Keywords: blood-brain barrier, exercise, insulin, pharmacokinetics

Abstract

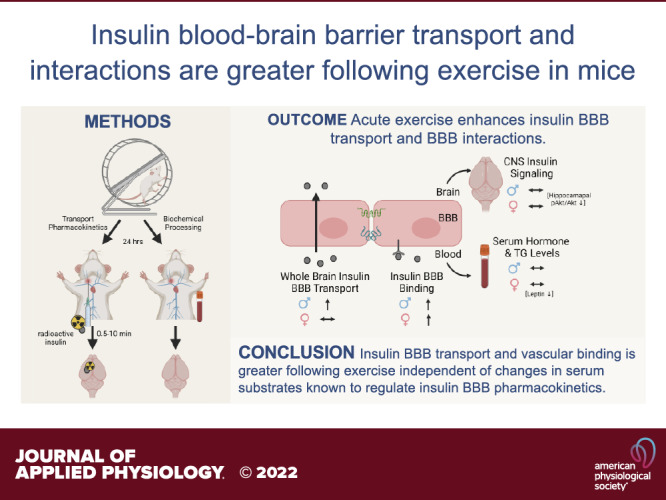

Exercise has multiple beneficial effects including improving peripheral insulin sensitivity, improving central function such as memory, and restoring a dysregulated blood-brain barrier (BBB). Central nervous system (CNS) insulin resistance is a common feature of cognitive impairment, including Alzheimer’s disease. Delivery of insulin to the brain can improve memory. Endogenous insulin must cross the BBB to directly act within the CNS and this transport system can be affected by various physiological states and serum factors. Therefore, the current study sought to investigate whether exercise could enhance insulin BBB transport as a mechanism for the underlying benefits of exercise on cognition. We investigated radioactive insulin BBB pharmacokinetics following an acute bout of exercise in young, male and female CD-1 mice. In addition, we investigated changes in serum levels of substrates that are known to affect insulin BBB transport. Finally, we measured the basal level of a downstream protein involved in insulin receptor signaling in various brain regions as well as muscle. We found insulin BBB transport in males was greater following exercise, and in males and females to both enhance the level of insulin vascular binding and alter CNS insulin receptor signaling, independent of changes in serum factors known to alter insulin BBB transport.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY Central nervous system (CNS) insulin and exercise are beneficial for cognition. CNS insulin resistance is present in Alzheimer’s disease. CNS insulin levels are regulated by transport across the blood-brain barrier (BBB). We show that exercise can enhance insulin BBB transport and binding of insulin to the brain’s vasculature in mice. There were no changes in serum factors known to alter insulin BBB pharmacokinetics. We conclude exercise could impact cognition through regulation of insulin BBB transport.

INTRODUCTION

Over the past few decades, central nervous system (CNS) insulin resistance has become recognized as an important feature of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and mild cognitive impairment (MCI). CNS insulin resistance shares many features of peripheral insulin resistance, like reduced insulin receptor signaling, but can also occur independently. One current hypothesis underlying the development of CNS insulin resistance is altered transport of insulin at the blood-brain barrier (BBB) (1). Insulin must cross the BBB to act within the CNS. There is evidence for decreased insulin BBB transport in AD in humans (2). Human clinical and rodent studies have shown that increasing CNS insulin levels can improve memory (3–5). Human clinical and rodent studies have shown that exercise can improve memory (6–8) and peripheral insulin sensitivity (9). Therefore, it is possible that exercise can increase CNS insulin levels through enhancing BBB transport as a mechanism to improve memory.

Insulin BBB pharmacokinetics are known to be affected by various physiological states and serum factors, including AD, diabetes, obesity, and serum triglyceride and insulin levels. Exercise induces changes in the physiological state and alters the level of multiple different serum factors, including triglycerides, which are known to impair insulin BBB transport and subsequent CNS insulin receptor signaling response to insulin (10, 11). Exercise is known to stimulate the release of peripheral proteins including myokines, such as irisin (12, 13), liver proteins, such as Gpdl1 (8), and growth factors, such as brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) (14, 15), which are known to improve memory. These data support peripheral substrate mediation of memory. Exercise can improve the structure of a BBB that is dysregulated (16) but the impact of exercise on hormone transport at the BBB is largely unexplored. Study of possible alterations in BBB transport systems due to exercise has been limited to lactate transport (17) and amyloid β clearance (18), both of which are increased. Glucose transport has also been investigated but is more complex in that plasma glucose levels, exercise intensity, and time of testing following exercise can impact the directional change in glucose brain uptake (19, 20).

Here, we sought to determine whether acute exercise could enhance insulin BBB transport, modify insulin interactions with the BBB, and alter CNS insulin receptor signaling. We hypothesized insulin BBB transport would be greater with exercise, which could be a mechanism for the exercise-mediated memory improvements reported in the literature. To investigate this hypothesis, we performed radioactive insulin transport studies in young, wild-type male and female mice following acute exercise.

METHODS

Animals and Exercise Regimen

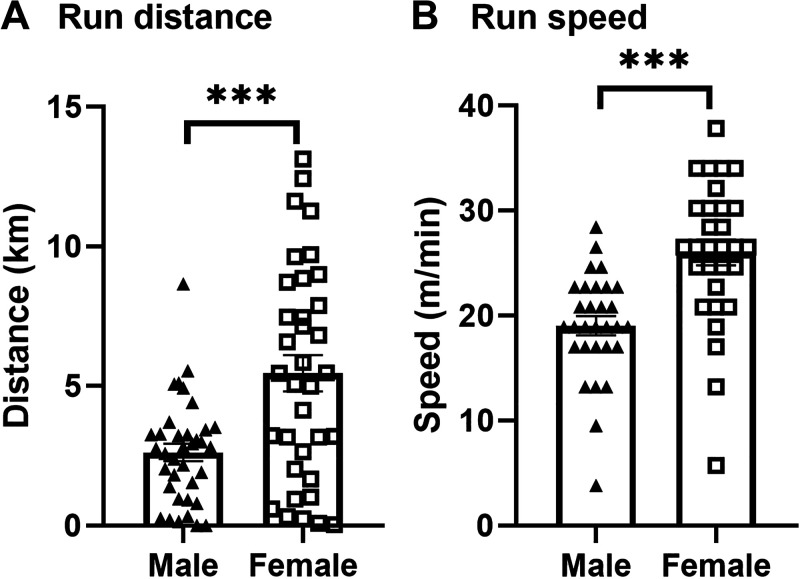

Two-month-old male and female CD-1 mice (Charles River Laboratory, Seattle, WA) were kept on 12-h light/dark cycles (lights on at 06:00 AM) and given ad libitum access to food and water. For acclimation to the wheel and housing environment, mice were split into individual cages containing a locked, low-profile, computer-monitored running wheel (Med Associates Inc., Fairfax, VT) for at least 48 h (21), though this acclimation period is not critical for running wheel (22–24). After at least 2 days, mice were randomly assigned to Exercise (n = 24) or Sedentary (n = 16) groups for transport pharmacokinetics (consisting of two cohorts run at separate times), Exercise (n = 12) or Sedentary (n = 8) for regional distribution, and Exercise (n = 5) or Sedentary (n = 5) for biochemical analysis. Numbers of mice (n) for each experiment were selected based on previous studies using similar techniques (25, 26). For the mice assigned to Exercise, running wheels were unlocked for a period of 24 h to enable voluntary wheel running. Sedentary controls were exposed to a locked running wheel for the same duration. All experiments were performed during the light cycle at ∼12:00 PM. There was no difference between the average distance ran between cohorts for each sex (data not shown). Time since the last exercise, defined as greater than 0.25 km/h before tissue collection, was 7.9 ± 0.3 h in males and 6.3 ± 0.3 in females (means ± SE). Female mice ran for 5.5 ± 0.6 km compared with 2.6 ± 0.3 km for males (Fig. 1A). Average running speed was greater in female mice (26.0 ± 1.2 m/min) compared with male mice (19.0 ± 0.9 m/min) (Fig. 1B). These data are similar to what has previously been reported for exercise behavior on a running wheel in mice (24).

Figure 1.

Voluntary running wheel exercise characterization for 24 h exposure period. Mean values for run distance (A) in km and run speed (B) in m/min ± SE. t test: ***P < 0.0001, n = 26–36/sex.

All animal procedures were approved by the Veterans Affairs Puget Sound Health Care System Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and performed at an approved facility (Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International, AAALAC).

Radioactive Labeling

Using radioactive tracers affords us the ability to quantify BBB pharmacokinetics without requiring the administration of high doses of insulin. One millicurie (mCi) of 125I (Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA) was added to 10 μg of human insulin (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) diluted in 0.25 M, chloride-free sodium phosphate buffer (PB, pH 7.5). The radioactive labeling reaction was initiated by the addition of 10 μg of chloramine-T (Sigma Aldrich) diluted in 0.25 M PB. After 60 s, the reaction was terminated by the addition of 100 μg of sodium metabisulfite (Sigma Aldrich). Albumin (Sigma Aldrich) was labeled either with 1 mCi of technetium-99m (99mTc, Radioisotope Life Sciences, Tampa, FL) or 2 mCi of 131I (Radioisotope Life Sciences). 99mTc-albumin was labeled by combining 1 mg of bovine serum albumin (BSA) with 0.5 mL of deionized water, 120 μg of stannous tartrate, and 20 μL of 1 M HCl. 131I-albumin was labeled by adding 10 μg of BSA diluted in 0.25 M PB to 10 μg of chloramine-T diluted in 0.25 M PB. After 60 s, the reaction was terminated by the addition of 100 μg of sodium metabisulfite. A column of Sephadex G-10 (Sigma Aldrich) was used to purify both 125I-insulin and 99mTc/131I-albumin and 100 μL fractions were collected in 100 μL of 1% BSA/lactated Ringers (BSA/LR). Protein binding to the respective isotope was characterized by 30% trichloroacetic acid (TCA) precipitation. The observed radioactivity in the precipitated 125I-insulin fraction was consistently above 95%, and above 85% for 99mTc/131I-albumin. The estimated specific activity for 125I-insulin was 200 Ci/g.

Multiple-Time Regression Analysis (BBB Pharmacokinetics)

Following the 24-h period of voluntary running wheel exposure and immediately before all studies, mice were anesthetized with 40% urethane (1.5–4 g/kg ip) (Sigma Aldrich) to minimize pain and distress. Following exposure of the right jugular vein, mice received an intravenous injection of 0.2 mL of 1% BSA/LR containing either 1 × 106 cpm (counts per minute) of 125I-insulin and 5 × 105 cpm of 99mTc-albumin or 1 × 105 cpm of 131I-albumin. 99mTc/131I-albumin was coinjected as a marker for vascular space (27). We approximate that 5 µg of insulin is labeled with the 125I and we injected 1 × 106 cpm of 125I-insulin. Therefore, we can approximate that 2.3 ng insulin is present in the radioactive injectate. Blood from the left carotid artery was collected between 0.5 and 10 min after intravenous injection. Mice were decapitated and olfactory bulb, whole brain, and hypothalamus were removed and weighed. Each mouse provided a single blood sample and time-matched brain sample. The arterial blood was centrifuged at 5,400 g for 10 min and serum collected. The levels of radioactivity in serum (50 μL) and brain samples were counted in a gamma counter (Wizard2, Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA). Exposure time was calculated from the formula:

| (1) |

where Cp is the level of radioactivity (cpm) in serum at time (t). Exposure time corrects for the clearance of insulin from the blood. The influx of insulin was calculated by multiple-time regression analysis as described by Patlak and coworkers (27, 28):

| (2) |

where Am is the level of radioactivity (cpm) per gram of brain tissue at time t, Cpt is the level of radioactivity (cpm) per milliliter of arterial serum at time t, Ki (μL/g·min) is the steady-state rate of unidirectional solute influx from blood to brain. Vi (μL/g) is the level of rapid and reversible binding for brain that usually is a combination of vascular space plus any brain endothelial cell receptor binding. The brain/serum (B/S) ratios for insulin were corrected for vascular space by subtracting the corresponding ratio for albumin, yielding a delta B/S ratio. The linear portion of the relation between the delta B/S ratio versus exposure time is represented in the figures and was used to calculate the Ki (μL/g·min) with its standard error term, and the y-intercept determined as representation of the Vi (μL/g) (27). The B/S ratio for 99mTc/131I-albumin did not differ over time. For regional studies, brain and serum were collected at a single time point (5 min). Brains were dissected into 10 regions according to the method described by Glowinski and Iversen (29) and weighed. Whole brain values were summed from individual regions. WB, whole brain; OB, olfactory bulb; St, striatum; FC, frontal cortex; Hy, hypothalamus; Hi, hippocampus; Th, thalamus; PC, parietal cortex; OC, occipital cortex; CB, cerebellum; MB, midbrain; Po, pons/medulla. Delta B/S ratios were calculated as described earlier and average levels between the sedentary and exercise groups were compared.

Biochemical Processing

Tissue sample preparation.

Brain vasculature was washed out with 20 mL ice-cold LR before sample collection as previously described (25). Briefly, the thoracic cavity was opened and blood was collected from the descending aorta. The heart was exposed, both jugulars were severed, and the descending thoracic aorta was clamped. The brain vasculature was washed out by perfusing 20 mL of ice-cold LR into the left ventricle of the heart. The olfactory bulb and brains were removed and the brain was dissected on ice in a modified manner according to Glowinski and Iversen (29), collecting the frontal cortex and striatum together, hypothalamus, hippocampus, and remaining brain. The left gastrocnemius muscle was also collected. Blood was centrifuged at 5,400 g for 10 min and serum collected. Aliquoted serum and snap-frozen tissue samples were stored at −80°C until further processing.

Tissue samples were each homogenized in radioimmunoprecipitation (RIPA) buffer (150 mM NaCl, 0.5% deoxycholic acid, 0.1% SDS, 20 mM Tris HCl, 2 mM EDTA, pH 8) plus 1/100 dilutions of protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma Aldrich), phosphatase inhibitor (1 tablet PhosSTOP/10 mL buffer) (Roche), and 1 mM sodium orthovanadate (Sigma Aldrich). Samples were pulse sonicated at 40% amplitude (1.5 s on, 3.5 s off, 3 times) and centrifuged at 12,000 g for 10 min at 4°C. The protein containing supernatant was collected and pellets discarded. Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL) was used to measure protein content. Tissue lysates were prepared for equal protein content and solubilized/denatured in NuPAGE Sample Buffer (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY). Equal volume aliquots were stored at −80°C before Western immunoblot.

Measurement of Serum Factors

A panel of eight metabolic hormones was measured in the serum using a Bio-Plex Pro Mouse Diabetes Assay (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA): ghrelin, glucose-dependent insulinotropic peptide (GIP), glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1), glucagon, insulin, leptin, plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1), and resistin. The serum was diluted at 1:4 with the kit diluent. Samples were measured according to the manufacturer and read on a Bio-Plex 200 (Bio-Rad Laboratories). Triglycerides were measured using a colorimetric assay kit (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI). Serum was diluted 1:2 with the kit diluent and measured according to the manufacturer using a Synergy 2 BioTek plate reader (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA).

Western Immunoblot

Tissue lysates (30 μg) were heated at 70°C for 10 min before loading on a 4%–12% Bis-Tris gel (Invitrogen). Gels were resolved at constant voltage in MOPS buffer. Gels were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes using the iBlot Gel Transfer System (Invitrogen). Membranes were blocked with 5% BSA in 0.1% Tween-20 (Sigma) in Tris-buffered saline (TBST) at room temperature for 1 h. Membranes were probed with primary antibodies (Cell Signaling Technologies, Danvers, MA). Phosphorylated Akt (pAkt S473-1:1,000, Cat. No. 4058), Akt (1:2,000, Cat. No. 4691), and β-actin (1:10,000, Cat. No. 3700) were diluted in 5% BSA/TBST overnight at 4°C. Membranes were washed in TBST before being probed with anti-rabbit or mouse secondary antibodies conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (Jackson Labs, West Grove, PA; 1:10,000) at room temperature for 1 h. Following wash steps in TBST at room temperature, membranes were illuminated with Amersham ECL Prime substrate (GE Life Sciences, Piscataway, NJ) or SuperSignal West Pico PLUS (Thermo Fisher).

The ImageQuant LAS4000 CCD imaging system (GE Life Sciences, Piscataway, NJ) was used for protein band visualization of blots. The ImageQuant IQTL software system (GE Life Sciences) was used to quantify protein band concentrations of blots using densitometric analysis of protein bands. The phosphorylated proteins’ band intensities were normalized to corresponding total protein levels’ band intensities, and the ratios of phosphorylated/total protein or total protein/β-actin were made relative to the female sedentary mouse group. Following imaging, membranes were washed with TBS at room temperature and stripped of the antibodies using Restore Western Blot Stripping Buffer (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL). For stripping of gastrocnemius, membranes were incubated with 0.2 M NaOH buffer and then washed in deionized water. Membranes were washed in TBS and blocked in 5% BSA/TBST for 1 h at room temperature. Subsequent steps were repeated as described earlier to reprobe membranes overnight at 4°C with new primary antibodies for total Akt protein levels and β-actin.

Statistical Analysis

Voluntary wheel running data were obtained via interfacing data acquisition software (Med Associates Inc., Fairfax, VT). Regression analyses and other statistical analyses were performed with Prism 8.0 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA). Males and females were studied on separate days and are therefore analyzed separately, except for the amount of running distance and biochemical measurements. Running distance and run speed are reported with their standard error terms and analyzed using a t test. Regional delta B/S levels, serum factor levels, and protein levels are reported with their standard error terms and analyzed by a two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s post hoc test when appropriate. For pharmacokinetic studies, the slope of the linear regression lines (Ki), reported with their correlation coefficients I, and y-intercepts (Vi) were compared statistically using the Prism software. Pearson correlations between running distance or run speed and insulin brain levels were calculated using the Prism software.

RESULTS

Impact of Acute Exercise on Insulin Transport across the BBB

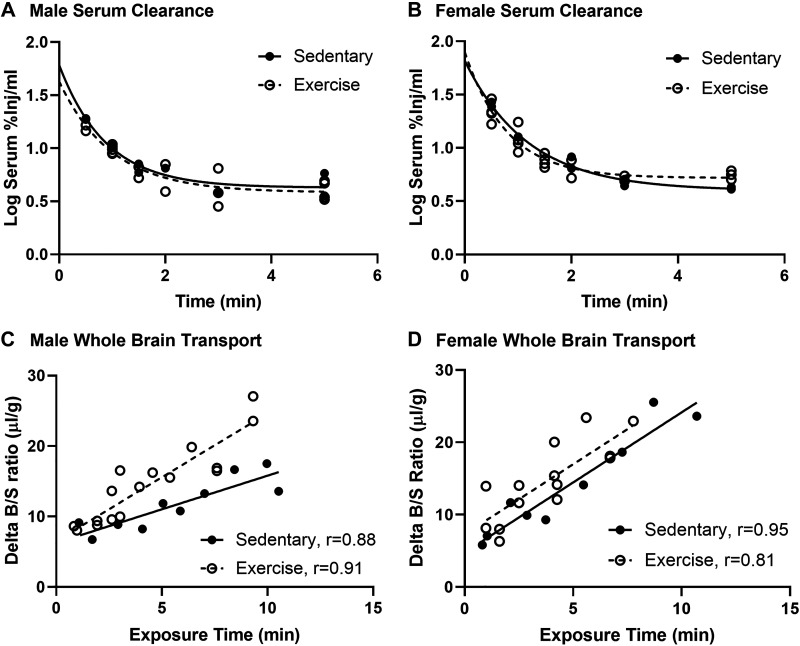

There was no effect of acute exercise on insulin serum clearance in males or females (Fig. 2, A and B). Based on the serum clearance curves, we know that 50 %Inj/mL and 70 %Inj/mL for females are present in the blood immediately after injection, with levels decreasing to 5% by 5 min. In male mice, whole brain insulin BBB transport was nearly twofold greater due to acute exercise (Fig. 2C, Table 1, Sedentary Ki = 0.95 ± 0.18 µL/g·min vs. Exercise Ki = 1.81 ± 0.21 µL/g·min, P = 0.0072). Transport kinetics for the olfactory bulb and the hypothalamus are represented in Table 1. Although there was no significant difference in the transport rate for insulin in the olfactory bulb, there was a significantly greater level of vascular binding of insulin due to exercise in males (Table 1, Sedentary Vi = −0.97 ± 2.5 µL/g vs. Exercise Vi = 10.09 ± 2.8 µL/g, P = 0.0001). There were no differences in insulin pharmacokinetics in the hypothalamus in males (Table 1).

Figure 2.

Effects of acute exercise on insulin pharmacokinetics in male and female mice. Serum clearance 125I-insulin levels in males (A) and females (B). Linear whole brain 125I-insulin blood-brain barrier (BBB) transport (C) was significantly greater in males but not in females (D). Pharmacokinetic data are listed in Tables 1 and 2. Distance run reported in means ± SE: males = 2.6 ± 0.3 km, females = 5.8 ± 0.8 km.

Table 1.

Male insulin BBB pharmacokinetics following acute exercise

| Region | Treatment | Ki, µL/g·min | Ki P Value | r | Vi, µL/g | Vi P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whole brain | Sedentary | 0.95 ± 0.18 | 0.0072 | 0.88 | 6.3 ± 1.2 | |

| Exercise | 1.81 ± 0.21 | 0.91 | 6.5 ± 1.1 | |||

| Olfactory bulb | Sedentary | 3.70 ± 0.42 | 0.710 | 0.98 | −1.0 ± 2.5 | 0.0001 |

| Exercise | 4.06 ± 0.63 | 0.91 | 10.1 ± 2.8 | |||

| Hypothalamus | Sedentary | 4.28 ± 0.10 | 0.347 | 0.92 | −0.7 ± 5.4 | 0.305 |

| Exercise | 2.84 ± 0.95 | 0.65 | 9.3 ± 4.3 | |||

BBB, blood-brain barrier; Ki, linear transport ± standard error mean; P value, difference between sedentary and exercise within brain region; r, correlation coefficient, Vi, level of reversible vascular binding ± SE.

Table 2.

Female insulin BBB pharmacokinetics following acute exercise

| Region | Treatment | Ki, µL/g·min | Ki P Value | r | Vi, µL/g | Vi P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whole brain | Sedentary | 1.94 ± 0.23 | 0.998 | 0.95 | 4.8 ± 1.3 | 0.054 |

| Exercise | 1.94 ± 0.40 | 0.81 | 7.3 ± 1.8 | |||

| Olfactory bulb | Sedentary | 3.93 ± 0.88 | 0.746 | 0.80 | 10.7 ± 6.1 | 0.694 |

| Exercise | 3.55 ± 0.70 | 0.74 | 14.6 ± 4.6 | |||

| Hypothalamus | Sedentary | 2.79 ± 0.83 | 0.057 | 0.89 | 2.9 ± 6.3 | 0.004 |

| Exercise | 1.45 ± 0.23 | 0.91 | 1.1 ± 2.2 | |||

BBB, blood-brain barrier; Ki, linear transport ± standard error mean; P value, difference between Sedentary and Exercise within brain region; r, correlation coefficient; Vi, level of reversible vascular binding ± SE.

In females, there was no effect of exercise on whole brain insulin BBB transport due to acute exercise (Fig. 2D, Table 1, Sedentary Ki = 1.94 ± 0.23 µL/g·min vs. Exercise Ki = 1.94 ± 0.24 µL/g·min, P = 0.998). There was a trend toward a nearly 50% greater level of vascular binding of insulin with exercise (Table 1, Sedentary Vi = 4.8 ± 1.3 µL/g vs. Exercise Vi = 7.3 ± 1.8 µL/g, P = 0.054). There were no differences in insulin pharmacokinetics in the olfactory bulb in females (Table 1). Although there was no significant difference in the transport rate for insulin in the hypothalamus (Table 1), there was a significantly lower level of vascular binding of insulin due to exercise in females (Table 1, Sedentary Vi = 2.9 ± 6.3 µL/g vs. Exercise Vi = 1.1 ± 2.2 µL/g, P = 0.004).

Acute Exercise and Insulin Uptake by Brain Regions

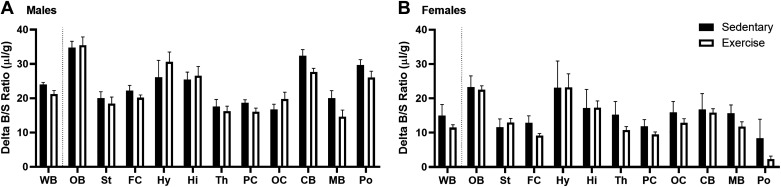

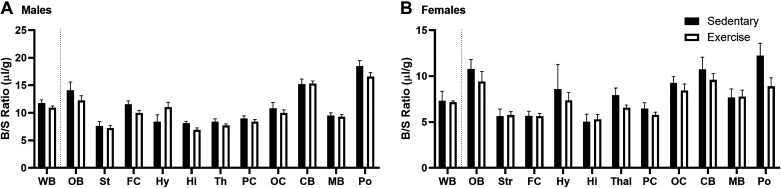

We next looked to see if there were regional differences in the uptake of insulin at a single time point within the linear range of brain uptake, 5 min, similar to previous studies (26). We observed similar regional differences in the uptake of insulin as has been reported previously (26). Exercise did not affect regional uptake at this single time point in males (Fig. 3A). There was a significant effect on regional uptake due to acute exercise in females [Fig. 3B, F(1,192) = 4.226, P = 0.0412] with no post hoc differences.

Figure 3.

Effects of acute exercise on regional insulin uptake (5 min time point). A: exercise had no effect on 125I-insulin levels in males (two-way ANOVA: P = 0.1305). B: exercise had an effect on 125I-insulin levels in females (two-way ANOVA: P = 0.0412 with no post hoc differences). Means are reported ± SE. Distance run reported in means ± SE: males = 2.6 ± 0.7 km, females = 4.7 ± 1.2 km; n = 7–11/region. CB, cerebellum; FC, frontal cortex; Hi, hippocampus; Hy, hypothalamus; MB, midbrain; OB, olfactory bulb; OC, occipital cortex; PC, parietal cortex; Po, pons/medulla; St, striatum; Th, thalamus; WB, whole brain.

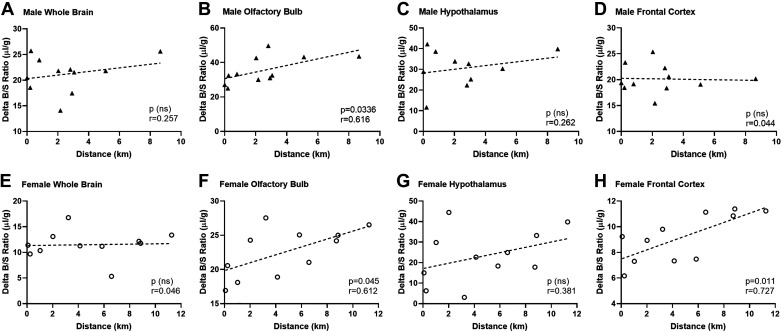

Correlation between Acute Exercise and Insulin Uptake by Brain

Mice have varied responses to the running wheels and therefore, run for different lengths. For males, the range in distance was from 0.006 to 8.7 km. For females, the range was from 0.03 to 13.1 km. There was no correlation between insulin uptake (delta B/S ratio) and speed (m/min) (data not shown). To determine whether there was a relationship between insulin brain uptake from Fig. 3 and distance run, we performed correlation analyses for the two variables (Fig. 4). In whole brain, there was no correlation (Fig. 4, A and E). However, in males and females there was a significant positive correlation in the olfactory bulb between the amount of insulin uptake (delta B/S ratio) and the distance run (Fig. 4, B and F, males: r = 0.616, P = 0.0336; females: r = 0.612, P = 0.045). In females, there was also a significant correlation in insulin uptake in the frontal cortex (Fig. 4H, r = 0.727, P = 0.010). In hypothalamus, there was no correlation (Fig. 4, C and G). For all other brain regions, there was no correlation (P > 0.05, data not shown).

Figure 4.

Pearson correlations on run distance (km) and delta insulin B/S ratios (µL/g). The correlation between run distance and brain insulin uptake was compared in whole brain (A and E), olfactory bulb (B and F), hypothalamus (C and G), and frontal cortex (D and H). Males are presented in the top row (A–D) and females are in the bottom row (E–H). B and F: olfactory bulb insulin levels significantly correlated with running distance in both males (P = 0.034) and females (P = 0.045). H: in females, there was also a correlation in the frontal cortex (P = 0.01). Distance run reported in means ± SE: males = 2.6 ± 0.7 km, females = 4.7 ± 1.2 km.

Regional Vascular Space

Although exercise did not affect the uptake rate of 99mTc/131I-albumin, we did find that acute exercise impacted the vascular space as measured by 99mTc-albumin levels in males [Fig. 5A, F(1,208) = 4.973, P = 0. 0268] and females [Fig. 5B, F(1,172) = 5.504, P = 0.02], with no post hoc differences. There were regional differences in vascular space in both males [F(11,208) = 43.51, P < 0.0001] and females [F(11,172) = 10.11, P < 0.0001], as expected. Since brain vascular space can change with exercise due to vasodilation, we investigated correlations between the vascular space of each brain region and running distance. There was only a significant correlation in females in the thalamus (P = 0.021, data not shown).

Figure 5.

Effects of acute exercise on vascular space (99mTc-albumin levels). Exercise had a significant effect on 99mTc-albumin levels in males (A) (two-way ANOVA: P = 0.0268) and females (B) (two-way ANOVA: P = 0.0201) with no post hoc differences. Means are reported ± SE. Distance run reported in means ± SE: males = 2.6 ± 0.7 km, females = 4.7 ± 1.2 km; n = 7–11/region.

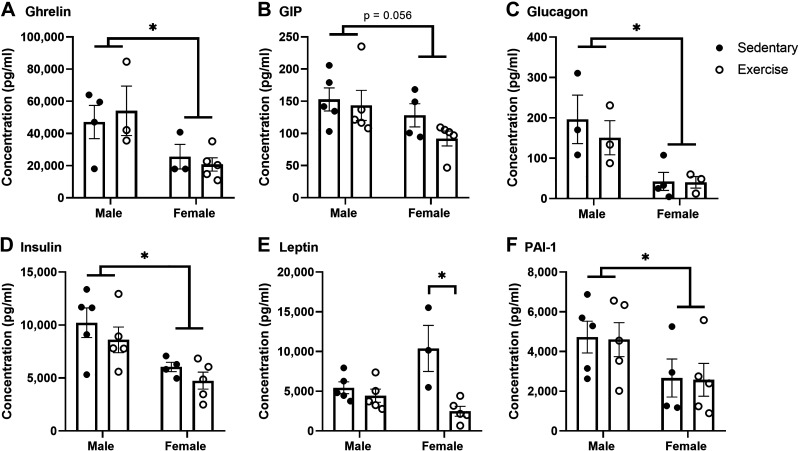

Impact of Acute Exercise on Serum Metabolic Factors

Levels of certain metabolic serum factors are known to affect insulin transport across the BBB (i.e., insulin itself can inhibit 125I-insulin BBB transport). To determine if the differences in insulin uptake due to acute exercise were due to changes in metabolic serum factors, we measured an array of factors using a diabetes multiplex in nonfasted mice. We observed significant differences in serum levels due to sex, specifically in ghrelin, glucagon, insulin, and PAI-1 levels (Fig. 6). However, there was no effect of exercise on serum levels of these hormones. There was a significant interaction between exercise and sex for leptin levels [F(1,14) = 8.572, P = 0.001] and levels were significantly lower due to acute exercise in females [F(1,14) = 14.35, P = 0.002]. GLP-1 levels were too low to accurately measure and there were no differences due to sex or exercise for resistin (data not shown).

Figure 6.

Effects of acute exercise on nonfasted serum levels of metabolic hormones. Serum hormone levels including ghrelin (A), glucose-dependent insulinotropic peptide (GIP) (B), glucagon (C), insulin (D), leptin (E), and plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) (F) were measured. There were sex differences in the levels of ghrelin (A), glucagon (C), insulin (D), and PAI-1 (F). Acute exercise had a significant effect on leptin serum levels (E), with post hoc differences only in females (P = 0.0414). Means are reported ± SE. Two-way ANOVA: *P < 0.05 as marked. Distance run reported in means ± SE: males = 2.8 ± 1.3 km, females = 3.8 ± 1.7 km.

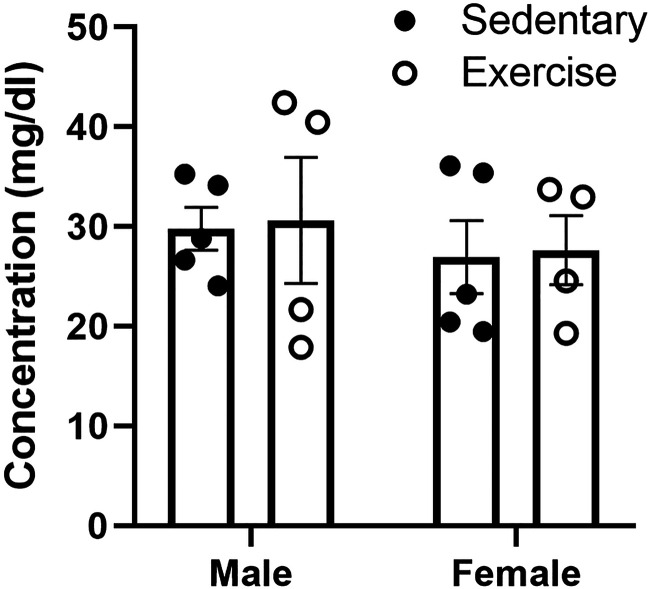

In addition, we measured levels of serum triglycerides since they can impair insulin BBB transport and subsequent CNS insulin receptor signaling response to insulin (10, 11). Although the males had arithmetically higher levels of serum triglycerides compared with females, there were no statistical differences due to sex or exercise (Fig. 7).

Figure 7.

Effects of exercise on serum triglyceride levels. Acute exercise did not have a significant effect on triglyceride levels in males or females. Means are reported ± SE. Distance run reported in means ± SE: males = 2.8 ± 1.3 km, females = 3.8 ± 1.7 km.

Impact of Acute Exercise on Insulin Receptor Signaling

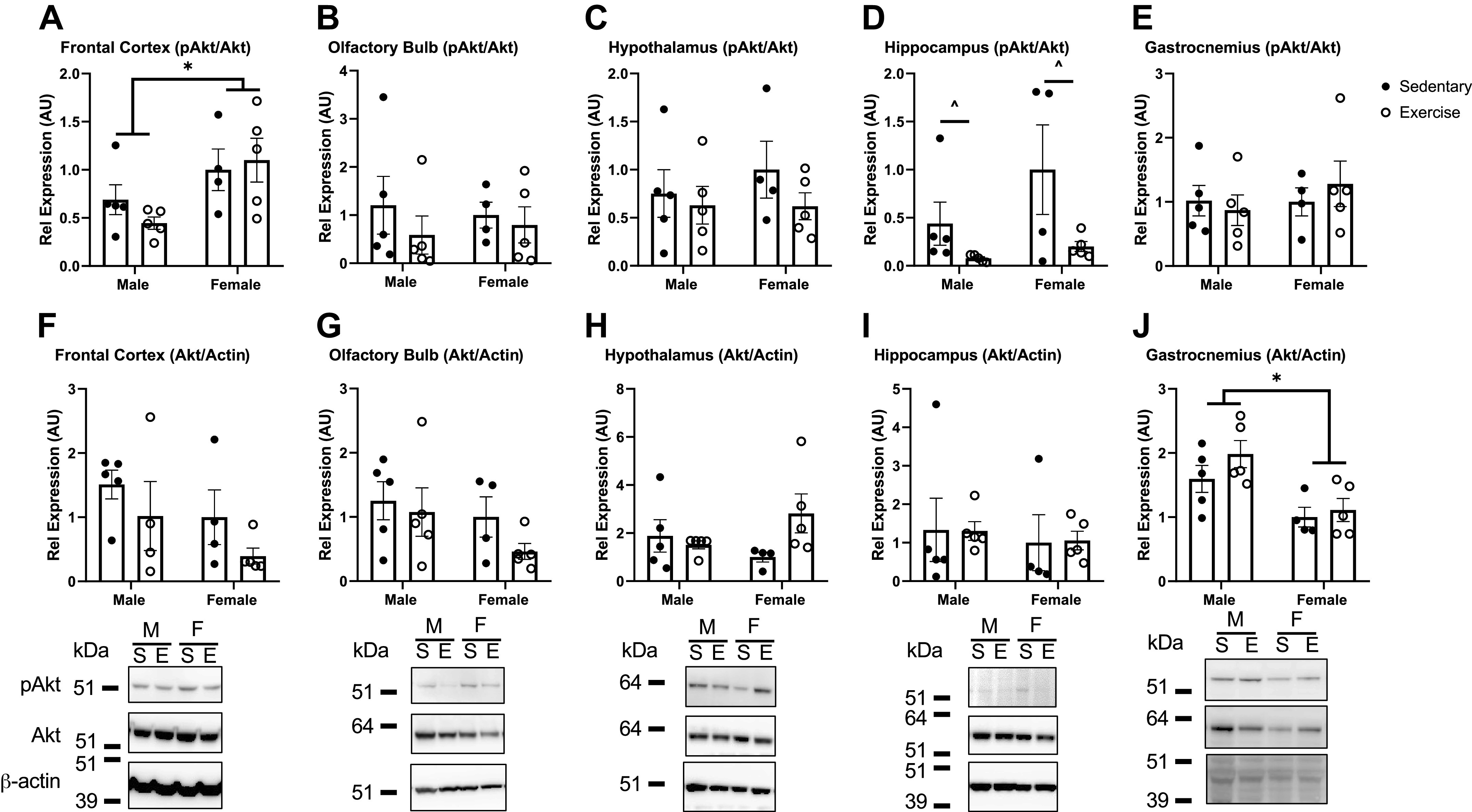

To investigate the basal downstream signaling of insulin receptor activation, we measured changes in the protein phosphorylation of Akt (pAkt). Levels of basal pAkt relative to total Akt were greater in females in the frontal cortex compared with males [Fig. 8A, F(1,15) = 7.674, P = 0.014], with no post hoc differences. In the hippocampus, levels of basal pAkt relative to total Akt were lower due to exercise [Fig. 8G, F(1,15) = 6.472, P = 0.023], with no post hoc differences. For olfactory bulb and the hypothalamus, there were no differences. We also investigated the effect of exercise on basal pAkt and Akt levels in gastrocnemius muscle. We found significantly lower levels of total Akt relative to β-actin in females compared with males [Fig. 8I, F(1,15) = 13.96, P = 0.002] but no effects due to acute exercise.

Figure 8.

Akt activation (phosphorylated Akt, pAkt) in response to acute exercise in select brain regions and gastrocnemius muscle. Top row: level of pAkt relative to total Akt. Bottom row: level of total Akt relative to β-actin levels. Levels present in frontal cortex (A and F), olfactory bulb (B and G), hypothalamus (C and H), hippocampus (D and I), and gastrocnemius (E and J) were investigated. n = 4 or 5/group. Means are reported ± SE. Two-way ANOVA: *P < 0.05 as marked, ^P < 0.05 within sex, due to exercise. Representative Western immunoblot images are shown below each brain region (M, male; F, female; S, sedentary; E, exercise). Distance run reported in means ± SE: males = 2.8 ± 1.3 km, females = 3.8 ± 1.7 km.

DISCUSSION

We show here that voluntary wheel running exercise can acutely impact insulin BBB interactions and CNS insulin signaling. Specifically, exercise enhanced insulin BBB transport by twofold into whole brain in male CD-1 mice. Exercise also enhanced the level of insulin vascular binding in the olfactory bulb in males and lowered the levels in the hypothalamus in females. The effects of exercise in females on insulin transport into whole brain were less robust. However, we did detect a significant effect of exercise in females on regional insulin uptake. The amount of distance run for each mouse correlated with olfactory bulb insulin uptake in both males and females and in frontal cortex insulin uptake in just females. These changes in insulin BBB transport are likely not attributable to changes in serum insulin or triglyceride levels as acute exercise did not alter these factors. Levels of the downstream CNS insulin receptor signaling mediator pAkt were lower in the hippocampus due to exercise in males and females. These data suggest acute exercise can impact insulin BBB interactions and CNS insulin receptor signaling in young, healthy mice.

This is the first report, to our knowledge, to show that insulin BBB transport is greater following exercise. Of the 2.3 ng insulin injected as the radioactive tracer, only 1.2 ng/mL insulin for males and 1.6 ng/mL insulin for females is present at time 0, which is a small percentage of the endogenous level of serum insulin. Therefore, we do not believe that the results from the insulin BBB transport studies are impacted by the amount of insulin injected as a radiotracer. It is interesting to observe that the robust changes in whole brain were only seen in males and not in females and require further investigation about the sexual dimorphic pattern. There were other sex differences in the response to exercise including vascular binding, regional uptake, correlations between distance run and insulin uptake or vascular space, and impact of exercise on serum leptin levels. There are known differences in not only metabolic regulation such as insulin sensitivity (30) but also the physiological response to exercise between males and females (31) that could be implicated in our observations. On the one hand, we did notice that females ran, on average, longer distances at faster speeds than males during the access to an unlocked running wheel. It is possible that females have a greater threshold for exhibiting alterations in insulin BBB transport in response to exercise, potentially related to the enhanced sensitivity to insulin in this sex or due to changes in an unknown serum factor in response to exercise. In addition, there was less time that lapsed between the last exercise bout and tissue collection in females. Since voluntary running wheel exercise is so variable, especially between males and females, further investigation of more controlled exercise, such as treadmill exercise at varying intensities, is warranted. Varying intensity of exercise is known to affect luminal vascular protein expression (32) that could be extended to changes in proteins responsible for insulin BBB transport. Using treadmills would allow us to investigate insulin BBB transport and CNS signaling at designated time points following exercise. On the other hand, similar sex effects due to exercise were observed in the level of insulin vascular binding. Exercise enhanced insulin vascular binding in the brain in both males (significantly) and females (trending toward significance). This suggests exercise can induce greater interactions between insulin and insulin binding sites at the BBB, such as changes in protein expression, cofactor interactions, or receptor-ligand interactions present at the BBB. Future studies will be designed to investigate protein localization changes and insulin at the BBB regarding insulin binding.

Acute, aerobic exercise can impact regional changes within the brain in both humans (33) as well as rodents (34). We additionally investigated brain region levels of 125I-insulin at a single time point (5 min) and found that they vary regionally, as has been reported earlier (26). There were no significant differences in the level of brain insulin due to exercise in males at this single time point. As we observed differences in the rate of transport into whole brain for males, collecting brain regions at various time points following radioactive insulin administration may be necessary to detect differences in insulin pharmacokinetics regionally. There were significant differences due to exercise in females, with no post hoc differences. As these brain region samples were collected at a single time point, we cannot differentiate between transport and binding. Follow-up studies combining full brain dissection and multiple-time regression analysis need to be performed to determine whether these differences are due to changes in the regional transport rate or due to vascular binding, as was suggested in the pharmacokinetic studies for females. Protein expression of other nutrient transporters at the BBB such as the monocarboxylate transporters (MCTs), the transport system for lactate, and glucose transporter 1 (GLUT1) are altered in a regional manner following an acute bout of exercise in male rodents (35). Using controlled treadmill exercise, this study also showed that serum concentrations of specific substrates are altered in a time-dependent manner following exercise. For example, free fatty acids, which are known to affect insulin BBB transport (10), did not increase until 30 min of exercise. The time with which these changes return to baseline after exercise were not defined. As our studies were performed on average ∼6–8 h following exercise, investigation of insulin BBB pharmacokinetics at various time points following exercise using controlled treadmills as described earlier could aid in understanding the underlying mechanism.

We additionally analyzed these regional samples collected at a single time point (5 min), to determine whether the level of transport of insulin in these brain regions corresponded with running distance for each animal. The olfactory bulb insulin uptake positively correlated with running distance in both males and females. This suggests a direct relationship between acute exercise volume and insulin uptake in this brain region. The frontal cortex also had a positive correlation between the insulin uptake level and running distance but in females only. Both of these regions are important for memory in rodents (36, 37). In this initial study, although we did not observe any effect of acute exercise on hippocampal insulin uptake, we did detect differences in pAkt protein expression due to exercise only in the hippocampus. Future studies will be necessary to investigate hippocampal insulin BBB pharmacokinetics in more detail and determine whether exercise increases the regional expression level of the insulin receptor or proteins involved in insulin transport at the BBB. As it is known that exercise can affect regional blood flow in the brain (33), which is often regulated by vascular space, we were able to compare the level of vascular space regionally in male and female mice following acute exercise. There were overall significant differences in the level of vascular space in both males and females between the regions. In addition, exercise significantly altered vascular space in both sexes, with no differences between sexes. It should be noted that insulin BBB transport is not flow-dependent, but rather regulated by a saturable transport system. Therefore, changes in vascular space are not likely contributing to the altered insulin BBB transport we are observing in males.

The present study showed no changes in serum insulin levels following acute exercise. Exercise can have beneficial effects on peripheral insulin resistance (9). As serum insulin concentration can affect insulin BBB transport due to the saturable nature of the insulin transporter (38), we showed the changes in the rate of insulin BBB transport were not due to changes in serum insulin levels. We did observe lower levels of serum leptin levels due to acute exercise but only in females. It has been suggested leptin levels can be decreased due to exercise promoting greater energy expenditure and that these decreases may be mediated by a diurnal pattern (39). As females ran further in our acute exercise paradigm compared with males, this could explain the reductions observed in only females. Regardless, it is thought leptin and insulin BBB transport systems are independent of one another (38) and is, therefore, likely, not a mechanism for changes in insulin BBB pharmacokinetics in our studies.

Acute exercise lowered phosphorylated Akt (pAkt), a primary mediator of insulin receptor signaling, in the hippocampus only. Previous work has also shown a decrease in the levels of pAkt in skeletal muscle following resistance exercise (40). It is possible the lowered pAkt observed in the hippocampus could be due to a semifasted state. Access to a voluntary running wheel can result in decreased food intake acutely (41). Fasting lowers basal Akt phosphorylation in the CNS (42). However, it is unusual that these reductions are only present in the hippocampal samples and requires further investigation. Aged Wistar rats exposed to 4 wk of treadmill exercise had increased pAkt brain levels compared with sedentary rats (43). There are reports suggesting exercise does not alter CNS insulin receptor signaling in healthy, young mice (44, 45). Instead, in one of the studies, improvements were only seen following chronic exercise in this signaling pathway when there was a CNS deficiency already present, using obese mice fed a high-fat diet (44). This data suggests a deficit may need to be present first within the CNS insulin receptor signaling pathway for exercise-mediated improvements. That is, the insulin receptor signaling pathway in the hippocampus is dampened in obese mice compared with lean controls, and exercise was able to restore these levels back to normal. This suggests that in the presence of CNS insulin resistance, exercise may be able to exert beneficial effects directly on CNS insulin receptor signaling. In addition, the impact of chronic exercise, in particular on CNS insulin receptor signaling, will help provide long-term implications for exercise related to insulin brain uptake and signaling. Future studies are needed to characterize the magnitude and mechanisms of the effect of acute exercise on insulin signaling, particularly in animal models with known CNS insulin resistance, as occurs in mouse models of AD.

Aging and the development of AD are linked to changes in the structure and function of the neurovascular unit, located at the BBB (46, 47). In the aging brain, exercise is able to preserve the cerebrovascular system that is known to deteriorate with age (48). Whether this effect includes favorable exercise-mediated changes at the BBB, and if extends to disease states with BBB dysfunction is unknown. It is possible that exercise could improve not only the structure of the BBB but also the function of the BBB in AD. Here, we have shown that there is a relationship between acute exercise and insulin BBB interactions. Future studies will investigate the impact of exercise in a mouse model of AD on insulin BBB interactions and CNS insulin receptor signaling, and how these effects may mediate known cognitive benefits of exercise for patients with this disease.

GRANTS

This research was funded by The Brown Foundation (to E.M.R.), the National Institute of Health Grants P30 DK017047-44 and P30 AG066509 (to E. M. R.); RF1AG059088 (to W. A. B.), and by the Veterans Affairs Puget Sound Health Care System Research and Development (to E. M. R. and W. A. B.).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

E.M.R. conceived and designed research; C.B., S.P., A.B., N.A., C.N., and E.M.R. performed experiments; C.B., S.P., A.B., N.A., and E.M.R. analyzed data; C.B., S.P., A.B., N.A., M.B.B., W.A.B., and E.M.R. interpreted results of experiments; C.B., S.P., A.B., N.A., and E.M.R. prepared figures; C.B., S.P., A.B., N.A., C.N., and E.M.R. drafted manuscript; C.B., S.P., A.B., N.A., C.N., M.B.B., W.A.B., and E.M.R. edited and revised manuscript; C.B., S.P., A.B., N.A., C.N., M.B.B., W.A.B., and E.M.R. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Graphical Abstract image created with BioRender and published with permission.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rhea EM, Banks WA. Role of the blood-brain barrier in central nervous system insulin resistance. Front Neurosci 13: 521, 2019. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2019.00521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Craft S, Peskind E, Schwartz MW, Schellenberg GD, Raskind M, Porte D Jr.. Cerebrospinal fluid and plasma insulin levels in Alzheimer’s disease: relationship to severity of dementia and apolipoprotein E genotype. Neurology 50: 164–168, 1998. doi: 10.1212/wnl.50.1.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Salameh TS, Bullock KM, Hujoel IA, Niehoff ML, Wolden-Hanson T, Kim J, Morley JE, Farr SA, Banks WA. Central nervous system delivery of intranasal insulin: mechanisms of uptake and effects on cognition. J Alzheimers Dis 47: 715–728, 2015. doi: 10.3233/JAD-150307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Freiherr J, Hallschmid M, Frey WH, Brünner YF, Chapman CD, Hölscher C, Craft S, De Felice FG, Benedict C. Intranasal insulin as a treatment for Alzheimer’s disease: a review of basic research and clinical evidence. CNS Drugs 27: 505–514, 2013. doi: 10.1007/s40263-013-0076-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benedict C, Hallschmid M, Hatke A, Schultes B, Fehm HL, Born J, Kern W. Intranasal insulin improves memory in humans. Psychoneuroendocrinology 29: 1326–1334, 2004. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2004.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vidoni ED, Johnson DK, Morris JK, Van Sciver A, Greer CS, Billinger SA, Donnelly JE, Burns JM. Dose-response of aerobic exercise on cognition: a community-based, pilot randomized controlled trial. PLoS One 10: e0131647, 2015. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0131647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baker LD, Frank LL, Foster-Schubert K, Green PS, Wilkinson CW, McTiernan A, Plymate SR, Fishel MA, Watson GS, Cholerton BA, Duncan GE, Mehta PD, Craft S. Effects of aerobic exercise on mild cognitive impairment: a controlled trial. Arch Neurol 67: 71–79, 2010. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2009.307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Horowitz AM, Fan X, Bieri G, Smith LK, Sanchez-Diaz CI, Schroer AB, Gontier G, Casaletto KB, Kramer JH, Williams KE, Villeda SA. Blood factors transfer beneficial effects of exercise on neurogenesis and cognition to the aged brain. Science 369: 167–173, 2020. doi: 10.1126/science.aaw2622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Henriksen EJ. Invited review: Effects of acute exercise and exercise training on insulin resistance. J Appl Physiol (1985) 93: 788–796, 2002. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01219.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Urayama A, Banks WA. Starvation and triglycerides reverse the obesity-induced impairment of insulin transport at the blood-brain barrier. Endocrinology 149: 3592–3597, 2008. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-0008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Banks WA, Farr SA, Salameh TS, Niehoff ML, Rhea EM, Morley JE, Hanson AJ, Hansen KM, Craft S. Triglycerides cross the blood-brain barrier and induce central leptin and insulin receptor resistance. Int J Obes (Lond) 42: 391–397, 2018. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2017.231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Islam MR, Valaris S, Young MF, Haley EB, Luo R, Bond SF, Mazuera S, Kitchen RR, Caldarone BJ, Bettio LEB, Christie BR, Schmider AB, Soberman RJ, Besnard A, Jedrychowski MP, Kim H, Tu H, Kim E, Choi SH, Tanzi RE, Spiegelman BM, Wrann CD. Exercise hormone irisin is a critical regulator of cognitive function. Nat Metab 3: 1058–1070, 2021. [Erratum in Nat Metab 3: 1432, 2021]. doi: 10.1038/s42255-021-00438-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lourenco MV, Frozza RL, de Freitas GB, Zhang H, Kincheski GC, Ribeiro FC, Goncalves RA, Clarke JR, Beckman D, Staniszewski A, Berman H, Guerra LA, Forny-Germano L, Meier S, Wilcock DM, de Souza JM, Alves-Leon S, Prado VF, Prado MAM, Abisambra JF, Tovar-Moll F, Mattos P, Arancio O, Ferreira ST, De Felice FG. Exercise-linked FNDC5/irisin rescues synaptic plasticity and memory defects in Alzheimer’s models. Nat Med 25: 165–175, 2019. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0275-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brunelli A, Dimauro I, Sgro P, Emerenziani GP, Magi F, Baldari C, Guidetti L, Di Luigi L, Parisi P, Caporossi D. Acute exercise modulates BDNF and pro-BDNF protein content in immune cells. Med Sci Sports Exerc 44: 1871–1880, 2012. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31825ab69b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pedersen BK. Physical activity and muscle-brain crosstalk. Nat Rev Endocrinol 15: 383–392, 2019. doi: 10.1038/s41574-019-0174-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Małkiewicz MA, Małecki A, Toborek M, Szarmach A, Winklewski PJ. Substances of abuse and the blood brain barrier: interactions with physical exercise. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 119: 204–216, 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2020.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Małkiewicz MA, Szarmach A, Sabisz A, Cubała WJ, Szurowska E, Winklewski PJ. Blood-brain barrier permeability and physical exercise. J Neuroinflammation 16: 15, 2019. doi: 10.1186/s12974-019-1403-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.He XF, Liu DX, Zhang Q, Liang FY, Dai GY, Zeng JS, Pei Z, Xu GQ, Lan Y. Voluntary exercise promotes glymphatic clearance of amyloid β and reduces the activation of astrocytes and microglia in aged mice. Front Mol Neurosci 10: 144, 2017. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2017.00144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Robinson MM, Lowe VJ, Nair KS. Increased brain glucose uptake after 12 weeks of aerobic high-intensity interval training in young and older adults. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 103: 221–227, 2018. doi: 10.1210/jc.2017-01571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kemppainen J, Aalto S, Fujimoto T, Kalliokoski KK, Langsjo J, Oikonen V, Rinne J, Nuutila P, Knuuti J. High intensity exercise decreases global brain glucose uptake in humans. J Physiol 568: 323–332, 2005. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.091355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goh J, Ladiges W. Voluntary wheel running in mice. Curr Protoc Mouse Biol 5: 283–290, 2015. doi: 10.1002/9780470942390.mo140295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.American physiological society committee to develop an APS resource book for the design of animal exercise protocols. Resource Book for the Design of Animal Exercise Protocols. Bethesda, MD: American Physiological Society, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Poole DC, Copp SW, Colburn TD, Craig JC, Allen DL, Sturek M, O’Leary DS, Zucker IH, Musch TI. Guidelines for animal exercise and training protocols for cardiovascular studies. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 318: H1100–H1138, 2020. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00697.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Manzanares G, Brito-da-Silva G, Gandra PG. Voluntary wheel running: patterns and physiological effects in mice. Braz J Med Biol Res 52: e7830, 2018. doi: 10.1590/1414-431X20187830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nguyen S, Banks WA, Rhea EM. Effects of rapamycin on insulin brain endothelial cell binding and blood-brain barrier transport. Med Sci (Basel) 9: 56, 2021. doi: 10.3390/medsci9030056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rhea EM, Rask-Madsen C, Banks WA. Insulin transport across the blood-brain barrier can occur independently of the insulin receptor. J Physiol 596: 4753–4765, 2018. doi: 10.1113/JP276149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blasberg RG, Fenstermacher JD, Patlak CS. Transport of alpha-aminoisobutyric acid across brain capillary and cellular membranes. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 3: 8–32, 1983. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1983.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Patlak CS, Blasberg RG, Fenstermacher JD. Graphical evaluation of blood-to-brain transfer constants from multiple-time uptake data. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 3: 1–7, 1983. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1983.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Glowinski J, Iversen LL. Regional studies of catecholamines in the rat brain. I. The disposition of [3H]norepinephrine, [3H]dopamine and [3H]dopa in various regions of the brain. J Neurochem 13: 655–669, 1966. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1966.tb09873.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tramunt B, Smati S, Grandgeorge N, Lenfant F, Arnal JF, Montagner A, Gourdy P. Sex differences in metabolic regulation and diabetes susceptibility. Diabetologia 63: 453–461, 2020. doi: 10.1007/s00125-019-05040-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ansdell P, Thomas K, Hicks KM, Hunter SK, Howatson G, Goodall S. Physiological sex differences affect the integrative response to exercise: acute and chronic implications. Exp Physiol 105: 2007–2021, 2020. doi: 10.1113/EP088548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gliemann L, Rytter N, Piil P, Nilton J, Lind T, Nyberg M, Cocks M, Hellsten Y. The endothelial mechanotransduction protein platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 is influenced by aging and exercise training in human skeletal muscle. Front Physiol 9: 1807, 2018. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2018.01807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.MacIntosh BJ, Crane DE, Sage MD, Rajab AS, Donahue MJ, McIlroy WE, Middleton LE. Impact of a single bout of aerobic exercise on regional brain perfusion and activation responses in healthy young adults. PLoS One 9: e85163, 2014. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0085163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morgan JA, Corrigan F, Baune BT. Effects of physical exercise on central nervous system functions: a review of brain region specific adaptations. J Mol Psychiatry 3: 3, 2015. doi: 10.1186/s40303-015-0010-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Takimoto M, Hamada T. Acute exercise increases brain region-specific expression of MCT1, MCT2, MCT4, GLUT1, and COX IV proteins. J Appl Physiol (1985) 116: 1238–1250, 2014. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01288.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mouly AM, Sullivan R. Memory and plasticity in the olfactory system: from infancy to adulthood. In: The Neurobiology of Olfaction, edited by Menini A. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press/Taylor & Francis, 2010, chapt. 15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mitchell JB, Laiacona J. The medial frontal cortex and temporal memory: tests using spontaneous exploratory behaviour in the rat. Behav Brain Res 97: 107–113, 1998. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(98)00032-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Banks WA, Jaspan JB, Huang W, Kastin AJ. Transport of insulin across the blood-brain barrier: saturability at euglycemic doses of insulin. Peptides 18: 1423–1429, 1997. doi: 10.1016/s0196-9781(97)00231-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bouassida A, Zalleg D, Bouassida S, Zaouali M, Feki Y, Zbidi A, Tabka Z. Leptin, its implication in physical exercise and training: a short review. J Sports Sci Med 5: 172–181, 2006. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Deldicque L, Atherton P, Patel R, Theisen D, Nielens H, Rennie MJ, Francaux M. Decrease in Akt/PKB signalling in human skeletal muscle by resistance exercise. Eur J Appl Physiol 104: 57–65, 2008. doi: 10.1007/s00421-008-0786-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.O’Neal TJ, Friend DM, Guo J, Hall KD, Kravitz AV. Increases in physical activity result in diminishing increments in daily energy expenditure in mice. Curr Biol 27: 423–430, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2016.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Clodfelder-Miller B, De Sarno P, Zmijewska AA, Song L, Jope RS. Physiological and pathological changes in glucose regulate brain Akt and glycogen synthase kinase-3. J Biol Chem 280: 39723–39731, 2005. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508824200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Aguiar AS Jr, Castro AA, Moreira EL, Glaser V, Santos AR, Tasca CI, Latini A, Prediger RD. Short bouts of mild-intensity physical exercise improve spatial learning and memory in aging rats: involvement of hippocampal plasticity via AKT, CREB and BDNF signaling. Mech Ageing Dev 132: 560–567, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2011.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Park HS, Park SS, Kim CJ, Shin MS, Kim TW. Exercise alleviates cognitive functions by enhancing hippocampal insulin signaling and neuroplasticity in high-fat diet-induced obesity. Nutrients 11: 1603, 2019. doi: 10.3390/nu11071603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wojtaszewski JF, Hansen BF, Kiens B, Richter EA. Insulin signaling in human skeletal muscle: time course and effect of exercise. Diabetes 46: 1775–1781, 1997. doi: 10.2337/diab.46.11.1775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Banks WA, Reed MJ, Logsdon AF, Rhea EM, Erickson MA. Healthy aging and the blood-brain barrier. Nat Aging 1: 243–254, 2021. doi: 10.1038/s43587-021-00043-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nation DA, Sweeney MD, Montagne A, Sagare AP, D’Orazio LM, Pachicano M, Sepehrband F, Nelson AR, Buennagel DP, Harrington MG, Benzinger TLS, Fagan AM, Ringman JM, Schneider LS, Morris JC, Chui HC, Law M, Toga AW, Zlokovic BV. Blood-brain barrier breakdown is an early biomarker of human cognitive dysfunction. Nat Med 25: 270–276, 2019. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0297-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Soto I, Graham LC, Richter HJ, Simeone SN, Radell JE, Grabowska W, Funkhouser WK, Howell MC, Howell GR. APOE stabilization by exercise prevents aging neurovascular dysfunction and complement induction. PLoS Biol 13: e1002279, 2015. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1002279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]