Abstract

Background

Buprenorphine-naloxone (BUP-NX) is a first-line treatment for opioid use disorder and has a superior safety profile compared to other forms of opioid agonist therapy. In Canada, restrictions on BUP-NX prescribing were relaxed in 2016, which may have had an effect on rates of diversion and non-prescribed use. We sought to longitudinally examine the reported availability and use of non-prescribed BUP-NX among people who use drugs (PWUD) in an urban Canadian setting.

Methods

We collected data from two linked prospective cohorts of PWUD in Vancouver, Canada, and examined self-reported availability and use of non-prescribed BUP-NX over time. We used a multivariable generalized estimating equations model to identify trends and factors associated with the immediate availability (i.e., within 10 min) of non-prescribed BUP-NX.

Results

Among 1617 participants between 2014 and 2020, the immediate availability of non-prescribed BUP-NX increased from 16% to 63% (p<0.001). In the multivariable analysis, factors independently associated with immediate BUP-NX availability included calendar year (adjusted odds ratio = 1.19, 95% confidence interval: 1.15–1.23), along with a number of other variables suggestive of more severe substance use disorders. Only 17 participants ever reported use of non-prescribed BUP-NX.

Conclusions

We observed that BUP-NX has become increasingly available in the unregulated drug supply in recent years but its use has remained infrequent in this setting. These results suggest that relaxed restrictions on BUP-NX prescribing have not been a major driver of increased non-prescribed use in this population.

Keywords: Buprenorphine, Opioid-related disorders, Opioid agonist therapy, Prescription drug diversion

INTRODUCTION

Buprenorphine is one of a number of evidence-based medications for the treatment of opioid use disorder (OUD), and is supported by a wealth of evidence demonstrating its ability to improve treatment retention, reduce unregulated opioid use, and prevent negative health consequences such as HIV/hepatitis C virus acquisition and disease progression as well as overdose death for treatment-seeking people who use drugs (PWUD) (Gowing, Farrell, Bornemann, Sullivan, & Ali, 2011; Mattick, Breen, Kimber, & Davoli, 2014; Platt et al., 2017). Due to its mechanism of action as a partial mu-opioid receptor agonist, it is also less likely to cause sedation and respiratory depression compared to other forms of opioid agonist therapy (OAT), and for the treatment of OUD it is frequently co-formulated with naloxone (BUP-NX) in order to further reduce rates of non-prescribed use (Walsh, Preston, Stitzer, Cone, & Bigelow, 1994). Despite its effectiveness and a generally good safety profile, prescribing of BUP-NX remains strictly controlled by regulators across much of North America and Europe out of a perceived fear of drug diversion and risks of non-prescribed use, as well as a significant legacy of public stigma that continues to contribute to structural barriers limiting access (Allen, Nolan, & Paone, 2019; Vranken et al., 2017).

The use of non-prescribed BUP-NX is well described in the literature, but in the United States and Canada it is largely limited to settings where other opioids are not available (for example correctional facilities) (Bi-Mohammed, Wright, Hearty, King, & Gavin, 2017). Non-prescribed use outside of these settings is much less prevalent, with the most common reported reasons for use being the treatment of opioid withdrawal symptoms, and/or the management of OUD itself (Lofwall & Walsh, 2014). Indeed, in some settings non-prescribed use has even been associated with a decreased risk of opioid overdose, potentially representing a safer alternative to the toxic drug supply (Carlson, Daniulaityte, Silverstein, Nahhas, & Martins, 2020). In spite of this, significant restrictions around BUP-NX prescribing persist in many places, ranging from requirements for specific training and waivers or exemptions in order to prescribe, to limiting the total number of patients that can be treated per licensed provider. These regulations can present considerable barriers to those seeking prescriptions for BUP-NX, and may be contributors to the overall poor access to BUP-NX reported in many settings (Wu, Zhu, & Swartz, 2016). Some have also argued that these regulations may unintentionally contribute to diversion and non-prescribed use of BUP-NX due to the number of patients unable to access this medication through a prescribed pathway (Doernberg, Krawczyk, Agus, & Fingerhood, 2019). Whether these restrictions are effective in reducing diversion, whether they are significant contributors to the overall low rates of non-prescribed BUP-NX use, and whether they actually limit the net harms caused by opioid use remain areas of contention.

In British Columbia, Canada, the requirement for an exemption to prescribe BUP-NX was removed in 2016, and it was officially endorsed as the first-line treatment for OUD in 2017. At the same time, prescribing recommendations for this medication were also relaxed, moving away from the previous model that recommended daily witnessed administration of doses in most new patients in order to limit diversion (BC Centre on Substance Use, 2017). Theoretically, these changes may have increased the availability and/or the non-prescribed use of diverted BUP-NX, however these trends have never been measured. An exploration of any such changes could have important implications on the regulation of BUP-NX elsewhere, and further characterization of factors associated with the use of non-prescribed BUP-NX (including any potential relationship with overdose risk) would be useful information for clinicians and public health professionals alike. We thus sought to longitudinally examine the availability and non-prescribed use of BUP-NX in a prospective cohort of PWUD over time in Vancouver, Canada.

METHODS

Study setting and participants

Data were collected from two ongoing open prospective cohorts of PWUD in Vancouver between December 1, 2014 and March 30, 2020, which have been described in detail previously: the Vancouver Injection Drug Users Study (VIDUS), and the AIDS Care Cohort to evaluate Exposure to Survival Services (ACCESS) (Strathdee et al., 1997). Briefly, these are community-recruited cohorts that have been running since 1996 and are composed of HIV-negative participants who have used injection drugs within the month prior to enrollment (VIDUS) and HIV-positive participants who have used any unregulated substance (other than cannabis) in the month prior to enrollment (ACCESS). At the time of cohort entry and semi-annually thereafter participants complete an intervieweradministered questionnaire to elicit information on demographics, drug use patterns and behaviours, and interactions with the healthcare and criminal justice systems. The cohorts receive annual ethics approval from the University of British Columbia / Providence Health Care research ethics board.

For the present study, the sample was restricted to VIDUS/ACCESS participants who reported a history of injection drug use and completed at least one study visit between December 2014 and March 2020, as the survey question about availability of non-prescribed BUP-NX was added to the questionnaire in December 2014.

Measures

The two primary outcome variables were time-varying and included the reported availability of non-prescribed BUP-NX at the time of interview (“How difficult would it be for you to get the following drugs right now in the area where you typically obtain your drugs?”; immediate availability [i.e., the ability to acquire it within <10 min], delayed availability [i.e., the ability to acquire it but taking longer than 10 min], and no availability [i.e. “could not score”]), and the reported use of non-prescribed BUP-NX in the past six months (“In the last 6 months, which of the following prescription opioids did you use when they were not prescribed for you or that you took only for the experience or feeling they caused?”; yes vs. no). As in previous studies participants were asked to report the availability of non-prescribed BUP-NX whether or not it was a substance they reported using (Ho et al., 2018; Reddon et al., 2018). The primary explanatory variable of interest was calendar year of interview (continuous). A range of other explanatory variables were also included based on a hypothesized association with the availability and use of non-prescribed BUP-NX. Socio-demographic characteristics included age (per 10 years), gender (male vs. female, transgender, or non-binary gender), self-identified race/ethnicity (white vs. Black, Indigenous, or other persons of colour), homelessness, and residing in the Downtown Eastside (an urban Vancouver neighbourhood with a high concentration of substance use). Drug use patterns included ≥daily non-prescribed opioid use (including heroin, fentanyl, and/or other prescription opioids), ≥daily injection cocaine use, ≥daily non-injection crack use, ≥daily methamphetamine use, currently enrolled in OAT (a threelevel variable consisting of BUP-NX vs. any other form of OAT aside from BUP-NX vs. none [reference category]), and recent non-fatal overdose. Other indicators of socio-structural exposures included the reported inability to access addiction care (defined as at least one unsuccessful attempt within the past six months), current possession of a naloxone kit, recent incarceration, and involvement in drug dealing. All behavioural variables referred to activities within the previous six months, and all variables were dichotomized as yes vs. no unless otherwise noted.

Statistical analyses

First, we examined the baseline sample characteristics stratified by immediate vs. no immediate availability of non-prescribed BUP-NX, using Pearson’s chi-squared test for categorical variables, and Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables (Altman, 1991). Since the use of non-prescribed BUP-NX was very rare in our sample, all subsequent analyses were conducted for availability of non-prescribed BUP-NX only.

Next, we analyzed the trends in availability of non-prescribed BUP-NX over time using the Cochrane-Armitage test for trend (Armitage, 1955).

Finally, we employed two sets of bivariable and multivariable generalized estimating equation (GEE) logistic regression models to identify factors associated with the immediate and delayed availability (vs. no availability) of non-prescribed BUP-NX, respectively (Zeger & Liang, 1986). All explanatory variables that were associated with the immediate and delayed availability at p < 0.10 level in bivariable analyses were included in the multivariable models. All p-values were two-sided, and all statistical analyses were conducted in SAS software version 9.4 (SAS, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

A total of 1617 participants were included in the study, including 966 (60%) male and 914 (58%) of white ethnicity. The study population also included 579 (36%) female, 15 (1%) transgender male-to-female, and 6 (<1%) participants who identified as twospirited or other. The other self-reported race/ethnicities included 599 (37%) Indigenous, 30 (2%) African American, 26 (2%) Asian, 23 (1%) Hispanic/Latino, and 53 (3%) Other/Mixed. At baseline the median age of participants was 47 years (interquartile rage [IQR] 37–54), 364 (23%) were homeless, and 970 (60%) resided within the Downtown Eastside. At least daily opioid use was reported by 455 (28%), 190 (12%) had experienced a non-fatal overdose within the past six months, and only 80 (5%) reported an inability to access addiction treatment. The median number of follow-ups per participant was 7 (IQR = 4 – 10). Detailed sample characteristics stratified by reported immediate availability of non-prescribed BUP-NX are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of participants, stratified by reported immediate (<10 min) vs. no immediate availability (>10 min or not available) of non-prescribed BUP-NX

| Characteristic | Total n = 1617 (100%) | Immediate availability n = 351 (21.7%) | No immediate availability n = 848 (52.4%) | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 47 (37 – 54) | 46 (35 – 53) | 48 (40 – 54) | 0.79 (0.70 – 0.89) | <0.001 |

| Male gender | |||||

| yes | 966 (59.7) | 226 (64.4) | 497 (58.6) | 1.34 (1.02 – 1.74) | 0.033 |

| no | 594 (36.7) | 112 (31.9) | 329 (38.8) | ||

| White ethnicity | |||||

| yes | 914 (56.5) | 193 (55.0) | 482 (56.8) | 0.92 (0.71 – 1.18) | 0.501 |

| no | 668 (41.3) | 152 (43.3) | 348 (41.0) | ||

| Homelessness† | |||||

| yes | 364 (22.5) | 109 (31.1) | 139 (16.4) | 2.30 (1.72 – 3.08) | <0.001 |

| no | 1248 (77.2) | 241 (68.7) | 708 (83.5) | ||

| Reside in Downtown Eastside† | |||||

| yes | 970 (60.0) | 254 (72.4) | 475 (56.0) | 2.06 (1.57 – 2.69) | <0.001 |

| no | 647 (40.0) | 97 (27.6) | 373 (44.0) | ||

| Daily non-prescribed opioid use† | |||||

| Yes | 455 (28.1) | 129 (36.8) | 186 (21.9) | 2.07 (1.58 – 2.71) | <0.001 |

| no | 1162 (71.9) | 222 (63.2) | 662 (78.1) | ||

| Daily injection cocaine use† | |||||

| yes | 66 (4.1) | 20 (5.7) | 37 (4.4) | 1.32 (0.76 – 2.32) | 0.323 |

| no | 1551 (95.9) | 331 (94.3) | 811 (95.6) | ||

| Daily non-injection crack use† | |||||

| yes | 167 (10.3) | 33 (9.4) | 91 (10.7) | 0.87 (0.57 – 1.32) | 0.501 |

| no | 1449 (89.6) | 317 (90.3) | 757 (89.3) | ||

| Daily methamphetamine use† | |||||

| yes | 247 (15.3) | 77 (21.9) | 102 (12.0) | 2.06 (1.49 – 2.86) | <0.001 |

| no | 1368 (84.6) | 273 (77.8) | 746 (88.0) | ||

| Opioid agonist therapy† | |||||

| BUP-NX | 54 (3.4) | 24 (6.8) | 14 (1.7) | 4.40 (2.22 – 8.72) | <0.001 |

| Any other OAT | 798 (49.4) | 162 (46.2) | 416 (49.1) | 1.02 (0.79 – 1.32) | 0.888 |

| None | 762 (47.2) | 165 (47.0) | 416 (49.1) | Ref. | |

| Recent overdose† | |||||

| yes | 190 (11.8) | 63 (17.9) | 76 (9.0) | 2.23 (1.55 – 3.19) | <0.001 |

| no | 1425 (88.1) | 287 (81.8) | 771 (90.9) | ||

| Unable to access treatment† | |||||

| yes | 80 (4.9) | 20 (5.7) | 31 (3.7) | 1.59 (0.89 – 2.83) | 0.113 |

| no | 1533 (94.8) | 331 (94.3) | 815 (96.1) | ||

| Possesses naloxone kit | |||||

| Yes | 369 (22.8) | 116 (33.0) | 143 (16.9) | 2.42 (1.82 – 3.23) | <0.001 |

| No | 1243 (76.9) | 235 (67.0) | 702 (82.8) | ||

| Recent incarceration† | |||||

| yes | 107 (6.6) | 43 (12.3) | 27 (3.2) | 4.24 (2.58 – 6.99) | <0.001 |

| no | 1504 (93.0) | 307 (87.5) | 818 (96.5) | ||

| Involved in drug dealing† | |||||

| yes | 327 (20.2) | 109 (31.1) | 121 (14.3) | 2.70 (2.01 – 3.64) | <0.001 |

| No | 1289 (79.7) | 242 (68.9) | 726 (85.6) |

Denotes activities or situations referring to the past 6 months.

Numbers may not add to 100% due to missing responses.

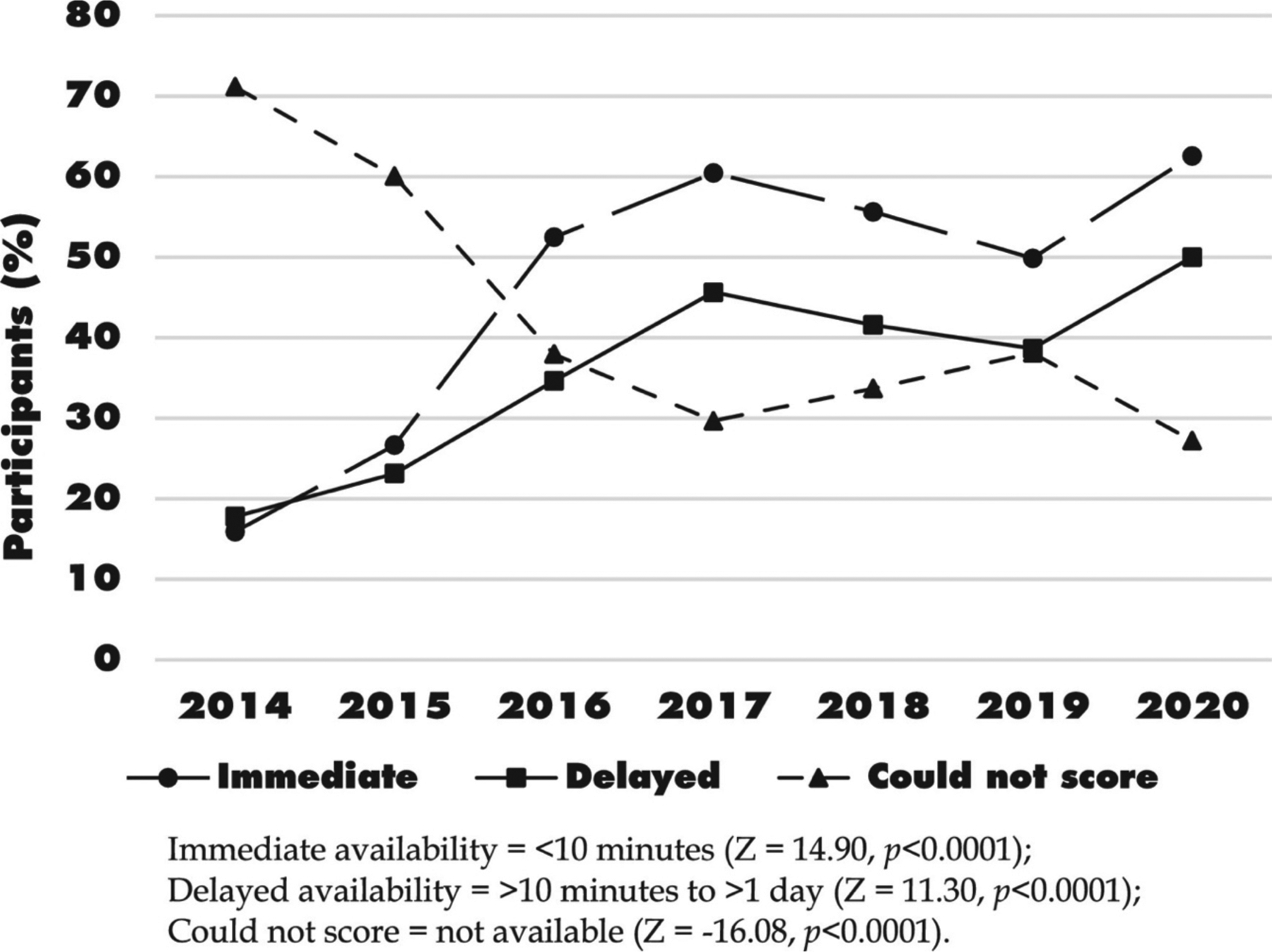

Over the duration of the study, the reported immediate availability of non-prescribed BUP-NX increased from 16% in 2014 to 63% in 2020 (Fig. 1; p < 0.001), and the reported delayed availability increased from 18% to 50% (p < 0.001). The reported inability to obtain non-prescribed BUP-NX decreased from 71% to 27% (p < 0.001). Reported non-prescribed BUP-NX use within the past six months was infrequent, with only 17 participants providing a total of 17 reports of use throughout the entire study period. When broken down by the calendar year of interviews, the frequencies ranged from 0 reports of use in 2014 to a maximum of 6 reports in 2016. Due to low counts no further analyses could be performed on non-prescribed BUP-NX use.

Figure 1.

Percentage of participants reporting non-prescribed BUP-NX availability (n = 1617).

In a bivariate analysis the reported immediate availability of BUP-NX was positively associated with calendar year (odds ratio [OR] = 1.23, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.20–1.27). A detailed summary of other relationships identified in the bivariate analysis can be seen in Table 2.

Table 2.

Bivariable and multivariable GEE analysis of factors associated with immediate (<10 min) BUP-NX availability (n = 1617)

| Characteristic | Unadjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI) | Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Year (by calendar year) | 1.23 (1.20 – 1.27)* | 1.19 (1.15 – 1.23)** |

| Median age (per 10 years older) | 0.88 (0.82 – 0.94)* | 1.04 (0.97 – 1.11) |

| Male gender | 1.09 (0.94 – 1.25) | – |

| White ethnicity | 1.10 (0.96 – 1.26) | – |

| Homelessness† | 1.24 (1.08 – 1.41)* | 1.08 (0.93 – 1.25) |

| Reside in Downtown Eastside† | 1.64 (1.46 – 1.83)* | 1.46 (1.30 – 1.64)** |

| Daily non-prescribed opioid use† | 1.40 (1.24 – 1.58)* | 1.29 (1.14 – 1.46)** |

| Daily injection cocaine use† | 1.29 (0.99 – 1.69)* | 1.23 (0.94 – 1.62) |

| Daily non-injection crack use† | 0.95 (0.80 – 1.12) | – |

| Daily methamphetamine use† | 1.37 (1.19 – 1.59)* | 1.09 (0.93 – 1.28) |

| Opioid agonist therapy† | ||

| BUP-NX | 2.00 (1.53 – 2.63)* | 1.78 (1.35 – 2.35)** |

| Any other OAT | 1.07 (0.95 – 1.20) | 1.12 (0.99 – 1.26) |

| None | Ref. | Ref. |

| Recent overdose | 1.45 (1.26 – 1.67)* | 1.20 (1.03 – 1.39)** |

| Unable to access treatment† | 0.91 (0.71 – 1.16) | – |

| Possesses naloxone kit | 1.87 (1.70 – 2.05)* | 1.39 (1.24 – 1.55)** |

| Recent incarceration† | 1.58 (1.26 – 1.99)* | 1.43 (1.11 – 1.84)** |

| Involved in drug dealing | 1.53 (1.33 – 1.75)* | 1.37 (1.18 – 1.58)** |

Denotes activities or situations referring to the past 6 months.

p < 0.10,

p < 0.05.

Multivariable analysis showed that immediate BUP-NX availability (vs. no availability) was independently associated with calendar year (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] = 1.19, 95% CI: 1.15–1.23) as well as living in the Downtown Eastside (aOR = 1.46, 95% CI: 1.30–1.64), daily non-prescribed opioid use (aOR = 1.29, 95% CI: 1.14–1.46), being on prescribed BUP-NX (aOR = 1.78, 95% CI: 1.35–2.35), recent overdose (aOR = 1.20, 95% CI: 1.03–1.39), possessing a naloxone kit (aOR = 1.39, 95% CI: 1.24–1.55), recent incarceration (OR = 1.43, 95% CI: 1.11–1.84), and involvement in drug dealing (aOR = 1.37, 95% CI: 1.18–1.58). Delayed availability of BUP-NX also had similar relationships in both bivariate and multivariable analysis (Appendix 1).

DISCUSSION

In this longitudinal study of PWUD in two community-recruited prospective cohorts, the reported availability of non-prescribed BUP-NX increased significantly between 2014 and 2020. Meanwhile, reports of non-prescribed use were extremely low throughout our study period.

The rising availability of non-prescribed BUP-NX observed in this study corresponds with a number of changes in the regulation and education around its prescribing in British Columbia over a similar time frame, including an increased effort to educate and enlist prescribers, the removal of a need for an exemption in order to prescribe BUP-NX in 2016, and the official recommendation of BUP-NX as first line therapy for OUD in the provincial guidelines in 2017 (BC Centre on Substance Use, 2017). As a result of these efforts the total number of BUP-NX prescribers in the province has risen dramatically, with the number of patients in the province filling a prescription for BUP-NX increasing from 2002 in 2014 to 6187 by the end of 2020 (BC Opioid Substitution Treatment System, 2017; BC Centre for Disease Control, 2021). In addition, the recent guideline changes also recommended less restrictive prescribing practices and much faster progression to unwitnessed take-home doses. Examining the trend seen in Fig. 1, it does suggest that access to non-prescribed BUP-NX may have been rising even prior to the significant regulatory changes made in 2016, which is corroborated by a steady rise in both rates of prescription and approved providers even prior to that time, though the significant jump noted after 2016 is likely due at least in part to these policy adjustments (BC Opioid Substitution Treatment System, 2017). The lack of any substantial uptake of non-prescribed use is consistent with prior documentation of few measurable consequences to an overall increased availability of this medication. A further example can be seen in British Columbia Coroner’s report, where between the years of 2015 and 2017 < 5 out of 1789 overdose deaths with available toxicology results in the province had any significant level of buprenorphine in their systems, all of which were linked to prescriptions within the past 60 days (Crabtree, Lostchuck, Chong, Shapiro, & Slaunwhite, 2020). In other settings, the use of non-prescribed buprenorphine has even been linked with a lower overall risk of drug overdose, highlighting the potential harm reduction consequences of diversion, though this observation was not noted here (Carlson et al., 2020). Our study adds additional evidence to suggest that, at least in this context, non-prescribed BUP-NX is not a significant driver of ongoing overdoses or other drug-related harms.

The increasing availability of non-prescribed BUP-NX seen in this work also aligns with similar observations detailing the increasing prevalence of other non-prescribed opioids, as the availability of both diverted methadone as well as other prescription opioids have been reported to be on the rise in this same population (Ho et al., 2018; Reddon et al., 2018). Not surprisingly, in our study immediate access to BUP-NX was associated with factors indicating closer contact with the unregulated drug supply such as living in the Downtown Eastside and involvement in drug dealing, as well as a number of factors predictive of more severe substance use disorders including at least daily non-prescribed opioid use, OAT involvement, and recent non-fatal overdose. The low prevalence of non-prescribed BUP-NX use is also not surprising, considering that other evidence from these cohorts has indicated an overall low interest (18%) in accessing prescriptions for BUP-NX (Weicker et al., 2019). The major reasons provided in this work for not being interested in BUP-NX included satisfaction with current agonist therapy (including other locally available evidence-based approaches such as methadone, slow-release oral morphine, or injectable opioid agonist therapy), or an overall lack of awareness/information on this specific medication (Weicker et al., 2019). The generalizability of our results to populations with higher levels of interest in BUP-NX thus remains unknown.

The results of this study must also be interpreted in the context of widespread availability of prescribed BUP-NX, with only 5% of participants reporting an inability to access addiction care at baseline. A majority of these participants did live in the Downtown Eastside of Vancouver, an urban area with both a high concentration of substance use as well as a high density of low-barrier OAT clinics (Amram et al., 2019). Easy access to prescribed BUP-NX (in addition to the aforementioned low reported interest) may explain in part why our rates of non-prescribed use were so low, especially compared to other North American studies where described use of non-prescribed BUP-NX has been as high as 76% (Bazazi, Yokell, Fu, Rich, & Zaller, 2011). Whether these findings would be similar in a study setting with less widespread BUP-NX availability through prescribed channels is also uncertain.

These results fill a gap in the literature specifically linking the availability of non-prescribed BUP-NX to the prevalence of its use. They suggest strongly that, at least in this context, a rise in the availability of this medication has not resulted in vastly increased uptake in use. This observation supports the idea that the hypothesized harms associated with loosening restrictions on BUP-NX prescribing in other settings may be overstated. The implications of this work are important, especially considering the ongoing overdose crisis and the evolving debate occurring in the United States around regulations limiting the widespread prescribing of BUP-NX. Our results suggest that reducing these restrictions does not necessarily cause a commensurate increase in non-prescribed use, and could in fact have the opposite effect by making it easier to access evidence-based therapy for a treatable medical condition.

This study has a number of important limitations. First, it is observational in nature, so causality in our reported associations cannot be implied. Second, it requires selfreporting of sensitive information, thus we cannot rule out a response bias. Previous work in similar populations has, however, suggested this is a valid approach (Darke, 1998) Third, the generalizability of this sample to all PWUD in our setting or other Canadian or American jurisdictions is unknown, especially given the rapid rise of fentanyl and other opioid analogues in the drug supply, which have become the predominant forms of unregulated opioid available in our setting over the duration of this study. Widespread access to other forms of opioid agonist therapy including methadone, slow-release oral morphine, and injectable opioid agonist therapy, which are preferable options for some, may also have an impact on the generalizability of the present study findings. Finally, a deeper understanding of the drivers of these trends cannot be concluded based on these data alone, and follow up qualitative research might help us better understand the many influences that likely contribute to these observations.

CONCLUSIONS

In our community-recruited cohorts of PWUD the reported availability of non-prescribed BUP-NX increased dramatically between 2014 and 2020, but these changes were not accompanied by increased reports of non-prescribed use. These results suggest that the potential concerns related to the relaxing of prescribing regulations for BUP-NX may be overstated, and that these restrictions may represent an unnecessary barrier in ensuring access to a critical medication in our fight against the ongoing overdose crisis in the United States and Canada.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the study participants for their contribution to the research, as well as current and past researchers and staff. This study was performed on the unceded traditional territory of the Coast Salish Peoples, including the Musqueam, Squamish, and Tsleil-Waututh Nations. The study was supported by the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) (U01-DA038886, U01-DA0251525) and in part by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) Canadian Research Initiative on Substance Misuse (SMN-139148). Dr. Paxton Bach is supported by the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research. Dr. M-J Milloy, the Canopy Growth professor of cannabis science, is supported in part by the NIH (U01-DA0251525), a New Investigator Award from CIHR and a Scholar Award from the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research (MSFHR). His institution has received an unstructured gift to support him from NG Biomed, Ltd., a private firm applying for a government license to produce cannabis. The Canopy Growth professorship in cannabis science was established through unstructured gifts to the University of British Columbia from Canopy Growth, a licensed producer of cannabis, and the Ministry of Mental Health and Addictions of the Government of British Columbia. Dr. Kanna Hayashi holds the St. Paul’s Hospital Chair in Substance Use Research and is supported in part by the NIH grant (U01DA038886), a MSFHR Scholar Award, and the St. Paul’s Foundation.

Abbreviations

- ACCESS

AIDS care cohort to evaluate exposure to survival services

- BUP-NX

buprenorphine-naloxone

- GEE

generalized estimating equations

- OAT

opioid agonist therapy

- OUD

opioid use disorder

- PWUD

people who use drugs

- VIDUS

Vancouver Injection Drug Users Study

Appendix 1.

Bivariable and multivariable GEE analysis of factors associated with delayed BUP-NX availability (n = 1617)

| Characteristic | Unadjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI) | Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Year (by calendar year) | 1.20 (1.16 – 1.24)* | 1.17 (1.13 – 1.22)** |

| Median age (per 10 years older) | 0.77 (0.72 – 0.82)* | 0.85 (0.79 – 0.91)** |

| Male gender | 1.02 (0.88 – 1.19) | – |

| White ethnicity | 1.44 (1.25 – 1.66)* | 1.58 (1.37 – 1.82)** |

| Homelessness† | 1.37 (1.17 – 1.60)* | 1.13 (0.95 – 1.35) |

| Reside in Downtown Eastside† | 1.31 (1.16 – 1.47)* | 1.17 (1.04 – 1.33)** |

| Daily non-prescribed opioid use† | 1.46 (1.27 – 1.68)* | 1.30 (1.11 – 1.51)** |

| Daily injection cocaine use† | 0.93 (0.69 – 1.25) | – |

| Daily non-injection crack use† | 1.09 (0.90 – 1.30) | – |

| Daily methamphetamine use† | 1.32 (1.12 – 1.56)* | 0.99 (0.83 – 1.19) |

| Opioid agonist therapy† | ||

| BUP-NX | 1.83 (1.34 – 2.50)* | 1.64 (1.18 – 2.29)** |

| Any other OAT | 1.30 (1.14 – 1.47)* | 1.30 (1.14 – 1.48)** |

| None | Ref. | Ref. |

| Recent overdose | 1.43 (1.22 – 1.68)* | 1.13 (0.95 – 1.35) |

| Unable to access treatment† | 1.21 (0.92 – 1.60) | – |

| Possesses naloxone kit | 1.79 (1.60 – 2.01)* | 1.31 (1.15 – 1.49)** |

| Recent incarceration† | 1.73 (1.31 – 2.27)* | 1.36 (1.01 – 1.83)** |

| Involved in drug dealing | 1.65 (1.41 – 1.93)* | 1.38 (1.17 – 1.64)** |

Denotes activities or situations referring to the past 6 months.

p < 0.10,

p < 0.05.

Footnotes

Ethics approval

The authors declare that they have obtained ethics approval from an appropriately constituted ethics committee/institutional review board where the research entailed animal or human participation.

The cohorts receive annual ethics approval from the University of British Columbia / Providence Health Care research ethics board (ACCESS: H05-50233, VIDUS: H05-50234 / H14-01396).

REFERENCES

- Allen B, Nolan ML, & Paone D (2019). Underutilization of medications to treat opioid use disorder: What role does stigma play? Substance Abuse, 40(4), 459–465. 10.1080/08897077.2019.1640833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altman DG (1991). Practical statistics for medical research. London: Chapman & Halll. [Google Scholar]

- Amram O, Socias E, Nosova E, Kerr T, Wood E, DeBeck K, et al. (2019). Density of low-barrier opioid agonist clinics and risk of non-fatal overdose during a communitywide overdose crisis: A spatial analysis. Spatial and Spatio-Temporal Epidemiology, 30, Article 100288. 10.1016/j.sste.2019.100288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armitage P (1955). Tests for linear trends in proportions and frequencies. Biometrics, 11(3), 375–386. [Google Scholar]

- Bazazi AR, Yokell M, Fu JJ, Rich JD, & Zaller ND (2011). Illicit use of buprenorphine/naloxone among injecting and noninjecting opioid users. Journal of Addiction Medicine, 5(3), 175–180. 10.1097/ADM.0b013e3182034e31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BC Centre for Disease Control Overdose Response Indicators. Accessed Nov 14, 2021. (2021). Retrieved from http://www.bccdc.ca/health-professionals/data-reports/overdose-response-indicators.

- BC Opioid Substitution Treatment System: Performance Measures 2014/2015 – 2015/2016. (2017). Office of the provincial health officer, Victoria BC. [Google Scholar]

- Bi-Mohammed Z, Wright NM, Hearty P, King N, & Gavin H (2017). Prescription opioid abuse in prison settings: A systematic review of prevalence, practice and treatment responses. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 171, 122–131. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- British Columbia Centre on Substance Use. (2017). A guideline for the clinical management of opioid use disorder Vancouver, Canada.

- Carlson RG, Daniulaityte R, Silverstein SM, Nahhas RW, & Martins SS (2020). Unintentional drug overdose: Is more frequent use of non-prescribed buprenorphine associated with lower risk of overdose? International Journal of Drug Policy, 79, Article 102722. 10.1016/j.drugpo.2020.102722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crabtree A, Lostchuck E, Chong M, Shapiro A, & Slaunwhite A (2020). Toxicology and prescribed medication histories among people experiencing fatal illicit drug overdose in British Columbia, Canada. CMAJ: Canadian Medical Association Journal (journal de l’Association medicale canadienne), 192(34), E967–E972. [Google Scholar]

- Darke S (1998). Self-report among injecting drug users: A review. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 51(3), 253–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doernberg M, Krawczyk N, Agus D, & Fingerhood M (2019). Demystifying buprenorphine misuse: Has fear of diversion gotten in the way of addressing the opioid crisis? Substance Abuse, 40(2), 148–153. 10.1080/08897077.2019.1572052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gowing L, Farrell MF, Bornemann R, Sullivan LE, & Ali R (2011). Oral substitution treatment of injecting opioid users for prevention of HIV infection. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 10(8), Article CD004145. 10.1002/14651858.CD004145.pub4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho J, DeBeck K, Milloy MJ, Dong H, Wood E, Kerr T, et al. (2018). Increasing availability of illicit and prescription opioids among people who inject drugs in a Canadian setting, 2010–2014. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 44(3), 368–377. 10.1080/00952990.2017.1376678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lofwall MR, & Walsh SL (2014). A review of buprenorphine diversion and misuse: The current evidence base and experiences from around the world. Journal of Addiction Medicine, 8(5), 315–326. 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattick RP, Breen C, Kimber J, & Davoli M (2014). Buprenorphine maintenance versus placebo or methadone maintenance for opioid dependence. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 6(2), Article CD002207. 10.1002/14651858.CD002207.pub4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Platt L, Minozzi S, Reed J, Vickerman P, Hagan H, French C, et al. (2017). Needle syringe programmes and opioid substitution therapy for preventing hepatitis C transmission in people who inject drugs. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 9, Article CD012021. 10.1002/14651858.CD012021.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddon H, Ho J, DeBeck K, Milloy MJ, Liu Y, Dong H, et al. (2018). Increasing diversion of methadone in Vancouver, Canada, 2005–2015. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 85, 10–16. 10.1016/j.jsat.2017.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strathdee SA, Patrick DM, Currie SL, Cornelisse PG, Rekart ML, Montaner JS, et al. (1997). Needle exchange is not enough: Lessons from the Vancouver injecting drug use study. AIDS, 11(8), F59–F65. 10.1097/00002030-199708000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vranken MJM, Mantel-Teeuwisse AK, Junger S, Radbruch L, Scholten W, Lisman JA, et al. (2017). Barriers to access to opioid medicines for patients with opioid dependence: A review of legislation and regulations in eleven central and eastern European countries. Addiction, 112(6), 1069–1076. 10.1111/add.13755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh SL, Preston KL, Stitzer ML, Cone EJ, & Bigelow GE (1994). Clinical pharmacology of buprenorphine: Ceiling effects at high doses. Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics, 55(5), 569–580. 10.1038/clpt.1994.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weicker SA, Hayashi K, Grant C, Milloy MJ, Wood E, & Kerr T (2019). Willingness to take buprenorphine/naloxone among people who use opioids in Vancouver, Canada. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 205, Article 107672. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.107672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu LT, Zhu H, & Swartz MS (2016). Treatment utilization among persons with opioid use disorder in the United States. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 169, 117–127. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeger SL, & Liang KY (1986). Longitudinal data analysis for discrete and continuous outcomes. Biometrics, 42(1), 121–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]