Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Peer victimization is common among youth and associated with substance use. Yet, few studies have examined these associations longitudinally or the psychological processes whereby peer victimization leads to substance use. The current study examined whether peer victimization in early adolescence is associated with alcohol, marijuana, and tobacco use in mid- to late adolescence, as well as the role of depressive symptoms in these associations.

METHODS:

Longitudinal data were collected between 2004 and 2011 from 4297 youth in Birmingham, Alabama; Houston, Texas; and Los Angeles County, California. Data were analyzed by using structural equation modeling.

RESULTS:

The hypothesized model fit the data well (Root Mean Square Error of Approximation [RMSEA] = 0.02; Comparative Fit Index [CFI] = 0.95). More frequent experiences of peer victimization in the fifth grade were associated with greater depressive symptoms in the seventh grade (B[SE] = 0.03[0.01]; P < .001), which, in turn, were associated with a greater likelihood of alcohol use (B[SE] = 0.03[0.01]; P = .003), marijuana use (B[SE] = 0.05[0.01]; P < .001), and tobacco use (B[SE] = 0.05[0.01]; P < .001) in the tenth grade. Moreover, fifth-grade peer victimization was indirectly associated with tenth-grade substance use via the mediator of seventh-grade depressive symptoms, including alcohol use (B[SE] = 0.01[0.01]; P = .006), marijuana use (B[SE] = 0.01[0.01]; P < .001), and tobacco use (B[SE] = 0.02[0.01]; P < .001).

CONCLUSIONS:

Youth who experienced more frequent peer victimization in the fifth grade were more likely to use substances in the tenth grade, showing that experiences of peer victimization in early adolescence may have a lasting impact by affecting substance use behaviors during mid- to late adolescence. Interventions are needed to reduce peer victimization among youth and to support youth who have experienced victimization.

The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that pediatricians take steps to prevent, identify, and treat substance use, including alcohol, marijuana, and tobacco use, among youth because of its harmful effects on adolescent health and development.1-3 Alcohol and marijuana use are associated with physical injury (eg, motor vehicle accidents) and risky health behaviors (eg, condomless intercourse), and may interfere with brain development.1,2 Tobacco use is associated with respiratory illness and infection, development of nicotine addiction, and a lifetime risk of cancers and early death.3 A growing body of research suggests that youth who are targets of peer victimization, or intentionally harmful actions from other youth,4,5 are at risk of using and misusing substances.6-10 Yet, few studies have examined the processes whereby peer victimization leads to greater substance use among youth. The self-medication hypothesis posits that people engage in substance use to relieve painful emotions and/or control their feelings.11,12 Although these processes are understudied among youth, evidence suggests that internalizing problems, characterized by inhibition and negative mood states, plays a role in associations between peer victimization and substance use.7,13,14 In particular, peer victimization may promote depressive symptoms,15-18 which, in turn, may lead to greater youth substance use.19,20

Youth are typically at greatest risk of peer victimization during late childhood and early adolescence, with rates of victimization decreasing through the remainder of adolescence.4 Research suggests that certain youth experience more frequent peer victimization than their peers. For example, youth living with socially devalued, or stigmatized, characteristics (eg, sexual minority orientation, obesity, chronic health conditions) often experience more peer victimization than other youth 4,21,22 Moreover, some research suggests that boys experience more of some types of peer victimization than girls (eg, physical aggression)4,23 In contrast, substance use increases through adolescence. Substance use trajectories show marked increases in mid- to late adolescence, with many youth trying alcohol, marijuana, and tobacco by age 18.24-26 Given these trends of decreasing peer victimization and increasing substance use through adolescence, it is possible that associations between peer victimization and substance use emerge longitudinally. That is, youth who are bullied early in adolescence may be more likely to engage in substance use by mid- to late adolescence. Indeed, a small but growing body of work suggests that early experiences of peer victimization are linked to worse mental health and greater engagement in health risk behaviors during early adulthood 4,27 Little work to date has examined the longitudinal impact of peer victimization on substance use over the course of adolescence.

In the current study, we aimed to examine whether experiences of peer victimization in early adolescence are associated with alcohol, marijuana, and tobacco use by mid- to late adolescence. We hypothesized that depressive symptoms mediate this association, such that more frequent peer victimization leads to more depressive symptoms, and more depressive symptoms lead to greater likelihood of substance use. We therefore tested a longitudinal mediational model to determine whether peer victimization in the fifth grade is associated with a greater likelihood of substance use in the tenth grade via the mediator of depressive symptoms in the seventh grade. Given previous research on gender differences in peer victimization and substance use,7 we further explored whether the model differed between boys and girls. A better understanding of the long-term implications of peer victimization on substance use, as well as the role of depressive symptoms in these associations, may inform pediatricians’ efforts to address substance use among youth.

METHODS

Procedures and Participants

Data were drawn from Healthy Passages, a 3-wave longitudinal study of risk and protective factors in adolescent health.15,22,28,29 Participants were recruited from 25 contiguous public school districts in Los Angeles County, California; 10 contiguous districts in Birmingham, Alabama; and the largest district in Houston, Texas. Schools within districts were randomly sampled. Parents of all youth within sampled schools were invited to participate in the study. The baseline assessment included 5147 youth, 4297 of whom participated in all 3 waves of data collection.

Data were collected via computer-assisted personal interviews, as well as audio computer-assisted self-interviews for sensitive information (eg, substance use). Height and weight were measured to calculate BMI. Data collection started when students were in the fifth grade in August 2004 through September 2006, and continued 2 and then 3 years later when most students were in the seventh and tenth grades. Parents provided written informed consent, and youth provided assent. Study procedures were approved by institutional review boards at each study site and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Measures

Parents and youth provided information on sociodemographic characteristics in the fifth grade, including age, gender, race/ethnicity, chronic illnesses, highest educational achievement in the household, and family household income. Youth provided information on sexual orientation in the tenth grade, and were characterized as sexual minorities if they indicated that they were not 100% heterosexual or straight or not attracted only to the other sex.22 All other data, including substance use, peer victimization, and depressive symptoms, were collected from youth at all 3 time points.

Substance Use

Students were asked about their use of tobacco, alcohol, and marijuana in the past 30 days with items adapted from the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance Study.30 We focused on these substances because they are the most prevalent among adolescents, and we focused on the past 30 days to capture current substance use. Substance use data were analyzed dichotomously to represent no versus some recent use.

Peer Victimization

Youth reported on peer victimization that they have experienced at school and other places (but not at home with siblings) within the past 12 months in response to the 6-item Peer Experience Questionnaire.5 Example items include “How often do kids kick or push you in a mean way?” and “How often do kids tell nasty things about you to others?” Response options ranged from “never” (1) to “a few times a week” (5). The scale had adequate reliability (fifth-grade α = .85).

Depressive Symptoms

Depressive symptoms were measured with 6 items from the depressive subscale of the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children Predictive Scales (fifth-grade α = .62; seventh-grade α = .71).31

Data Analyses

Attrition from baseline to follow-up was low (16.5%), and the effects of attrition on the composition of the sample were accounted for by the use of longitudinal weights. In combination with baseline weights, these weights also accounted for sampling and nonresponse. We first characterized the sociodemographic characteristics of the sample in SPSS version 23 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY). We then examined all correlations among fifth-grade peer victimization, seventh-grade depressive symptoms, and tenth-grade substance use. Pearson’s correlations were used for correlations between continuous variables (ie, peer victimization and depressive symptoms), point-biserial correlations were used for correlations between continuous and dichotomous variables (eg, peer victimization and alcohol use), and Spearman’s ρ correlations were used for correlations between dichotomous variables (eg, alcohol use and marijuana use).

We conducted the remaining analyses as structural equation models in Mplus 7 (Muthén & Muthén, Los Angeles, CA). We first identified correlates of peer victimization by regressing fifth-grade peer victimization on all sociodemographic characteristics. Next, we modeled paths between fifth-grade peer victimization and seventh-grade depressive symptoms, and between seventh-grade depressive symptoms and tenth-grade substance use. We examined alcohol, marijuana, and tobacco use independently due to evidence suggesting heterogeneity in patterns of their use during adolescence,32,33 and given that screeners typically assess each substance used rather than their combination.34 Guided by recommendations for longitudinal mediation analyses,35 we controlled for previous time points of depressive symptoms and substance use (ie, the effect of fifth-grade depressive symptoms on seventh-grade depressive symptoms, and seventh-grade substance use on tenth-grade substance use). We further controlled for correlates of fifth-grade peer victimization and all remaining sociodemographic characteristics with tenth-grade substance use. We used bootstrapping to acquire bias-corrected indirect effects of fifth-grade peer victimization on tenth-grade substance use via seventh-grade depressive symptoms. Finally, we conducted a χ2 difference test to determine whether the model fit differently among boys versus girls.

RESULTS

Sociodemographic characteristics of participating youth are shown in Table 1. The sample was approximately evenly divided between boys (51.1%) and girls (48.9%). Youth were identified as Latino/Latina (44.4%), African American (29.1%), and white (22.1%). At baseline, 22.7% of youth had a chronic health condition and 25.3% were obese. The highest educational achievement in the household included some high school (23.1%), high school graduate (21.4%), some college (24.6%), and college graduate (28.9%). Most youth (62.4%) lived in a household with an annual income of <$50 000, including 37.9% with annual incomes <$25 000. In the tenth grade, 14.4% of youth were categorized as sexual minorities.

TABLE 1.

Sociodemographic Characteristics of Youth

| Values | |

|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), y | |

| Fifth grade | 10.6 (0.70) |

| Seventh grade | 12.6 (0.66) |

| Tenth grade | 15.6 (0.66) |

| Sex, % (n) | |

| Boys | 51.1 (2196) |

| Girls | 48.9 (2101) |

| Race/ethnicity, % (n) | |

| Latino | 44.4 (1907) |

| African American | 29.1 (1249) |

| White | 22.1 (949) |

| Other | 4.4 (191) |

| Sexual orientation, tenth grade, % (n) | |

| Heterosexual | 84.7 (3640) |

| Sexual minority | 14.4 (620) |

| Chronic health condition, % (n) | |

| No | 77.9 (3346) |

| Yes | 22.7 (968) |

| Obese, % (n) | |

| No | 67.8 (2902) |

| Yes | 25.3 (1081) |

| Highest educational achievement in household, % (n) | |

| Some high school | 23.1 (991) |

| High school graduate | 21.4 (919) |

| Some college | 24.6 (1059) |

| College graduate | 28.9 (1240) |

| Family household income, % (n) | |

| <$25K | 37.9 (1630) |

| $25–49 K | 24.5 (1054) |

| $50–99K | 16.4 (704) |

| >$100K | 12.4 (533) |

| Geographical setting, % (n) | |

| Birmingham, AL | 31.0 (1331) |

| Houston, TX | 34.6 (1487) |

| Los Angeles, CA | 34.4 (1478) |

Data are from fifth-grade interview unless otherwise noted. N = 4297.

As shown in Table 2, 24.0% of tenth-graders reported recent alcohol use, 15.2% reported marijuana use, and 11.7% reported tobacco use. Fifth-grade peer victimization was positively correlated with seventh-grade depressive symptoms (r = 19, P < .001), indicating that youth who experienced more frequent peer victimization in the fifth grade reported greater depressive symptoms in the seventh grade. In addition, seventh-grade depressive symptoms were positively but weakly correlated with tenth-grade alcohol use (r = 0.06, P < .001), marijuana use (r = 0.06, P < .001), and tobacco use (r = 0.07, P < .001), indicating that youth who reported greater depressive symptoms in the seventh grade were more likely to have used substances in the tenth grade.

TABLE 2.

Longitudinal Correlations Between Peer Victimization. Depressive Symptoms, and Substance Use

| Tenth-Grade | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Values | Fifth-Grade Peer Victimization |

Seventh-Grade Depressive Symptoms |

Alcohol Use | Marijuana Use | Tobacco Use | |

| Fifth-grade peer victimization, mean (SD) | 10.43 (4.82) | 1 | ||||

| Seventh-grade depressive symptoms, mean (SD) | 1.72 (1.66) | 0.19** | 1 | |||

| Tenth-grade, % (n) | ||||||

| Alcohol use | 24.0 (1027) | −0.02 | 0.06** | 1 | ||

| Marijuana use | 15.2 (628) | 0.02 | 0.06** | 0.40** | 1 | |

| Tobacco use | 11.7 (502) | 0.03 | 0.07** | 0.37** | 0.50** | 1 |

Ranges of scale scores were as follows: peer victimization, 6–30; depressive symptoms, 0–6. Substance use was dichotomized to represent use versus nonuse.

P ≤ .01.

Sexual minority youth (B[SE] = 0.96[0.26]; P < .001), youth living with chronic illnesses (B[SE] = 0.60[0.22]; P = .006), and boys (B[SE] = 1.13[0.17]; P < .001) reported more frequent peer victimization in the fifth grade. Age, obesity, race/ethnicity, household educational achievement, and family household income were not associated with frequency of peer victimization. We therefore controlled for the effects of sexual orientation, chronic illness status, and gender on peer victimization and the effects of all remaining sociodemographic characteristics on substance use in the structural equation model.

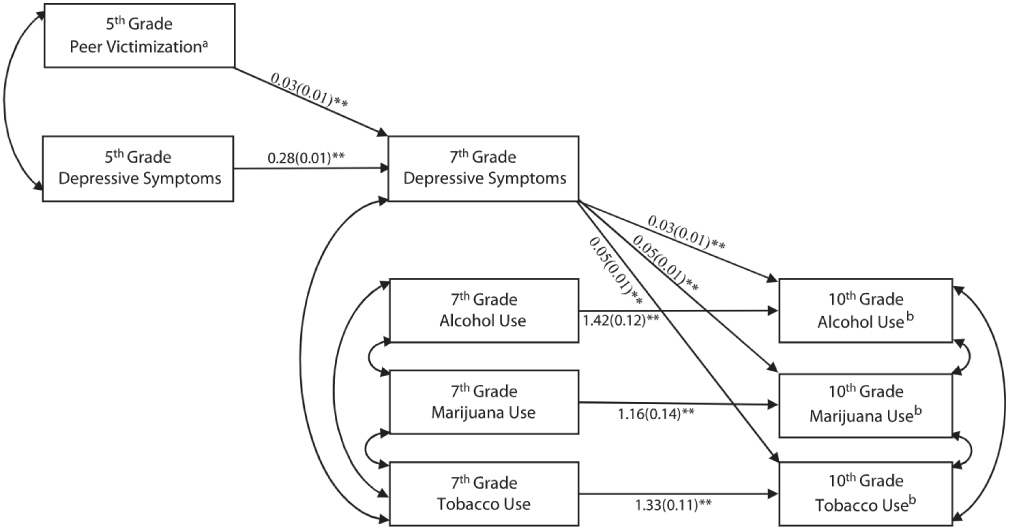

Results of the structural equation model are presented in Fig 1. The model fit the data well (Root Mean Square Error of Approximation [RMSEA] = 0.02; 95% confidence interval: 0.01–0.02; Comparative Fit Index [CFI] = 0.95; χ2[72] = 131.97; P < .01). More frequent fifth-grade peer victimization was associated with greater seventh-grade depressive symptoms (B[SE] = 0.03[0.01]; P < .001), controlling for fifth-grade depressive symptoms. In turn, greater seventh-grade depressive symptoms were associated with a greater likelihood of tenth-grade alcohol use (B[SE] = 0.03[0.01]; P = .003), marijuana use (B[SE] = 0.05[0.01]; P < .001), and tobacco use (B[SE] = 0.05[0.01]; P < .001), controlling for seventh-grade alcohol, marijuana, and tobacco use. The analysis of indirect effects estimated with bootstrapping revealed that fifth-grade peer victimization was associated with tenth-grade substance use via the mediator of seventh-grade depressive symptoms, including alcohol use (B[SE] = 0.01[0.01]; P = .006), marijuana use (B[SE] = 0.01[0.01]; P < .001), and tobacco use (B[SE] = 0.02[0.01]; P < .001). Therefore, more frequent experiences of peer victimization in the fifth grade were associated with greater depressive symptoms in the seventh grade, which, in turn, were associated with a greater likelihood of substance use in the tenth grade. As indicated by the R2 statistics, the model accounted for modest percentages of the variance in substance use (alcohol = 10.8% [SE = 0.02], marijuana = 4.0% [SE = 0.01], and tobacco = 9.1% [SE = 0.02]).

FIGURE 1.

Longitudinal structural equation model of associations between peer victimization, depressive symptoms, and substance use. Values are unstandardized regression coefficients (SEs). **P ≤ .01. a Controlling for gender, sexual orientation, and chronic illness. b Controlling for age, obesity, race/ethnicity, highest educational achievement in household, and family household income. Model fit indices: RMSEA = 0.02 (95% confidence interval: 0.01–0.02); CFI = 0.95; χ2(72) = 131.97; P < .01. CFI, Comparative Fit Index; RMSEA, Root Mean Square Error of Approximation.

The χ2 difference test suggested that the overall model fit differently for boys and girls (χ2[36] = 59.77; P = .01). The main paths of interest were similar for boys and girls, with statistically significant associations between fifth-grade peer victimization with seventh-grade depressive symptoms, and seventh-grade depressive symptoms with tenth-grade substance use. Associations between substance use and 1 of the control variables, however, differed between boys and girls. Specifically, sexual minority status was more strongly related to alcohol use among girls than boys (B[SE] = 0.23[0.10]; P = .02 versus B[SE] = 0.14[0.05]; P = .01); it was also related to greater likelihood of marijuana and tobacco use among girls but unrelated to these types of substance use among boys (marijuana: B[SE] = 0.30[0.11]; P = .01 among girls versus B[SE] = −0.01[0.04]; P = .94 among boys; tobacco: B[SE] = 0.13[0.07]; P = .05 among girls versus B[SE] = −0.04[0.03]; P = .24 among boys). An additional χ2 test including the main paths between fifth-grade peer victimization, seventh-grade depressive symptoms, and tenth-grade substance use, and excluding the controls, suggested that the model fit similarly for boys and girls (χ2[4] = 6.10; P = .19).

DISCUSSION

The current study indicates that experiences of peer victimization in early adolescence may have a lasting impact, affecting mental health and substance use behaviors during mid- to late adolescence. More specifically, our results from 3 US metropolitan areas show that youth who experience more frequent peer victimization in the fifth grade are more likely to engage in alcohol, marijuana, and tobacco use in the tenth grade. The mediational pathways are consistent for all examined substances; more frequent experiences of peer victimization in the fifth grade are associated with more depressive symptoms in the seventh grade, which, in turn, are associated with a greater likelihood of substance use in the tenth grade. Associations are similar for boys and girls. These findings are consistent with the self-medication hypothesis of substance use, which suggests that individuals engage in substance use to cope with or relieve painful emotions.11,12 Of note, sexual minority youth, youth living with chronic illnesses, and boys in our sample reported more frequent bullying in the fifth grade than their peers.

This study addresses important gaps in the literature on associations between peer victimization and substance use. To date, the majority of work examining these associations has been cross-sectional.7 Our study adds to a small, but growing, body of research examining longitudinal associations between peer victimization and substance use across adolescence. The longitudinal design allowed us to show that fifth-grade peer victimization contributes to seventh-grade depressive symptoms above and beyond the substantial effect of fifth-grade depressive symptoms on seventh-grade depressive symptoms, and similarly, seventh-grade depressive symptoms contribute to tenth-grade substance use above and beyond the substantial effect of seventh-grade substance use on tenth-grade substance use. A recent review article identified only 1 other study that examined whether internalizing symptoms mediate associations between peer victimization and substance use among youth.7,16 This work identified depressive symptoms as a mediator, but relied on cross-sectional data with tenth-grade students. Our work provides additional support for these findings with longitudinal data drawn from a multisite study with a diverse sample of 4297 youth, enhancing confidence in the generalizability of results.

This study used self-report measures of engagement in substance use in the past 30 days. Yet, validated measures were used from the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance Study,30 and rates of reported substance use were comparable to national samples.32 In addition, our measures do not differentiate between substance use and substance misuse or disordered use. Understanding the role of peer victimization in the development of substance use disorders is an important area for future research.

We focused on understanding the role of depressive symptoms in associations between peer victimization and substance use. It has been proposed that other processes, such as traumatic stress, poor academic achievement, and absenteeism, may further play important roles in associations between peer victimization and substance use.7 In addition, youth involved in peer victimization as both targets and perpetrators may be at particularly high risk of substance use.36 Sociodemographic and/or stigmatized characteristics, such as sexual minority orientation, as well as psychosocial processes, such as social support and school connectedness, may moderate these associations.7 More work is needed to continue to understand why peer victimization, including victimization and perpetration of harmful behavior, is associated with substance use and to better characterize for which youth the association is strongest. Future analyses that include more variables relevant to these associations may account for a greater percentage of the variance in substance use than the current model.

Moreover, research may continue to examine why certain youth are at greater risk of peer victimization and, in turn, its negative health sequelae. For example, youth in the current study who identified as sexual minorities in the tenth grade had experienced more frequent bullying in the fifth grade, likely before many had disclosed or recognized their minority sexual orientation.22,37 Nonconforming gender expression may play a role in these youth’s experiences of peer victimization: gender-nonconforming youth are at greater risk of peer victimization due to their real or perceived sexual minority orientation.38

CONCLUSIONS

Pediatricians have an opportunity to play an important role in supporting youth experiencing peer victimization.39-40 All youth should be screened for peer victimization, depressive symptoms, and substance use in health care settings. Pediatricians might offer counsel to youth experiencing victimization, including recommendations regarding approaching teachers and other school staff for support, given that supportive adults at school can buffer youth from the effects of peer victimization on substance use.8 Moreover, youth experiencing depressive symptoms and substance use should be offered treatment when needed. Ultimately, pediatricians, parents, and school representatives can work together to address peer victimization and prevent substance use among youth.

WHAT’S KNOWN ON THIS SUBJECT:

Peer victimization is common among youth and appears to be associated with increased substance use. Yet, few studies have examined these associations longitudinally or the psychological processes whereby peer victimization leads to substance use.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS:

Experiences of peer victimization in early adolescence have a lasting impact, affecting mental health and substance use behaviors during mid- to late adolescence.

FUNDING:

The Healthy Passages study was funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (cooperative agreements CCU409679, CCU609653, CCU915773, U48DP000046, U48DP000057, U48DP000056, U19DP002663, U19DP002664, and U19DP002665). Dr Earnshaw’s effort was supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (K12HS022986).

Footnotes

Dr Earnshaw conceptualized the research questions, led the statistical analyses and interpretation of the data, and drafted the manuscript; Drs Elliott, Reisner, Mrug, Windle, and Schuster contributed to refining the research questions and statistical analyses and interpreting the data; Drs Elliott, Windle, Emery, and Schuster conceptualized and designed the overall study; Drs Elliott, Mrug, Windle, Emery, Peskin, and Schuster acquired the data; Dr Schuster supervised all aspects of the study; and all authors contributed to the revising of the manuscript, gave final approval of the manuscript as submitted, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST: The authors have indicated they have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kokotailo PK; Committee on Substance Abuse. Alcohol use by youth and adolescents: a pediatric concern. Pediatrics. 2010;125(5):1078–1087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ammerman S, Ryan S, Adelman WP; Committee on Substance Abuse; Committee on Adolescence. The impact of marijuana policies on youth: clinical, research, and legal update. Pediatrics. 2015;135(3):e20144146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Binns HJ, Forman JA, Karr CJ, et al. ; Committee on Environmental HealthHealth; Committee on Substance Abuse; Committee on Adolescence; Committee on Native American Child. Tobacco use: a pediatric disease [policy statement]. Pediatrics. 2009;124(5):1474–1487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Juvonen J, Graham S. Bullying in schools: the power of bullies and the plight of victims. Annu Rev Psychol. 2014;65(1):159–185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Prinstein MJ, Boergers J, Vernberg EM. Overt and relational aggression in adolescents: social-psychological adjustment of aggressors and victims. J Clin Child Psychol. 2001;30(4):479–491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fleming LC, Jacobsen KH. Bullying among middle-school students in low and middle income countries. Health Promot Int. 2010;25(1):73–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hong JS, Davis JP, Sterzing PR, Yoon J, Choi S, Smith DC. A conceptual framework for understanding the association between school bullying victimization and substance misuse. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2014;84(6):696–710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Earnshaw VA, Rosenthal L, Carroll-Scott A, Peters SM, McCaslin C, lckovics JR. Teacher involvement as a protective factor from the association between race-based bullying and smoking initiation. Soc Psychol Educ. 2014;17(2):197–209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Niemelä S, Brunstein-Klomek A, Sillanmäki L, et al. Childhood bullying behaviors at age eight and substance use at age 18 among males: a nationwide prospective study. Addict Behav. 2011;36(3):256–260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tharp-Taylor S, Haviland A, D’Amico EJ. Victimization from mental and physical bullying and substance use in early adolescence. Addict Behav. 2009;34(6–7):561–567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khantzian EJ. The self-medication hypothesis of addictive disorders: focus on heroin and cocaine dependence. Am J Psychiatry. 1985;142(11):1259–1264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khantzian EJ. The self-medication hypothesis of substance use disorders: a reconsideration and recent applications. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 1997;4(5):231–244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.King SM, Iacono WG, McGue M. Childhood externalizing and internalizing psychopathology in the prediction of early substance use. Addiction. 2004;99(12):1548–1559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tandon M, Cardeli E, Luby J. Internalizing disorders in early childhood: a review of depressive and anxiety disorders. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2009;18(3):593–610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bogart LM, Elliott MN, Klein DJ, et al. Peer victimization in fifth grade and health in tenth grade. Pediatrics. 2014;133(3):440–447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Luk JW, Wang J, Simons-Morton BG. Bullying victimization and substance use among U.S. adolescents: mediation by depression. Prev Sci. 2010;11(4):355–359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Salmon G, James A, Smith DM. Bullying in schools: self reported anxiety, depression, and self esteem in secondary school children. BMJ. 1998;317(7163):924–925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Seals D, Young J. Bullying and victimization: prevalence and relationship to gender, grade level, ethnicity, self-esteem, and depression. Adolescence. 2003;38(152):735–747 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Diego MA, Field TM, Sanders CE. Academic performance, popularity, and depression predict adolescent substance use. Adolescence. 2003;38(149):35–42 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Acierno R, Kilpatrick DG, Resnick H, Saunders B, De Arellano M, Best C. Assault, PTSD, family substance use, and depression as risk factors for cigarette use in youth: findings from the national survey of adolescents. J Trauma Stress. 2000;13(3):381–396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Russell ST, Sinclair KO, Poteat VP, Koenig BW. Adolescent health and harassment based on discriminatory bias. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(3):493–495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schuster MA, Bogart LM, Elliott MN, et al. A longitudinal study of bullying of sexual-minority youth. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(19):1872–1874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nansel TR, Overpeck M, Pilla RS, Ruan WJ, Simons-Morton B, Scheidt P. Bullying behaviors among US youth: prevalence and association with psychosocial adjustment. JAMA. 2001;285(16):2094–2100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kann L, Kinchen S, Shanklin SL, et al. ; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance–United States, 2013. MMWR Suppl. 2014;63(4):1–168 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maggs JL, Schulenberg JE. Trajectories of alcohol use during the transition to adulthood. Alcohol Res Health. 2004;28:195–201 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Flory K, Lynam D, Milich R, Leukefeld C, Clayton R. Early adolescent through young adult alcohol and marijuana use trajectories: early predictors, young adult outcomes, and predictive utility. Dev Psychopathol. 2004;16(1):193–213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Russell ST, Ryan C, Toomey RB, Diaz RM, Sanchez J. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender adolescent school victimization: implications for young adult health and adjustment. J Sch Health. 2011;81(5):223–230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Windle M, Grunbaum JA, Elliott M, et al. Healthy Passages: a multilevel, multimethod longitudinal study of adolescent health. Am J Prev Med. 2004;27(2):164–172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schuster MA, Elliott MN, Kanouse DE, et al. Racial and ethnic health disparities among fifth-graders in three cities. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(8):735–745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grunbaum JA, Kann L, Kinchen SA, et al. Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance—United States, 2001. J Sch Health. 2002;72(8):313–328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lucas CP, Zhang H, Fisher PW, et al. The DISC Predictive Scales (DPS): efficiently screening for diagnoses. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;40(4):443–449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, et al. Monitoring the Future National Results on Adolescent Drug Use: Overview of Key Findings. Ann Arbor, Ml: Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan; 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moss HB, Chen CM, Yi HY. Early adolescent patterns of alcohol, cigarettes, and marijuana polysubstance use and young adult substance use outcomes in a nationally representative sample. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014;136:51–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Levy SJ, Williams JF; Committee on Substance Use and Prevention. Substance use screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment. Pediatrics. 2016;138(1):e20161211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maxwell SE, Cole DA. Bias in cross-sectional analyses of longitudinal mediation. Psychol Methods. 2007;12(1):23–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Radliff KM, Wheaton JE, Robinson K, Morris J. Illuminating the relationship between bullying and substance use among middle and high school youth. Addict Behav. 2012;37(4):569–572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Floyd FJ, Bakeman R. Coming-out across the life course: implications of age and historical context. Arch Sex Behav. 2006;35(3):287–296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Toomey RB, Ryan C, Diaz RM, Card NA, Russell ST. Gender-nonconforming lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth: school victimization and young adult psychosocial adjustment. Dev Psychol. 2010;46(6):1580–1589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.American Academy of Pediatrics. The Resilience Project. Available at: https://www.aap.org/en-us/advocacy-and-policy/aap-health-initiatives/resilience/Pages/default.aspx. Accessed September 25, 2015

- 40.Stopbullying.gov 2014. Federal laws. Available at: www.stopbullying.gov/laws/federal/. Accessed September 22, 2015