Abstract

Background:

It has been hypothesized that medial temporal sparing may be related to preserved posterior cingulate metabolism and the cingulate island sign (CIS) on [18F]fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) PET in posterior cortical atrophy (PCA).

Objective:

To assess the severity of medial temporal atrophy in PCA and determine whether the presence of a CIS is related to medial temporal sparing.

Methods:

Fifty-five PCA patients underwent MRI and FDG-PET. The degree and symmetry of medial temporal atrophy on MRI was visually assessed using a five-point scale for both hemispheres. Visual assessments of FDG-PET coded the presence/absence of a CIS and whether the CIS was symmetric or asymmetric. Hippocampal volumes and a quantitative CIS were also measured.

Results:

Medial temporal atrophy was most commonly mild or moderate, was symmetric in 55% of patients, and when asymmetric was most commonly worse on the right (76%). Older age and worse memory performance were associated with greater medial temporal atrophy. The CIS was observed in 44% of the PCA patients and was asymmetric in 50% of these. The patients with a CIS showed greater medial temporal asymmetry, but did not show lower medial temporal atrophy scores, compared to those without a CIS. Hippocampal volumes were not associated with quantitative CIS.

Conclusions:

Mild medial temporal atrophy is a common finding in PCA and is associated with memory impairment. However, medial temporal sparing was not related to the presence of a CIS in PCA.

Keywords: FDG-PET, MRI, hippocampus, CIS, visual assessment

Introduction

Posterior cortical atrophy (PCA) is a neurodegenerative disease characterized by prominent visuospatial and perceptual deficits, and features including simultanagnosia, oculomotor apraxia, optic ataxia, acalculia, and visual field defects[1, 2]. Atrophy on MRI and hypometabolism on 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) PET are observed predominantly in the medial and lateral parietal and occipital lobes in PCA[3–9]. Patients with PCA commonly have underlying Alzheimer’s disease (AD) pathology[10, 11] but, unlike typical amnestic AD, the medial temporal lobes tend to be relatively spared in PCA compared to the striking involvement of the parietal and occipital cortices[3, 5, 12]. The medial temporal lobe can be involved in PCA[13], although the frequency and severity of medial temporal atrophy is unclear.

Patients with PCA often show what has been termed the cingulate island sign (CIS) on FDG-PET whereby the posterior cingulate is relatively spared compared to the precuneus and cuneus[14, 15]. The CIS was initially described as a feature of dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) and was shown to be useful for differentiating DLB from typical amnestic AD[15]. The CIS has been observed in 85% of DLB cases and 50% of PCA cases, although the CIS tends to be more commonly asymmetric in PCA[6]. It has been hypothesized that the CIS reflects sparing of the medial temporal lobes and posterior limbic system in DLB[16]. In fact, the CIS has been associated with absence of medial temporal atrophy in DLB[17, 18]. However, it is unknown whether the CIS is related to medial temporal atrophy in PCA which is important since it has been suggested that the pathophysiology of the CIS may differ in PCA and DLB[19].

The aim of this study was to assess the severity of medial temporal atrophy in PCA and determine whether the presence of a CIS in PCA is related to sparing of the medial temporal lobe. We also aimed to determine whether asymmetry in the CIS is related to asymmetry in the medial temporal lobe in PCA. Clinical and demographic correlates of medial temporal atrophy and the CIS were also explored.

Materials and Methods

Patient recruitment

Fifty-seven patients meeting diagnostic criteria for PCA[1] were consecutively recruited by the Neurodegenerative Research Group (NRG) from the Department of Neurology between 6/21/2013 and 3/25/2021. All patients underwent detailed neurological and neuropsychological examinations, 3T volumetric head MRI, FDG-PET and beta-amyloid PET using Pittsburgh Compound B (PiB-PET). Two patients were excluded since they did not show evidence of beta-amyloid deposition on PiB-PET, and hence 55 patients were analyzed in the study. Apolipoprotein E (APOE) genotyping was performed.

The neurological battery included the Montreal Cognitive Assessment Battery (MoCA)[20] to assess general cognition, the Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR)[21] sum of boxes to assess functional performance, the Movement Disorders Society sponsored revision of the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (MDS-UPDRS III)[22] to assess parkinsonism and the Western Aphasia Battery (WAB)[23] ideomotor apraxia score to assess limb apraxia. The neuropsychological battery included the Boston Naming Test (BNT)[24] to assess object naming, the Auditory Verbal Learning Test delayed recall (AVLT-DR)[25] to assess verbal episodic memory, the Visual Object and Space Perception (VOSP)[26] incomplete letter and cubes tests to assess visuoperceptual and visuospatial functioning, respectively; the Rey‐Osterrieth (Rey-O) Complex Figure Copy[25] to assess visuoconstruction, and the Wechsler Memory Scale (WMS)-revised [27] digit span forward test to assess auditory attention span.

MRI analysis

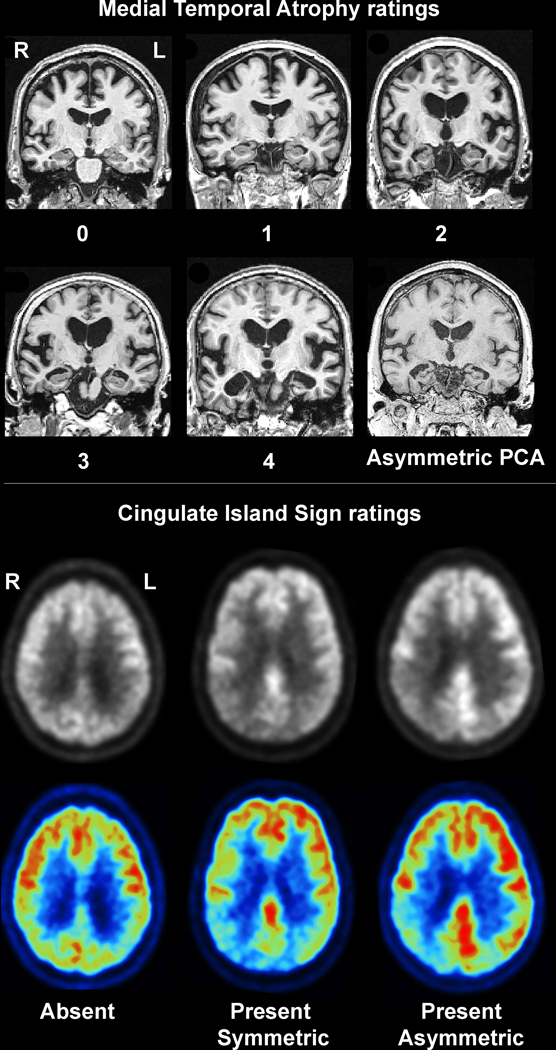

All participants underwent a 3T head MRI protocol that included a magnetization prepared rapid gradient echo (MPRAGE) sequence (TR/TE/TI, 2300/3/900ms; flip angle 8°, 26-cm field of view (FOV); 256×256 in-plane matrix with a phase FOV=0.94, slice thickness=1.2 mm). All MPRAGE scans underwent quality control assessments. Visual assessments of medial temporal atrophy were performed using the Scheltens scale[28] which is a well-validated scale to assess degree of medial temporal lobe atrophy. The left and right medial temporal lobes were each rated on a five-point scale (0=normal; 1=mild; 2=moderate; 3=marked; 4=severe)[28] (Figure 1). Medial temporal ratings were considered asymmetric if the scores for the left and right hemisphere differed by at least one-point (e.g. 2 versus 3). All visual ratings were conducted independently by two raters (KAJ and NTTP) blinded to the FDG-PET and clinical data. In the event of a disagreement in score a third rater (JLW) was used as the tie breaker (n=2 cases). Hippocampal volumes were also calculated using the Mayo Clinic Adult Lifespan Template (MCALT) atlas (https://www.nitrc.org/projects/mcalt/) and divided by total intracranial volume.

Figure 1: Example medial temporal atrophy and CIS visual ratings in patients with PCA.

The top panel shows example MRI images from patients with each medial temporal atrophy rating plus an example case that showed asymmetric medial temporal atrophy. The bottom panel shows examples of an absent CIS, present and symmetric CIS and present and asymmetric CIS shown on a greyscale and color-scale FDG-PET images.

FDG-PET analysis

All FDG-PET scans were performed on a PET/CT scanner (GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, Wisconsin) operating in 3D mode. Patients were injected with FDG (average, 459 MBq; range, 367–576 MBq) and after a 30-minute uptake period an 8-minute FDG scan was performed consisting of four 2-minute dynamic frames following a low dose CT transmission scan. Individual frames of the dynamic series were realigned if motion was detected and then a mean image was created. A visual assessment of the FDG PET images was performed, blinded to clinical diagnosis, to determine whether a CIS was present in each patient based on the axial and sagittal raw FDG PET images. A patient was considered to have a CIS if metabolism was lower in the precuneus and cuneus compared to the posterior cingulate in either hemisphere, as previously described[15, 29] (Figure 1). All ratings were performed blinded to MRI and clinical data. A CIS was visually graded as asymmetric if a CIS was present in one hemisphere but not the other (Figure 1). All visual assessments were performed independently by both KAJ and JLW and discrepancies were reviewed for consensus. If consensus could not be reached a third rater (JGR) was used as the tie breaker (n=3 cases). A quantitative CIS was also calculated by dividing median uptake in the posterior cingulate gyrus by median uptake in the precuneus plus cuneus[6].

Statistical analysis

Associations between medial temporal rating scores and categorical variables (gender, APOE, handedness) were assessed using Fisher’s exact tests. Associations between medial temporal rating scores and continuous variables were assessed using Spearman rank correlations. Since a relationship was identified between medial temporal rating scores and age, linear regression analyses were performed correcting for age at exam for the clinical outcome variables that were not already corrected for age. Pairwise comparisons were performed using Tukey’s Honest Significant Difference (HSD) to assess differences between medial temporal rating levels. Comparisons of demographic, clinical and medial temporal ratings between patients with and without a CIS were performed using Chi-squared tests for categorical variables and two sample t-tests for continuous variables due to the large sample size and relatively normally distributed data. Relationships between hippocampal volumes and the quantitative CIS were assessed using linear regression analyses with quantitative CIS as the dependent variable. All statistical comparisons were performed using R software, version 3.6.2 (2019).

Results

Medial temporal atrophy

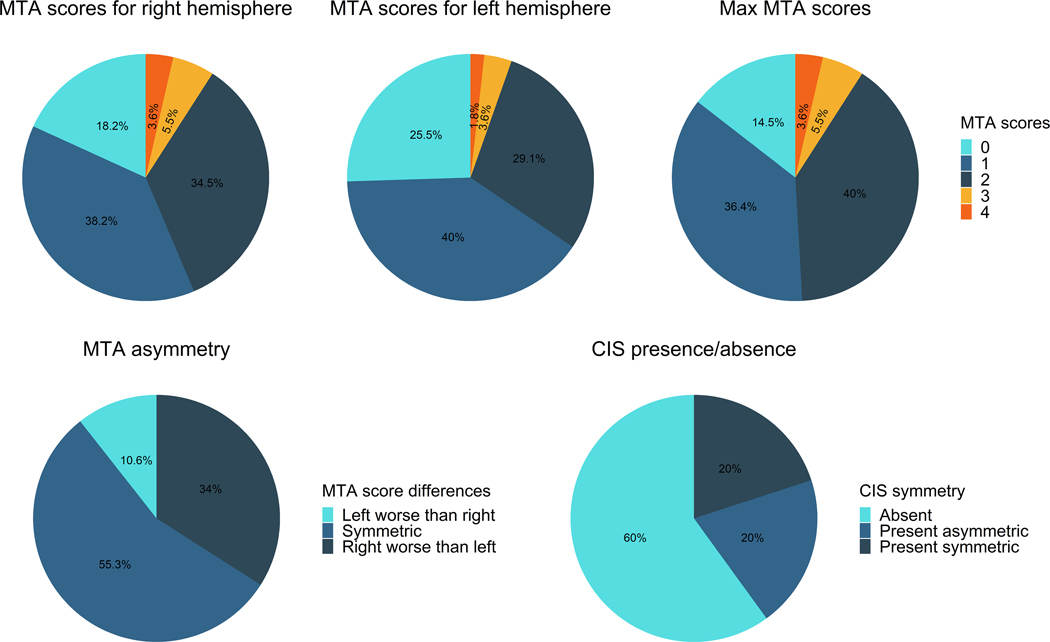

Demographic and clinical data is shown in Table 1. The most common rating of medial temporal atrophy for both the left and right hemisphere was mild atrophy (occurring in 38% of patients on the right and 40% of the left), followed by moderate atrophy (35% on the right and 29% on the left), and then no atrophy (18% on right, 25% on left) (Figure 2). Marked or severe atrophy was only observed in 9% of patients on the right and 5% of patients on the left. Of the 55 PCA patients, eight (15%) showed no medial temporal atrophy in either hemisphere. Of the remaining 47 patients that had some atrophy, 26 (55%) showed symmetric atrophy while 21 (45%) showed asymmetric atrophy (16 showing right worse than left and 5 showing left worse than right) (Figure 2). Of the asymmetric patients, all but one only had a one-point difference between hemispheres.

Table 1:

PCA patient data split by medial temporal atrophy score

| Characteristic | All N=55 | MTA=0 N = 8 | MTA=1 N = 20 | MTA=2 N = 22 | MTA=3 or 4 N = 5 | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.5 | |||||

| F | 35 (64%) | 6 (75%) | 10 (50%) | 15 (68%) | 4 (80%) | |

| M | 20 (36%) | 2 (25%) | 10 (50%) | 7 (32%) | 1 (20%) | |

| Education, years | 15.6 (2.7) | 15.6 (2.9) | 15.8 (2.7) | 15.1 (2.7) | 16.5 (3.4) | 0.8 |

| APOE e4 positive | 0.2 | |||||

| 0 | 22 (44%) | 6 (75%) | 9 (47%) | 6 (32%) | 1 (25%) | |

| 1 | 28 (56%) | 2 (25%) | 10 (53%) | 13 (68%) | 3 (75%) | |

| Handedness | >0.9 | |||||

| L | 5 (9%) | 1 (12%) | 2 (10%) | 2 (9.1%) | 0 (0%) | |

| L/R | 1 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (4.5%) | 0 (0%) | |

| R | 49 (89%) | 7 (88%) | 18 (90%) | 19 (86%) | 5 (100%) | |

| Global PiB SUVR | 2.4 (0.3) | 2.4 (0.3) | 2.3 (0.3) | 2.5 (0.4) | 2.4 (0.4) | 0.2 |

| Age at onset, years | 59.4 (7.0) | 53.6 (2.6) | 58.7 (6.8) | 60.8 (7.2) | 65.2 (5.5) | 0.001a,d |

| Age at scan, years | 64.1 (6.8) | 58.2 (3.2) | 63.2 (6.5) | 65.9 (6.6) | 69.7 (6.3) | <0.001a,d |

| Onset to scan, years | 4.2 (2.5) | 4.1 (1.4) | 3.9 (2.6) | 4.6 (2.9) | 4.1 (1.5) | 0.7 |

| MoCA | 16.7 (6.1) | 17.9 (4.7) | 19.4 (4.5) | 12.9 (6.3) | 20.5 (5.4) | 0.035b,c |

| CDR-SB | 4.2 (3.9) | 2.4 (1.0) | 3.1 (2.7) | 5.8 (5.3) | 4.8 (2.4) | 0.013 |

| MDS-UPDRS III | 4.8 (7.7) | 2.0 (3.2) | 4.0 (8.5) | 7.0 (8.2) | 2.2 (4.5) | 0.3 |

| WAB praxis | 55.8 (5.3) | 56.6 (4.3) | 56.5 (5.7) | 54.9 (4.3) | 55.2 (9.1) | 0.3 |

| AVLT-DR | 2.8 (3.3) | 5.3 (2.4) | 3.5 (4.3) | 1.6 (2.0) | 2.0 (3.4) | 0.008a |

| BNT | 11.5 (3.0) | 12.2 (1.9) | 11.9 (3.1) | 10.6 (3.2) | 12.0 (4.2) | 0.3 |

| Rey O | 4.0 (5.1) | 2.6 (2.2) | 4.8 (5.1) | 4.2 (6.5) | 2.0 (2.0) | 0.5 |

| VOSP cubes | 2.1 (2.4) | 2.3 (2.6) | 1.9 (2.1) | 2.2 (2.8) | 2.0 (2.6) | 0.7 |

| VOSP letters | 10.1 (6.6) | 10.2 (7.1) | 11.6 (5.5) | 9.2 (7.1) | 6.3 (10.1) | 0.5 |

| Auditory attention span * | 5.8 (1.5) | 6.2 (1.0) | 5.8 (1.4) | 5.6 (1.8) | 7.0 (0.0) | 0.7 |

Data shown as mean (standard deviation) or N(%). Categorical variables were compared with Fisher’s exact test; continuous variables were compared using Spearman Correlations (education, age and onset to scan) or linear regression corrected for age at scan (for all clinical tests). Pairwise comparisons were performed using a Tukey’s Honest Significant Difference test.

Pairwise differences between MTA 0 and MTA 2

Pairwise differences between MTA 1 and MTA 2

Pairwise differences between MTA 2 and MTA 3 or 4

Pairwise differences between MTA 0 and MTA 3 or 4

Auditory attention span was tested using the WMS digit span forward longest span APOE = apolipoprotein E; AVLT-DR = Auditory Verbal Learning Test Delayed Recall; BNT = Boston Naming Test; CDR-SB = Clinical Dementia Rating scale sum of boxes; MDS-UPDRS III = Movement Disorders Society Sponsored revision of the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale; MoCA = Montreal Cognitive Assessment Battery; PiB = Pittsburgh Compound B; Rey-O = Rey Osterrieth complex figure copy; SUVR = standard uptake value ratio; VOSP = Visual Object and Space Perception battery; WAB = Western Aphasia Battery; WMS = Wechsler Memory Scale

Figure 2: Pie-charts illustrating the medial temporal atrophy breakdown and CIS findings across the 55 patients.

The Max MTA scores are calculated by taking the highest medial temporal rating obtained for either hemisphere for each patient (i.e. a patient with a score of 1 for the left and 2 for the right will get a max MTA score of 2). The MTA asymmetry pic chart only includes PCA patients that had evidence of medial temporal atrophy (score≥ 1) in either hemisphere (n=47).

A relationship was observed between medial temporal atrophy severity and age, whereby more severe atrophy was associated with older age at onset and age at scan (Table 1). Worse medial temporal atrophy was also associated with worse performance on the CDR-SB, MoCA and AVLT-DR (Table 1). On pair-wise testing, the moderate medial temporal atrophy group showing worse performance on MoCA and AVLT-DR compared to the other groups.

CIS and medial temporal atrophy

The cingulate island sign was observed in 22 (44%) PCA patients. In these 22, the CIS was symmetric in 11 (50%) and asymmetric in 11 (50%) (Figure 2). There were no demographic or clinical differences between patients with and without a CIS (Table 2).

Table 2:

PCA patient data split by presence or absence of a CIS

| Characteristic | Absent, N = 33 | Present, N = 22 | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.2 | ||

| F | 24 (73%) | 11 (50%) | |

| M | 9 (27%) | 11 (50%) | |

| Education, years | 15.7 (2.6) | 15.3 (2.9) | 0.6 |

| APOE e4 positive | >0.9 | ||

| 0 | 13 (45%) | 9 (43%) | |

| 1 | 16 (55%) | 12 (57%) | |

| Handedness | 0.3 | ||

| L | 4 (12%) | 1 (4.5%) | |

| L/R | 0 (0%) | 1 (4.5%) | |

| R | 29 (88%) | 20 (91%) | |

| Global PiB SUVR | 2.4 (0.3) | 2.3 (0.4) | 0.3 |

| Age at onset, years | 60.3 (7.3) | 58.0 (6.4) | 0.2 |

| Age at scan, years | 65.1 (6.9) | 62.6 (6.4) | 0.2 |

| Onset to scan, years | 4.3 (2.6) | 4.2 (2.4) | 0.9 |

| MoCA | 17.2 (6.2) | 16.0 (6.0) | 0.5 |

| CDR-SB | 4.0 (3.8) | 4.5 (4.2) | 0.6 |

| MDS-UPDRS III | 5.1 (8.8) | 4.2 (5.8) | 0.7 |

| WAB praxis | 55.9 (5.9) | 55.7 (4.4) | 0.9 |

| AVLT-DR | 3.0 (3.7) | 2.6 (2.7) | 0.6 |

| BNT | 11.2 (3.4) | 11.9 (2.3) | 0.4 |

| Rey O | 4.8 (6.0) | 2.7 (3.3) | 0.1 |

| VOSP cubes | 2.2 (2.4) | 1.9 (2.4) | 0.8 |

| VOSP letters | 10.7 (6.8) | 9.2 (6.4) | 0.5 |

| Auditory attention span * | 6.0 (1.5) | 5.5 (1.3) | 0.4 |

Data shown as mean (standard deviation). P values calculated using two sample t-tests or Chi-squared tests.

Auditory attention span was tested using the WMS digit span forward longest span. APOE = apolipoprotein E; AVLT-DR = Auditory Verbal Learning Test Delayed Recall; BNT = Boston Naming Test; CDR-SB = Clinical Dementia Rating scale sum of boxes; MDS-UPDRS III = Movement Disorders Society Sponsored revision of the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale; MoCA = Montreal Cognitive Assessment Battery; PiB = Pittsburgh Compound B; Rey-O = Rey Osterrieth complex figure copy; SUVR = standard uptake value ratio; VOSP = Visual Object and Space Perception battery; WAB = Western Aphasia Battery; WMS = Wechsler Memory Scale

The medial temporal atrophy scores did not differ in the patients with a CIS compared to those without a CIS for the right or left hemisphere (p=0.12 and p=0.08) (Table 3). There was, however, a significant difference in medial temporal asymmetry, with those patients with a CIS showing more asymmetric medial temporal lobes compared to those without a CIS (p=0.039) (Table 3). Furthermore, the proportion of cases with asymmetric medial temporal lobes was greater in those with a CIS compared to those without a CIS (p=0.04). The significance increased when the patients without any medial temporal atrophy were removed (t-test p=0.02, chi-square p=0.008) (Table 3). Within those patients with a CIS, there was no relationship between CIS asymmetry and medial temporal asymmetry; with medial temporal asymmetry occurring in 55% of patients with a symmetric CIS and 55% of patients with an asymmetric CIS.

Table 3:

Medial temporal results by presence of CIS

| MTA measure | Absent CIS N=33 | Present CIS N=22 | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| MTA score - left | 1.33 | 0.91 | 0.077 |

| MTA score - right | 1.55 | 1.14 | 0.1 |

| % for each MTA score (max) * | 0.8 | ||

| 0 | 4 (12%) | 4 (18%) | |

| 1 | 12 (36%) | 8 (36%) | |

| 2 | 13 (39%) | 9 (41%) | |

| 3 or 4 | 4 (12%) | 1 (5%) | |

| MTA asymmetry | 0.27 | 0.59 | 0.039 |

| MTA asymmetry (only in max≥1) | 0.31 | 0.72 | 0.016 |

| % cases with MTA asymmetry | 9 (27%) | 12 (55%) | 0.041 |

| % cases with MTA asymmetry (only in max≥1) | 8/29 (28%) | 12/18 (67%) | 0.008 |

Data shown as mean (standard deviation). P values calculated using two sample t-tests or Chi-squared tests.

Calculated using the maximum score obtained from each hemisphere per patient. MTA = medial temporal atrophy

There was no association between hippocampal volume and the quantitative CIS (p=0.056 for right, p=0.11 for left).

Discussion

This study demonstrates that patients with PCA commonly have mild or moderate medial temporal atrophy which is strongly associated with age. There was no evidence to support the hypothesis that presence of the CIS on FDG-PET is related to sparing of the medial temporal lobe in PCA. Instead, presence of the CIS appeared to be related to asymmetric medial temporal atrophy.

The focus of neurodegeneration in PCA is observed in the cortex, with striking involvement of the occipital and parietal lobes, with the medial temporal lobes showing relative sparing [3–5, 12]. The medial temporal lobes have, therefore, received less attention in the field. We found that it is relatively rare for a PCA patient to have normal medial temporal lobes, with only 15% showing no medial temporal atrophy in either hemisphere. It was also rare for a PCA patient to have marked or severe atrophy, occurring in only 9% of our patients; most patients showed mild or moderate medial temporal atrophy. Asymmetry was also very common in the medial temporal lobe and was more often worse in the right hemisphere. Interestingly, cortical atrophy and hypometabolism in PCA is also often worse in the right hemisphere[3–5, 9]. One potential reason why PCA patients tend to show right-sided neurodegeneration is that patients with left predominant patterns will be more likely to show language impairment and hence receive a diagnosis of aphasia or the language variant of AD. Older age was associated with more severe medial temporal atrophy in our PCA cohort. A similar relationship has previously been observed in patients with typical amnestic AD, whereby late-onset patients have greater hippocampal atrophy than early-onset patients[30, 31]. Findings have been less clear within atypical AD cohorts. We recently reported that the associated between age and hippocampal volume was less striking in atypical presentations of AD than in typical AD, although there was a tendency for smaller volumes with older age[12]. However, in another previous study we did not find that age was associated with medial temporal volume in PCA[32]. Discrepancies between this study and our previous study may be because of the different methodological approaches to assess the medial temporal lobe. It is important to note that parietal and occipital neurodegeneration tends to be more severe in younger PCA patients[32–34]. Hence, our findings concerning the medial temporal lobe are not likely driven by general severity of neurodegeneration across the brain.

We found evidence that medial temporal atrophy in PCA is associated with clinical measures, particularly the AVLT-DR, MoCA and CDR-SB. It is possible that memory impairment may be contributing to the CDR-SB and MoCA. These findings suggest that medial temporal atrophy contributes to verbal episodic memory impairment in PCA, as is the case in typical amnestic AD. Declines in memory performance were most severe in patients with moderate medial temporal atrophy. The small sample of patients with marked or severe atrophy may have biased results in that group. Two previous studies found that memory dysfunction may result from degeneration of the parietal lobes rather than the medial temporal lobes in PCA[35, 36]. The fact that even patients with no medial temporal atrophy had lower than normal performance in our study may support contributions from non-medial temporal regions to memory function.

We hypothesized that sparing of the medial temporal lobe in PCA would be related to presence of a CIS on FDG-PET since the CIS may reflect sparing of the posterior limbic system, as is observed in DLB[17, 18]. We did not, however, find evidence to support this hypothesis, with no relationship identified between medial temporal atrophy scores and the presence of a CIS. These results were validated with a quantitative approach which similarly did not find a relationship between hippocampal volume and the CIS. It is possible that we did not identify this association in PCA because all of our patients have underlying AD and most have involvement of the medial temporal lobe, whereas clinical DLB cohorts likely include patients with and without underlying AD which will give a bigger range in medial temporal atrophy and drive relationships with the CIS. It is also possible that the basis for the CIS in PCA differs from DLB[16, 19]. Studies show that posterior cingulate metabolism primarily relates to local atrophy and tau deposition[37, 38] rather than medial temporal volume in atypical AD[38], and hence the presence of a CIS in some patients may simple relate to variability in patterns of tau deposition in the posterior cingulate and precuneus/cuneus. It has also been hypothesized that the CIS could reflect preservation of the medial cholinergic pathway[19]. An intriguing finding from our study was that the patients with a CIS were more likely to have asymmetric medial temporal atrophy compared to the patients without a CIS which had more symmetric patterns of atrophy. The implications of this finding are unclear but suggest that there may be different hemispheric distributions of tau pathology in those patients with and without a CIS. Within those patients with a CIS we did not find a relationship between asymmetry in the CIS and asymmetry in the medial temporal lobe, suggesting that CIS asymmetry is not due to medial temporal asymmetry and further arguing against a link between the CIS and medial temporal atrophy in PCA. Future studies assessing tau-PET imaging will be helpful to further explore these findings.

The strengths of this study are the large cohort of well characterized PCA patients that had both 3T volumetric head MRI and FDG-PET and underlying AD pathology confirmed with PiB-PET. The use of a well-validated visual rating scale for medial temporal atrophy was also a strength and allowed us to identify and characterize the degree of medial temporal atrophy and asymmetry in a clinically meaningful way. However, the visual rating results regarding the relationship between the medial temporal lobe and CIS were very similar when using a quantitative approach.

Results from this study help further characterize the clinical spectrum of MRI findings in PCA and contribute to our understanding of the influence of age on neurodegeneration in PCA. This will have clinical utility by aiding in the interpretation of MRI in the diagnostic workup for PCA. This knowledge is also critical when considering and designing neuroimaging outcome measures for clinical treatment trials. Furthermore, our findings help further our understanding of the biology of and clinical interpretation of a CIS finding in patients with PCA.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by National Institutes of Health grant R01-AG50603 and the Alzheimer’s Association. We would like to acknowledge the Mayo High School mentorship program and Dr. Clifford Jack for use of ADIR image analysis pipelines.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest

References

- [1].Crutch SJ, Schott JM, Rabinovici GD, Murray M, Snowden JS, van der Flier WM, Dickerson BC, Vandenberghe R, Ahmed S, Bak TH, Boeve BF, Butler C, Cappa SF, Ceccaldi M, de Souza LC, Dubois B, Felician O, Galasko D, Graff-Radford J, Graff-Radford NR, Hof PR, Krolak-Salmon P, Lehmann M, Magnin E, Mendez MF, Nestor PJ, Onyike CU, Pelak VS, Pijnenburg Y, Primativo S, Rossor MN, Ryan NS, Scheltens P, Shakespeare TJ, Suarez Gonzalez A, Tang-Wai DF, Yong KXX, Carrillo M, Fox NC, Alzheimer’s Association IAAsD, Associated Syndromes Professional Interest A (2017) Consensus classification of posterior cortical atrophy. Alzheimers Dement 13, 870–884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Tang-Wai DF, Graff-Radford N, Boeve BF, Dickson DW, Parisi JE, Crook R, Caselli RJ, Knopman DS, Petersen RC (2004) Clinical, genetic, and neuropathologic characteristics of posterior cortical atrophy. Neurology 63, 1168–1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Lehmann M, Crutch SJ, Ridgway GR, Ridha BH, Barnes J, Warrington EK, Rossor MN, Fox NC (2011) Cortical thickness and voxel-based morphometry in posterior cortical atrophy and typical Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging 32, 1466–1476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Ossenkoppele R, Cohn-Sheehy BI, La Joie R, Vogel JW, Moller C, Lehmann M, van Berckel BN, Seeley WW, Pijnenburg YA, Gorno-Tempini ML, Kramer JH, Barkhof F, Rosen HJ, van der Flier WM, Jagust WJ, Miller BL, Scheltens P, Rabinovici GD (2015) Atrophy patterns in early clinical stages across distinct phenotypes of Alzheimer’s disease. Hum Brain Mapp 36, 4421–4437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Whitwell JL, Jack CR Jr., Kantarci K, Weigand SD, Boeve BF, Knopman DS, Drubach DA, Tang-Wai DF, Petersen RC, Josephs KA (2007) Imaging correlates of posterior cortical atrophy. Neurobiol Aging 28, 1051–1061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Whitwell JL, Graff-Radford J, Singh TD, Drubach DA, Senjem ML, Spychalla AJ, Tosakulwong N, Lowe VJ, Josephs KA (2017) (18)F-FDG PET in Posterior Cortical Atrophy and Dementia with Lewy Bodies. J Nucl Med 58, 632–638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Singh TD, Josephs KA, Machulda MM, Drubach DA, Apostolova LG, Lowe VJ, Whitwell JL (2015) Clinical, FDG and amyloid PET imaging in posterior cortical atrophy. J Neurol 262, 1483–1492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Agosta F, Mandic-Stojmenovic G, Canu E, Stojkovic T, Imperiale F, Caso F, Stefanova E, Copetti M, Kostic VS, Filippi M (2018) Functional and structural brain networks in posterior cortical atrophy: A two-centre multiparametric MRI study. Neuroimage Clin 19, 901–910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Nestor PJ, Caine D, Fryer TD, Clarke J, Hodges JR (2003) The topography of metabolic deficits in posterior cortical atrophy (the visual variant of Alzheimer’s disease) with FDG-PET. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 74, 1521–1529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Alladi S, Xuereb J, Bak T, Nestor P, Knibb J, Patterson K, Hodges JR (2007) Focal cortical presentations of Alzheimer’s disease. Brain 130, 2636–2645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Formaglio M, Costes N, Seguin J, Tholance Y, Le Bars D, Roullet-Solignac I, Mercier B, Krolak-Salmon P, Vighetto A (2011) In vivo demonstration of amyloid burden in posterior cortical atrophy: a case series with PET and CSF findings. J Neurol 258, 1841–1851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Josephs KA, Tosakulwong N, Graff-Radford J, Weigand SD, Buciuc M, Machulda MM, Jones DT, Schwarz CG, Senjem ML, Ertekin-Taner N, Kantarci K, Boeve BF, Knopman DS, Jack CR Jr., Petersen RC, Lowe VJ, Whitwell JL (2020) MRI and flortaucipir relationships in Alzheimer’s phenotypes are heterogeneous. Ann Clin Transl Neurol 7, 707–721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Gabere M, Thu Pham NT, Graff-Radford J, Machulda MM, Duffy JR, Josephs KA, Whitwell JL, for Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging I (2020) Automated Hippocampal Subfield Volumetric Analyses in Atypical Alzheimer’s Disease. J Alzheimers Dis 78, 927–937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Imamura T, Ishii K, Sasaki M, Kitagaki H, Yamaji S, Hirono N, Shimomura T, Hashimoto M, Tanimukai S, Kazui H, Mori E (1997) Regional cerebral glucose metabolism in dementia with Lewy bodies and Alzheimer’s disease: a comparative study using positron emission tomography. Neurosci Lett 235, 49–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Graff-Radford J, Murray ME, Lowe VJ, Boeve BF, Ferman TJ, Przybelski SA, Lesnick TG, Senjem ML, Gunter JL, Smith GE, Knopman DS, Jack CR Jr., Dickson DW, Petersen RC, Kantarci K (2014) Dementia with Lewy bodies: basis of cingulate island sign. Neurology 83, 801–809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Nedelska Z, Kantarci K (2019) Reply to letter: Basis of cingulate island sign may differ in dementia with lewy bodies and posterior cortical atrophy. Mov Disord 34, 761–762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Iizuka T, Kameyama M (2016) Cingulate island sign on FDG-PET is associated with medial temporal lobe atrophy in dementia with Lewy bodies. Ann Nucl Med 30, 421–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Nedelska Z, Senjem ML, Przybelski SA, Lesnick TG, Lowe VJ, Boeve BF, Arani A, Vemuri P, Graff-Radford J, Ferman TJ, Jones DT, Savica R, Knopman DS, Petersen RC, Jack CR, Kantarci K (2018) Regional cortical perfusion on arterial spin labeling MRI in dementia with Lewy bodies: Associations with clinical severity, glucose metabolism and tau PET. Neuroimage Clin 19, 939–947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Kameyama M, Iizuka T (2019) Validity of the posterior limbic circuitry hypothesis as a basis for the cingulate island sign. Mov Disord 34, 761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bedirian V, Charbonneau S, Whitehead V, Collin I, Cummings JL, Chertkow H (2005) The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc 53, 695–699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Hughes CP, Berg L, Danziger WL, Coben LA, Martin RL (1982) A new clinical scale for the staging of dementia. Br J Psychiatry 140, 566–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Goetz CG, Tilley BC, Shaftman SR, Stebbins GT, Fahn S, Martinez-Martin P, Poewe W, Sampaio C, Stern MB, Dodel R, Dubois B, Holloway R, Jankovic J, Kulisevsky J, Lang AE, Lees A, Leurgans S, LeWitt PA, Nyenhuis D, Olanow CW, Rascol O, Schrag A, Teresi JA, van Hilten JJ, LaPelle N (2008) Movement Disorder Society-sponsored revision of the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (MDS-UPDRS): scale presentation and clinimetric testing results. Movement disorders : official journal of the Movement Disorder Society 23, 2129–2170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Kertesz A (2007) Western Aphasia Battery (Revised), PsychCorp, San Antonio, Tx. [Google Scholar]

- [24].Kaplan E, Goodglass H, Weintraub S (2001) The Boston Naming Test (2nd Edition), Pro-ed, Austin, Tx. [Google Scholar]

- [25].Rey A (1964) L’examen clinique en psychologie, Presses Universitaires de France, Paris. [Google Scholar]

- [26].Warrington EK, James M (1991) The visual object and space perception battery, Thames Valley Test Company, Bury St Edmonds, UK. [Google Scholar]

- [27].Wechsler DA (1987) Wechsler Memory Scale Revised, Psychological Corporation, New York. [Google Scholar]

- [28].Scheltens P, Leys D, Barkhof F, Huglo D, Weinstein HC, Vermersch P, Kuiper M, Steinling M, Wolters EC, Valk J (1992) Atrophy of medial temporal lobes on MRI in “probable” Alzheimer’s disease and normal ageing: diagnostic value and neuropsychological correlates. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 55, 967–972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Lim SM, Katsifis A, Villemagne VL, Best R, Jones G, Saling M, Bradshaw J, Merory J, Woodward M, Hopwood M, Rowe CC (2009) The 18F-FDG PET cingulate island sign and comparison to 123I-beta-CIT SPECT for diagnosis of dementia with Lewy bodies. Journal of nuclear medicine : official publication, Society of Nuclear Medicine 50, 1638–1645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Dickerson BC, Brickhouse M, McGinnis S, Wolk DA (2017) Alzheimer’s disease: The influence of age on clinical heterogeneity through the human brain connectome. Alzheimers Dement (Amst) 6, 122–135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Frisoni GB, Testa C, Sabattoli F, Beltramello A, Soininen H, Laakso MP (2005) Structural correlates of early and late onset Alzheimer’s disease: voxel based morphometric study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 76, 112–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Whitwell JL, Martin P, Graff-Radford J, Machulda MM, Senjem ML, Schwarz CG, Weigand SD, Spychalla AJ, Drubach DA, Jack CR Jr., Lowe VJ, Josephs KA (2019) The role of age on tau PET uptake and gray matter atrophy in atypical Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement 15, 675–685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Suarez-Gonzalez A, Lehmann M, Shakespeare TJ, Yong KXX, Paterson RW, Slattery CF, Foulkes AJM, Rabinovici GD, Gil-Neciga E, Roldan-Lora F, Schott JM, Fox NC, Crutch SJ (2016) Effect of age at onset on cortical thickness and cognition in posterior cortical atrophy. Neurobiol Aging 44, 108–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].La Joie R, Visani AV, Lesman-Segev OH, Baker SL, Edwards L, Iaccarino L, Soleimani-Meigooni DN, Mellinger T, Janabi M, Miller ZA, Perry DC, Pham J, Strom A, Gorno-Tempini ML, Rosen HJ, Miller BL, Jagust WJ, Rabinovici GD (2021) Association of APOE4 and Clinical Variability in Alzheimer Disease With the Pattern of Tau- and Amyloid-PET. Neurology 96, e650–e661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Veldsman M, Zamboni G, Butler C, Ahmed S (2019) Attention network dysfunction underlies memory impairment in posterior cortical atrophy. Neuroimage Clin 22, 101773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Ahmed S, Loane C, Bartels S, Zamboni G, Mackay C, Baker I, Husain M, Thompson S, Hornberger M, Butler C (2018) Lateral parietal contributions to memory impairment in posterior cortical atrophy. Neuroimage Clin 20, 252–259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Sintini I, Schwarz CG, Martin PR, Graff-Radford J, Machulda MM, Senjem ML, Reid RI, Spychalla AJ, Drubach DA, Lowe VJ, Jack CR Jr., Josephs KA, Whitwell JL (2019) Regional multimodal relationships between tau, hypometabolism, atrophy, and fractional anisotropy in atypical Alzheimer’s disease. Hum Brain Mapp 40, 1618–1631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Strom A, Iaccarino L, Edwards L, Lesman-Segev OH, Soleimani-Meigooni DN, Pham J, Baker SL, Landau S, Jagust WJ, Miller BL, Rosen HJ, Gorno-Tempini ML, Rabinovici GD, La Joie R, the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging I (2021) Cortical hypometabolism reflects local atrophy and tau pathology in symptomatic Alzheimer’s disease. Brain.</References> [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]