Abstract

Background

Marine protists are an important part of the ocean ecosystem. They may possess unique sets of biosynthetic pathways and, thus, be promising model organisms for metabolic engineering for producing substances for the pharmaceutical, cosmetic, and perfume industries. Currently, full-genome data are available just for a limited number of protists hampering their use in biotechnology.

Methods

We characterized the morphology of a new cultured strain of Thraustochytriaceae isolated from the Black Sea ctenophore Beroe ovata using phase-contrast microscopy. Cell culture was performed in the FAND culture medium based on fetal bovine serum and DMEM. Phylogenetic analysis was performed using the 18S rRNA sequence. We also conducted a transcriptome assembly and compared the data with the closest species.

Results

The protist belongs to the genus Thraustochytrium based on the 18S rRNA sequence analysis. We designated the isolated protist as T. aureum ssp. strugatskii. The closest species with the genome assembly is Schizochytrium aggregatum. Transcriptome analysis revealed the majority of the fatty acid synthesis enzymes.

Conclusion

Our findings suggest that the T. aureum ssp. strugatskii is a promising candidate for biotechnological use. Together with the previously available, our data would allow the establishment of an accurate phylogeny of the family Thraustochytriaceae. Also, it could be a reference point for studying the evolution of the enzyme families.

Keywords: Thraustochytrium, Fatty acids, RNA-seq, Transcriptome assembly, Marine protists

Introduction

Protists are an important part of marine ecosystems (Massana et al., 2015). Analysis of a large set of protist species would allow us to update their systematic position, expand our knowledge of marine ecology (Strassert et al., 2019), and find promising model organisms for use in metabolic engineering (Singh et al., 2014).

Labyrinthulomycetes are heterotrophic protists widely spread in the various marine environments (Mystikou et al., 2014; Pan, Del Campo & Keeling, 2017) and also found in freshwater (Takahashi et al., 2014; Anderson & Cavalier-Smith, 2012). These fungus-like protists belong to Stramenopiles, produce heterokont biflagellate zoospores in the life cycle, and have unique cell organelle called bothrosome, which forms specific filaments of the ectoplasmic network and is considered an apomorphic trait of the group (Porter, 1969; Moss, 1985; Moro et al., 2003; Hamamoto & Honda, 2019). Such cytoplasmic threads provide effective osmotrophic absorption of nutrients, the main nutritional mode for Labyrinthulomycetes (Hamamoto & Honda, 2019). They live as epibionts or endobionts associated with plants or animals as parasites, mutualists, commensals, or saprobes using live or dead organic matter for nutrition (Raghukumar, 2002; Bennet et al., 2017). Their ecological role is usually associated with the decomposition of organic matter and nutrient recycling in the estuarine, coastal, and open ocean ecosystems, including deep-water and anoxic environments (Raghukumar, 2002; Raghukumar & Damare, 2011; Singh et al., 2014).

Taxonomy and phylogenetic relationships within Labyrinthulomycetes at the level of higher taxa are mostly resolved (Tsui et al., 2009; Doi & Honda, 2017). At the lower taxonomic level, it is constantly refined with the emergence of new molecular data (Bennet et al., 2017; Pan, Del Campo & Keeling, 2017). There are two main clades: (a) holocarpic thraustochytrids and (b) plasmodial labyrinthulids and aplanochytrids (Bennet et al., 2017). The most diverse extensively studied family Thraustochytriaceae contains 14 genera (Dellero et al., 2018). Morphological similarity between the Thraustochytrids family members causes nomenclatural errors (Andersen & Ganuza, 2018). In particular, 18S rRNA sequences of Thraustochytrium and Ulkenia form several phylogenetic clades. Probably there are several genetically diverse though morphologically similar species (Yokoyama & Honda, 2007). The use of both 18S rRNA sequences and whole-genome data should clarify their systematic position (Liang et al., 2019; Ju et al., 2019).

Thraustochytrids accumulate a lot of triacylglycerols (Abida et al., 2015; Dellero et al., 2018). They also accumulate significant amounts of polyunsaturated fatty acids (ω-3 LC-PUFAs) with very long chains, in particular omega-3-docosahexaenoic acid (DHA, 22:6 ω3) (Manikan et al., 2015; Aasen et al., 2016; Fan et al., 2007) and eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA, 20:5 ω3) (Chang et al., 2012). EPA and DHA play a key role in cardiovascular health (Lopez-Huertas, 2010) and DHA has a significant role in an infant’s brain and eye development (Mun et al., 2019). Also, these molecules participate in cholesterol and prostaglandin level regulation, thromboxane and leukotriene biosynthesis, and have a role in the development of such diseases as atherosclerosis, asthma, thrombosis, arthritis, and a wide range of tumors (Funk, 2001; Qiu, 2003; Damude & Kinney, 2007). Some Thraustochytrid strains produce arachidonic acid (AA, 20:4 ω6) (Yang et al., 2010; Ou et al., 2016), which is essential for many animals (Muskiet et al., 2004). Moreover, saturated and unsaturated fatty acids could be used as biofuel or have the potential for usage in biotechnology (Singh et al., 2014). The fishery is currently the major source of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (Chang et al., 2012). However, the state of the world fish stocks, ecological consequences of the industrial fishery, and fish oil contamination are troubling (Pauly et al., 2002). Thus, the study of this family biodiversity is important for increasing knowledge of the biochemical pathways of fatty acids in the environment.

Currently, 15 species of Labyrinthulomycetes are known in the Ponto-Caspian basin (Kopytina, 2018, Kopytina, 2019a; Kopytina, 2019b; Popova et al., 2019). Overall, this taxon’s diversity, distribution, and ecology in the Black Sea have not been studied yet. In this study, we characterized a new protist isolated from the Black Sea ctenophore Beroe ovata. Morphological, 18S rRNA, and transcriptome analyses allowed us to show that it belongs to the family Thraustochytriaceae, genus Thraustochytrium. We designated it as T. aureum ssp. strugatskii.

Materials & Methods

Cell culture and cryoconservation

The T. aureum ssp. strugatskii was isolated from dissociated Beroe ovata. Animals were collected in the Black Sea using plastic containers and maintained at room temperature (22–24 °C) in an aquarium for six days. B. ovata were dissociated using the modified protocol from Vandepas et al. (2017). Briefly, animals were cut with scissors in 17% artificial seawater (ASW: artificial sea salt, Red Sea Coral Pro, Red Sea International, Eilat, Israel, dissolved in distilled water) and centrifuged. An equal volume of 0.25% Trypsin-EDTA was added to the sediment, cells were dissociated using an orbital shaker at 500 rpm for 15 min at room temperature. 10% V/V FBS was added to inactivate trypsin. The resulting homogenate was centrifuged twice in ASW for 5 min at 300 g at room temperature to pellet cells. Cells were resuspended and cultured in FAND culture medium: 17‰ ASW, 5% FBS, 5% DMEM (prepared from powder on 17‰ ASW), x0.05 NEAA, x1 PenStrep, all reagents from Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA.

Cells were cultured in 6-well cell culture plates (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) with the mechanical passage: scraped from plastic by 1 ml pipet tip, pipetted hard several times, and an aliquot put into the next well with dilution ratio from 1:10 to 1:1000.

Cryoconservation was performed in a freezing medium containing 90% KnockOut Serum Replacement (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) and 10% DMSO (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) in Mr. Frosty Freezing Container (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) at −80 °C overnight; then cells were transferred to liquid nitrogen for long-term storage.

Cell culture was performed at the Collective Center of ICG SB RAS “Collection of Pluripotent Human and Mammalian Cell Cultures for Biological and Biomedical Research” (https://ckp.icgen.ru/cells/; http://www.biores.cytogen.ru/brc_cells/collections/ICG_SB_RAS_CELL). The cell line is available at the Collective Center.

Analysis of morphology and growth rate

Morphology was observed daily using phase-contrast microscopy under an inverted microscope Observer Z1 (ZEISS, Germany) using a 40×lens and differential interference contrast (DIC). The growth rate was recorded using the automated cell culture and analysis system Cell-IQ (CM Technologies Oy, Finland) using 40×lens and phase contrast technology. Images were taken every 20 min. Cell count and cell population density level were estimated using ImageJ2 (Rueden et al., 2017).

DNA isolation and rRNA sequencing

Genomic DNA was isolated from cells using a PCR buffer with nonionic detergents (PBND) by the protocol adapted from Perkin Elmer Cetus (Higuchi, 1989). We used previously published universal primer sequences for eukaryotic 18S rRNA: F-566 CAG CAG CCG CGG TAA TTC C and R-1200 CCC GTG TTG AGT CAA ATT AAG C (Hadziavdic et al., 2014). PCR was performed using BioMaster HS-Taq PCR-Color (2 ×) (Biolabmix, Russia) in 10 µL reaction volume. Amplification was carried out in a T100 thermal cycler (Bio-Rad, USA) using the following program: 95 °C for 5 min, 40 cycles consisting of 95 °C for 15 s, 60 °C for 15 s, 72 °C for 30 s, and a final extension step of 72 °C for 5 min. PCR products were precipitated by ethanol and amplified with the BigDye Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. Sequencing was done at the “Molecular and Cellular Biology” core facility of the IMCB SB RAS, Russia. Sequence analysis was made using Standard Nucleotide BLAST, blastn (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/), nucleotide collection (nr/nt) database.

RNA isolation and sequencing

Total RNA was extracted from preliminarily centrifuged cells using a Direct-Zol RNA MiniPrep Kit according to the manufacturer’s recommendations (Zymo Research Corporation, Irvine, CA, USA). Three biological replicates were prepared. One of the libraries was prepared from a sample enriched with small motile cells, presumably zoospores. RNA was purified using RNAClean XP (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA) and dissolved in 50 µl of water. RNA quality was measured by the 2100 Bioanalyzer instrument using RNA 6000 Nano Kit (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA ,USA) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations.

Library preparation and barcoding were made with the Illumina TruSeq Stranded mRNA Kit (Illumina Inc, San Diego, CA, USA), single index primers were used for barcoding. Poly(A) RNA enrichment was performed according to the manufacturer’s recommendations, poly(A) fragmentation was four min to produce longer inserts. The first and second cDNA strand synthesis, 3′ adenylation, and adapter ligation were performed strictly according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. Ligation products were purified using AmPureXP (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA). 10 cycles of library amplification were performed using SimpliAmp Thermal Cycler (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Final library purification was achieved with AmPureXP using 0.9 V of magnetic beads, the libraries were washed by 50 µl of water. Quality, concentration, and molarity were measured by the 2100 Bioanalyzer instrument using the High Sensitivity DNA Kit (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The libraries were diluted 10 times before the measurement. The DNA concentrations for three replicas were 5 (motile cell enrichment), 17, and 25 nM, respectively.

Library sequencing was performed with other samples on the NextSeq 550 Sequencing System with NextSeq 500 Mid Output v2 Kit (150 cycles) (Illumina Inc.). We used 150 bp forward single end reads. The number of quality-filtered reads was 19.7 mln, average quality was 30–31.

The raw sequence data sets are available in NCBI BioProject repository, accession number: PRJNA669615. 18S rRNA sequence is deposited in NCBI GenBank (accession number: MW165782).

Transcriptome assembly

Quality control was performed using FastQC v0.11.5 (Andrews, 2010). Adapters and primers were removed in Trimmomatic v.0.3 (Bolger, Lohse & Usadel, 2014) using HEADCROP and ILLUMINACLIP parameters (with built-in SE-library of TruSeq3-SE index adapters). SLIDINGWINDOW:3:20 and MINLEN:36 parameters were used to remove short and low quality reads. Contig assembly was performed using Trinity (Grabherr et al., 2011) with default settings on merged libraries.

Gene annotation

The TransDecoder (https://github.com/TransDecoder) was used for open reading frames search. Markov chains from the Pfam database (Pfam v32) (Finn et al., 2016) were used to find and describe protein domains. GO terms were assigned to Pfam domains according to a previously published protocol (http://current.geneontology.org/ontology/external2go/pfam2go).

Annotation of biochemical pathways was done using KEGG PATHWAY database (Kanehisa, 2002). T. aureum ssp. strugatskii proteins were blasted against the closest species from KEGG (T. aureum and T. roseum) and three animals (Mus musculus, Drosophila melanogaster, and Caenorhabditis elegans). The best hit, its KO (KEGG Orthology) group, and biochemical pathway affiliation were taken.

Phylogenetic analysis of 18S gene

Multiple alignments of the 18S gene were performed using MAFFT v.7 (Katoh & Standley, 2013) with “–add”, “–auto”, and “–keeplength” parameters. Analysis of molecular evolution was carried out with the SAMEM v.0.82 pipeline (Gunbin et al., 2012). FastTree v.2.1.1 (Price, Dehal & Arkin, 2010) was used for estimating the primary topology. The construction of the final phylogenetic tree based on the previously generated substitution model was carried out by Phyml (Si Quang, Gascuel & Lartillot, 2008) by optimization of primary tree topology and branch lengths. We used the aLRT procedure to test the stability of the tree branching points. Tree visualization and topology analysis were performed in FigTree v.1.4.2 (Rambaut & Drummond, 2008, http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree/), Archaeopteryx (https://sites.google.com/site/cmzmasek/home/software/archaeopteryx), and ETE toolkit (Huerta-Cepas, Serra & Bork, 2016).

To accurately determine the relationship of species, we used the combination of phylogenetic trees for individual proteins in the SuperTriplets program (Ranwez, Criscuolo & Douzery, 2010). To identify ortholog protein sets, we used blastp (e-value <0.0001, identity >0.6) for the proteoms of seven species (T. aureum ssp. Strugatskii, S. aggregatum, Aurantiochytrium limacinum, Hondaea fermentalgiana, Aplanochytrium kerguelense, Aurecoccus anophagefferens, and Phytophthora infestans). We selected proteins with a target one-to-one, meaning that all proteins in the set have found each other unequivocally in all pairs for all types in BLAST request. Methods of multiple alignments and phylogenetic analysis are described above.

Results

Morphology and life cycle

We isolated protists from dissociated B. ovata. Cell suspensions from a single animal were plated on 12- or 24-well plates. We observed motile T. aureum ssp. strugatskii cells in about half of the wells, thus the number of protists per animal was probably low. Interestingly, in a separate experiment, we were able to isolate and culture T. kinnei, Aplanochytrium, and Cafeteria. Species identity was based on rRNA sequence analysis (Supplemental Information 1).

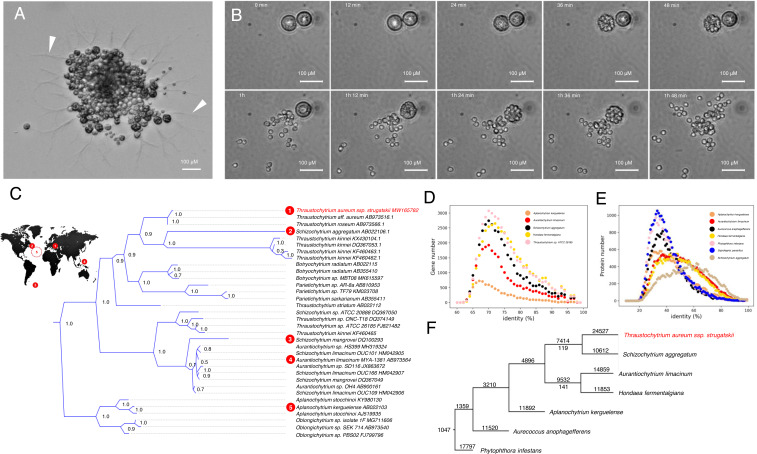

T. aureum ssp. strugatskii morphology is similar to the primary report for T. aureum (Goldstein, 1963). They form large cell conglomerates attached to the substrate in a vegetative phase and can form sporangia. We analyzed about 200 cells on each development phase. The diameter of T. aureum ssp. strugatskii “cells” is 15–65 µm depending on growing time. Cell aggregates with a distinctive ectoplasmic net formed during prolonged culture for several days (Fig. 1A). After the passage, cells stayed at the growth phase during 30–36 h, consequently forming sporangia with a subsequent transformation into new cells. In some cases, the new daughter cells were immobile and formed cell aggregates later; in other cases, we observed many small motile ellipsoidal zoospores. As a result, each sporangium generated more than 20 proportionally smaller daughter cells. Less than 40 min passed between the first visible morphological changes and complete cell separation (Fig. 1B). Zoospores swam rapidly with frequent changes in direction. The population doubling time was about 4.5 h. The amoeboid cells that are typical for some Thraustochytrids (Bongiorni et al., 2005; Jain et al., 2007; Dellero et al., 2018) were not observed in the developmental cycle of the studied protist.

Figure 1. Morphology of T. aureum ssp. strugatskii, phylogenetics, and full-genome data comparison.

(A) Photomicrograph of the cell aggregate, differential interference contrast. There are cells of different sizes and bothrosome (arrows). (B) Photomicrographs of cell division. Time-lapse photography with 12 min interval, phase contrast. (C) Phylogenetic tree of the closest species based on 18S rRNA sequences. Numbers indicate the bootstrap support for each node. Species with full-transcriptome of full-genome data and their place on tree are marked by red circles: (1) –T. aureum ssp. strugatskii, this study, (2-5) BioProject database and JGI (Nordberg et al. 2014). S. mangrovei (5) was collected in the area of the Atlantic at an unspecified location. Their place of collection is shown on the map, details in the Supplemental Information 1. (D) Histogram of the BLAST identity distribution between the proteins of the closest species. Bin equals to 1% identity. (E) Histogram of BLAST identity distribution between the genes of the closest species. Bin equals to 1% identity. (F) The phylogenetic tree of T. aureum ssp. strugatskii closely related species with transcriptome data. The number of sets of orthologous genes for a particular tree node is indicated on the branches of the tree. The world map and scheme of the sampling sites was based on the Al MacDonald map https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:World_map_-_low_resolution.svg, available under license https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/deed.en.

Transcriptome assembly

We generated three RNA-seq libraries from the T. aureum ssp. strugatskii cell culture, in total 31,679,536 single 150 bp reads (4,751,930,400 nucleotides, GC content 60.3%). We removed low- quality reads and assembled 87.9% reads into 42,366 contigs (maximal length 15,414 bp, N50 1,159 bp). We produced 42,366 contigs from combined libraries, which is 20–39% (Supplemental Information 1). 73% of all reads uniquely mapped to the T. aureum ssp. strugatskii transcriptome assembly. We predicted the presence of 85,570 proteins longer than 50 amino acids (Supplemental Information 1).

Phylogenetic analysis

We performed phylogenetic analysis using the T. aureum ssp. strugatskii 18S rRNA sequence. Ninety-eight 18S rRNA genes of 10 family Thraustochytriaceae genera were found using BLAST. The results of the phylogenetic analysis are shown in Fig. 1C and Supplemental Information 2. The closest species are T. aureum and T. roseum (99.73% sequence similarity with AB022110.1 and AB973566.1, respectively). The partial sequence of the 18S rRNA gene is the only one available for these species. The closest species with genome sequence is S. aggregatum (AB022106.1, 84.46% 18S rRNA sequence identity). This species forms an outgroup to T. kinnei in the phylogenetic tree. The other representatives of the genus Schizochytrium do not form one clade, raising doubts about their belonging to the same genus (Dellero et al., 2018; Ju et al., 2019; Liang et al., 2019). Genus Thraustochytrium clusters more compactly but also do not form a separate monophyletic group. Our phylogenetic reconstruction of the Thraustochytriaceae species is in agreement with the previous data (Caamaño et al., 2017), and also points out the necessity of the revision of the family Thraustochytriaceae taxonomy (Dellero et al., 2018; Ju et al., 2019; Liang et al., 2019). Special attention should be given to genera Schizochytrium and Aurantiochytrium as their representatives are dispersedly distributed around the oceans.

Comparison of transcriptome and predicted proteome with other species

We compared transcriptome sequences and predicted open reading frames with the ones available in the databases. The distribution of the identity values of T. aureum ssp. strugatskii transcriptome sequences and predicted proteome sequences with the closest species are presented in Figs. 1D and 1E and Supplemental Information 3. The closest species by protein sequences is S. aggregation with the distribution peak at 62%. It corresponds to the phylogenetic analysis of 18S rRNA sequences. The distribution peak is close to 45% for H. fermentalgiana and A. limacinum. The amounts of homologous genes between T. aureum ssp. strugatskii and KEGG database proteomes are presented in Figs. 1D and 1E. We have found more than 1,700 proteins with identity and coverage of more than 50% with other protists but not with the vertebrates. The phylogenetic tree of species obtained by combining 1047 ortholog trees is shown in Fig. 1F. The number of sets of orthologous genes for a particular tree node is indicated on the branches of the tree. The initial data of the trees and the table of orthologues are attached in the Supplemental Information 2.

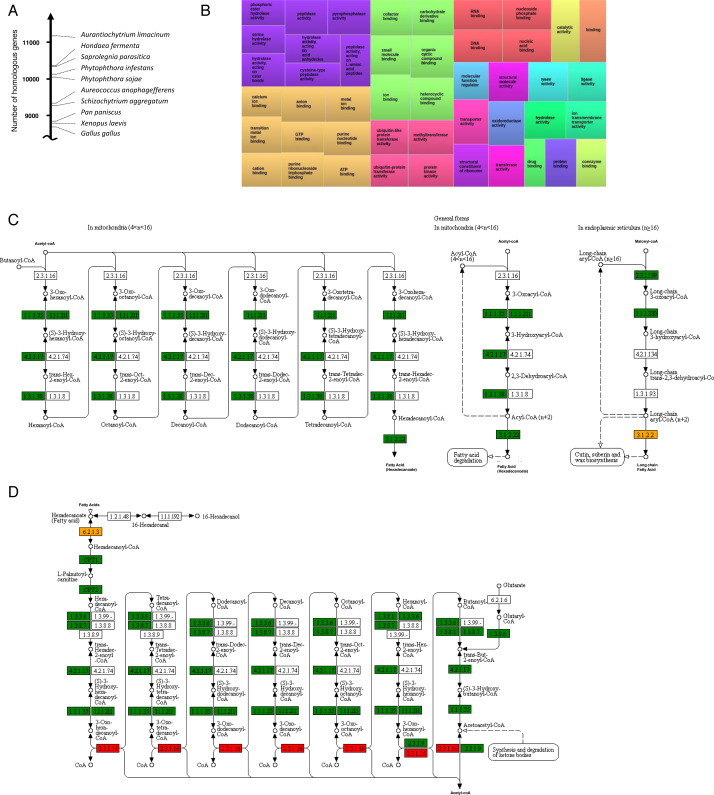

Analysis of proteome and GO terms

For 18,104 proteins of T. aureum ssp. strugatskii we showed homology to known organisms. We identified 286 biochemical pathways of protists involving 2,894 proteins from the studied species. Many biochemical pathways contain a complete set of proteins according to KEGG including biosynthesis of fatty acids. There were no protein complexes for vertebrate intercellular contacts, though both T. aureum ssp. strugatskii and H. fermentalgiana have cadherins (PF00028) which are responsible for calcium-dependent adhesion.

We have found protein domains of enzymes that can decompose organic substrates: amylase (PF00128, PF16657), cellulase (PF00150), lipase (PF01764, PF04083), aspartate protease (PF13650), and xylanase (PF14541, PF14543). These enzymes are also presented in H. fermentalgiana (Supplemental Information 4), amylase was previously found only in two (Aplanochytrium kerguelense and S. aggregatum) out of four species. In addition, T. aureum ssp. strugatskii and H. fermentalgiana have 290 and 306 WD40 proteins (PF00400), respectively, though the other close species about 200. We revealed a relatively large number of PF14312 and PF17210 proteins binding calcium and phosphatases (PF09423). There were relatively small numbers of leucine-rich repeat proteins (PF12799, PF13516) and kinases (PF01163, PF12330, PF12330, and PF06293) compared to other species (Supplemental Information 4).

The protein domain structure was estimated using HMM from Pfam. GO terms were assigned based on protein structure. In total, we revealed 1.699 GO terms (Fig. 2B and Supplemental Information 5). 235 GO terms were observed more than 100 times, such as transition metal ion binding, calcium ion binding, transmembrane transporter activity, oxidoreductase activity, serine-type peptidase activity, and inorganic cation transmembrane transporter activity.

Figure 2. Analysis of the genome and predicted proteome of of T. aureum ssp. strugatskii.

(A) Homologous proteins between T. aureum ssp. strugatskii and the closest species. (B) The frequency of the most represented GO terms. (C) Predicted components of fatty acids synthesis. (D) Predicted components of fatty acids degradation. Visualization of the GO term distribution was made using WEGO 2.0 (http://wego.genomics.org.cn/), visualization of the metabolic pathways is given according to the KEGG database (Kanehisa, 2002).

We consider T. aureum ssp. strugatskii as a promising source of fatty acids for biotechnology, so in our study, we paid special attention to the fatty acid metabolic pathways. We used sequences of 164 H. fermentalgiana proteins (Dellero et al., 2018) and had found 133 homologs in T. aureum ssp. strugatskii. These proteins cover all necessary enzymes for fatty acid synthesis and degradation (Figs. 2C–2D, Supplemental Information 4).

Discussion

A new subspecies of the genus T. aureum, T. aureum ssp. strugatskii, reported here, was isolated when attempting to cultivate in vitro cell culture of the B. ovata from the Black Sea. The species might be associated with B. ovata, but this hypothesis needs further studies. T. aureum ssp. strugatskii has typical for the family Thraustochytriaceae cell morphology, ability to form cell aggregates, and bothrosome (Moro et al., 2003; Hamamoto & Honda, 2019; Ganuza et al., 2019). We were not able to observe the ameboid form, typical for some Labyrinthulomycetes (Moro et al., 2003; Hamamoto & Honda, 2019; Ganuza et al., 2019).

We used the FAND culture medium based on fetal bovine serum and DMEM. To our knowledge, it is the first usage of a modified mammalian cell culture medium for the culture of protists. This medium is rich in nutrients and more expensive than routinely used ones. Nevertheless, our experience shows that the FAND medium is promising for inclusion in the sets of media for newly discovered protists’ cell cultures.

Labyrinthulomycetes taxonomy is mainly based on molecular phylogenetics. The accepted consensus considering molecular and morphological traits seems to be the separation of Labyrinthulomycetes into two clades: thraustochytrids and labyrinthulids with aplanochytrids (Bennet et al., 2017). Phylogenetic analysis based on 18S rRNA sequence confirms that the reported species belongs to genus Thraustochytrium (family Thraustochytriaceae; class Labyrinthulomycetes). We made this conclusion based on good bootstrap support for key nodes. The closest sequences were the ones of T. aureum (seven operative taxonomic units) and T. roseum (one operative taxonomic unit). All sequences had more than 99% pairwise identity. We were not able to distinguish between T. aureum and T. roseum by 18S rRNA. Notably, clusterization of the 18S rRNA sequences had not been measured against their species taxonomic position, thus making necessary a previously proposed revision of the family Thraustochytriaceae systematics (Andersen & Ganuza, 2018; Yokoyama & Honda, 2007; Ju et al., 2019; Liang et al., 2019). Our transcriptome data on Thraustochytrium close the significant gap in the taxon Thraustochytriaceae. From now on, these data are available for genera Aplanochytrium, Aurantiochytrium, Schizochytrium (two entries), and Thraustochytrium (Fig. 1C). In the future, it would allow developing a multilocus genotyping approach for newly described and cultured samples. The used method would be crucial for the revision of the Thraustochytriaceae taxonomy.

Based on proteome analysis we presume that the cadherin (PF00028) protein family could be a possible candidate for calcium-dependent cell adhesion and bothrosome formation. This protein was found in T. aureum ssp. strugatskii and H. fermentalgiana. The comparison of the proteomes by the previously described method (Wang et al., 2019) revealed the marked proximity of T. aureum ssp. strugatskii to S. aggregation, but not to H. fermenta and A. limacinum (Fig. 1B).

Thraustochytrids species are very promising for the production of different fatty acids and their derivatives (Fan et al., 2007; Chang et al., 2012; Abida et al., 2015; Manikan et al., 2015; Aasen et al., 2016; Dellero et al., 2018). For example, squalene (Patel et al., 2019), sterols, and carotenoids (Aki et al., 2003) could be used in the food and cosmetics industries. Also, representatives of the genus Aurantiochytrium can double their biomass in 4–5 h and, therefore, are suitable for use in the bioreactors (Min et al., 2012; Taoka et al., 2011) and wastewater treatment (Hipp & Rodríguez, 2018). We identified 133 homologous enzymes that belonged to all fatty acids biosynthesis pathways described in the KEGG database (Fig. 2C). Thus, we consider that T. aureum ssp. strugatskii is a promising source of fatty acids for biotechnology, as it is accessible to culture and has a high growth rate. Further experiments are needed to assess its potential for fatty acids production.

Substrate-specificity is one of the important features of the Labyrinthulomycetes ecology (Raghukumar & Damare, 2011; Singh et al., 2014; Pan, Del Campo & Keeling, 2017). Thraustochytrids, as well as Aplanochytrids, have been often found in the plankton samples from various open areas of the Ocean, though it is still a challenge to find a substrate these protists are associated with (Bennet et al., 2017). They may be associated with zooplankton fecal pellets and marine snow (Naganuma et al., 2006; Raghukumar, Ramaiah & Raghukumar, 2001; Damare & Raghukumar, 2008) or may live as passive inhabitants of plankton animal guts or their body surface (Damare & Raghukumar, 2010). Even though jellyfish (Cnidaria & Ctenophora) are widely represented in marine plankton, and their gelatinous consistency may facilitate the attachment or development of Labyrinthulomycetes, no reports of protists living in/on plankton jellyfish have been found in the literature. The fact that we isolated a few species of protists from the Beroe ovata animal bodies may indicate such association. Further studies are needed to study the possibility of an association of the Labyrinthulomycetes with pelagic ctenophores or jellyfish. If the protists can actively utilize both waste products and dead remains of gelatinous, this could significantly extend our comprehension of the structure and functioning of the microbial loop as an effective transformer of organic matter in the pelagic ecosystems. Thus, studies of the possible association of Thraustochytrida with gelatinous organisms of the Black Sea seem promising for describing the diversity of this group and assessing its functional role in the ecosystem. To solve this challenge, it is necessary to expand the list of substrates used for studying fungi-like protists in the marine environment to include planktonic jellyfish and ctenophores. The approach for the isolation of Labyrinthulomycetes described in this work could be taken as a basis.

Thus, presented here new protistan subspecies, T. aureum ssp. strugatskii, is a promising candidate for the industrial production of organic substances, and therefore essential for the development of biotechnology. Following studies are needed to confirm the association of the protist with pelagic ctenophores, which could be recommended as a new regular substrate in routine studies of micromycetes in the marine environment, in particular, in the Black Sea.

Conclusions

We isolated and characterized a new subspecies of marine protists, T. aureum ssp. strugatskii (family Thraustochytriaceae) from the Black Sea. Transcriptome data for that species and the previously available would facilitate the subsequent multilocus approach of phylogenetic analysis of the family Thraustochytriaceae. The transcriptome analysis revealed that all necessary enzymes for fatty acid synthesis and degradation are present in the studied species. We assume that the protist has a complete gene set for the metabolism of fatty acids and their derivatives. Thus, T. aureum ssp. strugatskii could be a promising base for the fast development of bioengineered super producers of these substances for the industry and medicine.

Supplemental Information

Acknowledgments

We designated the isolated protist as T. aureum ssp. strugatskii to honor the works of Arkady and Boris Strugatsky.

Funding Statement

The study was supported by the Ministry of Education and Science of the Russian Federation, grant 2019-0546 (FSUS-2020-0040). Part of the work carried out by O.V. Krivenko was done at the Laboratory of Marine Biodiversity and Functional Genomics (created with the support of grant No. 14.W03.31.0015), and was funded by IBSS GA No. 121030100028-0. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Additional Information and Declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare there are no competing interests.

Author Contributions

Dmitrii K. Konstantinov analyzed the data, prepared figures and/or tables, authored or reviewed drafts of the paper, and approved the final draft.

Aleksei Menzorov conceived and designed the experiments, performed the experiments, authored or reviewed drafts of the paper, and approved the final draft.

Olga Krivenko analyzed the data, authored or reviewed drafts of the paper, and approved the final draft.

Alexey V. Doroshkov conceived and designed the experiments, performed the experiments, analyzed the data, prepared figures and/or tables, authored or reviewed drafts of the paper, and approved the final draft.

Data Availability

The following information was supplied regarding data availability:

The data is available at NCBI: MW165782 (18S rRNA); PRJNA669615 (RNA-seq libraries). The FASTA sequences of transcriptome and proteome are also available in the Supplemental File.

New Species Registration

The following information was supplied regarding the registration of a newly described species:

The Thraustochytrium subspecies, Thraustochytrium aureum ssp. strugatskii is registered in MycoBank: 340067.

The cell culture was performed at the Collective Center of ICG SB RAS “Collection of Pluripotent Human and Mammalian Cell Cultures for Biological and Biomedical Research” (https://ckp.icgen.ru/cells/; https://www.biores.cytogen.ru/brc_cells/collections/ICG_SB_RAS_CELL).

The cell culture is deposited at the Collective Center (THAU1, Cat. No. TAHE00071).

The protist is registered in MycoBank: 842785

Name type: Basionym

Classification: Chromista Labyrinthulomycota Labyrinthulomycetes Thraustochytriales Thraustochytriaceae Thraustochytrium

Epithet: aureum ssp. strugatskii

Type specimen or ex type: TAHE00071.

References

- Aasen et al. (2016).Aasen IM, Ertesvåg H, Heggeset TMB, Liu B, Brautaset T, Vadstein O, Ellingsen TE. Thraustochytrids as production organisms for docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), squalene, and carotenoids. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 2016;100(10):4309–4321. doi: 10.1007/s00253-016-7498-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abida et al. (2015).Abida H, Dolch LJ, Meï C, Villanova V, Conte M, Block MA, Finazzi G, Bastien O, Tirichine L, Bowler C, Rébeillé F, Petroutsos D, Jouhet J, Maréchal E. Membrane glycerolipid remodeling triggered by nitrogen and phosphorus starvation in Phaeodactylum tricornutum. Plant Physiology. 2015;167(1):118–136. doi: 10.1104/pp.114.252395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aki et al. (2003).Aki T, Hachida K, Yoshinaga M, Katai Y, Yamasaki T, Kawamoto S, Kakizono T, Maoka T, Shigeta S, Suzuki O, Ono K. Thraustochytrid as a potential source of carotenoids. Journal of the American Oil Chemists’ Society. 2003;80(8):789–794. doi: 10.1007/s11746-003-0773-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen & Ganuza (2018).Andersen RA, Ganuza E. Nomenclatural errors in the Thraustochytridales (Heterokonta/Staminipila), especially with regard to the type species of Schizochytrium. Notulae Algarum. 2018;64:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson & Cavalier-Smith (2012).Anderson OR, Cavalier-Smith T. Ultrastructure of Diplophrys parva, a new small freshwater species, and a revised analysis of Labyrinthulea (Heterokonta) Acta Protozoologica. 2012;51(4):291–304. doi: 10.4467/16890027AP.12.023.0783. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews (2010).Andrews S. FastQC: a quality control tool for high throughput sequence data. 2010. https://qubeshub.org/resources/fastqc https://qubeshub.org/resources/fastqc

- Bennet et al. (2017).Bennet RM, Honda D, Beakes GW, Thines M. Labyrinthulomycota. In: Archibald J, Simpson A, Slamovits C, editors. Handbook of the Protists. Cham: Springer; 2017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger, Lohse & Usadel (2014).Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2014;30(15):2114–2120. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bongiorni et al. (2005).Bongiorni L, Jain R, Raghukumar S, Aggarwal RK. Thraustochytrium gaertnerium sp. nov.: a new thraustochytrid stramenopilan protist from mangroves of Goa, India. Protist. 2005;156(3):303–315. doi: 10.1016/j.protis.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caamaño et al. (2017).Caamaño E, Loperena L, Hinzpeter I, Pradel P, Gordillo F, Corsini G, Tello M, Lavín P, González AR. Isolation and molecular characterization of Thraustochytrium strain isolated from Antarctic Peninsula and its biotechnological potential in the production of fatty acids. Brazilian Journal of Microbiology. 2017;48(4):671–679. doi: 10.1016/j.bjm.2017.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang et al. (2012).Chang KJL, Dunstan GA, Abell GC, Clementson LA, Blackburn SI, Nichols PD, Koutoulis A. Biodiscovery of new Australian thraustochytrids for production of biodiesel and long-chain omega-3 oils. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 2012;93(5):2215–2231. doi: 10.1007/s00253-011-3856-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damare & Raghukumar (2008).Damare V, Raghukumar S. Abundance of thraustochytrids and bacteria in the equatorial Indian Ocean, in relation to transparent exopolymeric particles (TEPs) FEMS Microbiology Ecology. 2008;65(1):40–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2008.00500.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damare & Raghukumar (2010).Damare V, Raghukumar S. Association of the stramenopilan protists, the aplanochytrids, with zooplankton of the equatorial Indian Ocean. Marine Ecology Progress Series. 2010;399:53–68. doi: 10.3354/meps08277. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Damude & Kinney (2007).Damude HG, Kinney AJ. Engineering oilseed plants for a sustainable, land-based source of long chain polyunsaturated fatty acids. Lipids. 2007;42(3):179–185. doi: 10.1007/s11745-007-3049-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dellero et al. (2018).Dellero Y, Cagnac O, Rose S, Seddiki K, Cussac M, Morabito C, Lupette C, Aiese J, Sanseverino CR, Kuntz W, Jouhet M, Maréchal J, Rébeillé E, Amato A. Proposal of a new thraustochytrid genus Hondaea gen. nov. and comparison of its lipid dynamics with the closely related pseudo-cryptic genus Aurantiochytrium. Algal Research. 2018;35:125–141. doi: 10.1016/j.algal.2018.08.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Doi & Honda (2017).Doi K, Honda D. Proposal of M onorhizochytrium globosum gen. nov. comb. nov.(S tramenopiles, L abyrinthulomycetes) for former T hraustochytrium globosum based on morphological features and phylogenetic relationships. Phycological Research. 2017;65(3):188–201. doi: 10.1111/pre.12175. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fan et al. (2007).Fan KW, Jiang Y, Faan YW, Chen F. Lipid characterization of mangrove thraustochytrid- Schizochytrium mangrovei. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2007;55(8):2906–2910. doi: 10.1021/jf070058y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finn et al. (2016).Finn RD, Coggill P, Eberhardt RY, Eddy SR, Mistry J, Mitchell AL, Potter SC, Punta M, Qureshi M, Sangrador-Vegas A, Salazar GA, Tate J, Bateman A. The Pfam protein families database: towards a more sustainable future. Nucleic Acids Research. 2016;44(D1):D279–D285. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funk (2001).Funk CD. Prostaglandins and leukotrienes: advances in eicosanoid biology. Science. 2001;294(5548):1871–1875. doi: 10.1126/science.294.5548.1871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganuza et al. (2019).Ganuza E, Yang S, Amezquita M, Giraldo-Silva A, Andersen RA. Genomics, biology and phylogeny Aurantiochytrium acetophilum sp. nov.(Thraustrochytriaceae), including first evidence of sexual reproduction. Protist. 2019;170(2):209–232. doi: 10.1016/j.protis.2019.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein (1963).Goldstein S. Morphological variation and nutrition of a new monocentric marine fungus. Archiv für Mikrobiologie. 1963;45(1):101–110. doi: 10.1007/BF00410299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabherr et al. (2011).Grabherr MG, Haas BJ, Yassour M, Levin JZ, Thompson DA, Amit I, Adiconis X, Fan L, Raychowdhury R, Zeng Q, Chen Z, Mauceli E, Hacohen N, Gnirke A, Rhind N, Palma F, Birren BW, Nusbaum C, Lindblad-Toh K, Friedman N, Regev A. Trinity: reconstructing a full-length transcriptome without a genome from RNA-Seq data. Nature Biotechnology. 2011;29(7):644–652. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunbin et al. (2012).Gunbin KV, Suslov VV, Genaev MA, Afonnikov DA. Computer system for analysis of molecular evolution modes (SAMEM): analysis of molecular evolution modes at deep inner branches of the phylogenetic tree. In Silico Biology. 2012;11(3, 4):109–123. doi: 10.3233/ISB-2012-0446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadziavdic et al. (2014).Hadziavdic K, Lekang K, Lanzen A, Jonassen I, Thompson EM, Troedsson C. Characterization of the 18S rRNA gene for designing universal eukaryote specific primers. PLOS ONE. 2014;9(2):e87624. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamamoto & Honda (2019).Hamamoto Y, Honda D. Nutritional intake of Aplanochytrium (Labyrinthulea, Stramenopiles) from living diatoms revealed by culture experiments suggesting the new prey–predator interactions in the grazing food web of the marine ecosystem. PLOS ONE. 2019;14(1):e0208941. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0208941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higuchi (1989).Higuchi R. Rapid, efficient DNA extraction for PCR from cells or blood. Amplifications. 1989;2:1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Hipp & Rodríguez (2018).Hipp MPV, Rodríguez DS. Bioremediation of piggery slaughterhouse wastewater using the marine protist. Thraustochytrium kinney VAL-B1. Journal of Advanced Research. 2018;12:21–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jare.2018.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huerta-Cepas, Serra & Bork (2016).Huerta-Cepas J, Serra F, Bork P. ETE 3: reconstruction, analysis, and visualization of phylogenomic data. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 2016;33(6):1635–1638. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain et al. (2007).Jain R, Raghukumar S, Sambaiah K, Kumon Y, Nakahara T. Docosahexaenoic acid accumulation in thraustochytrids: search for the rationale. Marine Biology. 2007;151(5):1657–1664. doi: 10.1007/s00227-007-0608-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ju et al. (2019).Ju JH, Ko DJ, Heo SY, Lee JJ, Kim YM, Lee BS, Kima MS, Kima CH, Seo JW, Oh BR. Regulation of lipid accumulation using nitrogen for microalgae lipid production in Schizochytrium sp. ABC101. Renewable Energy. 2019;153:580–587. doi: 10.1016/j.renene.2020.02.047. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kanehisa (2002).Kanehisa M. Novartis foundation symposium. John Wiley; Chichester; New York: 2002. The KEGG database; pp. 91–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katoh & Standley (2013).Katoh K, Standley DM. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 2013;30(4):772–780. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopytina (2019a).Kopytina N. Moscow: Russian Academy of Sciences; 2019a. Microfungi –animal associations in the ponds of the Ponto-Caspian basins Proceedings of the School of Theoretical and Marine Parasitology; p. 18. (in Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Kopytina (2019b).Kopytina N. Fungi of the Black Sea basin: directions and perspectives of research. Marine Biological Journal. 2019b;4:15–33. doi: 10.21072/mbj.2019.04.4.02. (article in Russian) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liang et al. (2019).Liang L, Zheng X, Fan W, Chen D, Huang Z, Peng J, Zhu J, Tang W, Chen Y, Xue T. Genome and transcriptome analyses provide insight into the omega-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids biosynthesis of schizochytrium limacinum SR21. Frontiers in Microbiology. 2019;11:687. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.00687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Huertas (2010).Lopez-Huertas E. Health effects of oleic acid and long chain omega-3 fatty acids (EPA and DHA) enriched milks. A review of intervention studies. Pharmacological Research. 2010;61(3):200–207. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2009.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manikan et al. (2015).Manikan V, Nazir MYM, Kalil MS, Isa MHM, Kader AJA, Yusoff WMW, Hamid AA. A new strain of docosahexaenoic acid producing microalga from Malaysian coastal waters. Algal Research. 2015;9:40–47. doi: 10.1016/j.algal.2015.02.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Massana et al. (2015).Massana R, Gobet A, Audic S, Bass D, Bittner L, Boutte C, Chambouvet A, Christen R, Claverie J, Decelle J, Dunthorn MDolanJR, Edvardsen B, Forn I, Forster D, Guillou L, Jaillon O, Kooistra W, Logares R, Mahé F, Not F, Ogata H, Pawlowski J, Pernice M, Probert I, Romac S, Richards T, Santini S, Shalchian-Tabrizi K, Siano R, Simon N, Stoeck T, Vaulot D, Zingone A, Vargas C. Marine protist diversity in E uropean coastal waters and sediments as revealed by high-throughput sequencing. Environmental Microbiology. 2015;17(10):4035–4049. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.12955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Min et al. (2012).Min KH, Lee HH, Anbu P, Chaulagain BP, Hur BK. The effects of culture condition on the growth property and docosahexaenoic acid production from Thraustochytrium aureum ATCC 34304. Korean Journal of Chemical Engineering. 2012;29(9):1211–1215. doi: 10.1007/s11814-011-0287-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moro et al. (2003).Moro I, Negrisolo E, Callegaro A, Andreoli C. Aplanochytrium stocchinoi: a new Labyrinthulomycota from the southern ocean (Ross Sea, Antarctica) Protist. 2003;154(3–4):331–340. doi: 10.1078/143446103322454103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss (1985).Moss ST. An ultrastructural study of taxonomically significant characters of the Thraustochytriales and the Labyrinthulales. Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society. 1985;91(1–2):329–357. doi: 10.1111/j.1095-8339.1985.tb01154.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mun et al. (2019).Mun JG, Legette LL, Ikonte CJ, Mitmesser SH. Choline and DHA in maternal and infant nutrition: synergistic implications in brain and eye health. Nutrients. 2019;11(5):1125. doi: 10.3390/nu11051125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muskiet et al. (2004).Muskiet FA, Fokkema MR, Schaafsma A, Boersma ER, Crawford MA. Is docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) essential? Lessons from DHA status regulation, our ancient diet, epidemiology and randomized controlled trials. The Journal of Nutrition. 2004;134(1):183–186. doi: 10.1093/jn/134.1.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mystikou et al. (2014).Mystikou A, Peters AF, Asensi AO, Fletcher KI, Brickle P, Van West P, Convey P, Küpper FC. Seaweed biodiversity in the south-western Antarctic Peninsula: surveying macroalgal community composition in the Adelaide Island/Marguerite Bay region over a 35-year time span. Polar Biology. 2014;37(11):1607–1619. doi: 10.1007/s00300-014-1547-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Naganuma et al. (2006).Naganuma T, Kimura H, Karimoto R, Pimenov NV. Abundance of planktonic thraustochytrids and bacteria and the concentration of particulate ATP in the Greenland and Norwegian Seas. Polar Bioscience. 2006;20:37–45. doi: 10.15094/00006257. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nordberg et al. (2014).Nordberg H, Cantor M, Dusheyko S, Hua S, Poliakov A, Shabalov I, Smirnova T, Grigoriev I, Dubchak I. The genome portal of the Department of Energy Joint Genome Institute: 2014 updates. Nucleic acids research. 2014;42(D1):D26–D31. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ou et al. (2016).Ou MC, Yeong HY, Pang KL, Phang SM. Fatty acid production of tropical thraustochytrids from Malaysian mangroves. Botanica Marina. 2016;59(5):321–338. doi: 10.1515/bot-2016-0031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pan, Del Campo & Keeling (2017).Pan J, Del Campo J, Keeling PJ. Reference tree and environmental sequence diversity of Labyrinthulomycetes. Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology. 2017;64(1):88–96. doi: 10.1111/jeu.12342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel et al. (2019).Patel A, Liefeldt S, Rova U, Christakopoulos P, Matsakas L. Co-production of DHA and squalene by thraustochytrid from forest biomass. Scientific Reports. 2019;10(1):1–12. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-58728-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pauly et al. (2002).Pauly D, Christensen V, Guénette S, Pitcher TJ, Sumaila UR, Walters CJ, Watson R, Zeller D. Towards sustainability in world fisheries. Nature. 2002;418(6898):689–695. doi: 10.1038/nature01017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popova et al. (2019).Popova OV, Belevich TA, Golyshev SA, Kireev II, Aleoshin VV. Labyrinthula diatomea n. sp.—A Labyrinthulid Associated with Marine Diatoms. Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology. 2019;67(3):393–402. doi: 10.1111/jeu.12789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter (1969).Porter D. Ultrastructure of Labyrinthula. Protoplasma. 1969;67(1):1–19. doi: 10.1007/BF01256763. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Price, Dehal & Arkin (2010).Price MN, Dehal PS, Arkin AP. FastTree 2–approximately maximum-likelihood trees for large alignments. PLOS ONE. 2010;5(3):e9490. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu (2003).Qiu X. Biosynthesis of docosahexaenoic acid (DHA 22: 6-4, 7, 10, 13, 16, 19): two distinct pathways. ProstaglandIns, Leukotrienes and Essential Fatty Acids. 2003;68(2):181–186. doi: 10.1016/S0952-3278(02)00268-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raghukumar (2002).Raghukumar S. Ecology of the marine protists, the Labyrinthulomycetes (Thraustochytrids and Labyrinthulids) European Journal of Protistology. 2002;38(2):127–145. doi: 10.1078/0932-4739-00832. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Raghukumar & Damare (2011).Raghukumar S, Damare VS. Increasing evidence for the important role of Labyrinthulomycetes in marine ecosystems. 2011. [DOI]

- Raghukumar, Ramaiah & Raghukumar (2001).Raghukumar S, Ramaiah N, Raghukumar C. Dynamics of thraustochytrid protists in the water column of the Arabian Sea. Aquatic Microbial Ecology. 2001;24(2):175–186. doi: 10.3354/ame024175. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rambaut & Drummond (2008).Rambaut A, Drummond A. Institute of Evolutionary Biology, University of Edinburgh; 2008. FigTree: tree figure drawing tool. [Google Scholar]

- Ranwez, Criscuolo & Douzery (2010).Ranwez V, Criscuolo A, Douzery EJ. SuperTriplets: a triplet-based supertree approach to phylogenomics. Bioinformatics. 2010;26(12):i115–i123. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rueden et al. (2017).Rueden CT, Schindelin J, Hiner MC, De Zonia BE, Walter AE, Arena ET, Eliceiri KW. ImageJ2: ImageJ for the next generation of scientific image data. BMC Bioinformatics. 2017;18(1):1–26. doi: 10.1186/s12859-017-1934-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Si Quang, Gascuel & Lartillot (2008).Si Quang L, Gascuel O, Lartillot N. Empirical profile mixture models for phylogenetic reconstruction. Bioinformatics. 2008;24(20):2317–2323. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh et al. (2014).Singh P, Liu Y, Li L, Wang G. Ecological dynamics and biotechnological implications of thraustochytrids from marine habitats. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 2014;98(13):5789–5805. doi: 10.1007/s00253-014-5780-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strassert et al. (2019).Strassert JF, Jamy M, Mylnikov AP, Tikhonenkov DV, Burki F. New phylogenomic analysis of the enigmatic phylum Telonemia further resolves the eukaryote tree of life. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 2019;36(4):757–765. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msz012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi et al. (2014).Takahashi Y, Yoshida M, Inouye I, Watanabe MM. Diplophrys mutabilis sp. nov. a new member of Labyrinthulomycetes from freshwater habitats. Protist. 2014;165(1):50–65. doi: 10.1016/j.protis.2013.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taoka et al. (2011).Taoka Y, Nagano N, Okita Y, Izumida H, Sugimoto S, Hayashi M. Effect of Tween 80 on the growth, lipid accumulation and fatty acid composition of Thraustochytrium aureum ATCC 34304. Journal of Bioscience and Bioengineering. 2011;111(4):420–424. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiosc.2010.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsui et al. (2009).Tsui CK, Marshall W, Yokoyama R, Honda D, Lippmeier JC, Craven KD, Petersone PD, Berbee ML. Labyrinthulomycetes phylogeny and its implications for the evolutionary loss of chloroplasts and gain of ectoplasmic gliding. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 2009;50(1):129–140. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2008.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandepas et al. (2017).Vandepas LE, Warren KJ, Amemiya CT, Browne WE. Establishing and maintaining primary cell cultures derived from the ctenophore Mnemiopsis leidyi. Journal of Experimental Biology. 2017;220(7):1197–1201. doi: 10.1242/jeb.152371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang et al. (2019).Wang C, Yan Y, Chen X, Al-Farraj SA, El-Serehy HA, Gao F. Further analyses on the evolutionary key-protist Halteria (Protista, Ciliophora) based on transcriptomic data. Zoologica Scripta. 2019;48(6):813–825. doi: 10.1111/zsc.12380. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang et al. (2010).Yang HL, Lu CK, Chen SF, Chen YM, Chen YM. Isolation and characterization of Taiwanese heterotrophic microalgae: screening of strains for docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) production. Marine Biotechnology. 2010;12(2):173–185. doi: 10.1007/s10126-009-9207-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokoyama & Honda (2007).Yokoyama R, Honda D. Taxonomic rearrangement of the genus Schizochytrium sensu lato based on morphology, chemotaxonomic characteristics, and 18S rRNA gene phylogeny (Thraustochytriaceae, Labyrinthulomycetes): emendation for Schizochytrium and erection of Aurantiochytrium and Oblongichytrium gen. nov. Mycoscience. 2007;48(4):199–211. doi: 10.1007/S10267-006-0362-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The following information was supplied regarding data availability:

The data is available at NCBI: MW165782 (18S rRNA); PRJNA669615 (RNA-seq libraries). The FASTA sequences of transcriptome and proteome are also available in the Supplemental File.