Abstract

Background.

The link between posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and ischemic heart disease remains elusive due to a shortage of longitudinal studies with a clinical diagnosis of PTSD and objective measures of cardiac compromise.

Methods.

We performed positron emission tomography (PET) in 275 twins who participated in two examinations approximately 12 years apart. At both visits we obtained a clinical diagnosis of PTSD which was classified as longstanding (both visit 1 and visit 2), late onset (only visit 2) and no PTSD (no PTSD at both visits). With PET we assessed myocardial flow reserve (MFR) which, in absence of significant coronary stenoses, indexes coronary microvascular function. We compared PET data at Visit 2 across the 3 categories of longitudinally-assessed PTSD, and examined changes between the two visits.

Results.

Overall 80% of twins had no or minimal obstructive coronary disease. Yet, MFR was depressed in twins with PTSD, and was progressively lower across groups of no PTSD (2.13), late-onset PTSD (1.97), and longstanding PTSD (1.93), p=0.01. A low MFR (a ratio <2.0) was present in 40% of twins without PTSD, 56% in late-onset PTSD, and 72% in longstanding PTSD (p<0.001). Associations persisted in multivariable analysis, when examining changes in MFR between Visit 1 and Visit 2, and within twin pairs. Results were similar by zygosity.

Conclusions.

Longitudinally, PTSD is associated with reduced coronary microcirculatory function and greater deterioration over time. The association is especially noted among twins with chronic, longstanding PTSD, and is not confounded by shared environmental or genetic factors.

Keywords: Posttraumatic Stress Disorder, cardiovascular disease, twins, positron emission tomography, myocardial ischemia, epidemiology

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) is a chronic disabling psychiatric condition which is common among military personnel, but also prevalent in the general population.1 Of growing concern is a possible causal role of PTSD on ischemic heart disease,2,3 but evidence for a causal link remains limited. There is a paucity of prospective studies that have used objective measures of heart disease, as most investigations have defined cardiovascular outcomes using diagnostic codes or death certificates.3-6 PTSD has also often been defined by diagnostic codes.3,5,6 Furthermore, the mechanisms for this increased risk remain unknown.7

A possible, yet unappreciated potential mechanism linking PTSD to ischemic heart disease is coronary microvascular dysfunction, which can reduce myocardial blood flow and cause myocardial ischemia through a microcirculatory mechanism.8,9 This phenomenon is associated with approximately a twofold increase in the risk of cardiovascular events independent of coronary stenoses,10 and endothelial dysfunction, inflammation or other structural or functional abnormalities of the microcirculation are contributing factors.8,9,11 Individuals with PTSD have enhanced sensitivity of the noradrenergic system to stress with increased sympathetic nervous system activation during trauma reminders.12-14 In the long-term, immune activation in combination with endothelial injury could lead to coronary microvascular dysfunction.8,11,15 Clarification of whether the microcirculation plays a role in the connection of PTSD with ischemic heart disease would have important clinical implications.

The association between PTSD and ischemic heart disease could be confounded by unmeasured familial factors, i.e., shared genetic and environmental factors that are related to both PTSD and cardiovascular disease. The study of twins allows to control by design for familial confounding, because twin siblings share genes (50%, on average, if dizygotic, and all if monozygotic), maternal factors, and early familial environment. We have previously published the results of a study of PTSD and ischemic heart disease in 281 middle-aged male twin pairs from the Vietnam Era Twin (VET) Registry.16 Twins were assessed for ischemic heart disease using myocardial perfusion imaging with positron emission tomography (PET). We found that twins with PTSD had worse myocardial perfusion and coronary microvascular function using PET compared with twins without PTSD.16 Although compelling, that study was limited by the lack of longitudinal data for both PET imaging and PTSD, which would provide insight into a causal relationship by allowing objective examination of ischemic heart disease progression in relation to PTSD status as well as PTSD duration over time.

We have now completed a follow-up of this cohort and re-examined twins over a decade after their initial assessment with PET imaging. The purpose of the present study is to examine a potential causal pathway between PTSD and ischemic heart disease by examining myocardial perfusion and coronary microvascular function as they relate to PTSD status and its longitudinal course from baseline. Our hypothesis was that PTSD, especially chronic longstanding PTSD, is associated with indicators of ischemic heart disease using PET imaging, and that abnormal coronary microcirculatory function would be especially implicated.

Methods

Study Cohort

The present study is based on a follow-up of the Emory Twin Study.16 Twin participants at baseline were selected from the Vietnam Era Twin (VET) Registry, a large national sample of adult male twins who served on active duty during the Vietnam war era (1964-1975).17 Participants at baseline included 283 monozygotic (MZ) and dizygotic (DZ) twin pairs where at least one member of the pair had PTSD or major depression along with control pairs without these conditions. Of these, 275 twins underwent a second in-person evaluation on average 12 years after baseline, and had complete PET imaging data. Figure 1 shows the construction of the study population.

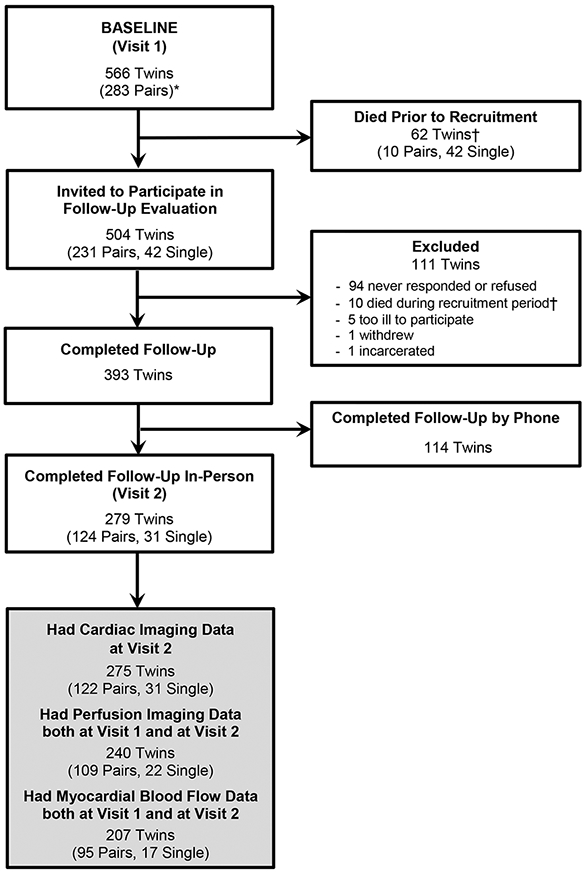

Figure 1.

Participant flow diagram and construction of the analytical sample. The baseline assessment (Visit 1) included 283 twin pairs without a history of cardiovascular disease based on Registry surveys. Visit 1 was completed between 2002 and 2010 and included myocardial perfusion imaging with positron emission tomography (PET). From this sample we invited 504 twins who were still alive (252 pairs) to participate in a follow-up evaluation, which was completed in person or over the phone (for those who were not able to travel) on average 12 years after Visit 1. A total of 393 twins participated in the follow-up study (78%), and among them, 279 twins (including 124 pairs and 31 single twins) completed the in-person visit, when cardiac imaging with PET was repeated (Visit 2). Of the 279 participants in the in-person Visit 2, 275 twins (122 twin pairs and 31 single twins) had complete PET imaging data and represent our main analytical sample. Of these, 240 twins had both Visit 1 and Visit 2 perfusion data and 207 twins (95 pairs and 17 single) had quantitative PET data of MBF at both visits.

* Two twin pairs were added to the database after the original publication based on 281 twin pairs.

† Of the 72 twins who died either prior to recruitment or during recruitment, 17 died of cardiovascular disease, 21 died of cancer, and the rest died of miscellaneous other causes or the cause of death was unknown.

Twin pairs participated together on the same day for both in-person visits to minimize measurement error. All twins signed a written informed consent, and the Emory University institutional review board approved the study.

Measurement of PTSD

At both Visit 1 and Visit 2 we obtained a clinical diagnosis of PTSD using the Structured Clinical Interview for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition (DSM-IV).18 Following the PTSD diagnostic algorithm, PTSD was classified as either current (met criteria in previous month) or past (did not meet criteria in previous month), and both current and past diagnoses were included in the definition of lifetime history of PTSD. Using these data we constructed classification variables to capture the clinical course of the condition. Twins were classified as not having had PTSD (not meeting criteria of lifetime history at both Visit 1 and Visit 2); as having a late-onset PTSD (not meeting criteria at Visit 1 but meeting criteria at Visit 2); and as having longstanding PTSD (meeting criteria at both Visit 1 and Visit 2). Only six twins met criteria for lifetime history of PTSD at Visit 1 but not at Visit 2. Given this small number, these were considered a measurement error and included in the group of “No PTSD,” although when considered as a separate category, results remained similar. This classification based on lifetime history was the main exposure variable in our analysis, since it may better capture the burden of chronic PTSD over time, and because relatively few twins at each visit met criteria for current PTSD. However, in exploratory analyses we constructed an alternative classification which considered current PTSD status (Figure 2).

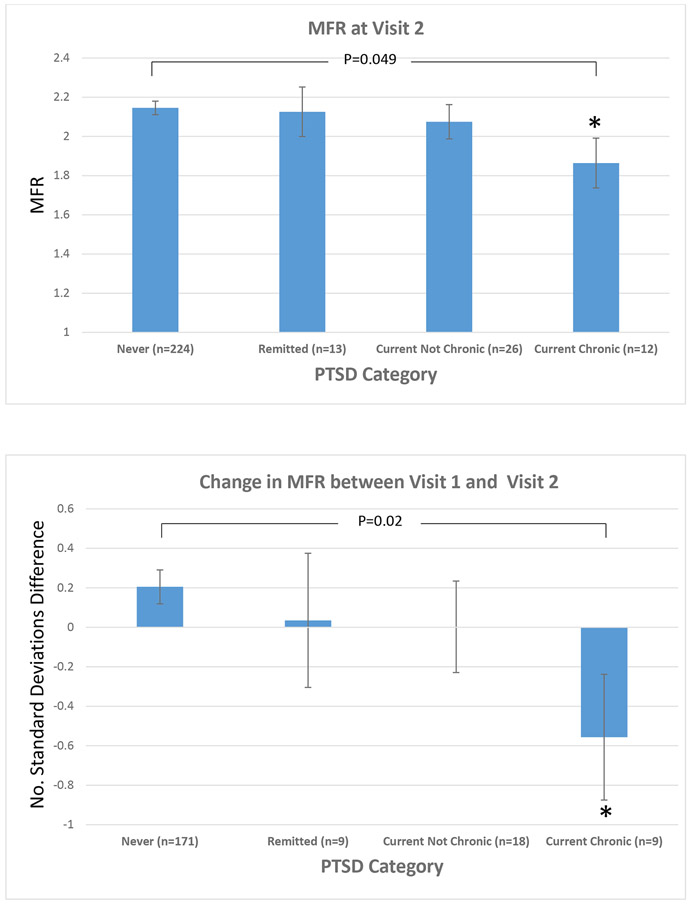

Figure 2.

Association between myocardial flow reserve and PTSD status assessed longitudinally taking into account current PTSD status at each time point. Never PTSD: no lifetime or current PTSD at Visit 1 and no current PTSD at Visit 2. Remitted PTSD: lifetime or current PTSD at Visit 1 and no current PTSD at Visit 2. Current, Not Chronic PTSD: no current PTSD at Visit 1 but current PTSD at Visit 2. Current, Chronic PTSD: current PTSD at both Visit 1 and Visit 2.

Top Panel: Mean (± standard error) myocardial flow reserve at visit 2.

Bottom Panel: Mean (± standard error) change in myocardial flow reserve between Visit 1 and Visit 2, expressed as number of standard deviations (a negative value indicated a decline in MFR). All data adjusted for age, current and past smoking, BMI, physical activity (Baecke score), history of hypertension, history of coronary disease, and statin use. All models for the analysis of change in MFR also adjusted for Visit 1 MFR.

Abbreviations: PTSD: posttraumatic stress disorder; MFR: myocardial flow reserve.

* p<0.05 compared with No PTSD

Measurement of Myocardial Perfusion and Coronary Flow Reserve

At Visit 1, twins underwent myocardial perfusion imaging with PET using [13N] ammonia at rest and following pharmacologic (adenosine) stress during a single imaging session using a CTI ECAT 921 camera (Siemens, Knoxville, Tennessee) in 2-dimensional mode.11 At Visit 2, [13N] ammonia was no longer offered for cardiac imaging studies at our institution. Therefore, twins underwent [82Rb]-chloride myocardial perfusion imaging at rest and following pharmacologic stress using regadenoson, an analogue of adenosine, again during a single imaging session using a Biograph PET/CT (Siemens, Knoxville, Tennessee) in 3-dimensional mode. The reproducibility of [82Rb] PET for myocardial blood flow quantitation and its accuracy in comparison with [13N] ammonia PET are excellent.19 At both visits twins were admitted overnight in the research facility on the day prior to the PET scan, and were instructed to abstain from smoking, from drinking alcoholic or caffeinated beverages and all medications were held the morning of the PET scan. Blood pressure and heart rate were recorded before administering the pharmacological agent, and every minute for 4 minutes during the stress test. The peak rate-pressure product during stress was calculated as the maximum systolic blood pressure times the maximum heart rate.

An experienced nuclear medicine physician (VM) performed semiquantitative visual interpretation of the imaging studies for the assessment of obstructive coronary artery disease,20 blinded to clinical data. We calculated summed scores in a conventional fashion, including a summed stress score, a summed rest score, and a summed difference score.20 Scans with a summed stress score ≤ 3 were considered normal.20 The percentage of abnormal myocardium was computed from the summed stress score, divided by 68 and multiplied by 100.21 Rest and stress left ventricular ejection fraction was calculated from gated myocardial perfusion images using the Emory Cardiac Toolbox.22

We performed myocardial blood flow (MBF) quantitation for the assessment of myocardial flow reserve (MFR), an index of coronary vasodilator capacity that is an accepted measure of coronary microvascular function if there are no obstructive coronary lesions.23,24 To calculate MFR, measurements of MBF at rest and during peak hyperemia were obtained using clinically accepted models corrected for radiotracer extraction fraction.25,26 Our main outcome was the overall measure of MFR for the entire myocardium, defined as the ratio of maximum flow during hyperemia to flow at rest. We also examined abnormal MFR, defined as a MFR of 2 or below, which has prognostic significance27,28 and has been used as a definition of coronary microvascular dysfunction.27 Moreover, we considered the three major coronary territories separately: left anterior descending, left circumflex, and right coronary artery. We calculated the relative flow reserve as the ratio of peak hyperemic flow in each territory divided by the peak hyperemic flow across all territories combined, as the reference.29 The relative flow reserve is a functional measure of flow-limiting coronary lesions; a relative flow reserve < 0.8 indicates significant flow-limiting disease.29,30

Other Measurements

At each visit, we performed a thorough assessment including medical history, sociodemographic information, health behaviors, blood pressure, anthropometric data and current medications, as previously described.11 Physical activity was measured using the Baecke Questionnaire of Habitual Physical Activity.31 History of coronary artery disease that might have occurred from the time of the initial screen, was defined as a previous diagnosis of myocardial infarction or coronary revascularization procedures. Experience of chest pain/angina symptoms in past 4 weeks was derived by the Seattle Angina Questionnaire.32 The SCID administration allowed us to assess lifetime history of major depression and substance abuse in addition to PTSD. Service in Southeast Asia was determined from military records. Zygosity information was assessed by DNA typing as previously described.33

Statistical Analysis

We compared participants’ characteristics based on 3 categories describing longitudinal changes in PTSD as described above: no PTSD, late-onset PTSD, and longstanding PTSD. We used generalized estimating equation models for categorical variables and mixed effects models for continuous variables with a random intercept for each pair.34 Because of the attrition in study participation between Visit 1 and Visit 2, we compared key baseline variables between twins who participated in both visits and those who only participated in Visit 1.

Next, we compared PET data across the 3 categories of PTSD. Because of highly skewed summed stress and rest perfusion scores with few twins showing abnormalities, we compared the percentage of twins with normal scans (summed stress score ≤ 3, indicating < 5% abnormal myocardium20) in addition to the total distribution of the percent of abnormal myocardium.

The association between PTSD and MFR was first examined by comparing MFR at Visit 2 across the three categories of PTSD. Next, we examined changes in MFR between Visit 1 and Visit 2 as a function of PTSD category. Given the different PET scan methodology between the 2 visits, the MFR measurements at each visit were converted to z scores and the difference in the z score between the two visits (Visit 2 minus Visit 1) was used as outcome. Analyses were adjusted for factors selected a priori, including age, lifestyle and cardiovascular risk factors (BMI, smoking, physical activity, hypertension, previous history of coronary disease and current statin use). In subsequent models, we adjusted for the summed stress score as a measure of epicardial coronary stenoses, and lifetime history of major depression. Additional variables, including use of other medications (beta-blockers, aspirin, ace-inhibitors and antidepressants), history of alcohol and drug abuse, alcohol consumption, service in Southeast Asia, resting heart rate and peak rate-pressure product during the stress test, were adjusted for in sensitivity analyses but ultimately not included in the main model to avoid overfitting, since their inclusion did not materially change the results. For the analysis of change in MFR from Visit 1 to Visit 2, we further adjusted for MFR at Visit 1.

All the analyses were conducted first in twins as individuals, and next within twin pairs discordant for PTSD category, including, in separate analyses, those discordant for lifetime PTSD status at Visit 2, and those discordant for longitudinal changes in PTSD across the two visits. The within-pair associations are inherently controlled for demographic, shared familial and early environmental influences; in addition, environmental factors during the examination day were controlled by design since twin pairs were examined together.35 We used mixed models for twin studies, where the within-pair effect was defined as the departure of each twin from the pair average.36 To assess potential shared genetic influence on PTSD status and MFR, we tested the interaction by zygosity.

Missing data were rare (<5%), thus we used all available data without imputation. A two-sided p-value of less than 0.05 was used for statistical significance and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated from model parameters. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Of the 275 twins who participated in person in Visit 2 and had complete PET myocardial perfusion imaging data, 212 never had PTSD, 34 had late-onset PTSD, and 29 had longstanding PTSD. The mean age was 68 years across all three groups (Table 1). Twins with PTSD, especially those with longstanding PTSD, were less likely to be married and employed and more likely to have served in Southeast Asia. Differences in behavioral factors and medical history were minor across the three groups, except that those with PTSD tended to report more chest pain symptoms, had a higher prevalence of other psychiatric diagnoses and were less likely to be taking medications for cardiovascular disease prevention compared with twins who never had PTSD.

Table 1.

Socio-demographic, military service, lifestyle, and cardiovascular disease risk factors at Visit 2, by lifetime PTSD status assessed longitudinally.

|

No PTSD N =212 |

Late-Onset PTSD N =34 |

Longstanding PTSD N=29 |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic Factors | |||

| Age, yrs, mean (SD) | 68 (3) | 68 (2) | 68 (1) |

| Non-white, % | 3.3 | 6.1 | 0 |

| Married, % | 80 | 67 | 55 |

| Years of education, mean (SD) | 14 (2) | 13 (2) | 13 (2) |

| Employed full time, % | 24 | 15 | 17 |

| Service in Southeast Asia, % | 36 | 62 | 86 |

| Lifestyle Factors | |||

| Cigarette Smoking, % | |||

| Never | 39 | 23 | 34 |

| Former | 47 | 62 | 48 |

| Current | 15 | 15 | 17 |

| Physical Activity (Baecke Score) | 7.9 (1.4) | 7.7 (1.5) | 8.5 (1.1) |

| Number of alcoholic drinks in average week in past 30 days, mean (SD) | 5.1 (10.0) | 9.5 (26.5) | 6.9 (11.7) |

| Cardiovascular Risk Factors and Medical History | |||

| History diabetes, % | 23 | 35 | 10 |

| History of hyperlipidemia, % | 62 | 59 | 62 |

| BMI, mean (SD) | 29 (4) | 31 (5) | 29 (4) |

| History of hypertension, % | 57 | 73 | 59 |

| History of coronary heart disease, % | 12 | 18 | 14 |

| Chest pain in past 4 weeks, % | 17 | 23 | 28 |

| Other Psychiatric Diagnoses (Lifetime) | |||

| Major Depression, % | 13 | 38 | 69 |

| Alcohol Abuse (with or without dependence), % | 17 | 35 | 48 |

| Drug Abuse (with or without dependence), % | 8 | 18 | 24 |

| Current Medications | |||

| Aspirin, % | 49 | 38 | 14 |

| Statins, % | 53 | 47 | 35 |

| Beta-blockers, % | 26 | 32 | 7 |

| ACE Inhibitors, % | 27 | 32 | 17 |

| Antidepressants, % | 9 | 35 | 52 |

All data are percentages unless otherwise indicated.

Abbreviations: PTSD: Posttraumatic Stress Disorder; SD: standard deviation; BMI: body mass index; ACE: angiotensin converting enzyme.

Twins who participated in the in-person Visit 2 had a similar distribution of sociodemographic factors than those who did not participate, and did not materially differ for PTSD status (Table S1). As expected, twins who did not return for Visit 2 had more comorbidities, smoked more and had lower levels of physical activity, but these differences tended to be small. Notably, myocardial perfusion data and blood flow quantitation were similar between the two groups.

In the overall study population, myocardial perfusion abnormalities were infrequent and 80% of twins had a normal scan, denoting no or minimal obstructive coronary artery disease. The relative flow reserve was also normal in 87% of the vascular territories examined, further supporting a low prevalence of flow-limiting stenoses in the sample. The mean MFR was 2.1 (standard deviation, 0.5) and the prevalence of a reduced MFR (MFR < 2.0) was 45%. Comparing PTSD groups, there were no significant differences in resting blood pressure prior to the hyperemia stress test, but resting heart rate was higher in twins with late-onset and longstanding PTSD compared with twins without PTSD (Table 2). Myocardial perfusion abnormalities and left ventricular ejection fraction did not differ significantly by PTSD status. Yet, MFR was substantially depressed in twins with PTSD, showing a dose-response pattern of progressively lower MFR across g PTSD groups, both as a continuous variable and when categorized at the cut point of 2. A low MFR (a ratio <2) was present in 40% of twins without PTSD, 56% of twins with late-onset PTSD, and 72% of twins with longstanding PTSD (p<0.001). Results by vascular territory were consistent. The mean relative flow reserve was close to 1 for all vascular territories and was similar in the 3 PTSD groups.

Table 2.

Imaging data at Visit 2 by lifetime PTSD status assessed longitudinally.

|

No PTSD N =212 |

Late-Onset PTSD N =34 |

Longstanding PTSD N=29 |

P for Trend |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stress test hemodynamics, mean (95% CI) | |||||

| Resting systolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 145 (142, 148) | 144 (137, 151) | 149 (141, 156) | 0.55 | |

| Resting diastolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 78 (76, 79) | 78 (74, 82) | 80 (75, 84) | 0.40 | |

| Resting heart rate, beat/min | 63 (61, 65) | 71 (67, 74) | 70 (65, 74) | <0.001 | |

| Maximum systolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 133 (130, 136) | 137 (131, 144) | 138 (131, 145) | 0.12 | |

| Maximum diastolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 68 (67, 70) | 71 (68, 74) | 72 (68, 75) | 0.03 | |

| Maximum heart rate, beat/min | 87 (85, 89) | 90 (85, 95) | 89 (84, 95) | 0.20 | |

| Maximum rate-pressure product, beat x mm Hg/min per 1000 | 11.6 (11.2, 12.0) | 12.3 (11.5, 13.2) | 12.3 (11.4, 13.3) | 0.05 | |

| Myocardial Perfusion | |||||

| Normal scan, % (n)* | 79 (167) | 91 (31) | 79 (23) | 0.45 | |

| Total percent myocardium abnormal, mean (95% CI) | 3.5 (2.5, 4.4) | 2.5 (0.02, 4.9) | 3.2 (0.6, 5.9) | 0.67 | |

| Rest LVEF, mean (95% CI) | 63 (62, 65) | 65 (62, 68) | 62 (59, 65) | 0.96 | |

| Stress LVEF, mean (95% CI) | 69 (68, 70) | 69 (66, 72) | 66 (63, 69) | 0.12 | |

| Myocardial Blood Flow Quantitation, mean (95% CI) | |||||

| Whole myocardium | |||||

| Stress MBF, mL/min/gm | 1.49 (1.42, 1.56) | 1.53 (1.38, 1.68) | 1.37 (1.20, 1.54) | 0.32 | |

| Rest MBF, mL/min/gm | 0.72 (0.68, 0.76) | 0.82 (0.73, 0.92) | 0.72 (0.62, 0.82) | 0.41 | |

| MFR, mean ratio | 2.13 (2.06, 2.20) | 1.97 (1.81, 2.13) | 1.93 (1.76, 2.10)† | 0.01 | |

| MFR <2, % (n) | 40 (85) | 56 (19) | 72 (21)† | <0.001 | |

| Vascular territories | |||||

| LAD | Stress MBF, mL/min/gm | 1.53 (1.46, 1.60) | 1.51 (1.35, 1.66) | 1.38 (1.21, 1.55) | 0.13 |

| Rest MBF, mL/min/gm | 0.74 (0.66, 0.81) | 0.93 (0.74, 1.11) | 0.73 (0.52, 0.93) | 0.52 | |

| MFR, mean ratio | 2.19 (2.12, 2.26) | 2.02 (1.85, 2.19) | 1.95 (1.77, 2.14)† | 0.006 | |

| RFR, mean ratio | 0.94 (0.93, 0.96) | 0.93 (0.90, 0.96) | 0.93 (0.89, 0.97) | 0.38 | |

| LCX | Stress MBF, mL/min/gm | 1.59 (1.49, 1.70) | 1.74 (1.50, 1.98) | 1.47 (1.21, 1.74) | 0.11 |

| Rest MBF, mL/min/gm | 0.74 (0.71, 0.76) | 0.79 (0.73, 0.85) | 0.77 (0.70, 0.83) | 0.16 | |

| MFR, mean ratio | 2.14 (2.06, 2.21) | 1.96 (1.79, 2.13)† | 1.93 (1.74, 2.11)† | 0.009 | |

| RFR, mean ratio | 0.97 (0.96, 0.97) | 0.98 (0.96, 1.00) | 0.99 (0.96, 1.00) | 0.05 | |

| RCA | Stress MBF, mL/min/gm | 1.35 (1.29, 1.41) | 1.33 (1.21, 1.45) | 1.26 (1.12, 1.40) | 0.26 |

| Rest MBF, mL/min/gm | 0.68 (.65, 0.71) | 0.70 (0.63, 0.78) | 0.67 (0.59, 0.74) | 0.96 | |

| MFR, mean ratio | 2.04 (1.97, 2.11) | 1.91 (1.75, 2.07) | 1.90 (1.73, 2.08) | 0.07 | |

| RFR, mean ratio | 0.84 (0.82, 0.86) | 0.83 (0.79, 0.87) | 0.85 (0.80, 0.89) | 0.97 | |

Abbreviations: PTSD: posttraumatic stress disorder; CI: confidence interval; MBF: myocardial blood flow; MFR: myocardial blood reserve; LAD: left anterior descending; LCX: left circumflex; RCA: right coronary artery; RFR: relative flow reserve.

No PTSD: No lifetime PTSD diagnosis at both visits; Late-Onset PTSD: Lifetime PTSD at Visit 2 but not at Visit 1; Longstanding PTSD: Lifetime PTSD at both Visit 1 and Visit 2. LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction.

Summed stress score ≤ 3, corresponding to < 5% myocardium abnormal.

p<0.05 compared with No PTSD.

After adjusting for lifestyle and clinical risk factors, the differences in MFR by PTSD status persisted (Table 3). After adjustment for the summed stress score from PET myocardial perfusion imaging as a measure of epicardial coronary stenoses, results did not change. Adjustment for lifetime history of major depression similarly did not affect the results. In sensitivity analyses, further adjustment for resting heart rate and peak rate-pressure product during the hyperemia test did not materially alter the results. Throughout the analysis, twins with longstanding PTSD showed the lowest MFR, which was approximately 18% lower than the twins without PTSD and statistically significant in all models. When we repeated the analysis with the change in MFR between Visit 1 and Visit 2 as the outcome variable (Table 3), results remained consistent, with twins with longstanding PTSD showing the most robust decline in MFR from Visit 1 in all models, while twins with late-onset PTSD showed intermediate associations. When we examined MFR with consideration of current PTSD status at each time point, we continued to notice a graded association with PTSD status (Figure 2).

Table 3.

Multivariable analysis of the relationship between lifetime PTSD status, assessed longitudinally, and MFR at Visit 2 and its change from Visit 1, in the overall sample with twins treated as individuals.

| Model | No PTSD | Late-Onset PTSD | Longstanding PTSD | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome: MFR at Visit 2 (N=275) | |||||||

| Mean MFR |

(95% CI) | Mean MFR |

(95% CI) | Mean MFR |

(95% CI) | P for Trend | |

| Unadjusted | 2.13 | (2.06, 2.20) | 1.97 | (1.81, 2.13) | 1.93† | (1.76, 2.10) | 0.010 |

| Adjusted for age, lifestyle and clinical risk factors * | 2.16 | (2.09, 2.23) | 2.04 | (1.89, 2.20) | 1.95† | (1.78, 2.12) | 0.010 |

| + summed stress score | 2.16 | (2.09, 2.23) | 2.03 | (1.88, 2.19) | 1.95† | (1.78, 2.12) | 0.009 |

| + major depression | 2.16 | (2.09, 2.23) | 2.04 | (1.88, 2.19) | 1.96† | (1.78, 2.15) | 0.026 |

| Outcome: Change in MFR Between Visit 1 and Visit 2 (N=207) ‡ | |||||||

| Mean Change (no. of SD) |

(95% CI) | Mean Change (no. of SD) |

(95% CI) | Mean Change (no. of SD) |

(95% CI) | P for Trend | |

| Unadjusted | 0.17 | (0.003, 0.34) | −0.26† | (−0.65, 0.12) | −0.40† | (−0.84, 0.04) | 0.004 |

| Adjusted for age, lifestyle and clinical risk factors * | 0.26 | (0.09, 0.43) | −0.11 | (−0.49, 0.27) | −0.31† | (−0.75, 0.12) | 0.005 |

| + summed stress score | 0.25 | (0.07, 0.43) | −0.15† | (−0.53, 0.23) | −0.32† | (−0.76, 0.11) | 0.004 |

| + major depression | 0.25 | (0.08, 0.43) | −0.16† | (−0.54, 0.22) | −0.35† | (−0.80, 0.11) | 0.005 |

Abbreviations: PTSD: posttraumatic stress disorder; MFR: myocardial flow reserve; CI: confidence interval; SD: standard deviation.

No PTSD: No lifetime PTSD diagnosis at both visits; Late-Onset PTSD: Lifetime PTSD at Visit 2 but not at Visit 1; Longstanding PTSD: Lifetime PTSD at both Visit 1 and Visit 2.

Age, current and past smoking, BMI, physical activity (Baecke score), history of hypertension, history of CHD, and statin use. All models for the analysis of change in MFR also adjusted for Visit 1 MFR.

p<0.05 compared with No PTSD.

Change in MFR was calculated as Visit 2 MFR minus Visit 1 MFR. MFR was standardized using standard deviation as the unit of measurement at each visit. The means express the mean number of standard deviations change in MFR from Visit 1 to Visit 2 (a negative value indicated a decline in MFR).

The above associations remained significant when examining twins within pairs (Table 4). In within-pair analysis, twins who met criteria for a lifetime diagnosis of PTSD at Visit 2 had a significantly lower MFR than their brothers who did not meet PTSD criteria. A dose-response association was observed even within pairs, such that the largest difference in MFR was observed in discordant twin pairs where the affected brother had longstanding PTSD, as opposed to pairs where the affected brother had late-onset PTSD (Table 4). None of the interaction effects between zygosity and outcome variables were significant.

Table 4.

Multivariable within-pair analysis of the relationship between lifetime PTSD status, at Visit 2 and assessed longitudinally, and MFR at Visit 2 and its change from Visit 1.

| Model |

Lifetime PTSD at Visit 2 (PTSD Vs. No PTSD) |

Longitudinal Assessment of PTSD (No PTSD, Late-Onset PTSD, Longstanding PTSD) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome: MFR at Visit 2 (N=122 Twin Pairs, 38 PTSD-Discordant Pairs) | ||||||||

| Mean Within- Pair Difference in MFR, PTSD Vs. No PTSD |

(95% CI) | P | Mean Within- Pair Difference in MFR, Late- Onset PTSD Vs. No PTSD |

(95% CI) | Mean Within-Pair Difference in MFR, Longstanding PTSD Vs. No PTSD |

(95% CI) | P for Trend |

|

| Unadjusted | −0.23 | (−0.41, −0.04) | 0.02 | −0.19 | (−0.41, 0.03) | −0.30 | (−0.61, 0.01) | 0.01 |

| Adjusted for age, lifestyle and clinical risk factors * | −0.21 | (−0.39, −0.02) | 0.03 | −0.20 | (−0.43, 0.02) | −0.31 | (−0.62, 0.01) | 0.01 |

| + summed stress score | −0.22 | (−0.40, −0.04) | 0.02 | −0.22 | (−0.44, 0.005) | −0.32 | (−0.63, −0.005) | 0.007 |

| + major depression | −0.21 | (−0.40, −0.02) | 0.03 | −0.21 | (−0.43, 0.01) | −0.30 | (−0.63, 0.02) | 0.01 |

| Outcome: Change in MFR Between Visit 1 and Visit 2 (N=109 Twin Pairs, 34 PTSD-Discordant Pairs)† | ||||||||

| Mean Within- Pair Difference in Change (no. of SD), PTSD Vs. No PTSD |

(95% CI) | P | Mean Within- Pair Difference in Change (no. of SD), Late-Onset PTSD Vs. No PTSD |

(95% CI) | Mean Within-Pair Difference in Change (no. of SD), Longstanding PTSD Vs. No PTSD |

(95% CI) | P for Trend |

|

| Unadjusted | −0.54 | (−1.01, −0.06) | 0.03 | −0.47 | (−1.05, 0.12) | −0.68 | (−1.48, 0.12) | 0.02 |

| Adjusted for age, lifestyle and clinical risk factors * | −0.55 | (−1.02, −0.08) | 0.02 | −0.53 | (−1.10, 0.04) | −0.60 | (−1.40, 0.21) | 0.02 |

| + summed stress score | −0.59 | (−1.05, −0.13) | 0.01 | −0.57 | (−1.14, −0.01) | −0.63 | (−1.43, 0.16) | 0.01 |

| + major depression | −0.60 | (−1.08, −0.13) | 0.01 | −0.57 | (−1.14, 0.003) | −0.63 | (−1.44, 0.18) | 0.02 |

Abbreviations: MFR: coronary flow reserve; CI: confidence interval; PTSD: posttraumatic stress disorder; SD: standard deviation.

Age, current and past smoking, BMI, physical activity (Baecke score), history of hypertension, history of CHD, and statin use. All models for the analysis of change in MFR also adjusted for Visit 1 MFR.

Change in MFR was calculated as Visit 2 MFR minus Visit 1 MFR. MFR was standardized using standard deviation as the unit of measurement at each visit. The means express the mean number of standard deviations change in MFR from Visit 1 to Visit 2 (a negative value indicated a decline in MFR).

Discussion

In a sample of adult twin military veterans who were assessed twice approximately 12 years apart, we found that PTSD was associated with reduced MFR, a measure of microcirculatory function. The association of PTSD with reduced MFR was especially noted among twins with chronic, longstanding PTSD, i.e., those with a lifetime diagnosis of PTSD at both visits, and it held after adjusting for cardiovascular risk factors, medications and even depression. Twins with longstanding PTSD also demonstrated a significant decrease in MFR from the initial PET scan obtained more than a decade earlier. In contrast, myocardial perfusion defects and relative flow reserve, which are indicative of coronary stenoses in large coronary vessels, were similar. These results suggest that the coronary microvascular circulation is compromised in PTSD. Notably, the associations persisted when comparing twin brothers discordant for PTSD status, therefore ruling out familial and shared environmental factors. The association also persisted after accounting for comorbid psychiatric conditions, including depression and substance abuse.

Our study is unique for the longitudinal assessment of both PTSD status using the SCID and objective measures of perfusion and myocardial blood flow using PET. This design allowed us to examine longitudinal changes in both PTSD and MFR, strengthening the inference for a causal relationship between PTSD and myocardial microcirculatory dysfunction. In a previous investigation of this cohort where PTSD and myocardial perfusion were each measured at a single time point several years apart, we reported an association of PTSD with MFR and with a quantitative measure of abnormal perfusion.16 With longitudinal assessments, we were now able to demonstrate that, while coronary perfusion did not differ in relation to PTSD over time, MFR worsened, suggesting that deterioration of coronary microcirculatory function in PTSD is more of a problem than progression of obstructive coronary artery disease.

There is growing recognition of a role of coronary microvascular dysfunction in myocardial ischemia even in absence of obstructive coronary atherosclerosis. Coronary microvascular disease affects the vasodilatory function of the coronary microcirculation and plays an important role in symptoms, functional status and prognosis of affected individuals.9 MFR measured with cardiac PET is one of the most accepted methods to assess coronary microvascular function, as it can help differentiate diffuse small-vessel disease from abnormal perfusion due to single or multivessel disease.20,23,24,28 MFR, the ratio between peak hyperemic and resting MBF, is a robust predictor of adverse cardiovascular events, independent of angiographic coronary artery disease.10 A reduction in MFR may arise from diminished hyperemic MBF, due to flow-limiting lesions in epicardial coronary arteries, or to vasodilatory dysfunction of small arterioles in the myocardium. MFR can also be reduced spuriously because of an increase in resting MBF, for example in patients with hypertension or elevated heart rate.20 In our study, twins with PTSD had a higher resting heart rate than those without PTSD, but resting MBF was similar across the study groups. Furthermore, adding to the model resting heart rate and maximum rate-pressure product during hyperemia testing did not change the results. Thus, it is unlikely that resting MBF affected our findings. Because myocardial perfusion defects and relative flow reserve were not worse in twins with PTSD, it is also unlikely that flow-limiting coronary lesions play a role. Therefore, the reduction in MFR we observed in twins with PTSD is likely due to functional abnormalities in the coronary microcirculation.

It should be noted that MFR was relatively low in our sample, with an average value of 2.1 and a prevalence of reduced MFR of 45% using a value of 2 as a cut point.27,28 These values, however, are similar to those in other studies of older populations with normal perfusion scans.27 Despite the overall low MFR in our study, we saw clinically meaningful variations based on PTSD diagnosis. Twins with longstanding PTSD had on average approximately 18% lower MFR than those without PTSD, and 72% exhibited a MFR <2.0.

Coronary microvascular dysfunction is a heterogeneous condition and multiple mechanisms could explain its relationship with PTSD. Maladaptive behaviors, like smoking and substance abuse, are common in persons with PTSD37,38 and have been implicated in a reduction in MFR.39,40 In our study, twins with PTSD had often other psychiatric diagnoses and were less likely to be taking preventive cardiovascular medications, but differences in lifestyle factors were small. Nonetheless, adjusting for these factors explained little of the relationship between PTSD and MFR. Similarly, in previous studies behavioral and lifestyle factors did not entirely explain the association between PTSD and cardiovascular disease.41-43 Still, familial confounding could be present. Cardiovascular disease, as well as behavioral and biological risk factors for cardiovascular disease and mental health disorders, cluster within families and have a documented genetic predisposition which may be partially shared across these conditions and thus potentially confound the relationship between PTSD and cardiovascular disease.44 Twins are matched for sociodemographic and early environmental factors (e.g., diet, socioeconomic and parental factors), which contribute to the expression of complex traits. Twins are also genetically similar. By comparing twins within pairs, we were able to rule out potential confounding by familial influences, genetic background and other shared behavioral or biological factors between brothers.

It is likely that neurobiological features characteristic of PTSD are major mechanisms in our findings. PTSD is characterized by chronic dysregulation of neurohormonal systems involved in the stress response.1,14 Individuals with PTSD have heightened sensitivity of the noradrenergic system resulting in increased sympathetic system activity.1,12-14 They also exhibit enhanced negative feedback sensitivity of glucocorticoid receptors.1,13,14 These alterations may result in autonomic function inflexibility, as suggested by abnormal heart rate variability and baroreflex function,45,46 as well as immune dysregulation.15,47-49 These processes have important implications for the function of the endothelium, for vascular reactivity and vascular repair. 50

Individuals with PTSD may be especially vulnerable to these alterations through recurrent reexperiencing symptoms that are part of the disorder, leading to cumulative effects on vasoconstriction, endothelial injury and inflammation that eventually may impact the coronary microvascular circulation. The fact that in our study the associations were stronger for longstanding PTSD than for PTSD that developed more recently, agrees with the notion that chronicity of PTSD symptoms is important in these effects. Consistent with these mechanisms, we previously reported that individuals with PTSD after an acute myocardial infarction, and especially those with high levels of reexperiencing symptoms, have enhanced inflammatory responses during mental stress,15 along with a larger decline of endothelial function and an increased frequency of myocardial ischemia during mental stress.51 Notably, patients with and without PTSD did not differ for severity of coronary stenoses and for ischemia provoked by a conventional stress test, suggesting that the coronary microcirculation is involved.51

There are several limitations in our study. Due to limitations in sample size, we may have had limited power to detect small differences. The sample size was especially reduced in the within-pair analysis, due to the need for longitudinal data on both twins. However, our sample size is not small for a typical PET study. Another limitation is the use of different PET methodologies at the two visits. However, there is a demonstrated agreement between [82Rb] PET and [13N] ammonia PET for myocardial blood flow quantitation.19 Furthermore, we used z scores to standardize measurements at the two visits. Our study also has limited generalizability, since the sample was mostly white and all male. However, the co-twin control design should have improved internal validity by intrinsically adjusting for unmeasured familial confounders. In addition to the strengths of a matched twin design, ours is the only investigation to date to examine longitudinal changes in both PTSD and objective measures of myocardial perfusion and blood flow, allowing the clarification of temporality of associations.

In conclusion, our rigorous twin study supports a link between PTSD and ischemic heart disease, and suggests that worsening coronary microvascular function is implicated. These data fill a significant gap in evidence concerning the long-term cardiovascular consequences of PTSD, and should help in long-term efforts for risk prediction, prevention and treatment to reduce the burden of ischemic heart disease among persons with PTSD.

Supplementary Material

KEY RESOURCES TABLE

| Resource Type | Specific Reagent or Resource | Source or Reference | Identifiers | Additional Information |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Add additional rows as needed for each resource type | Include species and sex when applicable. | Include name of manufacturer, company, repository, individual, or research lab. Include PMID or DOI for references; use “this paper” if new. | Include catalog numbers, stock numbers, database IDs or accession numbers, and/or RRIDs. RRIDs are highly encouraged; search for RRIDs at https://scicrunch.org/resources. | Include any additional information or notes if necessary. |

| Antibody | N/A | |||

| Bacterial or Viral Strain | N/A | |||

| Biological Sample | N/A | |||

| Cell Line | N/A | |||

| Chemical Compound or Drug | N/A | |||

| Commercial Assay Or Kit | N/A | |||

| Deposited Data; Public Database | N/A | |||

| Genetic Reagent | N/A | |||

| Organism/Strain | N/A | |||

| Peptide, Recombinant Protein | N/A | |||

| Recombinant DNA | N/A | |||

| Sequence-Based Reagent | N/A | |||

| Software; Algorithm | N/A | |||

| Transfected Construct | N/A | |||

| Other |

Acknowledgements

The creation and the ongoing development, management, and maintenance of the Vietnam-Era Twin (VET) Registry (CSP #256) is supported by the Cooperative Studies Program (CSP) of the United States Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Office of Research & Development. Over the past decades, data collection has been supported by ancillary grants from the VA, the National Institutes of Health, and other sponsors. Most importantly, the authors gratefully acknowledge the past and continued cooperation and participation of VET Registry members and their families. Without their contribution, this research would not have been possible.

Sources of Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grants R01 HL68630, R01 AG026255, R01 HL125246, R01 HL136205, 2K24 HL077506, K23 HL127251 and T32 HL130025).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures

Ernest V. Garcia receives royalties from the sale of the Emory Cardiac Toolbox, used for some analyses in this study. All other authors report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

Disclaimer Statement

All statements and opinions are solely of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the VET Registry, VA, or United States Government.

References

- 1.Yehuda R Post-traumatic stress disorder. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:108–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Edmondson D, Kronish IM, Shaffer JA, Falzon L, Burg MM. Posttraumatic stress disorder and risk for coronary heart disease: a meta-analytic review. Am Heart J. 2013;166(5):806–814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Song H, Fang F, Arnberg FK, et al. Stress related disorders and risk of cardiovascular disease: population based, sibling controlled cohort study. BMJ. 2019;365:l1255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boscarino JA. A prospective study of PTSD and early-age heart disease mortality among Vietnam veterans: implications for surveillance and prevention. Psychosom Med. 2008;70(6):668–676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roy SS, Foraker RE, Girton RA, Mansfield AJ. Posttraumatic stress disorder and incident heart failure among a community-based sample of US veterans. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(4):757–763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ebrahimi R, Lynch KE, Beckham JC, et al. Association of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Incident Ischemic Heart Disease in Women Veterans. JAMA Cardiology. 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.O'Donnell CJ, Schwartz Longacre L, Cohen BE, et al. Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Cardiovascular Disease: State of the Science, Knowledge Gaps, and Research Opportunities. JAMA Cardiol. 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Camici PG, d'Amati G, Rimoldi O. Coronary microvascular dysfunction: mechanisms and functional assessment. Nature reviews Cardiology. 2015;12(1):48–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Taqueti VR, Di Carli MF. Coronary Microvascular Disease Pathogenic Mechanisms and Therapeutic Options: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72(21):2625–2641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Juarez-Orozco LE, Tio RA, Alexanderson E, et al. Quantitative myocardial perfusion evaluation with positron emission tomography and the risk of cardiovascular events in patients with coronary artery disease: a systematic review of prognostic studies. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2018;19(10):1179–1187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vaccarino V, Khan D, Votaw J, et al. Inflammation is related to coronary flow reserve detected by positron emission tomography in asymptomatic male twins. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57(11):1271–1279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brudey C, Park J, Wiaderkiewicz J, Kobayashi I, Mellman T, Marvar P. Autonomic and inflammatory consequences of posttraumatic stress disorder and the link to cardiovascular disease. American Journal of Physiology-Regulatory Integrative and Comparative Physiology. 2015;309(4):R315–R321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zoladz PR, Diamond DM. Current status on behavioral and biological markers of PTSD: a search for clarity in a conflicting literature. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2013;37(5):860–895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bremner JD, Pearce B. Neurotransmitter, neurohormonal, and neuropeptidal function in stress and PTSD. In: Bremner JD, ed. Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: From Neurobiology to Treatment. Hoboken, New Jersey: Wiley-Blackwell; 2016:181–232. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lima BB, Hammadah M, Wilmot K, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder is associated with enhanced interleukin-6 response to mental stress in subjects with a recent myocardial infarction. Brain Behav Immun. 2019;75:26–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vaccarino V, Goldberg J, Rooks C, et al. Post-traumatic stress disorder and incidence of coronary heart disease: a twin study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62(11):970–978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tsai M, Mori AM, Forsberg CW, et al. The Vietnam Era Twin Registry: a quarter century of progress. Twin Research and Human Genetics. 2013;16(1):429–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.First MB SR, Williams JBW, Gibbon M. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM IV-Patient Edition (SCID-P). Washington, D.C.1995. [Google Scholar]

- 19.El Fakhri G, Kardan A, Sitek A, et al. Reproducibility and accuracy of quantitative myocardial blood flow assessment with (82)Rb PET: comparison with (13)N-ammonia PET. J Nucl Med. 2009;50(7):1062–1071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dilsizian V, Bacharach SL, Beanlands RS, et al. ASNC imaging guidelines/SNMMI procedure standard for positron emission tomography (PET) nuclear cardiology procedures. J Nucl Cardiol. 2016;23(5):1187–1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dorbala S, Di Carli MF, Beanlands RS, et al. Prognostic value of stress myocardial perfusion positron emission tomography: results from a multicenter observational registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61(2):176–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garcia EV, Faber TL, Cooke CD, Folks RD, Chen J, Santana C. The increasing role of quantification in clinical nuclear cardiology: the Emory approach. J Nucl Cardiol. 2007;14(4):420–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaufmann PA, Camici PG. Myocardial blood flow measurement by PET: technical aspects and clinical applications. J Nucl Med. 2005;46(1):75–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.de Silva R, Camici PG. Role of positron emission tomography in the investigation of human coronary circulatory function. Cardiovasc Res. 1994;28(11):1595–1612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Murthy VL, Bateman TM, Beanlands RS, et al. Clinical Quantification of Myocardial Blood Flow Using PET: Joint Position Paper of the SNMMI Cardiovascular Council and the ASNC. J Nucl Med. 2018;59(2):273–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Van Tosh A, Votaw JR, Reichek N, Palestro CJ, Nichols KJ. The relationship between ischemia-induced left ventricular dysfunction, coronary flow reserve, and coronary steal on regadenoson stress-gated 82Rb PET myocardial perfusion imaging. J Nucl Cardiol. 2013;20(6):1060–1068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Murthy VL, Naya M, Taqueti VR, et al. Effects of sex on coronary microvascular dysfunction and cardiac outcomes. Circulation. 2014;129(24):2518–2527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gould KL, Johnson NP, Bateman TM, et al. Anatomic versus physiologic assessment of coronary artery disease. Role of coronary flow reserve, fractional flow reserve, and positron emission tomography imaging in revascularization decision-making. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62(18):1639–1653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stuijfzand WJ, Uusitalo V, Kero T, et al. Relative flow reserve derived from quantitative perfusion imaging may not outperform stress myocardial blood flow for identification of hemodynamically significant coronary artery disease. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015;8(1). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Johnson NP, Gould KL. How Do PET Myocardial Blood Flow Reserve and FFR Differ? Current Cardiology Reports. 2020;22(4):20–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Richardson MT, Ainsworth BE, Wu HC, Jacobs DR Jr., Leon AS. Ability of the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC)/Baecke Questionnaire to assess leisure-time physical activity. Int J Epidemiol. 1995;24(4):685–693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Spertus JA, Winders JA, Dewhurst TA, et al. Development and evaluation of the Seattle Angina Questionnaire: a new functional status measure for coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995;25:333–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Forsberg CW, Goldberg J, Sporleder J, Smith NL. Determining zygosity in the Vietnam era twin registry: an update. Twin Research and Human Genetics. 2010;13(5):461–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Carlin JB, Gurrin LC, Sterne JA, Morley R, Dwyer T. Regression models for twin studies: a critical review. Int J Epidemiol. 2005;34(5):1089–1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McGue M, Osler M, Christensen K. Causal Inference and Observational Research: The Utility of Twins. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2010;5(5):546–556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Carlin JB, Gurrin LC, Sterne JAC, Morley R, Dwyer T. Regression models for twin studies: a critical review. Int J Epidemiol. 2005;34(5):1089–1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Breslau N, Davis GC, Schultz LR. Posttraumatic stress disorder and the incidence of nicotine, alcohol, and other drug disorders in persons who have experienced trauma. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60(3):289–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Scherrer JF, Salas J, Cohen BE, et al. Comorbid Conditions Explain the Association Between Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Incident Cardiovascular Disease. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8(4):e011133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hernandez-Pampaloni M, Keng FY, Kudo T, Sayre JS, Schelbert HR. Abnormal longitudinal, base-to-apex myocardial perfusion gradient by quantitative blood flow measurements in patients with coronary risk factors. Circulation. 2001;104(5):527–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rooks C, Faber T, Votaw J, et al. Effects of smoking on coronary microcirculatory function: a twin study. Atherosclerosis. 2011;215(2):500–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Turner JH, Neylan TC, Schiller NB, Li Y, Cohen BE. Objective Evidence of Myocardial Ischemia in Patients with Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ahmadi N, Hajsadeghi F, Mirshkarlo HB, Budoff M, Yehuda R, Ebrahimi R. Post-traumatic stress disorder, coronary atherosclerosis, and mortality. Am J Cardiol. 2011;108(1):29–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kubzansky LD, Koenen KC, Jones C, Eaton WW. A prospective study of posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms and coronary heart disease in women. Health Psychol. 2009;28(1):125–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Khera AV, Emdin CA, Drake I, et al. Genetic Risk, Adherence to a Healthy Lifestyle, and Coronary Disease. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(24):2349–2358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hughes JW, Dennis MF, Beckham JC. Baroreceptor sensitivity at rest and during stress in women with posttraumatic stress disorder or major depressive disorder. J Trauma Stress. 2007;20(5):667–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shah AJ, Lampert R, Goldberg J, Veledar E, Bremner JD, Vaccarino V. Posttraumatic stress disorder and impaired autonomic modulation in male twins. Biol Psychiatry. 2013;73(11):1103–1110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Spitzer C, Barnow S, Volzke H, et al. Association of posttraumatic stress disorder with low-grade elevation of C-reactive protein: evidence from the general population. J Psychiatr Res. 2010;44(1):15–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Uddin M, Aiello AE, Wildman DE, et al. Epigenetic and immune function profiles associated with posttraumatic stress disorder. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(20):9470–9475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hoge EA, Brandstetter K, Moshier S, Pollack MH, Wong KK, Simon NM. Broad spectrum of cytokine abnormalities in panic disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder. Depress Anxiety. 2009;26(5):447–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hammadah M, Kim JH, Al Mheid I, et al. Coronary and Peripheral Vasomotor Responses to Mental Stress. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7(10). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lima BB, Hammadah M, Pearce BD, et al. Association of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder With Mental Stress-Induced Myocardial Ischemia in Adults After Myocardial Infarction. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(4):e202734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.