Abstract

Background: Congenital hypothyroidism is often caused by genetic mutations that impair thyroid hormone (TH) production, resulting in growth and development defects. XB130 (actin filament associated protein 1 like 2) is an adaptor/scaffold protein that plays important roles in cell proliferation, migration, intracellular signal transduction, and tumorigenesis. It is highly expressed in thyrocytes, however, its function in the thyroid remains largely unexplored.

Methods: Xb130−/− mice and their littermates were studied. Postnatal growth and growth hormone levels were measured, and responses to low or high-iodine diet, and levothyroxine treatment were examined. TH and thyrotropin in the serum and TH in the thyroid glands were quantified. Structure and function of thyrocytes in embryos and postnatal life were studied with histology, immunohistochemistry, immunofluorescence staining, Western blotting, and quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction.

Results: Xb130−/− mice exhibited transient growth retardation postnatally, due to congenital hypothyroidism with reduced TH synthesis and secretion, which could be rescued by exogenous thyroxine supplementation. The thyroid glands of Xb130−/− mice displayed diminished thyroglobulin iodination and release at both embryonic and early postnatal stages. XB130 was found mainly on the apical membrane of thyroid follicles. Thyroid glands of embryonic and postnatal Xb130−/− mice exhibited disorganized apical membrane structure, delayed folliculogenesis, and abnormal formation of thyroid follicle lumina.

Conclusion: XB130 critically regulates folliculogenesis by maintaining apical membrane structure and function of thyrocytes, and its deficiency leads to congenital hypothyroidism.

Keywords: adaptor protein, cell polarity, congenital hypothyroidism, folliculogenesis, thyroglobulin release and iodination, thyroid hormone synthesis and secretion

Introduction

Congenital hypothyroidism (CH) is a condition in which the thyroid gland produces insufficient thyroid hormone (TH) to meet the body's needs (1). Mutations in genes that control the development of the thyroid gland or encode the cellular machinery for TH synthesis can underlie this disorder (2–4). Proteins encoded by these genes are located properly in the basal or apical membranes of thyrocytes. Disruption of thyrocyte polarization leads to various thyroid disorders (5,6). Adaptor proteins are involved in polarized sorting in the cell (7). With multiple protein–protein and protein–lipid interaction domains and motifs, such adaptor proteins contribute to cytoskeletal architecture, regulating cell polarity. For example, Na+/I− symporter (NIS) is a glycoprotein expressed at the basolateral plasma membrane of thyrocytes that mediates iodine accumulation for thyroid hormonogenesis. A epithelial-specific clathrin adaptor protein AP-1B is required for NIS basolateral sorting (8). Another adaptor protein, kinesin light chain 2, is involved in NIS export from the endoplasmic reticulum and further transport to the plasma membrane (9).

XB130 (actin filament associated protein 1 like 2, AFAP1L2) is an adaptor protein predominantly expressed in the thyroid gland (10,11). XB130 has been postulated to cross-link actin filaments (12) and is engaged in polarized cell migration through its interactions with other cytoskeletal proteins (13,14). In this study, we observed transient postnatal growth retardation of XB130 knockout (Xb130−/−) mice due to CH. Further investigations uncovered delayed thyroid folliculogenesis with defects in thyrocyte polarization accompanied by disorganization of apical structure and function.

Methods

These are provided in an abriged form. Details can be found in Supplementary Data.

Animals

Xb130−/− mice were generated as described previously (15). Animal use and care committee of the University Health Network approved all procedures.

Growth measurement

Body weight (BW) of mice were measured daily or weekly. Absolute and specific growth rates at day N are calculated by WN − WN − 1 and (WN − WN − 1)/WN − 1, respectively (16,17).

Blood and tissue collection and histological studies

Blood and tissues were collected. Breeding pairs of Xb130+/− mice were set up for timed pregnancy for embryos collection. Tissue slides were used for H&E staining. Frozen tissue sections were stored at −80°C until use.

Tests of serum TH and thyrotropin levels and thyroidal THs

Measurements of serum thyrotropin (TSH), thyroxine (T4), and triiodothyronine (T3), and thyroidal T4 and T3 concentrations in tissue extracts were described previously (18,19).

Levothyroxine administration

Levothyroxine (L-T4) (40 or 120 ng/g BW) was injected daily to postnatal day (PD)5 mice, and BW was measured daily until PD28. Thereafter, these mice were fed with L-T4 (0.26 or 0.78 mg/L) in drinking water until postnatal week (PW)14.

125I uptake and perchlorate discharge tests

Mice at PW3 and PW10–12 were fed with low iodine diet (LID) for 2 weeks. 125I (8 μCi/mouse; 1.7 × 107 cpm) was given to mice by intraperitoneal injection. For the perchlorate-induced iodide-discharge test, KClO4 (10 μg/g BW) was injected intraperitoneally 4 hours after 125I administration. The amount of radioactivity in blood samples and excised thyroid glands was measured with a γ-scintillation counter.

High-iodine diet treatment

Dams fed with normal chow were given on the day after delivery 10 mg/L NaI in the drinking wather, and high-iodine diet (HID) continued to the litter until PW14 (20).

Transmission electron microscopy

Thyroid glands were studied with standard transmission electron microscopy.

Immunoblotting

Quantitative reverse transcription polymerse chain reaction

Quantitative reverse transcription polymerse chain reaction (PCR) was performed following standard protocols.

Immunohistochemistry and immunofluorescence studies

Standard immunohistochemistry staining and immunofluorescence (IF) staining protocols were followed.

Statistical analysis

Unless indicated otherwise, statistical analysis was performed using unpaired two-tailed Student's t-test, or one-way analysis of variance, with GraphPad Prism 8.0 (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA). Comparison of percentage of incidence was performed using chi-square test. Data presented are as means ± standard error of the mean. p < 0.05 is considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Transient postnatal growth retardation in Xb130−/− mice caused by CH

In comparison with Xb130+/+ littermates, Xb130−/− mice have a normal appearance and life span, a genotype ratio consistent with expected single-locus Mendelian inheritance, and do not have an obvious phenotype in a series of physiological assessments (15). However, we serendipitously noted smaller mice around PW3, linked to the Xb130−/− genotype (Fig. 1A). The BW of Xb130−/− mice started to catch up around PW7–8, ultimately leading to near-complete recovery by PW12–14 (Fig. 1B).

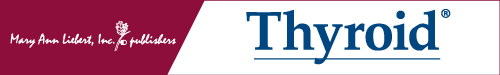

FIG. 1.

Transient growth retardation of Xb130−/− mice and congenital hypothyroidism. (A) Body size of Xb130−/− mice and age-matched Xb130+/+ mice at PW3 and PW7. (B) BW of Xb130+/+ (M = 16, F = 22), Xb130+/− (M = 45, F = 31), and Xb130−/− (M = 16, F = 16) mice measured weekly from PW1 to PW12. (C–E) BW of Xb130+/+ (M = 66, F = 74) and Xb130−/− mice (M = 53, F = 62) was measured daily. Green lines frame the growth phases. (C) BW of Xb130−/− mice relative to that of Xb130+/+ mice. (D) Absolute growth rate (WN − WN − 1). (E) Specific growth rate ((WN − WN − 1)/WN − 1). (F) Organ weight of Xb130+/+ and Xb130−/− mice at PW2–3 and PW24 (n = 10–20 mice in each group). Data are mean ± SEM, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. BW, body weight; F, female; M, male; PW, postnatal week. Color images are available online.

Postnatal growth of mice has three phases, each regulated by different growth factors and hormones. Up to the 14th postnatal day (PD), corresponding to growth phase I, mainly regulated by insulin-like growth factor 1 (16,17), BW and specific growth rate of Xb130−/− mice are indistinguishable from those of Xb130+/+ littermates. Delayed growth was observed in phase II (PD15–PD28), which was followed by a gradual recovery until PD42. The growth rates of Xb130−/− mice in phase III were comparable with those of Xb130+/+ mice (Fig. 1C–E). Phase II of mouse growth is mainly controlled by growth hormone (Gh) (16,17,21). Indeed, the pituitary of Xb130−/− mice at PD14 exhibited a drastic reduction of Gh immunostaining (Supplementary Fig. S1A) and protein levels (Supplementary Fig. S1B), which were partially recovered by PD28 and fully recovered at PW14 (Supplementary Fig. S1B). The pituitary of Xb130−/− mice exhibited hypertrophy of thyrotropes at PD14 (Supplementary Fig. S1C) and an expansion of TSH-positive cells at PD28 (Supplementary Fig. S1D).

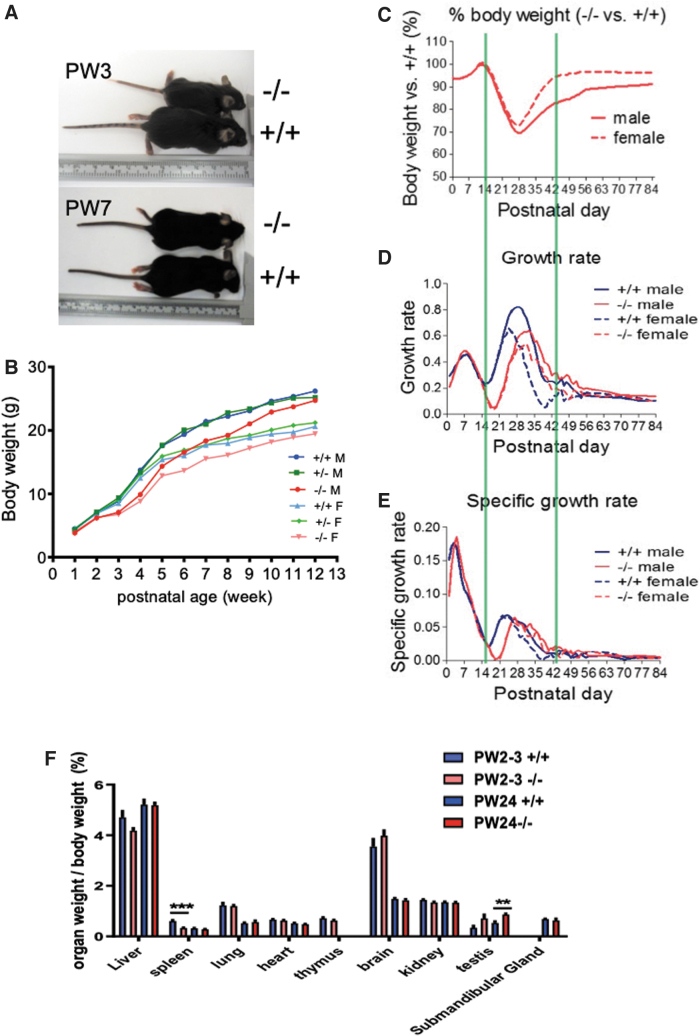

The production of Gh in the pituitary is effectively regulated by TH (16,17,22,23). While weights of most other organs are comparable with those of Xb130+/+ mice (Fig. 1F), the thyroid glands of Xb130−/− mice became significantly heavier and enlarged with age (Fig. 2A). The enlarged thyroid glands contained a high ratio of proliferating cells (Fig. 2B). Thyroid follicles of Xb130−/− mice became significantly enlarged at PW4 and PW14 (Fig. 2C). At PW2 and PW4, the average size of thyrocytes remained similar (Fig. 2D—i), and the number of cells per follicle was slightly increased (Fig. 2D—ii). The whole follicle area and colloid containing area were significantly increased (Fig. 2D—iii–iv). At PW4, follicle perimeter was significantly increased, with thyrocyte thickness dramatically reduced (Fig. 2D—v–vi).

FIG. 2.

Thyroid gland hyperplasia and morphological changes in Xb130−/− mice. (A) Weight of thyroid glands of Xb130−/− mice at different ages. The number of Xb130+/+ thyroid glands at PW3, PW4, and PW24 was 17, 8, and 7, respectively. The number of Xb130−/− thyroid glands at PW3, PW4, and PW24 was 14, 5, and 7, respectively. (B) Ki67+ staining in thyroid gland section at both PW2 and PW14 (n = 3 mice in each group). (C) Representative H&E staining of thyroid gland at different ages. (D) The morphological characterization of thyroid gland sections at PW2 and PW4. All data are expressed relative to Xb130+/+ mice at PW2 except v and vi. More than 400 follicles were measured for each group (n = 3–5 mice/group). Data are mean ± SEM, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. Color images are available online.

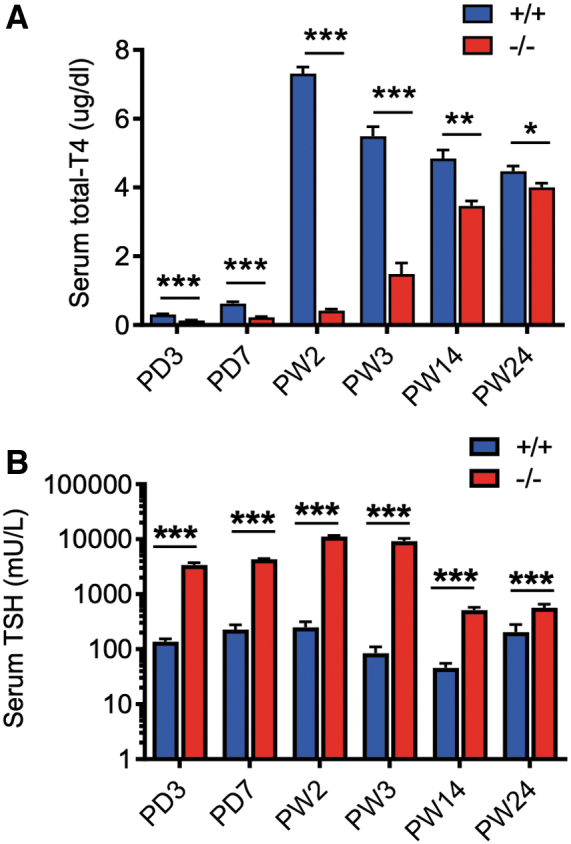

The enlargement of thyroid follicles promoted us to further study the TH levels in serum. The serum T4 level of Xb130+/+ was 0.3 μg/dL at PD3 and reached a peak of ∼7.31 μg/dL at PW2, followed by a gradual decline to a steady level (∼4.78 μg/dL) at PW14–24 (Fig. 3A). In contrast, Xb130−/− littermates exhibited significantly lower levels of serum T4 at PD3–PW2 (0.13–0.41 μg/dL). Although the serum T4 level of Xb130−/− mice increased gradually, it remained significantly lower than that of Xb130+/+ littermates even at PW24 (4.0 ± 0.12 μg/dL vs. 4.47 ± 0.15 μg/dL, p < 0.05). Serum T3 concentration was also significantly reduced in Xb130−/− mice relative to Xb130+/+ littermates at PW2 (21.5 ± 3.2 ng/dL vs. 39.0 ± 5.8 ng/dL; p < 0.03) but normalized at PW14 (46.7 ± 7.6 ng/dL vs. 40.3 ± 5.4 ng/dL). Notably high levels of serum TSH were observed in Xb130−/− mice in early PDs, especially around PW2 (>40-fold). Despite a gradual decrease over time, serum TSH level in Xb130−/− mice remained significantly above that of Xb130+/+ mice, even at PW24 (more than twofold; Fig. 3B). Taken together, Xb130−/− mice show primary hypothyroidism with a compensatory increase in the production of TSH, which promotes growth of the thyroid gland to increase production of TH.

FIG. 3.

Reduced serum T4 and elevated TSH in Xb130−/− mice. (A) Serum T4 levels at different development stages. The number of Xb130+/+ mice (n = 8, 9, 8, 7, 8, 11) and Xb130−/− mice (n = 9, 9, 8, 7, 8, 8) at PD3, PD7, PW2, PW3, PW14, and PW24 is given in the brackets. (B) Serum TSH levels at different development stages. The number of Xb130+/+ mice (n = 8, 9, 9, 8, 9, 19) and Xb130−/− mice (n = 9, 9, 9, 9, 9, 9) at PD3, PD7, PW2, PW3, PW14, and PW24 is given in the brackets. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. T4, thyroxine; TSH, thyrotropin; PD, postnatal day. Color images are available online.

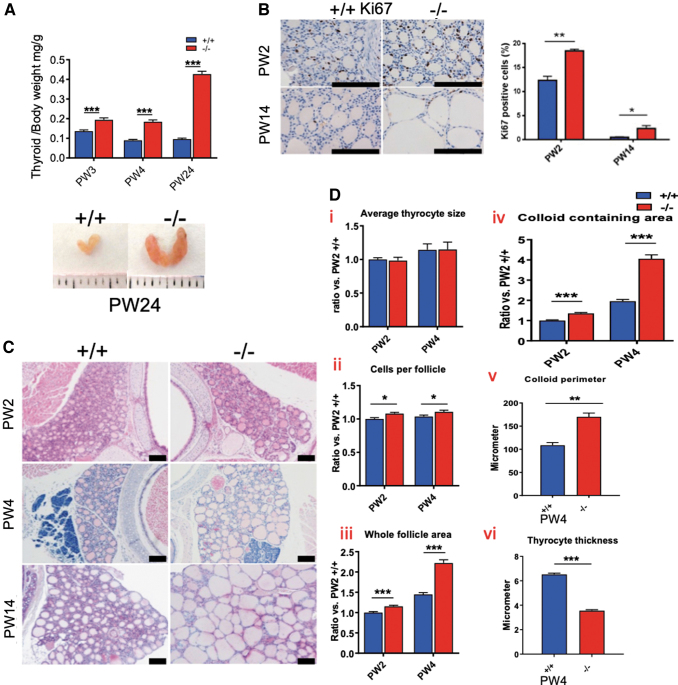

To prove that reduced expression of Gh in the pituitary and transient growth retardation of Xb130−/− mice are caused by low levels of TH, we treated mice with physiological or a high dose of L-T4 subcutaneously (40 or 120 ng/g BW/day), starting at PD5. L-T4 treatments reduced serum TSH levels in both genotypes to <10 mU/L (Fig. 4A). Interestingly, serum T4 level at PW2 was significantly higher in Xb130−/− mice given daily 40 ng/g L-T4 compared with Xb130+/+ mice treated similarly. In mice treated with 120 ng/g L-T4, serum T4 levels were elevated in both groups (Fig. 4B), suggesting a limited capacity for mice to process exogenous L-T4, which is further reduced in Xb130−/− mice. Notably, L-T4 treatment not only increased Gh production in the pituitary of Xb130−/− mice at PW2 (Fig. 4C) but also completely prevented the growth retardation (Fig. 4D). Moreover, L-T4 treatment up to PW14 prevented the enlargement of thyroid follicles in Xb130−/− mice, and high dose of L-T4 induced atrophy of thyroid glands (Fig. 4E). Therefore, the transient impairment of Gh production and growth retardation in Xb130−/− mice are caused by CH.

FIG. 4.

L-T4 treatment rescues transient growth retardation in Xb130−/− mice, and HID does not rescue hypothyroidism. (A–E) Mice were injected subcutaneously with LT4 (40 ng/g, 120 ng/g BW) or vehicle daily starting from PD5. (A) Blood serum TSH at PD14 (n = 4, 3, 6, 3, 6, 5). (B) Blood serum T4 at PD14 (n = 4, 3, 6, 3, 3, 5). (C) Western blot of growth hormone in pituitary at PD14 (n = 4 mice in each group). (D) Growth curve of control and LT4-treated mice from PD15 to PD21 (n = 5–10 mice in each group). (E) Representative images of H&E of thyroid gland section of control and treated groups at PW14 (n = 3–4 in each group). (F–H) HID was given to mice from birth until PW14 to test whether it can rescue the thyroid function and morphology of Xb130−/− mice. (F) Serum T4 levels at PW14 (n = 6–8 mice in each group). (G) Serum TSH levels at PW14 (n = 5–8 mice in each group). (H) H&E of thyroid gland section of control and HID-treated groups at PW14. Representative images from 4 to 5 mice of each group. Data are mean ± SEM, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. HID, high-iodine diet; LT4, levothyroxine. Color images are available online.

Defective TH synthesis, secretion, and impaired iodide organification in the thyroid gland of Xb130−/− mice

At PW14, enlarged thyroid glands in Xb130−/− mice have a high quantity of total protein (Fig. 5A); thus the levels of TH in thyroid tissue are expressed per thyroid and per mg protein. At PW2, all TH levels (except Tg [thyroglobulin]-bound T3/mg protein) were significantly lower in Xb130−/− mice (Fig. 5B–E), suggesting impaired thyroidal TH synthesis. By contrast, at PW14, all TH levels (except Tg-bound T4 and Tg-bound T3/mg protein) were significantly higher than those of age-matched Xb130+/+ mice (Fig. 5B–E), indicating compensatory thyroidal TH synthesis. Since the serum T4 level was significantly lower in PW14 Xb130−/− mice (Fig. 3A), the higher levels of thyroidal TH indicates impaired secretion of TH from the thyroid gland to the circulation. Monocarboxylate transporter 8 (MCT8) is localized at the basolateral membrane of thyrocytes, and is involved in the secretion of TH from the thyroid gland (18). We found that the mRNA and protein levels of MCT8 in the thyroid glands were decreased in Xb130−/− mice (Supplementary Fig. S2). This may be relevant to the impaired secretion of TH.

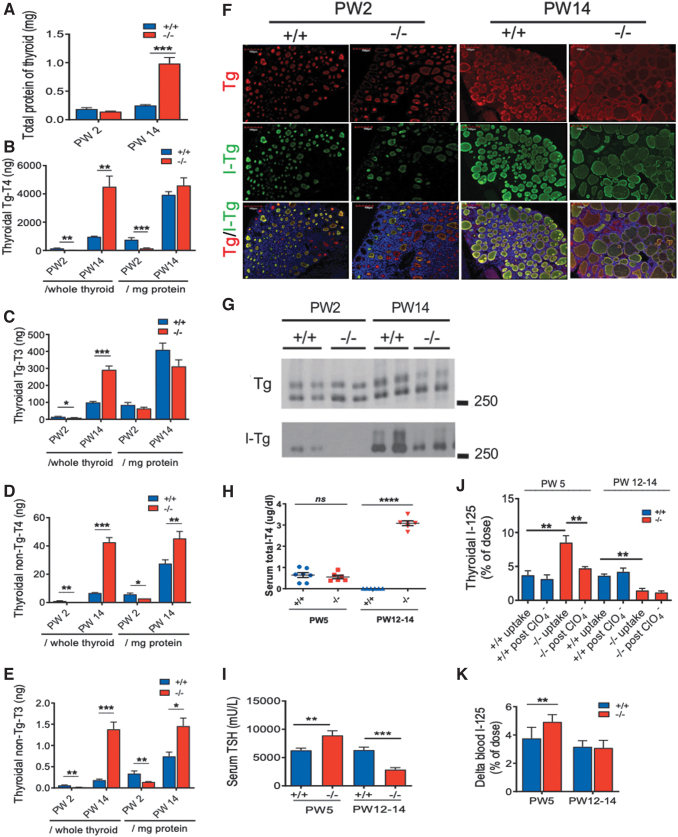

FIG. 5.

Defective TH synthesis (PW2), impaired TH secretion (PW14), lower Tg iodination (PW2, PW14), and defective I− organification (PW5) in Xb130−/− mice. (A) Total protein content per thyroid gland. (B–E) Intrathyroidal TH levels at PW2 and PW14 (n = 6 for each genotype at each age), presented as per thyroid and per mg protein, respectively. (B) Tg bound-T4. (C) Tg bound-T3. (D) non-Tg bound-T4. (E) non-Tg bound-T3. (F) IF staining of Tg and I-Tg in thyroid glands at PW2 and PW14 shows reduced I-Tg in Xb130−/− thyroid glands (n = 4–6 mice from each group). (G) Western blotting of thyroid gland lysate using anti-Tg or anti-I-Tg antibody. Each sample presents an independent pool from 4 to 5 mice. (H–K) Thyroidal 125I uptake and perchlorate discharge test. Mice at PW3 and PW10–12 were fed with low-iodide diet for 2 weeks. Serum samples were collected to measure T4 and TSH levels. The next day, 125I was given to mice by intraperitoneal injection. Four hours after 125I injection, some mice were sacrificed, and thyroid glands were dissected immediately to determine the 125I uptake. For the rest, KClO4 was injected intraperitoneally, and thyroid glands and blood samples were collected 20 minutes later for 125I activity measurement. (H) Serum total T4 levels (n = 7, 6, 6, 6). (I) Serum TSH levels (n = 7, 6, 6, 6). (J) Thyroidal 125I before and after KClO4 administration (n = 5, 6, 7, 7, 5, 8, 3, 5). Increased thyroidal 125I uptake and increased perchlorate discharge were seen in Xb130−/− thyroid glands at PW5. (K) 125I activity in the blood (n = 6, 7, 8, 5). Data are presented as mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001. I-Tg, iodinated Tg; IF, immunofluorescent; T3, triiodothyronine; Tg, thyroglobulin; TH, thyroid hormone. Color images are available online.

Iodination of Tg is an essential step in thyroidal TH synthesis. Thyroid follicles in Xb130−/− mice at PW2 and PW14 exhibited a lower concentration of iodinated Tg (I-Tg) relative to the abundance of total Tg (Fig. 5F). Consistently, Western blot of thyroid tissue lysate revealed less iodination of Tg at PW2, which was partially recovered at PW14 (Fig. 5G).

To determine whether decreased iodination of Tg in Xb130−/− mice is due to defect of I- uptake or organification, mice at PW3 or PW10–12 were fed LID for 2 weeks, and then injected with 125I to determine its uptake, followed by administration of KClO4, a compound that results in a discharge of unorganified 125I from thyroid into the blood. At PW5, LID treatment reduced serum T4 levels in both Xb130+/+ and Xb130−/− mice to <1 μg/dL (Fig. 5H). This was associated with significantly increased serum TSH levels in Xb130+/+ mice, which, however, was still significantly lower than TSH levels in Xb130−/− mice (Fig. 5I). The uptake of 125I in thyroid glands of Xb130−/− mice was significantly higher than that of Xb130+/+ mice, and KClO4 administration significantly reduced 125I content in thyroid glands (Fig. 5J) with an increase of 125I in the blood (Fig. 5K). Thus, iodide organification but not iodide uptake is impaired in Xb130−/− mice.

At PW14, LID treatment reduced serum T4 to undetectable levels in Xb130+/+ mice but had little effects in Xb130−/− mice (Fig. 5H). As the thyroidal THs were significantly higher at PW14 (Fig. 5B–E), the two weeks of LID in adult Xb130−/− mice was insufficient to deplete T4 stored in the thyroid glands. As a consequence, serum TSH levels were significantly lower in Xb130−/− mice (Fig. 5I), and uptake of 125I in thyroid glands was significantly reduced, and KClO4 had no effect on 125I content in thyroid glands (Fig. 5J, K).

HID administration forestalled severe hypothyroidism in NIS knockout mice (20). Administration of HID to Xb130−/− mice, however, did not correct the impaired serum T4 or TSH levels (Fig. 4F, G) nor the enlarged follicle morphology (Fig. 4H), further supporting that the decreased iodination of Tg in Xb130−/− mice is not due to a defect of I- uptake.

Quantitative RT-PCR (qPCR) of RNA extracted from thyroid glands collected from mice at PW2, PW4 and PW14 revealed upregulated expression of TH synthesis-related genes, including Tshr, Nis, Pds, Tpo, Duox1, Duox2, DuoxA1, and DuoxA2 (Supplementary Fig. S3) in Xb130−/− mice, suggesting a normal gene expression response to TSH stimulation in hypothyroidism. A thyroid-specific enhancer-binding protein, Nkx2.1, is required for maintenance of the normal architecture and function of differentiated thyroids (24). Another thyroid transcription factor, Pax8, controls follicular polarization and follicle formation through its target cadherin-16 in three-dimensional cultured thyrocytes (25). The mRNA levels of these genes were not significantly changed in Xb130−/− mice.

Impaired Tg release and iodination in Xb130−/− mice at the embryonic stage

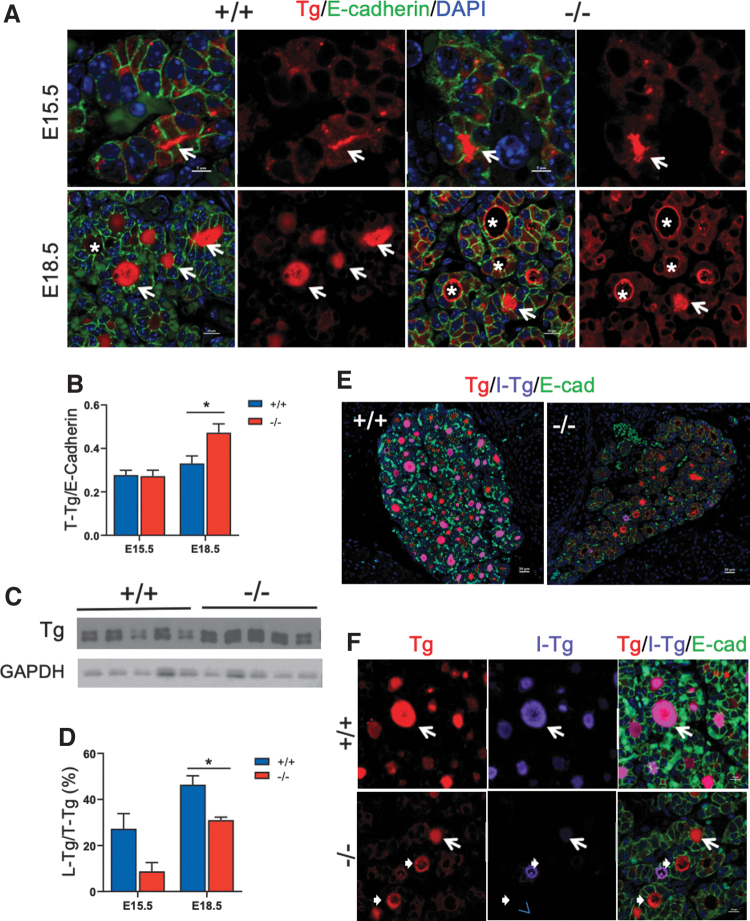

To determine whether the reduced iodination of Tg is based on a developmental defect, we examined Tg expression in embryonic thyroid glands. Immunoreactivity of Tg was detected in the follicular lumen as early as day 15.5 embryos (E15.5; Fig. 6A), with comparable levels in both Xb130+/+ and Xb130−/− embryos (Fig. 6A, B). In E18.5 Xb130+/+ embryos, Tg was located mainly in the follicular lumen, whereas in Xb130−/− embryos, Tg was primarily associated with the apical membrane of follicles or in the cytoplasm of thyrocytes (Fig. 6A), suggesting impaired release of Tg into the follicular lumen. IF staining and immunoblot assay confirmed higher levels of Tg protein in the thyroid gland of Xb130−/− embryos at E18.5 (Fig. 6B, C). In Xb130+/+ embryos, I-Tg is concentrated in Tg-filled follicular lumina, whereas in Xb130−/− embryos, follicular lumina contained markedly less I-Tg (Fig. 6D–F).

FIG. 6.

The absence of Xb130 causes the reduced release of Tg to follicular lumen and impaired Tg iodination in thyroid glands of embryos. (A) IF staining of Tg in thyroid glands at E15.5 and E18.5. Arrows indicate follicle lumens filled with Tg; asterisks indicate follicles with Tg enriched in cytoplasm and at the apical membrane. (B) The expression of total Tg in thyroid gland was quantified by the IF intensity of Tg normalized with the IF intensity of E-cadherin (N = 8, 4, 12, 8). (C) Western blot of protein lysate from E18.5 thyroid glands of Xb130+/+ and Xb130−/− littermate mice showed increased expression of Tg in Xb130−/− mice. Each lane represents a single embryo. (D) The ratio of L-Tg versus T-Tg, quantified by the measurement of Tg IF intensity in the lumen versus in the total thyroid section (N = 8, 4, 12, 8). (E, F) Representative IF double staining of Tg and I-Tg in thyroid glands at E18.5 (n = 7 of Xb130+/+ and n = 4 Xb130−/− thyroid glands, respectively). (E) Low magnification. (F) High magnification. Arrows show I-Tg staining in the follicle lumen, arrowheads show lack of I-Tg staining in the lumen in Xb130−/− mice. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05. L-Tg, lumen Tg; T-Tg, total Tg. Color images are available online.

Impaired apical structure of thyroid follicles and delayed folliculogenesis in Xb130−/− mice

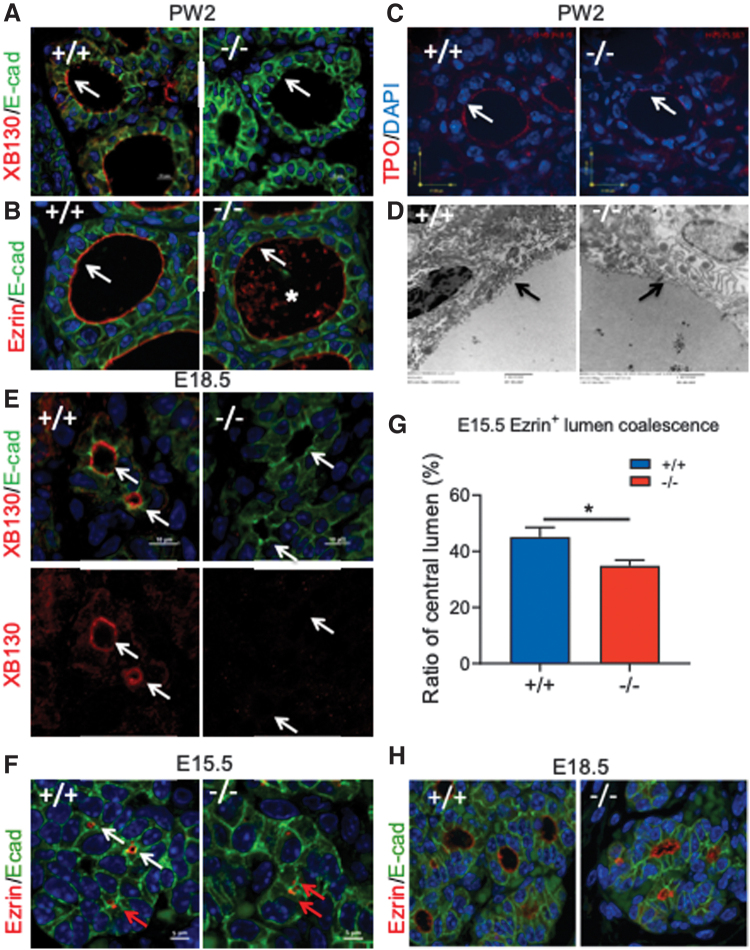

At PW2, XB130 is mainly located at the apical membrane of thyrocytes of Xb130+/+ mice (Fig. 7A). As an actin filament associated protein involved in the cytoskeletal organization (14,26), XB130 may be involved in the regulation of apical structure assembly and function. Ezrin is a peripheral membrane protein that functions as a linker between plasma membrane lipids and the actin cytoskeleton and helps to maintain the apical structure of polarized cells (27,28). Ezrin abundantly lines the apical face of thyroid follicles in Xb130+/+ mice (Fig. 7B). By contrast, ezrin was faintly and less distinctly localized at the apical membrane of Xb130−/− thyrocytes, with staining patches in the follicular lumen (Fig. 7B). Zonula Occludens-1 (at the tight junction) and platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 (at the basal membrane) were expressed similarly in both Xb130+/+ and Xb130−/− follicles (Supplementary Fig. S4A).

FIG. 7.

Xb130−/− thyroid glands have impaired follicle apical membrane structure and delayed embryonic folliculogenesis. (A–D) Representative thyroid glands of Xb130+/+ and Xb130−/− mice at PW2 (n = 4 in each group). (A) IF staining of XB130/E-cadherin. XB130 is located mainly on apical membrane in Xb130+/+ thyroid gland. (B) Ezrin/E-cadherin. Ezrin staining is reduced at apical membrane in Xb130−/− thyroid gland. Asterisk shows debris in the lumen. (C) Reduced TPO staining is shown at apical membrane of Xb130−/− thyroid glands. (D) Representative images of TEM. Black arrows show apical membrane; lack of microvilli is noted in the Xb130−/− thyroid gland. (E) IF staining of XB130 in E18.5 embryo thyroid glands. Arrows show apical membrane of lumen. (F) IF staining of ezrin on thyroid gland sections at E15.5 (white arrow: central lumen; red arrow: intracellular lumen, determined by Z-stack confocal microscopy). (G) Ezrin+ intracellular lumen and central lumen were counted and the ratio of the number of central lumens versus total number of lumens was quantified (N = 8 of Xb130+/+ and n = 6 of Xb130−/− thyroid glands). (H) IF staining of ezrin at E18.5 (n = 8 in Xb130+/+ group and n = 4 in Xb130−/− group). Data are presented as mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05. TEM, transmission electron microscopy; TPO, thyroid peroxidase. Color images are available online.

A proper apical membrane structure of thyroid follicles is crucial for TH synthesis. While some apically localized proteins, such as pendrin (Supplementary Fig. S4A), showed similar staining on apical membrane of follicles in both genotypes, apical staining of Tpo was diminished in Xb130−/− thyroid glands (Fig. 7C). Moreover, transmission electron microscopy (TEM) showed a reduced number of apical microvilli in Xb130−/− thyroid glands (Fig. 7D). Thus, XB130 deficiency results in disorganization of the apical structure of thyrocytes.

In E18.5 embryos, XB130 is seen on the apical membrane of the follicular lumen in Xb130+/+ thyroid glands (Fig. 7E). Ezrin is seen on the surface of the central lumen (Fig. 7F, white arrow), or as doublets between two adjacent cells (Fig. 7F, red arrow) at E15.5 in Xb130+/+ thyroid glands. Z-stack confocal microscopy demonstrated these doublets as intracellular lumina. The number of ezrin-stained central lumina is significantly less in E15.5 Xb130−/− thyroid glands (Fig. 7G). E18.5 Xb130−/− thyroid follicles are misshapen, with irregular follicle lumina (Fig. 7H). At PW2, intracellular lumina in Xb130−/− thyrocytes are visible by TEM (Supplementary Fig. S4B) or by IF staining (Supplementary Fig. S4C), but hardly in Xb130+/+ thyrocytes, indicating impairment of thyroidal folliculogenesis in Xb130−/− mice.

Discussion

In this study, we observed a transient growth retardation in phase II growth of Xb130−/− mice due to reduced Gh, which could be rescued by administration of exogenous TH. Activation of the TSH upregulates expression of genes essential for TH production and stimulates compensatory thyroid gland growth. However, the serum TH levels remain lower in Xb130−/− mice with higher levels of TSH. In a separate study, we observed the development of multinodular goiter in elderly Xb130−/− mice (article in preparation). Therefore, the CH caused by XB130 deficiency persists throughout life.

Defective gene expression/function related to thyroid gland development (e.g., Nkx2.1) (24), or TH production (e.g., MCT8, NIS, DUOXAs) (9,18,20,29) results in CH in humans or mice. Compared with these animals, Xb130−/− mice showed multiple defects in the synthesis pathway. The hypothyroidism in Xb130−/− mice resulted from both reduced TH production and secretion. Further investigation showed reduced I− organification, iodination of Tg, release of Tg to follicle lumen, and accumulation of serum T4 after exogenous LT4 administration.

As an adaptor protein, XB130 contains an actin-binding domain, several Src homology 2 domain and Src homology 3 domain binding motifs, two pleckstrin homology domains, as well as a coiled-coil region, for interaction with its binding partners. Through these structures, XB130 interacts with cytoplasmic membranes and membrane-associated proteins (30,31). Using yeast-two-hybrid system, we have identified multiple potential binding partners for XB130 (32). The lack of XB130 may affect the function of multiple binding partners.

However, protein sorting and intracellular transport from the cytoplasm to the apical membrane are essential for the function of thyrocytes (33). In the absence of XB130, microvilli are reduced on the apical membrane of follicles and apical ezrin is reduced in postnatal thyroid follicles, suggesting changes of apical membrane structure of thyrocytes. Tpo, an essential enzyme for Tg iodination, is reduced on the apical membrane in the thyrocytes of Xb130−/− mice, which may contribute to the reduced iodide organification, Tg release, and iodination, suggesting an essential role of XB130 in the control of thyroid apical membrane structure and function.

The lack of XB130 during embryonic development slows down thyroid folliculogenesis. The fusion from intracellular lumina to a central lumen is delayed, persisting into the postnatal period. The reduced Tg release and iodination was observed in embryonic thyroid glands. All of these defects point to a disorganized apical membrane structure and function. Polarization of subcellular compartments is a distinctive characteristic of epithelial cells and maintainence of apical-basal orientation is crucial for tissue integrity and function of these cells. The role of XB130 in the regulation of cellular polarity and function is the focus of our current studies.

CH due to thyroid dyshormonogenesis could be caused by defects in any of the known steps in the TH biosynthesis pathway (2). Our finding indicates that the defects of an adaptor protein, or proteins that may not be directly involved in thyroid hormonogenesis could also lead to thyroid dyshormonogenesis, and emphasizes the importance of structural integrity of the thyrocytres and the follicles. This observation opens a door to explore new genetic defects in the pathogenesis of CH.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Jinbo Zhao, Deborah Scollard, Dr. Susan Newbigging, Lucy Andrighetti, and Dr. Zhihong Guan for their technical help. We also thank Dr. Xavier De Deken and Dr. Carrie Ris-Stalpers for providing antibodies and advices.

Authors' Contributions

M.L. and Y.W. designed the project and wrote the article. Y.W. participated in most of the experiments. H.S. designed and performed thyroid functional studies. Y.-Y.X. participated in immunofluorescence studies. H.T. and H.-R.C. participated in the growth studies. H.S. and H.-R.C. participated in studies related to hypothyroidism. X.-H.B. performed RT-qPCR. X.-H.L. performed serum and thyroid gland T4 and T3 determinations and serum TSH measurements. J.S. and X.-H.L.helped to prepare and edit the article. S.R., P.A., S.L.A., and W.-Y.L. provided conceptual advice, planned some of the experiments, and edited the article. All coauthors have approved the article for submission.

Authors Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Funding Information

This research was supported by grants from Canadian Institutes of Health Research (MOP-31227, MOP-42546, MOP-119514 to M.L.) and from The National Institutes of Health, DK15070 (to S.R.) and DK40344 (to P.A.). M.L. is James and Mary Davie Chair in Lung Injury, Repair and Regeneration.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Wassner AJ 2018. Congenital hypothyroidism. Clin Perinatol 45:1–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Grasberger H, Refetoff S. 2011. Genetic causes of congenital hypothyroidism due to dyshormonogenesis. Curr Opin Pediatr 23:421–428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Nascimento AC, Guedes DR, Santos CS, et al. 2003. Thyroperoxidase gene mutations in congenital goitrous hypothyroidism with total and partial iodide organification defect. Thyroid 13:1145–1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rigutto S, Hoste C, Grasberger H, et al. 2009. Activation of dual oxidases Duox1 and Duox2: differential regulation mediated by camp-dependent protein kinase and protein kinase C-dependent phosphorylation. J Biol Chem 284:6725–6734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. D'Amico E, Gayral S, Massart C, et al. 2013. Thyroid-specific inactivation of KIF3A alters the TSH signaling pathway and leads to hypothyroidism. J Mol Endocrinol 50:375–387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Villacorte M, Delmarcelle AS, Lernoux M, et al. 2016. Thyroid follicle development requires Smad1/5- and endothelial cell-dependent basement membrane assembly. Development 143:1958–1970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bonifacino JS 2014. Adaptor proteins involved in polarized sorting. J Cell Biol 204:7–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Martin M, Modenutti CP, Peyret V, et al. 2019. A carboxy-terminal monoleucine-based motif participates in the basolateral targeting of the Na+/I- symporter. Endocrinology 160:156–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Martin M, Modenutti CP, Gil Rosas ML, et al. 2021. A novel SLC5A5 variant reveals the crucial role of kinesin light chain 2 in thyroid hormonogenesis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 106:1867–1881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Xu J, Bai XH, Lodyga M, et al. 2007. XB130, a novel adaptor protein for signal transduction. J Biol Chem 282:16401–16412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lodyga M, De Falco V, Bai XH, et al. 2009. XB130, a tissue-specific adaptor protein that couples the RET/PTC oncogenic kinase to PI 3-kinase pathway. Oncogene 28:937–949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Yamanaka D, Akama T, Chida K, et al. 2016. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-associated protein (PI3KAP)/XB130 crosslinks actin filaments through its actin binding and multimerization properties in vitro and enhances endocytosis in HEK293 cells. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 7:89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wu Q, Nadesalingam J, Moodley S, et al. 2015. XB130 translocation to microfilamentous structures mediates NNK-induced migration of human bronchial epithelial cells. Oncotarget 6:18050–18065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Moodley S, Derouet M, Bai XH, et al. 2016. Stimulus-dependent dissociation between XB130 and Tks5 scaffold proteins promotes airway epithelial cell migration. Oncotarget 7:76437–76452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zhao J, Wang Y, Wakeham A, et al. 2014. XB130 deficiency affects tracheal epithelial differentiation during airway repair. PLoS One 9:e108952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lupu F, Terwilliger JD, Lee K, et al. 2001. Roles of growth hormone and insulin-like growth factor 1 in mouse postnatal growth. Dev Biol 229:141–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Stratikopoulos E, Szabolcs M, Dragatsis I, et al. 2008. The hormonal action of IGF1 in postnatal mouse growth. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105:19378–19383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Di Cosmo C, Liao XH, Dumitrescu AM, et al. 2010. Mice deficient in MCT8 reveal a mechanism regulating thyroid hormone secretion. J Clin Invest 120:3377–3388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ferrara AM, Liao XH, Gil-Ibanez P, et al. 2013. Changes in thyroid status during perinatal development of MCT8-deficient male mice. Endocrinology 154:2533–2541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ferrandino G, Kaspari RR, Reyna-Neyra A, et al. 2017. An extremely high dietary iodide supply forestalls severe hypothyroidism in Na(+)/I(−) symporter (NIS) knockout mice. Sci Rep 7:5329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Prummel MF, Brokken LJ, Wiersinga WM. 2004. Ultra short-loop feedback control of thyrotropin secretion. Thyroid 14:825–829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Martial JA, Seeburg PH, Guenzi D, et al. 1977. Regulation of growth hormone gene expression: synergistic effects of thyroid and glucocorticoid hormones. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 74:4293–4295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gothe S, Wang Z, Ng L, et al. 1999. Mice devoid of all known thyroid hormone receptors are viable but exhibit disorders of the pituitary-thyroid axis, growth, and bone maturation. Genes Dev 13:1329–1341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kusakabe T, Kawaguchi A, Hoshi N, et al. 2006. Thyroid-specific enhancer-binding protein/NKX2.1 is required for the maintenance of ordered architecture and function of the differentiated thyroid. Mol Endocrinol 20:1796–1809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Koumarianou P, Gomez-Lopez G, Santisteban P. 2017. Pax8 controls thyroid follicular polarity through cadherin-16. J Cell Sci 130:219–231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lodyga M, Bai XH, Kapus A, et al. 2010. Adaptor protein XB130 is a Rac-controlled component of lamellipodia that regulates cell motility and invasion. J Cell Sci 123:4156–4169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bretscher A, Reczek D, Berryman M. 1997. Ezrin: a protein requiring conformational activation to link microfilaments to the plasma membrane in the assembly of cell surface structures. J Cell Sci 110 (Pt 24):3011–3018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wald FA, Oriolo AS, Casanova ML, et al. 2005. Intermediate filaments interact with dormant ezrin in intestinal epithelial cells. Mol Biol Cell 16:4096–4107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Grasberger H, De Deken X, Mayo OB, et al. 2012. Mice deficient in dual oxidase maturation factors are severely hypothyroid. Mol Endocrinol 26:481–492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Shiozaki A, Liu M. 2011. Roles of XB130, a novel adaptor protein, in cancer. J Clin Bioinforma 1:10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bai XH, Cho HR, Moodley S, et al. 2014. XB130-a novel adaptor protein: gene, function, and roles in tumorigenesis. Scientifica (Cairo) 2014:903014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Moodley S, Hui Bai X, Kapus A, et al. 2015. XB130/Tks5 scaffold protein interaction regulates Src-mediated cell proliferation and survival. Mol Biol Cell 26:4492–4502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Jewett CE, Prekeris R. 2018. Insane in the apical membrane: Trafficking events mediating apicobasal epithelial polarity during tube morphogenesis. Traffic 19:666–678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.