Abstract

Introduction

About half of older adults with impaired cognition who are discharged home from the emergency department (ED) return for further care within 30 days. We tested the effect of an adapted Care Transitions Intervention (CTI) at reducing ED revisits in this vulnerable population.

Methods

We conducted a pre‐planned subgroup analysis of community‐dwelling, cognitively impaired older (age ≥60 years) participants from a randomized controlled trial testing the effectiveness of the CTI adapted for ED‐to‐home transitions. The parent study recruited ED patients from three university‐affiliated hospitals from 2016 to 2019. Subjects eligible for this sub‐analysis had to: (1) have a primary care provider within these health systems; (2) be discharged to a community residence; (3) not receive care management or hospice services; and (4) be cognitively impaired in the ED, as determined by a score >10 on the Blessed Orientation Memory Concentration Test. The primary outcome, ED revisits within 30 days of discharge, was abstracted from medical records and evaluated using logistic regression.

Results

Of our sub‐sample (N = 81, 36 control, 45 treatment), 57% were female and the mean age was 78 years. Multivariate analysis, adjusted for the presence of moderate to severe depression and inadequate health literacy, found that the CTI significantly reduced the odds of a repeat ED visit within 30 days (odds ratio [OR] 0.25, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.07 to 0.90) but not 14 days (OR 1.01, 95% CI 0.26 to 3.93). Multivariate analysis of outpatient follow‐up found no significant effects.

Discussion

Community‐dwelling older adults with cognitive impairment receiving the CTI following ED discharge experienced fewer ED revisits within 30 days compared to usual care. Further studies must confirm and expand upon this finding, identifying features with greatest benefit to patients and caregivers.

Keywords: care transitions, care transitions intervention, cognitive impairment, community paramedicine, dementia, emergency department, emergency

1. BACKGROUND

Emergency departments (EDs) are a large and growing source of acute, unscheduled care in the United States. 1 In 2017, older adults (age ≥65 years) in the United States accessed the ED for care 29.2 million times, with 19.7 million visits (67.5%) resulting in the patient being discharged. 2 Although these patients might seem to be at low risk for poor outcomes, as they lack an illness of sufficient severity to warrant hospital admission, studies have shown that ≈20% to 25% revisit the ED for further care in the 30 days after discharge. They are also at higher risk for other adverse events, including hospitalization and death. 3 , 4 , 5

ED patients with impaired cognition are particularly vulnerable to adverse events following ED discharge. 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 Studies have found that patients with Alzheimer's disease and related dementias (ADRD) who are discharged home from the ED are significantly more likely than patients without ADRD to revisit the ED within 30 days. 8 , 9 The cause of these increased revisit rates is unclear. We know that individuals with impaired cognition find ED visits challenging. The bright lights, noise, and interruptions commonplace in EDs are overwhelming and may increase agitation. Cognitive impairment is often not identified by ED staff, leading to poor recognition of patients’ limited ability to communicate their needs, retain information provided, or ask critical questions. 9 , 10 Thus ED providers are unable to modify their approach to these patients to maximize the quality of care delivered and promote positive outcomes. 9 Unsurprisingly, patients with impaired cognition demonstrate poor comprehension of ED discharge instructions containing critical information about acute illness management, when and how to obtain follow‐up outpatient care, medication changes, and new or worsening “red flag” symptoms that would require medical attention. 11 , 12 , 13

The disproportionately high rate of ED revisits among ED patients with impaired cognition is potentially avoidable. 14 The nature of the ED‐to‐home transition, during which patients (and their care partners) assume responsibility for their health care needs has been suggested as a contributing factor for revisits among older adults in general. 15 , 16 Among patients with impaired cognition, the challenges related to this transition are amplified. ED providers are under time pressure to rapidly care for multiple acutely ill patients, making it difficult to spend extensive time communicating complex information with the patient about post‐discharge care, as well as with care partners who may or may not be present.

To our knowledge, no studies have reported the effect of interventions aiming to improve the ED‐to‐home transition specifically for older patients with impaired cognition. In this pre‐planned subgroup analysis of a randomized controlled trial testing the effectiveness of the Care Transitions Intervention (CTI) adapted for use following ED discharge, we evaluate the extent to which the CTI improves ED‐to‐home transitions for cognitively impaired community‐dwelling older adults. 17 , 18 , 19 We hypothesize that the intervention group will have fewer ED revisits in the 30‐days following the initial ED visit. Furthermore, we hypothesize that they will have increased outpatient follow‐up in the 30 days following the initial ED visit, improved medication adherence, and better knowledge of “red flag” reasons to seek immediate care.

2. METHODS

This was a pre‐planned sub‐group analysis of community‐dwelling, cognitively impaired older adults participating in a single‐blind randomized‐controlled trial (clinicaltrials.gov: NCT02520661) testing the effectiveness of an adapted CTI to improve ED‐to‐home transition outcomes. The study protocol details have been published separately. 20

2.1. Setting and participants

We recruited ED patients discharged home from three participating university hospital EDs in Madison, WI and Rochester, NY. The Institutional review boards at the University of Wisconsin and University of Rochester approved the study with written informed consent. Data were collected between January 2016 and July 2019.

To participate in the parent clinical trial, subjects had to be ≥60 years of age, reside in either Dane County, WI or Monroe County, NY, have a primary care provider (PCP) affiliated with either health system, have a working telephone, and be discharged from the ED to a community residence within 24 hours of arrival. They also had to have decisional capacity or a legally authorized representative to provide consent. For this analysis, subjects had to be cognitively impaired, identified by scoring >10 on the Blessed Orientation Memory Concentration Test (BOMC). 21

Subjects were excluded if they did not speak English, because we were only able to provide services in English, and if they were visually or hearing‐impaired after correction because of the need to participate in coaching activities. They were also excluded if they were actively enrolled in hospice, a transitions program, or a care management program because they provide similar services as the CTI, making the intervention duplicative. Participants who presented with a primary psychiatric or behavioral problem were excluded, since the CTI was not meant for patients with these conditions. Finally, they were excluded if their ED visit was assigned an Emergency Severity Index category of 1 because they would be too sick to participate and would likely be admitted to the hospital.

2.2. Intervention description

We provided intervention group subjects with an adapted version of Coleman's CTI (details published previously). 17 , 20 The program was delivered by community paramedic coaches trained by Coleman and his team. The intervention consisted of a single home visit occurring 24 to 72 hours following ED discharge, followed by one to three phone calls from the paramedic coach over the next 4 weeks, scheduled according to the coaches’ determination of need. During home visits, paramedics used coaching strategies (eg, motivational interviewing) to help participants understand the CTI's four main self‐management “pillars”: outpatient follow‐up, medication self‐management, knowledge of red flag symptoms, and use of a personal health record. Red flag symptoms refer to symptomology following a health event that indicate the individual's health is worsening, potentially warranting an ED revisit. 17 , 20 In the CTI context, a personal health record is a document maintained by the patient and/or care partner that centers on the patient's active health issues, including medications, allergies, potential symptoms of the patient's chronic illness(es), discharge activities, and patient questions. 17 The personal health record's purpose is to facilitate productive health conversations between patients and health practitioners. 17 Follow‐up phone calls reinforced this content and the behaviors addressed previously. In line with CTI guidance, coaches did not directly deliver medical or social services to participants. The adaptation was that no transition coaching occurred while the participant was in the ED; all occurred post‐ED. We felt that this change was critical for integration into ED workflows and ensuring operational efficiency and implementation success.

RESEARCH IN CONTEXT

Systematic review: We reviewed the literature prior to initiating this study and found no studies reporting an intervention to improve emergency department (ED)–to‐home care transitions for older patients with impaired cognition.

Interpretation: This sub‐analysis indicates that the Care Transitions Intervention (CTI), delivered by trained community paramedic coaches, may reduce ED revisits for older patients with impaired cognition during the 30 days following discharge home from the ED.

Future directions: The efficacy, effectiveness, and cost‐effectiveness of the CTI for cognitively impaired ED patients need to be evaluated in a dedicated randomized controlled trial. In addition, implementation outcomes need to be evaluated to determine intervention feasibility and acceptability for patients with impaired cognition, caregivers, health system administrators, and policymakers prior to program dissemination.

Highlights

Older patients with cognitive impairment are frequently discharged home from the emergency department (ED)

Post‐ED discharge care transitions influence future health care use and medical outcomes

We tested the Care Transitions Intervention (CTI) in older ED patients who were discharged home

The CTI significantly reduced 30‐day ED revisits for patients with impaired cognition

2.3. Study procedures

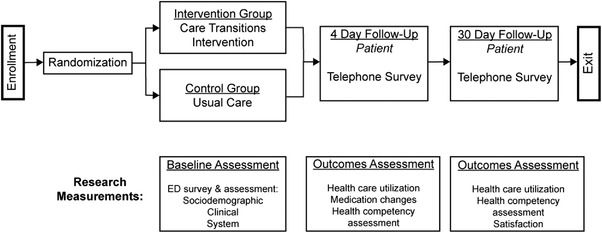

Eligible ED patients were consented and randomly assigned to either the treatment (CTI) or control (usual care) group during their index ED visits (Figure 1). Usual care consisted of physicians or advanced practice providers delivering verbal and written discharge instructions. Nurses then reinforced the instructions. Participants completed verbal surveys and assessments measuring demographic characteristics, cognitive performance, self‐reported health status, and psychosocial measures prior to ED discharge home. Legally authorized representatives could assist in completing survey measures but not cognitive assessments. Researchers conducted phone surveys −4 and 30 days after ED discharge to collect patient‐reported outcomes and to repeat certain assessments as published previously. 21 Trained researchers abstracted data on health care use and comorbid conditions from electronic health records using established best practices. 22

FIGURE 1.

Study activities (Adapted from Mi et al., BMC Geriatrics, 2018)

2.4. Measures

2.4.1. Cognitive performance

We measured participants’ cognitive performance at the time of the index ED visit using the BOMC test. We categorize individuals as having impaired cognition if they scored >10. 21 We also performed a sensitivity analysis to evaluate individuals scoring 5 to 10. 18

2.4.2. Primary outcome—ED visits

The primary outcome measure was whether or not an ED revisit occurred within 30 days of ED discharge. We also assessed ED revisits at 14 days to evaluate potential shorter‐term intervention effects.

2.4.3. Secondary outcomes—self‐management behaviors

We analyzed three CTI self‐management behaviors (outpatient follow‐up, medication self‐management, and knowledge of red flags) that target factors associated with effective care transitions. Outpatient clinician follow‐up included in‐person office visits, telephone calls, and online patient portal messaging. We excluded visits for previously scheduled procedures, imaging, and laboratory sample collection, as well as clinic‐generated messages not receiving a patient response and any contacts made without the patient's involvement. Telemedicine visits were not available to patients, and thus were not included. Binary variables were created to measure whether or not any outpatient follow‐up occurred within 14 and 30 days of ED discharge.

During the 4‐day telephone survey, participants were asked if they made medication changes following the ED visit (including stops, starts, and dose changes), and to provide either generic name, brand name, classification, or purpose of each medication (eg, Keflex, cephalexin, antibiotic, or medication for my infection). We compared patient‐reported medication changes to ED discharge instructions, excluding medications with “as needed” instructions. Post‐discharge medication self‐management was measured as a binary variable indicating whether or not the participant reported making all medication‐related changes. Only patients with medication‐related discharge instructions were included in the analysis.

During the 4‐day phone survey we also asked participants to report red flags provided to them at ED discharge. We defined red flags as specific clinical signs and symptoms (eg, vomiting) for which they were told to either seek additional care from their PCP or return to the ED. General instructions (eg, “any other concerns”) were excluded. To assess this pillar, we created a binary variable measuring participants’ ability to report at least one specific red flag of those listed on their written ED discharge instructions. Only patients with specific red flags listed on their discharge instructions were included in this analysis.

2.4.4. Covariates

We measured specific demographic and health characteristics that we anticipated would be covariates, including depression (Patient Health Questionairre‐9), 19 anxiety (General Anxiety Disorder‐2), 23 general health status (SF‐12), 24 and health literacy. 25 Depression and anxiety were included, because both have been associated with treatment non‐adherence and increased risk of ED revisits. 26 , 27 , 28 Health literacy was assessed because low health literacy has been associated with significantly higher ED revisit rates. 29 , 30 We treated each variable as a binary characteristic using standard thresholds, except for age and number of comorbid conditions consistent with the Charlson Comorbidity Index, 31 which were treated as continuous. Covariate measure generation and data collection details are published elsewhere. 21

2.5. Statistical analysis

We conducted all analyses using the intention‐to‐treat approach. We first tested our primary outcome measure, ED revisit within 30 days, and the shorter 14‐day period. To identify imbalances in randomization between intervention and control groups, we used Pearson chi‐square tests and two‐sample t‐tests to compare differences among the variables. Variables that differed between control and intervention groups at P≤.10 were each entered into separate univariate logistic regression models comparing the association between the intervention group and ED revisit within 30 days and 14 days. Factors that generated ≥10% change in the odds ratio (OR) for the ED revisit were selected to be covariates for the final models. The only covariates to meet this criterion were health literacy and depressive symptoms. For conceptual consistency, multivariate logistic regression analyses for ED revisits within both time periods included the same set of covariates. This approach was taken to develop the most parsimonious models, as the total number of subjects was small after removing participants with missing data, thus limiting the overall number of variables included.

We took the same approach for outpatient clinic follow‐up. For conceptual consistency, multivariate logistic regression analyses for outpatient follow‐up analyses included the same set of covariates. Health literacy, depressive symptoms, and one or more activities of daily living (ADL) deficiencies were the only covariates to meet inclusion criterion. We did not perform multivariate analyses for medication changes or red flags due to the small numbers of eligible participants for these analyses.

We defined P‐values of < .05 to be statistically significant, reporting all regression results as adjusted ORs with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Prior to running regression models, we conducted several diagnostic assessments of our data including multicollinearity and influential outliers. We used R Statistical Software for all analyses.

3. RESULTS

Of the 1756 ED patient participants included in the parent study, we identified 81 participants with impaired cognition at the time of their ED visit (36 control and 45 intervention). Table 1 describes the characteristics of the analysis sample. The only significant difference between the control and intervention groups was the prevalence of moderate or major depression. Fourteen participants in the intervention group (31%) did not complete the coach home visit and therefore did not receive any intervention content (including phone calls). The majority of visits were cancelled either by the participant or their care partner during the pre‐visit confirmation call. Reasons for non‐completion included feeling too ill to participate, conflicting appointments (eg, PCP visits), and not being present at the scheduled time. One participant withdrew from the study, resulting in a total sample size of 80 participants.

TABLE 1.

Population Characteristics a

| Characteristic | Overall (N = 81) | Control group (n = 36) | Intervention group (n = 45) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (M [SD]) | 78.4 (10.1) | 77.6 (9.57) | 79.0 (10.5) |

| Sex = Male (%) | 35 (43.2) | 19 (52.8) | 16 (35.6) |

| Race = Non‐White (%) | 13 (16.0) | 6 (16.7) | 7 (15.6) |

| Ethnicity = Hispanic (%) | 4 (5.0) | 1 (2.9) | 3 (6.7) |

| Education = Some College or Less (%) | 49 (60.5) | 20 (55.6) | 29 (64.4) |

| BOMC Score (M [SD]) | 16.94 (5.70) | 17.47 (6.10) | 16.51 (5.39) |

| Marital Status = Not Married (%) | 40 (49.4) | 15 (41.7) | 25 (55.6) |

| Lives Alone (%) b | 27 (33.8) | 11 (31.4) | 16 (35.6) |

| Number of Charlson Comorbidities (M [SD]) | 3.07 (1.63) | 2.81 (1.60) | 3.29 (1.63) |

| Limited in 1+ ADLs (%) b | 46 (57.5) | 16 (45.7)* | 30 (66.7)* |

| Health Literacy = Inadequate (%) c | 32 (43.8) | 10 (31.2)* | 22 (53.7)* |

| GAD‐2 = Anxiety Disorder (%) c | 16 (21.9) | 4 (12.5) | 12 (29.3) |

| PHQ‐9 = Moderate to Severe (%) d | 10 (13.9) | 1 (3.1)** | 9 (22.5)** |

| SF‐12: Self‐Rated Overall Health Fair‐Poor (%) d | 19 (26.4) | 6 (19.4) | 13 (31.7) |

| Had Any Hospitalization in 30 Days Prior to Index ED Visit (%) | 4 (4.9) | 1 (2.8) | 3 (6.7) |

| ED Visits in 30 Days Prior to Index ED Visit (M [SD]) | 0.05 (0.27) | 0.08 (0.37) | 0.02 (0.15) |

| Characteristic | Overall (N = 81) | Control group (n = 36) | Intervention group (n = 45) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (M [SD]) | 78.4 (10.1) | 77.6 (9.57) | 79.0 (10.5) |

| Sex = Male (%) | 35 (43.2) | 19 (52.8) | 16 (35.6) |

| Race = Non‐White (%) | 13 (16.0) | 6 (16.7) | 7 (15.6) |

| Ethnicity = Hispanic (%) | 4 (5.0) | 1 (2.9) | 3 (6.7) |

| Education = Some College or Less (%) | 49 (60.5) | 20 (55.6) | 29 (64.4) |

| BOMC Score (M [SD]) | 16.94 (5.70) | 17.47 (6.10) | 16.51 (5.39) |

| Marital Status = Not Married (%) | 40 (49.4) | 15 (41.7) | 25 (55.6) |

| Lives Alone (%) b | 27 (33.8) | 11 (31.4) | 16 (35.6) |

| Number of Charlson Comorbidities (M [SD]) | 3.07 (1.63) | 2.81 (1.60) | 3.29 (1.63) |

| Limited in 1+ ADLs (%) b | 46 (57.5) | 16 (45.7)* | 30 (66.7)* |

| Health Literacy = Inadequate (%) c | 32 (43.8) | 10 (31.2)* | 22 (53.7)* |

| GAD‐2 = Anxiety Disorder (%) c | 16 (21.9) | 4 (12.5) | 12 (29.3) |

| PHQ‐9 = Moderate to Severe (%) d | 10 (13.9) | 1 (3.1)** | 9 (22.5)** |

| SF‐12: Self‐Rated Overall Health Fair‐Poor (%) d | 19 (26.4) | 6 (19.4) | 13 (31.7) |

| Had Any Hospitalization in 30 Days Prior to Index ED Visit (%) | 4 (4.9) | 1 (2.8) | 3 (6.7) |

| ED Visits in 30 Days Prior to Index ED Visit (M [SD]) | 0.05 (0.27) | 0.08 (0.37) | 0.02 (0.15) |

*P < .10; **P < .05.

N = 80 due to missing covariate data.

N = 73 due to missing covariate data.

N = 72 due to missing covariate data.

Bivariate comparison of the control and intervention groups demonstrated no significant differences in the primary outcome of ED revisits within 30 days (absolute n(%) in Table 2). Among secondary outcomes, we found no significant differences in ED revisits within 14 days or outpatient follow‐up at 14 or 30 days. Forty‐three of the 80 participants had specified red flags on their ED discharge instructions. Seven (16.3%) of these participants correctly reported at least one specific red flag from their ED discharge instructions, with no significant difference between the control and intervention groups. Specific medication changes were present in 21 participants. In this sub‐sample, 6 participants (28.6%) reported completing all medication changes as directed, with no significant difference in completion between the control and intervention groups.

TABLE 2.

Comparison of Outcomes

| Characteristic | Overall (N = 80) | Control Group (n = 36) | Intervention Group (n = 44) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Any ED Follow‐Up at 14 d (%) | 15 (18.8) | 6 (16.7) | 9 (20.5) |

| Any ED Follow‐Up at 30 d (%) | 22 (27.5) | 13 (36.1) | 9 (20.5) |

| Any Outpatient Follow‐Up 14 d–Yes (%) | 63 (78.8) | 27 (75.0) | 36 (81.8) |

| Any Outpatient Follow‐Up 30 d–Yes (%) | 68 (85.0) | 29 (80.6) | 39 (88.6) |

| Characteristic | Overall (N = 80) | Control Group (n = 36) | Intervention Group (n = 44) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Any ED Follow‐Up at 14 d (%) | 15 (18.8) | 6 (16.7) | 9 (20.5) |

| Any ED Follow‐Up at 30 d (%) | 22 (27.5) | 13 (36.1) | 9 (20.5) |

| Any Outpatient Follow‐Up 14 d–Yes (%) | 63 (78.8) | 27 (75.0) | 36 (81.8) |

| Any Outpatient Follow‐Up 30 d–Yes (%) | 68 (85.0) | 29 (80.6) | 39 (88.6) |

*P < .10; **P < .05.

Multivariate regression analyses for ED revisits, adjusted for the presence of moderate to severe depression and health literacy, showed that intervention participants had 75% decreased odds of an ED revisit within 30 days compared to those in the control group (OR 0.25, 95% CI 0.07 to 0.90), but no significant differences within 14 days (OR 1.01, 95% CI 0.26 to 3.93) (Table 3). Multivariate analyses for outpatient follow‐up, adjusted for the presence of moderate to severe depression, any deficiency in activities of daily living, and inadequate health literacy, found no significant treatment effects (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Multivariate Regression—Effect of Intervention a

| Outcome | Model | Odds ratio | 95% Confidence interval |

|---|---|---|---|

| ED Revisit | ED Revisit within 14 days | 1.0 | 0.26‐3.9 |

| Inadequate health literacy | 0.86 | 0.23‐3.2 | |

| Moderate to severe depression | 4.0* | 0.82‐20 | |

| ED Revisit within 30 days | 0.25** | 0.070‐0.90 | |

| Inadequate health literacy | 1.1 | 0.34‐3.5 | |

| Moderate to severe depression | 6.0** | 1.2‐30 | |

| Outpatient Clinic Follow‐up | Outpatient clinic follow‐up within 14 days | 1.00 | 0.30‐3.3 |

| 1+ ADLs | 0.63 | 0.20‐2.0 | |

| Inadequate health literacy | 1.0 | 0.31‐3.3 | |

| Moderate to severe depression | 1.3 | 0.22‐7.3 | |

| Outpatient clinic follow‐up within 30 days | 1.3 | 0.31‐5.1 | |

| 1+ ADLs | 0.63 | 0.16‐2.5 | |

| Inadequate health literacy | 0.93 | 0.24‐3.9 | |

| Moderate to severe depression | 0.69 | 0.11‐4.3 |

| Outcome | Model | Odds ratio | 95% Confidence interval |

|---|---|---|---|

| ED Revisit | ED Revisit within 14 days | 1.0 | 0.26‐3.9 |

| Inadequate health literacy | 0.86 | 0.23‐3.2 | |

| Moderate to severe depression | 4.0* | 0.82‐20 | |

| ED Revisit within 30 days | 0.25** | 0.070‐0.90 | |

| Inadequate health literacy | 1.1 | 0.34‐3.5 | |

| Moderate to severe depression | 6.0** | 1.2‐30 | |

| Outpatient Clinic Follow‐up | Outpatient clinic follow‐up within 14 days | 1.00 | 0.30‐3.3 |

| 1+ ADLs | 0.63 | 0.20‐2.0 | |

| Inadequate health literacy | 1.0 | 0.31‐3.3 | |

| Moderate to severe depression | 1.3 | 0.22‐7.3 | |

| Outpatient clinic follow‐up within 30 days | 1.3 | 0.31‐5.1 | |

| 1+ ADLs | 0.63 | 0.16‐2.5 | |

| Inadequate health literacy | 0.93 | 0.24‐3.9 | |

| Moderate to severe depression | 0.69 | 0.11‐4.3 |

N = 71 due to missing covariate data. *P < .10; **P < .05.

In our sensitivity analysis examining participants that scored 5 to 10 on the BOMC, 262 subjects were eligible for inclusion, with 140 in the control and 122 in the intervention groups. Again, no significant bivariate differences were seen between control and intervention groups (data not shown), and multivariate regression analyses found no significant effects of the intervention for either ED revisit or outpatient follow‐up at 14 or 30 days (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Sensitivity Analysis BOMC Score 5‐10 Multivariate Regression—Effect of Intervention a

| Outcome | Odds ratio | 95% Confidence interval | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ED Revisit | ED Revisit within 14 days | 0.61 | 0.28‐1.3 |

| Inadequate health literacy | 0.46 | 0.15‐1.4 | |

| Moderate to severe depression | 0.93 | 0.33‐2.6 | |

| ED Revisit within 30 days | 0.89 | 0.46‐1.7 | |

| Inadequate health literacy | 0.63 | 0.26‐1.5 | |

| Moderate to severe depression | 1.5 | 0.65‐3.4 | |

| Outpatient Clinic Follow‐up | Outpatient clinic follow‐up, within 14 days | 1.3 | 0.72‐2.5 |

| 1+ ADLs | 0.66 | 0.35‐1.3 | |

| Inadequate health literacy | 2.1* | 0.87‐5.0 | |

| Moderate to severe depression | 0.97 | 0.42‐2.26 | |

| Outpatient clinic follow‐up, within 30 days | 1.4 | 0.63‐2.9 | |

| 1+ ADLs | 0.57 | 0.26‐1.2 | |

| Inadequate health literacy | 1.7 | 0.61‐4.6 | |

| Moderate to severe depression | 1.2 | 0.43‐3.6 |

| Outcome | Odds ratio | 95% Confidence interval | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ED Revisit | ED Revisit within 14 days | 0.61 | 0.28‐1.3 |

| Inadequate health literacy | 0.46 | 0.15‐1.4 | |

| Moderate to severe depression | 0.93 | 0.33‐2.6 | |

| ED Revisit within 30 days | 0.89 | 0.46‐1.7 | |

| Inadequate health literacy | 0.63 | 0.26‐1.5 | |

| Moderate to severe depression | 1.5 | 0.65‐3.4 | |

| Outpatient Clinic Follow‐up | Outpatient clinic follow‐up, within 14 days | 1.3 | 0.72‐2.5 |

| 1+ ADLs | 0.66 | 0.35‐1.3 | |

| Inadequate health literacy | 2.1* | 0.87‐5.0 | |

| Moderate to severe depression | 0.97 | 0.42‐2.26 | |

| Outpatient clinic follow‐up, within 30 days | 1.4 | 0.63‐2.9 | |

| 1+ ADLs | 0.57 | 0.26‐1.2 | |

| Inadequate health literacy | 1.7 | 0.61‐4.6 | |

| Moderate to severe depression | 1.2 | 0.43‐3.6 |

N = 262. *P < .10; **P < .05.

4. DISCUSSION

In this study, we found through logistic regression analysis that community‐dwelling older adults who had cognitive impairment while in the ED were significantly less likely to revisit the ED for care in the 30 days following discharge home if they received the minimally adapted CTI. Thus the CTI is the first intervention that shows promise of effectiveness at reducing the high frequency at which ED patients with cognitive impairment revisit the ED the month following discharge.

As this is the first study to report the effect of a CTI among patients experiencing cognitive impairment in the ED, we can only compare these results with programs targeting the broader population of older adults discharged home from the ED. 3 One non‐randomized study, which placed a nurse discharge plan coordinator in the ED, reduced the likelihood of return within 14 days. That intervention, however, required an average of 20 minutes of additional time in the ED per patient, something neither feasible nor acceptable due to the rapid throughput required. 32 Other interventions—including telephone follow‐up, 33 screening and referral programs, 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 and comprehensive geriatric assessments 39 —have generally been unsuccessful at significantly reducing ED revisits, and in some cases actually increased ED use. In addition, the only evaluation of a heavily‐modified CTI in older adults, targeted only to patients with multiple chronic illnesses or frequent ED utilization, found no reduction in ED revisits. 40

Of note, the true effect size of the CTI may be greater than what is represented here. First, because we followed the intention‐to‐treat approach, we analyzed all individuals assigned to the intervention group, regardless of whether they received the intervention. In fact, 14 of the 45 individuals in the intervention group (31%) did not complete the home visit and thus did not receive CTI content. Nonetheless, the intervention had a significant effect. By comparison, 15% of cognitively intact intervention group participants did not complete the home visit in the parent study. Real‐world implementation of this program would likely have a less‐restrictive time window (home visit completion within 72 hours), allowing coaches the flexibility to reschedule for a later date, and therefore still deliver CTI content to many of these patients. Second, both health systems in the study participated in accountable care organization (ACO) contracts aiming to deliver coordinated, high‐quality care to a population while sharing financial risk. 41 Participants with dementia in ACOs are known to have reduced rates of preventable ED visits relative to those in other types of health care organizations, potentially because ACOs are incentivized to maximize quality and reduce costs. 42

Our findings are a logical extension of the literature describing the difficulties experienced by cognitively impaired patients during ED discharge. Patients with impaired cognition constitute a high‐risk discharge for ED clinicians. These patients are unlikely to remember the discharge instructions (ie, actions to take, symptoms to watch for, and when/whom to follow‐up), and ED providers must turn to care partners to ensure that discharge instructions are understood. Because impaired cognition is frequently not recognized in the ED, health care providers and staff may not involve care partners in the discharge planning process as much as necessary to ensure optimal care transitions. This issue has become even more problematic with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) pandemic‐related restrictions preventing many care partners from participating in ED visits for patients. As CTI coaches review discharge instructions in more detail, they can address some of these issues with the patient and/or care partner in their home—a more comfortable environment without the stress, overstimulation, and time‐pressures of the ED.

The underlying premise of our study is that by facilitating the self‐management behaviors targeted in the CTI, paramedic coaches would be providing the informational and instrumental support needed for older adults with impaired cognition to overcome barriers (eg, system fragmentation, ineffective communication with providers, and lack of social support), thereby reducing potentially preventable ED visits, 43 We anticipated that the CTI would significantly enhance outpatient follow‐up, as coaching programs such as this have been shown to improve continuity of care, which can also decrease ED visits. 44 Although the intervention and control group differences were not statistically significant, ED patients randomized to the intervention group had a 26% increased odds of obtaining follow‐up. Most likely, the lack of significance results from the small number of subjects in the analysis or the proportion of the intervention group that did not receive the intervention. In addition, the lack of changes in outpatient follow‐up may have resulted from a ceiling effect, as it may not be practical or necessary to enhance outpatient follow‐up. In this study, 84% of participants had outpatient follow‐up within 30 days of discharge (Table 2). Other studies with older adult ED patients, have published 30‐day in‐person follow‐up proportions ranging from 28% to 71%. 42 , 43

Our findings have important implications for research and clinical practice. EDs should consider implementing a process to identify which community‐dwelling patients being discharged home are cognitively impaired and deliver an appropriately tailored care transitions program for those individuals. Interventions such as the adapted CTI need to be implemented in a way that is acceptable and feasible for patients with cognitive impairment and their care partners, increasing completion rates and extending programmatic reach. Additional research is required to determine program effectiveness and cost‐effectiveness for this specific population.

4.1. Limitations

The primary limitation of this study is that it is a sub‐group analysis of an investigation into care transitions for the general population of older adults being discharged home from the ED. Participants were not stratified by cognitive impairment before randomization for the purpose of balancing intervention assignment. Thus, this study is not a clinical trial explicitly designed to evaluate the intervention for people with cognitive impairment while in the ED. Second, this study was performed in two mid‐sized, well‐educated cities and in two health systems with ACO contracts, potentially limiting generalizability to other contexts. Further limiting the generalizability is the low level of racial and ethnic diversity. How this would perform in other settings is unknown; however we believe that it would potentially have stronger impact in settings without the structure and support that comes with accountable care organizations.

4.2. Conclusions

Providing community‐dwelling older ED patients with cognitive impairment the CTI upon discharge results in a significant reduction in the odds of ED revisits in the 30 days following discharge. Additional research must confirm this finding and help better clarify the mechanisms through which this program reduces repeat ED visits. Further work should also explore whether the coach visit must be in person, or whether a telemedicine or telephone‐based intervention would realize the same benefits.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

MNS–Research reported in this publication received support from the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01AG050504 and K24AG054560 and the Clinical and Translational Science Award program, through the NIH National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences award UL1TR002373. Grants have been received from NIH, and payments were made to my institution. Contracts have been received from Omron and Lumos, and payments were made to my institution. In the past 36 months, received consulting fees from the University of Cincinnati, University of Colorado, University at Buffalo, NIH, American Federation for Aging Research, Geriatric ED Collaborative, and Mt. Sinai School of Medicine. In the past 36 months, I received support for attending meetings and/or travel for/to the following: American College of Emergency Physicians, American Federation for Aging Research, American Geriatrics Society, NIH, Society for Academic Emergency Medicine, University at Buffalo, University of Cincinnati, and University of Colorado. In the past 36 months, I participated on a Data Safety Monitoring Board/Advisory Board for the NIH and payments were made to me. In the past 36 months, I held leadership position in the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine Foundation (received no payments) and the Isthmus Project (received no payments).

GCJ—In the past 36 months, my department (Emergency Medicine) has provided me professional development travel grants to attend meetings at which I gave research presentations. This is an internal source of funding. I am on the Board of Trustees of Temple Beth El in Madison, WI. This is an unpaid lay leadership position in a religious non‐profit organization.

CMCJ—Received NIH funding for the conduct of this research. In the past 36 months, received grants from the NIH, CDC, NIOSH, and the Society of Academic Emergency Medicine, with payments made to my institution.

RKG—none.

TVC—Received federal grant funding—Health Resources and Services Administration cooperative agreement paid to my institution—AHRQ funding contract paid to institution in the past 36 months. Served on the Collaborative for Palliative Care (nonprofit board member, unpaid).

ALC—Supported on the NIH R01 grant that was associated with the paper. This support was made to the institution. In the past 36 months, I received seed grant from the University of Wisconsin—Madison Center for Human Genomics and Precision Medicine. Payments were made to my institution. From 2017‐2021, I had an NIMH K01 award, and the grant was made to my institution.

JTC—In the past 36 months, I have served as Trustee, Hobart and William Smith Colleges Board Member, New York Chapter American College of Emergency Physicians.

ML—none.

AJHK—I received NIH funding for the present manuscript and received grants from the NIH and VA in the past 36 months (all payments to my institution). In the past 36 months, I received payments from various academic institutions for visiting professorships. Received support to travel to the Alzheimer's Association conferences in the past 36 months.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Funding Source: Research reported in this publication received support from the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under Award Number R01AG050504 and K24AG054560 and the Clinical and Translational Science Award program, through the NIH National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences award UL1TR002373. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Shah MN, Jacobsohn GC, Jones CMC, et al. Care transitions intervention reduces ED revisits in cognitively impaired patients. Alzheimer's Dement. 2022;8:e12261. 10.1002/trc2.12261

REFERENCES

- 1. Pitts SR, Carrier ER, Rich EC, Kellerman AL. Where Americans get acute care: increasingly it's not at their doctor's office. Health Affairs (Millwood). 2010;29:1620‐1629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Trends in Emergency Department Visits ‐ HCUP Fast Stats. Retrieved December 3, 2020, from https://www.hcup‐us.ahrq.gov/faststats/NationalTrendsEDServlet?measure1=01&characteristic1=12&measure2=02&characteristic2=12&expansionInfoState=hide&dataTablesState=hide&definitionsState=hide&exportState=hide

- 3. Hughes JM, Freiermuth CE, Shepherd‐Banigan M, et al. Emergency department interventions for older adults: a systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67:1516‐1525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. McCusker J, Cardin S, Bellavance F, et al. Return to the emergency department among elders: patterns and predictors. Acad Emerg Med Off J Soc Acad Emerg Med. 2000;7(3):249‐259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hwang U, Shah MN, Carpenter CR, Han J, Adams J, Siu A. The CARE SPAN—Transforming emergency care for older adults. Health Affairs. 2013;32(12):2116‐2121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lowthian J, Straney LD, Brand CA, et al. Unplanned early return to the emergency department by older patients: the safe elderly emergency department discharge (SEED) project. Age Ageing. 2016;45(2):255‐261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lucke JA, de Gelder J, Heringhaus C, et al. Impaired cognition is associated with adverse outcome in older patients in the emergency department; the acutely presenting older patients (APOP) study. Age Aging. 2018;47(5):679‐684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. LaMantia MA, Stump TE, Messina FC, Miller DK, Callahan CM. Emergency department use among older adults with dementia. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2016;30:35‐40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kent T, Lesser A, Israni J, Hwang U, Carpenter C, Ko KJ. 30‐Day emergency department revisit rates among older adults with documented dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67(11):2254‐2259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Feng Z, Coots LA, Kaganova Y, Wiener JM. Hospital and ED use among medicare beneficieries with dementia varies by setting and proximity to death. Health Affairs. 2014;33(4):683‐690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Han JH, Bryce SN, Ely EW, Kripalani S, et al. The effect of cognitive impairment on the accuracy of the presenting complaint and discharge instruction comprehension in older emergency department patients. Ann Emerg Med. 2011;57(6):662‐671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hastings SN, Barrett A, Weinberger M, et al. Older patients’ understanding of emergency department discharge information and its relationship with adverse outcomes. J Patient Saf. 2011;7(1):19‐25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sheikh H, Brezar A, Dzwonek A, Yau L, Calder LA. Patient understanding of discharge instructions in the emergency department: do different patients need different approaches?. Int J Emerg Med. 2018;11(5):1‐7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Nunez S, Hexdall A, Aguirre‐Jaime A. Unscheduled returns to the emergency department: an outcome of medical errors?. Qual Saf Health Care. 2006;15:102‐108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sellers CR, Duckles JM, Shah MN, et al. What makes for “successful” transitions from the emergency department to home and community among older adults?. Inter J of Qual Methods. 2013;12:815‐816. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Greiner A. White space or black hole: what can we do to improve care transitions?. Issue Brief #6 ABIM Foundation. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Coleman EA, Smith JD, Frank JC, Min S, Parry C, Kramer AM. Preparing patients and caregivers to participate in care delivered across settings: the care transitions intervention. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(11):1817‐1825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Carpenter CR, Bassett ER, Fischer GM, Shirshekan J, Galvin JE, Morris JC. Four sensitive screening tools to detect cognitive dysfunction in geriatric emergency department patients: brief Alzheimer's screen, short blessed test, Ottawa 3DY, and the caregiver‐completed AD8. Acad Emerg Med. 2011;18(4):374‐384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Manea L, Gilbody S, McMillan D. Optimal cut‐off score for diagnosing depression with the patient health questionnaire (PHQ‐9): a meta‐analysis. CMAJ. 2012;184(3):E191‐E196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mi R, Hollander MM, Jones CMC, et al. A randomized controlled trial testing the effectiveness of a paramedic‐delivered care transitions intervention to reduce emergency department revisits. BMC Geriatr. 2018;18:104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Katzman R, Brown T, Fuld P, Peck A, Schechter R, Schimmel H. Validation of a short orientation‐memory‐concentration test of cognitive impairment. Amer J of Psy. 1983;140:734‐739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kaji AH, Schriger D, Green S. Looking through the retrospectoscope: reducing bias in emergency medicine chart review studies. Ann Emerg Med. 2014;64:292‐298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wild B, Eckl A, Herzog W, et al. Assessing generalized anxiety disorder in elderly people using the GAD‐7 and GAD‐2 scales: results of a validation study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2014;22(10):1029‐1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ware JE, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12‐item short‐form health survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34(3):220‐233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wynia MK, Osborn CY. Health literacy and communication quality in health care organizations. J Health Commun. 2010;15(SUPPL. 2):102‐115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Aronow H, Fila S, Martinez B, Sosna T. Depression and coleman care transitions intervention. Soc Work Health Care. 2018;57(9):750‐761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Musey PI, Patel R, Fry C, Jimenez G, Koene R, Kline JA. Anxiety associated with increased risk for emergency department recidivism in patients with low‐risk chest pain. Amer J Card. 2018;122(7):1133‐1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kunik ME, Roundy K, Veazey C, et al. Surprisingly high prevalence of anxiety and depression in chronic breathing disorders. Chest. 2005;127(4):1205‐1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Griffey RT, Kennedy SK, D'Agostino McGowan L, Goodman M, Kaphingst KA. Is low health literacy associated with increased emergency department utilization and recidivism?. [published correction appears in Acad Emerg Med. 2015;22(4):497. McGownan, Lucy [corrected to D'Agostino McGowan, Lucy]]. Acad Emerg Med. 2014;21(10):1109‐1115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Schumacher JR, Hall AG, Davis TC, et al. Potentially preventable use of emergency services: the role of low health literacy. Med Care. 2013;51(8):654‐658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Chaudhry S, Jin L, Meltzer D. Use of a self‐report‐generated Charlson comorbidity index for predicting mortality. Med Care. 2005;43(6):607‐615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Guttman A, Afilalo M, Guttman R, et al. An emergency department‐based nurse discharge coordinator for elder patients: does it make a difference?. Acad Emerg Med. 2004;11:1318‐1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Biese KJ, Busby‐Whitehead J, Cai J, et al. Telephone follow‐up for older adults discharged to home from the emergency department: a pragmatic randomized controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2018;66(3):446‐451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Basic D, Conforti DA. A prospective, randomised controlled trial of an aged care nurse intervention within the emergency department. Aust Health Rev. 2005;29:51‐59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. McCusker J, Dendukuri N, Tousignant P, et al. Rapid two‐stage emergency department intervention for seniors: impact on continuity of care. Acad Emerg Med. 2003;10:233‐243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Mion LC, Palmer RM, Meldon SW, et al. Case finding and referral model for emergency department elders: a randomized clinical trial. Ann of Emerg Med. 2003;41:57‐68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Miller DK, Lewis LM, Nork MJ, et al. Controlled trial of a geriatric case finding and liaison service in an emergency department. J Amer Geriatr Soc. 1996;44:513‐520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Runciman P, Currie CT, Nicol M, et al. Discharge of elderly people from an accident and emergency department: evaluation of health visitor follow‐up. J Adv Nurs. 1996;24:711‐718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Caplan GA, Williams AJ, Daly B, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of comprehensive geriatric assessment and multidisciplinary intervention after discharge of elderly from the emergency department—the DEED II study. J Am Geriatr Soci. 2004;52:1417‐1423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Schumacher JR, Lutz BJ, Hall AG, et al. Impact of an emergency department‐to‐home transitional care intervention on health service use in Medicare beneficiaries: a mixed methods study. Med Care. 2021;59(1):29‐37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Muhlestein DB, Saunders R, Richards R, McClellan M. Recent progress in the value journey: growth of ACOs and value‐based payment models in 2018. Health Affairs Blog Published. 2018. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20180810.481968/full/. Accessed June 20, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Wang N, Amaize A, Chen J. Accountable care hospitals and preventable emergency department visits for rural dementia patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2021;69:185‐190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Lin MP, Burke RC, Orav EJ. Ambulatory follow up and outcomes among medicare beneficiaries after emergency department discharge. JAMA Net Open. 2020;3(10):e2019878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Amjad H, Carmichael D, Austin AM, Chang C, Bynum JPW. Continuity of care and health care utilization in older adults with dementia in fee‐for‐service Medicare. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(9):1371‐1378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]