Abstract

d-Serine, a free amino acid synthesized by serine racemase, is a coagonist of N-methyl-d-aspartate–type glutamate receptor (NMDAR). d-Serine in the mammalian central nervous system modulates glutamatergic transmission. Functions of d-serine in mammalian peripheral tissues such as skin have also been described. However, d-serine’s functions in nonmammals are unclear. Here, we characterized d-serine–dependent vesicle release from the epidermis during metamorphosis of the tunicate Ciona. d-Serine leads to the formation of a pocket that facilitates the arrival of migrating tissue during tail regression. NMDAR is the receptor of d-serine in the formation of the epidermal pocket. The epidermal pocket is formed by the release of epidermal vesicles’ content mediated by d-serine/NMDAR. This mechanism is similar to observations of keratinocyte vesicle exocytosis in mammalian skin. Our findings provide a better understanding of the maintenance of epidermal homeostasis in animals and contribute to further evolutionary perspectives of d-amino acid function among metazoans.

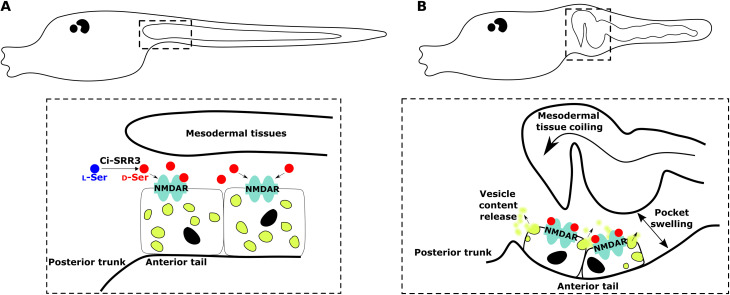

Tunicates and mammals have a shared mechanism in the regulation of epidermal vesicle release mediated by d-serine and NMDAR.

INTRODUCTION

Organisms are asymmetric in that the amino acids composing their bodies are mostly l-form, but a few exceptional d-form amino acids are present in animals and play pivotal roles in the nervous systems. d-Serine is a representative d-form amino acid that was first observed in mammals’ brains (1). Synthetized by the racemization of l-serine by serine racemase (SRR) (2), d-serine is known to be a coagonist of N-methyl-d-aspartate–type glutamate receptor (NMDAR) (3). NMDAR is composed of two GluN1 subunits and two GluN2 subunits containing d-serine/glycine and the glutamate binding sites, respectively (4, 5). Astrocytes in the central nervous system (CNS) can produce and liberate d-serine because of vesicle release in a Ca2+ concentration–dependent manner, leading to the activation of NMDARs in synapses (6, 7). Because of d-serine’s function as a neurotransmitter, a disorder of d-serine concentration is implicated in several diseases, including schizophrenia and Alzheimer’s disease (8, 9). Moreover, the activation of NMDARs leads to the flow of cations such as Na+ and Ca2+ across the cell membrane for the maintenance of homeostasis (7, 10).

In mammals, an accumulation of evidence indicates that SRR, d-serine, and NMDARs are necessary in peripheral tissues [reviewed in (11, 12)], and d-serine has been detected in kidneys, liver, corpus cavernosum, and skin. During the bone mineralization of rats, SRR is expressed in the proliferating chondrocytes, and d-serine exposure affects the chondrocytes’ maturation in cell culture (13). In mammalian skin, the presence of d-serine is concomitant with the expressions of SRR and GluNs (14, 15). Studies in mice showed that d-serine participates in keratinocyte differentiation by acting on proteins such as involucrin, K10, and TGase3 (15). In the case of skin injury, d-serine participates in homeostasis maintenance and recovery; a flux of cations mediated through NMDARs allows lamellar granule exocytosis from the keratinocytes, leading to skin permeabilization (15, 16). A misregulation of calcium dynamics in keratinocytes can lead to pathologies such as Darier’s disease and Hailey-Hailey disease (17, 18), and a better understanding of the functions of d-serine in skin is thus required.

Free d-serine has also been detected in other metazoan phyla such as insects (19), nematodes (20), and mollusks (21). In the silkworm Bombyx mori, d-serine was detected in the head, midgut, and ovary, and SRR racemization ability was also observed (22, 23). Curiously, d-serine found in the intestine of Drosophila melanogaster functions in sleep/wake regulation (24). In Caenorhabditis elegans, d-serine has a fundamental role in the activation of NMDARs, promoting dispersal behavior in conditions of starvation, facilitating the discovery of a new food source (20). d-Serine was detected in the mollusk Aplysia californica, suggesting a function in the nervous system (21). Reflecting the global presence of d-serine in metazoans, SRR homologs are encoded in various animal genomes (25). d-Serine synthesis was also identified in a nonmetazoan, the slime mold Dictyostelium discoideum, where an accumulation of d-serine following a d-serine dehydratase loss of function led to a fault in development (26). Although d-serine has crucial roles in eukaryotes, especially mammals, its functions in deuterostome species other than mammalians are largely unknown.

In the present study, we addressed the role of d-serine in the epidermis during metamorphosis of the ascidian tunicate Ciona intestinalis type A, a species in the sister group to vertebrates (27). Ciona is an ascidian with a biphasic life cycle, i.e., a sessile adult form that reproduces to give rise to a tadpole-swimming larva composed of an anterior trunk and posterior tail. A few hours after hatching, the Ciona larva settles onto a substrate and undergoes metamorphosis, leading to a juvenile stage (28), which is a miniature of the adult. The tadpole attaches to the substrate with the most anterior part of the body, the adhesive papillae, which are composed of neurons that form part of the nervous system and innervate the entire larval body along the anteroposterior axis (29, 30). The adhered larva then undergoes a succession of characterized events, including tail regression (31, 32).

Tail regression depends on apoptosis and the migration of tissues that accumulate into the most anterior part of the tail at the junction with the trunk (33–35). We have demonstrated that tail epidermal and mesodermal tissues regress by different mechanisms (36). Before the regression, a transparent space is formed between the epidermis and all other inside tissues at the anterior side of the tail near the trunk. This space enables the tail tissues to migrate independently. With the progression of tail regression, the space is enlarged to serve as a pocket that allows the arrival of migrating tissue from the tail to the trunk (36).

We reported a spontaneous mutant, tail regression failed (trf), that exhibits a defect in tail regression after settlement on a substrate (37). The causative gene of trf encodes prohormone convertase 2 (PC2), which is a peptidase that is necessary for the maturation of neuropeptides. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) is necessary for tail regression and can induce metamorphosis when administered to larvae (37, 38). A microarray analysis comparing a trf/trf mutant and wild-type larvae identified the genes targeted by PC2/neuropeptides (39). An SRR, named herein Ci-SRR3 [gene model in the genome database (40) is KH.S589.3], is encoded by a gene that is down-regulated in trf mutant, implying its role in tail regression.

In the present study, we focused on Ci-SRR3, which is expressed during tail regression. We confirmed the capacity of Ci-SRR3 to synthesize d-serine from l-serine, and we detected d-serine in metamorphosis-competent larvae. With the loss of function of Ci-SRR3 and pharmacological treatments, we show that d-serine is required to form the epidermal pocket between the Ciona trunk and tail, allowing the arrival of migrating tissues from the tail during tail regression. NMDARs appeared to be the receptors of d-serine in Ciona epidermis, inducing the release of epidermal vesicles’ content and thus leading to the formation of the pocket space. This study describes a function of d-serine in a tunicate and offers an unexpected opportunity to better understand the conserved vesicle release mechanisms as observed in mammalian skin.

RESULTS

Ciona has a functional SRR expressed during its tail regression

We confirmed that the protein encoded by KH.S589.3/Ci-SRR3 is an SRR. By conducting a BLAST (Basic Local Alignment Search Tool) search (41) of the Ciona genome with vertebrate SRR as queries, we identified two more genes that exhibit similarity to SRR. KH.C14.325, KH.C1.924, and KH.S589.3 were named Ci-SRR1, Ci-SRR2, and Ci-SRR3 according to the topology in the phylogenetic tree of SRR proteins, respectively (Fig. 1A and fig. S1). The topology is characterized by two strongly supported monophyletic groups, one containing SRR and the other with the closely related enzyme l-threonine dehydratase (SDS). Ci-SRR1 is the closest to vertebrate SRRs, while Ci-SRR2 and Ci-SRR3 branched at the base of the SRR group. The divergence of Ci-SRR3 is also suggested from the comparison of amino acid residues. Examples of these divergences are residues S84 and R135 of human SRR, which are S84T and R135T in Ci-SRR3 (fig. S1). Moreover, the three Ciona SRRs present deletions localized between amino acids 70 and 80 according to the human sequence. Duplications of Ciona SRR genes and sequence divergences accumulated during evolution could explain this topology.

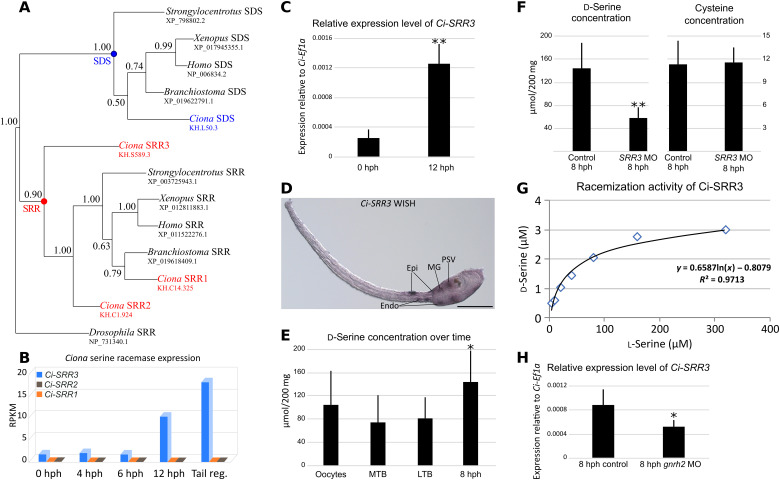

Fig. 1. Characterization of Ci-SRR3 in Ciona larvae.

(A) The phylogenetic analysis of deuterostomian SRR and its close relative SDS, made by Bayesian inference. The SRR monophyletic group includes Ci-SRR1, Ci-SRR2, and Ci-SRR3. The topology was the same when Drosophila elegans SDS (XP_017118232.1) was used as the outgroup instead of switching D. melanogaster SRR (NP_731340.1). The alignment comprised 220 amino acids. The node robustness was determined by posterior probabilities. (B) Ciona SRR expression from hatched larvae [0 hours post-hatching (hph)] to larvae with tail regression in progress (Tail reg.) according to the RNA sequencing. The Ci-SRR3 expression significantly increases over time. (C) Expression of Ci-SRR3 relative to that of Ci-Ef1α as evaluated by quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). The expression of Ci-SRR3 significantly increased during the 12 hph. (D) Expression of Ci-SRR3 in a swimming larva, as revealed by whole-mount in situ hybridization (WISH). Ci-SRR3 is expressed in the epidermis (Epi) at the anterior tail and posterior trunk, in the endoderm (Endo), motor ganglion (MG), and posterior region of the sensory vesicle (PSV). Scale bar, 100 μm. (E) d-Serine concentration assay. The concentration of free d-serine remained stable during embryogenesis from the oocyte stage to the middle tailbud (MTB) and late tailbud (LTB) stages but significantly increased in 8 hph larvae. (F) Ci-SRR3 knockdown (KD) by the antisense morpholino oligonucleotide (MO) significantly decreased the quantity of d-serine in 8 hph larvae. The results of a cysteine assay used as the control did not reveal differences between the control larvae and the Ci-SRR3 MO-injected larvae. (G) The evaluation of Ci-SRR3 racemization activity, as revealed by the in vitro assay. Ci-SRR3 is capable of synthesizing d-serine from l-serine. (H) The relative expression level of Ci-SRR3 evaluated by the quantitative RT-PCR, comparing control larvae and Ci-gnrh2 KD larvae. The knockdown of Ci-gnrh2 significantly decreased the expression level of Ci-SRR3. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

We observed a marked increase in the expression of Ci-SRR3 from hatching to the metamorphosis-competent larvae on the basis of the results of an RNA sequencing analysis (Fig. 1B). In contrast to Ci-SRR3, Ci-SRR1 and Ci-SRR2 did not show notable expression during these stages. The expression of Ci-SRR3 at the larval stage was confirmed by quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) (Fig. 1C). Using whole-mount in situ hybridization (WISH), we detected the expression of Ci-SRR3 in the posterior part of the sensory vesicle (brain), motor ganglion, epidermis, and endoderm around the junction of the trunk and tail at the larval stage (Fig. 1D).

We carried out colorimetric assays, and the results demonstrated the natural presence of d-serine in the unfertilized egg, middle tailbud embryo [stage 22 (42)], late tailbud embryo (stage 25), and 8 hours post-hatching (hph) larva, with a significant increase from the late tailbud stage to 8 hph (Fig. 1E). The presence of free d-serine in Ciona is in accord with previous research that was based on several detection methods (43). Ci-SRR3 loss of function using the antisense morpholino oligonucleotide (MO) targeting the initiation codon of this gene led to the significant reduction of d-serine at the larval stage (Fig. 1F). Therefore, Ci-SRR3 is necessary for zygotic d-serine production in Ciona larvae. We also demonstrated the ability of Ci-SRR3 to synthesize d-serine from l-serine by using a biochemical approach and recombinant Ci-SRR3 protein (Fig. 1G), although the Michaelis constant (Km) of Ci-SRR3 (approximately 160 mM) is much lower than that of human SRR (6.6 mM) (44).

The expression of Ci-SRR3 was down-regulated in the recessive mutants of the gene encoding PC2, which is necessary for the maturation of neuropeptides (39). Our earlier research also showed that GnRHs are the major peptides triggering the metamorphosis of Ciona. To determine whether Ci-SRR3 expression is regulated by GnRH, we measured the mRNA levels of this gene by quantitative RT-PCR in gnrh2 knockdown (KD) animals using an MO that had already been used successfully (Fig. 1H). The Ci-SRR3 mRNA level was reduced to 50% compared with the control animals, suggesting that the expression of Ci-SRR3 is regulated by GnRH.

d-Serine induced epidermal pocket formation

To evaluate the consequence of the absence of d-serine during Ciona tail regression, we knocked down Ci-SRR3 using an MO. We observed that a proportion of Ci-SRR3 KD larvae failed to complete tail regression, which was shown by the presence of an unabsorbed tail tip phenotype, whereas in the control, the tail regression was completed (Fig. 2, A and B). Other metamorphic events, as represented by the development of adult organs, progressed normally in Ci-SRR3–disrupted animals, which became juveniles with an unabsorbed tail tip (Fig. 2C). While tail regression was completed in the control animals, the proportion of Ci-SRR3–disrupted larvae with unabsorbed tail was significantly high (Fig. 2D). The same phenotypes were observed in Ci-SRR3 knockout (KO) larvae using transcription activator-like effector (TALE) nucleases (TALENs) (fig. S2). Slowed tail regression resulted from both the MO and TALEN methods (movies S1 and S2). The tail regression failure in Ci-SRR3–disrupted animals was ameliorated by the addition of d-serine, suggesting that Ci-SRR3 acts in the regulation of tail regression via d-serine production.

Fig. 2. Ci-SRR3 is necessary for pocket formation during metamorphosis.

(A) Control (Ctrl) and Ci-SRR3 MO-injected larvae during tail regression. Arrows indicate the pocket. (B) While tail regression (TR) was completed in the controls, a proportion of the MO-injected larvae had unabsorbed tail tip (arrow). The numbers of animals that completed the tail regression are shown in the panels. (C) A Ci-SRR3 KD juvenile exhibiting normal morphology except for the presence of the unabsorbed tail tip (arrow). (D) The proportion of larvae that completed the tail regression. The proportion was significantly lower in the MO-injected larvae compared with the controls. The addition of d-serine (d-ser) ameliorated the phenotype. (E) Wild-type larva during tail regression. The epidermis and inside tissues are separated by forming the pocket at the anterior region of the tail (arrows), a transparent space where migrating tissues coiled. Dotted lines indicate the junction between the tail and trunk. (F) Phalloidin labeling of larvae during tail regression. SRR3 MO-injected larvae did not have the pocket. The addition of d-serine led to a rescue of the pocket formation (arrows). (G) The proportion of larvae having a pocket was significantly reduced by the Ci-SRR3 MO. The phenotype was rescued by the addition of d-serine. Scale bars, 100 μm. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Our next question regarded how the tail regression became uncompleted in Ci-SRR3–disrupted larvae. Before the regression of tissues constituting the Ciona tail, the epidermis and inside tissues are separated by forming a pocket, which is a transparent space at the anterior region of the tail near the trunk (Fig. 2E) (36). The pocket allows the tail epidermis and inside tissues to migrate independently and enter into the trunk. We observed that the pocket was not formed in Ci-SRR3–disrupted larvae (Fig. 2F). The addition of d-serine led to a rescue of the pocket formation (Fig. 2, F and G, and fig. S2). In addition, when wild-type larvae that did not adhere to the substrate and therefore did not start metamorphosis were treated with d-serine, they formed a pocket between the epidermis and inside tissues at the anterior region of the tail (Fig. 3, A and B). The precociously induced pocket appeared mostly at the anterior region of the tail near the junction between the tail and trunk, where the pocket is formed during metamorphosis (Fig. 3C). Therefore, d-serine can induce pocket without the initiation cues for starting metamorphosis.

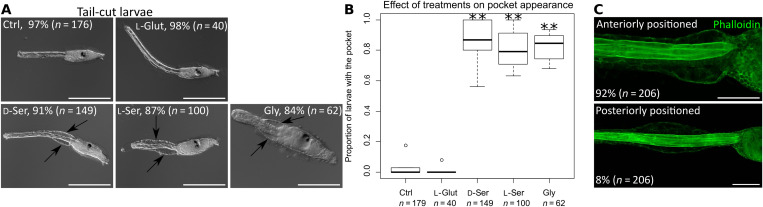

Fig. 3. d-Serine induces pocket formation without initiating metamorphosis.

(A) Treatments with d-serine (d-Ser), l-serine (l-Ser), and glycine (Gly) led to the formation of the pocket (arrows) in wild-type larvae that did not adhere to the substrate and therefore did not start metamorphosis. Glut, l-glutamate. (B) The effects of neurotransmitters on the induction of the pocket. (C) Phalloidin labeling exhibited the pocket induced by d-serine. The pocket can be anteriorly or posteriorly positioned. Most of the pockets induced by d-serine were positioned at the most anterior part of the tail. Scale bars, 200 μm (A) and 50 μm (C). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

We also observed that l-serine (which we used as the negative control) could induce pocket formation. We realized that the inhibitory neurotransmitter glycine also had this activity (Fig. 3) (39). d-Serine is thus not a unique agent in pocket formation but, nonetheless, is the primal factor regulating this process during metamorphosis endogenously, as the phenotypes of Ci-SRR3 KO/KD larvae suggested.

The epidermal pocket is formed by vesicle release from epidermal cells

We hypothesized that a cellular fluid causes pocket filing, leading to its swelling. To test this, we exposed larvae to brefeldin-A, a chemical that has been used in Ciona and is known to inhibit the secretory pathway by preventing homeostasis of the endoplasmic reticulum (45). In our present experiment, brefeldin-A blocked pocket formation in settled larvae during tail regression (Fig. 4A) and prevented the completion of this event (Fig. 4B). The formation of a precocious pocket under d-serine treatment in nonsettled larvae was also inhibited by brefeldin-A (Fig. 4C). Ciona epidermal cells contain many vesicles (Fig. 4D), and we hypothesized that the increase in pocket size may be due to release of vesicle content from epidermal cells.

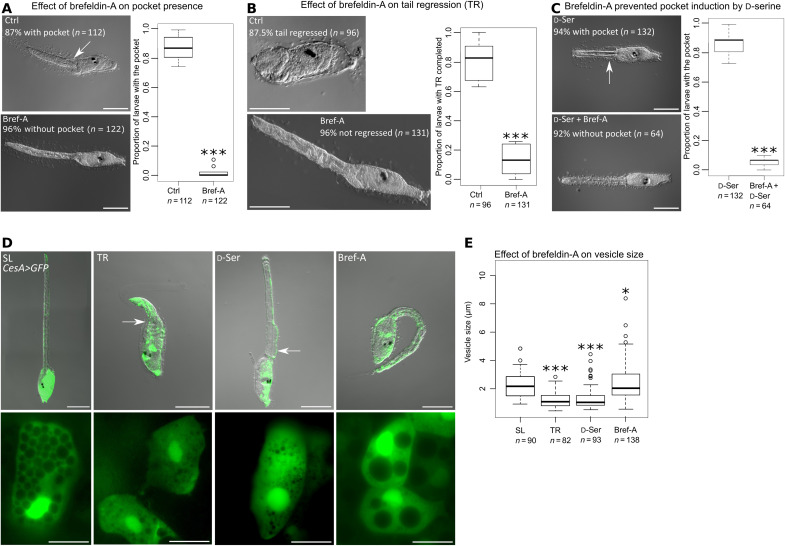

Fig. 4. The pocket is formed by the vesicle release from epidermal cells.

(A) Brefeldin-A (Bref-A) significantly prevented pocket (arrow) formation during tail regression (TR). (B) Brefeldin-A suppressed the completion of tail regression. (C) The formation of the pocket under d-serine treatment in nonsettled larvae was inhibited by brefeldin-A. (D) Visualization of epidermal vesicles in CesA>GFP electroporated larvae. Epidermal cells from the anterior tail of a swimming larva (SL) contained numerous large vesicles. During tail regression, epidermal cells surrounding the pocket (arrows) exhibited great reductions in vesicle size and number. When the pocket was induced by d-serine, the epidermal vesicles exhibited the same characteristics as the larvae during tail regression. Brefeldin-A–treated larvae presented large epidermal vesicles. (E) Measurement of the epidermal vesicle size. Compared with the swimming larvae, the larvae with tail regression in progress and under d-serine treatment had smaller vesicles. Conversely, the brefeldin-A–treated larvae exhibited larger vesicles. Scale bars, 100 μm (A to D, top) and 20 μm (D, bottom). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

To investigate the origin of the pocket fluid, we focused on Sar1, a GTPase (guanosine triphosphatase) implicated in vesicle formation, transfer, and exocytosis in Ciona (45, 46). We expressed the dominant negative form of Sar1 (dnSar1) driven by tissue-specific promotors to identify the tissue(s) that supply the fluid. In larvae in which dnSar1 was expressed specifically in the epidermis (with the aid of Ci-CesA cis element), no pocket was formed even though the larvae were treated with d-serine, arguing in favor of an epidermal origin of the fluid (fig. S3). Confirming this finding, dnSar1 overexpression in the endoderm, muscle, and notochord did not inhibit pocket formation.

The overexpression of enhanced GFP (green fluorescent protein) in the epidermal cells highlighted the vesicles in the epidermis. In the swimming larvae, we noted numerous well-distinguished vesicles in the tail epidermal cells (Fig. 4D). During tail regression, epidermal cells contracted along the anterior-posterior axis (36). At this stage, epidermal cells exhibited a marked reduction in the area occupied by the vesicles (Fig. 4D). When nonsettled larvae exposed to d-serine formed the pocket without starting other metamorphic events, they exhibit the same reduction of vesicle areas in the epidermis. Curiously, the vesicles were enlarged in larvae exposed to brefeldin-A during tail regression.

On the basis of that observation, we next measured the vesicle size between conditions (Fig. 4E). Compared with the swimming larvae, the larvae with tail regression in progress and the nonsettled larvae exposed to d-serine had smaller vesicle sizes, suggesting the release of their contents in the intercellular space forming the pocket. Conversely, brefeldin-A–treated larvae exhibited larger vesicles, suggesting that this agent blocked the exocytosis of vesicles by promoting intracellular vesicle fusions.

In Ciona, the tail and trunk epidermal cell lineages are already separated at the eight-cell stage (47). It is known that a4.2 cells give rise to trunk epidermal cells, whereas b4.2 cells differentiate into tail epidermal cells. To validate the specificity of d-serine’s action on tail versus trunk epidermal cells, we isolated the a4.2 and b4.2 cells from eight-cell embryos after the electroporation of CesA>GFP (fig. S4) and then added d-serine. The number of vesicles counted after one night of d-serine exposure revealed no difference from the a4.2 daughter cells that were not administered d-serine, whereas the tail epidermal cells coming from b4.2 cells presented significantly lower numbers of vesicles in the treated condition (fig. S4). This result argues in favor of a specific targeting of epidermal cells in the tail by d-serine to restrict the position of the pocket at the tail region.

NMDAR is the receptor of d-serine for epidermal pocket formation

Our next question concerned how d-serine influences the tail epidermis. NMDAR is the most likely candidate to mediate d-serine’s effects in the epidermis, because glycine, the coagonist of d-serine that binds to the same site of this receptor, can induce pocket formation when administered to unsettled larvae. Vertebrate NMDARs are the heterodimers of GluN1 and, usually, GluN2. Two genes encoding the subunits of NMDARs (Ci-GluN1 and Ci-GluN2) have been identified in the Ciona genome (48). Using BLAST and phylogenetic analyses, we unambiguously confirmed the previous findings that Ci-GluN1 and Ci-GluN2 are the orthologs of vertebrate GluN1 and GluN2, respectively (figs. S5 and S6). We were unable to identify the gene encoding the protein orthologous to vertebrate GluN3 subunit from the Ciona genome. In situ hybridization allowed the detection of Ci-GluN1 and Ci-GluN2 in the CNS and the epidermis (Fig. 5A). Ci-GluN1 showed broad expression in the tail epidermis, and the expression of Ci-GluN2 was strong at the most anterior part of the tail. These expression patterns, particularly those of Ci-GluN2, are similar to that of Ci-SRR3.

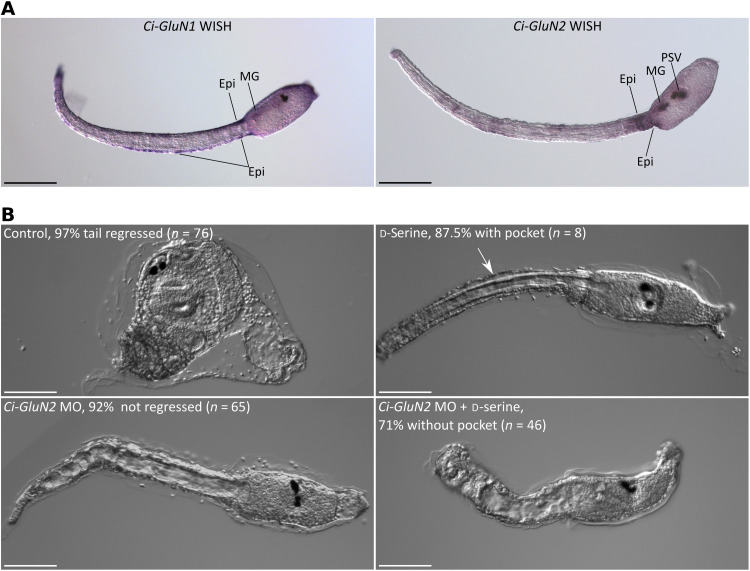

Fig. 5. NMDAR is the receptor of d-serine for epidermal pocket formation.

(A) The expression patterns of Ci-GluN1 and Ci-GluN2 at the larval stage, as revealed by WISH. Ci-GluN1 is expressed in the tail epidermis (Epi) and motor ganglion (MG). Ci-GluN2 is expressed in the anterior tail epidermis, motor ganglion, and posterior region of the sensory vesicle (PSV). (B) Ci-GluN2 MO blocked tail regression and prevented pocket formation. d-Serine failed to induce the pocket in Ci-GluN2 MO-injected larvae. Scale bars, 100 μm.

We exposed settled larvae to three well-known NMDAR inhibitors: the glutamate site inhibitor D-AP5, the glycine site inhibitor 7-clrorokynurenic acid, and the NMDAR Ca2+ channel inhibitor MK-801 (49). All three reduced the appearance of the epidermal pocket in larvae with tail regression in progress (fig. S7, A and B). Addition of d-serine did not significantly rescue the absence of the pocket. The NMDAR inhibitor that exerted the strongest effect, MK-801, blocked the completion of tail regression (fig. S7C). When swimming larvae settled and underwent tail regression under MK-801 treatment, the use of this inhibitor led to an arrest of tail regression at about halfway through the process; this halt in regression was caused by an arrest at the entrance of the mesodermal tissues into the pocket (fig. S8). As a result, the notochord and muscle were blocked, with a large portion remaining in the tail. Using MK-801, we also confirmed that blocking the NMDARs resulted in the enlargement of vesicles in the epidermal cells, which is similar to the effect observed in brefeldin-A treatment (fig. S7, D and E).

To further investigate the necessity of NMDAR in pocket formation, we suppressed the translation of Ci-GluN2 with an antisense MO. The Ci-GluN2 morphants did not develop a pocket, and they finally failed to complete tail regression (Fig. 5B). Moreover, Ci-GluN2 morphants did not respond to exogenously administered d-serine, confirming that d-serine induces pocket formation and subsequent tail regression via NMDAR.

DISCUSSION

Metamorphosis in Ciona progresses by a relay of multiple signaling molecules, each of which orders specific changes in its target tissue. The results of the present study demonstrated that d-serine is responsible for the induction of a metamorphic event of the ascidian Ciona (Fig. 6). Unlike its well-known roles in the brains of mammals, d-serine in Ciona promotes the exocytosis of vesicles in the tail epidermal cells. The epidermal exocytosis is necessary to form the pocket space that accepts regressing tail tissues. The function of d-serine in the regulation of extracellular matrix secretion has been demonstrated in mammalian skin, implicating the evolutionary history of the d-amino acid in the chordate lineage.

Fig. 6. Mechanisms of the epidermal pocket formation during Ciona tail regression.

(A) d-Serine is synthetized by Ci-SRR3 from l-serine. At the beginning of tail regression, the NMDA receptors from epidermal cells at the most anterior part of the tail are activated by d-serine. (B) During tail regression, activation of NMDA receptors led to the release of the epidermal cell vesicle content toward the extracellular matrix. Accumulation of vesicle content intro extracellular matrix allows separation between epidermis and inside tissues. Concomitantly, epidermal tissues swell, creating an empty space for welcoming of migrating tissues that start to coil. In dotted squares, epidermal cells are intentionally not to scale to show in-depth mechanism.

SRR is expressed and functional during tail regression of an ascidian

Among the three SRRs encoded in the Ciona genome, only Ci-SRR3 is expressed during tail regression. This enzyme has an atypical amino acid sequence and is suspected to have diverged in the ascidian lineage. Gene duplications allow organisms to evolve a new function or to subfunctionalize existing roles. The role of Ci-SRR3 in metamorphic events, which is characteristic to ascidians, could be an example of the co-option/subfunctionalization. The lower racemization rate of Ci-SRR3 compared with that of mammal SRR may be explained by compatibility of the assay system used in this study (50). Sequence divergence could also be the cause: Three amino acids (K56, S84, and R135) are crucial for the racemization process according to human sequences (fig. S1) (50). In Ci-SRR3, K56 is conserved, whereas the other sites are mutated as S84T and R135T. It has been shown that S84T mutation in human SRR significantly decreases its enzymatic efficiency but does not block racemization capacity (51). That study also suggested that R135 of human SRR is important in controlling the substrate preference. Because we observed that Ci-SRR3 KD resulted in a significant decrease in d-serine at the larval stage, the racemization of Ci-SRR3 in vivo may be more efficient than in an in vitro assay, suggesting that there is a mechanism that supports this enzyme in Ciona.

d-Serine functions in the pocket formation via NMDAR

Our genetic analysis results suggested that NMDAR is the receptor of d-serine for pocket formation. NMDAR is known to respond to various neutral amino acids (52, 53); this is consistent with our finding that both l-serine and glycine can induce pocket formation. However, d-serine is primarily used in vivo in this process, as demonstrated by Ci-SRR3 loss of function, resulting in the absence of a pocket. We did not observe an effect of l-glutamate on pocket formation, a paradoxical result according to the binding properties of NMDAR in vertebrates. The amino acid sequence of Ciona NMDAR subunits could explain this paradox. In humans, the success of glutamate binding to GluN2 depends on its E413, K485, S512, R519, S690, and T691 residues (47). Ciona GluN2 has K485R mutation (fig. S6). Mutation K485E in human GluN2 leads to a complete loss of the ability of glutamate to bind to NMDAR without affecting glycine binding (54). K485R substitution in Ciona GluN2 could be responsible for the glutamate binding incapacity.

The binding pocket of d-serine/glycine of human GluN1 is formed by T514, S688, and D732 (fig. S6). Ciona GluN1 conserves D732; however, S688 is mutated to an A, and T514 is mutated to an S. Earlier research indicated that glycine-binding affinity seems less sensitive to these mutations, and, especially, mutation S688A in humans did not greatly affect the glycine binding (54). Recent investigations revealed that in vertebrates, a heterodimer of GluN1 and GluN3 can unexpectedly generate excitation without glutamate (55, 56). It is the association of GluN3A/B with the glycine/d-serine binding subunit GluN1 that allows the activation of the receptor exclusively by glycine/d-serine. Fundamentally, this finding suggests that some functions of NMDARs can be glutamate independent, which could explain our present observation of the absence of an effect of glutamate on the epidermal pocket formation in Ciona. In light of the loss of GluN3 and in contrast to the scenario in vertebrates, we speculate that the glutamate independence in Ciona NMDARs is due to both GluN1 and glutamate-insensitive GluN2, which is a hypothesis supported by the amino acids’ sequence composition.

Lineage-specific responsiveness of epidermis to d-serine

The process of Ciona tail regression is divided into the coiling of mesoderm actomyosin-dependent cellular shortening and invagination of the epidermis. The different movements of the epidermis and inside tissues are enabled by the separation of these tissues before regression, which is achieved by the initial step of pocket formation. The other function of the pocket is to make space to accept tail tissues during their regression, making the pocket a reception structure.

We observed that the pocket is formed at the anterior tail region, but not at the posterior trunk, confirming the preponderant function of tail epidermis for tail regression. Our results demonstrated that tail but not trunk epidermal cells have the capability to respond to d-serine to release fluid from the vesicles. In accord with this finding, we observed a major expression domain of Ci-GluN1 and Ci-GluN2 at the anterior region of the tail epidermis. This lineage specificity is a plausible mechanism to restrict the position of the pocket. Because the paths that the trunk and tail epidermis follow become completely different via metamorphosis, we suspect that their regional specifications, as exemplified by different gene expressions, are strictly regulated by gene regulatory networks. The characterization of the key molecules responsible for epidermal specification is an interesting topic for a better understanding of how d-serine responsiveness is restricted to the tail epidermis and for investigating how the position of the pocket is determined.

Conservation of the epidermal vesicle release system between Ciona and mammals

This study characterized the epidermal morphological process dependent on d-serine in a tunicate, the closest relative to vertebrates. Strong parallels can be drawn with the system in mammalian epidermis.

The main function of the epidermis is to protect the body from the environment, conserving the body’s integrity; this makes the recovery capacity of the epidermis and homeostasis maintenance crucial. In mammals, the epidermis is formed by the stratum granulosum, with keratinocytes containing both keratohyalin and lamellar granules, upon which the external layer, the stratum corneum, is present. SRR KO mice exhibit a delay in skin recovery, reduced barrier function, and an alteration of skin permeability, suggesting that d-serine is implicated in skin homeostasis. Moreover, the keratohyalin vesicles become larger in SRR KO mice, suggesting an accumulation of the vesicles’ content without release in the case of a reduction in the d-serine concentration (15).

These phenomena are quite similar to our observations in Ciona, where d-serine promotes pocket formation via the regulation of vesicle release from the epidermis. Lamellar granules are implicated in the skin permeability because of their exocytosis, which is controlled by ion flux, notably calcium and potassium (57). Exposure to calcium-containing solutions delays exocytosis and skin recovery (57). This cation flux passing through receptors such as those for GABA (γ-aminobutyric acid) and glutamate maintains the skin’s homeostasis (14, 16, 51, 58). Similar to MK-801 blocking pocket formation during tail regression in Ciona, MK-801 prevents epidermal hyperplasia in mouse (14, 57), suggesting that exocytosis controlled by NMDAR is a common feature between Ciona and mammals.

Taking the phylogenetic relationship between tunicates and vertebrates into consideration, we speculate that the role of d-serine/NMDARs in the regulation of epidermal exocytosis was already acquired by the common ancestor of vertebrates/tunicates before their divergence. In Ciona, whose epidermis is simply a monolayer of cells surrounded by the tunicate-specific cellulose-containing tunic (59), this signaling pathway is used in the regulation of the extracellular matrix during metamorphosis via the duplications of SRR genes. Because mammals have a single SRR gene in their genome, the function of this gene in the regulation of homeostasis probably reflects its ancient role inherited from the ancestor. Gaining a more extensive understanding of the functions of d-serine/NMDARs in other vertebrates and deuterostomes will provide clues to the evolutionary history of this signaling in chordates.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Gene identifications and phylogenetic analysis

We performed Blastn and Blastx (48) searches against the genome of Ciona using the amino acid sequences of human SRR, GluN1, and GluN2A-D subunits as queries followed by a reciprocal BLAST search. We aligned all amino acid sequences from the open reading frame (ORF) by using MAFFT 7 software (60) and deleted the background with Gblocks 0.91b (61). The phylogenetic analysis was performed with MrBayes 3.1.2 (62) using the mixed model. Node robustness corresponds to posterior probabilities.

Animals

C. intestinalis wild types collected from Onagawa Bay (Miyagi, Japan) and Onahama Bay (Fukushima, Japan) were cultivated in closed colonies by the National BioResource Project, Japan. They were kept under a constant light condition to prevent the release of gametes. Eggs and sperms were collected surgically from gonadal ducts, and insemination was carried out in dishes.

To obtain synchronized settled larvae, we distributed swimming larvae in new dishes after hatching. When the majority of the larvae attached to the wall of dishes, the remaining unadhered larvae were discarded by exchanging the seawater. In this manner, each sample was composed of larvae with a synchronized timing of settlement. To prevent the larvae from settling, we cut the posterior half of the tail with a scalpel and distributed the tail-amputated larvae in 2% agar-coated dishes. The removal of the tail prevents larvae from swimming efficiently, and these larvae are usually unable to maintain their adhesion to the substrate. Covering the dishes with agar reduces the success of adhesion, perhaps because the hardness of the substrate is reduced by doing so.

Amino acid assay

We used the d-serine Colorimetric Assay Kit (CT-DSG-K01; Cosmo Bio, Tokyo) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, except that the final mixture was composed of 40 μl of reaction mix and 20 μl of sample. Samples were obtained by manually crushing 80 to 120 mg of larvae in 100 μl of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The acquired results were normalized to obtain the concentration for 100 mg of larvae. Colorimetric lecture was made with 2 μl of solution using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer. The cysteine concentration was determined with the Cysteine (Cys) Assay Kit (E-BC-K352; Elabscience Biotechnology, Wuhan, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Constructs

The cDNAs of Ci-SRR3, Ci-GluN1, and Ci-GluN2 were PCR amplified with proofreading PrimeStar HS DNA polymerase (Takara Bio, Shiga, Japan) with the primers 5′-ctgcaggaattcgatttacatagcaatggcgttaaac-3′ and 5′-atcgataagcttgattattacgtagtttagtttgctc-3′, 5′-ctgcaggaattcgatgtgccagagtgattggaatag-3′ and 5′-atcgataagcttgatattcctctttcttttataaacc-3′, and 5′-ctgcaggaattcgatttgaatttgactccatatctaa-3′ and 5′-atcgataagcttgattaattctaaaacaacccttcgg-3′. The PCR products were subcloned into the Eco RV site of pBluescript SKII (+) with In-Fusion HD Cloning kit (Clontech, Mountain View, CA, USA) and were used for digoxigenin-labeled probe synthesis for in situ hybridization. The cDNA of Ciona Sar1 was PCR amplified with PrimeStar HS DNA polymerase with the primers 5′-cccaggaccagaattctataaactattcgaatggttt-3′ and 5′-cgctcagctggaattcttatatgtactgtgcgagc-3′, and the PCR fragment was subcloned into the Eco RI site of a pSP-mCherry::2A vector. pSP-mCherry::2A::Sar1 was subjected to inverse PCR with the primers 5′-caatgcaggaaaaaacacgttgcttcatatgcttaagg-3′ and 5′-catatgaagcaacgtgttttttcctgcattgtcaaggcc-3′ to make a dominant negative as described (53). The cis elements for tissue-specific expressions were inserted into the Not I site of pSP-mCherry::2A::dnSar1. The official names of the cis elements according to the nomenclature rule (63) are as follows: Ciinte.REG.HT2019.C12.26334-27222 for Bra, Ciinte.REG.HT2019.C7.3406860-3409026 for CesA, Ciinte.REG.HT2019.C10.5161612-5163679 for Titf1, and Ciinte.REG.HT2019.C11.3012139-3013022 for TnI. The full-length ORF of Ci-SRR3 was amplified by PCR with PrimeStar HS DNA polymerase with the primers 5′-gtggtggtggtgctccccaacggtcaacaactttct-3′ and 5′-gatatacatatggctatggcgttaaacaaagaccct-3′. The PCR product was subcloned between the Nhe I and Xho I sites of pET21a (Novagen, Darmstadt, Germany). The CesA>GFP construct was described previously (64).

TALEN pairs that target the middle part of the coding region of Ci-SRR3 were constructed on the TALEN backbone vector that had the EF1α cis element and mCherry provided by the Golden Gate method based on previous reports (65, 66). The target sites of the TALENs were determined using the TAL Effector Nucleotide Target 2.0 (67). pEF1a>SRR3 TALEN::2A::mCherry vectors were electroporated into one-cell embryos. At the larval stage, genomic DNA was isolated from the animals that exhibited a bright expression of mCherry. The genomic region targeted by the TALENs was amplified with the primers 5′-ctgcaggaattcgatcactgcatctactgggaatc-3′ and 5′-atcgataagcttgatctacctatatttcgccttacg-3′.

The PCR products were subcloned into the Eco RV site of pBluescript SKII (+), and the cloned fragments were subjected to a sequence analysis by the conventional Sanger method to determine the introduction of mutations. The assembled TALEN repeats were subcloned into the pHTB backbone vector for in vitro mRNA synthesis (68, 69). Detailed methods of the construction are downloadable at the website http://marinebio.nbrp.jp/ciona/.

Racemization activity assay

Recombinant Ci-SRR3 protein was expressed in Escherichia coli Origami B (DE3) strain (Novagen). For protein purification, cells were suspended in lysis buffer [20 mM tris (pH 8.0), 100 mM NaCl, and 20 mM imidazole] and sonicated. Lysates were clarified by centrifugation at 35,000g, after which the supernatant was filtered (0.45 μm). The protein was purified using a HisTrap FF column (GE Healthcare, Buckinghamshire, UK). The in vitro assay of the racemization of serine was conducted as described (70).

Pharmacological treatments

d-Serine (191-08821; FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corp., Tokyo), l-serine (191-00401, FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corp.), l-glutamate acid (070-00502, FUJIFILM Wako), and glycine (077-0073, FUJIFILM Wako) were stocked in fresh water at 100 mM at −30°C and used at the final concentration of 50 μM. D-AP5 (015-18481, FUJIFILM Wako) was stocked in 100 mM NaOH at −30°C and used at the final concentration of 100 μM. MK-801 (0924; Tocris Bioscience, Bristol, UK), 7-chlorokynurenic acid (ab120024; Abcam, Cambridge, MA), and brefeldin-A (022-15991, FUJIFILM Wako) were stocked in dimethyl sulfoxide at −30°C at 25 mM, 50 mM, and 10 μg/μl, respectively, and used at the final concentrations of 100 μM, 700 μM, and 2 μg/μl, respectively. Chemicals were administered at the settlement of larvae or after tail cutting.

Statistical analyses and imaging

Differences between conditions were evaluated by both the Wilcoxon Mann-Whitney test and Fisher’s exact test for larval compatibility. Effects were considered significant with a P value <0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using the software R 2.14.1. Photographs and time-lapse images were taken with an AxioImager Z1 and AxioObserver Z1 (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging, Jena, Germany). Images were treated with AxioVision Rel.4.6 and ImageJ. The notation of the P value is as follows: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001.

Phalloidin staining

Staining was conducted as described (36, 39) with a few modifications. Larvae were fixed in 3.8% formaldehyde in seawater for 10 min at room temperature. After two washes in PBST (PBS with Tween 20), larvae were washed in 0.5 M NaCl, 0.1 M tris-Cl (pH 8.0), and 0.1% Tween 20 solution for 10 min. The same solution was next used for phalloidin incubation for 15 min.

In situ hybridization

In situ hybridization was performed as described (71). Three modified points were the larvae fixation by 3.8% formaldehyde in seawater for 1 to 7 days at 4°C, the application of proteinase K at 5 to 20 μg/ml concentration for 30 min at 37°C, and hybridization at 42°C for 3 days. Larvae used for in situ hybridization were microinjected with the antisense MO or electroporated with the expression vector of the TALENs for Ci-CesA to remove tunics that would otherwise cause a high background of signal (69).

Microinjection and electroporation

Unfertilized eggs were dechorionated in sterilized seawater containing 1% sodium thioglycolate and 0.05% actinase E as described (35). Microinjection and electroporation were performed as described (72–74). The microinjection solution included 500 ng/μl of each TALEN mRNA for KO and 0.5 to 0.25 mM morpholinos for KDs. The sequences of the MOs were as follows: 5′-gggucuuuguuuaacgccauugcua-3′ for Ci-SRR3, and 5′-aucuuuucaucaacccaauuucaug-3′ for Ci-GluN2. The MOs for Ci-CesA and Ci-gnrh2 were reported (39, 64).

To label specific tissues in vivo, we added 2 to 3 ng/μl of a linearized plasmid to the injection mixture (Ci-Bra>Kaede for notochord, Ci-Titf>Kaede for endoderm, and Ci-TnI>Kaede for muscle). We conducted the electroporation with 60 μg for all plasmids’ constructs, except for the electroporation of pFOG>CesA TALEN L1 and R1 with a total of 80 μg.

Quantitative RT-PCR

Real-time PCR was performed with the TB Green Premix DimerEraser (RR091, Takara Bio). We used Ci-Ef1α as a reference gene as described (75). The standard was made with a known quantity of purified plasmid containing the ORF or the PCR product. The primers used for the quantitative analyses were 5′-tcactgcatctactgggaatc-3′ and 5′-gttttgcagctgaagcattcg-3′.

RNA sequencing

Total RNA was collected from larvae just after they hatched (0 hph) and at 4, 6, and 12 hph and at the tail regression–completed stage with ISOGEN (FUJIFILM Wako) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. A 0.5-μg aliquot of collected total RNA from each sample was used to construct cDNA libraries using the TruSeq Stranded mRNA Sample Preparation Kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The resulting cDNA library was validated using a Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) with a DNA 1000 chip and quantified using the Cycleave PCR Quantification Kit (Takara Bio).

Paired-end sequencing over 101 cycles was performed using a HiSeq1500 system (Illumina) in the rapid mode. Total reads were extracted with CASAVA version 1.8.2 genetic analysis software (Illumina). Adaptor sequences and low-quality reads were then removed from the extracted reads with the use of the tool Trimmomatic (76). Cleaned sequences of each sample were aligned to the KH model of the C. intestinalis genome (http://ghost.zool.kyoto-u.ac.jp/cgi-bin/gb2/gbrowse/kh/) using Tophat version 2.0.14 (77) with default parameters. The gene expression of each respective sample was calculated as the reads per kilobase per million mapped reads (RPKM) with the program Cufflinks version 2.0.10 (78).

Acknowledgments

We thank the members of the Shimoda Marine Research Center at the University of Tsukuba for maintenance of the animals, and S. Fujiwara, M. Yoshida, Y. Satou, C. Imaizumi, S. Aratake, A. Yoshikawa, R. Nozawa, R. Yoshida, and all of the members of the Department of Zoology, Kyoto University, the Misaki Marine Biological Station, the University of Tokyo, the Maizuru Fishery Research Station of Kyoto University, and the National BioResource Project (NBRP) for the cultivation and provision of Ciona adults and experimental materials. We thank T. Yamamoto and T. Sakuma for helping us with the TALEN construction. We are grateful to A. Nishino for support of this study. We thank H. Horkan for useful comments. We thank A. Sakamoto for technical help.

Funding: This study was supported by grants from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science to H.M. (18K06888), T.H. (19H03204, 21K19249, and 21H05239), and Y.S. (16H04815 and 19H03262), and the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science postdoctoral fellowship to G.K. (PE19712). This study was also supported by the Toray Science Foundation and Japan Science and Technology Agency FOREST Program (grant JPMJFR2054) and CRCNS 2021 to T.H.

Author contributions: Y.S. managed the project. G.K. performed the amino acids assay, statistical analyses, phylogenetic analysis, staining, imaging, and real-time PCR. G.K., A.H., and Y.S. performed chemical treatments, loss of function experiments, and in situ hybridizations with assistance from T.H. T.Y., T.O., and H.M. performed the racemization activity assay. M.H., A.S., and H.S. analyzed expression profiles. G.K. and Y.S. wrote the manuscript.

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials. The read sequences for RNA sequencing have been deposited in the Sequence Read Archive database under the accession numbers SRR16114570–SRR16114593 (PRJNA767259). The plasmids and wild-type Ciona can be provided by the NBRP Japan pending scientific review and a completed material transfer agreement. Requests for the plasmids and wild-type Ciona should be submitted to NBRP Japan.

Supplementary Materials

This PDF file includes:

Figs. S1 to S8

Other Supplementary Material for this manuscript includes the following:

Movies S1 and S2

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Hashimoto A., Nishikawa T., Hayashi T., Fujii N., Harada K., Oka T., Takahashi K., The presence of free D-serine in rat brain. FEBS Lett. 296, 33–36 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wolosker H., Sheth K. N., Takahashi M., Mothet J. P., Brady R. O., Ferris C. D., Snyder S. H., Purification of serine racemase: Biosynthesis of the neuromodulator D-serine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 721–725 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mothet J. P., Parent A. T., Wolosker H., Brady R. O., Linden D. J., Ferris C. D., Rogawski M. A., Snyder S. H., D-serine is an endogenous ligand for the glycine site of the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 4926–4931 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Matsui T., Sekiguchi M., Hashimoto A., Tomita U., Nishikawa T., Wada K., Functional comparison of D-serine and glycine in rodents: The effect on cloned NMDA receptors and the extracellular concentration. J. Neurochem. 65, 454–458 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Priestley T., Laughton P., Myers J., Le Bourdellés B., Kerby J., Whiting P. J., Pharmacological properties of recombinant human N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors comprising NR1a/NR2A and NR1a/NR2B subunit assemblies expressed in permanently transfected mouse fibroblast cells. Mol. Pharmacol. 48, 841–848 (1995). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oliet S. H. R., Mothet J.-P., Regulation of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors by astrocytic D-serine. Neuroscience 158, 275–283 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schell M. J., Molliver M. E., Snyder S. H., D-serine, an endogenous synaptic modulator: Localization to astrocytes and glutamate-stimulated release. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 92, 3948–3952 (1995). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Madeira C., Lourenco M. V., Vargas-Lopes C., Suemoto C. K., Brandão C. O., Reis T., Leite R. E. P., Laks J., Jacob-Filho W., Pasqualucci C. A., Grinberg L. T., Ferreira S. T., Panizzutti R., d-serine levels in Alzheimer’s disease: Implications for novel biomarker development. Transl. Psychiatry. 5, e561 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wolosker H., Panizzutti R., De Miranda J., Neurobiology through the looking-glass: D-serine as a new glial-derived transmitter. Neurochem. Int. 41, 327–332 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cline H. T., Tsien R. W., Glutamate-induced increases in intracellular Ca2+ in cultured frog tectal cells mediated by direct activation of NMDA receptor channels. Neuron 6, 259–267 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Montesinos Guevara C., Mani A. R., The role of D-serine in peripheral tissues. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 780, 216–223 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wolosker H., Mori H., Serine racemase: An unconventional enzyme for an unconventional transmitter. Amino Acids 43, 1895–1904 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Takarada T., Takahata Y., Iemata M., Hinoi E., Uno K., Hirai T., Yamamoto T., Yoneda Y., Interference with cellular differentiation by D-serine through antagonism at N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors composed of NR1 and NR3A subunits in chondrocytes. J. Cell. Physiol. 220, 756–764 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fuziwara S., Inoue K., Denda M., NMDA-type glutamate receptor is associated with cutaneous barrier homeostasis. J. Invest. Dermatol. 120, 1023–1029 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Inoue R., Yoshihisa Y., Tojo Y., Okamura C., Yoshida Y., Kishimoto J., Luan X., Watanabe M., Mizuguchi M., Nabeshima Y., Hamase K., Matsunaga K., Shimizu T., Mori H., Localization of serine racemase and its role in the skin. J. Invest. Dermatol. 134, 1618–1626 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Denda M., Fuziwara S., Inoue K., Influx of calcium and chloride ions into epidermal keratinocytes regulates exocytosis of epidermal lamellar bodies and skin permeability barrier homeostasis. J. Invest. Dermatol. 121, 362–367 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hu Z., Bonifas J. M., Beech J., Bench G., Shigihara T., Ogawa H., Ikeda S., Mauro T., Epstein E. H., Mutations in ATP2C1, encoding a calcium pump, cause Hailey-Hailey disease. Nat. Genet. 24, 61–65 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sakuntabhai A., Ruiz-Perez V., Carter S., Jacobsen N., Burge S., Monk S., Smith M., Munro C. S., O’Donovan M., Craddock N., Kucherlapati R., Rees J. L., Owen M., Lathrop G. M., Monaco A. P., Strachan T., Hovnanian A., Mutations in ATP2A2, encoding a Ca2+ pump, cause Darier disease. Nat. Genet. 21, 271–277 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Corrigan J. J., Srinivasan N. G., The occurrence of certain D-amino acids in insects. Biochemistry 5, 1185–1190 (1966). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saitoh Y., Katane M., Miyamoto T., Sekine M., Sakai-Kato K., Homma H., d-Serine and d-alanine regulate adaptive foraging behavior in Caenorhabditis elegans via the NMDA receptor. J. Neurosci. 40, 7531–7544 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang L., Ota N., Romanova E. V., Sweedler J. V., A novel pyridoxal 5′-phosphate-dependent amino acid racemase in the Aplysia californica central nervous system. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 13765–13774 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tanigawa M., Suzuki C., Niwano K., Kanekatsu R., Tanaka H., Horiike K., Hamase K., Nagata Y., Participation of D-serine in the development and reproduction of the silkworm Bombyx mori. J. Insect Physiol. 87, 20–29 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Uo T., Yoshimura T., Shimizu S., Esaki N., Occurrence of pyridoxal 5’-phosphate-dependent serine racemase in silkworm, Bombyx mori. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 246, 31–34 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dai X., Zhou E., Yang W., Zhang X., Zhang W., Rao Y., D-Serine made by serine racemase in Drosophila intestine plays a physiological role in sleep. Nat. Commun. 10, 1986 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Uda K., Abe K., Dehara Y., Mizobata K., Sogawa N., Akagi Y., Saigan M., Radkov A. D., Moe L. A., Distribution and evolution of the serine/aspartate racemase family in invertebrates. Amino Acids 48, 387–402 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ito T., Hamauchi N., Hagi T., Morohashi N., Hemmi H., Sato Y. G., Saito T., Yoshimura T., D-Serine metabolism and its importance in development of Dictyostelium discoideum. Front. Microbiol. 9, 784 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Delsuc F., Brinkmann H., Chourrout D., Philippe H., Tunicates and not cephalochordates are the closest living relatives of vertebrates. Nature 439, 965–968 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cloney R. A., Ascidian larvae and the events of metamorphosis. Am. Zool. 22, 817–826 (1982). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Takamura K., Nervous network in larvae of the ascidian Ciona intestinalis. Dev. Genes Evol. 208, 1–8 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ryan K., Lu Z., Meinertzhagen I. A., The peripheral nervous system of the ascidian tadpole larva: Types of neurons and their synaptic networks. J. Comp. Neurol. 526, 583–608 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Karaiskou A., Swalla B. J., Sasakura Y., Chambon J.-P., Metamorphosis in solitary ascidians. Genesis 53, 34–47 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Matsunobu S., Sasakura Y., Time course for tail regression during metamorphosis of the ascidian Ciona intestinalis. Dev. Biol. 405, 71–81 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chambon J.-P., Soule J., Pomies P., Fort P., Sahuquet A., Alexandre D., Mangeat P.-H., Baghdiguian S., Tail regression in Ciona intestinalis (Prochordate) involves a Caspase-dependent apoptosis event associated with ERK activation. Development 129, 3105–3114 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jeffery W. R., Programmed cell death in the ascidian embryo: Modulation by FoxA5 and Manx and roles in the evolution of larval development. Mech. Dev. 118, 111–124 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Krasovec G., Robine K., Quéinnec E., Karaiskou A., Chambon J. P., Ci-hox12 tail gradient precedes and participates in the control of the apoptotic-dependent tail regression during Ciona larva metamorphosis. Dev. Biol. 448, 237–246 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yamaji S., Hozumi A., Matsunobu S., Sasakura Y., Orchestration of the distinct morphogenetic movements in different tissues drives tail regression during ascidian metamorphosis. Dev. Biol. 465, 66–78 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nakayama-Ishimura A., Chambon J., Horie T., Satoh N., Sasakura Y., Delineating metamorphic pathways in the ascidian Ciona intestinalis. Dev. Biol. 326, 357–367 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sekiguchi T., Kawashima T., Satou Y., Satoh N., Further EST analysis of endocrine genes that are preferentially expressed in the neural complex of Ciona intestinalis: Receptor and enzyme genes associated with endocrine system in the neural complex. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 150, 233–245 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hozumi A., Matsunobu S., Mita K., Treen N., Sugihara T., Horie T., Sakuma T., Yamamoto T., Shiraishi A., Hamada M., Satoh N., Sakurai K., Satake H., Sasakura Y., GABA-induced GnRH release triggers chordate metamorphosis. Curr. Biol. 30, 1555–1561.e4 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Satou Y., Mineta K., Ogasawara M., Sasakura Y., Shoguchi E., Ueno K., Yamada L., Matsumoto J., Wasserscheid J., Dewar K., Wiley G. B., Macmil S. L., Roe B. A., Zeller R. W., Hastings K. E. M., Lemaire P., Lindquist E., Endo T., Hotta K., Inaba K., Improved genome assembly and evidence-based global gene model set for the chordate Ciona intestinalis: New insight into intron and operon populations. Genome Biol. 9, R152 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Altschul S. F., Gish W., Miller W., Myers E. W., Lipman D. J., Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215, 403–410 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hotta K., Mitsuhara K., Takahashi H., Inaba K., Oka K., Gojobori T., Ikeo K., A web-based interactive developmental table for the ascidian Ciona intestinalis, including 3D real-image embryo reconstructions: I. From fertilized egg to hatching larva. Dev. Dyn. 236, 1790–1805 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Syuto M., Kusakabe T., Honda D., Watanabe Y., Takeda K., Tanaka O., Imai H., Determination of D-serine in several model organisms used for metabolic, developmental and/or genetic researches by liquid chromatography/fluorescence detection and tandem mass spectrometry. Mem. Konan Univ. Sci. Eng. Ser. 60, 11–19 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Takahara S., Nakagawa K., Uchiyama T., Yoshida T., Matsumoto K., Kawasumi Y., Mizuguchi M., Obita T., Watanabe Y., Hayakawa D., Gouda H., Mori H., Toyooka N., Design, synthesis, and evaluation of novel inhibitors for wild-type human serine racemase. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 28, 441–445 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gline S., Kaplan N., Bernadskaya Y., Abdu Y., Christiaen L., Surrounding tissues canalize motile cardiopharyngeal progenitors towards collective polarity and directed migration. Development 142, 544–554 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nakańo A., Muramatsu M., A novel GTP-binding protein, Sar1p, is involved in transport from the endoplasmic reticulum to the Golgi apparatus. J. Cell Biol. 109, 2677–2691 (1989). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tikhonova I. G., Baskin I. I., Palyulin V. A., Zefirov N. S., Bachurin S. O., Structural basis for understanding structure−activity relationships for the glutamate binding site of the NMDA receptor. J. Med. Chem. 45, 3836–3843 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Okamura Y., Nishino A., Murata Y., Nakajo K., Iwasaki H., Ohtsuka Y., Tanaka-Kunishima M., Takahashi N., Hara Y., Yoshida T., Nishida M., Okado H., Watari H., Meinertzhagen I. A., Satoh N., Takahashi K., Satou Y., Okada Y., Mori Y., Comprehensive analysis of the ascidian genome reveals novel insights into the molecular evolution of ion channel genes. Physiol. Genomics 22, 269–282 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ogden K. K., Traynelis S. F., New advances in NMDA receptor pharmacology. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 32, 726–733 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Graham D. L., Beio M. L., Nelson D. L., Berkowitz D. B., Human serine racemase: Key residues/active site motifs and their relation to enzyme function. Front. Mol. Biosci. 6, 8 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Denda M., Inoue K., Inomata S., Denda S., γ-Aminobutyric acid (A) receptor agonists accelerate cutaneous barrier recovery and prevent epidermal hyperplasia induced by barrier disruption. J. Invest. Dermatol. 119, 1041–1047 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vyklicky V., Korinek M., Smejkalova T., Balik A., Krausova B., Kaniakova M., Lichnerova K., Cerny J., Krusek J., Dittert I., Horak M., Vyklicky L., Structure, function, and pharmacology of NMDA receptor channels. Physiol. Res. 63 ( Suppl. 1), S191–S203 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Paoletti P., Neyton J., NMDA receptor subunits: Function and pharmacology. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 7, 39–47 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Laube B., Hirai H., Sturgess M., Betz H., Kuhse J., Molecular determinants of agonist discrimination by NMDA receptor subunits: Analysis of the glutamate binding site on the NR2B subunit. Neuron 18, 493–503 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Otsu Y., Darcq E., Pietrajtis K., Mátyás F., Schwartz E., Bessaih T., Abi Gerges S., Rousseau C. V., Grand T., Dieudonné S., Paoletti P., Acsády L., Agulhon C., Kieffer B. L., Diana M. A., Control of aversion by glycine-gated GluN1/GluN3A NMDA receptors in the adult medial habenula. Science 366, 250–254 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Grand T., Abi Gerges S., David M., Diana M. A., Paoletti P., Unmasking GluN1/GluN3A excitatory glycine NMDA receptors. Nat. Commun. 9, 4769 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Menon G. K., Price L. F., Bommannan B., Elias P. M., Feingold K. R., Selective obliteration of the epidermal calcium gradient leads to enhanced lamellar body secretion. J. Invest. Dermatol. 102, 789–795 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mauro T., Bench G., Sidderas-Haddad E., Feingold K., Elias P., Cullander C., Acute barrier perturbation abolishes the Ca2+ and K+ gradients in murine epidermis: Quantitative measurement using PIXE. J. Invest. Dermatol. 111, 1198–1201 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Matthysse A. G., Deschet K., Williams M., Marry M., White A. R., Smith W. C., A functional cellulose synthase from ascidian epidermis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 986–991 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Katoh K., Standley D. M., MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: Improvements in performance and usability. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30, 772–780 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Castresana J., Selection of conserved blocks from multiple alignments for their use in phylogenetic analysis. Mol. Biol. Evol. 17, 540–552 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ronquist F., Huelsenbeck J. P., MrBayes 3: Bayesian phylogenetic inference under mixed models. Bioinformatics 19, 1572–1574 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Stolfi A., Sasakura Y., Chalopin D., Satou Y., Christiaen L., Dantec C., Endo T., Naville M., Nishida H., Swalla B. J., Volff J.-N., Voskoboynik A., Dauga D., Lemaire P., Guidelines for the nomenclature of genetic elements in tunicate genomes. Genesis 53, 1–14 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sasakura Y., Nakashima K., Awazu S., Matsuoka T., Nakayama A., Azuma J., Satoh N., Transposon-mediated insertional mutagenesis revealed the functions of animal cellulose synthase in the ascidian Ciona intestinalis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 15134–15139 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cermak T., Doyle E. L., Christian M., Wang L., Zhang Y., Schmidt C., Baller J. A., Somia N. V., Bogdanove A. J., Voytas D. F., Efficient design and assembly of custom TALEN and other TAL effector-based constructs for DNA targeting. Nucleic Acids Res. 39, e82 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sakuma T., Hosoi S., Woltjen K., Suzuki K.-I., Kashiwagi K., Wada H., Ochiai H., Miyamoto T., Kawai N., Sasakura Y., Matsuura S., Okada Y., Kawahara A., Hayashi S., Yamamoto T., Efficient TALEN construction and evaluation methods for human cell and animal applications. Genes Cells 18, 315–326 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Doyle E. L., Booher N. J., Standage D. S., Voytas D. F., Brendel V. P., Vandyk J. K., Bogdanove A. J., TAL Effector-Nucleotide Targeter (TALE-NT) 2.0: Tools for TAL effector design and target prediction. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, W117–W122 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yoshida K., Hozumi A., Treen N., Sakuma T., Yamamoto T., Shirae-Kurabayashi M., Sasakura Y., Germ cell regeneration-mediated, enhanced mutagenesis in the ascidian Ciona intestinalis reveals flexible germ cell formation from different somatic cells. Dev. Biol. 423, 111–125 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yoshida K., Treen N., TALEN-based knockout system. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1029, 131–139 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Mori H., Wada R., Li J., Ishimoto T., Mizuguchi M., Obita T., Gouda H., Hirono S., Toyooka N., In silico and pharmacological screenings identify novel serine racemase inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 24, 3732–3735 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yasuo H., Satoh N., An ascidian homolog of the mouse brachyury (T) gene is expressed exclusively in notochord cells at the fate restricted stage. (Ascidians/T (Brachyury) gene/sequence conservation/notochord cells/transient expression). Dev. Growth Differ. 36, 9–18 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Corbo J. C., Levine M., Zeller R. W., Characterization of a notochord-specific enhancer from the Brachyury promoter region of the ascidian, Ciona intestinalis. Development 124, 589–602 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kobayashi K., Satou Y., Microinjection of exogenous nucleic acids into eggs: Ciona species. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1029, 5–13 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zeller R. W., Electroporation in Ascidians: History, theory and protocols. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1029, 37–48 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sasakura Y., Suzuki M. M., Hozumi A., Inaba K., Satoh N., Maternal factor-mediated epigenetic gene silencing in the ascidian Ciona intestinalis. Mol. Genet. Genomics 283, 99–110 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bolger A. M., Lohse M., Usadel B., Trimmomatic: A flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30, 2114–2120 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kim D., Pertea G., Trapnell C., Pimentel H., Kelley R., Salzberg S. L., TopHat2: Accurate alignment of transcriptomes in the presence of insertions, deletions and gene fusions. Genome Biol. 14, R36 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Trapnell C., Williams B. A., Pertea G., Mortazavi A., Kwan G., van Baren M. J., Salzberg S. L., Wold B. J., Pachter L., Transcript assembly and quantification by RNA-Seq reveals unannotated transcripts and isoform switching during cell differentiation. Nat. Biotechnol. 28, 511–515 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figs. S1 to S8

Movies S1 and S2