Abstract

High-level ab initio quantum chemical (QC) molecular potential energy surfaces (PESs) are crucial for accurately simulating molecular rotation-vibration spectra. Machine learning (ML) can help alleviate the cost of constructing such PESs, but requires access to the original ab initio PES data, namely potential energies computed on high-density grids of nuclear geometries. In this work, we present a new structured PES database called VIB5, which contains high-quality ab initio data on 5 small polyatomic molecules of astrophysical significance (CH3Cl, CH4, SiH4, CH3F, and NaOH). The VIB5 database is based on previously used PESs, which, however, are either publicly unavailable or lacking key information to make them suitable for ML applications. The VIB5 database provides tens of thousands of grid points for each molecule with theoretical best estimates of potential energies along with their constituent energy correction terms and a data-extraction script. In addition, new complementary QC calculations of energies and energy gradients have been performed to provide a consistent database, which, e.g., can be used for gradient-based ML methods.

Subject terms: Theoretical chemistry, Physical chemistry

| Measurement(s) | potential energy surfaces |

| Technology Type(s) | quantum chemistry computational methods |

Background & Summary

Many physical and chemical processes of molecular systems are governed by potential energy surfaces (PESs) that are functions of potential energy with respect to the molecular geometry defined by the nuclei1. Accurate ab initio quantum chemical (QC) molecular PESs are essential to predict and understand a multitude of physicochemical properties of interest such as reaction thermodynamics, kinetics2, and simulation of rovibrational spectra3–5. As for the latter, PESs of a number of different molecules have been constructed and used in variational nuclear motion calculations to provide accurate rotation-vibration-electronic line lists to aid the characterization of exoplanet atmospheres, amongst other applications6–16.

It is necessary to have a global PES covering all relevant regions of nuclear configurations allowing to simulate rotation-vibration (rovibrational) spectra approaching the coveted spectroscopic accuracy of 1 cm−1 in a broad range of temperatures. This can be achieved by defining the PES on a high-density grid of nuclear geometries with no holes and having the theoretical best estimate (TBE) of energies computed at a very high QC level of theory. The construction of an optimal grid usually involves many steps and human intervention, and often requires a staggeringly large number of grid points, e.g., ca. 100 thousand points even for a five-atom molecule such as methane10. The choice of QC level for TBE calculations is determined by the trade-off between accuracy and computational cost, but typically requires going well beyond the gold-standard17–19 CCSD(T)17/CBS (coupled cluster with single and double excitations and a perturbative treatment of triple excitations/complete basis set) limit and needs many QC corrections on top of it. Just to give a perspective, ca. 24 single processing unit (CPU)-hours are required for calculating TBE energy of each grid point of ~45 thousand methyl chloride (CH3Cl) geometries amounting to over 100 CPU-years when constructing its highly accurate ab initio PES20.

To reduce the high computational cost, machine learning (ML) has emerged as a powerful approach for constructing full-dimensional PESs21–27 and the resulting ML PESs can be used22,24,28–35 for performing vibrational calculations. In particular, substantial cost reduction can be achieved by calculating TBE energies only for a small number of existing grid points and then interpolating between them with ML36; such ML grids can be subsequently used for simulating rovibrational spectra with a relatively small loss of accuracy. Importantly, much larger savings in computational cost can be achieved20, when ML is applied to learn various QC corrections using a hierarchical ML (hML) scheme based on Δ-learning37 rather than to learn the TBE energy directly.

Despite all the above efforts in constructing highly accurate PESs, there is still room for improvement, e.g., via creating denser grids, using higher QC levels, and further development of ML approaches, all of which requires access to data. Unfortunately, the raw data containing geometries, TBEs and TBE constituent terms for many published studies is either missing or scattered. Thus, our data descriptor aims to organize these scattered data generated in the previous studies by some of us into a consolidated, structured PES database that we call VIB5. The VIB5 database contains five molecules CH3Cl7,9,20, CH410, SiH48, CH3F12, and NaOH14. The number of grid points ranges from 15 thousand to 100 thousand; altogether more than 300 thousand points (Table 1). In addition, it is also known that inclusion of the energy gradient information can significantly reduce the number of training points for ML, which is efficiently exploited in the gradient-based ML models38,39. Thus, for this database, we additionally calculate energies and energy gradients at two levels of theory, MP2/cc-pVTZ (second order Møller-Plesset perturbation theory/correlation-consistent triple-zeta basis set) and CCSD(T)/cc-pVQZ (correlation consistent quadruple-zeta basis set), and provide the HF (Hartree–Fock) energies calculated with the corresponding basis sets cc-pVTZ and cc-pVQZ.

Table 1.

The number of grid points (grid size) for each molecule with references to original studies generating these grid points, theoretical best estimates (TBE), and TBE constituent terms.

| Molecule | Grid size | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| CH3Cl | 44819 | 7,9,20 |

| CH4 | 97217a | 10 |

| SiH4 | 84002 | 8 |

| CH3F | 82653 | 12 |

| NaOH | 15901 | 14 |

| Total: 5 molecules | 324592a |

aThe number of grid points is slightly smaller than that reported in the original publications as we found very few duplicates in the original data set. See section Technical Validation.

Our database is complementary to existing databases used for developing ML PES models. Some existing databases contain only energies for equilibrium geometries of various compounds calculated at different levels (from density functional theory [DFT] up to coupled-cluster approaches): QM740, QM7b41, QM942, revised QM943, and ANI-1ccx44. Another database (ANI-145) also contains energies at DFT for off-equilibrium geometries. Energies and energy gradients at DFT are available for equilibrium and off-equilibrium geometries of different molecules in the ANI-1x44 and QM7-X46 databases. The MD-17 dataset38,39 is a popular database with energies and energy gradients for geometries taken from MD trajectories of several small- to medium-sized molecules at DFT and for subset of points at CCSD(T) with different basis sets. PESs generated from MD are, however, likely to have limited coverage of high-energy geometries and many holes, making them inapplicable to some kinds of accurate simulations such as diffusion Monte Carlo calculations as was pointed out recently47. In contrast to these databases, our database provides reliable, global PESs with QC energies and energy gradients at different levels including very accurate TBEs of energies going beyond CCSD(T)/CBS, which can be used for ML models trained on data from several levels of theory, such as hML, Δ-learning, etc. Finally, our database comes with a convenient data-extraction script that can be used to pull the required information in a suitable format for, e.g., ML.

Methods

Grid points generation

For each molecule, we take grid points directly from the previous studies by some of the authors. Here we only describe in short how these grid points were generated for the sake of completeness. We refer the reader to the original publications cited for each molecule for further details (see Table 1).

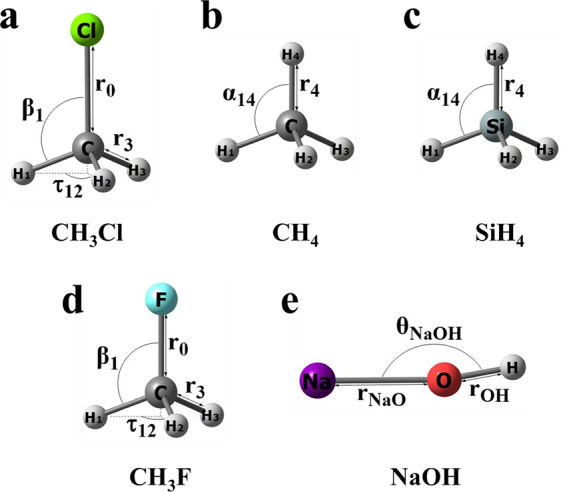

CH3Cl

44819 grid points for CH3Cl were taken from Refs. 7,9,20. A Monte Carlo random energy-weighted sampling algorithm was applied to nine internal coordinates of CH3Cl: the C–Cl bond length r0; three C–H bond lengths r1, r2, and r3; three ∠(HiCCl) interbond angles β1, β2, and β3; and two dihedral angles τ12 and τ13 between adjacent planes containing HiCCl and HjCCl (Fig. 1a). This procedure led to geometries in the range 1.3 ≤ r0 ≤ 2.95 Å, 0.7 ≤ ri ≤ 2.45 Å, 65 ≤ βi ≤ 165° for i = 1, 2, 3 and 55 ≤ τjk ≤ 185° with jk = 12, 13. The grid also includes 1000 carefully chosen low-energy points to ensure an adequate description of the equilibrium region.

Fig. 1.

Definition of internal coordinates in each molecule. Internal coordinates of (a) CH3Cl; r0 is C–Cl bond length, ri and βi are C–Hi bond lengths and ∠(HiCCl) angles (I = 1, 2, 3), τjk are HjCClHk dihedral angles (jk = 12, 13); only r0, r3, β1 and τ12 are shown; (b) CH4; ri and αjk are C–Hi bond lengths and ∠(HjCHk) angles (i = 1, 2, 3, 4; jk = 12, 13, 14, 23, 24); only r4 and α14 are shown; (c) SiH4; ri and αjk are Si–Hi bond lengths and ∠(HjSiHk) angles (i = 1, 2, 3, 4; jk = 12, 13, 14, 23, 24); only r4 and α14 are shown; (d) CH3F; r0 is C–F bond length, ri and βi are C–Hi bond lengths and ∠(HiCF) angles (i = 1, 2, 3), τjk are HjCFHk dihedral angles (jk = 12, 13); only r0, r3, β1 and τ12 are shown; (e) NaOH; rNaO and rOH are Na–O and O–H bond lengths, θNaOH is ∠(NaOH) bond angle.

CH4

97271 grid points for CH4 were taken from ref. 10. The global grid was built in the same fashion as the grid was constructed for CH3Cl. Nine internal coordinates of CH4 are defined as follows: four C–H bond lengths r1, r2, r3 and r4; five∠(Hj-C-Hk) interbond angles α12, α13, α14, α23, and α24, where j and k label the respective hydrogen atoms (Fig. 1b). Then grid points are in the range 0.71 ≤ ri ≤ 2.60 Å for i = 1, 2, 3, 4 and 40 ≤ αjk ≤ 140° with jk = 12, 13, 14, 23, 24.

SiH4

84002 grid points for SiH4 were taken from ref. 8. Nine internal coordinates of SiH4 are defined in the same way as CH4: four Si–H bond lengths r1, r2, r3 and r4; five∠(Hj-Si-Hk) interbond angles α12, α13, α14, α23, and α24, where j and k label the respective hydrogen atoms (Fig. 1c). Then geometries are in the range 0.98 ≤ ri ≤ 2.95 Å for i = 1, 2, 3, 4 and 40 ≤ αjk ≤ 140° with jk = 12, 13, 14, 23, 24.

CH3F

82653 grid points for CH3F were taken from ref. 12. Nine internal coordinates of CH3F are defined in the same way as CH3Cl: the C–F bond length r0; three C–H bond lengths r1, r2, and r3; three ∠(HiCF) interbond angles β1, β2, and β3; and two dihedral angles τ12 and τ13 between adjacent planes containing HiCF and HjCF (Fig. 1d). This procedure led to geometries in the range 1.005 ≤ r0 ≤ 2.555 Å, 0.705 ≤ ri ≤ 2.695 Å, 45.5 ≤ βi ≤ 169.5° for i = 1, 2, 3 and 40.5 ≤ τjk ≤ 189.5° with jk = 12, 13.

NaOH

15901 grid points for NaOH were taken from ref. 14. Grid points were generated randomly with a dense distribution around the equilibrium region. Three internal coordinates of NaOH are defined as follows: the Na–O bond length rNaO, the O–H bond length rOH, and the interbond angle ∠(NaOH) (Fig. 1e). This procedure led to geometries in the range 1.435 ≤ rNaO ≤ 4.400 Å, 0.690 ≤ rOH ≤ 1.680 Å, and 40 ≤ ∠(NaOH) ≤ 180°.

Theoretical best estimates and constituent terms

For each molecule, we take the TBEs and energy corrections directly from the previous studies by some of us. Here we only briefly introduce how these calculations were performed. We refer the reader to the original publications cited for each molecule for details (see Table 1). TBE is obtained through the sum of many constituent terms: ECBS, ∆ECV, ∆EHO, ∆ESR, and, for most molecules, ∆EDBOC. ECBS means the energy at the complete basis set (CBS) limit. ∆ECV refers to the core-valence (CV) electron correlation energy correction. ∆EHO refers to the energy correction accounted for by the higher-order (HO) coupled cluster terms and ∆ESR shows scalar relativistic (SR) effects. ∆EDBOC means the diagonal Born–Oppenheimer correction and was calculated for CH3Cl, CH4, CH3F, and NaOH, but not for SiH4 due to the little effect of ∆EDBOC on the vibrational energy levels of this molecule.

The constituent terms were not calculated at the same level of theory across all molecules in the data set. The computational details of five TBE constituent terms (ECBS, ∆ECV, ∆EHO, ∆ESR, and ∆EDBOC) for 5 molecules are shown below and summarized in the Table 2.

Table 2.

The comparative table of the computational details behind the calculations of the constituent terms of theoretical best estimates for five molecules of the VIB5 database.

| Molecule | ECBS | ∆ECV | ∆EHO | ∆ESR | ∆EDBOC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CH3Cl | Software: MOLPRO2012 | The basis set: cc-pCVQZ-F12; Slater geminal exponent value β = 1.5 a0−1; all-electron calculations kept the 1s orbital of Cl frozen; Software: MOLPRO2012 | Levels of theory: CCSD(T), CCSDT, and CCSDT(Q); Basis sets for the full triples and the perturbative quadruples calculations are aug-cc-pVTZ(+d for Cl) and aug-cc-pVDZ(+d for Cl), respectively. | Method: one-electron mass velocity and Darwin (MVD1) terms from the Breit–Pauli Hamiltonian in first-order perturbation theory; All electrons correlated (except for the 1s of Cl); CCSD(T)/aug-cc-pCVTZ(+d for Cl). Software: CFOUR | The 1s orbital of Cl is frozen and all other electrons are correlated; basis set: aug-cc-pCVTZ (+d for Cl) |

| CH4 | Software: MOLPRO2012 | The basis set: cc-pCVTZ-F12; Slater geminal exponent value β = 1.4 a0−1; No frozen orbital; Software: MOLPRO2012 | Levels of theory: CCSD(T), CCSDT, and CCSDT(Q); Basis sets for the full triples and the perturbative quadruples calculations are cc-pVTZ and cc-pVDZ, respectively. | Method: the second-order Douglas–Kroll–Hess approach; frozen core approximation; CCSD(T)/cc-pVQZ-DK. Software: MOLPRO2012 | All electrons are correlated; basis set: aug-cc-pCVDZ |

| SiH4 | Software: MOLPRO2012 | The basis set: cc-pCVTZ-F12; Slater geminal exponent value β = 1.4 a0−1; all-electron calculations kept the 1s orbital of Si frozen; Software: MOLPRO2012 | Levels of theory: CCSD(T), CCSDT, and CCSDT(Q); basis sets for the full triples and the perturbative quadruples calculations are cc-pVTZ(+d for Si) and cc-pVDZ(+d for Si), respectively. | Method: the second-order Douglas-Kroll-Hess approach; frozen core approximation; CCSD(T)/cc-pVQZ-DK. Software: MOLPRO2012 | The correction was not included. |

| CH3F | Software: MOLPRO2012 | The basis set: cc-pCVTZ-F12; Slater geminal exponent value β = 1.4 a0−1; no frozen orbital; Software: MOLPRO2012 | Levels of theory: CCSD(T), CCSDT, and CCSDT(Q); basis sets for the full triples and the perturbative quadruples calculations are cc-pVTZ and cc-pVDZ, respectively. | Method: the second-order Douglas–Kroll–Hess approach; frozen core approximation; CCSD(T)/ cc-pVQZ-DK. Software: MOLPRO2012 | All electrons are correlated; basis set: aug-cc-pCVDZ |

| NaOH | Software: MOLPRO2015 | The basis set: cc-pCVTZ-F12; Slater geminal exponent value β = 1.4 a0−1; all-electron calculations kept the 1s orbital of sodium frozen; Software: MOLPRO2015 | Levels of theory: CCSD(T) and CCSDT; basis set: cc-pVTZ(+d for Na). | Method: the second-order Douglas–Kroll–Hess approach; frozen core approximation; CCSD(T)/cc-pVQZ-DK. Software: MOLPRO2015 | The 1s orbital of Na is frozen and all other electrons are correlated; basis set: aug-cc-pCVDZ(+d for Na) |

This table mainly emphasizes differences for each molecule, rather than giving the full description of computational details.

ECBS

To extrapolate the energy to the CBS limit, the parameterized, two-point formula48 was used. In this process, the method CCSD(T)-F12b49 and two basis sets cc-pVTZ-F12 and cc-pVQZ-F1250 were chosen. When performing calculations, the frozen core approximation was adopted and the diagonal fixed amplitude ansatz 3C(FIX)51 with a Slater geminal exponent value48 of β = 1.0 a0−1 were employed. As for the auxiliary basis sets (ABS), the resolution of the identity OptRI52 basis and cc-pV5Z/JKFIT53 and aug-cc-pwCV5Z/MP2FIT54 basis sets for density fitting were used for all 5 molecules. These calculations were carried out with either MOLPRO201255 (CH3Cl, CH4, SiH4, CH3F) or MOLPRO201555,56 (NaOH). As for the coefficients in this two-point formula, FCCSD-F12b = 1.363388 and F(T) = 1.76947448 were used for all molecules. The extrapolation was not applied to the Hartree–Fock (HF) energy and the HF + CABS (complementary auxiliary basis set) singles correction49 calculated with the cc-pVQZ-F12 basis set was used.

∆ECV

∆ECV was computed at CCSD(T)-F12b/cc-pCVQZ-F1257 for CH3Cl and at CCSD(T)-F12b/cc-pCVTZ-F1257 for the other 4 molecules (CH4, SiH4, CH3F, NaOH). The same ansatz and ABS used for ECBS were employed for calculating ∆ECV but the Slater geminal exponent value was changed: β = 1.5 a0−1 for CH3Cl and β = 1.4 a0−1 for the other 4 molecules. For this term, all-electron calculations were adopted, but with the 1s orbital of Cl frozen for CH3Cl, the 1s orbital of Si frozen for SiH4, and the 1s orbital of Na frozen for NaOH. There is no frozen orbital in all-electron calculations for CH4 and CH3F. As for the software used, see the above ECBS part.

∆EHO

To obtain ∆EHO, the hierarchy of coupled cluster methods was used. ∆EHO = ECCSDT − ECCSD(T) for NaOH, while ∆EHO = ∆ET + ∆E(Q) for other 4 molecules (CH3Cl, CH4, SiH4, CH3F) with ∆ET = ECCSDT − ECCSD(T) for full triples contribution and ∆E(Q) = ECCSDT(Q) − ECCSDT for perturbative quadruples contribution. The frozen core approximation was employed in the calculations. Thus, energy calculations at CCSD(T) and CCSDT were performed for NaOH, while energy calculations at CCSD(T), CCSDT, and CCSDT(Q) levels of theory were performed for other 4 molecules. All of these calculations were carried out through the general coupled cluster approach58,59 implemented in the MRCC code (www.mrcc.hu)60 interfaced to CFOUR (www.cfour.de)61. As for the basis set, aug-cc-pVTZ(+d for Cl)62–65 & aug-cc-pVDZ(+d for Cl), cc-pVTZ62 & cc-pVDZ, cc-pVTZ(+d for Si)62–65 & cc-pVDZ(+d for Si), and cc-pVTZ62 & cc-pVDZ for full triples and the perturbative quadruples of CH3Cl, CH4, SiH4, and CH3F. For NaOH, cc-pVTZ(+d for Na)62,66 were used for CCSD(T) and CCSDT calculations.

∆ESR

∆ESR was calculated by using either one-electron mass velocity and Darwin (MVD1) terms from the Breit–Pauli Hamiltonian in first-order perturbation theory67 or the second-order Douglas–Kroll–Hess approach68,69. The former method was used for CH3Cl and the latter method was used for the other 4 molecules (CH4, SiH4, CH3F, and NaOH). All-electron calculations (except for the 1s orbital of Cl) was adopted for CH3Cl while the frozen core approximation was employed for the other 5 molecules. Calculations were performed at CCSD(T)/aug-cc-pCVTZ(+d for Cl)70,71 using the MVD1 approach72 implemented in CFOUR for CH3Cl and at CCSD(T)/cc-pVQZ-DK73 using MOLPRO (software versions the same as mentioned in the above ECBS part) for other 4 molecules.

∆EDBOC

∆EDBOC was computed using the CCSD method74 as implemented in CFOUR. This correction was not included for SiH4. For this term, all-electron calculations were adopted, but with the 1s orbital of Cl frozen for CH3Cl, all electrons correlated for CH4 and CH3F, and the 1s orbital of Na frozen for NaOH. As for the basis set, calculations were performed at aug-cc-pCVTZ (+d for Cl) for CH3Cl, aug-cc-pCVDZ for CH4, aug-cc-pCVDZ for CH3F, and aug-cc-pCVDZ(+d for Na) for NaOH.

Complementary energy and gradient calculations

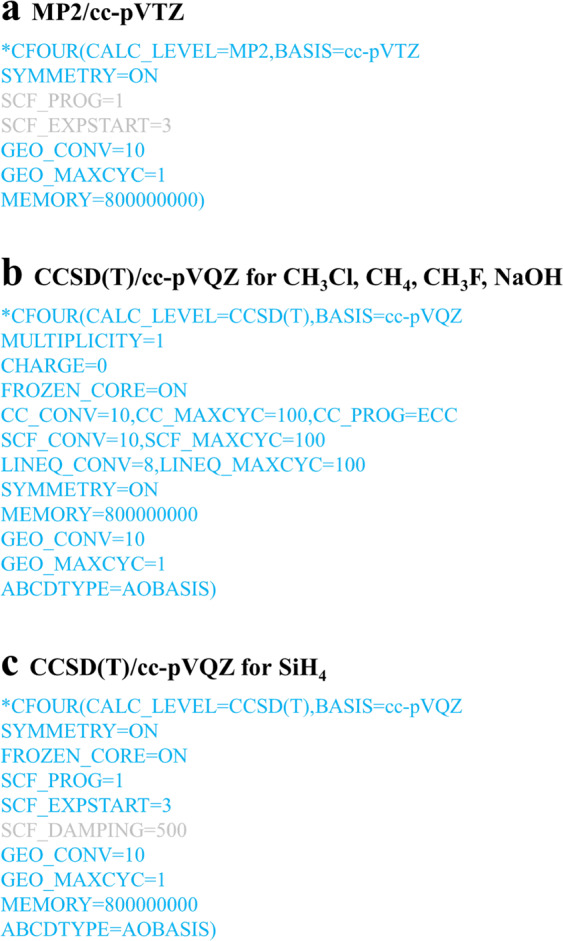

All complementary ab initio QC energy and gradient calculations for a total of 324592 grid points were performed with two levels of theory: MP275,76/cc-pVTZ62,64,66 and CCSD(T)17,77,78/cc-pVQZ62,64,66 using the CFOUR program package (Versions 1.0 and 2.161; we use CFOUR V2.1 to perform calculations for some grid points in CH3Cl and NaOH that converge to high energy solutions); see Fig. 2 for the CFOUR input options. In the MP2/cc-pVTZ calculations, we use the default option FROZEN_CORE = OFF so that all electrons and all orbitals are correlated. In the CCSD(T)/cc-pVQZ calculations, the option FROZEN_CORE = ON is used for all molecules to allow valence electrons correlation alone. For CH3Cl, CH4, CH3F and NaOH, SCF_CONV = 10, CC_CONV = 10 and LINEQ_CONV = 8 are set to specify the convergence criterion for the HF-SCF, CC amplitude and linear equations and CC_PROG = ECC is set to specify that the CC program we used is ECC. For SiH4, we adopted CFOUR default options SCF_CONV = 7, CC_CONV = 7, LINEQ_CONV = 7 and CC_PROG = VCC. We use GEO_MAXCYC = 1 option to set the maximum number of geometry optimization iterations to one to obtain the gradient information of the current nuclear configuration. From these calculations we also extracted HF energies calculated with the corresponding basis sets cc-pVTZ and cc-pVQZ. In addition, for CH3Cl we include MP2/aug-cc-pVQZ energies calculated using MOLPRO201255 as reported in ref. 20.

Fig. 2.

Typical CFOUR input options for (a) MP2/cc-pVTZ, (b) CCSD(T)/cc-pVQZ for CH3Cl, CH4, CH3F, NaOH and (c) CCSD(T)/cc-pVQZ for SiH4. The blue options were used for most cases and the light grey options are examples of options used to improve SCF convergence only for some geometries.

Data Records

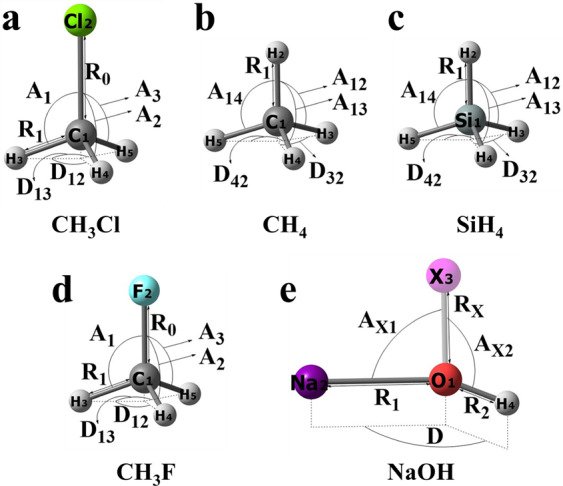

All data of 5 molecules are stored as a database in JSON format in the file named VIB5.json available for download from 10.6084/m9.figshare.1690328879. The first level of the database contains an item corresponding to each molecule in the order of CH3Cl, CH4, SiH4, CH3F, and NaOH. For each molecule, at the next level of the database, chemical formula, chemical name, number of atoms, list of nuclear charges in the same order as they appear in the items with nuclear coordinates are given at first, then the description of properties available for grid points (property type, levels of theory, units) is provided. Finally, the items for each grid point are given containing nuclear positions in both Cartesian and internal coordinates, and the values of properties (energies and energy gradients at different levels of theory, i.e., TBE, TBE constituent terms, complementary data). The JSON keys of items available for each grid point are listed in Table 3 with the brief description and units. The geometry configuration in Cartesian coordinates and in internal coordinates of each grid point for each molecule can be accessed by the “XYZ” key and the “INT” key, respectively. Definition of internal coordinates used in the database is shown in Fig. 3. The “HF-TZ”, “HF-QC”, “MP2”, “CCSD-T”, and “TBE” keys can be selected separately to obtain the energy of each grid point at HF/cc-pVTZ, HF/cc-pVQZ, MP2/cc-pVTZ, CCSD(T)/cc-pVQZ, and TBE, respectively. This database also provides the energy gradients in Cartesian coordinates and internal coordinates at MP2/cc-pVTZ and CCSD(T)/cc-pVQZ theory levels, which can be accessed through “MP2_grad_xyz”, “MP2_grad_int”, “CCSD-T_grad_xyz”, and “CCSD-T_grad_int” keys. See Table 3 for the summary and the keys of other properties.

Table 3.

Layout of the VIB5.json file containing the VIB5 database.

| No. | Key | Description | Units |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | XYZ | Nuclear positions in Cartesian coordinates | Å |

| 2 | INT | Nuclear positions in internal coordinates | Å; degree |

| 3 | HF-TZ | Total energy at HF/cc-pVTZ | Hartree |

| 4 | HF-QZ | Total energy at HF/cc-pVQZ | Hartree |

| 5 | MP2 | Total energy at MP2/cc-pVTZ | Hartree |

| 6 | CCSD-T | Total energy at CCSD(T)/cc-pVQZ | Hartree |

| 7 | TBE | Theoretical best estimate of ab initio deformation energies | cm−1 |

| 8 | MP2_grad_xyz | Energy gradient in Cartesian coordinates at MP2/cc-pVTZ | Hartree/Å |

| 9 | MP2_grad_int | Energy gradient in internal coordinates at MP2/cc-pVTZ | Hartree/Å; Hartree/degree |

| 10 | CCSD-T_grad_xyz | Energy gradient in Cartesian coordinates at CCSD(T)/cc-pVQZ | Hartree/Å |

| 11 | CCSD-T_grad_int | Energy gradient in internal coordinates at CCSD(T)/cc-pVQZ | Hartree/Å; Hartree/degree |

| 12 | CBS | Deformation energies at CCSD(T)-F12b/CBS | cm−1 |

| 13 | VTZ | Deformation energies at CCSD(T)-F12b/cc-pVTZ-F12 (only for CH3Cl molecule) | cm−1 |

| 14 | VQZ | Deformation energies at CCSD(T)-F12b/cc-pVQZ-F12 (only for CH3Cl molecule) | cm−1 |

| 15 | CV | Deformation energy corrections to account for core-valence electron correlation | cm−1 |

| 16 | HO | Deformation higher-order coupled cluster terms beyond perturbative triples | cm−1 |

| 17 | SR | Deformation scalar relativistic (SR) effects | cm−1 |

| 18 | DBOC | Deformation diagonal Born–Oppenheimer corrections (only for CH3Cl, CH4, CH3F, and NaOH molecules) | cm−1 |

| 19 | MP2-aQZ | Deformation energies at MP2/aug-cc-pVQZ (only for CH3Cl molecule) | cm−1 |

Fig. 3.

Definition of internal coordinates for each molecule used in the database file VIB5.json and in the complimentary calculations. Internal coordinates of (a) CH3Cl; R0 is C–Cl bond length, Ri and Ai are C–Hi+2 bond lengths and ∠(Hi+2CCl) angles (i = 1, 2, 3), Djk are Hj+2CClHk+2 dihedral angles (jk = 12, 13); only R0, R1, A1, A2, A3, D12, and D13 are shown; (b) CH4; Ri and A1j are C–Hi+1 bond lengths and ∠(H2CHj+1) angles (i = 1, 2, 3, 4; j = 2, 3, 4), Dk2 are Hk+1CH2H3 dihedral angles (k = 3, 4); only R1, A12, A13, A14, D32, and D42 are shown; (c) SiH4; Ri and A1j are Si–Hi+1 bond lengths and ∠(H2SiHj+1) angles (i = 1, 2, 3, 4; j = 2, 3, 4), Dk2 are Hk+1SiH2H3 dihedral angles (k = 3, 4); only R1, A12, A13, A14, D32, and D42 are shown; (d) CH3F; R0 is C–F bond length, Ri and Ai are C–Hi+2 bond lengths and ∠(Hi+2CF) angles (i = 1, 2, 3), Djk are Hj+2CFHk+2 dihedral angles (jk = 12, 13); only R0, R1, A1, A2, A3, D12, and D13 are shown; (e) NaOH; R1 and R2 are Na–O and H–O bond lengths, RX is O–X bond length, AX1 and AX2 are ∠(XONa) and ∠(XOH) angles, and D is NaXOH dihedral angle. X is a dummy atom.

Technical Validation

The TBE values and TBE constituent terms were validated by calculating rovibrational spectra and comparing them to experiment in the original peer-reviewed publications cited in the Methods section and Table 1. In brief, rovibrational energy levels were computed by fitting analytical expression for PES and performing with it variational calculations using the nuclear motion program TROVE80. Then the resulting line list of rovibrational energy levels was compared to experimental values (when available) to validate the accuracy of the underlying PES. The new complementary data we have calculated here was validated by making sure that all calculations fully converged. After the database was constructed, we performed additional checks for repeated geometries, which identified grid points with the same geometrical parameters in the CH4 grid points. We removed such duplicates from the database, which leads to a slightly reduced number of points (97217) compared to the numbers reported in the original publications (97271). This pruned grid is used as our final database.

Usage Notes

We provide a Python script extraction_data.py that can be used to pull the data of interest from the VIB5.json (Box 1). It is provided together with the database file from 10.6084/m9.figshare.1690328879.

Box 1.

Using extraction_data.py script to extract required data: an example of extracting CCSD(T)/CBS and CCSD(T)/cc-pVQZ energies and Cartesian geometries for NaOH. The *.dat files contain energies and *.xyz files contain XYZ geometries in the same order as in the database. The user can run python3 extraction_data.py -h command to see more options.

example$ ls

VIB5.json extraction_data.py

example$ python3 ./extraction_data.py --mols NaOH --energy CBS,CCSD-T -xyz

example$ ls

NaOH_CBS.dat NaOH_CCSD-T.dat NaOH.xyz VIB5.json extraction_data.py

example$ head -n 10 *.dat

==> NaOH_CBS.dat <==

59.280650000000

59.574700000000

59.558345000000

47.465761000000

64.042693000000

59.852814000000

60.391809000000

61.782135000000

33.479406000000

83.271969000000

==> NaOH_CCSD-T.dat <==

-237.644636975222

-237.644635947086

-237.644635792937

-237.644692089151

-237.644614779690

-237.644634762797

-237.644632245341

-237.644626330200

-237.644757449209

-237.644525233060

example$ head -n 10 *.xyz

3

O 0.00000000 0.00000000 1.08916506

Na 0.00000000 0.00000000 -0.84719335

H 0.00000000 0.00000000 2.03971526

3

O 0.00000000 0.00000000 1.08917892

Na 0.00000000 0.00000000 -0.84717949

H 0.00000000 0.00000000 2.03917912

Acknowledgements

POD acknowledges funding by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 22003051), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (No. 20720210092), and via the Lab project of the State Key Laboratory of Physical Chemistry of Solid Surfaces. SNY and AO thank STFC under grant ST/R000476/1. Their calculations made extensive use of the STFC DiRAC HPC facility supported by BIS National E-infrastructure capital grant ST/J005673/1 and STFC grants ST/H008586/1 and ST/K00333X/1.

Author contributions

L.Z. has written the original draft of the manuscript. S.Z. performed the complementary calculations, validation, created scripts and database files with assistance of L.Z. and P.O.D. A.O. provided raw data with grids, theoretical best estimates and energy correction terms as well as supporting scripts. A.O., S.N.Y. and P.O.D. supervised the project. S.N.Y. and P.O.D. acquired funding for the project. All authors provided critical feedback and helped shape the database collection, calculations, analysis, and manuscript. P.O.D. conceived the idea of creating a database.

Code availability

All the data generated at the MP2/cc-pVTZ and the CCSD(T)/cc-pVQZ levels of theory were performed with the CFOUR software package. TBE and other data were obtained using various software packages (MOLPRO, CFOUR, MRCC) as described in the Methods section.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Alec Owens, Email: alec.owens.13@ucl.ac.uk.

Pavlo O. Dral, Email: dral@xmu.edu.cn

References

- 1.Lewars, E. Computational Chemistry: Introduction to the Theory and Applications of Molecular and Quantum Mechanics 2nd edn (Springer Science+Business Media B.V., 2011).

- 2.Upadhyay, S. K. Chemical Kinetics and Reaction Dynamics (Anamaya Publishers, 2006).

- 3.Searles, D. J. & von Nagy-Felsobuki, E. I. In Ab Initio Variational Calculations of Molecular Vibrational-Rotational Spectra (Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg, 1993).

- 4.Császár, A. G., Czakó, G., Furtenbacher, T. & Mátyus, E. In Annual Reports in Computational Chemistry3 (Elsevier, 2007).

- 5.Bytautas L, Bowman JM, Huang X, Varandas AJC. Accurate potential energy surfaces and beyond: chemical reactivity, binding, long-range interactions, and spectroscopy. Adv. Phys. Chem. 2012;2012:679869. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tennyson J, Yurchenko SN. ExoMol: molecular line lists for exoplanet and other atmospheres. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2012;425:21–33. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Owens, A., Yurchenko, S. N., Yachmenev, A., Tennyson, J. & Thiel, W. Accurate ab initio vibrational energies of methyl chloride. J. Chem. Phys. 142 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Owens, A., Yurchenko, S. N., Yachmenev, A. & Thiel, W. A global potential energy surface and dipole moment surface for silane. J. Chem. Phys. 143 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Owens A, Yurchenko SN, Yachmenev A, Tennyson J, Thiel W. A global ab initio dipole moment surface for methyl chloride. J. Quant. Spectrosc. Radiat. Transfer. 2016;184:100–110. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Owens, A., Yurchenko, S. N., Yachmenev, A., Tennyson, J. & Thiel, W. A highly accurate ab initio potential energy surface for methane. J. Chem. Phys. 145 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Owens, A. & Yurchenko, S. N. Theoretical rotation-vibration spectroscopy of cis- and trans-diphosphene (P2H2) and the deuterated species P2HD. J. Chem. Phys. 150 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Owens A, Yachmenev A, Kupper J, Yurchenko SN, Thiel W. The rotation-vibration spectrum of methyl fluoride from first principles. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2019;21:3496–3505. doi: 10.1039/c8cp01721b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Owens A, Conway EK, Tennyson J, Yurchenko SN. ExoMol line lists – XXXVIII. High-temperature molecular line list of silicon dioxide (SiO2) Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2020;495:1927–1933. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Owens A, Tennyson J, Yurchenko SN. ExoMol line lists – XLI. High-temperature molecular line lists for the alkali metal hydroxides KOH and NaOH. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2021;502:1128–1135. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tennyson J, et al. ExoMol molecular line lists XXX: a complete high-accuracy line list for water. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2018;480:2597–2608. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yurchenko SN, Tennyson J. ExoMol line lists - IV. The rotation-vibration spectrum of methane up to 1500 K. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2014;440:1649–1661. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Raghavachari K, Trucks GW, Pople JA, Head-Gordon M. A fifth-order perturbation comparison of electron correlation theories. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1989;157:479–483. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Helgaker T, Gauss J, Jørgensen P, Olsen J. The prediction of molecular equilibrium structures by the standard electronic wave functions. J. Chem. Phys. 1997;106:6430–6440. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bak KL, et al. The accurate determination of molecular equilibrium structures. J. Chem. Phys. 2001;114:6548–6556. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dral PO, Owens A, Dral A, Csányi G. Hierarchical machine learning of potential energy surfaces. J. Chem. Phys. 2020;152:204110. doi: 10.1063/5.0006498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Behler J. Neural network potential-energy surfaces in chemistry: a tool for large-scale simulations. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2011;13:17930–17955. doi: 10.1039/c1cp21668f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Manzhos S, Dawes R, Carrington T., Jr. Neural network-based approaches for building high dimensional and quantum dynamics-friendly potential energy surfaces. Int. J. Quantum Chem. 2015;115:1012–1020. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Unke OT, et al. Machine learning force fields. Chem. Rev. 2021;121:10142–10186. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.0c01111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Manzhos S, Carrington T., Jr. Neural network potential energy surfaces for small molecules and reactions. Chem. Rev. 2020;121:10187–10217. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.0c00665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mueller T, Hernandez A, Wang C. Machine learning for interatomic potential models. J. Chem. Phys. 2020;152:050902. doi: 10.1063/1.5126336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dral, P. O. In Advances in Quantum Chemistry: Chemical Physics and Quantum Chemistry81 (Academic Press, 2020).

- 27.Dral PO. Quantum chemistry in the age of machine learning. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2020;11:2336–2347. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpclett.9b03664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schmitz G, Artiukhin DG, Christiansen O. Approximate high mode coupling potentials using Gaussian process regression and adaptive density guided sampling. J. Chem. Phys. 2019;150:131102. doi: 10.1063/1.5092228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gastegger M, Behler J, Marquetand P. Machine learning molecular dynamics for the simulation of infrared spectra. Chem. Sci. 2017;8:6924–6935. doi: 10.1039/c7sc02267k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kamath A, Vargas-Hernández RA, Krems RV, Carrington T, Jr., Manzhos S. Neural networks vs Gaussian process regression for representing potential energy surfaces: A comparative study of fit quality and vibrational spectrum accuracy. J. Chem. Phys. 2018;148:241702. doi: 10.1063/1.5003074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Manzhos S. Machine learning for the solution of the Schrödinger equation. Mach. Learn.: Sci. Technol. 2020;1:013002. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Manzhos S, Yamashita K, Carrington T., Jr. Using a neural network based method to solve the vibrational Schrodinger equation for H2O. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2009;474:217–221. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Manzhos S, Wang XG, Dawes R, Carrington T., Jr. A nested molecule-independent neural network approach for high-quality potential fits. J Phys Chem A. 2006;110:5295–5304. doi: 10.1021/jp055253z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Manzhos S, Carrington T., Jr. A random-sampling high dimensional model representation neural network for building potential energy surfaces. J. Chem. Phys. 2006;125:084109. doi: 10.1063/1.2336223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Manzhos S, Carrington T., Jr. Using neural networks, optimized coordinates, and high-dimensional model representations to obtain a vinyl bromide potential surface. J. Chem. Phys. 2008;129:224104. doi: 10.1063/1.3021471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dral PO, Owens A, Yurchenko SN, Thiel W. Structure-based sampling and self-correcting machine learning for accurate calculations of potential energy surfaces and vibrational levels. J. Chem. Phys. 2017;146:244108. doi: 10.1063/1.4989536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ramakrishnan R, Dral PO, Rupp M, von Lilienfeld OA. Big data meets quantum chemistry approximations: the Δ-machine learning approach. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2015;11:2087–2096. doi: 10.1021/acs.jctc.5b00099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chmiela S, et al. Machine learning of accurate energy-conserving molecular force fields. Sci. Adv. 2017;3:e1603015. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1603015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chmiela S, Sauceda HE, Müller K-R, Tkatchenko A. Towards exact molecular dynamics simulations with machine-learned force fields. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:3887. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-06169-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rupp M, Tkatchenko A, Müller K-R, von Lilienfeld OA. Fast and accurate modeling of molecular atomization energies with machine learning. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2012;108:058301. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.108.058301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Montavon G, et al. Machine learning of molecular electronic properties in chemical compound space. New J. Phys. 2013;15:095003. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ramakrishnan R, Dral PO, Rupp M, von Lilienfeld OA. Quantum chemistry structures and properties of 134 kilo molecules. Sci. Data. 2014;1:140022. doi: 10.1038/sdata.2014.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kim H, Park JY, Choi S. Energy refinement and analysis of structures in the QM9 database via a highly accurate quantum chemical method. Sci. Data. 2019;6:109. doi: 10.1038/s41597-019-0121-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Smith JS, et al. The ANI-1ccx and ANI-1x data sets, coupled-cluster and density functional theory properties for molecules. Sci. Data. 2020;7:134. doi: 10.1038/s41597-020-0473-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Smith JS, Isayev O, Roitberg AE. ANI-1, a data set of 20 million calculated off-equilibrium conformations for organic molecules. Sci. Data. 2017;4:170193. doi: 10.1038/sdata.2017.193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hoja J, et al. QM7-X, a comprehensive dataset of quantum-mechanical properties spanning the chemical space of small organic molecules. Sci. Data. 2021;8:43. doi: 10.1038/s41597-021-00812-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Qu C, Houston PL, Conte R, Nandi A, Bowman JM. MULTIMODE calculations of vibrational spectroscopy and 1d interconformer tunneling dynamics in Glycine using a full-dimensional potential energy surface. J Phys Chem A. 2021;125:5346–5354. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpca.1c03738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hill JG, Peterson KA, Knizia G, Werner H-J. Extrapolating MP2 and CCSD explicitly correlated correlation energies to the complete basis set limit with first and second row correlation consistent basis sets. J. Chem. Phys. 2009;131:194105. doi: 10.1063/1.3265857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Adler TB, Knizia G, Werner H-J. A simple and efficient CCSD(T)-F12 approximation. J. Chem. Phys. 2007;127:221106. doi: 10.1063/1.2817618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Peterson KA, Adler TB, Werner H-J. Systematically convergent basis sets for explicitly correlated wavefunctions: the atoms H, He, B–Ne, and Al–Ar. J. Chem. Phys. 2008;128:084102. doi: 10.1063/1.2831537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ten-no S. Initiation of explicitly correlated Slater-type geminal theory. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2004;398:56–61. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yousaf KE, Peterson KA. Optimized auxiliary basis sets for explicitly correlated methods. J. Chem. Phys. 2008;129:184108. doi: 10.1063/1.3009271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Weigend F. A fully direct RI-HF algorithm: implementation, optimised auxiliary basis sets, demonstration of accuracy and efficiency. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2002;4:4285–4291. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hättig C. Optimization of auxiliary basis sets for RI-MP2 and RI-CC2 calculations: Core-valence and quintuple-ζ basis sets for H to Ar and QZVPP basis sets for Li to Kr. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2005;7:59–66. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Werner H-J, Knowles PJ, Knizia G, Manby FR, Schütz M. Molpro: a general-purpose quantum chemistry program package. WIREs Comput. Mol. Sci. 2012;2:242–253. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Werner H-J, et al. The Molpro quantum chemistry package. J. Chem. Phys. 2020;152:144107. doi: 10.1063/5.0005081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hill JG, Mazumder S, Peterson KA. Correlation consistent basis sets for molecular core-valence effects with explicitly correlated wave functions: the atoms B–Ne and Al–Ar. J. Chem. Phys. 2010;132:054108. doi: 10.1063/1.3308483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kállay M, Gauss J. Approximate treatment of higher excitations in coupled-cluster theory. J. Chem. Phys. 2005;123:214105. doi: 10.1063/1.2121589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kállay M, Gauss J. Approximate treatment of higher excitations in coupled-cluster theory. II. Extension to general single-determinant reference functions and improved approaches for the canonical Hartree–Fock case. J. Chem. Phys. 2008;129:144101. doi: 10.1063/1.2988052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.MRCC, A string-based quantum chemical program suite written by M. Kállay; see also M. Kállay & P. R. Surján, J. Chem. Phys. 115, 2945 (2001).

- 61.Stanton, J. F. et al. CFOUR, a quantum chemical program package http://www.cfour.de (2010).

- 62.Dunning TH., Jr. Gaussian basis sets for use in correlated molecular calculations. I. The atoms boron through neon and hydrogen. J. Chem. Phys. 1989;90:1007–1023. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kendall RA, Dunning TH, Jr., Harrison RJ. Electron affinities of the first‐row atoms revisited. Systematic basis sets and wave functions. J. Chem. Phys. 1992;96:6796–6806. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Woon DE, Dunning TH., Jr. Gaussian basis sets for use in correlated molecular calculations. III. The atoms aluminum through argon. J. Chem. Phys. 1993;98:1358–1371. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dunning TH, Jr., Peterson KA, Wilson AK. Gaussian basis sets for use in correlated molecular calculations. X. The atoms aluminum through argon revisited. J. Chem. Phys. 2001;114:9244–9253. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Prascher BP, Woon DE, Peterson KA, Dunning TH, Jr., Wilson AK. Gaussian basis sets for use in correlated molecular calculations. VII. Valence, core-valence, and scalar relativistic basis sets for Li, Be, Na, and Mg. Theor. Chem. Acc. 2011;128:69–82. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cowan RD, Griffin DC. Approximate relativistic corrections to atomic radial wave functions*. J. Opt. Soc. Am. 1976;66:1010–1014. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Douglas M, Kroll NM. Quantum electrodynamical corrections to the fine structure of helium. Ann. Phys. 1974;82:89–155. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hess BA. Relativistic electronic-structure calculations employing a two-component no-pair formalism with external-field projection operators. Phys. Rev. A. 1986;33:3742–3748. doi: 10.1103/physreva.33.3742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Woon DE, Dunning TH., Jr. Gaussian basis sets for use in correlated molecular calculations. V. Core-valence basis sets for boron through neon. J. Chem. Phys. 1995;103:4572–4585. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Peterson KA, Dunning TH., Jr. Accurate correlation consistent basis sets for molecular core-valence correlation effects: The second row atoms Al–Ar, and the first row atoms B–Ne revisited. J. Chem. Phys. 2002;117:10548–10560. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Klopper W. Simple recipe for implementing computation of first-order relativistic corrections to electron correlation energies in framework of direct perturbation theory. J. Comput. Chem. 1997;18:20–27. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Jong WAD, Harrison RJ, Dixon DA. Parallel Douglas–Kroll energy and gradients in NWChem: estimating scalar relativistic effects using Douglas–Kroll contracted basis sets. J. Chem. Phys. 2001;114:48–53. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gauss J, Tajti A, Kállay M, Stanton JF, Szalay PG. Analytic calculation of the diagonal Born-Oppenheimer correction within configuration-interaction and coupled-cluster theory. J. Chem. Phys. 2006;125:144111. doi: 10.1063/1.2356465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bartlett RJ. Many-body perturbation theory and coupled cluster theory for electron correlation in molecules. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 1981;32:359–401. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Cremer, D. in Encyclopedia of Computational Chemistry (John Wiley and Sons, Ltd., 1998).

- 77.Bartlett RJ, Watts JD, Kucharski SA, Noga J. Non-iterative fifth-order triple and quadruple excitation energy corrections in correlated methods. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1990;165:513–522. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Stanton JF. Why CCSD(T) works: a different perspective. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1997;281:130–134. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zhang L, Zhang S, Owens A, Yurchenko SN, Dral PO. 2021. VIB5 database with accurate ab initio quantum chemical molecular potential energy surfaces. figshare. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 80.Yurchenko SN, Thiel W, Jensen P. Theoretical ROVibrational Energies (TROVE): a robust numerical approach to the calculation of rovibrational energies for polyatomic molecules. J. Mol. Spectrosc. 2007;245:126–140. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- Zhang L, Zhang S, Owens A, Yurchenko SN, Dral PO. 2021. VIB5 database with accurate ab initio quantum chemical molecular potential energy surfaces. figshare. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Data Availability Statement

All the data generated at the MP2/cc-pVTZ and the CCSD(T)/cc-pVQZ levels of theory were performed with the CFOUR software package. TBE and other data were obtained using various software packages (MOLPRO, CFOUR, MRCC) as described in the Methods section.