Abstract

From the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research (WRAIR) inventory, thirteen 8-aminoquinoline analogs of primaquine were selected for screening against a panel of seven Plasmodium falciparum clones and isolates. Six of the 13 8-aminoquinolines had average 50% inhibitory concentrations between 50 and 100 nM against these P. falciparum clones and were thus an order of magnitude more potent than primaquine. However, excluding chloroquine-resistant clones and isolates, these 8-aminoquinolines were all an order of magnitude less potent than chloroquine. None of the 8-aminoquinolines was cross resistant with either chloroquine or mefloquine. In contrast to the inactive primaquine prototype, 8 of the 13 8-aminoquinolines inhibited hematin polymerization more efficiently than did chloroquine. Although alkoxy or aryloxy substituents at position 5 uniquely endowed these 13 8-aminoquinolines with impressive schizontocidal activity, the structural specificity of inhibition of both parasite growth and hematin polymerization was low.

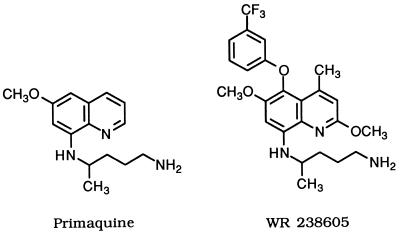

Primaquine, an 8-aminoquinoline (Fig. 1), is the only tissue schizonticide (exoerythrocytic) drug available for radical treatment of Plasmodium vivax or Plasmodium ovale infections. Although primaquine has no clinical utility as a blood schizonticide, what little activity it does possess against the erythrocytic form of the parasite may derive from an oxidative stress mechanism (5, 6, 17, 38, 40) since it well known that primaquine, largely via its hydroxylated metabolites, stimulates the hexose monophosphate shunt, increases hydrogen peroxide and methemoglobin (metHb) production, and decreases glutathione levels in the erythrocyte (2, 7, 17, 36, 39). Unfortunately, this same prooxidant property of primaquine is probably also responsible for its hemolytic side effect (17). Other potential mechanisms include inhibition of vesicular transport (22, 35) or inhibition of the parasite enzyme dihydroorotate dehydrogenase (25), although primaquine and other 8-aminoquinolines are relatively weak inhibitors of this enzyme. At this point, how primaquine acts against the erythrocytic form of the malaria parasite is not well understood.

FIG. 1.

Structures of primaquine and WR 238605.

As reviewed by Nodiff et al. (27) and Bhat et al. (9), substantial efforts have been made to identify an 8-aminoquinoline with a better therapeutic index than that of primaquine and with activity against blood stages of malaria. A potential primaquine replacement, WR 238605 (32) (Fig. 1), that at least partially fulfills these objectives has now been identified. Initial clinical studies show that WR 238605 is well tolerated (11), has a much longer half-life than primaquine, and may have considerable promise as a prophylactic drug for Plasmodium falciparum malaria (10) in addition to its potential as a radical curative and terminal eradication drug (11).

Of the many 8-aminoquinolines screened against the D6 and W2 clones (30) of P. falciparum at the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research (WRAIR), WR 238605 and 12 other 8-aminoquinolines were selected for systematic testing against a panel of seven P. falciparum clones and isolates to identify any patterns of cross-resistance. With this screening data in hand, we wished to determine whether 8-aminoquinolines active against blood stage parasites might work through a mechanism similar to that proposed for chloroquine, namely, by binding hematin μ-oxo dimer and inhibiting hematin polymerization (13, 15, 33, 34). By contrast, primaquine does not inhibit hematin polymerization although it does bind to hematin μ-oxo dimer with modest affinity (15).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Antimalarial assays.

Antimalarial activity against P. falciparum clones was determined as previously described by Desjardins et al. (12) and Milhous et al. (26). Seven P. falciparum clones and isolates were used in the susceptibility testing. The D6 and W2 clones were originally described by Oduola et al. (30). The NIG59 and NIG9171 (29) isolates were obtained from patients in Nigeria; the TM91C235 and TM91C40 isolates were obtained from patients in Thailand. TM91C235 was the parent isolate for the WR75-235 clone (8a).

Hematin polymerization.

Reactions were carried out essentially as described previously (13–15), using [14C]hemin. Purified hemozoin from the malarial parasite P. falciparum was used to initiate the reaction. 8-Aminoquinolines were added to the reaction mixture as dimethyl sulfoxide solutions with a maximum dimethyl sulfoxide concentration of 10%. The disintegration per minute values obtained from the assay were expressed as percent inhibition relative to hemozoin formation in a drug-free control. The values of triplicate assays were plotted semilogarithmically (CA-Cricket Graph III 1.5.2) and the 50% inhibitory concentrations (IC50s; micromolar) were calculated graphically along with the standard deviations (SD).

Statistical analyses.

Pearson and Spearman correlation coefficients were obtained by using SAS run on an IBM 3031 mainframe computer at the University of Nebraska Medical Center. All data presented is that from Pearson (parametric) correlation analyses.

Molecular modeling.

Molecular modeling experiments were performed by using Sybyl version 6.2 software (Tripos, Inc.) on a Silicon Graphics Indigo R4000 workstation. The different 8-aminoquinolines were constructed by using primaquine as a template. Each structure was assigned Delre charges and energy minimized by using molecular dynamics and the conjugate gradient method in conjunction with molecular mechanics. Hydrophobic and electrophilic potentials were calculated and visualized by using MOLCAD surfaces.

RESULTS

Antimalarial activity.

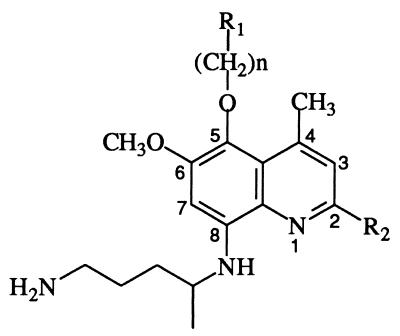

From the WRAIR inventory, 13 8-aminoquinolines (Table 1) were selected for screening against a panel of seven P. falciparum clones and isolates. All of these 8-aminoquinolines, with the exception of WR 268397, can be considered 2-methoxy-, 5-alkoxy-, 5-aralkoxy-, or 4-methyl-substituted (or combination thereof) primaquine derivatives. Results from these experiments provided an opportunity for analysis of structure-activity relationships, cross-resistance, and mode of action for these 8-aminoquinolines.

TABLE 1.

8-Aminoquinoline structures

| Compound | n | R1 | R2 | Dihedral angleb (°)a |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WR 249420 | 1 | 3-CF3C6H5 | H | 117.23 |

| WR 251855 | 1 | 3-CF3C6H5 | OCH3 | 141.11 |

| WR 254715 | 5 | C6H5 | H | 130.23 |

| WR 238605 | 0 | 3-CF3C6H5 | OCH3 | 139.56 |

| WR 255740 | 4 | C6H5 | H | 128.05 |

| WR 255821 | 8 | C6H5 | H | 133.86 |

| WR 259841 | 5 | 2-CF3C6H5 | H | 126.59 |

| WR 266848 | 5 | 4-CF3C6H5 | H | 114.64 |

| WR 268379a | 5 | CH3 | OCH3 | 118.10 |

| WR 268499 | 5 | 2-C4H3S | H | 116.76 |

| WR 268648 | 5 | 2,6-diCH3C6H5 | H | 124.08 |

| WR 268658 | 5 | 3-CH3C6H5 | H | 118.68 |

| WR 242511 | 5 | CH3 | H | 118.99 |

WR 268379 has a 3- rather than a 4-CH3 substituent.

Dihedral angle formed by the C-6 oxygen, the distal nitrogen, and the C-8 nitrogen. The dihedral angle for primaquine is 147.68°.

As shown in Table 2, 6 of the 13 8-aminoquinolines (WR 249420, WR 251855, WR 266848, WR 268499, WR 268658, and WR 242511) had IC50s between 50 and 100 nM for these P. falciparum clones and isolates and were thus an order of magnitude more potent than primaquine. Clone TM91C235 was especially susceptible to inhibition by these compounds. However, excluding chloroquine-resistant clones and isolates, these 8-aminoquinolines were all an order of magnitude less potent than chloroquine. There appear to be few obvious structural features in these 8-aminoquinolines that are uniquely associated with high intrinsic antimalarial activity. For example, at position 5, the length of the methylene bridge between the quinoline and pendant aromatic ring varied between 0 and 8 but had no predictable effect on relative antimalarial potencies. Similarly, the position and nature of phenyl substituents on the pendant aromatic ring had no significant effect on potency. Only WR 238605, with an oxygen atom bridge (diaryl ether) at position 5, and WR 255740, with a 5-atom O-(CH2)4 bridge at position 5, were significantly less active than the other 8-aminoquinolines tested. In a comparison of WR 255740 and WR 254715, it can be seen that the removal of single methylene in the C-5 O-alkyl bridge lowered activity by an order of magnitude. A 2-methoxy substituent conveyed no advantage in potency, as evident in a comparison of WR 251855 and WR 249420 and of WR 268379 and WR 242511.

TABLE 2.

In vitro antimalarial activity of 8-aminoquinolines against seven P. falciparum clones and isolates

| Compound | IC50 (nM) (mean ± SD)a

|

Avg IC50 (nM)b | No. of cross-resistant pairsc | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NIG59 | NIG9171 | D6 | W2 | TM91C235 | WR75-235 | TM91C40 | |||

| Chloroquine | 6.76 ± 3.02 | 410 ± 24 | 9.08 ± 2.85 | 312 ± 89 | 83.8 ± 22.4 | 179 ± 29 | 303 ± 203 | 186 | 0 |

| Mefloquine | 9.68 ± 6.76 | 4.68 ± 1.52 | 18.4 ± 10.7 | 4.10 ± 1.8 | 38.0 ± 7.7 | 40.5 ± 9.8 | 29.9 ± 5.6 | 20.8 | 0 |

| Primaquine | 1,270 ± 40 | 1,180 ± 400 | 1,950 ± 640 | 1,470 ± 370 | 1,050 ± 160 | 1,320 ± 250 | 1,590 ± 750 | 1,400 | 2 |

| WR 249420 | 110 ± 24 | 59.9 ± 21.7 | 81.5 ± 53.7 | 63.7 ± 38.7 | 29.4 ± 19.1 | 31.9 ± 1.3 | 82.3 ± 17.3 | 65.5 | 6 |

| WR 251855 | 204 ± 78 | 51.2 ± 16.9 | 132 ± 39 | 64.9 ± 22.8 | 20.8 ± 5.2 | 22.5 ± 4.4 | 95.1 ± 72.1 | 84.4 | 5 |

| WR 254715 | 133 ± 62 | 136 ± 9 | 187 ± 88 | 110 ± 65 | 52.4 ± 41.6 | 96 ± 10 | 157 ± 47 | 125 | 7 |

| WR 238605 | 688 ± 109 | 200 ± 82 | 1,470 ± 430 | 217 ± 49 | 59.4 ± 0.9 | 122 ± 8 | 294 ± 177 | 436 | 1 |

| WR 255740 | 1,740 ± 40 | 1,270 ± 90 | 1,430 ± 840 | 1,090 ± 690 | 274 ± 180 | 896 ± 181 | 1,620 ± 400 | 1,190 | 11 |

| WR 255821 | 158 ± 62 | 209 ± 33 | 133 ± 63 | 113 ± 38 | 48.3 ± 5.4 | 85.4 ± 38.3 | 212 ± 106 | 137 | 7 |

| WR 259841 | 307 ± 118 | 233 ± 43 | 213 ± 157 | 162 ± 70 | 46.2d | 133 ± 1 | 292 ± 106 | 198 | 10 |

| WR 266848 | 73.4 ± 8.1 | 92.3 ± 16.9 | 85.2 ± 27.8 | 56.3 ± 8.4 | 21.3 ± 1.3 | 43.8 ± 17.6 | 109 ± 59 | 68.8 | 8 |

| WR 268379 | 376 ± 89 | 118 ± 33 | 151 ± 36 | 166 ± 77 | 43.6d | 79.1 ± 22.8 | 185 ± 103 | 160 | 3 |

| WR 268499 | 149 ± 43 | 120 ± 12 | 101 ± 78 | 89.2 ± 51.1 | 26.6 ± 2.1 | 58.7 ± 12.0 | 137 ± 53 | 97.4 | 10 |

| WR 268648 | 178 ± 28 | 216 ± 8 | 191 ± 181 | 129 ± 118 | 24.1 ± 2.7 | 122 ± 21 | 181 ± 15 | 149 | 7 |

| WR 268658 | 66.4 ± 28.1 | 83.3 ± 24.5 | 67.3 ± 19.9 | 43.6 ± 11.4 | 16.3 ± 1.7 | 40.6 ± 35.6 | 91.4 ± 54 | 58.4 | 7 |

| WR 242511 | 77.6 ± 25.8 | 58.6 ± 40.0 | 73.4 ± 34.5 | 51.2 ± 18.1 | 23.3 ± 1.7 | 24.1 ± 14.6 | 109 ± 91 | 59.6 | 8 |

n ≥3, unless otherwise indicated.

For the seven P. falciparum clones and isolates.

Number of cross-resistant 8-aminoquinoline pairs, P <0.05.

n = 2.

The correlation matrix presented in Table 3 reveals that the seven P. falciparum clones were similarly inhibited by primaquine and its 13 8-aminoquinoline derivatives. A positively correlated and significant (0.0001 < P < 0.0073) inhibition was produced by the 13 8-aminoquinolines for each of a given pair of clones. Correlation coefficients less than 0.80 were observed only for the TM91C235-NIG59 and TM91C235-D6 pairs. This data suggests that these 13 8-aminoquinolines exert their blood stage antimalarial properties by similar mechanisms.

TABLE 3.

P. falciparum clone correlation matrixa

| Clone | Correlation with inhibition of:

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NIG59 | NIG9171 | D6 | W2 | TM91C235 | WR75-235 | TM91C40 | |

| NIG59 | 1.0 | ||||||

| NIG9171 | 0.949 (0.0001) | 1.0 | |||||

| D6 | 0.888 (0.0001) | 0.833 (0.0002) | 1.0 | ||||

| W2 | 0.911 (0.0001) | 0.972 (0.0001) | 0.871 (0.0001) | 1.0 | |||

| TM91C235 | 0.682 (0.0073) | 0.801 (0.0006) | 0.782 (0.0010) | 0.912 (0.0001) | 1.0 | ||

| WR75-235 | 0.882 (0.0001) | 0.964 (0.0001) | 0.853 (0.0001) | 0.997 (0.0001) | 0.930 (0.0001) | 1.0 | |

| TM91C40 | 0.955 (0.0001) | 0.997 (0.0001) | 0.853 (0.0001) | 0.982 (0.0001) | 0.823 (0.0003) | 0.972 (0.0001) | 1.0 |

Values are correlation coefficients, with the P values shown in parentheses.

Cross-resistance.

A second correlation matrix (data not shown) for all the drugs revealed that no cross-resistance exists between either chloroquine or mefloquine and these 13 8-aminoquinolines. Only two 8-aminoquinolines, WR 254715 r = 0.811, P = 0.027) and WR 238605 (r = 0.783, P = 0.037), correlated significantly with primaquine against blood stage parasites in culture. Of these, WR 238605 was cross resistant only with WR 254715, whereas WR 254715 was cross resistant with six other 8-aminoquinolines (Table 2). For the remaining 8-aminoquinolines, the number of cross-resistant pairs ranged between 3 and 11, suggesting the existence of multiple independent drug resistance mechanisms to 8-aminoquinolines in P. falciparum. In this regard, WR 268379 may provide a lead structure for the development of new 8-aminoquinolines should drug resistance to WR 238605 become troublesome, since WR 268379 is reasonably potent and is cross resistant to only three of the 8-aminoquinolines and not to WR 238605. WR 268379 was also the only 8-aminoquinoline tested with a 3- not a 4-methyl substituent.

Inhibition of hematin polymerization.

In contrast to the inactive primaquine prototype (14), 8 of the 13 8-aminoquinolines inhibited hematin polymerization more efficiently than did chloroquine (Table 4). Only WR 255740 and WR 259841 were relatively poor inhibitors of this process. It was also apparent that the structural specificity for inhibition of hematin polymerization was rather low. We next analyzed our data to assess whether inhibition of hematin polymerization correlated with inhibition of parasite growth in culture against the TM91C235 isolate, the parasite strain most susceptible to inhibition by these 8-aminoquinolines. For the 13 8-aminoquinolines, a modest correlation (r = 0.74, P = 0.004) between inhibition of hematin polymerization and inhibition of parasite growth was observed; the analogous correlation (r = 0.71, P = 0.007) decreased slightly if the average parasite growth IC50s were used. However, these apparent correlations were heavily biased by the data for WR 255740; if this data was omitted, no significant correlation was observed.

TABLE 4.

Inhibition of hemozoin-initiated hematin polymerization at pH 4.8

| Compound | IC50 (μM) (mean ± SD) |

|---|---|

| Chloroquine | 80 ± 20 |

| Primaquine | >2,500 |

| WR 249420 | 27 ± 3 |

| WR 251855 | 54 ± 5 |

| WR 254715 | 100 ± 3 |

| WR 238605 | 16 ± 2 |

| WR 255740 | 700 ± 80 |

| WR 255821 | 98 ± 8 |

| WR 259841 | 630 ± 35 |

| WR 266848 | 44 ± 6 |

| WR 268379 | 41 ± 6 |

| WR 268499 | 140 ± 26 |

| WR 268648 | 61 ± 24 |

| WR 268658 | 25 ± 1 |

| WR 242511 | 32 ± 6 |

Structural analysis.

By using Sybyl, models of primaquine and the 8-aminoquinolines were constructed and optimized with molecular mechanics. Subsequent molecular dynamics and MNDO (modified neglect of diatomic overlap) calculations afforded molecular parameters such as ionization potentials, dipole moments, surface potentials, bond angles, and bond distances. Correlation between these parameters and inhibition of hematin polymerization and inhibition of parasite growth were assessed. Of these, only the dihedral angle θ formed by the C-6 oxygen, the distal nitrogen (primary amine), and the C-8 nitrogen correlated (r = 0.570, P = 0.033) with observed antimalarial potencies. This data also illustrates (Table 1) that with the exception of WR 251855, the six most potent 8-aminoquinolines with IC50s between 50 and 100 nM had dihedral angles in the range of 114 to 119°.

DISCUSSION

Although alkoxy or aryloxy substituents at position 5 endowed these 13 8-aminoquinolines with impressive schizonticidal activity, the structural specificity of both parasite growth inhibition and hematin polymerization inhibition was low. Significantly, no cross-resistance was observed between either chloroquine or mefloquine and these 13 8-aminoquinolines, consistent with existing data (18, 31) on the 8-aminoquinolines primaquine, pamaquine, and WR 255448, each of which was more potent against chloroquine-resistant than chloroquine-sensitive P. falciparum strains. Apparently this lack of cross-resistance between 8-aminoquinolines and chloroquine also extends to other parasite species, as WR 238605 is an effective schizontocide against chloroquine-resistant P. vivax in Aotus monkeys (28).

Our results suggest that inhibition of hematin polymerization may play a role in the schizonticidal activity of some of these 8-aminoquinolines. However, to validate this would require a demonstration that these 8-aminoquinolines concentrate to micromolar levels in the parasite food vacuole, the organelle in which hematin polymerization takes place. This requirement is met for the diprotic weak base chloroquine and probably for other quinolines (1, 19, 21, 37) known to inhibit hematin polymerization (14). For these compounds, any correlation between inhibition of parasite growth and inhibition of hematin polymerization would likely improve (20) if differences in 8-aminoquinoline food vacuole accumulation were to be considered.

If food vacuole accumulation of 8-aminoquinolines is in part a function of their weak base properties, it is relevant to note that primaquine with pKa values of 3.2 and 10.4 (23) would, like the quinolinemethanols, bear a single positive charge at the pH of the food vacuole. Inhibition of hematin polymerization by 8-aminoquinolines may be mediated by binding to hematin μ-oxo dimer, but it is significant that primaquine does not inhibit hematin polymerization but does bind to hematin μ-oxo dimer with an affinity between that of mefloquine and quinine, suggesting that the mode of hematin binding may also be important (15).

It is also conceivable that these 13 5-alkoxy- and 5-aryloxy-substituted primaquine derivatives possess greater potency against the erythrocytic forms of the parasite than does primaquine because they exert an increased oxidative stress (5, 40). The increased metHb-forming potential of WR 238605 and WR 242511 (3) relative to that of primaquine may be diagnostic of the increased prooxidant properties of these 8-aminoquinoline derivatives. In this sense, these 8-aminoquinoline derivatives may be viewed as masked or prodrug forms of primaquine-like prooxidant metabolites (16, 17, 24).

In summary, our data provide the first evidence that certain 8-aminoquinolines active against blood stage parasites inhibit hematin polymerization. However, further studies on the localization of these compounds in the parasitized erythrocyte are needed to confirm this. The prooxidant properties of the metabolites of primaquine and other 8-aminoquinolines which seem to correlate (8) with their exoerythrocytic schizonticidal action may also contribute to their erythrocytic schizonticidal action. Because the severity of P. falciparum infections correlates with metHb levels (4), the use of 8-aminoquinolines as schizontocides could be problematic, especially in glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase-deficient individuals.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Ayo M. J. Oduola of the University of Ibadan obtained the NIG59 and NIG171 isolates from patients in Nigeria. Dennis E. Kyle of WRAIR obtained the TM91C235 and TM91C40 isolates from patients in Thailand. Constance A. Bell of WRAIR obtained the WR75-235 clone from the TM91C235 isolate. Kashinath D. Patil and Dale Mundy of the University of Nebraska Medical Center (UNMC) ran the correlation analysis of the raw data by using SAS.

The UNMC Molecular Modeling Core Facility, supported in part by NCI grant CA36727, was used for the molecular modeling experiments.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aikawa M. High-resolution autoradiography of malarial parasites treated with 3H-chloroquine. Am J Pathol. 1972;67:277–284. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allahyari R, Strother A, Fraser I M, Verbiscar A J. Synthesis of certain hydroxy analogues of the antimalarial drug primaquine and their in vitro methemoglobin-producing and glutathione-depleting activity in human erythrocytes. J Med Chem. 1984;27:407–410. doi: 10.1021/jm00369a031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anders J C, Chung H, Theoharides A D. Methemoglobin formation resulting from administration of candidate 8-aminoquinoline antiparasitic drugs in the dog. Fundam Appl Toxicol. 1988;10:270–275. doi: 10.1016/0272-0590(88)90311-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anstey N M, Hassanali M Y, Mlalasi J, Manyenga D, Mwaikambo E D. Elevated levels of methaemoglobin in Tanzanian children with severe and uncomplicated malaria. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1996;90:147–151. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(96)90118-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Atamna H, Ginsburg H. Origin of reactive oxygen species in erythrocytes infected with Plasmodium falciparum. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1993;61:231–242. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(93)90069-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Augusto O, Weingrill C L V, Schreier S, Amemiya H. Hydroxyl radical formation as a result of the interaction between primaquine and reduced pyridine nucleotides. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1986;244:147–155. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(86)90103-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baird J K, Davidson D E, Jr, Decker-Jackson J E. Oxidative activity of hydroxylated primaquine analogs. Non-toxicity to glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase-deficient human red blood cells in vitro. Biochem Pharmacol. 1986;35:1091–1098. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(86)90144-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bates M D, Meshnick S R, Sigler C I, Leland P, Hollingdale M R. In vitro effects of primaquine and primaquine metabolites on exoerythrocytic stages of Plasmodium berghei. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1990;42:532–537. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1990.42.532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8a.Bell, C. A. Personal communication.

- 9.Bhat B K, Seth M, Bhaduri A P. Recent developments in 8-aminoquinoline antimalarials. Prog Drug Res. 1984;28:197–231. doi: 10.1007/978-3-0348-7118-1_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brueckner R P, Coster T, Wesche D L, Shmuklarsky M, Schuster B G. Prophylaxis of Plasmodium falciparum infection in a human challenge model with WR 238605, a new 8-aminoquinoline antimalarial. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:1293–1294. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.5.1293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brueckner R P, Lasseter K C, Lin E T, Schuster B G. First-time-in-humans safety and pharmacokinetics of WR 238605, a new antimalarial. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1998;58:645–649. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1998.58.645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Desjardins R E, Canfield C J, Haynes J D, Chulay J D. Quantitative assessment of antimalarial activity in vitro by a semiautomated microdilution technique. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1979;16:710–718. doi: 10.1128/aac.16.6.710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dorn A, Stoffel R, Matile H, Bubendorf A, Ridley R G. Malarial haemozoin/β-haematin supports haem polymerization in the absence of protein. Nature. 1995;374:269–271. doi: 10.1038/374269a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dorn A, Vippagunta S R, Matile H, Bubendorf A, Vennerstrom J L, Ridley R G. A comparison and analysis of several ways to promote haematin (haem) polymerisation and an assessment of its initiation in vitro. Biochem Pharmacol. 1998;55:737–747. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(97)00509-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dorn A, Vippagunta S R, Matile H, Jaquet C, Vennerstrom J L, Ridley R G. An assessment of drug-haematin binding as a mechanism for inhibition of haematin polymerisation by quinoline antimalarials. Biochem Pharmacol. 1998;55:727–736. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(97)00510-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fasanmade A A, Jusko W J. An improved pharmacodynamic model for formation of methemoglobin by antimalarial drugs. Drug Metab Dispos. 1995;23:573–576. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fletcher K A, Barton P F, Kelly J A. Studies on the mechanisms of oxidation in the erythrocyte by metabolites of primaquine. Biochem Pharmacol. 1988;37:2683–2690. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(88)90263-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Geary T G, Divo A A, Jensen J B. Activity of quinoline-containing antimalarials against chloroquine-sensitive and -resistant strains of Plasmodium falciparum in vitro. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1987;81:499–503. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(87)90175-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Geary T G, Jensen J B, Ginsburg H. Uptake of [3H]chloroquine by drug-sensitive and -resistant strains of the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Biochem Pharmacol. 1986;35:3805–3812. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(86)90668-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hawley S R, Bray P G, Mungthin M, Atkinson J D, O’Neill P M, Ward S A. Relationship between antimalarial drug activity, accumulation, and inhibition of heme polymerization in Plasmodium falciparum in vitro. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:682–686. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.3.682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hawley S R, Bray P G, Park B K, Ward S A. Amodiaquine accumulation in Plasmodium falciparum as a possible explanation for its superior antimalarial activity over chloroquine. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1996;80:15–25. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(96)02655-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hiebsch R R, Raub T J, Wattenberg B W. Primaquine blocks transport by inhibiting the formation of functional transport vesicles. J Biol Chem. 1991;30:20323–20328. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hufford C D, McChesney J D, Baker J K. Assignments of dissociation constants of primaquine by 13C-NMR spectroscopy. J Heterocycl Chem. 1983;20:273–275. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Idowu O R, Peggins J O, Brewer T G, Kelley C. Metabolism of a candidate 8-aminoquinoline antimalarial agent, WR 238605, by rat liver microsomes. Drug Metab Dispos. 1995;23:1–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ittarat I, Asawamahasakda W, Meshnick S R. The effects of antimalarials on the Plasmodium falciparum dihydroorotate dehydrogenase. Exp Parasitol. 1994;79:50–56. doi: 10.1006/expr.1994.1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Milhous W K, Weatherly N F, Bowdre J H, Desjardins R E. In vitro activities of and mechanisms of resistance to antifol antimalarial drugs. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1985;27:525–530. doi: 10.1128/aac.27.4.525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nodiff E A, Chaterjee S, Mussalam H A. Antimalarial activity of 8-aminoquinolines. Prog Med Chem. 1991;28:1–40. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6468(08)70362-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Obaldia N, III, Rossan R N, Cooper R D, Kyle D E, Nuzum E O, Rieckmann K H, Shanks G D. WR 238605, chloroquine, and their combinations as blood schizonticides against a chloroquine-resistant strain of Plasmodium vivax in Aotus monkeys. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1997;56:508–510. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1997.56.508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oduola A M J, Sowunmi A, Milhous W K, Brewer T G, Kyle D E, Gerena L, Rossan R N, Salako L A, Schuster B G. In vitro and in vivo reversal of choroquine resistance in Plasmodium falciparum with promethazine. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1998;58:625–629. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1998.58.625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oduola A M J, Weatherly N F, Bowdre J H, Desjardins R E. Plasmodium falciparum: cloning by single-erythrocyte micromanipulation and heterogeneity in vitro. Exp Parasitol. 1988;66:86–95. doi: 10.1016/0014-4894(88)90053-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Peters W, Irare S J, Ellis D S, Warhurst D C, Robinson B L. The chemotherapy of rodent malaria, XXXVIII. Studies on the activity of three new antimalarials (WR 194,965, WR 228,258, and WR 225,448) against rodent and human parasites (Plasmodium berghei and P. falciparum) Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1984;78:567–579. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Peters W, Robinson B L, Milhous W K. The chemotherapy of rodent malaria. LI. Studies on a new 8-aminoquinoline, WR 238,605. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1993;87:547–552. doi: 10.1080/00034983.1993.11812809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ridley R G, Dorn A, Vippagunta S R, Vennerstrom J L. Haematin (haem) polymerization and its inhibition by quinoline antimalarials. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1997;91:559–566. doi: 10.1080/00034989760932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Slater A F G, Cerami A. Inhibition by chloroquine of a novel haem polymerase enzyme activity in malaria trophozoites. Nature. 1992;355:167–169. doi: 10.1038/355167a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Somasundaram B, Norman J C, Mahaut-Smith M P. Primaquine, an inhibitor of vesicular transport, blocks the calcium-release-activated current in rat megakaryocytes. Biochem J. 1995;309:725–729. doi: 10.1042/bj3090725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Strother A, Allahyari R, Buchholz J, Fraser I M, Tilton B E. In vitro metabolism of the antimalarial agent primaquine by mouse liver enzymes and identification of a methemoglobin-forming metabolite. Drug Metab Dispos. 1983;12:35–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sullivan D J, Jr, Gluzman I Y, Russell D G, Goldberg D E. On the molecular mechanism of chloroquine’s antimalarial action. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:11865–11870. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.21.11865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thornalley P J, Stern A, Bannister J V. A mechanism for primaquine mediated oxidation of NADPH in red blood cells. Biochem Pharmacol. 1983;32:3571–3575. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(83)90305-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vásquez-Vivar J, Augusto O. Hydroxylated metabolites of the antimalarial drug primaquine. Oxidation and redox cycling. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:6848–6854. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vennerstrom J L, Eaton J W. Oxidants, oxidant drugs, and malaria. J Med Chem. 1988;31:1269–1277. doi: 10.1021/jm00402a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]