Abstract

PURPOSE

The HOLA COVID-19 study sought to evaluate the impact of COVID-19 on oncology practices across Latin America (LATAM), challenges faced by physicians, and how practices and physicians adapted while delivering care to patients with cancer.

METHODS

This international cross-sectional study of oncology physicians in LATAM included a 43-item anonymous online survey to evaluate changes and adaptations to clinical practice. Multivariable logistic regression analyses were used to evaluate the association of caring for patients with COVID-19 and changes to clinical practice.

RESULTS

A total of 704 oncology physicians from 19 countries completed the survey. Among respondents, the most common specialty was general oncology (34%) and 56% of physicians had cared for patients with COVID-19. The majority of physicians (70%) noted a decrease in the number of new patients evaluated during the COVID-19 pandemic when compared with prepandemic, and 73% reported adopting the use of telemedicine in their practice. More than half (58%) of physicians reported making changes to the treatments that they offered to patients with cancer. In adjusted models, physicians who had cared for patients with COVID-19 had higher odds of changing the type of chemotherapy or treatments that they offered (adjusted odds ratio 1.81; 95% CI, 1.30 to 2.53) and of delaying chemotherapy start (adjusted odds ratio 2.05; 95% CI, 1.49 to 2.81). Physicians identified significant delays in access to radiation and surgical services, diagnostic tests, and supportive care.

CONCLUSION

The COVID-19 pandemic has significantly disrupted global cancer care. Although changes to health care delivery are a necessary response to this global crisis, our study highlights the significant disruption and changes to the treatment plans of patients with cancer in LATAM resulting from the COVID-19 health care crisis.

INTRODUCTION

In late 2019, COVID-19, a disease caused by severe acute respiratory coronavirus 2, emerged across the world, leading to a global pandemic with more than 173 million cases and 3.7 million deaths as of June 2021.1 COVID-19 has disrupted health care globally, overwhelming health care systems, halting nonemergent medical procedures, and leading to scarcity of medical resources.2-4 Reports from the United States and Europe show that COVID-19 has led to an alarming decline in cancer screening, delayed diagnostic tests, and treatment modifications, which might have longstanding effects on cancer outcomes.5-8 As a result, national and international societies have published guidelines and recommendations to prioritize and adapt the care of patients with cancer during COVID-19.9-11 However, changes in physician practice patterns and cancer care in limited-resource settings, such as Latin America (LATAM), have not been thoroughly reported.

CONTEXT

Key Objective

To evaluate the impact of COVID-19 on oncology practices across Latin America.

Knowledge Generated

Physicians who cared for patients with COVID-19 were more likely to change the chemotherapy regimens that they offered to patients with cancer, to discontinue palliative chemotherapy, and to cancel or delay concurrent chemoradiation.

Relevance

There were significant disruptions in cancer care delivery, which can worsen outcomes across Latin America in the upcoming years. Our data may serve as a guide to build strategies to rebuild cancer care in the region.

Studying the impact of COVID-19 on cancer in LATAM is of utmost importance since two of the countries with the highest number of COVID-19 deaths, Brazil and Mexico, are located in the region.1 The International Agency for Research on Cancer estimated more than 1.4 million new cancer cases in LATAM for 2020,12 a number projected to increase to more than1.7 million new cases per year by 2030.13-15 Patients with cancer in LATAM face numerous barriers for obtaining adequate medical care because of limited resources and fragmented systems that have been disproportionally affected by COVID-19. Given the expected growth in cancer burden in LATAM, we must understand how cancer care in the region has changed during these unprecedented times. Therefore, we sought to evaluate the impact of COVID-19 on oncology practices across LATAM, by assessing the challenges faced by physicians in diagnosing and treating cancer and the clinical practice modifications that they adopted during the pandemic.

METHODS

Collaborator Network and Participant Recruitment

This cross-sectional study was led by a group of researchers from LATAM and the United States. LATAM is a region consisting of 20 countries and 14 territories stretching from Mexico to Tierra del Fuego (Chile and Argentina) and including the Caribbean (Cuba, Dominican Republic, and Puerto Rico).

The HOLA COVID-19 study included oncology physicians practicing in LATAM. We identified local leaders from each country using social media and the ASCO membership directory. An electronic invitation was distributed to physicians from LATAM countries to become study ambassadors. Using snowball sampling, each ambassador recruited participants via a multimodal approach, which included social media, e-mail invitations, professional society directories and mailing lists, and other local physician communication networks. Ambassadors distributed the online survey via a personal link using the SurveyMonkey platform (SurveyMonkey, San Mateo, CA) during August 4-24, 2020. The target population was physicians specialized in hematology and/or oncology, surgical oncology, radiation oncology, or gynecologic oncology. All recruitment efforts and communications were available in Spanish, Portuguese, and English.

Survey Instrument

The survey consisted of 43 questions designed by the research team, who are native bilingual Spanish/English and Portuguese/English oncology physicians (Data Supplement). Questions were written in English and translated into Spanish and Portuguese by study team members.

The questionnaire included multiple choice, Likert scale, and open-ended questions covering demographics, workplace characteristics, use of telemedicine, and changes in oncology practice (ie, delays, alterations, or cancellations of cancer therapies, surgeries, and/or radiation). The study was reviewed and considered exempt by the University of Wisconsin's Institutional Review Board.

Data Analysis

Only completed surveys were included in the analysis. Data were stratified according to whether oncology physicians had cared for patients with COVID-19 infection (on the basis of answers to “Have you taken care of cancer patients with COVID-19 infection?” Yes/No). Responses were summarized with descriptive statistics. To compare survey responses between groups, we used chi-square and Fisher's exact tests for categorical variables and McNemar's test for matched categorical variables. For ease of interpretation, chi-square tests comparing responses to questions with 5-item Likert scale answers were performed by collapsing responses to binary outcomes (ie, change in [some, most, or all cases] versus [minority of cases or no change]).

We used binary multivariable logistic regression to evaluate the association of caring for patients with COVID-19 with the primary outcome of change in clinical practice (on the basis of the survey question “Have you changed the type of chemotherapy or treatment that you offer to your cancer patients during the months of February-June 2020?” Yes/No). On the basis of expert input and significance on univariate regression (not shown), multivariable models were adjusted for physician specialty and age (used as surrogate for years in practice). Secondary exploratory outcomes included change to a less effective regimen with fewer complications or side effects, discontinuation of chemotherapy, and delay of chemotherapy start. We performed generalized ordinal logistic regression16,17 to explore the association of our secondary outcomes with caring for patients with COVID-19; respondents who selected not applicable were excluded. We used marginal effects to estimate the probability of each secondary outcome. Statistical significance was assumed at a P value < .05. Data were analyzed using Stata version 16 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

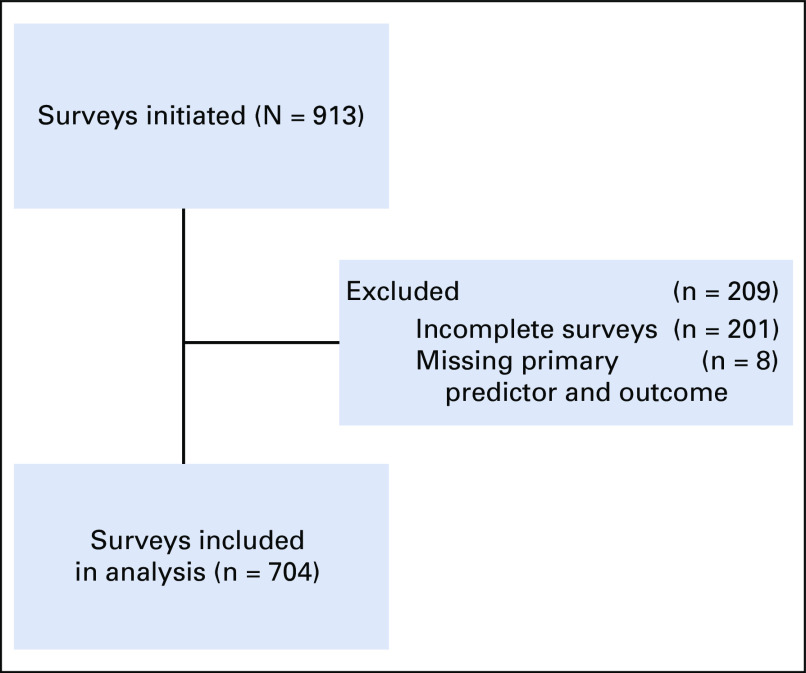

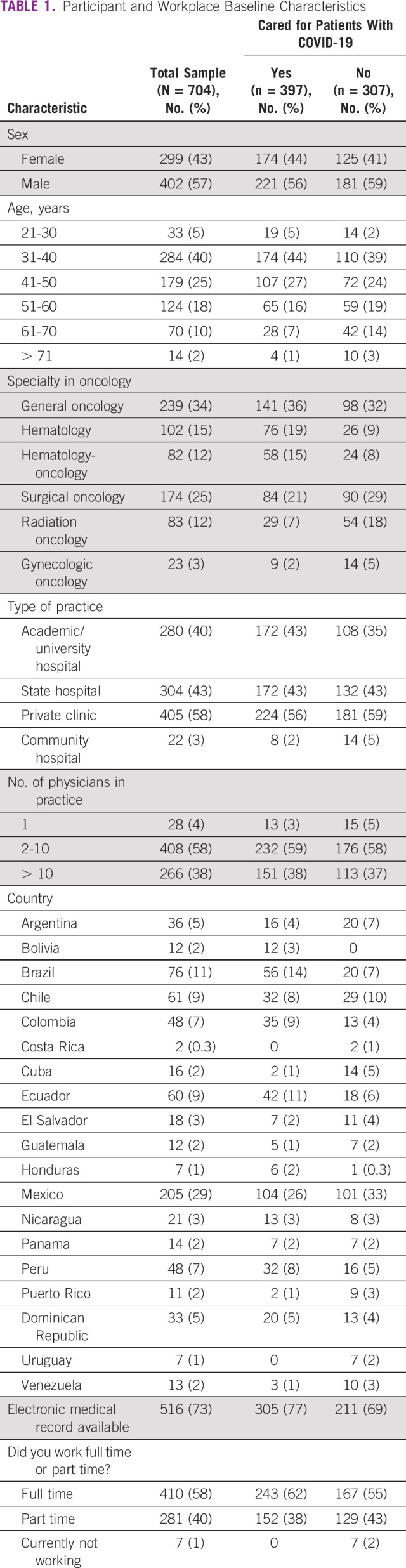

Between August 4 and 24, 2020, 913 oncology physicians initiated the survey, of which 704 (77%) completed the survey and were included in the analysis (Fig 1). Respondents originated from 19 LATAM countries, with the highest number practicing in Mexico (29%, n = 205), Brazil (11%, n = 76), and Chile (9%, n = 61). Most physicians were men (57%, n = 402), 31-40 years old (40%, n = 284), and practiced medical oncology (34%, n = 239). Table 1 shows physician demographics and workplace characteristics. Among respondents, 266 (38%) worked in a practice with more than 10 providers and more than half (58%, n = 410) worked full time. The most common practice settings were private clinics (58%, n = 405), state hospitals (43%, n = 304), and academic/university hospitals (40%, n = 280).

FIG 1.

Diagram of participants of the HOLA COVID-19 study.

TABLE 1.

Participant and Workplace Baseline Characteristics

Changes to Practice

At the time of the survey, 56% of physicians had cared for patients with COVID-19 (n = 397). Physicians noted that most of their practices (85%, n = 574) implemented screening questionnaires for COVID-19 symptoms prechemotherapy. Notably, 29% (n = 201) of physicians reported that their practice had implemented COVID-19 testing for all patients before initiating chemotherapy, whereas 32% (n = 228) implemented testing only for symptomatic patients, and 28% (n = 200) had no pre-=chemotherapy testing.

Most physicians (70%, n = 491) noted a decrease in the number of new patients evaluated during the pandemic when compared with before COVID-19 (pre-February 2020). The proportion of physicians who reported seeing less than five new patients per day increased from 40% (n = 279) before the pandemic to 73% (n = 513) during the pandemic (P < .001). Most physicians (72%, n = 505) reported fewer follow-up visits when compared with pre–COVID-19.

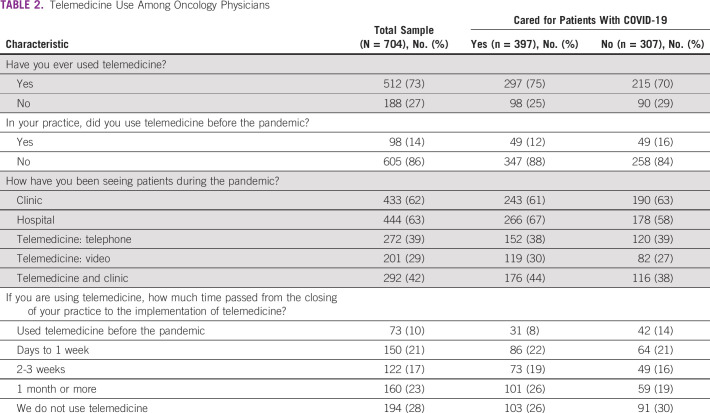

As shown in Table 2, physicians cared for patients in various settings, including hospitals, outpatient clinics, and telemedicine. Telemedicine was adopted broadly, with 73% (n = 512) of physicians using telemedicine in their oncology practice at the time of the survey, compared with only 14% (n = 98) before COVID-19 (P < .001). Physicians who cared for patients with COVID-19 were more likely to see patients in hospital settings than those who did not (67 v 58%; P = .019).

TABLE 2.

Telemedicine Use Among Oncology Physicians

Access to Resources and Specialty Care

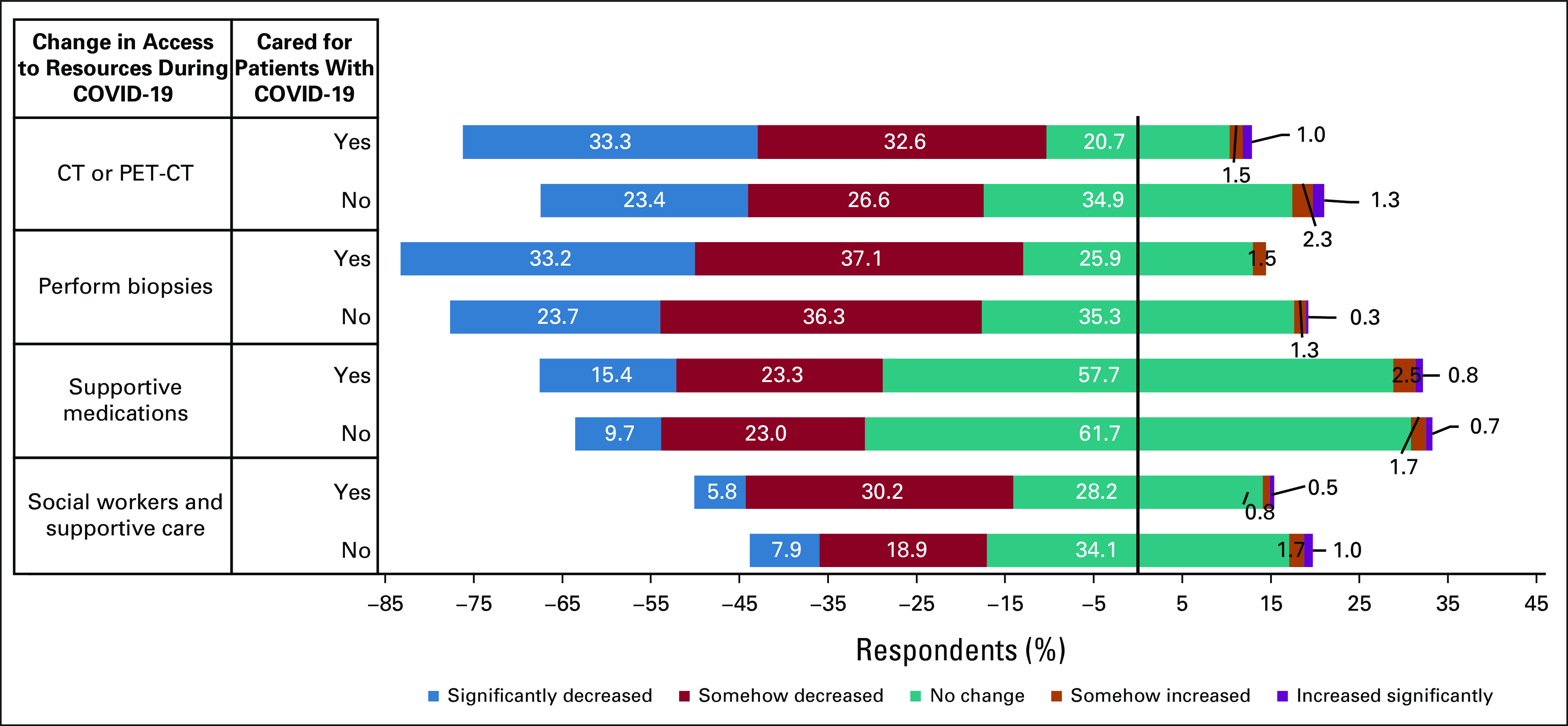

Oncology physicians reported significant changes in access to diagnostic resources (Fig 2). Eleven percent (n = 77) reported having no access to positron emission tomography-computed tomography (CT) or CT during the pandemic, and 59% (n = 413) noted that the availability of these diagnostic tests decreased somehow or significantly. Lower access to CT and positron emission tomography-CT was reported more frequently by physicians who cared for patients with COVID-19 than those who did not (P = .001). Similar differences were noted in access to biopsies, supportive medications (ie, antiemetics and growth factors), and social work and supportive care staff. Most physicians had access to COVID-19 testing for their patients (72%, n = 504). In a minority of cases, COVID-19 testing was limited to patients who could pay out-of-pocket costs (9%, n = 64).

FIG 2.

Self-reported changes in access to resources for the care of patients with access during the COVID-19 pandemic. Diverging stacked bars show answers to Likert scale questions evaluating change in access to resources (eg, CT or PET-CT, biopsies, supportive medications, or social workers) during the COVID-19 pandemic stratified by providers' answer (yes on top v no below) to the question “Have you taken care of cancer patients with COVID-19 infection?” Neutral answers (no change) are centered in the x-axis at zero. CT, computed tomography; PET, positron emission tomography.

Physicians also noted delays in access to specialty care. Most (65%, n = 456) reported delays in referrals to surgical oncology, irrespective of whether they took care of patients with COVID-19 (P = .051). However, 78% (n = 544) reported that their patients were evaluated by a surgical oncologist within 30 days of referral. Most physicians reported that cancer surgeries had been delayed (61%, n = 429), and 20% (n = 141) noted that surgeries had been canceled; 20% (n = 138) reported surgeries had been delayed for over a month. Regarding access to radiotherapy, that 49% (n = 343) of physicians reported delays in time to evaluation. Physicians who cared for patients with COVID-19 were more likely to report delays in radiotherapy assessments than those who did not care for patients with COVID-19 (55 v 44%; P = .004). Most physicians reported that their patients were evaluated by radiation oncology within 30 days of referral (73%, n = 515).

Changes to Clinical Practice

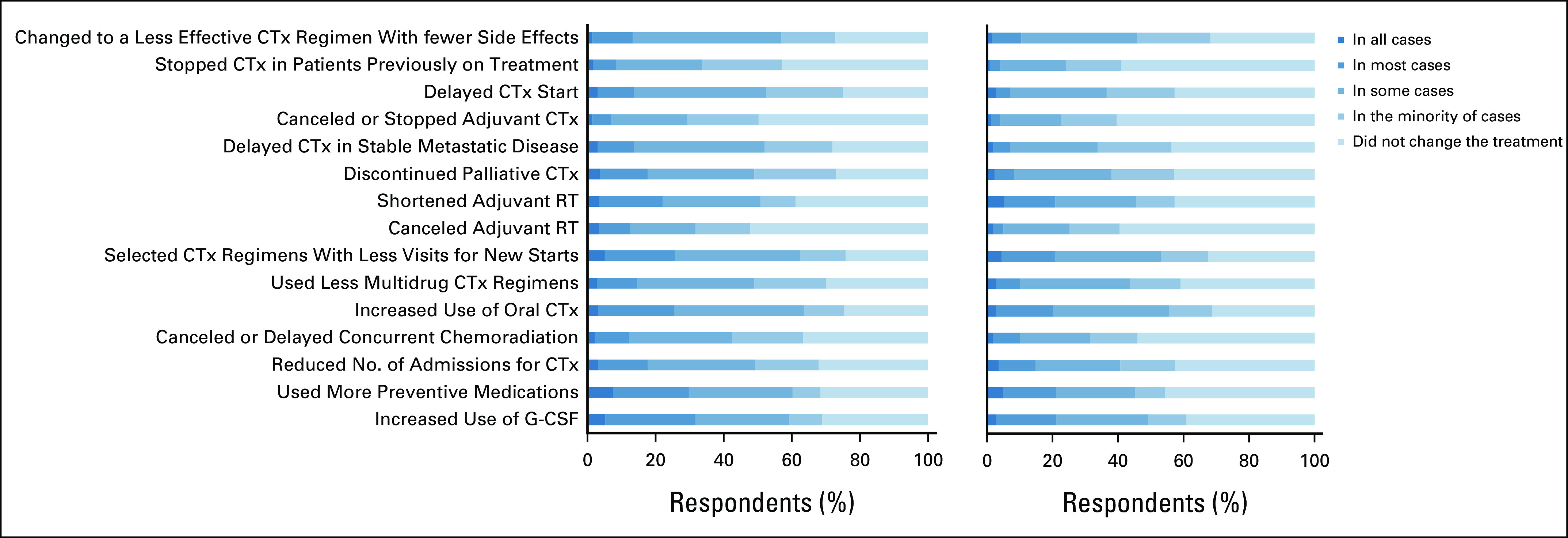

Oncology physicians noted significant changes in their clinical practice (ie, patient management), with 58% (n = 404) reporting that they had changed the type of chemotherapy or treatments they offered to patients, 47% (n = 330) reporting that they held or delayed chemotherapy because of the pandemic, and 38% (n = 269) had delayed or canceled adjuvant chemotherapy. Significant differences were observed in the proportion of physicians who delayed or held chemotherapy for ≥ 8 days between those who took care of patients with COVID-19 and those who did not (48 v 31%; P = .001). As shown in Figure 3, there are variability and differences in the frequency of self-reported changes to patient management between physicians who cared for patients with COVID-19 and those who did not. For example, physicians who cared for patients with COVID-19 were more likely to change chemotherapy regimens to decrease potential adverse events than physicians who did not care for patients with COVID-19 (57 v 46% changed chemotherapy in some, most, or all cases; P = .006). Similarly, physicians who cared for patients with COVID-19 were more likely to discontinue palliative chemotherapy (49 v 38% discontinued palliative chemotherapy in some, most, or all cases; P = .011) and to cancel or delay concurrent chemoradiation (42 v 31% in some, most, or all cases; P = .007). Overall, physicians reported increasing the use of oral chemotherapy and supportive care medications.

FIG 3.

Frequency distribution of self-reported changes to clinical practice: (A) caring for patients with COVID-19 versus (B) not caring for patients with COVID-19. Respondents who selected not applicable were excluded. CTx, chemotherapy; G-CSF, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor; RT, radiation therapy.

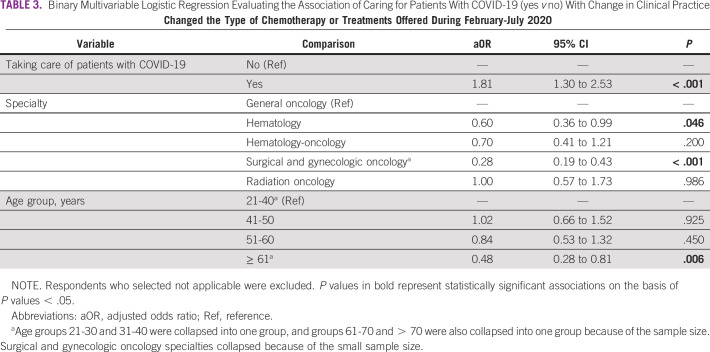

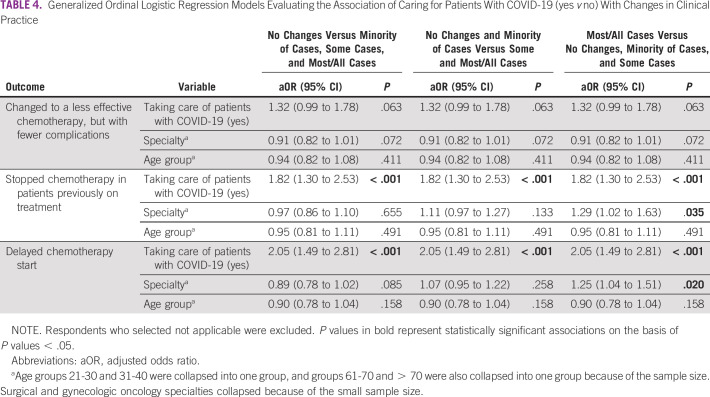

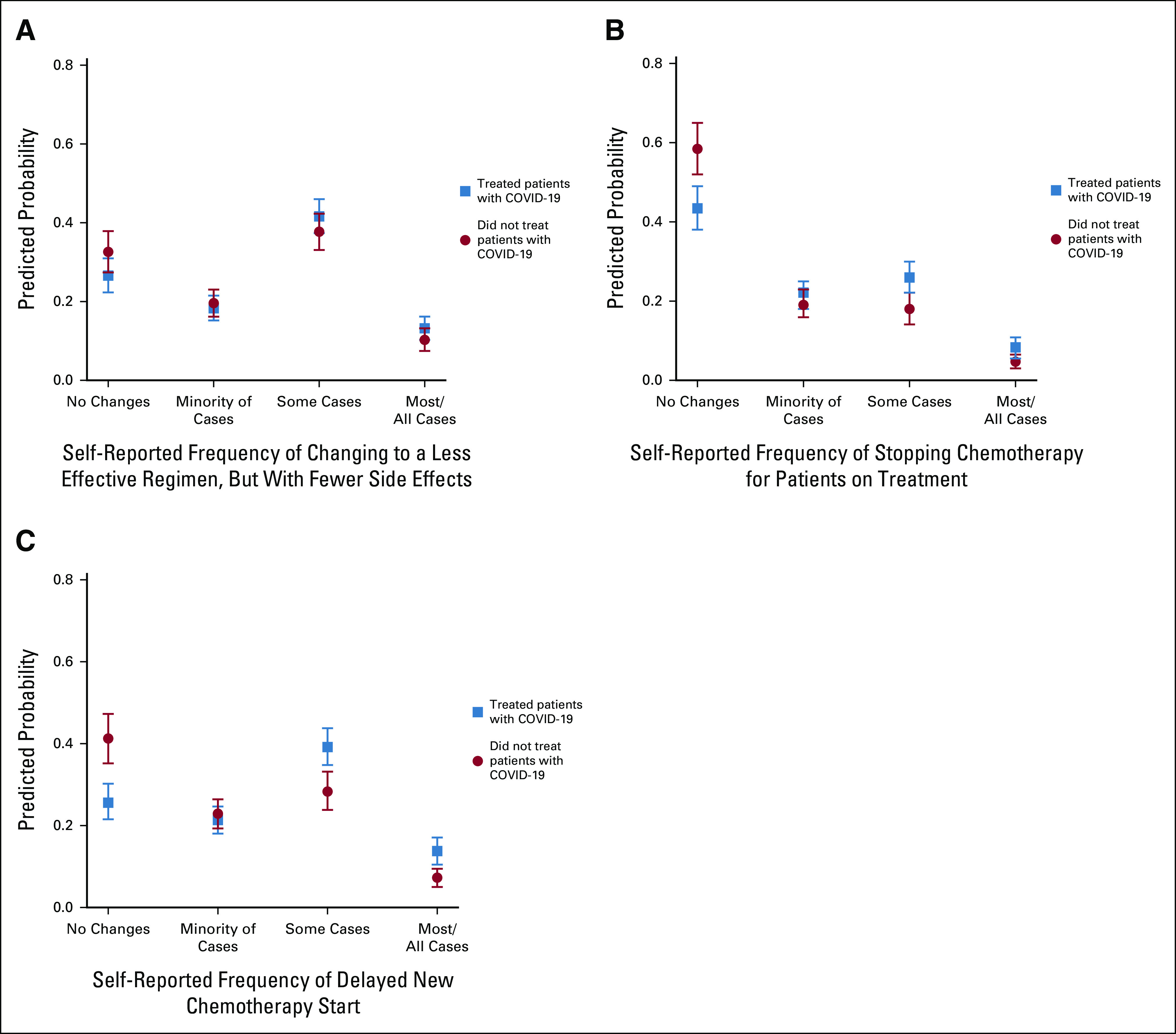

Multivariable logistic regression models evaluated the association of caring for patients with COVID-19 and key changes to clinical practice. As shown in Table 3, after adjusting for age and specialty, physicians who cared for patients with COVID-19 had higher odds of changing the type of chemotherapy or treatments offered to their patients (adjusted odds ratio 1.81; 95% CI, 1.30 to 2.53). We observed significant differences in self-reported changes of type of chemotherapy among specialties, with hematologists and surgical specialists (surgical oncologists and gynecologic oncologists) having lower odds of changing chemotherapy. Older physician age was associated with lower odds of changing chemotherapy in the adjusted model. In Table 4, ordinal regression models explore the associations of caring for patients with COVID-19 and secondary outcomes of interest. Physicians who cared for patients with COVID-19 tended to have higher odds of reporting that they had stopped chemotherapy in patients previously on treatment and delayed chemotherapy starts. As shown in Figure 4, the probability of reporting having stopped or delayed chemotherapy in some or most/all cases was highest among those who cared for patients with COVID-19.

TABLE 3.

Binary Multivariable Logistic Regression Evaluating the Association of Caring for Patients With COVID-19 (yes v no) With Change in Clinical Practice

TABLE 4.

Generalized Ordinal Logistic Regression Models Evaluating the Association of Caring for Patients With COVID-19 (yes v no) With Changes in Clinical Practice

FIG 4.

Predicted probabilities and 95% CIs for the four categories of self-reported frequency to changes to clinical practice, by caring for patients with COVID-19 (yes v no), on the basis of the generalized ordinal logistic regression. (A), (B) Self-reported frequency to changes to clinical practice when asked “Please choose the proportion of your practice that has been affected by the following changes since March 2020 compared to last year.” Among the proposed options, the most clinically relevant are shown: (A) change to a less effective regimen, but with fewer complications or side effects, (B) stop giving chemotherapy to the patients who were already on treatment, and (C) delay the start of chemotherapy. Reported frequencies are based on Likert scale options: in all cases, in most cases, in some cases, in the minority of cases, no changes, and not applicable. Because of the small sample size across categories, in all cases and most cases were collapsed into one category. Respondents who selected not applicable are excluded.

DISCUSSION

The results of HOLA COVID-19 highlight the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on oncology practices across LATAM. Among a large sample of oncology physicians, we found that a significant proportion directly participated in the care of patients with COVID-19. Interestingly, physicians who took care of patients with COVID-19 were more likely to change their patterns of cancer care and to modify treatments than those who did not. In addition, most physicians adapted their clinical practice to provide care for patients via telemedicine, demonstrating that this strategy might be useful in resource-limited settings like LATAM. Worryingly, most participants reported seeing a significantly lower volume of new patients and follow-up visits during the pandemic.

Patients with cancer have a significantly higher risk of acquiring COVID-19 and worse outcomes, including increased mortality and severe illness requiring intensive care unit admission.18,19 Within this vulnerable group, older age, belonging to socially disadvantaged populations (eg, racial/ethnic minorities and people living in poverty), having poor performance status, and having active cancer are associated with worse outcomes, specifically increased mortality.19,20 The vulnerability of patients with cancer to COVID-19, compounded with overwhelmed health care systems, has led oncologists to make modifications to their practices on a case-by-case basis, hoping to minimize the risk of exposing patients with cancer to COVID-19. In our study, we observed important modifications in practice patterns, with more than half of the respondents reporting changing treatment regimens offered to patients. Changes in intensity and length of therapy were used to avoid potential adverse events and to decrease patient contact with health care settings, limiting potential exposures to COVID-19. Although in some cases, modifying, omitting, delaying, or shortening treatment regimens may be appropriate, in others, this might have deleterious impacts on survival or quality of life.21 Although we did not assess the specific changes in chemotherapy dosing or schedules made by oncology physicians in response to the pandemic, the fact that more than a third delayed or canceled adjuvant treatments shows that potentially curative treatments were interrupted, which could affect cancer outcomes in the region. This is also supported by the delays in surgical interventions and/or radiotherapy. Overall, our results provide evidence to the extent to which the global COVID-19 pandemic has created new challenges and amplified pre-existing barriers to the diagnosis, treatment, and supportive care of patients with cancer in LATAM.

Our study uniquely builds on previously published data showing changes and delays to cancer care across the world. In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, cancer centers have adopted restrictive visitation policies, mandated the use of personal protective equipment, implemented telemedicine, and separated patients with COVID-19 via established pathways.22 Survey studies of providers from cancer centers around the world reported significant alterations to care, with 44% of oncologic surgeries, 25% of chemotherapy sessions, and 14% of radiotherapy appointments being canceled or delayed.23 Medical oncologists reported using less intravenous agents, such as chemotherapy and immunotherapy, and the majority were less likely to recommend second- or third-line therapies to patients with metastatic disease.24 During the pandemic, oncologists considered factors such as patient's age, performance status, and comorbidities when choosing cancer-directed therapies.24 Internationally, more than half of cancer centers had reduced assistance for patients, which not only affected treatment but also led to reduced appointments with support care staff, such as psychologists, nutritionists, social workers, and educators.25 Our findings highlight that changes and delays in therapy and decreased access to diagnostics and supportive and specialty care are heightened by physicians' direct experience of caring for patients with COVID-19. This finding may reflect physician responses to their personal experience witnessing the effects of COVID-19 in ill patients and/or their response to working in overwhelmed health care systems.

Besides our study, little is known about the impact of COVID-19 on LATAM oncology practices. Data from LATAM radiation oncology practices showed that 80% of the practices described a reduction in patient volume.26 A survey of breast cancer specialists from LATAM countries reported that 42% of respondents worked in hospitals that were brought to a standstill during the pandemic.27 Similarly, an online survey of LATAM pediatric hematologist-oncologists found that although ongoing chemotherapies were maintained, a significant proportion of outpatient procedures, surgeries, radiotherapy, and stem-cell transplantations were delayed indefinitely.28 Furthermore, 60% of respondents reported a significant decrease in workforce availability because of COVID-19 infection or quarantine.28

Understanding the effects of COVID-19 on cancer care in developing regions of the world, where access to health care is limited, is essential to prepare both for the postpandemic recovery period and for future epidemic events. According to the United Nations Economic Commission for LATAM and the Caribbean, LATAM is the world region with highest income inequality, even prepandemic.29,30 These economic challenges are expected to worsen during the pandemic, leading to an increase in poverty, political instability, and long-lasting effects on the care of chronic diseases, such as cancer.31,32

Strengths of HOLA COVID-19 include a large sample size with respondents from most LATAM countries, a multimodal recruitment approach, and the fact that, since the link was privately shared, the survey was likely only answered by oncology physicians. Limitations of our study include its cross-sectional nature, which allows us to capture data at a single timepoint and makes us unable to establish longitudinal relationships between exposure and outcomes. In addition, as there is no centralized governing body that guides oncology care and education in LATAM, the total number of oncologists in the region is unknown. Given this limitation, we used snowball sampling via a multimodal approach to increase our recruitment reach. Snowball sampling inherently introduces limitations and bias, which include the inability to estimate the number of individuals reached, unknown probability of selection, which can limit generalizability, and differential recruitment as evidenced by the small number of participants from Brazil when compared with Mexico. Other weaknesses include potential selection bias since physicians who were affected the most by COVID-19 could have been more inclined to answer the survey. However, the fact that almost half of respondents had not directly cared for patients with COVID-19 shows that this might not be the case. In addition, since our recruitment was primarily performed electronically, most participants were young physicians. Finally, we did not capture changes in treatment on a case-by-case basis, and therefore, we cannot say whether modifications led to undertreatment and/or worse outcomes. Despite these limitations, we believe that our findings provide a thorough overview of practice changes in the region and reflect the challenges experienced by LATAM oncologists during COVID-19.

During the past year, COVID-19 has affected the care of patients with cancer and oncologic practices throughout the world. Our study provides evidence of the impact and effects of the pandemic on oncology practices in LATAM, where health care systems are fragmented and access to cancer care is limited. Although the reported practice changes may seem like a reasonable response to the health care crisis created by the pandemic, significant disruptions in cancer care delivery and worsening outcomes across the regions could occur in the coming years. We hope that our data can serve as a guide to develop strategies focused on rebuilding cancer care in LATAM and avoiding disruptions during future health care crises.

Ana I. Velazquez

Employment: J&J Innovations

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Portola Pharmaceuticals, Corbus Pharmaceuticals, Midatech Pharma

Jose Corona Cruz

Honoraria: AstraZeneca, Eisai, Roche

Consulting or Advisory Role: AstraZeneca

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: AstraZeneca

Raimundo Bezares

Consulting or Advisory Role: Microsules Bernabo Argentina

Speakers' Bureau: AstraZeneca Argentina

Omar Orlando Castillo Fernandez

Honoraria: Roche Pharma AG, AstraZeneca, Novartis, Pfizer

Consulting or Advisory Role: Janssen Oncology

Research Funding: Roche, Novartis

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Roche, Pfizer

Luis Corrales-Rodríguez

Consulting or Advisory Role: AstraZeneca, Roche, MSD Oncology, Pfizer

Speakers' Bureau: Roche, AstraZeneca, MSD Oncology

Research Funding: Roche

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Roche, AstraZeneca, MSD Oncology

Glenda Ramos

Consulting or Advisory Role: AstraZeneca

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Roche

Alba J. Kihn-Alarcón

Honoraria: Bayer

Speakers' Bureau: Eurofarma

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Servier, Abbott Laboratories, Eurofarma

Federico Losco

Honoraria: Raffo, Janssen Oncology, Merck Serono, MSD Oncology, Grupo Biotoscana, Pfizer

Consulting or Advisory Role: Roche, Raffo, MSD Oncology, Janssen Oncology

Speakers' Bureau: Raffo, Pfizer, Janssen Oncology, Merck Serono, Tecnofarma, MSD Oncology, Grupo Biotoscana

Research Funding: Raffo (Inst), AstraZeneca/Merck (Inst)

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Raffo, Pfizer

Jenny Lissette Castro

Honoraria: Roche, Bayer, Merck, Serono

Consulting or Advisory Role: Roche, Bayer

Speakers' Bureau: Roche, Bayer

Luis Ubillos

Honoraria: Tecnofarma, Fármaco Uruguayo

Consulting or Advisory Role: Tecnofarma, Roche, Fármaco Uruguayo

Speakers' Bureau: Tecnofarma, Roche

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: GlaxoSmithKline, Roche, Pfizer, AstraZeneca, Tecnofarma

Eduardo Richardet

Consulting or Advisory Role: Boehringer Ingelheim, AstraZeneca, Pfizer, Roche, Bristol Myers Squibb

Speakers' Bureau: Bristol Myers Squibb

Research Funding: Bristol Myers Squibb, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Janssen, Amgen, Astellas Pharma, Roche, Novartis/Pfizer

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Bristol Myers Squibb, Pfizer

Enrique Soto-Perez-de-Celis

This author is a member of the JCO Global Oncology Editorial Board. Journal policy recused the author from having any role in the peer review of this manuscript.

Research Funding: Roche

Narjust Duma

This author is a member of the JCO Global Oncology Editorial Board. Journal policy recused the author from having any role in the peer review of this manuscript.

Consulting or Advisory Role: AstraZeneca, Pfizer, NeoGenomics Laboratories, Janssen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb/Medarex, Merck

Speakers' Bureau: MJH Life Sciences

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

DISCLAIMER

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the National Cancer Institute, HIV/AIDS or cancer registries, or their contractors.

SUPPORT

A.I.V. was supported by the UCSF National Clinician Scholars Program and by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under award no. P30AG015272.

C.B.-R. and A.I.V. contributed equally to this work.

STUDY GROUPS

HOLA COVID-19 Study Group: Claudio Martin, Gonzalo Recondo, Clarissa Mathias, Priscila Goncalves, Gabriel Manfro, Lucia Richter, Andres F. Cardona, Lucia Viola, Bettina G. Müller, Pablo Munoz Schuffenegger, Elia Neninger, Brenner Sabando, Finlander Rosales, Maria Teresa Bourlon, Zuratzi Deneken, Cesar Samanez, Henry L. Gomez.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and Design: Carolina Bernabe-Ramirez, Ana I. Velazquez, Coral Olazagasti, Jesus Anampa, Luis Corrales-Rodríguez, Enrique Soto-Perez-de-Celis, Narjust Duma

Provision of study material or patients: Ana I. Velazquez, Jose Corona Cruz, Evelin Mena, Alvaro Menendez, Raimundo Bezares, Omar Orlando Castillo Fernandez, Ximena Bruno, Gerardo Umanzor, Federico Losco, Eduardo Richardet, Enrique Soto-Perez-de-Celis

Collection and assembly of data: Ana I. Velazquez, Coral Olazagasti, Cristiane Decat Bergerot, Paulo Gustavo Bergerot, Jose Corona Cruz, Ivy Riano, Christina Adaniel, Francisca Ramirez, Jesus Anampa, Carmen Cajina, Evelin Mena, Elias Gracia, Alvaro Menendez, Henry Idrovo, Raimundo Bezares, Omar Orlando Castillo Fernandez, Liseth Duque, Glenda Ramos, Alba J. Kihn-Alarcón, Ilana Schlam, Ximena Bruno, Gerardo Umanzor, Jenny Lissette Castro, Federico Losco, Luis Ubillos, Eduardo Richardet, Enrique Soto-Perez-de-Celis, Narjust Duma

Data analysis and interpretation: Ana I. Velazquez, Cristiane Decat Bergerot, Paulo Gustavo Bergerot, Jesus Anampa, Alvaro Menendez, Gerardo Umanzor, Enrique Soto-Perez-de-Celis, Narjust Duma

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated unless otherwise noted. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/go/authors/author-center.

Open Payments is a public database containing information reported by companies about payments made to US-licensed physicians (Open Payments).

Ana I. Velazquez

Employment: J&J Innovations

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Portola Pharmaceuticals, Corbus Pharmaceuticals, Midatech Pharma

Jose Corona Cruz

Honoraria: AstraZeneca, Eisai, Roche

Consulting or Advisory Role: AstraZeneca

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: AstraZeneca

Raimundo Bezares

Consulting or Advisory Role: Microsules Bernabo Argentina

Speakers' Bureau: AstraZeneca Argentina

Omar Orlando Castillo Fernandez

Honoraria: Roche Pharma AG, AstraZeneca, Novartis, Pfizer

Consulting or Advisory Role: Janssen Oncology

Research Funding: Roche, Novartis

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Roche, Pfizer

Luis Corrales-Rodríguez

Consulting or Advisory Role: AstraZeneca, Roche, MSD Oncology, Pfizer

Speakers' Bureau: Roche, AstraZeneca, MSD Oncology

Research Funding: Roche

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Roche, AstraZeneca, MSD Oncology

Glenda Ramos

Consulting or Advisory Role: AstraZeneca

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Roche

Alba J. Kihn-Alarcón

Honoraria: Bayer

Speakers' Bureau: Eurofarma

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Servier, Abbott Laboratories, Eurofarma

Federico Losco

Honoraria: Raffo, Janssen Oncology, Merck Serono, MSD Oncology, Grupo Biotoscana, Pfizer

Consulting or Advisory Role: Roche, Raffo, MSD Oncology, Janssen Oncology

Speakers' Bureau: Raffo, Pfizer, Janssen Oncology, Merck Serono, Tecnofarma, MSD Oncology, Grupo Biotoscana

Research Funding: Raffo (Inst), AstraZeneca/Merck (Inst)

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Raffo, Pfizer

Jenny Lissette Castro

Honoraria: Roche, Bayer, Merck, Serono

Consulting or Advisory Role: Roche, Bayer

Speakers' Bureau: Roche, Bayer

Luis Ubillos

Honoraria: Tecnofarma, Fármaco Uruguayo

Consulting or Advisory Role: Tecnofarma, Roche, Fármaco Uruguayo

Speakers' Bureau: Tecnofarma, Roche

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: GlaxoSmithKline, Roche, Pfizer, AstraZeneca, Tecnofarma

Eduardo Richardet

Consulting or Advisory Role: Boehringer Ingelheim, AstraZeneca, Pfizer, Roche, Bristol Myers Squibb

Speakers' Bureau: Bristol Myers Squibb

Research Funding: Bristol Myers Squibb, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Janssen, Amgen, Astellas Pharma, Roche, Novartis/Pfizer

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Bristol Myers Squibb, Pfizer

Enrique Soto-Perez-de-Celis

This author is a member of the JCO Global Oncology Editorial Board. Journal policy recused the author from having any role in the peer review of this manuscript.

Research Funding: Roche

Narjust Duma

This author is a member of the JCO Global Oncology Editorial Board. Journal policy recused the author from having any role in the peer review of this manuscript.

Consulting or Advisory Role: AstraZeneca, Pfizer, NeoGenomics Laboratories, Janssen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb/Medarex, Merck

Speakers' Bureau: MJH Life Sciences

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center . COVID-19 Map. Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center; 2020. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chopra V, Toner E, Waldhorn R, et al. How should U.S. hospitals prepare for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)? Ann Intern Med 172621–6222020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Czeisler MÉ, Marynak K, Clarke KEN, et al. Delay or avoidance of medical care because of COVID-19–related concerns—United States MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 691250–12572020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hanna TP, Evans GA, Booth CM.Cancer, COVID-19 and the precautionary principle: Prioritizing treatment during a global pandemic Nat Rev Clin Oncol 17268–2702020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lin DD, Meghal T, Murthy P, et al. Chemotherapy treatment modifications during the COVID-19 outbreak at a community cancer center in New York City JCO Glob Oncol 61298–13052020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wu JT-Y, Kwon DH, Glover MJ, et al. Changes in cancer management due to COVID-19 illness in patients with cancer in Northern California JCO Oncol Pract 17e377–e3852020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bakouny Z, Paciotti M, Schmidt AL, et al. Cancer screening tests and cancer diagnoses during the COVID-19 pandemic JAMA Oncol 7458–4602021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maringe C, Spicer J, Morris M, et al. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on cancer deaths due to delays in diagnosis in England, UK: A national, population-based, modelling study Lancet Oncol 211023–10342020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.American Society of Clinical Oncology . ASCO Special Report: A Guide to Cancer Care Delivery During the COVID-19 Pandemic. 2020. https://www.asco.org/sites/new-www.asco.org/files/content-files/2020-ASCO-Guide-Cancer-COVID19.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 10.ESMO . Cancer Patient Management During the COVID-19 Pandemic. https://www.esmo.org/guidelines/cancer-patient-management-during-the-covid-19-pandemic [Google Scholar]

- 11.COVID-19 Recommendations and Information—American Society for Radiation Oncology (ASTRO) ASTRO; https://www.astro.org/Daily-Practice/COVID-19-Recommendations-and-Information/Clinical-Guidance [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ferlay J, Ervik M, Lam F, et al. Latin America and the Caribbean: Fact Sheets. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries CA Cancer J Clin 71209–2492021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Duma N, Moraes FY.Oncology training in Latin America: Are we ready for 2040? Lancet Oncol 211267–12682020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sierra MS, Soerjomataram I, Antoni S, et al. Cancer patterns and trends in Central and South America Cancer Epidemiol 44S23–S422016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Williams R.Generalized ordered logit/partial proportional odds models for ordinal dependent variables Stata J 658–822006 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Williams R.Understanding and interpreting generalized ordered logit models J Math Sociol 407–202016 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dai M, Liu D, Liu M, et al. Patients with cancer appear more vulnerable to SARS-CoV-2: A multicenter study during the COVID-19 outbreak Cancer Discov 10783–7912020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang Q, Berger NA, Xu R.Analyses of risk, racial disparity, and outcomes among US patients with cancer and COVID-19 infection JAMA Oncol 7220–2272021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kuderer NM, Choueiri TK, Shah DP, et al. Clinical impact of COVID-19 on patients with cancer (CCC19): A cohort study Lancet 3951907–19182020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schrag D, Hershman DL, Basch E.Oncology practice during the COVID-19 pandemic JAMA 3232005–20062020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Curigliano G, Banerjee S, Cervantes A, et al. Managing cancer patients during the COVID-19 pandemic: An ESMO multidisciplinary expert consensus Ann Oncol 311320–13352020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Onesti CE, Tagliamento M, Curigliano G, et al. Expected medium- and long-term impact of the COVID-19 outbreak in oncology JCO Glob Oncol 7162–1722021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ürün Y, Hussain SA, Bakouny Z, et al. Survey of the impact of COVID-19 on oncologists' decision making in cancer JCO Glob Oncol 61248–12572020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jazieh AR, Akbulut H, Curigliano G, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on cancer care: A global collaborative study JCO Glob Oncol 61428–14382020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martinez D, Sarria GJ, Wakefield D, et al. COVID's impact on radiation oncology: A Latin American survey study Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 108374–3782020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Luis Pendola G, Elizalde R, Vargas PS, et al. Management of non-invasive tumours, benign tumours and breast cancer during the COVID-19 pandemic: Recommendations based on a Latin American survey. Ecancermedicalscience. 2020;14:1115. doi: 10.3332/ecancer.2020.1115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vasquez L, Sampor C, Villanueva G, et al. Early impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on paediatric cancer care in Latin America Lancet Oncol 21753–7552020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC): Social Panorama of Latin America, 2020. Santiago, Chile: 2021. https://www.cepal.org/sites/default/files/publication/files/46688/S2100149_en.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sullivan MP, Beittel JS, Meyer PJ, et al. Latin America and the Caribbean: Impact of COVID-19. Congressional Research Service; https://fas.org/sgp/crs/row/IF11581.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cottani J. The Effects of Covid-19 on Latin America's Economy. Center for Strategic and International Studies; https://www.csis.org/analysis/effects-covid-19-latin-americas-economy [Google Scholar]

- 32.Garcia PJ, Alarcón A, Bayer A, et al. COVID-19 response in Latin America Am J Trop Med Hyg 1031765–17722020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]