Abstract

Objective

We sought to determine the influence of venovenous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) on outcomes of mechanically ventilated patients with COVID-19 during the first 120 days after hospital discharge.

Methods

Five academic centers conducted a retrospective analysis of mechanically ventilated patients with COVID-19 admitted during March through May 2020. Survivors had access to a multidisciplinary postintensive care recovery clinic. Physical, psychological, and cognitive deficits were measured using validated instruments and compared based on ECMO status.

Results

Two hundred sixty two mechanically ventilated patients were compared with 46 patients cannulated for venovenous ECMO. Patients receiving ECMO were younger and traveled farther but there was no significant difference in gender, race, or body mass index. ECMO patients were mechanically ventilated for longer durations (median, 26 days [interquartile range, 19.5-41 days] vs 13 days [interquartile range, 7-20 days]) and were more likely to receive inhaled pulmonary vasodilators, neuromuscular blockade, investigational COVID-19 therapies, blood transfusions, and inotropes. Patients receiving ECMO experienced greater bleeding and clotting events (P < .01). However, survival at discharge was similar (69.6% vs 70.6%). Of the 217 survivors, 65.0% had documented follow-up within 120 days. Overall, 95.5% were residing at home, 25.7% had returned to work or usual activity, and 23.1% were still using supplemental oxygen; these rates did not differ significantly based on ECMO status. Rates of physical, psychological, and cognitive deficits were similar.

Conclusions

Our data suggest that COVID-19 survivors experience significant physical, psychological, and cognitive deficits following intensive care unit admission. Despite a more complex critical illness course, longer average duration of mechanical ventilation, and longer average length of stay, patients treated with venovenous ECMO had similar survival at discharge and outcomes within 120 days of discharge.

Key Words: coronavirus, ECMO, critical illness, long-term outcomes

Abbreviations and Acronyms: ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; ELSO, Extracorporeal Life Support Organization; ICU, intensive care unit; ORACLE, Outcomes and Recovery after COVID-19 leading to ECMO; PICS, postintensive care syndrome; PTSD, posttraumatic stress disorder; VV, venovenous

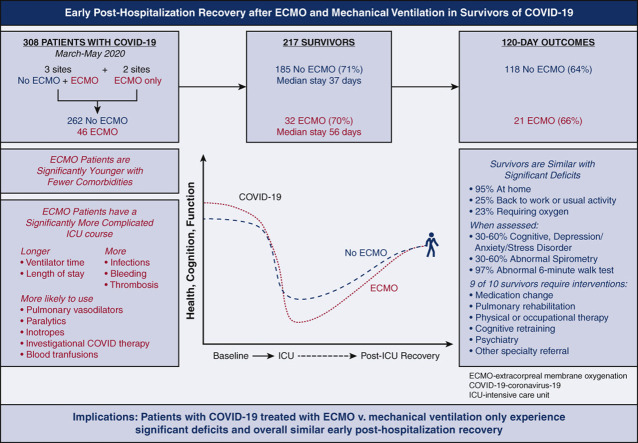

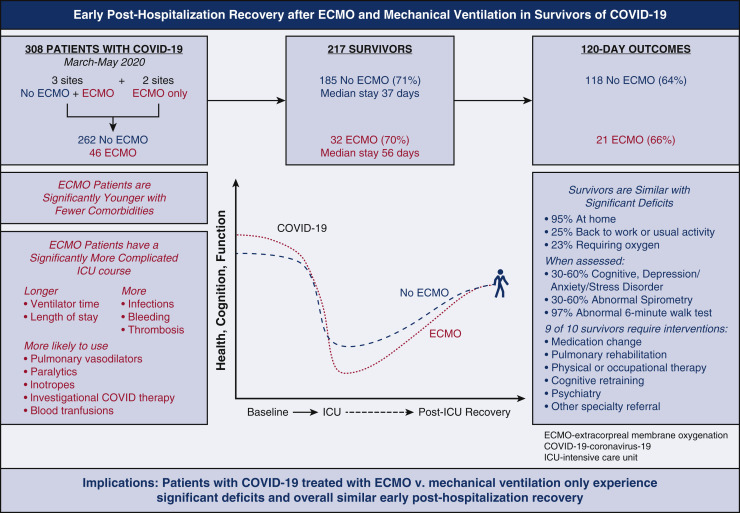

Graphical abstract

This retrospective multisite study examined posthospitalization outcomes for critically ill patients with COVID-19 with and without the support of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation.

Long-term outcomes of mechanically ventilated COVID-19 survivors is unknown.

Central Message.

COVID-19 survivors supported with ECMO had a more complex critical illness course but similar survival and posthospitalization cognitive, physical, and psychological deficits versus non-ECMO patients.

Perspective.

COVID-19 dramatically increased the number of critical illness survivors. The influence of ECMO on posthospitalization outcomes of patients with COVID-19–associated ARDS is unknown. In this retrospective multi-institutional study, COVID-19 patients supported with ECMO had similar survival at discharge and rates of cognitive, physical, and psychological deficits up to 120 days postdischarge.

See Commentary on page XXX.

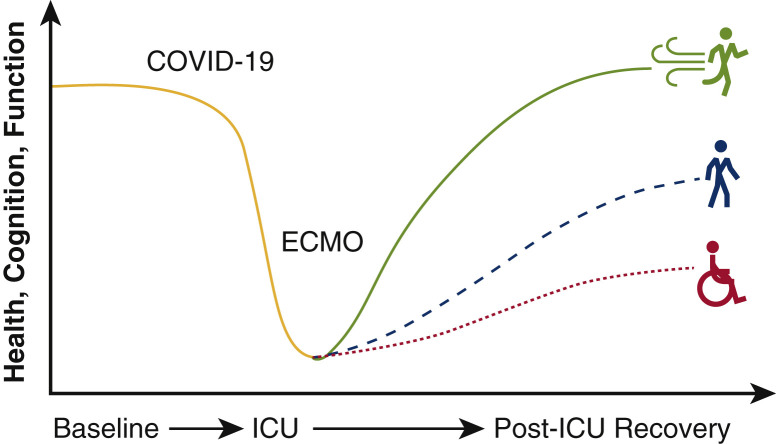

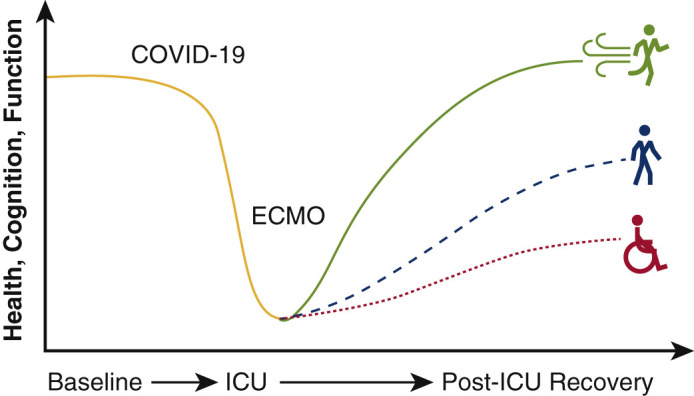

The role of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) for patients with COVID-19 continues to evolve with our knowledge of the virus and disease sequelae. The first reported results of deploying ECMO in patients with COVID-19 portended poor survival.1 However, subsequent data describing the international experience in 1000 patients with COVID-19 who were cannulated based on early conservative guidelines from the Extracorporeal Life Support Organization (ELSO) demonstrated an improved cumulative mortality rate of 37.4% at 90 days following cannulation.2 These updated findings suggested comparable short-term outcomes to prepandemic ELSO registry data that reported 40% in-hospital mortality associated with venovenous (VV) ECMO for patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS).3 Although many are investigating short-term results and indications for ECMO cannulation, little is known regarding the posthospitalization recovery trajectory for patients with COVID-19 who required ECMO support (Figure 1 ).

Figure 1.

Posthospitalization outcomes and the influence of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) on mechanically ventilated COVID-19 survivors is unknown. ICU, Intensive care unit.

Survivors of critical illness are at risk for ongoing morbidity that persists after hospital discharge. These long-term sequelae broadly captured under the term postintensive care syndrome (PICS) include mental, physical, and neurocognitive deficits that negatively influence quality of life and recovery.4 Indeed, a recent systematic review of more than 10,000 previously employed survivors of critical illness reported only 36% had returned to work 1 year later—whereas up to 84% experienced worsening employment status.5 Key features of PICS include impaired emotional well-being manifested as anxiety, depression, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) that can last for years.6 Patients may also develop physical dysfunction, including chronic pain and neuromuscular weakness7, 8, 9, 10, 11 in addition to cognitive deficits in memory, language, attention, and visual-spatial abilities.12 , 13

Whereas PICS in survivors of ARDS is well established,6 , 14, 15, 16 there are limited long-term data focused on survivors of VV-ECMO in general and survivors of COVID-19 specifically. Available recovery data for VV-ECMO survivors are largely limited to small, single-center investigations and provide conflicting reports regarding the influence of ECMO on posthospital outcomes.16, 17, 18, 19, 20 The majority of survivors of critical illness related to COVID-19 ARDS are at high risk for more than 1 impairment in cognitive, physical, or emotional health. Heightened infection control parameters limit hands-on care from providers, including physical and occupational therapists. Restricted visits with family and loved ones may promote feelings of isolation, emotional stress, and delirium. In addition, the downstream effect of in-hospital complications such as bleeding, clotting, stroke, and concomitant infections in critical illness survivors of COVID-19 are unknown. Protocolized follow-up as previously outlined by our group21 is a mechanism to define the needs and optimize the recovery of survivors of COVID-19–associated ARDS treated with ECMO.

The Outcomes and Recovery After COVID-19 Leading to ECMO (ORACLE) group is a multidisciplinary collaboration across 5 academic medical centers that aims to define the recovery and ongoing needs of survivors of COVID–19-associated ARDS requiring ECMO. The overarching goal of the ORACLE multidisciplinary collaborative is to determine the influence of ECMO on long-term outcomes of mechanically ventilated patients with COVID-19. In this initial report, we examined the recovery trajectory of mechanically ventilated survivors of COVID-19 during the first wave of the pandemic. We hypothesized that receipt of ECMO is associated with worse posthospitalization outcomes.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective analysis using data collected at 5 academic medical centers across the United States (University of Colorado, University of Kentucky, University of Virginia, Johns Hopkins University, and Vanderbilt University) representing the ORACLE multidisciplinary collaborative.21 Participating sites use ELSO guidelines when considering ECMO candidacy and employ specialized teams to manage patients receiving ECMO.22 Each participating site has a recovery clinic after intensive care unit (ICU) stay with a multidisciplinary team of providers, including intensivists, pharmacists, physical and occupational therapists, speech/language pathologists, psychologists, and physiatrists. These providers use validated instruments to assess functional, cognitive, and psychological deficits (Table E1). The study was approved by the institutional review board at each site and a waiver of informed consent was granted (University of Colorado and all other sites: COMIRB#20-0731, approved April 4, 2020).

Study investigators at each site performed a retrospective chart review of all adult patients with COVID-19 admitted to the ICU during the first wave of the pandemic from March through May 2020. Eligible patients were aged 18 years or older with documented COVID-19 infection. Patients who did not require intubation and mechanical ventilation were excluded. Data were available for all mechanically ventilated patients from 3 sites (University of Colorado, University of Kentucky, and University of Virginia), whereas data for patients cannulated for ECMO were collected at all 5 sites. Investigators collected patient demographic characteristics as well as clinical parameters from the index ICU stay, including ventilator days, receipt of vasoactive medications and investigational COVID-19 therapies, in-hospital complications, laboratory values collected at the time of intubation, length of stay, and discharge disposition. Additional data were collected for patients supported on ECMO, including mechanically ventilated days before cannulation, type of ECMO, and total hours on ECMO.

Posthospitalization outcomes data were obtained by chart review of documentation from the first clinical encounter during the 120 days following hospital discharge. Metrics for measuring postdischarge mental, physical, and cognitive dysfunction were guided by the Core ICU Outcome Measurement Set designed for patients recovered from acute respiratory failure using an International Modified Delphi Consensus Study.23 In clinic, patients underwent anxiety, depression, and PTSD screening using the following validated tools: General Anxiety Disorder-7 scale, Patient Health Questionnaire, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, and Impact of Event Scale 6 or R. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment or Montreal Cognitive Assessment Blind were used to measure cognitive impairment. Scores on alternative metrics of mental or cognitive dysfunction administered following discharge were recorded, when performed. Tests were administered per clinician discretion based on the individual needs of each patient at the time of clinic evaluation. Chart review was also used to record current type of residence; current oxygen use; employment status; and other diagnoses, including but not limited to critical illness neuromyopathy, acute stress disorder, PTSD, vocal cord dysfunction, and foot drop.

Data from all sites were combined for analysis. Patient demographic characteristics and in-hospital characteristics, including survival at discharge, were compared based on ECMO status using χ2 tests for categorical variables and t tests or Kruskal Wallis tests for continuous variables. For the subset of survivors who had available long-term outcomes data, the incidence of mental, physical, and cognitive dysfunction as well as place of residence and use of supplemental oxygen were assessed using χ2 tests based on ECMO status. The validated scales used to assess cognitive and mental impairment were dichotomized into normal versus abnormal results consistent with clinical practice. Due to the small sample sizes in this observational cohort, we have interpreted any P values > .05 as inconclusive rather than nonsignificant. Analyses were performed using R software (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

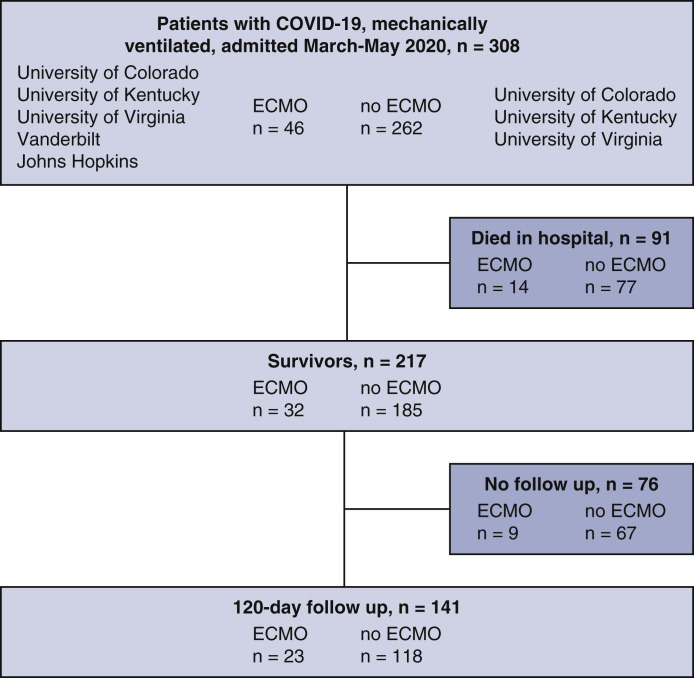

A total of 262 mechanically ventilated patients with COVID-19 were compared with 46 mechanically ventilated patients who were also cannulated for ECMO (Figure 2 ). Characteristics of all mechanically ventilated COVID-19 patients based on ECMO status are summarized in Table 1 . Patients supported with ECMO were younger (mean age, 48.5 vs 58.3 years; P < .001) and were transferred from greater distances to the hospital (mean distance, 24 vs 7 mi; P < .001). Those cannulated for ECMO were less likely to have underlying cardiovascular disease, renal disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or a history of smoking (P < .05 for all).

Figure 2.

Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) flow diagram depicting patients included in this retrospective analysis. ECMO, Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of mechanically ventilated patients with COVID-19 based on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) status

| Characteristic | All comers (n = 308) |

Survivors (n = 217) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ECMO (n = 46) | No ECMO (n = 262) | P value | ECMO (n = 32) | No ECMO (n = 185) | P value | |

| Age (y) | 48.5 ± 11.3 | 58.3 ± 15.2 | <.001 | 47.8 ± 12.0 | 55.5 ± 14.5 | .005 |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Female sex | 16 (34.8) | 99 (37.8) | .82 | 12 (37.5) | 75 (40.5) | .90 |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Race | .60 | .58 | ||||

| Asian | 2 (4.3) | 20 (7.6) | 2 (6.2) | 12 (6.5) | ||

| Black | 10 (21.7) | 63 (24.0) | 5 (15.6) | 50 (27.0) | ||

| Other | 14 (30.4) | 90 (34.4) | 12 (37.5) | 60 (32.4) | ||

| White | 20 (43.5) | 89 (34.0) | 13 (40.6) | 63 (34.1) | ||

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Body mass index | 33.7 ± 7.8 | 32.5 ± 9.8 | .44 | 33.8 ± 8.5 | 33.2 ± 8.9 | .72 |

| Missing | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | ||

| Insured | 30 (65.2) | 212 (81.5) | .021 | 21 (65.6) | 146 (79.8) | .12 |

| Missing | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | ||

| Distance traveled (mi) | 24.0 (9.2-50.8) | 7.0 (3.0-39.0) | <.001 | 23.5 (8.8-50.2) | 7.0 (3.2-45.0) | .019 |

| Missing | 0 | 4 | 0 | 3 | ||

| Diabetes | 16 (34.8) | 121 (46.9) | .17 | 11 (34.4) | 81 (44.0) | .41 |

| Missing | 0 | 4 | 0 | 1 | ||

| Cardiovascular disease | 3 (6.5) | 53 (20.5) | .04 | 0 | 35 (18.9) | .015 |

| Missing | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Hypertension | 22 (47.8) | 146 (56.8) | .33 | 12 (37.5) | 103 (56) | .082 |

| Missing | 0 | 5 | 0 | 1 | ||

| Chronic kidney disease | 1 (2.2) | 39 (15.2) | .031 | 1 (3.1) | 24 (13.0) | .19 |

| Missing | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Liver disease | 1 (2.2) | 6 (2.3) | 1.00 | 1 (3.1) | 2 (1.1) | .93 |

| Missing | 0 | 6 | 0 | 1 | ||

| Obstructive sleep apnea | 5 (10.9) | 46 (18.6) | .29 | 3 (9.4) | 33 (19.0) | .30 |

| Missing | 0 | 15 | 0 | 11 | ||

| Interstitial lung disease | 0 | 2 (0.8) | 1.00 | 0 | 0 | 1.00 |

| Missing | 0 | 5 | 0 | 1 | ||

| COPD | 0 | 27 (10.5) | .043 | 0 | 16 (8.7) | .17 |

| Missing | 0 | 5 | 0 | |||

| History of smoking | 3 (7.3) | 77 (33.5) | .001 | 2 (6.5) | 49 (29.0) | .015 |

| Missing | 5 | 32 | 1 | 16 | ||

Values are presented as mean ± SD, n (%), median (interquartile range), or n. COPD, Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

During the hospitalization, ECMO patients were mechanically ventilated for longer durations (median, 26 days; interquartile range [IQR], 19.5-41 vs 13 days; IQR, 7-20 days; P < .001). Median ventilator days before cannulation were 5.7 ± 3 days and patients spent a median of 299 hours on ECMO (IQR, 197.5-475.5 hours). Pao 2 on admission to the ICU was significantly lower in ECMO patients (73 vs 88 mm Hg; P = .002). All patients receiving ECMO were cannulated for VV-ECMO. Patients receiving ECMO were more likely to receive inhaled pulmonary vasodilators (69.6% vs 19.5%; P < .001), neuromuscular blockade (93.5% vs 46.4%; P < .001), investigational COVID-19 therapies (89.1% vs 64.6%; P = .002), blood transfusions (80.4% vs 31.2%; P < .001), and inotropes (32.6% vs 11.9%; P < .001). Patients receiving ECMO experienced higher rates of coinfection (84.8% vs 58.1%; P = .001), including bacteremia and pneumonia as well as greater bleeding (52.2% vs 15.8%; P < .001) and clotting (58.7% vs 22.9%; P < .001) complications. Receipt of ECMO was associated with a longer length of stay (median, 36 days [IQR, 26-53 days] vs median, 25 days [IQR, 16-35 days]; P < .001). Despite discrepancies in in-hospital complications, there was no difference in the percentage of patients who survived to discharge (32 out of 46 receiving ECMO [69.6%] vs 185 out of 262 without ECMO [70.6%]). Nearly half (13 out of 32 [41.9%]) of ECMO survivors were discharged home. Characteristics of the hospital stay for mechanically ventilated patients with COVID-19 are described in Table 2 .

Table 2.

Hospitalization characteristics of mechanically ventilated patients with COVID-19 based on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) status

| Characteristic | All comers (n = 308) |

Survivors (n = 217) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ECMO (n = 46) | No ECMO (n = 262) | P value | ECMO (n = 32) | No ECMO (n = 185) | P value | |

| Days intubated | 26 (19.5-41.0) | 13 (7-20) | <.001 | 28 (18-44) | 13 (7-20) | <.001 |

| Missing | 3 | 8 | 3 | 5 | ||

| Days intubated pre-ECMO | 5.7 ± 3.0 | – | 5.5 ± 3.1 | – | ||

| Missing | 0 | 0 | ||||

| ECMO hours | 299.0 (197.5-475.5) | – | 266.5 (192.0-390.0) | – | ||

| Inotropes | 15 (32.6) | 31 (11.9) | <.001 | 5 (15.6) | 9 (4.9) | .061 |

| Missing | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | ||

| Vasopressors | 45 (97.8) | 231 (88.2) | .086 | 31 (96.9) | 157 (84.9) | .12 |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Inhaled pulmonary vasodilators | 32 (69.6) | 51 (19.5) | <.001 | 24 (75.0) | 20 (10.8) | <.001 |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Neuromuscular blockade | 43 (93.5) | 121 (46.4) | <.001 | 30 (93.8) | 67 (36.4) | <.001 |

| Missing | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | ||

| Investigational COVID-19 therapy | 41 (89.1) | 168 (64.6) | .002 | 29 (90.6) | 128 (69.9) | .027 |

| Missing | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | ||

| Blood transfusion | 37 (80.4) | 81 (31.2) | <.001 | 25 (78.1%) | 46 (25.1) | <.001 |

| Missing | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | ||

| Bleeding complication | 24 (52.2) | 41 (15.8) | <.001 | 13 (40.6) | 26 (14.2) | <.001 |

| Missing | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | ||

| Clotting complication | 27 (58.7) | 60 (22.9) | <.001 | 21 (65.6) | 43 (23.2) | <.001 |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Infectious complication | 39 (84.8) | 151 (58.1) | .001 | 26 (81.2) | 108 (59.0) | .028 |

| Missing | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | ||

| Acute kidney injury | 32 (69.6) | 165 (63.0) | .49 | 23 (71.9) | 101 (54.6) | .10 |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Stroke | 5 (10.9) | 17 (6.5) | .46 | 1 (3.1) | 9 (4.9) | 1.00 |

| Missing | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | ||

| Delirium | 33 (71.7) | 159 (61.2) | .23 | 28 (87.5) | 131 (71.6) | .094 |

| Missing | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | ||

| ICU admit Pao2 | 73 (61-102) | 88 (71-123) | .002 | 76 (64-102) | 92 (73-123) | .020 |

| Missing | 1 | 5 | 1 | 3 | ||

| Length of stay (d) | 36 (26-53) | 25 (16-35) | <.001 | 37 (31-56) | 26 (18-35) | <.001 |

| Missing | 9 | 58 | 1 | 2 | ||

| Received inpatient therapy | 35 (76.1) | 130 (50.0) | .002 | 32 (100.0) | 126 (68.9) | <.001 |

| Missing | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | ||

| Alive at discharge | 32 (69.6) | 185 (70.6) | 1.00 | – | – | |

| Discharged location | ||||||

| Home | 13 (41.9) | 93 (52.2) | .39 | 13 (41.9) | 93 (52.5) | .34 |

| Acute rehab | 14 (45.2) | 51 (28.7) | .11 | 14 (45.2) | 50 (28.2) | .10 |

| SNF | 1 (3.2) | 13 (7.3) | .65 | 1 (3.2) | 13 (7.3) | .72 |

| LTAC | 3 (9.7) | 14 (7.9) | 1.00 | 3 (9.7) | 14 (7.9) | .95 |

| Missing | 1 | 14 | 1 | 8 | ||

Values are presented as mean ± SD, n (%), median (interquartile range), or n. ICU, Intensive care unit; SNF, skilled nursing facility; LTAC, long-term acute care facility.

Similar demographic trends were observed in a sensitivity analysis restricted to survivors (Table 2). Again, ECMO survivors were younger (mean age, 47.8 vs 55.5 years: P = .005), and traveled farther (median, 23.5 vs 7 mi; P = .019). ECMO survivors also experienced a more complex hospital course with increased use of adjunctive therapies and higher rate of complications. Number of days requiring mechanical ventilation (median, 28 days [IQR, 18-44 days] vs 13 days [IQR, 7-20 days]) and length of stay (median, 37 days [IQR, 31-56 days] vs 26 days [IQR, 18-35 days]) were significantly longer in ECMO survivors (P < .001 for both).

Of the 217 survivors, 141 (65.0%) had documented clinic follow-up within 120 days of discharge (Table 3 ). At the time of follow up, 95.5% were residing at home, 25.7% had returned to work or usual activity, and 23.1% were still using supplemental oxygen. Cognitive assessment was performed in 60 survivors. The burden of cognitive dysfunction was high; 87.5% of the ECMO cohort had an abnormal cognitive test compared with 59.6% in the ventilated-only cohort. In patients who were screened for depression, anxiety, or PTSD, 33.3% screened positive. One in 3 patients with follow-up had spirometry completed with abnormal forced expiratory volume, total lung capacity, or diffusing capacity reported in 44.9%, 53.5%, and 36.4% of those tested, respectively. The overall rate of reported ICU-acquired weakness or critical illness neuromyopathy was 44.7%. Of the 60 survivors with follow-up who were tested, 96.7% had an abnormal 6-minute walk distance. High rates of patients in both groups (87.5% ECMO vs 95.7% non-ECMO) had at least 1 recommended intervention consisting of a medication adjustment, pulmonary rehabilitation, physical or occupational therapy, cognitive retraining, psychiatry, or other specialty referral.

Table 3.

One hundred twenty-day follow-up outcomes of mechanically ventilated COVID-19 survivors based on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) status (N = 140)

| Outcome | ECMO (n = 23) | No ECMO (n = 118) | Total | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Living at home | .81 | |||

| Yes | 15 (100) | 91 (94.8) | 106 (95.5) | |

| No | 0 | 5 (5.2) | 5 (4.5) | |

| Test not performed | 8 | 22 | 30 | |

| Back to work or usual activity | .82 | |||

| Yes | 3 (20.0) | 25 (26.6) | 28 (25.7) | |

| No | 12 (80.0) | 69 (73.4) | 81 (74.3) | |

| Test not performed | 8 | 24 | 32 | |

| Requiring supplemental oxygen | .79 | |||

| Yes | 3 (17.6) | 24 (24.0) | 27 (23.1) | |

| No | 14 (82.4) | 76 (76.0) | 90 (76.9) | |

| Test not performed | 6 | 18 | 24 | |

| 6-min walk | 1.00 | |||

| Normal | 0 | 2 (3.7) | 2 (3.3) | |

| Abnormal | 6 (100.0) | 52 (96.3) | 58 (96.7) | |

| Test not performed | 17 | 64 | 81 | |

| Spirometry | ||||

| Normal forced expiratory volume | 2 (33.3) | 25 (58.1) | 27 (55.1) | .480 |

| Abnormal forced expiratory volume | 4 (66.7) | 18 (41.9) | 22 (44.9) | |

| Test not performed | 17 | 75 | 92 | |

| Normal total lung capacity | 3 (50.0) | 17 (45.9) | 20 (46.5) | 1.00 |

| Abnormal total lung capacity | 3 (50.0) | 20 (54.1) | 23 (53.5) | |

| Test not performed | 17 | 81 | 98 | |

| Normal diffusing capacity | 4 (66.7) | 24 (63.2) | 28 (63.6) | 1.00 |

| Abnormal diffusing capacity | 2 (33.3) | 14 (36.8) | 16 (36.4) | |

| Test not performed | 17 | 80 | 97 | |

| Cognitive dysfunction | .26 | |||

| Yes | 7 (87.5) | 31 (59.6) | 38 (63.3) | |

| No | 1 (12.5) | 21 (40.4) | 22 (36.7) | |

| Test not performed | 15 | 66 | 81 | |

| Depression/anxiety/PTSD | .13 | |||

| Yes | 1 (10.0) | 9 (45.0) | 10 (33.3) | |

| No | 9 (90.0) | 11 (55.0) | 20 (66.7) | |

| Test not performed | 13 | 98 | 111 | |

| Critical illness neuromyopathy | .42 | |||

| Yes | 8 (34.8) | 55 (46.6) | 63 (44.7) | |

| No | 15 (65.2) | 63 (53.4) | 78 (55.3) | |

| Test not performed | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Intervention recommended | .46 | |||

| Yes | 14 (87.5) | 89 (95.7) | 103 (94.5) | |

| No | 2 (12.5) | 4 (4.3) | 6 (5.5) | |

| Test not performed | 7 | 25 | 32 |

Values are presented as n (%) or n. PTSD, Posttraumatic stress disorder.

Discussion

In March 2020 as the COVID-19 pandemic was emerging in the United States, critical care teams across the country were faced with unprecedented challenges. Resource allocation was forced to pivot and focus on a sudden and overwhelming increase in critically ill patients filling ICUs. In deciding whether or not to offer VV-ECMO to patients failing mechanical ventilation, a number of concerns arose beyond questions of survival. In a resource-limited environment, how are we going to decide who to treat, when to treat, and when to stop? Intubated and paralyzed, patients were unable to advocate for themselves. Family members were prohibited to visit and over the telephone they asked if it was realistic to hope that their family member would regain meaningful quality of life. At the time, we could only confess that we did not know for sure. Striving to find answers to these questions was the impetus for forming ORACLE.

In this retrospective, observational study, survivors of COVID-19 who required mechanical ventilation experience significant deficits following ICU admission (Figure 3 ). Patients who failed mechanical ventilation and were also treated with VV-ECMO based on ELSO guidelines during the first wave of the pandemic had a more complex critical illness course, longer average duration of mechanical ventilation, and longer average length of stay, but similar survival at discharge and similar outcomes 120 days thereafter. Although these findings are encouraging, rates of PICS were high in all study patients; providers evaluating patient candidacy for ECMO should be informed of posthospitalization sequelae beyond mortality.

Figure 3.

This retrospective multisite study examines posthospitalization outcomes for critically ill patients with COVID-19 with and without the support of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO). Multi-institutional retrospective analysis suggests no significant difference in survivors 120 days after hospital discharge based on ECMO status. ICU, Intensive care unit.

It is important to review our findings in the context of 2 multicenter randomized, controlled trials, Conventional Ventilatory Support Versus Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation for Severe Adult Respiratory Failure (CESAR) and ECMO to Rescue Acute Lung Injury in Severe ARDS Study (EOLIA), which offer pre–COVID-19 mortality data for ECMO in patients with severe ARDS.24 , 25 The CESAR trial advocates for transfer to an ECMO center for adults with severe but potentially reversible respiratory failure based on improved 6-month survival without severe disability (63% vs 47%). However, enthusiasm for these results has been tempered by methodologic concerns, including lack of control group standardization. Subsequent investigation in the EOLIA trial failed to demonstrate a significant benefit in 60-day mortality for patients supported with ECMO compared with conventional mechanical ventilation but there was significant crossover of patients into the ECMO group. A recent meta-analysis combining data from these 2 trials demonstrated improved 90-day mortality associated with ECMO (36% vs 48%; P = .013). Furthermore, at 60 days postrandomization, ECMO was associated with increased number of days out of the ICU as well as days without vasopressor support, renal replacement therapy, or neurologic failure.26

This is the largest multicenter analysis to date comparing posthospitalization outcomes of patients with COVID-19 requiring mechanical ventilation and VV-ECMO support. Of survivors with documented follow-up at 4 months, 95.5% were living at home, but in this early posthospitalization period only one-quarter were back to work or usual activity and significant impairments associated with PICS were identified. More than half of patients who underwent cognitive assessment after mechanical ventilation and ECMO for COVID-19–associated ARDS reported cognitive dysfunction, with higher rates in the ECMO cohort. Depression, anxiety, or PTSD were less frequently screened for but present in one-third of those tested. ICU-acquired weakness was present in one-half of survivors and nearly all of the survivors who were assessed had an abnormal 6-minute walk distance. One-quarter of patients still required supplemental oxygen and nearly half of those tested had abnormal spirometry. These data help providers, patients, and families begin to understand the potential extended sequelae of this critical illness.

We recall during the first COVID-19 pandemic wave that several questioned the use of ECMO because of increased manpower, equipment, and hospital bed utilization. Based on these concerns, ELSO issued a consensus of conservative guidelines for use. All 5 centers in this study participate in ELSO and followed the early recommendations; as expected, the first wave of patients receiving ECMO were younger with few comorbidities. It is notable that despite a more complex in-hospital course, patients who were selectively treated with ECMO and survived did not show substantially worse outcomes at four months compared with survivors who did not receive ECMO. Our findings build upon work by Sylvestre and colleagues20 who interviewed 40 survivors of critical illness with ARDS up to 2 years following discharge. The authors report similarly high rates of cognitive dysfunction (55% vs 56%), moderate-to-severe depression symptoms (36% vs 39%), and moderate-to-severe anxiety symptoms (55% vs 44%) in patients who did and not receive ECMO, respectively.

This multidisciplinary multisite observational study proposes a mechanism to collect measures of PICS in ECMO survivors. Measuring the posthospitalization influence of COVID-19–associated critical care interventions such as ECMO has been identified as a research priority in the Surviving Sepsis Campaign COVID-19 Guidelines.27 Whereas prior research suggests measurable benefit of multidisciplinary post-ICU follow-up on mental outcomes,28 a minority of patients receive comprehensive postsepsis care and there is high variability regarding patient eligibility for clinic referral and follow-up patterns.29 , 30 Our study highlights the intrinsic value of a multidisciplinary post-ICU clinic tailored to address pulmonary rehabilitation and deficits associated with PICS. Although more than 90% of patients were residing at home at the time of clinic follow-up, rates of continued oxygen requirement, and cognitive and emotional dysfunction were high. Additional longer-term prospective data are needed to determine whether or not timely diagnosis and therapy to address these deficits can optimize the recovery of survivors and improve rates of return to work and normal activities.

Our study has several limitations. Although the cohort included patients from 5 institutions across the United States, this was a retrospective observational study with inherent limitations. Care of patients with COVID-19 and posthospitalization assessments were performed during a time when the health care system in this country was experiencing unprecedented stressors. We did not have sufficient sample size to explore site-level variation in outcomes. Patients supported with VV-ECMO had failed mechanical ventilation so were measurably sicker compared with their counterparts who were not cannulated and systematically different in that they were selected for ECMO based on ELSO criteria. In addition, approximately two-thirds of survivors participated in post-ICU follow-up, which inherently biases a group with health insurance, with the means for transportation and living within driving distance of a medical center. The prevalence of PICS deficits was high in both groups, which may have limited between-group comparisons and there is likely an ascertainment bias in terms of which patients received testing to evaluate for cognitive and mental impairment. Finally, at this time we do not have data regarding cost-effectiveness of ECMO for patients with COVID-19–associated ARDS, which represents an important consideration in determining the overall cost, risk, and/or benefit of ECMO.

Conclusions

Our study demonstrated significant physical, psychological, and cognitive deficits at 4 months following COVID-19–associated critical illness. However, ECMO support directed by early ELSO guidelines in specialized centers was not associated with worse survival or posthospitalization outcomes compared with other ICU survivors. As many are doing, these data may prompt ongoing adjustments of cannulation criteria. However, further investigation with a prospective trial is needed to better understand posthospitalization outcomes and mitigate the influence of PICS in survivors treated with ECMO. The ORACLE research collaborative is actively working on gathering data for a larger cohort with extended follow-up to 1-year postdischarge. Post-ICU recovery clinics offer a unique opportunity for ongoing assessment of critical illness survivors and may be harnessed to gather long-term data for a broader cohort of cardiothoracic surgical patients while simultaneously offering coordinated multidisciplinary evaluation and physical, psychological, and cognitive therapies to maximize the recovery of survivors of critical illness.

Webcast

You can watch a Webcast of this AATS meeting presentation by going to: https://aats.blob.core.windows.net/media/21%20AM/AM21_A17/AM21_A17_05a.mp4.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

The Journal policy requires editors and reviewers to disclose conflicts of interest and to decline handling or reviewing manuscripts for which they may have a conflict of interest. The editors and reviewers of this article have no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank David J. Carter, BS, College of Medicine, University of Kentucky. The ORACLE group includes Ashley A. Montgomery-Yates, MD (Division of Pulmonary, Critical Care and Sleep Medicine, College of Medicine, University of Kentucky), Ann M. Parker, MD, and Bo Soo Kim, MD (Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, Department of Medicine, Johns Hopkins University), Nicholas R. Teman, MD (Division of Cardiothoracic Surgery, Department of Surgery, University of Virginia), Jordan Hoffman, MD (Division of Cardiothoracic Surgery, Department of Surgery, Vanderbilt University), Karsten Bartels, MD, PhD (Department of Anesthesiology, University of Nebraska), Sung-Min Cho, DO, MHS (Department of Neurology and Critical Care, Johns Hopkins University), and Joseph A. Hippensteel, MD (Division of Pulmonary Sciences and Critical Care, Department of Medicine, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus).

Contributor Information

ORACLE group:

Ashley A. Montgomery-Yates, Ann M. Parker, Nicholas R. Teman, Jordan Hoffman, Karsten Bartels, Bo Soo Kim, Sung-Min Cho, and Joseph A. Hippensteel

Appendix E1

Table E1.

Validated instruments used to assess posthospitalization recovery outcomes by site

| Recovery outcome | Functional | General health | Cognitive | Dyspnea | Depression | PTSD | Anxiety |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Instrument | 6-min walk test (m) | EQ5D-5L | MoCA blind or MoCA | MRC Dyspnea Score or Borg Dyspnea Score | HADS, or PHQ-9, or PROMIS | PCL-5, or IES-R, or IES-6 | GAD-7, or PROMIS, or HADS |

| Site | All sites | Colorado Kentucky Hopkins Virginia |

All sites | All sites | All sites | All sites | All sites |

PTSD, Posttraumatic stress disorder; EQ5D, European Quality of Life Five Dimension; MoCA, Montreal Cognitive Assessment; MRC, Medical Research Council; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire 9; PROMIS, patient-reported outcomes measurement information system; PCL-5, Post-traumatic stress disorder checklist 5; IES-R, Impact of Event Scale Revised; IES-6, Impact of Event Scale 6; GAD-7, Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7.

References

- 1.Henry B.M., Lippi G. Poor survival with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS) due to coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): pooled analysis of early reports. J Crit Care. 2020;58:27–28. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2020.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barbaro R.P., MacLaren G., Boonstra P.S., Combes A., Agerstrand C., Annich G., et al. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support in COVID-19: an international cohort study of the Extracorporeal Life Support Organization registry. Lancet. 2020;396:1071–1078. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32008-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.ELSO registry report. 2021. https://www.elso.org/Registry/Statistics/InternationalSummary.aspx

- 4.Needham D.M., Davidson J., Cohen H., Hopkins R.O., Weinert C., Wunsh H., et al. Improving long-term outcomes after discharge from intensive care unit: report from a stakeholders' conference. Crit Care Med. 2012;40:502–509. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318232da75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kamdar B.B., Suri R., Suchyta M.R., Digrande K.F., Sherwood K.D., Colantuoni E., et al. Return to work after critical illness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Thorax. 2020;75:17–27. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2019-213803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hopkins R.O., Weaver L.K., Collingridge D., Parkinson R.B., Chan K.J., Orme J.F., Jr. Two-year cognitive, emotional, and quality-of-life outcomes in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171:340–347. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200406-763OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fan E., Cheek F., Chlan L., Gosselink R., Hart N., Herridge M.S., et al. An official American Thoracic Society clinical practice guideline: the diagnosis of intensive care unit-acquired weakness in adults. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;190:1437–1446. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201411-2011ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kress J.P., Hall J.B. ICU-acquired weakness and recovery from critical illness. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:287–288. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1406274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jolley S.E., Bunnell A.E., Hough C.L. ICU-acquired weakness. Chest. 2016;150:1129–1140. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2016.03.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Latronico N., Bolton C.F. Critical illness polyneuropathy and myopathy: a major cause of muscle weakness and paralysis. Lancet Neurol. 2011;10:931–941. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(11)70178-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ohtake P.J., Lee A.C., Scott J.C., Hinman R.S., Ali N.A., Hinkson C.R., et al. Physical impairments associated with post-intensive care syndrome: systematic review based on the World Health Organization's international classification of functioning, disability and health framework. Phys Ther. 2018;98:631–645. doi: 10.1093/ptj/pzy059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davidson J.E., Harvey M.A., Bemis-Dougherty A., Smith J.M., Hopkins R.O. Implementation of the pain, agitation, and delirium clinical practice guidelines and promoting patient mobility to prevent post-intensive care syndrome. Crit Care Med. 2013;41(9 suppl 1):S136–S145. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182a24105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wolters A.E., Slooter A.J., van der Kooi A.W., van Dijk D. Cognitive impairment after intensive care unit admission: a systematic review. Intensive Care Med. 2013;39:376–386. doi: 10.1007/s00134-012-2784-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Herridge M.S., Moss M., Hough C.L., Hopkins R.O., Ricke T.W., Bienvenu O.J., et al. Recovery and outcomes after the Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS) in patients and their family caregivers. Intensive Care Med. 2016;42:725–738. doi: 10.1007/s00134-016-4321-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Herridge M.S., Tansey C.M., Matté A., Tomlinson G., Diaz-Granados N., Cooper A., et al. Functional disability 5 years after acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1293–1304. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mikkelsen M.E., Shull W.H., Biester R.C., Taichman D.B., Lynch S., Demissie E., et al. Cognitive, mood and quality of life impairments in a select population of ARDS survivors. Respirology. 2009;14:76–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2008.01419.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roll M.A., Kuys S., Walsh J.R., Tronstad O., Ziegenfuss M.D., Mullany D.V. Long-term survival and health-related quality of life in adults after extra corporeal membrane oxygenation. Heart Lung Circ. 2019;28:1090–1098. doi: 10.1016/j.hlc.2018.06.1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stoll C., Haller M., Briegel J., et al. Health-related quality of life. Long-term survival in patients with ARDS following Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation (ECMO) Anaesthesist. 1998;47:24–29. doi: 10.1007/s001010050518. [Article in German] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harley O., Reynolds C., Nair P., Buscher H. Long-term survival, posttraumatic stress, and quality of life post extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. ASAIO J. 2020;66:909–914. doi: 10.1097/MAT.0000000000001095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sylvestre A., Adda M., Maltese F., Lannelongue A., Daviet F., Parzy G., et al. Long-term neurocognitive outcome is not worsened by of the use of venovenous ECMO in severe ARDS patients. Ann Intensive Care. 2019;9:82. doi: 10.1186/s13613-019-0556-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mayer K.P.J.S., Etchill E.W., Zwischenberger J.B., Rove J.Y. Long-term recovery of survivors of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) treated with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: the next imperative. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg Open. 2021;5:163–168. doi: 10.1016/j.xjon.2020.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Badulak J., Antonini M.V., Stead C.M., Shekerdemian L., Raman L., Paden M.L., et al. ECMO for COVID-19: updated 2021 guidelines from the Extracorporeal Life Support Organization (ELSO) ASAIO J. 2021;67:485–495. doi: 10.1097/MAT.0000000000001422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Needham D.M., Sepulveda K.A., Dinglas V.D., Chessare M., Friedman L.A., Bingham C.O., III, et al. Core outcome measures for clinical research in acute respiratory failure survivors. An International Modified Delphi Consensus Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;196:1122–1130. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201702-0372OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Combes A., Hajage D., Capellier G., Demoule A., Lavoué S., Guervukky C., et al. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for severe acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:1965–1975. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1800385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peek G.J., Mugford M., Tiruvoipati R., Wilson A., Allen E., Thalanany M.M., et al. Efficacy and economic assessment of conventional ventilatory support versus extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for severe adult respiratory failure (CESAR): a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2009;374:1351–1363. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61069-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Combes A., Peek G.J., Hajage D., Hardy P., Abrams D., Schmidt M., et al. ECMO for severe ARDS: systematic review and individual patient data meta-analysis. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46:2048–2057. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-06248-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Coopersmith C.M., Antonelli M., Bauer S.R., Deutschman C.S., Evans L.E., Ferrer R., et al. The Surviving Sepsis Campaign: research priorities for coronavirus disease 2019 in critical illness. Crit Care Med. 2021;49:598–622. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000004895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rosa R.G., Ferreira G.E., Viola T.W., Robinson C.C., Kochhann R., Berto P.P., et al. Effects of post-ICU follow-up on subject outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Crit Care. 2019;52:115–125. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2019.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Taylor S.P., Chou S.H., Sierra M.F., Shuman T.P., McWilliams A.D., Taylor B.T., et al. Association between adherence to recommended care and outcomes for adult survivors of sepsis. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2020;17:89–97. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201907-514OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rousseau A.F., Prescott H.C., Brett S.J., Weiss B., Azoulay E., Creteur J., et al. Long-term outcomes after critical illness: recent insights. Crit Care. 2021;25:108. doi: 10.1186/s13054-021-03535-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]