Abstract

Background:

We tested the capacity of the 60-site VA Women’s Health Practice-Based Research Network (WH-PBRN), embedded within VA, to employ a multisite card study to collect women Veterans’ perspectives about Complementary and Integrative Health (CIH) and to rapidly return findings to participating sites and partnered national policy-makers in support of a Learning Health System (LHS) wherein evidence generation informs ongoing improvement.

Methods:

VA primary care clinic clerks and nurses distributed anonymous surveys (patient feedback forms) at clinics for up to two weeks in fiscal year 2017, asking about CIH behavior and preferred delivery methods. We examined the project’s feasibility, representativeness, acceptability, and impact via a tracking system, national administrative data, debriefing notes, and three surveys of WH-PBRN Site Leads.

Results:

Twenty geographically diverse and largely representative VA Medical Centers and 11 Community-Based Outpatient Clinics volunteered to participate. Over six months, N = 1191 women Veterans responded (median 57; range 8–151 per site). In under three months, we returned local findings benchmarked against multisite findings to all participating sites and summary findings to national VA partners. Sites and partners disseminated results to clinical and leadership stakeholders, who then applied results as warranted.

Conclusions:

VA effectively mobilized an embedded PBRN to implement a timely, representative, acceptable and impactful operations project.

Implications:

Card studies by PBRNs within large, national healthcare systems can provide rapid feedback to participating sites and national leaders to guide policies, programs, and practices.

Level of Evidence:

Self-selected respondents could have biased results.

1. Introduction

In their seminal article, Atkins, Kilbourne and Shulkin1 highlight the degree to which the Veterans Health Administration (VA) functions as a Learning Health System (LHS), and encourage VA to further embrace this model. An LHS emphasizes interaction, collaboration, and synergies among researchers, clinicians, and educators, generating a mutually reinforcing relationship between research, practice, and policy.2 The National Academy of Medicine1 LHS principles describe the importance of “Real-time access to knowledge”, “Engaged, empowered patients” and “Supportive system competencies.” The latter includes the idea that an LHS should create “feedback loops for continuous learning and system improvement.“3

Collaboration between clinicians and researchers is central to the approach of the VA Women’s Health Practice-Based Research Network (WH-PBRN),4-6 a national community of 60 Health Care Systems (HCSs) each with an embedded WH-PBRN Site Lead dedicated to enhancing women Veterans’ health and health care through continuous learning and by catalyzing connections among local site clinicians and researchers. Embedded health services researchers who lead the WH-PBRN’s national Coordinating Center and broader Women’s Health Research Network (with VA HSR&D service-directed funding) support Site Leads’ frontline efforts, partnering with the national office of Women’s Health Services (WHS) and other VA policy offices via long-term relationships and bi-directional information-sharing. This makes the WH-PBRN a promising testing ground for LHS principles.

PBRNs often turn to “card studies”—brief patient and/or provider surveys (originally the size of an index card) at the point of care–to achieve rapid, low-overhead data collection about patient experiences or other clinically meaningful information in real-world, practice-based contexts.7,8 Intrigued by the potential for card studies to quickly generate VA data relevant to both frontline clinicians/managers and national policy-makers, we responded to a request from two VA clinical operations partners – the VA Office of Patient Centered Care and Cultural Transformation (OPCC&CT) and VA WHS – for patient-based information about women Veterans’ Complementary and Integrative Health (CIH) behaviors and preferences. Given VA’s increasing focus on CIH9-14 and the lack of data at the time specific to women Veterans’ preferences, the WH-PBRN seized this opportunity to design and test a card study methodology suitable to our structure, to address a timely operational need.

Our objective for this inaugural WH-PBRN card study – known internally as the CIH Veteran Feedback Project – was to examine it as a proof-of-concept project to develop processes within the WH-PBRN for rapid data collection to address queries from operations partners, while also returning impactful information to participating sites. We examined five types of CIH: yoga, mindfulness/meditation, tai chi/qigong, therapeutic massage, and acupuncture. In support of the LHS model, we planned to provide participating sites with individually tailored reports showing their site’s results benchmarked against national multisite findings for use as local program planning tools, and to provide our national partners with multisite data for use in patient-centered programming and policy development. Here we detail our multisite card study methodology, describe the extent to which it was feasible, representative, acceptable, and impactful, and catalogue lessons learned.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Setting

Supported by a national Coordinating Center (staffed with a director, program manager, coordinator, and research assistant) and the encompassing Women’s Health Research Network, the WH-PBRN sites stand ready to participate in multisite research or quality improvement projects, enabling investigators to access women Veterans, their providers, and their care settings efficiently via cultivated relationships.6 In addition to such projects, the WH-PBRN embedded Site Leads gather monthly on an interactive national call.

2.2. Roles and responsibilities

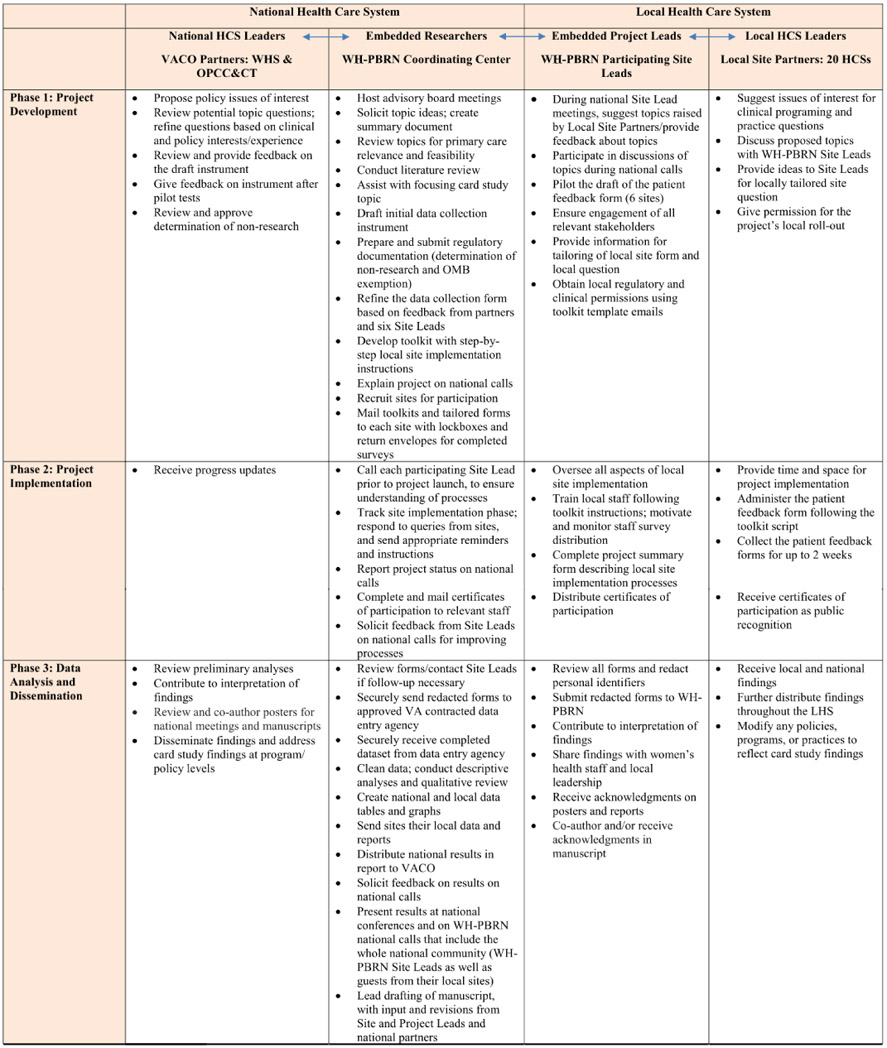

Table 1 describes involvement of the national VA Central Office (VACO) partners (OPCC&CT and WHS), embedded researchers in the national WH-PBRN Coordinating Center, locally embedded WH-PBRN Site Leads, and local participating sites in designing and implementing the project and disseminating findings. All project phases (Development, Implementation, and Data Analysis/Dissemination) involved all stakeholders and incorporated mutual feedback and learning opportunities.

Table 1.

|

Abbreviations: CIH – Complementary and Integrative Health. HCS – Health Care System. VACO – VA Central Office. WHS – Women’s Health Services. OPCC&CT – Office of Patient-Centered Care & Cultural Transformation. VA – Veterans Health Administration. WH-PBRN – Women’s Health Practice-Based Research Network. LHS – Learning Health System. OMB – Office of Management and Budget.

Table structured after Cole et al., 2015 with the author’s permission. Cole, A., et al., Evaluating the Development, Implementation and Dissemination of a Multisite Card Study in the WWAMI Region Practice and Research Network. Clin Transl Sci, 2015.8 (6): p. 764–9.

2.3. Phase 1: project development

OPCC&CT, WHS, additional CIH experts and WH-PBRN embedded researchers designed an anonymous, voluntary, one-page patient feedback form (Appendix A) for distribution to women during Primary Care or Women’s Health Clinic appointments; WH-PBRN researchers piloted and refined the instrument. Since national partners contributed to patient feedback form content, forms met partners’ needs by asking about preferences for specific CIH approaches and delivery methods, including needs for gender-tailoring services. If desired, a site could inquire about an additional locally-relevant CIH approach, beyond the five types already on all forms. (Examples of CIH approaches sites added included aromatherapy and healing touch.) The form asked respondents’ age groups; where they received primary care (VA Medical Center [VAMC], Community-Based Outpatient Clinic [CBOC], Other); whether they had used each of the five types of CIH previously, and future preferences for CIH delivery methods. The San Juan VAMC Site Lead assisted in translating the form into Spanish for use in Puerto Rico.

After addressing logistical and regulatory issues at a national level, we developed an Implementation Toolkit with step-by-step instructions and communication templates, including letters for enlisting local leaders’ support; instructions for training clerks/nurses in patient feedback form distribution; a script for clerks/nurses to use when offering the survey; and patient-facing frequently asked questions.

To generate excitement among Site Leads, prior to the September 2016 national WH-PBRN Site Lead phone call, we conducted a two-question Practice Scan (rapid key informant survey) via email, asking all Site Leads about CIH availability at their sites. We then reported Practice Scan findings on the national call, making for an interactive, dynamic meeting that culminated with announcement of the upcoming CIH card study.

2.4. Phase 2: project implementation

Site Leads could designate an appropriate Project Lead (with the Site Lead acting as Co-Project Lead, to streamline communication with the WH-PBRN); for simplicity, this manuscript refers to both as “Site Leads.” Before project launch, the WH-PBRN Coordinating Center held individual phone calls with participating Site Leads to discuss site-specific project implementation.

Within a six-month period (October 2016–March 2017), each site collected data for up to two weeks or until they had received 100 patient feedback forms, whichever came first. Clerks and/or nurses distributed forms to sequential women presenting for appointments in primary care clinics, using a prepared script. Women placed completed forms in lockboxes. The Site Lead reviewed completed forms for immediately actionable items, such as complaints about clinical processes or suggestions for systems improvements; redacted any inadvertently-included Protected Health Information; then scanned and securely sent the completed, redacted forms to the WH-PBRN Coordinating Center. Site Leads listed participating staff so that certificates of participation could be mailed.

2.5. Phase 3: dissemination

Throughout the project, on monthly national WH-PBRN calls, we updated Site Leads about project progression. After entering CIH data, we conducted descriptive analyses of data from all sites in aggregate, and for each individual site.

In May 2017, we sent each participating facility its own local findings benchmarked against national aggregated results, as well as an electronic spreadsheet containing their site’s data, suitable for sharing with leaders and frontline clinicians at their site. On the May 2017 national WH-PBRN full community phone call, we presented national findings, inviting discussion, interpretation, and questions about the site-specific and national reports.

To uphold communication and collaboration with our VA Central Office partners, we provided preliminary findings to them whenever available. Reports went to both partners’ offices in February 2017 and June 2017.

2.6. Evaluation of card study processes

We used our tracking system to assess feasibility: reach (number of sites that participated out of number invited); number of completer sites; number of forms returned; and number of months for the project timeline. At the project’s start, we designed a weekly timeline, adjusting it as needed over the project period. We logged the time interval required during each stage in the process by prospectively tracking when sites started and finished the implementation steps. (Communications tracking database elements are available upon request.) For representativeness, we compared national VA administrative data (maintained by the WH-PBRN for ongoing site characterization) for participating sites to national data, and mapped the locations of participating sites. For acceptability, we tallied responses from Exit Surveys (completed by each Site Lead at the end of local data collection, to describe local implementation processes; response rate 97%, 30 of 31 participating clinics at VAMCs/CBOCs; Appendix B) to see how many mentioned positive project uptake or implementation barriers.

For impact we assessed variability in women’s preferences for different CIH approaches (as a marker of actionable strategic priorities); identified dissemination activities and practice/policy impacts by cataloguing responses to Follow-Up Survey 1 (distributed to the 20 participating sites about 2 years after distributing Site Reports, response rate 85%) and Follow-Up Survey 2 (distributed to the 15 co-author sites about a year thereafter, response rate 100%); and queried our national partners about policy and practice that might have been influenced by the CIH Card Study.

We used a matrix analysis approach15 to derive lessons learned from the Exit Surveys (from an item about Site Leads’ recommendations for subsequent card studies), supplementing with the WH-PBRN Coordinating Center team’s observations collected at weekly internal debriefing meetings

3. Results

3.1. Feasibility, representativeness and acceptability

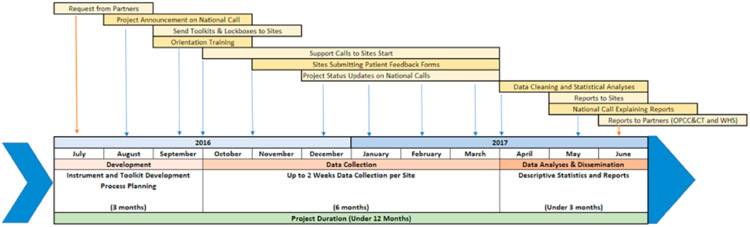

Regarding feasibility, 23 of 60 sites expressed interest; three encountered logistical issues preventing participation, and 20 (87% of those expressing interest) completed data collection. Sites collected a median of 57 (range 8–151) forms per site (total 1191 forms nationally); we combined results for all clinics within a HCS, so two sites had over 100. The project took one year to complete (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

CIH card study project timeline.

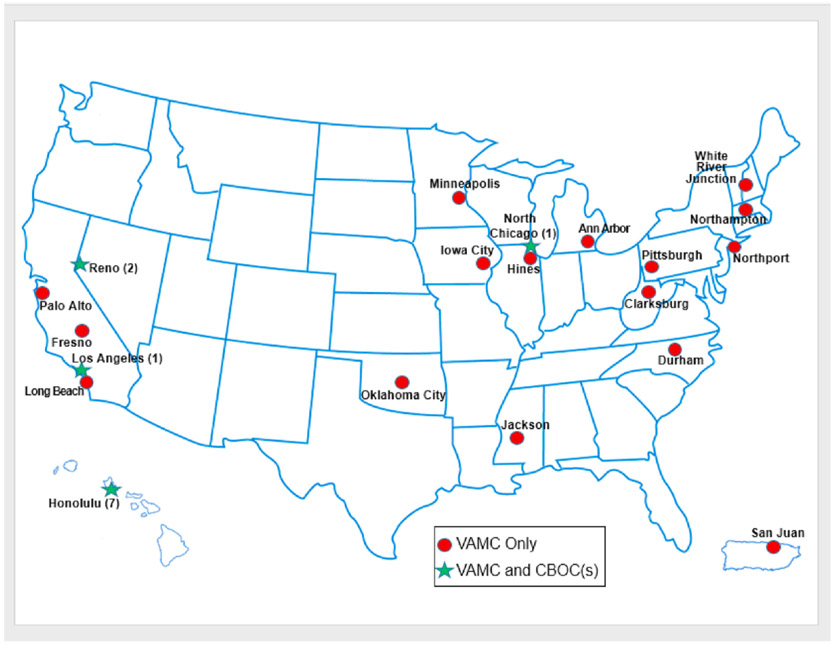

Regarding representativeness, volunteer sites reflected national demographics and health conditions (Table 2). Site of care was a VAMC for 83% of women and CBOC/Other for 17%. Sites were geographically dispersed across 16 states; in addition to 20 VAMCs, 11 of their CBOCs participated (Fig. 2).

Table 2.

Characteristics of women Veterans receiving outpatient care in FY17 at card study sites* benchmarked against women Veterans receiving outpatient care in FY17 at any VA Site.

| Characteristics | Women Veterans at Card Study HCSs (20 HCSsa) |

Women Veterans at Any VA HCS nationally (141 HCSs) |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

| Median N = 3027 women per HCS (Range 1129–6754 women) |

Median N = 3052 women per HCS (Range 111-14,653 women) |

|

| Sites Median % (Range) | Sites Median % (Range) | |

| Age, N (%) | ||

| 18–44 years old | 39.4 (29.9–51.6) | 38.8 (28.5–58.9) |

| 45–64 years old | 43.8 (35.4–51.8) | 46.7 (32.7–58.9) |

| 65+ years old | 13.4 (9.2–22.0) | 13.8 (5.0–25.9) |

| Race/Ethnicity, N (%) | ||

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 1.2 (0.3–4.2) | 1.1 (0.3–13.0) |

| Asian | 1.0 (0.1–12.6) | 0.8 (0.1–77.5) |

| Black/African-American | 17.9 (1.9–67.5) | 15.4 (0.4–72.2) |

| Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander | 0.8 (0.4–15.9) | 0.8 (0.2–15.9) |

| White | 65.0 (28.1–91.5) | 69.5 (8.1–92.7) |

| Hispanic | 6.7 (1.1–77.6) | 3.4 (0.9–77.6) |

| Unknown | 6.0 (2.6–18.0) | 6.3 (1.9–20.6) |

| Rural/Urban, N (%) | ||

| Highly rural | 0.6 (0.0–8.4) | 0.7 (0.0–13.0) |

| Other rural | 28.2 (2.7–74.9) | 31.6 (2.7–86.1) |

| Urban | 66.5 (16.8–97.2) | 65.7 (5.1–97.2) |

| Island | 0.0 (0.0–10.7) | 0.0 (0.0–10.7) |

| Condition domains, N (%) | ||

| Infectious Disease | 31.1 (21.0–38.3) | 30.2 (9.9–45.3) |

| Endocrine/Metabolic/Nutritional | 54.0 (39.1–66.4) | 55.6 (35.1–67.7) |

| Cardiovascular | 36.7 (28.9–51.3) | 38.2 (24.5–53.4) |

| Respiratory | 34.9 (22.7–40.0) | 36.3 (22.7–46.6) |

| Gastrointestinal | 32.6 (21.3–46.2) | 34.9 (21.3–47.8) |

| Urinary | 16.1 (12.0–21.7) | 16.7 (10.5–27.9) |

| Reproductive Health | 28.4 (20.1–39.1) | 27.7 (7.2–41.2) |

| Breast | 6.7 (4.2–11.7) | 6.1 (2.7–16.0) |

| Cancer | 6.1 (3.8–7.8) | 5.8 (2.7–9.2) |

| Hematologic/Immunologic | 9.9 (5.6–14.9) | 9.9 (3.6–20.7) |

| Musculoskeletal | 59.9 (54.7–73.6) | 61.2 (50.6–73.6) |

| Neurologic | 32.0 (29.0–38.8) | 32.7 (25.7–39.7) |

| Mental Health/Substance Use Disorder | 52.3 (44.4–59.0) | 53.2 (40.9–62.8) |

| Sense Organ | 36.7 (22.1–47.2) | 36.5 (20.0–51.8) |

| Dental | 11.4 (7.9–17.9) | 12.0 (5.4–20.9) |

| Dermatologic | 26.1 (17.0–30.3) | 25.4 (13.5–37.3) |

| Other | 56.7 (47.9–66.5) | 56.3 (18.9–68.5) |

Health Care Systems (HCS) at the VA operate principally with one VAMC and multiple CBOCs; 20 HCSs participated in the card study. Nationally in FY17 there were 141 HCSs. Median percentages reported for the Card Study HCSs reflect all women Veterans receiving outpatient care at those HCSs, independent of whether those women participated in the Card Study. Data came from Veterans Health Administration, Office of Women’s Health Services, Women’s Health Evaluation Initiative (WHEI) Master Database, FY00-FY16.

Fig. 2.

CIH card study–map of participating sites.

Regarding acceptability, 14 of 30 responding clinics said they had no suggestions for change, praised the project, and/or said clinic staff were cooperative and enjoyed the project; six clinics offered no suggestions, or provided unusable responses. Four clinics mentioned implementation barriers: competing demands of clinical staff, and forms distribution issues.

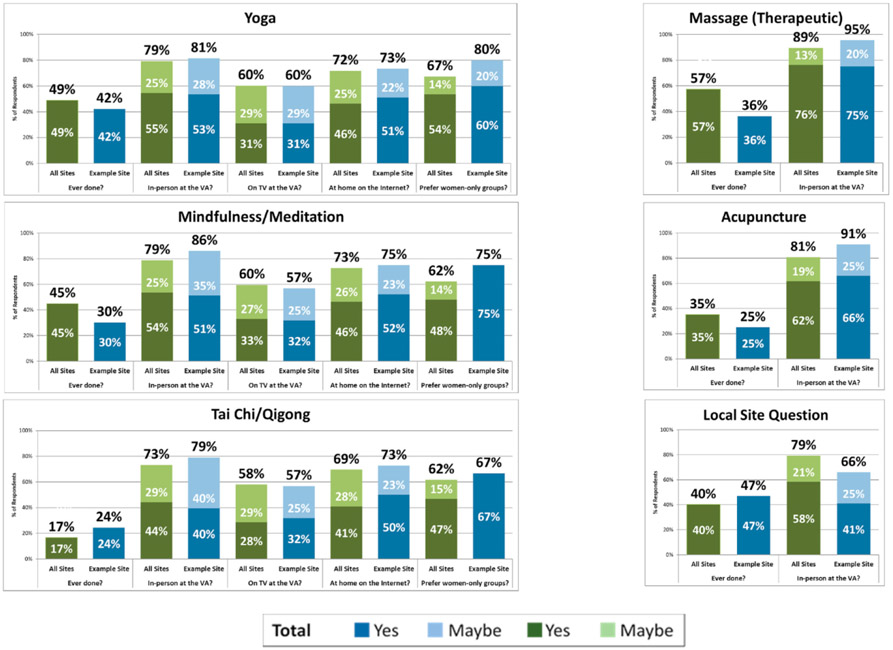

3.2. Impact: CIH card study produced actionable results

The card study successfully elicited women’s preferences, distinguishing between several service delivery alternatives. For example, multisite CIH findings (“all sites” bars in Fig. 3) showed that most women Veterans expressed interest in participating in CIH activities inperson at their VAs: therapeutic massage (89%); acupuncture (81%); yoga (79%); mindfulness/meditation (79%); and tai chi/qigong (73%). In addition, across group-delivered CIH approaches, 62%–67% preferred women-only classes. For every CIH approach, over 70% (range 73%–89%) would participate at the VA in person, over two-thirds (69%–73%) would do the activity at home over the internet, and the majority (58%–60%) would consider participating on a TV at their own VA. In May 2017, we sent participating facilities their own findings benchmarked against aggregated results; Fig. 3 illustrates the site report process.

Fig. 3.

CIH card study site-specific report example, women veterans’ preferences.

3.3. Impact: dissemination activities by Site Leads and VA Central Office

Participating sites mentioned on the national WH-PBRN Site Lead call that they planned to share results with diverse individuals: Chief of Staff; Chiefs of Research, Primary Care or Behavioral Health; Health Promotion and Disease Prevention Manager; CIH Team; Women’s Health Clinic staff; Women Veterans Health Committee; Patient Aligned Care Team meeting; and Clinical Executive Board. Then, in Follow-up Survey 1, all 17 responding sites confirmed having used the report to inform local leadership of women Veterans’ CIH preferences. Our national partners shared some of the results immediately after project completion; for example, the National Program Manager of the Integrative Health Coordinating Center and OPCC&CT presented on a Women’s Health Services National call related to Whole Health.

3.4. Impact: changes to practice and policy

Fourteen sites used the CIH card study to let leadership know the value of belonging to the WH-PBRN (per Follow-Up Survey 1); indeed, several Site Leads reported this as having been an opportunity to meet hospital leadership and/or staff for the first time. Six used it to inform clinic policy, programs, and practices, and four mentioned other uses. Among the latter, one Site Lead said they used the data to support a funding application to Office of Rural Health.

Follow-up Survey 2 provided additional details about effects of the project upon local practice. Examples included a CIH-related train-the-trainer educational opportunity, a Whole Health conference with speakers and activities, and an innovative program proposal to create more women-only classes.

One Site Lead said, “… the CIH study added extra evidence and support to the blossoming opportunities that [Clinic name redacted] was beginning to incorporate into our pain management and overall wellness armamentarium …, with eventual hiring of an acupuncturist on site …. ”

Others said, “I have used the information to show leadership what women Veteran[s] are more likely to use …. This survey could help to support the proposal that we are currently developing [to create a Women’s Whole Health Program].”

and, “The CIH survey provided an opportunity for women Veterans to inquire about the available resources, such as, acupuncture, yoga, and tai-chi. This led to increased utilization and referrals to these programs.”

National partners reported that they disseminated results to help inform field programming and awareness around CIH for women Veterans. In addition, the joint card study project contributed to enhancing collaborations between the two national VA offices, e.g., with OPCC&CT staff presenting whole health updates at national WHS Mini-Residencies.

3.5. Lessons learned

Key lessons learned from Exit Surveys (corroborated in internal debriefing meetings) include the following suggestions for embedded researchers overseeing card study implementation within a healthcare system:

Create an Implementation Toolkit with adaptable tools that contribute to project fidelity and low staff burden (e.g. templates for communications with leadership and staff, training materials for staff distributing the forms).

Generate and maintain excitement about the topic prior to implementation to encourage local “champions” and to foster staff and leadership “buy-in”.

Minimize demands on busy Site Leads’ and staffs’ time.

Additional lessons derived from internal debriefings included:

Allow sites time for preparations (e.g. tailoring local forms, obtaining local approvals, conducting training) before form distribution starts.

Create a robust tracking system to monitor each site by project stage and date.

Maintain good communications with sites and national partners by keeping them informed of progress and soliciting feedback at all project stages; identify a single point of contact (Site Lead) to represent all involved clinics at a participating site.

4. Discussion

With preparatory groundwork, a toolkit of standardized processes, and up to two weeks of data collection at each site, the WH-PBRN efficiently collected and reported clinic-based data from over 1000 women Veterans at 31 geographically dispersed VA locations. Consistent with LHS principles, multilevel participation of clinical stakeholders at the local and national levels – in collaboration with embedded WH-PBRN Site Leads at the local level and embedded WH-PBRN researchers at the national level – led to highly integrated efforts at every phase: project development, implementation, and results dissemination. At the conclusion, (a) participating sites received local results benchmarked against national findings for local dissemination, results of a locally-tailored question if they elected to use that option, and much-appreciated certificates of participation; (b) all WH-PBRN Site Leads (even at non-participating sites) were briefed on findings; and (c) national partners received program-relevant results, which they disseminated further. The WH-PBRN-based card study approach proved to be a successful vehicle for generating findings relevant to practice and policy. For example, it demonstrated an exceptionally high demand for these services among women Veterans, pointed to services to consider prioritizing (such as therapeutic massage and acupuncture), and clarified women’s preferences for service delivery modalities, with two-thirds preferring women-only classes for group activities. In many cases, local sites and national partners acted upon findings.

Several limitations merit note. First, card studies exemplify the need to balance rigor with feasibility constraints. For example, we used a convenience sample of sites opting to participate and sequential women agreeing to complete the form; initial attempts at capturing response rate proved too burdensome for clinic clerks/nurses; and we extended the field timeline to accommodate site schedules. Accounting for multiple demands on staff time by minimizing card study requirements resulted in high Site Lead participation and therefore a large overall sample size. However, the sample size was small at a few HCSs. Consequently, we emphasized in national presentations and site reports that findings were for operational programming purposes, not research, and that sites with small samples should consider results exploratory. Second, some cross-site variation in implementation could have affected local participation; to counter this, we took multiple steps to enhance fidelity to card study processes (e.g. Implementation Toolkit, national trainings, individual site launch calls, local follow-up). Third, identification of lessons learned and feasibility considerations would have been strengthened by supplementing our Exit Survey data via semi-structured interviews with staff at participating sites.

This approach also had multiple strengths. Data collection was rapid, and capitalized upon the WH-PBRN’s existing national infrastructure to improve representativeness; indeed, 11 CBOCs participated, demonstrating card studies’ promise for reaching remote sites typically excluded from national data collection efforts. It overcame challenges inherent in traditional methods of coding and tracking, such as the Electronic Health Record and other automated systems, which only recently began developing CIH monitoring capabilities. The approach was patient-centric, eliciting women Veterans’ own service delivery preferences, while at the same time being responsive to the information needs of national policy makers and front-line providers. Engagement and new or strengthened collaborations occurred within sites, across sites, and in VA Central Office, and communication fostered broad dissemination of findings and, in many cases, impacts upon clinical practice.

5. Conclusions

WH-PBRN-based card studies provide a unique vehicle to further promote a learning health system within VA. They can rapidly generate evidence grounded in topical priorities of national policy-makers and frontline clinical staff, to inform strategic clinical program planning and policy development at national and local levels and evidence-based resource allocation decisions.

Inspired by the success of this inaugural card study and drawing upon lessons learned, the WH-PBRN has applied the methodology to another emerging policy-relevant issue identified by our national partners (stranger harassment at VA). These card studies promote further LHS feedback loops designed to give voice to women Veterans’ preferences and enhance their care.

Supplementary Material

Source(s) of support/funding

This program evaluation work was sponsored by Women’s Health Services (WHS) in VA Central Office and by VA’s Office of Patient-Centered Care and Cultural Transformation (OPCC&CT); these offices also provided valuable policy context relevant to the design of the project and interpretation of results, and contributed to dissemination of findings. Funding for administrative support of this project came through the Women’s Health Research Network (SDR 10–012; Pis Yano, Frayne, Hamilton). Health Care System-level roll-up data were provided by Women’s Health Services. Dr. Yano receives salary support from a VA HSR&D Senior Research Career Scientist Award (RCS 05–195). The decision to submit was made by the authors.

Abbreviations:

- CBOC

Community-Based Outpatient Clinic

- CIH

Complementary and Integrative Health

- HCS

Health Care System

- LHS

Learning Health System

- OMB

Office of Management and Budget

- OPCC&CT

Office of Patient-Centered Care and Cultural Transformation

- QI

Quality Improvement

- VA

Veterans Health Administration

- VACO

VA Central Office

- VAMC

VA Medical Center

- WH-PBRN

Women’s Health Practice-Based Research Network

- WHS

Women’s Health Services.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the contributions to this paper of Jill Darling, Mayra Vega Hernandez, Alissa Simon, and Ismelda Canelo.

The WH-PBRN Expert Consultants provided important methodological input throughout the card study development process: Rowena Dolor, Michael Parchman.

The members of the Women’s Health Practice-Based Research Network’s card study planning committee contributed foundational perspectives that informed this work: John Zeber (chair); Bevanne Bean-Mayberry; Anne Dembitzer; Christine Elnitsky; David Ganz; Karen Goldstein; Diane Harness-Digloria; Tina Kaur; Silvina Levis; Kristin Mattocks; Thomas Rocco; Tina Kaur Thethi.

The CIH QUERI Partnered Evaluation Initiative (PEC 16–354) and our national policy partners (Benjamin Kligler, Laura Krejci, Alison Whitehead at OPCC&CT and Patricia Hayes at Women’s Health Services) provided critical contextual information to inform this work.

This project would not have been possible without the tremendous contributions of the participating WH-PBRN Site Leads (and Site Leads who contributed to the pilot phase of this work are denoted with an asterisk):

Bevanne Bean-Mayberry, MD, MHS* (Los Angeles); Sudha Bhoopalam, MD/Karen Saban, PhD, RN (Hines); Kelly Buckholdt, PhD (Jackson); Deborah DiNardo, MD, MS*/Sonya Borrero, MD, MS* (Pittsburgh); Kathleen B. Dussan, MD (Ann Arbor); Karen Goldstein, MD, MSPH* (Durham); Nicole Grant, MD*/Jennifer S. Lee, MD, PhD* (Palo Alto); Lisa Hardman, DNP, CDE, RN (Clarksburg); Elizabeth Hill, PhD, RN/Kristina McCain, MD (Reno); Tahira Juiris, MD, MPH/Teresa L. Todela, MSN, RN (North Chicago); Erin Krebs, MD, MPH (Minneapolis); Denise Koutrouba, MS, BSN, PHN, WHNP-BC/Judy Carlson, EdD, APRN, FNP (Honolulu); Kristin Mattocks, PhD, MPH* (Northampton); Mabel E. Quiñones-Vazquez, PhD/Agnes Santiago-Cotto, MSW (San Juan); Gina G. Rawson, DNP-C, APRN-BC (Long Beach); Christiane Rollenhagen, PhD, MS/Carey Russ, MSW (White River Junction); Jeanette Rylander, MD; Regina Godbout, MD (Fresno); Anne Sadler, PhD, RN* (Iowa City); Divya Singhal, MD; Ishita Thakar, MD, FACP (Oklahoma City); Athena Zias-Dilena, MD (Northport).

Furthermore, the authors would like to thank the Site Leads who formed the WH-PBRN-CIH Writing Group for the invaluable content and feedback they provided.

The authors express great appreciation to the women Veterans who participated.

Footnotes

Recommended citation

Golden RE, Klap R, Carney DV, Yano EM, Hamilton AB, Taylor SL, Kligler B, Whitehead AM, Saechao F, Zaiko Y, Pomernacki A, Frayne SM, for the WH-PBRN-CIH Writing Group. Promoting Learning Health System Feedback Loops: Experience with a VA Practice-Based Research Network Card Study.

Disclosure/conflict of interest/declaration of interest statement

None of the authors have relevant commercial associations that might pose a conflict of interest. Individual disclosure statements are available upon request. The corresponding author has also completed and submitted as a separate document the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hjdsi.2020.100484.

Disclaimer

The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States government.

Publication of the supplement was supported by AcademyHealth.

Previously called the Institute of Medicine.

Author contributions/CRediT authorship statement

All the authors listed meet authorship criteria and all who meet authorship criteria are listed. Below please find a summary of author contributions by specific activities. Individual authorship statements are available upon request.

The corresponding author, Rachel Golden, agrees to serve as the primary correspondent with the editorial office, to review the edited manuscript and proof, and to make decisions regarding release of information in the manuscript to the media, federal agencies, or both.

- The manuscript represents original and valid work and that neither this manuscript nor one with substantially similar content under their authorship has been published or is being considered for publication elsewhere, except as described in an attachment, and copies of closely related manuscripts are provided; and

- They agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved; and

- If requested, they will provide the data or will cooperate fully in obtaining and providing the data on which the manuscript is based for examination by the editor or the editor’s assignees; and

- They agree to allow the corresponding author to serve as the primary correspondent with the editorial office, to review the edited manuscript and proof, and to make decisions regarding release of information in the manuscript to the media, federal agencies, or both; and

- They have given final approval of the submitted manuscript.

In addition, the following primary authors, RG, RK, DC, EY, AH, ST, BK, AW, FS, YZ, AP, and SF, certify that they have participated sufficiently in the work to take public responsibility for the whole or part of the content; have made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the paper or the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of the data; have made substantial contributions to the drafting or critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; and have made substantial contributions to the statistical analysis, obtaining funding, administrative, technical or material support, or supervision of the project. More specifically, these authors have each contributed to: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Investigation, Resources, Writing - Original Draft, and Writing - Review & Editing.

The members of the WH-PBRN-CIH Writing Group are Bevanne Bean-Mayberry MD, MHS; Sudha Bhoopalam MD; Kelly E. Buckholdt PhD; Deborah DiNardo MD, MS; Kathleen Bronson Dussán MD; Lisa Hardman RN, DNP; Elizabeth E. Hill PhD, RN; Tahira Juiris MD, MPH; Denise Koutrouba MS, BSN, PH, WHNP-BC; Kristin Mattocks PhD; Gina G. Rawson DNP, RN, APRN-bc; Jeanette Rylander MD; Anne G. Sadler PhD; Agnes Santiago-Cotto MSW; Divya Singhal MD, FAAN; and Ishita Thakar MD, FACP. All group members, BBM, SB, KB, KD, DD, LH, EH, TJ, DK, KM, GR, JR, AS, ASC, DS, and IT certify that they have participated sufficiently in the work to take public responsibility for part of the content; have made substantial contributions to the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of the data; have made substantial contributions to the critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; have made substantial contributions to the administrative, technical or material support, and worked to obtain local regulatory approvals, train staff, monitor project implementation, and disseminate findings. More specifically, these group authors have each contributed to: Conceptualization, Investigation, Resources, Writing - Review & Editing, and Project administration.

References

- 1.Atkins D, Kilbourne AM, Shulkin D. Moving from discovery to system-wide change: the role of research in a learning health care system: experience from three decades of health systems research in the veterans health administration. Annu Rev Publ Health. 2017;38:467–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grumbach K, Lucey CR, Johnston SC. Transforming from Centers of learning to learning health systems: the challenge for academic health Centers viewpoint. J Am Med Assoc. 2014;311(11):1109–1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Institute of Medicine. Best Care at Lower Cost: The Path to Continuously Learning Health Care in America. 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goldstein KM, Vogt D, Hamilton A, et al. Practice-based Research Networks Add Value to Evidence-Based Quality Improvement. Healthc (Amst); 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frayne S, Carney D, Bastian L, et al. The VA women’s health practice-based research Network: amplifying women veterans voices in VA research. J Gen Intern Med. 2013; 28(2):504–509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pomernacki A, Carney DV, Kimerling R, et al. Lessons from initiating the first veterans health administration (VA) women’s health practice-based research Network (WH-PBRN) study. J Am Board Fam Med. 2015;28(5):649–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Westfall JM, Zittleman L, Parnes B, et al. Card studies for observational research in practice. Ann Fam Med. 2011;9(1):63–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cole A, et al. Evaluating the development, implementation and dissemination of a multisite card study in the WWAMI region practice and research Network. Clin Transl Sci. 2015;8(6):764–769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Taylor SL, Herman PM, Marshall NJ, et al. Use of complementary and integrated health: a retrospective analysis of U.S. Veterans with chronic musculoskeletal pain nationally. J Alternative Compl Med. 2019;25(1):32–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Taylor SL, Bolton R, Huynh A, et al. What should health care systems consider when implementing complementary and integrative health: lessons from veterans health administration. J Alternative Compl Med. 2019;25(1):S52–S60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Evans EA, et al. Gender differences in use of complementary and integrative health by U.S. Military veterans with chronic musculoskeletal pain. Wom Health Issues. 2018;28(5):379–386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vanneman ME, Larson MJ, Chen C, et al. Treatment of low back pain with opioids and nonpharmacologic treatment modalities for army veterans. Med Care. 2018;56(10):855–861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ezeji-Okoye SC, Kotar TM, Smeeding SJ, Durfee JM. State of care: complementary and alternative medicine in veterans health administration-2011 survey results. Fed Pract. 2013;30(11):14–19. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Comprehensive Addition and Recovery Act (CARA) of 2016. 2016:1–15. TITLE IX–DEPARTMENT of PATIENTS AFFAIRS. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abraham TH, Finley EP, Drummond KL, et al. A method for developing trustworthiness and preserving richness of qualitative data during team-based analysis of large data sets. Am J Eval. August 2020. 10.1177/1098214019893784. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.