Louis Braille (1809–1852)[1]

“So the darkness shall be the light, and the stillness the dancing.”

T. S. Eliot

In the town of Coupvray, Paris, on a cold night of January 4, 1809, was born a child to the village cobbler, Simone René Braille, and Monique Baron, who would grow up to bear the beacon of education to millions across the globe. Youngest of the four siblings, Louis was growing into a healthy, bright boy who loved to follow his father, even to his shop. One day, when he was merely three, curiosity drove him to pick up the tools in the harness shop and a sharp one badly injured his right eye. Soon, his left eye was inflamed (sympathetic ophthalmia), and by age five, he was blind in both eyes.[2,3]

Devastated but not dejected by his son’s misfortune, the father took it upon himself to ensure that Louis’ education continued. He learned to read alphabets with the help of upholstery nails hammered onto blocks of wood. At the age of 10, he was enrolled in the Royal Institute for Blind Youth in Paris. The methods to teach the blind were rudimentary, with teachers talking and reading aloud to the students and with raised letters on a limited number of enormous books.[4] But Louis wanted to read more and learn to write. When life closes a door, it opens another… and fate complied.

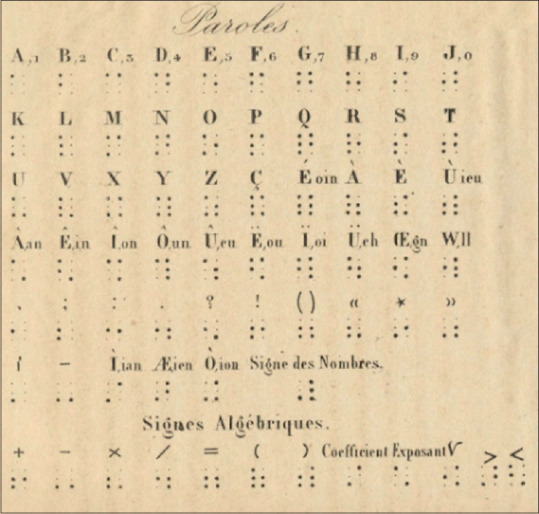

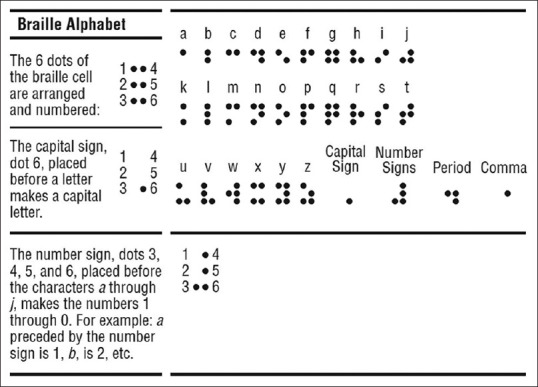

Charles Barbier was a retired artillery captain in Napoleon’s army. He had developed “night writing,” a code for soldiers to communicate in the dark by using 12 raised dots, for tactile perception, representing sounds that comprised words. The soldiers, however, found it too hard and it was never accepted. Barbier decided to present his invention to the school for the blind, hoping for better reception. Twelve-year-old Louis was fascinated and he spent the next two years improving it. He reduced it to 6 dots and simplified the system to represent letters rather than sounds. The fewer dots made it easier to master and faster to read, and the size was small enough for the pattern to fit in a fingertip.[3,5] The 6 dots, 3 dots high and 2 dots wide, were configured into patterns to represent alphabets, spaces, numbers, mathematical symbols, punctuations, and later, even musical notes [Figs. 1 and 2]. The Braille system was nearly completely developed when Louis Braille was only 15.

Figure 1.

Braille’s original code, 1856 (Braille Museum, France) (2)

Figure 2.

The Braille alphabet card (6)

In 1829, he published his first book, Method of Writing Words, Music, and Plain Songs by Means of Dots, for Use by the Blind and Arranged for Them. The students of the blind school loved the new system. The Braille code allowed them to read and write without the requirement of a new vocabulary, grammar, or syntax.[6] The teachers, on the other hand, were far more short-sighted, refusing to recognize the advantages of the code and finding it too difficult to learn. Braille was not accepted as a formal method of teaching despite the students taking up the issue with the French Government, and Braille demonstrating his system even to King Louis-Philippe I in 1834.

Braille became a teacher and the first blind professor in the same school for the blind, teaching algebra, grammar, music, and geography. A talented musician, he saved himself a sufficient sum from his small salary to acquire a piano.[7] A generous and kind man, he would help students with gifts and loans and even gave his position as an organist in a parish to a blind student.[2]

Braille developed tuberculosis and eventually succumbed to it at the tender age of 43 on January 6, 1852. He was buried next to his father and sister in a small cemetery in Coupvray. He could never witness his code being finally approved by the French government two years later in 1854. In 1858, at the World Congress for the Blind, Braille was voted to become the standard system of reading and writing in the world.[3]

Braille has evolved further into contracted or grade 2 forms, saving space, and improving the speed of reading and writing. Today, there are much more technologically advanced reading aids for the blind and visually impaired including optical character recognition voice output reading machines in cell phones, screen readers for computers, portable video magnifiers, and spectacle microscopes, but it is only braille that makes them literate, providing both the means to read and to write. Technology has also helped with the ease of accessibility, softwares translating to multiple languages and converting and printing files into braille. The blind and the visually impaired can communicate, pursue a career, and travel independently with just 6 dots guiding their path.[6]

Hundred years after his death, France publicly recognized the contributions of the remarkable man. He was re-interred on June 22, 1952 in the Pantheon in Paris, in a ceremony attended by the President of France, Jules Vincent Auriol. The coffin was carried through the streets of Paris with all the church bells ringing and rows of blind following Helen Keller. He now, rests beside Victor Hugo, Voltaire, Rousseau, Emile Zola, and Pierre and Marie Curie but his hands, which felt the void as well as tapped the potential, the hands that created the dots and patterns, were placed in a marble box and placed back in his original tomb.[2,3]

“Everything has its wonders, even darkness and silence, and I learn, whatever state I may be in, therein to be content.”

Helen Keller

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1. [Last accessed on 2021 Dec 03]. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/4405/louis-braille.

- 2.Jiménez J, Olea J, Torres J, Alonso I, Harder D, Fischer K. Biography of Louis Braille and invention of the braille alphabet. Surv Ophthalmol. 2009;54:142–9. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2008.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bullock JD, Galst JM. The story of Louis Braille. Arch Ophthalmol. 2009;127:1532–3. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2009.286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. [Last accessed on 2021 Dec 03]. Available from: https://braillebug.org/louis-braille-biography/

- 5. [Last accessed on 2021 Dec 03]. Available from: https://www.nbp.org/ic/nbp/about/aboutbraille/whoislouis.html .

- 6.Massof RW. The role of Braille in the literacy of blind and visually impaired children. Arch Ophthalmol. 2009;127:1530–1. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2009.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roth GA, Fee E. The invention of Braille. Am J Public Health. 2011;101:454. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2010.200865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]