Abstract

Aldehyde dehydrogenase 2 (ALDH2) catalyses aldehyde species, including alcohol metabolites, mainly in the liver. We recently observed that ALDH2 is also expressed in skeletal muscle mitochondria; thus, we hypothesize that rs671 polymorphism-promoted functional loss of ALDH2 may induce deleterious effects in human skeletal muscle. We aimed to clarify the association of the ALDH2 rs671 polymorphism with muscle phenotypes and athletic capacity in a large Japanese cohort. A total of 3,055 subjects, comprising 1,714 athletes and 1,341 healthy control subjects (non-athletes), participated in this study. Non-athletes completed a questionnaire regarding their exercise habits, and were subjected to grip strength, 30-s chair stand, and 8-ft walking tests to assess muscle function. The ALDH2 GG, GA, and AA genotypes were detected at a frequency of 56%, 37%, and 7% among athletes, and of 54%, 37%, and 9% among non-athletes, respectively. The minor allele frequency was 25% in athletes and 28% in controls. Notably, ALDH2 genotype frequencies differed significantly between athletes and non-athletes (genotype: p = 0.048, allele: p = 0.021), with the AA genotype occurring at a significantly lower frequency among mixed-event athletes compared to non-athletes (p = 0.010). Furthermore, non-athletes who harboured GG and GA genotypes exhibited better muscle strength than those who carried the AA genotype (after adjustments for age, sex, body mass index, and exercise habits). The AA genotype and A allele of the ALDH2 rs671 polymorphism were associated with a reduced athletic capacity and poorer muscle phenotypes in the analysed Japanese cohort; thus, impaired ALDH2 activity may attenuate muscle function.

Keywords: Single nucleotide polymorphism, Mitochondrial aldehyde, dehydrogenase 2, Athlete status, Muscle function, Phenotype

INTRODUCTION

Athletic performance phenotypes are complex and dependent upon numerous environmental and genetic factors, among which heritability estimates 66% of athletic performance [1]. The relationship between certain genetic polymorphisms and athletic performance, muscle phenotypes and response to physical training has recently been reported [2]. Of these polymorphisms, the most studied ones are the α-actinin-3 gene (ACTN3) R577X genotype and ACE I/D genotype [3], including a range of known genetic polymorphisms that occur at different frequencies in various ethnic populations [2]. For example, the rs671 polymorphism in mitochondrial aldehyde dehydrogenase 2 (ALDH2), which introduces an ‘A’ allele that impairs ALDH2 activity resulting in a decrease of enzyme activity, is unique to Asian populations.

ALDH2 is highly expressed in the heart and liver, and is a major driver of toxic aldehyde metabolism. Moreover, 30–50% of East Asians possess an ALDH2 single nucleotide polymorphism, which is responsible for an alcohol-flush reaction due to the poor metabolism of ethanol resulting from substantial loss of ALDH2 enzymatic activity in heterozygotes (GA genotype) and homozygotes (AA genotype) carrying the ALDH2 rs671 polymorphism [4]. Previous studies have confirmed that the ALDH2 rs671 polymorphism is associated with body mass index (BMI) [5], hypertension [6], and cancer [7], likely because inactivated ALDH2 has a reduced capacity to attenuate oxidative stress. In addition, some evidence suggests that ALDH2 protects against cardiovascular disease through detoxification of endogenous lipid aldehydes, such as 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal [8].

We recently observed that ALDH2 is also expressed in skeletal muscle mitochondria, and that ALDH2-deficient mice exhibit increased mitochondrial reactive oxidative stress (ROS) emission [9]; thus, we hypothesized that the ALDH2 rs671 polymorphism may incur deleterious effects in human skeletal muscle.

Therefore, the present study assessed whether and how the ALDH2 rs671 polymorphism and ALDH2 genotypes are associated with athletic performance, muscle function, and muscle phenotypes in a large Japanese cohort.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

The present study enrolled 3,055 Japanese subjects, comprising 1,714 athletes (1,161 men and 553 women), among whom 433 were elite athletes (350 men and 183 women) who have participated in international competitions, and 1,341 healthy controls (non-athletes; 538 men and 803 women). The athletes were divided into three groups as follows: (i) sprint/power athletes (609 men and 213 women), comprising 100–400 m-track (n = 185), jumping and throwing (n = 25), weightlifting (n = 192), wrestling (n = 115), gymnast (n = 98), combat sports (n = 92), body building (n = 36), sprint kayak and canoe (n = 64), and others (n = 15); (ii) mixed athletes (418 men and 283 women), comprising American football (n = 62), baseball (n = 78), basketball (n = 93), volleyball (n = 36), handball (n = 45), rugby (n = 34), soccer (n = 327), and others (n = 26); and (iii) endurance athletes (134 men and 57 women), including more than 1,500 m track (n = 135), triathlon (n = 46), and long distance cycling (n = 10). The non-athletes completed a questionnaire regarding their exercise habits and comprised healthy Japanese subjects from Tokyo and surrounding areas. All subjects provided written informed consent for their participation in the study, which was approved by the Nippon Sport Science University ethics committee, and conducted in strict accordance with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Genotyping

Total DNA was extracted from saliva samples using an Oragene-DNA Kit (DNA Genotek, Ontario, Canada) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The ALDH2 rs671 polymorphism was identified via TaqMan SNP Genotyping Assay (C__590093_1_) that was conducted using the TaqMan Real-Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA).

Fitness testing

To evaluate upper-extremity muscle strength, grip strength was assessed using a Hand Grip Dynamometer (Takei Scientific Instruments Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). To evaluate lower-extremity muscle function, subjects underwent the chair stand test (i.e. subjects were scored on the number of times they were able to alternately sit and return to a full standing position in 30 s). Agility and dynamic balance were assessed via the 8-ft walking test, (i.e. subjects were scored on the time it took them to rise from a seated position on a chair, walk 2.4 m, turn, and return to a seated position on the chair). All tests were conducted using standard protocols [10].

Questionnaire on exercise habits

All subjects completed an original questionnaire on exercise habits, which included questions related to the type, duration, and frequency of physical activity. The options for the responses regarding the frequency of activity were as follows: “never”, “once a week”, or “≥ twice a week”. The subjects who answered “≥ twice a week” were considered to have exercise habits.

Statistical analysis

The SPSS statistical package version 16.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used to perform all statistical evaluations. Pearson’s χ2 test was performed to assess the conformance of the observed genotype frequencies to Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium, frequency of genotype/allele, dominant model (GG+GA vs. AA), and recessive model (GG vs. GA+AA) in athletes compared to non-athletes. We examined the association of the ALDH2 rs671 genotype with subject muscle-function-test scores using a one-way analysis of variance and an analysis of covariance (adjusted for sex, age, BMI, and exercise habits). P-values < 0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance.

RESULTS

The ALDH2 genotype frequencies were found to be in Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium among the athletes and non-athletes; specifically, the ALDH2 GG, GA, and AA genotypes were detected in 56%, 37%, and 7% of the athletes, respectively, and in 54%, 37%, and 9% of the non-athletes, respectively. The minor allele frequency was 25% in athletes and 28% in controls. Notably, the AA genotype and A allele frequencies were significantly lower in the athletes than in non-athletes (Table 1, genotype, p = 0.048; dominant model, p = 0.023; allele, p = 0.021). Furthermore, the ALDH2 AA genotype was found to occur at a significantly lower frequency among mixed-event athletes compared to non-athletes (p = 0.010). No gender difference was observed among athletes regarding the ALDH2 genotype frequency (Table 2).

TABLE 1.

The genotype and allele frequency of ALDH2 rs671 polymorphism in athletes and non-athletes

| N | Genotype |

Allele |

P value |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GG n (%) | GA n (%) | AA n (%) | G n (%) | A n (%) | Genotype | Dominant | Recessive | Allele | ||

| Athlete | 1714 | 964(56) | 630(37) | 120(7) | 2558(75) | 870(25) | 0.048 | 0.023 | 0.097 | 0.021 |

| Sprint/Power | 822 | 465(57) | 292(36) | 65(7) | 1222(74) | 752(26) | 0.269 | 0.288 | 0.130 | 0.094 |

| Mix | 701 | 391(56) | 268(38) | 42(6) | 1050(75) | 352(25) | 0.037 | 0.010 | 0.274 | 0.048 |

| Endurance | 191 | 108(56) | 70(37) | 13(7) | 286(75) | 96(25) | 0.477 | 0.271 | 0.391 | 0.241 |

|

| ||||||||||

| Non-athlete | 1341 | 715(53) | 502(40) | 124 (9) | 1934(72) | 752(28) | ||||

| Men | 538 | 274(51) | 218(40) | 46(9) | 766(1) | 310(29) | ||||

| Women | 803 | 441(55) | 284(35) | 78(10) | 1166(73) | 440(27) | ||||

Dominant model; GG+GA vs. AA, Recessive model; GG vs. GA+AA

TABLE 2.

The genotype frequency of ALDH2 rs671 polymorphism in men and women in each athletic events.

| N | Genotype |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GG n (%) | GA n (%) | AA n (%) | P value men vs. women | ||

| Sprint/Power | 822 | 465(57) | 292(36) | 65(7) | 0.604 |

| Men | 609 | 346(57) | 212(35) | 51(8) | |

| Women | 213 | 119(56) | 80(37) | 14(7) | |

|

| |||||

| Mix | 701 | 391(56) | 268(38) | 42(6) | 0.541 |

| Men | 418 | 235(56) | 154(37) | 29(7) | |

| Women | 283 | 156(55) | 114(40) | 13(5) | |

|

| |||||

| Endurance | 191 | 108(56) | 70(37) | 13(7) | 0.348 |

| Men | 134 | 79(59) | 47(35) | 8(6) | |

| Women | 57 | 29(51) | 23(40) | 5(9) | |

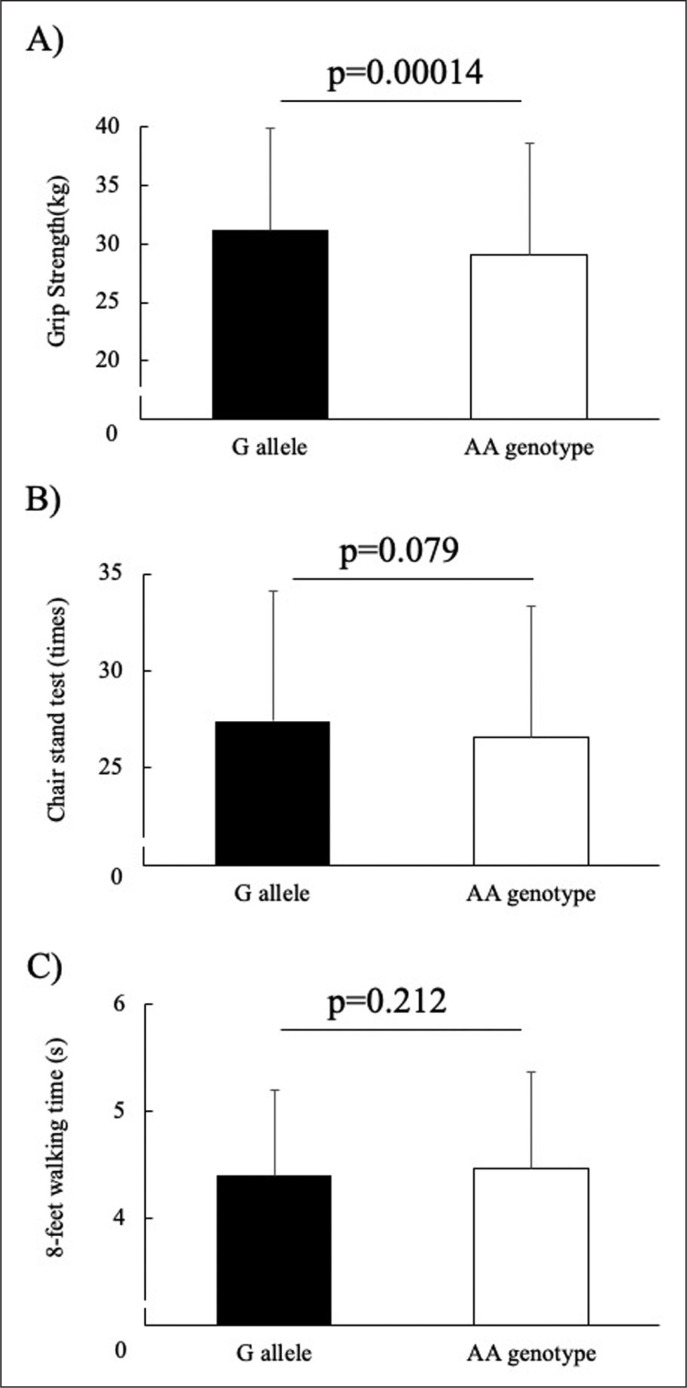

Among the non-athletes, no significant differences in age, height, body mass or BMI were observed between individuals harbouring each of the three ALDH2 genotypes (Table 3). A significant difference in grip strength (p = 0.002) and 30-s chair stand test (p = 0.011) was observed after adjusting for age, sex, BMI, and exercise habits (Table 4). In addition, subjects carrying the GG and GA genotypes achieved significantly higher grip strength (p = 0.00014) and non-significantly higher 30-s chair stand test scores (p = 0.079) than those carrying the AA genotype after adjustments for age, sex, BMI and exercise habits (Fig. 1).

TABLE 3.

Characteristics of Japanese non-athletes among ALDH2 genotype (n = 1,341)

| Genotype |

P value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GG (n = 715) | GA (n = 502) | AA (n = 124) | ||

| Age (year) | 50.5 ± 18.4 | 49.8 ± 18.7 | 48.3 ± 20.3 | 0.467 |

| Height (cm) | 161.8 ± 9.3 | 162.2 ± 9.3 | 160.7 ± 9.3 | 0.235 |

| Body Mass (kg) | 58.0 ± 11.1 | 58.7 ± 11.2 | 58.1 ± 11.5 | 0.575 |

| BMI (kg•m-2) | 22.0 ± 2.9 | 22.1 ± 3.0 | 22.1 ± 2.9 | 0.864 |

| % fat (%) | 23.2 ± 7.8 | 23.1 ± 7.7 | 24.3 ± 8.4 | 0.262 |

| Exercise habit, yes (%) | 33.1 | 39.7 | 30.9 | 0.109* |

Data are shown as the mean ± SD. BMI: Body mass index.

chi-square test.

TABLE 4.

Muscle strength and walking ability by ALDH2 genotype in the Japanese non-athletes (n = 1,341)

| Genotype | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All (n = 1341) | GG (n = 715) | GA (n = 502) | AA (n = 124) | P value | P value* |

| Grip strength (kg) | 30.9 ± 9.34 | 31.7 ± 9.5 | 28.9 ± 8.8 | 0.010 | 0.002 |

| Stand up test (times) | 27.6 ± 6.9 | 27.1 ± 6.7 | 26.2 ± 7.4 | 0.084 | 0.011 |

| 8-feet walking time (s) | 4.37 ± 0.90 | 4.42 ± 0.87 | 4.39 ± 1.07 | 0.689 | 0.063 |

| Men (n = 538) | GG (n = 274) | GA (n = 218) | AA (n = 46) | P value | P value† |

| Grip strength (kg) | 40.3 ± 7.0 | 40.2 ± 7.3 | 37.5 ± 7.3 | 0.052 | 0.082 |

| Stand up test (times) | 28.8 ± 6.3 | 28.3 ± 6.7 | 27.0 ± 7.1 | 0.218 | 0.208 |

| 8-feet walking time (s) | 4.10 ± 0.87 | 4.22 ± 0.91 | 4.27 ± 0.99 | 0.257 | 0.137 |

| Women (n = 803) | GG (n = 441) | GA (n = 284) | AA (n = 78) | P value | P value† |

| Grip strength (kg) | 24.9 ± 4.5 | 25.1 ± 4.4 | 24.0 ± 5.1 | 0.145 | 0.020 |

| Stand up test (times) | 27.0 ± 6.9 | 26.2 ± 6.6 | 26.0 ± 7.2 | 0.245 | 0.058 |

| 8-feet walking time (s) | 4.53 ± 0.88 | 4.58 ± 0.80 | 4.51 ± 1.00 | 0.703 | 0.367 |

Data are shown as the mean ± SD.

ANCOVA adjusted by sex, age, BMI and exercise habit.

ANCOVA adjusted by age, BMI and exercise habit.

Fig. 1.

Associations between the ALDH2 rs671 genotype (GG+GA vs. AA) and A) grip strength, B) chair stand test, and C) 8-feet walking time in non-athletes. The data were assessed by analysis of covariance with adjustments for age, sex, body mass index, and exercise habits as covariates. Data are represented as mean ± standard deviation.

DISCUSSION

This study is the first to examine the association of ALDH2 rs671 polymorphism with athletic performance and muscle function in an Asian population. The frequency of ALDH2 rs671 genotype observed herein is similar to those reported for other Japanese population groups [11]. The conducted analyses showed that the ALDH2 AA genotype occurred at a lower frequency among (particularly mixed-event) athletes compared to non-athletes. Furthermore, ALDH2 rs671 polymorphism was significantly associated with muscle functionality (as indicated by the results of the conducted grip strength and 30-s chair stand tests). Together, these data indicate that the AA genotype and A allele of the ALDH2 rs671 polymorphism were associated with a reduced athletic capacity and poorer muscle phenotypes in the analysed Japanese population.

Mitochondrial ALDH2 not only drives alcohol metabolism, but also scavenges reactive aldehyde products. Transgenic mice overexpressing ALDH2*2 proteins encoded by the ALDH2 A allele have been shown to exhibit a reduced muscle mass [12], which suggests that ALDH2 inactivation both impairs mitochondrial function and promotes muscle loss. Consistent with this, we recently observed that ALDH2-deficient mice exhibit high levels of skeletal muscle mitochondrial ROS emission [9]. Together, these data suggest that reduced ALDH2 activity impairs mitochondrial function in skeletal muscle. The reduced representation of the ALDH2 A allele among athletes compared to non-athletes observed herein is consistent with this hypothesis, as high intensity intermittent exercise has been shown to induce high levels of oxidative stress [13].

The A allele in ALDH2 rs671 also showed a correlation with lower BMI in a genome-wide association study in east Asian populations. In addition, it was associated with higher risk of coronary heart disease [14], increased alcohol-flushing response, and oesophageal cancer [15]. Furthermore, the AA genotype was also significantly associated with osteoporosis development and hip fracture [16], and promotes low bone mineral density in mice [17]. Thus, the AA genotype and A allele of ALDH2 rs671 may promote lower muscle function in athletes and general populations via several mechanisms.

Among the non-athletes, individuals carrying the ALDH2 AA genotype showed significantly reduced muscle functions compared to those carrying the ALDH2 G allele (Fig. 1). This is likely because the AA genotype impairs mitochondrial function in skeletal muscle, since mitochondrial functionality has been shown to be strongly associated with skeletal muscle health [18]. Interestingly, ALDH2 activation has been shown to protect against neurodegeneration in a Parkinson’s disease model; thus, ALDH2 inactivation has been suggested to reduce muscle function in this context by impairing alpha-motor neuron excitability [19]. Considering both these data and the findings presented herein, we suggest that the ALDH2 rs671 polymorphism, and particularly the ALDH2 AA genotype, reduce ALDH2 activity, and thereby impair muscle function and athletic capacity.

Mitochondrial superoxide dismutase (SOD2) is also a major antioxidant gene. Recently, Akimoto et al. [20] demonstrated that athletes with the SOD2 TT genotype of the rs4880 polymorphism had increased creatinine kinase levels after racing, suggesting that the CC genotype is associated with lower muscle damage. Interestingly, Ben-Zaken et al. [21] found that the frequency of the SOD2 C allele was significantly higher in Israeli athletes compared with controls. In line with these studies, Ahmetov et al. [22] reported that the CC and CT genotypes in SOD2 were over-represented in athletes involved in high-intensity sports (power and strength) compared with controls and low-intensity athletes. Therefore, application of high-throughput technologies, such as genome-wide association studies using nextgeneration whole genome and/or exome sequencing, is warranted to help uncover these multiple genetic effects.

Our study has several limitations. First, we could not control for external factors, such as the presence of comorbidities or medications, which could have influenced the results of our muscle function test in non-athletes. Longitudinal studies are necessary to explain the effect of the ALDH2 rs671 polymorphism in response to aging and physical training. In addition to the effects of this polymorphism, multiple other genetic polymorphisms, such as SOD2 rs4880, and environmental factors can probably interact and influence muscle function.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, our results suggest that the AA genotype and A allele of the ALDH2 rs671 polymorphism are under-represented in athletes and are associated with poorer muscle phenotypes in a Japanese cohort.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by the grants from the programme Grantsin-Aid for Scientific Research (C) (19K11531 to N.K.)

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

REFERENCES

- 1.De Moor MH, Spector TD, Cherkas LF, et al. Genome-wide linkage scan for athlete status in 700 British female DZ twin pairs. Twin Res Hum Genet. 2007;10:812–820. doi: 10.1375/twin.10.6.812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahmetov II, Fedotovskaya ON. Current Progress in Sports Genomics. Adv Clin Chem. 2015;70:247–314. doi: 10.1016/bs.acc.2015.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ma F, Yang Y, Li X, et al. The association of sport performance with ACE and ACTN3 genetic polymorphisms: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2013;8:e54685. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xiao Q, Weiner H, Crabb DW. The mutation in the mitochondrial aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH2) gene responsible for alcohol-induced flushing increases turnover of the enzyme tetramers in a dominant fashion. J Clin Invest. 1996;98:2027–2032. doi: 10.1172/JCI119007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wen W, Zheng W, Okada Y, et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies in East Asian-ancestry populations identifies four new loci for body mass index. Hum Mol Genet. 2014;23:5492–5504. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddu248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wu Y, Ni J, Cai X, et al. Positive association between ALDH2 rs671 polymorphism and essential hypertension: A case-control study and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0177023. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0177023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zuo W, Zhan Z, Ma L, et al. Effect of ALDH2 polymorphism on cancer risk in Asians: A meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2019;98:e14855. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000014855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guo JM, Liu AJ, Zang P, Dong WZ, Ying L, Wang W, Xu P, Song XR, Cai J, Zhang SQ, et al. ALDH2 protects against stroke by clearing 4-HNE. Cell Res. 2013;23:915–930. doi: 10.1038/cr.2013.69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wakabayashi Y, Tamura Y, Kouzaki K, et al. Acetaldehyde dehydrogenase 2 deficiency increases mitochondrial reactive oxygen species emission and induces mitochondrial protease Omi/HtrA2 in skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2020;318:R677–R690. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00089.2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kikuchi N, Yoshida S, Min SK, et al. The ACTN3 R577X genotype is associated with muscle function in a Japanese population. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2015;40:316–322. doi: 10.1139/apnm-2014-0346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Masaoka H, Ito H, Gallus S, et al. Combination of ALDH2 and ADH1B polymorphisms is associated with smoking initiation:A large-scale cross-sectional study in a Japanese population. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017;173:85–91. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Endo J, Sano M, Katayama T, et al. Metabolic remodeling induced by mitochondrial aldehyde stress stimulates tolerance to oxidative stress in the heart. Circ Res. 2009;105:1118–1127. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.206607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Magherini F, Fiaschi T, Marzocchini R, et al. Oxidative stress in exercise training:the involvement of inflammation and peripheral signals. Free Radic Res. 2019;53:1155–1165. doi: 10.1080/10715762.2019.1697438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Takeuchi F, Yokota M, Yamamoto K, et al. Genome-wide association study of coronary artery disease in the Japanese. Eur J Hum Genet. 2012;20:333–340. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2011.184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang SJ, Yokoyama A, Yokoyama T, et al. Relationship between genetic polymorphisms of ALDH2 and ADH1B and esophageal cancer risk:a meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:4210–4220. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i33.4210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Takeshima K, Nishiwaki Y, Suda Y, et al. A missense single nucleotide polymorphism in the ALDH2 gene, rs671, is associated with hip fracture. Sci Rep. 2017;7:428. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-00503-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoshi H, Hao W, Fujita Y, et al. Aldehyde-stress resulting from Aldh2 mutation promotes osteoporosis due to impaired osteoblastogenesis. J Bone Miner Res. 2012;27:2015–2023. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Romanello V, Sandri M. Mitochondrial Quality Control and Muscle Mass Maintenance. Front Physiol. 2015;6:422. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2015.00422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chiu CC, Yeh TH, Lai SC, et al. Neuroprotective effects of aldehyde dehydrogenase 2 activation in rotenone-induced cellular and animal models of parkinsonism. Exp Neurol. 2015;263:244–253. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2014.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Akimoto AK, Miranda-Vilela AL, Alves PC, et al. Evaluation of gene polymorphisms in exercise-induced oxidative stress and damage. Free Radic Res. 2010;44:322–331. doi: 10.3109/10715760903494176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ben-Zaken S, Eliakim A, Nemet D, et al. Increased prevalence of MnSOD genetic polymorphism in endurance and power athletes. Free Radic Res. 2013;47:1002–1008. doi: 10.3109/10715762.2013.838627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ahmetov II, Naumov VA, Donnikov AE, et al. SOD2 gene polymorphism and muscle damage markers in elite athletes. Free Radic Res. 2014;48:948–955. doi: 10.3109/10715762.2014.928410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]