Lay Summary

Our cluster randomized trial compared two interventions that health departments commonly use to increase HPV vaccination coverage: quality improvement (QI) coaching and physician communication training. We found that QI coaching cost less and was more often adopted by primary care clinics, but communication training reached more staff members per clinic, including vaccine prescribers. Findings provide health departments with data needed to weigh the implementation strengths and challenges of QI coaching and physician communication training for increasing HPV vaccination coverage.

Keywords: Human papillomavirus vaccine, Cancer prevention, Implementation science, Quality improvement, IQIP, Physician communication

Abstract

Many US health departments (HDs) conduct in-person quality improvement (QI) coaching to help primary care clinics improve their HPV vaccine delivery systems and communication. Some HDs additionally conduct remote communication training to help vaccine prescribers recommend HPV vaccination more effectively. Our aim was to compare QI coaching and communication training on key implementation outcomes. In a cluster randomized trial, we offered 855 primary care clinics: 1) QI coaching; 2) communication training; or 3) both interventions combined. In each trial arm, we assessed adoption (proportion of clinics receiving the intervention), contacts per clinic (mean number of contacts needed for one clinic to adopt intervention), reach (median number of participants per clinic), and delivery cost (mean cost per clinic) from the HD perspective. More clinics adopted QI coaching than communication training or the combined intervention (63% vs 16% and 12%, both p < .05). QI coaching required fewer contacts per clinic than communication training or the combined intervention (mean = 4.7 vs 29.0 and 40.4, both p < .05). Communication training and the combined intervention reached more total staff per clinic than QI coaching (median= 5 and 5 vs 2, both p < .05), including more prescribers (2 and 2 vs 0, both p < .05). QI coaching cost $439 per adopting clinic on average, including follow up ($129/clinic), preparation ($73/clinic), and travel ($69/clinic). Communication training cost $1,287 per adopting clinic, with most cost incurred from recruitment ($653/clinic). QI coaching was lower cost and had higher adoption, but communication training achieved higher reach, including to influential vaccine prescribers.

Implications.

Practice: Health departments must compare implementation strengths and challenges, such as cost, adoption, and reach, when determining which evidence-based quality improvement intervention is appropriate for improving HPV vaccination coverage in primary care clinics they serve.

Policy: Balancing intervention benefits against costs underscores a need to ensure adequate funding to health departments so that they may provide necessary tools and training to primary care clinics in their jurisdictions.

Research: Future research should examine the cost effectiveness of physician communication training and quality improvement coaching interventions.

Background

State and regional health departments play an important, but understudied role in efforts to improve vaccination services in the US. Such efforts are especially important for human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination. Despite national recommendations for routine administration to adolescents at ages 11–12 years[1], only 54% of adolescents aged 13–17 were up to date on the multi-dose vaccine series by 2019 [2]. Key barriers to HPV vaccination include infrequent and ineffective prescriber recommendations, as well as health system factors such as underuse of patient reminder/recall and standing orders, limited provider time, and competing priorities [3–10]. Health departments are important partners for scaling up interventions to address these barriers because they offer an existing, national workforce and a population health perspective that emphasizes broad implementation with primary care clinics across their jurisdictions [11]. Given the breadth of their work, along with budget cuts in recent years [12, 13], health departments are best served by focusing on interventions that are highly scalable and that will be adopted by clinics, reach large numbers of vaccine prescribers, and incur relatively low costs.

One intervention that meets these criteria is the national AFIX (Assessment, Feedback, Incentives, and eXchange) program, which was recently updated to be the Immunization Quality Improvement for Providers program (IQIP, https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/programs/iqip/at-a-glance.html) [14]. AFIX involves in-person quality improvement (QI) coaching consultations in which health department staff visit clinics that receive federally funded vaccines to provide vaccine-related education, assessment and feedback on clinics’ own vaccination rates, and guidance on strategies to improve vaccine delivery. Prior research suggests that AFIX increases HPV vaccination coverage in the short-term, but requires enhancements to sustain those improvements [15–17]. Thus, in partnership with Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), our research team developed an HPV vaccine-specific version of AFIX that seeks to leverage the evidence-based implementation strategies[18] of assessment and feedback and QI coaching to achieve more lasting improvements in HPV vaccination coverage [19–21]. Importantly, most states are required as a condition of funding to deliver AFIX annually to at least 25% of primary care clinics who receive federally funded vaccines through the Vaccines for Children program, and some states deliver AFIX even more broadly. Since all states implement AFIX on a broad scale, the program represents an important existing network of implementation support for improving HPV vaccination in primary care.

In addition to AFIX, some health departments also contract with outside experts to provide physician communication training, which typically occurs remotely. Delivered by physicians, this educational outreach focuses on helping the clinic’s physicians and other vaccine prescribers improve their HPV vaccine recommendations [22–24]. Such training is appealing because physician experts may have more influence over vaccine prescribers than health department staff; however, because physician experts are highly trained, they are also more expensive. The value for health departments to bring physician communication training to scale nationally depends on the intervention’s ability to reach physicians and other prescribers efficiently, but the reach and cost of this approach have not, to our knowledge, been studied. Furthermore, the ideal relationship between AFIX QI coaching and physician communication training is also unknown; it is unclear whether physician communication training is best delivered on its own or if it should be packaged with an in-person AFIX session, to improve vaccination at both the prescriber and clinic level simultaneously.

To address this gap, we conducted a randomized implementation trial comparing AFIX QI coaching and physician communication training, alone and in combination, on implementation outcomes. We delivered physician communication training using an adapted version of the Announcement Approach Training (AAT) intervention. AAT is a brief (<1 hr) communication workshop that trains physicians and other vaccine prescribers to use presumptive recommendations that introduce HPV vaccination as the default choice in routine care. Our prior research has established that AAT increases HPV vaccination coverage among adolescent patients in primary care, and based on this evidence, the National Cancer Institute recognizes the intervention as an Evidence-Based Cancer Control Program [22, 23]. We compared AFIX and AAT interventions on implementation outcomes, including adoption, reach, contacts per clinic, and delivery cost [25, 26]. By providing novel implementation data on two evidence-based interventions, this study seeks to help health departments understand the strengths and challenges of AFIX and physician communication training so that they can make the most of limited funds in their efforts to improve HPV vaccination coverage. Additionally, this trial is designed to inform implementation science more broadly by comparing QI coaching, which seeks to change clinical systems, with communication training, which seeks to improve physicians’ interpersonal interactions with parents.

Methods

Participants

In December 2017, we partnered with HDs in three US states to conduct our trial. We selected HDs with robust vaccine registries (or “immunization information systems”), sufficient numbers of eligible clinics to meet recruitment requirements, and staff (“AFIX coaches”) interested in focusing on HPV vaccination. States were in the Southwest (SW), the Northeast (NE), and the Midwest (MW).

With each partnering state, eligible clinics: (1) had a pediatric or family medicine focus; (2) participated in Vaccines for Children (VFC) [27], a federally funded program that provides vaccines at no cost to certain populations ages 18 years and younger, including Medicaid-eligible and uninsured children; and (3) had between 200 and 7,000 adolescent patients (ages 11–17) according to their state’s immunization information system. We excluded pharmacies and school health clinics because these settings may differ substantially from primary care clinics in their HPV vaccine delivery systems. We excluded clinics that: (1) were part of very large healthcare systems (i.e., those with 30 or more clinics) to maximize the comparability of our study arms; or (2) had baseline coverage for HPV vaccine initiation (≥1 dose) of greater than or equal to 85% to focus interventions on clinics with higher need for improvement.

Procedures

In April 2018, we randomly assigned 855 eligible clinics to one of four trial arms: QI coaching via the HPV vaccine-specific AFIX intervention, physician communication training via AAT, both interventions (AFIX+AAT), or control. We used a parallel-group trial design and randomized clinics in a 1:1:1:1 ratio. We randomized clinics that were part of the same healthcare system or network in blocks to prevent contamination among trial arms. We offered clinics interventions from April through September 2018 with a recruitment target of 90 clinics for each trial arm. The purpose of this paper is to compare the AFIX and AAT interventions on implementation outcomes; thus, this paper focuses solely on clinics in the three intervention arms and excludes clinics in the control arm. Vaccination outcomes are forthcoming and will be reported separately.

Recruitment and scheduling procedures differed by trial arm. For the AFIX arm, AFIX coaches recruited clinics for sessions by phone and email, using established contacts when available. For the AAT arm, the study team’s physician educators and study staff recruited clinics by phone and email, using contact information provided by state immunization programs or found online. For AFIX+AAT, recruitment occurred sequentially, with AFIX coaches first scheduling AFIX sessions and physician educators and study staff next scheduling AAT sessions. AFIX coaches, physician educators, or study staff made at least six attempts to contact clinics to schedule sessions.

AFIX QI Coaching

We offered clinics in the AFIX arm a single in-person, HPV vaccine-specific QI coaching session led by an AFIX coach from their state’s HD [14]. AFIX coaches scheduled the session with one or more members of the clinic’s healthcare team; the intended audience for each session was any member of the healthcare team, with a goal of including vaccine prescribers when possible. We designed the session to include four implementation strategies: educational outreach, assessment and feedback, action planning, and follow up [18]. First, AFIX coaches used PowerPoint slides and talking points to deliver a brief didactic presentation on HPV infection and HPV vaccination, including strategies to improve coverage. Second, AFIX coaches shared assessment and feedback results of the clinic’s adolescent vaccination coverage via an immunization report card; the report card presented coverage for HPV vaccine initiation, using coverage for two other vaccines routinely administered to adolescents (Tdap and serogroups A, C, W, and Y meningococcal vaccine) as the comparison. Third, AFIX coaches worked with clinics to create an action plan, which involved setting a measurable QI goal and selecting strategies (e.g., recommending same-day HPV vaccination for all patients by age 11, or establishing standing orders for adolescent HPV vaccination) to meet the QI goal. Each AFIX session was approximately 1 hr long. Lastly, clinics received follow-up report cards with updated coverage on their QI goals at three and six months after the initial session. We offered 1 hr of CME credit to physician participants as an incentive. More information about the AFIX QI coaching intervention is described in our previous work [28].

AAT Physician Communication Training

For clinics in the AAT arm, physician educators from the study team delivered a single one-hour session via a virtual conferencing platform (Zoom). Healthcare teams, with an emphasis on vaccine prescribers who recommend adolescent vaccines, were the intended audience of the session. The AAT intervention is designed to use the implementation strategy of educational outreach [18]. The study’s trained physician educators delivered an adapted version of AAT with the goal of improving HPV vaccine communication with parents. The training teaches healthcare teams to use “presumptive announcements,” to introduce adolescent vaccines. Presumptive announcements present vaccination as the default choice. For example, a vaccine prescriber might say, “Now that Michael is 11, he is due for three vaccines to protect against meningitis, HPV cancers, and pertussis, and we’ll give those at the end of the visit today.” The training begins with a didactic session with information about HPV-associated cancers and HPV vaccination, followed by an interactive session in which participants have the opportunity to practice responding to common parental concerns. At the end of the session, the physician educator answers participants’ questions and guides discussions about how the team can integrate this model in their own practice. Physician participants were offered one hour of CME credit as an incentive. Current AAT materials are available at hpvIQ.org.

AFIX+AAT

The AFIX+AAT arm included both interventions. We assigned clinics to receive an in-person AFIX session delivered by health department staff, followed by a remote AAT session delivered by a physician educator.

Measures

Adoption, Contacts per Clinic, and Reach

Adoption is “the intention, initial decision, or action to try or employ an innovation or evidence-based practice” [25]. We operationalized adoption as the proportion of clinics that received the session(s) to which they were allocated (i.e., AFIX session, AAT session, or both). Clinics that scheduled but did not receive the allocated intervention for their trial arm were not categorized as adopters. For example, some clinics in the AFIX+AAT arm received an AFIX session, but later declined an AAT session; we did not count these as adopters. To understand the effort required to achieve adoption, we also assessed contacts per clinic, or the number of contact attempts required for a clinic to adopt the intervention during the study period.

Reach is defined as “an individual-level measure of participation” [25, 26]. We operationalized reach as the number and type (total clinic staff or vaccine prescriber) of participants within clinics who attended the intervention session. Using participation logs, we noted the number of total staff participants for the session, including how many of the participants were vaccine prescribers, based on self-report.

Delivery Cost

Cost is defined as “the cost impact of an implementation effort” [25]. We operationalized cost as delivery cost and assessed it from the perspective of interventionists (i.e., health departments). We determined staff time spent on intervention delivery (excluding data collection activities conducted for research purposes), using individual staff salaries to determine an hourly rate. We also included the cost of any materials used for each intervention arm. We calculated costs for AFIX and AAT sessions separately, rather than by trial arm, dividing the cost of the AFIX+AAT arm into its component parts. AFIX coaches, AAT physician educators, and study staff involved in recruitment and intervention delivery completed weekly online time logs, recording time spent on recruitment, preparation, intervention delivery, follow up, travel (AFIX only), and training and technical assistance, rounded to the nearest half hour. We did not include costs incurred by participating clinics or their physicians and staff.

For the AFIX sessions, costs were related to: (1) recruitment to enroll clinics and schedule sessions; (2) session preparation, including completion of clinic immunization report cards; (3) intervention delivery, or time spent conducting AFIX sessions; (4) follow up, including sending clinics their report cards with progress reports, and calls and emails with clinics after the session; (5) travel time to clinics; and (6) training and technical assistance to aid AFIX coaches in other training or technical needs. We also included the cost of mailings into the total cost for the AFIX arm as other expenses.

For the AAT sessions, we assessed costs related to physician educator and study staff tasks, which included: (1) recruitment to enroll clinics and schedule sessions; (2) session preparation, including updating training scripts with state- and clinic-specific vaccine coverage rates, sending webinar links to meeting participants, and sending training materials to clinics); (3) intervention delivery, or time spent conducting sessions, including setting up and troubleshooting of technology; (4) follow-up to answer questions or provide additional resources to healthcare teams after sessions; and (5) training and technical assistance to aid physician educators in any virtual training or technical needs. We also included the cost of postage, faxing via an online service, a Zoom subscription, paper, envelopes, and post cards into the total cost for the AAT arm as other costs.

Data Analysis

To assess adoption within each intervention arm, we divided the number of clinics that received an intervention by the total number of clinics contacted in each arm. To calculate the effort used to recruit the clinics that received an intervention, we determined the average number of contacts per clinic, or the total number of contacts for all contacted clinics divided by the number of clinics that received an intervention. In other words, interventionists could expect to make a certain average number of contacts (calls or emails) to achieve adoption by one clinic. We calculated reach as the median number of total staff at each session, and the median number of prescribers at each session; medians were used for reach calculations because data were non-normal and a median is a better measure of central tendency.

To compare adoption rates and effort to recruit clinics to adopt (number of total contacts per recruited clinic) across trial arms and states, we used logistic regression models followed by Wald tests. To determine if reach to prescribers and staff varied across trial arms and states, we compared rank means using Kruskal–Wallis and Dunn tests due to the non-normality of data.

We evaluated the total cost for AFIX and AAT sessions, and determined the average cost for each component (recruitment, session preparation, intervention delivery, follow up, travel [AFIX only], and training and technical assistance). We also determined the cost per clinic, per hour, per total staff participant, and per prescriber participant for AFIX and AAT sessions. For example, to determine cost per clinic, we divided the total intervention cost by the number of completed AAT sessions (in both the AAT and AFIX+AAT arms) or the number of completed AFIX sessions (in both the AFIX and AFIX+AAT arms). Deidentified datasets used to support conclusions are publicly available [29].

Results

Adoption, Contacts per Clinic, and Reach

Adoption

In our overall sample, 63% (89/141) of clinics allocated to the AFIX arm adopted AFIX, 16% (31/199) of clinics in the AAT arm adopted AAT, and 12% (17/144) of clinics in the AFIX+AAT arm adopted AFIX+AAT (Table 1). Adoption was higher for AFIX than either AAT or AFIX+AAT (both p < 0.01), but did not differ between AAT and AFIX+AAT (p > 0.05). In analysis within trial arm, AFIX adoption was lower in the MW state (19/65) than in the SW (30/32) or the NE (40/44) states (29% vs. 94% and 91%, both p < 0.01). Adoption did not vary by state for AAT or AFIX+AAT (both p > .05).

Table 1.

Adoption and contacts per intervention clinic by trial arm

| AFIX | AAT | AFIX+AAT | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adoption overalla | 63% (89/141) | 16% (31/199) | 12% (17/144) |

| SW state | 94% (30/32) | 14% (10/72) | 6% (2/31) |

| NE state | 91% (40/44) | 20% (11/56) | 22% (8/36) |

| MW state | 29% (19/65) | 14% (10/71) | 9% (7/77) |

| Contacts per clinic overallb | 4.7 (420/89) | 29.0 (899/31) | 40.4 (686/17) |

| SW state | 1.4 (42/30) | 30.1 (301/10) | 74.5 (149/2) |

| NE state | 3.5 (138/40) | 27.3 (300/11) | 26.3 (210/8) |

| MW state | 12.6 (240/19) | 29.8 (298/10) | 46.7 (327/7) |

a Proportion of clinics that received intervention (Number that received intervention/Number contacted).

b Mean contacts needed to recruit one clinic (Number of contacts for all contacted clinics/Number of clinics that received the intervention).

Contacts per clinic

On average, it took 4.7 contacts to recruit a clinic in the AFIX arm, 29.0 contacts to recruit a clinic in the AAT arm, and 40.4 contacts to recruit a clinic in the AFIX+AAT arm (Table 1). AFIX required fewer contacts per clinic than AAT or AFIX+AAT (both p < 0.01). Contacts per recruited clinic for AAT and AFIX+AAT did not differ (p > 0.05).

Within each trial arm, contacts per clinic varied by state only for the AFIX intervention. In the AFIX arm, recruitment required fewer contacts per clinic in the SW state (1.4 contacts per clinic) and NE state (3.5 contacts per clinic) than in the MW state (12.6 contacts per clinic) (both p < 0.01). Within the AAT and AFIX+AAT arms, we detected no difference among states in contacts needed to recruit (all p > 0.05).

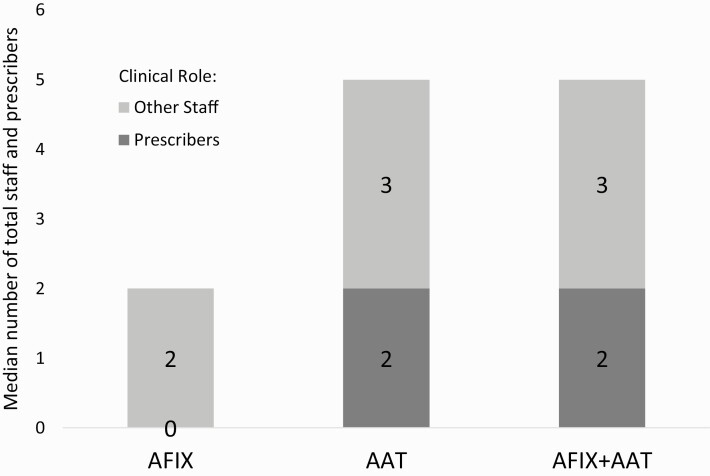

Reach per session

Median reach per sessions was 2.0 total staff members for AFIX (range: 1–24), 5.0 for AAT (range: 1–15), and 5.0 for AFIX+AAT (range: 2–11) (Table 2). Total staff reach per session was higher for AAT and AFIX+AAT compared to AFIX (both p < 0.01), but did not differ between AAT and AFIX+AAT. For prescribers, median reach per session was 0 for AFIX (range: 1–10), 2.0 for AAT (range: 0–10), and 2.0 for AFIX+AAT (range: 0–6) (Figure 1). Prescriber reach per session was higher for AAT and AFIX+AAT compared to AFIX (both p < 0.01), but did not differ between AAT and AFIX+AAT (p > 0.05).

Table 2.

Reach: Median number of total staff and prescribers by trial arm

| AFIX Median [min-max] |

AAT Median [min-max] |

AFIX+AAT Median [min-max] |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Staff | Prescribers | Total Staff | Prescribers | Total Staff | Prescribers | |

| Reach overall | 2.0 | 0.0 | 5.0 | 2.0 | 5.0 | 2.0 |

| [1–24] | [0–10] | [1–15] | [0–10] | [2–11] | [0–6] | |

| SW state | 1.0 | 0.0 | 5.0 | 3.0 | 2.5 | 1.0 |

| [1–2] | [0-0] | [1–13] | [0–6] | [2–3] | [1-1] | |

| NE state | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 5.5 | 3.0 |

| [1–12] | [0–10] | [1–7] | [0–5] | [3–11] | [2–6] | |

| MW state | 4.0 | 1.0 | 6.0 | 1.0 | 4.0 | 2.0 |

| [1–24] | [0–4] | [1–15] | [1–10] | [3–10] | [0–4] |

Fig 1.

Intervention reach: Median number of total staff and prescribers by trial arm

Within each trial arm, reach varied by state for AFIX and AFIX+AAT, but not AAT. In the AFIX arm, median reach to total staff per session varied from 1.0 in the SW state to 2.0 in the NE state to 4.0 in the MW state. Total staff reach varied significantly between all three states (all p < 0.05). Prescriber reach was lower in the SW state than in the NE and MW states (both p < 0.01). In the AFIX+AAT arm, median reach to total staff per session was 2.5 in the SW state, 5.5. in the NE state, and 4.0 in the MW state. Reach to total staff was lower in the SW state than in the NE and MW states (both p < 0.05). Prescriber reach was lower in the SW and MW states than in the NE state (both, p < 0.05).

Delivery Cost

AFIX

AFIX cost $439 per clinic, which included 10.4 hr of delivery time per clinic (Tables 3 and 4). About one-third of hours were spent on follow-up (31%), while fewer than one-fifth each were spent on recruitment (15%), preparation (17%), intervention delivery (13%), and travel (16%) (Table 4). The cost of reaching one clinic staff member was $150, and the cost of reaching one prescriber was $500 (Table 3).

Table 3.

Costs for AFIX and AAT interventionsa

| AFIXb | AATc | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | $76,366.68 | $61,756.35 | ||

| Per hour | $42 | ($76,367/1809 hr) | $64 | ($61,756/972 hr) |

| Per clinicd | $439 | ($76,367/174 clinics) | $1,287 | (61,756/48 clinics) |

| Per total staff | $151 | ($76,367/505 total staff) | $298 | ($61,756/207 total staff) |

| Per prescriber | $498 | ($76,367/154 prescribers) | $561 | ($61,756/110 prescribers) |

a Costs for AFIX+AAT arm divided into component parts.

b Includes 174 AFIX visits occurring in AFIX only and AFIX+AAT trial arms.

c Includes 48 AAT visits occurring in AAT only and AFIX+AAT trial arms.

d Cost per clinic that adopted intervention.

Table 4.

Average time and cost for AFIX and AAT interventions

| Time spent per recruited clinic | Delivery cost per recruited clinic | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AFIX hra | (%) | AAT hrb | (%) | AFIX $ | (%) | AAT $ | (%) | |

| Recruitment | 1.6 | (15) | 10.3 | (51) | $65 | (15) | $653 | (51) |

| Session preparation | 1.8 | (17) | 3.0 | (15) | $73 | (17) | $192 | (15) |

| Intervention delivery | 1.4 | (13) | 3.0 | (15) | $56 | (13) | $192 | (15) |

| Follow up | 3.2 | (31) | 0.5 | (3) | $129 | (30) | $38 | (3) |

| Travel | 1.7 | (16) | n/a | $69 | (16) | n/a | ||

| Training and technical assistance | 0.8 | (8) | 3.3 | (16) | $34 | (8) | $205 | (16) |

| Otherc | n/a | n/a | $8 | (2) | $6 | (0) | ||

| Total | 10.4 | 20.2 | $439 | $1,287 |

Note: n/a not applicable; numbers and percentages may not add due to rounding.

a Includes 174 AFIX visits occurring in AFIX only and AFIX+AAT trial arms.

b Includes 48 AAT visits occurring in AAT only and AFIX+AAT trial arms.

c Includes mailings, paper supplies, Zoom subscriptions.

AAT

AAT cost $1,287 per clinic, which included 20.2 hr of delivery time per clinic (Table 3 and 4). Recruitment made up just over 50% of total time spent (10.3 hr). Fewer than one-sixth of hours each were spent on session preparation (15%), intervention delivery (15%), follow up (3%), and training and technical assistance (16%). Physician educators and study staff spent no time on travel for the webinar sessions, and other materials cost about $6 per clinic (Table 4). The AAT cost of reaching one clinic staff member was $298, and the cost of reaching one prescriber was $561 (Table 3).

Discussion

Findings of our randomized implementation trial suggest that in-person AFIX QI coaching and remote AAT physician communication training interventions offer different advantages and disadvantages with respect to implementation outcomes for supporting HPV vaccination in primary care settings. Our QI coaching intervention was relatively widely adopted and cost less to deliver than communication training; however, QI coaching reached fewer total staff per clinic and almost no prescribers. By comparison, physician communication training had lower adoption and was expensive due to high recruitment cost. Nevertheless, this intervention had the advantage of reaching more total staff per clinic, including highly influential vaccine prescribers. The combined intervention arm of AFIX+AAT involved similar strengths and challenges as the physician communication training arm, albeit at higher cost.

Our QI coaching intervention performed well on measures of adoption, contacts per clinic, and cost. Nearly two-thirds of the contacted clinics adopted the intervention, and QI coaching adoption required fewer than five contacts per clinic on average. In turn, the time and cost needed to deliver QI coaching were relatively modest, which is consistent with prior studies [30, 31]. This analysis did not directly assess reasons for high adoption, but our prior qualitative work suggests that AFIX coaches’ local networks are important for facilitating adoption, given that some AFIX coaches have built connections to primary care teams over many years through provision of “regular” AFIX immunization programs not specifically tailored to HPV vaccination [28]. Clinics may have been familiar with the broader AFIX program, even if they had not had an HPV-specific AFIX visit. At the same time, the relative ease of adoption likely also reflects that QI coaching can be scheduled with a nurse, medical assistant, or office manager, who may be more readily available than the prescribers who are the targets of physician communication training. Indeed, QI coaching performed poorly on reach to prescribers. This low reach is problematic in the context of HPV vaccination, as vaccine prescribers are key to increasing vaccine coverage [3, 32–36], and suggests a tension between adoption and reach. If an AFIX coach has a relationship with a nurse or medical assistant in the clinic, “getting in the door” is relatively easy, but is unlikely to engage the overarching power structure of the clinic or larger healthcare system or reach prescribers [28].

In contrast to QI coaching, AAT physician communication training achieved relatively high reach to prescribers, who were the intervention’s target audience. However, this higher reach came at a cost, requiring many more contacts per clinic for scheduling trainings and a low proportion of clinics adopting physician communication training compared to QI coaching. Largely due to the recruiting burden, the average time and cost per clinic needed to implement physician communication training were high. The difficulty of recruiting clinics for physician communication training likely reflects the challenge of scheduling time with the busy prescribers who are the target of this intervention, and was compounded by physician experts’ lack of professional networks in local communities. Nevertheless, once physician experts identified interested clinics, they were successful at bringing prescribers to the table, perhaps because of their status and the appeal of a peer-to-peer approach. We also note that this study was conducted prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, when healthcare teams were likely less familiar with virtual trainings. The increasing use of virtual meetings and the rise of telehealth may make future implementation of remote communication training less challenging.

The combined AFIX+AAT intervention had similar implementation challenges and successes as physician communication training alone, but at higher cost. The combined intervention achieved high reach to prescribers, but required numerous contacts per clinic, with few clinics ultimately deciding to adopt both QI coaching and physician communication training. Our findings suggest that the process of separately recruiting for systems-level and prescriber-level interventions is challenging and costly. Our analysis of delivery cost was not able to isolate the cost of the combined intervention specifically, but given the sequential nature of our design, this cost can be estimated to be the additive cost of each intervention, or $1,726 per clinic on average. Thus, the combined intervention is likely advantageous only to the extent that its multi-level approach achieves improvements in HPV vaccination coverage that are larger than QI coaching or communication training alone. Indeed, given that other studies have found success by using bundled or multilevel interventions [37–41], we hypothesize that the combined intervention will yield improved outcomes, but forthcoming studies will make clear whether this is the case. In the meantime, our research underscores the aggregate cost of a multilevel intervention; HDs may elect to implement a less expensive, though potentially less impactful, intervention based on relative prioritization of HPV vaccination and their community needs.

Interestingly, we observed variation by state in the implementation of each intervention. For example, QI coaching adoption in the SW and NE states was very high, but lower in the MW state. Our prior qualitative work suggests that the MW state had difficulty with adoption due the high proportion of clinics in that state that were part of integrated delivery systems [28]. In these systems, clinic managers often lacked the authority to adopt QI coaching without permission from leaders in the corporate office, adding a layer of gatekeeping [28]. AFIX coaches may have similar difficulty achieving high adoption in states that have large healthcare systems that limit access to clinics, regardless of the intervention. However, despite low adoption, the MW state had higher total staff reach than the other states, which underscores the tension between adoption and reach that we observed between arms. By engaging the power structure of the systems, AFIX coaches may be able to attain greater reach, though at a cost. Given that primary care is rapidly consolidating in the US [42–44], understanding how to coordinate health departments’ QI efforts with integrated delivery systems should be a high-priority topic for future research. It is noteworthy, however, that we did not observe the same variation in adoption in the AAT arm; adoption of AAT was uniformly low across states.

Our findings have implications for state and regional health departments working to improve HPV vaccination coverage via IQIP, CDC’s current QI coaching program, which retains many of the same elements as AFIX, including a review of current coverage and provision of feedback and follow-up data. While QI coaching visits are a lower cost intervention, in the case of HPV vaccination, a greater effort dedicated to engage prescribers is needed, even if prescribers are unable to attend the whole session due to time constraints. Health departments could potentially increase prescriber-specific reach by incorporating incentives, such as offering Maintenance of Certification (MOC) Part 4 credit, working within existing QI infrastructure in healthcare systems, working with provider professional societies, or offering state-wide awards or public praise for meeting vaccination goals [10, 40, 45]. Physician communication training is a promising intervention for reaching prescribers [23, 30, 46, 47], but health departments must be ready to overcome recruitment challenges to adoption to make this a feasible option. For example, health departments would likely benefit from longer-term efforts to build relationships with large healthcare systems in their states to facilitate access to clinics; a recent study found that vaccine-related QI decision making occurs at multiple levels, including at the larger system level [48]. In addition, health departments could partner with organizations like the American Academy of Pediatrics and the American Cancer Society to facilitate relationships. Health systems could be important allies for improving immunization quality, but working with systems likely would require building different types of relationships over a longer timeline than the clinic-by-clinic approach most QI coaching programs have used in the past. Incorporating other implementation strategies, such as working with systems’ executive boards to integrate HPV vaccine-related QI coaching and physician communication training into existing QI efforts, may facilitate both reach and adoption. One recent study used learning collaboratives and other strategies including reminder-recall to improve vaccination outcomes [41].

Our study offers several strengths, including a strong study design and diverse study population. We employed a large, randomized implementation trial to test differences between arms and worked in geographically diverse states to understand variation in the implementation of our interventions. Our study also focused on medium- to high-volume pediatric and family medicine clinics, where most HPV vaccination takes place.

We also note several limitations. While the pediatric and family medicine clinics included in the study provide most HPV vaccine doses, the generalizability of our findings to alternative delivery settings, such as pharmacies or school health centers, is unknown. Additionally, our study focused on important implementation measures of adoption, reach, and cost, but we do not report on intervention fidelity or more down-stream implementation outcomes, such as the extent to which our interventions prompted changes in clinical teams’ communication or vaccine delivery systems. We note that particularly in the context of a QI coaching intervention, it is important to reach those with the authority to effect change in a clinic. We emphasized reach to prescribers to approximate that level of influence, but we acknowledge there are other staff who may also have the ability to effect change. The AFIX+AAT combination arm required more recruitment effort than the other arms, largely attributable to the two separate recruitment efforts to schedule each component done by AFIX coaches and study staff. Scheduling burdens may be eased if an attempt is made to schedule both sessions with one contact, though we anticipate that scheduling a combination session will still require more effort than a single session of AFIX or AAT. We calculated delivery cost from the perspective of health departments, who are charged with implementing these interventions, and did not account for the costs to clinics and prescribers for each intervention, such as prescribers’ time. Future research can extend the present study by evaluating the cost effectiveness of each intervention or the cost of each intervention from the clinic perspective, which was beyond the scope of the present study. It would also be helpful to have a more thorough understanding of the clinics that are being reached by QI interventions; future research into organizational readiness to change could provide greater insight into characteristics of adopting clinics.

Conclusions

In selecting clinic-based interventions to improve HPV vaccination coverage, health departments must balance a need for wider audience with prescribers and budgetary constraints. Our findings underscore the need to increase the reach of in-person QI coaching, while also exploring ways to make recruitment easier for the adoption of remote physician communication training. This goal is especially notable now, as the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the importance of remote interventions to improve healthcare quality. Health departments have an important mandate to support all clinics participating in their VFC programs, which is an admirable challenge with respect to both cost and logistics. We note that HDs will likely consider implementation outcomes in combination with vaccination outcome measures: each arm may have an differing impact with respect to outcomes such as vaccination coverage, and implementation outcomes must be weighed in context, based on HD priorities. Highly scalable interventions are critical for achieving this goal so that health departments can support primary care clinics in protecting their patients from future HPV cancers.

Acknowledgments

Funding for the project “Impact of AFIX and Physician-to-Physician Engagement on HPV Vaccination in Primary Care: An RCT” was provided to the UNC Department of Health Behavior, Gillings School of Global Public Health by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention through Cooperative Agreement U01IP001073-02. Author Brigid Grabert was funded by the Cancer Control Education Program at UNC Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center (T32CA057726-28).

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflicts of Interest: N.T. Brewer has served on paid advisory boards for Merck and received research grants from Merck and Pfizer. The remaining authors declare to no conflicts of interest.

Human Rights: This submission was reviewed by the Office of Human Research Ethics, which has determined that this submission does not constitute human subjects research as defined under federal regulations [45 CFR 46.102 (d or f) and 21 CFR 56.102(c)(e)(l)]. This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed Consent: This study does not involve human participants and informed consent was therefore not required.

Welfare of Animals: This study does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Transparency statements

Study registration: The study was pre-registered at ClinicalTrials.gov, at https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03442062.

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03442062; registered February 22, 2018.

Analytic plan pre-registration: The analysis plan was not formally pre-registered.

Data availability: De-identified data used and analyzed during this study are available in the openICPSR Project repository are available at https://doi.org/10.3886/E122722V1.

Analytic code availability: Analytic code used to conduct the analyses presented in this study are not available in a public archive. They may be available by emailing the corresponding author.

Materials availability: All materials used to conduct this study are available at https://www.hpviq.org.

References

- 1. Meites E, Kempe A, Markowitz LE. Use of a 2-dose schedule for human papillomavirus vaccination — updated recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(49):1405–1408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Elam-Evans LD, Yankey D, Singleton JA, et al. National, regional, state, and selected local area vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13–17 Years — United States, 2019. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(33):1109–1116. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/69/wr/mm6933a1.htm. Accessibility verified Apr 18, 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gilkey MB, Calo WA, Moss JL, Shah PD, Marciniak MW, Brewer NT. Provider communication and HPV vaccination: The impact of recommendation quality. Vaccine. 2016;34(9):1187–1192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kempe A, O’Leary ST, Markowitz LE, et al. HPV vaccine delivery practices by primary care physicians. Pediatrics. 2019;144(4):e20191475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Walker TY, Elam-Evans LD, Yankey D, et al. National, regional, state, and selected local area vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13–17 years - United States, 2018. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(33):718–723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. The Community Guide. Vaccination Programs: Standing Orders. 2016. Available at https://www.thecommunityguide.org/findings/vaccination-programs-standing-orders. Accessibility verified Jul 23, 2020.

- 7. Suh CA, Saville A, Daley MF, et al. Effectiveness and net cost of reminder/recall for adolescent immunizations. Pediatrics. 2012;129(6):e1437–e1445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sussman AL, Helitzer D, Bennett A, Solares A, Lanoue M, Getrich CM. Catching Up with the HPV Vaccine: challenges and opportunities in primary care. Ann Fam Med. 2015;13(4):354–360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Walling EB, Dodd S, Bobenhouse N, Reis EC, Sterkel R, Garbutt J. Implementation of strategies to improve Human Papillomavirus vaccine coverage: a provider survey. Am J Prev Med. 2019;56(1):74–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Grabert BK, Heisler-MacKinnon J, Liu A, Margolis MA, Cox ED, Gilkey MB. Prioritizing and implementing HPV vaccination quality improvement programs in healthcare systems: the perspective of quality improvement leaders. Hum Vaccines Immunother. 2021;17(12). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Drezner K, Heyer KP, McKeown L, Kan L. Experiences supporting local health departments to increase Human Papillomavirus vaccination rates. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2016;22(3):318–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lang A, Warren M, Kulman L. A funding crisis for public health and safety: state-by-state public health funding and key health facts and recommendations. Washington, DC; 2019. Available at https://www.tfah.org/report-details/a-funding-crisis-for-public-health-and-safety-state-by-state-and-federal-public-health-funding-facts-and-recommendations/. Accessibility verified Apr 18, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Weber L, Ungar L, Smith MR, Recht H, Barry-Jester AM. Hollowed-Out public health system faces more cuts amid virus. Kaiser Health News and The Associated Press. 2020. Available at https://khn.org/news/us-public-health-system-underfunded-under-threat-faces-more-cuts-amid-covid-pandemic/. Accessibility verified Apr 18, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (IQIP) Immunization Quality Improvement for Providers. 2021. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/programs/iqip/index.html. Accessibility verified Apr 18, 2021.

- 15. Gilkey MB, Dayton AM, Moss JL, et al. Increasing provision of adolescent vaccines in primary care: a randomized controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2014;134(2):e346–e353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Oliver K, McCorkell C, Pister I, Majid N, Benkel DH, Zucker JR. Improving HPV vaccine delivery at school-based health centers. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2019;15(7-8):1870–1877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Moss JL, Reiter PL, Dayton A, Brewer NT. Increasing adolescent immunization by webinar: a brief provider intervention at federally qualified health centers. Vaccine. 2012;30(33):4960–4963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Powell BJ, Waltz TJ, Chinman MJ, et al. A refined compilation of implementation strategies: results from the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) project. Implement Sci. 2015;10:21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. The Community Guide. Vaccination Programs: provider assessment and feedback. Community Preventive Services Task Force. 2016. Available at https://www.thecommunityguide.org/findings/vaccination-programs-provider-assessment-and-feedback. Accessibility verified Jul 23, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 20. LeBaron CW, Mercer JT, Massoudi MS, et al. Changes in clinic vaccination coverage after institution of measurement and feedback in 4 states and 2 cities. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999;153(8):879–886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Niccolai LM, Hansen CE. Practice- and community-based interventions to increase Human Papillomavirus vaccine coverage: a systematic review. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169(7):686–692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Malo TL, Hall ME, Brewer NT, Lathren CR, Gilkey MB. Why is announcement training more effective than conversation training for introducing HPV vaccination? A theory-based investigation. Implement Sci. 2018;13(1):57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Brewer NT, Hall ME, Malo TL, Gilkey MB, Quinn B, Lathren C. Announcements versus conversations to improve HPV vaccination coverage: a randomized trial. Pediatrics. 2017;139(1):e20161764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. HPV IQ at the UNC Gillings School of Global Public Health. HPV IQ: Communication Training Tools. HPV IQ Immunization Quality Improvement Tools. 2020. Available at https://www.hpviq.org/communication-training-tools/. Accessibility verified Apr 18, 2021.

- 25. Proctor E, Silmere H, Raghavan R, et al. Outcomes for implementation research: conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2011;38(2):65–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Glasgow RE, Vogt TM, Boles SM. Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: the RE-AIM framework. Am J Public Health. 1999;89(9):1322–1327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vaccines for Children Program (VFC). 2016. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/programs/vfc/index.html. Accessibility verified Nov 25, 2020.

- 28. Leeman J, Petermann V, Heisler-MacKinnon J, et al. Quality improvement coaching for Human Papillomavirus vaccination coverage: a process evaluation in 3 States, 2018–2019. Prev Chronic Dis. 2020;17:190410. doi: 10.5888/pcd17.190410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Brewer NT, Gilkey MB. Implementation of QI coaching versus physician communication training for improving HPV vaccination in primary care: a randomized implementation trial. Ann Arbor, MI: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research [distributor]; 2020. Available at 10.3886/E122722V1. Accessibility verified Apr 18, 2021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Calo WA, Gilkey MB, Leeman J, et al. Coaching primary care clinics for HPV vaccination quality improvement: comparing in-person and webinar implementation. Transl Behav Med. 2019;9(1):23–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gilkey MB, Moss JL, Roberts AJ, Dayton AM, Grimshaw AH, Brewer NT. Comparing in-person and webinar delivery of an immunization quality improvement program: a process evaluation of the adolescent AFIX trial. Implement Sci. 2014;9:21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Perkins RB, Zisblatt L, Legler A, Trucks E, Hanchate A, Gorin SS. Effectiveness of a provider-focused intervention to improve HPV vaccination rates in boys and girls. Vaccine. 2015;33(9):1223–1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Gargano LM, Herbert NL, Painter JE, et al. Impact of a physician recommendation and parental immunization attitudes on receipt or intention to receive adolescent vaccines. Hum Vaccine Immunother. 2013;9(12):2627–2633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Reiter PL, McRee AL, Pepper JK, Gilkey MB, Galbraith KV, Brewer NT. Longitudinal predictors of human papillomavirus vaccination among a national sample of adolescent males. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(8):1419–1427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Walling EB, Benzoni N, Dornfeld J, et al. Interventions to improve HPV vaccine uptake: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2016;138(1):e20153863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gunn R, Ferrara LK, Dickinson C, et al. Human Papillomavirus immunization in rural primary care. Am J Prev Med. 2020;59(3):377–385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Perkins RB, Legler A, Jansen E, et al. Improving HPV vaccination rates: a stepped-wedge randomized trial. Pediatrics. 2020;146(1):e20192737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Rand CM, Schaffer SJ, Dhepyasuwan N, et al. Provider communication, prompts, and feedback to improve HPV vaccination rates in resident clinics. Pediatrics. 2018;141(4):e20170498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Paskett ED, Krok-Schoen JL, Pennell ML, et al. Results of a multilevel intervention trial to increase Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Vaccine uptake among Adolescent Girls. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2016;25(4):593–602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Rand CM, Concannon C, Wallace-Brodeur R, et al. Identifying strategies to reduce missed opportunities for HPV Vaccination in primary care: a qualitative study of positive deviants. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2020;59(12):1058–1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Rand CM, Tyrrell H, Wallace-Brodeur R, et al. A learning collaborative model to improve Human Papillomavirus Vaccination rates in primary care. Acad Pediatr. 2018;18(2S):S46–S52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. American Academy of Pediatrics. Periodic Survey: Cross-survey results and findings. Available at https://www.aap.org/en-us/professional-resources/Research/pediatrician-surveys/Pages/Periodic-Survey-List-of-Surveys-and-Summary-of-Findings.aspx. Accessibility verified Aug 31, 2020.

- 43. Mostashari F. The paradox of size: how small, independent practices can thrive in value-based care. Ann Fam Med. 2016;14(1):5–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Muhlestein DB, Smith NJ. Physician consolidation: rapid movement from small to large group practices, 2013–15. Health Aff. 2016;35(9):1638–1642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Bonville CA, Domachowske JB, Suryadevara M. A quality improvement education initiative to increase adolescent human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine completion rates. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2019;15(7-8):1570–1576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Dempsey AF, Pyrznawoski J, Lockhart S, et al. Effect of a health care professional communication training intervention on Adolescent Human Papillomavirus Vaccination: a cluster randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatr. 2018;172(5):e180016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Zimet G, Dixon BE, Xiao S, et al. Simple and elaborated clinician reminder prompts for Human Papillomavirus Vaccination: a randomized clinical trial. Acad Pediatr. 2018;18(2S):S66–S71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Askelson NM, Ryan G, Seegmiller L, Pieper F, Kintigh B, Callaghan D. Implementation challenges and opportunities related to hpv vaccination quality improvement in primary care clinics in a rural state. J Commun Health. 2019;44(4):790–795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]