Liu et al. demonstrate that the PERK-triggered HSPC preconditioning in the spleen is essential for their myeloid descendant cells to become immune suppressors in response to subsequent tumor microenvironmental stimulation. A spleen-targeted PERK blockade could be an effective strategy of immunotherapy.

Abstract

The spleen is an important site of hematopoietic stem/progenitor cell (HSPC) preconditioning and tumor-promoting myeloid cell generation in cancer, but the regulatory mechanism remains unclear. Here, we found that PKR-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase (PERK) mediated HSPC reprogramming into committed MDSC precursors in the spleen via PERK–ATF4–C/EBPβ signaling. Pharmacological and genetic inhibition of this pathway in murine and human HSPCs prevented their myeloid descendant cells from becoming MDSCs even with subsequent exposure to tumor microenvironment (TME) factors. In mice, the selective delivery of PERK antagonists to the spleen was not only sufficient but more effective than the tumor-targeted strategy in preventing MDSC activation in the tumor, leading to profound TME reshaping and tumor regression. Clinically, HSPCs in the spleen of cancer patients exhibit increased PERK signaling correlated with enhanced myelopoiesis. Our findings indicate that PERK-mediated HSPC preconditioning plays a crucial role in MDSC generation, suggesting novel spleen-targeting therapeutic opportunities for restraining the tumor-promoting myeloid response at its source.

Introduction

Myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) are major components in the tumor microenvironment (TME; Bronte et al., 2016; Consonni et al., 2019; Veglia et al., 2021). These cells represent a heterogeneous group of monocytic (M-MDSCs) and polymorphonuclear (PMN-MDSCs) precursors that universally regulate antitumor immunity and promote disease progression in cancers (Cui et al., 2013; Mantovani et al., 2021; Olingy et al., 2019; Strauss et al., 2021). Reprogramming immunosuppressive MDSCs toward cells with antitumor function is an emerging notion that has attracted intense investigation (Alicea-Torres et al., 2021; Bauer et al., 2018; Fujita et al., 2011; Tzetzo and Abrams, 2021; Veglia et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2019). However, the pursuit of this goal is hampered by the limited understanding of the MDSC ontogeny and the precise regulatory mechanism (Bronte and Pittet, 2013; Mohamed et al., 2018; Veglia et al., 2021). In particular, whether and how tumors distort the host’s hematopoietic activities to reroute systemic myelopoiesis toward MDSC generation remains elusive.

MDSCs are short-lived in tissues, but because of their continuous replenishment from hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs), they exert long-lasting effects on tumor progression (Veglia et al., 2021; Yvan-Charvet and Ng, 2019). Tumors can induce “emergency hematopoiesis,” generally characterized by preferential myeloid differentiation in the bone marrow (BM) and extramedullary organs (Bronte and Pittet, 2013; Casbon et al., 2015; Hou et al., 2021; Wu et al., 2014). The spleen is a major site of extramedullary hematopoiesis in cancer, which exhibits a dramatic expansion of myeloid-biased HSPCs in both mice and patients with different types of solid tumors (Cortez-Retamozo et al., 2012; Lewis et al., 2019; Steenbrugge et al., 2021; Wu et al., 2020a). We recently found that the cancer-associated splenic HSPC population compositionally and functionally differed from its BM counterpart and that splenic myelopoiesis was skewed toward tumor-promoting myeloid cell generation (Wu et al., 2018). In mouse models and patients with cancer presenting signs of high-level myelopoiesis, splenectomy partially restrains the tumor-promoting myeloid cell response, restores adaptive immune responses, and limits tumor progression and metastasis (Cortez-Retamozo et al., 2012; Motomura et al., 2013; Ugel et al., 2012; Wu et al., 2018), but clinical data have also revealed the rational benefits of preserving the normal functions of the spleen (Kristinsson et al., 2014; Steenbrugge et al., 2021). The development of a more selective strategy to therapeutically target splenic myelopoiesis may provide novel opportunities for modulating tumor immunity with enhanced efficiency and precision.

The ER stress response, which induces the unfolded protein response (UPR) and the activation of PKR-like ER kinase (PERK, encoded by Eif2ak3), was recently demonstrated to be crucial for the immunosuppressive polarization of MDSCs in the TME (Mohamed et al., 2020). The genetic ablation of PERK functionally reprogrammed MDSCs to allow CD8+ T cell responses, thereby reshaping the TME against cancer. However, since several feature myeloid genes, including Lyz2 and Csf1r, are expressed by both early progenitors and differentiated cells of the myeloid lineage (Han et al., 2016; Izzo et al., 2020; Mossadegh-Keller et al., 2013), where and how PERK directs tumor-associated myelopoiesis cannot be fully determined using current conditioned genetic manipulations. Thus, its precise role and mechanism remains to be better defined.

Here, we found that delivering small-molecule PERK antagonists to the spleen had a stronger and more constant antitumor effect than inhibiting PERK signaling in the tumor. Consistently, systemic PERK blockade had a limited antitumor effect on splenectomized mice. Lineage-tracing experiments revealed that the suppressive function of MDSCs in the tumor relied on the PERK-dependent HSPC reprogramming in the spleen. A robust ER stress response and subsequent signaling through PERK–activating transcription factor 4 (ATF4)–CCAAT-enhancer binding protein β (C/EBPβ) reprogrammed murine and human HSPCs to commit to MDSC differentiation. Our results indicate that PERK-mediated HSPC preconditioning is a previously unappreciated early event and a crucial regulatory mechanism of MDSC generation. Targeting this signaling in the spleen may provide novel therapeutic opportunities to selectively redirect tumor-promoting myeloid responses at the source.

Results

Spleen-targeted PERK blockade suppresses tumor MDSC activity and reshapes the TME

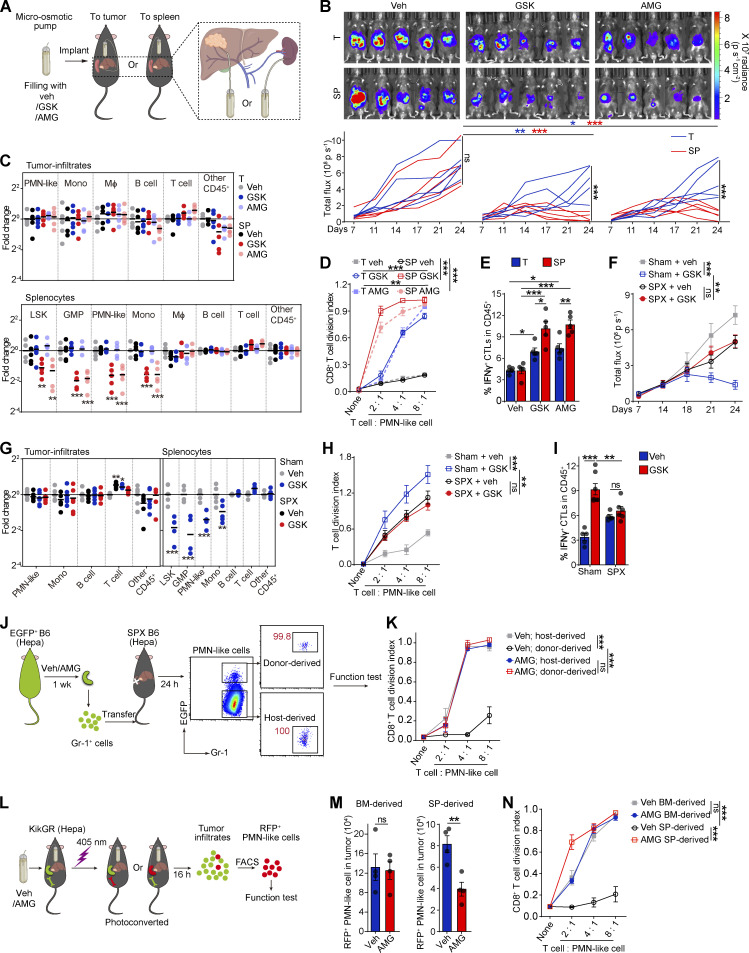

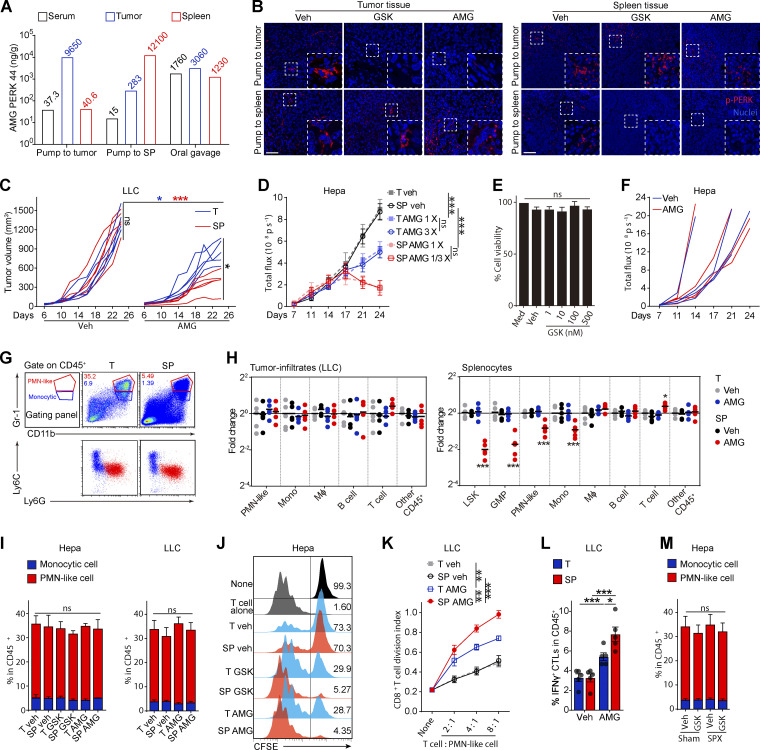

PERK inhibitors can hamper tumor MDSC activity but exhibit pancreatic toxicity (Mohamed et al., 2020; Yu et al., 2015). We investigated whether the direct delivery of PERK inhibitors (PERK-i) to the tumor could more efficiently and safely achieve therapeutic efficacy. To test this hypothesis, low doses of GSK2606414 (GSK; 42 µg/d) or AMG PERK 44 (AMG; 21 µg/d), which are two small-molecule PERK-i, were delivered to mouse orthotopic Hepa1-6 hepatomas (Hepa) at a speed of 0.25 μl/h using a micro-osmotic pump system (Fig. 1 A). For comparison, the drugs were alternatively delivered to the spleen, where MDSCs showed low to undetectable PERK expression (Mohamed et al., 2020). Micro-osmotic pumps successfully delivered the compounds to the target organs with a minimal cross-organ effect (Fig. S1, A and B). Surprisingly, although PERK inhibition in tumors effectively delayed tumor development, the blockade of splenic PERK signaling with both inhibitors led to a more remarkable and consistent tumor regression in Hepa mice (Fig. 1 B). This therapeutic effect was validated in an additional subcutaneous Lewis lung carcinoma (LLC) model (Fig. S1 C) and remained unchanged when the dose to the tumor or to the spleen was increased or reduced by threefold (Fig. S1 D).

Figure 1.

Pharmacological splenic-targeted PERK blockade reshapes the TME and inhibits tumor progression. (A) Continuous delivery of vehicle (veh), GSK, or AMG into the tumor or spleen of Hepa mice via a micro-osmotic pump system. (B) Representative bioluminescence images (upper panel) and the tumor burden (lower panel) in Hepa mice (n = 5 mice per group) with pump-mediated delivery of veh, GSK, or AMG into the tumor (T) or spleen (SP); p, photons. (C) Fold-changes of tumor infiltrate (upper panel) or splenocyte (lower panel) frequencies determined by flow cytometry. Values are reported relative to the indicated cell percentages in the T-veh group (n = 5 mice per group). (D) Suppressive activity of tumor-infiltrating CD11b+Gr-1high PMN-like cells toward T cell proliferation (n = 5 mice per group); none, without αCD3/28 antibody stimulation. (E) Percentages of tumor-infiltrating IFN-γ+ CTLs (n = 5 mice per group). (F) Tumor burden in sham surgery (Sham) or splenectomy (SPX) along with the indicated treatments (n = 5–7 mice per group). (G) Fold-changes in tumor infiltrate (left panel) or splenocyte (right panel) frequencies determined by flow cytometry (n = 5–6 mice per group). Values are presented relative to the indicated cell percentages in the sham-veh group. (H) Suppressive effects of tumor-infiltrating PMN-like cells (n = 6 mice per group). (I) Percentages of tumor-infiltrating IFN-γ+ CTLs (n = 5–7 mice per group). (J) Cartoon depicting the adoptive transfer assay. (K) Suppressive activity of donor-derived PMN-like cells in tumors of recipient mice (n = 3 mice per group). (L) Cartoon depicting the photoconversion assay. (M) Number of tumor-infiltrating photoconverted PMN-like cells per gram of tumor tissue (n = 4 mice per group). (N) Suppressive activity of tumor-infiltrating photoconverted PMN-like cells (n = 4 mice per group). Error bars indicate the means ± SEM. Statistics: Student’s t test (M); two-way ANOVA corrected by Bonferroni’s (G, right panel), Dunnett’s (C and G, left panel), or Tukey’s (B, D–F, H, I, K, and N) test. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. Data are from two independent experiments.

Figure S1.

Pharmacological splenic-targeted PERK blockade reshapes the TME and inhibits tumor progression. (A) Concentrations of AMG in the indicated organs of Hepa mice after pump-mediated delivery of AMG into the tumor (T) or spleen (SP) or oral gavage of AMG, as determined by UPLC–MS/MS; related to Fig. 1 A. (B) p-PERK levels in the tumor and spleen tissues of the Hepa-mice, as determined by immunofluorescence staining; scale bar, 25 μm; related to Fig. 1 A. Veh, vehicle. (C) Tumor burden in LLC mice (n = 5 mice per group) with pump delivery of veh or AMG into the tumor (T) or spleen (SP). (D) Tumor burden in Hepa mice with pump delivery of different doses of AMG to the tumor (T) or spleen (SP), as determined by the interactive video information system system: 1/3× dose, 7 μg/d; 1× dose, 21 μg/d; 3× dose, 63 μg/d. (E) Alamar blue assay was used to analyze the viability of Hepa1-6 cells cultured with GSK (GSK, n = 3 samples). (F) Tumor burden in orthotopic Hepa NOD-SCID mice treated with vehicle or AMG (n = 4 mice per group) by oral gavage. (G) Differential expression of Ly6G and Ly6C on CD11b+Gr-1high PMN-like cells (PMN-MDSCs) and CD11b+Gr-1int monocytic cells (M-MDSCs) in the tumor and spleen from Hepa mice. The numbers in the flow cytometry plots indicate the proportions of gated cells. (H) Fold-changes in tumor infiltrate (left) or splenocyte (right) frequencies determined by flow cytometry. Values are presented relative to the indicated cell percentages in the T-veh group (n = 5 mice per group). (I) Percentages of PMN-like cells and monocytic cells in the CD45+ tumor-infiltrating cells from Hepa and LLC mice (n = 5 mice per group). (J) Proliferation assessed by flow cytometry in CFSE-labeled T cells cocultured with CD11b+Gr-1high PMN-like cells (4:1 ratio); related to Fig. 1 D. (K) Suppressive activity of tumor-infiltrating PMN-like cells on T cell proliferation (n = 5 LLC mice per group); none, without αCD3/28 antibody stimulation. (L) Percentage of tumor-infiltrating IFN-γ+ CTLs from LLC mice (n = 5 mice per group). (M) Percentages of PMN-like cells and monocytic cells among the CD45+ tumor-infiltrating cells from Hepa mice receiving the indicated treatment (n = 5–7 mice per group). Error bars indicate the means ± SEM. Statistics: One-way ANOVA corrected with Tukey’s test (E and L); two-way ANOVA corrected by Dunnett’s test (H) or Tukey’s test (C, D, I, K, and M). *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. Data are from one experiment with organs pooled from three to five mice (A), two independent experiments (C, D, F, and H–M), or three independent experiments (E) or are representative of three independent experiments (B and G).

The antitumor effect of PERK-i was immune dependent, because PERK-i failed to alter tumor cell viability in culture (Fig. S1 E) or tumor growth in immunodeficient mice (Fig. S1 F). To investigate the underlying mechanism of the organ-targeted PERK-i treatments, we analyzed the changes in the immune components of the TME in Hepa mice. PMN-like MDSCs are the major suppressive MDSC subset in this Hepa tumor (Wu et al., 2018). Although the frequencies of tumor-infiltrating phenotypic CD11b+Gr-1high (equivalent to Ly6G+Ly6Clow; Fig. S1 G) PMN-like cells were similar across all groups (Fig. 1 C, upper panel), the PERK-i treatments markedly impaired the suppressive activity of these cells toward CD8+ T cell proliferation (Figs. 1 D and S1 J). Consistently, the frequency of tumor-infiltrating IFNγ+CD3+CD8+ CTLs was significantly increased in response to the PERK-i treatments (Fig. 1 E). Further comparison revealed that the spleen-targeted PERK-i treatments induced a more robust malfunction of tumor PMN-MDSCs and a greater increase in tumor CTLs than the tumor-targeted treatments using the same molecules (Fig. 1, D and E). Similar results were found in LLC-bearing mice (Fig. S1, H, I, K, and L). Based on these findings, the blockade of PERK signaling in the spleen more effectively restrains the immunosuppressive function of tumor MDSCs than tumor-targeted PERK inhibition.

PERK blockade in the spleen inhibits suppressive myeloid cell generation

In contrast to the similar compositions of immune cells infiltrating tumor tissues (Fig. 1 C, upper panel; and Fig. S1 H, left panel), delivering PERK-i to the spleen, but not the tumor, induced a profound decrease in the number of spleen cells of the myeloid lineage (Fig. 1 C, lower panel; and Fig. S1 H, right panel). The affected cell types ranged from myeloid progenitor cells, such as lineage (lin)low/−Sca1+c-Kithigh (LSK) cells and granulocyte/macrophage progenitors (GMPs, linlow/−Sca1−c-KithighCD34highCD16/32high), to later monocytic (CD11b+Gr-1int or Ly6G−Ly6Chigh; Fig. S1 G) and PMN-like cells, suggesting a profound reduction in splenic myelopoiesis.

Consistent with a recent report (Mohamed et al., 2020), systemic PERK-i treatment in spleen-competent mice effectively suppressed tumor growth (Fig. 1 F) and recapitulated the immune changes observed following the spleen-targeted PERK-i treatment, including the reduced splenic myelopoiesis but not tumor infiltrates (Figs. 1 G and S1 M), impaired tumor PMN-MDSC function (Fig. 1 H), and increased IFNγ+ CTL levels in the tumor tissues (Fig. 1 I). However, the PERK blockade in the splenectomized Hepa mice exhibited no efficacy compared with vehicle treatment (Fig. 1, F–I; and Fig. S1 M), suggesting that the spleen is an important target organ mediating the therapeutic efficacy of systemic PERK-i administration.

PERK blockade in the spleen and splenectomy impaired splenic myelopoiesis and dampened myeloid cell suppressive function in the tumor, with little effect on myeloid cell frequencies. We replenished the spleen-derived MDSCs in splenectomized mice by adoptive cell transfer (Fig. 1 J) and found that donor (spleen)-derived tumor MDSCs exhibited a much stronger suppressive capability than host (presumably BM-derived) myeloid cells, although isolated from the same tumor (Fig. 1 K). This difference diminished when the donor spleen myeloid cells were from PERK-i treated Hepa mice. These findings were further supported by an in vivo lineage-tracing experiment using mice that express the green-to-red irreversibly photoconvertible protein Kikume Green-Red (hereafter referred to as KikGR mice; Fig. 1 L). Spleen-derived MDSCs isolated from the tumor were profoundly more potent in suppressing CD8+ T cell proliferation than BM-derived myeloid cells. Targeted delivery of the PERK antagonist into the spleen markedly reduced spleen-derived MDSCs in the tumor and almost aborted their suppressive capability, with no effect on BM-derived cells (Fig. 1, M and N). Together, these data suggest that PERK-mediated splenic myelopoiesis is an indispensable source of suppressive myeloid cells in the tumor.

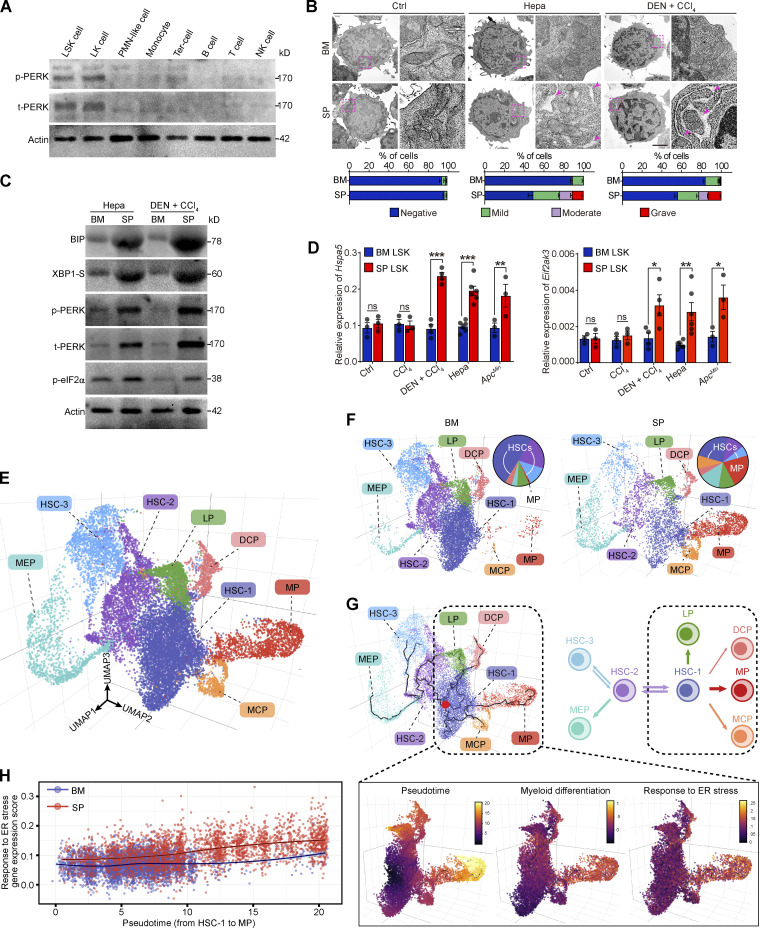

Cancer-associated splenic HSPCs exhibit robust ER stress and PERK activation

The mechanism by which PERK blockade alters splenic myelopoiesis remained to be determined. Immunoblotting (IB) analysis revealed that PERK activation was almost restricted to the LSK cells and, to a lesser extent, subsequent linlow/−Sca1−c-Kithigh (LK) myeloid progenitor cells (Fig. 2 A). Consistent with a recent report (Mohamed et al., 2020), the expression level of phosphorylated-PERK (p-PERK) in the differentiated splenic CD11b+Gr-1+ MDSCs, splenic lymphocytes, and erythroid cells from tumor-bearing mice was very low. Indeed, the splenic LSK cells exhibited dilated ER, a hallmark of ER stress, in both the transplanted and N-nitrosodiethylamine and carbon tetrachloride (DEN + CCl4)–induced hepatoma models (Fig. 2 B). Consistently, key UPR mediators including binding immunoglobulin protein (BIP, encoded by Hspa5), PERK–eIF2α, and spliced XBP1 (XBP1-S; Fig. 2, C and D; and Fig. S2 A), but not ATF6α (Fig. S2 B), were significantly upregulated in the splenic LSK cells from Hepa mice, but not in their BM counterparts. The upregulation of ER stress response genes was also observed in mice bearing DEN + CCl4–induced hepatomas or Apc gene mutation-driven intestinal neoplasia (Fig. 2, C and D; and Fig. S2, A and B). These findings suggest that a large proportion of splenic early HSPCs in tumor-bearing mice markedly exhibit signs of robust ER stress.

Figure 2.

Robust ER stress response with PERK activation is concomitant with early myeloid commitment in splenic HSPCs. (A) IB analysis of PERK expression in different splenic subsets from Hepa mice. t, total. (B) Representative microphotographs of LSK cell morphology and the proportions of cells with different degrees of ER dilation (lower panel, n = 2 samples per group, with cells pooled from 25–80 mice). Arrows denote dilated ER. Scale bar, 2 μm. (C) IB analysis of BIP, XBP1-S, PERK, and p-eIF2α levels in BM and spleen (SP) LSK cells from Hepa mice. (D) Hspa5 and Eif2ak3 mRNA expression in BM and SP LSK cells from control, CCl4-treated, CCl4 + DEN–treated, Hepa, and ApcMin mice (n = 3–6 samples per group, with cells pooled from three to five mice). Values are presented relative to Actb mRNA expression. (E) 3D UMAP graph of single LSK cells from Hepa mice. LP, lymphoid-biased progenitor; DCP, dendritic cell progenitor; MCP, mast cell progenitor. (F) Proportions of eight clusters in BM and SP LSK cells. (G) Single-cell trajectory analysis (upper panel) of LSK cells. A root node (red dot) in the HSC-1 cluster was defined as the starting point of differentiation. (H) Correlation between genes associated with the ER stress response and genes involved in myeloid commitment. Error bars indicate the means ± SEM. Statistics: Two-way ANOVA corrected by Bonferroni’s test. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. Data are from one experiment with cells pooled from 15 mice (E–H) or two independent experiments (B and D) or are representative of two experiments with cells pooled from 5 to 10 mice (A and C). Source data are available for this figure: SourceDataF2.

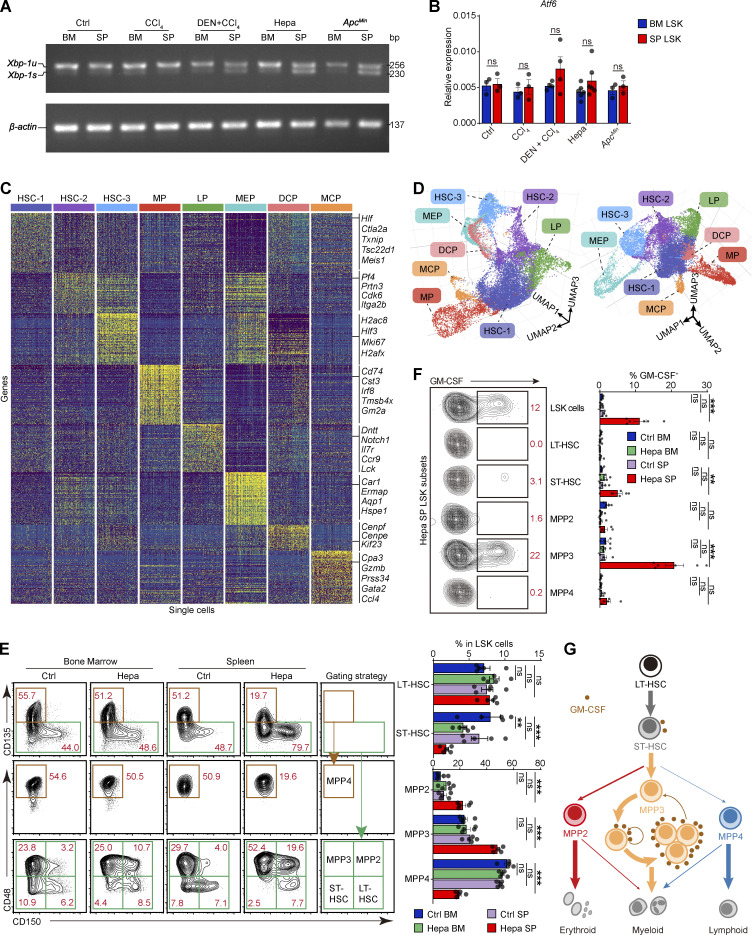

Figure S2.

Robust ER stress response is concomitant with early myeloid commitment in splenic HSPCs. (A) Xbp-1 splicing in LSK cells from the indicated mice as determined by RT-PCR. u, unspliced. (B) Atf6 expression levels in BM and SP LSK cells from the indicated mice; related to Fig. 2 D (n = 3–6 samples, with cells pooled from three to five mice). (C) Single-cell expression profiles of each LSK cell cluster from Hepa mice. From each cluster, 200 randomly sampled cells are shown. LP, lymphoid-biased progenitor; DCP, dendritic cell progenitor; MCP, mast cell progenitor. (D) Two visual perspectives of the 3D UMAP dimensionality reduction in addition to the one shown in Fig. 2 E. (E) Phenotypes and proportions of HSPC subsets in BM and spleen LSK cells from control and Hepa mice, as determined by flow cytometry (n = 5 mice per group). LT, long term; ST, short term. Numbers in the plots indicate the proportions of gated cells in the LSK cells. (F) Percentages of GM-CSF–expressing cells in each LSK cell subpopulation, as determined by flow cytometry (Ctrl, n = 5 mice; Hepa, n = 6 mice). Numbers in the plots indicate the proportions of gated cells in the plot. (G) Schematic illustrating the lineage commitment and differentiation of LSK cell subsets. A model of endogenous GM-CSF–driven, positive self-feedback–based MPP3 expansion is shown. Error bars indicate the mean ± SEM. Statistics: Two-way ANOVA corrected by Bonferroni’s test (B) or Dunnett’s test (E and F). **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. Data are from one experiment, with cells pooled from 15 mice (C and D), or two independent experiments (B, E, and F) or are representative of two independent experiments (A). Source data are available for this figure: SourceDataFS2.

ER stress response is linked to the myeloid-biased potential of cancer-associated splenic HSPCs

Subsequently, we explored whether the ER stress response is linked to the distinct cellular composition and function of HSPCs in the spleen. Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) was performed using BM and splenic LSK cells isolated from Hepa mice, and eight HSPC clusters were identified (Fig. 2 E; Fig. S2, C and D; and Table S1). Notably, the proportion of multipotent clusters (annotated as HSC-1, HSC-2, and HSC-3, consistent with the literature; Izzo et al., 2020) decreased from 83% in the BM LSK cell population to 41% in the splenic LSK population. In contrast, a myeloid-biased early progenitor (MP) cluster that was rare (∼1.2%) in the BM constituted >20% of the splenic LSK cells (Fig. 2 F). The MP cluster expressed myeloid differentiation genes, such as Cd74, Cst3, Irf8, Tmsb4x, and Gm2a (Fig. S2 C and Table S2), which is analogous to a myeloid-biased multipotent progenitor (MPP) subset known as MPP3 (Table S3; Oguro et al., 2013; Pietras et al., 2015). We previously identified that the ability to produce and respond to GM-CSF is a feature of committed tumor-promoting myeloid progenitor cells in the spleen (Wu et al., 2018). Consistently, flow cytometry showed that MPP3 cells, especially those expressing GM-CSF, were significantly expanded in the spleen of the tumor-bearing mice (Fig. S2, E and F), which may drive myeloid progenitor cell expansion in a self-feedback–based manner in the spleen (Fig. S2 G).

The trajectory analysis revealed that the MP cluster originated from the HSC-1 subset (Fig. 2 G). The differentiation process from HSC-1 to MP along the trajectory described as the pseudo-time was correlated with the concurrent upregulation of genes that control myeloid commitment (Izzo et al., 2020) and genes involved in the response to ER stress (Fig. 2 G). Notably, the upregulation of ER stress response genes was more robust in the splenic LSK cells than the BM LSK cells during myeloid commitment (Fig. 2 H). Altogether, these findings suggest that the activation of the ER stress response is closely related to the expansion and early myeloid-biased differentiation of cancer-associated splenic LSK cells.

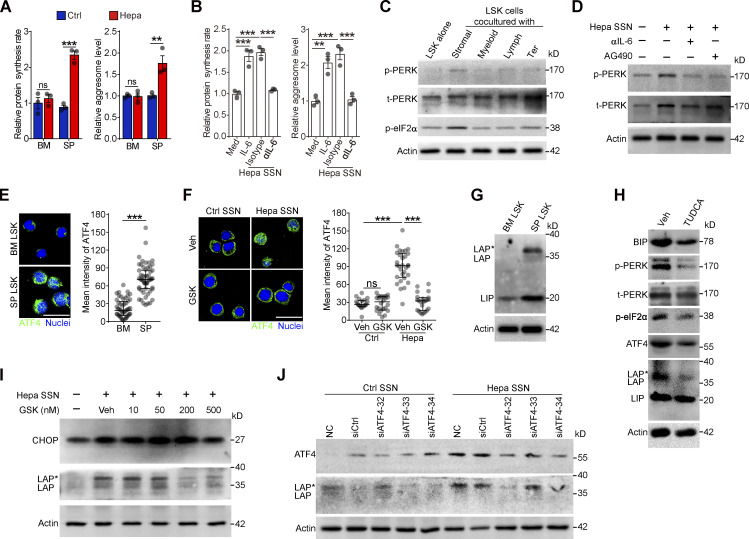

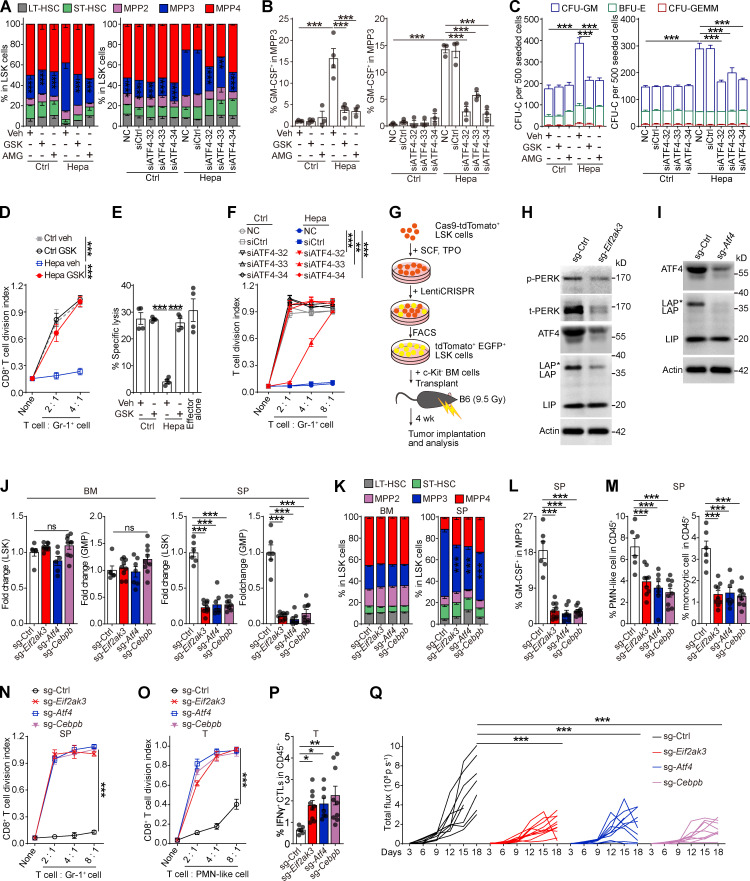

PERK activation in splenic HSPCs promotes MDSC generation

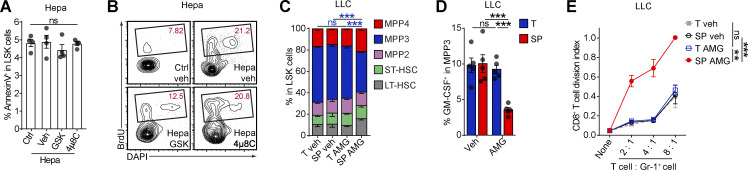

Then, we examined the impact of the ER stress response on HSPC function. Although neither PERK-i (GSK) nor an XBP-1 inhibitor (4μ8C) affected LSK cell survival (Fig. S3 A), the administration of GSK, but not 4μ8C, significantly inhibited LSK cell proliferation (Figs. 3 A and S3 B). To confirm that PERK directly modulates HSPC activity, we pretreated naive BM-derived LSK cells with either PERK or XBP-1 inhibitors and then transferred these cells into the spleen of Hepa mice (Fig. 3 B). An average of 51.2% of the donor-derived cells exhibited a myeloid cell phenotype (Gr-1+) 2 d after transplantation in the tumor-bearing recipients, whereas PERK inhibition resulted in a decrease in this percentage to 13.5% (Fig. 3 C). Moreover, the myeloid cells derived from the LSK cells pretreated with GSK lost their suppressive ability toward activated CD8+ T cells (Fig. 3 D). Similarly, genetic silencing of PERK rendered LSK cells unresponsive to induction by the cancer-conditioned splenic environment, resulting in unchanged myeloid differentiation and an inability to generate suppressive MDSCs (Fig. 3, E–G). Meanwhile, 4μ8C was unable to affect myelopoiesis in the LSK cells or descendant MDSC function, suggesting that PERK, but not XBP-1, mediated the increased MDSC generation from the cancer-conditioned splenic LSK cells.

Figure S3.

Robust PERK activation promotes myelopoiesis in splenic LSK cells. (A) Effects of 4μ8C and GSK on splenic LSK cell survival, determined by flow cytometry (n = 4 mice per group). Veh, vehicle. (B) Flow cytometry plots, related to Fig. 3 A. Numbers in the plots indicate the proportions of gated cells. (C and D) Proportions of subsets in splenic LSK cells (C): percentage of GM-CSF–expressing cells in splenic MPP3 population (D) from LLC mice. (E) Suppressive activity of PMN-like descendants of splenic LSK cells from LLC mice (n = 3 samples, with cells pooled from three mice). Error bars indicate the mean ± SEM. Statistics: One-way (A) or two-way (C–E) ANOVA corrected by Tukey’s test. **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. Data are from two independent experiments (A, C, and D), or three independent experiments (E) or are representative of two independent experiments (B). LT, long term; SP, spleen; ST, short term; T, tumor.

Figure 3.

PERK activation promotes myelopoiesis in splenic LSK cells. (A) Effects of 4μ8C and GSK on splenic LSK cell proliferation in vivo (n = 4 mice per group). Veh, vehicle. (B) Cartoon depicting the adoptive transfer assay. (C) Percentages of donor-derived CD11b+Gr-1+ myeloid cells. The numbers in the flow cytometry plots indicate the proportions of gated cells. (D) Suppressive activity of donor-derived CD11b+Gr-1+ myeloid descendants. (E) Cartoon depicting the adoptive transfer assay. (F) Percentages of donor-derived CD11b+Gr-1+ myeloid cells, as determined by flow cytometry. (G) Suppressive activity of donor-derived CD11b+Gr-1+ myeloid descendants. (H–J) Proportions of subsets in splenic LSK cells (H), percentage of GM-CSF+ cells in splenic MPP3 cells (I), and suppressive activity of Gr-1+ myeloid descendants of splenic LSK cells (J) from Hepa mice receiving the indicated treatments as described in Fig. 1 A (n = 5 mice per group). (K and L) Proportions of HSPC subsets in splenic LSK cells (K) and percentage of GM-CSF+ cells in MPP3 (L) from Hepa mice with the indicated oral treatments (Veh, n = 6 mice; GSK, n = 7 mice). Error bars indicate the means ± SEM. Statistics: Student’s t test (L); one-way ANOVA corrected by Tukey’s test (A, C, and F); two-way ANOVA corrected by Bonferroni’s test (K) or Tukey’s test (D and G–J). **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. Data are from two independent experiments (A, H, I, K, and L) or three independent experiments (C, D, F, G, and J, n = 3 samples per group, with cells pooled from three mice).

These findings were supported by the results of the organ-targeted and systemic PERK-i administration experiments. Spleen-targeted, but not tumor-targeted, PERK blockade markedly decreased the proportion of myeloid-biased MPP3 in splenic LSK cells, especially the GM-CSF+ MPP3 fraction (Fig. 3, H and I; and Fig. S3, C and D). Because of the central role of HSPC-derived GM-CSF in splenic myeloid differentiation and MDSC generation (Wu et al., 2018), the reduction in GM-CSF–expressing HSPCs led to the loss of suppressive function in myeloid descendant cells derived from these HSPCs (Figs. 3 J and S3 E). Similar results were observed in Hepa mice treated with systemic PERK-i administration (Fig. 3, K and L), which might explain the decreased splenic myelopoiesis and malfunction of tumor MDSCs (Fig. 1, C–E, G–I, and L–N). Based on these data, PERK activation plays an essential role in directing splenic HSPCs toward MDSC generation.

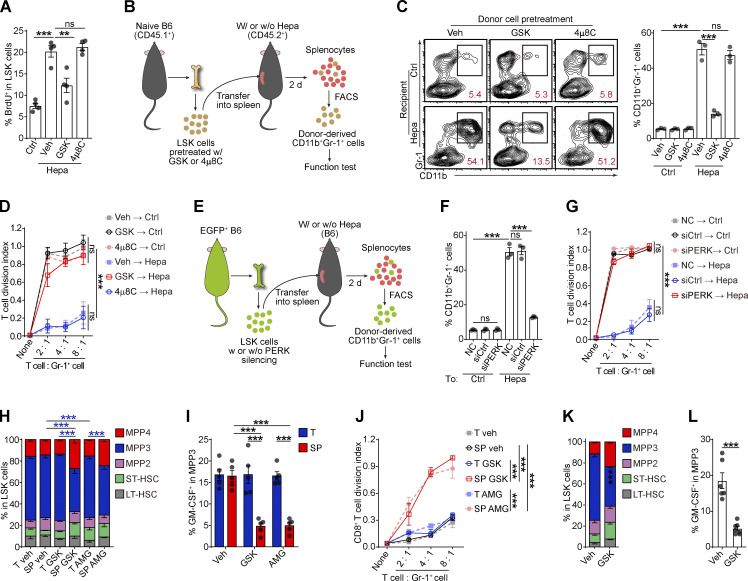

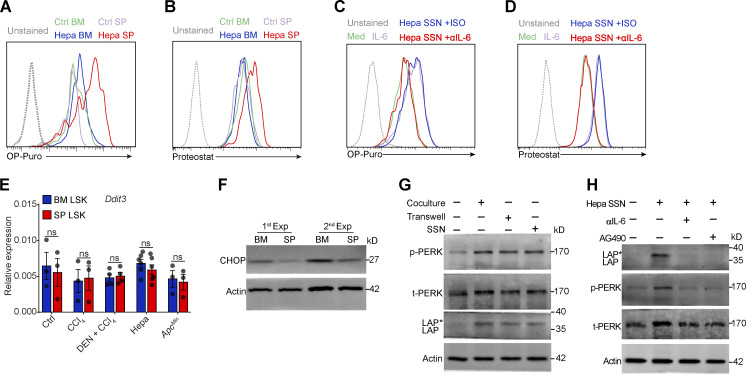

Splenic stroma activates PERK–ATF4–C/EBPβ signaling in HSPCs

The sustained ER stress and PERK activation in the splenic LSK cells suggests that the cancer-conditioned splenic niche had an educational effect. As expected, splenic LSK cells from Hepa mice exhibited increased protein synthesis and misfolded protein levels (Fig. 4 A and Fig. S4, A and B). The coculture of naive LSK cells with CD45− splenic stromal cells or the exposure of LSK cells to splenic stromal cell culture supernatant (SSN) from Hepa mice mimicked this effect (Fig. 4 B and Fig. S4, C and D), which subsequently induced the phosphorylation of PERK and its downstream factor eIF2α (Fig. 4 C). Levels of IL-6 are upregulated in the splenic stroma and essential to distort HSPC function by activating STAT3 (Wu et al., 2018). We found that IL-6 neutralizing antibodies or STAT3 inhibitors effectively reduced protein synthesis, misfolded protein accumulation, and subsequently PERK phosphorylation (Fig. 4, A–D; and Fig. S4, A–D). Therefore, these data indicated that the activation of IL-6/STAT3 signaling triggers PERK activation in HSPCs by inducing ER stress.

Figure 4.

Tumor-associated splenic stroma induces ER stress responses in HSPCs and activates PERK–ATF4–C/EBPβ signaling. (A and B) Protein synthesis rates and levels of protein aggregates in BM and spleen (SP) LSK cells from control and Hepa mice (A, n = 3 mice per group) or in LSK cells cultured with Hepa mouse-derived SSN (Hepa SSN; B). (C) IB analysis of PERK and p-eIF2α levels in LSK cells cocultured with the indicated splenic cell types. (D) Effects of Hepa SSN, anti–IL-6 neutralizing antibody (αIL-6), and STAT3 inhibitor (AG490) on PERK expression in LSK cells. (E and F) Expression and distribution of ATF4 in LSK cells from Hepa mice (E) or in cultured LSK cells with the indicated treatments (F). Scale bar, 25 μm. Veh, vehicle. (G) IB analysis of the expression of the C/EBPβ isoforms (LAP*, LAP, and LIP) in BM and splenic LSK cells from Hepa mice. (H) IB analysis of ER stress response signaling in splenic LSK cells from Hepa mice. Mice were treated with TUDCA or vehicle via spleen-targeted micro-osmotic pump delivery. (I) IB analysis of CHOP and C/EBPβ isoforms in LSK cells under the indicated conditions. (J) IB analysis of ATF4 and C/EBPβ isoforms in LSK cells with indicated treatments. Error bars indicate the means ± SEM (A and B) or medians and IQRs (E and F). Statistics: Mann–Whitney U test (E and F); one-way ANOVA corrected by Tukey’s test (B), two-way ANOVA corrected by Bonferroni’s test (A). **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. In E and F, dots are representative of 20–50 cells from two samples per group. Data are from two independent experiments (A) or three independent experiments (n = 3 samples) with cells pooled from three mice (B, E, and F) or are representative of two independent experiments (C, D, and G–J). t, total. Source data are available for this figure: SourceDataF4.

Figure S4.

Tumor-associated splenic stroma reprograms HSPCs by triggering PERK–ATF4–CEBPβ signaling activation. (A and B) Histogram of FACS results; related to Fig. 4 A. (C and D) Histogram of FACS results; related to Fig. 4 B. (E) Ddit3 (CHOP) mRNA levels in BM and splenic LSK cells from ctrl, CCl4, CCl4 + DEN, Hepa, and ApcMin mice, as determined by a TaqMan gene expression assay (n = 3–6 samples, with cells pooled from three to five mice). Values are presented relative to Actb mRNA expression. (F) IB analysis of CHOP expression in BM and splenic LSK cells from Hepa mice. (G) IB analysis of the levels of the PERK and C/EBPβ isoforms in LSK cells exposed to Hepa SSN. (H) IB analysis of PERK and C/EBPβ isoform expression in LSK cells in the indicated system. Error bars indicate the mean ± SEM. Statistics: Two-way ANOVA corrected by Bonferroni’s test (E). Data are from two independent experiments (A–E) or are representative of two independent experiments (F–H). SP, spleen; t, total. Source data are available for this figure: SourceDataFS4.

Next, we investigated how this PERK pathway of the UPR is linked to signals directing MDSC generation from HSPCs. Compared with the BM LSK cells, the splenic LSK cells from the Hepa mice exhibited upregulated expression and increased nuclear translocation of ATF4 (Fig. 4 E), a transcription factor activated by the PERK-eIF2α axis (Bettigole and Glimcher, 2015). Exposure to Hepa SSN recapitulated these changes in the expression and localization of ATF4 in LSK cells in vitro, which was disrupted by PERK blockade (Fig. 4 F). However, the expression of downstream C/EBP homologous protein (CHOP, encoded by Ddit3) was not increased in the Hepa splenic LSK cells (Fig. S4, E and F). Instead, we detected increased expression of C/EBPβ (LAP*/LAP and LIP isoforms), which is another C/EBP family member and a key factor directing emergency myelopoiesis (Hirai et al., 2006; Li et al., 2018; Marigo et al., 2010), in the splenic LSK cells from Hepa mice (Fig. 4 G) or in the LSK cells treated with Hepa SSN (Fig. S4 G). Reducing ER stress by delivering tauroursodeoxycholate (TUDCA) to the spleen markedly decreased the levels of p-PERK, p-eIF2α, ATF4, and the LAP*/LAP isoform of C/EBPβ in splenic LSK cells (Fig. 4 H). Consistent with these findings, blocking IL-6–STAT3 signaling (Fig. S4 H), inhibiting PERK phosphorylation (Fig. 4 I), or silencing ATF4 expression (Fig. 4 J) effectively disrupted the upregulation of C/EBPβ (LAP*/LAP) expression in vitro. Therefore, cancer-conditioned splenic stroma activated PERK–ATF4–C/EBPβ signaling in LSK cells.

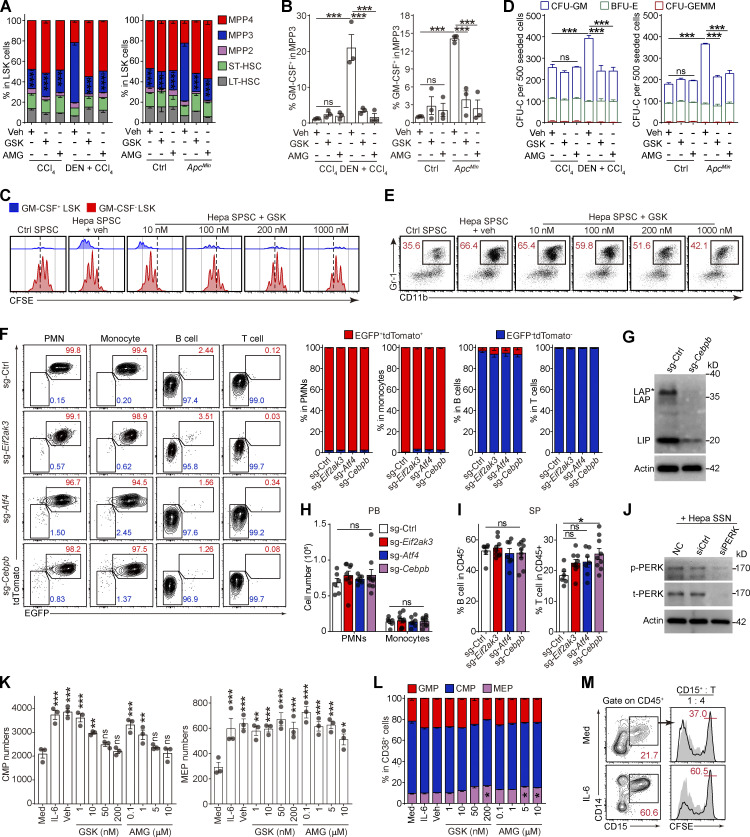

PERK–ATF4–C/EBPβ signaling directs HSPC differentiation into MDSCs

The effect of this PERK–ATF4–C/EBPβ pathway on splenic HSPC function was then examined both in vitro and in vivo. Consistent with the results of spleen-targeted PERK blockade (Fig. 3, H and I), in vitro treatment with PERK-i or ATF4 siRNAs profoundly impeded the expansion of the MPP3 subset (Figs. 5 A and S5 A), the upregulation of GM-CSF (Fig. 5 B and Fig. S5, B and C), and the enhanced myelopoiesis (Fig. 5 C and Fig. S5, D and E) induced by tumor-associated SSN from different models. This education by the tumor-associated SSN not only increased the scale of myelopoiesis but also reprogrammed HSPCs to become committed MDSC progenitors that readily generate potent suppressive cells, even in tumor-free mice (Wu et al., 2018). The inhibition of PERK signaling in the LSK cells abolished this educational effect, rendering the descendant myeloid cells unable to suppress CD8+ T cell proliferation (Fig. 5 D) and antigen-specific cytotoxic killing (Fig. 5 E). Similar results were obtained with an siRNA against ATF4 (Fig. 5 F).

Figure 5.

PERK–ATF4–C/EBPβ signaling reprograms splenic LSK cells to support tumor-associated myelopoiesis in the spleen. (A–F) Naive BM LSK cells were pretreated with vehicle (veh; 0.1% DMSO), PERK inhibitors (GSK, 250 nM; AMG, 5 μM), or ATF4 siRNAs before stimulation with SSN of different origins. After 4 d of culture, the proportions of HSPC subsets (A), percentages of GM-CSF+ cells in MPP3 (B), CFU-C activity (C), ability to generate myeloid descendants capable of suppressing CD8+ T cell proliferation (D and F), and antigen-specific cytotoxicity (E) were determined. (G) Cartoon depicting the gene-edited HSPC transplantation assay. (H and I) IB analysis of PERK, ATF4, and C/EBPβ isoform expression in splenic LSK cells from mice that received control, Eif2ak3-KO, or Atf4-KO HSPC transplantation. t, total. (J–M) Changes in the HSPC number (J), LSK cell constitution (K), percentage of GM-CSF+ cells in MPP3 (L), and frequencies of splenic myeloid cells (M). (N) Suppressive activity of Gr-1+ descendants generated from splenic LSK cells in vitro. (O) Suppressive activity of tumor-infiltrating PMN-like cells. (P) Percentages of tumor-infiltrating IFN-γ+ CTLs in CD45+ cells. In J–M, O, and P, n = 6–9 mice per group. (Q) Tumor growth in mice that received control, Eif2ak3-KO, or Atf4-KO, and Cebpb-KO HSPC transplantation (n = 9–10 mice per group). Error bars indicate the means ± SEM. Statistics: One-way ANOVA corrected by Dunnett’s test (J, L, M, and P) or Tukey’s test (B and E); two-way ANOVA corrected by Dunnett’s test (A, C, D, F, K, N, O, and Q). *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. Data are from two independent experiments (J–M and O–Q), or three to four independent experiments (A–F and N; n = 3–4 samples per group, with cells pooled from three mice) or are representative of two independent experiments (H and I). SP, spleen; T, tumor. Source data are available for this figure: SourceDataF5.

Figure S5.

PERK–ATF4–CEBPβ signaling reprograms splenic LSK cells to support tumor-associated myelopoiesis in the spleen. (A, B, and D) Naive BM LSK cells were pretreated with vehicle (0.1% DMSO) or PERK inhibitors (GSK, 250 nM; AMG, 5 μM) before exposure to SSNs from control, CCl4, DEN + CCl4, or ApcMin mice with the indicated supplements. After 4 d of culture, the proportions of HSPC subsets (A), percentages of GM-CSF–expressing cells in MPP3 (B), and CFU-C activity (D) were determined (n = 3 samples, with cells pooled from three mice each). Veh, vehicle. (C) Proliferation of GM-CSF+ and GM-CSF− LSK cells cocultured with Hepa mouse splenic stromal cells (SPSCs), as measured using a CFSE assay. (E) Effect of GSK on the Hepa SPSC-induced frequency of CD11b+Gr-1+ myeloid descendants. Numbers in the plots indicate the proportions of gated cells in the LSK cells. (F) Percentages of donor-derived (EGFP+tdTomato+) or host/rescue-derived (EGFP−tdTomato−) cells in CD11b+Gr-1 highLy6ClowLy6G+ PMNs, CD11b+Gr-1intLy6ChighLy6G− monocytes, B220+ B cells, and CD3+ T cells in the peripheral blood (PB) of recipient mice bearing Hepa tumors, as determined by flow cytometry. The numbers in the flow cytometry plots indicate the proportions of gated cells. (G) IB analysis of the expression of CEBP isoforms (LAP*, LAP, and LIP) in splenic LSK cells from control or Cebpb-KO HSPC transplanted mice. (H) Numbers of PMNs or monocytes per milliliter of peripheral blood (PB) from HSPC-transplanted mice. (I) Percentage of B220+ B cells or CD3+ T cells in the CD45+ splenocytes of HSPC transplanted mice. (J) IB analysis of PERK expression in LSK cells exposed to Hepa SSN with or without PERK silencing; related to Fig. 6, D and E. (K) Numbers of CMPs and MEPs generated by 500 lin−CD34+CD38− HSPCs after 72 h of culture; related to Fig. 7 F (n = 3 samples). (L) The proportions of GMPs, CMPs, and MEPs among lin−CD34+CD38+ HSPCs after 72 h of culture; related to Fig. 7 F (n = 3 samples). (M) Phenotype (left) and suppressive activity (right) of CD15+ descendant cells generated from expanded CD34+ CB-HSPCs. Numbers in the plots indicate the proportions of gated cells. Error bars indicate mean ± SEM. Statistics: One-way ANOVA corrected by Dunnett’s test (B, I, and K); two-way ANOVA corrected by Dunnett’s (A, H, and L) or Tukey’s (D) test. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. Data are from two independent experiments (F, H, and I, sg-Ctrl, n = 6 mice; sg-Eif2ak3, n = 9 mice; sg-Atf4, n = 7 mice; sg-Cebpb, n = 9 mice) or three independent experiments (A, B, D, K, and M) or are representative of two to three independent experiments (C, E, G, and M). LT, long term; ST, short term. Source data are available for this figure: SourceDataFS5.

To further corroborate these findings in vivo, we genetically deleted Eif2ak3, Atf4, or Cebpb in HSPCs by CRISPR/Cas9 and then transferred these cells into lethally irradiated mice. After 4-wk blood cell reconstitution, hepatocellular tumor cells were transplanted into the liver to establish the orthotopic tumor model (Fig. 5 G). Blood chimerism showed that donor-derived, gene-edited HSPCs reconstituted most of the myeloid lineage, while T and B lymphocytes were rarely affected (Fig. S5 F). The gene-editing efficiency was confirmed by IB (Fig. 5, H and I; and Fig. S5 G). Genetic deletion of Eif2ak3, Atf4, or Cebpb in HSPCs did not alter myeloid cell numbers in blood or HSPC numbers in BM compared with those in the control (Fig. 5, J and K; and Fig. S5 H). However, eliminating any of these genes impeded expansion of the MPP3 subset (Fig. 5 K) and prevented the upregulation of GM-CSF (Fig. 5 L), which in turn hampered splenic myelopoiesis (Figs. 5 M and S5 I) and prevented splenic HSPCs from generating MDSCs (Fig. 5 N). As a result, tumor-infiltrating myeloid cells completely lost their immunosuppressive function (Fig. 5 O). Accordingly, the frequency of tumor-infiltrating IFNγ+ CTLs was significantly increased (Fig. 5 P), and tumor growth was delayed in these mice (Fig. 5 Q). Therefore, these in vitro and in vivo findings validated the essential role of the PERK–ATF4–C/EBPβ (LAP*/LAP) axis in regulating splenic HSPC reprogramming and its effect on the tumor immune microenvironment.

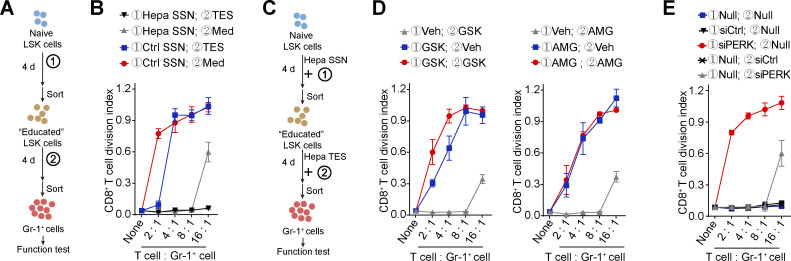

PERK activation in the HSPC preconditioning phase is required to generate functional MDSCs

Because both HSPC expansion/preconditioning in the spleen and MDSC pathological activation in the TME (Mohamed et al., 2020) require the involvement of PERK activity, we established an in vitro model to dissect the different impacts. BM-derived naive LSK cells were treated with SSN in the first phase and then exposed to tumor explant supernatant (TES) in the second phase (Fig. 6 A). Although the Hepa splenic stroma–preconditioned LSK cells were capable of producing potent Gr-1+ MDSCs, even without the TES stimulation, activation by TES further enhanced the function of the MDSCs and enabled them to fully suppress CD8+ T cell proliferation, even at a ratio of 1:16 (Fig. 6 B). The addition of PERK inhibitors to the culture or the knockdown of PERK expression with siRNAs in the second stimulation phase abolished the effect of TES, but the MDSCs still achieved full suppression at a ratio of 1:8 (Fig. 6, C–E; and Fig. S5 J). In contrast, the absence of Hepa SSN preconditioning (Fig. 6 B) or the inclusion of PERK-i (Fig. 6, C and D) or PERK silencing (Fig. 6, C and E) in the first phase severely impaired the suppressive function of the MDSCs. These results suggest a crucial role for PERK in splenic HSPC preconditioning and may help clarify the different roles of PERK signaling in the two phases of MDSC development.

Figure 6.

Different impacts of PERK blockade in the two phases of MDSC generation. (A and B) A two-step workflow to induce naive LSK cells to become suppressive MDSCs (A). Naive LSK cells received different combinations of first- and second-phase stimuli. The suppressive capability of the generated myeloid cells was tested at the end of the culture period (B). (C–E) Naive LSK cells were induced with SSN and TES from Hepa mice to become suppressive MDSCs (C). In this process, cells were treated with PERK inhibitors (D) or transfected with siRNAs against PERK (E) in the first and/or second phase of stimulation. The suppressive capability of the generated myeloid cells was tested at the end of the culture. Veh, vehicle; Null, no transfection. Error bars indicate means ± SEM. Data are from four independent experiments (n = 4 samples per group, with cells pooled from three to five mice).

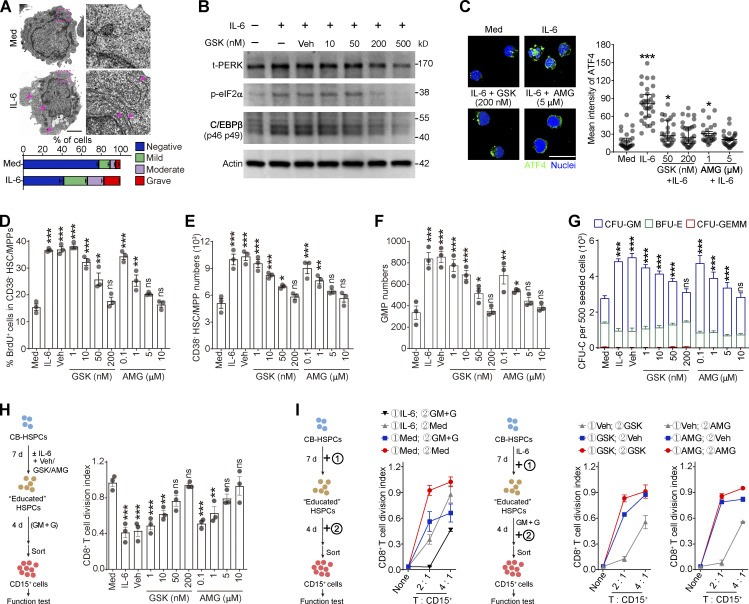

Human HSPC differentiation into MDSCs requires active PERK–ATF4–C/EBPβ signaling

Next, we sought to determine whether the above mechanism regulates the differentiation of human HSPCs into MDSCs. Human umbilical cord blood (CB)–derived CD34+ HSPCs were expanded in vitro with the stimulation of supportive cytokines. Consistent with our observations in mice, the addition of IL-6 to the culture effectively induced robust ER stress in human CD34+ HSPCs (Fig. 7 A) by activating the PERK–ATF4–C/EBPβ pathway (Fig. 7, B and C). IL-6 induced CD34+CD38− HSC/MPP cell proliferation (Fig. 7, D and E) and myeloid differentiation into CD34+CD38+CD45RA+CD123+ GMP cells in a PERK-dependent manner (Fig. 7 F). In contrast, the megakaryocyte/erythrocyte-biased progenitor (MEP) number was less affected by PERK blockade, showing a myeloid-biased effect on HSPC differentiation (Fig. S5, K and L). Consequently, PERK antagonists impaired the myeloid differentiation potential of IL-6–stimulated HSPCs (Fig. 7 G). Moreover, PERK activation in the CD34+ HSPCs endowed these cells with the capability to generate CD15+ PMN-MDSCs, which effectively suppressed CD8+ T cell proliferation (Figs. 7 H and S5 M). To further dissect the role of PERK in the preconditioning phase and/or the subsequent stimulation phase, we established an in vitro model similar to that shown in Fig. 6. Consistently, the addition of GSK or AMG in the first phase effectively abolished the suppressive ability of the PMN-MDSCs, whereas blocking PERK activation in the second phase only marginally affected the suppressive function (Fig. 7 I). Altogether, these findings suggest that the ER stress response and activated PERK–ATF4–C/EBPβ pathway in the expansion/preconditioning phase reprogram human HSPCs into potent MDSC progenitors.

Figure 7.

Activation of PERK–ATF4–C/EBPβ signaling is essential for human HSPC differentiation into MDSCs. (A) Representative microphotographs of CB-HSPC morphology. Arrows denote dilated ER. Scale bar, 2 μm; Med, SFEM supplemented with SCF, TPO, and Flt3L. (B) IB analysis of total PERK (t-PERK), C/EBPβ, and p-eIF2α levels in CB-HSPCs cultured under the indicated conditions. (C) Expression and distribution of ATF4 in cultured human HSPCs. Scale bar, 25 μm. (D) Effects of PERK inhibitors on CD34+CD38− HSC/MPP proliferation. (E and F) Numbers of HSCs/MPPs (E) and GMPs (F) after 72 h of culture of 500 lin−CD34+CD38− HSCs/MPPs. (G) CFU-C activity in the cultured HSPCs on day 7. (H and I) Suppressive activity of CD15+ myeloid cells generated from CD34+ HSPCs under the indicated conditions. GM, GM-CSF; G, G-CSF. Error bars indicate means ± SEM (A and D–I) or median and IQR (C). Statistics: Kruskal–Wallis test (C); one-way (D–F and H) or two-way (G) ANOVA corrected by Dunnett’s test. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. Data are from three independent experiments (n = 3 samples per group) or are representative of three independent experiments (B and C). Source data are available for this figure: SourceDataF7.

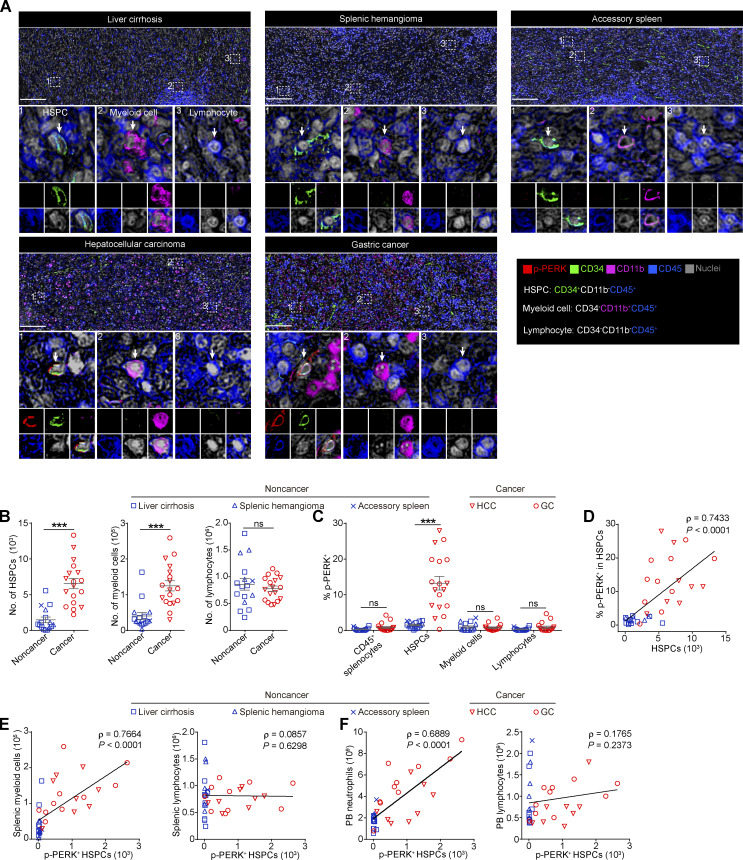

HSPCs in the spleen of cancer patients exhibit upregulated PERK activation

To determine the in situ PERK activation level in the spleens of patients, we assessed the expression of p-PERK in spleen tissues from patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC, n = 8) or gastric cancer (GC, n = 10) and patients with noncancer pathologies, including liver cirrhosis (n = 10), splenic hemangioma (n = 5), and accessory spleen (n = 1). The multiplex immunohistochemistry (mIHC) analysis showed that the frequencies of CD34+ HSPCs (CD11b−CD34+CD45+) and CD11b+ myeloid cells (CD11b+CD34−CD45+), but not CD11b− lymphocytes (CD11b−CD34−CD45+), were significantly increased in the red pulp area of the spleen tissues from the cancer patients (Fig. 8, A and B). Furthermore, compared with those in the spleen of the noncancer patients, a significantly larger proportion of splenic HSPCs in the spleen of the HCC or GC patients expressed p-PERK (Fig. 8, A and C). This elevated activation level of PERK was not observed in other CD45+ splenocytes in the spleen (Fig. 8, A and C), which is consistent with observations in mouse models (Fig. 2 A). Moreover, we noted that the percentage of p-PERK+ HSPCs correlated with the density of HSPCs in the spleen, suggesting that PERK signaling may contribute to HSPC expansion and myelopoiesis in the human spleen (Fig. 8 D). In support of this hypothesis, the density of the splenic p-PERK+ HSPCs in the cancer patients not only correlated with the accumulation of myeloid cells (but not lymphocytes) in the spleen (Fig. 8 E), but also was associated with the increase in blood neutrophils (Fig. 8 F). Collectively, these in situ human data are consistent with our findings in mice and in vitro models, supporting the important role of PERK in regulating splenic HSPC expansion and cancer-associated splenic myelopoiesis.

Figure 8.

Upregulated p-PERK expression in splenic HSPCs is correlated with extramedullary myelopoiesis in cancer patients. (A) Representative mIHC images of p-PERK expression in CD34+CD11b−CD45+ HSPCs (1), CD34−CD11b+CD45+ myeloid cells (2), and CD34−CD11b−CD45+ lymphocytes (3) in spleen tissues from noncancer and cancer patients. Scale bar, 200 μm. (B) Densities of HSPCs, myeloid cells, and lymphocytes in splenic specimens from noncancer and cancer patients. Splenocyte densities were calculated as cell numbers per cm2 splenic red pulp. (C) Percentage of p-PERK+ cells in different cell populations. (D) Correlation between p-PERK expression in HSPCs and the HSPC density in the spleen. (E) Correlation between the densities of splenic p-PERK+ HSPCs and splenic myeloid cells or lymphocytes. (F) Correlation between the splenic p-PERK+ HSPC density and neutrophil or lymphocyte number per liter of peripheral blood (PB) from patients. Error bars indicate means ± SEM. Statistics: Mann–Whitney U test (B and C); Spearman’s rank correlation analysis and linear regression analysis (D–F). ***, P < 0.001. Data are from four independent experiments (accessory spleen, n = 1; splenic hemangioma, n = 5; liver cirrhosis, n = 8; HCC, n = 10; GC, n = 10).

Discussion

Tumor-associated splenic extramedullary hematopoiesis is a distinct HSPC response that supports the generation of immunosuppressive myeloid cells and serves as a foundation for the systemic tumor-promoting myeloid response. Here, we identified that the ER stress sensor PERK is a crucial driver of altered splenic HSPC activities in cancer. The activation of PERK–eIF2α–ATF4 signaling upregulated expression of the key transcription factor C/EBPβ, which in turn led to the expression of GM-CSF, expansion of the myeloid-biased MPP3 subset, and generation of MDSCs. Delivering PERK inhibitors to the spleen was sufficient and more effective in rerouting tumor MDSCs and reshaping the TME with antitumor effects than blocking PERK signaling in tumors. These findings suggest that spleen-targeted PERK blockade reprograms splenic HSPC and tumor MDSC functions, thereby contributing to the systemic normalization of antitumor immunity.

Currently, it is evident that MDSCs are crucial regulators of tumor immunity and cancer progression (Kramer and Abrams, 2020; Strauss et al., 2021; Veglia et al., 2018; Wu et al., 2020b). Restraining or redirecting the process of myeloid cell generation is emerging as a promising novel strategy for immunotherapy (Kaczanowska et al., 2021; Lin et al., 2021; Tzetzo and Abrams, 2021; Yu et al., 2021). These therapies could target the driving events in the following two partially overlapping phases: (1) the expansion and preconditioning of precursors and (2) the pathological activation of immature myeloid cells (Condamine et al., 2015; Veglia et al., 2021). Recent studies have demonstrated that the selective targeting of second-phase signals, such as acid transport protein 2 (Veglia et al., 2019), Tollip (Zhang et al., 2019), TNF-α–induced protein 8-like 2 (Yan et al., 2020), and PERK (Mohamed et al., 2020) reverses MDSC polarization in the TME and reduces tumor growth. Considering the short lifespan of MDSCs in tissues and the limited drug accessibility to the tumor, approaches targeting MDSC precursor cell expansion and preconditioning in peripheral organs may be therapeutically more consistent and efficient (Veglia et al., 2021), but such strategies are currently less appreciated, partially because of the unclear nature of the specific mechanism. In addition to a recent study that detected PERK activity in mature myeloid cells in the tumor, our present study revealed that PERK signaling also occurs in the HSPCs located in the spleen of tumor-bearing mice and cancer patients. Delivering PERK inhibitors to the spleen was more effective at repolarizing tumor-MDSCs and reshaping the TME than tumor-targeted PERK blockade. This finding was further supported by the observation that systemic PERK blockade had a limited antitumor effect in splenectomized mice. In addition, the in vitro experiments with both murine and human HSPCs showed that PERK activation in the preconditioning (first) phase of HSPCs was crucial for MDSC generation. Without this priming signal, the descendant immature myeloid cells were unresponsive to TME factors that supposedly trigger secondary PERK signaling to mediate the full suppressive functions of MDSCs. Altogether, these results indicate that the PERK pathway plays a dual role in mediating both the first and second phases of MDSC development, highlighting that such signaling is a valuable target for redirecting and normalizing the systemic myeloid response.

Robust ER stress responses have been observed in many types of human cancers (Cubillos-Ruiz et al., 2017). Activation of UPR pathways not only endows malignant cells with greater tumorigenic, metastatic, and drug-resistant capacities, but also regulates immune cell function in the TME (Cao et al., 2019; Cubillos-Ruiz et al., 2015; Hicks et al., 2021; Thevenot et al., 2014). Although most of these activities have been found in the tumor, we herein report a novel mechanism by which ER stress responses remotely regulate the TME by modulating hematopoietic output in the spleen. This response was triggered by splenic stromal cells that induced PERK–eIF2α–ATF4 signaling in splenic HSPC. The transcription factor C/EBPβ was then activated, and endogenous GM-CSF expression was upregulated, which in turn drove self-feedback–based emergency myelopoiesis and skewed differentiation toward immunosuppressive myeloid cell generation. Lineage-tracing experiments revealed that these myeloid cells generated in the spleen exhibited profoundly more potent immunosuppressive capability than BM-derived myeloid cells. Therefore, our findings identify abnormal ER stress responses as critical regulators of cancer-associated splenic myelopoiesis that is crucial for the generation of tumor-promoting myeloid suppressor cells.

Our findings also suggest a need to reexamine the role of HSPC preconditioning under pathological immune stress and its effect on descendant myeloid cell function. Like PERK, many genes and pathways have been implicated in regulating multiple steps of the myelopoiesis process, but our current knowledge of the exact mechanism is limited. Myeloid cell studies rely on conditional knockout models in which a gene of interest is deleted in cells expressing myeloid lineage–specific genes such as Lyz2 or Csf1r, but recent reports have revealed that these genes are also highly expressed in subsets of myeloid-biased HSPCs (Han et al., 2016; Izzo et al., 2020; Kwok et al., 2020; Mossadegh-Keller et al., 2013). Conversely, gene deletion in HSPCs (e.g., using Vav1-Cre or Tek-Cre mice) eliminates the target gene not only in HSPCs but also in their myeloid descendants and probably the lymphoid and some nonhematopoietic cell types. Therefore, isolating the effects of these genes on different phases of cell development and activation in vivo is still difficult (Zhao et al., 2014). Here, we took advantage of the different locations where these events occur. An organ-targeted drug delivery system was used in combination with in vitro studies to determine the location- and phase-dependent effects of PERK blockade. Although these results are supported by gene-edited HSPC transplantation experiments, new technologies that allow knockout of a gene in progenitors while reactivating it in progenies would more clearly define the differential roles for the PERK activations in different phases of MDSC generation in vivo.

In conclusion, this work highlights that PERK signaling reprograms splenic HSPCs to commit to MDSC development and provides insight into the site-specific characteristics of HSPC functional preconditioning in cancer. Targeting this signaling pathway may provide novel opportunities to normalize antitumor immune environments by selectively redirecting tumor-promoting myeloid responses at their source.

Materials and methods

Mice

All mice were maintained under specific pathogen–free conditions in the animal facilities of Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center (Guangzhou, China). WT C57BL/6 mice (6–8 wk of age, GDMLAC87) were purchased from Guangdong Medical Laboratory Animal Center. Non-obese diabetic/severe combined immunodeficiency mice (6–8 wk of age, T001492) and B6/JGpt-Rosa26em1Cin (CAG-cas9-tdTomato)/Gpt (Cas9-tdTomato, T004285) mice were purchased from GemPharmatech. Tg(CAG-KikGR)33Hadj (KikGR; 013753B6, RRID: IMSR_JAX:013753) mice, SJL-Ptprca Pepcb/BoyJ (CD45.1+; 002014, RRID: IMSR_JAX: 002014) mice, heterozygous C57BL/6J-ApcMin/J (ApcMin/+; 002020, RRID: IMSR_JAX: 002020) mice, and C57BL/6-Tg(CAG-EGFP)1Osb/J (EGFP+; JAX:003291, RRID:IMSR_JAX:003291) mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. The animal experimental protocols were performed according to state guidelines and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Sun Yat-sen University.

Human materials

All human studies were approved by the Review Board of Sun Yat-Sen University. All samples were coded anonymously in accordance with local ethical guidelines (as stipulated by the Declaration of Helsinki). Written informed consent was obtained from the patients, and the protocol was approved by the institutional review board of Sun Yat-sen University. Human umbilical CB samples were obtained from the First Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-Sen University (Guangzhou, China). Paraffin-embedded human spleen tissue sections were obtained from the Sun Yat-Sen University Cancer Center and the Third Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-Sen University (Guangzhou, China). The details of the patient information are provided in Table S4.

Cell lines

The Hepa1-6 cell line (CRL-1830, RRID: CVCL_0327, American Type Culture Collection) was used to establish the orthotopic tumor models. The LLC cell line (CRL-1642, RRID: CVCL_4358, American Type Culture Collection) was used to establish the subcutaneous tumor models. These cell lines were tested and determined to be free from mycoplasma contamination. Luciferase-expressing Hepa1-6 cells were established by transfecting the cells with a pCDH-MCS-T2A-copGFP-MSCV lentivirus (CD523A-1; System Biosciences) expressing GFP and luciferase. Hepa1-6 cells were cultured in DMEM (12100046; Thermo Fisher Scientific), supplemented with 10% FBS (10099141; Thermo Fisher Scientific), and maintained at 37°C in a 5% CO2 humidified atmosphere.

Tumor models and treatments

The orthotopic hepatic tumors were established as previously described (Wu et al., 2018). Briefly, 7.5 × 105 Hepa1-6 tumor cells were suspended in 25 μl of 50% basement membrane extract (3432-005-01; Trevigen) and injected into the left liver lobes of anesthetized mice (6–8 wk of age). Mice bearing luciferase-expressing Hepa1-6 tumors were injected i.p. with a single dose of 75 mg/kg D-luciferin (2779; Biovision) to monitor orthotopic tumor growth; the mice were anesthetized, and the tumors were imaged with an Xenogen in vivo imaging system (IVIS; PerkinElmer). In the chemically induced hepatoma model, C57BL/6 mice received a single dose of DEN (1 mg/kg, i.p.; B40334; Sigma-Aldrich) at 2 wk of age. Beginning at 8 wk of age, CCl4 (0.2 ml/kg i.p. in olive oil) was administered twice per week for ≤14 wk. Age-matched C57BL/6 mice receiving only CCl4 were used as noncancerous controls. The mice were sacrificed at 10 mo of age. The subcutaneous lung carcinoma model was established in C57BL/6 mice by injecting 3 × 105 LLC cells into the right flanks of the mice. Female ApcMin/+ mice spontaneously developed intestinal adenomas by 15–17 wk. For systemic PERK inhibitor treatment, the mice received a dose of 25 mg/kg GSK (HY-18072; MedChemExpress), 12 mg/kg AMG (HY-12661A; MedChemExpress), or vehicle (100 μl of 0.5% hydroxypropyl methylcellulose and 0.1% Tween 80 in sterile water) by oral gavage once or once per day for a total of 14 d. For XBP1 inhibitor treatment, 4µ8C (HY-19707; MedChemExpress) was administered i.p. at a single dose of 25 mg/kg, and the control mice were treated with vehicle alone (0.1% DMSO in PBS).

Continuous delivery of PERK inhibitors into the mouse spleen or tumor site

Micro-osmotic pumps (model 1002; Alzet) were loaded with 0.7 mg of GSK (HY-18072; MedChemExpress), 0.35 mg of AMG (HY-12661A; MedChemExpress), or vehicle (saline solution containing 10% DMSO), unless indicated otherwise. The pumps were preincubated for 24 h in a saline solution at 37°C to ensure the immediate delivery of drugs after implantation. Loaded micro-osmotic pumps with jugular catheters were implanted subcutaneously at the dorsum of the neck of the C57BL/6 mice; then, the tips of the jugular catheters (0007700; Alzet) were inserted into the subcapsular area of the spleen, the liver hepatoma, or the subcutaneous LLC tumor. The drugs were delivered at a rate of 0.25 μl/h. All drugs were dissolved in saline solution containing 10% DMSO, and micro-osmotic pumps containing saline solution with 10% DMSO were implanted in the control (vehicle) group.

Detection of the AMG concentration in mouse organs

Hepa mice received AMG treatment via pump (21 μg/d) or oral gavage (12 mg/kg per day). After 2 wk, the serum, liver tumor, and spleen were removed from five mice, pooled, and stored in liquid nitrogen until use. The concentrations of AMG in the serum, spleen, and liver tumor were measured using ultraperformance liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry (UPLC–MS/MS) in multiple reaction monitoring mode. Data were analyzed with Analyst v1.6.2 software in quantitative mode.

Splenectomy

Splenectomy was performed as previously described (Wu et al., 2018). Briefly, under anesthesia, the abdominal cavity of the mice was opened, the splenic vessels were cauterized, and the spleen was carefully removed. In the sham surgery, the abdomen was opened, but the spleen was not removed.

Splenic myeloid cell adoptive transfer

For this experiment, 107 EGFP+Gr-1+ cells were isolated from the spleen of EGFP+ Hepa-bearing mice that received vehicle or AMG treatment by oral gavage. Afterward, these cells were injected i.v. into the EGFP− splenectomized Hepa-bearing mice. After 24 h, the tumors were harvested from the host, and the EGFP+ (donor-derived) and EGFP− (host-derived) CD11b+Gr-1high PMN-like cells were purified using FACS and tested for their immunosuppressive effect on anti-CD3/28 antibody–stimulated CD8+ T cell proliferation.

Photoconversion and lineage tracing

Lineage tracing experiments were performed using KikGR mice as previously described (Shand et al., 2014). Briefly, the spleen or femur was exposed during surgery and irradiated with a 405-nm violet spot-LED (CGD-F45-1; Cousz). The parameters for spleen and femur photoconversion were three sides for 3 min at 150 mW/cm2 and 5 min at 500 mW/cm2, respectively. After 16 h, the tumors were harvested, and the RFP+ PMN-like cells were purified using FACS and tested for their immunosuppressive activity.

Cell isolation and flow cytometry

Mouse femurs and tibias were isolated, and the BM cells were flushed out by using an injection syringe loaded with FACS buffer (1% FBS and 2 mM EDTA in PBS) to obtain single-BM-cell suspensions. The spleens were removed, homogenized in FACS buffer, and passed through a 38-μm filter. RBCs were lysed, and cells were washed to isolate splenocytes. Then the splenocytes were resuspended in FACS buffer. The tumor-infiltrating immune cells were isolated by dissecting the Hepa1-6 orthotopic tumors, mincing them into small pieces with fine scissors, and digesting the tissue in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 50 μg/ml collagenase IV (C5138; Sigma-Aldrich), 50 μg/ml DNase I (D5025; Sigma-Aldrich), 50 μg/ml hyaluronidase (H3884; Sigma-Aldrich), and 15% FBS (Thermo Fisher Scientific) at 37°C and 750 rpm for 40 min. The cells were passed through a 38-μm filter, followed by RBC lysis, washing, and resuspension in FACS buffer.

Flow cytometry was performed as previously described (Wu et al., 2018). For the analysis of murine HSPCs, 5 × 106 BM cells or 1 × 107 splenocytes were suspended in 100 μl FACS buffer and stained with lineage antibody cocktails (BD Bioscience) and antibodies against CD45 (30-F11), c-Kit (2B8), Sca1 (D7), CD16/32 (2.4G2), CD34 (RAM34), CD135 (A2F10), CD48 (HM48-1), and CD150 (TC15-12F12.2). LSK cells were identified as linlow/− Sca1+c-Kithigh, long-term HSCs as linlow/−Sca1+c-KithighCD135−CD150+CD48−, short-term HSCs as linlow/−Sca1+c-KithighCD135−CD150−CD48−, MPP2 cells as linlow/−Sca1+c-KithighCD135−CD150+CD48+, MPP3 cells as linlow/−Sca1+c-KithighCD135−CD150−CD48+, MPP4 cells s linlow/−Sca1+c-KithighCD135+CD150−CD48+, LK cells as linlow/−Sca1−c-Kithigh, and GMPs as linlow/−Sca1−c-KithighCD16/32highCD34+. For the murine mature immune cell analysis, monoclonal antibodies against anti-CD45 (30-F11), CD3 (17A2), CD8 (53-6.7), B220 (RA3-6B2), CD11b (M1/70), Gr-1 (RB6-8C5), Ly6G (1A8), Ly6C (AL-21), F4/80 (BM8), and NK1.1 (S17016D) were used. PMN-like cells were identified as CD45+CD11b+Gr-1highLy6G+Ly6Clow, monocytic cells as CD45+CD11b+Gr-1intLy6G−Ly6Chigh, F4/80+ macrophages (Mφs) as CD45+CD11b+Gr-1−F4/80+, CD3+ T cells as CD45+CD3+B220−CD11b−, and B220+ B cells as CD45+CD3−B220+CD11b−. For the human CB-HSPC analysis, monoclonal antibodies, including lineage cocktail (BD Bioscience), CD45 (2D1), CD34 (581), CD38 (HIT2), CD123 (7G3), and CD45RA (HI100), were used. HSC/MPPs were identified as CD45+linlow/−CD34+CD38−, GMPs as CD45+linlow/−CD34+CD38−CD123+CD45RA+, common myeloid progenitors (CMPs) as CD45+linlow/−CD34+CD38−CD123+CD45RA−, and MEPs as CD45+linlow/−CD34+CD38−CD123−CD45RA−. For the apoptosis analysis, freshly isolated cells were suspended in Annexin V binding buffer. The cells were stained with Annexin V (556419; BD Bioscience) along with antibodies against surface markers and analyzed in Annexin V binding buffer. For intracytoplasmic IFN-γ detection, T cells were stimulated with RPMI 1640 (31800089; Thermo Fisher Scientific) supplemented with 10% FBS (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and 0.5% leukocyte activation cocktail (550583; BD Pharmingen) at 37°C for 4.5 h. For intracytoplasmic GM-CSF detection, c-Kit+ or lin− HSPCs were stimulated with serum-free medium (StemSpan SFEM; 09650; Stem Cell Technologies) supplemented with 50 ng/ml stem cell factor (SCF; 250-03; PeproTech) and 0.5% leukocyte activation cocktail (BD Pharmingen) at 37°C for 6 h. After in vitro stimulation, the cells were stained with antibodies against surface markers, fixed, permeabilized using a Fixation/Permeabilization Solution Kit (554714; BD Cytofix/Cytoperm), and stained with antibodies against IFN-γ or GM-CSF. Detailed descriptions of the antibodies used for flow cytometry are provided in Table S5. Data were acquired on a Cytoflex S flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter) and analyzed with Kaluza Analysis (Beckman Coulter) and FlowJo software (TreeStar).

For the isolation of HSPCs, linlow/− and c-Kit+ cells were first sorted by magnetic-activated cell sorting (MACS) using a lineage Cell Depletion Kit (130-090-858; Miltenyi Biotec) and CD117 microbeads (130-091-224; RRID: AB_2753213; Miltenyi Biotec), respectively. The LSK cells were purified using a MoFlo XDP or MoFlo Astrios EQ flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter). For isolation of the myeloid cells, Gr-1+ cells were first sorted by MACS using a biotin-conjugated anti–Gr-1 antibody (108404; RRID: AB_313368; BioLegend), followed by anti-biotin microbeads (130-090-485; RRID: AB_244365; Miltenyi Biotec); the CD11b+Gr-1highLy6G+Ly6Clow PMN-like cells were purified using FACS. To isolate the splenocyte subsets, the splenic cells were isolated using an enzyme-based digestion method. RBCs were lysed, and the Ter-119+ cells, CD3+/B220+ lymphocytes, Gr-1+ cells, and Gr-1−Ter-119−CD45−CD117− splenic stromal cells were first enriched through MACS using biotin-conjugated antibodies (BioLegend) and anti-biotin microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec). The CD45−Ter-119+ Ter-cells, CD3+/B220+ lymphocytes, CD11b+Gr-1highLy6G+Ly6Clow PMN-like cells, CD45+CD11b+Gr-1intLy6G−Ly6Chigh monocytic cells, lin−Ter-119−CD45−CD117− splenic stromal cells, and CD11b−Gr-1−NK1.1+ NK cells were purified by FACS using a MoFlo XDP or a MoFlo Astrios EQ flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter). The purity of the sorted cell populations was evaluated by flow cytometry and exceeded 90% (MACS) or 98% (FACS).

IB

For the IB assay, 1 × 104 LSK cells or 2 × 105 splenocytes were washed once with RPMI with 0.1% phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (A100754; Sangon Biotech), and the supernatant was carefully removed by using a 200-μl tip. The cell pellet was lysed in 10 μl of lysis buffer (62.5 mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 2% [wt/vol] SDS, 10% [wt/vol] glycerol, 50 mM dithiothreitol, and 0.01% [wt/vol] bromophenol blue in ultrapure water) on ice. Equal amounts of cellular proteins were separated on 10% SDS-PAGE gels, immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies, and visualized using the SuperSignal West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate (34580; Thermo Fisher Scientific). The primary antibodies used for IB were as follows: β-actin (AC-15; BM5422; Boster Biological Technology); BIP (C50B12; 3177, RRID: AB_2119845; Cell Signaling Technology); t-PERK (C33E10; 3192, RRID: AB_2095847; Cell Signaling Technology); p-PERK (16F8; 3179, RRID: AB_2095853; Cell Signaling Technology); p-eIF2α (119A11; 3597, RRID: AB_390740; Cell Signaling Technology); ATF4 (D4B8; 11815, RRID: AB_2616025; Cell Signaling Technology); XBP1-S (E9V3E; 40435, RRID: AB_2891025; Cell Signaling Technology); C/EBPβ (#3087; 3087, RRID: AB_2078052; Cell Signaling Technology) for LAP; C/EBPβ (1H7; ab15050, RRID: AB_301598; Abcam) for LAP*/LAP/LIP; and CHOP (L63F7; 2895, RRID: AB_2089254; Cell Signaling Technology).

RNA extraction and quantification

In total, 104–105 FACS-sorted BM or splenic LSK cells from the control or tumor-bearing mice were lysed and homogenized in Buffer RTL supplied in a RNeasy micro kit (74004; Qiagen). The cell lysis buffer was frozen at −80°C until the RNA extraction. The total RNA was extracted according to the manufacturer’s instructions and eluted in a total volume of 12 μl. The RNA was quantified using epoch (Biotek) or Qbit assays (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Quantitative RT-PCR

Eluted RNA was used to generate cDNAs with All-in-One RT Master Mix (G492; Applied Biological Material). The target genes were evaluated using TaqMan gene expression assays (4444963; Thermo Fisher Scientific). The assay IDs of the target genes were as follows: Hspa5 (4331182; Assay ID: Mm00517691_m1), Eif2ak3 (4331182; Assay ID: Mm00438700_m1), Ddit3 (4331182; Assay ID: Mm01135937_g1), Atf6 (331182; Assay ID: Mm01295319_m1), and Actin (4331182; Assay ID: Mm01205647_g1). All reactions were conducted using a LightCycler 480 Instrument (Roche) in triplicate.

Xbp1-splicing assay

The Xbp1 splicing assays were performed by using conventional RT-PCR and the following primers: Xbp1 splicing, 5′-GGTCTGCTGAGTCCGCAGCA-3′ (forward) and 5′-AAGGGAGGCTGGTAAGGAAC-3′ (reverse); Actb, 5′-CCAGGTCATCACTATTGGCAAC-3′ (forward) and 5′-TACGGATGTCAACGTCACAC-3′ (reverse).

Transmission EM

Pellets containing 1.5 × 105 sorted LSK cells were fixed with isoamyl alcohol for 24 h and embedded in low-gelling-temperature agarose (Sigma-Aldrich). Ultrathin sections (100-nm thick) were collected using 200-mesh copper grids, stained with Reynold’s lead citrate, and carbon coated. The grids of the sections were viewed under a JEM-1400 electron microscope (JEOL). At least 100 cells per section were imaged, and in total, five sections were analyzed per sample. The presence and degree of ER dilation were assessed as previously described (Condamine et al., 2014). The criteria were as follows: (1) cells without dilated ER segments were classified as negative; (2) cells containing dilated ER segments in up to one third of the cytoplasm area were classified as mild; (3) cells containing dilated ER segments in more than one third and up to two thirds of the cytoplasm area were classified as moderate; and (4) cells containing dilated ER segments in more than two thirds of the cytoplasm area were classified as grave.

scRNA-seq and data processing

LSK cells from the BM and spleen of the Hepa mice were isolated and purified by FACS. Then, the cells were processed for scRNA-seq using a Chromium Single Cell 3′ Library & Gel Bead Kit v3 (PN-1000092; 10x Genomics) following the manufacturer’s protocol. The samples were sequenced at an average of 27,000 reads per cell. The resultant scRNA-seq reads were aligned to the GRCm38 (mm10) reference genome and quantified using cellranger count (Cell Ranger pipeline v3.1.0; 10x Genomics). Cell barcodes with unique molecular identifiers <500, mitochondrial gene percentage >10%, or >1% hemoglobin expression were filtered. After the filtering, we obtained a total of 10,088 BM LSK cells and 6,546 SP LSK cells. The cells showed 9,600 ± 65 (mean ± SEM) unique molecular identifiers per cell, and an average of 2,864 ± 9 (mean ± SEM) genes were detected across all cells. The data were first normalized by deconvolution using the calculateSumFactors function in the R package scran. The data integration and technical variation were performed using the SCTransform command in the Seurat package (v.3.1.5).

Dimension reduction and unsupervised clustering

Once the data were successfully integrated, we performed data dimensionality reduction with principal component analysis. The first 30 principal components were used for the Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP) reduction and defining the cell clusters. The cluster identities were manually assigned and curated based on gene expression correlated with the single-cell Mouse Cell Atlas dataset using the scMCA package (Han et al., 2018) and the expressed genes previously reported (Izzo et al., 2020). The reference annotations of the cell types are shown in Table S1.

Cluster marker gene identification and gene module score calculation

To identify the cell cluster marker genes that are conserved in both BM and splenic LSK cells, we used the FindConservedMarkers function in the Seurat package. The supervised module scores of the gene sets related to early myeloid differentiation (Izzo et al., 2020) and the ER stress response (GO:0034976) were calculated using the AddModuleScore function in the Seurat package.

Single-cell trajectory and pseudotime analysis

The 3D LSK cell trajectory was constructed using the Monocle 3 package. To place the cells in order along the trajectory, we defined a “root” node in the HSC-1 cluster upstream of the divergence of branches toward MP, dendritic cell progenitor, and mast cell progenitor. Pseudo-time was estimated using the order_cells function in the Monocle 3 package.

BrdU incorporation assay

To analyze the cell cycle of the HSPCs, the mice received a single dose of systemic treatment with a PERK inhibitor (GSK, 25 mg/kg), XBP1 inhibitor (4µ8C, 25 mg/kg), or vehicle. After 7 h, the mice were injected with a single dose of BrdU (1 mg per 6 g body weight; B5002; Sigma-Aldrich). After a 5-h pulse, the c-Kit+ HSPCs were isolated from the BM and spleen by MACS and stained with antibodies against surface markers. For cell cycle analysis of human CB-HSPCs, the cultured CD38− CB-HSPCs were purified by FACS and then cultured with 5 μM BrdU. After a 30-min pulse, the cells were stained with antibodies against surface markers. The cells were fixed, permeabilized, and stained for BrdU using a FITC BrdU Flow Kit (557891; BD Pharmingen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. DAPI (D1306; Thermo Fisher Scientific) was added to the FACS buffer at a concentration of 3 μg/ml to detect the DNA content.

LSK cell adoptive transfer

In total, 1 × 105 CD45.1+CD45.2− BM LSK cells were pretreated with vehicle (0.1% DMSO), GSK (250 nM), or 4μ8C (10 μM) for 2 h; in some experiments, 1 × 105 EGFP+ BM LSK cells were transfected with or without control or PERK siRNAs. Afterward, these cells were resuspended in 30 μl of HBSS and injected into the spleen subcapsular area of recipient control or Hepa CD45.1−CD45.2+ mice. After 2 d, the splenocytes were harvested from the recipients and analyzed by flow cytometry. CD45.1+CD45.2−CD11b+Gr-1+ or EGFP+ CD11b+Gr-1+ donor-derived myeloid cells were sorted using FACS and tested for their immunosuppressive effect on anti-CD3/28 antibody-stimulated CD8+ T cell proliferation.

Murine cell culture

LSK cells were cultured in IMDM (12200036; Thermo Fisher Scientific) supplemented with 10% FBS (Thermo Fisher Scientific), 20 ng/ml SCF (250-03; PeproTech), 20 ng/ml thrombopoietin (TPO; 315-14; PeproTech), and 100 ng/ml Flt3-L (250-31L; PeproTech). For the coculturing of the LSK cells with other cell populations, 5 × 104/ml naive BM LSK cells were cocultured with 5 × 104/ml stromal cells, lymphocytes, myeloid cells, or Ter cells in the above complete medium for 4 d. To induce LSK cells with splenic SSN stimulation, SSNs were harvested from a 48-h culture of 5 × 106/ml stromal cells in RPMI 1640 (31800089; Thermo Fisher Scientific) supplemented with 10% FBS. SSN was used at a final concentration of 5% to stimulate the LSK cells. In some experiments, the LSK cells were first incubated with the indicated concentration of PERK inhibitors (GSK, 250 nM; AMG, 5 μM) or 10 μM STAT3 inhibitor (AG490; S1143; Selleck) in complete IMDM for 2 h, and SSN was added for subsequent culture. In some experiments, anti-mouse IL-6 (1 μg/ml; 16-7061; RRID: AB_2866219; Thermo Fisher Scientific) or equal amounts of corresponding isotype control Abs were added to the cultures. To assess the ability of the HSPCs to produce immunosuppressive myeloid descendant cells, the LSK cells were cultured for another 4–5 d in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FBS and 50 ng/ml SCF (PeproTech). Subsequently, Gr-1+ myeloid descendant cells were isolated using FACS and tested for their suppressive function in anti-CD3/28 antibody-stimulated CD8+ T cell proliferation and/or antigen-specific tumor cell killing. The cells were cultured at 37°C in a 5% CO2 humidified atmosphere.

Measurement of protein synthesis