Clinician burnout is an occupational syndrome driven by the work environment [1,2,3]. An organization seeking to reduce burnout and improve well-being among its clinicians can create a better work environment by aligning its commitments, leadership structures, policies, and actions with evidence-based and promising best practices. In this discussion paper, the authors outline organizational approaches that focus on fixing the workplace, rather than “fixing the worker,” and by doing so, advance clinician well-being and the resiliency of the organization [4,5]. A resilient organization, or one that has matched job demands with job resources for its workers and that has created a culture of connection, transparency, and improvement, is better positioned to achieve organizational objectives during ordinary times and also to weather challenges during times of crisis.

Evidence-based and promising practices shown to increase clinician well-being across six domains [6] are presented in this discussion paper: (1) organizational commitment, (2) workforce assessment, (3) leadership (including shared accountability, distributed leadership, and the emerging role of a chief wellness officer [CWO]), (4) policy, (5) efficiency of the work environment, and (6) support. We provide examples (see Table 1) along with principles of organizational action for clinician well-being (see Table 2).

Table 1. Organizational Interventions to Improve Clinician Well-Being.

| Intervention Goal | Strategy | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Reduce job demands | Getting Rid of Stupid Stuff [38,68] | An organization invited clinicians to nominate institutional policies and practices to be deimplemented. Physicians and nurses submitted more than 300 suggestions of wasteful EHR tasks. Ten of the most frequently ignored 12 EHR alerts were removed because they were deemed unnecessary. Upon reevaluation, multiple requirements for documentation and some signatures were also eliminated. |

| Align EHRs to match clinical workflows [69] | An 11-member informatics team conducted on-site EHR and workflow optimizations for individual clinical units, each for two weeks. The intervention included clinician and staff EHR training, building specialty-specific EHR tools, and redesigning teamwork. Clinician perceptions of quality of care, time spent charting, and satisfaction with their EHR and their work all improved [70]. | |

| Reduce inbox volume [71,72,73,74] | Greater inbox message volume is associated with higher rates of burnout [12,13]. Organizations can turn off messages that are automatic, redundant, or low-information (e.g., notifications that tests were ordered without an indication of the results or that the vitals were obtained). One organization also empowered the care team to review, respond to, and route messages as appropriate, substantially reducing the volume of messages that unnecessarily reached the physician or APP [75]. | |

| CMS waiver regarding verbal orders [45] | During the COVID-19 public health emergency, CMS waived certain requirements related to verbal orders to provide clinicians in hospital settings with additional flexibility. This waiver reduced the burden of computerized order entry for APPs and physicians [43] and empowered nurses and other team members to perform team order entry. | |

| Reduce work of prior authorization | Prior authorization is costly to physician practices when hours spent dealing with health plans are converted to dollars [49]. While working collectively with others to reduce this administrative burden [76], organizational leaders can also develop systems where organization-wide support staff, and not individual physicians and APPs, are responsible for completing the prior authorization process. | |

| Eliminate early morning or late afternoon meetings | A health system surveyed its clinical staff and found that work-life conflicts were a major source of stress, particularly for their clinicians who had young children [77]. Eliminating all mandatory early morning and late afternoon meetings can allow clinicians with children to perform drop-offs or pickups from child care. | |

| Improve job resources | Advanced team-based care with in-room support [17,18,78,79] | A department of family medicine adopted a model of two MAs per physician, with the MAs providing real-time documentation and team order entry during the office visits. Quality measures improved, productivity increased, overhead costs per visit were unchanged, patient satisfaction improved, staff satisfaction was high at baseline and remained so, and physician burnout was reduced by half, from 56 percent to 28 percent [80]. |

| Improve clinical workflows | Annual prescription renewal [67] | By routinely renewing all of a patient’s stable, chronic illness medications for 18 months at the time of the annual visit, an organization reduced requests for prescription renewal by roughly half, saving one hour or more per day of physician, APP, or staff time [81]. |

| Virtual visit options at the bookends of the day | Health systems can encourage practices that allow clinicians to flexibly schedule patients during the first and last hours of the day, to maintain their productivity while decreasing perceived work-life conflicts and commuting times [82]. Virtual visits at the beginning or end of the day can improve clinician turnover and burnout scores without negatively impacting patient access, relative value units, or total patient visits. | |

| Provide support | Buddy system | An organization provided a mechanism for peers to sign up as “buddies” to support each other in their work. No formal training was involved. A weekly nudge was sent by email to provide a brief topic of reflection and to encourage check-ins [51]. |

| Collegial dinners | An institution funded meals every few weeks for small groups of colleagues to informally discuss experiences related to their profession. Food, space, and discussion questions were provided. Participants reported increased sense of meaning in work and reduced burnout after the intervention compared to a cohort of physicians who did not receive the intervention [52]. | |

| Peer coaching | An organization provided a four-day intensive training for invited physicians to become peer coaches, trained to be empathetic listeners who help fellow physicians identify and meet their goals [53,54]. | |

| Peer-to-peer support | An organization identified clinicians with strong communication skills to be invited as peer supporters [53]. These clinicians were trained to support colleagues after an adverse event. The training involves empathetic listening and simply being present for a peer’s pain. |

Table 2. Guiding Principles for Implementing Interventions to Improve Clinician Well-Being.

| Do | Don’t | Try |

|---|---|---|

| Focus on assets and bright spots. | Focus solely on what’s not working within the team or in the organization. | Take an assets-based approach by focusing on “what matters” to staff (e.g., Institute for Healthcare Improvement’s “What Matters to You” Conversation Guide for Improving Joy in Work [84]). |

|

Focus on systems interventions. Identify and address systems factors contributing to burnout and the innate human needs to be met in supporting well-being (such as meaning, choice, camaraderie, and equity). |

Blame individuals for burnout. Individual-focused strategies may be beneficial and can be an effective part of a larger organizational effort but are not sufficient on their own. | Remove sources of frustration and inefficiency (e.g., through quality improvement projects that matter to staff). Promote flexibility and work-life integration. Develop and implement targeted work-unit interventions such as work system redesign efforts, reducing inefficiency and workload. |

|

Commit to culture and system transformation. Develop a values-driven culture, and integrate this work into your strategic plan and dashboard at the highest levels of the organization. |

Run a one-off campaign or project on well-being without ties to organizational goals or values. | Create and maintain a leadership role and function at the health executive level responsible for improving and sustaining professional well-being (e.g., chief wellness or well-being officer [29]). Align values and strengthen organizational culture by aligning the design of interventions with desired values such as respect, equity, ethical practice and compassion. Work to discover key staff motivators and factors that diminish or impede joy in work, and help leadership create an environment in which everyone can do their best work. Reduce the stigma and eliminate the barriers to individuals making the choice to maintain or enhance their own mental health and well-being (e.g., consider organizational efforts such as Schwartz Rounds to offer regular opportunities for building camaraderie, communication, and support [85]). |

|

Co-create solutions. Adopt a mindset of implementing “with” staff and not “for” staff with a mutual (versus transactional) approach to improving well-being. |

Plan to “fix” problems that arise. | Engage leadership at all organizational levels to address clinician burnout and improve professional well-being. Commit to behaviors that support high-performing teams [86]. Model behaviors, such as keeping promises to maintain trust, and hold meeting times that are respectful of commitments outside of work for those with other life responsibilities. |

|

Measure what matters and keep it simple. Measure for learning and measure just enough to learn, adapt, and take action. |

Measure for judgment, hide results, fail to act, or communicate what you are learning, where there are areas for improvement. | Evaluate burnout and burnout risk (through validated instruments [59]) and share lessons learned transparently inside and outside of the organization. Codesign your measurement system with your teams. Keep data collection as simple as possible. |

This paper is intended for organizational leaders in health care settings, including governing boards, CWOs, Chief Medical Officers, Chief Nursing Officers, Chief Pharmacy Officers, service line directors, department chairs, and clinical learning environment directors. Drawing on recommendations from the recent National Academy of Medicine consensus study Taking Action Against Clinician Burnout: A Systems Approach to Professional Well-Being [1], this paper also aims to support the frontline clinician workforce, including physicians, dentists, advanced practice clinicians, nurses, pharmacists, occupational and physical therapists, and others, across all career stages and in diverse care settings.

Organizational Evidence-Based and Promising Practices

In this section, the authors describe the six domains of organizational evidence-based and promising practices and how they support organizational resiliency and improve clinician well-being. Specific tools for measurement and types of interventions that can be deployed are discussed in more detail in the following sections.

Domain 1: Organizational Commitment

A cross-cutting commitment to workforce well-being and organizational resilience is essential for preventing burnout within an organization. Just as the landmark report To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System [7] called for a systems approach to patient safety, a systems-based commitment to clinician well-being is needed to create resilient organizations. This commitment can be manifested by adopting the principles of the Charter on Physician Well-Being [8], establishing a well-being program, appointing a CWO [9,10], and/or including measures of workforce well-being within the organization’s strategic plan and data dashboard.

Domain 2: Workforce Assessment

It is not possible to know how an organization—or any part of that organization—is performing without measurement of clinician well-being and burnout. Measurement is essential. Factors known to have an impact on well-being can also be measured, such as electronic health record (EHR)-use metrics of work outside of work and inbox volume [11,12,13], along with the costs of burnout [14,15] (including workforce turnover, early retirement, and reduced clinical effort). Additional leading indicators of clinician well-being, such as characteristic behaviors of leaders, including communicating transparently, nurturing career development, and expressing appreciation for completed work [16]; efficiency of the practice environment, such as team documentation and team order entry [17,18,19,20]; and aspects of organizational culture, such as teamwork and the availability and effectiveness of peer support, can also be measured. The results can be shared with stakeholders, such as unit leaders and the organization’s board, and, subsequently, leaders across the organization can be held mutually responsible for addressing and improving the results [21].

Domain 3: Leadership

Shared Accountability

By establishing shared accountability among an organization’s executive leadership team to achieve Quadruple Aim [22] outcomes (better care, better health, lower cost, and better workforce experience), an organization can structurally support a healthy work environment. For example, instead of a compliance officer and a chief information officer independently making decisions to protect the organization from an audit failure or technology security breach, their decisions could change and be better informed if they shared accountability for all critical aims of the organization, including patient access to care, productivity, workforce recruitment and retention, safe and reasonable clinical workloads, and clinician well-being. In addition, shared accountability means that responsibility for clinician well-being does not solely rest with one leader, but rather is embedded within the organizational structure/operations, and will persist across leadership changes.

Distributed Leadership

A corollary of shared accountability is distribution of a portion of authority and accountability to the professionals closest to the patients. As argued by submarine commander David Marquet, professionals respond better to an approach of “empower and encourage” rather than “command and control” [23]. This approach can be viewed as expressing intent instead of orders, a concept that has also been stated as “wide guardrails, thin rulebook.” In health care, this concept could be translated to “minimizing rules and focusing on only a few high-level outcomes.” Marquet emphasizes the importance of giving control to others, ensuring first that they have the competency and clarity of mission to safely assume that control, which in health care could mean training and empowering nurses to manage information within the EHR, apply independent judgment, and act on verbal orders. Marquet also highlights the need to provide regular feedback and suggests appropriate responses to those who are empowered to act, which in health care could mean encouraging teams to use Plan-Do-Study-Act cycles or lean approaches to design and continually improve their local workflows [24].

Balance of Standardization and Customization

Wise distribution of authority entails balancing the inherent tension between customization and standardization in optimizing clinical workflows [25,26]. The ideal balance varies by situation. Too much customization can be chaotic, time-consuming, and unpredictable in outcomes. Providing enough standardization of common work ensures that it is done reliably and, by default, frees clinicians to spend their cognitive bandwidth on the unique situations that require their expertise and can contribute to professional satisfaction.

On the other hand, too much standardization can be oppressive, disrespectful, and result in the inability of clinicians to adjust to their patients’ and their individual needs [27]. Standard design is built with the mean use case in mind. Yet, patients and clinicians present with wide variation in circumstances, clinical conditions, and preferences. At times, the care provider may be caught as the translator between the standard use case that drove the design and the unique individual who presents for care. The impossibility of serving both imperatives can contribute to moral distress and burnout.

Chief Wellness Officer

Organizations that strategically commit to building capacity and infrastructure to support clinician well-being through formal leadership positions, such as a CWO [28,29] with the expertise, resources, and authority to influence leaders and practices across the organization, will be more impactful than those whose investment is limited to informal champions and stand-alone committees. Without a CWO, ad hoc efforts to support clinician well-being often result in siloed initiatives and frustrated efforts. As the body of knowledge related to risk factors for burnout and interventions to promote well-being evolves and expands, there is a demand for specialization of personnel prepared to carry out transformative change within and across their organization. As such, organizations need centralized roles dedicated to well-being, elevated to the level of the executive leadership team [29,30].

An adaptive leadership approach is critical, given the complex and dynamic nature of ensuring well-being in the workforce. Identifying or developing the right leader with competencies and relational strengths for such an approach is essential. In addition to having the acumen for preserving and bolstering human capital within their organizations, such as emotional intelligence, innovation and strategic vision, executive presence, business skills, and change management expertise, the role requires experience in patient care delivery within the health care system. Adaptive leaders mobilize these strengths to transform processes and culture while embedding change capacity and resilience across the organization.

The transformative change and competency building needed to create a resilient organization requires time, resources, and patience. Organizations committed to addressing burnout and promoting a culture of well-being and resilience in their health care workforce may benefit from identifying and progressing through the following three phases of growth and maturation:

-

1.

Developing (resources and programming dedicated to education and mentoring);

-

2.

Improving (meaningful steps taken at the systems level to advance solutions); and

-

3.

Sustaining (a culture of commitment with adequately resourced infrastructure).

The authors have identified several promising case studies and tools that are available to leaders to apply and adapt to their organizations depending on their growth phase (see Box 1).

Box 1. Resources for Health Care Leaders to Drive Transformative Change.

-

1.

Brigham Health Clinical Care Redesign pilot programs: Brigham and Women’s Hospital is seeking to redesign delivery of care for their patients through efforts that improve innovation in care delivery, technology, physician and patient engagement, and care transitions [31].

-

2.

Stanford Medicine Chief Wellness Officer Course: Stanford Medicine offers a short workshop to train senior health care leaders in the principles of well-being and help them develop a strategic plan for their organization [32].

-

3.

Vanderbilt Center for Professional Health: Vanderbilt University provides courses and tracks research and resources to promote professional health and wellness for physicians and other clinicians [33].

-

4.

American Medical Association STEPS Forward modules: The American Medical Association compiles resources, including toolkits for “Creating the Organizational Foundation for Joy in Medicine” [34], “Establishing a Chief Wellness Officer Position” [10], “Chief Wellness Officer Roadmap” [9], and “Creating a Resilient Organization: Caring for the Healthcare Workforce during Crisis” [4].

-

5.

Action Collaborative on Clinician Well-Being and Resilience case study series: The case study series examines features contributing to success of well-being initiatives at The Ohio State University [35] and Virginia Mason Kirkland Medical Center [36].

Domain 4: Policy

Clinicians may experience moral distress when the policies and practices of their organization conflict with their professional commitment to patient care and ability to do their work. A resilient organization will periodically reassess its policies and practices and eliminate those that are no longer relevant or no longer required [21,37,38]. Such practices and policies are generally well-intended, and may individually seem intuitive or innocuous, yet many are not evidence-based, and when taken in sum, can create an untenable work environment. For example, nurses spend nearly an hour of every four-hour shift charting or reviewing information in the EHR [40]; EHRs add to frustration for nurses [42] as well as physicians [12,13,43]. Much of this administrative work for nurses and physicians is driven by requirements that each add “only a few minutes” to the task, but multiplied over the hundreds of tasks per day, become hours of time away from patients.

Overly conservative interpretation of regulations, standards, and external guidance in the name of safety can paradoxically result in a less safe environment for patient care. When clinician time and cognitive bandwidth are diverted from clinical care to administrative tasks, quality and safety may suffer. Similarly, prioritizing the protection of the organization against an audit failure above other values, often by virtue of leadership structures (e.g., who is at the table, how accountability is distributed, the existence of a chief compliance officer but not a CWO) can leave clinicians adjudicating the tension between the needs of their patients and the policies of the organization.

Much of the burnout and frustration experienced by clinicians may originate in local over-interpretation of external regulations and guidance [44]. For example, some compliance professionals have concluded that the safest path around ambiguous or uncertain regulation is to create a local policy that only the licensed independent practitioner can record the visit note, manually enter orders, or make entries into the problem list within the EHR. Furthermore, some technology professionals have set short time-out intervals for all computer workstations no matter the location, whether a busy public hallway or a private office. In addition, some compliance professionals have adopted a nonbinding and non-evidence-based opinion that nurses and medical assistants (MAs) are required to sign in and out of the medical record when switching between clinical and clerical activities, fragmenting workflow and thought flow and interrupting teamwork. Such compartmentalized decision-making focuses the organization only on a narrow set of values or goals, putting at risk broader objectives, including safe and personalized patient care. This tension at the individual clinician level is also a source of moral distress.

During the COVID-19 public health emergency, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) issued emergency declaration blanket waivers [45], removing many nonessential policy barriers to teamwork and efficiency. For example, this waiver provides clinicians with additional flexibility related to verbal orders [37], reducing one of the major sources of administrative burden and burnout [37,43]. In addition, administrative hurdles for licensing, credentialing, and reappointments have been drastically reduced during the pandemic. Before the health care system and health care practitioners return to “business as usual,” institutions should systematically assess which processes and procedures are necessary for ensuring timely, high-quality patient care and which ones should be permanently retired.

Domain 5: Efficiency of Work Environment

Clinical excellence depends on operational efficiency. When systems are designed to support reliability and efficiency and when the right action happens by default, the humans within the system can use their finite cognitive bandwidth and emotional energy for what Cal Newport calls “deep work” [46]. Deep work is defined as “the ability to focus without distraction on a cognitively demanding task” [46]. When administrative tasks are intentionally minimized, there is more time for the important work of careful listening, nursing assessment, medical decision making, and relationship building with patients and colleagues. Yet, many clinicians believe that administrative and technology-focused tasks dominate their days [47]. This “shallow work” is logistical-style work, often performed while distracted. Arndt and colleagues determined that family physicians spend nearly as much time on security issues (i.e., user names and passwords) as they do reviewing their patients’ problem lists [48]. Furthermore, these physicians spend nearly an hour per day manually entering orders, another hour processing through a series of drop-down boxes for prescription renewal, nearly 90 minutes per day on inbox work, and hours per week on prior authorization requirements [49]. All of this time could be reduced by re-engineering workflows and empowering teamwork, allowing physicians to spend more time with their patients and engaging in “deep work.”

Inbasket messages, i.e., secure messages received from EHR systems, have become a drag on efficiency and a source of burnout. Adler-Milstein and colleagues found that primary care physicians and advanced practice providers (APPs) with more than 300 messages per week have six times the odds of burnout compared with those with less than 150 messages per week [12]. For comparison, the average family physician has approximately 100 inbox messages per day. Likewise, the hours that clinicians spend on computer work after hours is also predictive of burnout. Those with more than three hours per day of work outside of work (a.k.a. “pajama time”) had 13 times the odds of burnout compared with those who had less than 30 minutes per day of work outside of work [12].

EHR log data can be used to characterize the clinical work environment and measure the impact of policy and practice changes [11]. Intermountain Healthcare in Utah piloted an advanced team-based care model, increasing staffing ratios from one MA per physician to two MAs and providing real-time, in-room documentation and order-entry support. EHR log data demonstrated that after six months, physicians spent 20 percent less time documenting and 47 percent less time on order entry, while accommodating 20 percent more patient visits. Burnout in this small sample also decreased [50].

Domain 6: Support

The primary means by which an organization supports its clinicians is by giving them the ability to do their jobs—creating workflows and structures that foster teamwork, efficiency, and quality of care—and then allowing them to return safely home with time and emotional energy to engage in their personal lives with family, friends, and community.

Another important means of support is by creating a culture of connection at work. This culture can be accomplished by structurally facilitating the organic development of friendships at work (i.e., by human-centered team meetings that begin with a few minutes of voluntary sharing or fun), by supporting peer-to-peer discussions (i.e., a buddy system [51] or small group dinners [52]) and by more formal structures, such as peer-to-peer support [53] and peer coaching [54] programs.

Measurement

Shared accountability for clinician well-being is dependent on measurement of burnout, its potential drivers, and its consequences. Organizations should perform periodic assessments of the following:

-

1.

Clinician well-being, using one of several validated instruments (i.e., Maslach Burnout Inventory [55], Mayo Well-Being Index [56], Stanford Professional Fulfillment Index [57], or the Mini-Z burnout assessment [58,59]);

-

2.

Departmental or business unit-level leadership qualities [16] (i.e., a survey of leaders’ direct reports);

-

3.

The efficiency of the practice environment [60] (i.e., by EHR-use metrics [11] and assessing team structure and function [20]);

-

4.

Culture and trust in the organization (i.e., Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Patient Safety Culture Surveys [61]; Mini-Z [62]);

-

5.

Organizational cost of clinician burnout [15]; and

-

6.

Workforce recruitment and retention [63] (i.e., through measures of intention to cut back clinical effort or leave the organization).

Organizations should also be transparent regarding the results of these measurements. Furthermore, it could be considered best practice for leaders to share the results of these annual measures of burnout, its drivers, and consequences with their governing board as well as with their workforce.

Interventions

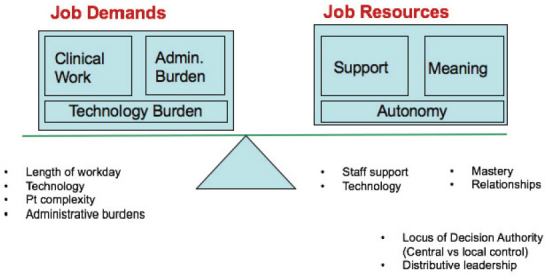

Clinician well-being is enhanced when there is a balance between job demands and job resources (see Figure 1). Job demands include clinical workload (i.e., work hours, patient volume, and patient complexity) along with administrative and technology burdens (i.e., EHR documentation, quality measurement attestation, and forms completion). Job resources include support (i.e., team-based care models, staffing ratios, optimized technology), meaning (i.e., relationships with patients and team, clinical mastery, ability to deliver optimal care) and autonomy (i.e., control over the work environment, schedule, workflows).

Figure 1. Job Demands and Job Resources Conceptual Model of Clinician Well-Being.

SOURCE: Developed by Christine Sinsky and Mark Linzer.

Clinician well-being can be improved by interventions directed toward the individual worker and toward the organization [64]. Two systematic reviews found that both types of interventions were associated with reductions in burnout, but that organization-level interventions were more effective [52,65]. Individual-level interventions include mindfulness training, gratitude practices, stress management training, health coaches, and small group curricula [66]. Organizational interventions included reducing job demands, improving job resources, fostering communication between clinicians, cultivating a sense of teamwork, increasing job control, and improving clinical workflows. As highlighted in Taking Action Against Clinician Burnout: A Systems Approach to Professional Well-Being [1], the overall quality of the existing evidence for effective interventions is relatively low, with few randomized trials, limited measurement of long-term effects, and few multisite studies. To address the overall lack of high-quality evidence, large organizations and professional associations can be involved in the design and funding of implementation research to help build the evidence base.

The set of principles below can help guide organizations in the selection and implementation of interventions to improve clinician well-being. A step-wise approach to selecting and implementing interventions to improve clinician well-being includes:

-

1.

Solicit ideas from all levels of stakeholders, including front-line clinical staff (e.g., via surveys, interviews, focus groups, or existing data sources like employee engagement surveys and exit interviews);

-

2.

Identify interventions that align with other organizational priorities (e.g., advanced team-based care reduces burnout and improves patient access [18]);

-

3.

Look for interventions that simultaneously improve clinician well-being and patient experience (e.g., workflow improvements such as annual prescription renewal can reduce clinician workload and improve patient medication adherence [67];

-

4.

Identify metrics to assess the impact of implementing the intervention;

-

5.

Engage front-line clinicians in the planning, implementation, and assessment of the pilot;

-

6.

Pilot interventions with small groups of clinicians and patients before rolling out more broadly; and

-

7.

Transparently share learnings from the pilot with staff and iterate to improve the effectiveness of the intervention.

In Table 1, the authors provide an overview of selected organizational interventions that are focused on improving clinician well-being. These interventions were drawn from the expertise of individual members of the NAM Action Collaborative on Clinician Well-Being and Resilience, in addition to published reports.

In Table 2, the authors provide guiding principles for implementation of evidence-based and promising practices based on the experiences of the authors and adapting the Institute for Healthcare Improvement’s framework for improving joy in work [83].

Conclusion

Akin to the patient safety and quality movement of the 1990s that transformed care delivery, not by asking individual clinicians to try harder, but by building safer systems, today’s growing clinician well-being movement will be most successful not by admonishing individual clinicians to be more resilient, but by creating more resilient organizations. Now more than ever, health care institutions should become more resilient by committing to workforce well-being as an organizational priority, regularly assessing and reporting burnout and its drivers, sharing accountability for organizational outcomes across leadership roles, periodically evaluating and de-implementing non-evidenced based policies, intentionally measuring and improving the efficiency of the work environment, and creating a culture of connection and support for clinicians.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Barry Marx, MD, FAAP, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services; Bernadette Melnyk, PhD, FAANP, Ohio State University; and Tait Shanafelt, MD, Stanford University, for their valuable contributions to this paper. The authors would also like to thank Charlee Alexander, Senior Program Officer; Candace Webb, Senior Program Officer; Mariana Zindel, Associate Program Officer; T. Anh Tran, Associate Program Officer; and Micheline Toure, Senior Program Assistant at the National Academy of Medicine; and Suzanne Le Menestrel, Senior Program Officer at the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine for the valuable support they provided for this paper.

Funding Statement

The views expressed in this paper are those of the author and not necessarily of the author’s organizations, the National Academy of Medicine (NAM), or the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (the National Academies). The paper is intended to help inform and stimulate discussion. It is not a report of the NAM or the National Academies.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-Interest Disclosures: None to disclose.

Contributor Information

Christine A. Sinsky, American Medical Association.

Lee Daugherty Biddison, Johns Hopkins Medicine.

Aditi Mallick, George Washington University.

Anna Legreid Dopp, American Society of Health-System Pharmacists.

Jessica Perlo, Institute for Healthcare Improvement.

Lorna Lynn, American Board of Internal Medicine.

Cynthia D. Smith, American College of Physicians.

References

- 1.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Taking Action Against Clinician Burnout: A Systems Approach to Professional Well-Being. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dzau VJ, Kirch DG, Nasca TJ. To Care Is Human—Collectively Confronting the Clinician-Burnout Crisis. New England Journal of Medicine. 2018;378(4):312–314. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1715127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dyrbye LN, Shanafelt TD, Sinsky CA, Cipriano PF, Bhatt J, Ommaya A, West CP, Meyers D. NAM Perspectives. Washington, DC: National Academy of Medicine; 2017. Burnout among health care professionals: A call to explore and address this under-recognized threat to safe, high-quality care. Discussion Paper. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shanafelt TD, Ripp J, Brown M, Sinsky CA. Creating a Resilient Organization: Caring for Healthcare Workers during Crisis. American Medical Association; 2020. [September 24, 2020]. https://www.ama-assn.org/system/files/2020-05/caring-for-health-care-workers-covid-19.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 5.West CP, Dyrbye LN, Erwin PJ, Shanafelt TD. Interventions to prevent and reduce physician burnout: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2016;388(10057):2272–2281. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31279-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.American Medical Association. Joy in Medicine: Health System Recognition Program. American Medical Association; Washington, DC: 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Institute of Medicine. To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thomas LR, Ripp JA, West CP. Charter on Physician Well-being. JAMA. 2018;319(15):1541–1542. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shanafelt TD, Sinsky CA. AMA STEPS Forward. 2020. [June 25, 2020]. Chief Wellness Officer Roadmap: Implement a Leadership Strategy for Professional Well-Being. https://edhub.ama-assn.org/steps-forward/module/2767764 . [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shanafelt TD, Sinsky CA. AMA STEPS Forward. 2020. [June 25, 2020]. Establishing a Chief Wellness Officer Position: An Organizational Roadmap: Create the Organizational Groundwork for Professional Well-Being. https://edhub.ama-assn.org/steps-forward/module/2767739 . [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sinsky CA, Rule A, Cohen G, Arndt BG, Shanafelt TD, Sharp CD, Baxter SL, Tai-Seale M, Yan S, Chen Y, Adler-Milstein J, Hribar M. Metrics for assessing physician activity using electronic health record log data. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association. 2020;27(4):639–643. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocz223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adler-Milstein J, Zhao W, Willard-Grace R, Knox M, Grumbach K. Electronic health records and burnout: Time spent on the electronic health record after hours and message volume associated with exhaustion but not with cynicism among primary care clinicians. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association. 2020;27(4):531–538. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocz220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tai-Seale M, Dillon EC, Yang Y, Nordgren R, Steinberg RL, Nauenberg T, Lee TC, Meehan A, Li J, Chan AS, Frosch DL. Physicians’ Well-Being Linked To In-Basket Messages Generated By Algorithms In Electronic Health Records. Health Affairs. 2019;38(7):1073–1078. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Han S, Shanafelt TD, Sinsky CA, Awad KM, Dyrbye LN, Fiscus LC, Trockel M, Goh J. Estimating the Attributable Cost of Physician Burnout in the United States. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2019;171(8):600–601. doi: 10.7326/M18-1422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shanafelt T, Goh J, Sinsky C. The Business Case for Investing in Physician Well-being. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2017;177(12):1826–1832. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.4340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shanafelt TD, Gorringe G, Menaker R, Storz KA, Reeves D, Buskirk SJ, Sloan JA, Swensen SJ. Impact of organizational leadership on physician burnout and satisfaction. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 2015;90(4):432–440. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2015.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smith PC, Lyon C, English AF, Conry C. Practice Transformation Under the University of Colorado’s Primary Care Redesign Model. Annals of Family Medicine. 2019;17(Suppl 1):S24–S32. doi: 10.1370/afm.2424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sinsky CA, Bodenheimer T. Powering-Up Primary Care Teams: Advanced Team Care With In-Room Support. Annals of Family Medicine. 2019;17(4):367–371. doi: 10.1370/afm.2422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Linzer M, Poplau S, Grossman E, Varkey A, Yale S, Williams E, Hicks L, Brown RL, Wallock J, Kohnhorst D, Barbouche M. A Cluster Randomized Trial of Interventions to Improve Work Conditions and Clinician Burnout in Primary Care: Results from the Healthy Work Place (HWP) Study. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2015;30(8):1105–1111. doi: 10.1007/s11606015-3235-4. doi: 10.1007/s11606015-3235-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Willard-Grace R, Hessler D, Rogers E, Dube K, Bodenheimer T, Grumbach K. Team structure and culture are associated with lower burnout in primary care. Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine. 2014;27(2):229–238. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2014.02.130215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sinsky CA, Privitera MR. Creating a “Manageable Cockpit” for Clinicians: A Shared Responsibility. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2018;178(6):741–742. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.0575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bodenheimer T, Sinsky C. From Triple to Quadruple Aim: Care of the Patient Requires Care of the Provider. Annals of Family Medicine. 2014;12(6):573–576. doi: 10.1370/afm.1713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marquet LD. Turn the Ship Around!: A True Story of Turning Followers into Leaders. New York: Penguin Publishing Group; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. 2020. [September 24, 2020]. Ways To Approach the Quality Improvement Process (Page 2 of 2) https://www.ahrq.gov/cahps/quality-improvement/improvement-guide/4-approach-qi-process/sect4part2.html . [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sinsky CA, Roberts R, Beasley J. Annals of Family Medicine. Standardization vs Customization: Time to Rebalance Health Care. In Press. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Linzer M, Levine R, Meltzer D, Poplau S, Warde C, West CP. Bold Steps to Prevent Burnout in General Internal Medicine. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2014;10;29(1):18–20. doi: 10.1007/s11606-013-2597-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Berwick DM, Loehrer S, Gunther-Murphy C. Breaking the Rules for Better Care. JAMA. 2017;317(21):2161–2162. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.4703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ripp J, Shanafelt T. The Health Care Chief Wellness Officer: What the Role Is and Is Not. Academic Medicine. 2020;95(9):1354–1358. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kishore S, Ripp J, Shanafelt T, Melnyk B, Rogers D, Brigham T, Busis N, Charney D, Cipriano P, Minor L, Rothman P, Spisso J, Kirch DG, Nasca T, Dzau V. Health Affairs Blog. 2018. Making The Case For The Chief Wellness Officer In America’s Health Systems: A Call To Action. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shanafelt T, Trockel M, Ripp J, Murphy ML, Sandborg C, Bohman B. Building a Program on Well-Being: Key Design Considerations to Meet the Unique Needs of Each Organization. Academic Medicine. 2019;94(2):156–161. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brigham and Women’s Hospital. Redesigning Care Across the Continuum. [September 24, 2020]. n.d. https://www.brighamandwomens.org/medical-professionals/clinical-care-redesign/redesigning-careacross-the-continuum . [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stanford Medicine WellMD. Chief Wellness Officer Course. [September 24, 2020]. n.d. https://wellmd.stanford.edu/center1/cwocourse.html . [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vanderbilt University Medical Center. Center for Professional Health. [September 24, 2020]. n.d. https://medsites.mc.vanderbilt.edu/cph/home . [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sinsky CA, Shanafelt TD, Murphy MM, de Vries P, Bohman B, Olson K, Vender RJ, Strong-water S, Linzer M. Creating the Organizational Foundation for Joy in Medicine. [September 24, 2020];AMA STEPS Forward. 2019 https://edhub.ama-assn.org/steps-forward/module/2702510 . [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cappelucci K, Zindel M, Knight HC, Busis N, Alexander C. NAM Perspectives. Washington, DC: National Academy of Medicine; 2019. Clinician well-being at the Ohio State University: A case study. Discussion Paper. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zindel M, Cappelucci K, Knight HC, Busis N, Alexander C. NAM Perspectives. Washington, DC: Discussion Paper, National Academy of Medicine; 2019. Clinician well-being at Virginia Mason Kirkland Medical Center: A case study. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sinsky CA, Linzer M. Practice and Policy Reset Post-COVID: Reversion, Transition or Transformation. Health Affairs. 2020;39(8) doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2020.00612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ashton M. Getting Rid of Stupid Stuff. New England Journal of Medicine. 2018;379(19):1789–1791. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1809698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Erickson SM, Rockwern B, Koltov M, McClean RM Medicine Practice and Quality Committee of the American College of Physicians. Putting Patients First by Reducing Administrative Tasks in Health Care: A Position Paper of the American College of Physicians. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2017;166(9):659–661. doi: 10.7326/M16-2697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sinsky C, Colligan L, Li L, Prgomet M, Reynolds S, Goeders L, Westbrook J, Tutty M, Blike G. Allocation of Physician Time in Ambulatory Practice: A Time and Motion Study in 4 Specialties. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2016;165(11):753–760. doi: 10.7326/M16-0961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hendrich A, Chow MP, Skierczynski BA, Lu Z. A 36-hospital time and motion study: how do medical-surgical nurses spend their time. The Permanente Journal. 2008;12(3):25–34. doi: 10.7812/tpp/08-021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Harris DA, Haskell J, Cooper E, Crouse N, Gardner R. Estimating the association between burnout and electronic health record-related stress among advanced practice registered nurses. Applied Nursing Research. 2018;43:36–41. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2018.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shanafelt TD, Dyrbye LN, Sinsky C, Hasan O, Satele D, Sloan J, West CP. Relationship Between Clerical Burden and Characteristics of the Electronic Environment With Physician Burnout and Professional Satisfaction. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 2016;91(7):836–848. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.American Medical Association. American Medical Association. 2020. [April 22, 2020]. Debunking Regulatory Myths. https://www.ama-assn.org/amaone/debunking-regulatory-myths . [Google Scholar]

- 45.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. COVID-19 Emergency Declaration Blanket Waivers for Health Care Providers. US Department of Health and Human Services; Washington, DC: 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Newport C. Deep Work: Rules for Focused Success in a Distracted World. New York: Grand Central Publishing; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sunstein CR. Harvard Public Law Working Paper. 2019. Sludge Audits. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Arndt BG, Beasley JW, Watkinson MD, Temte JL, Tuan W, Sinsky CA, Gilchrist VJ. Tethered to the EHR: Primary Care Physician Workload Assessment Using EHR Event Log Data and Time-Motion Observations. Annals of Family Medicine. 2017;15(5):419–426. doi: 10.1370/afm.2121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Casalino LP, Nicholson S, Gans DN, Hammons T, Morra D, Karrison T, Levinson W. What Does It Cost Physician Practices To Interact With Health Insurance Plans? Health Affairs. 2009;28(Suppl 1):w533–w543. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.4.w533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Faatz J. Personal Communication. 2019. [November 16, 2019]. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Greenawald M. PeerRxMed. 2020. [April 26, 2020]. https://www.peerrxmed.com/ [Google Scholar]

- 52.West CP, Dyrbye LN, Rabatin JT, Call TG, Davidson JH, Multari A, Romanski SA, Henriksen Hellyer JM, Sloan JA, Shanafelt TD. Intervention to promote physician well-being, job satisfaction, and professionalism: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2014;174(4):527–533. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.14387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shapiro J. AMA STEPS Forward. 2020. [June 25, 2020]. Peer Support Programs for Physicians: Mitigate the Effects of Emotional Stressors Through Peer Support. https://edhub.ama-assn.org/steps-forward/module/2767766 . [Google Scholar]

- 54.Berg S. American Medical Association. 2019. [April 26, 2020]. Cleveland Clinic’s doctor peer coaches build physician resiliency. https://www.ama-assn.org/practice-management/physician-health/cleveland-clinic-s-doctor-peer-coaches-build-physician . [Google Scholar]

- 55.Maslach C, Jackson SE, Leiter MP, Schaufeli WB, Schwab RL. Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) 2019. [April 25, 2020]. https://www.mindgarden.com/117-maslach-burnout-inventory . [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mayo Clinic. MedEd Web Solutions. 2020. [April 25, 2020]. Well-Being Index. https://www.mededwebs.com/well-being-index . [Google Scholar]

- 57.Stanford Medicine WellMD Center. Physician Wellness Research/Surveys. 2020. [April 25, 2020]. https://wellmd.stanford.edu/center1/survey.html . [Google Scholar]

- 58.Linzer M, Guzman-Corrales L, Poplau S. AMA STEPS Forward. 2015. [May 27, 2020]. Physician Burnout: Improve Physician Satisfaction and Patient Outcomes. https://edhub.ama-assn.org/steps-forward/module/2702509 . [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dyrbye LN, Meyers D, Ripp J, Dalal N, Bird SB, Sen S. NAM Perspectives. Washington, DC: Discussion Paper, National Academy of Medicine; 2018. Pragmatic approach for organizations to measure health care professional well-being. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.AMA STEPS Forward. Practice assessment: Find modules to optimize your practice. 2018. [April 25, 2020]. https://edhub.ama-assn.org/steps-forward/interactive/16830409 . [Google Scholar]

- 61.Linzer M, Poplau S, Khullar D, Brown R, Varkey A, Yale S, Grossman E, Williams E, Sinsky C. Characteristics of Health Care Organizations Associated With Clinician Trust: Results From the Healthy Work Place Study. JAMA Network Open. 2019;2(6):e196201. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.6201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Medical Office Survey on Patient Safety Culture. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; Rock-ville, MD: 2019. [September 24, 2020]. https://www.ahrq.gov/sops/surveys/medical-office/index.html . [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sinsky CA, Dyrbye LN, West CP, Satele D, Tutty M, Shanafelt TD. Professional Satisfaction and the Career Plans of US Physicians. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 2017;92(11):1625–1635. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2017.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.West CP, Dyrbye LN, Shanafelt TD. Physician burnout: contributors, consequences and solutions. Journal of Internal Medicine. 2018;283(6):516–529. doi: 10.1111/joim.12752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Panagioti M, Panagopoulou E, Bower P, Lewith G, Kontopantelis E, Chew-Graham C, Dawson S, van Marwijk H, Geraghty K, Esmail A. Controlled Interventions to Reduce Burnout in Physicians: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2017;177(2):195–205. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.7674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Melnyk BM, Kelly SA, Stephens J, Dhakal K, McGovern C, Tucker S, Hoying J, McRae K, Ault S, Spurlock E, Bird SB. American Journal of Health Promotion. 2020. Interventions to Improve Mental Health, Well-Being, Physical Health, and Lifestyle Behaviors in Physicians and Nurses: A Systematic Review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sinsky TA, Sinsky CA. A streamlined approach to prescription management. [October 13, 2020];Family Practice Management. 2012 19(6):11–13. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23317126/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ashton M. AMA STEPS Forward. 2019. [May 27, 2020]. Getting Rid of Stupid Stuff: Reduce the Unnecessary Daily Burdens for Clinicians. https://edhub.amaassn.org/steps-forward/module/2757858 . [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sinsky CA, Basch P, Fogg JF. AMA STEPS Forward. 2018. [May 27, 2020]. Electronic Health Record Optimization: Strategies for Thriving; Strategies to help health care organizations maximize the benefits and minimize the burdens of the EHR. https://edhub.ama-assn.org/steps-forward/module/2702761 . [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sieja A, Markley K, Pell J, Gonzalez C, Redig B, Kneeland P, Lin C. Optimization Sprints: Improving Clinician Satisfaction and Teamwork by Rapidly Reducing Electronic Health Record Burden. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 2019;94(5):793–802. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2018.08.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Murphy DR, Satterly T, Giardina TD, Sittig DF, Singh H. Practicing Clinicians’ Recommendations to Reduce Burden from the Electronic Health Record Inbox: a Mixed-Methods Study. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2019;34(9):1825–1832. doi: 10.1007/s11606-019-05112-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Jerzak J, Sinsky C. AMA STEPS Forward. 2017. [May 27, 2020]. EHR In-Basket Restructuring for Improved Efficiency: Efficiently manage your in-basket to provide better, more timely patient care. https://edhub.ama-assn.org/steps-forward/module/2702694 . [Google Scholar]

- 73.Murphy DR, Meyer AND, Russo E, Sittig DF, Wei L, Singh H. The Burden of Inbox Notifications in Commercial Electronic Health Records. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2016;176(4):559–560. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.0209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Murphy DR, Reis B, Sittig DF, Singh H. Notifications received by primary care practitioners in electronic health records: a taxonomy and time analysis. American Journal of Medicine. 2012;125(2):209.e1-7. doi: 10.1016/j.am-jmed.2011.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.AMA STEPS Forward. AMA STEPS Forward. 2017. [April 26, 2020]. Restructuring EHR In-baskets in Minneapolis—St. Paul, MNA Case Study. https://edhub.ama-assn.org/steps-forward/module/2702709 . [Google Scholar]

- 76.Resneck JS. Refocusing Medication Prior Authorization on Its Intended Purpose. JAMA. 2020;323(8):703–704. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.21428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Carr PL, Ash AS, Friedman RH, Scaramucci A, Barnett RC, Szalacha L, Palepu A, Moskowitz MA. Relation of Family Responsibilities and Gender to the Productivity and Career Satisfaction of Medical Faculty. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1998 doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-129-7-199810010-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Funk K, Davis M. Enhancing the Role of the Nurse in Primary Care: The RN “Co-Visit” Model. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2015;30(12):1871–1873. doi: 10.1007/s11606-015-3456-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hopkins K, Sinsky CA. Team-based care: saving time and improving efficiency. [October 13, 2020];Family Practice Management. 2014 21(6):23–29. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25403048/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lyon C, English AF, Chabot Smith P. A Team-Based Care Model That Improves Job Satisfaction. [October 13, 2020];Family Practice Management. 2018 25(2):6–11. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29537246/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.AMA STEPS Forward. Four Interventions Stemmed the Tide of Refill Requests. 2019. [May 27, 2020]. https://edhub.ama-assn.org/steps-forward/module/2757862 . [Google Scholar]

- 82.Shanafelt TD, Noseworthy JH. Executive Leadership and Physician Well-being: Nine Organizational Strategies to Promote Engagement and Reduce Burnout. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 2020;92(1):129–146. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Perlo J, Balik B, Swensen S, Kabcenell A, Landsman J, Feeley D. IHI White Paper. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Institute for Healthcare Improvement; 2017. [September 24, 2020]. IHI Framework for Improving Joy in Work. http://www.ihi.org/resources/Pages/IHIWhitePapers/Framework-Improving-Joy-in-Work.aspx . [Google Scholar]

- 84.Perlo J, Balik B. “What Matters to You?” Conversation Guide for Improving Joy in Work. Institute for Healthcare Improvement; Boston, MA: 2017. [September 24, 2020]. http://www.ihi.org/resources/Pages/Tools/Joy-in-Work-What-Matters-to-You-Conversation-Guide.aspx . [Google Scholar]

- 85.Pepper JR, Jaggar S, Mason MJ, Finney SJ, Dusmet M. Schwartz Rounds: reviving compassion in modern healthcare. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 2012;105(3):94–95. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.2011.110231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Smith CD, Balatbat C, Corbridge S, Legreid Dopp A, Fried J, Harter R, Landefeld S, Martin CY, Opelka F, Sandy L, Sato L, Sinsky C. NAM Perspectives. Washington, DC: National Academy of Medicine; 2018. Implementing optimal team-based care to reduce clinician burnout. Discussion Paper. [DOI] [Google Scholar]