Abstract

Introduction

With the advent of the COVID-19 pandemic, health systems increasingly look to digital health solutions to provide support for self-management to people with type 2 diabetes (T2D). This review aimed to assess brief digital behavior change solutions (i.e., solutions that require limited engagement or contact) for T2D, including use of behavior change techniques (BCTs) and their impact on self-care and glycemic control.

Methods

A review was conducted by searching Embase and gray literature using a predefined search strategy to identify randomized controlled trials (RCT) published between January 1, 2015, and March 21, 2021. BCTs were coded using an internationally established BCT taxonomy v1 (BCTTv1).

Results

Out of 1426 articles identified, 10 RCTs were included in qualitative synthesis. Of these, six reported significant improvements in primary outcome(s), including improved patient engagement, glycemic control, self-efficacy, and physical activity. Interventions as short as 12 min were found to be effective, and users’ ability to control their preferences was noted as conducive to engagement. Almost three quarters of BCTs targeted by interventions were under the hierarchical clusters of “Feedback and monitoring,” “Goals and planning,” and “Shaping knowledge.” Interventions that targeted fewer BCTs were at least as effective as interventions that were more comprehensive in their goals.

Discussion

Digital behavior change solutions can successfully improve T2D self-care support and outcomes in a variety of populations including patients with low incomes, limited educational attainment, or living in rural areas. Easy-to-use interventions tailored to patient needs may be as effective as lengthy, complex, and more generalized interventions.

Conclusions

Brief digital solutions can improve clinical and behavioral outcomes while reducing patient burden, fitting more easily in patients’ lives and potentially improving usability. As T2D patients increasingly expect access to self-care assistance between face-to-face encounters, digital support tools will play a greater role in effective diabetes management programs.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s13300-022-01244-w.

Keywords: Brief interventions, Digital health, Behavior change, Type 2 diabetes

Key Summary Points

| Why carry out this review? | |

| Brief digital solutions have the benefit of being highly accessible and convenient as well as easily scalable for population-level care programs. This review assessed the impact of brief digital behavior change solutions for people living with type 2 diabetes (T2D) while also identifying some of the behavior change techniques (i.e., the “active ingredients”) that make these interventions successful | |

| What was learned from the review? | |

| Randomized trials indicate that brief digital solutions can improve T2D patient engagement, glycemic control, self-efficacy, and levels of physical activity | |

| Brief interventions have been evaluated in a variety of populations including patients with low incomes, with limited educational attainments, or living in rural areas. Results suggest that they can address some of the most complex patient needs and social determinants of health while being initiated more easily | |

| Simple, personalized, and short-duration digital solutions can improve diabetic outcomes and represent an important alternative to in-person interventions requiring greater investment of health system resources | |

| Brief, easy-to-use digital solutions can reduce patient burden, increase access to care, improve clinical and behavioral outcomes, and provide patients with control over how and when they engage self-management resources |

Introduction

The global number of adults living with diabetes in 2019 was 463 million, and this number is predicted to increase to 700 million by 2045 [1, 2]. Type 2 diabetes (T2D) makes up 90% of this population and is difficult to manage as multiple lifestyle and self-management behaviors are required to effectively manage and avoid complications, especially in the current COVID-19 pandemic [3]. Behavior change for patients with T2D is made even more difficult because of a number of patients who are impacted by the broader social determinants of health [2]. For these reasons, effective and scalable solutions to support management of T2D at a distance are a priority for health systems worldwide [4].

Since the advent of the COVID-19 pandemic, many health systems have looked to digital health solutions as a way to increase access and self-management support [5]. More than 500 million people use mobile apps to support the management of health conditions, and diabetes apps are among the most commonly used [4]. Digital health tools can be used for screening, monitoring, behavior-change support, and virtual communication with health care providers. Systematic reviews suggest that these tools can improve patients’ self-care behaviors and physiologic health (e.g., glycemic and blood pressure control). Over the last 2 years alone, seven reviews have examined the effectiveness, implementation, and characterization of behavior change interventions with digital components [6–12]. Some reviews have gone farther and attempted to identify the “active ingredients” of effective digital interventions by describing the behavior change techniques used by these interventions as defined by the 2013 Behavior Change Taxonomy (BCTT v1) [13]. The consensus across these reviews is that digital solutions can be effective in improving glycemic control, self-management, and other health-related outcomes.

Despite these encouraging findings, heterogeneity across studies included in these reviews has made it difficult to draw firm conclusions regarding the features of digital solutions that are most beneficial. One way to clarify the characteristics of effective programs is to examine recent trials separately for interventions defined by these salient features. It remains important to identify the characteristics of effective solutions that are individually tailorable and easy to use. This is especially important because of multiple life changes faced by newly diagnosed T2D patients as well as the efforts needed to commit to the extensive behavior changes. “Brief digital solutions,” i.e., tools that require a limited number of contacts, minimal patient data entry, and short engagement times [14] represent a type of digital support tool that can be effective [15, 16], scalable across large populations, and convenient to access compared to in-person support. Given that disengagement is an ongoing concern for digital interventions, understanding the characteristics of brief digital solutions associated with effectiveness is particularly important.

While brief solutions limit patient burden, decreased exposure to behavior change messages may reduce the number of behavior change techniques (BCTs) included, thereby limiting the overall impact. BCTs have been described as the “active ingredients” of interventions and the components within an intervention that are observable, replicable, and specifically designed to change behavior [13]. A standardized taxonomy (BCTTv1) [13] was developed to support identification and comparison of BCTs across interventions in a way that is useful for evaluation purposes. As far as we are aware, no previous review has focused on brief digital solutions for a T2D population with an additional analysis of specific BCTs that those interventions include. The focus of this review was to summarize the literature specific to these types of behavior change interventions. Using a targeted approach to identify relevant published studies and evaluate their findings, we described the evidence for brief digital behavior change solutions with an emphasis on the BCTs that may be associated with greater overall intervention effectiveness.

Methods

Search Strategy and Study Selection

A literature review was conducted using adapted methodology from Cochrane’s Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions [17], and results were reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [18].

Randomized controlled trials published in English between January 2015 and March 2021 and including a brief digital solution were eligible for inclusion. Solutions that were considered “brief” were defined as interventions that have been specifically designed to have a limited number or length of contacts, requiring lower intensity of patient engagement (i.e., minimum input or contact required to achieve results), or requiring relatively little healthcare professional support. Potential studies were first identified by searching the Embase using predefined search strategies including the following terms: “type 2 diabetes,” “digital,” “app,” “virtual,” “mhealth,” “wellbeing,” and “quality of life.” Additionally, conference abstracts from conferences published between 2018 and 2021 were searched, including: American Diabetes Association (ADA), European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD), Advanced Technologies and Treatments for Diabetes (ATTD), International Diabetes Federation (IDF), and Society of General Internal Medicine (SGIM). This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Data Extraction and Analysis

Initial review of all abstracts and proceedings identified by the searches was performed by one investigator. Studies that were found eligible were then reviewed at the full-text stage by the same investigator, and key elements were abstracted.

A standardized data extraction table was generated to systematically identify key information from each publication including characteristics of the patient sample, intervention, and outcomes. Quality control procedures were undertaken to verify the accuracy and completeness of all extracted information.

Behavior Change Technique Analysis

Behavior change techniques included in each intervention were identified based on definitions described in the Behavior Change Techniques Taxonomy Volume 1 (BCTTv1) taxonomy [13]. The frequency of individual BCTs was tabulated and compared across studies. The number and type of various BCTs were summarized descriptively.

Risk of Bias Assessment

An independent investigator assessed the risk of bias of the included studies using the Cochranes’ risk of bias tool [17].

Results

Search results

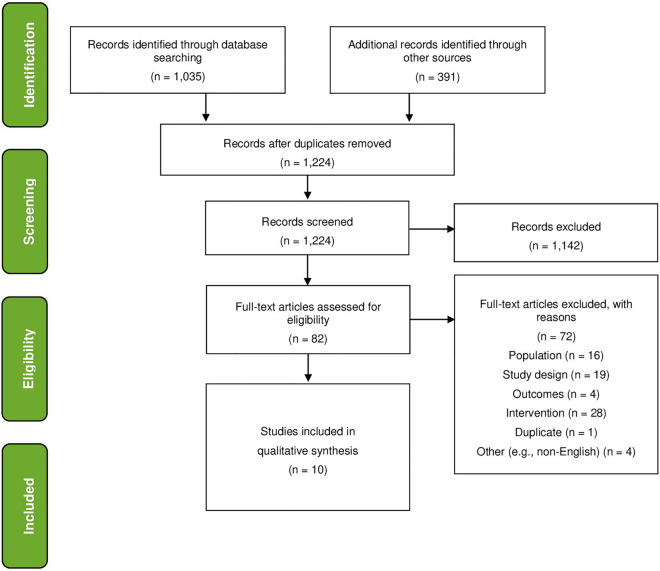

In total, 1426 abstracts were identified from the literature search including 1035 records from Embase and 391 records from conference proceedings. After duplicates were removed, 1224 records were screened by title and abstract. A total of 1104 studies were excluded at this stage, based on the pre-defined search criteria. Eighty-two publications were selected for full-text evaluation and data abstraction. Of those, 19 studies were excluded because they were not randomized controlled trials, 16 were excluded because they did not include patients with T2DM, 6 were excluded because the intervention did not include a brief digital solution, 4 were excluded for other reasons (e.g., non-English language), and 1 was a duplicate publication. A total of 10 studies were included in the final qualitative synthesis. The study selection process is illustrated by the PRISMA flow diagram in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram

Study Characteristics

An overview of study characteristics is included in a table in the outcomes section along with patient characteristics, intervention characteristics, outcome characteristics, and study findings. Of the ten included studies, four were conducted in the USA [19–22] and one each was from South Korea [23], Belgium [24], Mexico [25], Iceland [26], Indonesia [27], and Sri Lanka [28]. All studies were presented as journal articles except for two [21, 25], which were published as conference abstracts. The median length of follow-up was 6 months with a range of 1.2–24 months. One study did not report the follow-up period [21]. Sample sizes ranged from 37 [26] to 2062 [29] with a median of 94 patients.

Patient Characteristics

Of the ten included studies, nine reported participants’ gender and seven reported mean age of the patients. The percentage of females in these studies ranged between 6.1% [20] and 68.0%, [22, 23, 25] with the median being 61.0%. The mean age of participants was 55.1 years with a standard deviation of 4.6 years. Eight studies reported HbA1c at baseline, and of these, the mean was 8.6 with a standard deviation of 0.8.

Five studies provided further specification as to a population subtype: two recruited from a low-income population, one in Mexico [25], and one in an area mainly represented by African Americans [22]. Another two studies recruited patients in the US Department of Veterans Affairs healthcare system, one with poorly controlled diabetes [20] and another specifically from rural areas [21]. Finally, one study recruited only patients with poorly controlled diabetes but from a mix of 19 primary care clinics [19]. Race was reported in two studies with the first study [19] reporting that, although they had some missing data, most participants (76%) were classified as white. The second study [22] reported that 86% of the sample was African American. One study included a sample that was 80% Vietnamese immigrants [19], and one that was mainly low-income Hispanic patients [19].

Three studies reported information about patient comorbidities. The first study that reported comorbidities [26] noted that the average patient had almost five other diagnosed diseases with many patients diagnosed with obesity, high blood pressure, elevated blood lipids, and fibromyalgia. The second study [22] reported a variety of comorbidities from hypertension (78%) to cancer (8%). The last study reporting information about comorbidities specified that investigators excluded participants if they had serious comorbidities such as a history of malignancy, cerebral infarction, or organ transplantation [23].

Intervention Characteristics

Most of the interventions (n = 5) specifically targeted improvement in glycemic control [19, 20, 22, 26, 28]. Three interventions reported combined aims, i.e., diabetes self-efficacy and glycemic control [27] (n = 1) and diabetes self-management and glycemic control [23, 25] (n = 2). Two additional studies were more specific in that one targeted improvement of patient engagement in their virtual visits [21] and another targeted increase in physical activity [24].

Mode of Administration

The most common mode of administration was a smartphone app (n = 4) [23, 26–28], and two interventions were a combination of an app and a website [24] or an app and/or an email [20]. Three studies used a short messaging system (SMS) alone [19], in combination with an in-person program [25], or as an option in an SMS/phone system [22].

Length and Frequency of Digital Solutions

The length and frequency of interventions with the digital solutions are summarized in Table 1. The briefest intervention was a one-time 12-min video created to support veterans living in rural communities to make the best use of their limited contact during virtual consultations (i.e., video telehealth sessions). The video in the form of a DVD was posted to patients so they could watch it at their convenience prior to consultation with a clinician. Other interventions were typically tested over a 6-month period and mainly consisted of text messages or notifications on a daily or weekly basis, two of which were user-defined as the user could adjust the amount of contact either through the app [28] or by texting “STOP” in reply to the messages [19].

Table 1.

Duration and frequency of interventions

| First author | Mode of administration | Intervention duration and frequency |

|---|---|---|

| Gordon [20] | Video on a DVD | One-off view of 12-min video prior to virtual consultation |

| Kerfoot [19] | e-mail or mobile app | 2 “game” questions, twice a week for 6 months to be answered individually and with the option of answering as part of an assigned team |

| Whittemore [29] | In-person group sessions and SMS system | After 7 weekly in-person group sessions, 6 months of daily text messages |

| Gunawardena [27] | Mobile app | Daily or weekly reminders described as user-defined for 6 months |

| Kusnanto [26] | Mobile app | Daily notification messages (6/day) for 3 months |

| Lee [22] | Mobile app | Feedback in the form of short supportive messages via app from health care professions 1–2/week for 6 months |

| Hilmarsdottir [25] | Smartphone app |

Brief weekly messages for 4 months (number not reported) along with individualized encouragement messages through the app from the first author Further 2 months of both types of messages every other week |

| Capozza [18] | SMS system | 1–7 messages daily for 6 months described as user-defined contact because the message “STOP” could be used any time to reduce number of messages |

| Xu [21] | SMS/ phone system with automated contact and bidirectional communication | Average 3 messages weekly with option for bidirectional communication with healthcare provider for 6 months, occurrence was tailored to individual in the event of an abnormal reading or trend being logged |

| Poppe [23] | website and app | Daily and weekly messages in the form of messages or education sessions were made available for 5 weeks |

Control/Comparison Conditions

The most common type of control group (n = 6) was usual care [19, 23, 25, 26, 28], which in one case was reported as a wait-list control [24]. Two studies had comparison groups that consisted of the paper versions of the digital solutions [21, 27], and one study had an active control as the diabetes-based digital game was compared with a digital game that was not diabetes-related. Finally, one study [22] had a reduced contact version of the full intervention where contact was once a week instead of three times and no bidirectional communication with the healthcare provider was included.

Outcomes

Outcome measures and significant findings are summarized in Table 2. Across the 10 included studies, there were 22 outcomes measured with 19 outcomes statistically analyzed for significance. Of these, 11 (58%) showed statistically significant positive effects, with 6 of these outcomes being primary study endpoints and three being secondary outcomes.

Table 2.

Summary of intervention, patient, and outcome characteristics

| Author year | Participants | Intervention and control | Outcome measures | Significant findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Gordon 2020 [20] USA |

87 T2D rural living veterans, HbA1c 8.5% |

12-min video and pamphlet designed to improve provider-patient communication during video consultation Fully digital solution One off session Control: Pamphlet version of provider-patient communication support |

Ratings for post-visit provider-patient therapeutic alliance | Patients who watched a pre-visit educational video before their telehealth video consultation reported higher therapeutic alliance scores post-visit than the control group |

| Gunawardena 2019 [27] Sri Lanka |

67 T2D patients Mean age 52 years, 40% female, HbA1c 9.4% |

Mobile app designed to support glucose management Fully digital solution 6 months Control: Usual care |

App usage HbA1c |

Significantly lower A1c levels compared to the control group were observed over 6 months A1c improvement was positively correlated with app usage with over 80% using the app 8–9 times/week and 52% 12 times or more/week and 78% at 6 months |

|

Kerfoot 2017 [19] USA |

456 T2D veterans, Mean age 60 years, 6.% female, HbA1c 9.0% |

Online diabetes self-management game with integrated teams competition Integrated solution 6 months Control: non-diabetes related game |

HbA1c | The intervention group had significantly greater reductions in mean HbA1c over 6 months compared to the control |

|

Kusnanto 2019 [26] Indonesia |

65 T2D patient 57% female, HbA1c 8.5% |

Diabetes calendar app for SM education program Fully digital solution 3 months Control: Leaflet version of SM education program |

Diabetes management self-efficacy scale (DMSES) HbA1c Cholesterol, triglyceride, LDL-c, insulin level |

The intervention group had a significantly higher self-efficacy scores than the control group The intervention group had a significantly lower mean HbA1c levels than the control group The intervention group had a significantly better cholesterol, triglyceride, LDL-c, and insulin levels than the control group |

|

Poppe 2019 [23] Belgium |

54 T2D patients Mean age 63 years, 27% female |

Website and app designed to increase physical activity and reduce sedentary behavior Fully digital solution 5 weeks Control: Wait-list control |

Accelerometer assessed breaks from sedentary time | The intervention group displayed a significant increase in accelerometer-assessed breaks from sedentary time in comparison with the control group |

|

Capozza 2015 [18] USA |

93 T2D patients Mean age 53 years 61% female |

Two-way SMS system designed to improve glycemic control through coaching, education and testing reminders Fully digital solution 180 days Control: Usual care |

CSQ-8 (8-question Client Satisfaction Questionniare) Satisfaction survey Frequency of engagement HbA1c |

Mean satisfaction score was 27.7/32 at 180 days 85% said “yes” to having improved disease knowledge and management strategies 94% said "yes” they would recommend intervention others 29% demonstrated frequent engagement (texting responses at least 3 × per week for ≥ 90 days) Both groups had decreased HbA1c but there was no significant difference between them |

|

Hilmarsdottir 2020 [25] Iceland |

37 T2D patients Mean age 51yrs, 63% female, HbA1c 7.8% |

Gamified app designed to support healthy lifestyle behaviors with the option to compete with other users Integrated solution 6 months Control: Usual care |

Problem Areas in Diabetes Scale (PAID) Satisfaction survey Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) HbA1c |

There was a significant decrease in the intervention group (but not between groups) in diabetes distress anxiety symptoms and HbA1c levels |

|

Lee 2020 [22] South Korea |

72 T2D patients Mean age 50 years, 68% female, HbA1c 7.4% |

Diabetes self-management education app with individualized feedback from health care professionals via the app Integrated solution 6 months Control: Usual care |

Diabetes Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire (DTSQc) HbA1c |

The intervention group had a significantly higher rates of treatment satisfaction than the control group |

|

Whittemore 2019 [29] Mexico |

47 T2D patients Mean age 56 years, 68% female |

Diabetes self-management group sessions (in-person) followed by a texting system to support behavior change Integrated solution 7.6 months Control: Usual care |

Diabetes self-efficacy Blood glucose monitoring HbA1c |

In the intervention group, HbA1c score, diet, and exercise was significantly improved (but not in comparison to the control) |

|

Xu 2020 [21] USA |

65 low-income, mostly African American T2D patients Mean age 55 years, 68% female, HbA1c 9.5% |

SMS/phone system designed to improve reduce HbA1c and fasting blood glucose (FBG) self-management through automated contact and some bidirectional communication Integrated solution 6 months Control: Reduced version of digital intervention (i.e., weekly only SMS and no bidirectional communication) |

Engagement as measured by proportion responding to ≥ 25% of texts or calls over 4 weeks Fasting blood glucose HbA1c |

Engagement was 58% for the intervention group and 48% for the control group The intervention groups had significantly decreased HbA1c and self-reported fasting blood glucose while the control group did not |

Of the six studies which had significant primary endpoints, three reported significant improvements in glycemic control as measured by HbA1c [20, 27, 28]. The remaining three studies had endpoints which may be broadly described as behavior-related endpoints, and these were improved diabetes self-efficacy as measured with the Diabetes Management Self-Efficacy Scale (DMSES) [27], reduced sedentary behavior as measured by accelerometer [24], and improved patient engagement in video consultations as reported by follow-up telephone interviews [21].

Of the three studies that reported significant secondary outcomes, only one was included in a study that also had a significant primary endpoint [28]. In this study, the reduction in HbA1c was positively correlated with app usage. The remaining two studies which did not have a primary significant outcome reported higher treatment satisfaction rates as measured by the Diabetes Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire (DTSQc) [23] and higher engagement [22] in the intervention group compared to the control group.

Behavior Change Techniques

Across the 10 studies, a total of 86 BCTs were identified with an average of 9 BCTs being reported per study (ranging from 4 to 14 BCTs). BCT characteristics are summarized in Supplementary Table S1. Almost 75% of the BCTs were under three BCCTv1 hierarchical clusters: feedback and monitoring, goals and planning, or shaping knowledge. An analysis that compared studies that had a significant effect of the primary endpoint (n = 6) to the studies which did not (n = 4) did not reveal any differences in the types of BCTs included. However, the number of BCTs included did vary with the significant endpoint group including fewer BCTs on average (i.e., a median of six BCTs) in contrast to the non-significant group (i.e., a median of 12 BCTs).

Risk of Bias

Across the ten included studies, most were generally considered to have a low risk of bias. Due to the nature of the interventions, participant blinding was not possible so blinding of the outcome assessor was evaluated instead. Only one study [21] was labeled as having some concerns, but this was due to the fact that it was presented as a conference abstract and therefore did not include detailed information regarding the methodology even though it appeared that the appropriate analyses had been conducted.

Discussion

The aim of this literature review was to characterize the findings from RCTs on brief digital behavior change solutions implemented within T2D population as well as the specific BCTs that tend to be potentially effective in these interventions. Previous reviews addressing diabetes management and digital health behavior change interventions are plentiful, yet none have focused specifically on impact of brief behavior change interventions. As people living with T2D are faced with intensive daily self-management requirements, easy-to-use interventions hold the promise of greater engagement and the potential of greater impact on behavior and physiologic outcomes.

An important finding of this review is that brief digital behavior change interventions can be very effective. As technology has grown and become more readily accessible, there has been a trend of combining as many components as possible to increase the likelihood of patient engagement. In fact, one of the concerns with focusing on brief interventions was the potential reduction in exposure to BCTs and less overall effectiveness. The data from this review suggest the opposite is true. Interventions with fewer, relatively brief digital solutions such as weekly texts or notifications were found to be at least as effective as more complex services in impacting objective clinical outcomes and behaviors. In one study [26], a simple digital calendar app based on diabetes self-management content was found to result in significantly lower average HbA1c levels relative to randomized controls while at the same time increasing self-efficacy. Another study [20] found that participating in a 6-month game where two diabetes education questions were emailed or texted twice weekly resulted in a sustained reduction of HbA1c at 12 months.

Another key finding of this review is that brief digital solutions are acceptable for a variety of vulnerable and currently underserved populations. A major concern, as digital solutions have flooded the market, is that these tools may not be acceptable among patients who may not normally use digital technology [30–32]. It is well known that social determinants of health such as lack of access to healthcare and ethnic diversity, including healthcare racism and poverty, all contribute to health inequalities [33]. What is less known is how salient brief digital behavior change solutions might be for improving access and outcomes in these priority populations. Within this review, half of the studies that had significantly improved primary endpoints recruited vulnerable patients. T2D patients who were found to benefit substantially from simple, digital solutions included veterans, patients living in rural areas with reduced access to regular healthcare, and low-income adults from Mexico. The brief digital solutions utilized in this study were a one-off 12-min communication video [21], an online diabetes knowledge game [20], and a daily text notification system [27] designed to support behavior change after a diabetes self-management program. The results were improved therapeutic alliance (as evaluated post virtual health consultation), increased blood glucose monitoring, better HbA1c levels, and increased diabetes self-efficacy.

Questions remain regarding how or why these interventions are impactful. An analysis of the studies that demonstrated significant improvements in a primary endpoint revealed few differences relative to studies without a significant improvement with respect to population type (i.e., both groups had studies with vulnerable populations) and length of follow-up (i.e., they were equivalent). However, four of the interventions that had significant effects on primary endpoints were fully digital solutions [21, 24, 27, 28], whereas only one of the studies in the non-significant group was fully digital in nature [19]. Perhaps the digital aspect of the interventions was an advantage as one of the more salient features of digital tools is that they can be individually tailored with relative ease. Tailored approaches have been found to be effective across a variety of health interventions [34, 35].

BCT analysis also found little difference in content when comparing studies that had a significant intervention effect to those that did not. Key categories of BCTs such as feedback and monitoring, goals and planning, and shaping knowledge were common across most studies. This suggests it is not necessarily the type of BCTs included that matters most, but perhaps the amount or total number. However, we found that studies with significant effects had a median of six BCTs while the non-significant studies had a median of 12.

Finally, a key takeaway from this review is that results point toward the importance of taking the user and her/his care experience into consideration. Patient-centered care is vital in the context of self-management, and as digital solutions become more embedded into standard healthcare systems, the development and implementation of user-friendly digital interventions are critical. All studies included in this review had interventions which were not just brief, but also easy to use. Interventions cited in this review suggest that the field has evolved significantly, allowing for greater use of intuitive interfaces and individually tailored programs.

During the COVID-19 era, many healthcare systems have had to identify alternative care delivery strategies to in-person care. This has led many patients and providers to engage with digital solutions for the first time [36, 37]. Over a year and a half into the pandemic, many of the early barriers to digital adaption have dissipated. Now the focus is on increasing patient engagement as low patient participation leads to a low likelihood of success. One study [28] within this review supports this fully, as not only did patients have significantly improved HbA1c levels post-intervention, but this improvement was also positively correlated with the usage of the digital solution. Another study [19], which involved a fully digital two-way SMS system, provided information about the patient experience. Investigators reported high satisfaction results with 95% of participants confirming they would recommend the intervention to others. Importantly, this study reported that a key feature of the intervention was the ability of the patient to define the frequency and nature of the messages received. Patients had a choice of six different message protocols they could enroll in (e.g., medication reminders or tracking and encouragement) but maybe most importantly the program could be turned off easily at any time by texting the word “STOP.” This illustrates how important autonomy is for behavior change.

Although it was not explicitly reported across most studies, it is likely that the digital nature of these brief interventions offered the opportunity for patient-generated health data. This is also advantageous for healthcare providers, to be used as feedback about patient preferences and patient-reported outcomes. As long as such data are used ethically and with clear consent, the wealth of data that can be gathered from digital solutions creates the opportunity for scalable interventions to have a wider reach in usability.

Strengths and Limitations

A strength of this review is the inclusion of robust evidence (i.e., RCTs only) and the focus on brief solutions, which to our knowledge has not been examined before in combination with a behavior change technique analysis. Brief digital solutions are particularly scalable across large populations so evaluation of their impact compared to a control group or standard care is important. A limitation of this review is that results from these types of studies can be difficult to generalize to the real-world context as well as the lack of homogeneity across study interventions and outcomes. Conclusions need to be considered in light of these limitations.

Conclusion

Simple digital solutions can be very impactful as a part of behavior change interventions for patients with T2D. This is especially compelling considering growing and diverse global rates of type 2 diabetes. Brief digital solutions were found to be beneficial across a variety of underserved and vulnerable population types. Analysis of the BCTs (i.e., the “active ingredients”) revealed that an increased number of BCTs was not associated with more effective interventions. The decreased exposure to BCTs, often considered a limitation of brief interventions, was not found to limit their impact on diabetes self-care or glycemic control. Brief digital solutions that are easy to use can reduce patient burden, effectively influence clinical and behavioral outcomes, and give patients the opportunity to choose how and when they engage with their self-management most successfully. This review highlights the lack of evidence on the impact of digital solutions and the need for consistent definitions and standardized assessments. Further research is needed for a taxonomy for optimal categorization of interventions.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Funding

This literature review and journal’s Rapid Service Fee was funded by Sanofi and performed by Evidinno Outcomes Research Inc.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Author Contributions

Cecile Baradez conceived and designed the analysis and contributed to analysis/interpretation. Jan Liska and Claire Brulle-Wohlhueter contributed to analysis design and analysis/interpretation. Divya Pushkarna collected the data and contributed to writing the paper. Mike Baxter and John Piette contributed to analysis/interpretation and writing the paper. All authors approved the final draft of this manuscript.

Medical Writing, Editorial, and Other Assistance

The authors would like to thank Sylvie Coumel and Anastasia Ukhova, from Sanofi, for their valuable contributions in developing the design of the study. The authors would also like to thank Ana Howarth, from Evidinno, for providing methodological support in conducting the literature review. Medical writing assistance was provided by Evidinno and was funded by Sanofi.

Disclosures

Cecile Baradez, Jan Liska, and Claire Brulle-Wohlhueter report employment by Sanofi and may hold shares and/or stock options in the company. Divya Pushkarna reports full-time employment by Evidinno Outcomes Research Inc. Mike Baxter and John Piette have nothing to disclose.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Data Availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

References

- 1.Unnikrishnan R, Pradeepa R, Joshi SR, Mohan V. Type 2 diabetes: demystifying the global epidemic. Diabetes. 2017;66(6):1432–1442. doi: 10.2337/db16-0766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.International Diabetes Federation. IDF Diabetes Atlas 9th edition 2019 [Available from: https://www.diabetesatlas.org/en/.

- 3.Hartmann-Boyce J, Morris E, Goyder C, Kinton J, Perring J, Nunan D, et al. Diabetes and COVID-19: risks, management, and learnings from other national disasters. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(8):1695–1703. doi: 10.2337/dc20-1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gonzalez JS, Tanenbaum ML, Commissariat PV. Psychosocial factors in medication adherence and diabetes self-management: Implications for research and practice. Am Psychol. 2016;71(7):539–551. doi: 10.1037/a0040388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Quinn LM, Davies MJ, Hadjiconstantinou M. Virtual consultations and the role of technology during the COVID-19 pandemic for people with Type 2 diabetes: the UK perspective. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(8):e21609. doi: 10.2196/21609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wong SKW, Smith HE, Chua JJS, Griva K, Cartwright EJ, Soong AJ, et al. Effectiveness of self-management interventions in young adults with type 1 and 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabet Med. 2020;37(2):229–241. doi: 10.1111/dme.14190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kebede MM, Liedtke TP, Mollers T, Pischke CR. Characterizing active ingredients of ehealth interventions targeting persons with poorly controlled type 2 diabetes mellitus using the behavior change techniques taxonomy: scoping review. J Med Internet Res. 2017;19(10):e348. doi: 10.2196/jmir.7135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang W, Cheng MTM, Leong FL, Goh AWL, Lim ST, Jiang Y. The development and testing of a nurse-led smartphone-based self-management programme for diabetes patients with poor glycaemic control. J Adv Nurs. 2020;76(11):3179–3189. doi: 10.1111/jan.14519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Celik A, Forde R, Sturt J. The impact of online self-management interventions on midlife adults with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review. Br J Nurs (Mark Allen Publish) 2020;29(5):266–272. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2020.29.5.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Groot J, Wu D, Flynn D, Robertson D, Grant G, Sun J. Efficacy of telemedicine on glycaemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis. World J Diabetes. 2021;12(2):170–197. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v12.i2.170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aminuddin HB, Jiao N, Jiang Y, Hong J, Wang W. Effectiveness of smartphone-based self-management interventions on self-efficacy, self-care activities, health-related quality of life and clinical outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Nurs Stud. 2019;116:103286. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2019.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Van Rhoon L, Byrne M, Morrissey E, Murphy J, McSharry J. A systematic review of the behaviour change techniques and digital features in technology-driven type 2 diabetes prevention interventions. Digital Health. 2020;6:2055207620914427. doi: 10.1177/2055207620914427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Michie S, Richardson M, Johnston M, Abraham C, Francis J, Hardeman W, et al. The behavior change technique taxonomy (v1) of 93 hierarchically clustered techniques: building an international consensus for the reporting of behavior change interventions. Ann Behav Med Publ Soc Behav Med. 2013;46(1):81–95. doi: 10.1007/s12160-013-9486-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Werch C, Grenard JL, Burnett J, Watkins JA, Ames S, Jobli E. Translation as a function of modality: the potential of brief interventions. Eval Health Prof. 2006;29(1):89–125. doi: 10.1177/0163278705284444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee JL, Foschini L, Kumar S, Juusola J, Liska J, Mercer M, et al. Digital intervention increases influenza vaccination rates for people with diabetes in a decentralized randomized trial. npj Digit. Med. 2021;4(1):138. doi: 10.1038/s41746-021-00508-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oosterveen E, Tzelepis F, Ashton L, Hutchesson MJ. A systematic review of eHealth behavioral interventions targeting smoking, nutrition, alcohol, physical activity and/or obesity for young adults. Prev Med. 2017;99:197–206. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2017.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Higgins JP, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, et al. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Hoboken: Wiley; 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moher D, Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(4):264. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Capozza K, Woolsey S, Georgsson M, Black J, Bello N, Lence C, et al. Going mobile with diabetes support: a randomized study of a text message-based personalized behavioral intervention for type 2 diabetes self-care. Diabetes Spectrum. 2015;28(2):83–91. doi: 10.2337/diaspect.28.2.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kerfoot BP, Gagnon DR, McMahon GT, Orlander JD, Kurgansky KE, Conlin PR. A team-based online game improves blood glucose control in veterans with type 2 diabetes: a randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care. 2017;40(9):1218–1225. doi: 10.2337/dc17-0310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gordon H, Pugach O, Solanki P, Gopal RK. A brief pre-visit educational video improved patient engagement after clinical video telehealth visits; results from a randomized controlled trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(SUPPL 1):S3. doi: 10.1016/j.pecinn.2022.100080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xu R, Xing M, Javaherian K, Peters R, Ross W, Bernal-Mizrachi C. Improving HbA<inf>1c</inf> with Glucose self-monitoring in diabetic patients with EpxDiabetes, a phone call and text message-based telemedicine platform: a randomized controlled trial. Telemed J e-health Off J Am Telemed Assoc. 2020;26(6):784–793. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2019.0035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee DY, Yoo SH, Min KP, Park CY. Effect of voluntary participation on mobile health care in diabetes management: randomized controlled open-label trial. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2020;8(9):e19153. doi: 10.2196/19153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Poppe L, De Bourdeaudhuij I, Verloigne M, Shadid S, Van Cauwenberg J, Compernolle S, et al. Efficacy of a self-regulation-based electronic and mobile health intervention targeting an active lifestyle in adults having type 2 diabetes and in adults aged 50 years or older: two randomized controlled trials. J Med Internet Res. 2019;21(8):e13363. doi: 10.2196/13363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Whittemore R, Vilar-Compte M, De La Cerda S, Delvy R, Jeon S, Burrola-Mendez SI, et al. Yo puedo! A self-management group and mHealth program for low-income adults with type 2 diabetes in Mexico City. In: Diabetes Conference: 79th Scientific Sessions of the American Diabetes Association, ADA. 2019;68(Supplement 1).

- 26.Hilmarsdottir E, Sigurdardottir AK, Arnardottir RH. A digital lifestyle program in outpatient treatment of type 2 diabetes: a randomized controlled study. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2020 doi: 10.1530/endoabs.65.P221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kusnanto WKAJ, Suprajitno AH. DM-calendar app as a diabetes self-management education on adult type 2 diabetes mellitus: a randomized controlled trial. J Diabetes Metab Dis. 2019;18(2):557–63. doi: 10.1007/s40200-019-00468-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gunawardena KC, Jackson R, Robinett I, Dhaniska L, Jayamanne S, Kalpani S, et al. The influence of the smart glucose manager mobile application on diabetes management. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2019;13(1):75–81. doi: 10.1177/1932296818804522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nanditha A, Thomson H, Susairaj P, Srivanichakorn W, Oliver N, Godsland IF, et al. A pragmatic and scalable strategy using mobile technology to promote sustained lifestyle changes to prevent type 2 diabetes in India and the UK: a randomised controlled trial. Diabetologia. 2020;63(3):486–496. doi: 10.1007/s00125-019-05061-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cascella L. Virtual risk: an overview of telehealth from a risk management perspective. Disponibile online su www medpro com/documents/10502/2820774/Virtual+ Risk+-+ An+ Overview+ of+ Telehealth pdf. 2014.

- 31.Smith E. American telemedicine association applauds landmark expansion of Medicare telehealth coverage. American Telemedicine Association. 2018.

- 32.Scott Kruse CKP, Shifflett K, Vegi L, Ravi K, Brooks M. Evaluating barriers to adopting telemedicine worldwide: a systematic review. J Telemed Telecare. 2018;24(1):4–12. doi: 10.1177/1357633X16674087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hill-Briggs F, Adler NE, Berkowitz SA, Chin MH, Gary-Webb TL, Navas-Acien A, et al. Social determinants of health and diabetes: a scientific review. Diabetes Care. 2020;44(1):258–279. doi: 10.2337/dci20-0053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ryan K, Dockray S, Linehan C. A systematic review of tailored eHealth interventions for weight loss. Digit Health. 2019;5:2055207619826685. doi: 10.1177/2055207619826685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lustria ML, Noar S, Cortese J, Van Stee S, Glueckauf R, Lee J. A meta-analysis of web-delivered tailored health behavior change interventions. J Health Commun. 2013;18. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Rani R, Kumar R, Mishra R, Sharma SK. Digital health: a panacea in COVID-19 crisis. J Fam Med Primary Care. 2021;10(1):62–65. doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_1494_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hernandez-Ramos R, Aguilera A, Garcia F, Miramontes-Gomez J, Pathak LE, Figueroa CA, et al. Conducting internet-based visits for onboarding populations with limited digital literacy to an mhealth intervention: development of a patient-centered approach. JMIR Format Res. 2021;5(4):e25299. doi: 10.2196/25299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.