Abstract

The cloning of agronomically important genes from large, complex crop genomes remains challenging. Here we generate a 14.7 gigabase chromosome-scale assembly of the South African bread wheat (Triticum aestivum) cultivar Kariega by combining high-fidelity long reads, optical mapping and chromosome conformation capture. The resulting assembly is an order of magnitude more contiguous than previous wheat assemblies. Kariega shows durable resistance to the devastating fungal stripe rust disease1. We identified the race-specific disease resistance gene Yr27, which encodes an intracellular immune receptor, to be a major contributor to this resistance. Yr27 is allelic to the leaf rust resistance gene Lr13; the Yr27 and Lr13 proteins show 97% sequence identity2,3. Our results demonstrate the feasibility of generating chromosome-scale wheat assemblies to clone genes, and exemplify that highly similar alleles of a single-copy gene can confer resistance to different pathogens, which might provide a basis for engineering Yr27 alleles with multiple recognition specificities in the future.

Subject terms: Plant genetics, Genomics

Chromosome-scale genome assembly of the South African bread wheat (Triticum aestivum) cultivar Kariega facilitates the cloning of the stripe rust resistance gene Yr27.

Main

Circular consensus sequencing (CCS)4 represents a recent technological breakthrough in DNA sequencing that circumvents the hitherto negative relationship between read length and accuracy, enabling the production of genome assemblies with greatly improved completeness and contiguity5,6. However, the large (approximately 16 gigabase (Gb)), repeat-rich genome of polyploid bread wheat remains a challenge for genome sequencing and gene cloning projects. A comparison of the genomes of various bread wheat cultivars demonstrated their high tolerance for extensive structural rearrangements, introgressions from wild wheat relatives and differences in gene content7,8, highlighting the need to generate genomic resources from specific donor wheat lines to guide the cloning of agronomically important genes. Stripe rust (or yellow rust), caused by the fungal pathogen Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici (Pst), is of increasing concern for global wheat production9. Of the 83 yellow rust resistance (Yr) genes described in the wheat gene pool, only nine have been cloned so far10, precluding knowledge-guided global deployment of Yr genes based on sequences and molecular mechanisms. Kariega, a South African spring bread wheat cultivar released in 1993, shows high levels of adult plant stripe rust resistance (Fig. 1a). Despite its extensive use in wheat production and as a parent in breeding programs, Kariega remains resistant to all Pst races prevalent in South Africa. The resistance of Kariega to stripe rust is conferred by three quantitative trait loci (QTLs): QYr.sgi-2B.1 on chromosome arm 2BS; QYr.sgi-4A.1 on chromosome arm 4AL; and the durable stripe rust resistance gene Yr18 on chromosome arm 7DS, which encodes an ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter1,11.

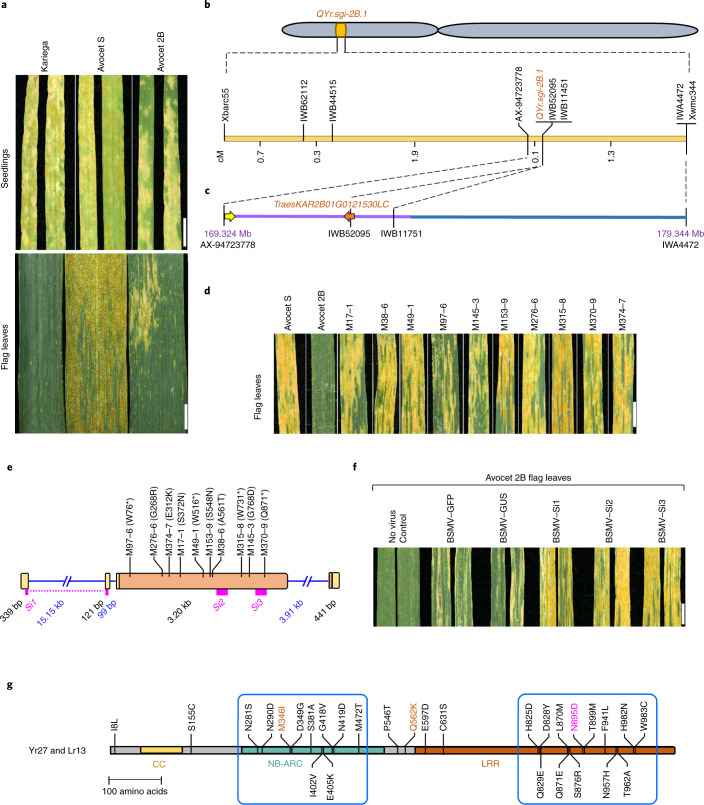

Fig. 1. Assembly-guided cloning of QYr.sgi-2B.1.

a, Stripe rust symptoms on Kariega, Avocet S and Avocet 2B in seedlings (upper panel) and adult plants (lower panel). Scale bars, 1 cm. b, Genetic map of the QYr.sgi-2B.1 region. Numbers between markers indicate genetic distances. c, Physical interval of the QYr.sgi-2B.1 region. Numbers indicate positions (in megabases) in the Kariega 2B pseudomolecule. The interval contained 93 candidate genes that were determined based on the annotated high-confidence gene models (92 high-confidence genes) and the NLR annotation. The NLR annotation identified one additional gene (TraesKAR2B01G0121530LC) that was annotated as a low-confidence gene. The two arrows indicate NLR-encoding genes that were prioritized for gene validation. Purple and blue bars indicate two primary HiFi contigs (47.7 Mb and 19.5 Mb, respectively) that spanned the target interval. d, Stripe rust inoculation on Avocet 2B and ten independent EMS mutants that lost the QYr.sgi-2B.1-mediated resistance. Scale bar, 1 cm. e, Gene structure of QYr.sgi-2B.1. Boxes, exons; lines, introns; yellow boxes, 5′ UTR and 3′ UTR; orange boxes, coding sequence. Positions of the corresponding amino acid changes in the ten loss-of-function mutants are indicated. Si1, Si2 and Si3 denote three VIGS constructs. f, Representative images showing the results of the VIGS experiment. The control ‘no virus’ contained no BSMV. BSMV–GFP and BSMV–GUS denote controls with a GFP or GUS silencing construct, respectively. BSMV–Si1, BSMV–Si2 and BSMV–Si3 denote three different silencing constructs that target QYr.sgi-2B.1. The specificity of Si1–Si3 was evaluated using the Kariega assembly. The image shows flag leaves 15 days after inoculation with an avirulent Pst isolate. Chlorotic areas on the GUS and GFP controls represent virus symptoms. Scale bar, 1 cm. g, Comparison of the Yr27 and Lr13 protein sequences. The first residue is the one present in Yr27, and the second residue is the one present in Lr13. Blue boxes indicate regions with increased polymorphism density. The two amino acids shown in brown have been found to determine the Lr13-specificity2. The residue shown in magenta is found only in Yr27.

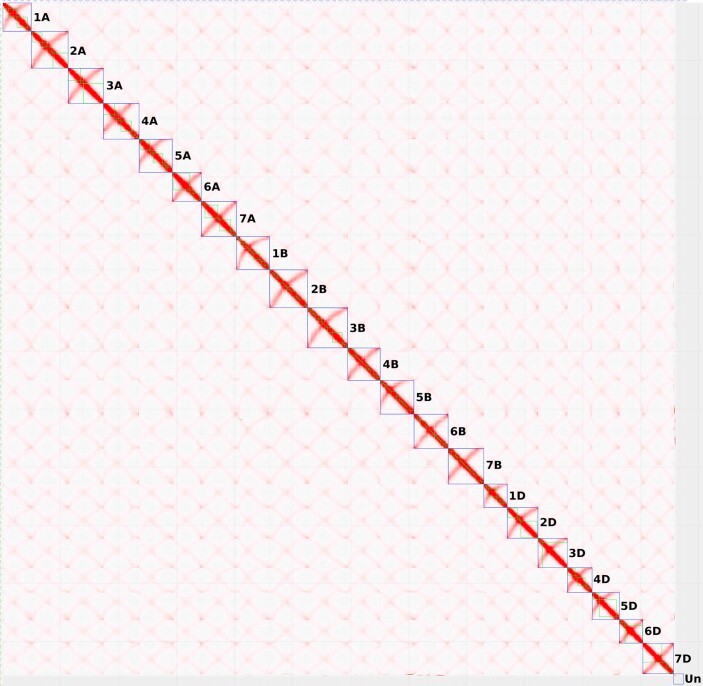

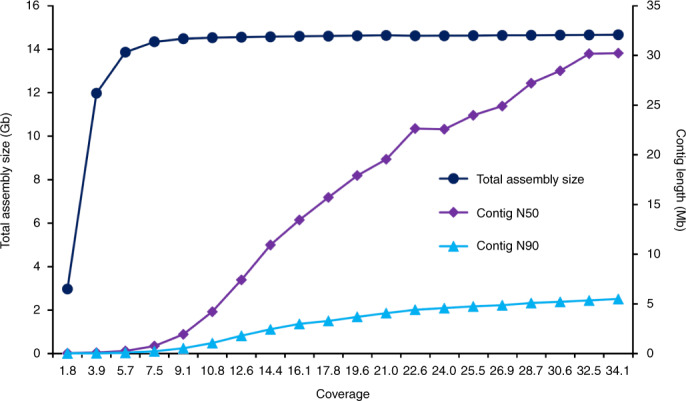

To facilitate the cloning of the remaining stripe rust resistance genes from Kariega, we generated a de novo genome assembly. First, we generated PacBio CCS (HiFi) reads corresponding to approximately 34-fold coverage (Supplementary Table 1) that we assembled using hifiasm12, resulting in an assembly length of 14.66 Gb with a contig N50 length of 30.22 megabases (Mb) (Table 1 and Supplementary Table 2). For comparison, contig N50s from previous whole-genome bread wheat assemblies based on short-read sequencing or PacBio continuous long-read (CLR) sequencing ranged from 49 to 233 kilobases (kb)7,13,14; thus, the Kariega assembly represents a ~130–600-fold improvement. The assembly took 43 h of computing time on 48 central processing unit (CPU) cores and ~550 gigabytes of random access memory (RAM). Next we generated hybrid scaffolds using a direct label and stain (DLS) optical map (Supplementary Table 3), resulting in the assembly of 324 hybrid scaffolds with a combined length of 14.5 Gb and an N50 of 204.3 Mb. The longest hybrid scaffold was 627.2 Mb and covered 99% of chromosome 3D (Supplementary Table 3). The final 14.68 Gb chromosome-scale assembly was produced by integrating chromosome conformation capture data (Omni-C; Extended Data Fig. 1). About 98.5% (14.45 Gb) of the assembly comprised 21 pseudomolecules, with the remaining 0.22 Gb combined into an unanchored pseudochromosome (Table 1). We validated the concordance of the assembly by mapping the optical map onto the Kariega pseudomolecules and found no major discrepancies. We recovered 99.4% of the 4,896 Poales single-copy core genes (BUSCO v.5.0.0)15 in the Kariega assembly, with 96.3% being duplicated (Extended Data Fig. 2). This underscores the high contiguity, completeness and accuracy of the assembly. Comparison of the Kariega assembly with previous chromosome-scale bread wheat assemblies revealed high collinearity (Extended Data Fig. 3). We annotated the Kariega assembly with support from transcriptome (Supplementary Table 4) and isoform (Supplementary Table 5) sequencing from six different tissues, and defined 116,838 high-confidence gene models.

Table 1.

Statistics of the Kariega genome assembly and annotation

| Genomic feature | Value |

|---|---|

| Length of HiFi assembly | 14.66 Gb |

| Number of contigs | 5,055 |

| Length of contig N50 | 30.22 Mb |

| Length of contig N90 | 5.5 Mb |

| Length of hybrid assemblya | 14.68 Gb |

| Length of hybrid scaffolds | 14.46 Gb |

| Number of hybrid scaffolds | 324 |

| Length of hybrid scaffold N50 | 204.26 Mb |

| Gap size | 18.8 Mb (0.13%) |

| Length of pseudomolecule assembly | 14.68 Gb |

| Total length of anchored pseudomolecules | 14.45 Gb |

| Number of anchored hybrid scaffolds or contigs | 717 |

| Gap size | 11.6 Mb (0.08%) |

| Number of high-confidence genes | 110,383 |

| Total length of unanchored chromosome | 224.01 Mb |

| Number of unanchored hybrid scaffolds or contigs | 3,910 |

| Gap size | 8.1 Mb (3.6%) |

| Number of high-confidence genes | 6,455 |

| BUSCO | |

| Complete | 99.4% |

| Duplicated | 96.3% |

| Fragmented | 0.1% |

| Missing | 0.5% |

aIncludes all hybrid scaffolds and remaining contigs that were not integrated into hybrid scaffolds.

Extended Data Fig. 1. Chromosome contact maps across the 21 pseudomolecules of the Kariega assembly.

Green squares indicate individual hybrid scaffolds and blue boxes pseudomolecules.

Extended Data Fig. 2. Number of universal single-copy orthologs that were missing or fragmented, present in a single copy, or present in multiple copies.

The result of the Kariega assembly is compared to the chromosome-scale assemblies of the 10+ Wheat Genomes Project.

Extended Data Fig. 3.

Comparison of the Kariega pseudomolecule assembly with the Chinese Spring IWGSC RefSeq v2.1 and the chromosome-scale assemblies of the 10+ Wheat Genomes Project.

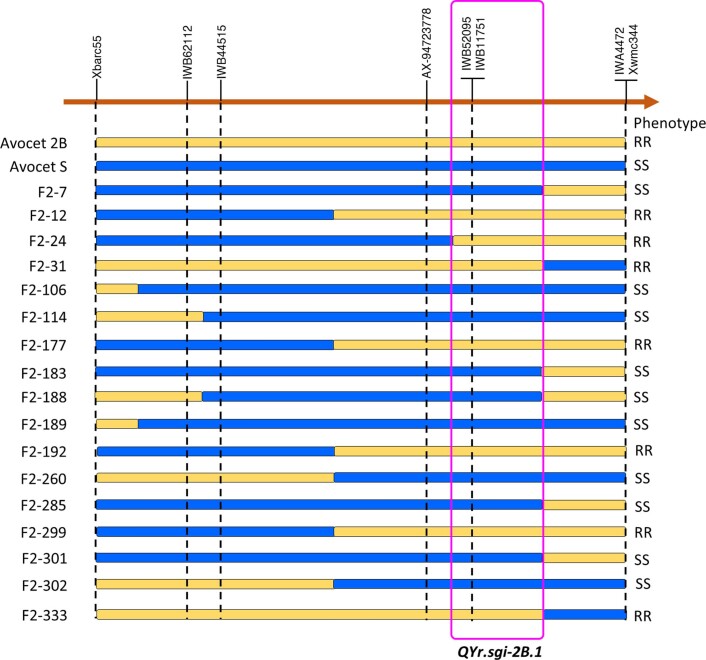

To explore the phenotype conferred by QYr.sgi-2B.1 in the absence of the other two stripe rust resistance QTLs, we backcrossed Kariega with the susceptible spring wheat cultivar Avocet S. The resulting backcross line, Avocet S + QYr.sgi-2B.1 (herein referred to as Avocet 2B), showed moderate seedling resistance and strong adult plant resistance to the South African Pst isolate 6E22A+ (Fig. 1a), but susceptibility to race 30E142A+, which was recently reported in Zimbabwe16, indicating that QYr.sgi-2B.1 is a race-specific disease resistance gene. Using an Avocet 2B × Avocet S F2 population, we mapped QYr.sgi-2B.1 to a genetic interval of 1.4 centimorgans (cM) (Fig. 1b), corresponding to a physical region of 10.02 Mb in the Kariega assembly and containing 93 candidate genes (Fig. 1c). Among these were two genes encoding nucleotide-binding leucine-rich repeat (NLR) proteins, which are intracellular immune receptors associated with plant immunity17. To confirm the identity of QYr.sgi-2B.1, we screened an Avocet 2B mutant population induced with ethyl methanesulfonate (EMS), yielding ten independent mutants that had all lost the QYr.sgi-2B.1-mediated stripe rust resistance (Fig. 1d). All ten mutants harbored an EMS-type (G/C to A/T), nonsynonymous mutation in one of the two NLR genes (TraesKAR2B01G0121530LC) (Fig. 1e). Silencing of this NLR gene in Avocet 2B by virus-induced gene silencing (VIGS) greatly reduced stripe rust resistance (Fig. 1f). In summary, the genetic mapping, ten independent mutants and gene silencing confirm TraesKAR2B01G0121530LC to be the causal gene.

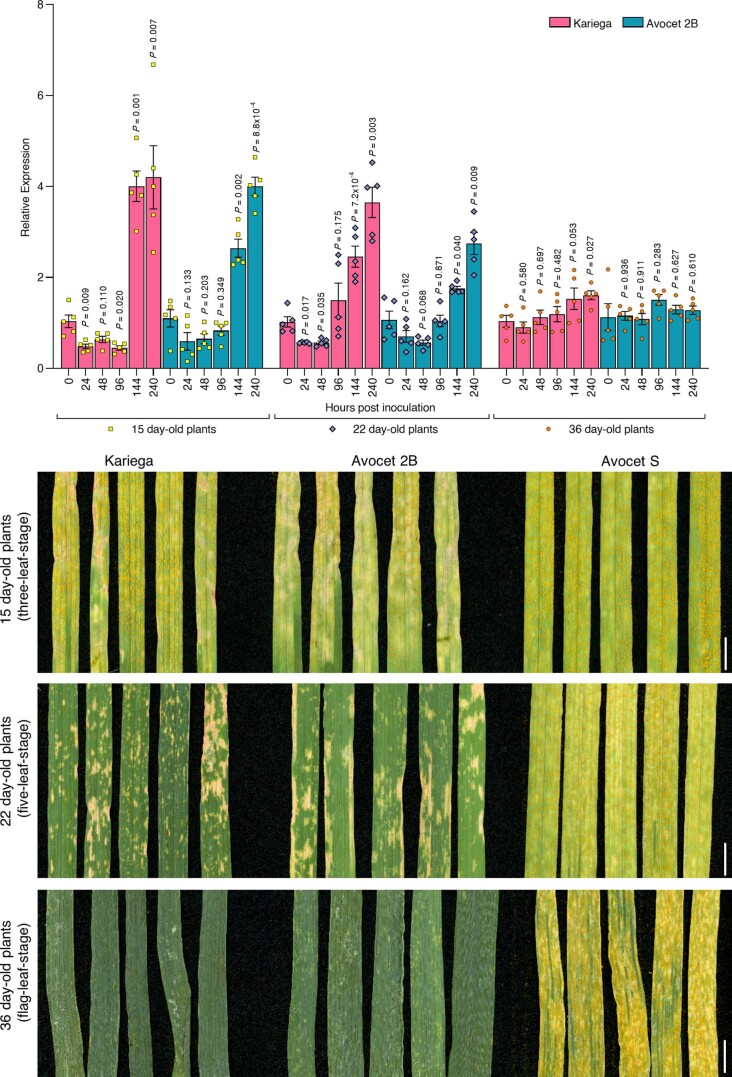

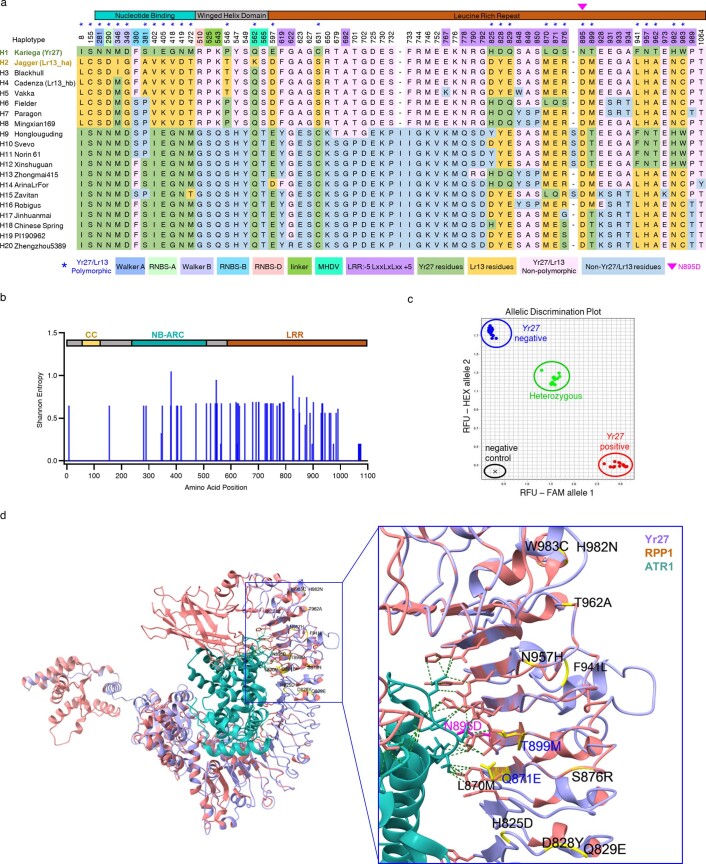

Next we confirmed the structure of the QYr.sgi-2B.1 gene using Kariega Iso-Seq reads. The QYr.sgi-2B.1 gene spans 23.2 kb and consists of four exons, the first two of which correspond to the 5′ untranslated region (UTR). Notably, the first intron is 15.15 kb long (Fig. 1e). The predicted coding sequence with a length of 3,219 base pairs (bp) encodes a protein of 1,072 amino acids with an N-terminal coiled-coil domain, a central NB-ARC domain and a carboxy-terminal leucine-rich repeat (LRR) domain. The QYr.sgi-2B.1 coding sequence was identical in Avocet 2B and Kariega, but polymorphic in Avocet S, confirming that the gene in Avocet 2B was introgressed from Kariega. QYr.sgi-2B.1 transcript levels increased approximately fourfold in seedlings after inoculation with an avirulent Pst isolate, but were not induced or only moderately induced in adult plants (Extended Data Fig. 4). Several Yr genes were genetically assigned to chromosome arm 2BS, including Yr27 and Yr31 (ref. 18). The QYr.sgi-2B.1 coding sequence was identical to that of an NLR gene amplified from several Yr27 reference stocks, including the wheat lines Selkirk, Kauz, Kubsa, Opata 85 and Avocet Yr27 (ref. 19), indicating that QYr.sgi-2B.1 is Yr27. Wheat cultivars containing Yr27 have been widely deployed in regions of South Asia and East Africa prone to stripe rust9,19, resulting in the emergence of Pst races that are virulent to Yr27. The phenotypic expression of Yr27 (previously known as YrSk) at the seedling stage is influenced by the environment and genetic background19,20. We discovered that Yr27 is allelic to the recently cloned leaf rust resistance gene Lr13 (refs. 2,3). NLRs often form complex gene clusters, and it has been found that different members of such allelic series can confer resistance to various fungal pathogens. For example, the powdery mildew resistance gene TmMla1 from diploid einkorn wheat (Triticum monococcum)21 and the Sr33 stem rust resistance gene from the wild wheat progenitor Aegilops tauschii22 are both orthologous to Mla, a complex cluster of NLR genes originally described in barley (Hordeum vulgare)23, and encode proteins with 86% sequence identity. By contrast, Yr27 and Lr13 represent alleles of a single-copy gene (Fig. 1c), and the protein versions that they encode are 97.3% identical, differing in only 29 of 1,072 amino acids (Fig. 1g). Most of the polymorphisms are clustered in two regions: a 192 amino acid stretch in the NB-ARC domain and a 159 amino acid region in the LRR domain (Fig. 1g). Analysis of Shannon entropy, an unbiased measure used to predict rapidly evolving residues24, revealed a higher level of amino acid diversity in the LRR domain among Yr27/Lr13 protein variants present in various wheat cultivars compared with the diversity in the N-terminal coiled-coil and NB-ARC domains (Extended Data Fig. 5a,b). Lr13 results not only in leaf rust resistance, but also in hybrid necrosis in certain genetic backgrounds2,3. Two amino acids in the NB-ARC domain (Ile 346 and Lys 562) of Lr13 are critical for leaf rust resistance specificity2. At the equivalent positions, Yr27 had the same residues as the Lr13_hb haplotype, which lacked resistance to leaf rust but retained the hybrid necrosis phenotype (Extended Data Fig. 5a). A comparison with publicly available wheat sequences7,13,25,26 revealed one amino acid (Asn 895) that was found only in Yr27 (Fig. 1g), which we turned into a Yr27-specific molecular marker for breeding (Extended Data Fig. 5c). Protein modeling predicted that three of the polymorphic residues in the highly variable 159 amino acid region of the Yr27 LRR domain (including the unique Asn 895 amino acid) coincide with the inner surface of the LRR domain (Extended Data Fig. 5d). The corresponding residues of the Arabidopsis thaliana NLR immune receptor RPP1 contribute to the interaction of RPP1 with the ATR1 pathogen effector27. Together, these data might indicate that Yr27 is a highly variable NLR and that the variable stretch in the LRR domain might be important to define recognition specificity.

Extended Data Fig. 4. QYr.sgi-2B.1 expression in Kariega and Avocet 2B after inoculation with an avirulent Pst isolate (6E22A+).

Values and error bars represent means and standard errors of five biological replicates, respectively. Statistical analysis was done using a two-tailed t-test (compared to 0 hours post inoculation). The lower panel shows representative images of leaves harvested at the time of sampling (15 days after inoculation). Scale bar = 1 cm.

Extended Data Fig. 5. Yr27 haplotype analysis, diversity, and homology modelling.

a, Polymorphic residues encoded by Yr27 alleles present in various wheat cultivars. Blue asterisks indicate residues that are polymorphic between Lr13 and Yr27. Functional motifs are indicated in different colors. b, Shannon entropy plot showing amino acid diversity across Yr27 based on the alignment of 20 different haplotypes. c, Yr27-specific KASP marker tested on Yr27 positive, Yr27 negative and heterozygous wheat plants (Avocet 2B x Avocet S F2 population). d, Yr27 model superimposed to the Arabidopsis thaliana RPP1-ATR1 cryo-EM structure. The close-up view shows the RPP1-ATR1 contact interface in the LRR domain. The labeled residues are the ones that were polymorphic between Lr13 and Yr27. The three residues Q871, N895 and T899 are predicted to locate on the inner surface of the LRR domain and the corresponding residues in RPP1 have been shown to form polar interactions with the ATR1 effector (indicated by green dashed lines).

In summary, we have demonstrated the feasibility of generating chromosome-scale wheat assemblies from any wheat line to guide gene cloning projects. The Kariega assembly was completed in a short period of time (<4 months) and for a fraction of the cost of previous chromosome-scale wheat assemblies. Notably, we produced assemblies with lengths greater than 14 Gb from subsets of PacBio HiFi reads, corresponding to ~7.5-fold and ~10.8-fold coverage, with contig N50 lengths of 0.76 Mb and 4.2 Mb, respectively, which might be sufficient for most gene cloning projects (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table 2). Our approach eliminates the need for the time-consuming, laborious complexity reduction required with previous genomics-based gene cloning methods in wheat28–31. NLR genes, including Yr27, are often associated with rapid resistance breakdown when widely deployed. Our results show that the race-specific Yr27 gene is a component of the quantitative and durable stripe rust resistance seen in Kariega. Similarly, the race-specific Lr14a leaf rust resistance gene, which encodes a membrane-bound ankyrin repeat protein, was recently identified as one of several QTLs that contribute to the broad-spectrum and durable leaf rust resistance in the Swiss winter wheat cultivar Forno32. The longevity of the rust resistances in Kariega and Forno might be the result of optimal ‘stacks’ of partial broad-spectrum resistance genes (such as Lr34 (also known as Yr18)) and race-specific R genes, indicating that the optimal deployment of race-specific resistance genes, in combination with partial broad-spectrum resistance genes, can result in near-complete and long-lasting disease resistance. Most notably, Yr27 is an allele of Lr13, indicating that near-identical alleles can confer race-specific resistance to different pathogens. This result may be exploited to engineer NLR versions with multipathogen recognition specificity in the future.

Fig. 2. Total assembly size, contig N50 length and contig N90 length of 20 individual Kariega assemblies.

Assemblies were produced using subsets of the PacBio HiFi data.

Methods

Plant materials

The bread wheat cultivars Kariega and Avocet S, and the near-isogenic line Avocet S + QYr.sgi-2B.1 (Avocet 2B) were used to clone Yr27. Avocet 2B was developed by selfing a BC4F2 plant that was selected from backcross material derived from crossing QYr.sgi-2B.1 from Kariega into the susceptible background of Avocet S1. The resultant BC4F6 material was designated as Avocet 2B. The molecular markers Xbarc55 and Xwmc344 were used to verify the presence of QYr.sgi-2B.1 in Avocet 2B. In addition, Kariega, Avocet S and Avocet 2B were genotyped with a wheat 90K iSelect single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) array33 and a Wheat Breeders’ 35K Axiom Array34, which confirmed that only the QYr.sgi-2B.1 region, and none of the other Kariega stripe rust QTLs, has been introgressed into Avocet 2B (Supplementary Table 6). An F2 mapping population (Avocet 2B × Avocet S; n = 345) segregating for a single dominant stripe rust resistance gene (R:S = 254:91, χ2 = 0.348, P = 0.554) was genotyped with the QYr.sgi-2B.1 flanking markers1 Xbarc55 and Xwmc344 to identify recombinants. Identified recombinants were genotyped with additional Kompetitive Allele Specific PCR (KASP) markers derived from polymorphic iSelect and Axiom 35K SNPs between Avocet S and Avocet 2B (Extended Data Fig. 6 and Supplementary Table 7)35. The following Yr27-carrying lines were obtained from the University of the Free State (UFS) and the Agricultural Research Council - Small Grain in South Africa (SA): Selkirk (UFS31b), Kubsa (SA9399), Kauz (SA6643), Opata 85 (SA8997) and Avocet Yr27 (Yr27/6*AvS; UFS31a).

Extended Data Fig. 6.

Graphical representation of critical recombinants of the Avocet 2B x Avocet S F2 population.

HiFi library preparation and sequencing

High molecular weight DNA was extracted from dark-treated, young Kariega leaves following the protocols of refs. 36,37. DNA purity was assessed on a NanoDrop NP-1000 spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies), DNA concentration was measured with a Qubit dsDNA high-sensitivity assay and DNA size was validated by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE). Ten micrograms of DNA was sheared to the appropriate size range (10–30 kb) using a Covaris g-TUBE for the construction of PacBio HiFi sequencing libraries, followed by bead purification with PB Beads (PacBio). Sequencing libraries were constructed following the manufacturer’s protocol using a SMRTbell Express Template Prep Kit 2.0. Libraries were quantified using the Qubit dsDNA high-sensitivity assay, and size was checked on a Femto Pulse System (Agilent). Sequencing was performed on PacBio Sequel II systems in CCS mode for 30 h.

Optical map production

Grains of Kariega were germinated and grown in the dark on wet filter paper for 4 days at 4 °C and 3 days at 25 °C. One gram of fresh root meristem tissue was fixed and treated according to the Plant DNA Isolation Kit protocol (Bionano Genomics) to recover high molecular weight DNA embedded in agarose plugs. Plugs containing DNA were washed in wash buffer (Bionano Genomics) and Tris-EDTA (TE). After a purification step using a PFGE system (Bio-Rad) to remove smaller DNA fragments (90 min; 5 V cm–1; angle, 120 °C; initial switch time, 1 s; final switch time, 3 s; linear ramping), we proceeded to DNA release using gelase followed by a dialysis according to the protocol (Bionano Genomics). DNA quantity and size were estimated using Qubit (Invitrogen) and PFGE (24 h; 6 V cm–1; angle, 120 °C; initial switch time, 60 s; final switch time, 120 s; linear ramping). DNA was labeled using the DLS protocol (Bionano Genomics). Labeled molecules were produced using the Saphyr System (Saphyr Chip G1.2). Data processing was performed using the Bionano Solve v.3.6 software (https://bionanogenomics.com/support/software-downloads).

Omni-C library preparation and sequencing

The Omni-C library was prepared using the Dovetail Omni-C Kit according to the manufacturer’s protocol. In brief, chromatin was fixed in place in the nucleus. Fixed chromatin was digested with DNase I and then extracted. Chromatin ends were repaired and ligated to a biotinylated bridge adapter, before proximity ligation of adapter containing ends. After proximity ligation, crosslinks were reversed and the DNA was purified from proteins. Purified DNA was treated to remove biotin that was not internal to ligated fragments. Four sequencing libraries were generated using Illumina-compatible adapters. Biotin-containing fragments were isolated using streptavidin beads before PCR enrichment of the library. The four libraries were sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq X platform to generate 834 million 2 × 150 bp read pairs.

RNA-Seq and Iso-Seq library preparation and sequencing

Total RNA was extracted from seedlings, seedlings at dusk, flag leaves, grains, roots and spikes. In brief, 100 mg of ground powder from each tissue was used for RNA isolation using a Maxwell RSC Plant RNA Kit (AS1500) with a Maxwell RSC48 instrument as indicated in the kit protocol (Promega). Around 20 Gb of 2 × 150 bp reads were generated for each sample. The Iso-Seq SMRTbell library was constructed according to the standard isoform sequencing protocol (Pacific Biosciences, 101-763-800) using the NEBNext Single Cell/Low Input cDNA Synthesis & Amplification Module (New England Biolabs, E6421S) and the ProNex Size-Selective Purification System (Promega, NG2001) for size selection. In brief, 300 ng of total RNA from each of the six developmental stages was used as input for complementary DNA synthesis. Each sample was first barcoded and then subjected to cDNA amplification using 12 cycles. Purified cDNAs were pooled in equal molarity and then subjected to library preparation using the SMRTbell Express Template Prep Kit 2.0 (Pacific Biosciences, 100-938-900) following the Iso-Seq protocol previously referenced. The library was prepared for sequencing by annealing primer v4 with the Sequel II Binding Kit 2.1 and the Internal Control Kit 1.0 (Pacific Biosciences, 101-843-000). One SMRT Cell 8M (Pacific Biosciences, 101-389-001) was sequenced on the PacBio Sequel II system using the Sequencing Kit 2.0 (Pacific Biosciences, 101-820-200). The IsoSeq pipeline (v.3; https://github.com/PacificBiosciences/IsoSeq) was used for CCS generation, demultiplexing and clustering of the six datasets.

Genome assembly and validation

The PacBio HiFi reads were assembled using hifiasm12 (v.0.11) with default parameters. Hybrid scaffolding incorporating the PacBio contigs and the optical map was performed using the hybridScaffold pipeline (Bionano Solve 3.6) with default parameters. For the pseudomolecule construction, the Omni-C reads were incorporated using Juicer tools38 (v.1.6) and 3D-DNA39 (v.180114). In brief, the preprocessing of the Omni-C reads was performed with juicer.sh (parameter: -s none). The ‘merged_nodups.txt’ output file corresponding to the Hi-C contacts with duplicates removed was subsequently used with run-asm-pipeline.sh (parameter: -r 0) as input to produce the ‘.hic’ and ‘.assembly’ files. These files were uploaded into Juicebox40 (v.1.11.08) to visualize the Hi-C map and for manual curation. As a final step, the script run-asm-pipeline-post-review.sh (default parameters) was used to save the final Hi-C contact map and to output the final Kariega assembly (21 pseudomolecules and 1 unanchored pseudochromosome). To validate the genome assembly, we remapped the optical map onto the pseudomolecule using the hybridScaffold pipeline (Bionano Solve 3.6), and the final pseudomolecules were compared with the recent bread wheat assemblies of Chinese Spring (IWGSC RefSeq v.2.1)41 and the assemblies of the 10+ Wheat Genomes Project7 using MashMap42 (v.2.0; parameter: -s 300000–pi 98).

Gene model prediction

Gene model prediction was performed following the method described by Mascher et al.5 with minor modifications, combining transcriptomics data, protein homology and ab initio prediction. First, the RNA-Seq data from the six developmental stages were mapped to the reference assembly using STAR43 (v.2.7.0f; parameter:–outFilterMismatchNoverReadLmax 0.02) and assembled into transcripts with StringTie44 (v.2.1.4; parameter:–rf -m 150 -f 0.3 -t). Iso-Seq data were mapped using minimap245 (v.2.17-r941; parameter: -ax splice -uf –secondary=no -C5), and the redundant isoforms were further collapsed into transcript loci using cDNA_Cupcake (http://github.com/Magdoll/cDNA_Cupcake; parameter:–dun-merge-5-shorter). The RNA-Seq and Iso-Seq transcripts were merged using StringTie (parameters:–merge -m 150) into a pool of candidate transcripts, and TransDecoder (v.5.5.0; https://github.com/TransDecoder/TransDecoder) was used to find potential open reading frames and to predict protein sequences within the candidate transcript set. For the protein homology evidences, we used the translated proteins from the projected gene annotation of the 10+ Wheat Genomes Project7, the IWGSC RefSeq v.2.141 and the Triticeae protein sequences downloaded from the UniProt database (2021_03). All of the proteins were mapped against the Kariega assembly using GenomeThreader46 (v.1.7.1; parameters: -startcodon -finalstopcodon -species rice -gcmincoverage 70 -prseedlength 7 -prhdist 4 -gff3out). Then, we produced ab initio gene predictions using AUGUSTUS47 (v.3.4.0), GeneMark48 (v.4.38) and Fgenesh (v.8.0.0; http://www.softberry.com). In brief, AUGUSTUS gene prediction was performed using a model specifically trained according to Hoff and Stanke49 and a hints file generated using the previously mentioned Iso-Seq and RNA-Seq predictions. GeneMark was used with the option -ET and the intron coordinates calculated with the perl script star_to_gff.pl provided in the GeneMark package. For the Fgenesh prediction, the Kariega pseudomolecules were repeat masked using a de novo repeat library constructed with the Extensive de novo TE Annotator (EDTA) pipeline50 and the TREP database51 (v.19). Fgenesh annotation was performed with the specific Triticum aestivum matrix for the gene prediction. We used EVidenceModeler52 (v.1.1.1) to join all of the gene evidences from transcriptomics, protein alignments and ab initio predictions with weights adjusted according to the input source (Fgenesh, 2; AUGUSTUS, 1; GeneMark, 1; protein homology, 5; transcriptomics, 12). Finally, we performed two rounds of isoform and UTR prediction using the Program to Assemble Spliced Alignments (PASA) pipeline53 with default parameters. Gene models were classified as high-confidence or low-confidence genes according to criteria used by the International Wheat Genome Sequencing Consortium13 and by Mascher et al.5. In brief, protein-encoding gene models were considered complete when start and stop codons were present. A comparison with PTREP51, UniPoa (Poaceae database of annotated proteins from the UniProt database (2021_03)) and UniViri (Viridiplantae database) was performed using DIAMOND54 (v.2.0.9; parameters: -e 1e-10–query-cover 80–subject-cover 80). Gene candidates were further classified using the following criteria: a high-confidence gene model is complete with a hit in the UniViri database and/or in UniPoa and not PTREP; a low-confidence gene model is incomplete and has a hit in the UniViri or UniPoa database but not in PTREP, or the protein sequence is complete with no hit in UniViri, UniPoa or PTREP. Putative functional annotations were assigned to high-confidence and low-confidence genes using a protein comparison with the UniProt database (2021_03). The detection of putative NLR loci on each of the pseudomolecules was performed using the NLR-Annotator pipeline55 with default parameters.

Stripe rust inoculations

Stripe rust inoculations at seedling and adult plant stages were performed with urediniospores of the South African Pst pathotype 6E22A+ (virulent to Yr2, Yr6, Yr7, Yr8, Yr17, Yr25 and YrA; avirulent to Yr1, Yr3a, Yr4a, Yr4b, Yr5, Yr9, Yr10, Yr15 and Yr27)56 and pathotype 30E142A+16 (virulent to Yr2, Yr3a, Yr4a, Yr6, Yr7, Yr8, Yr9, Yr19, Yr25, Yr27 and YrA; avirulent to Yr1, Yr4b, Yr5, Yr10, Yr15, Yr24, Yr32, YrCle, YrMor, YrSd, YrSp, YrSu and YrHVII). In brief, freshly propagated urediniospores were suspended in FC-43 oil (3M Fluorinert FC-43) and then sprayed onto the leaves using a high-pressure air sprayer. After inoculation, the plants were placed in a plastic box (56 × 39 × 42 cm), sprayed with Milli-Q water to maintain a high level of humidity and kept in the dark for 24 h at 4 °C. Then, plants were moved to a growth chamber with a 16/8 h day/night regime with the temperature set to 21/18 °C. At 15 days after inoculation, stripe rust phenotypes were recorded by scanning the leaves at 600 dots per inch on an Epson Perfection V850 Pro scanner.

EMS mutagenesis

EMS mutagenesis of Avocet 2B was performed with a concentration of 0.6% EMS (Sigma-Aldrich, M0880). About 2,000 grains were soaked in water at 4 °C for 16 h, dried for 8 h on filter paper and incubated for 16 h with shaking at room temperature (23 °C) in the EMS solution. Next, the grains were washed three times for 45 min each and rinsed for 30 min under running tap water. Grains were pregerminated on humid filter paper in the dark at 4 °C for 48 h. The pregerminated grains were planted in 24-well trays (six grains per well) filled with Stender potting soil in a greenhouse illuminated with Heliospectra LX602C light-emitting diode (LED) grow lights (20/4 h day/night regime with temperature set to 21/18 °C). Single spikes of M0 plants were harvested, and at least ten M1 progenies per M0 plant were phenotyped at the flag leaf stage with Pst pathotype 6E22A+ to identify susceptible candidate mutant lines, which were validated in the M2 and M3 generations.

Genetic map

Linkage analysis was performed using MapDisto 2.057 with default parameters such as LOD (logarithm of the odds) threshold of 3.0, maximum recombination frequency of 0.3 and removal of loci with 10% missing data. Genetic distances were calculated using the Kosambi mapping function, and the map was created using MapChart58. A graphical representation of critical recombinants of the Avocet 2B × Avocet S population is shown in Extended Data Fig. 6.

PCR conditions

A 20 μl PCR containing 100 ng of genomic DNA, 1× GoTaq Green Master Mix (Promega, M7122) and 200 nM primers was used for various fragment amplifications. Primer sequences are shown in Supplementary Table 7. A touchdown PCR protocol was used as follows: initial denaturation at 94 °C for 30 s; annealing at 62 °C for 30 s, decreasing by 0.5 °C per cycle; and extension at 72 °C for 60 s, followed by repeating these steps for eight cycles. After enrichment, the program continued for 29 cycles as follows: 94 °C for 30 s, 58 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 60 s. A 20 μl PCR with Phusion High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (New England Biolabs, M0530) was performed to verify the Yr27 gene sequence and to clone the silencing fragments following the manufacturer’s instructions. A 5 μl reaction (2.5 μl of KASP Master Mix (Low ROX KBS-1016-016), 0.07 μl of assay mix and 2.5 μl (25 ng) of DNA) was used for KASP markers. PCR cycling was performed in an ABI QuantStudio 6 Flex Real-Time PCR machine as follows: preread at 30 °C for 60 s; hold stage at 94 °C for 15 min; and then ten touchdown cycles (94 °C for 20 s; touchdown at 61 °C, decreasing by 0.6 °C per cycle for 60 s), followed by 29 additional cycles (94 °C for 20 s; 55 °C for 60 s). The plates were then read at 30 °C for endpoint fluorescent measurement.

Candidate gene identification

To identify the candidate gene for QYr.sgi-2B.1, we anchored the flanking markers AX-94723778 and IWA4472 to the Kariega pseudomolecules. Annotated high-confidence genes and putative NLR loci predicted by NLR-Annotator55 at the delimited physical interval were selected as putative candidate genes. NLRs predicted at the target interval were prioritized for further analysis. First, the Kariega NLR sequences were screened for homology using the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) to identify the sequence diversity between Kariega and other wheat cultivars. Second, exon sequences of the shortlisted NLRs were amplified from Kariega, Avocet 2B and the ten susceptible EMS mutants. The amplicons were Sanger sequenced to identify and verify EMS mutations. Primers 2BNLR5F3/R8 and 2BNLR5F10/R12 were used to amplify exon sequences of QYr.sgi-2B.1 (Supplementary Table 7).

VIGS

To develop the VIGS probes, the predicted QYr.sgi-2B.1 coding sequence was searched against the Kariega whole transcriptome (RNA-Seq and Iso-Seq) database using siRNA-Finder (si-Fi) software59. Based on the RNA interference (RNAi) design plot, three regions (Si1 (197 bp) in the 5′ UTR, Si2 (200 bp), and Si3 (198 bp) in the coding sequence) were selected for VIGS. The selected probes were verified for specificity using a BLAST search against the Kariega genome assembly (<80% sequence identity for hits other than Yr27). The target sequences were cloned into the pBS-BSMV-γ (BSMV, barley stripe mosaic virus) vector in an antisense direction60,61. Viral RNAs of BSMV–GFP and BSMV–GUS were used as controls, along with the BSMV–Si1, BSMV–Si2 and BSMV–Si3 constructs to infect the plants. In brief, Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101 carrying the viral pBS-BSMV-α, pBS-BSMV-β and pBS-BSMV-γ plasmids, with the γ plasmid carrying the VIGS target sequence, was infiltrated into Nicotiana benthamiana. Infiltrated leaves were harvested 4 days after inoculation and homogenized with virus inoculation buffer. The leaf extracts were used to infect 15-day-old wheat plants. Then, seedlings were placed in a growth chamber (60% humidity, 16/8 h light/dark regime with temperature set to 21/18 °C). At the flag leaf stage (approximately 20 days after viral infection), stripe rust inoculation was carried out, and the flag leaves were phenotyped 15 days after inoculation.

Quantitative real-time PCR

Leaf materials inoculated with stripe rust were collected at different time points in five biological replicates for RNA isolation. RNA extraction was done using the Maxwell RSC Plant RNA kit and the Maxwell RSC48 instrument (Promega). One microgram of RNA was used for the first-strand cDNA synthesis using a High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit following the user guidelines (Applied Biosystems, 4368814). cDNA was further diluted 20-fold, and 4 μl of diluted cDNA were used for qPCR (quantitative real-time PCR). qPCR was performed using the 2BNLR5F17/R11 primers (Supplementary Table 7). A 20 μl qPCR was set up and run on the ABI QuantStudio 6 Flex Real-Time PCR machine using PowerUp SYBR Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, AS25741). The method was used to normalize transcript values relative to endogenous controls Ta.6863 (ref. 62).

Haplotype analysis, Shannon entropy and homology modeling

Yr27 protein versions were retrieved from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) using a protein BLAST search (Supplementary Table 8) and aligned using MUSCLE in Geneious Prime 2019. Haplotypes were classified based on amino acid variations (Extended Data Fig. 5a). To identify residues overlapping functional motifs, the Motif Alignment Search Tool (MAST v.5.3.3)63 was used to predict the predefined NLR motifs64 and LRRpredictor was used to predict canonical LXXLXLXX repeats65. Shannon entropy values were calculated using the Entropy-one tool in the HIV sequence database (https://www.hiv.lanl.gov/content/sequence/ENTROPY/entropy_one.html). The raw output values were plotted using GraphPad Prism v.9.2.0. The Yr27 amino acid sequence was submitted to the Protein Homology/analogY Recognition Engine v.2.0 (Phyre2) for homology modeling to predict the three-dimensional structure66. The resulting top two Yr27 models comprise residues D87 to L1060 (90%) aligned to RPP1 with 18% identity and 100% confidence, and residues P43 to I977 (87%) aligned to ZAR1 with 22% identity and 100% confidence. The coordinates of RPP1-CJID-ATR1 and ZAR1-RKS1-PBL2 cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) structures were retrieved from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) (7CRC27 and 6J5T67) for further analysis. Based on the structure analysis, graphical illustrations were created in UCSF ChimeraX v.1.3dev2021 software68 using RPP1-CJID-ATR1 as reference.

Reporting Summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Online content

Any methods, additional references, Nature Research reporting summaries, source data, extended data, supplementary information, acknowledgements, peer review information; details of author contributions and competing interests; and statements of data and code availability are available at 10.1038/s41588-022-01022-1.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Tables 1–8.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to L. Zhou and V. Venkataraman for technical assistance, and the King Abdullah University of Science and Technology (KAUST) Bioscience Core Lab for sequencing support. We thank H. Šimková from the Institute of Experimental Botany, Czech Republic, for technical advice. This publication is based on work supported by the South African Winter Cereal Trust (Grant WCT/W/2020/04) and the KAUST Office of Sponsored Research (OSR) under award no. OSR-CRG2018-3768.

Extended data

Author contributions

N.A., M.A., W.H.P.B., R.P. and S.G.K. designed the study. W.H.P.B. and R.P. developed germ plasm. N.A., K.S.B. and S.S.D. performed molecular experiments. S.C., N.R., D.K., N.M. and R.A.W. generated genomic raw data. M.A. and S.C. performed assemblies and analyzed genomic data. N.A., W.H.P.B. and J.B. performed rust inoculations and phenotypic scorings. N.A., M.A. and S.G.K. wrote the initial version of the paper. All authors contributed to subsequent versions and have read and approved the manuscript.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Genetics thanks Luigi Cattivelli, Ksenia V. Krasileva, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Data availability

Data supporting the findings of this work are available within the paper and its Supplementary Information. The raw sequencing data used for de novo whole-genome assembly, CCS reads, raw bionano map, Omni-C reads, Kariega genome assembly, RNA-Seq data and Iso-Seq data for the annotation are available on the European Bioinformatics Institute (EBI) European Nucleotide Archive (ENA) under study number PRJEB45541. The Yr27 coding sequence and genomic sequences have been deposited in the ENA under accession numbers OU248057 and OU248342, respectively. The whole-genome assembly and annotations of gene models, repeats and NLRs are available on the DRYAD database (10.5061/dryad.nk98sf7td).

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Naveenkumar Athiyannan, Michael Abrouk, Willem H. P. Boshoff.

Contributor Information

Renée Prins, Email: cengen@cengen.co.za.

Simon G. Krattinger, Email: simon.krattinger@kaust.edu.sa

Extended data

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41588-022-01022-1.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41588-022-01022-1.

References

- 1.Agenbag GM, et al. High-resolution mapping and new marker development for adult plant stripe rust resistance QTL in the wheat cultivar Kariega. Mol. Breed. 2014;34:2005–2020. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hewitt T, et al. Wheat leaf rust resistance gene Lr13 is a specific Ne2 allele for hybrid necrosis. Mol. Plant. 2021;14:1025–1028. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2021.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yan X, et al. High-temperature wheat leaf rust resistance gene Lr13 exhibits pleiotropic effects on hybrid necrosis. Mol. Plant. 2021;14:1029–1032. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2021.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wenger AM, et al. Accurate circular consensus long-read sequencing improves variant detection and assembly of a human genome. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019;37:1155–1162. doi: 10.1038/s41587-019-0217-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mascher M, et al. Long-read sequence assembly: a technical evaluation in barley. Plant Cell. 2021;33:1888–1906. doi: 10.1093/plcell/koab077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nurk, S. et al. The complete sequence of a human genome. Preprint at https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.05.26.445798v1 (2021).

- 7.Walkowiak S, et al. Multiple wheat genomes reveal global variation in modern breeding. Nature. 2020;588:277–283. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2961-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abrouk M, et al. Population genomics and haplotype analysis in spelt and bread wheat identifies a gene regulating glume color. Commun. Biol. 2021;4:375. doi: 10.1038/s42003-021-01908-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ali S, et al. Yellow rust epidemics worldwide were caused by pathogen races from divergent genetic lineages. Front. Plant Sci. 2017;8:1057. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.01057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hafeez AN, et al. Creation and judicious application of a wheat resistance gene atlas. Mol. Plant. 2021;14:1053–1070. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2021.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krattinger SG, et al. A putative ABC transporter confers durable resistance to multiple fungal pathogens in wheat. Science. 2009;323:1360–1363. doi: 10.1126/science.1166453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cheng H, Concepcion GT, Feng X, Zhang H, Li H. Haplotype-resolved de novo assembly using phased assembly graphs with hifiasm. Nat. Methods. 2021;18:170–175. doi: 10.1038/s41592-020-01056-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.The International Wheat Genome Sequencing Consortium et al. Shifting the limits in wheat research and breeding through a fully annotated and anchored reference genome sequence. Science. 2018;361:eaar7191. doi: 10.1126/science.aar7191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alonge M, Shumate A, Puiu D, Zimin AV, Salzberg SL. Chromosome-scale assembly of the bread wheat genome reveals thousands of additional gene copies. Genetics. 2020;216:599–608. doi: 10.1534/genetics.120.303501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seppey, M., Manni, M. & Zdobnov, E. M. in Gene Prediction: Methods and Protocols (ed. Kollmar, M.) 227–245 (Springer, 2019).

- 16.Boshoff WHP, et al. First report of Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici, causing stripe rust of wheat, in Zimbabwe. Plant Dis. 2020;104:290. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kourelis J, van der Hoorn RAL. Defended to the nines: 25 years of resistance gene cloning identifies nine mechanisms for R protein function. Plant Cell. 2018;30:285–299. doi: 10.1105/tpc.17.00579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ramburan VP, et al. A genetic analysis of adult plant resistance to stripe rust in the wheat cultivar Kariega. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2004;108:1426–1433. doi: 10.1007/s00122-003-1567-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McDonald DB, McIntosh RA, Wellings CR, Singh RP, Nelson JC. Cytogenetical studies in wheat XIX. Location and linkage studies on gene Yr27 for resistance to stripe (yellow) rust. Euphytica. 2004;136:239–248. [Google Scholar]

- 20.McIntosh, R. A., Wellings, C. R. & Park, R. F. Wheat Rusts: An Atlas of ResistanceGenes (CSIRO, 1995).

- 21.Jordan T, et al. The wheat Mla homologue TmMla1 exhibits an evolutionarily conserved function against powdery mildew in both wheat and barley. Plant J. 2011;65:610–621. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04445.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Periyannan S, et al. The gene Sr33, an ortholog of barley Mla genes, encodes resistance to wheat stem rust race Ug99. Science. 2013;341:786–788. doi: 10.1126/science.1239028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wei F, Wing RA, Wise RP. Genome dynamics and evolution of the Mla (powdery mildew) resistance locus in barley. Plant Cell. 2002;14:1903–1917. doi: 10.1105/tpc.002238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Prigozhin DM, Krasileva KV. Analysis of intraspecies diversity reveals a subset of highly variable plant immune receptors and predicts their binding sites. Plant Cell. 2021;33:998–1015. doi: 10.1093/plcell/koab013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Avni R, et al. Wild emmer genome architecture and diversity elucidate wheat evolution and domestication. Science. 2017;357:93–97. doi: 10.1126/science.aan0032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maccaferri M, et al. Durum wheat genome highlights past domestication signatures and future improvement targets. Nat. Genet. 2019;51:885–895. doi: 10.1038/s41588-019-0381-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ma S, et al. Direct pathogen-induced assembly of an NLR immune receptor complex to form a holoenzyme. Science. 2020;370:eabe3069. doi: 10.1126/science.abe3069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sánchez-Martín J, et al. Rapid gene isolation in barley and wheat by mutant chromosome sequencing. Genome Biol. 2016;17:221. doi: 10.1186/s13059-016-1082-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Steuernagel B, et al. Rapid cloning of disease-resistance genes in plants using mutagenesis and sequence capture. Nat. Biotechnol. 2016;34:652–655. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thind AK, et al. Rapid cloning of genes in hexaploid wheat using cultivar-specific long-range chromosome assembly. Nat. Biotechnol. 2017;35:793–796. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Arora S, et al. Resistance gene cloning from a wild crop relative by sequence capture and association genetics. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019;37:139–143. doi: 10.1038/s41587-018-0007-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kolodziej MC, et al. A membrane-bound ankyrin repeat protein confers race-specific leaf rust disease resistance in wheat. Nat. Commun. 2021;12:956. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-20777-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang S, et al. Characterization of polyploid wheat genomic diversity using a high-density 90,000 single nucleotide polymorphism array. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2014;12:787–796. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Allen AM, et al. Characterization of a Wheat Breeders’ Array suitable for high-throughput SNP genotyping of global accessions of hexaploid bread wheat (Triticum aestivum) Plant Biotechnol. J. 2017;15:390–401. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ramirez-Gonzalez RH, et al. RNA-Seq bulked segregant analysis enables the identification of high-resolution genetic markers for breeding in hexaploid wheat. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2015;13:613–624. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dellaporta SL, Wood J, Hicks JB. A plant DNA minipreparation: version II. Plant Mol. Biol. Report. 1983;1:19–21. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mayjonade B, et al. Extraction of high-molecular-weight genomic DNA for long-read sequencing of single molecules. BioTechniques. 2016;61:203–205. doi: 10.2144/000114460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Durand NC, et al. Juicer provides a one-click system for analyzing loop-resolution Hi-C experiments. Cell Syst. 2016;3:95–98. doi: 10.1016/j.cels.2016.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dudchenko O, et al. De novo assembly of the Aedes aegypti genome using Hi-C yields chromosome-length scaffolds. Science. 2017;356:92–95. doi: 10.1126/science.aal3327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Durand NC, et al. Juicebox provides a visualization system for Hi-C contact maps with unlimited zoom. Cell Syst. 2016;3:99–101. doi: 10.1016/j.cels.2015.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhu T, et al. Optical maps refine the bread wheat Triticum aestivum cv. Chinese Spring genome assembly. Plant J. 2021;107:303–314. doi: 10.1111/tpj.15289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jain C, Koren S, Dilthey A, Phillippy AM, Aluru S. A fast adaptive algorithm for computing whole-genome homology maps. Bioinformatics. 2018;34:i748–i756. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dobin A, et al. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics. 2013;29:15–21. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pertea M, et al. StringTie enables improved reconstruction of a transcriptome from RNA-seq reads. Nat. Biotechnol. 2015;33:290–295. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li H. Minimap2: pairwise alignment for nucleotide sequences. Bioinformatics. 2018;34:3094–3100. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gremme G, Brendel V, Sparks ME, Kurtz S. Engineering a software tool for gene structure prediction in higher organisms. Inf. Softw. Technol. 2005;47:965–978. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stanke M, Waack S. Gene prediction with a hidden Markov model and a new intron submodel. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:ii215–ii225. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Borodovsky M, Lomsadze A. Eukaryotic gene prediction using GeneMark.hmm-E and GeneMark-ES. Curr. Protoc. Bioinf. 2011;35:4.6.1–4.6.10. doi: 10.1002/0471250953.bi0406s35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hoff KJ, Stanke M. Predicting genes in single genomes with AUGUSTUS. Curr. Protoc. Bioinf. 2019;65:e57. doi: 10.1002/cpbi.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ou S, et al. Benchmarking transposable element annotation methods for creation of a streamlined, comprehensive pipeline. Genome Biol. 2019;20:275. doi: 10.1186/s13059-019-1905-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wicker T, Matthews DE, Keller B. TREP: a database for Triticeae repetitive elements. Trends Plant Sci. 2002;7:561–562. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Haas BJ, et al. Automated eukaryotic gene structure annotation using EVidenceModeler and the Program to Assemble Spliced Alignments. Genome Biol. 2008;9:R7. doi: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-1-r7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Haas BJ, et al. Improving the Arabidopsis genome annotation using maximal transcript alignment assemblies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:5654–5666. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Buchfink B, Xie C, Huson DH. Fast and sensitive protein alignment using DIAMOND. Nat. Methods. 2015;12:59–60. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Steuernagel B, et al. The NLR-Annotator tool enables annotation of the intracellular immune receptor repertoire. Plant Physiol. 2020;183:468–482. doi: 10.1104/pp.19.01273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Maree GJ, et al. Phenotyping Kariega × Avocet S doubled haploid lines containing individual and combined adult plant stripe rust resistance loci. Plant Pathol. 2019;68:659–668. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Heffelfinger C, Fragoso CA, Lorieux M. Constructing linkage maps in the genomics era with MapDisto 2.0. Bioinformatics. 2017;33:2224–2225. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btx177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Voorrips RE. MapChart: software for the graphical presentation of linkage maps and QTLs. J. Heredity. 2002;93:77–78. doi: 10.1093/jhered/93.1.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lück S, et al. siRNA-Finder (si-Fi) software for RNAi-target design and off-target prediction. Front. Plant Sci. 2019;10:1023. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2019.01023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yuan C, et al. A high throughput barley stripe mosaic virus vector for virus induced gene silencing in monocots and dicots. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e26468. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lee W-S, Rudd JJ, Kanyuka K. Virus induced gene silencing (VIGS) for functional analysis of wheat genes involved in Zymoseptoria tritici susceptibility and resistance. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2015;79:84–88. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2015.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Koller T, Brunner S, Herren G, Hurni S, Keller B. Pyramiding of transgenic Pm3 alleles in wheat results in improved powdery mildew resistance in the field. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2018;131:861–871. doi: 10.1007/s00122-017-3043-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bailey TL, Johnson J, Grant CE, Noble WS. The MEME Suite. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:W39–W49. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jupe F, et al. Identification and localisation of the NB-LRR gene family within the potato genome. BMC Genomics. 2012;13:75. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-13-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Martin EC, et al. LRRpredictor—a new LRR motif detection method for irregular motifs of plant NLR proteins using an ensemble of classifiers. Genes. 2020;11:286. doi: 10.3390/genes11030286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kelley LA, Mezulis S, Yates CM, Wass MN, Sternberg MJE. The Phyre2 web portal for protein modeling, prediction and analysis. Nat. Protoc. 2015;10:845–858. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2015.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wang J, et al. Reconstitution and structure of a plant NLR resistosome conferring immunity. Science. 2019;364:eaav5870. doi: 10.1126/science.aav5870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pettersen EF, et al. UCSF ChimeraX: structure visualization for researchers, educators, and developers. Protein Sci. 2021;30:70–82. doi: 10.1002/pro.3943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Tables 1–8.

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting the findings of this work are available within the paper and its Supplementary Information. The raw sequencing data used for de novo whole-genome assembly, CCS reads, raw bionano map, Omni-C reads, Kariega genome assembly, RNA-Seq data and Iso-Seq data for the annotation are available on the European Bioinformatics Institute (EBI) European Nucleotide Archive (ENA) under study number PRJEB45541. The Yr27 coding sequence and genomic sequences have been deposited in the ENA under accession numbers OU248057 and OU248342, respectively. The whole-genome assembly and annotations of gene models, repeats and NLRs are available on the DRYAD database (10.5061/dryad.nk98sf7td).