Abstract

Background:

Dopamine neuron firing in the ventral tegmental area (VTA) and dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens have been implicated in reward learning. Ethanol is known to increase both dopamine neuron firing in the VTA and dopamine levels in the nucleus accumbens. Despite this, some discrepancies exist between the dose of ethanol required to enhance firing in vivo and ex vivo. In the present study we investigated the effects of peripheral dopamine 2 subtype receptor antagonism on ethanol’s effects on dopamine neurotransmission.

Methods:

Plasma catecholamine levels were assessed following ethanol administration across four different doses of EtOH. Microdialysis and voltammetry were used to assess the effects of domperidone pretreatment on ethanol-mediated increases in dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens. A place conditioning paradigm was used to assess conditioned preference for ethanol and whether domperidone pretreatment altered this preference. Open-field and loss-of-righting reflex paradigms were used to assess the effects of domperidone on ethanol-induced sedation. A rotarod apparatus was used to assess the effects of domperidone on ethanol-induced motor impairment.

Results:

Domperidone attenuated ethanol’s enhancement of mesolimbic dopamine release under non-physiological conditions at intermediate (1.0 and 2.0 g/kg) doses of ethanol. Domperidone also decreased EtOH-induced sedation at 2.0 g/kg. Domperidone did not alter ethanol conditioned place preference nor did it affect ethanol-induced motor impairment.

Conclusions:

These results show that peripheral dopamine 2 receptors mediate some of the effects of ethanol on nonphysiological dopamine neurotransmission, although these effects are not related to the rewarding properties of ethanol.

Keywords: domperidone, dopamine, dopamine 2 receptor, ethanol, microdialysis

INTRODUCTION

Alcohol use disorder (AUD) is a debilitating condition with severe health, social, and economic effects for the affected individuals (Rehm & Shield, 2019; Vigo et al., 2020). As with many drugs of abuse, ethanol (EtOH) enhances dopamine (DA) levels in the nucleus accumbens (NAc; Boileau et al., 2003; Di Chiara & Imperato, 1985; Yim & Gonzales, 2000) and DA neuron firing rate in the ventral tegmental area (VTA; Brodie et al., 1990; Gessa et al., 1985). Although EtOH enhances the firing rate of VTA DA neurons both in vivo and ex vivo, EtOH enhances the firing rate of VTA DA neurons at much lower concentrations in vivo (ED50 = 162 mg/kg, iv; Gessa et al., 1985) than ex vivo (EC50 = 98 mM; Brodie et al., 1990). This disparity occurs despite EtOH exerting a weak direct effect on VTA DA neurons (Brodie et al., 1999; Koyama et al., 2007), albeit at concentrations higher than those required for a maximal effect in vivo. Many plausible explanations for the observed differences in the potency of EtOH in vivo and ex vivo exist, including the heterogeneity of VTA DA neurons (Doyon et al., 2021; Mrejeru et al., 2015), the potential for downregulation of various ion channels during slice preparation (Park et al., 2003; You et al., 2019), and the loss of relevant inputs ex vivo (Dunn, 1992; Fernandes et al., 2020; Han et al., 2018; Oliveira-Maia et al., 2011; Petrulli et al., 2017).

In addition to the direct effects of EtOH on VTA DA neurons, EtOH exerts indirect effects on VTA DA neurons. We have shown that gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) neurons in the VTA are highly sensitive to EtOH, which drives inhibition of VTA GABA neurons (Steffensen et al., 2009, 2018; Williams et al., 2018). This, in turn, results in disinhibition of VTA DA neurons and augmented DA levels in the NAc (Xiao et al., 2007).

One potential mediator of some indirect effects of EtOH on DA neurons and DA release is peripherally expressed dopamine 2-like receptors (D2Rs). In addition to being expressed in the brain, D2Rs are expressed in the periphery (McKenna et al., 2002; Missale et al., 1998), where they play a key role in regulating processes, such as immunity (Besser et al., 2005; Kawano et al., 2018), blood pressure (von Essen et al., 1980; Lokhandwala & Barrett, 1982), renal function (Armando et al., 2011; Carey et al., 1990), and gastric motility (Nagahata et al., 1995; Van Nueten & Schuurkes, 1984). Additionally, peripheral D2R expression is markedly altered in diseases related to aberrant central DA function, such as schizophrenia (Bondy et al., 1985; Ilani et al., 2001), restless legs syndrome (Mitchell et al., 2018), Parkinson’s Disease (Nagai et al., 1996), and addiction (Ersche et al., 2011). Although it is currently unknown whether these alterations are causally related to the underlying disease state, it has been demonstrated that these alterations are correlated with symptom severity (Brito-Melo et al., 2012; Cui et al., 2015; Ersche et al., 2011; Kustrimovic et al., 2016).

In light of the role of EtOH as a well-known enhancer of plasma catecholamine levels (Eisenhofer et al., 1983; Kovacs et al., 2002; Spaak et al., 2008) and findings that peripherally administered DA enhances mesolimbic DA levels (de Souza Silva et al., 2008), we assessed whether activation of peripheral D2Rs following EtOH administration contributes to its enhancement of NAc DA levels. We evaluated if domperidone (DOM), a peripheral D2R antagonist, could attenuate EtOH-mediated enhancement of mesolimbic DA levels. We hypothesized that by antagonizing peripheral D2Rs, the magnitude of EtOH-mediated enhancement of DA release in the NAc would be decreased. We also hypothesized that this reduction would not result from a change in the amount of DA released during phasic activation of VTA DA neurons. Furthermore, it was anticipated that EtOH-induced sedation would be potentiated by DOM pretreatment, while the effects of EtOH on motor coordination would be unaltered. Finally, it was predicted that conditioned place preference (CPP) for EtOH would be attenuated by DOM pretreatment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animal subjects

Male Wistar rats weighing more than 260 g from a breeding colony at Brigham Young University were used for these studies (Table 1). All rats were socially housed and given ad libitum access to food and water. The lighting in the housing room was maintained on a 12-h ON/12-h OFF light/dark cycle, and the temperature and humidity were controlled. All experimental procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees at Brigham Young University and Daegu Haany University and carried out in accordance with NIH guidelines.

TABLE 1.

Summary of animal use

| Experiment | Number of rats | Notes |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Plasma catecholamines | 30 | 6/group (VEH, EtOH 0.5, 1.0, 2.0, 4.0 g/kg, ip) |

| Microdialysis—EtOH | 40 | No more than four doses of EtOH/rat |

| Microdialysis—D2Rs | 9 | Each rat received VEH, ETIC, DOM |

| Voltammetry—EtOH versus VEH | 27 | |

| Voltammetry—EtOH & D2Rs | 27 | Nine rats/group (VEH, ETIC, DOM) |

| Voltammetry—DOM versus ETIC | 9 | |

| Place conditioning | 90 | |

| Open-field & motor coordination | 17 | |

| Loss of righting reflex | 28 | 14 rats/group (VEH, DOM). Rats previously underwent CPP and were selected only from EtOH naïve groups. |

| Total | 249 | |

Note: This table contains a breakdown of the number of animals used in each portion of this study and any important notes about their use.

Drugs and chemicals

Domperidone (Alfa Aesar) was mixed in a solution of 0.02% acetic acid and gently heated until fully dissolved. (−)-Eticlopride hydrochloride (Sigma-Aldrich) was prepared by dissolving in a solution of 0.9% sodium chloride. Vehicle (VEH) consisting of either 0.02% acetic acid in 0.9% sodium chloride or saline alone was used as controls for DOM and eticlopride (ETIC) injections, respectively. Each of these drugs was injected at a volume of 1 ml/kg. EtOH was diluted to 16% w/v using 0.9% sodium chloride and injected at volumes of 3.1 to 25 ml/kg depending on the dose of EtOH being administered.

Surgical procedure

Subjects were implanted with a guide cannula (Bioanalytical Systems Incorporated [BASI]) in the NAc at the following coordinates from bregma: +1.7 mm AP, +0.8 mm ML, and −6.0 mm DV. Subjects were anesthetized for the duration of the procedure using isoflurane (1.5% to 2.0%) and were allowed to recover for 1 week post surgery. Post-operative care consisted of buprenorphine (0.01 to 0.05 mg/ kg, ip) bis in die for 48 h and daily carprofen (2 mg [approximately 6.5 mg/kg]; Bio-Serv) in an edible tablet for 1 week beginning 2 days prior to surgery.

Microdialysis and high-performance liquid chromatography

On the test day, the rats were briefly anesthetized using isoflurane (4%), and microdialysis probes (BASI) extending 2 mm beyond the end of the guide cannula were inserted into the NAc. Artificial cerebral spinal fluid (aCSF) containing 148 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 1.2 mM CaCl2, and 0.85 mM MgCl2 (final pH 7.4 by phosphoric acid) was perfused through the probe at a rate of 2.0 μl/min. During the baseline period, microdialysis samples were collected and analyzed every 20 min until a stable baseline was established. Upon collection, dialysate samples were immediately loaded into a refrigerated (4°C) autosampler tray for analysis. Samples (38.5 μl) were then injected into the HPLC system for analysis within 10 min of being collected, allowing for rapid determination of extracellular DA levels. The minimum amount of time required to obtain a stable baseline signal was 3 h, with some subjects requiring additional time. While 3 h may seem like insufficient time to establish a stable baseline, it is consistent with the procedures used by several other research groups (Jang et al., 2008; Karkhanis et al., 2016; Zapata et al., 2009). After obtaining a stable baseline signal, vehicle (VEH; 1 ml/kg, i.p.) or DOM (1 mg/kg, ip) was injected 10 min prior to administration of EtOH (0.5 to 4.0 g/kg, i.p.). Dialysate samples were then collected and analyzed every 20 min for an additional 3 h. In a set of control experiments, VEH (1 ml/kg, i.p.), DOM (1 mg/kg, i.p.), or ETIC (1 mg/kg, i.p.) was administered after obtaining a stable baseline and data collection was continued for an additional 3 h.

Determination of the DA content in the dialysate was performed using a high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) pump (Ultimate 3000, Dionex) connected to a coulometric detector (Coulochem III, ESA). The coulometric detector included a guard cell (5020, ESA) set at +275 mV, a screen electrode (5014B, ESA) set at −100 mV, and a detection electrode (5014B, ESA) set at +220 mV. Dopamine was separated using a 4.6 × 80 mm C18 reverse phase column (3 μm particle size; HR-80, Thermo Fisher Scientific). The mobile phase containing 90 mM NaH2PO4, 50 mM citric acid, 1.7 mM 1-octanesulfonic acid, 50 μM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, 10% v/v acetonitrile, and 0.3% v/v triethylamine (final pH 3.0 by phosphoric acid) was pumped through the system at a flow rate of 0.5 ml/min. The detection limit for DA using this setup was 620 pM. External standards (in nM: 1, 10, and 100) were assayed concurrently with the samples, allowing for the construction of a calibration curve using Chromeleon. This curve was then used to provide estimates of the DA concentration in the samples. Dopamine levels following drug administration were expressed as a percentage of the baseline DA levels. Baseline DA levels were computed as the average DA concentration of a minimum of three consecutive stable collections occurring prior to drug administration (defined as three collections within 10% of the moving average of the last three collections).

Fast scan cyclic voltammetry

Electrically evoked DA release in the NAc was measured by fast scan cyclic voltammetry (FSCV) in isoflurane-anesthetized rats (1.5% to 2.0%). Using a stereotaxic apparatus (David Kopf), a bipolar stainless steel–coated stimulating electrode was inserted into the medial forebrain bundle (MFB; from bregma: −2.5 mm AP, +1.9 mm ML, and −8.0 to −8.2 mm DV) and a carbon fiber electrode was inserted into the NAc (from bregma: +1.6 mm AP, +1.9 mm ML, and −6.5 to −7.2 mm DV). The MFB underwent biphasic electrical stimulation (4 ms pulses, 60 pulses, 500 μA, 60 Hz) at 2-min intervals. Dopamine levels were monitored until achieving a minimum of five consecutive stable collections (five collections within 10% of the moving average of the last five collections). Once the signal had stabilized, VEH (1 ml/kg, ip), DOM (1 mg/kg, ip), or ETIC (1 mg/kg, ip) were administered followed by EtOH (2.0 g/kg, ip) 10 min later. Collections then continued for an additional 30 min. Baseline DA release was calculated using the final three collections of the baseline. The baseline was then updated following the first drug injection period (VEH or DOM) using the final three collections of this period. As ETIC enhanced phasic DA release, on trials where ETIC administration preceded EtOH administration, the stimulating current was reduced sufficiently to return the DA signal to its baseline level prior to administration of EtOH. The effects of the first drug injection on DA release were expressed as a percentage of the baseline from the baseline period. The effects of the second drug injection on DA release were expressed as a percentage of the updated baseline computed following the first drug injection. In a separate set of experiments, DOM (1 mg/kg, ip) was administered after a stable baseline was attained, and then ETIC (1 mg/kg, ip) was administered 1 h following the administration of DOM. Collections continued for an additional hour following ETIC administration. At a later date, this experiment was repeated with only DOM (5 mg/kg, ip), but no ETIC. All data were analyzed for drug effects using the average of the final three collections for each drug injected. Recordings were performed and analyzed using custom LabVIEW–based (National Instruments) software (Yorgason et al., 2011). All other equipment and recording parameters were as described previously (Jang et al., 2017).

Measurement of plasma catecholamines

To determine the effect of EtOH on plasma catecholamine levels, subjects were anesthetized using isoflurane (1.5% to 2.0%) and implanted with an intravenous catheter in the jugular vein. Subjects were then placed on a stereotaxic apparatus, and a microdialysis probe was inserted into the NAc (from bregma: +1.7 AP, +0.8 ML, and −8.0 DV). Microdialysis was performed as described above with the only difference being that the rat was anesthetized as opposed to awake. Blood (800 μl/sample) was drawn via the intravenous catheter with fluid replacement (heparinized Ringer’s solution). Blood draws occurred 5 min prior to injection with EtOH as well as 10, 20, 30, 60, 120, and 180 min following administration of EtOH. These samples were processed as previously described (Yang et al., 2002) and analyzed using the HPLC system described earlier. The mobile phase for this analysis consisted of 97 mM NaH2PO4, 31 mM Na2HPO4, 2.8 mM 1-octanesulfonic acid, 171 μM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, and 12% v/v methanol with a flow rate of 0.5 ml/min.

EtOH place conditioning

The place conditioning apparatus consisted of a 32″ × 16″ × 16″ plexiglass box subdivided into two 16″ × 16″ × 16″ compartments by a guillotine door. The apparatus was housed inside a sound attenuating cubicle. The two compartments were distinguished by a rough acrylic floor inside one compartment and a smooth plexiglass floor inside the other. Both floors were suspended off the base of the apparatus by 1″ with a piezoelectric sensor mounted in the center of the floor. The signal from the piezoelectric transducer was amplified (10×) and filtered (0.1 to 50 Hz) using a CyberAmp 820 amplifier (Molecular Devices, LLC.). This signal was then digitized at 100 Hz using a National Instruments board on a PXI-1011 chassis connected to a Windows PC (Microsoft). Piezoelectric signals were analyzed using custom software to determine how much time each rat spent in each chamber.

The place conditioning paradigm consisted of four phases: habituation, pre-test, conditioning, and post-test. During habituation, the subjects were allowed to explore the apparatus for 20 min. The pretest phase consisted of two 20-min trials given over 2 days in which the guillotine door was removed, and subjects explored the apparatus. Initial preference was recorded and averaged over the two pretest sessions. The conditioning phase consisted of six trials pairing VEH (1 ml/kg, ip), DOM (1 mg/kg, ip), VEH + EtOH (1.0 g/kg or 2.0 g/kg, ip), or DOM + EtOH (1.0 g/kg or 2.0 g/kg, ip) in one chamber (randomly assigned) and six trials pairing VEH with the other chamber. These trials were given over 12 days with each trial lasting 20 min. The EtOH and isovolumic VEH injections were given 10 min before the subjects were placed in the apparatus. The pretreatment injections (DOM or VEH) were given 10 min before the EtOH injections. The posttest phase consisted of one posttest trial lasting 40 min on the day after the final conditioning trial. A CPP score (posttest time on CS + floor − pretest time on CS + floor) was computed for each rat. The units of the posttest score were expressed in standardized units of s/min.

EtOH induced sedation and motor coordination

Prior to commencing open field testing for locomotor activity, all rats were trained to remain on a rotarod apparatus for 300 s at a fixed speed of 14 rpm. Locomotor activity was measured in the same apparatus as was used for place conditioning. Animals received one 30-min habituation session prior to the first experimental session. All animals were tested in the chamber with the smooth floor with the guillotine door in place. Piezoelectric signals were analyzed for locomotor activity by calculating the root mean square using Igor Pro 7 (Wavemetrics, Inc.). Locomotor trials lasted for 30 min. All subjects received injections of VEH (1 ml/kg, ip), DOM (1 mg/kg, ip), and ETIC (1 mg/kg, ip) followed by injections of VEH and EtOH (0.5 to 2.0 g/kg, ip). Rats were immediately placed into the chamber following the injection. Baseline locomotor activity was calculated using the average of three test sessions in which VEH was administered, with one session coming at the beginning of the experiment, one at the half-way point, and one at the end. The order of the injections was randomized with a minimum of 2 days between injections. Upon completion of each open field session, the rats were placed on a rotarod, and latency to fall was measured with experimental parameters as previously described (Steffensen et al., 2011).

Additionally, the loss of righting reflex was measured by in-jecting rats with VEH (1 ml/kg, ip) or DOM (1 mg/kg, ip) followed by EtOH (4.0 g/kg, ip). After the injection, the rats were placed in a holding cage until they lost the ability to right themselves. Once this occurred, the rats were placed on their back in the open-field chamber until recovery of the righting reflex (defined as being able to right themselves twice within a 30-s period). The time from the loss of the righting reflex to its recovery was measured and recorded for each rat.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using Stata 15.1 (StataCorp LLC.). All data were assessed for normality (Shapiro–Wilk test) and checked for outliers (IQR method) prior to analysis. All data were analyzed using ANOVAs or an appropriate nonparametric test as indicated. Between-subject factors included the following: dose (of EtOH) and drug (pretreatment condition). Within-subjects factors included the following: time, dose (locomotor activity and rotarod only), and drug (locomotor activity and rotarod only). All analyses included all relevant factors. A Greenhouse–Geisser correction for sphericity was applied to the results for all within-subjects factors. Planned comparisons to determine the effects of DOM and ETIC were conducted using Dunnett’s test with the VEH treated condition as the control. Post hoc comparisons were corrected for family-wise error rate using the Bonferroni correction. All values reported are mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was assessed at p < 0.05.

RESULTS

Effects of EtOH on plasma catecholamine levels

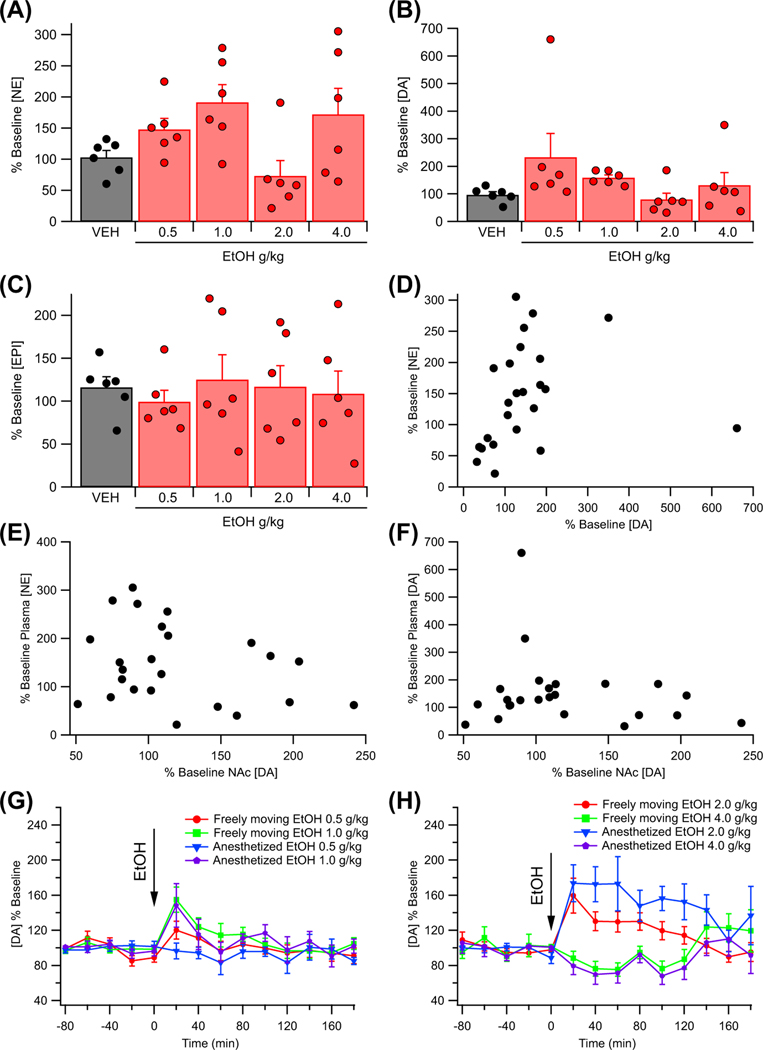

Plasma DA, EPI, and NE levels were analyzed in 30 male rats (six rats per dose) following administration of VEH (0.9% NaCl, ip) or EtOH (0.5 to 4.0 g/kg, ip). Dopamine, EPI, and NE levels over the first 30 min post injection were averaged and compared between treatment conditions using a Kruskal–Wallis test as 10% of the data were classified as outliers using the IQR method. Plasma NE (H(4) = 11.54, p = 0.021) and DA (H(4) = 12.51, p = 0.014) levels were found to be affected by EtOH administration within the first 30 min post injection, while EPI levels (H(4) = 0.95, p = 0.688) were not (Figure 1A–C). One-way ANOVAs revealed no difference between treatment groups in baseline plasma NE, F (4, 25) = 0.59, p = 0.673; baseline plasma concentrations in nM: VEH 1.47 ± 0.20; EtOH 0.5 g/kg 1.61 ± 0.20; EtOH 1.0 g/kg 1.84 ± 0.22; EtOH 2.0 g/kg 1.83 ± 0.21; EtOH 4.0 g/kg 1.80 ± 0.24, EPI, F (4, 25) = 0.57, p = 0.687; baseline plasma concentrations in nM: VEH 0.96 ± 0.13; EtOH 0.5 g/kg 0.84 ± 0.13; EtOH 1.0 g/kg 0.94 ± 0.15; EtOH 2.0 g/kg 1.05 ± 0.03; EtOH 4.0 g/kg 0.85 ± 0.11, or DA, F (4, 25) = 0.22, p = 0.923; baseline plasma concentrations in nM: VEH 1.01 ± 0.15; EtOH 0.5 g/kg 1.07 ± 0.20; EtOH 1.0 g/kg 0.87 ± 0.18; EtOH 2.0 g/kg 1.04 ± 0.16; EtOH 4.0 g/kg 0.95 ± 0.16, levels.

FIGURE 1.

Effects of EtOH on plasma catecholamines. (A) EtOH produced a dose-dependent increase in the levels of plasma norepinephrine (NE) within the first 30 min following administration. (B) EtOH produced a dose-dependent increase in the levels of plasma dopamine (DA) within the first 30 min following administration. (C) EtOH did not alter plasma epinephrine (EPI) levels within the first 30 min following administration. (D) Graph of the relationship between plasma NE and plasma DA levels within the first 30 min following EtOH administration. Plasma NE and plasma DA were found to be significantly correlated (rs = 0.47). (E) Graph of the relationship between changes in plasma NE and nucleus accumbens (NAc) DA during the first 40 min following EtOH administration. (F) Graph of the relationship between changes in plasma DA and NAc DA during the first 40 min following EtOH administration. Baseline plasma NE concentrations are as follows: (in nM): VEH 1.47 ± 0.20; EtOH 0.5 g/kg 1.61 ± 0.20; EtOH 1.0 g/kg 1.84 ± 0.22; EtOH 2.0 g/kg 1.83 ± 0.21; EtOH 4.0 g/kg 1.80 ± 0.24. Baseline plasma EPI concentrations are as follows: (in nM): VEH 0.96 ± 0.13; EtOH 0.5 g/kg 0.84 ± 0.13; EtOH 1.0 g/kg 0.94 ± 0.15; EtOH 2.0 g/kg 1.05 ± 0.03; EtOH 4.0 g/kg 0.85 ± 0.11. Baseline plasma DA concentrations are as follows: (in nM): VEH 1.01 ± 0.15; EtOH 0.5 g/ kg 1.07 ± 0.20; EtOH 1.0 g/kg 0.87 ± 0.18; EtOH 2.0 g/kg 1.04 ± 0.16; EtOH 4.0 g/kg 0.95 ± 0.16. (G) Graph showing the effect of 0.5 g/kg, ip and 1.0 g/kg, ip EtOH on DA levels in the NAc in both anesthetized and freely moving rats. (H) Graph showing the effect of 2.0 g/kg, ip and 4.0 g/kg, ip EtOH on DA levels in the NAc in both anesthetized and freely moving rats. Baseline microdialysis DA concentrations (in nM): isoflurane 16.7 ± 5.5; freely-moving 14.0 ± 3.0

An exploratory analysis using Spearman’s rank order correlation revealed that plasma DA levels were significantly positively correlated with plasma NE levels (rs = 0.47, p = 0.020, n = 24; Figure 1D). Additional exploratory analyses using Spearman’s rank order correlation did not indicate a significant correlation between DA levels in the NAc and plasma NE levels (rs = −0.22, p = 0.310, n = 24) or plasma DA levels (rs = 0.02, p = 0.933, n = 24) during the first 40 min following EtOH administration (Figure 1E,F).

Exploratory analyses were conducted to compare baseline DA levels and the EtOH response under isoflurane with that obtained in awake, freely moving animals. Baseline NAc DA levels obtained under isoflurane anesthesia were broadly similar to those obtained from awake, freely-moving rats (t(152) = 0.02, p = 0.983; baseline DA concentrations in nM: isoflurane 16.7 ± 5.5; freely-moving 14.0 ± 3.0). A mixed-model ANOVA revealed no significant effects of isoflurane anesthesia on the DA response to EtOH, main effect isoflurane: F (1, 76) = 0.60, p = 0.440; isoflurane × dose: F (3, 76) = 1.74, p = 0.167; isoflurane × time: F (9, 678) = 0.30, p = 0.916; isoflurane × dose × time: F (27, 678) = 0.55, p = 0.915.

Effects of EtOH on mesolimbic dopamine dynamics as measured using fast scan cyclic voltammetry and microdialysis

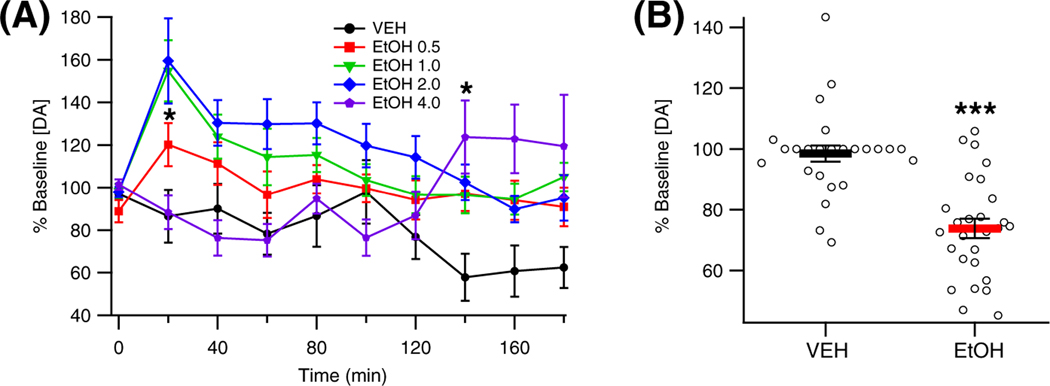

To determine the effect of EtOH on DA levels in the NAc, the rats were administered VEH (n = 9), or EtOH (0.5 g/kg, n = 15; 1.0 g/kg, n = 12; 2.0 g/kg, n = 24; 4.0 g/kg, n = 9), and DA levels were assessed by microdialysis. Analysis of the data revealed that EtOH enhanced DA levels in the NAc in a dose-dependent manner, F (4, 64) = 3.80, p = 0.008, partial η2 = 0.19 [0.02, 0.32] (Figure 2A). Dopamine levels changed over time post injection, F (9, 573) = 4.05, p = 0.001, partial η2 = 0.06 [0.02, 0.09], with the timing of changes varying based on the dose of EtOH administered, F (36, 573) = 2.62, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.14 [0.04, 0.14]. Specifically, the intermediate doses of EtOH (1.0 g/kg, 2.0 g/kg) enhanced DA levels in the NAc 20 min post injection (1.0 g/kg: t = 3.69, p = 0.010; 2.0 g/kg: t = 4.44, p < 0.001), while the largest dose of EtOH (4.0 g/kg) enhanced DA release later at 140 min post injection (t = 3.33, p = 0.037). Baseline DA levels [nM] were as follows: EtOH 0.5 g/kg 17.4 ± 3.5; EtOH 1.0 g/kg 10.3 ± 2.0; EtOH 2.0 g/kg 17.8 ± 3.5; EtOH 4.0 g/kg 10.7 ± 1.9.

FIGURE 2.

Effects of EtOH on dopamine (DA) release in the nucleus accumbens (NAc). (A) Effects of different doses of EtOH on DA release in the NAc as measured by microdialysis. (B) Effects of 2.0 g/kg EtOH on evoked phasic DA release in the NAc as measured by voltammetry. Asterisks * and *** denote significance levels p < 0.05 and p < 0.001, respectively. Baseline DA levels (nM): EtOH 0.5 g/kg 17.4 ± 3.5; EtOH 1.0 g/kg 10.3 ± 2.0; EtOH 2.0 g/kg 17.8 ± 3.5; EtOH 4.0 g/kg 10.7 ± 1.9

To determine the effect of EtOH on electrically evoked DA release in the NAc, 27 rats were administered VEH followed by EtOH (2 g/kg) while DA release was being assessed using FSCV. Analysis of the data using the Wilcoxon signed rank test indicated that EtOH administration decreased electrically evoked DA release in the NAc (z = 4.16, p < 0.001; Figure 2B).

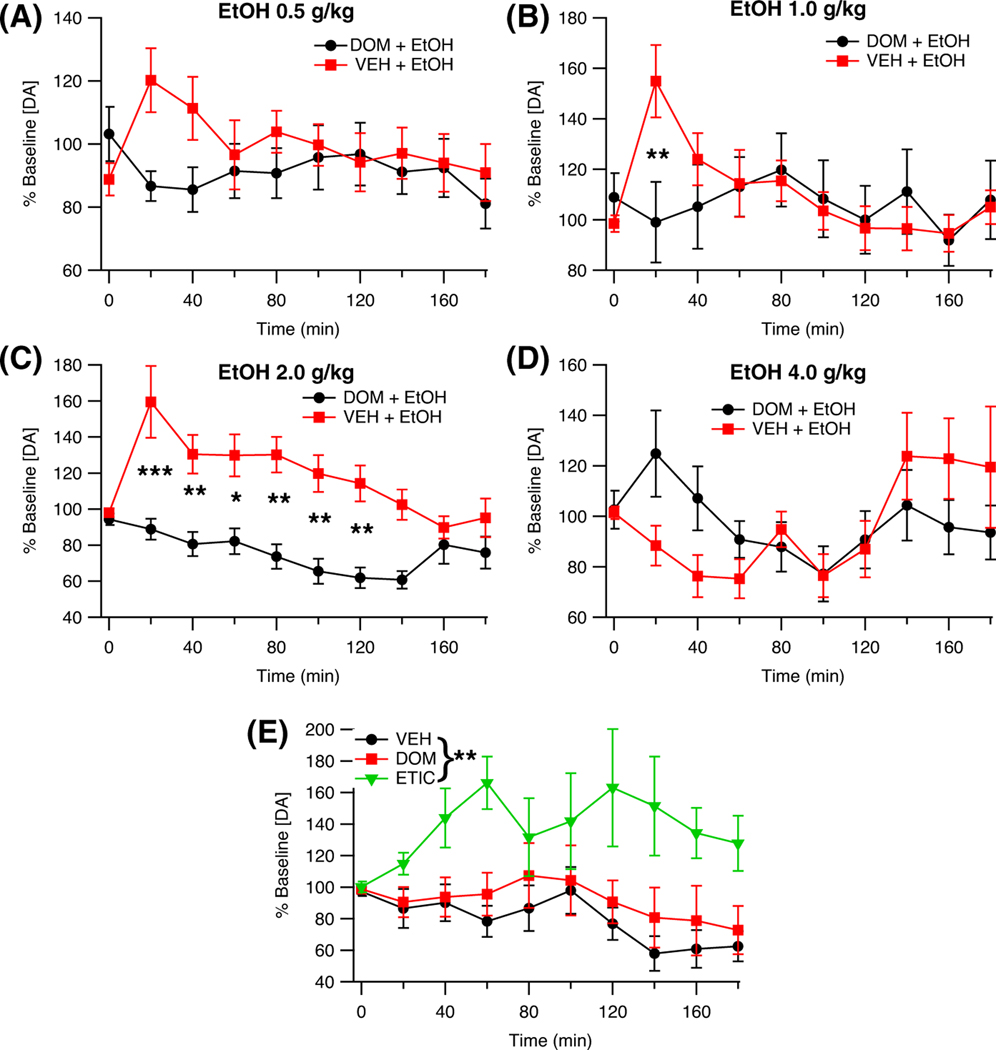

Effects of domperidone on EtOH-induced alterations in mesolimbic dopamine dynamics

Microdialysis was used to evaluate the effects of DOM pretreatment on DA release in the NAc following EtOH administration (DOM + EtOH 0.5 g/kg, n = 15; DOM + EtOH 1.0 g/kg, n = 13; DOM + EtOH 2.0 g/kg, n = 11; DOM + EtOH 4.0 g/kg, n = 12). Domperidone significantly attenuated EtOH enhancement of DA release, F (1, 103) = 6.74, p = 0.011, partial η2 = 0.06 [0.00, 0.17] (Figure 3A–D). The effect of DOM on DA release following EtOH administration was not found to be time-dependent, F (9, 918) = 1.83, p = 0.096, but it was dependent on the dose of EtOH administered, F (3, 103) = 3.86, p = 0.012, partial η2 = 0.10 [0.01, 0.20], and the interaction between time and EtOH dose, F (27, 918) = 2.09, p = 0.006, partial η2 = 0.06 [0.01, 0.06]. Notably, DOM reduced the magnitude of EtOH-enhanced DA release in the NAc 20 min after delivery of intermediate doses of EtOH (1.0 g/kg, 2.0 g/kg). A two-way ANOVA found that baseline DA levels did not differ between the treatment groups, Dose: F (3, 103) = 1.21, p = 0.309; DOM: F (1, 103) = 0.12, p = 0.727; Dose × DOM: F (3, 103) = 0.40, p = 0.755; baseline DA levels [nM]: EtOH 0.5 g/kg 17.4 ± 3.5; EtOH 1.0 g/kg 10.3 ± 2.0; EtOH 2.0 g/kg 17.8 ± 3.5; EtOH 4.0 g/kg 10.7 ± 1.9.; EtOH 0.5 g/kg + DOM 15.9 ± 4.0; EtOH 1.0 g/kg + DOM 12.1 ± 2.8; EtOH 2.0 g/kg + DOM 12.7 ± 3.9; EtOH 4.0 g/kg + DOM 11.9 ± 2.5.

FIGURE 3.

Effects of domperidone (DOM) pretreatment on EtOH induced increases in nucleus accumbens (NAc) dopamine (DA) levels as measured by microdialysis. (A) Time course of changes in NAc DA levels following EtOH (0.5 g/kg, ip) and pretreatment with vehicle (VEH) or DOM. (B) Time course of changes in NAc DA levels following EtOH (1.0 g/kg, ip) and pretreatment with vehicle (VEH) or DOM. (C) Time course of changes in NAc DA levels following EtOH (2.0 g/kg, ip) and pretreatment with vehicle (VEH) or DOM. (D) Time course of changes in NAc DA levels following EtOH (4.0 g/kg, ip) and pretreatment with vehicle (VEH) or DOM. (E) Time course of changes in NAc DA levels following administration of VEH (1 ml/kg, ip), DOM (1 mg/kg, ip), or eticlopride (ETIC, 1 mg/kg, ip). Baseline DA levels (nM): EtOH 0.5 g/ kg 17.4 ± 3.5; EtOH 1.0 g/kg 10.3 ± 2.0; EtOH 2.0 g/kg 17.8 ± 3.5; EtOH 4.0 g/kg 10.7 ± 1.9.; EtOH 0.5 g/kg + DOM 15.9 ± 4.0; EtOH 1.0 g/kg + DOM 12.1 ± 2.8; EtOH 2.0 g/kg + DOM 12.7 ± 3.9; EtOH 4.0 g/kg + DOM 11.9 ± 2.5; VEH 19.1 ± 5.4; DOM 11.6 ± 1.8; ETIC 16.9 ± 2.4. Asterisks *, **, and *** denote significance levels p < 0.05, p < 0.01, and p < 0.001, respectively

To control for possible effects of DOM on DA release, the effects of VEH, DOM, and ETIC (all n = 9) on DA release in the NAc were compared using microdialysis. An ANOVA revealed a main effect of treatment condition on DA release in the NAc, F (2, 24) = 7.37, p = 0.003, partial η2 = 0.38 [0.06, 0.57]. Planned analyses of the results showed that there was no effect of DOM on DA release, F (1, 24) = 2.31, p = 0.141 (Figure 3E). However, systemically active ETIC markedly enhanced DA release in the NAc, F (1, 24) = 55.70, p < 0.001. One-way ANOVA found that baseline DA levels did not differ between groups, F (2, 24) = 1.20, p = 0.319; baseline DA levels [nM]: VEH 19.1 ± 5.4; DOM 11.6 ± 1.8; ETIC 16.9 ± 2.4.

The role of D2Rs in EtOH-attenuated evoked DA release was probed using FSCV by administering DOM, ETIC, or VEH (all n = 9) 10 min prior to EtOH administration. Domperidone and ETIC, F (2, 24) = 0.31, p = 0.735, pretreatment did not affect EtOH-mediated decreases in evoked DA release in the NAc (Figure 4A,B).

FIGURE 4.

Effects of dopamine (DA) 2 receptor (D2R) antagonism on evoked phasic DA release as measured by fast scan cyclic voltammetry. (A) Effect of vehicle (VEH), domperidone (DOM), and eticlopride (ETIC) pretreatment on EtOH attenuation of evoked phasic DA release in the nucleus accumbens (NAc). (B) Averaged traces showing the DA response to VEH, DOM, ETIC, and EtOH over time. (C) Effects of VEH, DOM, and ETIC alone on evoked phasic DA release in the NAc. (D) Averaged traces showing the effects of DOM and ETIC on evoked phasic DA release in the NAc. (E) Comparison of the effects of DOM (1 mg/kg, ip) and DOM (5 mg/kg, ip) on evoked phasic DA release in the NAc. Asterisk * denotes significance level p < 0.05

To provide further evidence that DOM does not readily penetrate the blood–brain barrier (BBB), DOM was administered 1 h prior to ETIC administration in five rats, while evoked phasic DA release was measured in the NAc by FSCV. One-tailed t-tests revealed that DOM did not significantly alter baseline DA release (t(4) = 0.45, p = 0.662), whereas ETIC significantly increased DA release as compared with DOM (t(4) = −2.74, p = 0.026; Figure 4C,D). In a second set of animals (n = 4), an additional experiment was conducted to assess the ability of a higher dose of DOM (5 mg/kg, ip) to alter evoked phasic DA release in the NAc. Analysis of these data indicated that the higher dose of DOM did not significantly alter evoked phasic DA release in the NAc when compared with the lower dose (1 mg/kg, ip) of DOM (t(7) = 0.48, p = 0.646; Figure 4E).

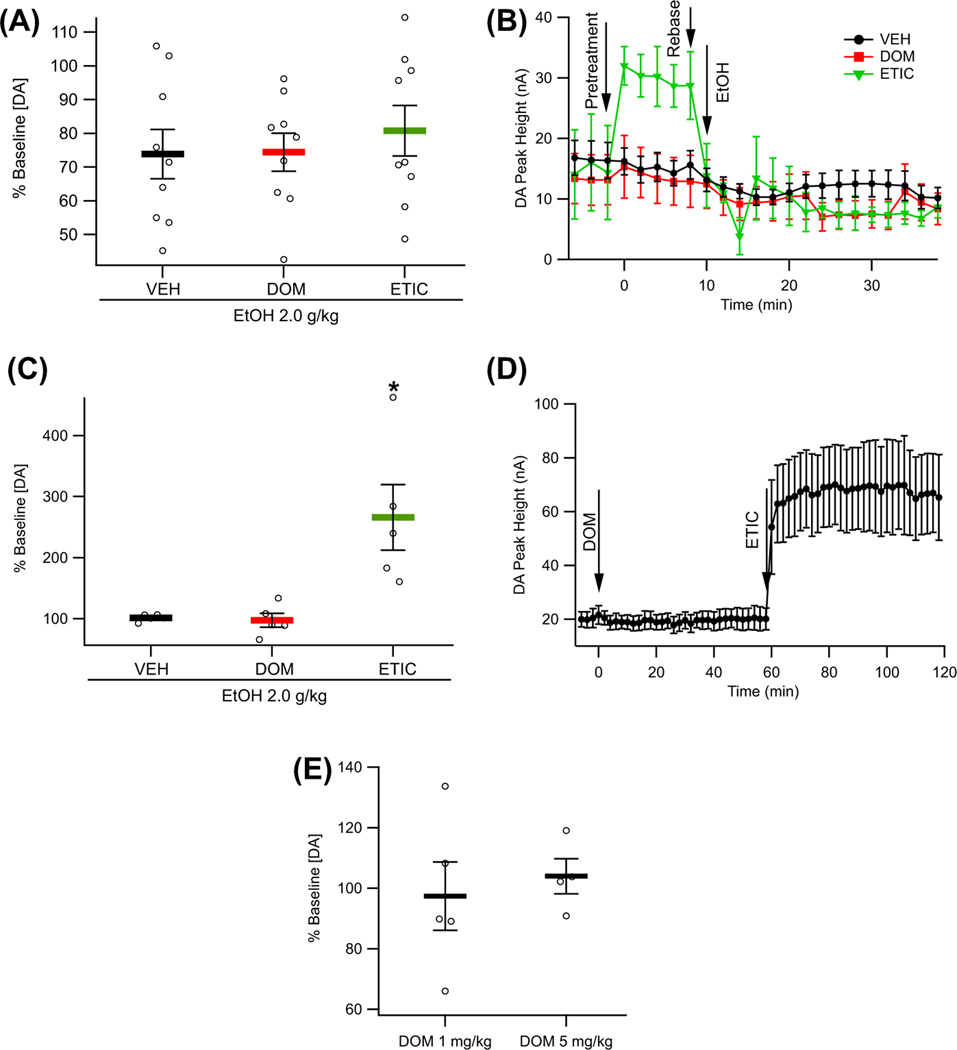

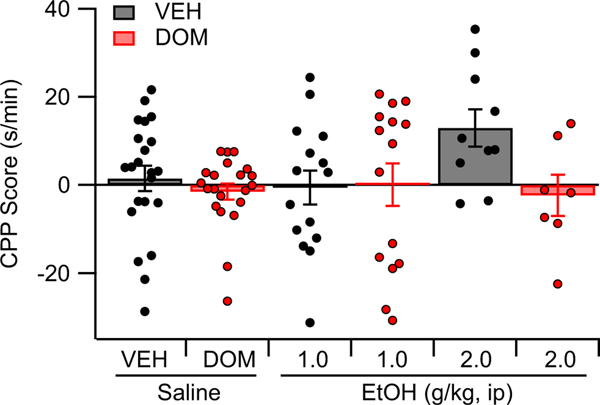

Effects of domperidone on EtOH CPP

A place conditioning paradigm was used to assess the role of peripheral D2Rs in EtOH place conditioning. Rats were assigned to one of six groups: VEH (n = 22), DOM (n = 21), VEH + EtOH (1.0 g/ kg, n = 15; 2.0 g/kg, n = 10), or DOM + EtOH (1.0 g/kg, n = 15; 2.0 g/kg, n = 7). Analysis of the data using two-way ANOVA revealed that DOM did not alter place preference, main effect DOM: F (1, 84) = 3.57, p = 0.062; interaction effect DOM × EtOH: F (2, 84) = 1.88, p = 0.156 (Figure 5).

FIGURE 5.

Effects of vehicle (VEH), domperidone (DOM), and EtOH on place preference

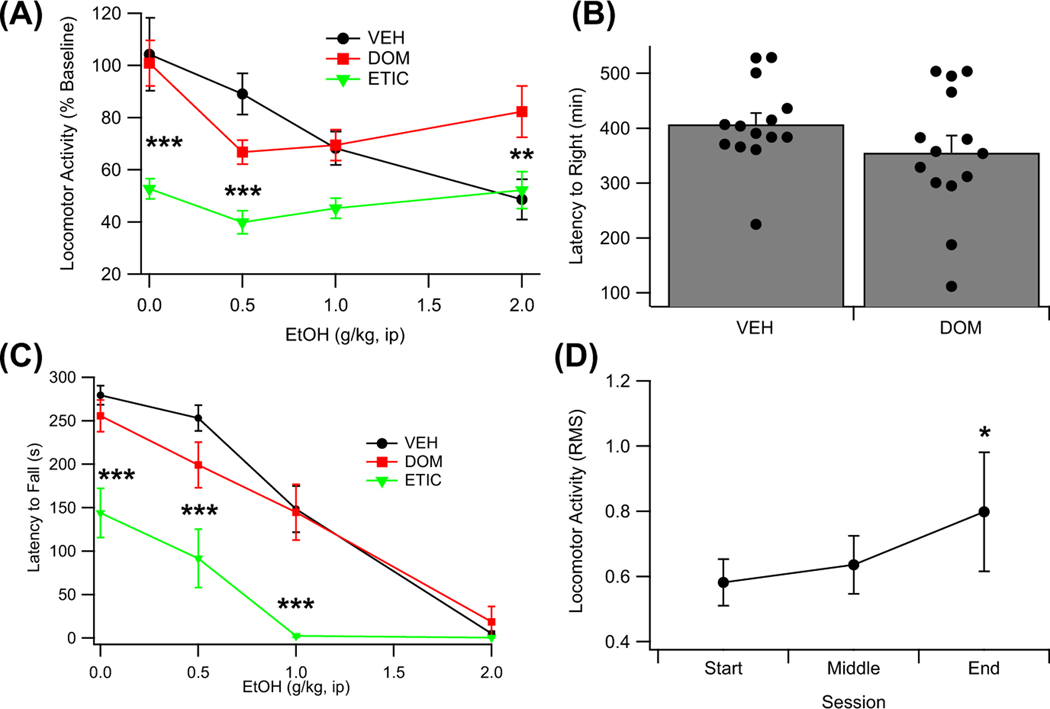

Effects of domperidone on EtOH induced sedation and motor coordination

Locomotor activity in an open-field apparatus was assessed in 17 rats across the following treatment conditions: VEH, VEH + EtOH (0.5 to 2.0 g/kg, ip), DOM, DOM + EtOH (0.5 to 2.0 g/kg, ip), ETIC, and ETIC + EtOH (0.5 to 2.0 g/kg, ip), with each rat receiving all treatments in a randomized order. Analysis of the data using a repeated measures ANOVA revealed that EtOH decreased locomotor activity in a dose-dependent manner, F (3, 48) = 6.26, p = 0.007, partial η2 = 0.28 [0.06, 0.43] (Figure 6A). Locomotor activity was also found to be dependent on the treatment condition, F (2, 32) = 23.59, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.60 [0.33, 0.71], and on an interaction between the treatment condition and dose of EtOH administered, F (6, 96) = 4.60, p = 0.019, partial η2 = 0.22 [0.05, 0.32]. A planned analysis of the data revealed that ETIC alone (t(32) = −6.12, p < 0.001), but not DOM alone (t(32) = 0.46, p < 0.856), decreased locomotor activity. A post hoc analysis conducted to better understand the interaction between treatment condition and dose of EtOH revealed that DOM was protective against the sedating effects of a larger dose of EtOH (2.0 g/kg; t(96) = 3.43, p = 0.007).

FIGURE 6.

Effects of eticlopride (ETIC), domperidone (DOM), and vehicle (VEH) on EtOH (EtOH)-induced sedation and motor impairment. (A) Locomotor activity following EtOH over a range of doses (0.0 to 2.0 g/kg, ip) across three pretreatment conditions (ETIC, DOM, and VEH). (B) Effects of pretreatment with DOM on the latency to right following loss of the righting reflex due to administration of EtOH (4.0 g/kg, ip). (C) Latency to fall as measured using a rotarod following EtOH over a range of doses (0.0 to 2.0 g/kg, ip) across three pretreatment conditions (ETIC, DOM, and VEH). (D) Locomotor activity across the three baseline sessions. Overall locomotor activity in the chamber increased across the course of the 14 sessions. Asterisks ** and *** denote significance levels p < 0.01 and p < 0.001, respectively

Loss of righting reflex was assessed in 28 rats with EtOH (4 g/kg, ip) administration preceded by VEH (n = 14) or DOM (n = 14) injections. VEH-and DOM-pretreated animals did not significantly differ in their latency to right following EtOH administration (t(26) = 1.38, p = 0.179; Figure 6B).

Motor coordination was measured using a rotarod task in the same 17 rats as were used to assess locomotor activity. A repeated measures ANOVA revealed that EtOH impairs motor coordination in a dose-dependent manner, F (3, 48) = 59.77, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.79 [0.66, 0.84] (Figure 6C). The treatment condition was also found to impair motor coordination, F (2, 32) = 49.66, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.76 [0.57, 0.83], and to interact with the effects of EtOH on motor coordination, F (6, 96) = 4.92, p = 0.003, partial η2 = 0.24 [0.06, 0.33]. Planned analyses indicated that ETIC (t(32) = −9.11, p < 0.001), but not DOM (t(32) = −1.38, p = 0.290), impaired motor coordination. A post hoc analysis was completed to better understand the interaction between the dose of EtOH administered and the treatment condition. This analysis revealed that ETIC reduced motor coordination below the level seen with VEH pretreatment for every dose of EtOH administered, except 2 g/kg (VEH: t(96) = −5.52, p < 0.001; 0.5 g/kg: t(96) = −6.57, p < 0.001; 1.0 g/kg: t(96) = −5.94, p < 0.001; 2.0 g/kg: t(96) = −0.19, p = 1.000), likely indicating that the interaction is largely due to the floor effect achieved in this paradigm at a dose of 2.0 g/kg EtOH.

An exploratory analysis to determine whether baseline locomotor activity was stable over the 14 test sessions conducted using the data taken for computing the baseline locomotor activity. This analysis revealed that locomotor activity in the open-field compartment increased over the course of the 14 test sessions, F (2, 48) = 3.48, p = 0.039 (Figure 6D).

DISCUSSION

EtOH effects on plasma catecholamines and mesolimbic dopamine release

Although the effects of EtOH on plasma NE and EPI are well known, the effects of EtOH on plasma DA have been less well-studied. This study helps address this lack of knowledge by demonstrating three doses (0.5, 1.0, and 4.0 g/kg) at which acute EtOH enhances plasma DA. Previous studies using lower doses of EtOH had failed to demonstrate EtOH enhancement of plasma DA in humans (Spaak et al., 2008). Additionally, this study confirms previous findings that acute EtOH enhances plasma NE levels (Eisenhofer et al., 1983; Kovacs et al., 2002). Exploratory analyses indicated that the increased plasma DA and NE levels caused by EtOH may be interrelated, possibly indicating that the increased plasma DA levels result from enhanced NE release from sympathetic terminals. Interestingly, plasma EPI levels were not elevated within the first 30 min after EtOH administration in this study, despite evidence from previous studies indicating that EtOH enhances plasma EPI levels (Eisenhofer et al., 1983; Kovacs et al., 2002; Spaak et al., 2008). The discrepancy between the current study and previous studies may be related to the use of isoflurane as it is known to alter plasma catecholamines and may have interacted with EtOH to confound the results (Nishiyama, 2005; Yli-Hankala et al., 1993).

Microdialysis measurements of NAc DA levels indicated that DA levels in the NAc are enhanced by physiologically relevant doses of EtOH. These findings are broadly consistent with those of the previous body of work, showing that EtOH enhances DA levels in the NAc (Imperato & Di Chiara, 1986; Robinson et al., 2009; Yim et al., 2000). Furthermore, the results showing that EtOH decreased evoked phasic DA release in the NAc during electrical stimulation of the medial forebrain bundle are consistent with those previously shown (Schilaty et al., 2014; Yorgason et al., 2014).

Initially it may seem contradictory that the same dose of EtOH (2 g/kg) both enhanced NAc DA levels as measured by microdialysis and attenuated evoked phasic DA release in the NAc as measured by voltammetry. A potential explanation for this, however, is that the effects of EtOH on evoked phasic DA release largely reflect the presynaptic effects of EtOH, while not accounting for the effects of EtOH on VTA DA neuron firing as the stimulation of the medial forebrain bundle overrides this activity. As microdialysis integrates both the presynaptic effects of EtOH and the effects of EtOH on VTA DA neuron firing activity, the microdialysis data capture the increase in NAc DA levels caused by increased VTA DA neuron activity. In support of this interpretation, voltammetry studies measuring spontaneous rather than evoked DA release have shown increased frequency of DA release in the NAc following EtOH administration (Cheer et al., 2007; Robinson et al., 2009). Of note, the enhanced frequency of spontaneous events was not accompanied by changes in the amplitude of these events (Cheer et al., 2007). This finding is consistent with data showing that EtOH exerts a bidirectional effect on evoked, phasic release in the NAc, with low dose EtOH (0.1 g/kg) enhancing DA release (Pelkonen et al., 2010), while larger doses of EtOH inhibit evoked phasic release in the NAc (Budygin et al., 2001; Yorgason et al., 2014, 2021). As such, increasing inhibition of phasic DA release from the presynaptic terminal by increasing doses of EtOH may help explain why high doses of EtOH (5.0 g/kg) reduce DA levels in the NAc.

An exploratory analysis indicated that isoflurane did not alter baseline DA levels in the NAc. Although caution should be exercised in interpreting exploratory analyses, these results may be due to the concentration of isoflurane used to maintain anesthesia (1.5% to 2.0%) during these experiments, as previous research has indicated that high-dose isoflurane anesthesia (>2.5%) enhances mesolimbic DA release while low-dose (1%) isoflurane does not significantly affect mesolimbic DA release (Adachi et al., 2005, 2008). Furthermore, in our exploratory analysis, we did not find significant effects of isoflurane on EtOH-induced DA release. It should be noted, however, that the isoflurane group was underrepresented in the overall sample which could contribute to an inability to detect isoflurane-induced changes in DA dynamics following EtOH administration. A previous preliminary report had also suggested that changes in DA release following EtOH release can be detected in the presence of isoflurane anesthesia (Sullivan et al., 2011).

Effects of domperidone on EtOH-induced changes in dopamine neurotransmission

Pretreatment with DOM prior to administration of EtOH served to attenuate EtOH-induced increases in mesolimbic DA levels at moderate doses of EtOH (1.0 and 2.0 g/kg, ip). This finding supports the hypothesis that EtOH may exert effects on mesolimbic DA levels, in part, through a pathway involving peripheral D2Rs. The lack of correlation between plasma DA levels and NAc DA levels following EtOH administration, as well as the ability of DOM to attenuate EtOH enhancement of DA levels in the NAc, at doses of EtOH that enhanced NAc DA levels but did not alter plasma DA levels, suggest a complex relationship between activation of peripheral D2Rs and mesolimbic DA. It had been postulated that increases in plasma DA levels might be responsible for activating peripheral D2Rs and, thus, increasing mesolimbic DA levels through an uncharacterized signaling pathway. The current results suggest that this does not fully capture how peripheral D2Rs contribute to EtOH enhancement of mesolimbic DA levels. The inability of DOM alone to alter baseline DA levels in the NAc also suggests that there is minimal tone within this signaling pathway. The lack of change in NAc DA levels following DOM alone compared with the increase following the centrally available D2R antagonist ETIC alone is consistent with research indicating that DOM does not readily cross the BBB (Laduron & Leysen, 1979; Michiels et al., 1981). It is worth noting that the use of different doses of ETIC or alternative delivery strategies (e.g., infusion into the VTA) may have produced differing results with respect to the effects of ETIC on DA release in the NAc. In accordance with this, it is possible that by using a different dose of DOM, it would have been possible to induce increased DA release in the NAc, although to our knowledge, no reports exist of peripherally administered DOM enhancing mesolimbic DA release. When considering this hypothesis, it is worth noting that DOM (Ki approximately 0.54 nM) and ETIC (Ki approximately 0.41 nM) have similar affinities for D2Rs (Andersen et al., 1985; Hall et al., 1986; Imafuku, 1987; Kessler et al., 1993; Lawler et al., 1999; Lin et al., 1987; Sánchez-Roa et al., 1989; Sokoloff et al., 1990; Tang et al., 1994; Zahniser & Dubocovich, 1983), suggesting that the use of 1 mg/kg doses of both DOM and ETIC is not unreasonable for the purpose of comparing these two drugs. Interestingly, DOM failed to attenuate the delayed increase in mesolimbic DA levels observed after administration of 4.0 g/kg EtOH. This is notable as 4.0 g/kg EtOH produces blood EtOH concentrations similar to the EC50 for EtOH enhancement of DA neuron firing ex vivo. This finding highlights the complimentary nature of this study to what is already known about the effects of EtOH on DA neuron firing and DA release.

Neither DOM nor ETIC pretreatment altered the inhibitory effects of acute EtOH on electrically evoked DA release in the NAc. This finding is consistent with what was hypothesized and does not challenge the current understanding of how acute EtOH inhibits evoked DA release in the NAc (Feduccia et al., 2014; Schilaty et al., 2014; Yorgason et al., 2015). This finding is important as it indicates that the effects of DOM on DA levels in the NAc were not due to altered presynaptic effects of EtOH on DA terminals. Domperidone alone did not alter evoked DA release in the NAc following systemic administration; however, the centrally available ETIC did increase evoked DA release following peripheral administration, a finding that is consistent with the relative inability of DOM to cross the BBB.

Effects of domperidone on EtOH CPP

Domperidone did not affect preference for EtOH in an EtOH CPP paradigm. Domperidone also did not produce a place aversion or place preference on its own. These findings indicate that the portion of changes in NAc DA levels induced by EtOH that are affected by DOM pretreatment are likely related to locomotor activity, but not EtOH-mediated reward.

Effects of central and peripheral dopamine 2 receptor antagonism on EtOH-induced changes in locomotor activity and motor coordination

Eticlopride reduced locomotor activity on its own. In contrast, DOM alone did not alter locomotor activity, but DOM did attenuate the reduction in locomotor activity produced by 2.0 g/kg EtOH. More importantly, however, once the effects of central D2R antagonism were accounted for (the reduction in locomotor activity produced by ETIC alone), the dose-dependent interaction between EtOH and ETIC or DOM was highly similar for both ETIC and DOM (illustrated by the slope in Figure 6A). This suggests that the interaction between EtOH and ETIC or DOM is related to antagonism of peripheral D2Rs and not solely the result of antagonism of central D2Rs. The finding that centrally active D2R antagonists reduce locomotor activity both in the presence of EtOH (Pastor et al., 2005) and when administered alone (Collins et al., 2010) has been demonstrated previously. The latency to right following EtOH LORR was not attenuated by DOM pretreatment. This finding is consistent with the result of DOM effects on mesolimbic DA levels, indicating that the DOM is unable to significantly alter the effects of high-dose EtOH.

EtOH dose-dependently decreased motor coordination. Domperidone did not alter this effect either. Eticlopride alone decreased locomotor activity. Eticlopride also produced a significant interaction with the dose-dependent effects of EtOH on motor coordination. However, it is highly likely that this significant interaction is the result of a floor effect on the rotarod test (subjects cannot spend negative time on the apparatus), rather than a true interaction between the effects of ETIC and EtOH.

Limitations

Initially following microdialysis probe insertion, the measured DA is not reflective of physiological release. The degree to which the measured DA levels reflect physiological release increases over time with the rate at which this recovery occurs being at least partly dependent on the damage caused by insertion of the microdialysis probe (Osborne et al., 1990; Santiago & Westerink, 1990; Westerink & De Vries, 1988). While in this study a stable baseline was obtained after only a few hours, the time that elapsed between the insertion of the probe and the onset of the stable baseline was insufficient to ensure that the DA levels measured reflect only physiological DA release. As such, an important caveat limiting the interpretability of this research is that the DA levels reported in this study do not reflect physiological DA release, as illustrated by the relatively high baseline levels of NAc DA reported in this study (14 ± 3 nM), as compared with other microdialysis studies.

Another weakness in the experimental protocol was the use of only one dose of DOM (1 mg/kg, ip) for the manipulation of EtOH effects on mesolimbic DA levels. While we have demonstrated that DOM, and not VEH, is responsible for the observed changes, we have not addressed the efficacy or potency of DOM in attenuating EtOH-induced increases in NAc DA levels. The use of additional doses of DOM would have strengthened the argument for the ability of DOM to attenuate EtOH-induced mesolimbic DA release as well as clarified the range of doses at which DOM is effective. In part, this decision was made to allow for the study of the effects of DOM across a wider range of EtOH doses, as opposed to studying the effects of DOM at several doses on only a single dosage of EtOH. In a yet unpublished study, we have evaluated the dose-dependent effects of DOM on i.v. DA enhancement of NAc DA release, and the IC50 is about 0.01 mg/kg, iv.

CONCLUSION

The focus of this study was to determine whether antagonism of peripheral D2Rs would reduce EtOH-driven enhancement of NAc DA levels. It was found that DOM attenuates EtOH-induced enhancement of nonphysiological levels of NAc DA at intermediate EtOH doses (1.0 and 2.0 g/kg), while not influencing EtOH effects on nonphysiological DA neurotransmission at a higher dose (4.0 g/kg). Furthermore, pretreatment with DOM was protective against EtOH-induced sedation at a dose of 2.0 g/kg as well. This study did not find evidence for involvement of peripheral D2Rs in the conditioned rewarding effects of EtOH. These findings contribute to our understanding of how EtOH influences mesolimbic DA dynamics and provides support for the ability of EtOH to influence nonphysiological DA release through both direct and indirect actions on DA neurons. Finally, while the exact mechanism underlying the ability of DOM to attenuate EtOH effects on nonphysiological mesolimbic DA levels is yet to be elucidated, this study is an important first step in exploring a previously unstudied aspect of the peripheral effects of EtOH.

Acknowledgments

Funding information

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (Grant numbers AA020919 and DA035958) to SCS.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflict of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- Adachi YU, Yamada S, Satomoto M, Higuchi H, Watanabe K. & Kazama T. (2005) Isoflurane anesthesia induces biphasic effect on dopamine release in the rat striatum. Brain Research Bulletin, 67, 176–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adachi YU, Yamada S, Satomoto M, Higuchi H, Watanabe K, Kazama T. et al. (2008) Isoflurane anesthesia inhibits clozapine-and risperidone-induced dopamine release and anesthesia-induced changes in dopamine metabolism was modified by fluoxetine in the rat striatum: an in vivo microdialysis study. Neurochemistry International, 52, 384–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen PH, Grønvald FC & Jansen JA (1985) A comparison between dopamine-stimulated adenylate cyclase and 3H-SCH 23390 binding in rat striatum. Life Sciences, 37, 1971–1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armando I, Villar VA & Jose PA (2011) Dopamine and renal function and blood pressure regulation. Comprehensive Physiology, 1, 1075–1117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besser MJ, Ganor Y. & Levite M. (2005) Dopamine by itself activates either D2, D3 or D1/D5 dopaminergic receptors in normal human T-cells and triggers the selective secretion of either IL-10, TNFalpha or both. Journal of Neuroimmunology, 169, 161–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boileau I, Assaad JM, Pihl RO, Benkelfat C, Leyton M, Diksic M. et al. (2003) Alcohol promotes dopamine release in the human nucleus accumbens. Synapse (New York, N. Y.), 49, 226–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bondy B, Ackenheil M, Elbers R. & Frohler M. (1985) Binding of 3H-spiperone to human lymphocytes: a biological marker in schizophrenia? Psychiatry Research, 15, 41–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brito-Melo GE, Nicolato R, de Oliveira AC, Menezes GB, Lelis FJ, Avelar RS et al. (2012) Increase in dopaminergic, but not serotoninergic, receptors in T-cells as a marker for schizophrenia severity. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 46, 738–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodie MS, Pesold C. & Appel SB (1999) Ethanol directly excites dopaminergic ventral tegmental area reward neurons. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research, 23, 1848–1852. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodie MS, Shefner SA & Dunwiddie TV (1990) Ethanol increases the firing rate of dopamine neurons of the rat ventral tegmental area in vitro. Brain Research, 508, 65–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budygin EA, Phillips PE, Wightman RM & Jones SR (2001) Terminal effects of ethanol on dopamine dynamics in rat nucleus accumbens: an in vitro voltammetric study. Synapse (New York, N. Y.), 42, 77–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey RM, Siragy HM, Ragsdale NV, Howell NL, Felder RA, Peach MJ et al. (1990) Dopamine-1 and dopamine-2 mechanisms in the control of renal function. American Journal of Hypertension, 3, 59S–63S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheer JF, Wassum KM, Sombers LA, Heien ML, Ariansen JL, Aragona BJ et al. (2007) Phasic dopamine release evoked by abused substances requires cannabinoid receptor activation. Journal of Neuroscience, 27, 791–795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins LE, Galtieri DJ, Collins P, Jones SK, Port RG, Paul NE et al. (2010) Interactions between adenosine and dopamine receptor antagonists with different selectivity profiles: Effects on locomotor activity. Behavioral Brain Research, 211, 148–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui Y, Prabhu V, Nguyen TB, Yadav BK & Chung YC (2015) The mRNA expression status of dopamine receptor D2, dopamine receptor D3 and DARPP-32 in T lymphocytes of patients with early psychosis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 16, 26677–26686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Chiara G. & Imperato A. (1985) Ethanol preferentially stimulates dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens of freely moving rats. European Journal of Pharmacology, 115, 131–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyon WM, Ostroumov A, Ontiveros T, Gonzales RA & Dani JA (2021) Ethanol produces multiple electrophysiological effects on ventral tegmental area neurons in freely moving rats. Addiction Biology, 26, e12899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn AJ (1992) Endotoxin-induced activation of cerebral catecholamine and serotonin metabolism: comparison with interleukin-1. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics, 261, 964–969. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhofer G, Lambie DG & Johnson RH (1983) Effects of ethanol on plasma catecholamines and norepinephrine clearance. Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics, 34, 143–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ersche KD, Roiser JP, Lucas M, Domenici E, Robbins TW & Bullmore ET (2011) Peripheral biomarkers of cognitive response to dopamine receptor agonist treatment. Psychopharmacology (Berl), 214, 779–789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Essen C, Zervas NT, Brown DR, Koltun WA & Pickren KS (1980) Local cerebral blood flow in the dog during intravenous infusion of dopamine. Surgical Neurology, 13, 181–188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feduccia AA, Simms JA, Mill D, Yi HY & Bartlett SE (2014) Varenicline decreases ethanol intake and increases dopamine release via neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in the nucleus accumbens. British Journal of Pharmacology, 171, 3420–3431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes AB, Alves da Silva J, Almeida J, Cui G, Gerfen CR, Costa RM et al. (2020) Postingestive modulation of food seeking depends on vagus-mediated dopamine neuron activity. Neuron, 106, 778–788.e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gessa GL, Muntoni F, Collu M, Vargiu L. & Mereu G. (1985) Low doses of ethanol activate dopaminergic neurons in the ventral tegmental area. Brain Research, 348, 201–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall H, Sallemark M. & Jerning E. (1986) Effects of remoxipride and some related new substituted salicylamides on rat brain receptors. Acta Pharmacologica Et Toxicologica, 58, 61–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han W, Tellez LA, Perkins MH, Perez IO, Qu T, Ferreira J. et al. (2018) A neural circuit for gut-induced reward. Cell, 175, 665–678 e623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilani T, Ben-Shachar D, Strous RD, Mazor M, Sheinkman A, Kotler M. et al. (2001) A peripheral marker for schizophrenia: increased levels of D3 dopamine receptor mRNA in blood lymphocytes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 98, 625–628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imafuku J. (1987) The characterization of [3H]sulpiride binding sites in rat striatal membranes. Brain Research, 402, 331–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imperato A. & Di Chiara G. (1986) Preferential stimulation of dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens of freely moving rats by ethanol. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics, 239, 219–228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang EY, Choe ES, Hwang M, Kim SC, Lee JR, Kim SG et al. (2008) Isoliquiritigenin suppresses cocaine-induced extracellular dopamine release in rat brain through GABA(B) receptor. European Journal of Pharmacology, 587, 124–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang EY, Yang CH, Hedges DM, Kim SP, Lee JY, Ekins TG et al. (2017) The role of reactive oxygen species in methamphetamine self-administration and dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens. Addiction Biology, 22, 1304–1315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karkhanis AN, Huggins KN, Rose JH & Jones SR (2016) Switch from excitatory to inhibitory actions of ethanol on dopamine levels after chronic exposure: role of kappa opioid receptors. Neuropharmacology, 110, 190–197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawano M, Takagi R, Saika K, Matsui M. & Matsushita S. (2018) Dopamine regulates cytokine secretion during innate and adaptive immune responses. International Immunology, 30, 591–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RM, Votaw JR, de Paulis T, Bingham DR, Ansari MS, Mason NS et al. (1993) Evaluation of 5-[18F]fluoropropylepide-pride as a potential PET radioligand for imaging dopamine D2 receptors. Synapse (New York, N. Y.), 15, 169–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs GL, Soroncz M. & Tegyei I. (2002) Plasma catecholamines in ethanol tolerance and withdrawal in mice. European Journal of Pharmacology, 448, 151–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koyama S, Brodie MS & Appel SB (2007) Ethanol inhibition of m-current and ethanol-induced direct excitation of ventral tegmental area dopamine neurons. Journal of Neurophysiology, 97, 1977–1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kustrimovic N, Rasini E, Legnaro M, Bombelli R, Aleksic I, Blandini F. et al. (2016) Dopaminergic receptors on CD4+ T naive and memory lymphocytes correlate with motor impairment in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Scientific Reports, 6, 33738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laduron PM & Leysen JE (1979) Domperidone, a specific in vitro dopamine antagonist, devoid of in vivo central dopaminergic activity. Biochemical Pharmacology, 28, 2161–2165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawler CP, Prioleau C, Lewis MM, Mak C, Jiang D, Schetz JA et al. (1999) Interactions of the novel antipsychotic aripiprazole (OPC-14597) with dopamine and serotonin receptor subtypes. Neuropsychopharmacology, 20, 612–627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin C, McGonigle P. & Molinoff PB (1987) Characterization of D-2 dopamine receptors in a tumor of the rat anterior pituitary gland. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics, 242, 950–956. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lokhandwala MF & Barrett RJ (1982) Cardiovascular dopamine receptors: physiological, pharmacological and therapeutic implications. Journal of Autonomic Pharmacology, 2, 189–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenna F, McLaughlin PJ, Lewis BJ, Sibbring GC, Cummerson JA, Bowen-Jones D. et al. (2002) Dopamine receptor expression on human T-and B-lymphocytes, monocytes, neutrophils, eosinophils and NK cells: a flow cytometric study. Journal of Neuroimmunology, 132, 34–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michiels M, Hendriks R. & Heykants J. (1981) On the pharmacokinetics of domperidone in animals and man II. Tissue distribution, placental and milk transfer of domperidone in the Wistar rat. European Journal of Drug Metabolism and Pharmacokinetics, 6, 37–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Missale C, Nash SR, Robinson SW, Jaber M. & Caron MG (1998) Dopamine receptors: from structure to function. Physiological Reviews, 78, 189–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell UH, Obray JD, Hunsaker E, Garcia BT, Clarke TJ, Hope S. et al. (2018) Peripheral dopamine in restless legs syndrome. Frontiers in Neurology, 9, 155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mrejeru A, Marti-Prats L, Avegno EM, Harrison NL & Sulzer D. (2015) A subset of ventral tegmental area dopamine neurons responds to acute ethanol. Neuroscience, 290, 649–658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagahata Y, Azumi Y, Kawakita N, Wada T. & Saitoh Y. (1995) Inhibitory effect of dopamine on gastric motility in rats. Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology, 30, 880–885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagai Y, Ueno S, Saeki Y, Soga F, Hirano M. & Yanagihara T. (1996) Decrease of the D3 dopamine receptor mRNA expression in lymphocytes from patients with Parkinson’s disease. Neurology, 46, 791–795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishiyama T. (2005) Hemodynamic and catecholamine response to a rapid increase in isoflurane or sevoflurane concentration during a maintenance phase of anesthesia in humans. Journal of Anesthesia, 19, 213–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira-Maia AJ, Roberts CD, Walker QD, Luo B, Kuhn C, Simon SA et al. (2011) Intravascular food reward. PLoS One, 6, e24992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborne PG, O’Connor WT, Drew KL & Ungerstedt U. (1990) An in vivo microdialysis characterization of extracellular dopamine and GABA in dorsolateral striatum of awake freely moving and halothane anaesthetised rats. Journal of Neuroscience Methods, 34, 99–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park SY, Choi JY, Kim RU, Lee YS, Cho HJ & Kim DS (2003) Downregulation of voltage-gated potassium channel alpha gene expression by axotomy and neurotrophins in rat dorsal root ganglia. Molecules and Cells, 16, 256–259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pastor R, Miquel M. & Aragon CM (2005) Habituation to test procedure modulates the involvement of dopamine D2-but not D1-receptors in ethanol-induced locomotor stimulation in mice. Psychopharmacology (Berl), 182, 436–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelkonen A, Hiltunen M, Kiianmaa K. & Yavich L. (2010) Stimulated dopamine overflow and alpha-synuclein expression in the nucleus accumbens core distinguish rats bred for differential ethanol preference. Journal of Neurochemistry, 114, 1168–1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrulli JR, Kalish B, Nabulsi NB, Huang Y, Hannestad J. & Morris ED (2017) Systemic inflammation enhances stimulant-induced striatal dopamine elevation. Translational Psychiatry, 7, e1076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehm J. & Shield KD (2019) Global burden of disease and the impact of mental and addictive disorders. Current Psychiatry Reports, 21, 10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson DL, Howard EC, McConnell S, Gonzales RA & Wightman RM (2009) Disparity between tonic and phasic ethanol-induced dopamine increases in the nucleus accumbens of rats. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research, 33, 1187–1196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Roa PM, Grigoriadis DE, Wilson AA, Sharkey J, Dannals RF, Villemagne VL et al. (1989) [125]I-Spectramide: a novel benzamide displaying potent and selective effects at the D2 dopamine receptor. Life Sciences, 45, 1821–1829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santiago M. & Westerink BH (1990) Characterization of the in vivo release of dopamine as recorded by different types of intracerebral microdialysis probes. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Archives of Pharmacology, 342, 407–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schilaty ND, Hedges DM, Jang EY, Folsom RJ, Yorgason JT, McIntosh JM et al. (2014) Acute ethanol inhibits dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens via alpha6 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics, 349, 559–567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokoloff P, Giros B, Martres MP, Bouthenet ML & Schwartz JC (1990) Molecular cloning and characterization of a novel dopamine receptor (D3) as a target for neuroleptics. Nature, 347, 146–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Souza Silva MA, Topic B, Huston JP & Mattern C. (2008) Intranasal dopamine application increases dopaminergic activity in the neostriatum and nucleus accumbens and enhances motor activity in the open field. Synapse (New York, N. Y.), 62, 176–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spaak J, Merlocco AC, Soleas GJ, Tomlinson G, Morris BL, Picton P. et al. (2008) Dose-related effects of red wine and alcohol on hemodynamics, sympathetic nerve activity, and arterial diameter. American Journal of Physiology. Heart and Circulatory Physiology, 294, H605–612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steffensen SC, Bradley KD, Hansen DM, Wilcox JD, Wilcox RS, Allison DW et al. (2011) The role of connexin-36 gap junctions in alcohol intoxication and consumption. Synapse (New York, N. Y.), 65, 695–707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steffensen SC, Shin SI, Nelson AC, Pistorius SS, Williams SB, Woodward TJ et al. (2018) alpha6 subunit-containing nicotinic receptors mediate low-dose ethanol effects on ventral tegmental area neurons and ethanol reward. Addiction Biology, 23, 1079–1093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steffensen SC, Walton CH, Hansen DM, Yorgason JT, Gallegos RA & Criado JR (2009) Contingent and non-contingent effects of low-dose ethanol on GABA neuron activity in the ventral tegmental area. Pharmacology, Biochemistry and Behavior, 92, 68–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan JM, Risacher SL, Normandin MD, Yoder KK, Froehlich JC & Morris ED (2011) Imaging of alcohol-induced dopamine release in rats:preliminary findings with [(11) C]raclopride PET. Synapse (New York, N. Y.), 65, 929–937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang L, Todd RD, Heller A. & O’Malley KL (1994) Pharmacological and functional characterization of D2, D3 and D4 dopamine receptors in fibroblast and dopaminergic cell lines. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics, 268, 495–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Nueten JM & Schuurkes JA (1984) Studies on the role of dopamine and dopamine blockers in gastroduodenal motility. Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology. Supplement, 96, 89–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vigo D, Jones L, Thornicroft G. & Atun R. (2020) Burden of mental, neurological, substance use disorders and self-harm in North America: a comparative epidemiology of Canada, Mexico, and the United States. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 65, 87–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westerink BH & De Vries JB (1988) Characterization of in vivo dopamine release as determined by brain microdialysis after acute and subchronic implantations: methodological aspects. Journal of Neurochemistry, 51, 683–687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams SB, Yorgason JT, Nelson AC, Lewis N, Nufer TM, Edwards JG et al. (2018) Glutamate transmission to ventral tegmental area GABA neurons is altered by acute and chronic ethanol. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research, 42, 2186–2195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao C, Zhang J, Krnjevic K. & Ye JH (2007) Effects of ethanol on midbrain neurons: role of opioid receptors. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research, 31, 1106–1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang CH, Lee BB, Jung HS, Shim I, Roh PU & Golden GT (2002) Effect of electroacupuncture on response to immobilization stress. Pharmacology, Biochemistry and Behavior, 72, 847–855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yim HJ & Gonzales RA (2000) Ethanol-induced increases in dopamine extracellular concentration in rat nucleus accumbens are accounted for by increased release and not uptake inhibition. Alcohol, 22, 107–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yim HJ, Robinson DL, White ML, Jaworski JN, Randall PK, Lancaster FE et al. (2000) Dissociation between the time course of ethanol and extracellular dopamine concentrations in the nucleus accumbens after a single intraperitoneal injection. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 24, 781–788. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yli-Hankala A, Randell T, Seppala T. & Lindgren L. (1993) Increases in hemodynamic variables and catecholamine levels after rapid increase in isoflurane concentration. Anesthesiology, 78, 266–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yorgason JT, Espana RA & Jones SR (2011) Demon voltammetry and analysis software: analysis of cocaine-induced alterations in dopamine signaling using multiple kinetic measures. Journal of Neuroscience Methods, 202, 158–164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yorgason JT, Ferris MJ, Steffensen SC & Jones SR (2014) Frequency-dependent effects of ethanol on dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research, 38, 438–447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yorgason JT, Rose JH, McIntosh JM, Ferris MJ & Jones SR (2015) Greater ethanol inhibition of presynaptic dopamine release in C57BL/6J than DBA/2J mice: role of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Neuroscience, 284, 854–864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yorgason JT, Wadsworth HA, Anderson EJ, Williams BM, Brundage JN, Hedges DM et al. (2021) Modulation of dopamine release by ethanol is mediated by atypical GABAA receptors on cholinergic interneurons in the nucleus accumbens. Addiction Biology, 27(1), e13108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- You C, Savarese A, Vandegrift BJ, He D, Pandey SC, Lasek AW et al. (2019) Ethanol acts on KCNK13 potassium channels in the ventral tegmental area to increase firing rate and modulate binge-like drinking. Neuropharmacology, 144, 29–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahniser NR & Dubocovich ML (1983) Comparison of dopamine receptor sites labeled by [3H]-S-sulpiride and [3H]-spiperone in striatum. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics, 227, 592–599. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zapata A, Chefer VI & Shippenberg TS (2009) Microdialysis in rodents. Current Protocols in Neuroscience, 7(1), 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]