Abstract

We evaluated the susceptibilities of 129 Shiga-like toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC) isolates to various antibiotics. The numbers of isolates for which MICs were high (≧128 μg/ml) were as follows: 5 for fosfomycin, 14 for ampicillin, 1 for cefaclor, 6 for kanamycin, 22 for tetracycline, and 2 for doxycycline. For two isolates of STEC O26 MICs of fosfomycin were high (1,024 and 512 μg/ml, respectively). Conjugation experiments and glutathione S-transferase assays suggested that the fosfomycin resistance in these isolates was determined not by a plasmid but chromosomally. The amount of active intracellular fosfomycin in these STEC isolates was 100- to 200-fold less than that in E. coli C600 harboring pREFTT47B408 in the presence of either l-α-glycerophosphate or glucose-6-phosphate. Cloning, sequencing, and Northern blot analysis demonstrated that the transcriptional level of the murA gene encoding UDP-N-acetylglucosamine enolpyruvoyl transferase in these isolates was greater than that in E. coli C600. Our results suggest that the fosfomycin resistance in these STEC isolates is due to concurrent effects of alteration of the glpT and/or uhp transport systems and of the enhanced transcription of the murA gene.

Fosfomycin, a broad-spectrum antibiotic, enters cells by active transport through the l-α-glycerophosphate (α-GP) uptake system (GlpT) and the glucose-6-phosphate (G6P) uptake system (Uhp) and inhibits peptidoglycan biosynthesis through the inactivation of the enzyme UDP-N-acetylglucosamine (UDP-GlcNAc) enolpyruvoyl transferase (8). Fosfomycin has been the drug of choice for pediatric gastrointestinal infections due to Shiga-like toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC) in Japan, and the early administration (within 3 days of onset) of fosfomycin is critical for the effective treatment of STEC infections (20).

It has been reported that chromosomally encoded fosfomycin-resistant strains had an impairment in fosfomycin uptake (7), a low-affinity UDP-GlcNAc enolpyruvoyl transferase (22), or overproduction of the enzyme (11) in studies using E. coli E-15, B, Prl, K-12, or American Type Culture Collection strains. Studies have demonstrated that the fosfomycin resistance encoded by plasmids is due to an enzymatic modification of fosfomycin in some clinical isolates of Serratia marcescens, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Enterobacter cloacae, and Staphylococcus epidermidis (1, 3, 13, 15, 19). At present, however, little is known concerning the prevalence and mechanism of fosfomycin resistance, especially in clinical isolates. To characterize fosfomycin resistance epidemiologically and biologically in clinical isolates of STEC, we evaluated the susceptibilities of 129 STEC isolates to several oral antibiotics and determined the mechanism of fosfomycin resistance in the resistant isolates.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

The strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. Two E. coli O26 strains resistant to fosfomycin (NGY47 and NGY60) were selected from 129 strains of STEC isolated in 1996 and 1997 from different patients in Japan (Table 2). NGY47 and NGY60 were isolated from different patients who had visited different Nagoya city hospitals from June to August 1997. The O and H antigen types of strains were determined with neutralizing antisera (Denka-Seiken, Tokyo, Japan). These STEC isolates included serotypes of O157 (80 strains), O26 (31 strains), O111 (11 strains), O103 (2 strains), O118 (2 strains), O1 (1 strain), O6 (1 strain), and O165 (1 strain). The H antigen types of NGY47 and NGY60 were nonmobile and H11, respectively. Bacteria were stored at −70°C in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.) containing 20% glycerol. Subsequently, bacteria were inoculated on LB agar plates and incubated at 37°C overnight.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant properties | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli | ||

| C600 | F−lacY1 leuB6 supE44 thi-1 thr-1 tonA21 | Laboratory strain |

| CSH-2 | metB F− Nalr Rifr | T. Sawai, Chiba University |

| JM83 | F−ara Δ(lac-proAB) rpsL(φ80 lacZΔM15) | Laboratory strain |

| XL1-Blue | endA1 gyrA96 hsdR17 lac recA1 relA1 supE44 thi-1 Tetr | Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif. |

| O26 NGY47 | Clinical isolate, Fosr Tetr | This study |

| O26 NGY60 | Clinical isolate, Fosr | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pHSG398 | High-copy-number vector, Cmr | 24 |

| pWKS130 | Low-copy-number vector, Kanr | 23 |

| pBluescript SK II+ | Vector for sequencing, Ampr | Stratagene |

| pUC19 | Cloning vector, Ampr | 24 |

| pMZY102 | Subclone carrying the fosB gene derived from fosfomycin-resistant S. aureus MF51 (vector, pUC19) | Unpublished data |

| pREFTT4701 | Subclone carrying the murA gene of E. coli O26 NGY47 (vector, pHSG398) | This study |

| pREFTT6023 | Subclone carrying the murA gene of E. coli O26 NGY60 (vector, pHSG398) | This study |

| pREFTT47B408 | Subclone carrying the murA gene of E. coli O26 NGY47 (vector, pWKS130) | This study |

| pREFTT60K804 | Subclone carrying the murA gene of E. coli O26 NGY60 (vector, pWKS130) | This study |

TABLE 2.

Antibiotic susceptibilities of 129 STEC isolates

| Antibiotic | MIC (μg/ml)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Range | % Inhibition

|

||

| 50 | 90 | ||

| Fosfomycina | 0.5–≧512 | 8 | 32 |

| Ampicillin | 4–≧512 | 4 | 128 |

| Cefaclor | 1–128 | 4 | 16 |

| Gentamicin | 0.125–2 | 1 | 2 |

| Kanamycin | 1–≧512 | 4 | 8 |

| Tetracycline | 0.5–256 | 2 | 2 |

| Doxycycline | 0.5–128 | 2 | 64 |

| Minocycline | 0.5–32 | 2 | 4 |

| Norfloxacin | ≦0.064–1 | 0.125 | 0.125 |

| Azithromycin | 2–8 | 4 | 8 |

| Chloramphenicol | 1–64 | 4 | 8 |

Determined on Mueller-Hinton agar containing 50 μg of G6P per ml.

Antibiotics.

The antibiotics used were ampicillin, fosfomycin, and kanamycin (Meiji Seika Kaisha, Tokyo, Japan), azithromycin (Pfizer Pharmaceuticals, Tokyo, Japan), cefaclor (Shionogi Pharmaceutical, Osaka, Japan), chloramphenicol and doxycycline (Sankyo, Tokyo, Japan), gentamicin (Schering-Plough, Osaka, Japan), norfloxacin (Kyorin Pharmaceutical, Tokyo, Japan), and tetracycline and minocycline (Japan Lederle, Tokyo, Japan).

Susceptibility testing.

MICs were determined by an agar dilution method as described by the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards (14). Susceptibility testing was performed on Mueller-Hinton agar (Difco) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. MICs of fosfomycin were determined for all strains on Mueller-Hinton agar containing 50 μg of G6P (Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Osaka, Japan) per ml.

Glutathione S-transferase assay.

For preparation of cell extracts, the cells were ruptured by ultrasonication at 4°C. Cell debris was removed by centrifugation. Aliquots of 0.1 ml of fosfomycin (125 μg/ml), 0.1 ml of 40 mM glutathione, and 0.8 ml of crude extract (5 mg/ml) were mixed and allowed to react at 37°C for 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, and 24 h. The reaction was stopped by heating at 100°C for 90 s. After centrifugation, the residual potency of fosfomycin was determined by microbiological assay, as previously described (15). Control experiments were performed using E. coli JM83 harboring pUC19 or pMZY102 (Table 1).

Determination of active intracellular fosfomycin levels.

Bacteria were grown in 20 ml of LB broth to an optical density at 590 nm of 0.2. Either α-GP or G6P was added to a concentration of 2.5 mM, and the culture was incubated at 37°C for 90 min. α-GP and G6P were used to exclude the presence of spontaneous subpopulations, which are impaired in fosfomycin uptake. The bacteria were then washed twice with fresh LB broth and finally resuspended in 1 ml of LB broth. This suspension was incubated for 3, 10, 20, 40, 60, and 90 min at 37°C in the presence of 2 mg of fosfomycin per ml. The bacteria were then collected by centrifugation and washed with hypertonic buffer (10 mM Tris, 0.5 mM MgCl2, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.3) to remove the antibiotic. Cells were resuspended in 5 ml of phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.4) and disrupted by passage through a French press (SLM Instruments, Urbana, Ill.). The debris was discarded after centrifugation (100,000 × g for 15 min), and the antibiotic concentration in the supernatant was determined by microbiological assay, with E. coli XL1-Blue as the indicator strain (15). Control assays were carried out with an extract of each strain obtained by processing the cells immediately after fosfomycin addition (time zero). To quantify bacteria, aliquots (after the antibiotic had been removed) were serially diluted in phosphate-buffered saline, and 0.1 ml from each dilution was plated on LB agar. After overnight incubation at 37°C, the numbers of CFU/ml were counted.

DNA techniques.

The chromosomal DNA of E. coli NGY47 and NGY60 and plasmid DNA were extracted as described previously (16). Restriction endonucleases and T4 DNA ligase were supplied by Takara Biomedicals (Ohtsu, Japan) and were used as recommended by the manufacturer.

To obtain clones containing the murA gene (encoding UDP-GlcNAc enolpyruvoyl transferase) derived from STEC NGY47 and NGY60, partially Sau3AI-digested fragments of chromosomal DNA from these isolates were ligated into the BamHI site of a high-copy-number vector, pHSG398. These recombinants were introduced into E. coli C600, and transformants resistant to both fosfomycin and chloramphenicol were isolated. A 3.9-kb derivative containing a 1.7-kb insert was termed pREFTT4701. The 1.7-kb fragment was transferred into the BamHI site of a low-copy-number vector, pWKS130. This recombinant was introduced into E. coli C600 and was termed pREFTT47B408. Similarly, the construction of plasmids from chromosomal DNA of STEC NGY60 was performed. A 1.5-kb fragment digested partially by Sau3AI was ligated into the BamHI sites of pHSG398 and pWKS130, and fosfomycin-resistant clones were isolated. These plasmids were termed pREFTT6023 and pREFTT60K804, respectively.

Nucleotide sequencing and analysis.

To determine the nucleotide sequences of the inserts in pREFTT4701 and pREFTT6023, the DNA fragments were transferred into pBluescript SK II+ and the recombinant was introduced into E. coli XL1-Blue. Deletion subclones for sequencing were constructed, by using exonuclease III, mung bean nuclease, and Klenow fragment in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions (deletion kit; Nippon Gene, Toyama, Japan), and the DNA fragments were sequenced, with the ABI PRISM dye primer cycle sequencing ready reaction kit with AmpliTaq DNA polymerase and −21M13 dye primers (Perkin-Elmer, Foster City, Calif.) and an automated DNA sequencing system (model 373A; Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.), as previously described (6).

Northern blot analysis.

As a hybridization probe, the 1.7-kb BamHI fragment of pREFTT4701 was excised from a low-melting-temperature agarose gel (Nippon Gene) after electrophoresis and was labeled with digoxigenin-11-dUTP (random primer labeling kit; Boehringer, Mannheim, Germany). Total RNA of bacteria separated on agarose gels (Nippon Gene) was transferred to a Hybond N+ nylon membrane (Amersham, Little Chalfont, Buckinghamshire, United Kingdom) (18). Total RNA was isolated as described by Kornblum et al. (10). Hybridization and immunological detection were performed with 1,2-dioxetane chemiluminescent enzyme substrate (CSPD) (Tropix, Bedford, Mass.) as the chemiluminescent substrate for alkaline phosphatase. Levels of murA expression were measured by the National Institutes of Health Image program, version 1.61, which is a public domain image processing and analysis program for the Macintosh (15a).

RESULTS

Antibiotic susceptibility.

The results of susceptibility testing are summarized in Table 2. These STEC isolates were generally susceptible to gentamicin, minocycline, norfloxacin, and azithromycin. The numbers of isolates for which MICs were high (≧128 μg/ml) were as follows: 5 for fosfomycin, 14 for ampicillin, 1 for cefaclor, 6 for kanamycin, 22 for tetracycline, and 2 for doxycycline. STEC O26 NGY47 and NGY60 were especially highly resistant to fosfomycin (1,024 and 512 μg/ml, respectively).

To investigate the mechanism of fosfomycin resistance in NGY47 and NGY60, further experiments were performed. Since previous studies had shown that high-level resistance to fosfomycin was due to a plasmid-mediated fosfomycin-glutathione S-transferase (1, 3, 13, 15, 19), we measured the activity of this enzyme in these STEC isolates. After treatment with the crude extracts of both NGY47 and NGY60 in the presence of glutathione, the residual potency of fosfomycin was not reduced, whereas intracellular fosfomycin was reduced in E. coli JM83 harboring pMZY102 encoding the fosB gene (data not shown). Moreover, the transfer of fosfomycin resistance from these isolates to E. coli CSH-2 by conjugation was unsuccessful. These results suggested no involvement of fosfomycin-glutathione S-transferase in the fosfomycin resistance of NGY47 and NGY60.

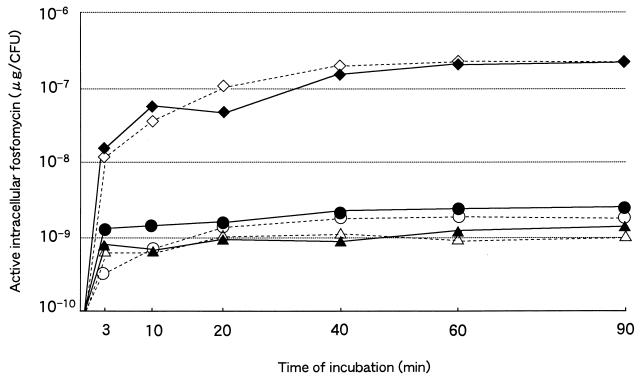

Accumulation of active intracellular fosfomycin.

Other possible mechanisms of fosfomycin resistance include impairment of fosfomycin uptake (7), a low-affinity UDP-GlcNAc enolpyruvoyl transferase (22), or overproduction of this enzyme encoded by the murA gene (11). A time course study of fosfomycin uptake into cells was undertaken for NGY47, NGY60, and E. coli C600 harboring pREFTT47B408 in the presence of either α-GP or G6P (Fig. 1). NGY47 and NGY60 accumulated 100- to 200-fold less fosfomycin than C600 harboring pREFTT47B408, which rapidly incorporated fosfomycin at the examined concentration. Because the MIC of fosfomycin for C600 harboring pREFTT47B408 was only 32 μg/ml, the poor uptake in NGY47 and NGY60 is thought to contribute to the high fosfomycin resistance. It should be noted that the time course response of fosfomycin accumulation in the presence of α-GP was similar to that in the presence of G6P.

FIG. 1.

The amount of active intracellular fosfomycin over the time course (micrograms per CFU). The fosfomycin uptake into cells was compared in NGY47, NGY60, and C600 harboring pREFTT47B408 in the presence of either α-GP or G6P. ▵, NGY47 (α-GP); ▴, NGY47 (G6P); ○, NGY60 (α-GP); ●, NGY60 (G6P); ◊, C600 harboring pREFTT47B408 (α-GP); ⧫, C600 harboring pREFTT47B408 (G6P).

Analysis of the murA gene.

The murA genes of NGY47 and NGY60 were cloned, and the plasmids containing them were termed pREFTT4701 and pREFTT6023, respectively. A 1.7-kb insert of pREFTT4701 and a 1.5-kb insert of pREFTT6023 were mapped with various restriction enzymes. Their low-copy-number vector derivatives were termed pREFTT47B408 and pREFTT60K804, respectively.

The nucleotide sequences of the 1,692-bp BamHI fragment of pREFTT4701 and 1,455-bp BamHI-SmaI fragment of pREFTT6023 were determined. Both sequenced regions contained a 1,260-bp open reading frame with a putative promoter region that encodes a 419-amino-acid protein. These open reading frames showed good homology with the murA (murZ) gene encoding UDP-GlcNAc enolpyruvoyl transferase (98.9 and 98.7% at the nucleotide level, respectively) of E. coli AB1157 (11). The homology at the amino acid level of MurA of NGY47 and NGY60 with that of AB1157 MurA (MurZ) was 100 and 99.8%, respectively. Lys11 of AB1157 MurA (MurZ) was substituted for Glu11 in NGY60.

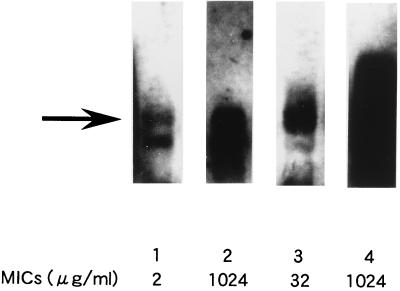

Expression of the murA gene.

To determine the involvement of the murA gene in resistance to fosfomycin, we performed Northern blotting on total RNA extracted from NGY47, C600 harboring pREFTT4701 or pREFTT47B408, and C600. As Fig. 2 shows, the transcriptional level of the murA gene was enhanced in NGY47, compared with C600. The murA mRNA level in C600 harboring pREFTT4701 was much higher than that in C600 harboring pREFTT47B408. The murA mRNA level of NGY47 appeared to be similar to that of C600 harboring pREFTT47B408. The quantitative estimates of the mRNA level by the National Institutes of Health Image program were 79.6, 174.0, 70.1, and 32.9 for NGY47, C600 harboring pREFTT4701, C600 harboring pREFTT47B408, and C600, respectively. To characterize the relationship between the increase in the murA mRNA level and MIC of fosfomycin, MICs for these strains were determined. MICs for NGY47, C600 harboring pREFTT4701, C600 harboring pREFTT47B408, and C600 were 1,024, 1,024, 32, and 2 μg/ml, respectively (Fig. 2). These results suggest that the increase in the murA mRNA expression is correlated with the MIC of fosfomycin. Therefore, the enhanced transcriptional level of the murA gene in NGY47 confers, at least partly, resistance to fosfomycin.

FIG. 2.

Northern blot analysis of the murA transcript in NGY47, C600 harboring pREFTT4701 or pREFTT47B408, and C600. Lane 1, C600; lane 2, NGY47; lane 3, C600 harboring pREFTT47B408 (vector, pWKS130); lane 4, C600 harboring pREFTT4701 (vector, pHSG398). An arrow indicates the position of the murA transcript. The MIC of fosfomycin for each strain is shown under its lane number.

Comparable results were obtained when Northern blotting was performed on total RNA from NGY60 and C600 harboring pREFTT6023 or pREFTT60K804 (data not shown). MICs for C600 harboring pREFTT6023 and pREFTT60K804 were 1,024 and 32 μg/ml, respectively.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we characterized fosfomycin resistance in two clinical isolates of STEC O26. The emergence of fosfomycin-resistant STEC isolates has become a significant problem in antibiotic therapy for STEC infections (20). To date, fosfomycin resistance has been studied in some strains (1, 5, 7, 8, 11, 12). Although no STEC strains showing high resistance to fosfomycin have been reported (21), we found that two STEC isolates whose H types were different, NGY47 and NGY60, exhibited high resistance to fosfomycin, among 129 clinical isolates. Therefore, it is of great value to characterize the fosfomycin resistance of STEC isolates for antibiotic therapy.

Previous reports have shown that fosfomycin resistance in E. coli was conferred by chromosomal genes such as glpT, uhp, murA (murZ), and fsr (5, 8, 11, 12), whereas an inactivating enzyme, fosfomycin-glutathione S-transferase, mediated by a plasmid (1, 3, 13, 15, 19) has not been reported in E. coli. Our results also indicated that the presence of the inactivating enzyme in NGY47 and NGY60 was unlikely because of the failures of both the detection of glutathione S-transferase activity and the conjugational transfer of the fosfomycin resistance. Moreover, our results suggested that these fosfomycin-resistant STEC isolates had presumably altered glpT and/or uhp transport systems.

It has been reported that the mutation of the covalently attaching site of fosfomycin, Cys115, in MurA (MurZ) or overexpression of the murA (murZ) gene conferred fosfomycin resistance (2, 11, 12, 17). MurA of NGY47 and NGY60 exhibited 100% identity with E. coli MurA (MurZ), and Cys115 was conserved, suggesting that the fosfomycin resistance in these strains was not caused by a mutation of MurA. Northern blot analysis suggested that enhanced transcription of the murA gene in these strains was also involved in fosfomycin resistance.

Our results were consistent with previous observations. In clinical isolates, some studies have demonstrated that the mechanism of chromosomally encoded fosfomycin resistance mainly involved reduced permeability of the cell membrane (1, 15). Arca et al. (1) evaluated genetically and biologically a number of fosfomycin-resistant clinical isolates, including E. coli, Staphylococcus aureus, and Morganella morganii. They demonstrated that the fosfomycin resistance conferred by plasmids constituted little of the overall resistance to fosfomycin, which was caused by an alteration of the transport system. The results reported here, however, demonstrated that alterations of at least two chromosomal determinants conferred high resistance to fosfomycin in STEC. To the best of our knowledge, fosfomycin resistance owing to concurrent alterations has not previously been reported. Although the frequency of these mutations in STEC is not known, our results suggest that more fosfomycin-resistant isolates will emerge spontaneously without the acquisition of a plasmid in the future.

Additionally, we evaluated the susceptibilities of STEC isolates to various oral antibiotics. In previous studies, the emergence of STEC strains resistant to ampicillin, gentamicin, tetracycline, streptomycin, sulfisoxazole, and/or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole has been reported (4, 9, 21). Our results showed the presence of STEC isolates for which MICs of fosfomycin, ampicillin, cefaclor, kanamycin, tetracycline, and/or doxycycline were high, whereas all STEC isolates were susceptible to gentamicin, minocycline, norfloxacin, and azithromycin. The presence of STEC strains resistant to some oral antibiotics, therefore, should be taken into account in planning therapy for STEC infections.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Tsutomu Tsuruoka and Takashi Ida, Meiji Seika Kaisha, for the glutathione S-transferase assay. We also thank the members of the Equipment Center for Research and Education, Nagoya University School of Medicine, for their technical support with sequencing.

This work was supported by a grant for scientific research from Yakult, Tokyo, Japan.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arca P, Reguera G, Hardisson C. Plasmid-encoded fosfomycin resistance in bacteria isolated from the urinary tract in a multicentre survey. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1997;40:393–399. doi: 10.1093/jac/40.3.393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ehrt S, Hillen W. UDP-N-acetylglucosamine 1-carboxyvinyl-transferase from Acinetobacter calcoaceticus. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1994;117:137–142. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1994.tb06755.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Etienne J, Gerbaud G, Courvalin P, Fleurette J. Plasmid-mediated resistance to fosfomycin in Staphylococcus epidermidis. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1989;61:133–138. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(89)90184-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Farina C, Goglio A, Conedera G, Minelli F, Caprioli A. Antimicrobial susceptibility of Escherichia coli O157 and other enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli isolated in Italy. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1996;15:351–353. doi: 10.1007/BF01695674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fujisaki S, Ohnuma S, Horiuchi T, Takahashi I, Tsukui S, Nishimura Y, Nishio T, Kitabatake M, Inokuchi H. Cloning of a gene from Escherichia coli that confers resistance to fosmidomycin as a consequence of amplification. Gene. 1996;175:83–87. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(96)00128-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Horii T, Arakawa Y, Ohta M, Sugiyama T, Wacharotayankun R, Ito H, Kato N. Characterization of a plasmid-borne and constitutively expressed blaMOX-1 gene encoding AmpC-type β-lactamase. Gene. 1994;139:93–98. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90529-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kadner R J, Winkler H H. Isolation and characterization of mutations affecting the transport of hexose phosphates in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1973;113:895–900. doi: 10.1128/jb.113.2.895-900.1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kahan F M, Kahan J S, Cassidy P J, Kroop H. The mechanism of action of fosfomycin (phosphonomycin) Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1974;235:364–385. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1974.tb43277.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim H H, Samadpour M, Grimm L, Clausen C R, Besser T E, Baylor M, Kobayashi J M, Neill M A, Schoenknecht F D, Tarr P I. Characteristics of antibiotic-resistant Escherichia coli O157:H7 in Washington State, 1984–1991. J Infect Dis. 1994;170:1606–1609. doi: 10.1093/infdis/170.6.1606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kornblum J, Projan S J, Moghazeh S L, Novick R P. A rapid method to quantitate non-labeled RNA species in bacterial cells. Gene. 1988;63:75–85. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90547-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marquardt J L, Siegele D A, Kolter R, Walsh C T. Cloning and sequencing of Escherichia coli murZ and purification of its product, a UDP-N-acetylglucosamine enolpyruvyl transferase. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:5748–5752. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.17.5748-5752.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marquardt J L, Brown E D, Lane W S, Haley T M, Ichikawa Y, Wong C-H, Walsh C T. Kinetics, stoichiometry, and identification of the reactive thiolate in the inactivation of UDP-GlcNAc enolpyruvoyl transferase by the antibiotic fosfomycin. Biochemistry. 1994;33:10646–10651. doi: 10.1021/bi00201a011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mendoza C, Garcia J M, Llaneza J, Mendez F J, Hardisson C, Ortiz J M. Plasmid-determined resistance to fosfomycin in Serratia marcescens. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1980;18:215–219. doi: 10.1128/aac.18.2.215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically, 2nd ed. Approved Standard M7-A3. Villanova, Pa: National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 15.O’Hara K. Two different types of fosfomycin resistance in clinical isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1993;114:9–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1993.tb06543.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15a.Rasband, W. 13 December 1997, posting date. [Online.] Image program, version 1.61. National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Md. ftp://zippy.nimh.nih.gov.

- 16.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schonbrunn E, Sack S, Eschenburg S, Perrakis A, Krekel F, Amrhein N, Mandelkow E. Crystal structure of UDP-N-acetylglucosamine enolpyruvyltransferase, the target of the antibiotic fosfomycin. Structure. 1996;4:1065–1075. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(96)00113-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Southern E M. Detection of specific sequences among DNA fragments separated by gel electrophoresis. J Mol Biol. 1975;98:503–517. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(75)80083-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Suarez J E, Mendoza M C. Plasmid-encoded fosfomycin resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1991;35:791–795. doi: 10.1128/aac.35.5.791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Takeda T, Yoshino K, Uchida H, Ikeda N, Tanimura M. Escherichia coli O157:H7 and other Shiga toxin-producing E. coli strains. In: Kaper J B, O’Brien A D, editors. Escherichia coli O157:H7 and other Shiga toxin-producing E. coli strains. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1998. pp. 385–387. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tsuboi I, Ida H, Yoshikawa E, Hiyoshi S, Yamaji E, Nakayama I, Nonomiya T, Shigenobu F, Shimizu M, O’Hara K, Sawai T, Mizuoka K. Antibiotic susceptibility of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7 isolated from an outbreak in Japan in 1996. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:431–432. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.2.431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Venkateswaran P S, Wu H C. Isolation and characterization of a phosphonomycin-resistant mutant of Escherichia coli K-12. J Bacteriol. 1972;110:935–944. doi: 10.1128/jb.110.3.935-944.1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang R F, Kushner S R. Construction of versatile low-copy-number vectors for cloning, sequencing, and gene expression in Escherichia coli. Gene. 1991;100:195–199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yanisch-Perron C, Vieira J, Messing J. Improved M13 phage cloning vectors and host strains: nucleotide sequences of the M13mp18 and pUC19 vectors. Gene. 1985;33:103–119. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(85)90120-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]