Abstract

The increasing frequency of penicillin-resistant pneumococcus continues to be of concern throughout the world. Newer fluoroquinolone antibiotics, such as levofloxacin, have shown enhanced in vitro activity against Streptococcus pneumoniae. In this study, the bactericidal characteristics and pharmacodynamic profiles of levofloxacin, ciprofloxacin, and ampicillin against four isolates of S. pneumoniae were compared by using an in vitro model of infection. Standard antibiotic dosing regimens which simulated the pharmacokinetic profile observed in humans were used. Control and treatment models were sampled for bacterial CFU per milliliter over the duration of each 24- or 48-h experiment. In addition, treatment models were sampled for MIC determinations and drug concentration. Regrowth of all isolates as well as an increase in MICs throughout the study period was observed in the ciprofloxacin experiments. A limited amount of regrowth was noted during levofloxacin therapy for one isolate; however, no change in MIC was detected for any isolate. Ampicillin showed rapid and sustained bactericidal activity against all isolates. In this study, ratios of effective fluoroquinolone area under the concentration-time curve (AUC):MIC values ranged from 30 to 55. Levofloxacin, owing to its larger AUC0–24 values, has excellent and sustained activity against different pneumococcal strains superior to that of ciprofloxacin.

Streptococcus pneumoniae continues to be the leading cause of community-acquired pneumonia, acute sinusitis, and bacterial meningitis worldwide (1, 10, 15, 30). Penicillin resistance for pneumococcus has been reported to be widespread since it was first noted in 1967 (17), especially over the last 6 years (6, 14, 31). Recent surveillance studies have shown that the frequency of S. pneumoniae with reduced susceptibility to penicillin (intermediate and resistant strains) in the United States is currently around 24 to 34% (6, 32). Therefore, the continuing trend toward penicillin resistance for S. pneumoniae is leading clinicians to consider non-β-lactam alternatives for coverage of this important community-acquired pathogen.

It is well established that fluoroquinolone (FQ) antibiotics have good activity against gram-negative and atypical pathogens. However, a review of the literature shows that treatment failures have been reported for older FQ agents when used in patients infected with S. pneumoniae (3, 5, 12, 18, 20, 28, 33). Since those reports appeared, newer agents, such as levofloxacin, have been approved for use in the United States. To further investigate the activity of FQ antibiotics against S. pneumoniae, we evaluated the bactericidal and pharmacodynamic profiles of levofloxacin and ciprofloxacin against four isolates with various susceptibilities. For comparative purposes, the β-lactam ampicillin was also tested.

(This work was presented in part at the 20th International Congress of Chemotherapy, Sydney, Australia, 29 June 1997 to 3 July 1997.)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and susceptibility testing.

Thirty-five S. pneumoniae clinical isolates from Hartford Hospital were screened for susceptibility to penicillin, ciprofloxacin, and levofloxacin. MICs and minimum bactericidal concentrations (MBC) were determined according to method of the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards by using a microdilution technique (23). Four isolates which displayed a range of susceptibility profiles for penicillin, ciprofloxacin, and levofloxacin were selected.

Antibiotics.

The following antibiotics were used: sterile ampicillin sodium, 500 mg of powder for injection (lot F5V04A; expiration date, June 1999; Apothecon); ciprofloxacin for intravenous injection, 40 mg/ml (lot 5GFC; expiration date, July 1998; Bayer Corporation); and levofloxacin standard powder (RWJ-02513-097-AQ; potency, 969.5 mg/g; lot CRO38; expiration date 19 January 1997; R. W. Johnson).

Bacterial growth media.

Cation-adjusted Mueller-Hinton broth (CAMHB) (Becton Dickinson, Cockeysville, Md.) supplemented with 2.5 to 5% lysed horse blood (LHB) (Remel, Lenexa, Kans.) was used as the bacterial growth medium in all in vitro model experiments and susceptibility determinations. Trypticase soy agar plates (100-mm diameter) with 5% sheep blood and Mueller-Hinton agar plates (150-mm diameter) with 5% sheep blood (Becton Dickinson) were used for the quantitative determinations.

In vitro model.

The in vitro model used in this study has previously been described (13). By using a central compartment model, bacteria were exposed to changing concentrations of antibiotics to simulate human pharmacokinetic parameters. Each experiment consisted of three independent models (two antibiotic-treated models and one growth control model) which were run simultaneously for all organisms and treatment regimens. The models were placed in a 37°C temperature-controlled circulating water bath for optimal temperature control, and magnetic stir bars were used in each model to ensure adequate mixing of all contents. Fresh CAMHB supplemented with LHB was continuously pumped into each of the models by a peristaltic pump at rates which simulated the elimination half-lives of the test antibiotics (for ampicillin, ciprofloxacin, and levofloxacin the half-lives are 1, 4, and 7 h, respectively).

A starting inoculum of 106 CFU/ml was prepared from an overnight culture of the test isolate for all model experiments. To ensure that bacteria were in logarithmic growth phase prior to antimicrobial exposure, experiments were started 1 h after inoculation of bacteria into the models.

Twenty-four-hour studies were initially conducted for each antibiotic against all S. pneumoniae isolates. In the cases where bacterial regrowth was detected at 24 h, separate 48-h experiments were performed to further characterize antibiotic activity over time. Bacterial regrowth was assessed with quantitative cultures as outlined below. Additionally, since MIC and MBC tests were performed on samples obtained throughout the duration of each experiment, any bacteria present at the 24- or 48-h time point were therefore detected.

Antibiotics were added to the models to simulate intravenous (IV) bolus dosing for the following regimens: for ampicillin, 500 mg (with test isolate SP4) or 1,000 mg (with test isolates SP28, SP34, and SP12) IV every 6 h (q6h), with peak concentrations of 50 and 25 μg/ml, respectively; for ciprofloxacin, 400 mg IV q12h, with a peak concentration of 4.6 μg/ml; and for levofloxacin, 500 mg IV q24h, with a peak concentration of 6.4 μg/ml. To confirm the simulation of human pharmacokinetic parameters, samples were taken throughout the entire duration of the model experiment and samples were stored at −80°C until they were assayed for drug concentration.

To assess bacterial density over time, samples were obtained from each model and serially diluted in saline. Aliquots of each diluted sample were plated in triplicate for quantitative culture. To minimize any effect of antibiotic carryover on the less-diluted samples, larger plates (150-mm-diameter agar plates) were used for detection of bacterial growth. After 24-h incubation at 37°C, the change in log10 CFU/ml at 24-h intervals was calculated and time-kill curves were constructed by plotting log10 CFU/ml against time. In addition, preliminary experiments were conducted to assess the influence of antibiotic carryover with each of the test agents. As a result of these data, the limit of quantification for ampicillin was determined to be 102 CFU/ml. No antibiotic carryover was observed for the FQ; thus, the limit of quantification was 101 CFU/ml.

Development of resistance was assessed by performing MIC and MBC determinations on S. pneumoniae recovered from experimental models at 0, 6, 12, and 24 h (and at 36 and 48 h when longer experiments were performed).

Antibiotic concentration determinations.

Samples of CAMHB supplemented with LHB taken from each of the treatment models were assayed for ampicillin, levofloxacin, and ciprofloxacin. Samples containing the FQ were analyzed by an ion-paired validated high-performance liquid chromatography method as previously described (21), with modifications. CAMHB with LHB was used to prepare standards, check samples, and dilute samples as required. Briefly, 50 μl of pipemidic acid (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.) used as an internal standard was added to 200 μl of sample or standard and mixed. After the addition of 3.5 ml of methylene chloride (Mallinckrodt Baker, Paris, Ky.) for ciprofloxacin-containing samples or chloroform (Mallinckrodt Baker) for levofloxacin-containing samples, all samples were shaken for 10 min and then centrifuged at 3,000 × g for 10 min. To the organic layer, 200 μl of 0.1-mol/liter sodium hydroxide (Sigma Chemical Co.) was added, and all tubes were shaken for 20 min and then centrifuged at 3,000 × g for 15 min. Twenty microliters of the aqueous layer was injected onto a 10-μm-particle-diameter C18 column (4.6 mm [outside diameter] by 250 mm [height]) (Nucleosil; Alltech Associates, Inc., Deerfield, Ill.), and fluorescence was monitored at excitation wavelengths of 278 nm for ciprofloxacin and 282 nm for levofloxacin by using a fluorescence detector (model 980; Applied Biosystems Inc., Foster City, Calif.) with a filter with an emission cutoff of 418 nm. The mobile phase consisted of 0.01 M phosphate buffer (pH 2.5) (Sigma Chemical Co.) with 0.01 M tetrabutylammonium hydrogen sulfate (Sigma Chemical Co.) and acetonitrile (Mallinckrodt Baker) in an 87:13 ratio (vol/vol) pumped at flow rates of 1.8 ml/min for ciprofloxacin and 1.4 ml/min for levofloxacin by an isocratic pump (model 510; Waters Associates, Milford, Mass.). The assay of ciprofloxacin was linear over the range from 0.1 to 6 μg/ml. Intrarun coefficients of variation (CVs) were 1.98% (n = 10) and 2.40% (n = 10) for the check samples with low (1 μg/ml) and high (5 μg/ml) concentrations, and interrun CVs were 2.56% (n = 9), 2.17% (n = 16), and 1.92% (n = 25) for the check samples with low (0.5 and 1 μg/ml) and high (5 μg/ml) concentrations, respectively. The assay of levofloxacin was linear over the range from 0.1 to 10 μg/ml. Intrarun CVs were 1.24% (n = 10) and 0.57% (n = 10), and interrun CVs were 1.90% (n = 17) and 1.19% (n = 17), for the low (1 μg/ml) and high (8 μg/ml) check samples, respectively. The limit of sensitivity for both assays was 0.1 μg/ml.

Ampicillin concentrations in CAMHB with LHB were determined by a validated bioassay method. CAMHB supplemented with LHB was used to prepare standards and check samples and was used to dilute samples as required. Antibiotic medium 11 (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.) was seeded with a spore suspension of Bacillus subtilis ATCC 6633 (Difco) and poured into sterile, square petri dishes (245 mm by 245 mm; 20-mm depth; Nalge Nunc International, Rochester, N.Y.). After the agar cooled and hardened, four 1/4-inch paper discs (Schleicher and Schuell, Inc., Keene, N.H.) spotted with 20 μl of each standard or sample were placed on the agar in a random, Latin square pattern. The bioassay plates were incubated for 16 to 18 h at 37°C in ambient air. Zones of inhibition around the paper discs were measured and concentrations in samples were extrapolated by using the line equation from the standard curve. The limit of sensitivity of the ampicillin assay was 0.5 μg/ml, and the assay was linear over the range from 0.5 to 10 μg/ml. Intrarun CVs were 5.40% (n = 9) and 3.63% (n = 9) for the check samples with low (1.0 μg/ml) and high (7.5 μg/ml) concentrations, respectively. Interrun CVs were 5.7% (n = 29) and 5.6% (n = 29) for the check samples with low and high concentrations, respectively.

Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic analysis.

Target human pharmacokinetic parameters were selected prior to initiation of the study. By using actual drug concentration data from each set of experiments, the following parameters were determined for each antibiotic by noncompartmental methods: peak concentration (peak), elimination rate constant, half-life, and area under the curve (AUC). The AUC values were calculated by the trapezoidal method. By using experimental pharmacokinetic and screening MIC data the following pharmacodynamic parameters were determined: peak:MIC ratio, AUC0–24:MIC ratio (for ciprofloxacin and levofloxacin), and time above the MIC (for ampicillin). The higher screening MIC was used for these calculations when the MICs were one dilution apart.

RESULTS

Susceptibility testing.

Table 1 shows the preexperimental MICs of ampicillin, ciprofloxacin, and levofloxacin against the four clinical isolates utilized in this study. The screening MICs of penicillin for each isolate were as follows: for SP28, 0.06 μg/ml; for SP34, 4 μg/ml; for SP12, 0.06 μg/ml; and for SP4, 0.125 μg/ml.

TABLE 1.

Observed MICs over time in treatment models

| Antibiotic and isolate | MIC (μg/ml) at:

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Screening | 0 h | 6 h | 12 h | 24 h | 36 h | 48 h | |

| Ciprofloxacin | |||||||

| SP28 | 1 | 0.5 | 1–2 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 8–32 |

| SP34 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8–16 |

| SP12 | 4–8 | 4 | 4–8 | 4 | 8–16 | 8 | 8–32 |

| SP4 | 4 | 8 | 4 | 4 | 8–16 | 16 | 8–16 |

| Levofloxacin | |||||||

| SP28 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1–2 | NGb | ||

| SP34 | 2 | 2–4 | 2–4 | 1–2 | NG | ||

| SP12 | 2 | 2 | 4 | NG | NG, 2 | ||

| SP4 | 4 | 2 | 2–4 | 4 | 2–4 | 2 | 2 |

| Ampicillin | |||||||

| SP28 | 0.5 | NDa | NG | ||||

| SP34 | 8–16 | ND | NG | ||||

| SP12 | 0.125 | ND | NG | ||||

| SP4 | 0.25 | ND | NG | ||||

ND, not determined due to lack of growth at 6 h.

NG, no growth.

Pharmacokinetic analysis.

Target pharmacokinetic parameters and experimental pharmacokinetic data are summarized in Table 2. The FQ pharmacokinetic profiles observed in the model were similar to that of the target values. In addition, the variation of these profiles over the several months required to conduct all studies of drug-isolate combinations was minimal. While more variability was observed with the pharmacokinetic data for ampicillin relative to targeted values, the elimination half-life values were very similar and thus produced similar values for time above the MIC, the important correlate related to β-lactam activity.

TABLE 2.

Simulated dosing regimens, target human pharmacokinetic parameters, and resultant pharmacokinetic data

| Antibiotic | Simulated regimen | Peak (μg/ml) | Elimination half-life (h) | AUC (μg · h/ml)e |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ciprofloxacin | ||||

| Target parametersa | 400 mg IV q12h | 4.6 | 4 | 24 |

| Actual (mean ± SD) | 4.0 ± 0.2 | 4.2 ± 0.4 | 30.2 ± 2.6 | |

| Levofloxacin | ||||

| Target parametersb | 500 mg IV q24h | 6.4 | 7 | 54.6 |

| Actual (mean ± SD) | 5.7 ± 0.4 | 7.0 ± 0.3 | 57.7 ± 5.2 | |

| Ampicillin (isolates SP28, SP34, and SP12) | ||||

| Target parametersc | 1 g IV q6h | 50 | 1 | 60 |

| Actual (mean ± SD) | 40.9 ± 6.6 | 0.9 ± 0.1 | 65.1 ± 20.5 | |

| Ampicillin (isolate SP4) | ||||

| Target parametersd | 500 mg IV q6h | 25 | 1 | 30 |

| Actual (mean ± SD) | 10.2 ± 0.8 | 1.3 ± 0.2 | 32.7 ± 4.2 |

We are unsure why the peaks for ampicillin in the SP4 experiments were much lower than the target values. Although unlikely, it is possible that these samples might have been drawn late. In spite of the lower peaks, the resultant AUCs and elimination half-lives were close to the target values. Therefore, since time above the MIC and not magnitude of peak concentrations is the important pharmacodynamic parameter for ampicillin, the effect of the low measured peak values in this set of experiments on the results is not thought to be of extreme importance.

Bactericidal activity.

The starting inocula were all within one dilution of the target (106 CFU/ml) except for the two cases noted below. Against SP12, the starting inoculum for levofloxacin was slightly smaller than projected, and for ampicillin against SP4, a slightly larger starting inoculum was used. However, neither change appeared to have a profound influence on the bactericidal profiles of these agents.

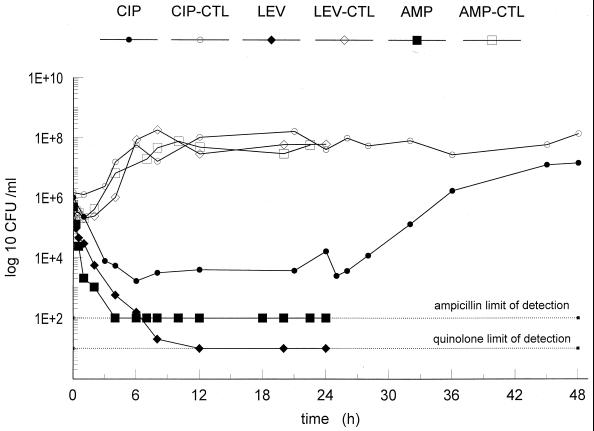

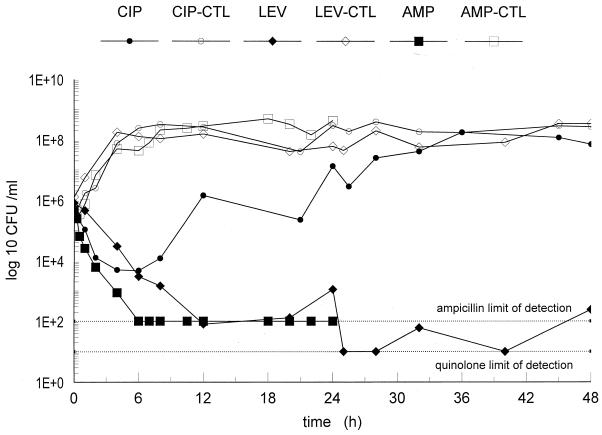

Figures 1 and 2 summarize the resultant kill curves for two of the test isolates, SP34 and SP4. Plotted data are the means for the two treatment models and the growth control model for each experiment. Rapid bactericidal effect was observed for ampicillin against all isolates; the concentrations declined to the limit of detection (102 CFU/ml) during the initial 6 h, and regrowth was not observed over the remaining 18 h, of the experiments with ampicillin. Furthermore, this was also evident in the experiment that used 500-mg doses of ampicillin against the isolate with intermediate response to penicillin, SP4.

FIG. 1.

Bactericidal activity for SP34. AMP, ampicillin; CIP, ciprofloxacin; CTL, control; LEV, levofloxacin.

FIG. 2.

Bactericidal activity for SP4. AMP, ampicillin; CIP, ciprofloxacin; CTL, control; LEV, levofloxacin.

Rapid and sustained bactericidal activity was observed for levofloxacin against all isolates except SP4, which showed regrowth at the end of each dosing interval. The rates of kill for levofloxacin, as shown by the slopes of the resultant kill curves, were comparable to those of ampicillin against SP34 and SP12.

In contrast, the rate and extent of ciprofloxacin bactericidal activity against all isolates tested were related to in vitro susceptibilities over the first 24 h. However, when experiments were continued for an additional 24-h period, diminished bactericidal activity was noted for subsequent doses and regrowth was evident for all isolates at the conclusion of the 48-h experiment.

Detection of resistance.

Table 1 shows the MIC values observed throughout the study in the treatment models, indicating that penicillin susceptibility had no impact on FQ susceptibility. Between a 1- to 2- and an 8- to 16-fold increase in ciprofloxacin MIC was observed for all experiments, as shown in Table 1. The resultant kill curves clearly reflect the observed changes in MIC since regrowth was noted for each isolate. The regrowth was more pronounced during the 24- to 48-h period.

Pharmacodynamic analysis.

The pharmacodynamic results are summarized in Table 3. All FQ peak to MIC ratios were less than 10. Bacterial regrowth was noted when the FQ AUC:MIC ratios were 28 or less. In the ampicillin experiments, the proportion of the time that the drug concentrations exceeded the MIC for the organism during the dosing interval was less than 50% only for the penicillin-resistant isolate, SP34. However, complete bactericidal activity against this isolate was noted, as shown by the lack of bacterial growth in the 6-h sample after 24-h incubation.

TABLE 3.

Pharmacodynamic analysis

| Isolate | Ciprofloxacin

|

Levofloxacin

|

Ampicillin

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peak:MIC ratio | AUC:MIC ratio | Δ Log10 CFU/ml at:

|

Peak:MIC ratio | AUC:MIC ratio | Δ Log10 CFU/ml at:

|

% time above MIC | Δ Log10 CFU/ml at:

|

||||

| 24 h | 48 h | 24 h | 48 h | 24 h | 48 h | ||||||

| SP28 | 4.2 | 28.4 | −4.9 | −0.8 | 5.2 | 55.1 | −4.7 | 100 | −5.5 | ||

| SP34 | 1.9 | 15.5 | −1.8 | +1.2 | 2.9 | 29.3 | −4.2 | 39.2 | −3.7 | ||

| SP12 | 0.5 | 3.8 | −1.5 | +1.1 | 3.1 | 30.9 | −3.4 | 100 | −3.6 | ||

| SP4 | 1.0 | 7.7 | +1.6 | +2.3 | 1.4 | 14.3 | −3.1 | −3.8 | 100 | −3.7 | |

DISCUSSION

The pharmacodynamics of the FQ are well described. It has previously been shown that these antibiotics display concentration-dependent bactericidal effect (4, 7, 8, 25). A correlation of clinical and microbiologic outcomes to the AUC:MIC ratio indicated that values of 125 or higher were predictive of clinical cures against nosocomial pathogens when ciprofloxacin was used in hospitalized patients (11). While peak:MIC ratios of 10:1 or greater appear to be associated with optimal bactericidal activity, the AUC:MIC ratio may better correlate with microbiologic effects when the peak:MIC ratio cannot be optimized (25).

The optimal AUC:MIC ratio for FQ against S. pneumoniae has not previously been determined. In this study we showed, using a wide range of MIC values, that the lower threshold of the AUC:MIC ratio for this pathogen appears to be around 30, as demonstrated by a lack of regrowth when values higher than this were achieved. Raddatz and colleagues evaluated the pharmacodynamics of trovafloxacin and ciprofloxacin against four penicillin-resistant isolates over 24 h in an in vitro model of infection (26). These investigators showed that AUC:MIC values of 187.1 for trovafloxacin resulted in superior bactericidal activity as compared with ciprofloxacin, which resulted in regrowth at 24 h for all isolates. Resultant values for ciprofloxacin AUC:MIC ratios were either 30.4 or 60.8. However, as only one ciprofloxacin dose was administered over the 24-h evaluation period in this study, the condition does not simulate actual human pharmacokinetics when dosing q12h is utilized in patients with normal renal function.

In this study, the development of resistance to ciprofloxacin for all study isolates was apparent, especially after 24 h. The induction of resistance of S. pneumoniae to FQ in vitro has been previously reported (19). After repeated transfer in ciprofloxacin, temafloxacin, and norfloxacin there was an 8- to 16-fold decrease in susceptibility, while after transfer in levofloxacin only minimal decreases in susceptibility were observed. Additionally, active efflux has been demonstrated as a mechanism of resistance to ciprofloxacin for pneumococcus (34). In our study, the actual mechanism of resistance to ciprofloxacin was not evaluated.

Our results seem to correlate well with published reports of levofloxacin clinical efficacy against S. pneumoniae (9). In summary, we have shown that complete bactericidal activity and decreased regrowth or resistance of pneumococcus was noted when FQ AUC:MIC values were around 30.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by a grant from Ortho-McNeil Pharmaceuticals.

We thank Christina Turley for technical support and Matthew Charnas for development of a diagram of the in vitro model of infection.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bartlett J G, Mundy L M. Community-acquired pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1618–1624. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199512143332408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bayer Corporation. Cipro package insert. West Haven, Conn: Bayer Corporation; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cooper B, Lawlor M. Pneumococcal bacteremia during ciprofloxacin therapy for pneumococcal pneumonia. Am J Med. 1989;87:475. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(89)80838-1. . (Letter.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Craig W A, Ebert S C. Killing and regrowth of bacteria in vitro: a review. Scand J Infect Dis Suppl. 1991;74:63–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davies B I, Maesen F P V, Baur C. Ciprofloxacin in the treatment of acute exacerbations of chronic bronchitis. Eur J Clin Microbiol. 1986;5:226–231. doi: 10.1007/BF02013995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Doern G V, Brueggemann A, Holley H P, Jr, Rauch A M. Antimicrobial resistance of Streptococcus pneumoniae recovered from outpatients in the United States during the winter months of 1994 to 1995: results of a 30-center national surveillance study. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:1208–1213. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.5.1208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Drusano G L, Johnson D E, Rosen M, Standiford H C. Pharmacodynamics of a fluoroquinolone antimicrobial agent in a neutropenic rat model of Pseudomonas sepsis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1993;37:483–490. doi: 10.1128/aac.37.3.483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dudley M N. Pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of antibiotics with special reference to the fluoroquinolones. Am J Med. 1991;91(Suppl. 6A):45S–50S. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(91)90311-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.File T M, Jr, Segreti J, Dunbar L, Player R, Kohler R, Williams R R, Kojak C, Rubin A. A multicenter, randomized study comparing the efficacy and safety of intravenous and/or oral levofloxacin versus ceftriaxone and/or cefuroxime axetil in treatment of adults with community-acquired pneumonia. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:1965–1972. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.9.1965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fine M J, Smith M A, Carson C A, Mutha S S, Sankey S S, Weissfeld L A, Kapoor W N. Prognosis and outcomes of patients with community-acquired pneumonia. A meta-analysis. JAMA. 1996;275:134–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Forrest A, Nix D E, Ballow C H, Gross T F, Birmingham M C, Schentag J J. Pharmacodynamics of intravenous ciprofloxacin in seriously ill patients. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1993;37:1073–1081. doi: 10.1128/aac.37.5.1073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frieden T R, Mangi R J. Inappropriate use of oral ciprofloxacin. JAMA. 1990;264:1438–1440. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garrison M W, Vance-Bryan K, Larson T A, Toscano J P, Rotschafer J C. Assessment of effects of protein binding on daptomycin and vancomycin killing of Staphylococcus aureus by using an in vitro pharmacodynamic model. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1990;34:1925–1931. doi: 10.1128/aac.34.10.1925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goldstein F W, Acar J F The Alexander Project Collaborative Group. Antimicrobial resistance among lower respiratory tract isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae: results of a 1992–93 Western Europe and USA collaborative surveillance study. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1996;38(Suppl. A):71–84. doi: 10.1093/jac/38.suppl_a.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gwaltney J M., Jr Acute community-acquired sinusitis. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;23:1209–1223. doi: 10.1093/clinids/23.6.1209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hampel B, Lode H, Bruckner G, Koeppe P. Comparative pharmacokinetics of sulbactam/ampicillin and clavulanic acid/amoxicillin in human volunteers. Drugs. 1988;35(Suppl. 7):29–33. doi: 10.2165/00003495-198800357-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hansman D, Bullen M M. A resistant pneumococcus. Lancet. 1967;i:264–265. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(75)91547-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kimbrough R C, III, Gerecht W B, Husted F C, Wolfe J E. The failure of ciprofloxacin to prevent the progression of Streptococcus pneumoniae infections to meningitis. Mo Med. 1991;88:635–637. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lafredo S C, Foleno B D, Fu K P. Induction of resistance of Streptococcus pneumoniae to quinolones in vitro. Chemotherapy (Basel) 1993;39:36–39. doi: 10.1159/000238971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee B L, Padula A M, Kimbrough R C, Jones S R, Chaisson R E, Mills J, Sande M A. Infectious complications with respiratory pathogens despite ciprofloxacin therapy. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:520–521. doi: 10.1056/nejm199108153250719. . (Letter.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marangos M N, Skoutelis A T, Nightingale C H, Zhu Z, Psyrogiannis A G, Nicolau D P, Bassaris H P, Quintiliani R. Absorption of ciprofloxacin in patients with diabetic gastroparesis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:2161–2163. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.9.2161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meyers B R, Wilkinson P, Mendelson M H, Walsh S, Bournazos C, Hirschman S Z. Pharmacokinetics of ampicillin-sulbactam in healthy elderly and young volunteers. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1991;35:2098–2101. doi: 10.1128/aac.35.10.2098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically. 4th ed. 1997. Approved standard. NCCLS document M7-A4. 17(2):10–13. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Wayne, Pa. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ortho Pharmaceutical Corporation. Levaquin package insert. Raritan, N.J: Ortho Pharmaceutical Corporation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Preston S L, Drusano G L, Berman A L, Fowler C L, Chow A T, Dornseif B, et al. Pharmacodynamics of levofloxacin, a new paradigm for early clinical trials. JAMA. 1998;279:125–129. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.2.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Raddatz J K, Hovde L B, Rotschafer J C. Abstracts of the 36th Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1996. An in vitro pharmacodynamic (PD) evaluation of trovafloxacin (T) against four strains of penicillin (P) resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae (SP), abstr. A61; p. 12. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rho J P, Jones A, Woo M, Castle S, Smith K, Bawdon R E, et al. Single-dose pharmacokinetics of intravenous ampicillin plus sulbactam in healthy elderly and young adult subjects. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1989;24:573–580. doi: 10.1093/jac/24.4.573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Righter J. Pneumococcal meningitis during intravenous ciprofloxacin therapy. Am J Med. 1990;88:548. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(90)90442-g. . (Letter.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ripa S, Ferrante L, Prenna M. Pharmacokinetics of sulbactam/ampicillin in humans after intravenous and intramuscular injection. Chemotherapy (Basel) 1990;36:185–192. doi: 10.1159/000238765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schuchat A, Robinson K, Wenger J D, Harrison L H, Farley M, Reingold A L, et al. Bacterial meningitis in the United States in 1995. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:970–976. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199710023371404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Simberkoff M S. Drug-resistant pneumococcal infections in the United States. JAMA. 1994;271:1875–1876. . (Editorial.) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thornsberry C, Ogilvie P, Kahn J, Mauriz Y. Surveillance of antimicrobial resistance in S. pneumoniae (Sp), H. influenzae (Hi), and M. catarrhalis (Mc) in the U.S. during the 1996–97 respiratory season. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;25:364. doi: 10.1016/s0732-8893(97)00195-8. . (Abstract 52.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thys J P. Quinolones in the treatment of bronchopulmonary infections. Rev Infect Dis. 1988;10(Suppl. 1):S212–S217. doi: 10.1093/clinids/10.supplement_1.s212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zeller V, Janoir C, Kitzis M-D, Gutmann L, Moreau N J. Active efflux as a mechanism of resistance to ciprofloxacin in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:1973–1978. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.9.1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]