Abstract

Background

Rituximab and tacrolimus are therapies reserved for patients with frequently relapsing or steroid-dependent nephrotic syndrome who have failed conventional steroid-sparing agents. Given their toxicities, demonstrating non-inferiority of rituximab to tacrolimus may enable choice between these medications.

Methods

This investigator-initiated, single-center, open-label, pilot randomized controlled trial examined the non-inferiority of two doses of intravenous (IV) rituximab given one-week apart to oral therapy with tacrolimus (1:1 allocation), in maintaining sustained remission over 12 months follow-up, in patients with difficult-to-treat steroid-sensitive nephrotic syndrome, defined as frequently relapsing or steroid-dependent disease that had failed ≥ 2 steroid-sparing strategies. Secondary outcomes included frequency of relapses, proportion with frequent relapses, time to relapse and frequent relapses, and adverse events (CTRI/2018/11/016342).

Results

Baseline characteristics were comparable for 41 patients randomized to receive rituximab (n = 21) or tacrolimus (n = 20). While 55% of patients in each limb were in sustained remission at 1 year, non-inferiority of rituximab to tacrolimus was not demonstrated (mean difference 0%; 95% CI – 30.8%, 30.8%; non-inferiority limit – 20%; P = 0.50). Frequent relapses were more common in patients administered rituximab compared to tacrolimus (risk difference 30%, 95% CI 7.0, 53.0, P = 0.023). Both groups showed similar reductions in relapse rates and prednisolone use. Common adverse events were infusion-related with rituximab and gastrointestinal symptoms with tacrolimus.

Conclusions

Therapy with rituximab was not shown to be non-inferior to 12-months treatment with tacrolimus in maintaining remission in patients with difficult-to-treat steroid-sensitive nephrotic syndrome. Frequent relapses were more common with rituximab. While effective, both agents require close monitoring for adverse events.

Graphical abstract

A higher resolution version of the Graphical abstract is available as Supplementary information.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00467-022-05475-8.

Keywords: Children, Frequently relapsing nephrotic syndrome, Rituximab, Tacrolimus, Steroid dependence

Introduction

Approximately 40–50% of patients with steroid-sensitive nephrotic syndrome have frequently relapsing or steroid-dependent disease. These patients are considered for therapy with steroid-sparing agents because of the morbidities associated with relapses and the risk of corticosteroid toxicity [1]. While the recent Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) clinical practice guidelines suggest levamisole or cyclophosphamide as preferred agents in patients with frequent relapses, they advise that the choice of the glucocorticoid-sparing agent in steroid dependence should be guided by patient and physician preference, likely adherence to therapy, and adverse effects, costs and availability of the medication [2]. In many regions of the world, patients with frequent relapses or steroid dependence usually receive initial therapy with prednisone on alternate days, cyclophosphamide, levamisole, and/or mycophenolate mofetil (MMF), failing which they are considered difficult-to-treat, and managed with either calcineurin inhibitors (CNI) or intravenous (IV) rituximab [1].

Therapy with ciclosporin or tacrolimus sustains satisfactory remission in the majority, but is reserved for later considering the risks of nephrotoxicity and metabolic adverse events [3]. Likewise, while B-lymphocyte depletion enables significant steroid-sparing and sustained remission for 6–15 months, rituximab therapy is associated with the risk of infusion reactions and hypogammaglobulinemia, particularly in young children [3]. Given a choice, physicians and parents prefer rituximab to CNI in patients with difficult-to-treat disease because of its perceived safety and ease of adherence to therapy. Evidence to guide this decision for patients with steroid-sensitive disease is limited to one retrospective series [4] and a single-center randomized controlled trial (RCT) [5] on patients with mild disease, and show conflicting results, possibly related to differences in age at therapy and disease severity. Therefore, this pilot RCT was planned to examine the non-inferiority of two doses of IV rituximab to 12 months of therapy with oral tacrolimus in sustaining remission in patients with difficult-to-treat frequently relapsing or steroid-dependent nephrotic syndrome.

Methods

Trial design

This open-label parallel-group pilot non-inferiority RCT was conducted at one center between November 2018 and December 2020. Following approval from the Institute Ethics Committee (IECPG-390/30.08.2018, RT-4/27.09.2018), the trial was registered at the Clinical Trials Registry of India (CTRI/2018/11/016342) and conducted according to the original protocol. The investigators conceived and designed the study and vouch for the accuracy and completeness in collation and analysis of data. This report complies with the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials statements for pilot and non-inferiority RCTs (Online Resource 1) [6, 7].

Patients

Patients, 3–18 year old, with difficult-to-treat steroid-sensitive nephrotic syndrome were eligible if they were in steroid-induced remission following a recent (< 3 months) relapse. Difficult-to-treat disease was diagnosed if each of the following criteria was met: (i) frequent relapses (≥ 2 relapses in 6 months or ≥ 3 relapses per year) or steroid dependence [2, 4], (ii) failure of ≥ 2 strategies (alternate-day prednisolone, levamisole, cyclophosphamide, MMF), and (iii) corticosteroid toxicity (cataract, glaucoma, short stature with low growth velocity [8], or obesity [9]). Patients with known secondary cause, initial or late steroid resistance, prior therapy with rituximab or tacrolimus, estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 [10], seizures, impaired glucose tolerance (fasting glucose > 100 mg/dL or glycosylated hemoglobin, HbA1c > 5.7%) [11], chronic infections (tuberculosis, HIV, hepatitis B or C), < 6 months follow-up at this center, and reluctance to follow for the subsequent 12 months, were excluded.

Randomization

Following informed written consent, eligible patients were randomly assigned in 1:1 ratio in permuted blocks of four, while stratifying for steroid-dependence and age (≤ / > 8 years), to receive either IV rituximab (Mabtas®, Intas Pharmaceuticals, Ahmedabad) at 375 mg/m2 twice, one week apart, or oral tacrolimus (Takfa®, Intas Pharmaceuticals) at 0.1–0.2 mg/kg daily in two divided doses for 1 year. Personnel not caring for these patients used computer-generated random number sequence to prepare strata-wise lists and concealed the allocation in sequentially numbered, opaque sealed envelopes that were opened at randomization. The investigators, patients, and outcome assessors were aware of the therapy being received.

For patients administered rituximab, CD19 + B cells were measured one week after the second dose by flow cytometry (FACS Canto II analyzer, Becton Dickinson, NJ). Patients lacking B cell depletion (CD19 + cells < 1% of CD45 + cells or absolute count < 5 cells/µL) received additional doses of rituximab to a maximum of total four doses. B cell count was repeated at 6 months or at relapse, whichever was earlier, and at 12 months in patients with persistent depletion. B cell repopulation was defined as absolute count > 10 cells/µL [12]; rituximab was not repeated at repopulation. Dosing for tacrolimus was titrated to a 12-h trough level of 4–7 ng/mL, using chemiluminescence microparticle immunoassay. Levels were estimated at 2 weeks after randomization, 6 and 12 months follow-up, at relapse, and 2 weeks after dose titration.

Follow-up

Parents examined the first morning urine using dipstick and recorded details of proteinuria, infections, adverse events, and medication doses in a diary, which was reviewed at each visit, scheduled at 2 weeks, 1, 3, 6, 9, and 12 months, at each relapse, and at diagnosis of treatment failure. Standard deviation scores (SDS) were computed for anthropometric parameters and blood pressure [8, 9, 13]. Compliance to tacrolimus was assessed using history and pill count at each visit. Investigations, at 3-monthly visits, included blood counts, creatinine, electrolytes, transaminases, lipid profile, fasting glucose, and HbA1c. Kidney biopsy was not performed to document tacrolimus-induced nephrotoxicity. During the SARS-CoV2 pandemic, visits were delayed by 2–8 weeks and/or substituted by video teleconsultations, including questions on COVID-19 symptoms, review of anthropometry and investigations done by local physician, and images of diary and pill strips. If required, tacrolimus was supplied at home to ensure adherence.

Co-interventions

Patients in both groups received prednisolone on alternate days (1.5 mg/kg for 4 weeks, tapered by 0.25 mg/kg every 2 weeks), and discontinued at 10–14 weeks. All patients received calcium carbonate (250–500 mg) and vitamin D3 (200–400 IU) daily during steroid therapy. Hypertension was managed with enalapril (0.2–0.5 mg/kg daily), with additional amlodipine as required [13]. Infections were managed as per unit protocols. Relapse (recurrence of 3 + /4 + proteinuria for ≥ 3 days) was treated with prednisolone, at a dose of 2 mg/kg (maximum 60 mg) daily until remission (trace/negative proteinuria for ≥ 3 days), followed by 1.5 mg/kg (maximum dose 40 mg) on alternate days for 4 weeks, before discontinuation.

Outcomes

Primary outcome was the proportion of patients with sustained remission at 1-year follow-up. Secondary outcomes, at 1 year, included the proportions of patients with frequent relapses and treatment failure, frequency of relapses, time to first relapse and to treatment failure, cumulative prednisolone received, frequency and type of adverse events, and change in anthropometric and blood pressure SDS. Adverse events, assessed based on clinical and laboratory evaluation at each visit, were reported using the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) version 5.0 [14]. All SAE (serious adverse events) were reported to the Ethics Committee within 48 h. Causality of adverse events was attributed according to the World Health Organization Uppsala Monitoring Center system [15]. Treatment failure was the occurrence of frequent relapses, late steroid resistance, CTCAE grade 4–5 adverse event related to intervention or corticosteroids, or ≥ 2 SAE related to disease or intervention. Study participation was terminated at treatment failure and the patients managed at physicians’ discretion. All other patients were followed in the study for 1 year.

Statistical analysis

Continuous data is presented as median (interquartile range, IQR) and compared between and within groups using rank sum or sign rank tests, respectively. Categorical data is presented as percentages or frequencies with estimates of 95% CI and analyzed by chi-square or Fisher exact test. Frequency of relapses is presented as incidence density per person-year with 95% CI. Kaplan–Meier curves with the logrank test were used to estimate and compare the time to events between groups. Exploratory post hoc subgroup analysis compared outcomes in patient categories based on stratifying variables and sex. Statistical significance for primary and secondary outcomes in this non-inferiority trial was set at P < 0.025 (one-sided) and < 0.05, respectively, except for subgroup analysis, where Bonferroni correction was applied. Data was analyzed using Stata 14.0 (2015; StataCorp, College Station, Texas). Fragility index was the number of individuals whose endpoint status required to change for the result to lose statistical significance [16]. Modified intention-to-treat analysis included all patients who received at least one dose of either intervention following randomization. In patients lost to follow-up, efficacy was estimated based on last available observation. Per-protocol analysis excluded patients who missed a dose of rituximab or did not comply with the advised dose of tacrolimus for a cumulative period of > 3 weeks.

Previous studies indicate sustained remission in 50–90% of patients with difficult-to-treat steroid-sensitive disease treated with CNI or two doses of rituximab [3–5]. Assuming that 60% of such patients will maintain remission over 1 year after either intervention, at 90% power, 5% alpha error, a non-inferiority margin of 20%, and assuming loss to follow-up of 10%, 114 patients were required per group to demonstrate non-inferiority of rituximab over tacrolimus. The feasibility of this sample size in a single-center study was limited while enrolling selected patients with difficult-to-treat steroid-sensitive disease. Hence, participant enrolment in this pilot study was limited to 20 patients per limb.

Results

Participants

We screened 108 patients with frequent relapses or steroid dependence who had failed two or more strategies, and showed corticosteroid toxicity. Of 41 patients with difficult-to-treat steroid-sensitive disease who were randomized (Fig. 1), 21 were allocated to receive IV rituximab and 20 to oral tacrolimus. Modified intention-to-treat population included 40 patients; one patient assigned to rituximab did not return after randomization. No other patient was lost to follow-up. Baseline characteristics were similar for patients in the two groups (Table 1). The median disease duration exceeded 5 years. The majority of patients had steroid-dependent disease. Approximately 80% of patients each had failed therapy with prednisolone on alternate days, levamisole and cyclophosphamide, and a quarter in each group had also failed MMF (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Patient flow. Modified intention-to-treat population excluded one patient who did not return to receive IV rituximab after randomization. Per-protocol analysis excluded this patient and 5 patients with non-compliance to tacrolimus for > 3 weeks

Table 1.

Patient characteristics at randomization

| Rituximab (n = 21) | Tacrolimus (n = 20) | |

|---|---|---|

| Boys | 15 (71.4) | 19 (95) |

| Age, months | 109 (85, 130) | 120 (87.5, 170.5) |

| Steroid-dependence | 15 (71.4) | 15 (75) |

| Standard deviation scores (SDS) | ||

| Weight | 0.27 (–0.50, 1.00) | –0.09 (–1.21, 0.44) |

| Height | –1.07 (–1.83, –0.73) | –1.49 (–1.98, –0.93) |

| Body mass index | 1.11 (0.62, 1.82) | 0.84 (–0.23, 1.39) |

| Systolic blood pressure | 1.76 (0.89, 2.34) | 1.61 (1.25, 2.33) |

| Diastolic blood pressure | 1.48 (1.00, 2.12) | 1.56 (1.03,2.13) |

| Estimated GFR, mL/min per 1.73 m2 | 140.4 (123.1, 151) | 146.6 (119.6, 152) |

| Serum albumin, g/dL | 3.9 (3.4, 4.1) | 4.1 (3.4, 4.3) |

| Past history | ||

| Age at onset of nephrotic syndrome, months | 38 (27, 55) | 37 (24.5, 57.5) |

| Age at frequent relapses, months | 64 (34,78) | 52.5 (36.5, 73) |

| Duration of disease, months | 63 (46, 91) | 74 (40.5, 102) |

| Time since last relapse, months | 1.0 (0.47, 1.50) | 1.52 (0.75, 1.88) |

| Prior therapies | ||

| Long-term alternate day prednisolone | 17 (81.0) | 16 (80.0) |

| Levamisole | 18 (85.7) | 16 (80.0) |

| Cyclophosphamide | 16 (76.2) | 17 (85.0) |

| Mycophenolate mofetil | 6 (28.6) | 5 (25.0) |

| More than two therapies | 15 (71.4) | 13 (65.0) |

| Evidence of corticosteroid toxicity | ||

| Short stature*1 | 6 (28.6) | 5 (25.0) |

| Overweight*2/obese*3 | 7 (33.3)/8 (38.1) | 7 (35.0)/5 (25.0) |

| Cataract (n = 39) | 8 (40) | 5 (26.3) |

| Raised intraocular pressure (n = 39) | 5 (25) | 3 (15.8) |

| Two or more toxicities (n = 39) | 17 (85.0) | 15 (78.9) |

| Relapse rates, per person year | ||

| In the preceding year | 4.1 [3.3, 5.1] | 4.7 [3.8, 5.8] |

| In the preceding 6 months | 5.7 [4.4, 7.4] | 6.3 [4.8, 8.1] |

| Cumulative prednisolone dose, mg/kg per day | 0.44 (0.29, 0.68) | 0.43 (0.36, 0.72) |

Continuous variables are presented as median (interquartile range) or mean [95% CI]

GFR glomerular filtration rate

*Defined as 1height < – 2 SDS for age with height velocity < – 3 SDS for age [9]; 2body mass index (BMI) more than equivalent of 23 kg/m2 in adults and 3BMI more than equivalent of 27 kg/m2 in adults[8]

Primary outcome

At 12 months follow-up, 11 (55%) patients in each group were in sustained remission. Non-inferiority of rituximab over tacrolimus was not demonstrated since the lower 95% CI of the risk difference (– 31%) was beyond the pre-specified margin of – 20% (Fig. 2, Table 2).

Fig. 2.

Proportions with sustained remission and treatment failure at 12 months. Point estimates and two-sided 95% confidence intervals (CI) are shown for the treatment effect, defined as the risk difference for each outcome between groups in the intention-to-treat analysis. The non-inferiority margin for rituximab as compared with tacrolimus was − 20 percentage points for the primary outcome. The lower end of the two-sided 95% CI of the risk difference in the primary outcome of sustained remission at 12 months was below – 20 percentage points; P value for non-inferiority of 0.50 did not meet the prespecified alpha level of P < 0.025. Per the statistical analysis plan, no test for non-inferiority was performed for the secondary outcomes of frequent relapses and treatment failure (composite of frequent relapses, late steroid resistance; CTCAE grade 4–5 adverse events related to intervention or corticosteroids; or occurrence of two or more serious adverse events related to disease or intervention) at 12 months

Table 2.

Outcomes at 12 months or at end of study

| Outcome | Rituximab (n = 20) | Tacrolimus (n = 20) | Relative risk or risk ratio | Risk or mean difference | P* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary outcome | |||||

| Proportion in sustained remission | 55 [34.20, 74.19] | 55 [34.20, 74.19] | 1.0 [0.57, 1.75] | 0 [–30.83, 30.83] % | 0.50 |

| Secondary outcomes | |||||

| Proportion with frequent relapses | 35 [17.99, 56.84] | 5 [0.00, 25.41] | 7 [0.95, 51.80] | 30 [7.02, 52.98] % | 0.023 |

| Proportion with treatment failure^ | 35 [17.99, 56.84] | 5 [0.00, 25.41] | 7 [0.95, 51.80] | 30 [7.02, 52.98] % | 0.023 |

| Incident relapse rates, per person-year | |||||

| During the study period | 0.85 [0.49, 1.38] | 0.52 [0.25, 0.95] | 1.65 [0.75, 3.77] | 0.33 [–0.19, 0.86] | 0.22 |

| During first 6 months | 0.30 [0.06, 0.87] | 0.50 [0.16, 1.18] | 0.59 [0.12, 2.57] | –0.20 [–0.76, 0.35] | 0.50 |

| During 6 months to end of study | 1.47 [0.78, 2.52] | 0.53 [0.17, 1.23] | 2.79 [1.02, 8.72] | 0.95 [0.21, 1.87] | 0.045 |

| Cumulative prednisolone dose, mg/kg/day | 0.11 (0.05, 0.24) | 0.11 (0.04, 0.19) | – | –0.08 [–0.19, 0.03] | 0.15 |

Categorical variables are presented as proportion [95% confidence intervals, CI] and continuous variables as median [95% CI] or median (interquartile range)

*One- and two-tailed P reported for primary and secondary outcomes, respectively, with threshold for significance set at 0.025 and 0.05, respectively

^All patients with treatment failure had frequent relapses

Secondary outcomes

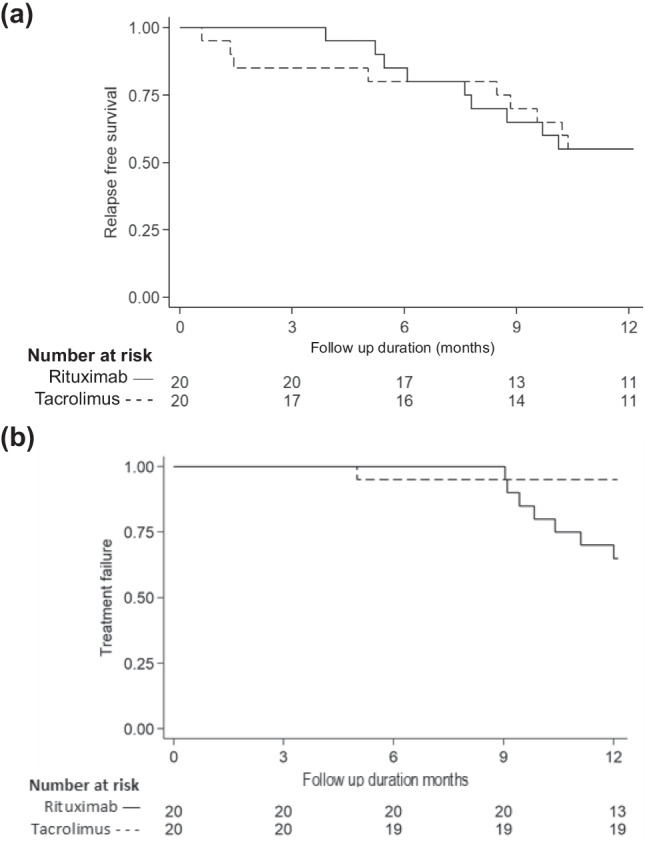

The proportion of patients in sustained remission at 3–12 months follow-up was similar between the groups (logrank P = 0.99; Fig. 3a). Two patients administered rituximab had one relapse each, while seven experienced two relapses within 6 months (frequent relapses) at 4.5–12 months follow-up. Eight patients administered tacrolimus had one relapse each; one patient with frequent relapses also developed late steroid resistance following the second relapse. Frequent relapses were the only cause of treatment failure in either group, making treatment failure significantly more common in the former (risk ratio 7; 95% CI 0.95–51.80; P = 0.023). While treatment failure in the rituximab group occurred beyond 6 months follow-up, the patient receiving tacrolimus failed therapy at 5 months (logrank P = 0.026; Fig. 3b]. The median time to relapse and frequent relapses could not be estimated (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Kaplan–Meier survival analysis for time to (a) first relapse and (b) treatment failure. (a) At 3, 6 and 9 and 12 months of follow-up, the proportions of patients in remission were similar for those receiving rituximab (100%, 85%, 65%, and 55%) and tacrolimus (85%, 80%, 70%, and 55%, respectively) (logrank P = 0.99). The median time to relapse could not be estimated. (b) The proportions of patients with treatment failure (frequent relapses, late steroid resistance; one CTCAE grade 4–5 adverse event or two or more serious adverse events related to disease or intervention) at 3, 6, and 9 months were similar in patients receiving rituximab (0%, 0%, and 10%, respectively) and tacrolimus (5% at each time point). However, compared to tacrolimus, a significantly higher proportion of patients treated with rituximab showed treatment failure at 12 months or end of study (35 versus 5%; logrank P = 0.026). The median time to treatment failure could not be estimated

The incidence density of relapses, based on 16 relapses over 18.8 patient-years in the rituximab group and 10 relapses over 19.4 patient-years in the tacrolimus group, was comparable at 0.85 versus 0.52 relapses per person-year, respectively (Table 2). Within groups, the incidence of relapses declined by mean (95% CI) 3.3 (2.3–4.3) and 4.2 (3.2–5.2) relapses per patient-year in patients receiving rituximab and tacrolimus, respectively (both P < 0.0001). The cumulative prednisolone received was similar between the groups (Table 2).

Although there were significant improvements from baseline in anthropometric and blood pressure SDS, there were no significant between-group differences at end of study (Online Resource 2). While eGFR was comparable between groups at the end of study, therapy with tacrolimus was associated with decline in eGFR by median 19 (IQR – 5, 39) mL/minute/1.73 m2.

Adverse events

Online Resource 3 depicts adverse events observed during the study. Minor infections, accounting for one-third of events, were comparable between the groups. No patients had symptoms of, or tested positive for, SARS-CoV2. Severe infections requiring admission were observed in one patient in each group. Other SAE included two episodes of hypovolemia with relapse, and an inguinal herniotomy in patients receiving tacrolimus (Online Resource 4).

Nine patients showed 12 infusion-related reactions during or after administration of rituximab. While tachycardia was common, one patient had throat discomfort requiring IV pheniramine, a CTCAE grade 3 reaction. No event was categorized as CTCAE grade 4–5. Most common events associated with tacrolimus use were diarrhea and/or gastritis (55 episodes in 15 patients). Four of five episodes of acute kidney injury were in patients administered tacrolimus, associated with hypovolemia in relapse or high tacrolimus levels.

Monitoring of therapy

B cells were depleted after two doses of rituximab in 18 (90%) patients and after 3 doses in one patient; one did not deplete B cells despite four doses. The patient who required three doses to deplete B-lymphocytes relapsed at 6 months, while the one given four doses sustained remission till 12 months. B-lymphocytes had repopulated at relapse in the nine patients who relapsed [median count 304 (IQR 217–537) cells/µL; 11.6 (9.8–14.3)%], and by end of study in all patients [count 242 (22–657) cells/µL; 7.6 (0.6–21.0)%] (Online Resource 5). Tacrolimus was administered at median (IQR) dose of 0.08 (0.06–0.09) mg/kg/day; compliance to doses was 98% (94.1–99.8%). Median tacrolimus trough level was within the target range at baseline, at 6 months, and at end of study, but low (3.8 ng/mL) at relapse (Online Resource 6).

Per-protocol analysis

Per-protocol population included 15 patients in the tacrolimus group and 20 in the rituximab group (Fig. 1). Baseline characteristics of these patients were similar between groups (Online Resource 7). The proportions of patients in sustained remission at 1 year were 55% in the rituximab group and 67% in the tacrolimus group (risk ratio 0.83; 95% CI 0.48–1.41; Online Resource 8). There was a trend towards treatment failure being more common following therapy with rituximab (35 vs. 7%; risk ratio 5.25; 95% CI 0.72–38.23). The groups did not differ significantly in the incidence of relapses (incidence rate ratio 2.04; 95% CI 0.82, 5.68) and cumulative prednisolone dose (mean difference 0.04 mg/kg/day; 95% CI – 0.05, 0.13 mg/kg/day).

Exploratory post hoc analysis

There were no significant between-group differences in the proportions of patients with sustained remission or treatment failure, in subgroups based on age and disease severity on modified intention-to-treat (Online Resource 9) and per-protocol populations. Fragility index for treatment failure was one, i.e., changing the status of one patient from non-event to event in the tacrolimus group caused the difference in rates of treatment failure to lose statistical significance.

Discussion

This open-label, single-center pilot RCT examined the non-inferiority of two doses of IV rituximab to 1-year treatment with oral tacrolimus, in sustaining remission in patients with difficult-to-treat steroid-sensitive nephrotic syndrome. Baseline characteristics show selection of patients with prolonged steroid-dependent or frequently relapsing disease that had failed previous therapies, with significant steroid toxicity. Therapy with both agents enabled significant reduction in relapses and corticosteroid requirement compared to baseline, and improved anthropometric scores and blood pressure. While the proportions of patients with sustained remission were similar, non-inferiority of rituximab was not demonstrated. Although no patient relapsed during rituximab-induced B cell depletion, relapses beyond 6 months of therapy led to treatment failure in one-third of these patients. Relapses in the tacrolimus group were associated with low median trough levels, indicating the need for more frequent monitoring of drug levels and medication adherence using compliance questionnaires. The impact of the study is limited by its small size which led to inability to demonstrate the non-inferiority of rituximab in sustaining remission or claim superiority of tacrolimus in preventing frequent relapses.

While the management of frequently relapsing nephrotic syndrome is challenging, most patients attain satisfactory remission following prolonged therapy with prednisone and/or corticosteroid-sparing medications such as levamisole, cyclophosphamide, or MMF [17]. Therapy with CNI and rituximab is usually reserved for patients who continue to relapse frequently despite use of these agents, and/or show corticosteroid adverse effects. The reluctance to use these therapies early in the disease course stems from the risk of adverse effects, comprising chiefly nephrotoxicity with use of CNI [18], and infusion-related reactions, serious infections, and hypogammaglobulinemia with rituximab [3, 19].

The efficacy of CNI in steroid-dependent nephrotic syndrome was shown in multiple observational studies [20], and RCTs indicate that the risk of relapse at 1 year of therapy with ciclosporin was lower than on prednisolone (RR 0.72; 95% CI 0.46–1.13), similar to MMF (RR 0.53; 0.18–1.52), and higher than with alkylating agents (RR 1.96; 1.35–2.86) [3, 21]. Despite limited evidence of efficacy in steroid-sensitive disease [22–24], tacrolimus is preferred to ciclosporin given its lack of cosmetic adverse effects [25]. Following case series [19], five RCTs have compared the efficacy of rituximab to controls in high-threshold steroid- and/or CNI-dependence [26–28], or to prednisolone [29] or placebo [30] in frequent relapses or mild steroid dependence to confirm that B cell depletion, with or without steroids and CNI, is associated with reduced risk of relapse as compared to CNI or no therapy (3 RCT on 198 children; RR 0.63; 95% CI 0.42–0.93) [3].

The term “difficult-to-treat” nephrotic syndrome, while not defined clearly in the literature, is reserved for patients with steroid-sensitive nephrotic syndrome who continue to show frequent disease relapses despite use of multiple therapeutic agents, and patients with CNI-dependent or CNI-refractory steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome [1, 28]. Conforming to our previous definition, we included patients with frequent relapses or steroid dependence who did not show satisfactory response to at least two strategies [4, 31, 32]. This definition was also endorsed in the revised guidelines of the Indian Society of Pediatric Nephrology [1]. Thus, the study was limited to patients with difficult-to-treat nephrotic syndrome in whom therapy with rituximab or CNI had not been used, so as to objectively examine the safety and efficacy of these two medications. Both groups of patients had received two or more therapies for frequent relapses, chiefly levamisole and cyclophosphamide; the use of MMF was restricted to less than one-third of patients, likely due to out-of-pocket costs and uncertain efficacy in absence of access to therapeutic drug monitoring. All patients had significant corticosteroid toxicity, precluding use of milder therapies. Overall, inclusion was deliberately restricted to a uniformly difficult category of patients to avoid heterogeneity.

The results of this pilot RCT are similar to our findings in a retrospective uncontrolled comparison on 21 patients with steroid-dependent disease that was refractory to therapy with multiple agents. Favorable short-term outcomes were observed in similar proportions of patients administered 2–3 doses of IV rituximab or oral tacrolimus for 1 year [4]. A recent open-label RCT compared the efficacy of two doses of rituximab to 12 months therapy with oral tacrolimus in 120 patients with frequent relapses [5]. In contrast to the present study, patients lacked any exposure to corticosteroid-sparing agents and were enrolled early in disease course (median duration of disease 2.5 years). Rates of relapse-free survival were significantly higher in patients administered rituximab compared to tacrolimus (90 vs. 63%; OR 5.2; 95% CI 1.9–14.1). In contrast, in the present study, only 55% patients in either group sustained remission for 1 year, and therapy with rituximab was associated with treatment failure more often than tacrolimus. While patients receiving tacrolimus fared similarly in the two studies, the variable outcomes following therapy with rituximab may be explained by the difference in disease severity. The rates of rituximab-induced sustained remission at 1 year were 25–66% in studies enrolling steroid- and/or CNI-dependent patients [26–28, 30], and 87% in a study on patients with low-threshold steroid-dependence [29].

About 10–25% patients receiving therapy with CNI for 2–3 years develop irreversible histological nephrotoxicity [33, 34]. Similar to the present report, controlled studies on children with steroid-sensitive or resistant nephrotic syndrome have observed decline in eGFR by 9–20 mL/min/1.73 m2 and acute kidney injury after 1-year therapy with CNI [21, 25, 35]. Gastrointestinal adverse events associated with tacrolimus therapy were more frequent than reported previously in nephrotic syndrome [21, 25, 35] and other diseases [36, 37]. Infusion reactions were the most prominent adverse events following rituximab therapy in the present study, confirming findings of a meta-analysis that found fivefold risk compared to controls (4 studies in 252 children; RR 5.8, 95% CI 1.3–25.3) [3]. Therapy was not associated with risk of serious bacterial infections or COVID-19. Hypogammaglobulinemia, reported usually following sustained B-lymphocyte depletion with sequential dosing, particularly in young children [38, 39], was not looked for.

The chief limitations of the study include its open label design and small sample size. The SARS-CoV2 pandemic imposed additional challenges in monitoring and evaluation. B lymphocyte subsets, such as memory B cells, and IgG levels were not monitored during therapy with rituximab. While confounding was avoided by stratified randomization, findings on post hoc analysis are limited by the small study size. Despite these limitations, this pilot trial enrolled a homogeneous population with severe disease, with careful attention to aspects of efficacy as well as safety, and reports outcomes using both per-protocol and modified intention-to-treat analysis without any attrition. The comparative efficacy of the two agents requires closer re-evaluation in adequately powered multicenter studies on patients with difficult-to-treat steroid-dependent nephrotic syndrome. Since the efficacy of rituximab wanes following B cell repopulation, future studies might examine the non-inferiority or superiority of a protocol involving redosing with rituximab every 6–12 months to sustain B cell depletion. Assessment of the safety of therapy would require evaluations for nephrotoxicity and hypogammaglobulinemia during 18–24 months follow-up.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Support of the Department of Biotechnology, Government of India (BT/PR11030/MED/ 30/1644/2016) and Indian Council of Medical Research (5/7/1090/2013-RHN) is acknowledged.

Author contribution

GM made substantial contribution to the acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data and drafted the manuscript. NG and AA helped in clinical and laboratory work, respectively, and NG supervised drug administration. AS, PH, PK, and AB made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the work and revised the work critically for important intellectual content. AS agrees to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy and integrity of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Funding

Interventions administered in the study (rituximab and tacrolimus) were supplied by Intas Pharmaceuticals (Ahmedabad, India). The sponsors had no influence or access to the design, execution or analysis of the study. No financial incentives were provided, directly to any of the authors or the institution, over the 36 months prior to the submission or subsequently.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval

Institutional ethics committee approval was obtained in September 2018 (IECPG-390/30.08.2018, RT-4/27.09.2018) and the trial was prospectively registered with the Clinical Trials Registry of India (CTRI/2018/11/016342) in November 2018 before commencing the study.

Consent to participate

Written informed consent was obtained from either of parents or legal guardian before enrollment in the study. Consent for publication was obtained from parents or legal guardian before enrolment into the study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Sinha A, Bagga A, Banerjee S, Mishra K, Mehta A, Agarwal I, Uthup S, Saha A, Mishra OP, Expert group of Indian Society of Pediatric Nephrology Steroid sensitive nephrotic syndrome: revised guidelines. Indian Pediatr. 2021;58:461–481. doi: 10.1007/s13312-021-2217-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Glomerular Diseases Work Group KDIGO 2021 Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Glomerular Diseases. Kidney Int. 2021;100:S1–S276. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2021.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Larkins NG, Liu ID, Willis NS, Craig JC, Hodson EM. Non-corticosteroid immunosuppressive medications for steroid-sensitive nephrotic syndrome in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;4:CD002290. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002290.pub5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sinha A, Bagga A, Gulati A, Hari P. Short-term efficacy of rituximab versus tacrolimus in steroid-dependent nephrotic syndrome. Pediatr Nephrol. 2012;27:235–241. doi: 10.1007/s00467-011-1997-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Basu B, Sander A, Roy B, Preussler S, Barua S, Mahapatra TKS, Schaefer F. Efficacy of rituximab vs tacrolimus in pediatric corticosteroid-dependent nephrotic syndrome: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatr. 2018;172:757–764. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.1323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Piaggio G, Elbourne DR, Pocock SJ, Evans SJW, Altman DG, CONSORT group Reporting of noninferiority and equivalence randomized trials: Extension of the CONSORT 2010 Statement. JAMA. 2012;308:2594–2604. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.87802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eldridge SM, Chan CL, Campbell MJ, Bond CM, Hopewell S, Thabane L, Lancaster GA. CONSORT 2010 statement: extension to randomized pilot and feasibility trials. BMJ. 2016;355:i5239. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i5239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khadilkar VV, Khadilkar AV. Revised Indian Academy of Pediatrics 2015 growth charts for height, weight and body mass index for 5–18-year-old Indian children. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2015;19:470–476. doi: 10.4103/2230-8210.159028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khadilkar V, Khadilkar A, Arya A, Ekbote V, Kajale N, Parthasarathy L, Patwardhan V, Phanse S, Chiplonkar S. Height velocity percentiles in Indian children aged 5–17 years. Indian Pediatr. 2019;56:23–28. doi: 10.1007/s13312-019-1461-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schwartz GJ, Muñoz A, Schneider MF, Mak RH, Kaskel F, Warady BA, Furth SL. New equations to estimate GFR in children with CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:629–637. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008030287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mayer-Davis EJ, Kahkoska AR, Jefferies C, Dabelea D, Balde N, Gong CX, Aschner P, Craig ME. ISPAD clinical practice consensus guidelines 2018: Definition, epidemiology, and classification of diabetes in children and adolescents. Pediatr Diabetes. 2018;19(Suppl 27):7–19. doi: 10.1111/pedi.12773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sellier-Leclerc AL, Baudouin V, Kwon T, Macher MA, Guérin V, Lapillonne H, Deschênes G, Ulinski T. Rituximab in steroid-dependent idiopathic nephrotic syndrome in childhood—follow-up after CD19 recovery. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2012;27:1083–1089. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfr405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Flynn JT, Kaelber DC, Baker-Smith CM, Blowey D, Carroll AE, Daniels SR, de Ferranti SD, Dionne JM, Falkner B, Flinn SK, Gidding SS, Goodwin C, Leu MG, Powers ME, Rea C, Samuels J, Simasek M, Thaker VV, Urbina EM. Clinical practice guideline for screening and management of high blood pressure in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2017;140:e20171904. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-1904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE). NCI Enterprise Vocabulary Services (EVS) (2019) https://evs.nci.nih.gov/ftp1/CTCAE/CTCAE_5.0/. Published 17 December 2019. Accessed 31 March 2021

- 15.World Health Organization (2013) The use of the WHO-UMC system for standardized case causality assessment. https://www.who.int/medicines/areas/quality_safety/safety_efficacy/WHOcausality_assessment.pdf. Published 5 June 2013. Accessed 31 March 2021

- 16.Walter SD. Statistical significance and fragility criteria for assessing a difference of two proportions. J Clin Epidemiol. 1991;44:1373–1378. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(91)90098-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sinha A, Hari P, Sharma PK, Gulati A, Kalaivani M, Mantan M, Dinda AK, Srivastava RN, Bagga A. Disease course in steroid sensitive nephrotic syndrome. Indian Pediatr. 2012;49:881–887. doi: 10.1007/s12098-012-0776-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu F, Mao J-H. Calcineurin inhibitors and nephrotoxicity in children. World J Pediatr. 2018;14:121–126. doi: 10.1007/s12519-018-0125-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sinha A, Bagga A. Rituximab therapy in nephrotic syndrome: Implications for patients’ management. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2013;9:154–169. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2012.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arslansoyu Camlar S, Soylu A, Kavukçu S (2018) Cyclosporine in pediatric nephrology. Iran J Kidney Dis 12:319–330 [PubMed]

- 21.Gellermann J, Weber L, Pape L, Tönshoff B, Hoyer P, Querfeld U. Mycophenolate mofetil versus cyclosporin A in children with frequently relapsing nephrotic syndrome. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;24:1689–1697. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2012121200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sinha MD, MacLeod R, Rigby E, Clark AGB. Treatment of severe steroid-dependent nephrotic syndrome (SDNS) in children with tacrolimus. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2006;21:1848–1854. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfi274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang W, Xia Y, Mao J, Chen Y, Wang D, Shen H, Fu H, Du L, Liu A. Treatment of tacrolimus or cyclosporine A in children with idiopathic nephrotic syndrome. Pediatr Nephrol. 2012;27:2073–2079. doi: 10.1007/s00467-012-2228-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Delbet JD, Aoun B, Buob D, Degheili J, Brocheriou I, Ulinski T. Infrequent tacrolimus-induced nephrotoxicity in French patients with steroid-dependent nephrotic syndrome. Pediatr Nephrol. 2019;34:2605–2608. doi: 10.1007/s00467-019-04343-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Choudhry S, Bagga A, Hari P, Sharma S, Kalaivani M, Dinda A. Efficacy and safety of tacrolimus versus cyclosporine in children with steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;53:760–769. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2008.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ravani P, Magnasco A, Edefonti A, Murer L, Rossi R, Ghio L, Benetti E, Scozzola F, Pasini A, Dallera N, Sica F, Belingheri M, Scolari F, Ghiggeri GM. Short-term effects of rituximab in children with steroid- and calcineurin-dependent nephrotic syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6:1308–1315. doi: 10.2215/CJN.09421010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ravani P, Rossi R, Bonanni A, Quinn RR, Sica F, Bodria M, Pasini A, Montini G, Edefonti A, Belingheri M, Giovanni DD, Barbano G, DegĺInnocenti L, Scolari F, Murer L, Reiser J, Fornoni A, Ghiggeri GM. Rituximab in children with steroid-dependent nephrotic syndrome: a multicenter open-label, noninferiority randomized controlled trial. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;26:2259–2266. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2014080799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ahn YH, Kim SH, Han KH, Choi HJ, Cho H, Lee JW, Shin JI, Cho MH, Lee JH, Park YS, Ha I-S, Cheong HI, Kim SY, Lee SJ, Kang HG. Efficacy and safety of rituximab in childhood-onset, difficult-to-treat nephrotic syndrome. Medicine (Baltimore) 2018;97:e13157. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000013157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ravani P, Lugani F, Pisani I, Bodria M, Piaggio G, Bartolomeo D, Prunotto M, Ghiggeri GM. Rituximab for very low dose steroid-dependent nephrotic syndrome in children: a randomized controlled study. Pediatr Nephrol. 2020;35:1437–1444. doi: 10.1007/s00467-020-04540-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Iijima K, Sako M, Nozu K, Mori R, Tuchida N, Kamei K, Miura K, Aya K, Nakanishi K, Ohtomo Y, Takahashi S, Tanaka R, Kaito H, Nakamura H, Ishikura K, Ito S, Ohashi Y. Rituximab for childhood-onset, complicated, frequently relapsing nephrotic syndrome or steroid-dependent nephrotic syndrome: a multicentre, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2014;384:1273–1281. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60541-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sinha A, Bhatia D, Gulati A, Rawat M, Dinda AK, Hari P, Bagga A. Efficacy and safety of rituximab in children with difficult-to-treat nephrotic syndrome. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2015;30:96–106. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfu267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gulati A, Sinha A, Jordan SC, Hari P, Dinda AK, Sharma S, Srivastava RN, Moudgil A, Bagga A. Efficacy and safety of treatment with rituximab for difficult steroid-resistant and -dependent nephrotic syndrome: multicentric report. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5:2207–2212. doi: 10.2215/CJN.03470410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sinha A, Sharma A, Mehta A, Gupta R, Gulati A, Hari P, Dinda AK, Bagga A. Calcineurin inhibitor induced nephrotoxicity in steroid resistant nephrotic syndrome. Indian J Nephrol. 2013;23:41–46. doi: 10.4103/0971-4065.107197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim JH, Park SJ, Yoon SJ, Lim BJ, Jeong HJ, Lee JS, Kim PK, Shin JI. Predictive factors for ciclosporin-associated nephrotoxicity in children with minimal change nephrotic syndrome. J Clin Pathol. 2011;64:516–519. doi: 10.1136/jclinpath-2011-200005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gulati A, Sinha A, Gupta A, Kanitkar M, Sreenivas V, Sharma J, Mantan M, Agarwal I, Dinda AK, Hari P, Bagga A. Treatment with tacrolimus and prednisolone is preferable to intravenous cyclophosphamide as the initial therapy for children with steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome. Kidney Int. 2012;82:1130–1135. doi: 10.1038/ki.2012.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hannah J, Casian A, D’Cruz D. Tacrolimus use in lupus nephritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Autoimmun Rev. 2016;15:93–101. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2015.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yocum DE, Furst DE, Bensen WG, Burch FX, Borton MA, Mengle-Gaw LJ, Schwartz BD, Wisememandle W, Mekki QA, on behalf of the Tacrolimus RA Study Group (2004) Safety of tacrolimus in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: long-term experience. Rheumatology (Oxford) 43:992–999. 10.1093/rheumatology/keh155 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.Parmentier C, Delbet J-D, Decramer S, Boyer O, Hogan J, Ulinski T. Immunoglobulin serum levels in rituximab-treated patients with steroid-dependent nephrotic syndrome. Pediatr Nephrol. 2020;35:455–462. doi: 10.1007/s00467-019-04398-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Christou EAA, Giardino G, Worth A, Ladomenou F. Risk factors predisposing to the development of hypogammaglobulinemia and infections post-Rituximab. Int Rev Immunol. 2017;36:352–359. doi: 10.1080/08830185.2017.1346092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.