Introduction

The genus Mycobacterium encompasses almost 200 species that fall into four main groups [1]. Specifically, the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex (MTBC), the causative agent of tuberculosis (TB) and leading cause of death by a single infectious agent, is distinguished from mycobacteria causing Buruli ulcer and leprosy [2, 3]. The remaining species are referred to as nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM), which mainly cause lung disease and have become more frequent in many parts of the world, particularly amongst older patients [4].

The toolbox for the laboratory diagnosis of mycobacteria

The microbiological diagnosis of mycobacteria consists of four main pillars: detection, identification, antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST) and cluster analysis [5]. Traditionally, microscopy is first employed to detect high numbers of acid-fast bacilli (AFB) in clinical samples (usually sputum). A culture is also inoculated that may turn positive within days to weeks, depending on the mycobacterial species and bacterial load. At this point, rapid identification to the species level is performed. For most NTM, this is the last diagnostic step as the appropriate empiric treatment can typically be inferred based on the species identification alone [2]. By contrast, routine AST is needed when the in vitro activity of a drug predicts in vivo outcomes and there are significant rates of resistance to a particular agent [2]. Both criteria are met for some NTM and are particularly important for MTBC [6]. Finally, some well-resourced countries routinely conduct cluster analyses to inform TB control authorities [7]. More recently, cluster analyses have been extended to Mycobacterium abscessus and Mycobacterium intracellulare subsp. chimaera [8, 9].

A tale of compromises

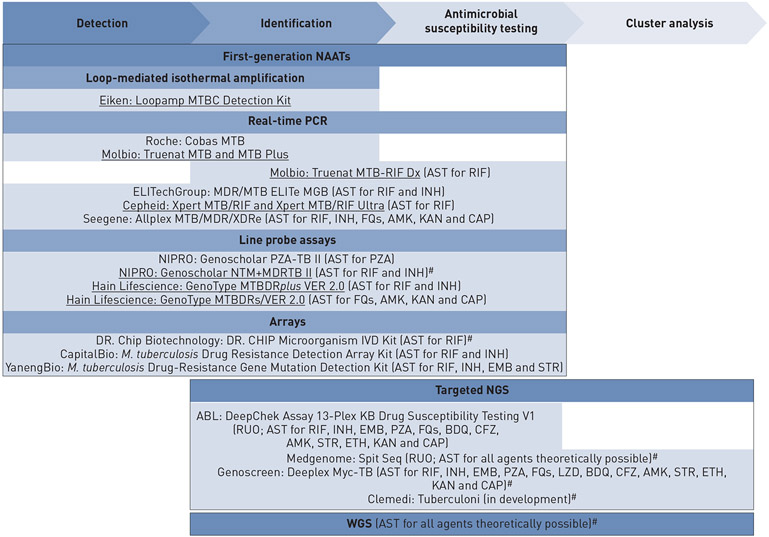

A comprehensive overview of the changing diagnostic landscape for mycobacteria is beyond the scope of this editorial [3]. Instead, we will focus on the impact of the adoption of nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs) [10]. Broadly speaking, these have been developed to accelerate turnaround times and, ideally, combine multiple diagnostic functions (figure 1). Yet, because the first-generation NAATs (e.g. line probe assays and real-time PCR) typically analyse fewer than 200 base pairs (bp), the number of diagnostic questions that can be addressed with a single assay is limited. In fact, these assays are not suitable for genotypic AST for delamanid and pretomanid as resistance to these nitroimidazoles can arise by mutations in six genes that span approximately 7500 bp, including promoters [11, 12].

FIGURE 1.

Functionality of selected first-generation nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs) for Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex (MTBC) diagnostics compared with targeted next-generation sequencing (NGS) and whole genome sequencing (WGS). All currently World Health Organization-endorsed NAATs are listed and underlined [10]. Additional assays are included but many more exist. Unless otherwise marked (#), the assays are only capable of identifying MTBC rather than differentiating nontuberculous mycobacteria. Cluster analysis is not currently a feature of Spit Seq but could be integrated and the resolution of Deeplex is considerably lower than WGS in this context. AMK: amikacin; AST: antimicrobial susceptibility testing; BDQ: bedaquiline; CAP: capreomycin; CFZ: clofazimine; EMB: ethambutol; ETH: ethionamide; FQs: fluoroquinolones; INH: isoniazid; KAN: kanamycin; LZD: linezolid; PZA: pyrazinamide; RIF: rifampicin; RUO: research use only; STR: streptomycin.

These constraints notwithstanding, over 45 first-generation NAATs are currently approved for clinical use to simultaneously identify MTBC and perform genotypic AST directly from the clinical sample (S. Mohamed and co-workers, poster presented at the 50th Union World Conference on Lung Health; available on request). This has revolutionised TB treatment by overcoming the lack of sensitivity and specificity of AFB smear microscopy. Moreover, the turnaround time of AST was reduced from weeks to days and even hours compared with phenotypic AST, which is hampered by the slow growth rate of MTBC and the fact that it is typically carried out sequentially (i.e. second-line drugs are only tested when resistance to first-line drugs is found) [5, 10]. It should be noted, however, that some compromises were made during the design of these NAATs, which is best illustrated with the Nipro Genoscholar PZA-TB II. To maximise the sensitivity of this assay for pyrazinamide resistance, almost 600 bp had to be covered, which could only be achieved by relying on a series of probes designed to bind to the wild-type sequence [13, 14]. This means that at least some resistance is inferred indirectly by most NAATs and that a locally frequent clone with a neutral mutation that does not confer resistance can result in a poor positive predictive value with significant treatment implications [15-17].

Another consequence of the goal to maximise the sensitivity of genotypic AST was that only a small number of assays simultaneously identify the most frequent NTM (e.g. the Nipro Genoscholar NTM +MDRTB II [10]). Hence, NTM are typically not differentiated in many settings with limited laboratory capacity, even when they are cultured (i.e. they are simply inferred by a negative MTBC-specific NAAT or antigen result [18]). In settings with a sufficient diagnostic capacity and higher relative prevalence of NTM, separate NAATs are employed to differentiate common NTM, although less frequent species are not identified or even misidentified because these assays interrogate only a small proportion of the genome [19]. This factor also restricts the resolution of traditional cluster methods, such as spoligotyping [5].

Next-generation sequencing to the rescue?

Theoretically, the most flexible solution to mycobacterial diagnostics would be whole genome sequencing (WGS) directly from the clinical sample. Yet, despite recent advances in next-generation sequencing (NGS) and sample preparation, this remains unreliable and prohibitively expensive for routine use in the short term [20]. Even if direct NGS were cost-effective for samples with mycobacteria, it would unlikely be suitable for detection in the foreseeable future, particularly in settings with low rates of positivity [5]. Instead, Public Health England has adopted routine WGS for all new positive mycobacterial cultures to combine species identification with genotypic AST for all TB drugs and cluster analysis at the ultimate resolution (figure 1). While this approach has accelerated the turnaround time for genotypic AST and reduced the need for phenotypic AST for first-line drugs given the excellent negative predictive value of WGS, it has come at the expense of longer turnaround times for NTM speciation [21]. New York state has avoided this problem by only adopting routine WGS for positive MTBC cultures and relying on faster, less expensive technologies for NTM (i.e. matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionisation-time of flight (MALDI-TOF) identifies approximately 70% of NTM and Sanger sequencing is used for the rest [3, 22]).

In this issue of the European Respiratory Journal, Jouet et al. [23] describe the performance of the Genoscreen Deeplex Myc-TB (Deeplex), the first representative of a new generation of NAATs to be approved for clinical use in the European Union by meeting CE-IVD requirements. This targeted NGS assay interrogates over 13000 bp (i.e. two orders of magnitude more than most first-generation NAATs). As a result, it enables NTM identification using hsp65 and interrogates 19 resistance genes for genotypic AST of 13 first- and second-line anti-TB drugs/classes, including most key drugs for the treatment of multidrug-resistant TB (i.e. bedaquiline, clofazimine, levofloxacin/moxifloxacin and linezolid). Its limit of detection for heteroresistance is as low as 3%, which is important for some drugs [24]. In addition, Deeplex combines phylogenetically informative mutations in these resistance genes with spoligotyping to provide a simultaneous cluster result. It is suitable for AFB-positive samples but must be performed at the reference laboratory level, as it relies on Illumina sequencing following the initial 24-plex PCR. Computational infrastructure for the bioinformatic analysis is not required, provided that a suitable internet connection is available to upload the sequencing data to the Deeplex web application [23].

Despite the considerable functionality of Deeplex, its niche in different settings is highly dependent on the local epidemiology (e.g. rate of positivity of samples, ratio of NTM versus MTBC, and prevalence of drug resistance) as well as wider diagnostic priorities and laboratory referral pathways given the likely need for batching to reduce the cost of sequencing. It is an attractive technology for national drug-resistance surveillance projects run by the World Health Organization (WHO) [25]. For routine diagnostics, Deeplex is most suitable as a follow-up test for patients with AFB-smear positive, likely drug-resistant TB to rapidly rule-in resistance due to mechanisms missed by the initial NAAT, either because those drug resistance targets are not interrogated at all or they were below the limit of detection for heteroresistance. It should be noted, however, that the sensitivity for genotypic AST of bedaquiline in particular is currently limited because atpE is not included and because of the large spectrum of possible resistance mutation in Rv0678, which precludes an interpretation of most mutations in the latter gene [26]. A secondary feature of Deeplex is that it provides additional information about resistance that is only inferred by first-generation NAATs. For example, systematic false resistance results due to neutral mutations can be identified and low-level resistance mutations for moxifloxacin can be distinguished from high-level mutations, which is not always possible using the Hain Lifescience GenoType MTBDRsl VER 2.0 [15]. Moreover, Deeplex identifies samples containing both MTBC and NTM, which can potentially result in false resistance results by phenotypic AST for MTBC. Finally, the cluster analysis results would enable high-incidence settings to supplement other epidemiological information to monitor the spread of major clones, which could prove valuable in some scenarios (e.g. in regions where Beijing strains are not dominant for which the resolution of Deeplex is reduced to phylogenetically informative mutations [16, 27]).

Additional targeted NGS assays are in development or available for research use only (figure 1). The ABL DeepChek Assay 13-Plex KB Drug Susceptibility Testing V1 enables genotypic AST for the same drugs as Deeplex, except for linezolid, which will be added as part of the next version. DeepChek covers over 10 000 bp, which includes a slightly different set of genes for the 11 drugs that it shares with Deeplex (i.e. lacks ahpC, gidB and ethA). NTM species identification is not possible and cluster analysis is restricted to the information in the resistance genes, although this is not currently a feature of the software. ABL is also developing another targeted NGS assay based on TGen technology [28]. By contrast, the Clemedi Tuberculoni assay aims to interrogate a panel of 100 genes to expand the number of anti-TB agents covered, in addition to differentiating NTM and providing an improved resolution for cluster analysis. It remains to be seen how reliable the amplification of such a large number of targets is and whether the cost of sequencing the approximately 200000 bp can be minimised sufficiently (i.e. this represents 4.5% of the genome compared with approximately 0.3% for Deeplex). Similar questions remain for the Medgenome Spit Seq assay that enriches the entire M. tuberculosis genome using molecular baits [29]. Notably, several of these assays are currently being evaluated by the Foundation for Innovative New Diagnostics as part of the Unitaid-funded Seq&Treat project to inform their potential endorsement by WHO.

Conclusion

Like a multifunctional Swiss army knife, Deeplex offers unprecedented versatility directly from the clinical sample and represents a welcome addition to the diagnostic and epidemiological toolbox. Yet, it is not a near-patient technology, is labour intensive and potentially expensive. To date, no one-size-fits all approach is available and routine diagnostics are still dependent on multiple assays for the tasks at hand. Nevertheless, the niche of targeted NGS will almost certainly expand pending the introduction of less expensive, faster, random-access sequencers [30].

Acknowledgements:

We thank Vincent Escuyer and Vladyslav Nikolayevskyy for clarifying the diagnostic algorithms in New York and England, respectively. Sebastian Dümcke, Sofiane Mohamed, Vedam Ramprasad, Camilla Rodrigues and Anita Suresh provided details regarding the various targeted NGS assays.

Support statement:

S. Mohamed was supported by NIH T32AI007046.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: S. Mohamed has nothing to disclose. C.U. Köser reports personal fees for consultancy from World Health Organization, TB Alliance, Becton Dickinson, QuantuMDx and Foundation for Innovative New Diagnostics (including work for Cepheid Inc. and Hain Lifescience), other (travel and accommodation support to attend meetings) from Hain Lifescience, other (collaboration) from YD Diagnostics, outside the submitted work; is an unpaid advisor to GenoScreen. M. Salfinger has nothing to disclose. W. Sougakoff has nothing to disclose. S.K. Heysell has nothing to disclose.

References

- 1.Leibniz Institute DSMZ-German Collection of Microorganisms and Cell Cultures GmbH. List of Prokaryotic Names with Standing in Nomenclature. Genus Mycobacterium. https://lpsn.dsmz.de/genus/mycobacterium Date last accessed: 29 Oct 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Daley CL, Iaccarino JM, Lange C, et al. Treatment of nontuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary disease: an official ATS/ERS/ESCMID/IDSA clinical practice guideline. Eur Respir J 2020; 56: 2000535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Banaei N, Musser KA, Salfinger M, et al. Novel assays/applications for patients suspected of mycobacterial diseases. Clin Lab Med 2020; 40: 535–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adjemian J, Daniel-Wayman S, Ricotta E, et al. Epidemiology of nontuberculous mycobacteriosis. Semin Respir Crit Care Med 2018; 39: 325–335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Köser CU, Ellington MJ, Cartwright EJ, et al. Routine use of microbial whole genome sequencing in diagnostic and public health microbiology. PLoS Pathog 2012; 8: e1002824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dean AS, Zignol M, Cabibbe AM, et al. Prevalence and genetic profiles of isoniazid resistance in tuberculosis patients: a multicountry analysis of cross-sectional data. PLoS Med 2020; 17: e1003008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Walker TM, Monk P, Smith EG, et al. Contact investigations for outbreaks of Mycobacterium tuberculosis: advances through whole genome sequencing. Clin Microbiol Infect 2013; 19: 796–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sax H, Bloemberg G, Hasse B, et al. Prolonged outbreak of Mycobacterium chimaera infection after open-chest heart surgery. Clin Infect Dis 2015; 61: 67–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bryant JM, Grogono DM, Rodriguez-Rincon D, et al. Emergence and spread of a human-transmissible multidrug-resistant nontuberculous mycobacterium. Science 2016; 354: 751–757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.MacLean E, Kohli M, Weber SF, et al. Advances in molecular diagnosis of tuberculosis. J Clin Microbiol 2020; 58: e01582–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shell SS, Wang J, Lapierre P, et al. Leaderless transcripts and small proteins are common features of the mycobacterial translational landscape. PLoS Genet 2015; 11: e1005641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rifat D, Li SY, Ioerger T, et al. Mutations in fbiD (Rv2983) as a novel determinant of resistance to pretomanid and delamanid in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2020; 65: e01948–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Willby MJ, Wijkander M, Havumaki J, et al. Detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis pncA mutations by the Nipro Genoscholar PZA-TB II assay compared to conventional sequencing. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2018; 62:e01871–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Köser CU, Cirillo DM, Miotto P. How to optimally combine genotypic and phenotypic drug susceptibility testing methods for pyrazinamide. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2020; 64: e01003–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ajileye A, Alvarez N, Merker M, et al. Some synonymous and nonsynonymous gyrA mutations in Mycobacterium tuberculosis lead to systematic false-positive fluoroquinolone resistance results with the Hain GenoType MTBDRsl assays. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2017; 61: e02169–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brandao AP, Pinhata JMW, Simonsen V, et al. Transmission of Mycobacterium tuberculosis presenting unusually high discordance between genotypic and phenotypic resistance to rifampicin in an endemic tuberculosis setting. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 2020; 125: 102004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Omar SV, Hillemann D, Pandey S, et al. Systematic rifampicin resistance errors with Xpert® MTB/RIF Ultra: implications for regulation of genotypic assays. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2020; 24: 1307–1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yin X, Zheng L, Lin L, et al. Commercial MPT64-based tests for rapid identification of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex: a meta-analysis. J Infect 2013; 67: 369–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tortoli E, Pecorari M, Fabio G, et al. Commercial DNA probes for mycobacteria incorrectly identify a number of less frequently encountered species. J Clin Microbiol 2010; 48: 307–310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.George S, Xu Y, Rodger G, et al. DNA thermo-protection facilitates whole genome sequencing of mycobacteria direct from clinical samples. J Clin Microbiol 2020; 58: e00670–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Olaru ID, Patel H, Kranzer K, et al. Turnaround time of whole genome sequencing for mycobacterial identification and drug susceptibility testing in routine practice. Clin Microbiol Infect 2018; 24: 659.e655–659.e657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shea J, Halse TA, Lapierre P, et al. Comprehensive whole-genome sequencing and reporting of drug resistance profiles on clinical cases of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in New York state. J Clin Microbiol 2017; 55: 1871–1882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jouet A, Gaudin C, Badalato N, et al. Deep amplicon sequencing for culture-free prediction of susceptibility or resistance to 13 anti-tuberculous drugs. Eur Respir J 2021; 57: 2002338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schön T, Miotto P, Köser CU, et al. Mycobacterium tuberculosis drug-resistance testing: challenges, recent developments and perspectives. Clin Microbiol Infect 2017; 23: 154–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tagliani E, Hassan MO, Waberi Y, et al. Culture and next-generation sequencing-based drug susceptibility testing unveil high levels of drug-resistant-TB in Djibouti: results from the first national survey. Sci Rep 2017; 7: 17672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kadura S, King N, Nakhoul M, et al. Systematic review of mutations associated with resistance to the new and repurposed Mycobacterium tuberculosis drugs bedaquiline, clofazimine, linezolid, delamanid and pretomanid. J Antimicrob Chemother 2020; 75: 2031–2043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sanchez-Padilla E, Merker M, Beckert P, et al. Detection of drug-resistant tuberculosis by Xpert MTB/RIF in Swaziland. N Engl J Med 2015; 372: 1181–1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Colman RE, Schupp JM, Hicks ND, et al. Detection of low-level mixed-population drug resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis using high fidelity amplicon sequencing. PLoS One 2015; 10: e0126626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Soundararajan L, Kambli P, Priyadarshini S, et al. Whole genome enrichment approach for rapid detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and drug resistance-associated mutations from direct sputum sequencing. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 2020; 121: 101915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cabibbe AM, Spitaleri A, Battaglia S, et al. Application of targeted next-generation sequencing assay on a portable sequencing platform for culture-free detection of drug-resistant tuberculosis from clinical samples. J Clin Microbiol 2020; 58: e00632–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]