Abstract

Early-onset sepsis caused by Gram-negative spiral organisms is rarely reported, with Campylobacter fetus being a better known causative agent than other Campylobacter species. We report the case of a 2-day-old girl who presented with hematochezia and bacteremia caused by Campylobacter jejuni. She was born full-term. Her family ate undercooked chicken, and Campylobacter enteritis was diagnosed before her birth.

Keywords: Campylobacter jejuni, Gram-negative spiral bacteremia, early-onset sepsis, neonatal hematochezia, food handling practice for pregnant women

Pathogens commonly causing early-onset sepsis in developed countries are Group B streptococcus and Escherichia coli.1,2 Campylobacter fetus is known as a rare cause of Gram-negative spiral bacteremia in neonates, with bacteremia caused by other Campylobacter species even more infrequently reported.3,4

Pregnant women are considered to be a high-risk group for Campylobacter infection, and in the general population, bacteremia is reported to occur in 0.1%–1% of campylobacteriosis cases.5–7 Campylobacter enteritis during pregnancy occurs often, but its effects on the neonate remain unknown.8,9 Few guidelines focus on the management of food safety risks and Campylobacter infections.5

We report here a case of early-onset sepsis caused by Campylobacter jejuni manifesting as mucoid and bloody diarrhea in a full-term healthy infant. After careful history taking, it was found that her family had eaten undercooked chicken, and her mother and older brother exhibited symptoms of fever and watery diarrhea before her birth. C. jejuni was isolated from her brother’s stool. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Japanese Red Cross Wakayama Medical Center (no. 873).

CASE REPORT

A 2-day-old girl was admitted to our hospital with bloody diarrhea containing mucous (Fig. 1). The neonate had been delivered normally at the gestational age of 37 weeks and 6 days to a 27-year-old woman (gravida 2, para 1). The pregnancy was uneventful. Her birth weight was 2880 g and Apgar scores were 9 at 1 minute and 10 at 5 minutes. Meconium staining was not found. She developed mucoid and bloody diarrhea on 1 day of life. On examination, she appeared well: temperature, 37.5 °C; pulse, 140 beats per minute; blood pressure, 81/53 mm Hg; respiratory rate, 50 breaths per minute; and oxygen saturation, 96% on ambient air. She lost 7.6% of her birth weight during the first 2 days of her life. There was no evidence of dehydration. Her cardiovascular examination was normal, lungs were clear by auscultation, and abdominal examination was unremarkable. Neurologic examination was also unremarkable and no skin lesions were apparent. On admission, initial investigations revealed elevated total bilirubin (189.8 μmol/L) and direct bilirubin (12.0 μmol/L); otherwise, her results were unremarkable for this day of life (Table 1). At 2 days after admission, a blood culture taken on admission was positive for Gram-negative spiral organisms (Fig. 2). The patient was started on meropenem on suspicion of C. fetus infection. The next day, the blood culture isolate was identified as C. jejuni. We took stool and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) samples before administration of antibiotics. The stool culture was positive for C. jejuni, but the cerebrospinal fluid culture was negative. CSF examination revealed the following: 9 cells/mm3; protein concentration, 910 g/L; glucose level, 2.7 mmol/L. Thus, the patient was diagnosed with C. jejuni bacteremia, and we stopped meropenem and started intravenous azithromycin for 5 days. Her bloody diarrhea improved in 4 days, and she was discharged without any complications at 10 days postadmission. Outpatient follow-up at 5 months postdiagnosis revealed no problems. A dialogue established that undercooked chicken was consumed by the mother and older brother 10 days before her birth and that they both developed fever with watery diarrhea 7 days before her birth. The mother received neither medical attention nor antibiotics before delivery.

FIGURE 1.

The patient’s mucoid and bloody diarrhea on the day of admission.

TABLE 1.

Laboratory findings on admission

| Hematology | Biochemistry | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WBC | 1.15 × 109 | /L | TP | 56 | g/L |

| Lym | 15.7 | % | Alb | 33 | g/L |

| Mon | 10.2 | % | CK | 200 | U/L |

| Eos | 1.0 | % | AST | 26 | U/L |

| Bas | 0.1 | % | ALT | 8 | U/L |

| RBC | 6.19 × 1012 | /L | TB | 189.8 | µmol/L |

| Hb | 217 | g/L | DB | 12.0 | µmol/L |

| Ht | 0.64 | L/L | LD | 376 | U/L |

| PLT | 22.5 × 109 | /L | UN | 2.6 | mmol/L |

| Cr | 63.6 | µmol/L | |||

| Serology | Na | 145 | mmol/L | ||

| CRP | 1.7 | mg/L | K | 4.1 | mmol/L |

| IgG | 9230 | mg/L | Cl | 110 | mmol/L |

| IgM | 100 | mg/L | Glu | 5.0 | mmol/L |

Alb indicates albumin; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; Bas, basophil; CK, creatinine kinase; Cl, chloride; Cr, creatinine; CRP, C-reactive protein; DB, direct bilirubin; Eos, eosinophil; Glu, glucose; Hb, hemoglobin; Ht, hematocrit; IgG, immunoglobulin G; IgM, immunoglobulin M; K, potassium; LD, lactate dehydrogenase; Lym, lymphocyte; Mon, monocyte; Na, sodium; PLT, platelet; RBC, red blood cell; TB, total bilirubin; TP, total protein; UN, urea nitrogen; WBC, white blood cell.

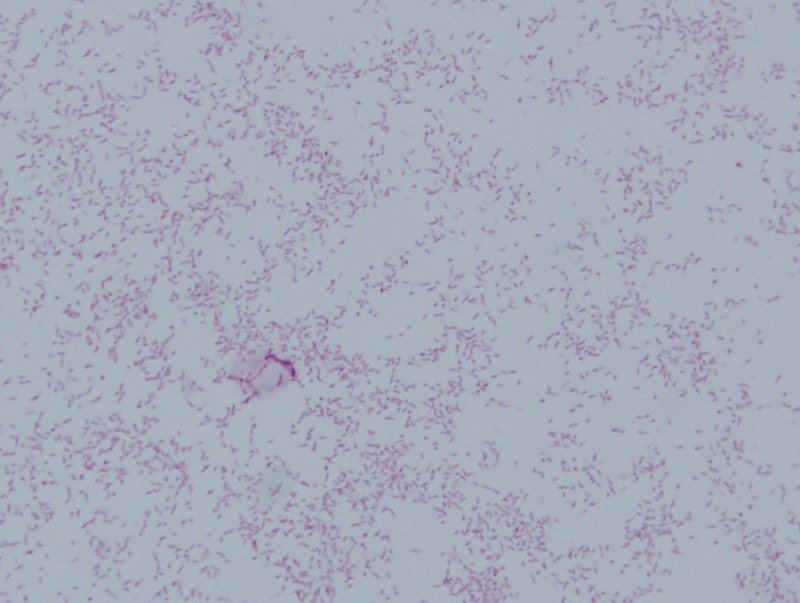

FIGURE 2.

Gram-negative spiral organisms in blood culture smear.

DISCUSSION

We learned the following important lessons. First, C. jejuni can cause a Gram-negative spiral bacteremia as a neonatal early-onset sepsis defined as the onset of symptoms before 7 days of age. Second, taking a family and dietary history is key to diagnosis. Third, recommendations concerning kitchen food handling practices should be provided routinely to pregnant women.

Early-onset sepsis in term infants is decreasing and Gram-negative spiral organisms are rare pathogens.1,2 Campylobacter fetus is better known as a cause of neonatal bacteremia than C. jejuni, and in C. fetus infections the outcome for the fetus is frequently death.3,4 Several studies show that Campylobacter bacteremia is more common in previously healthy young children or older immunocompromised patients.7,10,11 The outcome after C. jejuni bacteremia is usually favorable. The estimated mortality rate in children is very low; however, relapsing Campylobacter bacteremia has been reported in cases of humoral immunodeficiency, such as X-linked agammaglobulinemia.7,10,11 Some previous studies report C. jejuni that is resistant to third-generation cephalosporins, fluoroquinolones and macrolides. However, they may be sensitive to aminoglycosides and carbapenems.12,6 Thus, early initiation of carbapenem antibiotics is recommended. In this patient, symptoms were mild with hematochezia and her prognosis was good after treatment with azithromycin.

Family and dietary history taking was important for diagnosis. C. jejuni is one of the most common pathogens that cause enterocolitis in developed countries. By contrast, bacteremia is relatively rare. Abdominal pain with or without diarrhea is reported in at least half of the patients.8,9 All patients should be asked about potential epidemiologic risk factors for particular diarrheal diseases and their transmission, including consumption of unsafe foods and contact with ill people. For Campylobacter enteritis, undercooked chicken is considered the most likely contaminated food vehicle. While the risk of infection with Toxoplasma gondii and Listeria monocytogenes in pregnant women is mentioned in some guidelines, Campylobacter infection in pregnant women receives less attention.5 In addition to usual good food handling practices, including washing hands thoroughly with soap and clean running water, all meat, especially chicken, should be cooked to an adequate temperature of 75°C or higher.

In conclusion, C. jejuni can cause early-onset sepsis, and taking a family and dietary history is key to diagnosis. We must be aware that C. jejuni enteritis in the mother can affect her neonate via vertical transmission. Effective food handling recommendations should be provided to prevent mother-to-child transmission of C. jejuni.

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Japanese Red Cross Wakayama Medical Center (no. 873).

REFERENCES

- 1.Puopolo KM, Benitz WE, Zaoutis TE; Committee on Fetus and Newborn; Committee on Infectious Diseases. Management of neonates born at ≤34 6/7 weeks’ gestation with suspected or proven early-onset bacterial sepsis. Pediatrics. 2018;142:e20182896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van den Hoogen A, Gerards LJ, Verboon-Maciolek MA, et al. Long-term trends in the epidemiology of neonatal sepsis and antibiotic susceptibility of causative agents. Neonatology. 2010;97:22–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pacanowski J, Lalande V, Lacombe K, et al. ; CAMPYL Study Group. Campylobacter bacteremia: clinical features and factors associated with fatal outcome. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47:790–796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Simor AE, Karmali MA, Jadavji T, et al. Abortion and perinatal sepsis associated with campylobacter infection. Rev Infect Dis. 1986;8:397–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guerrant RL, Van Gilder T, Steiner TS, et al. ; Infectious Diseases Society of America. Practice guidelines for the management of infectious diarrhea. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32:331–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Feodoroff B, Lauhio A, Ellström P, et al. A nationwide study of Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli bacteremia in Finland over a 10-year period, 1998-2007, with special reference to clinical characteristics and antimicrobial susceptibility. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53:e99–e106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Skirrow MB, Jones DM, Sutcliffe E, et al. Campylobacter bacteraemia in England and Wales, 1981-91. Epidemiol Infect. 1993;110:567–573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wong SN, Tam AY, Yuen KY. Campylobacter infection in the neonate: case report and review of the literature. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1990;9:665–669. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hirschel J, Herzog D, Kaczala GW. Rectal bleeding in neonates due to campylobacter enteritis: report of 2 cases with a review of the literature. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2018;57:344–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Allos BM. Campylobacter jejuni infections: update on emerging issues and trends. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32:1201–1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ben-Shimol S, Carmi A, Greenberg D. Demographic and clinical characteristics of Campylobacter bacteremia in children with and without predisposing factors. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2013;32:e414–e418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fernández-Cruz A, Muñoz P, Mohedano R, et al. Campylobacter bacteremia: clinical characteristics, incidence, and outcome over 23 years. Medicine (Baltimore). 2010;89:319–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]