Abstract

Diabetes mellitus has been linked to an increase in mitochondrial microRNA-378a (miR-378a) content. Enhanced miR-378a content has been associated with a reduction in mitochondrial genome-encoded mt-ATP6 abundance, supporting the hypothesis that miR-378a inhibition may be a therapeutic option for maintaining ATP synthase functionality during diabetes mellitus. Evidence also suggests that long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs), including lncRNA potassium voltage-gated channel subfamily Q member 1 overlapping transcript 1 (Kcnq1ot1), participate in regulatory axes with microRNAs (miRs). Prediction analyses indicate that Kcnq1ot1 has the potential to bind miR-378a. This study aimed to determine if loss of miR-378a in a genetic mouse model could ameliorate cardiac dysfunction in type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and to ascertain whether Kcnq1ot1 interacts with miR-378a to impact ATP synthase functionality by preserving mt-ATP6 levels. MiR-378a was significantly higher in patients with T2DM and 25-wk-old Db/Db mouse mitochondria, whereas mt-ATP6 and Kcnq1ot1 levels were significantly reduced when compared with controls. Twenty-five-week-old miR-378a knockout Db/Db mice displayed preserved mt-ATP6 and ATP synthase protein content, ATP synthase activity, and preserved cardiac function, implicating miR-378a as a potential therapeutic target in T2DM. Assessments following overexpression of the 500-bp Kcnq1ot1 fragment in established mouse cardiomyocyte cell line (HL-1) cardiomyocytes overexpressing miR-378a revealed that Kcnq1ot1 may bind and significantly reduce miR-378a levels, and rescue mt-ATP6 and ATP synthase protein content. Together, these data suggest that Kcnq1ot1 and miR-378a may act as constituents in an axis that regulates mt-ATP6 content, and that manipulation of this axis may provide benefit to ATP synthase functionality in type 2 diabetic heart.

Keywords: heart, lncRNA, microRNA, mitochondria, type 2 diabetes mellitus

INTRODUCTION

The frequency of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) has increased dramatically, with the World Health Organization and others documenting 422 million cases worldwide in 2014, and estimating a rise to 642 million by 2040 (1, 2). As T2DM prevalence rises, our understanding of the progression and comorbidities underlying its pathophysiological mechanisms becomes critical. Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of mortality in the diabetic population, occurring in ∼32% of patients and leading to death in ∼10% of those afflicted (1). The mechanisms contributing to the development of CVD in T2DM have not been fully elucidated, but mitochondrial dysfunction has been suggested to play a role in a number of key disease features, including the development of insulin resistance, the initial onset of disease, and the development of cardiac contractile dysfunction (3–5).

Noncoding RNAs (ncRNAs) have gained interest due to their ability to act both protectively and pathologically (6–8). MicroRNAs (miRs), a class of small ncRNAs that are ∼22 nucleotides in length, can influence the development of CVD and T2DM due to their ability to regulate transcription both outside and inside the mitochondrion (6, 9, 10). Our laboratory and others have reported significant changes in the miR profile of diabetic cardiac mitochondria (6, 11–13). Following miR profiling, microRNA-378a (miR-378a), containing two strands, miR-378a-3p and miR-378a-5p, was shown to be significantly increased in cardiac mitochondria of streptozotocin-treated mice (11). Jagannathan et al. (11) demonstrated the potential for miR-378a to bind and downregulate the expression of mitochondrial genome-encoded mt-ATP6, a component of the electron transport chain complex V (ATP synthase) F0 complex. MiR-378a downregulation of mt-ATP6 led to a decrease in ATP synthase functionality (11, 14), and treatment with miR-378a-antagomir resulted in improved cardiac systolic function in streptozotocin-treated mice (11). These were complemented by in vitro cellular models of miR-378a overexpression (11, 14). At current, the role of miR-378a remains unexplored in T2DM, the most prevalent form of diabetes mellitus.

Additional ncRNA species have been identified in the mitochondrion, including long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs) (15–17). Analysis of lncRNAs in T2DM blood samples revealed 441 differentially expressed lncRNAs, indicating that T2DM can influence the lncRNA network (17). Mitochondrial lncRNA presence has been observed, but data are limited (15). Undeniably, the role(s) played by lncRNAs in the mitochondrion is unclear. Evidence suggests that lncRNAs, including lncRNA potassium voltage-gated channel subfamily Q member 1 overlapping transcript 1 (Kcnq1ot1), may play a role in the regulatory activity of miRs through a process known as sponging, where they act as endogenous competing RNAs by binding to complementary miR response elements and influencing mRNA transcription (6, 17, 18). Kcnq1ot1 has been evaluated in a number of diabetic tissues, but its ultimate function and effect remains unclear (19–25). At current, the relationship between Kcnq1ot1 and miR-378a in the mitochondrion has not been elucidated. The objectives of this study were to determine if loss or inhibition of miR-378a could ameliorate cardiac dysfunction in T2DM and to determine whether Kcnq1ot1 interacts with miR-378a in a sponging mechanism to influence mitochondrial genome-encoded mt-ATP6 and ATP synthase functionality.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Experimental Animals

Animal experiments used in this study conformed to the National Institutes of Health Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the West Virginia University (WVU) Animal Care and Use Committee. Whole body miR-378a knockout (KO) mice were a kind gift from Dr. Eric Olson at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center (26). Experimental animals included male and female FVB/NJ wild-type (WT) mice (RRID:IMSR_JAX:001800), FVB/NJ Db/Db mice (The Jackson Laboratory stock, Cat. No. 006654) (27, 28), FVB/NJ miR-378a KO mice, and FVB/NJ miR-378a KO/Db/Db mice generated by our laboratory (Supplemental Fig. S1). Db/Db mice develop severe hyperglycemia at 5 wk of age (29). Animals were housed in the WVU Health Sciences Center animal facility on a 12-h light/dark cycle in a temperature-controlled room. Animals were maintained on a standard chow diet and had access to both food and water ad libitum. Animals were euthanized at 25 wk of age using cervical dislocation as a primary method, and critical organ removal as a secondary method of euthanasia. Cardiac ventricular tissues and serum were collected for biochemical analyses. Ideal sample sizes were determined using a two-sided power analysis, with an α value of 0.05 and a desired power of 0.80, using previously collected echocardiography values (30). Initial evaluation of cardiac function in male and female animals presented no significant differences, therefore subsequent biochemical analyses utilized a combination of sexes. No animals were excluded from the study.

KO/Db/Db Model Characterization

Weight, fasting blood glucose, serum insulin, and miR-378a levels were evaluated at 25 wk to verify diabetes mellitus progression in KO/Db/Db mice. Fasting blood glucose was measured using an Ascensia Contour blood glucose monitor (Bayer Healthcare LLC, Mishawaka IN) and corresponding blood glucose test strips (Ascensia, Cat. No. 7097 C). Serum insulin levels were measured using a Mouse Insulin ELISA Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cat. No. EMINS) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, mouse serum was collected from whole blood isolates after coagulation at room temperature for 30 min and centrifugation at 2,500 rcf for 10 min. Serum was diluted twofold, and processed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Measurements were acquired at 450 nm and 550 nm wavelengths. Values acquired at 550 nm were subtracted from values acquired at 450 nm to correct for optical imperfections in the microplate provided. MiR-378a-3p and miR-378a-5p levels were assessed to verify miR-378a loss in KO and KO/Db/Db animals using qPCR. MiR-378a genomic deletion was verified in a previous study (26).

Study Approval and Patient Population

The WVU Institutional Review Board and Institutional Biosafety Committee approved the studies and data generated from this work, including all right atrial tissue and patient information acquired. When required by the Institutional Review Board, written informed consent was received from every participant or legal guardian by the WVU Heart and Vascular Institute, J.W. Ruby Memorial Hospital. Right atrial appendages were removed during open-heart and/or valvular surgery by a single co-operating physician, and all tissue and data were stored in a double deidentified process. Atrial tissue from patients who were either nondiabetic (ND) or with T2DM was used in the analyses. Patients’ tissue was used irrespective of age, gender, and ethnicity/race. Patients with a history of smoking were excluded from the study.

Mitochondrial Isolation

Mitochondria were isolated from mouse and human cardiac tissues as previously described (31), with modifications by our laboratory (32–34). Briefly, mitochondria were isolated using a series of centrifugation steps to separate subsarcolemmal (SSM) and interfibrillar (IFM) subpopulations from nuclear and cytoplasmic portions. SSM and IFM subpopulations were combined to form a total mitochondrial population. Mitochondrial pellets were resuspended in 200 μL of KME buffer (100 mM KCl, 50 mM MOPS, and 0.5 mM EDTA; pH 7.4) to be assessed for mt-ATP6 protein and ATP synthase content, ATP synthase activity, and qPCR quantification. Nuclear portions remained once the cytoplasmic portion and mitochondria were removed and were saved for biochemical analysis.

Cross-linked Immunoprecipitation

Cross-linked immunoprecipitation (CLIP) was performed on mouse cardiac tissue as previously described (11), with modifications (35, 36). Briefly, tissues were finely minced in 1X PBS in a petri dish with a suspension depth of ∼1 mm. Samples were irradiated five times with 400 mJ/cm2 on ice using a CL-1000 Ultraviolet Crosslinker (UVP, Upland, CA), and mixed between each irradiation. Two hundred and twenty-five micrograms of protein were diluted in NP-40 buffer (20 mM Tris HCl; pH 8.0, 137 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 1% Triton X100, and 2 mM EDTA) up to 1 mL and the RNA digested by addition of 10 µL of RNase I (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cat. No. EN0601, 1:500). Fifty microliters of Protein G magnetic beads (New England Biolabs, Cat. No. S1430S) were washed three times with NP-40 buffer and then resuspended in 100 µL of NP-40 buffer and 5 µL of Recombinant Anti-Argonaute-2 antibody rabbit monoclonal (Abcam, Cat. No. ab186733, RRID:AB_2713978). The antibody was allowed to bind to the beads by rotating the tubes overnight. Beads were washed three times with NP-40 buffer, and cross-linked tissue lysates were added followed by tube rotation for 2 h at 4°C. Beads were washed three times with NP-40 buffer. Thirty microliters of NP-40 was added to the beads and heated for 10 min at 70°C with shaking (1,000 rpm). Supernatant was used for RNA isolation and qPCR analyses.

RT-qPCR

Total RNA was isolated from mouse and human mitochondria and cardiac tissue samples using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Cat. No. 74104) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Total DNA was isolated from mouse cardiac tissue using the DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit (Qiagen Cat. No. 69504) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Two-step RT-qPCR analysis was performed with miR amplification achieved using a high-capacity RNA to cDNA synthesis kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cat. No. 4387406) and SYBR Green components in a total sample volume of 25 μL:12.5 μL PowerUp SYBR Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Cat. No. A25742), 9.5 μL RNAse/nuclease free water, 1 μL of primer pair for the control (U6/GAPDH) or experimental target, and 2 μL of sample cDNA. Samples were run in duplicate for target sequence and U6 or GAPDH control. Data represented as fold change are calculated as the 2^ΔΔCt of the target sequences, with all groups represented as change relative to control. Mt-DNA content was assessed as previously described (37), with modifications. To determine mtDNA content, delta threshold cycle (Ct) values were acquired by subtracting nuclear DNA (nucDNA) from mtDNA. An Applied Biosystems 7500HT Fast Real-Time PCR System was used for analysis, with reaction conditions optimized to Origene’s qSTAR miRNA qPCR Detection System instructions. Primer pair sequences are listed in Supplemental Table S1; see http://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.18940262.

Western Blotting

Mouse and human cardiac tissues were homogenized using a Polytron PowerGen 500 S1 tissue homogenizer (Fisher Scientific, Hampton, NH) in radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cat. No. 89901), then centrifuged at 10,000 rcf for 20 min to remove debris. The supernatant was kept for Western blot analysis, and the pellet was discarded. Samples were prepared as previously described (11, 38). Briefly, a Bradford assay was used to determine protein concentration (39), and 30–50 μg of protein were used per sample. NuPAGE LDS Sample Buffer (4×) (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cat. No. NP0007) was added to samples and heated to 70°C for 10 min to denature proteins. Samples were allowed to cool to room temperature before loading into the gel. NuPAGE 12% Bis-Tris Protein Gels, 1.0 mm, 15-well gels (Invitrogen, Cat. No. NP0343BOX) and NuPAGE MES SDS Running Buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cat. No. NP0002) were used as previously described (14, 32, 40, 41). Proteins were transferred to Nitrocellulose Membrane (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cat. No. 88018), and blocked for 1 h at room temperature in 5% milk solution. Primary antibodies used in the study were: Anti-MT-ATP6 rabbit polyclonal (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cat. No. PA5-37129, RRID:AB_2553922, 1:1,000), Anti-GAPDH mouse monoclonal (Abcam, Cat. No. ab8245, RRID:AB_2107448, 1:1,000), Anti-VDAC1 mouse monoclonal (Sigma Aldrich, Cat. No. SAB5201374-100UG, 1:1,000), which was verified for specificity by Sigma Aldrich during quality control testing, and Anti-β Actin mouse monoclonal (Sigma Aldrich, Cat. No. A5316, RRID:AB_476743, 1:1,000). Secondary antibodies used in the study were: Rabbit Anti-Mouse IgG H&L (HRP) (Abcam, Cat. No. ab6728, RRID:AB_955440, 1:2,500) and Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG H&L (HRP) (Abcam, Cat. No. ab6721, RRID:AB_955447, 1:2,500). Radiance Plus Western blotting substrate (Azure Biosystems, Cat. No. AC2103) was used to detect signals per the manufacturer’s instructions. The G:Box Bioimaging system (Syngene, Frederick, MD) was used to detect luminescence, and data was captured using GeneSnap/GeneTools software. Densitometry was analyzed using ImageJ Software (ImageJ, RRID:SCR_003070) and all values were expressed as optical density with arbitrary units.

Blue Native-PAGE

ATP synthase content was assessed using blue native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (BN-PAGE) as previously described (42). Briefly, mitochondria were solubilized with 5% digitonin on ice. After addition of Coomassie G-250, samples were run on 4%–16% NativePAGE 15-well gels (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cat. No. BN1004BOX) at 150 V for 30 min, when dark buffer was replaced with light buffer and run at 250 V for 1 h, or until samples traveled the length of the gel. Following BN-PAGE, gels were removed from the cassette, rinsed with deionized water, and fixed in a solution containing 50% methanol and 8% acetic acid for 15 min. Gels were stained using a colloidal blue staining kit (Invitrogen, Cat. No. LC6025) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Optical densities were measured using ImageJ software as described in Western Blotting.

Electron Transport Chain Complex Activities

The activity of complexes I, III, IV, and ATP synthase were measured spectrophotometrically on isolated mitochondria as previously described (31, 32, 43–45). Briefly, activities were measured for complexes I (reduction of decylubiquinone), III (reduction of cytochrome c), IV (oxidation of reduced cytochrome c), and ATP synthase (pyruvate kinase, phosphoenolpyruvate, and ATP production). A Bradford assay was carried out on each sample to provide a basis for normalization of protein content. Values are expressed as nanomoles consumed per minute, per microgram of protein. For ATP synthase, this expression is equal to the nanomoles of NADH oxidized per minute, per microgram of protein.

Echocardiography

A single trained individual in the WVU Animal Models and Imaging Facility acquired ultrasound images in a blinded fashion in conscious mice to maintain normal left ventricle (LV) function and heart rate (46–49). Images were acquired using a 32–55 MHz linear array transducer on the Vevo2100 Imaging System (Visual Sonics, Toronto, Canada) as previously described (30, 32, 34, 41). Briefly, measurements including ejection fraction (EF), fractional shortening (FS), cardiac output, and stroke volume were obtained from LV images. Mouse identifiers were randomized before echocardiographic analysis to mask group and were analyzed by a single individual. M-mode measurements were calculated over at least three consecutive cardiac cycles and averaged values were considered a single replicate. This was repeated for as many M-mode videos as provided up to six replicates.

Cell Culture

The established mouse cardiomyocyte cell line (HL-1) (Millipore, Cat. No. SCC065, RRID:CVCL_0303) [Registered with the International Depositary Authority, American Type Culture Collection (ATCC); CRL-12197], which maintains a cardiac-specific phenotype following repeated passages, and an HL-1 miR-378a overexpressing cell line (HL-1-378a) generated by our laboratory, were used as previously described (11, 12, 14, 50). HL-1-378a cells demonstrate significant reductions in mt-ATP6 mRNA, mt-ATP6 protein content, and ATP synthase activity (11, 14). Cells were maintained at 5% CO2/95% air and 37°C in a Claycomb medium (Sigma Aldrich, Cat. No. 51800 C-500ML) and prepared according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The “n” presented in related results is representative of biological replicates. It should be noted that the advantage of this model is that it affords the opportunity to explore the mechanistic interaction between lncRNA Kcnq1ot1 and the miR-378a/mt-ATP6 axis in an artificial system of enhanced miR-378a presence.

Plasmid Construction

IntaRNA, lncBase, and DIANA software programs were utilized to determine Kcnq1ot1 binding sites for miR-378a (51–57). Of the two strands, miR-378a-5p was predicted to bind most strongly to Kcnq1ot1 and was utilized in plasmid production. Plasmids were generated using a pGL4.14_[luc2/Hygro] vector backbone containing a firefly luciferase reporter gene (Promega, Cat. No. E6691). Three plasmids were designed and verified for sequence insertion between restriction enzymes BglII and HindIII before delivery; a Kcnq1ot1-miR-378a-5p fragment containing the sequence for a single binding site, a 500-bp Kcnq1ot1 fragment containing three miR-378a-5p binding sites, and Kcnq1ot1 scramble (Genscript, Piscataway, NJ). Plasmids were delivered at a 1 mg/mL concentration in 1 mL of Tris-EDTA (TE) buffer. Kcnq1ot1 DNA sequences and plasmid constructs can be found in Supplemental Table S2 and Supplemental Fig. S2.

Luciferase Assay

HL-1-378a cells were seeded in a 12-well plate and transfected at 60%–70% confluency. Overexpression of Kcnq1ot1 fragments was established as previously described (14). Briefly, plasmid DNA was transfected at a concentration of 1.0 μg of DNA using Lipofectamine 3000 Transfection Reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cat. No. L3000015) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and allowed to incubate for 48 h. The Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay (Promega, Cat. No. E1910) was used to measure firefly and renilla luciferase activity according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Firefly luminescence indicating luciferase gene activation was normalized to renilla to account for background activity.

Overexpression of Kcnq1ot1 Fragment

HL-1-378a cells were seeded in a 150 mm plate and transfected at 60%–70% confluency. Overexpression of Kcnq1ot1 fragments was established as described in Luciferase Assay. Cells were transfected at a concentration of 10.5–21 µg of DNA using Lipofectamine 3000 Transfection Reagent according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Forty-eight hours post transfection, cells were harvested for biochemical analysis.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism version 8.02 (GraphPad Prism, RRID:SCR_002798). Mouse data were analyzed using a two-way ANOVA designed to compare the four experimental groups and their respective controls. Data were organized into two factors; miR-378a KO and control. The miR-378a KO factor included the miR-378a KO control group and the miR-378a KO/Db/Db group. The control factor included the WT control group and the Db/Db group. Within the two-way ANOVA, multiple-comparisons analysis was performed using a Fisher’s least significant difference (LSD) test designed to allow for each comparison with standalone. A two-tailed Student’s t test was used for statistical analysis between patients with ND and T2DM and between HL-1 cell groups. Data are presented as means ± standard error of the mean (SEM).

RESULTS

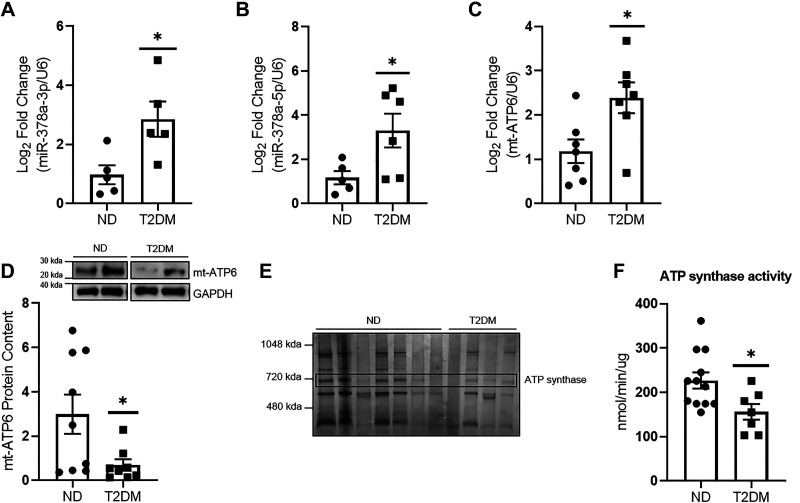

Mitochondrial miR-378a/mt-ATP6 Regulatory Axis in T2DM

MiR-378a-3p and miR-378a-5p were significantly increased in mitochondria of patients with T2DM when compared with ND (Fig. 1, A and B). Mt-ATP6 mRNA levels were significantly higher in mitochondria of patients with T2DM (Fig. 1C), while mt-ATP6 protein content was significantly decreased in mitochondria of patients with T2DM when compared with ND (Fig. 1D). ATP synthase content was decreased in T2DM, averaging 58.61% of levels in patients with ND, and corresponded to significantly lower ATP synthase activity (Fig. 1, E and F).

Figure 1.

Impact of T2DM on mitochondrial ATP synthase. A: miR-378a-3p levels were assessed in cardiac tissue of patients with ND (n = 5) and T2DM (n = 5) using qPCR. B: miR-378a-5p levels were assessed in cardiac tissue of patients with ND (n = 5) and T2DM (n = 6) using qPCR. C: quantification of mt-ATP6 mRNA in ND (n = 7) and T2DM (n = 7) total cardiac mitochondria. D: representative Western blot of mt-ATP6 protein content and quantification in ND (n = 9) and T2DM (n = 8) total cardiac mitochondria. Two blots were required to achieve a suitable “n” for all groups; therefore, a representative sample was used for normalization between gels. The representative image was constructed by taking two samples for each group from a single Western blot. E: quantification of ATP synthase content in ND (n = 7) and T2DM (n = 4) total cardiac mitochondria. ATP synthase band is marked by “ATP synthase.” F: assessment of ATP synthase activity in ND (n = 12) and T2DM (n = 7) total cardiac mitochondria. “n” is defined as biological replicates. All experiments were performed with a minimum of two technical replicates. D is based in two independent experiments. All other figure panels are based in one independent experiment. Data were analyzed using a Student’s t test. *P ≤ 0.05 vs. ND. Values are shown as means ± SE. miR-378a, microRNA-378a; ND, nondiabetic; SEM, standard error of the mean; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus. See Supplemental data.

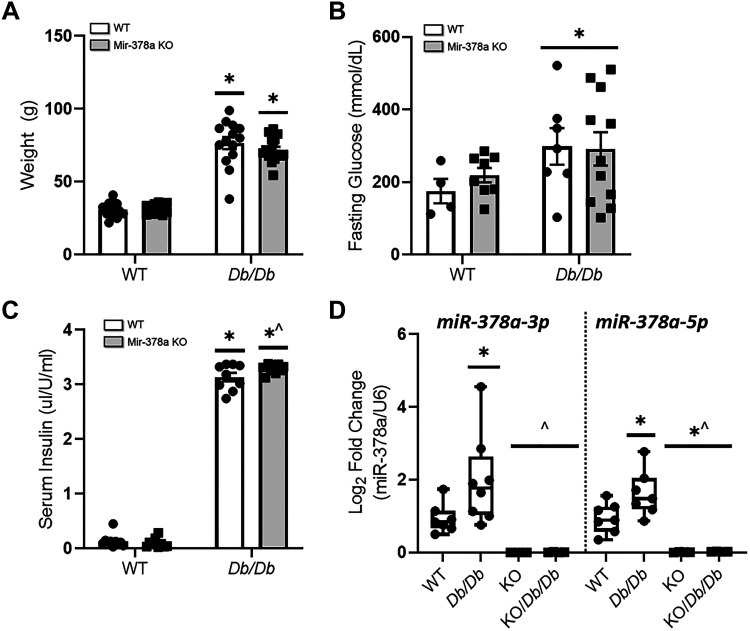

Animal Model Characterization

Weight, fasting blood glucose, serum insulin, miR-378a-3p, and miR-378a-5p levels were measured at 25 wk (Fig. 2). Body weight was significantly increased in both Db/Db and KO/Db/Db groups when compared with control, indicating development of obesity (Fig. 2A). Significant increases in fasting blood glucose in Db/Db and KO/Db/Db mice were observed when compared with control, confirming the development of hyperglycemia (Fig. 2B). Concomitantly, significant increases in serum insulin levels were observed in Db/Db and KO/Db/Db mice when compared with controls while KO/Db/Db mice also demonstrated insulin levels significantly higher than Db/Db mice, confirming the presence of hyperinsulinemia (Fig. 2C). MiR-378a-3p and miR-378a-5p levels were significantly lower in KO and KO/Db/Db animals when compared with controls, verifying significant loss of miR-378a (Fig. 2D).

Figure 2.

Characterization of miR-378a KO/Db/Db animal model. miR-378a KO/Db/Db mice were characterized by (A) weight changes in WT (n = 13), Db/Db (n = 14), KO (n = 10), and KO/Db/Db (n = 17) mice, (B) fasting glucose in WT (n = 4), Db/Db (n = 7), KO (n = 8), and KO/Db/Db (n = 12) mice, (C) serum insulin levels in WT (n = 10), Db/Db (n = 9), KO (n = 10), and KO/Db/Db (n = 9) mice, and (D) mitochondrial miR-378a-3p and miR-378-5p quantification (n = 7 all groups). All experiments were performed with a minimum of two technical replicates. “n” is defined as biological replicates. Figure panels are based in one independent experiment. Data were analyzed using a two-way ANOVA. *P ≤ 0.05 vs. WT, ^P ≤ 0.05 vs. Db/Db. Values are shown as means ± SE. miR-378a, microRNA-378a; KO, knockout; SEM, standard error of the mean; WT, wild-type. See Supplemental data.

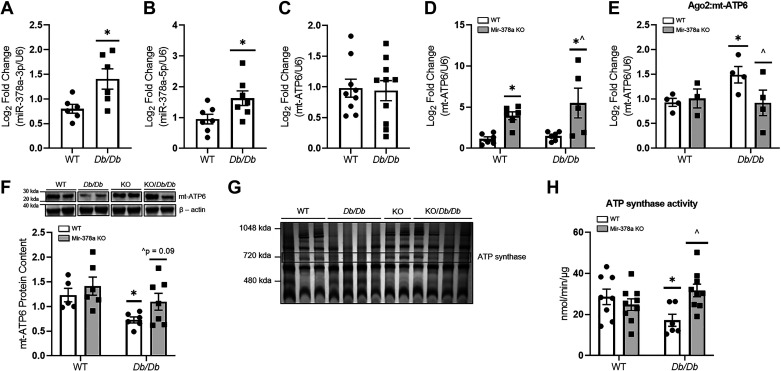

Impact of miR-378a Loss on ATP Synthase

To assess the impact of miR-378a genomic loss on ATP synthase, mt-ATP6 mRNA levels and protein content, ATP synthase content, and ATP synthase activity were assessed (Fig. 3). MiR-378a-3p and miR-378a-5p were significantly increased in Db/Db mitochondria when compared with WT (Fig. 3, A and B), whereas KO and KO/Db/Db mice contained negligible levels (Fig. 2D). Mt-ATP6 mRNA content was not significantly altered between WT and Db/Db mice (Fig. 3C) but was significantly increased in KO and KO/Db/Db mice when compared with controls (Fig. 3D). To determine whether increased translational repression of mt-ATP6 mRNA by the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) occurs in T2DM, we performed a CLIP experiment with a key RISC component, argonaute 2 (Ago2). The level of mt-ATP6 cross linked with the RICS component Ago2 was significantly higher in Db/Db mice when compared with WT, whereas KO/Db/Db mice demonstrated significantly less mt-ATP6 cross linked with RISC component Ago2, when compared with Db/Db mice (Fig. 3E). Mt-ATP6 protein content was significantly lower in Db/Db mice when compared with WT, but showed trending increases in KO/Db/Db animals when compared with Db/Db (P = 0.09) (Fig. 3F). ATP synthase content was 62.0%, 89.6%, and 124.6% in Db/Db, KO, and KO/Db/Db, respectively, when compared with WT (Fig. 3G), suggesting that modest preservation of mt-ATP6 content may allow for the preservation of total ATP synthase content in KO/Db/Db animals. ATP synthase activity in total mitochondria was significantly lower in Db/Db mice as compared with WT, but was preserved in KO/Db/Db mice, which demonstrated significantly higher ATP synthase activity when compared with Db/Db (Fig. 3H). To further assess the function of the mitochondrial electron transport chain, we assessed the activities of complexes I, III, and IV, as well as ATP content. No significant differences were observed in the activity of complexes I (Supplemental Fig. S3A) and IV (Supplemental Fig. S3C). Complex III activity was significantly altered within the diabetic condition, showing modest reductions in Db/Db mice (P = 0.06), and significant reductions in KO/Db/Db mice when compared with WT (Supplemental Fig. S3B). Finally, no significant differences were observed in mitochondrial ATP content (Supplemental Fig. S3D).

Figure 3.

Mitochondrial impacts of miR-378a loss on ATP synthase ATP-generating capacity. A: quantification of miR-378a-3p WT (n = 6) and Db/Db (n = 6) total cardiac mitochondria. B: quantification of miR-378a-5p WT (n = 7) and Db/Db (n = 7) total cardiac mitochondria. C: quantification of mt-ATP6 mRNA in WT (n = 9) and Db/Db (n = 10) total cardiac mitochondria. D: quantification of mt-ATP6 mRNA in WT (n = 6), Db/Db (n = 6), KO (n = 6), and KO/Db/Db (n = 5) mice. E: quantification of mt-ATP6 mRNA in mouse cardiac tissue following cross-linked immunoprecipitation of Ago2 in WT, Db/Db, KO, and KO/Db/Db mice (n = 5 all groups). F: representative Western blot of mt-ATP6 protein content and quantification in cardiac tissue of WT (n = 5), Db/Db (n = 6), KO (n = 6), and KO/Db/Db (n = 7) mice. Two blots were required to achieve a suitable “n” for all groups; therefore, a representative sample was used for normalization between gels. The representative image was constructed by taking two samples for each group from a single Western blot. G: quantification of ATP synthase content in WT (n = 3), Db/Db (n = 4), KO (n = 2), and KO/Db/Db (n = 4) mice. ATP synthase band is marked by “ATP synthase.” H: quantification of ATP synthase activity in WT (n = 8), Db/Db (n = 7), KO (n = 9), and KO/Db/Db (n = 9) mice. “n” is defined as biological replicates. All experiments were performed with a minimum of two technical replicates. F is based in two independent experiments. All other figure panels are based in one independent experiment. Data were analyzed using a two-way ANOVA. *P ≤ 0.05 vs. WT, ^P ≤ 0.05 vs. Db/Db. Values are shown as means ± SE. miR-378a, microRNA-378a; KO, knockout; SEM, standard error of the mean; WT, wild-type. See Supplemental data.

In addition to mitochondrial bioenergetic function, we assessed whether changes in mt-ATP6 protein content and ATP synthase functionality could be due to alterations in total mt-DNA content in KO or KO/Db/Db mice. Delta Ct values for mt-16S rRNA were found to be significantly increased in Db/Db mice and showed trending increases in KO/Db/Db mice (P = 0.09) when compared with WT controls (Supplemental Fig. S4A). Delta Ct values for mt-ATP6 were significantly increased in Db/Db and KO/Db/Db mice when compared with controls (Supplemental Fig. S4B). Mt-DNA content appeared unchanged for both mt-16s rRNA and mt-ATP6 in KO animals when compared with control, suggesting that miR-378a loss does not lead to alterations in mtDNA content (Supplemental Fig. S4).

MiR-378a Loss Improves Cardiac Function in T2DM

M-mode echocardiography was used to assess the impact of miR-378a loss on systolic cardiac function (Table 1). Db/Db mice showed significant pathological changes in M-mode parameters, with notably decreased EF and FS, increased LV mass, and increased LV volume, LV diameter, and wall thicknesses when compared with WT (Table 1). Alternatively, KO/Db/Db mice exhibited significantly higher EF and FS when compared with Db/Db counterparts, indicating preserved systolic contractile function (Table 1).

Table 1.

M-mode echocardiography assessments at 25 wk

| SAX M-Mode | WT | Db/Db | KO | KO/Db/Db |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heart rate | 684.0 ± 14.7 | 634.7 ± 17.4 | 711.2 ± 9.0 | 532.3 ± 22.6*^ |

| LVED;s, mm | 0.67 ± 0.04 | 0.90 ± 0.05* | 0.49 ± 0.05 | 0.81 ± 0.07 |

| LVED;d, mm | 2.1 ± 0.06 | 2.4 ± 0.1* | 1.8 ± 0.05 | 2.3 ± 0.1 |

| LVEV;s, μL | 0.7 ± 0.1 | 1.6 ± 0.2* | 0.4 ± 0.1 | 1.3 ± 0.2* |

| LVEV;d, μL | 13.9 ± 0.9 | 19.5 ± 1.9* | 10.6 ± 0.8 | 19.0 ± 1.6* |

| SV, μL | 13.5 ± 1.0 | 19.0 ± 2.0* | 10.3 ± 0.7 | 17.4 ± 1.4* |

| EF, % | 95.0 ± 0.5 | 91.2 ± 0.7* | 97.17 ± 0.5* | 93.63 ± 0.8^ |

| FS, % | 68.0 ± 1.4 | 60.0 ± 1.7* | 74.8 ± 1.8* | 65.8 ± 1.9^ |

| CO, mL/min | 9.3 ± 0.8 | 11.1 ± 0.8 | 6.9 ± 0.2 | 9.0 ± 0.7^ |

| LV mass, mm | 100.1 ± 7.6 | 144.9 ± 6.3* | 90.1 ± 4.8 | 139.2 ± 7.8* |

| LVAW;s, mm | 1.9 ± 0.05 | 2.1 ± 0.06* | 1.8 ± 0.06 | 2.0 ± 0.05 |

| LVAW;d, mm | 1.3 ± 0.04 | 1.5 ± 0.04* | 1.3 ± 0.05 | 1.4 ± 0.04 |

| LVPW;s, mm | 2.1 ± 0.08 | 2.3 ± 0.06* | 2.1 ± 0.05 | 2.4 ± 0.04* |

| LVPW;d, mm | 1.6 ± 0.07 | 1.8 ± 0.07* | 1.6 ± 0.05 | 2.0 ± 0.04* |

Averaged values for M-mode echocardiography. Cardiac contractile function was assessed at 25 wk of age in WT (n = 13), Db/Db (n = 14), KO (n = 10), and KO/Db/Db (n = 18) mice. “n” is defined as biological replicates. Data were analyzed using a two-way ANOVA. WT (7 males, 6 females), Db/Db (5 males, 9 females), KO (4 males, 6 females), KO/Db/Db (8 males, 10 females) *P ≤ 0.05 vs. WT, ^P ≤ 0.05 vs. Db/Db. Values are shown as means ± SE. KO, knockout; LV, left ventricle; LVAW;s, LV systolic anterior wall thickness; LVAW;d, LV diastolic anterior wall thickness; LVED;d, LV end-diastolic diameter; LVED;s, LV end-systolic diameter; LVEV;d, LV end-diastolic volume; LVEV;s, LV end-systolic volume; LVPW;d, LV diastolic posterior wall thickness; LVPW;s, LV systolic posterior wall thickness; SEM, standard error of the mean; WT, wild-type.

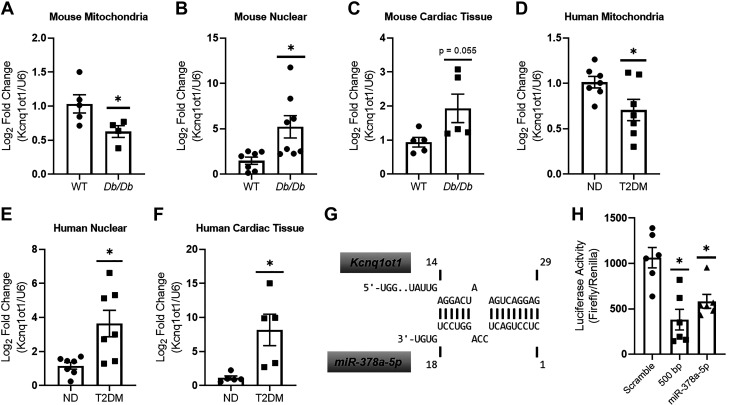

Kcnq1ot1 Alterations in T2DM and Interactions with miR-378a-5p

Mitochondrial Kcnq1ot1 levels were significantly reduced in Db/Db mice cardiac mitochondria when compared with WT (Fig. 4A), but were significantly increased in both nuclear and cardiac tissue (Fig. 4, B and C). These results were recapitulated in patients with T2DM, where Kcnq1ot1 levels were significantly lower in mitochondria of patients with T2DM when compared with ND (Fig. 4D), but were significantly higher in nuclear and cardiac tissue (Fig. 4, E and F). Using the computational reference repository DIANA, we pictorially show Kcnq1ot1 sequence complementarity to miR-378a-5p, a match to the RNA utilized for assessment of luciferase activity (Fig. 4G). Following transfection with both the Kcnq1ot1-miR-378a-5p fragment and the 500-bp Kcnq1ot1 fragment containing multiple miR-378a binding sites, luciferase activity was significantly reduced when compared with a scramble control (Fig. 4H). These results indicate that Kcnq1ot1 has the potential to interact with miR-378a-5p.

Figure 4.

Assessment of Kcnq1ot1 levels and binding of miR-378a-5p in vitro. A–C: quantification of Kcnq1ot1 in WT (n = 5) and Db/Db (n = 4) cardiac mitochondria, WT (n = 7) and Db/Db (n = 8) nuclear, and WT (n = 5) and Db/Db (n = 5) cardiac tissue, respectively. D–F: quantification of Kcnq1ot1 in ND (n = 7) and T2DM (n = 7) mitochondria, ND (n = 7) and T2DM (n = 7) nuclear (n = 6), ND (n = 5) and T2DM (n = 5) cardiac tissue, respectively. G: representative binding complementarity of Kcnq1ot1 to miR-378a-5p. H: Kcnq1ot1 binding to miR-378a-5p was assessed using an in vitro luciferase assay system (n = 6 all groups). “n” is defined as biological replicates. All experiments were performed with a minimum of two technical replicates. Figure panels are based in one independent experiment. WT and Db/Db data were analyzed using a Student’s t test. Luciferase data were analyzed using a one-way ANOVA. *P ≤ 0.05 vs. WT. Values are shown as means ± SE. miR-378a, microRNA-378a; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus; WT, wild-type. See Supplemental data.

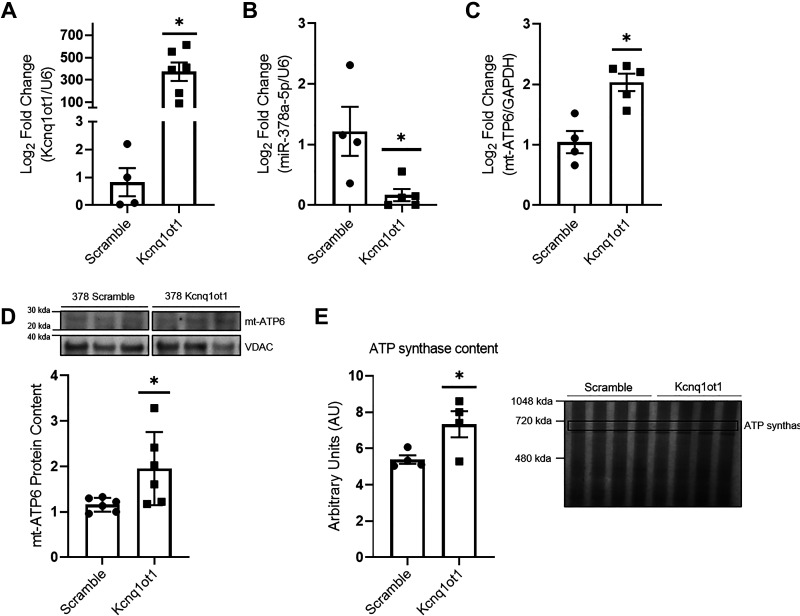

Overexpression of a 500-bp Kcnq1ot1 Fragment Leads to miR-378a-5p Inhibition

To determine the effects of Kcnq1ot1 manipulation on the miR-378a/mt-ATP6 axis, a plasmid containing a 500-bp Kcnq1ot1 fragment containing three miR-378a-5p binding sites was used to overexpress Kcnq1ot1 in vitro in HL-1 and HL-1-378a cardiomyocytes (Supplemental Fig. S5) (Fig. 5). HL-1-378a cells demonstrated significantly higher levels of miR-378a when compared with HL-1 cells (Supplemental Fig. S5A). Furthermore, miR-378a cells exhibited significantly lower mt-ATP6 protein content (Supplemental Fig. S5B). Significant increases in the 500-bp Kcnq1ot1 fragment, and significant decreases in miR-378a-5p levels, were confirmed following transfection when compared with HL-1 scramble cells (Supplemental Fig. S5, C and D). No change was observed in mt-ATP6 mRNA levels in HL-1 cells overexpressing the 500-bp Kcnq1ot1 fragment when compared with HL-1 cells overexpressing a scrambled control (Supplemental Fig. S5E). Overexpression of the 500-bp Kcnq1ot1 fragment was confirmed in HL-1-378a cells (Fig. 5A). Significant decreases in miR-378a-5p levels were observed, indicating potential binding and a change in miR-378a-5p availability (Fig. 5B). Overexpression of the 500-bp Kcnq1ot1 fragment resulted in significant increases of mt-ATP6 mRNA and protein content (Fig. 5, C and D). Finally, rescue of ATP synthase content was confirmed (Fig. 5E). These results indicate that Kcnq1ot1 may actively limit miR-378a availability and preserve ATP synthase content.

Figure 5.

Overexpression of 500-bp Kcnq1ot1 fragment in HL-1-378a cardiomyocytes. A: verification of 500-bp Kcnq1ot1 fragment overexpression in HL-1-378a scramble (n = 4) and HL-1-378a Kcnq1ot1 (n = 6) groups. B: miR-378a-5p levels were assessed following 500-bp Kcnq1ot1 fragment overexpression in HL-1-378a scramble (n = 4) and HL-1-378a Kcnq1ot1 (n = 5) groups. C: quantification of mt-ATP6 mRNA in HL-1-378a scramble (n = 4) and HL-1-378a Kcnq1ot1 (n = 5) groups. D: quantification of mt-ATP6 protein content in HL-1-378a scramble (n = 6) and HL-1-378a Kcnq1ot1 (n = 6) groups, with representative Western blot. The representative image was constructed by taking three samples for each group from the same Western blot. E: quantification of ATP synthase content in HL-1-378a scramble (n = 4) and HL-1-378a Kcnq1ot1 (n = 4) groups as marked by “ATP synthase” with representative gel image. “n” is defined as biological replicates. All experiments were performed with a minimum of two technical replicates. Figure panels are based in one independent experiment. Data were analyzed using a Student’s t test. *P ≤ 0.05 vs. Scramble. Values are shown as means ± SE. HL-1-378a, HL-1 miR-378a overexpressing cell line; Kcnq1ot1, lncRNA potassium voltage-gated channel subfamily Q member 1 overlapping transcript 1; lncRNA, long noncoding RNA; miR-378a, microRNA-378a; WT, wild-type. See Supplemental data.

DISCUSSION

T2DM-associated morbidity and mortality continues to increase in prevalence, yet therapeutic interventions to ameliorate cardiac dysfunction remain limited. The mitochondrion has received a great deal of focus due to its role in generating ATP necessary for cardiac contractile function. Thus, mitochondrially targeted therapeutics may present an opportunity for managing cardiac contractile dysfunction associated with diabetes mellitus (58, 59). The mitochondrial genome encodes 13 proteins, which are constituents of the electron transport chain complexes, including complex V, which is part of the ATP-generating complex, and ATP synthase (60). Because they are capable of regulating protein expression, miRs, such as miR-378a, may provide a therapeutic option for limiting cardiac contractile dysfunction associated with the diabetic heart (11, 14). In the current study, we determined that inhibition of miR-378a in the T2DM heart could provide benefit to ATP synthase content by preserving mt-ATP6 protein levels. In addition, our data suggest that miRs may not be the sole ncRNA regulators of mitochondrial genome-encoded proteins. Rather, other ncRNAs, such as lncRNAs, may be acting in concert with miRs to regulate mitochondrial genome-encoded protein expression. In the current study, we linked Kcnq1ot1 and miR-378a as constituents of a regulatory axis that can influence the expression of mitochondrial genome-encoded mt-ATP6, supporting the contention that the mitochondrial genome may be subject to a more complicated regulatory network.

The ncRNA network has been observed to be dysregulated in numerous pathologies, including diabetes mellitus and CVD (18, 61). NcRNAs, including miRs and lncRNAs, have been shown to be dynamic during disease states, often operating in conjunction with one another (17, 61, 62). In many cases, dynamic lncRNA expression appears to impact miRs and their downstream targets (19, 21, 25, 62–67). The association between lncRNAs and miRs has been observed in diabetes mellitus, with the discovery of each lncRNA paralleling the discovery of one or more lncRNA/miR regulatory axes (16, 17, 68). Of the many lncRNAs identified in diabetes mellitus, Kcnq1ot1 and Metastasis Associated Lung Adenocarcinoma Transcript 1 (MALAT1) are among the most highly studied (69). Evidence suggests that Kcnq1ot1 and MALAT1 may contribute to the development of diabetes mellitus and associated comorbidities (69). Specifically, both have been linked to pyroptosis, inflammation, apoptosis, and aberrant gene regulation, as part of altered miR regulatory axes in diabetes mellitus (23, 24, 66, 70, 71). Less clear are the roles of Kcnq1ot1 and MALAT1 in the diabetic heart, which have been minimally explored.

Though our data suggest a protective role for Kcnq1ot1 within the mitochondria, there is debate regarding the role of Kcnq1ot1 in the heart (23, 24, 72). Some studies suggest that Kcnq1ot1 may have deleterious effects and perpetuate dysfunction in the heart of streptozotocin-treated mice through miR-214-3p and caspase 1 repression (23, 24) while others have observed the opposite effects, and demonstrated that Kcnq1ot1 overexpression may be protective against sepsis-induced cardiac damage through sponging of miR-192-5p and downregulation of X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis (XIAP) protein content (72). The outcomes from the current study were more aligned with the later and indicated a protective role for Kcnq1ot1 in the diabetic heart. The differences in these findings may be a function of the miRs being targeted by Kcnq1ot1 and their downstream effects on cardiac function (23, 24). In addition, lncRNAs may exhibit variable intracellular presence. Indeed, our data demonstrate significant increases in Kcnq1ot1 at the nuclear and tissue level but demonstrates significant reductions specific to the mitochondria. These findings suggest that subcellular location may be an important determinant for the mechanistic action of a given lncRNA. Taken together, these data suggest that altered expression of RNAs may not be ubiquitous across tissues type and organelles.

With mitochondrial dysfunction regarded as a crucial contributor to diabetes mellitus and CVD, we focused the current study on the ncRNA network of the mitochondrion. Our data and others suggest that the noncoding regulatory network of the mitochondrion is complex and includes numerous ncRNA species. An increasing number of studies suggest that nuclear genome-encoded lncRNAs, including those residing in the nucleus or cytoplasm, as well as mitochondrial genome-encoded lncRNAs, play a role in mitochondrial genome regulation. A review by Gusic and Prokisch (69) summarized 18 lncRNAs known to impact the mitochondrial genome, including AK055347, which has been suggested to influence ATP synthase. Thus, a delicate balance needs to be maintained between the import of lncRNAs into the mitochondrion, the transcription of lncRNAs from the mitochondrial genome, and dysregulation of this balance may be incurred by disease (15, 62, 69, 73). Importantly, lncRNA activity has been demonstrated to influence the mitochondrial genome through the regulation of miRs and their downstream targets (69, 74–76). Though these interactions require further evaluation, we have also begun to explore additional lncRNAs, including MALAT1, and Nuclear Paraspeckle Assembly Transcript 1 (NEAT1), which may be impacted in T2DM mitochondria and are predicted to interact with mitochondrially localized miRs.

Due to the role of the ncRNA network in the mitochondrion, we suggest that both miRs and lncRNAs may be efficacious targets for the amelioration of mitochondrial bioenergetic and cardiac dysfunction in T2DM (11, 14, 62). The use of human right atrial tissue presents a caveat to studying whole heart mechanisms of CVD. Previous studies from our laboratory evaluating mitochondrial function in right atrial tissue from patients with T2DM reported alterations in mitochondrial morphology and bioenergetics similar to that reported in ventricular tissue of Db/Db mice, suggesting comparable pathophysiology in the tissue types utilized (14, 44, 77). Still, target identification can be problematic, often with high specificity required to achieve desired outcomes. The overlap of the miR-378a/mt-ATP6 axis in both T1DM and T2DM human and mouse cardiac tissues implicates miR-378a as a potential therapeutic target. Though each condition manifests differently, diabetes mellitus types can impact similar key mitochondrial processes (14, 78, 79). The overlap of key processes, including those relating to the production of ATP, suggest that targeting miR-378a for therapeutic intervention could be beneficial for the treatment of both diabetic phenotypes (78). As of now, generalized miR inhibition in experimental settings can be achieved through silencing mechanisms or lncRNA alteration and sponging (14, 23, 24, 66, 67, 79–82). Similarly, other reports show positive results using miR silencing for the amelioration of diabetes mellitus-related ailments (14, 80, 83).

The current study demonstrates that miR-378a KO improves mt-ATP6 protein content, ATP synthase activity, and contractile function in T2DM. Other bioenergetic assessments, including that of complex III, indicate reduced complex III activity with the diabetic condition. Still, trending decreases in Db/Db mice may be a reflection of an increased need for cytochrome c production to fuel complex IV activity and the electron gradient, and/or notably higher variability in Db/Db samples, but no significant differences were observed between diabetic groups. An additional measure of mitochondrial bioenergetics, ATP content, was assessed. Total mitochondrial ATP control was found to be unchanged in all groups despite improved ATP synthase function and contractile ability, but changes in mitochondrial ATP content in the diabetic condition have been inconsistently reported, and may not be useful as a sole indicator of overall ATP generating ability (84–87). In addition, although total mt-ATP6 mRNA levels were unchanged with the murine diabetic condition, miR-378a KO and miR-378a KO/Db/Db mice exhibited significant increases in mt-ATP6 mRNA compared with their respective controls, similar to the phenotype exhibited within patients with T2DM. Notably, we confirmed no significant differences in mt-DNA content in KO mice when compared with WT, or between diabetic groups, suggesting that changes in mt-ATP6 mRNA and protein content were not a result of miR-378a influencing total mt-DNA amount. To this point, apparent increases in mt-ATP6 mRNA, independent of changes in overall mt-DNA content, may be due to reduced interactions of mt-ATP6 mRNA with the RISC in KO/Db/Db mice. Concomitantly, Db/Db mice exhibit increased interaction of mt-ATP6 mRNA with the RISC, and reduced mt-ATP protein levels, despite unchanged levels of total mt-ATP6 mRNA. Together, these data suggest that miR-378a inhibition may provide benefit to ATP synthase through reduced interaction of mt-ATP6 mRNA with the RISC, and therefore reduced translational interference. The mechanism of translational interference, whether translational repression or mRNA degradation, is unclear. Current literature emphasizes the ambiguity in our understanding of miR-mediated mRNA repression and degradation, with evidence to support the occurrence of both, but minimal evidence available to describe their mechanisms (88–92). Hence, further experimentation is necessary to fully elucidate the fate of mitochondrial mRNAs following RISC interaction.

In addition to miRs, IncRNAs may be utilized to target mitochondrially located miRs and the mitochondrial genome (69). We suggest that downregulation of mitochondrial genome-encoded proteins may be rescued by reducing the availability of miRs known to target the mitochondrial genome (11, 14). To our knowledge, this study is the first to identify mitochondrially localized Kcnq1ot1, as well as identify reductions in Kcnq1ot1 levels in cardiac mitochondria. LncRNAs have been speculated to act in a sponging fashion by regulating and often inhibiting miR activity, but this is the first study, to our knowledge, to identify a role for Kcnq1ot1 as a potential regulator of mitochondrial genome-encoded proteins via the miR-378a-5p/mt-ATP6 axis. Notably, though overexpression of the 500-bp Kcnq1ot1 fragment in HL-1 cardiomyocytes exhibiting baseline levels of miR-378a, decreased detectable miR-378a-5p content, it did not result in changes in mt-ATP6 mRNA content. These results were logical, as one would suspect that healthy cells are able to transcribe mt-ATP6 mRNA freely when miR-378a levels are not pathologically elevated. As a result, miR-378a inhibition ultimately had no effect on mt-ATP6 content. In addition, though the mechanism we postulate influences the mitochondrial genome, both RNAs are of nuclear origin, thus, we cannot disregard the possibility that Kcnq1ot1 may interact with miR-378a cytosolically, resulting in reduced miR-378a within the mitochondrion (11, 14). Nevertheless, the efficacy of lncRNAs as therapeutic targets for mitochondrial genome-encoded proteins requires more elucidation. The fate of miRs following lncRNA binding is variable and currently unclear, with some suggesting that miRs are sequestered by the lncRNA and later released, and others suggesting that lncRNA binding can initiate degradation (93–95).

Conclusions

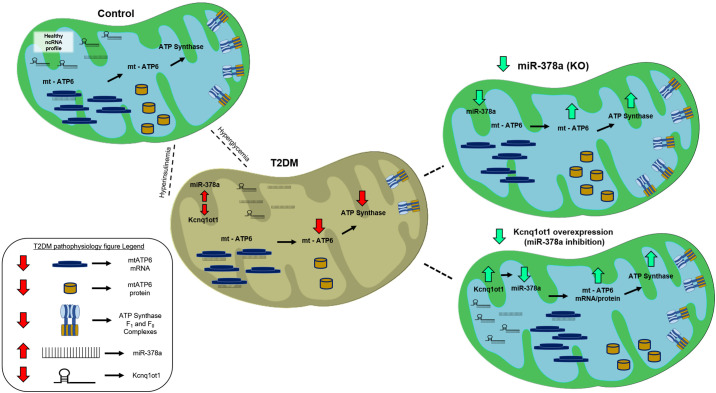

In summary, Kcnq1ot1 and miR-378a may act as constituents of a regulatory axis that can influence the expression of mitochondrial genome-encoded mt-ATP6 in the T2DM heart. Furthermore, overexpression of Kcnq1ot1 may reduce miR-378a levels and preserve mt-ATP6 protein content, suggesting that Kcnq1ot1 may participate in the regulation of the mitochondrial genome (Fig. 6). Our data suggest that dysregulation of the ncRNA network may impact regulation of the mitochondrial genome, with evidence to suggest that lncRNA Kcnq1ot1 may act as a regulatory target in T2DM to rescue mitochondrially encoded mt-ATP6 protein expression.

Figure 6.

Summary overview of ncRNA network disruption in T2DM and rescue by miR-378a KO and inhibition. T2DM is characterized by increased mitochondrial miR-378a levels, decreased mt-ATP6 protein content, and decreased ATP synthase content and activity. miR-378a KO/Db/Db mice lack miR-378a expression, and demonstrate significant improvements in mt-ATP6 protein content, ATP synthase content, and ATP synthase activity. These results are recapitulated in a cellular model when Kcnq1ot1, a lncRNA significantly reduced in T2DM mitochondria, is overexpressed, indicating the efficacy of Kcnq1ot1 as a therapeutic to benefit ATP synthase functionality. Kcnq1ot1, lncRNA potassium voltage-gated channel subfamily Q member 1 overlapping transcript 1; KO, knockout; lncRNA, long noncoding RNA; miR-378a, microRNA-378a; ncRNA, noncoding RNA; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus. See Supplemental data.

DATA AVAILABILITY

The data that support this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

SUPPLEMENTAL DATA

Supplemental Tables S1 and S2 and Supplemental Figs. S1–S5: http://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.18940262.

GRANTS

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute Grant HL128485 and the WVU CTSI Grant U54GM104942 (to J.M.H.), by a National Science Foundation IGERT: Research and Education in Nanotoxicology at West Virginia University Fellowship Grant 1144676 (to Q.A.H.), by an American Heart Association Predoctoral Fellowship (AHA 17PRE33660333) (to Q.A.H.), by an American Heart Association Predoctoral Fellowship (AHA 20PRE3508170) (to A.K.), by the West Virginia IDeA Network of Biomedical Research WV-INBRE supported by the National Institutes of Health Grant (P20GM103434), and by the Community Foundation for the Ohio Valley Whipkey Trust (to J.M.H.). All funding sources provided support for the study design, collection, analysis, and interpretation of data.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

A.J.D., Q.A.H., A.D.T., D.L.S., and J.M.H. conceived and designed research; A.J.D., Q.A.H., A.K., A.D.T., M.V.P., S.R., D.L.S., C.C.C., and G.K.F. performed experiments; A.J.D. and Q.A.H. analyzed data; A.J.D., Q.A.H., A.K., A.D.T., M.V.P., and S.R. interpreted results of experiments; A.J.D. prepared figures; A.J.D. drafted manuscript; A.J.D., A.K., A.D.T., S.R., and J.M.H. edited and revised manuscript; A.J.D., Q.A.H., A.K., A.D.T., M.V.P., S.R., D.L.S., C.C.C., G.K.F., and J.M.H. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge Dr. Eric Olson for willingness to share miR-378a knockout mice, which were used for the studies.

REFERENCES

- 1.Einarson TR, Acs A, Ludwig C, Panton UH. Prevalence of cardiovascular disease in type 2 diabetes: a systematic literature review of scientific evidence from across the world in 2007–2017. Cardiovasc Diabetol 17: 83, 2018. doi: 10.1186/s12933-018-0728-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Diabetes. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/diabetes. [2021 Nov 10]

- 3.Rindler PM, Crewe CL, Fernandes J, Kinter M, Szweda LI. Redox regulation of insulin sensitivity due to enhanced fatty acid utilization in the mitochondria. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 305: H634–H643, 2013. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00799.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Formentini L, Ryan AJ, Gálvez-Santisteban M, Carter L, Taub P, Lapek JD Jr, Gonzalez DJ, Villarreal F, Ciaraldi TP, Cuezva JM, Henry RR. Mitochondrial H(+)-ATP synthase in human skeletal muscle: contribution to dyslipidaemia and insulin resistance. Diabetologia 60: 2052–2065, 2017. [Erratum in Diabetologia 61: 2674, 2018]. doi: 10.1007/s00125-017-4379-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fealy CE, Mulya A, Axelrod CL, Kirwan JP. Mitochondrial dynamics in skeletal muscle insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. Transl Res 202: 69–82, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2018.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hathaway QA, Pinti MV, Durr AJ, Waris S, Shepherd DL, Hollander JM. Regulating microRNA expression: at the heart of diabetes mellitus and the mitochondrion. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 314: H293–H310, 2018. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00520.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Joladarashi D, Thandavarayan RA, Babu SS, Krishnamurthy P. Small engine, big power: microRNAs as regulators of cardiac diseases and regeneration. Int J Mol Sci 15: 15891–15911, 2014. doi: 10.3390/ijms150915891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nigi L, Grieco GE, Ventriglia G, Brusco N, Mancarella F, Formichi C, Dotta F, Sebastiani G. MicroRNAs as regulators of insulin signaling: research updates and potential therapeutic perspectives in type 2 diabetes. Int J Mol Sci 19: 3705, 2018. doi: 10.3390/ijms19123705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baradan R, Hollander JM, Das S. Mitochondrial miRNAs in diabetes: just the tip of the iceberg. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 95: 1156–1162, 2017. doi: 10.1139/cjpp-2016-0580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell 116: 281–297, 2004. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00045-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jagannathan R, Thapa D, Nichols CE, Shepherd DL, Stricker JC, Croston TL, Baseler WA, Lewis SE, Martinez I, Hollander JM. Translational regulation of the mitochondrial genome following redistribution of mitochondrial microRNA (MitomiR) in the diabetic heart. Circ Cardiovasc Genet 8: 785–802, 2015. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.115.001067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baseler WA, Thapa D, Jagannathan R, Dabkowski ER, Croston TL, Hollander JM. miR-141 as a regulator of the mitochondrial phosphate carrier (Slc25a3) in the type 1 diabetic heart. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 303: C1244–C1251, 2012. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00137.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Verma SK, Garikipati VNS, Kishore R. Mitochondrial dysfunction and its impact on diabetic heart. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis 1863: 1098–1105, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2016.08.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shepherd DL, Hathaway QA, Pinti MV, Nichols CE, Durr AJ, Sreekumar S, Hughes KM, Stine SM, Martinez I, Hollander JM. Exploring the mitochondrial microRNA import pathway through polynucleotide phosphorylase (PNPase). J Mol Cell Cardiol 110: 15–25, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2017.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dong Y, Yoshitomi T, Hu JF, Cui J. Long noncoding RNAs coordinate functions between mitochondria and the nucleus. Epigenetics Chromatin 10: 41, 2017. doi: 10.1186/s13072-017-0149-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leung A, Natarajan R. Long noncoding RNAs in diabetes and diabetic complications. Antioxid Redox Signal 29: 1064–1073, 2018. doi: 10.1089/ars.2017.7315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang F, Chen Y, Xue Z, Lv Y, Shen L, Li K, Zheng P, Pan P, Feng T, Jin L, Yao Y. High-throughput sequencing and exploration of the lncRNA-circRNA-miRNA-mRNA network in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Biomed Res Int 2020: 8162524, 2020. doi: 10.1155/2020/8162524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moore JB 4th, Uchida S. Functional characterization of long noncoding RNAs. Curr Opin Cardiol 35: 199–206, 2020. doi: 10.1097/HCO.0000000000000725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shao J, Pan X, Yin X, Fan G, Tan C, Yao Y, Xin Y, Sun C. KCNQ1OT1 affects the progression of diabetic retinopathy by regulating miR-1470 and epidermal growth factor receptor. J Cell Physiol 234: 17269–17279, 2019. doi: 10.1002/jcp.28344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu J, Dong Y, Wen Y, Shi L, Zhu Z, Ke G, Gu Y. LncRNA KCNQ1OT1 knockdown inhibits viability, migration and epithelial-mesenchymal transition in human lens epithelial cells via miR-26a-5p/ITGAV/TGF-beta/Smad3 axis. Exp Eye Res 200: 108251, 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2020.108251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li J, Li M, Bai L. KCNQ1OT1/miR-18b/HMGA2 axis regulates high glucose-induced proliferation, oxidative stress, and extracellular matrix accumulation in mesangial cells. Mol Cell Biochem 476: 321–331, 2021. doi: 10.1007/s11010-020-03909-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang Y, Song Z, Li X, Xu S, Zhou S, Jin X, Zhang H. Long noncoding RNA KCNQ1OT1 induces pyroptosis in diabetic corneal endothelial keratopathy. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 318: C346–C359, 2020. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00053.2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang F, Qin Y, Lv J, Wang Y, Che H, Chen X, Jiang Y, Li A, Sun X, Yue E, Ren L, Li Y, Bai Y, Wang L. Silencing long non-coding RNA Kcnq1ot1 alleviates pyroptosis and fibrosis in diabetic cardiomyopathy. Cell Death Dis 9: 1000, 2018. doi: 10.1038/s41419-018-1029-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang F, Qin Y, Wang Y, Li A, Lv J, Sun X, Che H, Han T, Meng S, Bai Y, Wang L. LncRNA KCNQ1OT1 mediates pyroptosis in diabetic cardiomyopathy. Cell Physiol Biochem 50: 1230–1244, 2018. doi: 10.1159/000494576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang C, Gong Y, Li N, Liu X, Zhang Y, Ye F, Guo Q, Zheng J. Long noncoding RNA Kcnq1ot1 promotes sC5b-9-induced podocyte pyroptosis by inhibiting miR-486a-3p and upregulating NLRP3. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 320: C355–C364, 2021. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00403.2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carrer M, Liu N, Grueter CE, Williams AH, Frisard MI, Hulver MW, Bassel-Duby R, Olson EN. Control of mitochondrial metabolism and systemic energy homeostasis by microRNAs 378 and 378*. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109: 15330–15335, 2012. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1207605109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chua S Jr, Liu SM, Li Q, Yang L, Thassanapaff VT, Fisher P. Differential beta cell responses to hyperglycaemia and insulin resistance in two novel congenic strains of diabetes (FVB- Lepr (db)) and obese (DBA- Lep (ob)) mice. Diabetologia 45: 976–990, 2002. doi: 10.1007/s00125-002-0880-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang Z, Jiang T, Li J, Proctor G, McManaman JL, Lucia S, Chua S, Levi M. Regulation of renal lipid metabolism, lipid accumulation, and glomerulosclerosis in FVBdb/db mice with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes 54: 2328–2335, 2005. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.8.2328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.The Jackson Laboratory. FVB.BKS(D)-Leprdb/ChuaJ. https://www.jax.org/strain/006654.

- 30.Shepherd DL, Nichols CE, Croston TL, McLaughlin SL, Petrone AB, Lewis SE, Thapa D, Long DM, Dick GM, Hollander JM. Early cardiac dysfunction in the type 1 diabetic heart using speckle-tracking based strain imaging. J Mol Cell Cardiol 90: 74–83, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2015.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dabkowski ER, Baseler WA, Williamson CL, Powell M, Razunguzwa TT, Frisbee JC, Hollander JM. Mitochondrial dysfunction in the type 2 diabetic heart is associated with alterations in spatially distinct mitochondrial proteomes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 299: H529–H540, 2010. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00267.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kunovac A, Hathaway QA, Pinti MV, Goldsmith WT, Durr AJ, Fink GK, Nurkiewicz TR, Hollander JM. ROS promote epigenetic remodeling and cardiac dysfunction in offspring following maternal engineered nanomaterial (ENM) exposure. Part Fibre Toxicol 16: 24, 2019. doi: 10.1186/s12989-019-0310-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hathaway QA, Durr AJ, Shepherd DL, Pinti MV, Brandebura AN, Nichols CE, Kunovac A, Goldsmith WT, Friend SA, Abukabda AB, Fink GK, Nurkiewicz TR, Hollander JM. miRNA-378a as a key regulator of cardiovascular health following engineered nanomaterial inhalation exposure. Nanotoxicology 13: 644–663, 2019. doi: 10.1080/17435390.2019.1570372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kunovac A, Hathaway QA, Pinti MV, Durr AJ, Taylor AD, Goldsmith WT, Garner KL, Nurkiewicz TR, Hollander JM. Enhanced antioxidant capacity prevents epitranscriptomic and cardiac alterations in adult offspring gestationally-exposed to ENM. Nanotoxicology 15: 812–831, 2021. doi: 10.1080/17435390.2021.1921299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tollervey JR, Curk T, Rogelj B, Briese M, Cereda M, Kayikci M, König J, Hortobágyi T, Nishimura AL, Zupunski V, Patani R, Chandran S, Rot G, Zupan B, Shaw CE, Ule J. Characterizing the RNA targets and position-dependent splicing regulation by TDP-43. Nat Neurosci 14: 452–458, 2011. doi: 10.1038/nn.2778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.O'Geen H, Echipare L, Farnham PJ. Using ChIP-seq technology to generate high-resolution profiles of histone modifications. Methods Mol Biol 791: 265–286, 2011. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-316-5_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Quiros PM, Goyal A, Jha P, Auwerx J. Analysis of mtDNA/nDNA ratio in mice. Curr Protoc Mouse Biol 7: 47–54, 2017. doi: 10.1002/cpmo.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Croston TL, Shepherd DL, Thapa D, Nichols CE, Lewis SE, Dabkowski ER, Jagannathan R, Baseler WA, Hollander JM. Evaluation of the cardiolipin biosynthetic pathway and its interactions in the diabetic heart. Life Sci 93: 313–322, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2013.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem 72: 248–254, 1976. doi: 10.1006/abio.1976.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nichols CE, Shepherd DL, Knuckles TL, Thapa D, Stricker JC, Stapleton PA, Minarchick VC, Erdely A, Zeidler-Erdely PC, Alway SE, Nurkiewicz TR, Hollander JM. Cardiac and mitochondrial dysfunction following acute pulmonary exposure to mountaintop removal mining particulate matter. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 309: H2017–H2030, 2015. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00353.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hathaway QA, Durr AJ, Shepherd DL, Pinti MV, Brandebura AN, Nichols CE, Kunovac A, Goldsmith WT, Friend SA, Abukabda AB, Fink GK, Nurkiewicz TR, Hollander JM. miRNA-378a as a key regulator of cardiovascular health following engineered nanomaterial inhalation exposure. Nanotoxicology 13: 644–620, 2019. doi: 10.1080/17435390.2019.1570372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jha P, Wang X, Auwerx J. Analysis of mitochondrial respiratory chain supercomplexes using blue native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (BN-PAGE). Curr Protoc Mouse Biol 6: 1–14, 2016. doi: 10.1002/9780470942390.mo150182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dabkowski ER, Williamson CL, Bukowski VC, Chapman RS, Leonard SS, Peer CJ, Callery PS, Hollander JM. Diabetic cardiomyopathy-associated dysfunction in spatially distinct mitochondrial subpopulations. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 296: H359–H369, 2009. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00467.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Croston TL, Thapa D, Holden AA, Tveter KJ, Lewis SE, Shepherd DL, Nichols CE, Long DM, Olfert IM, Jagannathan R, Hollander JM. Functional deficiencies of subsarcolemmal mitochondria in the type 2 diabetic human heart. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 307: H54–H65, 2014. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00845.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Trounce IA, Kim YL, Jun AS, Wallace DC. Assessment of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation in patient muscle biopsies, lymphoblasts, and transmitochondrial cell lines. Methods Enzymol 264: 484–509, 1996. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(96)64044-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rottman JN, Ni G, Khoo M, Wang Z, Zhang W, Anderson ME, Madu EC. Temporal changes in ventricular function assessed echocardiographically in conscious and anesthetized mice. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 16: 1150–1157, 2003. doi: 10.1067/S0894-7317(03)00471-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pachon RE, Scharf BA, Vatner DE, Vatner SF. Best anesthetics for assessing left ventricular systolic function by echocardiography in mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 308: H1525–H1529, 2015. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00890.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Roth DM, Swaney JS, Dalton ND, Gilpin EA, Ross J Jr.. Impact of anesthesia on cardiac function during echocardiography in mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 282: H2134–H2140, 2002. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00845.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pan G, Munukutla S, Kar A, Gardinier J, Thandavarayan RA, Palaniyandi SS. Type-2 diabetic aldehyde dehydrogenase 2 mutant mice (ALDH 2*2) exhibiting heart failure with preserved ejection fraction phenotype can be determined by exercise stress echocardiography. PLoS One 13: e0195796, 2018. [Erratum in PLoS One 13: e0203581, 2018]. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0195796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Claycomb WC, Lanson NA Jr, Stallworth BS, Egeland DB, Delcarpio JB, Bahinski A, Izzo NJ Jr.. HL-1 cells: a cardiac muscle cell line that contracts and retains phenotypic characteristics of the adult cardiomyocyte. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95: 2979–2984, 1998. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.6.2979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Karagkouni D, Paraskevopoulou MD, Tastsoglou S, Skoufos G, Karavangeli A, Pierros V, Zacharopoulou E, Hatzigeorgiou AG. DIANA-LncBase v3: indexing experimentally supported miRNA targets on non-coding transcripts. Nucleic Acids Res 48: D101–D110, 2020. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz1036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Paraskevopoulou MD, Karagkouni D, Vlachos IS, Tastsoglou S, Hatzigeorgiou AG. microCLIP super learning framework uncovers functional transcriptome-wide miRNA interactions. Nat Commun 9: 3601, 2018. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-06046-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mann M, Wright PR, Backofen R. IntaRNA 2.0: enhanced and customizable prediction of RNA–RNA interactions. Nucleic Acids Res 45: W435–W439, 2017. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wright PR, Georg J, Mann M, Sorescu DA, Richter AS, Lott S, Kleinkauf R, Hess WR, Backofen R. CopraRNA and IntaRNA: predicting small RNA targets, networks and interaction domains. Nucleic Acids Res 42: W119–W123, 2014.doi: 10.1093/nar/gku359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Busch A, Richter AS, Backofen R. IntaRNA: efficient prediction of bacterial sRNA targets incorporating target site accessibility and seed regions. Bioinformatics 24: 2849–2856, 2008. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Raden M, Ali SM, Alkhnbashi OS, Busch A, Costa F, Davis JA, Eggenhofer F, Gelhausen R, Georg J, Heyne S, Hiller M, Kundu K, Kleinkauf R, Lott SC, Mohamed MM, Mattheis A, Miladi M, Richter AS, Will S, Wolff J, Wright PR, Backofen R. Freiburg RNA tools: a central online resource for RNA-focused research and teaching. Nucleic Acids Res 46: W25–W29, 2018. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Paraskevopoulou MD, Georgakilas G, Kostoulas N, Reczko M, Maragkakis M, Dalamagas TM, Hatzigeorgiou AG. DIANA-LncBase: experimentally verified and computationally predicted microRNA targets on long non-coding RNAs. Nucleic Acids Res 41: D239–D245, 2013. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Uusitupa M, Khan TA, Viguiliouk E, Kahleova H, Rivellese AA, Hermansen K, Pfeiffer A, Thanopoulou A, Salas-Salvadó J, Schwab U, Sievenpiper JL. Prevention of type 2 diabetes by lifestyle changes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrients 11: 2611, 2019. doi: 10.3390/nu11112611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Brown DA, Perry JB, Allen ME, Sabbah HN, Stauffer BL, Shaikh SR, Cleland JGF, Colucci WS, Butler J, Voors AA, Anker SD, Pitt B, Pieske B, Filippatos G, Greene SJ, Gheorghiade M. Expert consensus document: mitochondrial function as a therapeutic target in heart failure. Nat Rev Cardiol 14: 238–250, 2017. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2016.203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Taanman JW. The mitochondrial genome: structure, transcription, translation and replication. Biochim Biophys Acta 1410: 103–123, 1999. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(98)00161-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bonnet S, Boucherat O, Paulin R, Wu D, Hindmarch CCT, Archer SL, Song R, Moore JB 4th, Provencher S, Zhang L, Uchida S. Clinical value of non-coding RNAs in cardiovascular, pulmonary, and muscle diseases. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 318: C1–C28, 2020. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00078.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jakubik D, Fitas A, Eyileten C, Jarosz-Popek J, Nowak A, Czajka P, Wicik Z, Sourij H, Siller-Matula JM, De Rosa S, Postula M. MicroRNAs and long non-coding RNAs in the pathophysiological processes of diabetic cardiomyopathy: emerging biomarkers and potential therapeutics. Cardiovasc Diabetol 20: 55, 2021. doi: 10.1186/s12933-021-01245-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yu L, Fu J, Yu N, Wu Y, Han N. Long noncoding RNA MALAT1 participates in the pathological angiogenesis of diabetic retinopathy in an oxygen-induced retinopathy mouse model by sponging miR-203a-3p. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 98: 219–227, 2020. doi: 10.1139/cjpp-2019-0489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Shaker OG, Abdelaleem OO, Mahmoud RH, Abdelghaffar NK, Ahmed TI, Said OM, Zaki OM. Diagnostic and prognostic role of serum miR-20b, miR-17-3p, HOTAIR, and MALAT1 in diabetic retinopathy. IUBMB Life 71: 310–320, 2019. doi: 10.1002/iub.1970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhang H, Yan Y, Hu Q, Zhang X. LncRNA MALAT1/microRNA let-7f/KLF5 axis regulates podocyte injury in diabetic nephropathy. Life Sci 266: 118794, 2021. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2020.118794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Che H, Wang Y, Li H, Li Y, Sahil A, Lv J, Liu Y, Yang Z, Dong R, Xue H, Wang L. Melatonin alleviates cardiac fibrosis via inhibiting lncRNA MALAT1/miR-141-mediated NLRP3 inflammasome and TGF-β1/Smads signaling in diabetic cardiomyopathy. FASEB J 34: 5282–5298, 2020. doi: 10.1096/fj.201902692R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Xia C, Liang S, He Z, Zhu X, Chen R, Chen J. Metformin, a first-line drug for type 2 diabetes mellitus, disrupts the MALAT1/miR-142-3p sponge to decrease invasion and migration in cervical cancer cells. Eur J Pharmacol 830: 59–67, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2018.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chang W, Wang J. Exosomes and their noncoding RNA cargo are emerging as new modulators for diabetes mellitus. Cells 8: 853, 2019. doi: 10.3390/cells8080853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gusic M, Prokisch H. ncRNAs: new players in mitochondrial health and disease? Front Genet 11: 95, 2020. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2020.00095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wu A, Sun W, Mou F. lncRNAMALAT1 promotes high glucoseinduced H9C2 cardiomyocyte pyroptosis by downregulating miR1413p expression. Mol Med Rep 23: 259, 2021. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2021.11898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wang C, Liu G, Yang H, Guo S, Wang H, Dong Z, Li X, Bai Y, Cheng Y. MALAT1-mediated recruitment of the histone methyltransferase EZH2 to the microRNA-22 promoter leads to cardiomyocyte apoptosis in diabetic cardiomyopathy. Sci Total Environ 766: 142191, 2021. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.142191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sun F, Yuan W, Wu H, Chen G, Sun Y, Yuan L, Zhang W, Lei M. LncRNA KCNQ1OT1 attenuates sepsis-induced myocardial injury via regulating miR-192-5p/XIAP axis. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 245: 620–630, 2020. doi: 10.1177/1535370220908041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Chen G, Guo H, Song Y, Chang H, Wang S, Zhang M, Liu C. Long noncoding RNA AK055347 is upregulated in patients with atrial fibrillation and regulates mitochondrial energy production in myocardiocytes. Mol Med Rep 14: 5311–5317, 2016. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2016.5893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Tamara M, Sirey KR, Haerty W, Bedoya-Reina O, Rogatti-Granados S, Tan JY, Li N, Heather LC, Carter RN, Cooper S, Finch AJ, Wills J, Morton NM, Marques AC, Ponting CP. Correction: the long non-coding RNA Cerox1 is a post transcriptional regulator of mitochondrial complex I catalytic activity. eLife 8: e50980, 2019. doi: 10.7554/eLife.50980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tian T, Lv X, Pan G, Lu Y, Chen W, He W, Lei X, Zhang H, Liu M, Sun S, Ou Z, Lin X, Cai L, He L, Tu Z, Wang X, Tannous BA, Ferrone S, Li J, Fan S. Long noncoding RNA MPRL promotes mitochondrial fission and cisplatin chemosensitivity via disruption of pre-miRNA processing. Clin Cancer Res 25: 3673–3688, 2019. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-2739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Li H-J, Sun X-M, Li Z-K, Yin Q-W, Pang H, Pan J-J, Li X, Chen W. LncRNA UCA1 promotes mitochondrial function of bladder cancer via the MiR-195/ARL2 signaling pathway. Cell Physiol Biochem 43: 2548–2561, 2017. doi: 10.1159/000484507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hathaway QA, Roth SM, Pinti MV, Sprando DC, Kunovac A, Durr AJ, Cook CC, Fink GK, Cheuvront TB, Grossman JH, Aljahli GA, Taylor AD, Giromini AP, Allen JL, Hollander JM. Machine-learning to stratify diabetic patients using novel cardiac biomarkers and integrative genomics. Cardiovasc Diabetol 18: 78, 2019. doi: 10.1186/s12933-019-0879-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hollander JM, Thapa D, Shepherd DL. Physiological and structural differences in spatially distinct subpopulations of cardiac mitochondria: influence of cardiac pathologies. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 307: H1–H14, 2014. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00747.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Jagannathan R, Thapa D, Nichols CE, Shepherd DL, Stricker JC, Croston TL, Baseler WA, Lewis SE, Martinez I, Hollander JM. Translational regulation of the mitochondrial genome following redistribution of mitochondrial microRNA in the diabetic heart. Circ Cardiovasc Genet 8: 785–802, 2015. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.115.001067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bijkerk R, Esguerra JLS, Ellenbroek JH, Au YW, Hanegraaf MAJ, de Koning EJ, Eliasson L, van Zonneveld AJ. In vivo silencing of microRNA-132 reduces blood glucose and improves insulin secretion. Nucleic Acid Ther 29: 67–72, 2019. doi: 10.1089/nat.2018.0763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Zhu L, Zhong Q, Yang T, Xiao X. Improved therapeutic effects on diabetic foot by human mesenchymal stem cells expressing MALAT1 as a sponge for microRNA-205-5p. Aging (Albany NY) 11: 12236–12245, 2019. doi: 10.18632/aging.102562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Liu SX, Zheng F, Xie KL, Xie MR, Jiang LJ, Cai Y. Exercise reduces insulin resistance in type 2 diabetes mellitus via mediating the lncRNA MALAT1/microRNA-382-3p/resistin axis. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids 18: 34–44, 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.omtn.2019.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Liang C, Gao L, Liu Y, Liu Y, Yao R, Li Y, Xiao L, Wu L, Du B, Huang Z, Zhang Y. MiR-451 antagonist protects against cardiac fibrosis in streptozotocin-induced diabetic mouse heart. Life Sci 224: 12–22, 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2019.02.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Munusamy S, Saba H, Mitchell T, Megyesi JK, Brock RW, Macmillan-Crow LA. Alteration of renal respiratory Complex-III during experimental type-1 diabetes. BMC Endocr Disord 9: 2, 2009. doi: 10.1186/1472-6823-9-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Wu J, Luo X, Thangthaeng N, Sumien N, Chen Z, Rutledge MA, Jing S, Forster MJ, Yan LJ. Pancreatic mitochondrial complex I exhibits aberrant hyperactivity in diabetes. Biochem Biophys Rep 11: 119–129, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrep.2017.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Guo X, Wu J, Du J, Ran J, Xu J. Platelets of type 2 diabetic patients are characterized by high ATP content and low mitochondrial membrane potential. Platelets 20: 588–593, 2009. doi: 10.3109/09537100903288422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Szendroedi J, Schmid AI, Chmelik M, Toth C, Brehm A, Krssak M, Nowotny P, Wolzt M, Waldhausl W, Roden M. Muscle mitochondrial ATP synthesis and glucose transport/phosphorylation in type 2 diabetes. PLoS Med 4: e154, 2007. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Freimer JW, Hu TJ, Blelloch R. Decoupling the impact of microRNAs on translational repression versus RNA degradation in embryonic stem cells. eLife 7: e38014, 2018. doi: 10.7554/eLife.38014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]