Abstract

Introduction:

This study aimed 1) to identify underlying heterogeneous patterns of bully-victim; 2) to examine whether the different types of child maltreatment predict the patterns of bully-victim; and 3) to investigate the association between patterns of bully-victim and adolescent psychosocial problems (depression, trouble at school, and substance use).

Methods:

This study included a sample of 1139 (48.7% girls, 53.4% Black) drawn from the Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study. Children’s self-reported bullying victimization at age 9 was used using the Panel Study of Income Dynamics Child Development Supplement III. Teacher’s reported bullying perpetration at age 9 was used using Social Skills Rating System. Child maltreatment types were assessed at age 5 using the Parent-Child Conflict Tactics Scale Coding. At age 15, adolescent depression was measured using modified Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; trouble at school was measured using modified Add Health In-School Questionnaire; and self-reported substance use was used.

Results:

Latent class analysis produced four classes: bully-victim (19.8%), victim (16.3%), no bully-victim (38.9%), and bully (24.9%). Individuals who have been neglected are more likely to be in the victim class compared to all other classes. Physical abuse to be at heightened risk of involvement in the bully-victim, compared to victim class. Additionally, individuals in the victim group are greater risk for depression, problems at school, and alcohol, as compared to those in the other classes.

Conclusions:

This study augments the knowledge base on bully/victim, child maltreatment, and behavioral health outcomes and elucidates several suggestions for research and policy.

Keywords: Bullying, Peer victimization, Peer aggression, Child maltreatment, Adolescent psychosocial problems, Adolescence

1. Introduction

According to a recent nationally representative survey, the rate of bullying victimization was 23% and the rate of bullying perpetration was 6% among U.S. children and adolescents aged 6–17 years (Lebrun-Harris, Sherman, Limber, Miller, & Edgerton, 2019). Bullying—either victimization or perpetration experiences in childhood—has been recognized as a trigger to developing maladaptive behaviors. Bullying victimization had detrimental effects on psychological health in later life, including depression and suicidality (Barzilay et al., 2017; Takizawa, Maughan, & Arseneault, 2014; Ttofi, Ttofi, Farrington, Lösel, & Loeber, 2011). Similarly, bullying perpetration reported behavioral health issues, such as subsequent violent behavior, binge drinking, and sexual violence perpetration (Espelage, Basile, & Hamburger, 2012; Farrington, Loeber, Stallings, & Ttofi, 2011; Hemphill et al., 2011), along with psychological distress (Klomek, Sourander, & Gould, 2010). Given the deleterious consequences of bullying, prior research has strived to understand the patterns of bullying and their consequences, but few studies have examined them within the context of child maltreatment. This is specifically a glaring gap in the research because bullying has been identified as a common outcome of child maltreatment (Hong, Espelage, Grogan-Kaylor, & Allen-Meares, 2012; Wolfe, Crooks, Chiodo, & Jaffe, 2009). Understanding of child maltreatment and its association with bullying patterns would offer meaningful guidelines for practice by suggesting specific points for interventions and treatments.

1.1. Patterns of bullying

Bullying refers to intentional, repetitive, and aggressive behaviors among school aged children in which a power imbalance exists between victims and perpetrators (Olweus, 1994; Rettew & Pawlowski, 2016). Individuals either try to obtain or are deprived of power in peer relationships determine the role in bullying such as perpetrator, victim, or both. Social capital theory helps to explain diverse patterns of bullying by addressing different functioning and dynamics of social groups due to interpersonal relationships (Evans & Smokowski, 2015). According to the social capital theory, victims have minimal social capital, which hinders them to gain high social status, whereas bullies acquire and expand their social capital by relegating peers with low social status. Due to the nature of social capital that could be wavering, individuals can be involved in both bully and victim experiences. Those who have both experiences tend to find weaker peers and mimic the perpetrators’ behaviors in order to obtain social capital and end their victimization.

Informed by social capital theory, previous bullying studies have demonstrated children and adolescents’ bullying experiences using the variable-centered approach. However, the variable-centered approach does not capture the variability within and across subgroups of bullying (Giang & Graham, 2008; Turns & Sibley, 2018). This, in turn, obscures an understanding of the complexity of bullying patterns. In addition, prior research using the variable-centered approach was limited because these studies used arbitrary cutoff scores, such as mean, median, or standard deviation (Jansen et al., 2012; Solberg & Olweus, 2003). A person-centered approach such as latent class analysis (LCA), on the other hand, is an effective method to understand heterogeneity in bullying involvement experiences (etterncourt, Farrell, Liu, and Sullivan, 2013).

Building upon the strength of person-centered approach, a growing body of research has used the person-centered approach to identify distinct patterns and subgroups of bullying behaviors. Betterncourt et al. (2013) and Lovegrove, Henry, and Slater (2012) examined the patterns of bullying using perpetration and victimization indicators and found four distinct patterns: victim, bully, bully-victim, and non-involved. Both the victim and non-involved patterns had low levels of aggression and perpetration experiences, although the victim pattern had high levels of victimization experiences. The other two groups, bully and bully-victim patterns, had high levels of perpetration and aggression, while only the bully pattern reported low levels of victim experiences. Similarly, Giang and Graham (2008) examined the bullying subgroups and identified more specific patterns: five classes of bullying involvement (i.e., socially adjusted, victims, aggressors, highly-victimized aggressive-victims, and highly-aggressive aggressive victims). However, Goldweber, Waasdorp, and Bradshaw (2013) identified three patterns: low involvement, victim, and bully-victim. Although these studies have significant implications by describing heterogeneous patterns of bullying adapting both victimization and perpetration, their samples were focused on general sample in adolescence.

Bullying is most common in elementary school-aged children (Jansen et al., 2012). In order to develop interventions that target these age groups and mitigate negative developmental problems, a better understanding of bullying in middle childhood is necessary. Only two empirical studies, to our knowledge, have investigated the bullying patterns in middle childhood. Williford and colleagues (2011) explored the bullying patterns at grade 4th, 5th, and 6th and the bullying transition from late elementary school to middle school. They revealed the 4 patterns (i.e., aggressor, victim, aggressor-victim, and uninvolved). Using 3th, 4th, and 5th grade students, Moses and Williford (2017) also examined the bullying patterns. However, they failed to disentangle the patterns of bullying by taking into account only victimization separately despite bullying victimization and perpetration are not mutually exclusive, involving both forms of bullying simultaneously (Solberg & Olweus, 2003). In addition, the study samples for both were public school students in urban setting and did not analyze the relationship between traumatic experiences (e.g., child maltreatment) and bullying. Child maltreatment experiences have frequently identified as a strong risk factor for problematic peer relationships among at-risk of maltreatment populations (Alto, Handley, Rogosch, Cicchetti, & Toth, 2018; O’Hara, 2020; Wang et al., 2020; Yoon, 2020). Thus, more research on bullying patterns in middle childhood within the context of child maltreatment is needed.

1.2. Child maltreatment types and bullying

The developmental psychopathology perspective explains a diverse range of functioning throughout developmental periods and emphasizes the consequences of early adverse experiences (Cicchetti & Rogosch, 1996; Toth & Cicchetti, 2013). In line with the perspective, several empirical studies have identified that child maltreatment is associated with bullying involvement in both victimization (Bowes et al., 2009; O’Hara, 2020; Yoon, Yoon, Park, & Yoon, 2018) and perpetration (Bowes et al., 2009; Hsieh et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020). Although previous research has reported the strong association between all types of child maltreatment and bullying, findings have been mixed across studies depending on either type of child maltreatment or the form of bullying (Cunningham et al., 2019; Lo et al., 2021). For example, Nicholson, Chen, and Huang (2018) examined the effects of physical abuse and neglect on bullying victimization, and showed that physically abused children were more likely to be bullied by their peers, whereas neglected children were not associated with bullying victimization. However, Yoon et al. (2018) found no relationships between physical abuse and bullying victimization. In regard to perpetration experiences, Duke and colleagues (2010) examined the effects of adverse childhood experiences—including physical and sexual abuse experiences—on violence perpetration outcomes including bullying. They identified that both physical and sexual abuse experiences were at heightened risk for becoming bullying perpetrators. Similarly, Hsieh et al. (2020) examined the effects of diverse child maltreatment (i.e., physical neglect, psychological neglect, physical abuse, psychological abuse) on perpetration experiences, and found all types of abuse were associated with bullying perpetration experiences. Although previous studies have supported the influences of child maltreatment on bullying either victimization and perpetration, most studies have lumped the types of child maltreatment. Additionally, the studies that have specified the types of maltreatment were limited in that it included selective maltreatment types and bullying experiences.

1.3. Bullying and adolescent psychosocial problems

Substance use, trouble at school, and depressive symptoms are frequently associated with bullying. According to Tomczyk and colleagues (2015), youth who have committed bullying as perpetrators in middle childhood were more likely to use diverse types of substances in adolescence, whereas victimization experiences in middle childhood were not associated with adolescent substance use. Similarly, Gaete et al. (2017) identified that victimization was not associated with marijuana use, although all the other bullying experiences—regardless of victim or perpetration—were positively associated with alcohol and tobacco use. As for trouble at school, all types of bullying involvement were identified as risk factors for suspension or expulsion, feeling of not belonging at school, and to endorse cheating (Glew, Fan, Katon, Rivara, & Kernic, 2005). On the other hand, Stein and colleagues (2007) demonstrated that youth identified as bully-victim had no significant differences with school problems as compared to those identified as bully. But these same youth had higher rates of school problems than youth who were identified as victim and non-involved. In regard to depressive symptoms, previous studies have commonly reported that bully-victim and victims were more likely to have higher levels of depressive symptoms (Lovegrove & Cornell, 2014; O’Brennan, Bradshaw, & Sawyer, 2009; Özdemir & Stattin, 2011; Seeds, Harkness, & Quilty, 2010).

1.4. The current study

Previous studies have shown various combinations of bullying perpetration and victimization using general samples, however, scarce research has established whether the patterns of bullying differ by types of child maltreatment. In addition, the existing literature has produced inconsistent findings on the bullying pattern and its association with child maltreatment types and adolescent psychosocial problems, including substance use, problems at schools, and depressive symptoms. Thus, this study aimed: 1) to identify underlying heterogeneous patterns of bullying in a high-risk sample; 2) to examine whether the different types of child maltreatment predict the patterns of bullying; and 3) to investigate the association between patterns of bullying and adolescent psychosocial problems. Given that LCA is a data-driven exploratory approach, we did not hypothesize the number of bullying patterns. As for the second aim, we have hypothesized that each child maltreatment type would be associated differently with patterns of bullying, guided by developmental psychopathology perspective. Based on the extant literature, we broadly hypothesized the association between bullying patterns and adolescent psychosocial problems: Individuals who have experienced severe bullying would be associated with greater risk of adolescent psychosocial problems.

2. Method

2.1. Sample

Data were drawn from the Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study (FFCWS), which is a longitudinal study of families from 20 U.S. cities to investigate the context and consequences of fragile families (Reichman, Teitler, Garfinkel, & McLanahan, 2001). Using a stratified and multistage random sampling procedures, data were collected at hospitals between 1998 and 2000 at the time of the birth of a focal child. The FFCWS over-sampled non-martial births, resulting in a relatively disadvantaged sample of families. Follow-up surveys were conducted from children, caregivers, and teachers when the focal child was 1, 3, 5, 7, and 15 years by phone with select in-home assessments. For this study, we included a sample of 1139 children, their parents/caregiver, and teachers who completed the main study variables across all three time points at ages 5, 9, and 15 (48.7% female, 53.4% Black, 31.6% White, and 72.6% caregiver who completed more than high school degree, See table 1). Compared to baseline sample, this study sample is more likely to report having high school education on caregiver, χ2 (1) = 35.26, p < .001. In addition, children in this study are more likely to be picked on by peers, χ2 (1) = 5.60, p = .018 and left from the activities, χ2 (1) = 3.29, p = .070. but less likely to use cigarette, χ2 (1) = 5.38, p = .020 and marijuana, χ2 (1) = 21.94, p < .001. No other significant differences between baseline sample and the study sample were found.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics of Study Variables (N = 1139).

| M (SD) / % | |

|---|---|

| Gender (Female) | 48.7 |

| Race (Black) | 53.4 |

| Race (White) | 31.6 |

| Caregivers’ education (More than HS) | 72.6 |

| Bully | |

| 1. Fights with others | 45.0 |

| 2. Threatens or bullies others | 30.6 |

| 3. Argues with others | 60.8 |

| Victim | |

| 1. Kids picked on you or said mean things to you | 54.3 |

| 2. Kids hit you | 21.9 |

| 3. Kids take your things | 13.1 |

| 4. Kids purposely left you out of activities | 31.7 |

| Child maltreatment | |

| Physical assault | 80.2 |

| Psychological aggression | 94.0 |

| Neglect | 11.5 |

| Adolescent behavioral health | |

| Alcohol | 14.0 |

| Marijuana | 17.0 |

| Cigarette | 4.1 |

| Depressive symptoms | 8.03 (3.09) |

| Trouble at schools | 7.24 (1.93) |

Note. M = mean; SD = standard deviation; HS = high school.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Bullying

Both bullying perpetration and victimization were measured at age 9. For bullying perpetration, teachers were asked about three items of children’s aggressive behaviors toward peers (i.e., “fights with others;” “threatens or bullies others;” and “argues with others”) using Social Skills Rating System (Gresham & Elliot, 1990). For each item, three response options were used: 1 = never, 2 = sometimes, 3 = often, and 4 = very often. All three items were dichotomized as either (0) never or (1) at least one time. For bullying victimization, children reported their victim experiences with kids at school and neighborhoods during the last month, such as “picked on you or said mean things to you” and “taken your things, like your money or lunch, without asking.” using four items from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics, Child Development Supplement III. For each question, the response options were a five-point Likert scale, ranging from 0 = not once to 4 = every day. All these items were dichotomized: 0 = not at all and 1 = at least one experience. given the extreme distribution.

3.2.2. Child maltreatment

At age 5, primary caregivers were asked about their acts of physical assault, psychological aggression, and neglect in the past year using a modified version of the Parent-Child Conflict Tactics Scales Coding (Straus, Hamby, Finkelhor, Moore, & Runyan, 1998). Physical assault consisted of 5 items of physical punishment behaviors (e.g., “spanked child on the bottom with your bare hand,” “slapped child on hand, arm, or leg”). Psychological aggression consisted of 5 items of emotional painful verbal or symbolic acts towards child (e.g., “ever swore or cursed at child,” “shouted, yelled, or screamed at child”). Neglect consisted of 5 items of inadequate providing food or supervision (e.g., “left child home alone,” “was not able to make sure child got the food”). For each type of child maltreatment, eight response options were used, from “this has never happened,” to “more than 20 times”. For this study, dichotomized prevalence of each child maltreatment—the most frequently used score—is used, 0 = never happened and 1 = happened one or more times.

2.2.3. Adolescent psychosocial problems

Adolescent psychosocial problems (age 15) includes substance use (i. e., alcohol, cigarette, and marijuana), trouble at school, and depressive symptoms. For substance use, adolescent reported whether they have ever use alcohol, cigarette, and marijuana use. Each response option was dichotomous variable, 0 = no and 1 = yes. To assess trouble at school, a modified version of the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health Wave I In-School Questionnaire was used (McNeely, Nonnemaker, & Blum, 2002). Adolescents were asked about 4 items regarding their problems at schools such as paying attention and getting along with your teachers. For each item, three response options were used: 1 = never to 3 = often. A total scale of trouble at school was created by summing the responses, with higher scores indicating higher levels of trouble at school. Cronbach’s alpha for the trouble at schools in this sample is 0.63. Adolescent depressive symptoms were measured using a modified version of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (Radloff, 1977). Adolescent responded to the 5 questions regarding depressive symptomatology during the past 4 weeks: e.g., “I feel life is not worth living,” and “I feel depressed.” Each item was ranged from 1 = strongly agree to 4 = strongly disagree. The four items—except for “I feel happy”—were reverse-coded and a summative scale of depressive symptoms were created; higher scores indicate higher levels of depressive symptoms. Cronbach’s alpha for the depressive symptoms in this sample is 0.78.

2.2.4. Covariates

Gender (1 = female, 0 = male), race (1 = Black, 0 = non-Black), and primary caregiver’s education (0 = less than high school, 1 = high school degree or more) were included as control variables.

2.3. Statistical analyses

To address the three aims of the present study, a series of analyses (LCA, multinomial logistic regression, logistic regression, and ordinary least-squares multiple regressions) were employed using Mplus 8.3. Before conducting the LCA, descriptive statistics for all study variables and bivariate correlations between bullying related variables were produced using SPSS v. 25. LCA is a person-centered approach to identify distinct patterns using categorical indicators (Collins & Lanza, 2010). To determine the optimal number of classes, two to six class solutions were estimated iteratively (Aim 1). Several model fit indices including Akaike Information Criteria (AIC), Bayesian Information Criteria (BIC), the sample-size-adjusted BIC (ABIC), the Vuong Lo-Mendell-Rubin test (VLMR), and Entropy were used to determine the best fitting model, along with class size and interpretability. The model with the lower AIC, BIC, and ABIC indicates a better fit to the data (Collins & Lanza, 2010; Nylund, Bellmore, Nishina, & Graham, 2007). The significant p-value of VLMR yield whether the k class model improve the model fit, compared to the k-1 model (Nylund et al., 2007). The higher value of Entropy (range: 0–1) indicates better classification accuracy (Celeux & Soromenho, 1996). After the best LCA model was selected, multinomial logistic regression was conducted to examine whether the patterns of bullying differ by type of child maltreatment (Aim 2). In addition, multiple logistic regressions and ordinary least-squares multiple regressions were conducted to investigate the association between bullying patterns and adolescent psychosocial problems (Aim 3). To handle missing data, Full Information Maximum Likelihood estimation was used.

3. Results

3.1. Patterns of bullying

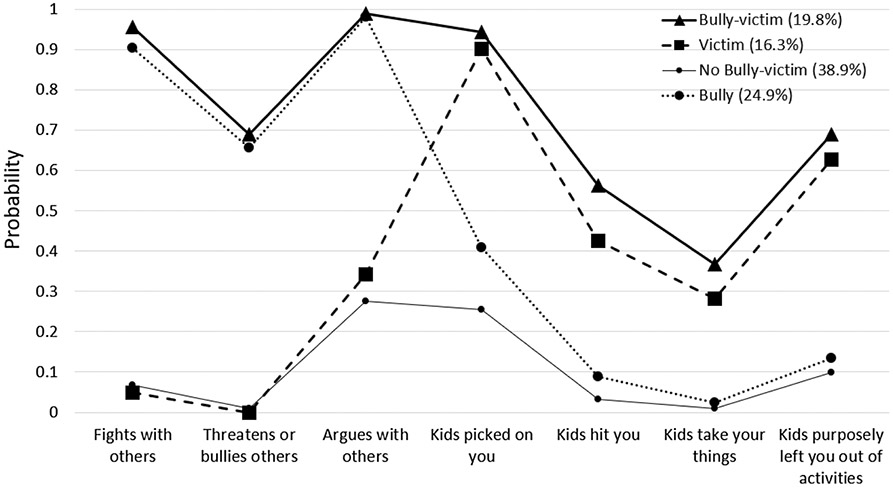

Table 2 shows bivariate correlations among study variables. Table 3 presents multiple model fit indices for each LCA model. The 4-class solution has the lowest value of AIC, BIC, and ABIC, suggesting that the 4-class solution was the best fit for these data. In addition, the p-value of VLMR indicated that the 4-class solution significantly improved the 3-class solution, whereas 5-class solution did not improve the 4-class solution. Thus, we have opted the 4-class solution. Fig. 1 describes a plot with item-probabilities for the 4-class solution. The first class, bully-victim (n = 226, 19.8%), suggested a pattern of high endorsement on both bullying perpetration and victimization items. The second class is named victim (n = 186, 16.3%) because this class comprised individuals who reported relatively low levels of perpetration, whereas item probabilities of victim were high. The third class, named no bully-victim (n = 443, 38.9%), reported low involvement in both bullying perpetration and victimization. The fourth class is named bully (n = 284, 24.9%). Individuals in this class reported high engagement in bullying perpetration, but low victimization.

Table 2.

Correlations between study variables (N = 1139).

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. B1 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||

| 2. B2 | 0.62*** | 1 | ||||||||||||||||

| 3. B3 | 0.61*** | 0.50*** | 1 | |||||||||||||||

| 4. V1 | 0.16*** | 0.13*** | 0.14*** | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| 5. V2 | 0.15*** | 0.16*** | 0.12*** | 0.32*** | 1 | |||||||||||||

| 6. V3 | 0.08** | 0.05 | 0.12*** | 0.25*** | 0.32*** | 1 | ||||||||||||

| 7. V4 | 0.10** | 0.08** | 0.08* | 0.36*** | 0.27*** | 0.27*** | 1 | |||||||||||

| 8. PA | 0.07* | 0.08* | 0.07* | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.08** | 1 | ||||||||||

| 9. PSY | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.02 | −0.02 | 0.01 | 0.39*** | 1 | |||||||||

| 10. NEG | −0.03 | 0.01 | −0.02 | 0.00 | −0.01 | −0.02 | 0.06 | 0.10** | 0.08** | 1 | ||||||||

| 11. ALC | −0.03 | −0.01 | −0.04 | 0.02 | −0.02 | −0.01 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.08** | 1 | |||||||

| 12. MAR | 0.11*** | 0.17*** | 0.10** | 0.06* | 0.05 | −0.01 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.09** | 0.09** | 0.41*** | 1 | ||||||

| 13. CIG | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.07* | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.08** | 0.06** | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.30*** | 0.31*** | 1 | |||||

| 14. DEP | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.08* | 0.08* | 0.09** | 0.14*** | 0.01 | −0.05 | 0.05 | 0.18*** | 0.12*** | 0.16*** | 1 | ||||

| 15. TS | 0.11*** | 0.11*** | 0.13*** | 0.14*** | 0.10** | 0.08** | 0.10** | 0.06* | 0.03 | 0.07* | 0.13*** | 0.13*** | 0.10*** | 0.26*** | 1 | |||

| 16. FEM | −0.09** | −0.09** | −0.07* | 0.04 | −0.11*** | 0.02 | 0.02 | −0.01 | −0.01 | 0.03 | −0.01 | −0.01 | −0.03 | 0.10** | −0.02 | 1 | ||

| 17. Black | 0.20*** | 0.22*** | 0.24*** | 0.08* | 0.09** | 0.07* | 0.03 | 0.16*** | 0.07* | 0.05 | −0.06* | 0.08** | −0.07* | 0.02 | 0.10** | −0.02 | 1 | |

| 18. EDU | −0.07* | −0.09** | −0.04 | 0.00 | −0.04 | −0.01 | 0.05 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −0.04 | −0.02 | −0.12*** | −0.04 | −0.08** | −0.11*** | 0.01 | −0.05 | 1 |

Note. Note. B bully; V victim; PA physical assault; PSY psychological aggression; NEG neglect; ALC alcohol use; MAR marijuana use; CIG cigarette use; DEP depression; TS trouble at schools; FEM female; EDU caregiver’s education.

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001

Table 3.

Model fit indices with 2 to 6 latent classes.

| Class | AIC | BIC | ABIC | Entropy | VLMR | Smallest class % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 8477.29 | 8552.86 | 8505.21 | 0.855 | p < .001 | 45.1 |

| 3 | 8252.76 | 8368.63 | 8295.58 | 0.785 | p < .001 | 18.7 |

| 4 | 8087.86 | 8244.03 | 8145.57 | 0.748 | p < .001 | 16.3 |

| 5 | 8094.02 | 8290.50 | 8166.62 | 0.704 | p = .432 | 10.2 |

| 6 | 8097.39 | 8334.17 | 8184.89 | 0.722 | p = .223 | 5.0 |

Note. AIC = Akaike Information Criterion; BIC = Bayesian Information Criteria; ABIC = Sample-adjusted BIC; VLMR = Vuong-Lo-Mendell-Rubin.

Fig. 1.

Plot with item-probabilities for the 4-class solution.

3.2. Child maltreatment types and bullying patterns

Using multinomial logistic regression, the different effects of child maltreatment types on bullying patterns were found after controlling for gender, race, and caregiver’s education, χ2 = 85.68, p < .001 (Table 4). Compared to the bully-victim class, individuals who have been neglected had 1.86 times higher odds of being in the victim class (95% CI = 1.04–3.33, p = .036), while individuals who have been physically assaulted had lower odds of being in the victim class (OR = 0.55, 95% CI = 0.32–0.97, p = .039). Compared to the bully class, individuals who have been neglected had 2.06 times higher odds of being in the victim class (95% CI = 1.18–3.62, p = .011). Compared to the no bully-victim class, individuals who have been neglected had 1.75 times higher odds of being in the victim class (95% CI = 1.06–2.87, p = .028). As for the covariates, African American had lower odds of being in victim (OR = 0.44, 95% CI = 0.29–0.66, p < .001) and no bully-victim classes (OR = 0.40, 95% CI = 0.29–0.56, p < .001) compared to the bully-victim class. Individuals whose caregiver completed more than high school grades had higher odds of being in victim class, compared to bully-victim class (OR = 1.69, 95% CI = 1.07–2.66, p = .026). Female had 1.67 times higher odds of being in the victim (95% CI = 1.14–2.43, p = .008) and 1.64 times higher odds of being in the no bully-victim (95% CI = 1.21–2.23, p = .002) classes, compared to bully class. African American had lower odds of being in victim (OR = 0.47, 95% CI = 0.32–0.69, p < .001) and no bully-victim classes (OR = 0.42, 95% CI = 0.31–0.58, p < .001) compared to the bully class. Individuals whose caregiver completed more than high school grades had higher odds of being in victim class, compared to bully class (OR = 1.60, 95% CI = 1.03–2.49, p = .038).

Table 4.

Effects of Child Maltreatment Types on Bullying Classes, OR (95% CI).

| Reference group | Bully-victim vs. |

Bully vs. |

No Bully-victim vs. Victim |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Victim | No Bully-Victim | Bully | Victim | No Bully-Victim | ||

| Female | 1.36 (0.92–2.02) |

1.34 (0.96–1.85) |

0.82 (0.57–1.16) |

1.67

(1.14–2.43) |

1.64

(1.21–2.23) |

1.02 (0.72–1.44) |

| African American |

0.44

(0.29–0.66) |

0.40

(0.29–0.56) |

0.94 (0.65–1.37) |

0.47

(0.32–0.69) |

0.42

(0.31–0.58) |

1.10 (0.77–1.56) |

| Caregiver’s education |

1.69

(1.07–2.66) |

1.20 (0.84–1.72) |

1.05 (0.72–1.54) |

1.60

(1.03–2.49) |

1.14 (0.81–1.60) |

1.40 (0.83–2.12) |

| Physical assault |

0.55

(0.32–0.97) |

0.66 (0.41–1.08) |

0.68 (0.40–1.15) |

0.81 (0.49–1.34) |

0.97 (0.64–1.48) |

0.84 (0.54–1.31) |

| Psychological aggression | 1.24 (0.51–3.01) |

1.20 (0.57–2.55) |

1.99 (0.81–4.89) |

0.62 (0.25–1.34) |

0.60 (0.28–1.30) |

1.03 (0.50–2.15) |

| Neglect |

1.86

(1.04–3.33) |

1.07 (0.63–1.80) |

0.90 (0.51–1.60) |

2.06

(1.18–3.62) |

1.18 (0.71–1.96) |

1.75

(1.06–2.87) |

Note. The significant association is indicated as bold.

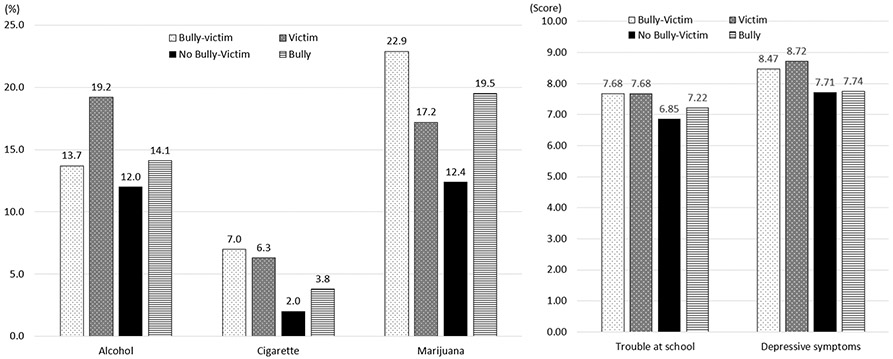

3.3. Bullying patterns and adolescent psychosocial problems

Fig. 2 shows the effects of the bullying patterns on adolescent psychosocial problems (i.e., substance use, trouble at schools, and depressive symptoms) after controlling for gender, race, and caregiver’s education. More individuals in the victim class (19.2%) drank alcohol than those in no bully-victim class (12.0%). As for cigarette use, more individuals in the bully-victim (7.0%) and victim (6.3%) classes smoked cigarette than those in the no bully-victim class (2.0%). In addition, more individuals in the bully-victim (22.9%) and bully (19.5%) classes smoked marijuana than those in the no bully-victim class (12.4%). In regard to trouble at school, individuals in the no bully-victim (M = 6.85, SE = 0.09) reported having less trouble at school compared to bully-victim (M = 7.68, SE = 0.13), victim (M = 7.68, SE = 0.14), and bully (M = 7.22, SE = 0.11) classes. Additionally, individuals in the bully class reported having less trouble at school compared to bully-victim and victim classes. As for depressive symptoms, individuals in the bully-victim (M = 8.47, SE = 0.20) and victim (M = 8.72, SE = 0.22) classes reported having more depressive symptoms than those in the no bully-victim class (M = 7.71, SE = 0.15) and bully class (M = 7.74, SE = 0.18). In regards to covariates, African American had lower odds of alcohol use (OR = 0.69, 95% CI = 0.49–0.97, p = .033). African American had lower odds of cigarette use (OR = 0.40, 95% CI = 0.21–0.75, p = .004). Individuals whose caregiver completed more than high school grades had lower odds of marijuana use (OR = 0.53, 95% CI = 0.38–0.74, p < .001).

Fig. 2.

Adolescent Behavioral Health by Latent Classes.

4. Discussion

This study was to identify the patterns of bullying among a high-risk sample. The study also aimed to advance the understanding of which specific types of child maltreatment predicted bullying patterns, and to determine what the associations were between bullying patterns and adolescent psychosocial outcomes. Our findings contribute to the existing research by identifying the distinct patterns of bullying in high risk sample. Overall, our findings with regard to empirical bullying classification (i.e., bully-victim, bully, victim, and no bully-victim) are in line with social capital theory explaining diverse patterns of bullying, and most previous studies suggesting four heterogeneous patterns of bullying (Betterncourt et al., 2013; Lovegrove et al., 2012; Williford, Brisson, Bender, Jenson, & Forrest-Bank, 2011).

As predicted by developmental psychopathology perspectives, the bullying patterns are differently influenced by child maltreatment types and show significant differences from previous research, providing new insights. Our findings suggest that individuals who have been neglected are more likely to be in the victim class compared to all other classes (i. e., bully, bully-victim, and no bully-victim). This is inconsistent with other studies, which suggest that neglect leads to aggressive behaviors (Logan-Greene & Jones, 2015). O’Hara (2020) found that children with a history of neglect were not at greater odds for bullying victimization, only children with physical assault reported victimization experiences. One explanation for these divergent findings is two-fold: first, previous studies tend to separate bullying and victimization as opposed to looking at the issue as a continuum, while this study incorporated both bullying and victimization. A second explanation lies in the behaviors of neglected children. Often these children have lower self-esteem and tend to internalize their issues (Juvonen & Graham, 2014; Trickett & McBride-Chang, 1995). Therefore, their ability to speak up and defend themselves may be compromised. Future research should continue to focus on the subtypes of bullying/victimization as it relates to neglect, with additional focus on the different subtypes of neglect (i.e., physical, psychological, environmental, or a combination). This level of specificity might lend itself to targeted inventions that focus on individual groups.

Interestingly, we identified physical assault to be at heightened risk of involvement in the bully-victim class, compared to the victim class. Prior research indicated that individuals who have been physically assaulted tend to externalize their behaviors through aggressive and disruptive means (Teisl & Cicchetti, 2008). To be specific, physically assaulted children may expand their social capital by expressing their aggression to other peers with low social status. They may also be victimized, however, by peers with high social status given their social and emotional problems. Future research should consider the mechanisms of how physical assault experiences lead to bully-victim experiences.

Regardless of having perpetration experiences, in general, individuals who have victim experiences are more likely to engage in psychosocial problems, such as using tobacco, exhibiting more trouble at school, and having higher depressive symptoms. As for substance use, the strong effects of bullying victimization are distinctly identified: individuals who have been victimized are more likely to use alcohol, even compared to bully-victim groups. These findings corroborate the findings presented in previous work that being a victim is a known risk factor for future substance use (Radliff, Wheaton, Robinson, & Morris, 2012; Tharp-Taylor et al., 2009; Valdebenito, Ttofi, & Eisner, 2015). We posit that youth are more likely to engage in substance use as a way to self-medicate. These youths need to reduce symptoms of stress, depression, and anxiety and therefore may use multiple substances and engage in risky behaviors as a way to cope. Although the overall effects of bullying patterns on alcohol and tobacco use are similar, while marijuana use differs from these other two substances: higher rates of marijuana use among the bully-victim and bully classes. This finding is similar to those of previous studies which reported that adolescents being bullied were less likely to engage in marijuana use (Priesman, Newman, & Ford, 2018). Perren and Alsaker (2006) showed that bullying victims tend to be less cooperative or sociable, and to have fewer friends. Considering that the most common source of marijuana for adolescents is their friends (King, Merianos, & Vidourek, 2016), those who are bullied may find it difficult to obtain marijuana. This finding can also be explained by the process of obtaining power from peers using marijuana. According to Tucker and colleagues (2014), using marijuana in adolescence may be a strategy to attain social status. In other words, individuals who bully others or have both bully and victim experiences may try to keep their status within their peer groups by using marijuana. Future research should examine how important it is to attain social status as a reason for using different types of substances.

Our study found that no bully-victim performed better in school than any form of bullying (i.e., victim, bully, or bully-victim): a finding consistent with what previous research has demonstrated (Menesini & Salmivalli, 2017; Nakamoto & Schwartz, 2009). What was unique in our results was that the bully class had less trouble at school compared to the bully-victim and victim classes. These findings may be due to the self-reports of trouble at schools. Given that individuals who bully others tend to exhibit low psychological distress (Lereya, Copeland, Zammit, & Wolke, 2015), they may consider themselves as “normal” at school. More studies are needed to examine the role of psychological distress in the association between performance at school and different types of bullying involvement in order to illuminate how different bullying involvement is associated with school life.

It was not surprising that individuals in the bully-victim and victim classes reported having more depressive symptoms than those in the no bully-victim class and bully class, as these are well documented outcomes (Garnefski & Kraaij, 2014). Although victimization is well known as a risk factor for internalizing problems including depression, these findings suggest a need for additional focus on the magnitude of a victim’s depression. Adolescent depression due to bullying victim experiences is associated with a higher risk for suicidal ideation and suicidality (Kodish et al., 2016). Given the grave consequences, future research should consider the relations of suicidality and depression among bully-victims and victims.

4.1. Strengths and limitations

There are noted limitations of this study. First, the measure of child maltreatment relied on parent reports as opposed to using state administrative data for verification. It is possible that there was under-reporting or a gap between child or child protective services report. Second, sexual abuse information at age 5 were not gathered in the FFCWS, which may differently affect the results of this study. Third, the bully-perpetration data came from teacher reports. There are many avenues research has taken to collect this information including self and peer reports. Ideally, there would be a way to validate the reports made by the teacher. The fourth limitation was the inability to account for the different bullying types. Because bullying has been the subject of research for over two decades, there has been some agreement on the subtypes of bullying (i.e., verbal, physical, and more recently, cyber bullying); however, our dataset was unable to account for this. In addition, the dichotomized bullying cannot capture the chronic or severity of bullying. A final limitation was the timeframe for when the adolescent’s behavior was measured. A large body of research has focused on adult outcomes of bullying/victimization, yet having six years between the event and outcome may not be enough time to fully account for future negative behaviors, particularly if the bullying/victimization began at a later age.

Despite these limitations, there are multiple strengths in this paper worth noting. First, this is the first study to examine the types of child maltreatment and their association with patterns of bullying using a large number of high-risk children over an extended period of time. Thus, we were able to capture behavior longitudinally. Multiple interventions have been developed for bullying concerns, yet there remain higher-risk groups that could benefit from targeted interventions. This study contributes to the literature by identifying the unique effects of child maltreatment types on bullying patterns, as well as the role of bullying on further adolescent psychosocial problems. In addition, this study used sophisticated analyses. As a person-centered approach, an LCA allowed us to identify the patterns of bullying accurately.

5. Conclusions and implications

Despite the results of our study, which augment the knowledge base on bully/victimization, child maltreatment, and psychosocial problems, it is important to note that the remaining questions can be considered in future studies. Although this study identified the similar patterns of bullying regardless of different measure and data sources, researchers should continue focusing on the association between the bullying patterns and traumatic experiences because our findings are more focused on the child maltreatment. Equally important is a continued focus on the long-term psychosocial problems of bully/victimization, particularly at specific stages. Extant research has considered bullying only in middle childhood, and its consequences only in adolescence. Future research may consider the longitudinal changes of bullying patterns during the developmental stages and their associations with adolescent psychosocial problems.

Our findings suggest that there is a level of risk for bullying/victimization among maltreated youth, which may influence their psychosocial problems. Although school-wide interventions are useful, their effectiveness is mixed and what specifically works within each program differs considerably. What is known is that longer, more intensive programs that involve parents and caregivers have some of the strongest effects (Menesini & Salmivalli, 2017). Thus, school administrators may benefit from offering these types of interventions for higher-risk youth. Child welfare practitioners need, ongoing training and to recognize of youth that may be in the bullying/victim categories. It is important to be aware that because these youths have a history of maltreatment, they are at higher risk for re-victimization. Child welfare practitioners additionally must forge collaborative relationships with school personnel, namely school social workers, to ensure coordinated planning and shared goal-setting that focuses both bullies and victims.

Funding

This manuscript uses data from the Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study (FFCWS), which is funded by Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), the National Opinion Research Center (NORC), and Mathmatia Policy Research. The collector of the original data, the funder, Princeton University’s Center for Research on Child Wellbeing (CRCW) and Center for Health and Wellbeing (CHW), as well as Columbia University’s the Columbia Population Research Center (CPRC) and the National Center for Children and Families (NCCF) bear no responsibility for the analyses or interpretations presented here. Dr. Shipe’s work was supported by a grant from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (T32 HD101390, Co-PIs: Jackson & Noll).

Footnotes

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Dalhee Yoon: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Stacey L. Shipe: Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing, Validation. Jiho Park: Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing, Validation. Miyoung Yoon: Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing, Validation.

References

- Alto M, Handley E, Rogosch F, Cicchetti D, & Toth S (2018). Maternal relationship quality and peer social acceptance as mediators between child maltreatment and adolescent depressive symptoms: Gender differences. Journal of Adolescence, 63, 19–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barzilay S, Brunstein Klomek A, Apter A, Carli V, Wasserman C, Hadlaczky G, … Wasserman D (2017). Bullying victimization and suicide ideation and behavior among adolescents in Europe: A 10-country study. Journal of Adolescent Health, 61 (2), 179–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betterncourt A, Farrell A, Liu W, & Sullivan T (2013). Stability and change in pattern of peer victimization and aggression during adolescence. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 42(4), 429–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowes L, Arseneault L, Maughan B, Taylor A, Caspi A, & Moffitt TE (2009). School, neighborhood, and family factors are associated with children’s bullying involvement: A nationally representative longitudinal study. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 48(5), 545–553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celeux G, & Soromenho G (1996). An entropy criterion for assessing the number of clusters in a mixture model. Journal of Classification, 13(2), 195–212. [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, & Rogosch FA (1996). Equifinality and multifinality in developmental psychopathology. Development and Psychopathology, 8(4), 597–600. [Google Scholar]

- Collins LM, & Lanza ST (2010). Latent class and latent transition analysis: With applications in the social behavioral, and health sciences. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham S, Goff C, Bagby RM, Stewart JG, Larocque C, Mazurka R, … Harkness KL (2019). Maternal-versus paternal-perpetrated maltreatment and risk for sexual and peer bullying revictimization in young women with depression. Child Abuse & Neglect, 89, 111–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duke NN, Pettingell SL, McMorris BJ, & Borowsky IW (2010). Adolescent violence perpetration: Associations with multiple types of adverse childhood experiences. Pediatrics, 125(4), e778–e786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espelage DL, Basile KC, & Hamburger ME (2012). Bullying perpetration and subsequent sexual violence perpetration among middle school students. Journal of Adolescent Health, 50(1), 60–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans CBR, & Smokowski PR (2016). Theoretical explanations for bullying in school: How ecological processes propagate perpetration and victimization. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 33(4), 365–375. [Google Scholar]

- Farrington DP, Loeber R, Stallings R, & Ttofi MM (2011). Bullying perpetration and victimization as predictors of delinquency and depression in the Pittsburgh Youth Study. Journal of Aggression, Conflict and Peace Research, 3(2), 74–81. [Google Scholar]

- Garnefski N, & Kraaij V (2014). Bully victimization and emotional problems in adolescents: Moderation by specific cognitive coping strategies? Journal of Adolescence, 37(7), 1153–1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaete J, Tornero B, Valenzuela D, Rojas-Barahona CA, Salmivalli C, Valenzuela E, & Araya R (2017). Substance use among adolescents involved in bullying: A cross-sectional multilevel study. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giang MT, & Graham S (2008). Using latent class analysis to identify aggressors and victims of peer harassment. Aggressive Behavior, 34(2), 203–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glew GM, Fan MY, Katon W, Rivara FP, & Kernic MA (2005). Bullying, psychosocial adjustment, and academic performance in elementary school. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 159(11), 1026–1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldweber A, Waasdorp TE, & Bradshaw CP (2013). Examining associations between race, urbanicity, and patterns of bullying involvement. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 42(2), 206–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gresham FM, & Elliot SN (1990). Social skills rating system manual. Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service. [Google Scholar]

- Hemphill SA, Kotevski A, Herrenkohl TI, Bond L, Kim MJ, Toumbourou JW, & Catalano RF (2011). Longitudinal consequences of adolescent bullying perpetration and victimisation: A study of students in Victoria, Australia. Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health, 21(2), 107–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong JS, Espelage DL, Grogan-Kaylor A, & Allen-Meares P (2012). Identifying potential mediators and moderators of the association between child maltreatment and bullying perpetration and victimization in schools. Educational Psychology Review, 24(2), 167–186. [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh Y-P, Shen A-T, Hwa H-L, Wei H-S, Feng J-Y, & Huang S-Y (2020). Associations between child Maltreatment, dysfunctional family environment, post-traumatic stress disorder and children’s bullying perpetration in a national representative sample in Taiwan. Journal of Family Violence, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Jansen PW, Verlinden M, Berkel A-V, Mieloo C, van der Ende J, Veenstra R, … Tiemeier H (2012). Prevalence of bullying and victimization among children in early elementary school: Do family and school neighbourhood socioeconomic status matter? BMC Public Health, 12(1). 10.1186/1471-2458-12-494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juvonen J, & Graham S (2014). Bullying in schools: The power of bullies and the plight of victims. Annual review of psychology, 65, 159–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King KA, Merianos AL, & Vidourek RA (2016). Characteristics of marijuana acquisition among a national sample of adolescent users. American Journal of Health Education, 47(3), 126–135. [Google Scholar]

- Klomek AB, Sourander A, & Gould M (2010). The association of suicide and bullying in childhood to young adulthood: A review of cross-sectional and longitudinal research findings. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 55(5), 282–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kodish T, Herres J, Shearer A, Atte T, Fein J, & Diamond G (2016). Bullying, depression, and suicide risk in a pediatric primary care sample. Crisis, 37(3), 241–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebrun-Harris LA, Sherman LJ, Limber SP, Miller BD, & Edgerton EA (2019). Bullying victimization and perpetration among US children and adolescents: 2016 National Survey of Children’s Health. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 28(9), 2543–2557. [Google Scholar]

- Lereya ST, Copeland WE, Zammit S, & Wolke D (2015). Bully/victims: A longitudinal, population-based cohort study of their mental health. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 24(12), 1461–1471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo CKM, Ho FK, Emery C, Chan KL, Wong RS, Tung KTS, & Ip P (2021). Association of harsh parenting and maltreatment with internet addiction, and the mediating role of bullying and social support. Child Abuse & Neglect, 113, 104928. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2021.104928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovegrove PJ, & Cornell DG (2014). Patterns of bullying and victimization associated with other problem behaviors among high school students: A conditional latent class approach. Journal of Crime and Justice, 37(1), 5–22. [Google Scholar]

- Logan-Greene P, & Jones AS (2015). Chronic neglect and aggression/delinquency: A longitudinal examination. Child Abuse & Neglect, 45, 9–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovegrove PJ, Henry KL, & Slater MD (2012). Examination of the predictors of latent class typologies of bullying involvement among middle school students. Journal of School Violence, 11(1), 75–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeely CA, Nonnemaker JM, & Blum RW (2002). Promoting school connectedness: Evidence from the National Study of Adolescent Health. Journal of School Health, 72(4), 138–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menesini E, & Salmivalli C (2017). Bullying in schools: The state of knowledge and effective interventions. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 22(sup1), 240–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moses M, & Williford A (2017). Individual indicators of self-reported victimization among elementary school-age students: A latent class analysis. Children and Youth Services Review, 83, 33–40. [Google Scholar]

- Nakamoto N, & Schwartz D (2009). Is peer victimization associated with academic achievement? A meta-analytic review. Social Development, 19, 221–242. [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson JV, Chen Y, & Huang C-C (2018). Children’s exposure to intimate partner violence and peer bullying victimization. Children and Youth Services Review, 91, 439–446. [Google Scholar]

- Nylund K, Bellmore A, Nishina A, & Graham S (2007). Subtypes, severity, and structural stability of peer victimization: What does latent class analysis say? Child Development, 78(6), 1706–1722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brennan LM, Bradshaw CP, & Sawyer AL (2009). Examining developmental differences in the social-emotional problems among frequent bullies, victims, and bully/victims. Psychology in the Schools, 46(2), 100–115. [Google Scholar]

- O’Hara MA (2020). Peer victimization of maltreated youth: Distinct risk for physically abused versus neglected children. Journal of School Health, 90(6), 457–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olweus D (1994). Bullying at school. In Aggressive Behavior (pp. 97–130). Boston, MA: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Özdemir M, & Stattin H (2011). Bullies, victims, and bully-victims: A longitudinal examination of the effects of bullying-victimization experiences on youth well-being. Journal of Aggression, Conflict and Peace Research, 3(2), 97–102. [Google Scholar]

- Perren S, & Alsaker FD (2006). Social behavior and peer relationships of victims, bully-victims, and bullies in kindergarten. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 47(1), 45–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Priesman E, Newman R, & Ford JA (2018). Bullying victimization, binge drinking, and marijuana use among adolescents: Results from the 2013 National Youth Risk Behavior Survey. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 50(2), 133–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radliff KM, Wheaton JE, Robinson K, & Morris J (2012). Illuminating the relationship between bullying and substance use among middle and high school youth. Addictive Behaviors, 37(4), 569–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS (1977). The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1(3), 385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Reichman NE, Teitler JO, Garfinkel I, & McLanahan SS (2001). Fragile families: Sample and design. Children and Youth Services Review, 23(4-5), 303–326. [Google Scholar]

- Rettew DC, & Pawlowski S (2016). Bullying. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 25(2), 235–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeds PM, Harkness KL, & Quilty LC (2010). Parental maltreatment, bullying, and adolescent depression: Evidence for the mediating role of perceived social support. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 39(5), 681–692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solberg ME, & Olweus D (2003). Prevalence estimation of school bullying with the Olweus Bully/Victim Questionnaire. Aggressive Behavior: Official Journal of the International Society for Research on Aggression, 29(3), 239–268. [Google Scholar]

- Stein JA, Dukes RL, & Warren JI (2007). Adolescent male bullies, victims, and bully-victims: A comparison of psychosocial and behavioral characteristics. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 32(3), 273–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Hamby SL, Finkelhor D, Moore DW, & Runyan D (1998). Identification of child maltreatment with the Parent-Child conflict Tactics Scales: Development and psychometric data for a national sample of American Parents. Child Abuse & Neglect, 22(4), 249–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takizawa R, Maughan B, & Arseneault L (2014). Adult health outcomes of childhood bullying victimization: Evidence from a five-decade longitudinal British birth cohort. American Journal of Psychiatry, 171(7), 777–784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teisl M, & Cicchetti D (2008). Physical abuse, cognitive and emotional processes, and aggressive/disruptive behavior problems. Social Development, 17(1), 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Tharp-Taylor S, Haviland A, & D’Amico EJ (2009). Victimization from mental and physical bullying and substance use in early adolescence. Addictive behaviors, 34 (6–7), 561–567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomczyk S, Hanewinkel R, & Isensee B (2015). Multiple substance use patterns in adolescents—A multilevel latent class analysis. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 155, 208–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toth SL, & Cicchetti D (2013). A developmental psychopathology perspective on child maltreatment. Child Maltreatment, 18(3), 135–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trickett PK, & McBride-Chang C (1995). The developmental impact of different forms of child abuse and neglect. Developmental Review, 15(3), 311–337. [Google Scholar]

- Ttofi MM, Ttofi MM, Farrington DP, Lösel F, & Loeber R (2011). Do the victims of school bullies tend to become depressed later in life? A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Journal of Aggression, Conflict and Peace Research, 3(2), 63–73. [Google Scholar]

- Tucker JS, de la Haye K, Kennedy DP, Green HD, & Pollard MS (2014). Peer influence on marijuana use in different types of friendships. Journal of Adolescent Health, 54(1), 67–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turns BA, & Sibley DS (2018). Does maternal spanking lead to bullying behaviors at schools? A longitudinal study. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 27, 2824–2832. [Google Scholar]

- Valdebenito S, Ttofi M, & Eisner M (2015). Prevalence rates of drug use among school bullies and victims: A systematic review and meta-analysis of cross-sectional studies. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 23, 137–146. [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Zhao F, Yang J, Gao L, Li B, Lei L.i., … Wang P (2020). Childhood maltreatment and bullying perpetration among Chinese adolescents: A moderated mediation model of moral disengagement and trait anger. Child Abuse & Neglect, 106, 104507. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williford AP, Brisson D, Bender KA, Jenson JM, & Forrest-Bank S (2011). Patterns of aggressive behavior and peer victimization from childhood to early adolescence: A latent class analysis. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 40(6), 644–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe DA, Crooks CC, Chiodo D, & Jaffe P (2009). Child maltreatment, bullying, gender-based harassment, and adolescent dating violence: Making the connections. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 33(1), 21–24. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon D (2020). Peer-relationship patterns and their association with types of child abuse and adolescent risk behaviors among youth at-risk of maltreatment. Journal of Adolescence, 80, 125–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon D, Yoon S, Park J, & Yoon M (2018). A pernicious cycle: Finding the pathways from child maltreatment to adolescent peer victimization. Child Abuse & Neglect, 81, 139–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]