Abstract

Background

Cough symptom severity represents an important subjective end-point to assess the impact of therapies for patients with refractory or unexplained chronic cough (RCC/UCC). As existing instruments assessing the severity of cough are neither widely available nor tested for measurement properties, we aim to develop a new patient-reported outcome measure addressing cough severity.

Objective

The aim of this study was to establish items and domains that would inform development of a new cough severity instrument.

Methods

Three focus groups involving 16 adult patients with RCC/UCC provided data that we analysed using directed content analysis. Discussions led to consensus among an international panel of 15 experts on candidate items and domains to assess cough severity.

Results

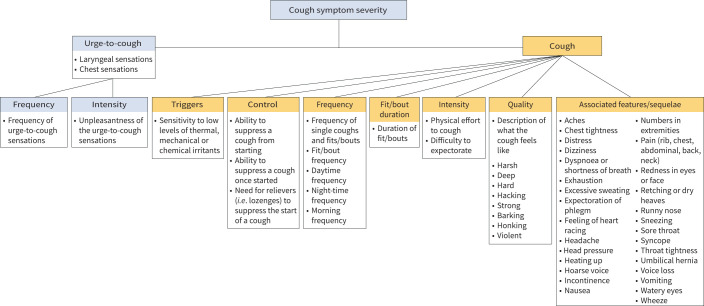

The patient focus group provided 48 unique items arranged under broad domains of urge-to-cough sensations and cough symptom. Feedback from expert panel members confirmed the appropriateness of items and domains, and provided an additional subdomain related to cough triggers. The final conceptual framework comprised 51 items in the following domains: urge-to-cough sensations (subdomains: frequency and intensity) and cough symptom (subdomains: triggers, control, frequency, fit/bout duration, intensity, quality and associated features/sequelae).

Conclusions

Consensus findings from patients and international experts established domains of urge-to-cough and cough symptom with associated subdomains and relevant items. The results support item generation and content validity for a novel patient-reported outcome measure for use in health research and clinical practice.

Short abstract

The urge-to-cough (subdomains: frequency and intensity) and cough symptom (subdomains: triggers, control, frequency, fit/bout duration, intensity, quality, and associated features/sequelae) represent domains to assess cough severity in RCC/UCC https://bit.ly/3fI6qkC

Introduction

Chronic cough lasting >8 weeks is a common health problem that affects 2–18% of adults worldwide [1]. Although clinicians can often identify and effectively treat known causes of cough—including asthma, COPD, bronchiectasis, gastro-oesophageal reflux disease and upper airway cough syndromes—many patients, despite treatment targeting these underlying conditions, experience refractory chronic cough (RCC) [2, 3]. In others, clinical assessment fails to identify a cause, and patients are classified with unexplained chronic cough (UCC) [2, 3]. Patients with RCC/UCC often exhibit cough hypersensitivity syndrome, defined as a troublesome cough triggered by low levels of thermal, mechanical or chemical irritants [4].

RCC/UCC can lead to significant impairment in quality of life (QoL); thus, QoL serves as an important end-point in establishing treatment impact. Cough-specific QoL measures, including the Leicester Cough Questionnaire [5], Cough Quality of Life Questionnaire [6] and Chronic Cough Impact Questionnaire [7], address the impact of cough symptoms on patients’ physical, social and psychological health. Such assessments, although crucial in addressing treatment impact, are limited in that they capture domains influenced by factors aside from cough symptom severity (i.e. psychosocial context). The same degree of cough in two patients can thus lead to substantially different responses regarding cough QoL. Neuromodulatory agents, such as pregabalin [8] and experimental neurokinin receptor antagonists [9], can improve cough QoL independent of cough suppression. Thus, full insight into therapeutic efficacy must, alongside cough QoL, include assessment of cough symptom severity.

Objective cough frequency using the VitaloJAK monitor represents the most common primary end-point in antitussive clinical trials [10]. Cough monitors provide direct insight into whether treatment improves cough frequency by quantifying spontaneous coughs over a defined period. Existing monitors are limited, however, in that they are typically only used over a 24-h period, they can pose a burden for patients to wear repeatedly and they are expensive to administer [11]. Furthermore, they cannot assess whether other dimensions of cough (i.e. intensity) may be improved with treatment. A measure that directly assesses patients’ experience of cough and sequelae (herein referred to as “symptom severity”) might address the limitations of currently available instruments.

The visual analogue scale (VAS) [12] and Cough Severity Diary (CSD) [13] represent existing instruments to assess cough severity. Limitations of the cough severity VAS include lack of evidence supporting its measurement properties and limitations of single-item instruments in fully capturing complex patient experiences [14]. While the CSD has undergone psychometric testing [15], it is currently a proprietary questionnaire with restrictions on use for clinical and research purposes. Furthermore, the CSD lacks conceptual clarity in that the domain “disruption” measures cough impact on daytime activities and sleep. A widely available instrument with established measurement properties that measures cough symptom severity rather than cough QoL remains unavailable.

We aim to develop a cough symptom severity instrument—the McMaster Cough Severity Questionnaire—for use in patients with RCC/UCC. To inform item generation for the instrument, we conducted a systematic survey in which we identified 43 items addressing the following domains: urge-to-cough sensations (subdomains: frequency and intensity) and cough symptom (subdomains: frequency, control, bout duration, intensity and associated features/sequelae) [16]. To assess the comprehensiveness and appropriateness of items, domains and subdomains identified in our systematic survey, we conducted patient focus groups and consultation with clinical experts, and report here our findings.

Methods

Patient focus groups

We conducted focus groups with patients with RCC/UCC to explore: 1) attributes of their cough and its severity; and 2) issues important to patients in relation to their cough severity. This report adheres to consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research standards [17].

Patient recruitment

We recruited 16 adult (≥18 years old) patients with RCC/UCC from a tertiary care clinic at the McMaster University Medical Centre (Hamilton, Ontario, Canada). Eligible patients experienced cough lasting >8 weeks. We excluded patients who currently smoked or had a smoking history of >10 pack-years; whose English was limited; or who presented with memory, cognitive or psychiatric issues preventing optimal participation. Patients provided written informed consent and received $50 for participating. The Hamilton Integrated Research Ethics Board provided ethics approval (No. 12-881).

Sample

We employed purposive sampling to obtain experiences among a diversity of patients with RCC/UCC [18]. Our sample size was based on the anticipated number of patients required to reach thematic saturation on the concept of cough symptom severity [19].

Group configuration and data collection

Following informed consent, a study coordinator (E.K.) contacted patients over the telephone to establish their age, sex, smoking history and comorbidities. The coordinator convened three focus groups, each with five to six patients.

Following a semi-structured guide (supplementary Appendix E1), a trained interview facilitator (E.K.) led the focus group discussions over Zoom videoconferencing, each for 60–90 min. A prior systematic survey [16] informed an initial draft of the interview guide that was subsequently revised based on input from the steering group (G.H.G., I.S.). The facilitator asked open-ended questions, followed by directed questions on themes identified from the systematic survey. As patients discussed, the facilitator identified emerging themes for further discussion. To ensure full exploration of themes, we provided patients with the opportunity to add comments at the end. Focus groups were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim and de-identified.

Data analysis

We used directed content analysis, informed by a prior conceptual framework [16], to identify related themes [20]. Two researchers (E.K., C.M.) independently coded transcripts by assigning statements to items or domains in the framework. The two researchers discussed statements that could not be categorised within existing items or domains, and if relevant, created a new code. Researchers then summarised these codes as a new item or domain contributing to our evolving conceptual framework. The study team, comprised of clinical experts, methodologists and patient partners, reviewed the results of the analysis, and resolved disagreements through discussion leading to consensus.

Expert consensus study

We elicited feedback from an international panel of chronic cough experts on the comprehensiveness and appropriateness of items and domains identified from the systematic survey and patient focus groups. Using purposive sampling, we invited 14 key opinion leaders in chronic cough, all of whom agreed to participate. The final group consisted of 18 members (the steering group: E.K., G.H.G., P.M.O.B., I.S., and 14 experts: R.A., H.B., L.P.B., R.C., P.D., L.D., S.K.F., .CL.F., P.G.G., R.S.I., P.M., L.M., J.A.S., W.J.S.). Experts came from the UK, USA, Canada and one each from Australia, Belgium, China, Ireland, Saudi Arabia and South Korea.

Pre-meeting survey and feedback

Without having seen our conceptual framework, expert panel members provided 3–10 questions to assess patients’ severity of cough. Once returned, the steering group then sent a draft conceptual framework, from which experts could provide written suggestions to either drop, merge and/or add items or domains.

Consensus meeting

The steering group and expert panel participated in a 1-hour videoconference to reach consensus on the items and domains for a cough symptom severity instrument. The steering group presented the results of the systematic survey, patient focus groups and pre-meeting feedback. Following presentation of the results, experts participated in discussions addressing the proposed items and domains. After the conference, the steering group sent expert panel members a report of the discussion and a modified list of items and domains based on their feedback. Experts had the opportunity, if desired, to provide additional written feedback.

Results

The 16 focus group patients had a median age of 61 years. Most identified as female (68.8%), reported no history of smoking (81.3%) and coughed for a median duration of 13.5 years (table 1).

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of focus group patients (n=16)

| Category | |

| Sex | |

| Male | 5 (31.3) |

| Female | 11 (68.8) |

| Age years | 61 (50–79) |

| Smoking status | |

| Never | 13 (81.3) |

| Former | 3 (18.8) |

| Duration of cough years | 13.5 (2–44) |

| Comorbidities | |

| Asthma | 1 (6.3) |

| Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease | 2 (12.5) |

| Chronic bronchitis | 1 (6.3) |

Data presented as n (%) or median (range).

Statements from patients provided 48 items that we categorised under two broad domains of cough symptom severity: urge-to-cough sensations (subdomains: frequency and intensity) and cough symptom (subdomains: control, frequency, fit/bout duration, intensity, quality and associated features/sequelae) (figure 1; table 2).

FIGURE 1.

Conceptual framework of cough symptom severity in patients with refractory or unexplained chronic cough (RCC/UCC).

TABLE 2.

Domains and items related to measurement of cough symptom severity in patients with refractory or unexplained chronic cough (RCC/UCC)

| Domain | Subdomain | Item | Example phrases |

| 1. Urge-to-cough sensations (i.e. laryngeal, chest) that can lead to cough | 1.1 Urge frequency | 1.1.1 Urge frequency | “I'm constantly feeling as though I want to clear the back of my throat and that's where the cough comes in and it's almost like… If I've cleared my throat for maybe just a moment or two it's almost like there's a sense of, ‘okay, I'm good’. But then almost as quickly as it's cleared, I feel like it's starting again so it's mostly in the background. I'm constantly feeling like I've got something in the back of my throat. And then, once it builds up to a certain point, I'm feeling like I just I am coughing” (Patient 3, male, age 53 years). “Okay, so there's not always, like I mentioned, any sensation or sign that it's going to come on. I do get sometimes that dry tickle [but] it's not consistent” (Patient 1, male, 44). “It's kind of like a constant tickle that I try to get rid of [and] if I don't, then I wind up coughing to try to get rid of it” (Patient 13, female, age 62 years). “The urge comes and then there's no stopping it once that urge is there. And the urge is there a lot” (Patient 12, female, age 75 years). |

| 1.2 Urge intensity | 1.2.1 Urge intensity | “For me, it would be definitely the tickle as a sensation that I get. That's the most common with my mild [coughs]. When I get into my severe [coughs] it could be a hostile tickle because of the laughing getting that tickle started. Even it's like a little bit of a pressure build up at the larynx or like I don't know… a little bit below Adam's apple there's a little bit of pressure builds up there just to start the hack attack or severe cough” (Patient 16, male, age 48 years). “Most of my severe coughs start with that karate chop effect, I was talking about… It can be just… boom it hits me, most of the severe ones start with that karate chop effect in my throat […] Another time I will feel pressure in my chest… like something… I feel just like someone's pushing with their hand down on my chest, and then that will start a cough as well. You know the pressure in my chest, next thing you know it goes more into my throat, and then I start coughing” (Patient 15, female, age 57 years). “I almost feel like my throat is closing by the time I get up in the morning, it feels kind of like where your trachea is that, it's almost like, full? Like the passageway, whether it's mucus or whatever it is, I went to the doctor and they said there's nothing there, but the same sensation is there, that it's closed” (Patient 9, female, age 50 years). |

|

| 2. Cough | 2.1 Cough control | “I don't think I've got the ability anymore to stop my cough” (Patient 12, female, age 75 years). “I cough more than I say I do because I said it, it's part of your life, whether you like it or not, you can't control it, or I can't control it, it just comes” (Patient 7, female, age 72 years). “I mean if I could control the cough, it would be great. I've been using – I've been seeing a speech therapist to try to help me control the cough and she's heard me cough a couple of times and she'll say to me, ‘Oh, you can control that just swallow it down’, [and] it's like no I can't swallow it down, because then I'll start to choke so it's a no-win situation for me” (Patient 4, female, age 62 years). |

|

| 2.1.1 Cough control to prevent a cough from starting | “It just seems that, as the phlegm builds up it just gets to a point where you just have no choice. I mean you're going to cough or you're going to try and clear it or get it out” (Patient 3, male, age 53 years). “The less severe cough they all start with a trickle – with a tickle rather – and or, as I said, sort of that mind over matter where I'm going into a theatre I think, ‘I'm gonna cough here now’, but typically it's a tickle that begins. The less severe cough happens when I very quickly produce a phlegm and that's it. The less severe cough can be controlled with a lozenge” (Patient 6, male, age 70 years). “Sometimes when I can feel it coming I try to hold my breath to stop it, which I shouldn't do because it just makes it worse. But like the other two, there's no ability to stop it or control it, it's like it takes over, it just takes over your body and until that cough is out… there's no way to stop it or control it” (Patient 10, female, age 57 years). “At the beginning, I know I could take cough drop, and it would make it less severe or I could drink water and it my control a bit, but I mean those possibilities are long gone way in the past, nothing controls it” (Patient 14, female, age 66 years). “And I when to get into that stage, I am the one who is initiating the severe cough, I'm trying to cough up phlegm and nothing is coming up, although I can feel it there. […] So I am the one who instigates that severe cough as opposed to it just happening on its own” (Patient 6, male, age 70 years). |

||

| 2.1.2 Cough control once a cough has started | “Yeah, I think if you can control it, it would be a less severe cough. I have no control once I start” (Patient 11, female, age 60 years). “I don't have an ability to control it once it starts coughing that's it until it stops… and yeah so there's no ability to control it, and it does get more severe as I'm coughing” (Patient 9, female, 50 years). “All you can do [is] cough… you can't control it [during an episode]” (Patient 1, male, age 44 years). |

||

| 2.2 Cough frequency | 2.2.1 Overall frequency, defined as frequency of single coughs and fits/bouts | “I also judge severity by frequency, so some days I may only have three to four episodes, which I would classify as a good day. Other days I may have 12 to 15 episodes, which obviously, is not so good of a day. So I kind of throw that in there with severity – how many episodes I have” (Patient 1, male, age 44 years). “I would say in my case that it's less about violent frequencies and more of a constant throughout the day. I must cough at least 200 plus times a day. And I don't seem to go through a period of not coughing. It's become just a part [of me]” (Patient 3, male, age 53 years). “I'll have a severe attack at least once a day, sometimes two and three times a day with my short coughs, the easy coughs happen, some days 10 times some days maybe 50 times, I can't seem to pinpoint what makes it cough, what makes it more frequent. I'll have good days when I feel like, “wow I only coughed 10 times today”, but I will still have a good day without having a really severe cough” (Patient 15, female, age 57 years). “Yeah I agree mine's all day long, sometimes it's just little coughs sometimes it's big ones…” (Patient 4, female, age 62 years). “Mine doesn't last a long time, but it happens a lot” (Patient 11, female, age 60 years). |

|

| 2.2.2 Daytime frequency | “So for me I don't think I cough much at night at all. But crazy during the day” (Patient 9, female, age 50 years). “For me personally [my cough frequency] during the day is worse because that's when I'll have more triggers. If I use my voice too much that can be a trigger. Could even be a certain way the wind blows on my face or by my ear that will trigger a sort of spasm or episode” (Patient 1, male, 44 years). “During the day there's more frequency” (Patient 12, female, 75 years). “[My cough] is very rare at night, mostly during the day – actually always during the day” (Patient 6, male, age 70 years). |

||

| 2.2.3 Night-time frequency | “So basically when I'm sleeping I don't have a lot of cough” (Patient 9, female, age 50 years). “I am very lucky when I go to sleep, I do not cough. I feel like I should stay in bed” (Patient 14, female, age 66 years). “Yes, I find at night, like most nights, my nights are just as bad as my days, just out of the blue I'll start coughing. Doesn't matter if I'm on my back, my side, sometimes I have to sit up and just cough it out, or I leave the room and go sit somewhere just because I can't catch my breath” (Patient 10, female, age 57 years). “And I do cough throughout the night. I have a bedtime medication that I take with a sip of water before I go to bed, but as soon as I put my head down, I cough for the next 5–10 minutes, and then I fall asleep, but then I do wake myself up periodically throughout the night with a dry cough” (Patient 13, female, age 62 years). |

||

| 2.2.4 Morning frequency | “When I do get up in the morning, as soon as I stand up and as soon as I wake up that's when It all starts happening” (Patient 9, female, 50 years). “My cough is worse in the morning” (Patient 2, male, age 51 years). |

||

| 2.2.5 Fit/bout frequency | “I’ll have a severe attack at least once a day, sometimes, two and three times a day” (Patient 15, female, age 57 years). “I would go a month because I think I have one every month. So somebody would be able to relate, I've had seven severe [bouts] in that month period. But like for me it'd be at least once a month, but it seems like everybody else has them more regularly than what I've got right now” (Patient 16, male, age 48 years). “And it's a lot more than what I'm hearing from 6, where he said he could have 2 [severe bouts], like I could have 20” (Patient 9, female, age 50 years). “I have it mostly everyday, some days I may have 1 or maximum 2 of what I would call the severe cough” (Patient 6, male, age 70 years). |

||

| 2.3 Fit/bout duration | 2.3.1 Fit/bout duration | “I definitely have spasms and they can go on for 15–20 minutes” (Patient 7, female, age 72 years). “But when I cough it can go up to two to three seconds, and I cough very hard” (Patient 8, female, age 79 years). “Yeah, the duration is probably anywhere from one to three minutes … it's pretty violent, it's more like – almost like a seizure type event” (Patient 1, male, age 44 years). “I cough like probably 30 times a day and it lasts for 15–20 minutes” (Patient 12, female, age 75 years). “I can have coughs that […] it's just like it could be a couple of seconds, and it could be several minutes” (Patient 9, female, age 50 years). “Many times, my cough gets so bad that I will go for 5–10 minutes” (Patient 15, female, age 57 years). |

|

| 2.4 Intensity | 2.4.1 Physical effort to cough | “… It's nonstop and very deep where you literally hold your chest in your stomach when you cough and it can go on all night long for hours and hours so” (Patient 7, female, age 72 years). “It could be very cloudy in the morning, like the phlegm that comes out of your system, and it's to the point where I have to go to the counter or the sink and I'm almost holding on to the counter because it's so hard on your body… so that's what's happening during” (Patient 9, female, age 50 years). |

|

| 2.4.2 Difficulty expectorating | “The funny thing is as much as I'm trying to clear something at the back, I would say, if this makes sense, it's more of a dry cough that is very, very difficult to clear anything” (Patient 3, male, age 53 years). “A more severe cough is one that which I think is brought on by…that I just can't get the phlegm to come up. […] Like when the cough comes on and I have to cough… and until I get that phlegm up, I will continue to cough. It's just sometimes, the phlegm comes up very easily, very quickly. Other times I'll have to really start to expel it and pressure it” (Patient 6, male, age 70 years). “During the cough, I have to cough and cough and cough and usually there's phlegm that I have to expel in some way. And I basically won't stop coughing until I get rid of it” (Patient 14, female, age 66 years). “During the day it's more of just a cough and it doesn't stop until my throats clear or something I don't know” (Patient 11, female, age 60 years). |

||

| 2.5 Quality | 2.5.1 Harshness of cough | “[My cough is] harsh” (Patient 7, female, age 72 years). | |

| 2.5.2 Deepness of cough | “I cough from my feet. So it's deep and it's loud” (Patient 7, female, age 72 years). “Maybe deep, […] it comes from your feet… it can definitely be deep when it's severe” (Patient 1, male, age 44 years). “The cough comes from my gut, it comes from way down, and then sometimes it comes from my chest” (Patient 12, female, age 75 years). “For me it may be a deeper cough like we're having a conversation just like this [inaudible]… there is just a mild cough right? Just in mid conversation, you can have a mild cough, but when we're getting into the severe coughs as we're referring to them as, I find it's a lot deeper cough there's a lot more…I don't want to say thought put into it, but there's a lot more pressure like there's a lot… it's a lot deeper so like a very it's a deep cough I guess” (Patient 16, male, age 48 years). |

||

| 2.5.3 Hacking due to cough | “Yeah mine, it's a hacking. I just got a cough…really force it up” (Patient 6, male, age 70 years). “So somebody tells a good joke I started laughing and then I end up into a hack attack, (is what I refer to it as) where it's multiple coughs and usually I feel like a pressure in the top of my head, almost like my head's going to explode when I have those hack attacks” (Patient 16, male, age 48 years). |

||

| 2.5.4 Hardness of cough | “When cough it can go up to two to three seconds and I cough very hard” (Patient 8, female, age 79 years). “I consider a severe with me, is when I cough so hard, I actually throw up” (Patient 11, female, age 60 years). |

||

| 2.5.5 Barking due to cough | “Oh, I think I sound like a walrus - like a bark. […] A loud bark” (Patient 12, female, age 75 years). | ||

| 2.5.6 Strong cough | “I think you have to hear it to describe it. It's just very strong” (Patient 9, female, age 50 years). “I have to make a point [and say], “okay breathe, take a break and breathe” because sometimes you're exhaling so much and it's such a strong and violent exhale that I have trouble getting air to breathe in” (Patient 15, female, age 57 years). |

||

| 2.5.7 Violent cough | “It can be very violent and it doesn't last very long these spasms” (Patient 1, male, age 44 years). “It's the violence of the cough” (Patient 4, female, age 62 years). “It's such a strong and violent exhale” (Patient 15, female, age 57 years). |

||

| 2.6 Associated features/sequelae | Experiences while coughing that are associated with intensity | ||

| 2.6.1 Dizziness due to cough | “Afterwards, I sometimes get dizziness like severe dizziness” (Patient 1, male, age 44 years). “Occasionally, I have had some coughing fits that have left me dizzy whether it's my blood pressure changing or what have you, but the dizziness definitely does play a part in it at certain points” (Patient 3, male, age 53 years). “And it does leave you with some dizziness” (Patient 7, female, age 72 years). “I'm coughing my brains out, let's put it that way. My head is spinning after” (Patient 12, female, age 75 years). “When I finish it one of my bad sessions, I feel extremely exhausted, lightheaded” (Patient 15, female, age 57 years). |

||

| 2.6.2 Syncope due to cough | “At times it'll get bad enough, where I blackout, or I feel like I'm going to blackout” (Patient 4, female, age 62 years). “You're coughing hard enough that you're passing out” (Patient 16, male, age 48 years). “I start coughing. I get to the point where I'm turning red, feel like I'm going to pass out” (Patient 15, female, age 57 years). “You're just coughing and coughing and coughing and you get all heated up, lightheaded, feel like you want to pass out because the severity of the cough has taken so much out of you” (Patient 13, female, age 62 years). |

||

| 2.6.3 Wheeze due to cough | “I'd say the sound is almost like you're wheezing” (Patient 9, female, age 50 years). “Almost feels like I would go into a wheeze and sometimes I have, but not all the time” (Patient 11, female, age 60 years). |

||

| 2.6.4 Dyspnoea/shortness of breath due to cough | “My husband was sitting staring at me waiting for me to – I felt like he was waiting for me to die, and it was like, ‘is she ever going to get her breath back?’, and I finally got it calmed down enough to get my breath back and then I'm sitting and I'm deep breathing” (Patient 4, female, age 62 years). “I find that I can lose my air and what I mean by that is I've got to breathe in to speak out after a bad session” (Patient 7, female, age 72 years). “And after, I have a lot of spells […] I also lose my breath, so it takes a bit to catch my breath again after coughing” (Patient 10, female, age 57 years). “At my cough I get coughing really, really bad and shortness of breath. Sometimes, it can't breathe properly. But it calms down on its own, after a while” (Patient 2, male, age 51 years). “So it gets to the point where you're coughing, so much, so severe and so badly that you almost feel like you're losing your breath because you're gasping” (Patient 9, female, age 50 years). “I have to make a point [and say], ‘okay breathe, take a break and breathe’ because sometimes you're exhaling so much and it's such a strong and violent exhale that I have trouble getting air to breathe in” (Patient 15, female, age 57 years). |

||

| 2.6.5 Incontinence due to cough | “[Incontinence] can be bad” (Patient 4, female, age 62 years). “I literally have to go to the bathroom or I might go in my pants type thing. And it's not pee, it's the opposite - it's diarrhoea. It's not always, it's just when I have those really severe ones and if it's morning” (Patient 9, female, age 50 years). “Unfortunately, I'm incontinent when it happens, sometimes. [That's when] it's really terrible” (Patient 12, female, age 75 years). |

||

| 2.6.6 Pressure in head due to cough | “I end up into a hack attack (is what I refer to it as), where it's multiple coughs and usually I feel like a pressure in the top of my head, almost like my head's going to explode when I have those hack attacks” (Patient 16, male, age 48 years). “I had the head pressure, everything like you said, I felt like I was going to pass out” (Patient 15, female, age 57 years). “I'm all heated up and my head feels it's going to explode” (Patient 13, female, age 62 years). “It puts a lot of pressure on your face, you know from the coughing and everything” (Patient 14, female, age 66 years). |

||

| 2.6.7 Tightness of throat due to cough | “And then I feel the pain in my temples but also that's true the neck pain I feel it afterwards, like that tightness just like I have tight scarf or something around my neck” (Patient 15, female, age 57 years). | ||

| 2.6.8 Tightness of chest due to cough | “I cough from my feet. […] Your muscles all tighten up in your chest” (Patient 7, female, age 72 years). “For myself, for the severe coughs, again it's the pressure. It's very… I can relate to the struggle to breathing… it's just a lot of pressure. A lot of pressure in the head and the chest. But the mild ones, nothing to it really it's just. Just a mild, like the common cough. No pressure” (Patient 16, male, age 48 years). |

||

| Immediate experiences after coughing that are associated with intensity depending on susceptibility | |||

| 2.6.9 General pain due to cough | “I cough from my feet. So it's deep and it's loud and it hurts, your muscles all tighten up in your chest” (Patient 7, female, age 72 years). “I have severe pains, like in my chest and in my back, in my abdomen. I had a muscle or something popped out just on my chest, like the size of the bb finger overnight from the coughing. I'm just really sore and tender because I cough so much. Like my back, my ribs, my abdomen and things like that” (Patient 15, female, age 57 years). |

||

| 2.6.10 Rib pain or fracture due to cough | “I think coughing so badly that you feel it in your ribs almost and in back pain” (Patient 9, female, age 50 years). “And it does hurt my ribs and my stomach, like when I caught so bad, and they just come out of the blue” (Patient 10, female, age 57 years). “I have actually coughed so bad that I have popped the rib in my back” (Patient 13, female, age 62 years). “It puts a lot of pressure on your face, you know from the coughing and everything, and I do pop ribs frequently” (Patient 14, female, age 66 years). |

||

| 2.6.11 Chest pain due to cough | “My cough is worse in the mornings, sometimes I get chest pains, but they go away after a while when I try to settle it down” (Patient 2, male, age 51 years). | ||

| 2.6.12 Abdominal pain due to cough | “[After I cough] […] my stomach is sore…” (Patient 12, female, age 75 years). “And it does hurt my ribs and my stomach, like when I caught so bad, and they just come out of the blue” (Patient 10, female, age 57 years). |

||

| 2.6.13 Back pain due to cough | “And during [the cough] sometimes it can be very severe where it feels almost like you're coughing so badly that you feel it in your back” (Patient 9, female, age 50 years). | ||

| 2.6.14 Neck pain due to cough | “My neck as well, I can feel pain in my neck when I have the severe cough as well” (Patient 11, female, age 60 years). “It's almost like someone is squeezing your neck from both sides, like that hard pressure and pain” (Patient 15, female, age 57 years). |

||

| 2.6.15 Aches due to cough | “I would remember yesterday, too - I had a session, where I coughed all night, and I was really sore” (Patient 7, female, age 72 years). “I find it very agonising – that's the word I was looking for, agonising. It just seems to be like every part of your chest and all around there ache, like really ache, when it's really bad” (Patient 5, female, age 70 years). |

||

| 2.6.16 Headache due to cough | “[After I cough] my head aches” (Patient 5, female, age 70 years). “Sometimes I'll get a headache after my cough” (Patient 16, male, age 48 years). “I find that when I have the cough attack the actual headache is in my temples, like it actually hurts to touch my temple sometime” (Patient 15, female, age 57 years). |

||

| 2.6.17 Exhaustion due to cough effort | “It (my cough) is very draining” (Patient 13, female, age 62 years). “It can be physically exhausting” (Patient 1, male, age 44 years). “Just from coughing so much that it takes so much energy out of you” (Patient 9, female, age 50 years). “When I finish the cough, to be honest with you, I don't feel better I'm just really exhausted” (Patient 12, female, age 75 years). “I feel the same way, I'm exhausted and I'd like to lay down for a bit” (Patient 10, female, age 57 years). “And it sometimes can make me feel very worn out” (Patient 14, female, age 66 years). “When I finish it one of my bad sessions, I feel extremely exhausted” (Patient 15, female, age 57 years). |

||

| 2.6.18 Voice loss due to cough | “One of the after effects as well that I get sometimes [is that] it'll really weaken my voice if I have a couple of really bad episodes, my voice [will be] next to gone for a few hours” (Patient 1, male, age 44 years). “I lost my voice for 3 weeks because of the coughing… [the coughing was] so severe” (Patient 5, female, age 70 years). “Something I want to mention is when I went to ear, nose and throat specialist a year and a half or 2 years ago, because I lost my voice from the coughing” (Patient 14, female, age 66 years). |

||

| 2.6.19 Retching/dry heaving/gagging/choking due to cough | “I get dry heaving sometimes too like its associated with choking, I don't always throw up, but definitely some dry heaving. Sometimes that's even a worse symptom than the coughing itself” (Patient 1, male, age 44 years). “But it's almost like you're almost like – you're not throwing up but it feels like the same thing of throwing up” (Patient 9, female, age 50 years). “Yeah, I almost feel at times [that] when I get the phlegm and I can make it come up that it's a successful cough, as stupid as that sounds, because most of them are just a dry heave” (Patient 4, female, age 62 years). |

||

| 2.6.20 Vomiting due to cough | “[I can] cough like crazy… to the point where I'm almost like vomiting” (Patient 9, female, age 50 years). “I consider a severe with me, is when I cough so hard, I actually throw up” (Patient 11, female, age 60 years). “And after, I have a lot of spells when I cough where I vomit” (Patient 10, female, age 57 years). “A lot of times with a severe cough I have to cough until I expel all this phlegm. If it's after eating I'll throw up food” (Patient 14, female, age 66 years). |

||

| 2.6.21 Nausea due to cough | “It (my cough) can cause nausea sometimes too” (Patient 1, male, age 44 years). “I was going through this same thing where [if I was] nauseated, [bad] stomach, anything you know, and I just never, never, never stopped [coughing]” (Patient 5, female, age 70 years). |

||

| 2.6.22 Expectoration of phlegm, sputum or mucus | “The only time I find relief, believe it or not – if the phlegm is really bad, is if I throw up… it seems to clear everything right out, and I feel relief” (Patient 5, female, age 70 years). “Okay, with my cough like I cough so much where I vomit a lot of mucus” (Patient 10, female, age 57 years). “I consider a severe with me, is when I cough so hard, I actually throw up. Now, sometimes throw up, but sometimes it is literally, sorry I don't mean to be gross, literally a mouth full of phlegm. So that's my most severe” (Patient 11, female, age 60 years). “Sometimes I have a coughing spell and then I burp and then sort of throw up the phlegm. This would possibly happen after drinking, for example, water” (Patient 14, female, age 66 years). |

||

| 2.6.23 Feeling of heart racing due to cough | “It's a constant fight to try to get my breath to bring my heart rate back down” (Patient 4, female, age 62 years). “Afterwards, I sometimes get dizziness like severe dizziness or I could feel my heart rate slow, slow and then speed up after the event is over. So it's like my heart rebounding from slowing down” (Patient 1, male, age 44 years). “But I find every time I have a really strong one, which happens many times a day, it's almost like your heart is racing. So I just put my hand on my heart, I want to make sure that I'm calming it down. So I think it's tough on our internal organs” (Patient 9, female, age 50 years). “And one thing I noticed after a cough, is that it raises my blood pressure” (Patient 14, female, age 66 years). “And my pulse rate, as I'm sure all of yours, goes extremely high. And oxygen level goes low, I have one of those, you know the oxygen levels dropped significantly as well” (Patient 15, female, age 57 years). |

||

| 2.6.24 Feeling of body heating up due to cough | “You're just coughing and coughing and coughing and you get all heated up” (Patient 13, female, age 62 years). “You've got during the cough your body temperature goes up” (Patient 9, female, age 50 years). “Many times, my cough gets so bad […] and then the rest of my body breaks out into a sweat” (Patient 15, male, age 48 years). |

||

| 2.6.25 Umbilical hernia due to cough | “I had a muscle or something popped out just on my chest, like the size of the bb finger overnight from the coughing” (Patient 15, male, age 48 years). | ||

| 2.6.26 Watery eyes due to cough | “You've got during the cough […] your eyes are watering, and that to me is the description of the more severe” (Patient 9, female, age 50 years). “It almost looked like I was crying when I have the bad attacks” (Patient 10, female, age 57 years). “But it was so bad was so bad, I was in tears” (Patient 16, male, age 48 years). |

||

| 2.6.27 Sneezing due to cough | “I experience like coughing low from the gut, coughing loud, sneezing - like I can sneeze up to 20 times. And my cough is usually dry. Actually, I don't usually produce anything. Although this is the sneezing is wet and yeah it's just severe coughing sneezing and coughing and sneezing” (Patient 12, female, age 75 years). “And often at the end of my cough sessions, I will end with the sneezes as the finale” (Patient 15, female, age 57 years). |

||

| 2.6.28 Numbness in extremities due to cough | “And I sometimes get some numbness in my extremities like if I'm having a really bad episode I'll feel numbness in my hands and my feet” (Patient 1, male, age 44 years). “[I get numbness] down my arms, yeah” (Patient 4, female, age 62 years). “[I get like] like pins and needles” (Patient 7, female, age 72 years). “Many times, my cough gets so bad that […] I feel my legs going numb and burning” (Patient 15, female, age 57 years). |

||

| 2.6.29 Redness in eyes and face due to cough | “[After I cough] my head aches and I think like 9 said, my eyes are beet red” (Patient 12, female, age 75 years). “And then afterwards as I've mentioned about the eyes [getting red and tearing up] and that sort of thing” (Patient 9, female, age 50 years). “During a severe cough my face may become red” (Patient 6, male, age 70 years). “Many times, my cough gets so bad that […] I'm turning the red during my cough sessions” (Patient 15, male, age 48 years). |

||

Urge-to-cough sensations

Patients described sensations, including “tickle”, “chest pressure”, “chest tightness”, “something in the back of the throat” and “hoarseness”, as antecedents to coughing. These sensations could vary in terms of intensity: “Most of the severe ones start with that karate chop effect in my throat. […] Another time, I will feel pressure in my chest… like someone's pushing with their hand down on my chest” (Patient 15). The frequency with which patients experienced these sensations ranged considerably, some reporting a constant sensation and others reporting that it occurs less consistently or not at all:

I'm constantly feeling as though I want to clear the back of my throat.

(Patient 3)

So there's not always any sensation or sign that it's going to come on. I do get sometimes that dry tickle [but] it's not consistent.

(Patient 1)

When asked to compare the severity of their urge-to-cough sensations in relation to their cough, patients reported different experiences:

When I said my urge-to-cough is severe, it's just as severe as the cough… one is not worse than the other.

(Patient 12)

My urge-to-cough, is it more severe than the cough itself? Not necessarily.

(Patient 6)

Cough control

Patients perceived an ability to suppress the start of their cough as a less severe cough: “At the beginning, I know I could take a cough drop, and it would make it less severe or I could drink water and it may control it a bit, but I mean those possibilities are long gone way in the past” (Patient 14). The lack of control was often attributed to an urge sensation: “It just seems that, as the phlegm builds up it just gets to a point where you just have no choice. I mean you're going to cough” (Patient 3). Patients also described cough severity in terms of control once a cough had started: “There's no ability to stop it or control it; it's like it takes over, it just takes over your body and until that cough is out” (Patient 10). Some patients shared that, once started, their ability to bring a cough under control was dependent upon bringing up phlegm.

Cough frequency and fit/bout duration

Patients assessed cough severity in terms of the number of coughs (single or episodes) that they experience in a day: “I judge severity by frequency, so some days I may only have three to four episodes which I would classify as a good day, other days I may have 12 to 15 episodes which obviously, is not so good of a day, so I kind of throw that in there with severity – how many episodes I have” (Patient 1). When describing cough frequency, patients noted that periods of the day (i.e. morning, daytime and/or night-time) may be more or less problematic: “Whether at any time of day or night I'm worse in the morning [and] worse at night, but I do cough all day long” (Patient 11). In addition to variation within a day, patients noted that each day could differ in terms of frequency: “It's not really a daily thing, like the milds would be daily, sometimes like anywhere from 10–20 times in a day I'll have a mild cough. The severe ones, it all depends upon when somebody tells a good joke or somebody makes me laugh is when I get my more severe coughs so it varies right? It could be once a week, some maybe once a month” (Patient 16). When asked to recall cough frequency, some patients struggled to provide an estimate and alluded to preoccupation with their coughing or the fact it had become inured to them: “I don't keep track of how many times I cough a day, I just know I cough constantly” (Patient 10). The number of fits/bouts of coughing seemed easier to recall: “I have it mostly everyday, some days I may have 1 or maximum 2 of what I would call the severe cough” (Patient 6). The duration of coughing fits/bouts was seen as a factor to their overall perception of cough severity: “Many times, my cough gets so bad that I will go for 5–10 min” (Patient 15).

Cough quality and intensity

Patients provided descriptions about the sensory experience of coughing, including “hacking”, “harsh”, “strong”, “deep” and “barking”. The study team classified these terms separately from intensity, which patients conveyed in terms of the physical effort required to cough and the difficulty expectorating:

It can get so severe that I literally have to go to the sink just to hold on just to keep my body.

(Patient 9)

It's just sometimes, the phlegm comes up very easily, very quickly. Other times I'll have to really start to expel it and pressure it.

(Patient 6)

Associated features/sequelae

Patients described symptoms during or immediately after an episode of coughing, including headache and pain around their chest, ribs, abdomen or back: “It just seems to be like every part of your chest and all around there ache, like really ache, when it's really bad” (Patient 5). Patients described feeling breathless, dizzy, wheezy and/or on the verge of fainting after a fit of coughing: “At times it'll get bad enough, where I blackout, or I feel like I'm going to blackout, like I can't get my breath, I'm choking constantly” (Patient 4). Coughing drove some patients to vomit or retch, and many felt exhausted: “You just feel very weak, like you just feel sick and helpless. It takes a lot out of you, a lot of energy” (Patient 15). Female patients described stress incontinence following a severe cough. Less common symptoms included hernia, rib fracture, voice loss, hoarseness, chest and head pressure, throat and chest tightness, and feeling overly heated (figure 1, table 2).

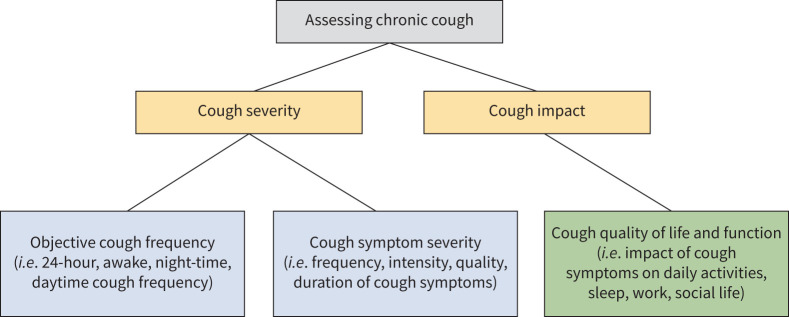

Conceptual difference between cough symptom severity and impact

Although cough symptom severity is related to cough impact on QoL, patients reported differences in the extent to which the same symptom could be viewed as bothersome: “I feel like my cough is very minimal, because I do not have these violent coughs. I do not choke, my heart rate is always normal and my cough, as I said, I do not get violent coughs. But still it's bothering me a lot, especially during the night” (Patient 8). The study team therefore classified impact on QoL as a separate concept from symptom severity.

Expert consensus

An open-ended survey to members of the expert panel identified 32 potential items/domains considered relevant to cough symptom severity (table 3). During the consensus meeting, experts agreed that severity should be conceptualised as an overarching term encompassing domains of frequency, intensity, duration, quality and associated features/sequelae. Experts also agreed that urge-to-cough is an important symptom to capture in a cough severity instrument. A small minority viewed the impact of cough symptoms on QoL (i.e. daily activities, ability to speak, social life) as a necessary aspect of symptom severity. Experts raised cough hypersensitivity as a potentially missing concept from the framework. Thus, the steering group added “triggers” as an additional subdomain (figure 1).

TABLE 3.

Open-ended responses among 11 experts regarding items/domains to assess of cough symptom severity

| Items/domains | Number of endorsements |

| Global score of cough severity (0–10) | 1 |

| Urge-to-cough | 2 |

| Allotussia/hypersensitivity | 3 |

| Control/suppressibility | 1 |

| Intensity | 6 |

| Physical discomfort | 1 |

| Pain (chest/abdominal) | 3 |

| Headache | 1 |

| Dizziness | 1 |

| Rib fractures | 1 |

| Hernia | 1 |

| Sore throat | 1 |

| Throat tightness | 1 |

| Dyspnoea | 1 |

| Syncope | 2 |

| Urinary incontinence | 3 |

| Retching | 1 |

| Vomiting | 1 |

| Timing | 2 |

| Frequency | 4 |

| Bout frequency | 1 |

| Duration of bouts | 1 |

| Quality | 2 |

| Distress | 2 |

| Impact on depression or anxiety | 2 |

| Impact on daily activities | 6 |

| Impact on sleep | 3 |

| Impact on ability to speak | 1 |

| Impact on social life | 1 |

| Worry that cough represents a serious illness | 1 |

| Perceived impact on family/co-workers | 2 |

| Number of previous investigations for cough | 1 |

Discussion

We report consensus findings from patient focus groups and expert panel discussions regarding items and domains to assess cough symptom severity in patients with RCC/UCC. The study confirms findings from a prior systematic survey and identifies eight additional items/domains. The final conceptual framework includes 51 items arranged under two broad domains of urge-to-cough (subdomains: frequency and intensity) and cough symptom (subdomains: triggers, control, frequency, fit/bout duration, intensity, quality and associated features/sequelae) (figure 1).

Although experts and patients agreed on the appropriateness of items and domains, a small minority of experts viewed the impact of cough on QoL as a necessary component of symptom severity. Evaluation of symptom severity and impact on QoL provides a complete assessment of cough (figure 2). An instrument addressing symptom severity alone may, however, be important for several reasons.

FIGURE 2.

Assessing cough in patients with refractory or unexplained chronic cough (RCC/UCC).

First, there is substantial variation in the extent to which patients find the same symptoms bothersome. Impact on QoL can be influenced by factors other than cough symptom severity, including comorbid anxiety and depression [21]. As this study focused solely on symptom severity, rather than impact, the domains identified are less likely to be influenced by distal factors.

Second, the experience of chronic cough over years can have a cumulative impact on QoL that may not be responsive to change in symptom severity over short periods of treatment. As current patient-reported outcome measures primarily assess cough impact on QoL and demonstrate modest association with objective measures [22–24], cough symptom severity requires directed and targeted measurement that responds well to treatment effects.

Third, neuromodulatory agents can improve cough QoL with little to no effect on underlying objective cough frequency [8, 9]. A subjective instrument assessing change in cough severity, rather than impact, is therefore needed to establish whether treatment is targeting the intended symptom. For this reason, regulatory agencies often require that primary end-points measure on-target effects to establish effectiveness for claimed indications.

Fourth, although cough frequency monitors are ideal to objectively assess cough, their limited feasibility in clinical practice suggests potential utility in developing a symptom severity instrument for better longitudinal assessment. The cough severity VAS, although widely used in clinical practice, has limitations as a single-item instrument, and there is lack of evidence supporting its measurement properties.

Finally, a cough symptom severity instrument that assesses domains of cough and urge-to-cough sensations may identify subgroups of patients who share cough pathophysiology [25]. Although current guidelines recommend treatment with centrally acting neuromodulatory agents and speech therapy, there is currently limited evidence to inform patients who may benefit more from a specific treatment. As new therapies, including peripherally acting P2×3 antagonists [26–31], that target specific pathophysiology are introduced, stratification of patients with chronic cough based on domains of cough symptom severity may be useful for precision medicine.

A qualitative study informed development of the CSD and identified three concepts under cough severity: intensity, frequency and disruption [32]. Although our results are consistent with themes identified in their study, our work differs in that we involved patient partners and experts to optimally define the measurement construct of a cough symptom severity instrument [33–35] and strove for conceptual clarity by excluding items/domains related to cough impact on QoL.

Other strengths of this study include strict inclusion of patients who would qualify for phase 2/3 antitussive clinical trials [28, 29] and triangulation of focus groups with an existing framework, patient partners and clinical experts.

Limitations include recruitment of English-speaking patients from a single tertiary clinic; potential selection bias of experts; potential response bias among focus group patients; and subjectivity in interpretation of themes leading to consensus.

Conclusion

We outline a conceptual framework for measuring cough symptom severity in patients with RCC/UCC. The results support content validity of a patient-reported outcome measure. Future studies should address items and domains that are most important to patients for item reduction of a cough symptom severity questionnaire.

Supplementary material

Please note: supplementary material is not edited by the Editorial Office, and is uploaded as it has been supplied by the author.

Supplementary material 00667-2021.SUPPLEMENT (172.2KB, pdf)

Acknowledgements

We thank our patient partners, Faye Johnston, Robert Newman and Nada Popovic, for providing feedback on our manuscript. We also thank Mariam Awadalla and Hisham Alkassem for their assistance transcribing the focus groups.

Provenance: Submitted article, peer reviewed.

Author contributions: I. Satia is the guarantor of the study. E. Kum, G.H. Guyatt, P.M. O'Byrne and I. Satia formed the steering group and conceived the study. E. Kum, C. Munoz, S. Beaudin and S-A. Li contributed to data collection. R. Abdulqawi, H. Badri, L-P. Boulet, R. Chen, P. Dicpinigaitis, L. Dupont, S.K. Field, C.L. French, P.G. Gibson, R.S. Irwin, P. Marsden, L. McGarvey, J.A. Smith and W-J. Song served as expert panel members. E. Kum, G.H. Guyatt and I. Satia analysed and interpreted the data. E. Kum wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors critically reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Conflicts of interest: E. Kum, G.H. Guyatt, C. Munoz, S. Beaudin, S-A. Li, R. Abdulqawi, H. Badri, L. Dupont and L. McGarvey report no conflicts of interest. L-P. Boulet reports grants from Amgen, AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, Novartis and Sanofi-Regeneron, and personal fees from AstraZeneca, Covis, Novartis, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck and Sanofi-Regeneron, outside the submitted work. R. Chen reports grants and personal fees from AstraZeneca and GlaxoSmithKline, and personal fees from Novartis and Merck, outside the submitted work. P. Dicpinigaitis reports consulting fees from Merck, Bellus, Bayer, Shionogi and Chiesi, outside the submitted work. S.K. Field has served on advisory boards for GSK and Merck, has given sponsored talks for Boehringer Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline and Novartis, and has received research funding from AstraZeneca, CIHR, InsMed and Novartis, outside of the submitted work. C.L. French and R.S. Irwin disclose that they are co-developers and hold the copyright of the CQLQ and have each received less than $700 in fees over the past 3 years for its use in studies. P.G. Gibson reports grants from GlaxoSmithKline, and personal fees from AstraZeneca, Chiesi, GSK, Novartis and Sanofi, outside the submitted work. P. Marsden reports an investigator-initiated grant from Merck Sharpe & Dohme Ltd outside the submitted work. W-J. Song reports grants from MSD and AstraZeneca, consulting fees from MSD and AstraZeneca, and lecture fees from MSD, AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline and Novartis, outside the submitted work. J.A. Smith reports grants from Merck, Ario Pharma, GlaxoSmithKline, NeRRe Pharmaceuticals, Menlo, Bellus and Bayer, and personal fees from Chiesi, Ario Pharma, GlaxoSmithKline, NeRRe Pharmaceuticals, Menlo, Bellus, Bayer, Boehringer Ingleheim, Genentech and Neomed, outside of the submitted work. J.A. Smith is a named inventor on a patent, owned by Manchester University NHS Foundation Trust and licensed to Vitalograph Ltd, describing the detection of cough from sound recordings. The VitaloJAK cough monitoring algorithm has been licensed by Manchester University Foundation Trust (MFT) and the University of Manchester to Vitalograph Ltd and Vitalograph Ireland (Ltd). MFT receives royalties that may be shared with the clinical division in which J.A. Smith works. P.M. O'Byrne reports grants and personal fees from AstraZeneca and Medimmune, personal fees from GlaxoSmithKline and Chiesi, and grants from Novartis and Biohaven, outside the submitted work. I. Satia reports an ERS Respire 3 Marie Curie Fellowship, grants and personal fees from Merck Canada, and personal fees from GlaxoSmithKline and AstraZeneca, outside the submitted work.

References

- 1.Song WJ, Chang YS, Faruqi S, et al. The global epidemiology of chronic cough in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Respir J 2015; 45: 1479–1481. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00218714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Irwin RS, Baumann MH, Bolser DC, et al. Diagnosis and management of cough executive summary: ACCP evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest 2006; 129: Suppl. 1, 1s–23s. doi: 10.1378/chest.129.1_suppl.1S [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morice AH, Birring SS, Smith JA, et al. Characterization of patients with refractory or unexplained chronic cough participating in a Phase 2 clinical trial of the P2X3-receptor antagonist Gefapixant. Lung 2021; 199: 121–129. doi: 10.1007/s00408-021-00437-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morice AH, Millqvist E, Belvisi MG, et al. Expert opinion on the cough hypersensitivity syndrome in respiratory medicine. Eur Respir J 2014; 44: 1132–1148. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00218613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Birring SS, Prudon B, Carr AJ, et al. Development of a symptom specific health status measure for patients with chronic cough: Leicester Cough Questionnaire (LCQ). Thorax 2003; 58: 339–343. doi: 10.1136/thorax.58.4.339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.French CT, Irwin RS, Fletcher KE, et al. Evaluation of a cough-specific quality-of-life questionnaire. Chest 2002; 121: 1123–1131. doi: 10.1378/chest.121.4.1123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baiardini I, Braido F, Fassio O, et al. A new tool to assess and monitor the burden of chronic cough on quality of life: Chronic Cough Impact Questionnaire. Allergy 2005; 60: 482–488. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2005.00743.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vertigan AE, Kapela SL, Ryan NM, et al. Pregabalin and speech pathology combination therapy for refractory chronic cough: a randomized controlled trial. Chest 2016; 149: 639–648. doi: 10.1378/chest.15-1271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith J, Ballantyne E, Kerr M, et al. Late Breaking Abstract - The neurokinin-1 receptor antagonist orvepitant improves chronic cough symptoms: results from a Phase 2b trial. Eur Respir J 2019; 54: Suppl. 63, PA600. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith JA, Holt K, Dockry R, et al. Performance of a digital signal processing algorithm for the accurate quantification of cough frequency. Eur Respir J 2021; 58: 2004271. doi: 10.1183/13993003.04271-2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vertigan AE, Kapela SL, Birring SS, et al. Feasibility and clinical utility of ambulatory cough monitoring in an outpatient clinical setting: a real-world retrospective evaluation. ERJ Open Res 2021; 7: 00319-02021. doi: 10.1183/23120541.00319-2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boulet LP, Coeytaux RR, McCrory DC, et al. Tools for assessing outcomes in studies of chronic cough: CHEST guideline and expert panel report. Chest 2015; 147: 804–814. doi: 10.1378/chest.14-2506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vernon M, Kline Leidy N, Nacson A, et al. Measuring cough severity: development and pilot testing of a new seven-item cough severity patient-reported outcome measure. Ther Adv Respir Dis 2010; 4: 199–208. doi: 10.1177/1753465810372526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Streiner DL, Norman GR, Cairney J. Health Measurement Scales: A Practical Guide to Their Development and Use. New York, Oxford University Press, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martin Nguyen A, Bacci E, Dicpinigaitis P, et al. Quantitative measurement properties and score interpretation of the Cough Severity Diary in patients with chronic cough. Ther Adv Respir Dis 2020; 14: 1753466620915155. doi: 10.1177/1753466620915155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kum E, Guyatt GH, Devji T, et al. Cough symptom severity in patients with refractory or unexplained chronic cough: a systematic survey and conceptual framework. Eur Respir Rev 2021; 30: 210104. doi: 10.1183/16000617.0104-2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care 2007; 19: 349–357. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Palinkas LA, Horwitz SM, Green CA, et al. Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed method implementation research. Adm Policy Ment Health 2015; 42: 533–544. doi: 10.1007/s10488-013-0528-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guest G, Bunce A, Johnson L. How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods 2006; 18: 59–82. doi: 10.1177/1525822X05279903 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res 2005; 15: 1277–1288. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.French CL, Crawford SL, Bova C, et al. Change in psychological, physiological, and situational factors in adults after treatment of chronic cough. Chest 2017; 152: 547–562. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2017.06.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kelsall A, Decalmer S, Webster D, et al. How to quantify coughing: correlations with quality of life in chronic cough. Eur Respir J 2008; 32: 175–179. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00101307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schmit KM, Coeytaux RR, Goode AP, et al. Evaluating cough assessment tools: a systematic review. Chest 2013; 144: 1819–1826. doi: 10.1378/chest.13-0310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Decalmer SC, Webster D, Kelsall AA, et al. Chronic cough: how do cough reflex sensitivity and subjective assessments correlate with objective cough counts during ambulatory monitoring? Thorax 2007; 62: 329–334. doi: 10.1136/thx.2006.067413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mazzone SB, Chung KF, McGarvey L. The heterogeneity of chronic cough: a case for endotypes of cough hypersensitivity. Lancet Respir Med 2018; 6: 636–646. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(18)30150-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abdulqawi R, Dockry R, Holt K, et al. P2X3 receptor antagonist (AF-219) in refractory chronic cough: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2 study. Lancet 2015; 385: 1198–1205. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61255-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smith JA, Kitt MM, Butera P, et al. Gefapixant in two randomised dose-escalation studies in chronic cough. Eur Respir J 2020; 55: 1901615. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01615-2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith JA, Kitt MM, Morice AH, et al. Gefapixant, a P2X3 receptor antagonist, for the treatment of refractory or unexplained chronic cough: a randomised, double-blind, controlled, parallel-group, phase 2b trial. Lancet Respir Med 2020; 8: 775–785. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(19)30471-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morice A, Smith JA, McGarvey L, et al. Eliapixant (BAY 1817080), a P2X3 receptor antagonist, in refractory chronic cough: a randomised, placebo-controlled, crossover phase 2a study. Eur Respir J 2021: 58: 2004240. doi: 10.1183/13993003.04240-2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Garceau D, Chauret NBLU. A selective P2X3 antagonist with potent anti-tussive effect and no taste alteration. Pulm Pharmacol Ther 5937; 2019: 56–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Satia I, Wahab M, Kum E, et al. Chronic cough: investigations, management, current and future treatments. Can J Respir Crit Care Sleep Med 2021; 5: 404–416. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vernon M, Leidy NK, Nacson A, et al. Measuring cough severity: perspectives from the literature and from patients with chronic cough. Cough 2009; 5: 5. doi: 10.1186/1745-9974-5-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guyatt GH, Bombardier C, Tugwell PX. Measuring disease-specific quality of life in clinical trials. CMAJ 1986; 134: 889–895. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Guyatt GH, Feeny DH, Patrick DL. Measuring health-related quality of life. Ann Intern Med 1993; 118: 622–629. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-118-8-199304150-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kirshner B, Guyatt G. A methodological framework for assessing health indices. J Chronic Dis 1985; 38: 27–36. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(85)90005-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Please note: supplementary material is not edited by the Editorial Office, and is uploaded as it has been supplied by the author.

Supplementary material 00667-2021.SUPPLEMENT (172.2KB, pdf)