Abstract

The important role of mitochondria in the regulation of white adipose tissue (WAT) remodeling and energy balance is increasingly appreciated. The remarkable heterogeneity of the adipose tissue stroma provides a cellular basis to enable adipose tissue plasticity in response to various metabolic stimuli. Regulating mitochondrial function at the cellular level in adipocytes, in adipose progenitor cells, and in adipose tissue macrophages, has a profound impact on adipose homeostasis. Moreover, mitochondria facilitate the cell-to-cell communication within WAT, as well as the crosstalk with other organs, such as the liver, the heart, and the pancreas. A better understanding of mitochondrial regulation in the diverse adipose tissue cell types allows us to develop more specific and efficient approaches to improve adipose function and achieve improvements in overall metabolic health.

Overview of adipose tissue remodeling

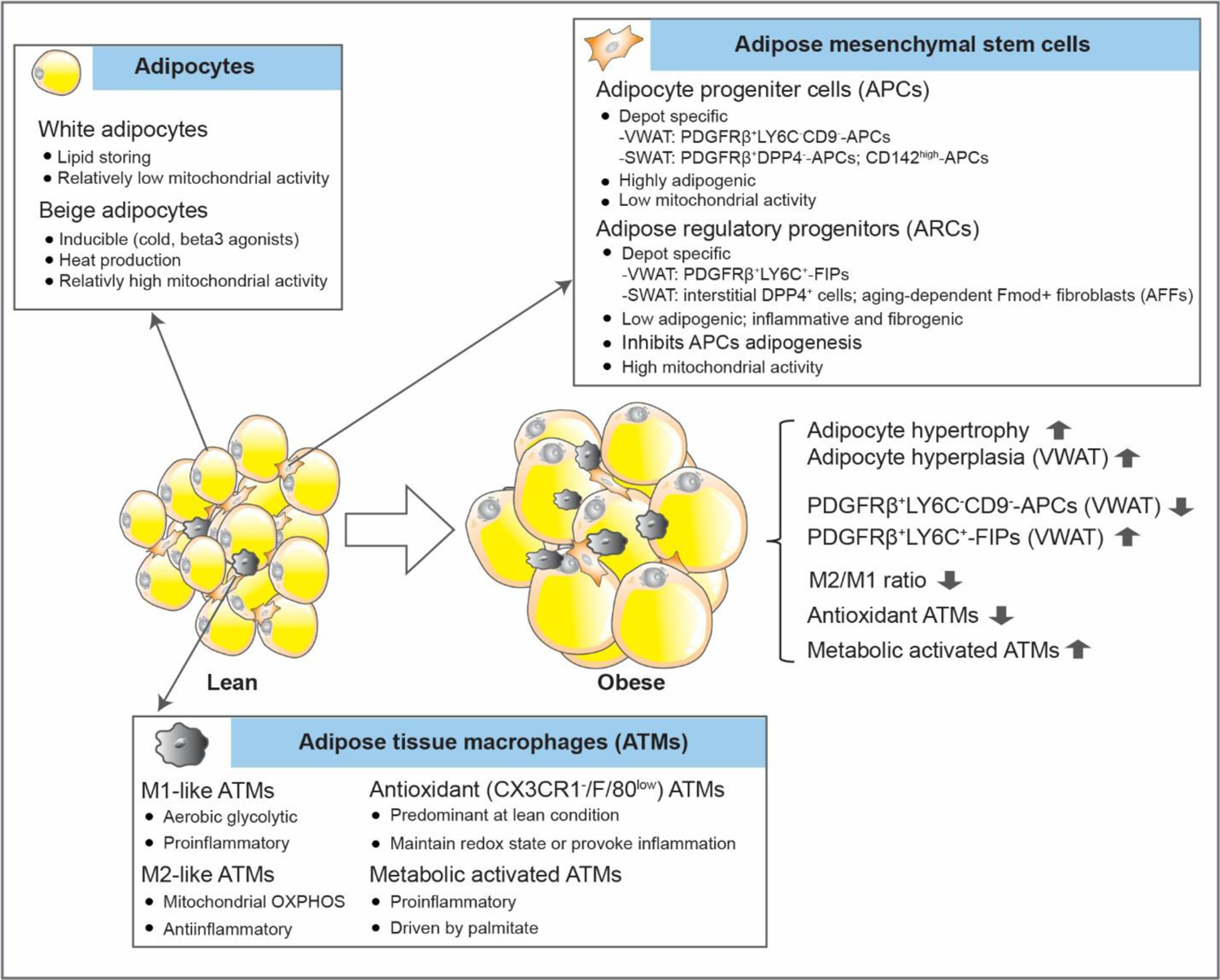

Adipose tissue remodeling is a complex process involving multiple cell types, including adipocytes, adipocyte progenitors, endothelial cells, and immune cells. Although dominating in terms of volume contribution, adipocytes account for less than 50% of cellular content in a WAT depot. Amongst the non-adipocyte fraction, approximately 55% are adipose progenitor cells (APCs, CD31−CD45−CD34+), 37% are immune cells and 8% are endothelial cells in human WAT [1,2]. This cellular homeostasis is delicately regulated upon various metabolic challenges. However, the cell types and mechanisms that account for initiating adipose remodeling remain to be defined. Adipocytes, however, display a rapid reaction in response to excess caloric intake. Hypertrophy (an enlargement in cell size) and hyperplasia (an increase in cell number by de novo adipogenesis) are the main mechanisms of adipocyte plasticity. As short as three days of high-fat-diet (HFD) feeding can lead to an increase in tissue mass and adipocyte size in visceral WAT (VWAT) in mice, concomitant with macrophage infiltration, inflammation and insulin resistance [3]. On the other hand, hyperplasia in VWAT appears within 4–7 days of HFD exposure, and is independent of adipocyte hypertrophy, as it occurs in young and old mice [4,5]. Of note, adipose tissue remodeling occurs in a depot-specific manner [6], as hyperplasia is mainly observed in VWAT and to a much lesser extent in subcutaneous WAT (SWAT). This is despite the fact that both VWAT and SWAT increase in mass and display insulin resistance. Likewise, distinct patterns of adipose inflammation and extracellular matrix remodeling are also observed in different fat pads [7,8]. These depot-specific features are likely due to the local microenvironment, as well as the cellular and functional heterogeneity of the adipose progenitor pool [9,10].

Mitochondria play an essential role in cellular bioenergetics and signaling transduction. Different types of adipocytes, including white, beige, and brown adipocytes, exhibit distinct mitochondrial abundance, function and plasticity [11]. Brown adipocytes contain a high density of mitochondria with remarkable thermogenic potential. Conversely, white adipocytes, as the primary lipid-storing cells, have fewer mitochondria. Beige adipocytes are heterogeneously distributed within WAT, are recruited from distinct beige progenitor pools or may even undergo trans-differentiation from white adipocytes. In the process, these beige cells display notable increases in mitochondrial activity and thermogenesis [11,12]. Moreover, adipocytes can lose their cellular identity and exhibit myofibroblast-like features with mitochondrial deficits upon long-term HFD-feeding [13,14]. Although mitochondrial function in WAT is far less studied compared to brown adipocytes, the critical role of mitochondria in controlling adipose tissue function and systemic metabolic homeostasis increasingly appreciated, far beyond the basic energetic roles seen for cellular homeostasis in many other cell types. Mitochondrial function in adipocytes and other cell types in adipose tissue, including adipose progenitor cells and adipose tissue macrophages within WAT, exerts a profound effect on tissue dynamics, cellular function, and intercellular communication (Figure 1). Thus, adipose tissue mitochondria have the ability to integrate systemic metabolic cues and facilitate adaptive adipose tissue remodeling to maintain overall metabolic health in the entire system. Here, we review our current knowledge about the role of mitochondria in adipose tissue remodeling. We focus on the mitochondrial role in adipose progenitor cells, adipocytes, and adipose tissue macrophages. In addition, we will briefly discuss the mitochondrial role in cell-cell communication within adipose tissues and distal organs.

Figure 1. Intracellular homeostasis in white adipose tissue.

Cellular homeostasis in WAT.

Regulation of mitochondrial activity in white adipose progenitor cells

APCs are residing in the reticular interstitium within adipose tissue [15,16]. These cells have an essential role for proper WAT remodeling in terms of adipogenesis, inflammation, and lipid handling under physiological and pathophysiological conditions. Adipogenesis is simultaneously accompanied by increased mitochondrial biogenesis, activity, and ROS production [17,18]. Accordingly, the differentiation process reprograms the energy status from glycolytic to oxidative metabolism, and thus acquires and maintains a mature adipocyte phenotype [19]. In this regard, a large number of studies suggest that both a dysfunction of mitochondrial metabolism or a dysregulation of ROS production, either by genetic manipulation of mitochondrial components or by pharmacological inhibitors, is sufficient to alter adipogenesis, particularly in cultured preadipocyte cell lines or in the stromal vascular fraction (SVF) of adipose tissues [20–22]. However, with the recent discoveries of distinct classes of APCs, more precise and specific studies on their lineage potential and function have been possible, particularly in the context of depot-specific settings.

The adipose tissue mesenchymal stem cell pool represents a dynamic and heterogeneous set of cells [23,24]. With the advances of single-cell transcriptomics, different types of APCs and adipose regulatory progenitor cells (ARCs) have been described in different WAT depots in rodents and humans. The heterogeneity of adipose progenitors seems to be dependent on age, metabolic status and the depot-specific microenvironment. In murine SWAT, different adipogenic cell populations are described, including PDGFRβ+DPP4−-APCs, CD142high-APCs, as well as committed preadipocytes [15,23–25]. In contrast, in murine VWAT, APCs can be defined as PDGFRβ+LY6C−CD9− cells [23]. In parallel, ARCs can also be specified, including PDGFRβ+LY6C+ cells that correspond to fibro-inflammatory progenitors (FIPs) in VWAT [23], and interstitial DPP4+ cells [15] and aging-dependent adipogenic Fmod+ fibroblasts (AFFs) [25] in SWAT. These regulatory cells are more reluctant to undergo adipogenesis, and are involved in adipose tissue inflammation and extracellular matrix remodeling. For instance, FIPs provoke an inflammatory response and reduce the adipogenic capability of APCs in a paracrine manner [23]. Moreover, FIPs activate inflammatory cascades through a TLR4-dependent manner shortly after a HFD challenge is initiated in mice, and further promote adipose tissue inflammation and insulin resistance [26], highlighting their significant impact on cell-cell interactions during adipose remodeling. As compared to APCs, FIPs have a much greater mitochondrial activity and exhibit higher metabolic rates in response to fatty acid treatment in cultures or upon an acute stimulus with HFD in vivo [27]. As such, the distinct metabolic properties in the progenitors have an important effect on their role in adipose tissue remodeling.

In fact, recent findings highlight mitochondrial metabolism as a critical factor in determining the cell lineage fate and function of APCs. Impaired mitochondrial activity, (with a physiologically relevant reduction obtained through ectopic expression of the protein mitoNEET, an outer mitochondrial membrane protein that regulates oxidative capacity [28]), has a profound effect on the behavior of adipose progenitors in mice [27]. Specifically, mitoNEET in PDGFRβ+ cells enhances an inflammatory response in FIPs and suppresses the adipogenic capacity in APCs in VWAT. Moreover, mitoNEET rapidly shifts the ratio of FIPs/APCs at the onset of diet-induced obesity, with an increase in FIPs and a concomitant decrease in APCs in VWAT [27]. This mitochondrial regulation is a common feedback mechanism, as it also occurs in PDGFRβ+DPP4+ and PDGFRβ+DPP4− progenitors in SWAT, regardless of the depot-specific gene signatures of the APCs. As a result, suboptimal mitochondrial function in progenitor cells, leads to adipose tissue inflammation, partial lipodystrophy and resulting hepatosteatosis in mice, and this process is reversible upon reconstituting full mitochondrial function [27].

Multiple types of APCs have been described in both VWAT (omental) and SWAT (abdominal) from obese subjects, with a common molecular signature and similar adipogenic potential [2]. However, these studies have been largely limited to obese patients who received cosmetic surgery or bariatric bypass surgery rather than healthy lean individuals. In the single-cell transcriptomics analyses, there is only limited overlap amongst APCs between VWAT and SWAT by cell clustering [2], similar to the situation in murine fat depots [24], further highlighting the heterogeneity of the adipose progenitor pool. In addition, different APC subtypes exhibit distinct metabolic and endocrine features [29]. Of note, subpopulations of APCs significantly change with an altered metabolic disease status, e.g. as a function of fasting glycemia and HOMA-IR. Among these cell populations, a subset of CD34− APCs derived from SWAT displays a high level of enrichment of thermogenic and mitochondrial markers, and is committed to beige adipogenesis upon differentiation [29]. Moreover, beige adipocytes can be derived from pluripotent stem cells [30,31]. As such, it is possible that mitochondrial function also contributes to the lineage commitment and function of some subtypes of human adipose progenitors.

Mitochondrial role in determining adipocyte function

Despite the relatively low abundance of mitochondria in white adipocytes, in recent years, numerous studies have highlighted the important role of mitochondria in maintaining white adipocyte function and health. Mitochondrial dysfunction in white adipocytes is considered a hallmark of obesity [32]. It is not surprising that mitochondrial activity is heterogeneous among distinct fat depots. In rodents, adipocytes have a higher respiratory capacity with a higher mitochondrial respiratory chain content in SWAT compared to VWAT. In contrast, VWAT displays increased ROS production compared to SWAT [33]. In humans, lean body mass is associated with a higher mitochondrial respiratory capacity, paralleled by an increase in mitochondrial number in SWAT [34]. In addition, mitochondrial activity in white adipocytes declines with aging. For instance, the mitochondrial complex IV component COX5B was significantly repressed along with aging-induced adipocyte enlargement, in a HIF1α-dependent manner [35]. Moreover, an age-dependent reduction in COX5B gene expression was also observed in human WAT, implicating a conserved mechanism of mitochondrial decline in rodents and humans [35]. However, other reports have come to different conclusions. A recent study argued that HFD feeding did not impair adipocyte mitochondrial respiratory capacity when normalized to adipocyte cell size and/or number. Nevertheless, increased mitochondrial ROS was shown to be an enduring characteristic within WAT exposed to both short-term and long-term HFD challenges [36].

In the past few years, studies employing rodent models carrying genetic manipulations of mitochondrial components greatly expanded our insights about mitochondrial regulation of adipocyte function. Peroxiredoxin 3 (Prx3), a thioredoxin-dependent mitochondrial peroxidase, is abundantly expressed in white adipocytes and reduced in the obese state. Deletion of Prx3 impaired mitochondrial biogenesis and enhanced oxidative stress in adipocytes, and further caused systemic glucose intolerance and insulin resistance [37]. Paraoxonase 2 (PON2) is a lactonase that primarily locates to the endoplasmic reticulum and to mitochondria. Deletion of PON2 lowered mitochondrial respiration and resulted in adipocyte hypertrophy in WAT, and thus promoted diet-induced obesity [38]. Mitochondrial ferritin (FtMT) is a mitochondrial matrix protein and plays a key role in iron balance. A critical role of FtMT in adipocyte mitochondrial function and energy metabolism is apparent during obesity. Adipocyte-specific overexpression of FtMT enhanced local ROS damage, and caused lipodystrophy and insulin resistance [39]. In addition, deletion of Hsp60, a key mitochondrial matrix chaperone, reduced mitochondrial respiration and caused insulin resistance locally in VWAT. However, these mice exhibited a systemic benefit in weight gain and glucose metabolism likely due to enhanced adipocyte hyperplasia [40]. Furthermore, mitochondrial transporters located on the outer and inner membranes are major components that are essential for mitochondrial function. Specific roles of such transporters in white adipocyte function are increasingly appreciated. The mitochondrial dicarboxylate carrier (mDIC, or SLC25A10) is highly expressed in white adipocytes [41]. In adipocytes, mDIC controls lipolysis through export of the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle intermediate succinate from mitochondria to the cytosol. As a result, a specific deletion of mDIC in adipocytes leads to unconstrained fatty acid release and subsequent hepatic lipotoxicity[42].

In addition to above mitochondria-resident factors, proteins mis-targeted to mitochondria could also lead to alterations in adipocyte mitochondrial function. In 2019, an unexpected role of amyloid precursor protein (APP) in mitochondrial impairment was identified due to its unconventional mis-localization in adipocyte mitochondria. This mis-localization of APP significantly comprised mitochondrial protein import and reduced mitochondrial respiration, eventually promoting obesity [43]. A recent study further echoed the importance of APP in regulating adipocyte mitochondrial function. Deletion of Irx5, a homeobox transcription factor, protected mice from diet-induced obesity by enhancing adipose metabolic machinery due to APP reduction in white adipocytes. In addition, a knockdown App significantly increased mitochondrial respiration in adipocytes [44]. Thus, targeting APP might provide a powerful therapeutic approach to improve adipocyte function and diet-induced obesity. Another example for unconventional mitochondrial localization in adipocytes is forkhead box protein O1 (FoxO1). FoxO1 is not exclusively located in the cytosol or nucleus in adipocytes, it is also located in mitochondria where it binds to mtDNA. Under starvation conditions, FoxO1 is de-phosphorylated and then shuttled from mitochondria to the nucleus. Therefore, FoxO1 could be considered a nutrient-stress sensor and a mito-nuclear communicator in white adipocytes [45].

Mitochondria are not only regulated by components located in mitochondria, but there are also additional intracellular and extracellular factors that are indispensable for maintaining mitochondrial health in adipocytes. These factors mainly fall into the categories of epigenetic factors [46–48], microRNAs [49,50] and IncRNAs [51,52], inflammatory molecules [53,54], hormones [55–60], and other factors [61–64] (summarized in Table 1).

Table 1:

Factors that maintain mitochondrial health in adipocytes

| Factor | Function in regulating white adipocyte mitochondria | Function on adipocyte function and/or WAT homeostasis | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Epigenetic factors | |||

| DNA Methyltransferase 1, DNMT1 | DNMT1 is a major DNA methylation mediator. Deletion of Dnmt1 in adipocytes inhibits mitochondrial fission. | Deletion of Dnmt1 in adipocytes promotes adipocyte hypertrophy and WAT dysfunction. | [46] |

| N-acetyltransferase 2, NAT2 | Human NAT2 regulates insulin resistance. Deletion of the mouse ortholog Nat1, both in vitro in 3T3-L1 adipocytes and in vivo in adipocytes, promotes mitochondrial dysfunction by increasing intracellular ROS levels, enhancing mitochondrial fragmentation, and decreasing mitochondrial respiration. | Nat1-deficient mice show a decreased ability to utilize fat for energy and a decrease in basal metabolic rate without affecting thermogenesis. | [47] |

| Sirtuin-3, SIRT3 | The deacetylase SIRT3 is a key player in mitochondrial biology. However, adipocyte SIRT3 is dispensable for maintaining mitochondrial function in adipose tissues and whole-body energy homeostasis, since lack of Sirt3 in adipocytes does not alter mitochondrial respiration. | Lack of Sirt3 has no impact on systemic glucose and lipid metabolism. | [48] |

| MicroRNAs | |||

| miR-494-3p | miR-494-3p regulates mitochondrial biogenesis and thermogenesis in WAT. | miR-494-3p mediates the browning of WAT. | [49] |

| miR-30a | miR-30a modulates human adipocyte mitochondrial function by regulating the expression of ubiquitin carrier protein 9 (Ubc9). | Enforced expression of a miR-30a mimic promotes browning of human white adipocytes. | [50] |

| Long non-coding RNAs, lncRNAs | |||

| Blnc1 | Overexpression of Blnc1 in VWAT via adenovirus increases mtDNA content and enhanced expression of mitochondriarelated genes via stimulating the transcription of Pgc1b. | The long noncoding RNA blnc1 protects against diet-induced obesity in mice. | [51] |

| AK079912 | Overexpression of lncRNA AK079912 in white preadipocytes increases thermogenesis-related genes, whereas inhibition of AK079912 reduces mtDNA copy number and mitochondrial electron transport chain (ETC) complex protein levels in white adipocytes. | Knockdown of AK079912 inhibits browning of white adipocytes, as judged by a reduction in brown fat specific genes. | [52] |

| Inflammation molecules | |||

| CD47 | CD47 is a transmembrane receptor functioning in self-recognition and immune cell infiltration. In white adipocytes, CD47 regulates lipolysis and mitochondrial fuel availability. | CD47 enhances energy expenditure in mice. | [53] |

| Bone morphogenetic protein receptor type 2, BMPR2 | In white adipocytes, deletion of the inflammation factor, BMPR2, impaired fatty acid oxidation and oxidative phosphorylation. | Deletion of BMPR2 reduces white adipocyte lipolysis and enhanced apoptotic cell death. | [54] |

| Hormones | |||

| Prostaglandin E | Deletion of prostaglandin E receptor subtype 4 (EP4) in white adipocytes increases mitochondrial biogenesis and oxidative phosphorylation. | Deletion of EP4 positively regulates healthy WAT remodeling and promotes fat mass loss in mice. | [55] |

| Brain-derived neurotrophic factor, BDNF | BDNF, a neuronal factor, enhances white adipocyte mitochondrial biogenesis and thermogenesis through sympathetic activation in mice. In differentiated 3T3-L1 adipocytes, BDNF administration enhances mitochondrial fission, increases browning markers, and alters mitochondrial dynamic genes. | BDNF exerts an important role in promoting white adipocyte browning in vitro. | [56] |

| Estrogen (Estradiol, E2) | Estradiol (E2) promotes mitochondrial function through activating of both G protein-coupled estrogen receptor (GPER) and estrogen receptor α (ERα). In addition, estrogen receptor α (ERα) regulates the mtDNA polymerase γ subunit Polgi, to maintain mitochondrial function in white adipocytes. Deletion of ERα (Esr1) in adipocytes reduces mtDNA content and decreases mitochondrial activity in a E3 ubiquitin ligase parkin-dependent pathway. | E2 prevents inflammation in white adipose tissue. | [57, 58] |

| Testosterone | Testosterone exerts opposite effects compared to estradiol, resulting in decreased mitochondrial biogenesis in white adipocytes. | Testosterone further decreases adiponectin production in white adipocytes. | [59] |

| Betatrophin | Betatrophin is a negative regulator of white adipocyte mitochondrial biogenesis. Knockdown of Betatrophin increases mitochondrial content and mitochondrial biogenesis markers through the activation of the AMPK signaling pathway. | Downregulation of betatrophin induces a browning process in white adipocytes. | [60] |

| Others | |||

| Biliverdin Reductase A, BVRA | Adipocyte-specific deletion of BVRA, a protein highly expressed in the spleen and liver, decreases the number of mitochondria in white adipocytes. | Adipocyte-specific deletion of BVRA promotes adipocyte hypertrophy and obesity. | [61] |

| ESRRG and PERM1 | ESRRG and PERM1 are two key regulators of the PGC1α transcriptional network, which positively regulates mitochondrial function during cold exposure. | ESRRG and PERM1 are essential for the browning of white adipocytes. | [62] |

| Caloric restriction (CR) | In white adipocytes, CR enhances mitochondrial biogenesis via a leptin signaling dependent Srebp-1c/FGF21/Pgc1α axis. | CR improves whole body metabolism and promotes healthy WAT remodeling. | [63, 64] |

Mechanisms defending mitochondrial function in adipocytes

Mitochondrial dysfunction in white adipocytes is not always associated with obesity and metabolic deficiency. In a model of adipose-specific deletion of fumarate hydratase (FH), despite severe abnormalities in mitochondria and depletion of ATP, these mice were protected from obesity and insulin resistance. However, this improvement was diminished under thermoneutral conditions [64]. In another study, Han et al. demonstrated that adipocyte-specific deletion of manganese superoxide dismutase (MnSOD) activated mitochondrial biogenesis and enhanced mitochondrial respiration, thereby protecting from diet-induced obesity and insulin resistance, possibly through a robust adaptive response [65]. Different pathways mediate such adaptive responses to mitochondrial stress and are involved in mitochondrial quality control through mechanisms related to mitophagy and secretion of stress signals.

Mitophagy.

Mitophagy, a process that selectively clears damaged mitochondria, is an essential quality control mechanism for mitochondrial homeostasis. FUNDC1 is a newly defined mitophagy receptor, and Fundc1 deficiency causes defective mitophagy in adipocytes, enhances adipose tissue inflammation and exacerbates diet-induced obesity [66]. Although mitophagy is essential for adipocyte mitochondrial quality control, the classical mediator of mitophagy, parkin, is dispensable for mitochondrial regulation in adipocytes, suggesting a parkin-independent mitochondrial quality control mechanism in these cells [67]. Mitofusin 2 (Mfn2), a key component involved in mitochondrial fusion and mitochondrion-endoplasmic reticulum interactions, is a crucial player in adiposity and body weight regulation. A knockdown of Mfn2 specifically in mature adipocytes led to enhanced food intake, increased adiposity, and impaired glucose tolerance [68]. BCL2/adenovirus E1B 19 kDa protein-interacting protein 3 (BNIP3) has been suggested to be a mitochondrial quality regulator. In adipocytes, BNIP3 improves mitochondrial bioenergetics, particularly with rosiglitazone treatment [69]. In an independent study, the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ (PPARγ)-BNIP3 axis was further demonstrated to be a key factor mediating adipose mitochondrial reticulum fragmentation, thereby ameliorating oxidative stress, and improving insulin sensitivity [70]. The E3 ubiquitin ligase membrane-associated RING-CH-type finger 5 (MARCH5) is known to modulate mitochondrial dynamics, is also involved in regulating mitochondrial dynamics and cellular metabolism in adipocytes as well, likely in a PPARγ-dependent manner [71]. Heme oxygenase 1 (HO-1) is another important factor regulating mitochondrial bioenergetics through changing cellular heme-derived carbon monoxide and bilirubin. Deletion of HO-1 in adipocytes significantly decreased the mitochondrial fusion-fission ratio, therefore promoting mitochondrial dysfunction and adipose tissue damage [72]. Autophagy pathways are also involved in mitochondrial function in adipocytes. For instance, ablation of autophagy in adipocytes through deleting Atg3 or Atg16L1 impaired mitochondrial function and enhanced lipid peroxidation, and initiated an adipose-liver crosstalk via lipid peroxide-induced Nrf2 signaling in mice. As a result, these mice developed impaired glucose tolerance and insulin resistance [73].

Stress signal secretion.

In an established model of adipocyte mitochondrial dysfunction, deletion of the essential mitoribosomal protein CR6-interacting factor 1 (Crif1) led to significantly impaired oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) [74,75]. In Crif1-depleted adipocytes, angiopoietin-like 6 (Angptl6) and fibroblast growth factor 21 (FGF21), were identified as two associated secretory factors in response to mitochondrial stress, highlighting a potential protective role of the Angptl6-FGF21 axis during mitochondrial dysfunction in adipocytes [76]. In addition, another signal molecule, GDF15 was also induced upon mitochondrial stress, as observed in adipocyte-specific FtMT-transgenic mice [39]. In response to mitochondrial stress in adipocytes, these mice displayed remarkable pancreatic β-cell hyperplasia, suggesting a potential adipocyte-to-pancreas interorgan signaling axis governed by mitochondrial function [39].

Mitochondrial regulation in adipose tissue macrophages

Components of the adipose tissue immune system establish a unique microenvironment that is crucial for maintaining adipose homeostasis and metabolic health. Multiple types of adaptive and innate immune cells exist in WAT, including B cells, T cells, natural killer (NK) cells, lymphoid cells (ILCs), dendritic cells (DCs), eosinophils and macrophages. A recent study using single cell-transcriptomics provided a landscape of homeostatic and inflammatory networks in human healthy SWAT, and also unveiled many distinct adipose tissue immune cell types, including subsets of ILCs, DCs and macrophage populations that accumulate only in obese SWAT [77]. The distinct immunoregulatory mechanisms governing adipose physiology have been extensively reviewed previously [78–81]. Here, we focus mostly on the mitochondrial regulation, especially in adipose tissue macrophages (ATMs).

ATMs are the numerically dominant immune cell type in WAT, and display a high level of dynamic behavior, with a dramatic increase in the obese state (>50% of leukocytes) compared to the lean state (where they represent only 5–10% of leukocytes) [82–84]. Adipose tissue inflammation in obesity is considered to be associated with a switch from an anti-inflammatory M2 subtype towards a pro-inflammatory M1 phenotype. In addition, M1 macrophages are suggested to utilize aerobic glycolysis, whereas M2 macrophages rely more heavily on mitochondrial OXPHOS for energy demand [85]. In this regard, mitochondrial function has a critical role in this phenotypic conversion. Inhibition of OXPHOS prevents M1 to M2 polarization as suggested in bone marrow-derived macrophages and peripheral blood monocyte-derived macrophages, whereas inhibiting nitric oxide production by iNOS inhibitors, which enhances mitochondrial function in M1 macrophages, improves M2 reprogramming [86]. Consistent with this, a deficiency of mitochondrial OXPHOS biases ATMs in VWAT towards a M1 polarization, adipose inflammation and insulin resistance in obese mice carrying a myeloid-specific deletion of Crif1, an essential mitoribosomal factor for the biogenesis of OXPHOS subunits [87]. Conversely, increasing OXPHOS by GDF15 promotes a M2 phenotype and reverses insulin resistance [87].

However, major ATMs exhibit distinct mitochondrial energetics from the classic M1/M2 macrophages. For instance, ATMs isolated from lean VWAT exhibit a low metabolic rate with reduced OXPHOS and glycolysis, whereas ATMs from obese VWAT are highly energetically active with enhanced OXPHOS and glycolysis [88]. In line with these observations, both in obese (but not lean mice and humans!), ATMs in VWAT and SWAT gain a phenotype that is molecularly and metabolically distinct from classic M1/M2 macrophages, driven by palmitate-mediated pathways, but independent of proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory pathways [89]. These metabolically activated ATMs can exert a pro-inflammatory effect, and likely mediate an important role in buffering excess lipids during obesity [89]. In contrast, major ATMs in VWAT under lean conditions are defined as antioxidant macrophages (CX3CR1−/F4/80low), as opposed to M1/M2 macrophages [88]. Obesity leads to an increase in full-length and reduced truncated oxidized phospholipids (OxPLs) in WAT. Accordingly, the antioxidant ATMs adjust their bioenergetic status and antioxidant response, by sensing these OxPLs, to either maintain redox homeostasis or provoke inflammation [88]. As such, mitochondrial metabolism has an important role in regulating the phenotypic switch and function of different ATMs.

On the other hand, ATMs mediate adipocyte bioenergetics via paracrine mechanisms. Conditioned media (CM) from IL10/TGFβ-activated macrophages (CD163high/CD40low) reduce ATP-coupled mitochondrial respiration by decreasing complex III activity, whereas CM from LPS/IFNγ-activated macrophages (CD163low/CD40high) enhance mitochondrial activity in human white adipocytes [90]. Thus, ATMs are critical mediators within the distinct microenvironment, exerting an important effect on adipose tissue energy homeostasis.

Thus, it is worth seeing whether targeting mitochondrial function in ATMs can modify their phenotype or function to improve adipose remodeling during obesity. To this end, a recent study characterized a near-infrared heptamethine cyanine fluorophore (IR-61) that selectively targets ATMs in VWAT rather than other immune cells in fat or other tissues, such as liver or spleen [91]. Indeed, IR-61 preferentially accumulates in ATM mitochondria and enhances mitochondrial OXPHOS by increasing mitochondrial complex content and activity via ROS-Akt-Acly pathway [91]. As a consequence, IR-61 suppresses M1 macrophage activation, and prevents adipose inflammation, weight gain and insulin resistance in obese mice [91]. This pharmacological study however awaits confirmation through more classical genetic means.

Mitochondrial regulation of cell-to-cell communication

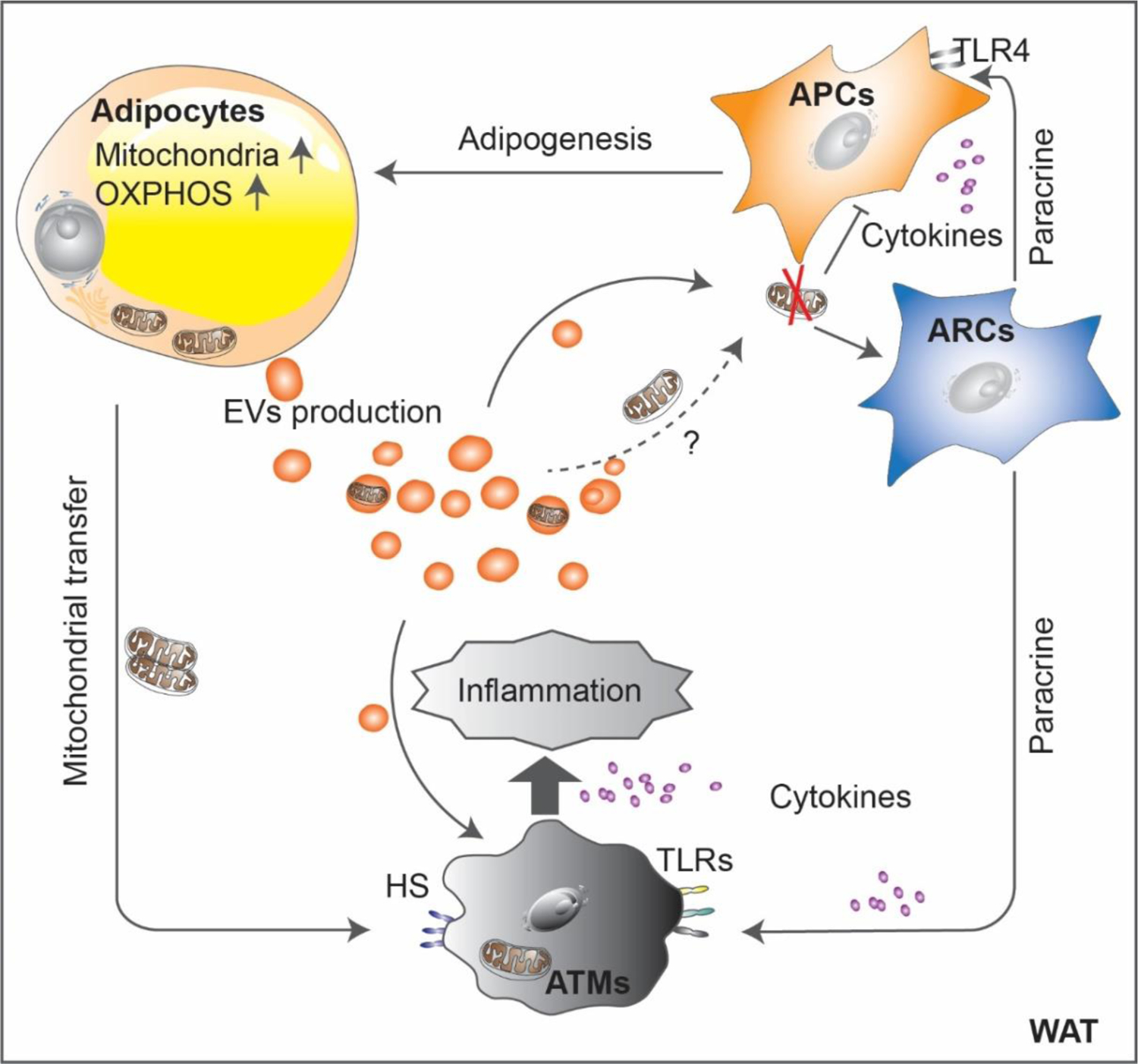

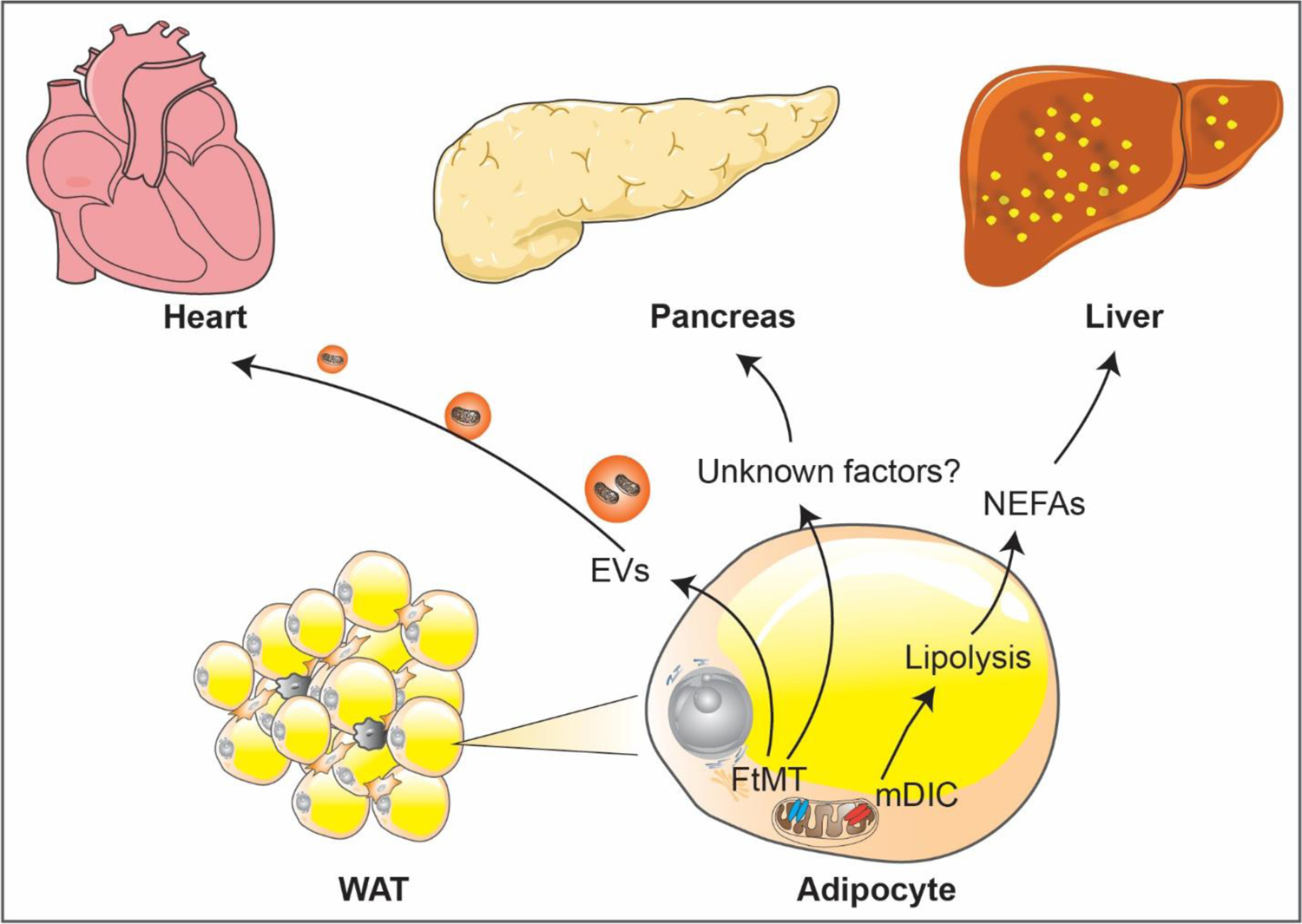

As a central player in energetic metabolism across cell types, mitochondrial activity drives cell-to-cell communication locally in WAT (Figure 2), and mitochondrial activity can also carry effects to distal organs (Figure 3). Intercellular mitochondria transfer provides a common mechanism for energetic synchronization that typically occurs in stem cells that often serve as ‘the donor’, towards other cell types, such as neurons, cardiomyocytes, epithelial cells, and macrophages [92]. This mitochondrial trafficking is important for multifunctional cellular activity during tissue homeostasis under various physiological and pathological conditions. For example, a recent study demonstrated that mitochondria transfer also occurs from adipocytes to ATMs via a heparan sulfate (HS)-dependent mechanism [93]. Moreover, this transfer is reduced in the obese state probably due to a phenotypic switch of macrophages [93]. In addition, myeloid-specific deletion of the HS biosynthetic gene Ext1 decreases mitochondrial uptake in ATMs, increases adiposity, and reduces energy expenditure and glucose tolerance in mice [93]. Thus, this adipocyte-to-macrophage mitochondrial transfer exerts a vital role in maintaining metabolic homeostasis locally and systemically. However, it remains poorly understood how this transfer affects adipocyte and ATM functions and how it further translates into metabolic controls. Also, whether other cell types within the adipose stroma, such as adipose progenitor cells and epithelial cells, are also involved in this mitochondrial transfer event remains unexplored.

Figure 2. Mitochondrial regulation of intercellular communication in white adipose tissue.

Mitochondrial regulation of intercellular communications in WAT. Adipocyte progenitor cells (APCs) differentiate into adipocytes and gain increased mitochondrial content and OXPHOS activity. Mitochondrial dysfunction reduces adipogenic potential of APCs, whereas it promotes the inflammatory effects of adipose regulatory progenitor cells (ARCs), which in turn, inhibits adipogenesis and enhances inflammation in a cytokine-mediated paracrine manner. On the other hand, white adipocytes secrete extracellular vesicles (EVs) that link different adipose cell types such as progenitor cells and adipose tissue macrophages (ATMs) for adapting metabolic alterations. In addition, adipocytes directly transfer mitochondria to ATMs via a heparan sulfate (HS)-dependent mechanism. In obesogenic conditions, ATMs are activated towards proinflammatory polarization and further promotes inflammation in WAT.

Figure 3. Mitochondrial regulation of white adipose tissue-derived inter-organ communication.

Mitochondrial regulation of WAT-centered inter-organ communications. The mitochondrial dicarboxylate carrier (mDIC) controls lipolysis in adipocytes. Deletion of mDIC in adipocytes leads to unconstrained fatty acid release and subsequent hepatic lipotoxicity. Moreover, mitochondrial dysfunction in adipocytes, as seen in the adipocyte-specific mitochondrial ferritin (FtMT)-transgenic mice, promotes remarkable pancreatic β-cell hyperplasia by an unclear mechanisms. In addition, adipocytes produce EVs carrying mitochondrial-derived components. In the FtMT-transgenic mice, compromised mitochondrial vesicles packaged into EVs that derived from adipocytes exert potent mitohormetic effects on cardiomyocytes by inducing mild ROS-mediated damage that preconditions the heart to more severe oxidative stress, such as in an ischemia/reperfusion model.

Adipocytes are an active source of extracellular vesicles (EVs), which modulate metabolism in adipose tisse and beyond, by facilitating intercellular or interorgan crosstalk [94,95]. For instance, extensive interchange of cellular material occurs between adipocytes and endothelial cells via EVs in response to metabolic signaling, such as fasting/refeeding and obesity [96]. Secreted EVs have a vital role in regulating mitochondrial dynamics. A number of studies suggested that EVs from some cell types contain active and functional mitochondria or mitochondrial components, including mesenchymal stem cells [97][98], endothelial cells [99], monocytes [100], and adipocytes [101][102]. Accordingly, EVs carrying mitochondrial-derived components modify the energetic status of recipient cells and can compromise the cellular functions. In the case of cardiomyocytes, mitochondrial vesicles packaged into EVs derived from compromised adipocytes exert potent mitohormetic effects on the heart by inducing mild ROS-mediated damage that precondition the heart to more severe oxidative stress, such as in the context of an ischemia/reperfusion assay [102]. Yet, mechanisms underlying the secretion and the targeting of mitochondria or mitochondrial components remain largely unknown and constitute a very fertile research area for the future.

On the other hand, additional effects can be seen for “mitotherapies” through administration of exogenous mitochondria intravenously, exhibiting significant benefits for hepatic function and oxidative metabolism in obese mice [103] or mice with acetaminophen-induced liver injury [104]. In addition, mitotherapy increases mitochondrial activity in the brain and ameliorates cognitive function in Alzheimer’s disease mice [105]. Hence, these studies provide new strategies of enhancing intercellular mitochondrial transfer or mitotherapy, for the treatment of mitochondrial dysfunction-related metabolic diseases including obesity.

Concluding Remarks

Research in the past several years focused on mitochondrial regulation in WAT homeostasis has significantly advanced our understanding of how mitochondria critically contribute to adipose tissue health. Far beyond their basic roles as the “powerhouse” of the cell, mitochondria exert multifaceted effects on adipocytes, adipose progenitor cells, and other adipose tissue-resident cells. It is increasingly appreciated that mitochondrial metabolism is a critical factor in determining the cell lineage fate and function of APCs. Mitochondrial regulation is indispensable for determining mature adipocyte function and it also exerts a profound impact on the microenvironment within WAT. One of the most important breakthroughs during the past few years is the realization that mitochondria are important mediators of cell-to-cell crosstalk, either within the WAT or in the crosstalk from adipose tissue to other organs.

Moving forward to the next phase, many outstanding questions remain (see Outstanding Questions Box). Further studies into the relationship between mitochondrial function and the cellular heterogeneity among adipocytes in different fat pads will be essential for a better understanding for fat depot differences. To address this important question, the development of specific genetic tools for the expression in distinct adipocyte subpopulations and the subsequent genetic manipulation of mitochondrial components in these adipocyte subtypes are urgently needed. Although single cell-transcriptomics has been extensively applied in many other tissues and cell types, it remains a technology that is very challenging for white adipocytes. Regarding a better understanding of adipose SVF heterogeneity driven by mitochondrial metabolism, the use of high-throughput analysis, such as single cell RNA-Sequencing of the SVF is less challenging compared to white adipocytes. Thus, upon identification of distinct cell populations in the SVF, specific manipulations of the key mitochondrial components in each of these cell types is the next obvious step.

Outstanding Questions Box.

1) Does mitochondrial function drive the heterogeneity of adipocytes in different fat pads? 2) Similarly, does mitochondrial function determine the heterogeneity of the adipose tissue stromal vascular fraction? 3) Does the manipulation of mitochondrial respiration in adipocyte progenitor cells improve adipogenesis? 4) Furthermore, what are the potential therapeutic avenues towards modifying adipose tissue mitochondrial function to improve obesity and metabolic disease? 5) How do we therapeutically modify mitochondrial function in a targeted way to improve adipose tissue health in obesity and metabolic diseases?

Therapeutic potential and translational feasibility remain at the forefront of WAT mitochondrial research. A detailed time course analysis for each WAT mitochondrial dysfunction model described in previous studies will need to be carried out to determine the treatment window for a therapeutic intervention to reverse the mitochondrial defects. Furthermore, recently identified key mitochondrial pathway regulators need to be tested for their potential to improve adipose tissue function under obese conditions. Factors that are considered to be protective against mitochondrial dysfunction, miRNAs that positively regulate WAT mitochondrial function and promote WAT browning activity, sEVs that are derived from the WAT containing mitochondrial components or even functional mitochondria, as well as healthy mitochondrial transplants are particularly interesting for future efforts. Last but not least, moving from current cellular- and rodent model- centered research to more human relevant clinical research is warranted. So far, only correlations between reduced mitochondrial activity and the development of obesity in the clinical setting have been established. Specific ways to improve adipose health and obesity through targeting mitochondrial pathways in patients have not yet been explored. Inducing selective beiging for WAT as well as the induction of protective mechanisms against mitochondrial dysfunction through small molecule chemistry bear significant promise for the future anti-obesity approaches.

Highlights.

Regulation of mitochondrial activity in white adipocytes is an essential component of adipose tissue and systemic metabolic homeostasis

Additional cells in adipose tissue (progenitors, endothelial cells, immune cells) are also critically regulated by mitochondrial activity in the respective cells.

Intercellular and interorgan exchange of mitochondria is an important new mechanism of information exchange between cells and tissues.

A key feature of the regulation of mitochondrial activity in adipose tissue is the choice of the preferred carbon source in the respective cells within adipose tissue, i.e. use of carbohydrate through glycolysis vs. use of lipids for oxidative phosphorylation.

The choice of substrate for energy production exerts a profound impact on the characteristic metabolic features of the various cell types that make up adipose tissue and their impact on tissue and systemic energy homeostasis.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants RC2-DK118620, R01-DK55758, R01-DK099110, R01-DK127274 and P01-AG051459 to P.E.S. Y.A.A is supported by NIH grant K01-DK125447. Q.Z. is supported by AHA Career Development Award 855170.

Glossary

- Rosiglitazone

an agonist of the nuclear receptor, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ (PPARγ), the key transcription factor for adipocyte differentiation. Treatment of rosiglitazone improves hyperglycemia and insulin resistance in obesity

- HOMA-IR

short for Homeostatic Model Assessment of Insulin Resistance. It is a widely used indicator of insulin resistance

- Mitohormetic

the beneficial role of mitochondrial stress (e.g. reactive oxygen species) at a reduced level that protects cells against harmful insults

- Acetaminophen-induced liver injury

a common drug-induced acute liver damage model caused by acetaminophen overdose, resulting in excessive mitochondrial oxidative stress, inflammation and hepatocyte dysfunction

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Ehrlund A et al. (2017) The cell-type specific transcriptome in human adipose tissue and influence of obesity on adipocyte progenitors. Sci. Data 4, 1–11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vijay J et al. (2020) Single-cell analysis of human adipose tissue identifies depot- and disease-specific cell types. Nat. Metab 2, 97–109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee YS et al. (2011) Inflammation is necessary for long-term but not short-term high-fat diet-induced insulin resistance. Diabetes 60, 2474–2483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jeffery E et al. (2015) Rapid depot-specific activation of adipocyte precursor cells at the onset of obesity. Nat. Cell Biol 17, 376–385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kulenkampff E and Wolfrum C (2019) Proliferation of nutrition sensing preadipocytes upon short term HFD feeding. Adipocyte 8, 16–25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rosen ED and Spiegelman BM (2014) What we talk about when we talk about fat. Cell 156, 20–44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Badimon L and Cubedo J (2017) Adipose tissue depots and inflammation: Effects on plasticity and residentmesenchymal stem cell function. Cardiovasc. Res 113, 1064–1073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schleinitz D et al. (2020) Identification of distinct transcriptome signatures of human adipose tissue from fifteen depots. Eur. J. Hum. Genet 28, 1714–1725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Macotela Y et al. (2012) Intrinsic differences in adipocyte precursor cells from different white fat depots. Diabetes 61, 1691–1699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jeffery E et al. (2016) The Adipose Tissue Microenvironment Regulates Depot-Specific Adipogenesis in Obesity. Cell Metab. 24, 142–150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ikeda K et al. (2018) The Common and Distinct Features of Brown and Beige Adipocytes. Trends Endocrinol. Metab 29, 191–200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shao M et al. (2019) Cellular origins of beige fat cells revisited. Diabetes 68, 1874–1885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roh HC et al. (2020) Adipocytes fail to maintain cellular identity during obesity due to reduced PPARγ activity and elevated TGFβ-SMAD signaling. Mol. Metab 42, 101086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jones JEC et al. (2020) The Adipocyte Acquires a Fibroblast-Like Transcriptional Signature in Response to a High Fat Diet. Sci. Rep 10, 1–15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Merrick D et al. (2019) Identification of a mesenchymal progenitor cell hierarchy in adipose tissue. Science. 364, aav2501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Benias PC et al. (2018) Structure and distribution of an unrecognized interstitium in human tissues. Sci. Rep 8, 1–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee JH et al. (2019) The role of adipose tissue mitochondria: Regulation of mitochondrial function for the treatment of metabolic diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci 20, 4924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heinonen S et al. (2020) White adipose tissue mitochondrial metabolism in health and in obesity. Obes. Rev 21, 1–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kladnická I et al. (2019) Mitochondrial respiration of adipocytes differentiating from human mesenchymal stem cells derived from adipose tissue. Physiol. Res 68, S287–S296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kusminski CM and Scherer PE (2012) Mitochondrial dysfunction in white adipose tissue. Trends Endocrinol. Metab 23, 435–43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tormos KV et al. (2011) Mitochondrial complex III ROS regulate adipocyte differentiation. Cell Metab. 14, 537–544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fujiwara M et al. (2019) The mitophagy receptor Bcl-2-like protein 13 stimulates adipogenesis by regulating mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation and apoptosis in mice. J. Biol. Chem 294, 12683–12694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hepler C et al. (2018) Identification of functionally distinct fibro-inflammatory and adipogenic stromal subpopulations in visceral adipose tissue of adult mice. Elife 7, 1–36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shao M et al. (2021) Pathologic HIF1α signaling drives adipose progenitor dysfunction in obesity. Cell Stem Cell 28, 685–701.e7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nguyen HP et al. (2021) Aging-dependent regulatory cells emerge in subcutaneous fat to inhibit adipogenesis. Dev. Cell 56, 1437–1451.e3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shan B et al. (2020) Perivascular mesenchymal cells control adipose-tissue macrophage accrual in obesity. Nat. Metab 2, 1332–1349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Joffin N et al. (2021) Mitochondrial metabolism is a key regulator of the fibro-inflammatory and adipogenic stromal subpopulations in white adipose tissue. Cell Stem Cell 28, 702–717.e8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kusminski CM et al. (2012) MitoNEET-driven alterations in adipocyte mitochondrial activity reveal a crucial adaptive process that preserves insulin sensitivity in obesity. Nat. Med 18, 1539–1551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Raajendiran A et al. (2019) Identification of Metabolically Distinct Adipocyte Progenitor Cells in Human Adipose Tissues. Cell Rep. 27, 1528–1540.e7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Su S et al. (2018) A Renewable Source of Human Beige Adipocytes for Development of Therapies to Treat Metabolic Syndrome. Cell Rep. 25, 3215–3228.e9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guénantin AC et al. (2017) Functional human beige adipocytes from induced pluripotent stem cells. Diabetes 66, 1470–1478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schöttl T et al. (2015) Limited OXPHOS capacity in white adipocytes is a hallmark of obesity in laboratory mice irrespective of the glucose tolerance status. Mol. Metab 4, 631–642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schöttl T et al. (2015) Limited mitochondrial capacity of visceral versus subcutaneous white adipocytes in male C57BL/6N mice. Endocrinology 156, 923–933 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ling Y et al. (2019) Persistent low body weight in humans is associated with higher mitochondrial activity in white adipose tissue. Am. J. Clin. Nutr 110, 605–616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Soro-Arnaiz I et al. (2016) Role of Mitochondrial Complex IV in Age-Dependent Obesity. Cell Rep. 16, 2991–3002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Politis-Barber V et al. (2020) Long-term, high-fat feeding exacerbates short-term increases in adipose mitochondrial reactive oxygen species, without impairing mitochondrial respiration. Am. J. Physiol. - Endocrinol. Metab 319, E373–E387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huh JY et al. (2012) Peroxiredoxin 3 is a key molecule regulating adipocyte oxidative stress, mitochondrial biogenesis, and adipokine expression. Antioxidants Redox Signal. 16, 229–243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shih DM et al. (2019) Pon2 deficiency leads to increased susceptibility to diet-induced obesity. Antioxidants 8, 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kusminski CM et al. (2020) A novel model of diabetic complications: Adipocyte mitochondrial dysfunction triggers massive β-cell hyperplasia. Diabetes 69, 313–330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hauffe R et al. (2021) HSP60 reduction protects against diet-induced obesity by modulating energy metabolism in adipose tissue. Mol. Metab 53, 101276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Das K et al. (1999) Predominant expression of the mitochondrial dicarboxylate carrier in white adipose tissue. Biochem. J 344, 313–320 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.An YA et al. (2021) The mitochondrial dicarboxylate carrier prevents hepatic lipotoxicity by inhibiting white adipocyte lipolysis. J. Hepatol 75, 387–399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.An YA et al. (2019) Dysregulation of amyloid precursor protein impairs adipose tissue mitochondrial function and promotes obesity. Nat. Metab 1, 1243–1257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bjune JI et al. (2019) IRX5 regulates adipocyte amyloid precursor protein and mitochondrial respiration in obesity. Int. J. Obes 43, 2151–2162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lettieri-Barbato D et al. (2019) FoxO1 localizes to mitochondria of adipose tissue and is affected by nutrient stress. Metabolism. 95, 84–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Park YJ et al. (2021) DNMT1 maintains metabolic fitness of adipocytes through acting as an epigenetic safeguard of mitochondrial dynamics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 118, 1–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chennamsetty I et al. (2016) Nat1 Deficiency Is Associated with Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Exercise Intolerance in Mice. Cell Rep. 17, 527–540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Porter LC et al. (2018) NAD+-dependent deacetylase SIRT3 in adipocytes is dispensable for maintaining normal adipose tissue mitochondrial function and whole body metabolism. Am. J. Physiol. - Endocrinol. Metab 315, E520–E530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lemecha M et al. (2018) MiR-494–3p regulates mitochondrial biogenesis and thermogenesis through PGC1-α signalling in beige adipocytes. Sci. Rep 8, 1–14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Koh EH et al. (2016) Mitochondrial activity in human white adipocytes is regulated by the ubiquitin carrier protein 9/microRNA-30a axis. J. Biol. Chem 291, 24747–24755 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tang S et al. (2020) The long noncoding RNA blnc1 protects against diet-induced obesity by promoting mitochondrial function in white fat. Diabetes, Metab. Syndr. Obes. Targets Ther 13, 1189–1201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Xiong Y et al. (2018) A novel brown adipocyte-enriched long non-coding RNA that is required for brown adipocyte differentiation and sufficient to drive thermogenic gene program in white adipocytes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 1863, 409–419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Norman-Burgdolf H et al. (2020) CD47 differentially regulates white and brown fat function. Biol. Open 9, bio056747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Qian S et al. (2020) BMPR2 promotes fatty acid oxidation and protects white adipocytes from cell death in mice. Commun. Biol 3, 1–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ying F et al. (2017) Prostaglandin E receptor subtype 4 regulates lipid droplet size and mitochondrial activity in murine subcutaneous white adipose tissue. FASEB J. 31, 4023–4036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Colitti M and Montanari T (2020) Brain-derived neurotrophic factor modulates mitochondrial dynamics and thermogenic phenotype on 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Tissue Cell 66, 101388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhou Z et al. (2020) Estrogen receptor α controls metabolism in white and brown adipocytes by regulating Polg1 and mitochondrial remodeling. Sci. Transl. Med 12, 1–16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bauzá-Thorbrügge M et al. (2019) GPER and ERα mediate estradiol enhancement of mitochondrial function in inflamed adipocytes through a PKA dependent mechanism. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol 185, 256–267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Capllonch-Amer G et al. (2013) Opposite effects of 17-β estradiol and testosterone on Mitochondrial biogenesis and adiponectin synthesis in white adipocytes. J. Mol. Endocrinol 52, 203–214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Liao ZZ et al. (2020) Betatrophin knockdown induces beiging and mitochondria biogenesis of white adipocytes. J. Endocrinol 245, 93–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Stec DE et al. (2020) Biliverdin reductase a (BVRA) knockout in adipocytes induces hypertrophy and reduces mitochondria in white fat of obese mice. Biomolecules 10, 1–14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Müller S et al. (2020) ESRRG and PERM1 Govern Mitochondrial Conversion in Brite/Beige Adipocyte Formation. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne) 11, 1–15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mooli RGR et al. (2020) Sustained mitochondrial biogenesis is essential to maintain caloric restriction-induced beige adipocytes. Metabolism. 107, 154225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kobayashi M et al. (2020) Caloric Restriction-Associated Metabolic Remodeling of White Adipose Tissue. Nutrients 12, 1–15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Han YH et al. (2016) Adipocyte-specific deletion of manganese superoxide dismutase protects from diet-induced obesity through increased mitochondrial uncoupling and biogenesis. Diabetes 65, 2639–2651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wu H et al. (2019) Deficiency of mitophagy receptor FUNDC1 impairs mitochondrial quality and aggravates dietary-induced obesity and metabolic syndrome. Autophagy 15, 1882–1898 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Corsa CAS et al. (2019) The E3 ubiquitin ligase parkin is dispensable for metabolic homeostasis in murine pancreatic β cells and adipocytes. J. Biol. Chem 294, 7296–7307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mancini G et al. (2019) Mitofusin 2 in Mature Adipocytes Controls Adiposity and Body Weight. Cell Rep. 26, 2849–2858.e4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Choi JW et al. (2016) BNIP3 is essential for mitochondrial bioenergetics during adipocyte remodelling in mice. Diabetologia 59, 571–581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Tol MJ et al. (2016) A PPARγ-Bnip3 axis couples adipose mitochondrial fusion-fission balance to systemic insulin sensitivity. Diabetes 65, 2591–2605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bond ST et al. (2019) The E3 ligase MARCH5 is a PPARγ target gene that regulates mitochondria and metabolism in adipocytes. Am. J. Physiol. - Endocrinol. Metab 316, E293–E304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Singh SP et al. (2017) Ablation of adipose-HO-1 expression increases white fat over beige fat through inhibition of mitochondrial fusion and of PGC1α in female mice. Horm. Mol. Biol. Clin. Investig 31, 1–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Cai J et al. (2018) Autophagy Ablation in Adipocytes Induces Insulin Resistance and Reveals Roles for Lipid Peroxide and Nrf2 Signaling in Adipose-Liver Crosstalk. Cell Rep. 25, 1708–1717.e5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ryu MJ et al. (2013) Crif1 Deficiency Reduces Adipose OXPHOS Capacity and Triggers Inflammation and Insulin Resistance in Mice. PLoS Genet. 9, e1003356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Choi MJ et al. (2020) An adipocyte-specific defect in oxidative phosphorylation increases systemic energy expenditure and protects against diet-induced obesity in mouse models. Diabetologia 63, 837–852 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kang SG et al. (2017) ANGPTL6 expression is coupled with mitochondrial OXPHOS function to regulate adipose FGF21. J. Endocrinol 233, 105–118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hildreth AD et al. (2021) Single-cell sequencing of human white adipose tissue identifies new cell states in health and obesity. Nat. Immunol 22, 639–653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kane H and Lynch L (2019) Innate Immune Control of Adipose Tissue Homeostasis. Trends Immunol. 40, 857–872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.LaMarche NM et al. (2018) Innate T Cells Govern Adipose Tissue Biology. J. Immunol 201, 1827–1834 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wang Q and Wu H (2018) T Cells in Adipose Tissue: Critical Players in Immunometabolism. Front. Immunol 9, 9–11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Srikakulapu P and Mcnamara CA (2020) B Lymphocytes and Adipose Tissue Inflammation. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol DOI: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.119.312467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kane H and Lynch L (2019) Innate Immune Control of Adipose Tissue Homeostasis. Trends Immunol. 40, 857–872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Russo L and Lumeng CN (2018) Properties and functions of adipose tissue macrophages in obesity. Immunology 155, 407–417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Zhu Q and Scherer PE (2018) Immunologic and endocrine functions of adipose tissue: implications for kidney disease. Nat. Rev. Nephrol 14, 105–120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.O’Neill LAJ and Pearce EJ (2016) Immunometabolism governs dendritic cell and macrophage function. J. Exp. Med 213, 15–23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Van den Bossche J et al. (2016) Mitochondrial Dysfunction Prevents Repolarization of Inflammatory Macrophages. Cell Rep. 17, 684–696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Jung SB et al. (2018) Reduced oxidative capacity in macrophages results in systemic insulin resistance. Nat. Commun 9, [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Serbulea V et al. (2018) Macrophage phenotype and bioenergetics are controlled by oxidized phospholipids identified in lean and obese adipose tissue. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 115, E6254–E6263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kratz M et al. (2014) Metabolic dysfunction drives a mechanistically distinct proinflammatory phenotype in adipose tissue macrophages. Cell Metab. 20, 614–625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Keuper M et al. (2017) Activated macrophages control human adipocyte mitochondrial bioenergetics via secreted factors. Mol. Metab 6, 1226–1239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Wang Y et al. (2021) Improvement of obesity-associated disorders by a small-molecule drug targeting mitochondria of adipose tissue macrophages. Nat. Commun 12, 1–16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Liu D et al. (2021) Intercellular mitochondrial transfer as a means of tissue revitalization. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther 6, 65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Brestoff JR et al. (2021) Intercellular Mitochondria Transfer to Macrophages Regulates White Adipose Tissue Homeostasis and Is Impaired in Obesity. Cell Metab. 33, 270–282.e8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Crewe C and Scherer PE (2021) Intercellular and interorgan crosstalk through adipocyte extracellular vesicles. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord DOI: 10.1007/s11154-020-09625-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Rome S et al. (2021) Adipocyte-derived extracellular vesicles: State of the art. Int. J. Mol. Sci 22, 1–19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Crewe C et al. (2018) An Endothelial-to-Adipocyte Extracellular Vesicle Axis Governed by Metabolic State. Cell 175, 695–708.e13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Islam MN et al. (2012) Mitochondrial transfer from bone-marrow-derived stromal cells to pulmonary alveoli protects against acute lung injury. Nat. Med 18, 759–765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Morrison TJ et al. (2017) Mesenchymal stromal cells modulate macrophages in clinically relevant lung injury models by extracellular vesicle mitochondrial transfer. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med 196, 1275–1286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Tripathi D et al. (2019) Proinflammatory Effect of Endothelial Microparticles Is Mitochondria Mediated and Modulated Through MAPKAPK2 (MAPK-Activated Protein Kinase 2) Leading to Attenuation of Cardiac Hypertrophy. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol 39, 1100–1112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Puhm F et al. (2019) Mitochondria Are a Subset of Extracellular Vesicles Released by Activated Monocytes and Induce Type I IFN and TNF Responses in Endothelial Cells. Circ. Res 125, 43–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Clement E et al. (2020) Adipocyte extracellular vesicles carry enzymes and fatty acids that stimulate mitochondrial metabolism and remodeling in tumor cells. EMBO J. 39, 1–20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Crewe C et al. (2021) Extracellular vesicle-based interorgan transport of mitochondria from energetically stressed adipocytes. Cell Metab. 33, 1853–1868.e11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Fu A et al. (2017) Mitotherapy for fatty liver by intravenous administration of exogenous mitochondria in male mice. Front. Pharmacol 8, 1–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Shi X et al. (2018) Treatment of acetaminophen-induced liver injury with exogenous mitochondria in mice. Transl. Res 196, 31–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Nitzan K et al. (2019) Mitochondrial Transfer Ameliorates Cognitive Deficits, Neuronal Loss, and Gliosis in Alzheimer’s Disease Mice. J. Alzheimers. Dis 72, 587–604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]