Abstract

Mitochondria are key regulators of energy supply and cell death. Generation of ATP within mitochondria occurs through oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS), a process which utilizes the four complexes (complex I–IV) of the electron transport chain and ATP synthase. Certain oncogenic mutations (e.g., LKB1 or mIDH) can further enhance the reliance of cancer cells on OXPHOS for their energetic requirements, rendering cells sensitive to complex I inhibition and highlighting the potential value of complex I as a therapeutic target. Herein, we describe the discovery of a potent, selective, and species cross-reactive complex I inhibitor. A high-throughput screen of the Bayer compound library followed by hit triaging and initial hit-to-lead activities led to a lead structure which was further optimized in a comprehensive lead optimization campaign. Focusing on balancing potency and metabolic stability, this program resulted in the identification of BAY-179, an excellent in vivo suitable tool with which to probe the biological relevance of complex I inhibition in cancer indications.

Keywords: Cross-reactive complex I inhibitor, Structure−activity relationships, Amide isosteres, Antitumor treatment

Mitochondria are key regulators of energy supply and cell death. The mitochondrial electron transport chain consists of four enzyme complexes that transfer electrons from nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD) to oxygen. During electron transfer, the electron transport chain pumps protons into the intermembrane space, generating a gradient across the inner mitochondrial membrane that is used by complex V to drive adenosine triphosphate (ATP) synthesis (Figure 1A).1 Recent studies have shown that tumor cells harboring specific mutations (e.g., LKB1 or mIDH) are more sensitive to complex I inhibition than cells without these mutations,2,3 raising the possibility of exploiting complex I as an antitumor target. Several inhibitors of complex I have been described, including rotenone,4,5 BAY 87-2243,6−8 and the antidiabetic drugs metformin9,10 and phenformin11 (Figure 1B). However, weak inhibitor activity (such as that with metformin and phenformin), off-target effects (with rotenone), and a lack of cross-reactivity between human and mouse (with BAY 87-2243) prevent their use in the in vivo validation of complex I as a therapeutic target. Finally, IACS-010759 was described to specifically inhibit complex I and is currently being investigated in phase I clinical studies in patients with advanced tumors (NCT03291938) as well as acute myeloid leukemia (AML; NCT02882321). Preclinical studies show strong inhibition of in vivo growth in subcutaneous AML and intracranial brain mouse models; however, no data concerning cross-reactivity in other species or tolerability in humans are currently available.12,13 Therefore, we aimed to identify a novel, potent, selective, species cross-reactive complex I inhibitor which could be used to validate the therapeutic potential of complex I as an antitumor target in vivo.

Figure 1.

(A) Schematic of the mitochondrial electron transport chain. (B) Representative list of known inhibitors of complex I.

Our search commenced with a high-throughput screen of the Bayer compound collection with H1299 cells transfected with an ATP-dependent luciferase to identify inhibitors of the respiratory chain. To specifically identify complex I inhibitors and to exclude compounds acting more downstream on the respiratory chain, ATP-dependent cellular luminescence was measured in the absence (M1) and in the presence of the complex II substrate succinate (M2) (Figure 2A). After hit triaging and clustering of the hits, six clusters were identified for initial hit-to-lead activities including focused medicinal chemistry optimization (Figure 2B). Selection criteria for the prioritization of these six clusters were potency, full cross-reactivity between human, rat, and mouse Complex I, logD, as well as chemical diversity. The most potent representatives of these clusters showed IC50 values in the range of 0.5–3 μM on human complex I.

Figure 2.

(A) An ATP-dependent luciferase reporter assay was used to determine the effect of electron transport chain inhibitors on ATP synthesis in H1299 cells (left). Luminescent measurements were performed before (M1) and after (M2) addition of complex II substrate succinate. Thereby, this assay can discriminate specific complex I inhibitors (e.g., rotenone, inhibitory effect overridden by succinate) from other mode of actions affecting cellular ATP levels like complex III inhibition by antimycin A or mitochondrial decouplers like FCCP (no rescue effect by succinate). (B) High-throughput screen hit triaging resulted in the identification of one priority cluster represented by screening hit 1.

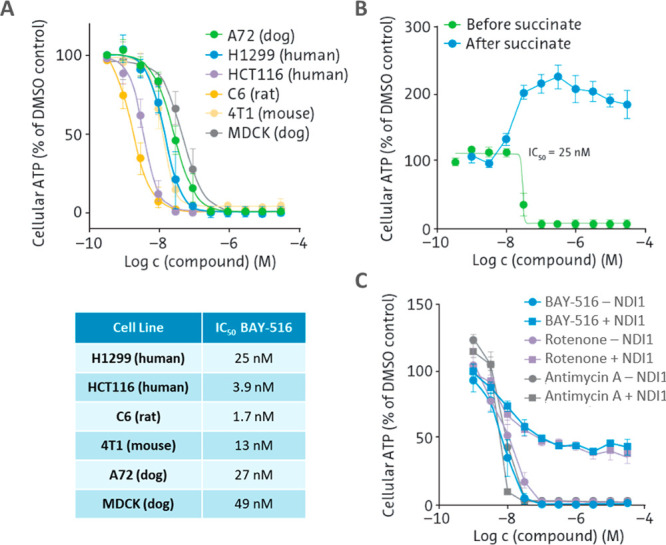

A limited hit-to-lead program was run on all six clusters using analogues already available in the Bayer compound library as well as the synthesis of new analogues. After first optimization cycles, one cluster showed a clear path forward in terms of improvement of potency and was prioritized (Figure 2B). Initial structure–activity relationships (SARs) derived from compounds already available in the Bayer compound library showed that the amide portion had a clear influence on potency (e.g., compounds 1–4, Table 1). Therefore, various heterocycles (5, 6) were introduced which resulted in compounds with improved potency. Heterocyclic head groups described in the literature with insecticidal activity and likely mode of action based on complex I inhibition were introduced (7, 8), which led to a further improvement of the potency (e.g., 8).14 The novel complex I inhibitor 8 (BAY-516) reduced cellular ATP with an IC50 value of 25 nM (Table 1). Compound 8 displayed species cross-reactivity, showing reduction of ATP in cells derived from a variety of species (Figure 3A). The specificity of 8 was confirmed by rescuing the ATP decrease through the addition of the complex II substrate succinate (Figure 3B) and by the expression of the yeast protein NDI1, a rotenone-insensitive NADH-quinone oxidoreductase from Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Figure 3C).15 Additionally, in biochemical assays against bovine complexes I–V, 8 showed comparable activity to that displayed in the cellular complex I luciferase assay and no detectable inhibition of other components of the respiratory chain (see the Supporting Information). Due to the favorable potency, selectivity, and species cross-reactivity displayed by 8, this compound was progressed into first in vivo experiments.

Table 1. SAR Studies of the Amide Moiety.

Reported IC50 values are average values of at least two independent measurements.

Figure 3.

(A) An ATP-dependent luciferase reporter assay was used to determine complex I inhibition in a variety of cell lines from different species to assess species cross-reactivity. (B) Effects of 8 before and after addition of the complex II substrate succinate to determine specificity. (C) 8 was tested in cells transfected with NDI1, a rotenone-insensitive NADH-quinone oxidoreductase from Saccharomyces cerevisiae15 to further determine the inhibitor specificity. Reported IC50 values are average values of at least two independent measurements.

Despite displaying some activity in a mouse xenograft model, compound 8 showed significant pharmacokinetic liabilities in terms of a low metabolic stability observed in vitro and a corresponding high in vivo blood clearance equal to roughly 2.5 times the liver blood flow in rats. In addition, the compound displayed an extremely low aqueous solubility (0.1 mg/L at pH 7.4) and a very high lipophilicity (see Table 2).

Table 2. Investigation of Amide Isosteres.

Not determined.

Reported IC50 values are average values of at least two independent measurements.

An optimization program was initiated with the goal of improving the pharmacokinetic and physiochemical profile of lead structure 8. The focus of the first optimization cycles was to improve the metabolic stability. Metabolite identification studies established that the amide function of compound 8 was the key structural liability. Therefore, options to stabilize or replace the amide were evaluated. Key molecules which were synthesized and tested for complex I inhibition and metabolic stability are presented in Table 2.

Compounds 9–11 were designed to evaluate the SAR around the central amide group. N-Methylation to give 9 was tolerated without significant loss of potency (cf. compound 6, Table 1), a result which indicated that it may be possible to replace the amide function by cyclic isosteres with the nitrogen atom as part of a ring. Disappointingly, the metabolic stability of compound 9 in rat hepatocytes was further reduced as compared with 8 (Table 2). Introduction of a methyl group alpha to the amide (compound 10) was tolerated, and a significant improvement of the stability in rat hepatocytes was observed in vitro. However, this did not translate into a significant reduction in blood clearance in vivo for 10 as compared to 8. Introduction of a second methyl group (compound 11) led to a dramatic loss of potency.

Next, we evaluated the option of embedding the amide function in a heterocyclic system. All direct amide isosteres bearing an sp2 center adjacent to the piperidine (e.g., compound 12, but also further five-membered heterocyclic analogues not shown) exhibited only weak potency. However, formation of a lactam ring with an sp3 center adjacent to the piperidine (compound 13) was tolerated. Compound 13 was separated into the enantiomers by chiral HPLC. The more potent enantiomer 13entA (absolute stereochemistry was not elucidated) displayed a 2-fold improvement in metabolic stability in rat hepatocytes as compared to 8 but showed significantly reduced blood clearance in vivo. Ring annulation on the opposite amide side, resulting in formation of the benzimidazole derivative 14, led to a significant reduction in potency compared to the amides. Despite this loss in potency, we also observed a significant decrease in the lipophilicity, which led to an overall increase in the lipophilic ligand efficiency (LLE). Additionally, compound 14 displayed improved properties in vivo, with a 9-fold reduction in blood clearance in rats as compared with 8.

Whereas attempts to further optimize the physicochemical and DMPK profile of the lactam subseries (i.e., 13) did not lead to significant progress, a rapid improvement could be obtained in the benzimidazole subseries exemplified by 14. Therefore, further compound optimization, which finally led to the identification of a preclinical candidate, focused on improving the potency of the imidazole subclass.

We began by exploring SAR around the benzofuran portion of the scaffold, decorating various positions of the benzofuran with sterically small substituents such as methyl, fluoro, chloro, or cyano (e.g., 16 and 17, Table 3). Unfortunately, these substitutions resulted in compounds with a 2- to 10-fold decrease in potency. Introduction of nitrogen into the benzofuran skeleton, as exemplified by compound 18, also led to decrease in potency, displaying an IC50 value of 770 nM. Although benzothiazole derivative 19 gave an IC50 value of 710 nM, installation of a benzimidazole (e.g., 20) resulted in complete abrogation of activity. Deletion of the benzene portion of the benzofuran bicycle, as represented by 21, also led to a complete loss of activity, highlighting the importance of this bicyclic moiety. Compound 22, bearing a simple aryl group, further emphasized this trend, resulting in only weak activity on complex I (IC50 = 10 μM). Compounds with an aliphatic substituent on the benzofuran skeleton were also tested, with little success (data not shown). Significant effort was also invested into exploring SAR at the thiazole linker. Unfortunately, all alternative five-membered heterocycles we explored led to a 4–10-fold decrease in potency (data not shown). Small changes at the 4-position of the piperidine core, such as the introduction of a fluoro or hydroxy group, led to similar deterioration of complex I activity.

Table 3. SAR Studies around the Benzofuran Moiety.

Reported IC50 values are average values of at least two independent measurements.

As we were unable to identify any significant potency handles on the benzofuran side of the scaffold, we revisited the benzimidazole head group (Table 4). We began by probing the benzylic position through the synthesis of compounds 23–25. Installation of a single methyl group (23) led to a slight decrease in potency (IC50 = 0.4 μM) as compared with compound 15, while the addition of a second methyl group (24) resulted in a further drop in activity. Conversion of the basic piperidine nitrogen of compound 15 into an amide via installation of a carbonyl function (25) resulted in a significant loss in potency, highlighting the importance of this basic center. Introduction of sterically small substituents on the benzimidazole ring, including nitrile (26), methyl, or amino (not shown), led to a decline in potency relative to compound 15. Next, we investigated the imidazole ring of the bicycle by synthesizing compounds 27–30. The corresponding benzoxazole (27) or benzothiazole (28) led to a nearly 10-fold decrease in potency compared with 15, resulting in micromolar complex I potency (Table 4). While N-alkylation of the benzimidazole moiety with a methyl group (29) resulted in a moderate drop in potency (IC50 = 0.7 μM), the ethyl derivative 30 elicited a complete loss of complex I activity. Synthesis and testing of phenyl-substituted imidazole 31 revealed a roughly 4-fold decrease in potency as compared with 15, indicating the importance of the annulated bicyclic structure for activity. This was further highlighted by deletion of the phenyl substituent to afford imidazole 32, which displayed only micromolar activity on complex I. These results reinforced the importance of the benzimidazole structure and further revealed the steep potency cliffs presented by the chemical series.

Table 4. SAR Studies of the Benzimidazole Moiety.

Reported IC50 values are average values of at least two independent measurements.

Despite encountering difficulty in increasing the potency, we were encouraged by only minor decreases in activity upon the installation of a range of alternative bicyclic moieties (compounds 33–36, Table 5). Especially noteworthy were compounds bearing further nitrogen substitution in the six-membered ring (e.g., 34–36), which significantly reduced lipophilicity and increased LLE. These results suggested the possibility of introducing nitrogen atoms into the benzimidazole framework as a means to reduce logD, while at the same time potentially influencing potency.

Table 5. SAR Studies of the Benzimidazole Moiety.

Reported IC50 values are average values of at least two independent measurements.

To this end, we synthesized imidazopyridine derivatives 37 and 38. To our delight, we observed an increase in activity for both analogues (79 and 38 nM, respectively), in addition to a further reduction in logD and an increase in the LLE as compared to 15. Furthermore, pyrimidine analogue 39 revealed a similar increase in potency, resulting in a reduction of ATP production with an IC50 value of 80 nM. As previously observed, further attachment of sterically small substituents such as methyl (compounds 40 and 41) or fluoro (42) did not lead to additional increases in potency (Table 5).

As compounds 38 (BAY-178) and 37 (BAY-179) were our most promising two candidates with respect to potency and physicochemical properties, we advanced these two compounds to further in vitro and in vivo DMPK experiments. Table 6 provides an overview of the potency, physicochemical properties, and DMPK profile of key compounds 37 and 38. Importantly, both 37 and 38 retain species cross-reactivity, showing comparable cellular activity across complex I assays from a variety of preclinically relevant species. Both compounds displayed moderate to good in vitro metabolic stability, with 37 showing slightly higher stability in rat hepatocytes (Fmax = 81%) than 38 (Fmax = 63%). Additionally, we observed a tendency for better permeability of 37 in the Caco-2 assay; however, both compounds displayed high permeability with little to no efflux. Due to the presence of the basic nitrogen, we expected that binding to the hERG (human ether-a-go-go-related gene) channel could be a potential issue for this structural class.16 While, indeed, we observed binding in the hERG patch clamp assay for both compounds, these activities represented a more than 20-fold selectivity over the on-target complex I activity, alleviating some of our potential concerns with respect to cardiac related toxicities. Both compounds 37 and 38 displayed relatively low aqueous solubility at pH 6.6 and a high degree of mouse plasma protein binding, and neither compound showed any binding in the PXR (pregnane X receptor) assay, indicating a low risk for CYP induction. In vivo exposure in the rat was superior for compound 37, which showed a 3-fold lower blood clearance of 0.4 L/h/kg compared with 1.2 L/h/kg for compound 38. Additionally, 37 displayed a high volume of distribution (Vss = 2.2 L/kg) and long half-life (t1/2 = 6.2 h) in rats. High bioavailability was observed for both derivatives. These data, combined with the more favorable CYP inhibition profile displayed by 37, resulted in the selection of this compound for further preclinical profiling in vivo. Preliminary exposure studies in mice showed coverage of the cellular IC50 for approximately 8 h at 14 mg/kg suggesting a potential starting dose for more detailed in vivo experiments.

Table 6. Properties of Key Compounds 37 and 38.

| compd | 37 | 38 |

|---|---|---|

| Complex I, human IC50 (μM) | 0.079 | 0.038 |

| Complex I, mouse IC50 (μM) | 0.038 | 0.026 |

| Complex I, rat IC50 (μM) | 0.027 | 0.022 |

| Complex I, dog IC50 (μM) | 0.047 | 0.037 |

| logD (LLE) | 2.8 (4.3) | 2.7 (4.8) |

| solubility @ pH 6.5 (mg/L) | 1.6 | 3.4 |

| rat hepatocyte stability Fmax (%) | 81 | 63 |

| Caco-2 Papp A–B (nm/s) | 92 | 77 |

| Efflux ratio | 0.44 | 1.6 |

| CYP1A2 IC50 (μM) | >20 | >20 |

| CYP2C8 IC50 (μM) | 7.8 | 0.59 |

| CYP2C9 IC50 (μM) | 15 | 4.3 |

| CYP2D6 IC50 (μM) | >20 | 0.45 |

| CYP3A4 IC50 (μM) | >20 | 0.86 |

| PXR MEC (μM) | >50 | >50 |

| hERG, patch clamp IC50 (μM) | 3.0 | 1.8 |

| plamsa protein binding (mouse) funbound (%) | 0.43 | 0.59 |

| in vivo pharmacokinetics in male rat (0.4 mg/kg iv, 0.8 mg/kg po) | ||

| CLb (L/h/kg) | 0.4 | 1.2 |

| Vss (L/kg) | 2.2 | 3.2 |

| t1/2 (h) | 6.2 | 3.1 |

| po AUCnorm (kg·h/L) | 3.1 | 1.0 |

| Cmax,norm (kg/L) | 0.23 | 0.09 |

| F (%) | 76 | 80 |

The general synthesis of the benzimidazole-containing complex I inhibitors, as represented by the synthesis of 37, is outlined in Scheme 1. Formation of the thiazole ring was accomplished via condensation of commercially available or readily prepared α-bromomethyl ketones (e.g., 43) with tert-butyl 4-carbamothioylpiperidine-1-carboxylate (44).17 Concomitant formation of HBr additionally induced tert-butoxycarbonyl (Boc) deprotection and formation of the piperidine hydrobromide salt 45. These salts represented key building blocks in the preparation of a large majority of compounds. N-Alkylation of the piperidine ring with commercially available 2-(chloromethyl)-1H-imidazo[4,5-b]pyridine hydrochloride (46) under basic conditions led directly to 37. As a large variety of electrophilic building blocks of type 46 are commercially available, the alkylation of piperidine salts (e.g., 45) represents an efficient way to assemble a large number of diverse compounds, which allowed us to rapidly explore the combination of various substituents in the bicyclic extremities. Alternatively, N-alkylation of 45 with methyl bromoacetate led to the corresponding ester, which was saponified under standard conditions to give acid 47. Amide bond formation between 47 and 2,3-diaminopyridine (48) was accomplished using HATU,18 and the resulting amide 49 was cyclized to the benzimidazole by condensation in refluxing acetic acid19,20 to afford 37. On the other hand, amides of this type could be cyclized under Lewis acid catalyzed conditions via the use of ytterbium(III) triflate in refluxing toluene.21 This alternative route (i.e., amide formation followed by cyclization) gave us flexibility in the installation of various benzimidazole groups for which the corresponding alkylating agents (i.e., analogues of 46) were not available. Additionally, carboxylic acids characterized by 47 represented important building blocks for the synthesis of other complex I inhibitors not bearing a benzimidazole head group (see Tables 1 and 2). Overall, this convergent modular construction allowed for a rapid buildup of SAR in both extremities of this structural series.

Scheme 1. Synthesis of 37.

In summary, starting from the moderately potent HTS hit 1, our initial focus on increasing potency resulted in lead compound 8 (BAY-516). Despite displaying excellent potency, species cross-reactivity, and selectivity over other complexes, 8 carried significant pharmacokinetic liabilities resulting from its highly lipophilic nature. Further variation of the head group led to the identification of a series of benzimidazole-containing compounds which showed greatly reduced blood clearance in vivo, in addition to a markedly reduced logD. While steep SAR was observed for many structural modifications, increased polarity through the addition of nitrogen(s) to the bicyclic imidazole head group resulted in further improvements in the potency, DMPK, and physicochemical parameters, and ultimately to the discovery of 37.

Due to its excellent potency, species cross-reactivity, selectivity over other complexes, and pharmacokinetic properties, 37 is an excellent in vivo suitable tool with which to probe the biological relevance of complex I inhibition in cancer indications. For this reason, BAY-179 (37) has been donated as a chemical probe along with the negative control BAY-070.22 Both are available free of charge through the Structural Genomics Consortium (SGC), along with other chemical probes donated by Bayer.23−3237 and its negative control can be used together alongside other chemically differentiated inhibitors (e.g., IACS-010759) to further probe the biology of complex I in various cancer and other relevant indications.31 Therefore, our further investigation is directed toward exploring the vulnerabilities of additional cancer types, including various solid tumor indications, to complex I inhibition. Finally, in vivo studies investigating the therapeutic window of such an approach, in addition to a comparison of our complex I inhibitors with additional compounds described earlier will be reported in due course.

Acknowledgments

Valuable contributions by Stuart Cameron, Udo Battaglia, Ben Lam, and Michael Tait (all from Peakdale Molecular, now Concept Life Sciences) to the synthesis of early compounds is gratefully acknowledged. We would like to acknowledge Hue-Quan Lao, Andrea Koehlke-Nork, Michael Tietz, Anni Knitter, Lisa Schaelicke, Martin Schoetz, and Karl Sauvageot-Witzku for assisting in the preparation of compounds and Nina Hartmann for performing the in vitro characterization of the compounds.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsmedchemlett.1c00666.

Procedures for bioassays and DMPK studies; details for the synthesis of compounds 1–42 (PDF)

Author Contributions

† J.M. and W.S. contributed equally.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Baradaran R.; Berrisford J. M.; Minhas G. S.; Sazanov L. A. Crystal structure of the entire respiratory complex I. Nature 2013, 494, 443–448. 10.1038/nature11871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shackelford D. B.; Abt E.; Gerken L.; Vasquez D. S.; Seki A.; Leblanc M.; Wei L.; Fishbein M. C.; Czernin J.; Mischel P. S.; Shaw R. J. LKB1 inactivation dictates therapeutic response of non-small cell lung cancer to the metabolism drug phenformin. Cancer Cell 2013, 23, 143–158. 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan P.; Ito K.; Perez-Lorenzo R.; Del Guzzo C.; Lee J. H.; Shen C.-H.; Bosenberg M. W.; McMahon M.; Cantley L. C.; Zheng B. Phenformin enhances the therapeutic benefit of BRAFV600E inhibition in melanoma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2013, 110, 18226–18231. 10.1073/pnas.1317577110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li N.; Ragheb K.; Lawler G.; Sturgis J.; Rajwa B.; Melendez J. A.; Robinson J. P. Mitochondrial complex I inhibitor rotenone induces apoptosis through enhancing mitochondrial reactive oxygen species production. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 8516–8525. 10.1074/jbc.M210432200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinz S.; Freyberger A.; Lawrenz B.; Schladt L.; Schmuck G.; Ellinger-Ziegelbauer H. Mechanistic investigations of the mitochondrial complex I inhibitor rotenone in the context of pharmacological and safety evaluation. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 45465. 10.1038/srep45465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellinghaus P.; Heisler I.; Unterschemmann K.; Haerter M.; Beck H.; Greschat S.; Ehrmann A.; Summer H.; Flamme I.; Oehme F.; Thierauch K.; Michels M.; Hess-Stumpp H.; Ziegelbauer K. BAY 87–2243, a highly potent and selective inhibitor of hypoxia-induced gene activation has antitumor activities by inhibition of mitochondrial complex I. Cancer Med. 2013, 2, 611–624. 10.1002/cam4.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helbig L.; Koi L.; Brüchner K.; Gurtner K.; Hess-Stumpp H.; Unterschemmann K.; Baumann M.; Zips D.; Yaromina A. BAY 87–2243, a novel inhibitor of hypoxia-induced gene activation, improves local tumor control after fractionated irradiation in a schedule-dependent manner in head and neck human xenografts. Radiat. Oncol. 2014, 9, 207. 10.1186/1748-717X-9-207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schöckel L.; Glasauer A.; Basit F.; Bitschar K.; Truong H.; Erdmann G.; Algire C.; Hägebarth A.; Willems P. H. G. M.; Kopitz C.; Koopman W. J. H.; Héroult M. Targeting mitochondrial complex I using BAY 87–2243 reduces melanoma tumor growth. Cancer Metab 2015, 3, 11. 10.1186/s40170-015-0138-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollak M. N. Investigating metformin for cancer prevention and treatment: the end of the beginning. Cancer Discovery 2012, 2, 778–790. 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kordes S.; Pollak M. N.; Zwinderman A. H.; Mathôt R. A.; Weterman M. J.; Beeker A.; Punt C. J.; Richel D. J.; Wilmink J. W. Metformin in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer: a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol 2015, 16, 839–847. 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00027-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García Rubiño M. E.; Carrillo E.; Ruiz Alcalá G.; Domínguez-Martín A.; Marchal J. A.; Boulaiz H. Phenformin as an anticancer agent: challenges and prospects. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3316. 10.3390/ijms20133316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molina J. R.; Sun Y.; Protopopova M.; Gera S.; Bandi M.; Bristow C.; McAfoos T.; Morlacchi P.; Ackroyd J.; Agip A-N. A.; Al-Atrash G.; Asara J.; Bardenhagen J.; Carrillo C. C.; Carroll C.; Chang E.; Ciurea S.; Cross J. B.; Czako B.; Deem A.; Daver N.; de Groot J. F.; Dong J.-W.; Feng N.; Gao G.; Gay J.; Do M. G.; Greer J.; Giuliani V.; Han J.; Han L.; Henry V. K.; Hirst J.; Huang S.; Jiang Y.; Kang Z.; Khor T.; Konoplev S.; Lin Y.-H.; Liu G.; Lodi A.; Lofton T.; Ma H.; Mahendra M.; Matre P.; Mullinax R.; Peoples M.; Petrocchi A.; Rodriguez-Canale J.; Serreli R.; Shi T.; Smith M.; Tabe Y.; Theroff J.; Tiziani S.; Xu Q.; Zhang Q.; Muller F.; DePinho R. A.; Toniatti C.; Draetta G. F.; Heffernan T. P.; Konopleva M.; Jones P.; Di Francesco M. E.; Marszalek J. R. An inhibitor of oxidative phosphorylation exploits cancer vulnerability. Nat. Med. 2018, 24, 1036–1046. 10.1038/s41591-018-0052-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuji A.; Akao T.; Masuya T.; Murai M.; Miyoshi H. IACS-010759, a potent inhibitor of glycolysis-deficient hypoxic tumor cells, inhibits mitochondrial respiratory complex I through a unique mechanism. J. Biol. Chem. 2020, 295 (21), 7481–7491. 10.1074/jbc.RA120.013366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samaritoni J. G.; Babcock J. M.; Schlenz M. L.; Johnson G. W. Methylene group modifications of the N-(isothiazol-5-yl)phenylacetamides. Synthesis and insecticidal activity. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1999, 47, 3381–3388. 10.1021/jf990095s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seo B. B.; Kitajima-Ihara T.; Chan E. K. L.; Scheffler I. E.; Matsuno-Yagi A.; Yagi T. Molecular remedy of complex I defects: rotenone-insensitive internal NADH-quinone oxidoreductase of Saccharomyces cerevisiae mitochondria restores the NADH oxidase activity of complex I-deficient mammalian cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1998, 95, 9167–9171. 10.1073/pnas.95.16.9167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aronov A. M. Predictive in silico modeling for hERG channel blockers. Drug Discovery Today 2005, 10, 149–155. 10.1016/S1359-6446(04)03278-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bregman H.; Buchanan J. L.; Chakka N.; Dimauro E. F.; Du B.; Nguyen H. N.; Zheng X. M.. Aryl carboxamide derivatives as sodium channel inhibitors for treatment of pain. PCT Int. Appl. WO 2011/103196, 2011.

- Valeur E.; Bradley M. Amide bond formation: beyond the myth of coupling reagents. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009, 38, 606–631. 10.1039/B701677H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao H.; Fu H.; Qiao R. Copper-catalyzed direct amination of ortho-functionalized haloarenes with sodium azide as the amino source. J. Org. Chem. 2010, 75, 3311–3316. 10.1021/jo100345t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chai Y.; Paul A.; Rettig M.; Wilson W. D.; Boykin D. W. Design and synthesis of heterocyclic cations for specific DNA recognition: from AT-rich to mixed-base-pair DNA sequences. J. Org. Chem. 2014, 79, 852–866. 10.1021/jo402599s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curini M.; Epifano F.; Montanari F.; Rosati O.; Taccone S. Ytterbium triflate promoted synthesis of benzimidazole derivatives. Synlett 2004, 1832–1834. 10.1055/s-2004-829555. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- The structure of the negative

control compound

is shown below and derived from the left-hand side of compound 20 along with the right-hand side of the active probe 37. BAY-070 complex 1 IC50 > 30 μM. More

information on the negative control BAY-070 can be found in the probe

package on the SGC web site at https://www.sgc-ffm.uni-frankfurt.de/#!specificprobeoverview/BAY-179.

- von Nussbaum F.; Li V. M.; Meibom D.; Anlauf S.; Bechem M.; Delbeck M.; Gerisch M.; Harrenga A.; Karthaus D.; Lang D.; Lustig K.; Mittendorf J.; Schäfer M.; Schäfer S.; Schamberger J. Potent and selective human neutrophil elastase inhibitors with novel equatorial ring topology: in vivo efficacy of the polar pyrimidopyridazine BAY-8040 in a pulmonary arterial hypertension rat model. ChemMedChem. 2016, 11, 199–206. 10.1002/cmdc.201500269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eggert E.; Hillig R. C.; Koehr S.; Stöckigt D.; Weiske J.; Barak N.; Mowat J.; Brumby T.; Christ C. D.; ter Laak A.; Lang T.; Fernandez-Montalvan A. E.; Badock V.; Weinmann H.; Hartung I. V.; Barsyte-Lovejoy D.; Szewczyk M.; Kennedy S.; Li F.; Vedadi M.; Brown P. J.; Santhakumar V.; Arrowsmith C. H.; Stellfeld T.; Stresemann C. Discovery and characterization of a highly potent and selective aminopyrazoline-based in vivo probe (BAY-598) for the protein lysine methyltransferase SMYD2. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 59, 4578–4600. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b01890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouché L.; Christ C. D.; Siegel S.; Fernández-Montalván A. E.; Holton S. J.; Fedorov O.; ter Laak A.; Sugawara T.; Stöckigt D.; Tallant C.; Bennett J.; Monteiro O.; Díaz-Sáez L.; Siejka P.; Meier J.; Pütter V.; Weiske J.; Müller S.; Huber K. V. M.; Hartung I. V.; Haendler B. Benzoisoquinolinediones as potent and selective inhibitors of BRPF2 and TAF1/TAF1L bromodomains. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 60, 4002–4022. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.7b00306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Montalván A. E.; Berger M.; Kuropka B.; Koo S. J.; Badock V.; Weiske J.; Puetter V.; Holton S. J.; Stöckigt D.; ter Laak A.; Centrella P. A.; Clark M. A.; Dumelin C. E.; Sigel E. A.; Soutter H. H.; Troast D. M.; Zhang Y.; Cuozzo J. W.; Keefe A. D.; Roche D.; Rodeschini V.; Chaikuad A.; Díaz-Sáez L.; Bennett J. M.; Fedorov O.; Huber K. V. M.; Hübner J.; Weinmann H.; Hartung I. V.; Gorjánácz M. Isoform-selective ATAD2 chemical probe with novel chemical structure and unusual mode of action. ACS Chem. Biol. 2017, 12, 2730–2736. 10.1021/acschembio.7b00708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siebeneicher H.; Cleve A.; Rehwinkel H.; Neuhaus R.; Heisler I.; Müller T.; Bauser M.; Buchmann B. Identification and optimization of the first highly selective GLUT1 inhibitor BAY-876. ChemMedChem. 2016, 11, 2261–2271. 10.1002/cmdc.201600276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahm F.; Viklund J.; Trésaugues L.; Ellermann M.; Giese A.; Ericsson U.; Forsblom R.; Ginman T.; Günther J.; Hallberg K.; Lindström J.; Persson L. B.; Silvander C.; Talagas A.; Díaz-Sáez L.; Fedorov O.; Huber K. V. M.; Panagakou I.; Siejka P.; Gorjánácz M.; Bauser M.; Andersson M. Creation of a novel class of potent and selective MutT homologue 1 (MTH1) inhibitors using fragment-based screening and structure-based drug design. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 61, 2533–2551. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.7b01884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider H.; Szabo E.; Machado R. A. C.; Broggini-Tenzer A.; Walter A.; Lobell M.; Heldmann D.; Süssmeier F.; Grünewald S.; Weller M. Novel TIE-2 inhibitor BAY-826 displays in vivo efficacy in experimental syngeneic murine glioma models. J. Neurochem. 2017, 140, 170–182. 10.1111/jnc.13877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen D.; Lemos C.; Wortmann L.; Eis K.; Holton S. J.; Boemer U.; Moosmayer D.; Eberspaecher U.; Weiske J.; Lechner C.; Prechtl S.; Suelzle D.; Siegel F.; Prinz F.; Lesche R.; Nicke B.; Nowak-Reppel K.; Himmel H.; Mumberg D.; von Nussbaum F.; Nising C. F.; Bauser M.; Haegebarth A. Discovery and characterization of the potent and highly selective (piperidin-4-yl)pyrido[3,2-d]pyrimidine based in vitro probe BAY-885 for the kinase ERK5. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 62, 928–940. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.8b01606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillig R. C.; Sautier B.; Schroeder J.; Moosmayer D.; Hilpmann A.; Stegmann C. M.; Werbeck N. D.; Briem H.; Boemer U.; Weiske J.; Badock V.; Mastouri J.; Petersen K.; Siemeister G.; Kahmann J. D.; Wegener D.; Böhnke N.; Eis K.; Graham K.; Wortmann L.; von Nussbaum F.; Bader B. Discovery of potent SOS1 inhibitors that block RAS activation via disruption of the RAS–SOS1 interaction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2019, 116, 2551–2560. 10.1073/pnas.1812963116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefranc J.; Schulze V. K.; Hillig R. C.; Briem H.; Prinz F.; Mengel A.; Heinrich T.; Balint J.; Rengachari S.; Irlbacher H.; Stöckigt D.; Bömer U.; Bader B.; Gradl S. N.; Nising C. F.; von Nussbaum F.; Mumberg D.; Panne D.; Wengner A. M. Discovery of BAY-985, a highly selective TBK1/IKKε inhibitor. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 63, 601–612. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.9b01460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.