studies a score of 3, nine studies a score of 4, and three studies a score of 5.

3.2. Effects of Ang IV/AT4R in normal animals

As shown in Table 2, sixteen studies examined effects of the Ang IV-AT4R axis in normal animals. Control animals in these studies received injections of artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF) or saline.

Table 2.

Characteristics of studies utilizing normal animals, without induced cognitive impairment.

| Study | Test used | Peptide / compound exogenously applied | Effect on performance | Dose | First dose timing | Route | Species | STAIR score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bonini et al (2006) | IA | Ang IV | – | 0.5µg/side each | 15 min before testing | i.h. | Male WR | 2 |

| Ang 1–7 | – | |||||||

| Braszko, Kupryszewski, Witzcuk & Wisniewski (1988) | PA CA |

Ang IV | ↑ | 1 nmol | 15 min before training (CA) and testing (PA) | i.c.v. | Male WR | 2 |

| Braszko et al (2006) | PA OR |

Ang II | ↑ | 1 nmol | 5, 10, 15 min before testing | i.c.v. | Male WR | 3 |

| Ang IV | ↑ | 1 nmol | ||||||

| De Bundel et al (2009) | Plus maze | Ang IV | ↑ | 1 or 10 nmol Ang IV | 5 min before testing | i.c.v. | Male SDR | 4 |

| LVV-H7 | 0.1 or 1 nmol LVV-H7 | |||||||

| Gard, Daw, Mashour, & Tran (2007) | Adapted OR task | Ang IV | – | 0.50 mg/kg−1 | Immediately post training | s.c. | Female WR | 4 |

| Oxytocin | – | 0.25 mg/kg−1 | ||||||

| Ang IV + Oxytocin | – | Same doses above | ||||||

| Golding et al (2010) | Adapted OR task | Ang IV | ↑ in C57BL/6 and DBA2 mice – in CD mice |

4.7, 47, 470 µg/kg in 10ml/kg to reflect rat dosage | Immediately post training | s.c. | Male CD, DBA2, C57BL/6 mice | 3 |

| Holownia & Braszko (2003) | Adapted MWM task | Ang IV | – | 1 nmol | 15 min before training | i.c.v. | Male WR | 3 |

| Kerr (2004) | PA | Ang IV | – | 0.5 µg/side | 30, 90, 180 min after training | i.h. | Male WR | 3 |

| Ang II | ↓ | 0.01, 0.05, 0.1 or 0.5 µg/side | ||||||

| Lee et al (2004) | Barnes Circular Maze | Nle1-Ang IV | ↑ | 100 pmol or 1 nmol | 5 min before testing | i.c.v. | Male SDR | 4 |

| LVV-H7 | ↑ | 100 pmol or 1 nmol | ||||||

| Nle1-Ang IV + Divalinal | – | 100 pmol Nle1-Ang IV + 10 nmol Divalinal | ||||||

| Divalinal | – | 10 nmol | ||||||

| Olson et al (2004) | Expt 1: MWM | Mecamylamine | ↓ | 0.5, 1.0 µmol | 15 min before testing | i.c.v. | Male SDR | 4 |

| Paris et al (2013) | Expt 2: Truncated OR task | Ang IV | ↑ at 0.1, 1.0, or 10 | Ang IV: 0.01, 0.1, 1, 10 nmol | 10, 20, 30 min before testing | i.c.v. | Male C57BL/6J mice | 3 |

| Expt 3: Standard and truncated OR task | Ang IV | ↑ | 0.1 nmol | 30 min before testing | i.c.v. | Male C57BL/6J mice | ||

| Divalinal | ↓ | 20 nmol | ||||||

| Expt 4: Truncated OR task | Ang IV | ↑ | 0.1 nmol | 10 min before testing | i.c.v. | Male C57BL/6J mice | ||

| Y2A I3A P5A |

↑ | 0.1 nmol | ||||||

| V1A H4A F6A |

– | 0.1 nmol | ||||||

| Tchekalarova et al (2001) | PA | Ang IV | ↑ at 0.1, 0.5 µg/rat | 0.01, 0.1, 0.5, 1.0 µg/rat | Immediately after training | i.c.v. | Male WR | 3 |

| Ang IV + Sarilesin | ↓ | 0.1 µg Ang IV + 1µg Sarilesin | Immediately after training | i.c.v. | ||||

| Ang IV + Theophylline | ↑ | 0.01 µg Ang IV + 75 mg/kg Theophylline | Immediately after training | i.p. | ||||

| Ang IV + CPA | ↓ | 0.1 mg/kg | Immediately after training | i.p. | ||||

| Wilson et al (2009) | Expt 1: MWM | Divalinal | ↓ | 10 nmol | 15 min before training | Intra-NBM | Male SDR | 4 |

| Scopolamine | ↓ | 17.5 nmol | ||||||

| Mecamylamine | ↓ | 0.3 µg | ||||||

| Expt 2: MWM | Nicotine + Divalinal | ↑ | 1 µg nicotine + 10 nmol Divalinal | 5 min before training | Intra-NBM | Male SDR | ||

| Divalinal | ↓ | 10 nmol | ||||||

| Expt 3: MWM | Carbachol | – | 0.25, 0.5 µg | 5 min before training | Intra-NBM | Male SDR | ||

| Expt 4: MWM | Carbachol | ↓ | 0.1 µg, 0.5 µg |

15 min before training | Intra-NBM | Male SDR | ||

| Wright et al (1993) | PA | Ang IV | ↑ 100 pmol, 1nmol | 10 pmol, 100 pmol, 1 nmol | 5 min before testing | i.c.v. | Male SDR | 4 |

| Ang II | – | 1 nmol | ||||||

| Wright et al (1996) | PA | Ang IV | ↑ | 1 nmol | 24 hours before testing | i.c.v. | Male WR | 5 |

| Wright et al (1999) | MWM | Nle1-Ang IV | ↑ | 0, 0.1, 0.5 nmol/hr | Not reported | i.c.v. | Male SDR | 4 |

| AngII(4–8) | – | 0.5 nmol/hr | ||||||

| Divalinal | ↓ | 0, 0.5, 5.0 nmol/hr |

Tests used: CA, Conditioned Avoidance; IA, Inhibitory avoidance; MWM, Morris Water Maze; OR, Object recognition; PA, passive avoidance

Peptides/compounds applied: Ang II, Angiotensin II; Ang IV, Angiotensin IV; Divalinal, Divalinal-AngIV; LVV-H7, LVV-hemoprhin-H7; Nle1-AngIV, Norleucine1-Ang IV

Effects: ↑, improves test performance; ↓, worsens test performance, –, has no effect on performance

Routes of administration: i.c.v., intracerebroventricular; i.p., intraperitoneal; i.h., intrahippocampal; intra-NBM, intranucleus basalis magnocellularis; s.c., subcutaneous

Species: SDR, Sprague Dawley Rats; WR, Wistar Rats

3.2.1. Studies of spatial working memory.

Four of the five studies assessing spatial working memory found beneficial effects of administration of Ang IV or its ligands or AT4R agonists. Only one study (Holownia & Braszko, 2003) found no effect of Ang IV on the rate of acquisition of the task.

Of the remaining four studies, the first study (De Bundel et al., 2009) found that i.c.v. treatment with either Ang IV or LVV-H7 improved performance on a plus maze task relative to vehicle controls, with peptide-treated animals showing increased alternation scores. Similarly, the second study by Lee et al. (2004) reported that i.c.v. treatment with Nle1-Ang IV or LVV-H7 was associated with significantly fewer errors, shorter distance traveled, and reduced latency in finding the escape tunnel, compared to the controls, with differences observed in the first two measures as early as the first day of testing. The beneficial effects of Nle1-Ang IV were attenuated by co-administration of the AT4 receptor antagonist, divalinal-Ang IV.

The third study (Wilson, Munn, Ross, Harding & Wright, 2009) found that rats treated with divalinal-Ang IV delivered directly to the nucleus basalis magnocellularis (NBM) took significantly longer to find the hidden platform compared to vehicle controls and performed at levels similar to rats treated with scopolamine or mecamylamine alone. However, rats pre-treated with nicotine did not show these impairment effects of divalinal-Ang IV, and were no different from the vehicle control group, showing that the nicotinic agonist reversed divalinal-Ang IV impairment. Notably, carbachol, a muscarinic agonist, was not able to do the same, as carbachol + divalinal-Ang IV treated rats did not differ from the divalinal-Ang IV group. Treatment with carbachol alone was associated with longer latency to find the pedestal on the last day of training.

Consistent with all these results, the fourth study (Wright et al., 1999) found that Nle1-Ang IV treatment improved the rate of acquisition on the MWM, reduced the latency to find the pedestal and decreased swim distance, compared to controls and rats treated with Ang-(4–8), a pentapeptide which also binds to AT4R, though with low affinity. These differences were seen over the first 2 days of acquisition and by day six, the performance of all animals were equivalent. Over days 9–11, the Ang-(4–8) group showed slightly poorer performance than the other groups. Groups treated with divalinal-Ang IV showed similar impairment effects as observed in the Wilson et al. (2009) study, requiring longer latencies to find the platform and showing a much slower rate of improvement of acquisition performance, compared to aCSF controls, over days 4–6, and a longer swim distance compared to controls on day 13.

3.2.2. Studies of object recognition.

Three of four studies measuring object recognition found beneficial effects of Ang IV or Ang IV-analog treatment. Braszko, Walesiuk, & Wieglat (2006) found that i.c.v. treatment of Ang IV was associated with better object recognition memory, whether given 5, 10, or 15 minutes prior to testing. Similarly, Golding et al. (2010) found improvement in object recognition following subcutaneous administration of Ang IV, with a significant dose x strain interaction, with different strains of mice responding differently to increasing Ang IV doses. Ang IV enhanced recall at 4.7 μg/kg and 47 μg/kg in DBA2 mice, while C57 strain mice only showed improvement at 4.7 μg/kg, and CD mice showed no improvement at either dose.

Paris et al. (2013) also found beneficial effects of i.c.v.-administered Ang IV. Doses of 0.1, 1.0, and 10.0 nmol, but not 0.01 nmol, increased the percentage of time that mice spent exploring the novel object in a truncated version of the task. There was a stepwise decrease in object recognition performance when 0.1 nmol of Ang IV was administered 10 min vs. 20 min vs. 30 min prior to testing, with the mice receiving Ang IV 10 min prior to the test performing significantly better than saline controls and mice receiving Ang IV 30 min prior to testing. Mice receiving Ang IV 20 min before testing also performed better than saline controls, though to a lesser degree.

In additional experiments, Paris et al. (2013) found impairment effects of divalinal-Ang IV-treated mice, which did not show the same level of object recognition as saline controls, although they increased the percentage of time spent exploring the novel object in a standard version of the task. In a truncated form of the test, 0.1 nmol of Ang IV increased this percentage, an effect not seen in the other saline, divalinal-Ang IV, and Ang IV + divalinal-Ang IV groups.

Paris et al. (2013) also investigated the effects of substituting alamine for valine1, tyrosine2, isoleucine3, histidine4, proline5, or phenylalanine6 in Ang IV (yielding V1A, Y2A, I3A, H4A, P5A, and F6A, respectively). Substitution with valine1, histidine4, or phenylalanine6 abolished the beneficial effects of Ang IV, while compounds that had alanine replacement with tyrosine2, isoleucine3 or proline5 showed improved performance on the object recognition task. However, in the last phase of the task, only Ang IV significantly enhanced the percentage of time spent with the novel object relative to saline controls, which was improvement that was greater than that observed by its V1A, I3A, H4A, and F6A analogs.

In contrast to these reports of procognitive effects of Ang IV and a number of its analogs, Gard, Daw, Mashour, & Tran (2007) reported that neither Ang IV nor oxytocin, delivered subcutaneously alone or in combination, had any effects on object recognition performance in a modified version of the test. However, this is somewhat unsurprising given that these peptides are rapidly degraded by peptidases which are abundantly expressed in circulation, and would have little chance of getting into the cortex being delivered subcutaneously.

3.2.3. Studies of inhibitory or passive avoidance.

Five of seven studies found Ang IV to improve performance on tasks of inhibitory or passive avoidance, while two studies found no effect. One study which used the inhibitory avoidance task (Bonini et al., 2006) examined the effects of i.h. administration of Ang IV, Ang-(1–7), and Ang II. Neither Ang IV nor Ang-(1–7) had any effect on task performance, whether memory was tested 24 or 48 hours after training, while Ang II produced a dose-dependent and reversible amnesia on testing. Similarly, Kerr et al (2004) found that that rats which had received i.h. injections of Ang IV were no different from vehicle controls, while Ang II produced a dose-dependent amnesic effect on the passive avoidance task.

In contrast to these findings, two studies from the same group (Braszko, Kupryszewski, Witzcuk & Wisniewski,1988; Braszko et al., 2006) found that i.c.v. administration of either Ang IV or Ang II in rats significantly improved recall relative to controls, increasing re-entry latencies on the passive avoidance task. The increase was approximately seven-fold in the first study. Wright et al. (1993) found that rats treated with either 0.1 or 1 nmol (but not 0.01 nmol) i.c.v. Ang IV had significantly increased re-entry latencies on Day 2; however, the group treated with Ang II was no different from aCSF controls. Groups were no different on day 4. Similarly, Wright et al. (1996) found that 1 nmol of i.c.v. Ang IV facilitated the conditioned response over 2 days of retention testing in rats. Tchekalarova et al. (2001) found that Ang IV at increasing doses of 0.01, 0.1, 0.5 and 1 μg/rat produced a dose-dependent, inverted-U improvement of retention on the task, with the lowest and highest doses not reaching statistical significance. The researchers also found that administering Ang IV with theophylline (an adenosine receptor antagonist) improved retention when theophylline was injected 24 hours following Ang IV, but not when it was injected 7 days later. Conversely, beneficial effects of Ang IV treatment alone were attenuated with coadministration with i.c.v. sarilesin (an Ang II analog) or i.p. N6-cyclopentyladenosine (CPA), a selective adenosine A1 receptor agonist.

3.2.4. Studies of conditioned avoidance.

Braszko et al. (1988) reported that i.c.v. treatment with Ang IV or Ang II both significantly improved rate of acquisition of (+)CARs, starting with day 2, compared with controls. The rate of learning between the Ang IV and Ang II groups did not differ. Ang IV treatment was significant on days 4–8, while Ang II treatment was significant on days 2–8.

3.3. Effects of Ang IV/AT4R in overcoming cognitive deficit

Eight studies investigated the effects of Ang IV or AT4R in models of cognitive deficit which was induced by i.c.v., i.h., or intravenous (i.v.) administration of scopolamine or mecamylamine. Control conditions in these studies consisted of injections of artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF) or saline. One study examined effects in a model of cerebral ischemia induced by four-vessel occlusion (4-VO).

3.3.1. Scopolamine studies.

Norleucine1-Ang IV (Nle1-Ang IV).

Out of the seven scopolamine studies, four evaluated the ability of the analog Nle1-Ang IV or its derivatives to reverse induced memory deficits, and all four found beneficial effects of administration of these peptides. Three studies reported that i.c.v. treatment with Nle1-Ang IV improved performance on the MWM task and was associated with reduced latency to find the hidden platform, greater time in the target quadrant during probe trials (Benoist et al., 2011; Pederson, Harding & Wright, 1998), and shorter swim distances (Pederson, Harding & Wright, 1998; Pederson, Krishnan, Harding & Wright, 2001) compared to scopolamine-aCSF controls. Of these, one study (Pederson et al., 2001) also found that dual treatment with Nle1-Ang IV and the AT4R antagonist Nle1, Leual3-AngIV was associated with MWM performance that was equivalent to that of the scopolamine-aCSF control animals, including a slower rate of acquisition, greater distance swum, slower efficiency ratio, and less time spent in the target quadrant. Thus, Nle1-Ang IV-related improvement appears to be due to activation at the AT4R site.

The fourth study utilized i.h. injections of Nle1-Ang IV, which were associated with reduced within-phase errors compared to scopolamine-only controls on the SWSh task of the radial arm maze (Olson & Cero, 2010).

Nle1-Ang IV derivatives.

C-terminal truncated analogs.

The Benoist et al (2011) study examined the performance of rats treated with not only Nle1-Ang IV but also any of its various C-terminal truncated analogs, Nle1-YIHP (pentapeptide), Nle1-YIH (tetrapeptide), Nle1-YI (tripeptide) and Nle1-Y (dipeptide), to determine the minimum structural features required of the Ang IV molecule to maintain its procognitive effects. Treatment with any one of these peptides, except for Nle1-Y, was associated with better MWM performance (reduced latency to find the platform) compared to the control group, by Day 3. By Day 8, these groups were as skilled as the vehicle control group and did not differ. During the probe trial, the Nle1-YIHP, Nle1-YIH, and Nle1-YI groups spent significantly more time in the target quadrant than the Nle1-Y group, demonstrating better retention of previous spatial information. Further experiments examining the efficacy of various doses of Nle1-YI, the smallest effective analog, revealed the dose of 5 nmol to yield acquisition which was not statistically different from Nle1-Ang IV, Nle1-YIHP, or Nle1-YIH. Taken together, these results highlighted the three N-terminal amino acids which are crucial for cognitive benefit, as well as the dose required of the smallest compound for retention of its procognitive property (Nle-Tyr-Ile).

Dihexa.

The effects of dihexa, a metabolically stabilized and orally active Nle1-Ang IV derivative, were examined in two studies using the MWM task. Treatment with dihexa was found to reduce latency to find the hidden platform (Benoist et al., 2014, McCoy et al., 2013) and increase time spent in the target quadrant (McCoy et al., 2013) compared to controls, indicating reversal of the memory deficit seen with scopolamine. This was with both i.c.v. (Benoist et al., 2014), oral, and i.p. application (McCoy et al., 2013). High doses (1.0 nmol i.c.v., 0.50 mg/kg/day, i.p., 2.0 mg/kg/day) produced performances which were significantly better than scopolamine-only treated groups and indistinguishable from vehicle (aCSF) controls.

N-acetyl-Nie-Tyr-Ile-His, D-Nle-Tyr-Ile, GABA-Tyr-Ile, Nle-Tyr-Ile-His-amide.

Compounds comprising various modifications to increase the metabolic stability of Nle1-Ang IV (e.g. substitution of D-norleucine for L-norleucine) were themselves tested to see if they retained the procognitive effect of Nle1-Ang IV. Each of the N-acetyl-Nie-Tyr-Ile-His, D-Nle-Tyr-Ile, GABA-Tyr-Ile, and Nle-Tyr-Ile-His-amide-treated groups demonstrated improved MWM performance (reduced latency) by Day 3, and each group performed significantly better than the scopolamine control group by Day 8. Out of all the compounds, GABA-Tyr-Ile was associated with the lowest mean latency to find the hidden platform from the other three groups, which did not differ from each other. On the probe trial, all compound-treated groups performed significantly better than the vehicle control group, spending more time in the target quadrant, and GABA-Tyr-Ile was again associated with the most superior performance (McCoy et al., 2013). These results, occurring in the context of the replacement of the N-terminal norleucine with GABA, revealed that norleucine is not necessary for maintaining procognitive ability of the peptide.

LVV-hemorphin-7 (LVV-H7).

One study examined the effect of i.c.v. treatment of the AT4R ligand LVV-H7. LVV-H7 treatment was associated with reduced latency to finding the hidden platform and shorter swim distances on the MWM task, which was performance that was significantly better than the scopolamine-aCSF controls, and no different from aCSF-aCSF controls (Albiston et al., 2004). This same pattern of results was found on a passive avoidance task, where LVV-H7-treated rats took significantly longer to enter a dark compartment where they had previously received a footshock, compared to scopolamine-aCSF controls – performance which was commensurate to that of aCSF-aCSF controls (Albiston et al., 2004).

3.3.2. Mecamylamine study.

One study investigated the effects of Nle1-Ang IV in a model of mecamylamine-induced deficit (Olson et al., 2004). Rats treated with Nle1-Ang IV exhibited better performance than mecamylamine-aCSF controls, and had reduced latency to the hidden platform which approximated that of aCSF-aCSF and aCSF-Nle1-Ang IV controls. However, there were no differences between the mecamylamine-aCSF and mecamylamine-Nle1-Ang IV groups on distance swum on Day 8.

3.3.3. Scopolamine + mecamylamine study.

One study investigated the effects of Nle1-Ang IV in a model of dual impairment (Olson et al., 2004). Whereas Nle1-Ang IV significantly decreased mecamylamine-induced learning deficits on MWM acquisition training, as just described, it failed to do so in a model of dual impairment by scopolamine and mecmylamine, when administered at doses of 1, 5, or 10 nmol. There were no group differences in swim latency during acquisition, swim distance, or swim latency on a probe trial.

3.3.4. 4-vessel occlusion.

One study examined the effects of Ang IV in rats with four-vessel occlusion as a model of ischemia-induced brain damage (Wright et al., 1996). Treatment with i.c.v. injections of Ang IV facilitated passive avoidance conditioning on a step-down task on days 2 and 3 in the 4-VO group when compared to a aCSF-control group. However, there was no difference between the groups on days 4 and 5 of retention testing.

3.3.5. Dose-response relationships.

As shown in Table 4, doses of 1 nmol of i.c.v. injections of Ang IV, Nle1-Ang IV, Dihexa, LVV-H7, Nle1-YIHP or Nle1-YIH have been successful in reducing induced cognitive deficits in these models.

Table 4.

Effective doses of various Ang IV- and Nle1-Ang IV-analogs in reversing induced memory deficits.

| Compound | Route | Effective dose | Effect | Study | Deficit induced by |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ang IV | i.c.v. | 1 nmol | Passive avoidance conditioning improvement | Wright et al (1996) | Four vessel occlusion |

| LVV-H7 | i.c.v. | 1 nmol | Passive avoidance conditioning & spatial working memory improvement | Albiston et al (2004) | Scopolamine |

| Nle1-Ang IV | i.c.v. | 0.1 nmol | Spatial working memory improvement | Pederson et al (2001) | Scopolamine |

| 1 nmol | Spatial working memory improvement | Pederson, Harding & Wright (1998); Pederson et al (2001) | Scopolamine | ||

| 10 nmol | Spatial working memory improvement | Olson et al (2004) | Mecamylamine | ||

| i.h. | 1 nmol | Spatial working memory improvement | Olson & Cero (2010) | Scopolamine | |

| Nle1-YIHP or Nle1-YIH | i.c.v. | 1 nmol | Spatial working memory improvement | Benoist et al (2011) | Scopolamine |

| Nle1-YI | i.c.v. | 5 nmol | Benoist et al (2011) | Scopolamine | |

| N-acetyl-Nie-Tyr-Ile-His | i.c.v. | 1 nmol | Spatial working memory improvement | McCoy et al (2013) | Scopolamine |

| D-Nle-Tyr-Ile | i.c.v. | 1 nmol | |||

| GABA-Tyr-Ile | i.c.v. | 1 nmol | |||

| Nle-Tyr-Ile-His-amide | i.c.v. | 1 nmol | |||

| Dihexa | oral | 2 mg/kg | |||

| i.c.v. | 1 nmol | ||||

| i.p. | 0.50 mg/kg |

Routes of administration: i.c.v., intracerebroventricular; i.h., intrahippocampal; i.p., intraperitoneal

3.4. Effects of Ang IV/AT4R in models manipulating the dopaminergic system

As shown in Table 5, four studies utilized rats pre-treated with D1, D2, D3 and D4 dopamine receptor antagonists (Braszko, 2004, 2006; Braszko, Wielgat & Walesiuk, 2008; Braszko, 2009). In the first two studies, rats which received either i.c.v. Ang IV or des-Phe6-Ang IV alone performed significantly better on (1) a task of conditioned avoidance, producing more CARs, and (2) a task of passive avoidance, entering the dark compartment later, and (3) object recognition, spending more time exploring the novel object B vs. familiar object A, compared to (1) vehicle controls and (2) rats which had been pretreated with SCH23390, a D1 dopamine receptor antagonist (Braszko, 2004) or remoxipride, D2 dopamine receptor antagonist (Braszko, 2006), prior to receiving either i.c.v. Ang IV or des-Phe6-Ang IV, or (3) rats which had received only SCH23390 or remoxipride alone.

Table 5.

Characteristics of studies examining the effects of modulating the dopaminergic system, voltage-gated calcium channels, or PKMzeta.

| Study | Test used | Peptide / compound exogenously applied | Effect on performance | Dose | First dose timing | Route | Species | Model | STAIR score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Braszko (2004) | CA PA OR |

Ang IV | ↑ without pre-treatment with SCH23390 | 1nmol | 15 min before training | i.c.v. | Male WR | Pre-treatment with 0.05 mg/kg of SCH23390 (D1 dopamine receptor) i.p. | 2 |

| des-Phe6-Ang IV | ↑ without pre-treatment with SCH23390 | ||||||||

| Braszko (2006) | CA PA OR |

Ang IV | ↑ without pre-treatment with remoxipride | 1nmol | 15 min before training | i.c.v. | Male WR | Pre-treatment with 5µmol/kg of remoxipride (D2 dopamine receptor) i.p. | 2 |

| des-Phe6-Ang IV | ↑ without pre-treatment with remoxipride | ||||||||

| Braszko (2009) | PA OR RAM |

Ang IV | ↑ without pre-treatment with L745,870 | 1nmol | 45 min after first trial | i.c.v. | Male WR | Pre-treatment with 1mg/kg of L745,870 (D3 dopamine receptor antagonist) i.p. | 4 |

| des-Phe6-Ang IV | ↑ without pre-treatment with nafadotride | ||||||||

| L745,870 alone | ↑ | ||||||||

| Braszko, Wielgat & Walesiuk (2008) | PA OR RAM |

Ang IV | ↑ with and without pre-treatment with L745,870 | 1 nmol | 45 min after first trial | i.c.v. | Male WR | Pre-treatment with nafadotride (D4 dopamine receptor blocker) i.p. | 3 |

| des-Phe6-Ang IV | ↑ without pre-treatment with L745,870 | ||||||||

| Braszko et al (2017) | IA OR |

Ang IV | ↑ alone – with pre-treatment with nimodipine or mibefradil |

1 nmol | 15 min before testing | i.c.v. | Male WR | Pre-treatment with nimodipine (12 mg/kg) or mibefradil (1 mg/kg) | 3 |

| Chow et al (2015) | Modified OR test | Ang IV | ↑ | 1 nmol | 15 min before testing | i.c.v. | Male SDR | Co-adminstration with ZIP (PKMzeta inhibitor) | 3 |

Tests used: CA, Conditioned Avoidance; IA, Inhibitory avoidance; OR, Object recognition; PA, passive avoidance; RAM, radial arm maze

Peptides/compounds applied: Ang IV, Angiotensin IV

Effects: ↑, improves test performance; ↓, worsens test performance, –, has no effect on performance

Routes of administration: i.c.v., intracerebroventricular; i.p., intraperitoneal

Species: SDR, Sprague Dawley Rats; WR, Wistar Rats

In the third study (Braszko, 2009), similarly, i.c.v. Ang IV or des-Phe6-Ang IV were associated with improved performance on (1) a task of passive avoidance, and (2) object recognition compared to (1) vehicle controls, (2) rats pretreated with the D4 dopamine receptor antagonist L745,870 prior to either i.c.v. Ang IV or des-Phe6-Ang IV, or (3) rats which had received only L745,870. On a task of spatial working memory in the radial arm maze, all groups which had received Ang IV or des-Phe6-Ang IV (1) made significantly fewer errors, (2) visited more consecutive correct arms prior to the first error, and (3) completed visits faster, compared to control groups, regardless if they had been pre-treated with L745,870. Treatment with L745,870 alone also significantly decreased errors made in the maze.

In the fourth study (Braszko, Wielgat & Walesiuk, 2008), treatment with Ang IV or des-Phe6-Ang IV, as well as pre-treatment with the D3 dopamine receptor antagonist nafadotride followed by Ang IV was associated with better performance (longer latency to enter dark compartment) on a test of passive avoidance, compared with saline controls. Rats which received either nafadotride alone or nafadotride + des-Phe6-Ang IV were no different from controls, suggesting that nafadotride is ineffective on its own in blocking Ang IV effects and is only mildly effective in blocking des-Phe6-Ang IV effects. On tests of object recognition and spatial working memory, all groups which had received Ang IV or des-Phe6-Ang IV spent more time exploring a novel object compared to a familiar object, made fewer errors in a radial arm maze, visited more consecutive correct arms before the first error, and completed the maze faster, compared to control groups, regardless if they had been pre-treated with nafadotride.

3.5. Effects of Ang IV/AT4R in a model modulating VGCCs

One study (Braszko et al., 2017) examined the effects of Ang IV following pre-treatment with nimodipine or mibefradil, two VGCC-inhibitors (Singhal & Sandhir, 2015; Massie, 1997). On tasks of passive avoidance and object recognition, rats treated with Ang IV only showed better performance (longer latency avoiding the dark compartment, longer time spent on novel vs. familiar object) compared to controls. However, pretreatment with nimodipine or mibefradil abolished these effects. In both tasks, treatment with nimodipine or mibefradil alone had no effect.

3.6. Effects of Ang IV/AT4R in a model modulating PKMzeta

One study (Chow et al., 2015) examined the effects of Ang IV with co-administration with a PKMzeta inhibitor (ZIP) on performance of a modified form of the object recognition test. The group which received Ang IV alone spent the greatest percentage of its total exploration time on the novel object when compared to the other groups (saline, ZIP only, and ZIP + Ang IV).

3.7. Effects of Ang-(1–7)/Mas

As shown in Table 6, two of three studies found that Ang-(1–7) ameliorated cognitive deficit in models of impairment. In a rat model of chronic cerebral hypoperfusion, Xie et al (2014) found that Ang-(1–7) alleviated learning deficits on the MWM that were induced by permanent bilateral common carotid artery occlusion [the 2-vessel occlusion (2-VO) model]. Rats treated with prior i.c.v. infusion of high-dose (10 pg/h for 2 weeks) Ang-(1–7) showed reduced escape latency compared to 2VO-aCSF controls on days 1, 2, 3 of testing; the low dose (0.1 pg/h for 2 weeks) was associated with reduced latencies on days 2 and 3. All 2VO animals had lower numbers of correct crossings and spent less time in the target quadrant, effects which were ameliorated by Ang-(1–7). These Ang-(1–7) effects were abolished by coadministration of A-779, an antagonist of the Mas receptor, implicating Mas in the Ang-(1–7) signaling pathway. Swimming speed was not affected by either the 2VO model or by i.c.v. infusions, suggesting that the deficits were not attributable to differences in motor ability.

Table 6.

Characteristics of Ang-(1–7) or Mas receptor studies.

| Study | Test used | Peptide exogenously applied | Effect on performance | Dose | First dose timing | Route | Species | Model | STAIR score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bonini et al (2006) | Inhibitory avoidance | Ang IV Ang-(1–7) |

– | 0.5µg/side each | 15 min before testing | i.h. | Male WR | No induced memory deficit | 2 |

| Lazaroni, Bastos, Moraes, Santos & Pereira (2015) | Auditory fear conditioning Contextual fear conditioning |

Mas receptor removed | – Auditory (cued) fear memory ↓ contextual fear memory |

N/A | N/A | N/A | Male MasKO mice on FVB/N and MasKO mice on mixed 129xC57BL/6 | No induced memory deficit | N/A |

| Uekawa et al (2016) | Morris Water Maze | Ang-(1–7) | ↑ | 500 ng/kg/h | Not reported, infused for 4 weeks | i.c.v. | 5XFAD mice | Alzheimer’s disease model | 4 |

| A-779 | ↓ | 5.0 µg/kg/h | |||||||

| Xie et al (2014) | Morris Water Maze | Ang (1–7) | ↑ | 0.1, 10 pg/h | 2 weeks before testing | i.c.v. | Male WR | Chronic cerebral hypoperfusion | 4 |

| A-779 | ↓ | 10 pg/h |

Peptides/compounds applied: Ang IV, Angiotensin IV; Ang-(1–7), Angiotensin-(1–7)

Effects: ↑, improves test performance; ↓, worsens test performance, –, has no effect on performance

Species: MasKO, Mas knockout mice; WR, Wistar Rats.

Similarly, Uekawa et al. (2016) found that Ang-(1–7) attenuated cognitive impairment as measured on the MWM in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease (5XFAD mice). Ang-(1–7) treatment (i.c.v. infusions for 4 weeks, at 500 ng/kg/h) was associated with an increased number of correct crossings, time spent in the target quadrant, and distance traveled in the quadrant, compared to the vehicle group. Co-administration with A-779 abolished the beneficial Ang-(1–7) effects. There were no differences among the groups on visual acuity and motor ability. Contrary to these results, the Bonini et al (2006) study did not find any effect of Ang-(1–7), administered i.h., in improving cognition in rats without any induced deficit.

One study (Lazaroni et al., 2015) examined the effect of genetically removing the Mas receptor in a study of (a) Mas knockout mice (MasKO mice) in a FVB/N background, which is characterized by mild hypertension and endothelium dysfunction, and their controls (FVB/N mice), as well as (b) MasKO mice in mixed 129xC57BL/6 background, which are normotensive mice without alterations in baseline heart rate (Walther et al., 2000), and their controls, wildtype (WT) mice. On a task of auditory fear conditioning, MasKO mice spent more time freezing than their FVB/N controls during conditioning, but were no different from controls on a test of extinction (cued fear memory). On a task of contextual fear memory, MasKO mice showed delayed extinction following a 3CS/US protocol compared to WT controls, took one trial longer to show extinguished fear memory, and displayed significantly more freezing behavior compared to WT controls on sessions 4 and 5 of extinction testing. However, MasKO mice were no different from WT controls following a 1CS/US protocol. There were no differences among the mice strains on tests of reactivity to foot shock or locomotor activity.

4. Discussion

Clinical trials examining the potential of currently available drugs such as statins and non-steroidal inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) for the treatment or prevention of dementia and AD have, unfortunately, not found them to be as efficacious as expected (Kelleher & Soiza, 2013). However, studies of the cognitive effects of brain RAS peptides have had more encouraging results, leading to increased attention being paid to the possible role for angiotensins such as Ang-(1–7) and Ang IV in reversing cognitive impairment, particularly the kind observed in dementia (Wright & Harding, 2009). The present review adds to the literature by highlighting the procognitive, antidementia qualities of these potential therapeutic agents, as demonstrated in experimental models of normal animals as well as animals with induced cognitive impairment. We also identify the ideal routes and timing of administration of brain RAS peptides in these preclinical studies.

In this review, two out of three studies of Ang-(1–7), administered i.c.v., found that it improved memory performance in mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease (Uekawa et al., 2016) as well as cerebral ischemia (Xie et al., 2014). In contrast, one study in normal rats (Bonini et al., 2006) did not find any effect of Ang-(1–7) on memory; however, in this study, the peptide was administered through a different route (i.h.). Seven out of 11 studies of acute administration of Ang IV (either i.c.v. or s.c.) in normal rats or mice found that it was associated with better performance on tests of passive or conditioned avoidance behavior and object recognition. Contrary to these findings, four studies found that it had no effect on performance of tests of inhibitory or passive avoidance or spatial working memory.

4.1. The route and the timing of peptide administration, task modification, and differential mice strains may affect findings

Two of the studies which failed to show any beneficial effects of Ang IV administered it directly to the hippocampus (Bonini et al., 2006; Kerr, 2005); Ang IV appears most effective when introduced intracerebroventricularly (Braszko et al., 1988, 2006; Paris et al., 2013; Tchekalarova et al., 2001; Wright et al., 1993, 1996). This difference may be due to the ability of i.c.v. injections to diffuse to different parts of the cortex (including the hippocampus), as compared to i.h. treatment, whose effects are circumscribed to the hippocampal area. With regard to consistency, injecting into the same region of the hippocampus in every animal is difficult and made more challenging by the fact that only minor concentrations are needed. The hippocampus also sustains some damage in this process. Thus, i.c.v. treatment is potentially more effective given that it produces more global effects due to diffusion, is easier to perform consistently among animals, and can be done in larger doses.

Further, in rats, Ang IV appears to exert beneficial effects when given 5–15 minutes prior to learning (Wright et al., 1996; Braszko et al., 1988), immediately after learning (Golding et al., 2010; Tchekalarova, Kambourova, & Georgiev, 2001), or 5–30 minutes prior to testing (Braszko et al., 2006; Paris et al., 2013; Wright et al., 1993). However, the Kerr (2005) study administered Ang IV some 30, 90, and 180 minutes following training, which may have been simultaneously outside the optimal window for Ang IV to exert its hypothesized consolidation-enhancing effects around the time of training, as well as too far away from the testing time for its recognition-enhancing effects.

Ang IV may also have differential strain effects. Researchers from the Gard et al. (2007) study, which failed to find any effect of Ang IV in female BKW mice on an object recognition task, noted that their lab had replicated this effect in multiple other studies in unpublished data, although they had found positive effects of Ang IV in DBA2 mice (Gard & Pavli, 2004). Similarly, the Golding et al. (2010) study found Ang IV enhanced recall at 4.7 μg/kg and 47 μg/kg in DBA2 mice, and at 4.7 μg/kg in C57 strain mice, while CD mice showed no improvement. These results may have been due in part to differences in baseline performance, with DBA2 mice commonly performing worse than C57 mice on object recognition tasks (Ammassari-Teule et al., 1998), which may have allowed more room for improvement for DBA2 mice. Further, the lack of response in the CD strain at varying doses, compared to memory improvement observed in other strains, suggests that the null result was due neither to the lack of bioavailability nor accelerated metabolism of Ang IV (Golding et al., 2010). It is possible that the mechanisms of action of Ang IV differ from strain-to-strain. One suggested mechanism is the inhibitory effects of Ang IV on insulin regulated aminopeptidase (IRAP), which is considered the binding site of AT4R. Notably, this study also found that such inhibitory effects were not significantly different across strains, which implies that a different mechanism is likely at play. The authors postulated that aminopeptidase N (ApN), which is important in Ang IV catabolism and metabolism, was present in increased levels in unresponsive CD mice, which suggests a mediating role of ApN in the cognitive effects of Ang IV (Golding et al., 2010).

It is unusual that Holownia & Braszko (2003) failed to find any influence of Ang IV on the rate of acquisition on the MWM task, given the ideal first dose timing (15 mins prior to training) and route of administration (i.c.v.). However, the version of the MWM task used in this study may have differed from the traditional MWM; it is unclear whether or not spatial cues were present on the walls of the tank. Additionally, while the starting location for animals typically changes over learning and testing trials, in this study, the starting point for swimming remained the same over the course of the study. The authors noted that their version of the task evaluated “reference” as opposed to working memory (Holownia & Braszko, 2003). Therefore, it is likely that the modified version of this task tapped into a different construct than is measured using the classic MWM task.

4.2. More stable analogs of Ang IV are able to reverse cognitive deficit

In this review, all seven studies examining the effects of Ang IV, its analogs (e.g. Nle1-Ang IV), its analog-derivatives (e.g. Nle1-YI, Dihexa, GABA-YI), and other AT4R ligands (e.g. LVV-H7) found that acute administration of these compounds through various routes (i.c.v. or i.h.) had beneficial effects in animal models of cognitive impairment induced by blockade of ACh receptors with scopolamine. Rats showed preserved spatial working memory as well as memory of learned avoidance behavior from prior conditioning tasks. One study (Wright et al., 1996) found that Ang IV was similarly protective in a model of cerebral ischemic injury, and another study reported that Nle1-Ang IV reversed the effects of induced deficit by mecamylamine (Olson et al., 2004). Across these studies, the dose of 1 nmol of these various peptides appeared to be effective in reversing cognitive impairment.

4.3. Dihexa may be the most promising compound for testing in humans

Despite such promising results, various physiochemical properties of these peptides have hindered their development into efficacious antidementia drugs. Ang IV is susceptible to metabolic degradation and too big to cross the BBB. Its analog, Nle1-Ang IV, would be a more feasible alternative if of a smaller size. Nle1-Ang IV analogs themselves (e.g. Nle1-YIH and Nle1-YI), while small in size, are too hydrophilic to cross the BBB. Therefore, the most promising compound in terms of potential for future testing in humans is the Nle1-Ang IV-derived dihexa, which is the result of N- and C-terminal modifications that increase the hydrophobicity and metabolic stability of its parent peptide and render dihexa BBB-penetrant (McCoy et al., 2013). Dihexa is able to reverse memory impairment induced by scopolamine, whether administered i.c.v. (Benoist et al., 2014; McCoy et al., 2014), orally, or intraperitoneally (McCoy et al., 2014), and high doses in rats (1.0 nmol i.c.v., 0.50 mg/kg/day, i.p., 2.0 mg/kg/day) produce performances which are indistinguishable from vehicle controls.

It has been proposed that the cognitive effects of Ang IV-derivatives such as dihexa may be due to their ability to initiate the formation of dendritic spines and new synapses. Treatment with Nle1-Ang IV or its truncated analogs in the Benoist et al. (2011) study, for example, was associated with significant increases in the average number of dendritic spines, following 5 days of treatment, compared with vehicle controls. The Nle1-Ang IV group (mean spine numbers = 32.4) showed a 103% increase vs. controls (mean spine numbers = 16.0), and treatment with each truncated peptide was related to similar increases. Similarly, dihexa has been found to increase spinogenesis in an in vitro model of cultured hippocampal neuron cultures; spines increased nearly threefold following 5 days of treatment with dihexa, and over twofold with Nle1-Ang IV (McCoy et al., 2013). Further immunocytochemistry studies confirmed that these new treatment-induced spines did not differ from neurons from control animals in terms of the synaptic machinery present, and studies of whole cell recordings found that the frequency of miniature postsynaptic excitatory currents (mEPSCs) in the peptide-treated groups rose, as expected, given the increase in spines. These findings suggest that treatment with Nle1-Ang IV and dihexa results in the formation of functional spines.

Such augmented spinogenesis may underlie the beneficial effects of these peptides, making them potential therapeutics for the treatment of dementia, which is caused by reduced synaptic connectivity among neurons, as well as neuronal death in the entorhinal cortex, hippocampus, and neocortex (Braak & Braak, 1991). Nevertheless, while dihexa’s procognitive properties have been demonstrated in its reversal of scopolamine-induced deficit, it remains to be seen if dihexa would be similarly beneficial in maintaining cognition in models without impairment. Its parent peptide, Nle1-Ang IV, has been associated with better memory performance in such models (Lee et al., 2004; Wright et al., 1999), so the potential for this is promising.

4.4. Partial preservation of the cholinergic and adenosine systems may be necessary for AT4R-mediated cognitive effects

Across all studies, only one found failure of an Ang IV analog or AT4R ligand to reverse the effects of induced deficit; Olson et al. (2004) reported that Nle1-Ang IV failed to do so in the context of dual blockade of muscarinic and nicotinic ACh receptors, both of which are implicated in cognitive processing. Muscarinic and nicotinic ACh receptors differentially regulate excitatory and inhibitory post-synaptic potentials during LTP and have varying effects on cognition, as shown in one study in this review, which demonstrated that detrimental cognitive effects of the AT4R-antagonist Divalinal-Ang IV could be reversed with the co-administration with nicotine (a nicotinic agonist), but not with carbachol, a muscarinic agonist (Wilson et al., 2009). It is possible that there is an interaction effect whereby deficiencies caused by antagonism of either the nicotinic or muscarinic receptors are surmountable by Nle1-Ang IV, whereas combined antagonism of both may be too overwhelming for Nle1-Ang IV to exert its effects. Therefore, while Nle1-Ang IV may be of little use if both are already compromised, there is potential for AT4R-mediated pathways to ameliorate cognitive deficits if these receptor systems are at least partially preserved. Hence, the combined treatment of these systems may be necessary in addition to intervention with AT4R-ligands.

This review only found one study which examined the effects of co-administration of Ang IV with adenosine receptor-related drugs (Tchekalarova et al., 2001) given the evidence for adenosine-angiotensin interactions (Lin, Wan, Tung, & Tseng, 1995) and the possibility for this system to also be implicated in the cognitive enhancing effects of Ang IV. Administration of Ang IV with theophylline (an adenosine receptor antagonist), both in ineffective doses on their own, enhanced retention in a passive avoidance task, while coadministration of Ang IV with CPA (an adenosine receptor agonist), attenuated memory enhancement by Ang IV. Future work would do well to investigate the mediating effects of blocking adenosine activity, given that adenosine is an inhibitory neuromodulator (Trachte & Heller, 1990).

4.5. Effects of Ang IV and/or AT4R involve a multiplicity of different pathways, systems, and mechanisms

Taken together, the results from the studies in this review suggest that the beneficial effects of Ang IV and/or AT4R may be mediated by several different pathways. First, the cholinergic system (and particularly, muscarinic and nictonic ACh receptor activity), as well as the adenosine and dopaminergic systems have clear influence on the effects of Ang IV and its analogs, and at least partial preservation of these systems may be necessary for beneficial Ang IV effects on cognition. The physiological signals that shift the balance among these different pathways towards a pathological state are as yet unknown. In the four studies examining the influence of the dopaminergic system, rats which received Ang IV or its smaller derivative des-Phe6-Ang IV performed better on tasks of passive avoidance and object recognition than rats who received either peptide co-administered with the D1 or D2 dopamine receptor antagonists (Braszko, 2004; Braszko, 2006). Of note, treatment with L745,870 alone (a D4 dopamine receptor antagonist) was associated with fewer errors on the radial arm maze, and combined treatment of nafadotride (a D3 dopamine receptor antagonist) with Ang IV was associated with better performance on a task of passive avoidance (Braszko, 2008; Braszko et al., 2008), indicating some benefit of blockade of the D3 and D4 receptor types over the D1 or D2 types.

Despite these potential benefits, it must be noted that the involvement of the dopaminergic system, which sees increases in neurotransmission following intracerebral administration of Ang-(1–7) (Braszko et al., 1991; Pawlak et al., 2001), possibly mediated by Ang IV (Møeller et al., 1998) poses a major possible problem for applications in humans, given that it suggests dopaminergic side effects. These may include movement disorders, excessive daytime sleepiness, sleep-disordered breathing, hallucinations, and impulse control disorders (Borovac, 2016). Any future trials of developing Ang IV or Ang-(1–7) for clinical use should include monitoring participants carefully for these potential adverse effects.

One mechanism behind Ang IV effects may be spinogenesis, as earlier described, but this is likely not the only pathway underlying procognitive effects observed. Another compound that demonstrated beneficial effects on cognition in the experimental studies of induced memory impairment was GABA-YI. However, while rats treated with GABA-YI demonstrated the most superior cognitive performance, surprisingly, it was not as potent as the acetyl-Nle-YIH and D-Nle-YI analogs at promoting spinogenesis (McCoy et al., 2013). Other mechanisms underlying effects may involve VGCCs (Braszko et al., 2017) and PKMzeta (Chow et al., 2015), given that VGCC blockade and PKMzeta inhibition abolished procognitive Ang IV effects. Notably, PKMzeta inhibition alone did not cause any appreciable decrease in performance on a modified object recognition task, suggesting that it likely mediates Ang IV-effects only to some extent, possibly through maintenance of LTP (Ling et al., 2002; Serrano et al., 2005). Such induction of LTP in the first place may require functional VGCC activity, given that Nle1-Ang IV-induced LTP has been found to be decreased by the nonselective VGCC blockers nimodipine and flunarizine (Davis et al., 2006). Therefore, these systems are interrelated and should be studied in light of each other, as opposed to in isolation.

4.6. Ang IV effects may be mediated by binding to receptors other than AT4R

Ang IV effects may not be due to its activation of the AT4R alone. While co-administration of Ang IV and the AT4R-antagonist Divalinal-Ang IV ameliorates the procognitive effects of Ang IV (Lee et al., 2004; Paris et al., 2013; Wilson et al., 2009; Wright et al., 1999), these same effects were also surprisingly attenuated by administration of sarilesin, a non-specific angiotensin receptor antagonist which blocks both AT1Rs and AT2Rs (Tchekalarova et al., 2001). The role of the AT2R is less known, although it is found in lower quantities than AT1R in adults (Steckelings, Kaschina & Unger, 2005) and its differential distribution patterns in fetal and adult animals suggests a role in maturation and differentiation (Tsutsumi & Saavedra, 1991). AT1R activity includes the generation of free radicals and the activation of multiple inflammatory pathways, all of which lead to tissue damage (Suzuki et al, 2003), and their presence in greater quantities, despite the blockade of both receptor types, may explain the attenuation of cognitive effect here.

It is also possible that effects on any of these receptors (AT1R, AT2R, or AT4R) may influence activity by other receptors through crosstalk or receptor-receptor interactions. For example, in vitro studies have shown the capability of the AT2R to functionally antagonize the AT1R (AbdAlla, Lother, Abdel-tawab & Quitterer, 2001) and for the Mas receptor to inhibit AT1R action (Kostenis et al., 2005). Additionally, Ang IV is known to mediate central pressor effects through binding to the AT1R (Yang et al., 2008); hence, some of its cognitive effects may involve this receptor type as well. However, there is little research in this area, given the much higher affinity of Ang IV for AT4R as opposed to AT1R (Speth et al., 1985).