Abstract

Preeclampsia (PE) is a hypertensive pregnancy, which is a leading cause of maternal and fetal morbidity and mortality during pregnancy. L-Tryptophan (Trp) is an essential amino acid, which can be metabolized into various biologically active metabolites. However, the levels of many circulating Trp-metabolites in human normotensive pregnancies (NT) and PE are undetermined. This study quantified the levels of Trp-metabolites in maternal and umbilical vein sera from women with NT and PE. Paired maternal and umbilical blood samples were collected from singleton pregnant patients. Twenty-five Trp-metabolites were measured in serum samples using Liquid Chromatography with Tandem Mass Spectrometry. The effects of L-Kynurenine (Kyn) and Indole-3-lactic acid (ILA), on function of human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) were also determined. Twenty Trp-metabolites were detected. The levels of 9 Trp-metabolites including Kyn and ILA were higher (P < 0.05) in umbilical vein than maternal serum, whereas 2 (5-hydroxy-L-Tryptophan and Serotonin) were lower (P < 0.05) in umbilical vein compared to maternal serum. PE significantly (P < 0.05) elevated ILA levels in maternal and umbilical vein sera. Kyn dose-dependently decreased (P < 0.05) cell viability. Kyn and ILA dose- and time-dependently (P < 0.05) increased monolayer integrity in HUVECs. These data suggest that these Trp-metabolites are important in regulating endothelial function during pregnancy, and the elevated ILA in PE may antagonize increased endothelial permeability occurring in PE.

Keywords: Tryptophan-metabolites, Pregnancy, Preeclampsia, Circulations, Endothelial function

1. Introduction

Preeclampsia (PE) is a hypertensive disorder in human pregnancy (1). While primarily defined as maternal new-onset hypertension (1), PE causes fetal endothelial dysfunction including increased monolayer permeability and decreased nitric oxide (NO) production (2–4). PE also decreases endothelial angiogenic responses and endothelial NO synthase (eNOS) expression (5,6). These PE-induced endothelial dysfunctions may be attributed to dysregulation of gene expression (4,7). PE is also a well-established pro-inflammatory state characterized by dysregulation of cytokine production and immune cell differentiation (1). The mechanisms governing PE-dysregulated vascular and immune cell function, particularly in the fetal compartment, remain poorly defined. Thus, further deciphering these mechanisms will help us develop novel therapies and predictors for PE.

L-Tryptophan (Trp) is an essential amino acid in humans. While a small fraction (≤ 1%) of dietary Trp is used for protein synthesis, 95% of free Trp is metabolized through the oxidation pathway (kynurenine [Kyn] pathway) (Fig. S1) (8–10). The Trp-metabolism pathway generates diverse biologically active metabolites, e.g., Kyn, Indole-3-lactic acid (ILA), serotonin (or 5-hydroxytryptamine [5-HT]), and melatonin (MLT), which regulate many biological processes including vascular development, neuro growth, and immune response (8–10). For example, both Trp and Kyn have been shown to induce vasorelaxation in mice and porcine coronary arteries (11). We have also reported that a prospective Trp-metabolite inhibits angiogenic responses in human umbilical vein (HUVECs) and artery endothelial cells (12,13). Kyn can induce the differentiation of T cells into immunosuppressive Treg cells (14). ILA can decrease H17 polarization and suppresses inflammatory T cells (15,16). During pregnancy, Trp is required for increased protein synthesis to support fetal growth and for suppressing immune responses to prevent fetal rejection (10,17). Total maternal plasma Trp levels are relatively lower in pregnant vs. non-pregnant women and decrease as the pregnancy progresses, whereas free Trp levels increase during pregnancy (10). The ratio of Kyn/Trp increases during pregnancy, suggesting enhanced Kyn metabolism (18). A potential role of excess Trp and its metabolites in PE has been proposed, as placental(19) and maternal plasma Trp concentrations are elevated in PE (18,20). These elevated Trp levels could be associated with decreases in expression of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO, a rate-limiting enzyme for the Kyn pathway) and Trp-metabolic activity in PE placentas (17,21,22). Recently, Trp has been shown to pharmacologically induce vasodilation of human placental chorionic arteries after pretreated with interferon gamma (IFNγ) and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα) ex vivo (19,23). Kyn can also cause vasorelaxation of maternal omental and myometrial, but not placental chorionic arteries from normal pregnancy and PE ex vivo (24). In addition, the elevated levels of 5-HT in maternal and umbilical plasma from PE may also contribute to vascular dysfunction in PE (25,26).

Little is known about the physiological levels and roles of Trp-metabolites in normotensive (NT) pregnancies and PE, particularly in the fetus. In this study, we hypothesized that PE dysregulates the Trp-metabolism pathway in maternal and fetal compartments, contributing to endothelial dysfunction. We profiled Trp-metabolites in maternal and umbilical vein sera from women with NT and PE using Liquid Chromatography with Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) analysis. To explore roles of these Trp-metabolites in endothelial cells, we also determined the effects of Kyn and ILA on cell viability and monolayer integrity in HUVECs.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Collection and Preparation of Maternal and Umbilical Vein Blood Samples

Paired maternal and umbilical vein blood samples were collected from singleton pregnant patients by the staff from the Tissue Bank of Shanghai First Maternity and Infant Hospital as described (27). PE was defined according to the standard American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Criteria. Whole maternal blood was collected from patients with NT (n = 20 with 10 female and 10 male fetuses) and PE (n = 20 with 10 female and 10 male fetuses) (Table 1) before delivery via venipuncture. Umbilical vein blood was collected immediately after delivery. The umbilical vein blood carries oxygen-rich blood from the mother and placenta to the fetal inferior vena cava via the ductus venosus to the heart that then pumps blood into the fetus. Thus, umbilical vein blood represents part of fetal circulation. To sufficiently remove the cells and clotting factors from the samples, blood samples were allowed to stand at room temperature (about 18 °C) for 1 hr, followed by centrifuging at 2000 g for 30 min at 4 °C. Maternal and umbilical vein sera were collected, aliquoted and stored at −80 °C until assayed. All the patients who underwent scheduled Cesarean section fasted for 6 to 12 hr before their surgery. The fasting status of one patient who underwent a natural delivery was not recorded, and was assumed to be non-fasting.

Table 1.

Patient demographic and clinical characteristics*

| Characteristics | NT (n = 20) | PE (n = 20) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal age (years) | 31.9 ± 0.83 | 32.3 ± 0.88 | 0.742 |

| Gestational BMI (kg/m2) | 26.1 ± 0.73 | 28.4 ± 0.83 | 0.021 |

| Pre-pregnancy BMI (kg/m2) | 21.0 ± 0.56 | 23.1 ± 0.85 | 0.014 |

| ART, n (%) | 2 (10%) | 1 (5%) | 0.548 |

| Multigravida, n (%) | 13 (65%) | 11 (55%) | 0.519 |

| Multiparous, n (%) | 10 (50%) | 6 (30) | 0.197 |

| Gestational age (weeks) | 38.8 ± 0.19 | 37.5 ± 0.49 | 0.041 |

| Male fetus, n (%) | 10 (50%) | 10 (50%) | 1.000 |

| Birth weight (grams) | 3388.3 ± 94.66 | 2979.3 ± 156.58 | 0.031 |

| Cesarean section, n (%) | 20 (100%) | 19 (95%) | 0.311 |

| Blood pressure (mmHg) | |||

| Systolic | 115.7 ± 2.30 | 147.0 ± 3.64 | <0.001 |

| Diastolic | 73.2 ± 1.83 | 91.8 ± 2.26 | <0.001 |

| MAP | 87.4 ± 1.71 | 110.2 ± 2.61 | <0.001 |

| Proteinuria (grams/24 h) | -- | 1.0 ± 0.24 | |

All patients are Han Chinese without current or history of other major complications. All data are presented as means ± standard error of the mean (SEM) or n (%). NT: normotensive pregnancy; PE: preeclampsia. BMI: Body mass index; ART: assisted reproductive technology; MAP: mean artery pressure.

2.2. LC-MS/MS Analysis for Trp-Metabolites in Maternal and Umbilical Vein Sera

2.2.1. LC-MS/MS Quality Control

LC-MS/MS analysis was performed by Shanghai Applied Protein Technology, Shanghai, China. 25 Trp-metabolites were measured (Table S1). All Trp-metabolites standards were commercially purchased (Table S1). The standard curves of Trp-metabolites are shown in Table S1. Each standard tested is within the linear range with the correlation coefficients greater than 0.99 (Table S1). An equal amount of serum sample from each individual patient was pooled to prepare a quality control (QC) sample, which was used to determine the stability of the detection assay. The relative standard deviation (RSD%) of each tested standard is less than 30%, indicating that the experimental data is stable and reliable.

2.2.2. LC-MS/MS

A serum sample (100 μL) from each patient was mixed with 0.4 ml of extraction solution (acetonitrile: methanol = 1:1), followed by ultrasound extraction for 20 min. The mixture was centrifuged at 14,000 xg and 4°C for 15 min. The supernatant was transferred to an autosampler vial for LC-MS/MS analysis.

Metabolite mixtures were separated using reversed-phase (CSH C18 1.7 μm, 2.1 mm×100 mm column, Waters, Milford, MA) using the UHPLC 1290 system (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). Mobile phases A (20 mM ammonium formate and 0.2% formic acid in water) and B (0.2% formic acid in methanol) were used. Metabolite mixtures (2 μL injection/sample) were loaded on the C18 column and re-equilibrated for 2 min at 400μl/ min using mobile phase B (100% MeOH in 0.2% formic acid). The column temperature was set at 25 °C. Chromatographic separation was achieved by gradient elution at a flow rate of 0.4 mL/min. The gradient program was as follows: 15% B, 0–2 min; 15–98% B, 2–9 min; 98% B, 9 −11min; 98% −15% B, 11–11.5 min; column re-equilibration, 11.5–14 min. The total run time was 14 min.

Eluent from the column was introduced to the MS system using the NanoSpray Source into an AB SCIEX 5500 system (AB SCIES, Framingham, MA) with Analyst Software TF 1.6 and the variable window acquisition beta patch. The multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) for positive and negative ionization modes acquisition methods were built using the Acquisition method editor. Parameters in positive ionization modes: Source temperature, 550 °C; Gas 1, 55; Gas 2, 50; CRU, 30; ISVF, 5500 V Parameter in negative ionization modes: Source temperature, 550° C Gas 1, 55; Gas 2, 50; CRU, 30; ISVF, −4500 V).

2.3. Effects of Kyn and ILA on Cell Viability and Monolayer Integrity of HUVECs

2.3.1. HUVECs

HUVECs were isolated from umbilical veins of women with NT as previously described (4,7,12,13). After isolation, cells were cultured in endothelial culture medium (ECM) which consisted of ECM-basal (ECMb; #1001 Sciencell, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1% penicillin/streptomycin (p/s), and 1% endothelial cell growth supplement. After verification of their endothelial phenotypes, cells were pooled from 5 individual cell preparations at passage 1 to reduce inter-cell preparation variations and cultured (12,13,28). These pooled cells at passage 4 were used for functional studies described below. We chose Kyn and ILA to test the effects of Trp-metabolites on cellular responses in HUVECs since both have been reported to actively participate in regulation of cellular function(11), (14),(19,23,24)). Additionally, we found that ILA was the only Trp-metabolite which was elevated in PE-maternal and -umbilical sera in the current study.

2.3.2. Cell Viability

Cell viability was assayed using the crystal violet method as described (12,13,28). Subconfluent HUVECs were seeded in 96-well plates (10,000 cells/well). After 16 hr of culture, cells were treated with 1.25, 2.5, 5, 10, or 20 μM of Kyn (Cat #: K8625) or ILA (Cat #: I5508) in ECMb supplemented with 0.2% heated inactivated FBS and 1% p/s up to 2 days (5 wells/treatment). Stock solutions of Kyn and ILA were prepared in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, Cat # D2650). Additional cells were treated with the vehicle control (DMSO, 0.02% v/v; the maximum concentration in the final Kyn and ILA solutions). Kyn, ILA, and DMSO were all purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA. Media were changed with ECMb containing Kyn, ILA, or DMSO daily. At the end of treatment, the optical density value of each well was measured using a microplate reader at 570 nm (Biotek, Winooski, VT, USA).

2.3.3. Cell Monolayer Integrity

Cell monolayer integrity was examined using an electric cell-substrate impedance sensing (ECIS) system (Applied Biophysics, Troy, NY, USA) as described (7,28–30). HUVECs (20,000 cells/well) were inoculated into 96W10idfECIS array plates (Applied Biophysics) pre-coated with 10 nM cysteine and 0.1% gelatin, and cultured in ECM. The resistance of each electrode was monitored at 4000 Hz. After culturing for 48 h, the resistance reached a plateau, indicating 100% confluence. Cells were treated with 2.5, 5, or 10 μM of Kyn or ILA. Additional cells were treated with the vehicle control (DMSO, 0.02% v/v). Changes in resistance were monitored for additional 25 h.

2.4. Statistical analyses

For the LC-MS/MS analysis, the data matrix files obtained were used as input for statistical analysis using MultiQuant or Analyst (SCIEX). The original data obtained were normalized to the internal isotopic standard. Statistical analyses were performed using SigmaPlot software (Systat Software, San Jose, CA). The Two-way ANOVA with all pairwise multiple comparison was performed using Holm-Sidak tests. Normality of distribution was assessed by Shapiro-Wilk tests. All data except 2 Trp-metabolites were non-normally distributed. The two factors were patient groups (PE and NT) and sera sources (maternal and umbilical vein). Data are presented as the medians ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Pearson Product Moment Correlation Analysis was utilized to determine the correlation coefficient among different Trp-metabolites and patient characteristics. Benjamini and Hochberg false discovery rate (FDR)-adjustment was used for the multiple comparison and correction. Differences were considered significant when P < 0.05.

For the cell viability and permeability assays, data were analyzed using Friedman one-way repeated measures ANOVA. When an F-test was significant, data were analyzed using Holm-Sidak tests (multiple comparisons versus control group). Differences were considered significant when P < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Trp-metabolites in maternal and umbilical vein sera

3.1.1. Patients’ demographics

The demographic and clinical characteristics of patients are shown in Table 1. Forty serum samples were from equal numbers of NT and PE patients (20 each). All patients except 1 in the PE group underwent scheduled Cesarean section delivery. There were 3 samples from early onset PE (1 from PE with female fetus and 2 from male fetus) and 1 from late onset PE with a growth restricted male fetus. Each NT and PE group had an equal number of fetal sex (n = 10 female and male fetuses per group). Pre-gestational and pregnancy BMI were slightly, but significantly (P < 0.05) higher in PE vs. NT, while gestational ages were lower (P < 0.05) in PE vs. NT. Fetal birth weights were lower (P < 0.05) in PE vs. NT. Fetuses in the PE group at 38 weeks of gestation were not growth restricted as their weights were within the 90th percentile for gestational age (31,32). The levels of systolic, diastolic, and mean artery pressure were higher (P < 0.05) in PE vs NT. None of NT patients developed proteinuria, whereas 90% PE patients had proteinuria.

3.1.2. Differential distribution of Trp-metabolites in Maternal and umbilical sera from NT and PE

Of 25 Trp-metabolites measured, 20 were detected in both maternal and umbilical sera (Table 2). Of these 20 Trp-metabolites, median Trp concentrations were highest in maternal (~36 μM) and umbilical (~ 63 μM) sera, while MLT only reached 2 nM and IBDG was barely detected in maternal and umbilical sera. The concentrations of 9 Trp-metabolites (Trp, NFK, Kyn, 3-HK, 3-HAA, QA, CVI, ILA, and IAA) were higher (P < 0.05) in umbilical than maternal sera, whereas the concentrations of L-5-HTP in NT and 5-HT in both NT and PE were higher (P < 0.05) in maternal than umbilical sera (Table 2). Importantly, the concentration of ILA was significantly (P < 0.05) elevated in PE-maternal (35% above NT) and PE-umbilical (31% above NT) sera. Of 20 Trp-metabolites detected, no fetal sex-specific effect was found.

Table 2.

Trp-metabolites in maternal and umbilical vein sera.*

| Maternal Serum | Umbilical Vein Serum | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Trp Metabolite (Abbreviation) | NT (n = 20) | PE (n = 20) | NT (n = 20) | PE (n = 20) | |

| 1. | L-Tryptophan (Trp) | 34.479±1.318a | 36.996±1.240a | 64.104±1.306b | 62.649±1.452b |

| 2. | N-formyl-kynurenine (NFK) | 0.175±0.028a | 0.216±0.021a | 0.407±0.054b | 0.393±0.098b |

| 3. | L-Kynurenine (Kyn) | 0.845±0.104a | 0.939±0.108a | 1.782±0.249b | 2.035±0.296b |

| 4. | Kynurenic acid (KA) | 0.023±0.004 | 0.024±0.003 | 0.022±0.002 | 0.023±0.002 |

| 5. | 3-Hydroxylkynurenine (3-HK) | 0.196±0.010a | 0.238±0.010a | 0.272±0.012b | 0.271±0.007b |

| 6. | Xanthinenic acid (XA) | 0.118±0.029 | 0.124±0.027 | 0.315±0.047 | 0.281±0.033 |

| 7. | 3-Hydroxyanthranilic acid (3-HAA) | 0.287±0.033a | 0.288±0.035a | 0.448±0.040b | 0.428±0.051b |

| 8. | Quinolinic acid (QA) | 1.333±0.073a | 1.593±0.063a | 2.343±0.121b | 2.531±0.163b |

| 9. | Picolinic acid (PA) | 0.223±0.025 | 0.227±0.019 | 0.287±0.008 | 0.294±0.009 |

| 10. | Cinnavalininate (CVI) | 4.857±0.669a | 3.926±0.621a | 10.142±0.695b | 8.740±1.197b |

| 11. | Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD) | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| 12. | 5-hydroxy-L-Tryptophan (L-5-HTP) | 0.240±0.032a | 0.210±0.030ab | 0.153±0.007b | 0.171±0.009b |

| 13. | Serotonin (5-HT) | 0.401±0.028a | 0.357±0.046a | 0.126±0.016b | 0.101±0.021b |

| 14. | Melatonin (MLT) | 0.002±0.000 | 0.002±0.000 | 0.002±0.000 | 0.002±0.000 |

| 15. | 5-Hydroxyindole-3-acetic acid (5-HIAA) | 0.041±0.024ab | 0.042±0.011a | 0.109±0.005b | 0.093±0.011ab |

| 16. | Indole (ID) | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| 17. | 3-Indoxyl sulfate (3-IS)§ | 2.888±0.674 | 2.406±0.373 | 4.473±0.755 | 3.545±0.504 |

| 18. | Indoxyl-b-D-glucuronide (IBDG) | 0.000±0.007 | 0.000±0.013 | 0.000±0.003 | 0.000±0.002 |

| 19. | Indole-3-carboxaldehyde (I3CA) | 0.036±0.007 | 0.027±0.005 | 0.028±0.002 | 0.026±0.005 |

| 20. | 3-Methyl-indole (3-MI) | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| 21. | Indole-3-lactic acid (ILA) | 1.251±0.069a | 1.685±0.172b | 2.993±0.156c | 3.917±0.223d |

| 22. | Indole-3-propionic acid (IPA) | 2.653±6.595 | 2.325±0.677 | 2.293±9.500 | 3.000±0.770 |

| 23. | Tryptamine (TRM)§ | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| 24. | Indole-3-acetaldehyde (IAAId) | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| 25. | Indoleacetate (IAA)§ | 1.051±0.135a | 1.340±0.098a | 2.724±0.287b | 2.791±0.171b |

All values are expressed as medians ± SEM μM. ND: not detected.

Medians with different superscript letters differ from each other (P < 0.05).

3.1.3. Correlations between Trp-metabolite levels and patients’ demographic characteristics

We identified 2 correlations in PE-maternal serum, in which KA (r = 0.684, P < 0.025) and PA (r = 0.641, P < 0.031) were positively correlated with proteinuria. No correlation was found in any umbilical vein Trp-metabolites (not shown).

3.2. Effects of Kyn and ILA on cell viability and monolayer integrity in HUVECs

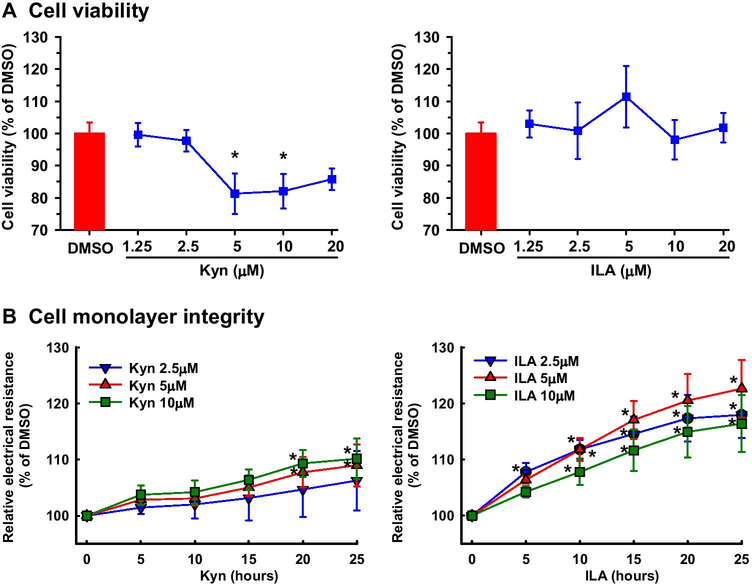

Kyn decreased (P < 0.05) cell viability by ~19 and 18% at 5 and 10 μM, respectively, and slightly but not statistically significantly decreased cell viability at 20 μM (Fig. 1A). Kyn at 2.5 μM had no effect on cell viability. ILA at any dose studied did not significantly affect cell viability (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1.

Effects of Kyn and ILA on cell viability and monolayer integrity in HUVECs. Cell viability (A) and cell monolayer integrity (B) were determined using the crystal violet method and ECIS system, respectively. Cells were seeded into 96 well plates. After culture for 16 hr (viability) or 48 hr (monolayer integrity) in ECM, cells were treated with Kyn, ILA, or DMSO (vehicle control) in ECMb for up to 48 (viability) or 25 hr (cell monolayer integrity). Data are expressed as means ± SEM of the fold of DMSO (viability) or DMSO at each corresponding time point (monolayer integrity). Means with asterisks significantly differ from DMSO control (viability) or DMSO control at each corresponding time (monolayer integrity). n = 4 independent experiments. P < 0.05.

Both Kyn and ILA dose- and time-dependently increased (P < 0.05) the electrical resistance of the cell monolayer (Fig. 1B), indicating strengthened cell monolayer integrity. Kyn at 2.5 μM had no significant effect on the electrical resistance of the cell monolayer (Fig. 1B), whereas Kyn at 5 and 10 μM similarly increased (P < 0.05) the electrical resistance at 20 and 25 hr with a maximum effect (~10%) at 25 hr (Fig. 1B). ILA at 2.5 significantly increased (P < 0.05) the electrical resistance from 5 to 25 hr (Fig. 1B). ILA at 5 and 10 μM μM increased the electrical resistance, starting at 10 hr and reaching the maximum enhancing effect (23%) at 25 hr.

Discussion

In this study, we measured 25 Trp-metabolites in maternal and umbilical vein sera from women with NT and PE. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first profiling on the levels of these 25 Trp-metabolites in PE-fetal circulations. More importantly, we have demonstrated that PE elevates the concentration of ILA in both maternal and fetal circulations. We have also shown that Kyn and ILA differentially regulate endothelial viability and monolayer integrity in HUVECs. These data support the notion that Trp-metabolites are important in endothelial function during pregnancy. Together with the observation that ILA strengthens endothelial integrity of HUVECs, the PE elevated-ILA might antagonize PE-increased endothelial permeability. In this study, no causal effect of these Trp-metabolites on PE is established. Actually, it is unlikely that an elevation of a single Trp-metabolite, ILA could induce PE. However, as many other yet- to-be determined Trp-metabolites (e.g., Glucobrassicin, Isophenoxazine, Methoxykynurenate, and Skatole) might present during pregnancy, we still cannot exclude the possibility that an overall elevation of Trp-metabolites might contribute to the etiology of PE.

The levels of Trp we detected largely fall within ranges previously reported (10,33–36). For instance, the overall levels of Trp in maternal (~ 35.8 μM) and umbilical (~ 62 μM) sera detected in the current study is similar to the circulating total Trp-levels in maternal (~ 37.9 μM, ranging from 25–53 μM) and in umbilical (~78 μM, ranging from 56–101 μM) sera(10). The levels of Kyn, KA, and 5-HTP in maternal serum are also comparable to those previously reported (33,35). However, the levels of 3-HK, XA, and 3-HAA we measured in maternal serum are much higher (~ 5–10 fold) than those previously reported (33). Our observation that PE does not elevate Trp and Kyn in either maternal or fetal serum is consistent with the previous reports (25,33), in which PE did not change Trp and Kyn levels in maternal serum from the 2nd trimester of pregnancy (33), nor did PE alter Trp levels in umbilical serum from the 3rd trimester (25). However, our observation contradicts the study by Grafka et al. who demonstrated a 2.8 fold increase of Trp in PE-maternal serum from the 3rd trimester (20). In addition, we do not find increases in KA and 5-HT, nor do we see a decrease in MLT in PE-maternal serum and increases in 5-HT and 5-HIAA in PE-umbilical vein serum (25). It is unclear what causes these discrepancies, but different detection methods and different patient cohorts might contribute to such differences. For example, increased 5-HT and 5-HIAA levels in umbilical vein serum were detected only in severe, but not mild PE (25). Additionally, a relatively low of KA was detected in a large cohort of PE patients including those with hemolysis, Elevated Liver enzymes and Low Platelets (HELLP) and eclampsia (33). However, in the current study, mild PE patients are included and all PE patient are without HELLP and eclampsia.

Trp is primarily metabolized by the gut microbe, in livers, and in placentas (8–10). Our current finding that the levels of 9 Trp-metabolites are higher in umbilical vein vs. maternal serum is not surprising since similar elevations in umbilical blood have been reported for Trp, Kyn, KA, XA, 3-HAA, IPA, ILA, and IAA (36,37). These high levels of Trp-metabolites in umbilical vein serum support the notion that the placenta is a major source for these Trp-metabolites at term (10). Alternatively, enhanced transportation across the placenta from the maternal circulation could also contribute to these increases.

Though elevated Kyn, KA, and 5-HT as well as decreased MLT in PE-maternal serum have been reported (20,26,33,38), we do not detect significant differences in Kyn, KA, 5-HT, or MLT in either maternal or umbilical serum between NT and PE. However, we found that ILA was elevated in PE-maternal and umbilical vein sera. One explanation for PE-elevated ILA is that PE inhibits expression and/or activity of phenyllactate dehydrogenase and acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (two enzymes responsible for converting ILA to IPA (Fig. S1) (39) in placentas. Trp-metabolites are important in regulating maternal and fetal cell function during pregnancy (8–10,40). This is further supported by our current findings that Kyn and ILA differentially regulate cell viability and monolayer integrity in HUVECs. In this regard, Kyn at the physiological level (the overall Kyn concentration in umbilical serum is 1.9 μM) does not significantly affect cell viability and monolayer integrity. However, Kyn at relatively higher levels (5 and 10 μM) reduces viability of HUVECs. These data suggest the harmful action of excess Kyn on endothelial cells. Our observation that PE elevates ILA in both maternal and umbilical sera implies potential importance of ILA in PE. This is consistent with the evidence that ILA possesses anti-inflammatory activity as it reduces TH17 polarization and suppresses inflammatory T cells (15,16). In addition, ILA promotes neurite outgrowth (41) as an antioxidant and free-radical scavenger (42). In the current data, although ILA at 2.5 and 5 μM (overall ILA concentrations in NT- and PE-umbilical serum are 2.99 and 3.92 μM; respectively) both increase monolayer integrity in HUVECs, the effect of ILA at 5 μM appeared to be more potent compared with that at 2.5 μM in HUVECs. Thus, elevating ILA in PE is likely to be a protective mechanism against PE-decreased endothelial monolayer integrity (43). To date, it remains to be investigated how Kyn and ILA induce these cellular responses in HUVECs. However, as both Kyn and ILA are aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR, a ligand-activated transcription factor) ligands (8,9,39,44), their actions might be mediated via the AhR signaling pathway (40,44).

It is worthy noting that many additional Trp-metabolites such as 2-(1’H-indole-3’-carbonyl)-thiazole-4-carboxylic acid methyl ester and Indole-3-carbinol derivatives (40,44) may be present and function during pregnancy. Further research is required to dissect the roles of these Trp-metabolites in pregnancy.

Though relatively small variations in patients’ demographic characteristics (Table 1), 2 correlations were identified in Trp-metabolites from PE-maternal serum, in which KA and PA (both are in the Kyn pathway) were positively correlated to proteinuria. This is in line with the observations that increases in many products (e.g., Kyn, KA, 3-HK, XA, 3-HAA, and QA) of the Kyn pathway in circulation are linked to chronic kidney disease (45), in which elevated KA is associated with proteinuria in animals and humans (46). These data suggest that these 2 Trp-metabolites might be actively involved in proteinuria in PE.

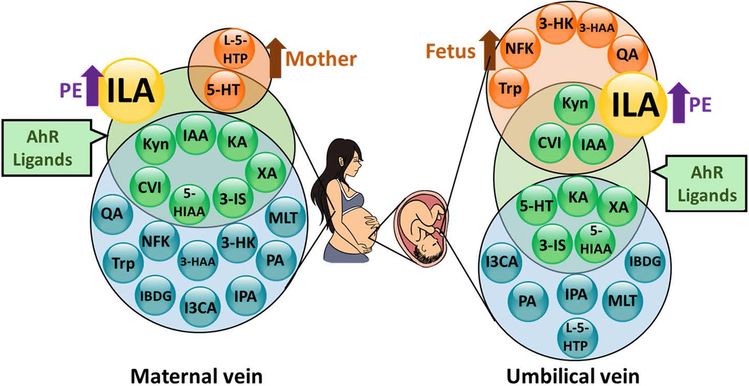

In conclusion, we have successfully quantified 20 Trp-metabolites in maternal and fetal circulations from NT and PE (Fig. 2). The levels of 9 Trp-metabolites are higher in fetal vs maternal sera, whereas 2 are higher in maternal vs fetal sera. ILA is increased in both maternal and fetal circulations from PE pregnancies. We also observed that Kyn and ILA differentially regulate endothelial viability and monolayer integrity. These data support the importance of Trp-metabolites in the mother and fetus during pregnancy.

Fig. 2.

A diagram summary for Trp-metabolites detected in maternal and umbilical vein sera from NT and PE. Purple arrows indicate increases in ILA in PE vs NT; Dark orange arrows indicate that Trp-metabolites in orange circles are higher in maternal vs fetal serum (left panel) or in fetal vs maternal serum (right panel).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments:

We would like to thank Laura Hogan, Ph.D., a Science Writer/Editor with the UW ICTR, for critically reading and editing this manuscript. We also thank Ms. Susanna Zheng, UW-Madison for preparing the figure for this publication.

Funding: This study is supported by the NIH grants RO3 HD100778 (CZ), as well as American Heart Association awards 17POST33670283 and 19CDA34660348 (CZ). The project was also supported by Translational Basic and Clinical Pilot Award (JZ and CZ) from the UW Institute for Clinical and Translational Research (ICTR) and the Clinical and Translational Science Award program, through the NIH National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, grant UL1TR002373.

Footnotes

Declarations: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethics Approval: All procedures were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All the tissue samples were collected with written informed consent. The blood sample collection was approved by the Scientific and Ethical Committee of Shanghai First Maternity and Infant Hospital, Tongji University (Protocol number: KS2013, approved on April 20, 2020). For HUVECs, the umbilical cord collection was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Meriter Hospital, and the Health Sciences Institutional Review Boards of the University of Wisconsin-Madison (Protocol number 2004–006, approved on July 26, 2018).

Consent: All patients consented to participate and for publication with de-identified patients’ information.

Data Availability: Additional supporting data are available in the online-only Data Supplement.

References

- 1.Rana S, Lemoine E, Granger JP, and Karumanchi SA (2019) Preeclampsia: Pathophysiology, Challenges, and Perspectives. Circ Res 124, 1094–1112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boeldt DS, Hankes AC, Alvarez RE, Khurshid N, Balistreri M, Grummer MA, Yi F, and Bird IM (2014) Pregnancy programming and preeclampsia: identifying a human endothelial model to study pregnancy-adapted endothelial function and endothelial adaptive failure in preeclamptic subjects. Adv Exp Med Biol 814, 27–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang Y, Gu Y, Zhang Y, and Lewis DF (2004) Evidence of endothelial dysfunction in preeclampsia: decreased endothelial nitric oxide synthase expression is associated with increased cell permeability in endothelial cells from preeclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol 190, 817–824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhou C, Yan Q, Zou QY, Zhong XQ, Tyler CT, Magness RR, Bird IM, and Zheng J (2019) Sexual Dimorphisms of Preeclampsia-Dysregulated Transcriptomic Profiles and Cell Function in Fetal Endothelial Cells. Hypertension 74, 154–163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Addis R, Campesi I, Fois M, Capobianco G, Dessole S, Fenu G, Montella A, Cattaneo MG, Vicentini LM, and Franconi F (2014) Human umbilical endothelial cells (HUVECs) have a sex: characterisation of the phenotype of male and female cells. Biology of Sex Differences 5, 18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rasiah RL, Addison RS, Roberts MS, and Mortimer RH (1997) An isolated perfused human placental lobule model for multiple indicator dilution studies. Journal of Pharmacological and Toxicological Methods 38, 19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhou C, Zou Q. y., Li H, Wang R. f., Liu A. x., Magness RR, and Zheng J (2017) Preeclampsia Downregulates MicroRNAs in Fetal Endothelial Cells: Roles of miR-29a/c-3p in Endothelial Function. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 102, 3470–3479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Platten M, Nollen EAA, Röhrig UF, Fallarino F, and Opitz CA (2019) Tryptophan metabolism as a common therapeutic target in cancer, neurodegeneration and beyond. Nat Rev Drug Discov 18, 379–401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roager HM, and Licht TR (2018) Microbial tryptophan catabolites in health and disease. Nat Commun 9, 3294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Badawy AA (2015) Tryptophan metabolism, disposition and utilization in pregnancy. Biosci Rep 35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang Y, Liu H, McKenzie G, Witting PK, Stasch JP, Hahn M, Changsirivathanathamrong D, Wu BJ, Ball HJ, Thomas SR, Kapoor V, Celermajer DS, Mellor AL, Keaney JF Jr., Hunt NH, and Stocker R (2010) Kynurenine is an endothelium-derived relaxing factor produced during inflammation. Nat Med 16, 279–285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li Y, Wang K, Zou Q. y., Jiang Y. z., Zhou C, and Zheng J (2017) ITE Suppresses Angiogenic Responses in Human Artery and Vein Endothelial Cells: Differential Roles of AhR. Reproductive Toxicology 74, 181–188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li Y, Wang K, Zou QY, Magness RR, and Zheng J (2015) 2,3,7,8-Tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin differentially suppresses angiogenic responses in human placental vein and artery endothelial cells. Toxicology 336, 70–78 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mezrich JD, Fechner JH, Zhang X, Johnson BP, Burlingham WJ, and Bradfield CA (2010) An interaction between kynurenine and the aryl hydrocarbon receptor can generate regulatory T cells. J Immunol 185, 3190–3198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cervantes-Barragan L, Chai JN, Tianero MD, Di Luccia B, Ahern PP, Merriman J, Cortez VS, Caparon MG, Donia MS, Gilfillan S, Cella M, Gordon JI, Hsieh CS, and Colonna M (2017) Lactobacillus reuteri induces gut intraepithelial CD4(+)CD8αα(+) T cells. Science 357, 806–810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wilck N, Matus MG, Kearney SM, Olesen SW, Forslund K, Bartolomaeus H, Haase S, Mähler A, Balogh A, Markó L, Vvedenskaya O, Kleiner FH, Tsvetkov D, Klug L, Costea PI, Sunagawa S, Maier L, Rakova N, Schatz V, Neubert P, Frätzer C, Krannich A, Gollasch M, Grohme DA, Côrte-Real BF, Gerlach RG, Basic M, Typas A, Wu C, Titze JM, Jantsch J, Boschmann M, Dechend R, Kleinewietfeld M, Kempa S, Bork P, Linker RA, Alm EJ, and Müller DN (2017) Salt-responsive gut commensal modulates T(H)17 axis and disease. Nature 551, 585–589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sedlmayr P, Blaschitz A, and Stocker R (2014) The role of placental tryptophan catabolism. Front Immunol 5, 230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kudo Y, Boyd CA, Sargent IL, and Redman CW (2003) Decreased tryptophan catabolism by placental indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase in preeclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol 188, 719–726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Broekhuizen M, Klein T, Hitzerd E, de Rijke YB, Schoenmakers S, Sedlmayr P, Danser AHJ, Merkus D, and Reiss IKM (2020) l-Tryptophan-Induced Vasodilation Is Enhanced in Preeclampsia: Studies on Its Uptake and Metabolism in the Human Placenta. Hypertension 76, 184–194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grafka A ŁM, Karwasik-Kajszczarek K, Stasiak-Kosarzycka M, Dzida G. (2018) Plasma concentration of tryptophan and pregnancy-induced hypertension. Arterial Hypertension 22, 9–15 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Keaton SA, Heilman P, Bryleva EY, Madaj Z, Krzyzanowski S, Grit J, Miller ES, Jälmby M, Kalapotharakos G, Racicot K, Fazleabas A, Hansson SR, and Brundin L (2019) Altered Tryptophan Catabolism in Placentas From Women With Pre-eclampsia. Int J Tryptophan Res 12, 1178646919840321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Santoso DI, Rogers P, Wallace EM, Manuelpillai U, Walker D, and Subakir SB (2002) Localization of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase and 4-hydroxynonenal in normal and pre-eclamptic placentae. Placenta 23, 373–379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zardoya-Laguardia P, Blaschitz A, Hirschmugl B, Lang I, Herzog SA, Nikitina L, Gauster M, Häusler M, Cervar-Zivkovic M, Karpf E, Maghzal GJ, Stanley CP, Stocker R, Wadsack C, Frank S, and Sedlmayr P (2018) Endothelial indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase-1 regulates the placental vascular tone and is deficient in intrauterine growth restriction and pre-eclampsia. Sci Rep 8, 5488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Worton SA, Pritchard HAT, Greenwood SL, Alakrawi M, Heazell AEP, Wareing M, Greenstein A, and Myers JE (2021) Kynurenine Relaxes Arteries of Normotensive Women and Those With Preeclampsia. Circ Res 128, 1679–1693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Taniguchi K, Okatani Y, and Sagara Y (1994) Serotonin metabolism in the fetus in preeclampsia. Asia Oceania J Obstet Gynaecol 20, 77–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Middelkoop CM, Dekker GA, Kraayenbrink AA, and Popp-Snijders C (1993) Platelet-poor plasma serotonin in normal and preeclamptic pregnancy. Clin Chem 39, 1675–1678 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jia L, Zhou X, Huang X, Xu X, Jia Y, Wu Y, Yao J, Wu Y, and Wang K (2018) Maternal and umbilical cord serum-derived exosomes enhance endothelial cell proliferation and migration. Faseb j 32, 4534–4543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zou QY, Zhao YJ, Li H, Wang XZ, Liu AX, Zhong XQ, Yan Q, Li Y, Zhou C, and Zheng J (2018) GNA11 differentially mediates fibroblast growth factor 2- and vascular endothelial growth factor A-induced cellular responses in human fetoplacental endothelial cells. J Physiol 596, 2333–2344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhou YJ, Yuan ML, Li R, Zhu LP, and Chen ZH (2013) Real-time placental perfusion on contrast-enhanced ultrasound and parametric imaging analysis in rats at different gestation time and different portions of placenta. PLoS One 8, e58986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zou QY, Zhao YJ, Zhou C, Liu AX, Zhong XQ, Yan Q, Li Y, Yi FX, Bird IM, and Zheng J (2019) G Protein α Subunit 14 Mediates Fibroblast Growth Factor 2-Induced Cellular Responses in Human Endothelial Cells. J Cell Physiol 234, 10184–10195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Williams RL, Creasy RK, Cunningham GC, Hawes WE, Norris FD, and Tashiro M (1982) Fetal growth and perinatal viability in California. Obstet Gynecol 59, 624–632 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhu L, Zhang R, Zhang S, Shi W, Yan W, Wang X, Lyu Q, Liu L, Zhou Q, Qiu Q, Li X, He H, Wang J, Li R, Lu J, Yin Z, Su P, Lin X, Guo F, Zhang H, Li S, Xin H, Han Y, Wang H, Chen D, Li Z, Wang H, Qiu Y, Liu H, Yang J, Yang X, Li M, Li W, Han S, Cao B, Yi B, Zhang Y, and Chen C (2015) [Chinese neonatal birth weight curve for different gestational age]. Zhonghua Er Ke Za Zhi 53, 97–103 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nilsen RM, Bjørke-Monsen AL, Midttun O, Nygård O, Pedersen ER, Ulvik A, Magnus P, Gjessing HK, Vollset SE, and Ueland PM (2012) Maternal tryptophan and kynurenine pathway metabolites and risk of preeclampsia. Obstet Gynecol 119, 1243–1250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Picone TA, Daniels TA, Ponto KH, and Pittard WB 3rd. (1989) Cord blood tryptophan concentrations and total cysteine concentrations. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 13, 106–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Carretti N, Bertazzo A, Comai S, Costa CV, Allegri G, and Petraglia F (2003) Serum tryptophan and 5-hydroxytryptophan at birth and during post-partum days. Adv Exp Med Biol 527, 757–760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Eguchi K, Kamimura S, Yonezawa M, Mitsui Y, Mizutani Y, and Kudo T (1992) [Tryptophan and its metabolite concentrations in human plasma during the perinatal period]. Nihon Sanka Fujinka Gakkai Zasshi 44, 663–668 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kazda H, Taylor N, Healy D, and Walker D (1998) Maternal, umbilical, and amniotic fluid concentrations of tryptophan and kynurenine after labor or cesarean section. Pediatr Res 44, 368–373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nakamura Y, Tamura H, Kashida S, Takayama H, Yamagata Y, Karube A, Sugino N, and Kato H (2001) Changes of serum melatonin level and its relationship to feto-placental unit during pregnancy. J Pineal Res 30, 29–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Agus A, Planchais J, and Sokol H (2018) Gut Microbiota Regulation of Tryptophan Metabolism in Health and Disease. Cell Host Microbe 23, 716–724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li Y, Zhou C, Lei W, Wang K, and Zheng J (2020) Roles of Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor in Endothelial Angiogenic Responses†. Biol Reprod [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wong CB, Tanaka A, Kuhara T, and Xiao JZ (2020) Potential Effects of Indole-3-Lactic Acid, a Metabolite of Human Bifidobacteria, on NGF-induced Neurite Outgrowth in PC12 Cells. Microorganisms 8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Suzuki Y, Kosaka M, Shindo K, Kawasumi T, Kimoto-Nira H, and Suzuki C (2013) Identification of antioxidants produced by Lactobacillus plantarum. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 77, 1299–1302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhou C, Zou QY, Jiang YZ, and Zheng J (2020) Role of oxygen in fetoplacental endothelial responses: hypoxia, physiological normoxia, or hyperoxia? Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 318, C943–c953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nguyen LP, and Bradfield CA (2008) The search for endogenous activators of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Chem Res Toxicol 21, 102–116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mor A, Kalaska B, and Pawlak D (2020) Kynurenine pathway in chronic kidney disease: what’s old, what’s new, and what’s next? International Journal of Tryptophan Research 13, 1178646920954882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Korstanje R, Deutsch K, Bolanos-Palmieri P, Hanke N, Schroder P, Staggs L, Bräsen JH, Roberts IS, Sheehan S, Savage H, Haller H, and Schiffer M (2016) Loss of Kynurenine 3-Mono-oxygenase Causes Proteinuria. J Am Soc Nephrol 27, 3271–3277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.