Abstract

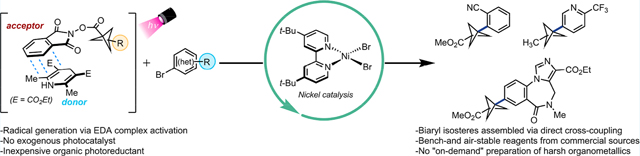

The use of bicyclo[1.1.l]pentanes (BCPs) as para-disubstituted aryl bioisosteres has gained considerable momentum in drug development programs. Carbon–carbon bond formation via transition-metal-mediated cross-coupling represents an attractive strategy to generate BCP–aryl compounds for late-stage functionalization, but these typically require reactive organometallics to prepare BCP nucleophiles on demand from [l.1.l]propellane. In this study, the synthesis and Ni-catalyzed functionalization of BCP redox-active esters with (hetero)aryl bromides via the action of a photoactive electron donor–acceptor complex are reported.

Graphical Abstract

The operational ease of Pd-catalyzed C(sp2)–C(sp2) coupling reactions along with the availability of coupling partners (in particular, arylboronates and aryl halides) has resulted in a bias toward biaryl-containing molecules in drug development programs.1 These cross-coupling platforms have enabled the synthesis of diverse biaryl-containing drugs targeting a wide swath of therapeutic areas. However, considerable interest has developed in recent years to investigate sp3-rich aryl isosteres in drug development programs.2

Of particular interest is the bicyclo[l.1.l]pentane (BCP) motif, which has been reported most commonly as a p-disubstituted aryl motif but also as a tert-butyl or alkyne bioisostere, often imparting favorable pharmacokinetic properties, including improved aqueous solubility and membrane permeability.3

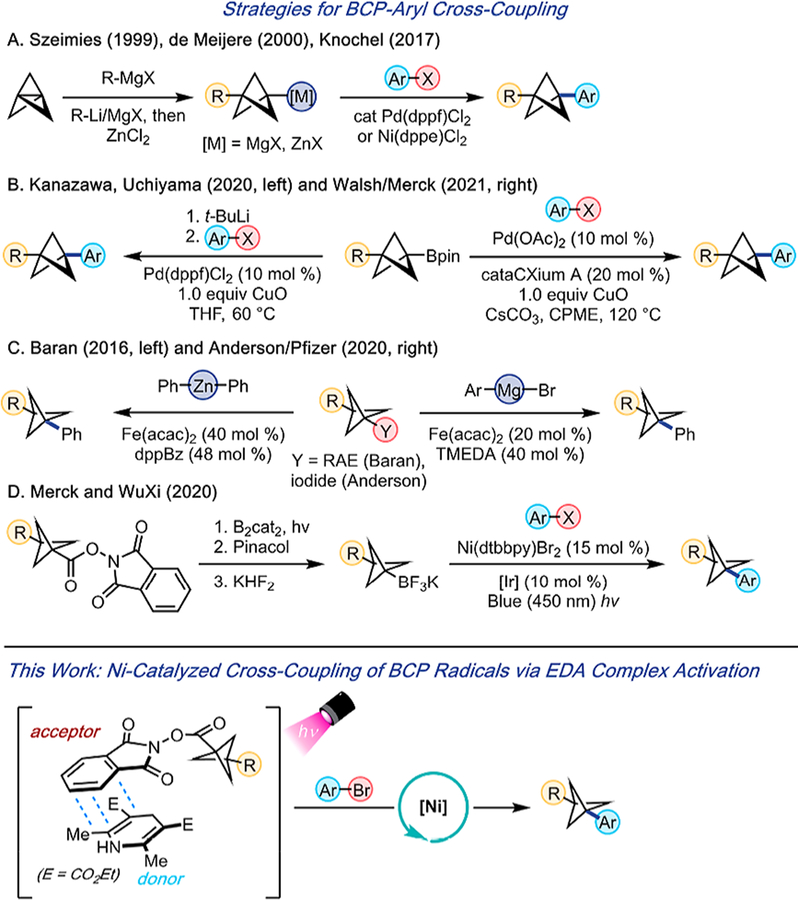

Although considerable advancements have been made in the synthesis of BCP-containing targets,4–6 the methods available to forge BCP–aryl products via direct cross-coupling are somewhat limited. Szeimies and co-workers,7 de Meijere and co-workers,8 and Knochel and co-workers9 have reported Kumada- and Negishi-type couplings between aryl halides and the corresponding BCP organometallic reagents (Figure 1A). Additionally, Kanazawa, Uchiyama, and co-workers10 reported a Suzuki-type coupling using l,3-difunctional silyl BCP boronates. Shortly after, the Walsh group, in collaboration with scientists at Merck,11 disclosed the use of l,3-difunctional benzylamine BCP boronates in Suzuki couplings (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Comparison of two- and one-electron strategies to forgi BCP–aryl cross-coupling products.

Leveraging a radical-based mechanism, Baran and co-workers12 reported the cross-coupling of a single BCP redox-active ester (RAE) with Ph2Zn. Anderson and co-workers, in collaboration with Pfizer,13 then reported the iron-catalyzed Kumada coupling of various BCP iodides with aryl Grignard reagents (Figure 1C). In 2020, VanHeyst, Qi, and co-workers from Merck and WuXi engaged BCP trifluoroborate salts in Ni/photoredox dual cross-coupling and achieved modest to acceptable yields (Figure 1D).14 Of note and particular pertinence to the results reported herein, the BCP trifluoroborate salts required preparation through a continuous flow photoborylation method from the corresponding N-(acyloxy)-phthalimide redox active esters (RAEs).14,15

Although BCP organometallic reagents perform well as cross-coupling partners, their applicability in late-stage functionalization is limited because of their functional group incompatibility and short-term stability. To address these shortcomings, we envisioned employing bench stable, commercially available BCP carboxylic acid feedstocks under mild, Ni-catalyzed photochemical conditions.16

The initial goal was to use carboxylic acids directly in Ni/photoredox dual cross-coupling. Encouragingly, we established suitable conditions for the decarboxylation of a BCP carboxylate and verified that the resultant BCP radical engages in defluorinative alkylation with a trifluoromethyl-substituted alkene (Scheme S1A of the Supporting Information). However, adapting these conditions to Ni-catalyzed C–C bond formation with 4-bromobenzonitrile failed to generate the desired arylated BCP product.

Under dilute reaction conditions (0.025 M instead of 0.1 M), the corresponding BCP aryl ester was observed exclusively (Scheme S1B of the Supporting Information). This result can be rationalized by the high s character of the BCP–carboxylate bond (~sp21),6 resulting in a slower rate of decarboxylation, thus favoring an energy-transfer-dependent C–O coupling.17,18

These results motivated us to investigate the activation of BCP–N-(acyloxy)phthalimide RAEs, bench-stable solids that are readily prepared from the corresponding carboxylic acids via a quantitative Steglich esterification. These derivatives undergo decarboxylative radical fragmentation upon single-electron reduction19 through photochemical strategies that are unavailable to the parent carboxylic acids.20 In this vein, our group recently reported the nickel-catalyzed cross-coupling of primary and secondary alkyl RAEs with (hetero)aryl halides using Hantzsch ester (HE) as a potent organic photoreductant.20 The intermediacy of a photoactive electron donor–acceptor (EDA) complex21–25 was envisioned to facilitate the generation and subsequent functionalization of BCP radicals in Ni-catalyzed cross-electrophile paradigms, bypassing the need for preformed carbon nucleophiles as well as electron transfer events from exogenous photoredox catalysts. In addition, the developed protocol would provide a low barrier for practical implementation in medicinal chemistry settings.

Subsequently, we successfully adapted our previously reported conditions to the cross-coupling of a BCP RAE (1,3-dioxoisoindolin-2-yl bicyclo[1.1.1]pentane-1-carboxylate) with 4-((4-bromophenyl)sulfonyl)morpholine in modest yield (Table S1 of the Supporting Information). The addition of a mild base, such as NaHCO3 or K2HPO4, improved the cross-coupling yield by diminishing the loss of the BCP radical to Minisci-type addition (SI-21) to Hantzsch pyridine, which is generated upon photoaromatization.

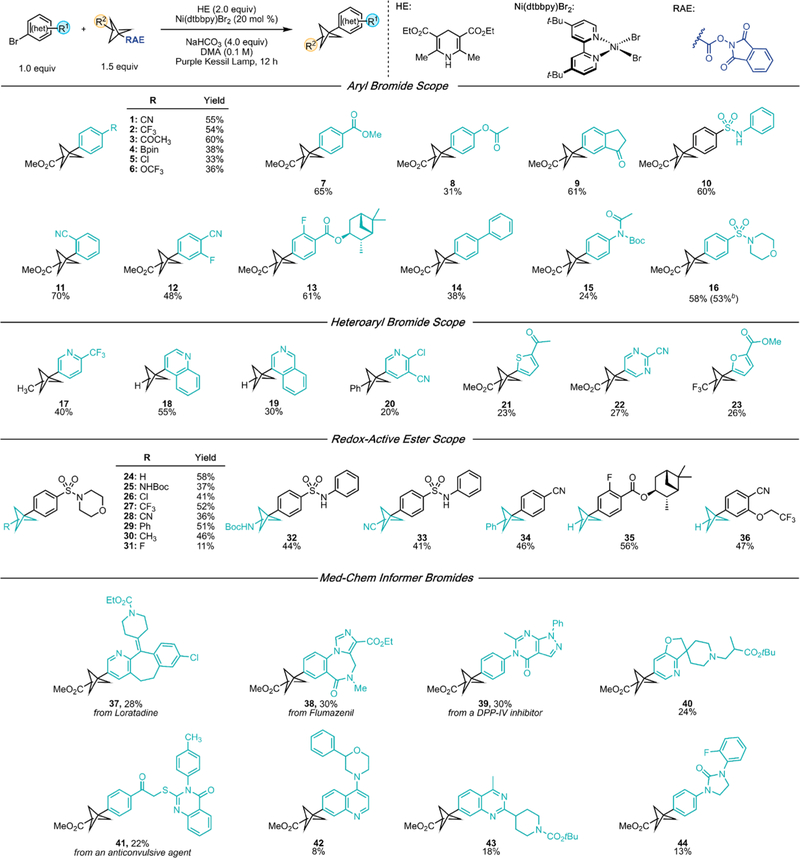

With suitable conditions established (see the Supporting Information for full optimization details), we proceeded to investigate the scope of aryl bromides amenable to the cross-coupling protocol (1–16, Scheme 1). In general, the best yields were obtained using aryl bromides bearing electron- withdrawing groups. Modest product formation was observed with electron-rich and electron-neutral aryl bromides because of competitive proto-debromination. Electrophilic and protic functional groups were well-tolerated (in contrast with cross-coupling methods based on organometallic reagents), including several synthetic handles found in substrates, such as boronate 4, chloride 5, ester 7, and amide 15. Selected heteroaromatic bromides were accommodated and did not engage in Minisci-type side reactivity, giving modest to synthetically acceptable cross-coupling yields (17–23). Of particular note, pyridine 20 bears a 2-Cl handle for diversification via SNAr, and the successful preparation of furan 23 was made possible by this net-reductive cross-electrophile platform. Importantly, these reductively and oxidatively sensitive systems are traditionally challenging structures in cross-couplings mediated by external photoredox catalysts, further underscoring the selectivity using the EDA paradigm. Finally, comparable reactivity was observed for product 16 using 3.3 mmol (1.0 g) of aryl bromide instead of 0.5 mmol.

Scheme 1. Cross-Coupling Scope: Evaluation of BCP RAEs and (Hetero)aryl Bromidesa.

aValues refer to isolated yields. Unless otherwise noted, reactions were performed using ArBr (1 equiv, 0.5 mmol), RAE (1.5 equiv, 0.75 mmol), HE (2 equiv, 1.0 mmol), Ni(dtbbpy)Br2 (20 mol %, 0.10 mmol), NaHCO3 (4 equiv, 2.0 mmol), and dry, degassed DMA (5.0 mL). Irradiation was performed at room temperature using a 390 nm Kessil lamp with fan cooling. bThe reaction was performed using 3.3 mmol of ArBr (1.0 g).

In further investigations using 4-((4-bromophenyl)sulfonyl)-morpholine as a standard aryl bromide, the method was demonstrated to be amenable to a wide range of BCP RAEs with varying bridgehead substitutions (24–31). In particular, very few BCP–aryl compounds with amino-(27),26–29 Cl-(28),8 CF3-(29),30 CN-(30),28 and F-(33)31 bridgehead substitutions have been reported, and to our knowledge, none has been prepared via direct cross-coupling. Furthermore, the current method is proven to be more versatile than that of VanHeyst, Qi, and co-workers,14 who were unsuccessful in employing NHBoc-, CF3-, and CN-BCP trifluoroborates in Ni/photoredox cross-coupling. Finally, we underscored the utility of the method by engaging the BCP radical with several bromides bearing functionally dense, medicinally relevant structures (37–44). Under the developed conditions, late- stage functionalization of diverse scaffolds can be accomplished, including aryl chloride 37, imidazole 38, quinoline 42, quinazoline 43, and urea 44. Notably, tertiary amines (40 and 42), often present in biologically active substances to modulate pharmacokinetic properties but typically susceptible to SET oxidation with traditional photoredox catalysts, can be accessed, albeit in low yields.34

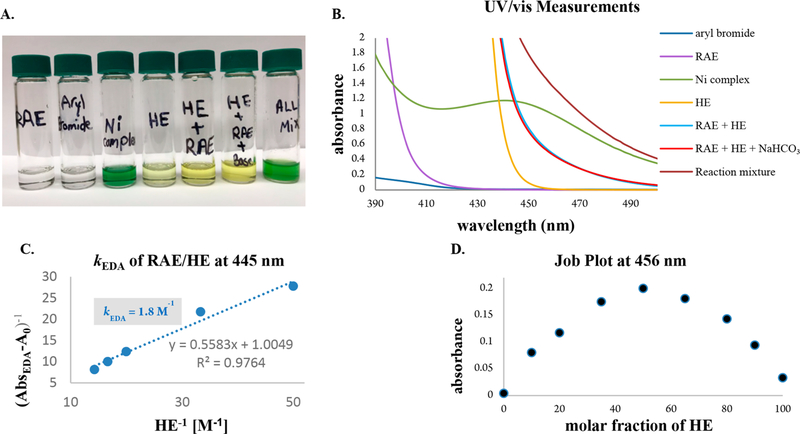

To lend evidence for the intermediacy of an EDA complex, we measured ultraviolet/visible (UV/vis) absorption spectra for individual reaction components and mixtures thereof (Figure 2B). Although the RAE (violet line) and HE (golden line) absorb in the visible light region, they undergo a bathochromic shift (blue line) when combined, indicating the presence of charge-transfer aggregates. Indeed, the color change is apparent to the naked eye (Figure 2A). The association constant of the EDA complex and analysis via Job’s method demonstrated a 1:1 molar stoichiometry (panels C and D of Figure 2).

Figure 2.

(A) Visual appearance of individual reaction components and mixtures thereof. (B) UV/vis absorption spectra measured in DMA (0.1 M). Aryl bromide, 4-((4-bromophenyl)sulfonyl)morpholine; RAE, 1,3-dioxoisoindolin-2-yl bicyclo[1.1.1]pentane-1-carboxylate; Ni complex, Ni(dtbbpy)Br2; and HE, diethyl 2,6-dimethyl-1,4-dihydropyridine-3,5-dicarboxylate. (C) Benesi–Hildebrand plot.32 (D) Job plot33 for a mixture of RAE and HE (0.2 M).

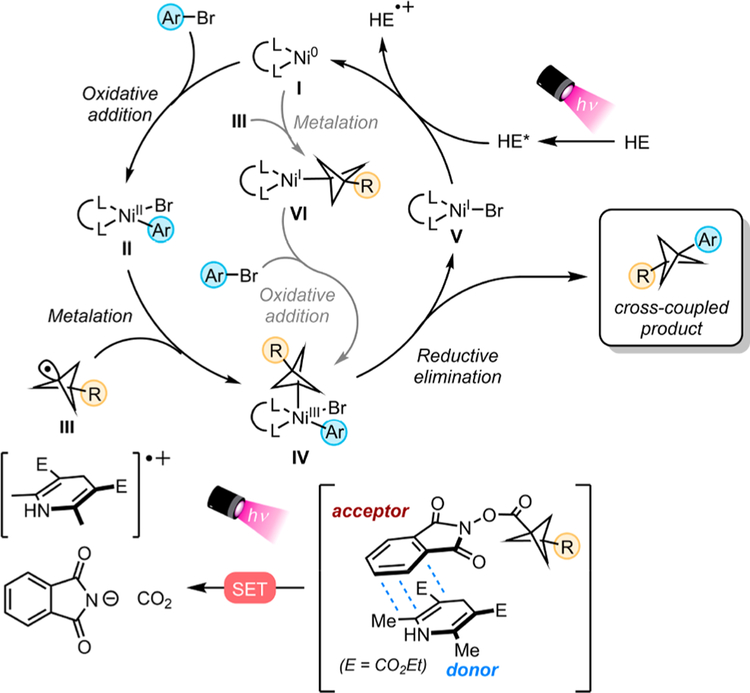

With these results and with insight from our previous report,20 we propose the following mechanism. Visible light excitation of the EDA complex triggers a single-electron transfer (SET) event from HE to the RAE, which fragments to generate phthalimidate, CO2, and BCP radical III. This BCP radical is then captured by NiII oxidative addition complex II. Alternatively, the low-valent Ni0 complex I could intercept BCP radical III and then undergo subsequent oxidative addition with the aryl bromide. Both pathways lead to NiIII intermediate IV, which undergoes reductive elimination to furnish the cross-coupled product. Finally, photoexcited Hantzsch ester reduces NiI to the catalytically active Ni0 species to close the cycle (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Proposed cross-coupling mechanism.

In conclusion, we have established a general route toward the synthesis of functionalized bicyclo[l.1.l]pentanes through Ni-catalyzed C(sp3)–C(sp2) bond formation enabled by photoactive EDA complex activation. The developed cross-electrophile protocol evades the need for expensive transition-metal-based photoredox catalysts, preformed organometallics or boronate partners, and stoichiometric metal reductants. Under this photochemical paradigm, the generation of BCP radicals through direct visible-light excitation followed by subsequent cross-coupling with diverse (hetero)aryl halides is feasible. The commercial availability of carboxylic acids, (hetero)aryl bromides, and HE enables the rapid assembly of diverse scaffolds. In addition, the mild reaction conditions facilitate late-stage modification of drug-like molecules with high functional group tolerance. Key spectroscopic studies highlight the necessity for EDA photoactivation for efficient BCP radical generation and subsequent functionalization.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors are grateful for financial support provided by NIGMS (R35 GM 131680 to Gary A. Molander). Shorouk O. Badir is supported by the Bristol-Myers Squibb Graduate Fellowship for Synthetic Organic Chemistry. The National Science Foundation (NSF) Major Research Instrumentation Program (Award NSF CHE-1827457), the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Supplement Awards 3R01GM118510-03S1 and 3R01GM087605-06S1, and the Vagelos Institute for Energy Science and Technology supported the purchase of the NMRs used in this study. The authors thank Dr. Charles W. Ross, III (UPenn) for mass spectral data. Access to an UV/vis spectrophotometer was provided by the Petersson laboratory (UPenn). The authors thank Kessil for the donation of lamps. AbbVie provided the BCP building blocks and contributed to the design, experiments, and financial support for this research. AbbVie participated in the interpretation of data, writing, reviewing, and approving the publication. The authors thank the following AbbVie employees for their assistance: Dr. Christian Müller, Sven Kercher, and Christian Maiβ from the analytical department in the neuroscience group for HRMS measurements, Dr. Oliver Callies from the NMR facility for technical assistance, and David Geβner from the analytical research and development group for IR measurements.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.orglett.1c01558.

Preparation of starting materials, optimization of cross-coupling and control studies, characterization data for products [nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), infrared (IR), and mass spectrometry (MS)], mechanistic studies, and NMR spectra (PDF)

Complete contact information is available at: https://pubs.acs.org/10.1021/acs.orglett.1c01558

Contributor Information

Viktor C. Polites, Roy and Diana Vagelos Laboratories, Department of Chemistry, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104-6323, United States

Shorouk O. Badir, Roy and Diana Vagelos Laboratories, Department of Chemistry, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104-6323, United States

Sebastian Keess, Medicinal Chemistry Department, Neuroscience Discovery Research, AbbVie Deutschland GmbH & Co. KG, 67061 Ludwigshafen, Germany.

Anais Jolit, Medicinal Chemistry Department, Neuroscience Discovery Research, AbbVie Deutschland GmbH & Co. KG, 67061 Ludwigshafen, Germany.

Gary A. Molander, Roy and Diana Vagelos Laboratories, Department of Chemistry, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104-6323, United States.

REFERENCES

- (1).Schneider N; Lowe DM; Sayle RA; Tarselli MA; Landrum GA Big Data from Pharmaceutical Patents: A Computational Analysis of Medicinal Chemists’ Bread and Butter. J. Med. Chem 2016, 59, 4385–4402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Lovering F; Bikker J; Humblet C Escape from Flatland: Increasing Saturation as an Approach to Improving Clinical Success. J. Med. Chem 2009, 52, 6752–6756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Bauer MR; Di Fruscia P; Lucas SCC; Michaelides IN; Nelson JE; Storer RI; Whitehurst BC Put a ring on it: Application of small aliphatic rings in medicinal chemistry. RSC Med. Chem 2021, 12, 448–471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Kanazawa J; Uchiyama M Recent Advances in the Synthetic Chemistry of Bicyclo[1.1.1]pentane. Synlett 2019, 30, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- (5).Grover N; Senge MO Synthetic Advances in the C-H Activation of Rigid Scaffold Molecules. Synthesis 2020, 52, 3295–3325. [Google Scholar]

- (6).Levin MD; Kaszynski P; Michl J Bicyclo[1.1.1]pentanes, [n]Staffanes, [1.1.1]Propellanes, and Tricyclo[2.1.0.02,5]pentanes. Chem. Rev 2000, 100, 169–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Daniel Rehm JD; Ziemer B; Szeimies G A Facile Route to Bridgehead Disubstituted Bicyclo[1.1.1]pentanes Involving Palladium-Catalyzed Cross-Coupling Reactions. Eur. J. Org. Chem 1999, 1999, 2079–2085. [Google Scholar]

- (8).Messner M; Kozhushkov SI; de Meijere A Nickel- and Palladium-Catalyzed Cross-Coupling Reactions at the Bridgehead of Bicyclo[1.1.1]pentane Derivatives–A Convenient Access to Liquid Crystalline Compounds Containing Bicyclo[1.1.1]pentane Moieties. Eur. J. Org. Chem 2000, 2000, 1137–1155. [Google Scholar]

- (9).Makarov IS; Brocklehurst CE; Karaghiosoff K; Koch G; Knochel P Synthesis of Bicyclo[1.1.1]pentane Bioisosteres of Internal Alkynes and para-Disubstituted Benzenes from [1.1.1]Propellane. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2017, 56, 12774–12777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Kondo M; Kanazawa J; Ichikawa T; Shimokawa T; Nagashima Y; Miyamoto K; Uchiyama M Silaboration of [1.1.1] Propellane: A Storable Feedstock for Bicyclo[1.1.1]pentane Derivatives. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2020, 59, 1970–1974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Shelp R; Ciro A; Pu Y; Merchant RR; Hughes JME; Walsh P Strain-Release 2-Azaallyl Anion Addition/Borylation of [1.1.1] Propellane: Synthesis and Functionalization of Benzylamine Bicyclo[1.1.1]pentyl Boronates. Chem. Sci 2021, 12, 7066–7072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Toriyama F; Cornelia J; Wimmer L; Chen T-G; Dixon DD; Creech G; Baran PS Redox-Active Esters in Fe-Catalyzed C–C Coupling. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2016, 138, 11132–11135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Nugent J; Shire BR; Caputo DFJ; Pickford HD; Nightingale F; Houlsby ITT; Mousseau JJ; Anderson EA Synthesis of All-Carbon Disubstituted Bicyclo[1.1.1]pentanes by Iron-Catalyzed Kumada Cross-Coupling. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2020, 59, 11866–11870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).VanHeyst MD; Qi J; Roecker AJ; Hughes JME; Cheng L; Zhao Z; Yin J Continuous Flow-Enabled Synthesis of Bench-Stable Bicyclo[1.1.1]pentane Trifluoroborate Salts and Their Utilization in Metallaphotoredox Cross-Couplings. Org. Lett 2020, 22, 1648–1654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Fawcett A; Pradeilles J; Wang Y; Mutsuga T; Myers EL; Aggarwal VK Photoinduced decarboxylative borylation of carboxylic acids. Science 2017, 357, 283–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Zuo Z; Ahneman DT; Chu L; Terrett JA; Doyle AG; MacMillan DWC Merging photoredox with nickel catalysis: Coupling of α-carboxyl sp3-carbons with aryl halides. Science 2014, 345, 437–440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Welin ER; Le C; Arias-Rotondo DM; McCusker JK; MacMillan DWC Photosensitized, energy transfer-mediated organometallic catalysis through electronically excited nickel(II). Science 2017, 355, 380–385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Tian L; Till NA; Kudisch B; MacMillan DWC; Scholes GD Transient Absorption Spectroscopy Offers Mechanistic Insights for an Iridium/Nickel-Catalyzed C–O Coupling. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2020, 142, 4555–4559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Niu P; Li J; Zhang Y; Huo C One-Electron Reduction of Redox-Active Esters to Generate Carbon-Centered Radicals. Eur. J. Org. Chem 2020, 2020, 5801–5814. [Google Scholar]

- (20).Kammer LM; Badir SO; Hu R-M; Molander GA Photoactive electron donor–acceptor complex platform for Nimediated C(sp3)–C(sp2) bond formation. Chem. Sci 2021, 12, 5450–5457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Crisenza GEM; Mazzarella D; Melchiorre P Synthetic Methods Driven by the Photoactivity of Electron Donor–Acceptor Complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2020, 142, 5461–5476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Pitre SP; Allred TK; Overman LE Lewis Acid Activation of Fragment-Coupling Reactions of Tertiary Carbon Radicals Promoted by Visible-Light Irradiation of EDA Complexes. Org. Lett 2021, 23, 1103–1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Zheng C; Wang G-Z; Shang R Catalyst-free Decarboxylation and Decarboxylative Giese Additions of Alkyl Carboxylates through Photoactivation of Electron Donor-Acceptor Complex. Adv. Synth. Catal 2019, 361, 4500–4505. [Google Scholar]

- (24).Yang T; Wei Y; Koh MJ Photoinduced Nickel-Catalyzed Deaminative Cross-Electrophile Coupling for C(sp2)–C(sp3) and C(sp3)–C(sp3) Bond Formation. ACS Catal. 2021, 11, 6519–6525. [Google Scholar]

- (25).Zhang J; Li Y; Xu R; Chen Y Donor–Acceptor Complex Enables Alkoxyl Radical Generation for Metal-Free C(sp3)–C(sp3) Cleavage and Allylation/Alkenylation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2017, 56, 12619–12623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Thirumoorthi NT; Jia Shen C; Adsool VA Expedient synthesis of 3-phenylbicyclo[1.1.1]pentan-1 -amine via metal-free homolytic aromatic alkylation of benzene. Chem. Commun 2015, 51, 3139–3142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Kanazawa J; Maeda K; Uchiyama M Radical Multicomponent Carboamination of [1.1.1]Propellane. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2017, 139, 17791–17794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Applequist DE; Renken TL; Wheeler JW Polar substituent effects in 1,3-disubstituted bicyclo[1.1.1]pentanes. J. Org. Chem 1982, 47, 4985–4995. [Google Scholar]

- (29).Kokhan SO; Valter YB; Tymtsunik AV; Komarov IV; Grygorenko OO Bicyclo[1.1.1]pentane-Derived Building Blocks for Click Chemistry. Eur. J. Org. Chem 2017, 2017, 6450–6456. [Google Scholar]

- (30).Adcock JL; Gakh AA Nucleophilic substitution in 1-substituted 3-iodobicyclo[1.1.1]pentanes. A new synthetic route to functionalized bicyclo[1.1.1]pentane derivatives. J. Org. Chem 1992, 57, 6206–6210. [Google Scholar]

- (31).Adcock W; Blokhin AV; Elsey GM; Head NH; Krstic AR; Levin MD; Michl J; Munton J; Pinkhassik E; Robert M; Savéant J-M; Shtarev A; Stibor I Manifestations of Bridgehead–Bridgehead Interactions in the Bicyclo[l.1.l]pentane Ring System. J. Org. Chem 1999, 64, 2618–2625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Benesi HA; Hildebrand JH A Spectrophotometric Investigation of the Interaction of Iodine with Aromatic Hydrocarbons. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1949, 71, 2703–2707. [Google Scholar]

- (33).Renny JS; Tomasevich LL; Tallmadge EH; Collum DB Method of Continuous Variations: Applications of Job Plots to the Study of Molecular Associations in Organometallic Chemistry. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2013, 52, 11998–12013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Walker DK; Jones RM; Nedderman ANR; Wright PA Primary, Secondary and Tertiary Amines and their Isosteres. In Metabolism, Pharmacokinetics and Toxicity of Functional Groups: Impact of Chemical Building Blocks on ADMET; Smith DA, Ed.; Royal Society of Chemistry: London, U.K., 2010; Chapter 4, pp 168–209, DOI: 10.1039/9781849731102-00168. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.