Abstract

Objectives

This review aimed to determine the pooled prevalence of preoperative anxiety and its associated factors among patients undergoing surgery in low/middle-income countries (LMICs).

Methods

We searched PubMed, SCOPUS, CINAHL, Embase and PsychINFO to identify peer-reviewed studies on the prevalence and factors associated with preoperative anxiety among patients undergoing surgery using predefined eligibility criteria. Studies were pooled to estimate the prevalence of preoperative anxiety using a random-effect meta-analysis model. Heterogeneity was assessed using I² statistics. Funnel plot asymmetry and Egger’s regression tests were used to check for publication bias.

Result

Our search identified 2110 studies, of which 27 studies from 12 countries with 5575 participants were included in the final meta-analysis. Of the total 27 studies, 11 used the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory to screen anxiety, followed by the Amsterdam Preoperative Anxiety and Information scale, used by four studies. The pooled prevalence of preoperative anxiety among patients undergoing surgery in LMICs was 55.7% (95% CI 48.60 to 62.93). Our subgroup analysis found that a higher pooled prevalence of preoperative anxiety was found among female surgical patients (59.36%, 95% CI 48.16 to 70.52, I2=95.43, p<0.001) and studies conducted in Asia (62.59%, 95% CI 48.65 to 76.53, I2=97.48, p<0.001).

Conclusion

Our meta-analysis indicated that around one in two patients undergoing surgery in LMICs suffer from preoperative anxiety, which needs due attention. Routine screening of preoperative anxiety symptoms among patients scheduled for surgery is vital.

PROSPERO registration number

CRD42020161934.

Keywords: anxiety disorders, adult surgery, public health

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Conducting abroad literature search, independent screening, quality appraisal and data extraction by two investigators represent the main strength of the current review.

The absence of significant publication bias increases the reliability of our findings.

The significant heterogeneity among studies and the restriction applied to include studies published only in English language are the major limitations of the current review in generalising these findings to all low-income and middle-income countries.

Introduction

Anxiety is defined as a subjective state of emotional uneasiness, distress, apprehension or fearful concern associated with autonomic and somatic features and causes impaired functioning or activity.1 Anxiety can also be a normal emotional human reaction to circumstances of danger accompanied by physiological and psychological elements.1 2 Surgery is one of the standard medical procedures that could increase anxiety irrespective of the type of surgery.2 3 Surgery is a life-threatening procedure that causes the person to perceive himself under a direct physical restraint. Patients scheduled for surgery may experience fears and anxieties such as nervousness, fear of being unable to wake up from anaesthesia, fear of postoperative pain and fear of death.4 As a result, preoperative anxiety is becoming a significant mental health problem for many patients undergoing surgery.5 6

Different epidemiological studies revealed the varying magnitude of preoperative anxiety among patients undergoing surgery. For example, a global level systematic review and meta-analysis reported a 48% pooled prevalence of preoperative anxiety among patients undergoing surgery.7 A facility-based study conducted in Netherland found 27.9% and 20.3% of preoperative anxiety in patients undergoing hip and knee surgery, respectively.8 Epidemiological studies conducted in low/middle-income countries (LMICs) found that the prevalence of preoperative anxiety ranges from 47% to 70.3% in India,9 10 62% to 97% in Pakistan11–13 and 39.8% to 70% in Ethiopia.5 14–18

The magnitude of preoperative anxiety among patients undergoing surgery varies depending on the reasons and type of surgery, gender of the patient,12 patient interaction with medical staff, previous experience of surgical procedures and sensitivity to stressful circumstances.19 20 Also, factors such as fear of surgery, fear of anaesthesia, sociodemographic characteristics of the patient (age, educational status and partner status), types of surgery, fear of postoperative pain and fear of death were significant predictors of preoperative anxiety.16 17 21–25 However, the frequently mentioned major causes of preoperative anxiety were fear of the outcomes of surgery (29.3%), followed by fear of the progress after surgery (19.5%) and complications after surgery (11.4%).26 Furthermore, evidence also indicated that in many LMICs, the potential effect of scarce resources at health facilities, weak health systems and culture of a given community could play a paramount role in the increased rates of preoperative anxiety among surgical patients. For example, studies demonstrated that waiting for a longer duration for surgery,27 28 inadequate information about the procedure, disrespect by the clinician, lacking empathy29 and receiving less inpatient care28 could increase the risk of preoperative anxiety. Globally, the surgery rate ranges from 295 operations per 100 000 population in Ethiopia to 23 369 per 100 000 in Hungary, indicating a considerable difference in surgical service provision between low-income countries (LIC) and high-income countries (HIC) despite a growing unmet need.30 Despite the small number of surgical service in LMICs, it is compounded by the burden of managing postoperative complications such as delayed complications which mainly caused by inadequate inpatient care and low rates of follow-up service.31

Increased preoperative anxiety levels may be a reason for patients to decline planned surgical procedures.32 33 High levels of preoperative anxiety negatively affect the surgical operation and contribute to adverse surgical outcomes.34 35 Literature showed that preoperative anxiety might cause slow, complicated and painful postoperative recovery.35–37 Severe levels of anxiety before the surgical procedure have resulted in autonomic disturbances such as increased heart rate, raised blood pressure and arrhythmias,38 and affecting the outcomes of surgical procedures.39 Before the surgical procedure, patients who developed anxiety were found to require higher doses of anaesthetic medications, had a higher level of postoperative pain, increased consumption of analgesic drugs, increased morbidity, prolonged recovery and hospital stay.40–42 Appropriate management of anxiety by clinicians may provide a better preoperative assessment, less pharmacological premedication, smoother induction and maybe even better outcome.43

Based on the above evidence there was a substantial difference in the reported prevalence of preoperative anxiety among patients undergoing surgery across studies. Also, there is no previously conducted systematic reviews and meta-analysis on the topic of interest, particularly in LMICs. Furthermore, identifying the significant correlates of preoperative anxiety is vital to reduce the burden or prevent the onset and subsequent consequences. Therefore, this review aimed to examine the prevalence and thematically quantify and present factors associated with preoperative anxiety among patients undergoing surgery in LMICs and formulate recommendations for future healthcare services in the area.

Methods

Search strategy

A systemic review and meta-analysis was conducted using studies that examined the prevalence and factors associated with preoperative anxiety among patients undergoing surgery in LMICs. The strategy for literature search, selection of studies, data extraction and reporting of results for the current review was designed following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines44 (online supplemental file 1).

bmjopen-2021-058187supp001.pdf (189.7KB, pdf)

Five electronic databases (PubMed, SCOPUS, CINAHIL, Embase and PsychINFO) were systematically searched to identify studies that report the prevalence of preoperative anxiety among patients undergoing surgery in LMICs. Searching in PubMed was performed using the following terms: ((Prevalence OR Magnitude OR Epidemiology OR Incidence OR Estimates OR Burden OR Associated factors OR Determinants OR Correlates OR Predictors) AND ((Preoperative Anxiety OR Anxiety OR Anxiety symptoms OR Anxiety disorder OR General Anxiety disorder) AND (Surgical patients OR patients undergoing surgery OR surgery)). Database-specific subject headings associated with the above terms were used to screen studies indexed in SCOPUS, CINAHIL, Embase and PsychINFO databases. Besides, we observed the reference lists of published studies to identify potential other relevant articles for this review. The whole search strategy of our review is presented in online supplemental file 2.

bmjopen-2021-058187supp002.pdf (197KB, pdf)

Eligibility criteria

In the current review, we have included observational studies conducted on determining the prevalence and factors associated with preoperative anxiety among patients undergoing surgery in LMICs, and written in English language. Eligible studies included for this review had to fulfil the following criteria: first, the type of study has to be observational (cross-sectional, nested case–control, cohort studies or follow-up studies). Second, the study participants were patients (age ≥18 years) who have a schedule to undergo surgical procedures under anaesthesia, regardless of their sex. Third, measurement of anxiety was done using standard diagnostic criteria or a validated screening tools. Fourth, the studies should be from a LMIC. World Bank Atlas classified countries as low-income and middle-income for those with the Gross National Income per capita of ≤$1025 and between $1026 and $12 375, respectively (https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GNP.PCAP.CD).

Studies that reported pooled preoperative anxiety, had a poor quality score on the Newcastle Ottawa Scale (NOS), duplicate studies, conference proceedings, commentaries, reports, short communications and letters to editors were excluded. Then full-text articles were independently checked for their eligibility by two investigators (AB and NM). Disagreements were resolved by discussing with a third author (BD) for the final selection of studies.

Data extraction and study quality assessment

Data were extracted using a specific form designed to extract data that authors developed. The data extraction form included the following information: name of the author, year of publication, country, study design, sample size, type of surgery and the number of positive cases for preoperative anxiety, prevalence of preoperative anxiety and significant factors associated with preoperative anxiety. AB conducted the primary data extraction, and then NM assessed the extracted data independently. Any disagreements and discrepancies were resolved through discussion with the third author BD.

The methodological qualities of each included article were assessed by using a modified version of the NOS.45 The methodological quality and eligibility of the identified articles were independently evaluated by two reviewers (AB and NM), and disagreements among reviewers were resolved through discussion with the third Author (BD). The summary of the agreed level of bias and level of agreement between independent evaluators of studies is mentioned in online supplemental file 3. Finally, studies with a scale of ≥5 out of 10 were included in the current review.

bmjopen-2021-058187supp003.pdf (170.1KB, pdf)

Data analysis

For the first objective, estimating the pooled prevalence of preoperative anxiety, the prevalence report extracted from all the included primary studies were meta-analysed. For the second objective, identifying the significant factors associated with preoperative anxiety, reports of measures of associations (OR, r, β or RR) were presented using narrative synthesis. The narrative synthesis was conducted per the approaches indicated on the Conduct of Narrative Synthesis in Systematic Reviews.46 While interpreting the association between significant factors and preoperative anxiety, adjusted estimates were the first choice. However, for studies that missed reporting adjusted estimates, crude estimates were considered.

We have examined publication bias by visual inspection of a funnel and conducting Egger’s regression tests.47 48 A p value <0.05 was used to declare the statistical significance of publication bias. Studies were pooled to estimate pooled prevalence and 95% CI using a random-effect model.49 We have assessed heterogeneity using Cochran’s Q and the I² statistics.50 I2 statistics is used to quantify the percentage of the total variation in the study estimate due to heterogeneity. I2 values of 25, 50% and 75% were considered to represent low, medium and high heterogeneity, respectively.51 Due to significant heterogeneity across studies, we conducted a subgroup analysis using moderators such as methodological quality of studies, country, gender, anxiety assessment tool, economic level of a country and region where a country located. Also, sensitivity analysis was conducted to evaluate the presence of outlier estimates of preoperative anxiety. All the extracted data were analysed using STATA V.16.

Patient and public involvement

No patient or public involved in the current review.

Results

Identification of studies

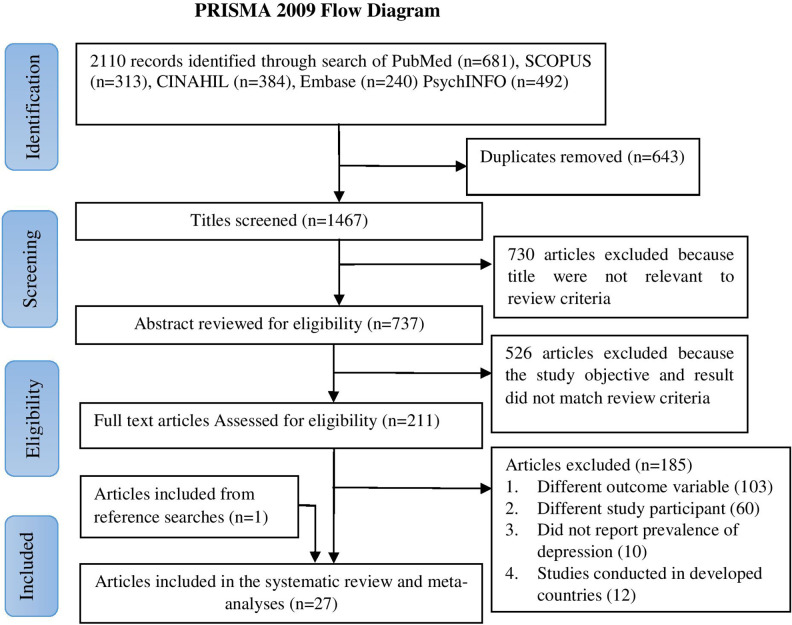

We have identified a total of 3110 studies from five databases in our initial electronic searching. After removing duplicates, reviewing titles and abstracts, 211 studies were considered eligible for full-text review. After excluding 185 articles in full-text review and adding 1 article that we get through reference searching, 27 studies were included in this systematic review and meta-analysis (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow chart of the study identification process for systematic reviews and meta-analyses.

Characteristics of included studies

Of the total 27 studies (5575 population), all (100%) studies employed cross-sectional study design, and 9 (81.2%) studies published in the past 5 years.14–18 38 52–54 Also, six studies were conducted in Ethiopia,5 14–18 five studies were from Brazil55–59 and three studies were from each of the following countries: Nigeria,38 54 60 Pakistan11 12 61 and India.61–63 The sample size of the included studies ranges from 30 in Nigeria54 to 591 in Brazil.58 The prevalence of preoperative anxiety ranges from 34% in Nigeria60 to 87.5% in India.62 Of the 27 included studies, 16 (59.2%) were from middle-income countries, whereas 11 (40.8%) were from LICs. State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) is the most common tool used to screen anxiety (11 studies), followed by the Amsterdam Preoperative Anxiety and Information Scale (APAI) (4 studies) (table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of studies included in the current systematic review

| Author | Publication year | Country | Sample size | Study design | Type of surgery | Cases | Prevalence (%) | Anxiety measures (cut-off point) |

| Bedaso and Ayalew14 | 2019 | Ethiopia | 407 | Cross-sectional | All surgery | 191 | 47 | STAI (≥44/80) |

| Takele et al15 | 2019 | Ethiopia | 237 | Cross-sectional | All surgery | 132 | 56 | PITI-20 Item (≥16/60) |

| Woldegerima et al16 | 2018 | Ethiopia | 178 | Cross-sectional | All surgery | 106 | 60 | STAI (≥44/80) |

| Mulugeta et al17 | 2018 | Ethiopia | 353 | Cross-sectional | All surgery | 215 | 61 | STAI (>44/80) |

| Akinsulore et al38 | 2015 | Nigeria | 51 | Cross-sectional | All surgery | 26 | 51 | STAI (>44/80) |

| Nigussie et al5 | 2014 | Ethiopia | 239 | Cross-sectional | All surgery | 168 | 70.3 | STAI (≥44/80) |

| Ebirim and Tobin60 | 2010 | Nigeria | 125 | Cross-sectional | All surgery | 43 | 34 | VAS (≥45/100) |

| Srahbzu et al18 | 2018 | Ethiopia | 423 | Cross-sectional | Orthopaedic surgery | 168 | 39.8 | HADS-A (≥18) |

| Ryamukuru52 | 2017 | Rwanda | 151 | Cross-sectional | All surgery | 110 | 72.8 | PITI-20 Item (≥15/60) |

| Zammit et al53 | 2018 | Tunisia | 332 | Cross-sectional | All surgery | 224 | 67.5 | APAI score (>10) |

| Dagona54 | 2018 | Nigeria | 30 | Cross-sectional | All surgery | 16 | 53.3 | APAI-H (NA) |

| Matthias and Samarasekera64 | 2011 | Srilanka | 100 | Cross-sectional | Elective surgery | 77 | 77 | APAI score (≥11) |

| Carneiro et al55 | 2009 | Brazil | 96 | Cross-sectional | Cardiac surgery | 42 | 43.8 | HADS-A (≥9) |

| Ramesh et al63 | 2017 | India | 140 | Cross-sectional | Cardiac surgery | 118 | 84 | STAI (≥40/80) |

| Gonçalves et al56 | 2016 | Brazil | 106 | Cross-sectional | Cardiac surgery | 43 | 40.6 | BAI (NA) |

| Alves et al57 | 2007 | Brazil | 114 | Cross-sectional | Cosmetic surgery | 85 | 74.5 | STAI (>36/80) |

| Caumo et al58 | 2001 | Brazil | 591 | Cross-sectional | Elective surgery | 141 | 23.99 | STAI (≥39/80) |

| Jafar and Khan11 | 2009 | Pakistan | 300 | Cross-sectional | Elective surgery | 186 | 62 | STAI (NA) |

| Maheshwari and Ismail12 | 2015 | Pakistan | 154 | Cross-sectional | Elective CS | 112 | 72.7 | VAS (≥50) |

| Ali et al69 | 2013 | Turkey | 80 | Cross-sectional | Gall bladder surgery | 31 | 38.75 | BAI (>17/63) |

| Ya'akba and Vachkova71 | 2017 | Palestine | 320 | Cross-sectional | All surgery | 184 | 57.5 | APAI score (>11) |

| Tajgna and Krishna62 | 2018 | India | 160 | Cross-sectional | All surgery | 140 | 87.5 | DASS-21 (NA) |

| Xu et al72 | 2016 | China | 53 | Cross-sectional | Gastric cancer surgery | 11 | 20.75 | HADS-A (≥18) |

| Santos et al59 | 2014 | Brazil | 41 | Cross-sectional | Rectal surgery | 16 | 39 | BAI (≥10/63) |

| Khalili et al65 | 2019 | Iran | 231 | Cross-sectional | All surgery | 109 | 47.2 | STAI (≥40/80) |

| Kanwal et al61 | 2018 | Pakistan | 363 | Cross-sectional | All surgery | 228 | 62.8 | VAS (≥45/100) |

| Tajgna et al62 | 2017 | India | 200 | Cross-sectional | Emergency CS | 110 | 55 | STAI (≥40/80) |

APAI, Amsterdam Preoperative Anxiety and Information Scale; BAI, Beck Anxiety Inventory; CS, caesarean section; DASS-21, Depression Anxiety and Stress Scale; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; PITI, Preoperative Intrusive Thought Inventory; STAI, State-Trait Anxiety Inventory; VAS, Visual Analogue Scale.

Methodological quality of studies

We used the modified NOS45 to evaluate the methodological quality of the studies included in the current review. Among the 27 studies included in the present review, 16 studies were of high (NOS score ≥8) and 11 studies were of moderate methodological quality (NOS score 6–7) (online supplemental file 4).

bmjopen-2021-058187supp004.pdf (173.6KB, pdf)

Meta-analysis

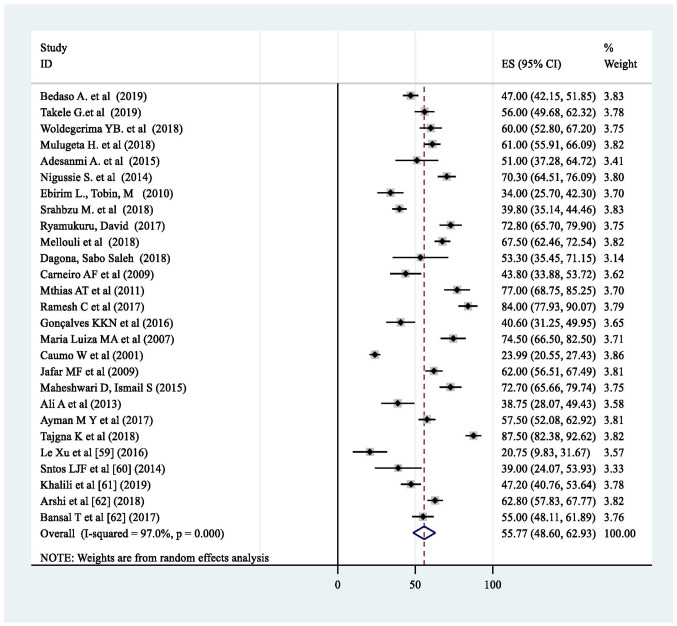

The pooled prevalence of preoperative anxiety among patients undergoing surgery within the LMICs included within this study was estimated to be 55.7% (95% CI 48.60 to 62.93) with considerable heterogeneity between studies (I2=97%; p<0.001). Consequently, a random-effects meta-analysis model was employed to estimate the overall pooled prevalence (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Forest plot showing the pooled prevalence of preoperative anxiety among patients undergoing surgery in low-income and middle-income countries. ES, effect size.

Further, to explore the possible sources of heterogeneity we employed a random-effect univariate meta-regression model considering the sample size, publication year and NOS quality score as moderators. However, none these continuous variables (ie, sample size (coefficient=−0.015, p=0.533), publication year (coefficient=0.984, p=0.202) and NOS quality score (coefficient=−2.65, p=0.412)) found to have significant association with heterogeneity.

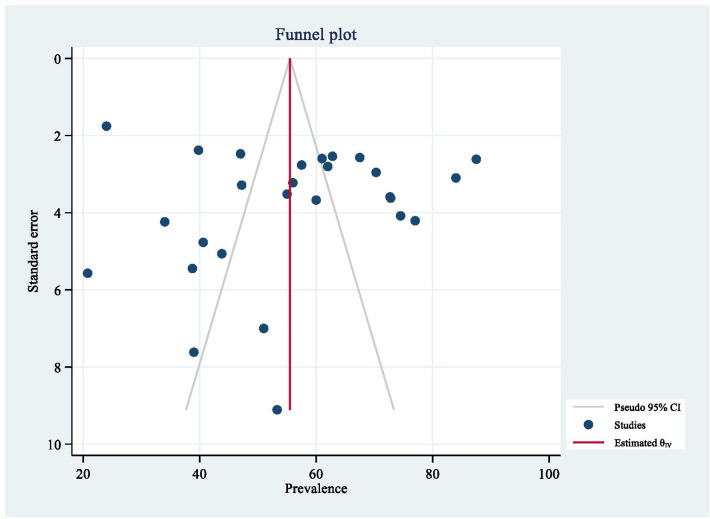

Publication bias

Inspection of the funnel plot looks symmetric and shows no significant publication bias (figure 3). Besides, eggers regression test suggested absence of publication bias (B=−2.79, SE=2.013, p=0.165).

Figure 3.

Funnel plot for testing publication bias (random effect model, N=27).

Sub-group and sensitivity analysis

Due to the reported high heterogeneity index among studies, a subgroup analysis was conducted using characteristics like country, type of anxiety tool used, quality of studies and economic level of a country. Among studies that assessed the prevalence of preoperative anxiety among surgical patients, the subgroup analysis based on the region where the studies conducted revealed that a higher pooled prevalence of preoperative anxiety was reported in a study conducted in Asia (62.59%, 95% CI 48.65 to 76.53, I2=97.48, p<0.001), followed by Africa (55.91%, 95% CI 48.37 to 63.44 I2=99.31, p<0.001) and Middle East (52.5%, 95% CI 42.41 to 62.59). Besides, a higher pooled prevalence of preoperative anxiety was reported in a study that used Depression Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS) (87.5%, 95% CI 82.37 to 92.62), followed by studies that used APAI tool as an anxiety assessment tool (64.9%, 95% CI 55.78 to 74.10, I2=83.4%, p<0.001).

To further explore the source of heterogeneity among studies included in the review, we have also conducted a subgroup analysis using the quality of studies as a moderator. The pooled prevalence of preoperative anxiety was higher in the studies with moderate methodological quality (57.2%) (95% CI 48.49 to 65.97, I2=94.2%, p<0.001) compared with those studies with high methodological quality (54.8%) (95% CI 44.28 to 65.28, I2=97.8, p<0.001). Furthermore, a pooled estimate of preoperative anxiety among female surgical patients (59.36%, 95% CI 48.16 to 70.52, I2=95.43, p<0.001) was higher than their male counterparts (45.95%, 95% CI 31.69 to 60.21, I2=96.67, p<0.001). However, a pooled estimate of preoperative anxiety in middle-income countries (55.7%) (95% CI 48.60 to 62.93, I2=98, p<0.001) was comparable to studies conducted in LICs (54.9%, 95% CI 47.69 to 62.17, I2=92.6, p<0.001) (table 2).

Table 2.

Subgroup analysis of the prevalence of preoperative anxiety among patients undergoing surgery by country, type of anxiety tool, quality of studies and economic level of a country

| Subgroup | Number of studies | Estimates | Heterogeneity across studies | ||

| Prevalence (%) | 95% CI | I2 (%) | P value | ||

| Country | |||||

| Ethiopia | 6 | 55.6 | 35.13 to 44.46 | 94.1 | <0.001 |

| Nigeria | 3 | 44.6 | 31.86 to 58.16 | 69.6 | 0.037 |

| Rwanda | 1 | 72.8 | 65.7 to 79.89 | – | – |

| Tunisia | 1 | 67.5 | 62.46 to 72.53 | – | – |

| Brazil | 5 | 44.4 | 23.76 to 64.95 | 97.1 | <0.001 |

| Srilanka | 1 | 77 | 68.75 to 85.25 | 96.6 | <0.001 |

| India | 3 | 75.6 | 56.72 to 94.49 | 69 | 0.040 |

| Pakistan | 3 | 65.4 | 59.4 to 71.39 | – | – |

| Turkey | 1 | 38.8 | 28.07 to 49.4 | – | – |

| Palestine | 1 | 57.5 | 52.08 to 62.9 | – | – |

| China | 1 | 20.6 | 9.83 to 31.67 | – | – |

| Iran | 1 | 47.2 | 40.76 to 53.63 | 97 | <0.001 |

| Anxiety tool used | |||||

| STAI | 11 | 57.8 | 45.80 to 69.78 | 97.9 | <0.001 |

| PITI | 2 | 64.3 | 47.85 to 80.78 | 91.7 | 0.001 |

| VAS | 3 | 56.6 | 37.16 to 76.17 | 96.1 | <0.001 |

| HADS-A | 3 | 35.3 | 23.77 to 46.90 | 82.6 | 0.003 |

| APAI | 4 | 64.9 | 55.78 to 74.10 | 83.4 | <0.001 |

| BAI | 3 | 39.6 | 33.29 to 46.02 | 0 | 0.964 |

| DASS | 1 | 87.5 | 82.37 to 92.62 | – | – |

| Quality of studies | |||||

| High | 16 | 54.8 | 44.28 to 65.28 | 97.8 | <0.001 |

| Moderate | 11 | 57.2 | 48.49 to 65.97 | 94.2 | <0.001 |

| Economy level of a country | |||||

| Low income | 11 | 54.9 | 47.69 to 62.17 | 92.6 | <0.001 |

| Middle income | 16 | 55.7 | 48.60 to 62.93 | 98 | <0.001 |

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 8 | 45.95 | 31.69 to 60.21 | 96.67 | <0.001 |

| Female | 9 | 59.36 | 48.16 to 70.52 | 95.43 | <0.001 |

| Region | |||||

| Africa | 11 | 55.91 | 48.37 to 63.44 | 99.31 | <0.001 |

| Asia | 9 | 62.59 | 48.65 to 76.53 | 97.48 | <0.001 |

| South America | 5 | 44.35 | 27.62 to 61.08 | 95.54 | <0.001 |

| Middle East | 2 | 52.50 | 42.41 to 62.59 | 82.63 | 0.02 |

APAI, Amsterdam Preoperative Anxiety and Information Scale; BAI, Beck Anxiety Inventory; DASS, Depression Anxiety and Stress Scale; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; PITI, Preoperative Intrusive Thought Inventory; STAI, State-Trait Anxiety Inventory; VAS, Visual Analogue Scale.

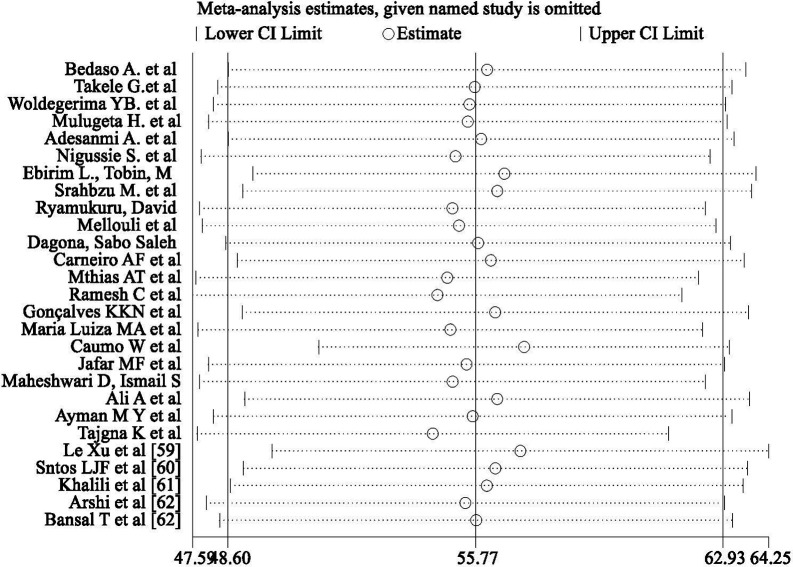

Moreover, we have conducted a leave-one-out sensitivity analysis to identify the influence of one study on the overall pooled estimate. The overall estimate of this study did not appear to be affected by the removal or addition of a single study at a time, suggesting the robustness of our pooled estimate. Thus, the pooled prevalence of preoperative anxiety ranges from 54.5% to 57.2% (figure 4).

Figure 4.

Sensitivity analysis for studies included in the meta-analysis.

Factors associated with preoperative anxiety among patients undergoing surgery

The results extracted from studies conducted on factors associated with preoperative anxiety among patients undergoing surgery are presented in online supplemental file 5. Associated factors that have been adjusted in the studies included in this review were inconsistent across studies conducted in LMICs.5 12 14–18 52 53 56 58 59 63–68

bmjopen-2021-058187supp005.pdf (221.3KB, pdf)

Of the total studies included in the review, 10 studies15 17 18 56 58 63–66 68 reported the increased odds of preoperative anxiety symptoms among female patients when compared with male patients. Similarly, being young age12 16 52 65 67 has significantly increased the odds of preoperative anxiety symptoms in patients waiting for scheduled surgery. Preoperative anxiety was significantly associated with fear of death, dependency, and disability.14 16

Further, patients who did not receive adequate preoperative information were more likely to have clinically significant preoperative anxiety levels compared with patients who did receive high-level information.5 12 15 17 53 65 Not surprisingly, low income appeared to increase the odds of developing preoperative anxiety symptoms in patients waiting for surgery.5 12 Likewise, having a family history of mental illness,45 history of cancer and smoking,49 lower educational attainment66 67 were found to be associated with preoperative anxiety symptoms in patients waiting for surgery.

Moreover, statistical adjustment for some other risk factors varied for respective studies included in this review. Factors such as getting low social support, fear of unexpected outcome of surgery,14 being non-partnered,5 urban residence, inadequate awareness of anaesthesia adverse effect,65 number of days of hospitalisation,69 having a chronic medical illness,18 gastrointestinal problems59 were found to have a significant positive correlation with preoperative anxiety after adjusting for other factors.

Discussion

This systematic review and meta-analysis synthesised the results of 27 primary studies that were conducted in LMICs to determine the pooled prevalence and factors associated with preoperative anxiety among 5575 surgical patients undergoing surgery.

The pooled prevalence of preoperative anxiety among patients undergoing surgery in LMICs was 55.7%. The pooled estimate in the current review was higher when compared with the pooled prevalence reported in a global level systematic review and meta-analysis that included 14 652 study participants (48%).7 Likewise, the pooled estimate of our review was higher than the estimates from different epidemiological studies conducted in HICs such as the Netherlands reported that 27.9% and 20.3% of patients undergoing hip and knee surgery, respectively, experienced anxiety symptoms before the actual surgery.8 The variation in the demographic characteristics of participants and may partly explain the observed difference in the pooled estimates. Furthermore, risk factors such as genetic make-up of individuals, access to information regarding their surgical procedure, quality and availability of service in each health facility, sampling methods, and tools used to screen anxiety may contribute to the observed difference.

Surprisingly, the available epidemiological evidence was virtually unchanged when the origin of the primary studies included in this review considered as a moderator. For example, the pooled prevalence of preoperative anxiety was 77% in Sri Lanka, 75.6% in India and 72.8% in Rwanda. Although evidence suggests that an individual cultural background could potentially affect the experience of anxiety symptoms, the variability of the origin of primary studies appeared to play a negligible role in the pooled estimate of this study.

The subgroup analysis using the tools used to estimate the prevalence of preoperative anxiety showed a slight variation in the prevalence of preoperative anxiety among patients undergoing surgery. Most notably, the prevalence of preoperative anxiety among patients undergoing surgery was slightly higher in the studies that have used DASS to ascertain preoperative anxiety in patients when compared with APAI. The discrepancy may be due to variability in the psychometric properties of those measures.

Our review found that the prevalence of preoperative anxiety was higher among female surgical patients compared with their male counterparts. Also, of the studies included in the current systematic review and meta-analysis, 10 studies reported that being female increased the odds of developing preoperative anxiety among surgical patients.15 17 18 56 58 63–66 68 This might be because of women’s experience of some specific forms of mental health problems like premenstrual dysphoric disorder, postpartum depression and postmenopausal mental illness, which are linked with changes in ovarian hormones that may contribute to the observed difference in risk of developing preoperative anxiety among female patients.70

Early screening and targeted intervention of preoperative anxiety among patients undergoing surgery are recommended for future action. Further studies should be conducted to examine the possible reasons for a substantially higher burden of preoperative anxiety among patients undergoing surgery. Moreover, interventional and randomised controlled trials (RCTs) are recommended for a specific group of surgical patients.

It is worth noting the following potential limitations of our review in generalising the findings. First, there is significant heterogeneity among studies included in the current review. Second, the restriction to include studies published only in English language could introduce possible selection bias and limit the generalisability to all LMICs.

Conclusion

Our study indicated that around one in two patients undergoing surgery in LMICs suffer from preoperative anxiety, which needs due attention. Therefore, routine screening of preoperative anxiety among patients scheduled for surgery is vital. In addition, providing preoperative education on the effect of anaesthesia, surgical procedure and possible postoperative pain management options is highly warranted. Due to the significant heterogeneity across the studies, future studies should examine preoperative anxiety for a specific group of surgical patients by stratifying the possible associated factors. Moreover, since all the included studies employed a cross-sectional study design, the findings did not show a temporal relationship between preoperative anxiety and its associated factors. Therefore, future longitudinal studies and RCTs are recommended.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors contributed to the design of this review. AB performed the search, quality appraisal, data extraction, analyses and writing the draft manuscript. NM participated in the searching, quality appraisal, data extraction and revising of the draft manuscript. BD participated to the consensus, analyses and revising the draft manuscript. All authors accepts official responsibility for the overall integrity of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript for publication.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

This study does not involve human participants.

References

- 1.American Psychiatric Association . American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-IV, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bellani ML. Psychological aspects in day-case surgery. Int J Surg 2008;6 Suppl 1:S44–6. 10.1016/j.ijsu.2008.12.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bailey L. Strategies for decreasing patient anxiety in the perioperative setting. Aorn J 2010;92:445–60. 10.1016/j.aorn.2010.04.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Akıncı SB, Sarıcaoglu F, Dal D, et al. Preoperative anesthesic evaluation. Hacettepe Med J 2003;36:91–7. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nigussie S, Belachew T, Wolancho W. Predictors of preoperative anxiety among surgical patients in Jimma university specialized teaching Hospital, South Western Ethiopia. BMC Surg 2014;14:67. 10.1186/1471-2482-14-67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McCleane GJ, Cooper R. The nature of pre-operative anxiety. Anaesthesia 1990;45:153–5. 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1990.tb14285.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abate SM, Chekol YA, Basu B. Global prevalence and determinants of preoperative anxiety among surgical patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Surg Open 2020;25:6–16. 10.1016/j.ijso.2020.05.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Duivenvoorden T, Vissers MM, Verhaar JAN, et al. Anxiety and depressive symptoms before and after total hip and knee arthroplasty: a prospective multicentre study. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2013;21:1834–40. 10.1016/j.joca.2013.08.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bansal T, Joon A. A comparative study to assess preoperative anxiety in obstetric patients undergoing elective or emergency cesarean section. Anaesth, Pain & Intensive Care 2019;21:25–30. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vadhanan P, Tripaty DK, Balakrishnan K. Pre-Operative anxiety amongst patients in a tertiary care hospital in India- a prevalence study. J Soc Anesth Nep 2017;4:5–10. 10.3126/jsan.v4i1.17377 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jafar MF, Khan FA. Frequency of preoperative anxiety in Pakistani surgical patients. J Pak Med Assoc 2009;59:359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maheshwari D, Ismail S. Preoperative anxiety in patients selecting either general or regional anesthesia for elective cesarean section. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol 2015;31:196. 10.4103/0970-9185.155148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zeb A, Hammad AM, Baig R, et al. Pre-Operative anxiety in patients at tertiary care Hospital, Peshawar. Pakistan J Clin Trials Res 2019;2:76–80. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bedaso A, Ayalew M. Preoperative anxiety among adult patients undergoing elective surgery: a prospective survey at a general Hospital in Ethiopia. Patient Saf Surg 2019;13:18. 10.1186/s13037-019-0198-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Takele G, Ayelegne D, Boru B. Preoperative anxiety and its associated factors among patients waiting elective surgery in St. Luke’s Catholic Hospital and Nursing College, Woliso, Oromia, Ethiopia, 2018. Emerg Med Crit Care 2019;4:21–37. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Woldegerima Y, Fitwi G, Yimer H. Prevalence and factors associated with preoperative anxiety among elective surgical patients at University of Gondar Hospital. Gondar, Northwest Ethiopia, 2017. A cross-sectional study. Int J Surg Open 2018;10:21–9. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mulugeta H, Ayana M, Sintayehu M, et al. Preoperative anxiety and associated factors among adult surgical patients in Debre Markos and Felege Hiwot referral hospitals, Northwest Ethiopia. BMC Anesthesiol 2018;18:155. 10.1186/s12871-018-0619-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Srahbzu M, Yigizaw N, Fanta T, et al. Prevalence of depression and anxiety and associated factors among patients visiting orthopedic outpatient clinic at Tikur Anbessa specialized Hospital, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2017. J Psychiatry;21:2. 10.4172/2378-5756.1000450 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Robertson A, Khan R, Fick D, et al. The effect of virtual reality in reducing preoperative anxiety in patients prior to arthroscopic knee surgery: a randomised controlled trial. 2017 IEEE 5th International Conference on Serious Games and Applications for Health (SeGAH), IEEE, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Duggan M, Dowd N, O'Mara D, O’Mara D, et al. Benzodiazepine premedication may attenuate the stress response in daycase anesthesia: a pilot study. Can J Anaesth 2002;49:932–5. 10.1007/BF03016877 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sigdel S. Perioperative anxiety: a short review. Glob Anaesth Perioper Med 2015;1:10.15761. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bradt J, Dileo C, Potvin N. Music for stress and anxiety reduction in coronary heart disease patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013:CD006577. 10.1002/14651858.CD006577.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ghimire R, Poudel P. Preoperative anxiety and its determinants among patients scheduled for major surgery: a hospital based study. J Anesthesiol 2018;6:57–60. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chow CHT, Van Lieshout RJ, Schmidt LA, et al. Systematic review: audiovisual interventions for reducing preoperative anxiety in children undergoing elective surgery. J Pediatr Psychol 2016;41:182–203. 10.1093/jpepsy/jsv094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hellstadius Y, Lagergren J, Zylstra J, et al. Prevalence and predictors of anxiety and depression among esophageal cancer patients prior to surgery. Dis Esophagus 2016;29:1128–34. 10.1111/dote.12437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kuzminskaitė V, Kaklauskaitė J, Petkevičiūtė J. Incidence and features of preoperative anxiety in patients undergoing elective non-cardiac surgery. Acta Med Litu 2019;26:93. 10.6001/actamedica.v26i1.3961 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Masood Z, Haider J, Jawaid M. Preoperative anxiety in female patients: the issue needs to be addressed. Khyber Med Univ J 2009;1:38–41. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gilmartin J, Wright K. Day surgery: patients' felt abandoned during the preoperative wait. J Clin Nurs 2008;17:2418–25. 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2008.02374.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jangland E, Gunningberg L, Carlsson M. Patients' and relatives' complaints about encounters and communication in health care: evidence for quality improvement. Patient Educ Couns 2009;75:199–204. 10.1016/j.pec.2008.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weiser TG, Regenbogen SE, Thompson KD, et al. An estimation of the global volume of surgery: a modelling strategy based on available data. Lancet 2008;372:139–44. 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60878-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Limburg H, Foster A, Gilbert C, et al. Routine monitoring of visual outcome of cataract surgery. Part 2: results from eight study centres. Br J Ophthalmol 2005;89:50–2. 10.1136/bjo.2004.045369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guo P, East L, Arthur A. A preoperative education intervention to reduce anxiety and improve recovery among Chinese cardiac patients: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Nurs Stud 2012;49:129–37. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2011.08.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sharma NS, Ooi J-L, Figueira EC, et al. Patient perceptions of second eye clear corneal cataract surgery using assisted topical anaesthesia. Eye 2008;22:547–50. 10.1038/sj.eye.6702711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fink C, Diener MK, Bruckner T, et al. Impact of preoperative patient education on prevention of postoperative complications after major visceral surgery: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial (PEDUCAT trial). Trials 2013;14:271. 10.1186/1745-6215-14-271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Upton D, Hender C, Solowiej K. Mood disorders in patients with acute and chronic wounds: a health professional perspective. J Wound Care 2012;21:42–8. 10.12968/jowc.2012.21.1.42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gouin J-P, Kiecolt-Glaser JK. The impact of psychological stress on wound healing: methods and mechanisms. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am 2011;31:81–93. 10.1016/j.iac.2010.09.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Page GG, Marucha PT, et al. Psychological influences on surgical recovery. perspectives from psychoneuroimmunology. Am Psychol 1998;53:1209. 10.1037//0003-066x.53.11.1209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Akinsulore A, Owojuyigbe AM, Faponle AF, et al. Assessment of preoperative and postoperative anxiety among elective major surgery patients in a tertiary hospital in Nigeria. Middle East J Anaesthesiol 2015;23:235–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yilmaz M, Sezer H, Gürler H, et al. Predictors of preoperative anxiety in surgical inpatients. J Clin Nurs 2012;21:956–64. 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2011.03799.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Maranets I, Kain ZN. Preoperative anxiety and intraoperative anesthetic requirements. Anesth Analg 1999;89:1346. 10.1097/00000539-199912000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Osborn TM, Sandler NA. The effects of preoperative anxiety on intravenous sedation. Anesth Prog 2004;51:46. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Balasubramaniyan N, Rayapati DK, Puttiah RH, et al. Evaluation of Anxiety Induced Cardiovascular Response in known Hypertensive Patients Undergoing Exodontia - A Prospective Study. J Clin Diagn Res 2016;10:ZC123. 10.7860/JCDR/2016/19685.8391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kindler CH, Harms C, Amsler F, et al. The visual analog scale allows effective measurement of preoperative anxiety and detection of patients' anesthetic concerns. Anesth Analg 2000;90:706–12. 10.1097/00000539-200003000-00036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev 2015;4:1. 10.1186/2046-4053-4-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stang A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol 2010;25:603–5. 10.1007/s10654-010-9491-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Popay J, Roberts H, Sowden A. Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews. A product from the ESRC methods programme version. 1, 2006: b92. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, et al. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 1997;315:629–34. 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ioannidis JPA. Interpretation of tests of heterogeneity and bias in meta-analysis. J Eval Clin Pract 2008;14:951–7. 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2008.00986.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JPT, et al. A basic introduction to fixed-effect and random-effects models for meta-analysis. Res Synth Methods 2010;1:97–111. 10.1002/jrsm.12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Higgins JPT, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med 2002;21:1539–58. 10.1002/sim.1186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, et al. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003;327:557. 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ryamukuru D. Assessment of preoperative anxiety for patients awaiting surgery at UTHK. University of Rwanda, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zammit N, Menel M, Rania F. Preoperative anxiety in the tertiary care hospitals of Sousse, Tunisia: prevalence and predictors. SOJ Surg 2018;5:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dagona SS. Prevalence of preoperative anxiety among Hausa patients undergoing elective surgery-a descriptive study. Adv Soc Sci Res J 2018;5. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Carneiro AF, Mathias LAST, Rassi Júnior A, et al. [Evaluation of preoperative anxiety and depression in patients undergoing invasive cardiac procedures]. Rev Bras Anestesiol 2009;59:431–8. 10.1590/s0034-70942009000400005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gonçalves KKN, Silva JIda, Gomes ET, et al. Anxiety in the preoperative period of heart surgery. Rev Bras Enferm 2016;69:397–403. 10.1590/0034-7167.2016690225i [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Alves MLM, Pimentel AJ, Guaratini AA, et al. [Preoperative anxiety in surgeries of the breast: a comparative study between patients with suspected breast cancer and that undergoing cosmetic surgery.]. Rev Bras Anestesiol 2007;57:147–56. 10.1590/s0034-70942007000200003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Caumo W, Schmidt AP, Schneider CN, et al. Risk factors for preoperative anxiety in adults. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2001;45:298–307. 10.1034/j.1399-6576.2001.045003298.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Santos LJF, Garcia JBdosS, Pacheco JS, et al. Quality of life, pain, anxiety and depression in patients surgically treated with cancer of rectum. Arq Bras Cir Dig 2014;27:96–100. 10.1590/s0102-67202014000200003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ebirim L, Tobin M. Factors responsible for pre-operative anxiety in elective surgical patients at a university teaching hospital: a pilot study. Int J Anesthesiol 2010;29:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kanwal A, Asghar A, Ashraf A. Prevalence of preoperative anxiety and its causes among surgical patients presenting in Rawalpindi medical university and allied hospitals, Rawalpindi. J Rawalpindi Med Coll 2018;22:64–7. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tajgna K, Krishna DPV, eds. Assessment of Preoperative Depression, Anxiety and Stress for Patients Awaiting Surgery in a Tertiary Care Hospital, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ramesh C, Nayak BS, Pai VB, et al. Pre-Operative anxiety in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass graft surgery – a cross-sectional study. Int J Afr Nurs Sci 2017;7:31–6. 10.1016/j.ijans.2017.06.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Matthias AT, Samarasekera DN. Preoperative anxiety in surgical patients - experience of a single unit. Acta Anaesthesiol Taiwan 2012;50:3–6. 10.1016/j.aat.2012.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Khalili N, Karvandian K, Eftekhar Ardebili H, et al. Predictive factors of preoperative anxiety in the anesthesia clinic: a survey of 231 surgical candidates. AACC 2019. 10.18502/aacc.v5i4.1452 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Erkilic E, Kesimci E, Soykut C, et al. Factors associated with preoperative anxiety levels of Turkish surgical patients: from a single center in Ankara. Patient Prefer Adherence 2017;11:291. 10.2147/PPA.S127342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ocalan R, Akin C, Disli ZK, et al. Preoperative anxiety and postoperative pain in patients undergoing septoplasty. B-ENT 2015;11:19–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Fathi M, Alavi SM, Joudi M, et al. Preoperative anxiety in candidates for heart surgery. Iran J Psychiatry Behav Sci 2014;8:90. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ali A, Altun D, Oguz BH, et al. The effect of preoperative anxiety on postoperative analgesia and anesthesia recovery in patients undergoing laparascopic cholecystectomy. J Anesth 2014;28:222–7. 10.1007/s00540-013-1712-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Albert PR. Why is depression more prevalent in women? J Psychiatry Neurosci 2015;40:219. 10.1503/jpn.150205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ya'akba AM, vachkova E N. Prevalence of preoperative anxiety and its contributing risk factors in adult patients undergoing elective surgery. An-Najah National University, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Xu L, Pan Q, Lin R. Prevalence rate and influencing factors of preoperative anxiety and depression in gastric cancer patients in China: preliminary study. J Int Med Res 2016;44:377–88. 10.1177/0300060515616722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2021-058187supp001.pdf (189.7KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2021-058187supp002.pdf (197KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2021-058187supp003.pdf (170.1KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2021-058187supp004.pdf (173.6KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2021-058187supp005.pdf (221.3KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.