Abstract

COVID-19 is one of the worst global health crises in a century. Japan confirmed its first case of COVID-19 in mid-January and declared a state of emergency in April and May 2020, urging people to stay at home and reduce travel. Using Mobile Spatial Statistics (i.e., population statistics created from operational data of mobile terminal networks), we estimated daily intra- and inter-prefectural population mobility in the Tokyo Megalopolis Region, Japan in 2020. Then, we developed a compartmental model with population mobility to explore the role of stay-at-home requests and travel restrictions in preventing the spread of COVID-19. This model describes the COVID-19 pandemic through a susceptible-exposed-presymptomatic infectious-undocumented and documented infectious-removed (SEPIR) process and incorporates intra- and inter-prefectural population mobility into the transmission process. We found that people significantly reduced travel during the state of emergency, although stay-at-home requests and travel restrictions were recommended rather than mandatory. The reduction in population mobility, combined with other control measures, resulted in a substantial reduction in effective reproduction numbers to below 1, thus controlling the first wave of the pandemic. Moreover, the relationship between population mobility and COVID-19 transmission changed over time. The dampening of the second wave of the pandemic indicated that smaller reductions in population mobility could result in pandemic control, probably because of other social distancing behaviors. Our proposed model can be used to analyze the impact of different public health interventions, and our findings shed light on the effectiveness of soft containments in curbing the spread of COVID-19.

Keywords: COVID-19 pandemic, Human mobility, State of emergency, Stay-at-home requests, Travel restrictions, Mobile spatial statistics

1. Introduction

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has become a global pandemic and poses an unprecedented challenge to public health and the world of work (Anzai et al., 2020; Chang et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2021). By the end of September 2021, more than 233 million cases had been confirmed worldwide, with more than 4.77 million deaths attributed to COVID-19. Japan confirmed its first case of COVID-19 on January 15, 2020, and since then a large number of infections have been confirmed throughout the country. One approach to curbing the spread of COVID-19 is to reduce human travel through nonpharmaceutical interventions such as physical isolation, travel bans and restrictions, and stay-at-home orders (Chinazzi et al., 2020, Kraemer et al., 2020, Flaxman et al., 2020, Unwin et al., 2020, Xiong et al., 2020).

Many countries (e.g., the United States, France, and Italy) implemented mandatory lockdowns, limiting all nonessential travel (de Haas et al., 2020, Shibayama et al., 2021, Xiong et al., 2020). In contrast, the Japanese government declared a state of emergency in April and May 2020, urging people to stay at home and refrain from nonessential outings. As the Constitution of Japan does not allow the government to impose mandatory lockdowns on residents, the stay-at-home requests and travel restrictions are recommendations rather than mandatory enforcements (Hara and Yamaguchi, 2021, Watanabe and Yabu, 2020, Yabe et al., 2020). Looking at the Government Response Stringency Index (Hale et al., 2021), a measure to evaluate the strictness of lockdown policies that primarily restrict human behavior, the stringency index for Japan during the state of emergency in 2020 was 47.22, which was much smaller than those for Italy (93.52), France (87.96), the United Kingdom (79.63), Canada (75.93), and the United States (72.69). Such differences in control measures make Japan an interesting case for international comparative analysis (Yabe et al., 2020). Exploring the role of stay-at-home requests and travel restrictions in preventing the spread of COVID-19 in Japan will provide deeper insights into the effectiveness of soft containment measures.

Although existing studies have explored the impact of travel restrictions and stay-at-home orders in curbing the spread of COVID-19 in the United States, Europe, and China (Badr et al., 2020, Jia et al., 2020, Linka et al., 2020, Xiong et al., 2020), we have a limited understanding of the role of stay-at-home requests and travel restrictions in preventing the spread of COVID-19 in Japan. Moreover, statistical methods (e.g., simultaneous equations model) (Xiong et al., 2020) or classic multi-compartment models (e.g., susceptible-exposed-infectious-recovered (SEIR) model) (Qian and Ukkusuri, 2021) have often been used to evaluate the impact of human mobility on COVID-19 transmission. However, these methods do not take into account the unique features of COVID-19 (e.g., the asymptomatic infectiousness and time-varying ascertainment rates), which may lead to underestimation of the impact of reduced human travel. Additionally, there are a great number of inter-prefectural commuters in metropolitan areas of Japan, which contributes to the spatial spread of COVID-19. Therefore, a more advanced model is needed to better characterize the transmission dynamics of COVID-19 and incorporate inter-prefectural commuting flows into the transmission process.

The contributions of this study are twofold. From a methodological perspective, we developed a compartmental model to characterize the role of human mobility in the spread of COVID-19. This model not only considers important features of COVID-19 (including the infectiousness of presymptomatic and asymptomatic individuals) and the time-varying strength of public health interventions, but also incorporates inter-prefectural commuting flows and intra-prefectural population mobility into COVID-19 transmission. From an empirical perspective, we explored the role of stay-at-home requests and travel restrictions in preventing the spread of COVID-19 by applying the proposed methodology in the Tokyo Megalopolis Region, Japan. The findings shed light on the effectiveness of soft containment measures in curbing the spread of COVID-19.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. The next section reviews previous work on the relationship between human mobility and the spread of infectious diseases. The third section describes the study area and the data used. A detailed description of the methodology is presented in the fourth section. The fifth section applies the proposed model to analyze the role of stay-at-home requests and travel restrictions in preventing the spread of COVID-19. The conclusions are given in the final section.

2. Literature review

There is a two-way relationship between the spread of infectious diseases and travel behavior (Abdullah et al., 2021): the perceived risk of infectious diseases and lockdown policies affect travel behavior, while appropriate travel restrictions can mitigate the spread of infectious diseases. Many studies have analyzed the impact of COVID-19 pandemic on travel behavior (Beck and Hensher, 2020, Bohman et al., 2021, Kim and Kwan, 2021, Kopsidas et al., 2021, Wee and Witlox, 2021). People generally reduced outdoor travel because of lockdown policies and fear of getting infected (Hu et al., 2021). In Japan, there was also a significant reduction in outdoor trips, although countermeasures relied heavily on requests for voluntary self-restrictions (Arimura et al., 2020, Hara and Yamaguchi, 2021, Parady et al., 2020). However, the reduction in human travel has become smaller over time despite the existence of travel restrictions, as knowledge of COVID-19 has increased and perceived risk has decreased (Kim and Kwan, 2021, Lyu and Takikawa, 2021). Additionally, the COVID-19 pandemic has reduced the probability of taking public transport, and people are more likely to travel by active modes (e.g., walking and bicycling) and private vehicles (Abdullah et al., 2021, Kopsidas et al., 2021).

There are also many studies exploring the role of reduced human travel in curbing the spread of COVID-19. Given the way of transmission of COVID-19, social distancing (e.g., staying at home and refraining from nonessential travel) has been a key mitigation strategy. Mandatory lockdown has been proven to be effective in preventing the spread of COVID-19 in the United States, Europe, and China (Badr et al., 2020, Jia et al., 2020, Linka et al., 2020, Xiong et al., 2020). Unlike these countries, stay-at-home requests and travel restrictions during a state of emergency in Japan are recommended rather than mandatory. The dampening of the pandemic during a state of emergency indicates the effectiveness of soft containments (Kuniya, 2020), whereas it is unclear what role of stay-at-home requests and travel restrictions have played. Mobile terminal location data provide population estimates and mobility information (Hara and Yamaguchi, 2021, Terada et al., 2013), allowing us to track human mobility changes during the pandemic and explore the impact of mobility dynamics on COVID-19 transmission.

To characterize the transmission of COVID-19, compartmental models have been widely used because of their well-explored mathematical properties and scalability at the city level (Ding et al., 2021, Kondo, 2021, Qian and Ukkusuri, 2021). The most basic compartmental model is the susceptible-infectious-removed (SIR) model, which divides the population into susceptible, infectious, and removed compartments. Based on the SIR model, a variety of compartmental models have been developed to capture more realistic characteristics of infectious diseases, such as the models that consider the incubation period of contagion (Li and Muldowney, 1995), the time-varying transmission rates (Smirnova et al., 2019), and the asymptomatic infectious compartment (Hao et al., 2020). Nonlinear ordinary differential equations are often used to model the dynamics among the compartments. Furthermore, as human mobility positively contributes to the spread of many infectious diseases, some studies have developed compartmental models with mobility dynamics to analyze the role of human mobility in the transmission (Arino and van den Driessche, 2003, Linka et al., 2020, Pei et al., 2018, Qian and Ukkusuri, 2021, Li et al., 2020). However, these models often do not take into account the unique characteristics of COVID-19 (e.g., the asymptomatic infectiousness and time-varying ascertainment rates) and the existence of a great number of intercity commuters.

Considering the existing issues, we developed a more advanced model to characterize the transmission dynamics of COVID-19 in metropolitan areas of Japan and evaluated the role of stay-at-home requests and travel restrictions in preventing the spread of COVID-19. The findings can improve our understanding of the effectiveness of soft containments and provide additional insights into the development of countermeasures.

3. Study area and data

3.1. Study area

The Tokyo Megalopolis Region consists of Tokyo Metropolis and the three neighboring prefectures of Saitama, Chiba, and Kanagawa, and is home to around 30% of Japan’s total population. With an area of 13,376 km2 and a population of approximately 36.7 million, the Tokyo Megalopolis Region is the most populous metropolitan area in the world; it is also the largest metropolitan economic area in the world, with a total GDP of approximately $1.7 trillion (Japan Statistical Yearbook, 2021). Fig. 1 shows the location and population density (January 2020) of Tokyo Metropolis and three neighboring prefectures. Tokyo has a much higher population density than the three neighboring prefectures.

Fig. 1.

Location and population density of the study area.

After the first case of COVID-19 was confirmed in Kanagawa Prefecture on January 15, 2020, the virus resulted in numerous infection clusters across the country. The Tokyo Megalopolis Region was the worst hit area in Japan, with 106,926 confirmed cases by the end of 2020. The high population density and dense economic activity in the Tokyo Megalopolis Region increase the likelihood of close contact between people and hence raise the risk of infection. Moreover, public transport is the main mode of transport in this region, with the most extensive and heavily used urban rail network in the world. The heavy dependence on public transport and long commute time lead to travelers being in close proximity for a long duration and increase risk of infection (Qian and Ukkusuri, 2021).

To reduce the spread of COVID-19, the Japanese government announced countermeasures at the end of February (including school closures from March 2) and then declared a state of emergency for the Tokyo Megalopolis Region on April 7, 2020. During the state of emergency, the government requested restaurants to shorten their business hours, restricted public gatherings, promoted telework, and urged people to stay at home and refrain from nonessential outings. With the pandemic under control, the state of emergency was finally lifted in this region on May 25, 2020, and most of the schools that were temporarily closed had reopened by June 1, 2020. Afterwards, the Japanese government launched “Go To” campaign to promote domestic travel and boost local economy. The Go to Travel campaign started from July 27, 2020 and provided residents with subsidies of up to 50% on transportation, hotels, and tourist attractions within Japan. Residents of Tokyo and travel within the capital were initially not eligible for the discounts, but as of October 1, 2020, travelling to and from Tokyo was included in the campaign. Additionally, the Go to Eat campaign, which offered meal discount vouchers for specified restaurants, had launched since October 1, 2020. These campaigns were gradually suspended by December 28, 2020 because of the rising number of infections.

3.2. Data

NTT DOCOMO, Inc. is the largest telecommunications company in Japan. Approximately 40% of the total population uses NTT DOCOMO’s mobile phone services every day (Okajima et al., 2013). Mobile Spatial Statistics (MSS) are statistics of the actual population in areas throughout Japan that are estimated from operational data of the NTT DOCOMO mobile terminal network. In detail, MSS are created through a three-step process: (1) de-identification: removing identifying information (e.g., names and telephone numbers); (2) estimation: aggregating the number of mobile terminals present in each cell and estimating the total population by extrapolation using the adoption rates of NTT DOCOMO mobile terminals; and (3) disclosure limitation: removing the cells with very small populations in order to protect the privacy of users (Arimura et al., 2020, Terada et al., 2013). For the second step, the number of mobile terminals present in a cell per hour in 2020 is calculated as the average of the number of terminals in each 10-minute period. This estimation method considers how long travelers stay in a cell per hour. For example, if a mobile terminal stays in a cell for 30 min, it is considered to represent 0.5 people in that cell. By contrast, in 2019, a representative value of the number of 10-minute terminals is taken as the number of mobile terminals per hour. After the number of mobile terminals per hour is aggregated, the hourly population is extrapolated using the adoption rates of NTT DOCOMO mobile terminals, which vary by gender, five-year age group and city of residence. For more details on the estimation of MSS, please refer to Terada et al. (2013). Oyabu et al. (2013) compared the MSS with National Census Statistics and demonstrated the reliability of MSS. To date, MSS have been used in many transportation studies (Arimura et al., 2020, Hara and Yamaguchi, 2021, Kubo et al., 2020, Nakanishi et al., 2018, Yamaguchi and Nakayama, 2020).

We collected the MSS in 2019 and 2020, which reveal the hourly population by 500-meter grid throughout Japan. As the MSS also record the hourly population per 500-meter grid by prefecture of residence, we can estimate the inter-prefectural population flow. In addition, we collected data on the COVID-19 pandemic from the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare of Japan, including the number of infections, hospitalizations, and deaths per day per prefecture in Japan in 2020.

4. Methodology

4.1. Estimation of population mobility

To capture mobility trends during the COVID-19 pandemic, we estimated the approximate number of intra-prefectural trips and inter-prefectural flows using MSS. Based on the assumption of minimum movement (Hara and Yamaguchi, 2021), we estimated the number of daily intra-prefectural trips as follows:

| (1) |

where is the number of intra-prefectural trips in prefecture i on day t, and is the population of grid g at hour h () on day t. When , refers to the last hour of the previous day.

Moreover, using the MSS by prefecture of residence, we calculated daily inter-prefectural mobile population flows, as summarized in (2).

| (2) |

where is the number of inter-prefectural population flow from prefecture i to prefecture j on day t, and is the number of people who live in prefecture i while present in grid g of prefecture j within hour h.

To reveal changes in human mobility during the COVID-19 pandemic, we first estimated normal mobility before the pandemic. As the method used to estimate MSS in 2019 is different from that in 2020, there is a bias towards intra- and inter-prefectural mobility derived from MSS in 2019 and 2020. Hence, it is not appropriate to consider mobility in 2019 as normal and to directly compare mobility trends in 2020 with the same period in 2019. Instead, we estimated normal mobility based on the seasonality in 2019 and the population mobility in January 2020, as summarized in (3), (4). Japan confirmed the first case of COVID-19 in mid-January 2020, and the government announced its response plan in late February. In January, the number of infection cases was very low and COVID-19 had little impact on individual travel and daily life. Therefore, we considered the population mobility in January 2020 to be normal. Given the variability in population mobility on each day of the week and on public holidays, we calculated normal mobility for each day of the week and public holidays in each month.

| (3) |

| (4) |

where is the normal number of intra-prefectural trips in prefecture i on feature day d ({Monday, Tuesday, …, Sunday, Public holiday}) in month m (), is the normal number of inter-prefectural flow from prefecture i to prefecture j on feature day d in month m, and denote the average number of intra-prefectural trips in prefecture i and the average number of inter-prefectural flow from prefecture i to prefecture j, respectively, on feature day d in month m 2019, and denote the average number of intra-prefectural trips in prefecture i and the average number of inter-prefectural flow from prefecture i to prefecture j, respectively, on feature day d in January 2020.

4.2. Modeling transmission dynamics of COVID-19

4.2.1. SEPIR model with population mobility

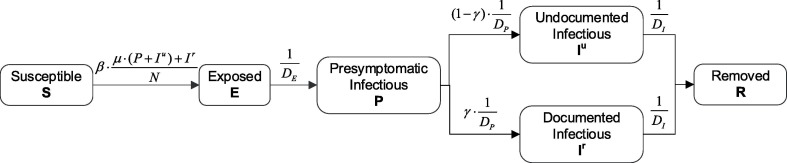

As illustrated in Fig. 2 , we characterized the COVID-19 pandemic by extending the classic SEIR model to a SEPIR model, which includes susceptible (S), exposed (E), presymptomatic infectious (P), undocumented infectious (Iu), documented infectious (Ir), and removed (R) compartments (Hao et al., 2020, Li et al., 2020):

-

▪

Susceptible compartment (S): the general population who have not been infected

-

▪

Exposed compartment (E): individuals who are infected, but are in the latent period and are not contagious

-

▪

Presymptomatic infectious compartment (P): people who are infected and contagious, but do not show symptoms

-

▪

Undocumented infectious compartment (Iu): asymptomatic and mildly symptomatic individuals who are contagious but not detected

-

▪

Documented infectious compartment (Ir): symptomatic individuals who are contagious and detected

-

▪

Removed compartment (R): people who have recovered or died from the disease

Fig. 2.

Illustration of the SEPIR model.

Although there is no presymptomatic stage for asymptomatic individuals, we consider asymptomatic individuals as a special case of mildly symptomatic individuals and model both with a presymptomatic stage (Hao et al., 2020). In the SEPIR model, the dynamics of these compartments are represented as:

| (5) |

| (6) |

| (7) |

| (8) |

| (9) |

| (10) |

| (11) |

where , , , , and are the susceptible, exposed, presymptomatic infectious, undocumented infectious, documented infectious, and removed subpopulation, respectively, in prefecture i on day t, and is the total population of prefecture i. Additionally, is the transmission rate for documented infections, is the transmission reduction factor for presymptomatic and undocumented infections, is the fraction of documented infections, , , and are the mean latent period, the mean presymptomatic infectious period, and the mean symptomatic infectious period, respectively.

Further, we incorporated population mobility into the compartmental model to reflect the impact of mobility dynamics on the spread of COVID-19. A great number of people commute between different prefectures in the Tokyo Megalopolis Region, which promotes the spatial transmission of COVID-19 across prefectures. Massive inter-prefectural commuting also leads to different population compositions in each prefecture in the daytime and nighttime, so we separated the transmission equations into two parts inspired by Pei et al., 2018, Kondo, 2021.

In the daytime, the inter-prefectural mobility was incorporated into the SEPIR model through a spatial matrix estimated from daily inter-prefectural population mobility data. Let denote the probability matrix of travel between prefectures during the daytime on day t.

| (12) |

where is the probability of people traveling from prefecture i to prefecture j during the daytime on day t, and the sum of in a row equals one. The number of people from prefecture i to prefecture j on day t can be expressed as . We assume that the travel probability matrix is common to susceptible, exposed, presymptomatic infectious, undocumented infectious, documented infectious and removed compartments. Then, the number of the susceptible, exposed, presymptomatic infectious, undocumented infectious, documented infectious, and removed individuals from prefecture i to prefecture j during the daytime on day t, denoted as , , , , and , respectively, can be calculated as: , , , , , and .

We assume that people are exposed to the risk of infection in the prefecture where they are present. For example, the subpopulation living in prefecture i and commuting to prefecture j is involved in COVID-19 transmission in prefecture j during the daytime. Note that we treat inter-prefectural random visitors in the same way as inter-prefectural commuters for the sake of simplicity. Additionally, the spatial distribution of infectious individuals affects the risk of infection in each prefecture (Kondo, 2021). The number of presymptomatic infectious, undocumented infectious, documented infectious individuals in prefecture j during the daytime on day t, denoted as , , and , respectively, can be estimated as , , and , and the population in prefecture j during the daytime is . Here represents the Tokyo Megalopolis Region, and where prefectures 0, 1, 2, and 3 denote Tokyo, Chiba, Kanagawa, and Saitama, respectively. Then, the transmission dynamics in the daytime are described as:

| (13) |

| (14) |

| (15) |

| (16) |

| (17) |

| (18) |

Intra-prefectural mobility reflects the level of contact and affects the level of transmission. Inspired by Nouvellet et al. (2021), we linked daily intra-prefectural mobility to transmission rates. Considering the time-varying strength of public health interventions, there is change in the relationship between mobility and transmission (Nouvellet et al., 2021). We thus set different baseline transmission rates for different periods, as follows.

| (19) |

where represents the baseline transmission rate in prefecture i during the period s and is the relative mobility within prefecture i on day t. For , we firstly smoothed weekly intra-prefectural mobility patterns using a 7-day rolling average and then compared the smoothed mobility to the maximum mobility before the pandemic, as summarized in (20).

| (20) |

where is the number of intra-prefectural trips in prefecture i on day t after smoothing, and denotes the maximum number of intra-prefectural trips in prefecture i in January 2020. When intra-prefectural mobility is at its peak, is equal to the baseline transmission rate. Reduced mobility leads to reductions in the transmission rate. In addition, the time-varying control measures, such as increased testing capacity, also affect the fraction of documented infections. Therefore, we assume different fractions of documented infections in different periods, i.e., .

In the nighttime, we assume that there is no inter-prefectural transmission for simplicity and people are exposed to the risk of infection in the prefecture of residence. Then, the dynamics of the compartments in the nighttime can be described by equations (5), (6), (7), (8), (9), (10). The transmission rate in the nighttime is considered to be the same as that during the daytime. In line with Pei et al. (2018), we assume that the daytime and nighttime transmissions last for 8 h and 16 h, respectively. That is, the spread of COVID-19 is described by the daytime equations (13), (14), (15), (16), (17), (18) for 1/3 days and then by the nighttime equations (5), (6), (7), (8), (9), (10) for the subsequent 2/3 days.

The effective reproduction number represents the expected number of secondary cases arising from a primary case infected at time t and is usually used to evaluate the effectiveness of public health interventions (Khailaie et al., 2021, Nouvellet et al., 2021). In our model, the effective reproduction number is approximately:

| (21) |

where is the time-varying effective reproduction number in prefecture i on day t. If the value of is and remains below one, the outbreak will die out, whereas a sustained outbreak is likely if is larger than one.

4.2.2. Model initialization and parameter estimation

We consider the disease-specific parameters to be independent of a specific region and derive their values from the existing studies. We assume that the mean incubation period is 5.2 days and the mean presymptomatic infectious period is 2.3 days (Hao et al., 2020, He et al., 2020). Then, we obtained the mean latent period of days (Hao et al., 2020). Additionally, we set the mean symptomatic infectious period to 3.0 days and the transmission reduction factor for presymptomatic and undocumented infections to 0.5 (Hao et al., 2020, Li et al., 2020). Apart from the disease-specific parameters, other parameters and are influenced by the time-varying strength of control measures, so their values were determined by fitting the observed data.

Based on the disease-specific parameter settings, we then set the initial states and estimated parameters ( and ) following the methods of Hao et al. (2020). We specified the initial state of the model on March 10, 2020. Although infections were reported prior to this date, these cases were sporadic. We set the initial number of documented cases as the number of cases in which individuals experienced symptom onset and were reported during March 8–10, 2020. With the initial fraction of documented infections as , the initial number of undocumented cases was specified as . We denoted and as the number of reported cases during March 13–15, 2020 and March 11–12, 2020, respectively. Then, the initial numbers of exposed and presymptomatic individuals were and , respectively. We assume = 0.2 in our analysis.

Considering the time-varying strength of public health interventions, we divided the analysis period into five periods based on key interventions and events: March 11 – April 6 (Early stage of the pandemic), April 7 – May 25 (State of Emergency), May 26 – July 26 (Post-Emergency), July 27 – September 30 (Go to Travel campaign, excluding Tokyo), October 1 – December 27 (Go to Travel and Go to Eat campaigns). We fitted the observed data from March 11 to November 30, 2020 and predicted the spread of COVID-19 in December 2020 using the fitted model. We assume that the number of reported cases in prefecture i on day t, denoted as , follows a Poisson distribution with rate . Here represents the expected number of new documented cases on day , and is the reporting delay between symptom onset date and confirmation date (Pan et al., 2020, Li et al., 2020). We set d to 4 days, because according to the guidelines for consultation and medical care regarding new coronavirus infections in Japan, people with symptoms of a cold or a fever of 37.5 °C or higher for more than 4 days need to consult a public health center (Ogata and Tanaka, 2020, Shimizu and Negita, 2020). Then, the likelihood function is

| (22) |

where denotes the set of days in the period s. We estimated parameters and for each period sequentially by Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) with the delayed rejection adaptive metropolis algorithm. We used flat priors of Unif(0.1, 2.5) for and Unif(0.15, 0.7) for . The initial prior range of was chosen according to Li et al. (2020), while the initial prior range of was set to enable a broad initial range for (i.e., [0.3, 6.0]). We ran the MCMC with 30,000 burn-in iterations and an additional 100,000 iterations with a sampling step of 10, resulting in 10,000 MCMC samples. The convergency was evaluated by repeating MCMC with different sets of initial values. The estimated parameters were presented as posterior means and 95% credible intervals of 10,000 MCMC samples. All the analyses were performed in R (version 3.6.3), and MCMC was performed using the R package BayesianTools.

5. Results

5.1. Descriptive analysis

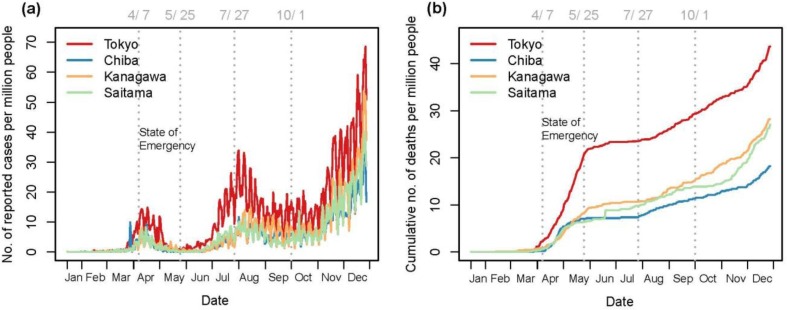

Fig. 3 presents the number of newly reported cases and the cumulative number of deaths per million people in the Tokyo Megalopolis Region per day from January 15 to December 27, 2020. Based on the number of new cases per day, the COVID-19 pandemic can be divided into three waves: the first and second waves peaked in mid-April and early August, respectively; the third wave of COVID-19 appeared to be gathering momentum in December. A state of emergency was declared to control the first wave of COVID-19, which turned out to be effective. The number of newly reported cases gradually decreased during the state of emergency. Regarding the number of deaths attributed to COVID-19, it increased fast in April and May. As testing capacity and medical resources improved, deaths caused by COVID-19 decreased. By the end of 2020, the case fatality ratio (i.e., the number of deaths as a percentage of the number of cases) in the region was 1.15%. Additionally, Tokyo had far more cases and deaths than the three neighboring prefectures.

Fig. 3.

Number of reported cases (a) and cumulative number of deaths (b) in the Tokyo Megalopolis Region.

A great number of people commute between different prefectures in the Tokyo Megalopolis Region. According to the daily inter-prefectural population flow in 2020, the inter-prefectural flow from Chiba, Kanagawa, and Saitama to Tokyo accounted for approximately 93% of the total inter-prefectural inflow to Tokyo, and 87% of inter-prefectural travelers from Tokyo went to the three neighboring prefectures. As the government announced the COVID-19 countermeasures at the end of February and schools were temporarily closed from March 2, population mobility within and between prefectures significantly decreased in March, as shown in Fig. 4 and Fig. 5 . The declaration of a state of emergency resulted in a further reduction in intra- and inter-prefectural travel demand, in line with the findings of Arimura et al., 2020, Okamoto, 2021. During the state of emergency, daily intra-prefectural trips were reduced by an average of 44%, 14%, 27% and 15% from normal mobility in Tokyo, Chiba, Kanagawa, and Saitama, respectively. Tokyo had the largest decrease in the number of intra-prefectural trips, indicating the most flexible travel demand. The number of inter-prefectural travelers was also substantially reduced, with daily inter-prefectural population flow during the state of emergency being an average of 50% lower than normal. This suggests that people significantly reduced travel during the state-of emergency, although travel restrictions and stay-at-home requests were recommended rather than mandatory. Also, the promotion of telework contributed to large reductions in intra- and inter-prefectural mobility.

Fig. 4.

Changes in number of daily intra-prefectural trips over time (a) and from normal (b).

Fig. 5.

Changes in number of daily inter-prefectural flow over time (a) and from normal (b).

Moreover, people had started to reduce travel prior to the state of emergency, in line with the findings of Hara and Yamaguchi, 2021, Dantsuji et al., 2020. This implies that people changed their travel behavior not only in response to government policy but also based on information about COVID-19 cases. After the state of emergency was lifted, people gradually increased their frequency of travel. The intra- and inter-prefectural population mobility showed a slight upward trend since June, although the COVID-19 was still rampant. This may be because that people were tired of staying at home for a long period of time and their perceived risk of COVID-19 decreased over time (Kim and Kwan, 2021, Lyu and Takikawa, 2021). In addition, daily travel demand within and between prefectures dropped substantially in mid-August because of the Obon Festival (August 13–16) in Japan. On some weekends and holidays in September and October, intra- and inter-prefectural travel was near or even above normal, which may be caused by the “Go To” campaign and comfortable weather.

5.2. Model results

We fitted the daily incidences in Tokyo and three neighboring prefectures from March 11 to November 30, and predicted the trends in December using parameters from the fifth period (October 1–November 30). The estimates of parameters are presented in Table 1 . The fractions of documented infections were low throughout the analysis period: 0.18 (95% CI: 0.15–0.22) and 0.19 (95% CI: 0.18–0.20) for the first two periods, and 0.32 (95% CI: 0.28–0.36), 0.31 (95% CI: 0.30–0.32) and 0.27 (95% CI: 0.25–0.28) for the remaining three periods. The government had expanded the testing capacity since May, so the reported rates were higher in the latter three periods than before. However, given the asymptomatic nature of many infected individuals and the recommendation for consultation and medical care after the onset of symptoms for more than 4 days in Japan (Ogata and Tanaka, 2020, Shimizu and Negita, 2020), a great number of infections were not confirmed and reported. Substantial undocumented infections facilitated the spread of COVID-19, in line with previous studies (Hao et al., 2020, Li et al., 2020). Moreover, the baseline transmission rates from susceptible to exposed stages varied across prefectures, indicating that transmission dynamics were spatially heterogeneous. As Tokyo is the most densely populated prefecture with the most socioeconomic activities in this region, the baseline transmission rate in Tokyo was the largest during the early stage of the pandemic.

Table 1.

Estimated parameters of the SEPIR model.

| Parameter | Mar 11– Apr 6 |

Apr 7– May 25 |

May 26– Jul 26 |

Jul 27– Sep 30 |

Oct 1– Nov 30 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fraction of documented infections | 0.18 (0.15–0.22) |

0.19 (0.18–0.20) |

0.32 (0.28–0.36) |

0.31 (0.30–0.32) |

0.27 (0.25–0.28) |

| Baseline transmission rate | |||||

| Tokyo | 1.00 (0.94–1.05) |

0.33 (0.32–0.33) |

0.62 (0.61–0.64) |

0.38 (0.38–0.39) |

0.49 (0.48–0.49) |

| Chiba | 0.73 (0.68–0.78) |

0.17 (0.15–0.19) |

0.47 (0.45–0.49) |

0.31 (0.30–0.31) |

0.39 (0.38–0.39) |

| Kanagawa | 0.71 (0.66–0.77) |

0.31 (0.29–0.32) |

0.42 (0.40–0.44) |

0.37 (0.36–0.37) |

0.39 (0.39–0.40) |

| Saitama | 0.59 (0.54–0.64) |

0.24 (0.22–0.26) |

0.46 (0.44–0.47) |

0.28 (0.27–0.29) |

0.41 (0.40–0.42) |

Note: the parameters are presented as mean (95% credible intervals) based on 10,000 MCMC samples.

Based the mean estimates of the parameters, the fitted and predicted results are shown in Fig. 6 . Our model fits the observed data well, and the predicted trends are consistent with the actual situation in all prefectures except Kanagawa. The number of infections in Kanagawa prefecture increased rapidly in December, and this rapid spread was different from that of the fifth period (October 1–November 30). Therefore, the spread trend of COVID-19 in Kanagawa in December could not be well predicted using the estimated parameters of the fifth period. The rapid spread of COVID-19 in Kanagawa in December was influenced by the trend of COVID-19 transmission in the other three prefectures, and the hot springs in Kanagawa might also play a role. Many famous hot springs (e.g., Hakone Onsen) are located in Kanagawa, and in winter people like to spend their vacations in places with hot springs.

Fig. 6.

Number of new documented cases per day in Tokyo (a), Chiba (b), Kanagawa (c) and Saitama (d).

We further calculated the effective reproduction number. Table 2 shows the mean values for different periods. With a series of public health interventions during the state of emergency, the effective reproduction numbers were substantially reduced to less than 1, thus controlling the spread of COVID-19. The mean effective reproduction numbers during the state of emergency were 75%, 79%, 63% and 62% lower in Tokyo, Chiba, Kanagawa and Saitama, respectively, than during the early stage of the pandemic (March 11–April 6). This was mainly attributed to 32%, 7%, 17%, and 8% reductions in relative mobility and significant decreases in baseline transmission rates. In other words, stay-at-home requests, travel restrictions and other control measures during the state of emergency curbed the spread of COVID-19, in line with the findings of Kuniya (2020). After the state of emergency was lifted, the effective reproduction numbers increased to larger than 1 during the third period (May 26–July 26) and the number of infections considerably increased. Compared to the third period, the relative mobility showed a slight increase in the fourth period (July 27–September 30), whereas the mean effective reproduction numbers decreased. This may be because that the significant increase in infections raised the awareness of risk and people were more inclined to place self-restrictions such as wearing masks and social distancing (e.g., refraining from large gatherings). The pandemic control in the fourth period suggested that smaller reduction in population mobility could curb the spread of COVID-19. Afterwards, as Go to Travel and Go to Eat campaigns were undertook during the fifth period (October 1–November 30), the relative mobility increased compared to the third and fourth periods. Coupled with a decrease in perceived risk of COVID-19 over time, the effective reproduction numbers increased again. This implies a two-way relationship between the spread of infectious diseases and human behavior.

Table 2.

Mean effective reproduction number for different periods.

| Prefecture | Mar 11– Apr 6 |

Apr 7– May 25 |

May 26– Jul 26 |

Jul 27– Sep 30 |

Oct 1– Nov 30 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tokyo | 2.37 (0.79) | 0.60 (0.54) | 1.48 (0.73) | 0.92 (0.74) | 1.23 (0.81) |

| Chiba | 2.00 (0.93) | 0.43 (0.86) | 1.38 (0.93) | 0.90 (0.95) | 1.14 (0.96) |

| Kanagawa | 1.84 (0.88) | 0.69 (0.73) | 1.13 (0.85) | 1.01 (0.88) | 1.10 (0.92) |

| Saitama | 1.60 (0.93) | 0.61 (0.85) | 1.32 (0.93) | 0.81 (0.94) | 1.21 (0.96) |

Note: the average relative mobility is shown in parentheses.

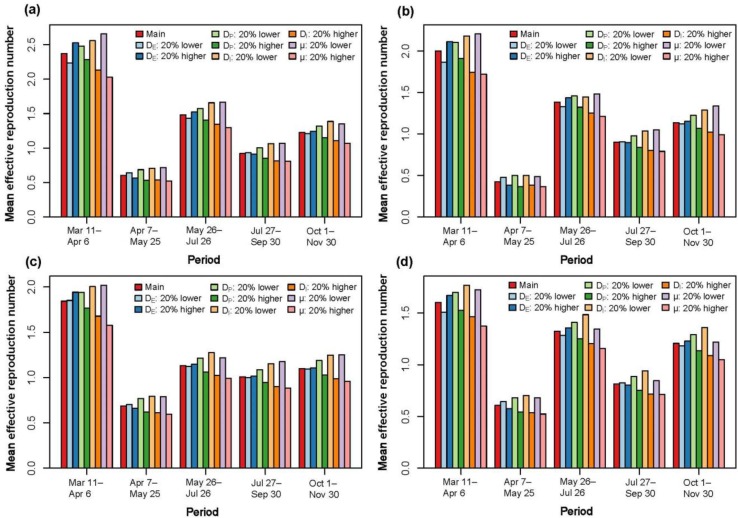

We conducted a series of sensitivity analyses to test the robustness of our results by varying the fixed disease-specific parameters, including the mean latent period , the mean presymptomatic infectious period , the mean symptomatic infectious period , and the transmission reduction factor . In each test, we specified the value of one parameter to be 20% lower or higher than the true value, while the other parameters remained unchanged. Based on the modified disease-specific parameters, we ran the MCMC method to estimate the parameters and , and then calculated effective reproduction number . As presented in Table 3 , estimates of fraction of documented infections are insensitive to changes in disease-specific parameters, indicating that the existence of a great number of undocumented cases is robust. Another major finding is that a substantial decrease in effective reproduction number during the state of emergency is robust to changes in disease-specific parameters, as shown in Fig. 7 . This demonstrates the robustness of the positive role of stay-at-home requests and travel restrictions in preventing the spread of COVID-19. Moreover, the changes in effective reproduction number are consistent over the five periods for different disease-specific parameters, which suggests that our evaluation results of the effect of nonpharmaceutical interventions on COVID-19 transmission is robust.

Table 3.

Estimated fractions of documented infections with different disease-specific parameters.

| Analysis | Mar 11–Apr 6 | Apr 7–May 25 | May 26–Jul 26 | Jul 27–Sep 30 | Oct 1–Nov 30 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Main | 0.18 (0.15–0.22) | 0.19 (0.18–0.20) | 0.32 (0.28–0.36) | 0.31 (0.30–0.32) | 0.27 (0.25–0.28) |

| : 20% lower | 0.18 (0.15–0.23) | 0.19 (0.18–0.19) | 0.31 (0.28–0.34) | 0.31 (0.29–0.32) | 0.26 (0.25–0.27) |

| : 20% higher | 0.20 (0.16–0.24) | 0.20 (0.19–0.20) | 0.35 (0.32–0.39) | 0.34 (0.33–0.35) | 0.29 (0.28–0.30) |

| : 20% lower | 0.17 (0.15–0.20) | 0.19 (0.19–0.20) | 0.30 (0.26–0.33) | 0.30 (0.28–0.31) | 0.25 (0.24–0.26) |

| : 20% higher | 0.19 (0.16–0.23) | 0.19 (0.19–0.20) | 0.36 (0.32–0.40) | 0.34 (0.33–0.35) | 0.30 (0.28–0.31) |

| : 20% lower | 0.18 (0.15–0.21) | 0.18 (0.18–0.19) | 0.34 (0.31–0.38) | 0.33 (0.32–0.34) | 0.29 (0.27–0.30) |

| : 20% higher | 0.19 (0.18–0.21) | 0.19 (0.19–0.20) | 0.29 (0.25–0.32) | 0.28 (0.27–0.29) | 0.25 (0.24–0.26) |

| : 20% lower | 0.18 (0.15–0.22) | 0.18 (0.18–0.19) | 0.32 (0.28–0.35) | 0.31 (0.30–0.32) | 0.27 (0.25–0.28) |

| : 20% higher | 0.18 (0.15–0.22) | 0.18 (0.18–0.19) | 0.32 (0.28–0.35) | 0.31 (0.29–0.32) | 0.27 (0.25–0.28) |

Note: the parameters are presented as mean (95% credible intervals) based on 10,000 MCMC samples.

Fig. 7.

Mean effective reproduction number for different periods in Tokyo (a), Chiba (b), Kanagawa (c) and Saitama (d).

5.3. Policy analysis

We constructed seven hypothetical scenarios to analyze the impact of different policies on the spread of COVID-19, as follows.

-

▪

Scenario 1 (S1): we assumed no state of emergency from April 7 to May 25 and the same nonpharmaceutical interventions since April 7 as in the early phase of the pandemic (March 11–April 6). That is, since April 7, the baseline transmission rates (), the fractions of documented infections (), and population mobility within and between prefectures were the same as in the early phase.

-

▪

Scenario 2 (S2): We assumed that the start date of the state of emergency was advanced by one week, i.e., the start date was March 31 instead of April 7. Specifically, we assumed that the parameters ( and ) and population mobility within and between prefectures from March 31 to April 6 were the same as during the state of emergency.

-

▪

Scenario 3 (S3): We assumed that the start date of the state of emergency was postponed by one week, i.e., the start date was April 14 instead of April 7. Specifically, we assumed that the parameters ( and ) and population mobility from April 7 to April 13 were the same as in the early phase of the pandemic.

-

▪

Scenario 4 (S4): We assumed a 10% increase in intra- and inter-prefectural population mobility since the start date of the state of emergency. Increased population mobility raises the likelihood of close person-to-person contact, leading to an increase in baseline transmission rates (). For simplicity, we assumed a 10% increase in the parameters as well.

-

▪

Scenario 5 (S5): we assumed a state of emergency during the second wave of the pandemic, i.e., the parameters and population mobility since July 27 were the same as during the state of emergency, while the parameter was same as the most recent period (May 26–July 26).

-

▪

Scenario 6 (S6): we assumed a state of emergency during the third wave of the pandemic, i.e., the parameters and population mobility since December 1 were the same as during the state of emergency, while the parameter was same as the most recent period (October 1–November 30).

-

▪

Scenario 7 (S7): We assumed that since December 1, the Go to Travel campaign and the Go to Eat campaign was suspended, while voluntary self-restrictions were the same as during the peak period of the second wave. Accordingly, the parameters and population mobility since December 1 were the same as during fourth period (July 27–September 30), while the parameter was same as the most recent period (October 1–November 30).

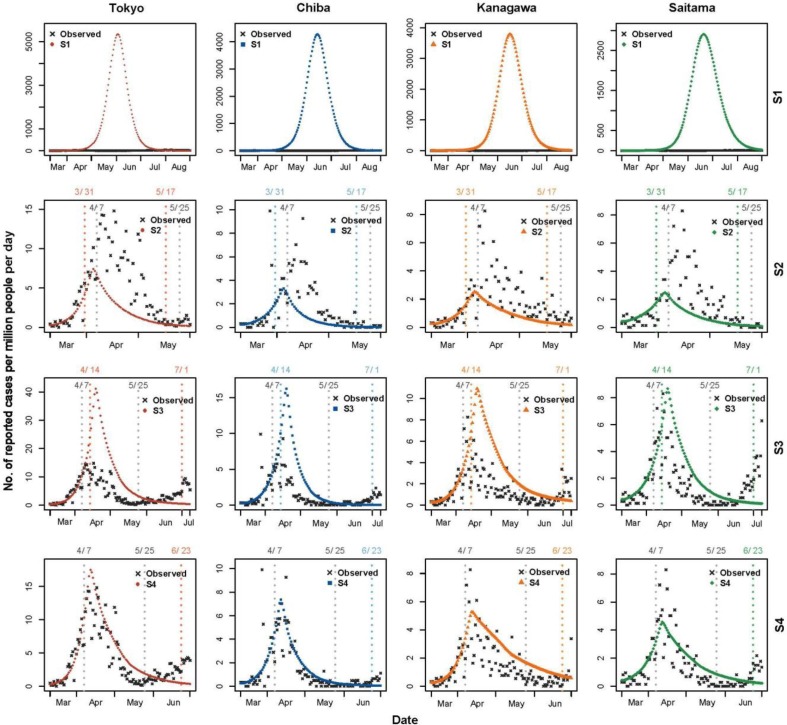

The simulation results are shown in Fig. 8 and Fig. 9 . In these two figures, each column represents a prefecture as indicated on the top, and each row represents the simulation results for the four prefectures in one or two scenarios as indicated on the right. Each subplot has the number of newly reported cases per million people per day on the vertical axis and the date on the horizontal axis.

Fig. 8.

Simulation results of scenarios 1–4.

Fig. 9.

Simulation results of scenarios 5–7.

As shown in the first row of Fig. 8, without timely nonpharmaceutical interventions, the spread of COVID-19 would have been out of control, indicating the importance of interventions in the early phase of the pandemic and the necessity of a state of emergency. The government declared a state of emergency for this region from April 7 to May 25, 2020. According to the “Guidelines for Lifting the State of Emergency” in May 2020, the infection situation, medical system, and surveillance system (PCR tests) were three key factors in deciding whether to lift the state of emergency. Regarding the infection situation, the state of emergency could be lifted if there was a decreasing trend in the number of newly reported cases and the cumulative number of reported cases in the most recent week was less than 0.5 persons per 100,000 people. We used this criterion to determine when a state of emergency could be lifted in scenarios S2–S4 where the start date of the state of emergency or population mobility changed. As shown in the second row of Fig. 8, if the start date had been moved forward by one week, the peak of the first wave would have been lower and the state of emergency could have been lifted on May 17 instead of May 25. In contrast, the lifting of the state of emergency would have been greatly delayed until July 1 if the start date had been moved back by one week, as shown in the third row of Fig. 8. The later the intervention, the more difficult the outbreak could be to control. In terms of the lifting dates for scenarios 2 and 3 only, the true start date of the state of emergency is reasonable. Moreover, as shown in the fourth row of Fig. 8, if population mobility had increased by 10% during the state of emergency, the cumulative number of documented infections in this region would have increased by 25% by the end of May, and the lifting of the state of emergency would have been delayed until June 23.

If a state of emergency had been implemented during the second wave of the pandemic, the number of infections would have decreased in August and September, as displayed in the first row of Fig. 9. The cumulative number of documented infections in this region would have been 29,081 by the end of September, showing a 29% reduction. To control the third wave of the pandemic, the government declared a second state of emergency from January 7 to March 21, 2021. We assumed that the start date of the second state of emergency was December 1, 2020 instead of January 7, 2021. According to the simulation results of scenario 6, the peak of the third wave would have been much lower. The cumulative number of documented infections in this region would have decreased by 19% to 86,146 by the end of 2020. Note that the effect of the second state of emergency may be overestimated, because the repeated states of emergency may be not as effective as the first (Okamoto, 2021). Stay-at-home requests and travel restrictions during a state of emergency are recommended rather than mandatory, so the impact of implementing a state of emergency is closely related to how people react. As knowledge of COVID-19 increases over time, the perceived risk of COVID-19 decreases (Kim and Kwan, 2021, Lyu and Takikawa, 2021), making people less cooperative with control measures (e.g., stay-at-home requests). Furthermore, multiple factors need to be considered in deciding a state of emergency. Although the infection rate was low during the state of the emergency, the loss of gross domestic product (GDP) was significant. More work is needed to determine how best to balance the expected positive impact on public health with the negative effect on the economy, society, and freedom of movement (Kraemer et al., 2020).

Based on the simulation results of scenario 7, the third wave of the pandemic would have been controlled without a state of emergency if people had behaved in the same way as during the second wave of the pandemic. However, because of the “Go To” campaign and the reduced perceived risk of COVID-19, population mobility and infection rates did not decrease in December, resulting in a high peak of the number of daily infections. This reflects the guidance of official policies on people’s behavior. Without the implementation of the Go to Travel and Go to Eat campaigns in December, the number of infections would have decreased.

6. Conclusions

This study explored the role of stay-at-home requests and travel restrictions in preventing the spread of COVID-19 in Japan. Our methodological contribution resides in the novel compartmental model with population mobility. Given the infectiousness of presymptomatic and asymptomatic individuals, we characterized the COVID-19 pandemic by extending the classic SEIR model to a SEPIR model, including susceptible (S), exposed (E), presymptomatic infectious (P), undocumented infectious (Iu), documented infectious (Ir), and removed (R) compartments. Further, we linked intra-prefectural mobility to transmission rates in the home prefecture and incorporated inter-prefectural mobility into the SEPIR model through a spatial matrix to represent the impact of inter-prefectural commuting flows on the spatial transmission of COVID-19. Moreover, the time-varying baseline transmission rates and reported rates in the model can capture the time-varying strength of public health interventions. This model is applicable to analyze the spread of COVID-19 in metropolitan areas with a great number of intercity commuters.

The empirical contribution is that our findings shed light on the effectiveness of soft containment measures in curbing the spread of COVID-19. Although stay-at-home requests and travel restrictions during the state of emergency in Japan were recommended rather than mandatory, people significantly reduced travel, with daily intra-prefectural trips 10%–50% lower than normal and daily inter-prefectural population flow 20%–70% lower than normal in the Tokyo Megalopolis Region. The reduction in population mobility, combined with other control measures, resulted in a substantial reduction in effective reproduction numbers to below 1, thereby controlling the spread of COVID-19. It is worth noting that stay-at-home requests and travel restrictions during repeated states of emergency may be not as effective as during the first state of emergency (Okamoto, 2021). As knowledge of COVID-19 increases over time and the perceived risk of COVID-19 decreases (Kim and Kwan, 2021, Lyu and Takikawa, 2021), people are less likely to comply with stay-at-home requests and travel restrictions. Moreover, there is a time-varying relationship between human mobility and COVID-19 transmission (Kim and Kwan, 2021, Nouvellet et al., 2021). The intra- and inter-prefectural population mobility during the fourth period (July 27–September 30) showed small changes compared to the early phase of the pandemic (March 11–April 6), whereas the effective reproduction numbers decreased substantially to below 1 and the number of infections gradually decreased. The dampening of the second wave of the pandemic indicated that smaller reductions in population mobility could result in pandemic control, probably because of other social distancing behaviors. This, however, was not sufficient to prevent the third wave of the pandemic, as population mobility and thus contact rates increased. To control the third wave of the pandemic, Japan declared its second state of emergency. Future work that evaluates the role of repeated states of emergency in curbing the spread of COVID-19 will provide deeper insights into the effectiveness of soft containments.

This study has several limitations. First, MSS are estimated from operational data of a mobile terminal network, and they cannot be estimated for the age groups with very low mobile terminal penetration. Therefore, population estimates using the MSS are limited to the age range of 15 to 79 years (Okajima et al., 2013). Second, our model assumes homogeneous transmission within the population and does not consider the heterogeneity between groups such as age, gender, and travel mode. The inclusion of population division and joint analysis using data from other metropolitan areas will improve our understanding of the impact of mobility dynamics on the spread of COVID-19. Third, many nonpharmaceutical interventions are implemented simultaneously and have an impact on both population mobility and COVID-19 pandemic; also, there is a two-way relationship between population mobility and COVID-19 transmission. However, we assume that population mobility is exogenous in our model, so more work is needed to explore the causal relationship between population mobility and COVID-19 transmission.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Shasha Liu: Methodology, Software, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Toshiyuki Yamamoto: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Supervision.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank DOCOMO Insight Marketing, Inc. for providing the Mobile Spatial Statistics for this study. We are also grateful to Professor Cynthia Chen from the University of Washington for her constructive advice on this study.

References

- Abdullah M., Ali N., Hussain S.A., Aslam A.B., Javid M.A. Measuring changes in travel behavior pattern due to COVID-19 in a developing country: A case study of Pakistan. Transp. Policy. 2021;108:21–33. doi: 10.1016/j.tranpol.2021.04.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anzai A., Kobayashi T., Linton N.M., Kinoshita R., Hayashi K., Suzuki A., Yang Y., Jung S.M., Miyama T., Akhmetzhanov A.R., Nishiura H. Assessing the impact of reduced travel on exportation dynamics of novel coronavirus infection (COVID-19) J. Clin. Med. 2020;9:601. doi: 10.3390/jcm9020601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arimura M., Ha T.V., Okumura K., Asada T. Changes in urban mobility in Sapporo city, Japan due to the Covid-19 emergency declarations. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2020;7:100212. doi: 10.1016/j.trip.2020.100212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arino J., van den Driessche P. A multi-city epidemic model. Math. Popul. Stud. 2003;10(3):175–193. doi: 10.1080/08898480306720. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Badr H.S., Du H., Marshall M., Dong E., Squire M.M., Gardner L.M. Association between mobility patterns and COVID-19 transmission in the USA: a mathematical modelling study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020;20(11):1247–1254. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30553-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck M.J., Hensher D.A. Insights into the impact of COVID-19 on household travel and activities in Australia – The early days under restrictions. Transp. Policy. 2020;96:76–93. doi: 10.1016/j.tranpol.2020.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohman H., Ryan J., Stjernborg V., Nilsson D. A study of changes in everyday mobility during the Covid-19 pandemic: As perceived by people living in Malmö, Sweden. Transp. Policy. 2021;106:109–119. doi: 10.1016/j.tranpol.2021.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang M.C., Baek J.H., Park D. Lessons from South Korea regarding the early stage of the COVID-19 outbreak. Healthcare. 2020;8(3):229. doi: 10.3390/healthcare8030229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinazzi M., Davis J.T., Ajelli M., Gioannini C., Litvinova M., Merler S., Pastore y Piontti A., Mu K., Rossi L., Sun K., Viboud C., Xiong X., Yu H., Halloran M.E., Longini I.M., Vespignani A. The effect of travel restrictions on the spread of the 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak. Science (80-.) 2020;368(6489):395–400. doi: 10.1126/science.aba9757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dantsuji, T., Sugishita, K., Fukuda, D., 2020. Understanding changes in travel patterns during the COVID-19 outbreak in the three major Metropolitan Areas of Japan, arXiv:2012.13139 (Accessed on August 1, 2021).

- de Haas M., Faber R., Hamersma M. How COVID-19 and the Dutch ‘intelligent lockdown’ change activities, work and travel behaviour: Evidence from longitudinal data in the Netherlands. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2020;6:100150. doi: 10.1016/j.trip.2020.100150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding Y., Wandelt S., Sun X. TLQP: Early-stage transportation lock-down and quarantine problem. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2021;129:103218. doi: 10.1016/j.trc.2021.103218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flaxman S., Mishra S., Gandy A., Unwin H.J.T., Mellan T.A., Coupland H., Whittaker C., Zhu H., Berah T., Eaton J.W., Monod M., Perez-Guzman P.N., Schmit N., Cilloni L., Ainslie K.E.C., Baguelin M., Boonyasiri A., Boyd O., Cattarino L., Cooper L.V., Cucunubá Z., Cuomo-Dannenburg G., Dighe A., Djaafara B., Dorigatti I., van Elsland S.L., FitzJohn R.G., Gaythorpe K.A.M., Geidelberg L., Grassly N.C., Green W.D., Hallett T., Hamlet A., Hinsley W., Jeffrey B., Knock E., Laydon D.J., Nedjati-Gilani G., Nouvellet P., Parag K.V., Siveroni I., Thompson H.A., Verity R., Volz E., Walters C.E., Wang H., Wang Y., Watson O.J., Winskill P., Xi X., Walker P.G.T., Ghani A.C., Donnelly C.A., Riley S., Vollmer M.A.C., Ferguson N.M., Okell L.C., Bhatt S. Estimating the effects of non-pharmaceutical interventions on COVID-19 in Europe. Nature. 2020;584(7820):257–261. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2405-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guidelines for Lifting the State of Emergency, derived from the Japanese government website, https://japan.kantei.go.jp/ongoingtopics/_00025.html (Accessed on October 1, 2021).

- Hale T., Angrist N., Goldszmidt R., Kira B., Petherick A., Phillips T., Webster S., Cameron-Blake E., Hallas L., Majumdar S., Tatlow H. A global panel database of pandemic policies (Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker) Nat. Hum. Behav. 2021;5(4):529–538. doi: 10.1038/s41562-021-01079-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao X., Cheng S., Wu D., Wu T., Lin X., Wang C. Reconstruction of the full transmission dynamics of COVID-19 in Wuhan. Nature. 2020;584(7821):420–424. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2554-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara Y., Yamaguchi H. Japanese travel behavior trends and change under COVID-19 state-of-emergency declaration: Nationwide observation by mobile phone location data. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2021;9:100288. doi: 10.1016/j.trip.2020.100288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He X., Lau E.H.Y., Wu P., Deng X., Wang J., Hao X., Lau Y.C., Wong J.Y., Guan Y., Tan X., Mo X., Chen Y., Liao B., Chen W., Hu F., Zhang Q., Zhong M., Wu Y., Zhao L., Zhang F., Cowling B.J., Li F., Leung G.M. Temporal dynamics in viral shedding and transmissibility of COVID-19. Nat. Med. 2020;26(5):672–675. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0869-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu S., Xiong C., Yang M., Younes H., Luo W., Zhang L. A big-data driven approach to analyzing and modeling human mobility trend under non-pharmaceutical interventions during COVID-19 pandemic. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2021;124:102955. doi: 10.1016/j.trc.2020.102955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Japan Statistical Yearbook . Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications; Japan: 2021. Statistics Bureau.https://www.stat.go.jp/english/data/nenkan/70nenkan/index.html [Google Scholar]

- Jia J.S., Lu X., Yuan Y., Xu G.e., Jia J., Christakis N.A. Population flow drives spatio-temporal distribution of COVID-19 in China. Nature. 2020;582(7812):389–394. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2284-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khailaie S., Mitra T., Bandyopadhyay A., Schips M., Mascheroni P., Vanella P., Lange B., Binder S.C., Meyer-Hermann M. Development of the reproduction number from coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 case data in Germany and implications for political measures. BMC Med. 2021;19:1–16. doi: 10.1186/s12916-020-01884-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J., Kwan M.-P. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on people’s mobility: A longitudinal study of the U.S. from March to September of 2020. J. Transp. Geogr. 2021;93:103039. doi: 10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2021.103039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo K. Simulating the impacts of interregional mobility restriction on the spatial spread of COVID-19 in Japan. Sci. Rep. 2021;11(1) doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-97170-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopsidas A., Milioti C., Kepaptsoglou K., Vlachogianni E.I. How did the COVID-19 pandemic impact traveler behavior toward public transport? The case of Athens, Greece. Transp. Lett. 2021;13(5-6):344–352. doi: 10.1080/19427867.2021.1901029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer M.U.G., Yang C.-H., Gutierrez B., Wu C.-H., Klein B., Pigott D.M., du Plessis L., Faria N.R., Li R., Hanage W.P., Brownstein J.S., Layan M., Vespignani A., Tian H., Dye C., Pybus O.G., Scarpino S.V. The effect of human mobility and control measures on the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Science (80-.) 2020;368(6490):493–497. doi: 10.1126/science.abb4218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubo T., Uryu S., Yamano H., Tsuge T., Yamakita T., Shirayama Y. Mobile phone network data reveal nationwide economic value of coastal tourism under climate change. Tour. Manag. 2020;77:104010. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2019.104010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kuniya T. Evaluation of the effect of the state of emergency for the first wave of COVID-19 in Japan. Infect. Dis. Model. 2020;5:580–587. doi: 10.1016/j.idm.2020.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M.Y., Muldowney J.S. Global stability for the SEIR model in epidemiology. Math. Biosci. 1995;125(2):155–164. doi: 10.1016/0025-5564(95)92756-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R., Pei S., Chen B., Song Y., Zhang T., Yang W., Shaman J. Substantial undocumented infection facilitates the rapid dissemination of novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) Science (80-.) 2020;368(6490):489–493. doi: 10.1126/science.abb3221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linka K., Peirlinck M., Sahli Costabal F., Kuhl E. Outbreak dynamics of COVID-19 in Europe and the effect of travel restrictions. Comput. Methods Biomech. Biomed. Engin. 2020;23(11):710–717. doi: 10.1080/10255842.2020.1759560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyu, Z., Takikawa, H., 2021. Disparity and dynamics of social distancing behaviors in Japan: An investigation of mobile phone mobility data. JMIR Preprints 27/06/2021:31557 (Accessed on August 1, 2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Nakanishi W., Yamaguchi H., Fukuda D. Feature extraction of inter-region travel pattern using random matrix theory and mobile phone location data. Transp. Res. Procedia. 2018;34:115–122. doi: 10.1016/j.trpro.2018.11.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nouvellet P., Bhatia S., Cori A., Ainslie K.E.C., Baguelin M., Bhatt S., Boonyasiri A., Brazeau N.F., Cattarino L., Cooper L.V., Coupland H., Cucunuba Z.M., Cuomo-Dannenburg G., Dighe A., Djaafara B.A., Dorigatti I., Eales O.D., van Elsland S.L., Nascimento F.F., FitzJohn R.G., Gaythorpe K.A.M., Geidelberg L., Green W.D., Hamlet A., Hauck K., Hinsley W., Imai N., Jeffrey B., Knock E., Laydon D.J., Lees J.A., Mangal T., Mellan T.A., Nedjati-Gilani G., Parag K.V., Pons-Salort M., Ragonnet-Cronin M., Riley S., Unwin H.J.T., Verity R., Vollmer M.A.C., Volz E., Walker P.G.T., Walters C.E., Wang H., Watson O.J., Whittaker C., Whittles L.K., Xi X., Ferguson N.M., Donnelly C.A. Reduction in mobility and COVID-19 transmission. Nat. Commun. 2021;12:1–9. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-21358-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogata T., Tanaka H. High probability of long diagnostic delay in coronavirus disease 2019 cases with unknown transmission route in Japan. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2020;17:1–9. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17228655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okajima I., Tanaka S., Terada M., Ikeda D., Nagata T. Supporting growth in society and industry using statistical data from mobile terminal networks: Overview of Mobile Spatial Statistics. Docomo Tech. J. 2013;14:16–23. [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto, S., 2021. State of emergency and human mobility during the COVID-19 pandemic. medRxiv 1730015, 10.1101/2021.06.16.21259061 (Accessed on August 1, 2021). [DOI]

- Oyabu Y., Terada M., Yamaguchi T., Iwasawa S., Hagiwara J., Koizumi D. Evaluating reliability of Mobile Spatial Statistics. Docomo Tech. J. 2013;14:16–23. [Google Scholar]

- Pan A., Liu L., Wang C., Guo H., Hao X., Wang Q., Huang J., He N., Yu H., Lin X., Wei S., Wu T. Association of public health interventions with the epidemiology of the COVID-19 outbreak in Wuhan, China. JAMA - J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2020;323:1915–1923. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.6130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parady G., Taniguchi A., Takami K. Travel behavior changes during the COVID-19 pandemic in Japan: Analyzing the effects of risk perception and social influence on going-out self-restriction. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2020;7:100181. doi: 10.1016/j.trip.2020.100181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pei S., Kandula S., Yang W., Shaman J. Forecasting the spatial transmission of influenza in the United States. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2018;115(11):2752–2757. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1708856115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian X., Ukkusuri S.V. Connecting urban transportation systems with the spread of infectious diseases: A Trans-SEIR modeling approach. Transp. Res. Part B Methodol. 2021;145:185–211. doi: 10.1016/j.trb.2021.01.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shibayama T., Sandholzer F., Laa B., Brezina T. Impact of covid-19 lockdown on commuting: A multi-country perspective. Eur. J. Transp. Infrastruct. Res. 2021;21:70–93. doi: 10.18757/ejtir.2021.21.1.5135. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu K., Negita M. Lessons Learned from Japan’s Response to the First Wave of COVID-19: A Content Analysis. Healthcare. 2020;8:426. doi: 10.3390/healthcare8040426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smirnova A., deCamp L., Chowell G. Forecasting Epidemics Through Nonparametric Estimation of Time-Dependent Transmission Rates Using the SEIR Model. Bull. Math. Biol. 2019;81(11):4343–4365. doi: 10.1007/s11538-017-0284-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terada M., Nagata T., Kobayashi M. Population estimation technology for Mobile Spatial Statistics. Docomo Tech. J. 2013;14:16–23. [Google Scholar]

- Unwin H.J.T., Mishra S., Bradley V.C., Gandy A., Mellan T.A., Coupland H., Ish-Horowicz J., Vollmer M.A.C., Whittaker C., Filippi S.L., Xi X., Monod M., Ratmann O., Hutchinson M., Valka F., Zhu H., Hawryluk I., Milton P., Ainslie K.E.C., Baguelin M., Boonyasiri A., Brazeau N.F., Cattarino L., Cucunuba Z., Cuomo-Dannenburg G., Dorigatti I., Eales O.D., Eaton J.W., van Elsland S.L., FitzJohn R.G., Gaythorpe K.A.M., Green W., Hinsley W., Jeffrey B., Knock E., Laydon D.J., Lees J., Nedjati-Gilani G., Nouvellet P., Okell L., Parag K.V., Siveroni I., Thompson H.A., Walker P., Walters C.E., Watson O.J., Whittles L.K., Ghani A.C., Ferguson N.M., Riley S., Donnelly C.A., Bhatt S., Flaxman S. State-level tracking of COVID-19 in the United States. Nat. Commun. 2020;11(1) doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-19652-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe T., Yabu T. Japan’s Voluntary Lockdown. Plos One. 2020;16(6) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0252468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wee B.V., Witlox F. COVID-19 and its long-term effects on activity participation and travel behaviour: A multiperspective view. J. Transp. Geogr. 2021;95:103144. doi: 10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2021.103144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong C., Hu S., Yang M., Luo W., Zhang L. Mobile device data reveal the dynamics in a positive relationship between human mobility and COVID-19 infections. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2020;117(44):27087–27089. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2010836117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yabe T., Tsubouchi K., Fujiwara N., Wada T., Sekimoto Y., Ukkusuri S.V. Non-compulsory measures sufficiently reduced human mobility in Tokyo during the COVID-19 epidemic. Sci. Rep. 2020;10:1–9. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-75033-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi H., Nakayama S. Detection of base travel groups with different sensitivities to new high-speed rail services: Non-negative tensor decomposition approach. Transp. Policy. 2020;97:37–46. doi: 10.1016/j.tranpol.2020.07.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J., Hayashi Y., Frank L.D. COVID-19 and transport: Findings from a world-wide expert survey. Transp. Policy. 2021;103:68–85. doi: 10.1016/j.tranpol.2021.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]