Abstract

Objectives

To assess the efficacy of inhaled ciclesonide in reducing the risk of adverse outcomes in COVID-19 outpatients at risk of developing severe illness.

Methods

COVERAGE is an open-label, randomized controlled trial. Outpatients with documented COVID-19, risk factors for aggravation, symptoms for ≤7 days, and absence of criteria for hospitalization are randomly allocated to either a control arm or one of several experimental arms, including inhaled ciclesonide. The primary efficacy endpoint is COVID-19 worsening (hospitalization, oxygen therapy at home, or death) by Day 14. Other endpoints are adverse events, maximal follow-up score on the WHO Ordinal Scale for Clinical Improvement, sustained alleviation of symptoms, cure, and RT-PCR and blood parameter evolution at Day 7. The trial's Safety Monitoring Board reviewed the first interim analysis of the ciclesonide arm and recommended halting it for futility. The results of this analysis are reported here.

Results

The analysis involved 217 participants (control 107, ciclesonide 110), including 111 women and 106 men. Their median age was 63 years (interquartile range 59–68), and 157 of 217 (72.4%) had at least one comorbidity. The median time since first symptom was 4 days (interquartile range 3–5). During the 28-day follow-up, 2 participants died (control 2/107 [1.9%], ciclesonide 0), 4 received oxygen therapy at home and were not hospitalized (control 2/107 [1.9%], ciclesonide 2/110 [1.8%]), and 24 were hospitalized (control 10/107 [9.3%], ciclesonide 14/110 [12.7%]). In intent-to-treat analysis of observed data, 26 participants reached the composite primary endpoint by Day 14, including 12 of 106 (11.3%, 95% CI: 6.0%–18.9%) in the control arm and 14 of 106 (13.2%; 95% CI: 7.4–21.2%) in the ciclesonide arm. Secondary outcomes were similar for both arms.

Discussion

Our findings are consistent with the European Medicines Agency's COVID-19 task force statement that there is currently insufficient evidence that inhaled corticosteroids are beneficial for patients with COVID-19.

Keywords: COVID-19, Randomized controlled trial, Ciclesonide, Adults, Outpatients, Treatment, Inhaled corticosteroids

Introduction

Older people and people with comorbid conditions are at increased risk of adverse outcomes from COVID-19 [[1], [2], [3]]. COVID-19 can also affect the health system by overwhelming inpatient care and oxygen supply capacities. There is therefore a need for treatments that could reduce the risk of COVID-19-related hospitalization, oxygen indication, and death. These treatments should have a good safety profile and be administered as early as possible in outpatient care. Since the rationale underpinning the treatment of COVID-19 in patients with recent symptoms is primarily antiviral, the treatment should be active against SARS-CoV-2 [4].

There was no treatment for β-coronavirus infections at the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic. In the hope of obtaining rapid results, the research community sought to repurpose drugs with other indications that were already in use and therefore had a known tolerance profile. These drugs were chosen for clinical trials on the basis of preclinical arguments, including in vitro anti-SARS-CoV-2 activity and in vivo efficacy against SARS-CoV-2 in various types of animal. The number of molecules with in vitro anti-SARS-CoV-2 activity was potentially large, and clinical trials had to be adaptive to take into account the most recent data in real time and prioritize the most promising drugs [[5], [6], [7], [8], [9]].

In this context, we initiated a trial (COVERAGE) to study the efficacy of several repurposed drugs for early outpatient treatment of COVID-19. One of the treatments studied was inhaled ciclesonide. Ciclesonide has a favourable safety profile and anti-inflammatory properties for the respiratory tract [10]. The onset of action is faster with ciclesonide than with budesonide for improving lung function in asthmatic patients [11]. Ciclesonide also has in vitro activity against SARS-CoV-2 and MERS-CoV, with a half-maximal effective concentration of 0.55 μM in differentiated human bronchial and tracheal epithelial cells [[12], [13], [14]].

The COVERAGE trial allows the withdrawal of molecules for safety or futility reasons [8,9]. Presented here are the results of the first interim futility analysis of ciclesonide.

Methods

Study design

COVERAGE France is a phase-3, multicentre, open-label, randomized controlled trial of COVID-19 early treatment. The trial began in April 2020 and is currently underway at 14 trial centres in 9 French regions (Appendix S1, section SA1-2). The full original version and current version of the protocol are shown in Appendix S2.

The trial participants are randomly allocated to a control arm or one of the experimental arms ongoing at the time. For each experimental arm, the trial involves two phases: a pilot phase, the objective of which is to assess the safety of the drug in outpatients with COVID-19; and an efficacy phase, the objective of which is to assess the drug's efficacy in reducing the risk of hospitalisation, need for oxygen therapy, or death. The Scientific Advisory Board (SAB) can propose the opening of a new arm at any time, or the withdrawal of an ongoing arm if new external data suggest the drug is unsafe or insufficiently active against SARS-CoV-2. At the end of the pilot phase and at pre-established interim sample sizes during the efficacy phase, the Data Safety Monitoring Board (DSMB) conducts interim analyses and advises the SAB on continuation of the arm analyzed. The DSMB can also advise the SAB to withdraw an arm for safety or futility reasons at any time between analyses. Fig. SA1-3 in Appendix S1 shows all the experimental drugs included in the trial to date, as well as the date and reasons for withdrawing those that were halted prematurely.

The ciclesonide arm was opened on 29 December 2020. On 9 June 2021, the DSMB decided to run an interim analysis to ascertain whether the magnitude of the effect of ciclesonide observed in COVERAGE was within the range of that reported for budesonide in the PRINCIPLE trial [15]. The DSMB reviewed this interim analysis on 2 July 2021 and advised the SAB that continuing the ciclesonide arm would be futile. Based on this recommendation and blind to the results, the SAB decided to halt the ciclesonide arm on 22 July 2021. The arm was closed on 23 July 2021.

Reported here are the data from the participants randomized to the ciclesonide arm and those randomized to the control arm in the period when the ciclesonide arm was open.

Participants

Criteria for inclusion in the trial are as follows: (a) age ≥60 years regardless of the presence of other risk factors, or ≥50 years with at least one of the following risk factors: high blood pressure, body mass index ≥30 kg/m2, diabetes, ischemic heart disease, heart failure, history of stroke, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, stage ≥3 chronic kidney disease, solid or haematological malignancy diagnosed <5 years earlier, immunosuppressive therapy, or HIV infection with CD4 <200/mm3); (b) COVID-19 with first symptoms ≤7 days earlier; (c) positive SARS-CoV-2 nasopharyngeal RT-PCR or antigen test; (d) no criteria for hospitalization or acute oxygen therapy; and (e) written informed consent. Exclusion criteria are inability to understand or decide on participation; lack of health insurance; and conditions or treatment contraindicating the use of one trial drugs. For ciclesonide, the latter included chronic inhaled corticosteroid therapy, hypersensitivity to ciclesonide, history of incompletely treated pulmonary tuberculosis, pulmonary fungal infection, inability to use the inhalation chamber, and ongoing treatment with a potent CYP3A4 inhibitor.

Randomization and masking

Participants who met all the inclusion criteria and none of the exclusion criteria were randomly assigned 1:1 to one of the trial arms, using a secure online system. The randomization list had balanced blocks of fixed size and was stratified by study region. The allocated treatment was not masked from participants or investigators.

Treatment

Participants allocated to the control arm receive a 10-day treatment with a combination of vitamins and trace elements (Azinc Vitality, 2 pills per day). Participants allocated to the inhaled ciclesonide arm received a 10-day treatment with ALVESCO 160 μg, two puffs twice a day using an inhalation chamber (640 μg of ciclesonide per day).

Follow-up

Participants were randomised at home or in an outpatient facility on day (D)0 and then visited on D1, D3, D5, D7, D9, D14, and D28. D7 visits were face to face; other visits were by phone. Both patients and trial staff were allowed to request an additional visit at any time between scheduled visits for closer monitoring of clinical progress. Blood samples were collected from all participants at each trial centre on D0 to measure blood cell count, C-reactive protein, ferritin, lactate deshydrogenase, transaminases, and creatinine. At some centres, blood samples were also collected on D7 for the same tests, and a nasopharyngeal swab was collected on D7 for SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR testing.

Endpoints

The primary endpoint of the pilot phase is the occurrence of grade 3-4-5 adverse events. The primary endpoint of the efficacy phase is a combination of hospitalization and need for COVID-19-related oxygen therapy at home or death. Secondary endpoints are adverse events of any grade, maximal follow-up score on the WHO Ordinal Scale for Clinical Improvement, sustained alleviation of symptoms (body temperature ≤37.5°C and reports of all following symptoms as minor or none, with no subsequent relapse: asthenia, headache, cough, retrosternal discomfort/pain, thoracic oppression, thoracic pain, dyspnoea, nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, abdominal pain, anorexia, myalgia, or arthralgia), cure (participant report return to normal activity with no subsequent relapse), and RT-PCR and blood parameter evolution at D7.

Sample size

For the pilot phase, the sample size calculation is detailed in Appendix S2. For the efficacy phase, a sample size of 666 participants per arm was calculated as the number required to demonstrate that the proportion reaching the primary endpoint by D14 is at least 50% lower in one experimental arm than in the control arm, with the following assumptions: 7.5% reaching the primary endpoint in the control arm; 1-β = 95%; three interim analyses with 119, 235, and 403 participants in the arm; and one-sided type-I error 6.5%, 4.5%, 2.5%, and 2.5% at the first, second, and third interim analyses and final analysis.

Statistical analysis

For the pilot phase, the analysis is detailed in Appendix S2. For the efficacy phase, the primary analysis compares the proportion of participants reaching the primary endpoint by Day 14 in the two arms and is intention-to-treat (ITT) with a missing-equals-failure approach. Sensitivity analyses include an ITT analysis of observed data, excluding participants with missing data for the main outcome; a modified ITT (mITT) analysis of observed data, additionally excluding participants wrongly included; an ITT maximum bias analysis; and a per-protocol analysis of observed data. It was decided a priori that all secondary analyses would be descriptive and not subject to statistical testing.

The analyses were carried out using SAS version 9.4.

Ethics

The trial protocol was approved by a French Ethics Committee (CPPIDF1-2020-ND45). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Results

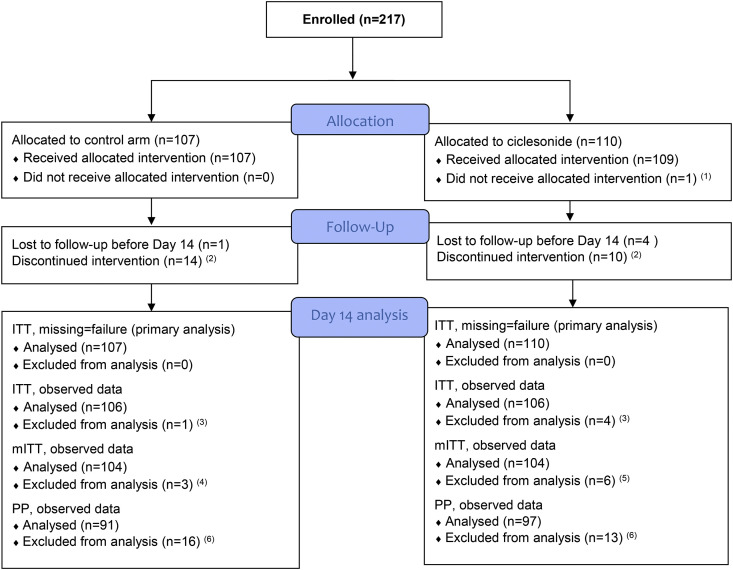

During the period when the ciclesonide arm was open, 217 participants were enrolled on the ciclesonide arm or the control arm (Fig. 1 ). Their characteristics at baseline are detailed in Table 1 . Fifty-one percent were women. The median age was 63 years (range 50–86 years), with 4 (1.8%) participants aged ≥80, 40 (18.4%) between 70 and 79, 107 (49.3%) between 60 and 69, and 66 (30.4%) between 50 and 59. One hundred fifty-seven (72.4%) participants had at least one comorbidity, including 4 (100%), 28 (70%), 60 (56%), and 65 (98%) of those aged ≥80, 70–79, 60–69, and 50–59, respectively. Overall, 171 (78.8%) participants had at least one symptom reported as moderate to severe, including 78 (36%) with moderate-to-severe lower respiratory tract symptoms and 41 (19%) with moderate-to-severe digestive symptoms (Table 1). The list of baseline symptoms by severity level and arm is given in Appendix S1 (Table SA1-4).

Fig. 1.

CONSORT flow diagram. This figure shows the flow of participants through Day 14. The number of participants included in the analyses covering the 28-day follow-up is shown in Table 2, Table 3. ITT, intention-to-treat; mITT, modified intention-to-treat; PP, per protocol. 1. Participant on chronic inhaled corticosteroid therapy (exclusion criteria). 2. Participants who have not been lost to follow-up before Day 9 and have not completed the 10-day treatment for reasons other than the occurrence of an adverse event. 3. Patients lost to follow-up were excluded from the ITT analysis. 4. Reasons: lost to follow-up, n = 1; major violation of eligibility criteria, n = 2 (untreated diabetes, n = 1; patient requiring oxygen therapy before randomisation, n = 1). 5. Reasons: lost to follow-up, n = 4; major violation of eligibility criteria, n = 2 (already on chronic inhaled corticosteroid therapy, n = 1; patient requiring oxygen therapy before randomisation, n = 1). 6. Patients who did not receive allocated intervention were lost to follow-up or did not complete the 10-day treatment for reasons other than the occurrence of an adverse event were excluded from PP analysis.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

| Control (n = 107) |

Ciclesonide (n = 110) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Age (y), median (IQR) | 63 (59; 70) | 62 (58; 67) |

| Sex (female), n (%) | 59 (55.1%) | 52 (47.3%) |

| Previous COVID-19 vaccine | ||

| No, n (%) | 93 (86.9%) | 94 (85.5%) |

| Yes, n (%) | 14 (13.1%) | 16 (14.5%) |

| One dose, n (%) | 13 | 15 |

| Two doses, n (%) | 1 | 1 |

| Time since last dose (d), median (IQR) | 12 (8; 24) | 16 (13; 21) |

| Time since first COVID-19 symptom (d), median (IQR) | 4 (3–6) | 4 (3–5) |

| At least one comorbidity, n (%) | 73 (68.2%) | 84 (76.4%) |

| High blood pressure | 38 (35.5%) | 51 (46.4%) |

| Body mass index ≥30 kg/m2a | 31 (29.0%) | 33 (30.0%) |

| Diabetes | 16 (15.0%) | 17 (15.5%) |

| Stroke | 9 (8.4%) | 10 (9.1%) |

| Ischemic heart disease | 7 (6.5%) | 4 (3.6%) |

| Solid tumour or haematological malignancy <5 y | 6 (5.6%) | 7 (6.4%) |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 4 (3.7%) | 3 (2.7%) |

| Cardiac insufficiency | 3 (2.8%) | 2 (1.8%) |

| HIV infection | 1 (0.9%) | 0 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2), median (IQR) | 27 (24; 31) | 27 (24; 32) |

| SpO2 under room air, median (IQR) | 98 (97; 99) | 98 (97; 98) |

| Body temperature (°C), median (IQR) | 37.0 (36.5; 37.3) | 36.8 (36.4; 37.3) |

| WHO Ordinal Scale for Clinical Improvement, n (%) | ||

| 1 - No limitation of activities | 85 (79.4%) | 82 (74.5%) |

| 2 - Limitation of activities | 22 (20.6%) | 28 (25.5%) |

| Symptoms, moderate or severe, n (%)b | ||

| General symptoms | 81 (75.7%) | 80 (72.7%) |

| Upper respiratory tract | 39 (36.4%) | 37 (33.6%) |

| Lower respiratory tract | 39 (36.4%) | 39 (35.5%) |

| Digestive | 16 (15.0%) | 25 (22.7%) |

| Anosmia or dysgeusia | 18 (16.8%) | 18 (16.4%) |

| Biological characteristics, median (IQR) | ||

| Blood cell count | ||

| Total leucocytes, × 106/L | 4.7 (4.0; 5.6) | 4.6 (3.8; 5.6) |

| Lymphocytes, × 106/L | 1.34 (1.02; 1.78) | 1.35 (1.05; 1.74) |

| Neutrophils, × 106/L | 2.67 (2.04; 3.40) | 2.69 (1.86; 3.39) |

| Haemoglobin, g/dL | 14.3 (13.3; 15.3) | 14.4 (13.8; 15.5) |

| Platelet count, × 106/L | 190 (166; 229) | 195 (165; 229) |

| C-reactive protein (CRP), mg/L | 6.9 (2.2; 16.1) | 9.7 (3.5; 18.8) |

| Ferritinemia, μg/L | 263 (161; 444) | 266 (158; 509) |

| Albuminemia, g/L | 40.8 (38.0; 43.0) | 40.8 (38.0; 43.7) |

| Creatininemia, μmol/L | 71 (64; 84) | 74 (64; 85) |

| Lactate deshydrogenase, IU/L | 214 (192; 246) | 211 (193; 239) |

| Aspartate amino transferase, IU/L | 31 (23; 37) | 32 (25; 44) |

| Alanine amino transferase, IU/L | 31 (22; 44) | 35 (25; 55) |

IQR, interquartile range; IU, international unit; SD, standard deviation.

Including eight participants with a BMI ≥40 kg/m2 (four control, four ciclesonide).

-

•General symptoms: asthenia, anorexia, myalgia/arthralgia, headache

-

•Upper respiratory tract: rhinorrhoea/nasal obstruction/sneezing, sore throat (includes pruritus of the throat or throat irritation)

-

•Lower respiratory tract: cough, chest pain, chest tightness, retro sternal discomfort or pain, dyspnoea

-

•Digestive: nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, abdominal pai

-

•Anosmia or dysgeusia

- The details for each grade per symptom are shown in Appendix S1 (Section SA1-4).

During follow-up, the 217 participants had 1653 protocol visits (control 815, ciclesonide 838), 18 had 19 additional unscheduled visits (control 11, ciclesonide 8), 4 were prescribed oxygen therapy at home with no subsequent hospitalisation (control 2/107 [1.9%], ciclesonide 2/110 [1.8%]), 24 were hospitalized (control 10/107 [9.3%], ciclesonide 14/110 [12.7%]), and 2 died (control 2/107 [1.9%], ciclesonide 0). The median time between enrolment and admission to hospital was 6 days (IQR 4–9; control 5 [[4], [5], [6], [7]], ciclesonide 6 [[5], [6], [7], [8], [9]]). The median length of hospital stay was 6.5 days (IQR 4.5–14.5; control 7.0 [5.0–14.0], ciclesonide 6.5 [3.0–15.0]).

Table 2 shows the proportion of participants who reached the primary efficacy endpoint or any of its components in each arm and the results of the primary and sensitivity analyses. In intent-to-treat analysis of observed data, 26 participants reached the composite primary endpoint by Day 14, including 12 of 106 (11.3%, 95% CI: 6.0%–18.9%) in the control arm and 14 of 106 (13.2%; 95% CI: 7.4%–21.2%) in the ciclesonide arm. The analysis package of the primary endpoint provided robust arguments to conclude that continuing the ciclesonide arm would be futile.

Table 2.

Oxygen therapy at home, hospitalization, or death, according to randomization arm

| Control |

Ciclesonide |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | n | Percentage | (95% CI) | N | n | Percentage | (95% CI) | ||

| Oxygen need, hospitalization, or death by Day 14 | |||||||||

| Composite outcome | |||||||||

| Intention-to-treat, missing = failurea | 107 | 13 | 12.1% | (6.6–19.9) | 110 | 18 | 16.4% | (10.0–24.6) | |

| Intention-to-treat, observed datab | 106 | 12 | 11.3% | (6.0–18.9) | 106 | 14 | 13.2% | (7.4–21.2) | |

| Modified intention-to-treat, observed datab | 104 | 11 | 10.6% | (5.4–18.1) | 104 | 13 | 12.5% | (6.8–20.4) | |

| Intention-to-treat, maximum bias in favour of controlb | 107 | 12 | 11.2% | (5.9–18.8) | 110 | 18 | 16.4% | (10.0–24.6) | |

| Intention-to-treat, maximum bias in favour of ciclesonideb | 107 | 13 | 12.1% | (6.6–19.9) | 110 | 14 | 12.7% | (7.1 –20.4) | |

| Per protocol analysisb | 91 | 9 | 9.9% | (4.6–17.9) | 97 | 11 | 11.3% | (5.8–19.4) | |

| Events included in the composite outcome | |||||||||

| Deathc | 1 | 0 | |||||||

| Oxygen therapy at home, no hospitalization | 2 | 2 | |||||||

| Hospitalization | 9 | 12 | |||||||

| Oxygen need, hospitalization, or death by Day 28 | |||||||||

| Composite outcome | |||||||||

| Intention-to-treat, observed datab | 100 | 13 | 13.0% | (7.1 to 21.2) | 104 | 16 | 15.4% | (9.1–23.8) | |

| Modified intention-to-treat, observed datab | 98 | 12 | 12.2% | (6.5 to 20.4) | 102 | 15 | 14.7% | (8.5–23.1) | |

| Events included in the composite outcome | |||||||||

| Deathc | 2 | 0 | |||||||

| Oxygen therapy at home, no hospitalization | 2 | 2 | |||||||

| Hospitalization | 10 | 14 | |||||||

Primary analysis, as per the trial protocol.

Sensitivity analyses, as per the trial protocol.

One participant died at home at Day 5 from undocumented cause and had no previous severe claims. One participant died at hospital at Day 16 from COVID19-related acute respiratory distress syndrome.

Table 3 shows the description of the secondary outcomes.

Table 3.

Secondary outcomes, according to randomization arm

| Control |

Ciclesonide |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | n | % | N | n | % | |

| Positive SARS-CoV-2 PCR at Day 7a | 54 | 41 | 75.9% | 53 | 43 | 81.1% |

| AEs over the entire follow-upb | ||||||

| At least one AE of any grade | 96 | 30 | 31.3% | 105 | 39 | 37.1% |

| At least one grade 1 AE | 91 | 15 | 16.5% | 104 | 22 | 21.2% |

| At least one grade 2 AE | 93 | 11 | 11.8% | 104 | 13 | 12.5% |

| At least one grade 3 AE | 94 | 9 | 9.6% | 103 | 15 | 14.6% |

| At least one grade 4 or 5 AE | 91 | 2 | 2.2% | 102 | 1 | 1.0% |

| Highest WHO OSCI grade during the entire follow-up | ||||||

| 1 - Ambulatory, no limitation of activities | 107 | 20 | 18.7% | 108 | 20 | 18.5% |

| 2 - Ambulatory, limitation of activities | 107 | 74 | 69.2% | 108 | 72 | 66.7% |

| 3 - Hospitalization, no oxygen therapy | 107 | 1 | 0.9% | 108 | 2 | 1.9% |

| 4 - Hospitalization, oxygen by mask or nasal prongsc | 107 | 10 | 9.3% | 108 | 10 | 9.3% |

| 5 - Hospitalization, noninvasive ventilation, or high-flow oxygenrowhead | 107 | 0 | 108 | 3 | 2.8% | |

| 6 - Hospitalization, intubation, and mechanical ventilation | 107 | 0 | 108 | 1 | 0.9% | |

| 7 - Hospitalization, ventilation, plus additional organ support | 107 | 0 | 108 | 0 | ||

| 8 - Death | 107 | 2 | 1.9% | 108 | 0 | |

| Sustained alleviation of symptomsd | ||||||

| By Day 7 | 104 | 31 | 29.8% | 107 | 37 | 34.6% |

| By Day 14 | 100 | 57 | 57.0% | 105 | 57 | 54.3% |

| Sustained self-reported curee | ||||||

| By Day 7 | 104 | 13 | 12.5% | 107 | 13 | 12.1% |

| By Day 14 |

100 |

51 |

51.0% |

106 |

47 |

44.3% |

| N |

Mean |

SD |

N |

Mean |

SD |

|

| Time to sustained alleviation of symptoms (d)d | 78 | 12.1 | (9.8) | 79 | 13.3 | (11.0) |

| Time to sustained self-reported cure (d)e | 81 | 16.9 | (9.0) | 87 | 18.5 | (10.2) |

| Ferritinemia (μg/L)a | ||||||

| Measure at Day 7 | 59 | 384 | (347) | 59 | 460 | (430) |

| Evolution D0 to Day 7 | 58 | +71.7 | (282) | 59 | +92.7 | (326) |

| Plasma C-reactive protein at Day 7 (mg/L)a | ||||||

| Measure at Day 7 | 61 | 15.9 | (22.5) | 59 | 23.9 | (32.7) |

| Evolution D0 to Day 7 | 59 | +6.1 | (26.5) | 59 | +10.2 | (36.1) |

| Plasma lactate dehydrogenase at Day 7 (IU/mL)a | ||||||

| Measure at Day 7 | 58 | 241 | (60) | 57 | 246 | (63) |

| Evolution D0 to Day 7 | 57 | +19 | (53) | 57 | +33 | (55) |

All figures showed in this Table are from observed data. OSCI, Ordinal Scale for Clinical Improvement; SD, standard deviation.

Nasopharyngeal and blood samplings were performed at Day 7 in a limited number of centres (Bordeaux, Nancy, Dijon, Montpellier). Blood samplings were performed at Day 7 in a limited number of centres (Bordeaux, Nancy, Dijon, Montpellier, Toulouse).

Severity grade according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE). Eleven participants had 13 grade ≥ 3 adverse events in the control group: worsening of COVID-19–related pulmonary signs or symptoms (n = 9), intestinal ischaemia (n = 1), bacterial pneumonia (n = 1), appendicitis (n = 1), and death of unknown cause (n = 1). Sixteen participants had 26 grade ≥ 3 adverse events in the ciclesonide group: worsening of COVID-19–related pulmonary signs or symptoms (n = 15), pulmonary embolism (n = 2), myocardial infarction (n = 1), bacterial pneumonia (n = 1), angioedema (n = 1), and worsening of general symptoms (n = 6).

Includes the four patients who received oxygen therapy at home and were never hospitalized.

-

•Sustained alleviation by Day 7: control 61/104 (58.7%), ciclesonide 65/107 (60.7%)

-

•Sustained alleviation by Day 14: control 77/100 (77.0%), ciclesonide 81/105 (77.1%)

Cure: Participant reports return to normal activity with no subsequent relapse.

Discussion

Our data should be considered alongside others from randomised trials of inhaled corticosteroids in COVID-19 outpatients. In a phase 2 trial conducted by Song et al. [16], 61 adult patients of any age with COVID-19 were randomized to inhaled ciclesonide or standard care (SC). The number (%) of participants reaching the primary endpoint (SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR negativation by Day 14) was 10 (32.3%) in the ciclesonide group and 1 (5.0%) in the SC group (p = 0.021) [16]. In the phase 2 STOIC trial, 146 adults of any age were randomized to inhaled ciclesonide or SC. The number (%) of participants reaching the primary endpoint (COVID-19-related emergency department assessment or hospitalization) was 2 (3%) in the ciclesonide group and 11 (15%) in the SC group (p = 0.009) [17]. In a phase 2 trial conducted by Clemency et al. [18], 413 adults of any age were randomized to inhaled ciclesonide or a placebo. The median time to alleviation of all COVID-19–related symptoms was 19.0 days (95% CI: 14.0–21.0) in the ciclesonide arm and 19.0 days (95% CI: 16.0–23.0) in the placebo arm. The number (percentage) of participants with hospital admission by day 30 was three (1.5%) in the ciclesonide arm and seven (3.4%) in the placebo arm (OR 0.45, 95% CI: 0.11–1.84, p = 0.26) [18]. The phase 2/3 CONTAIN trial compared inhaled plus intranasal ciclesonide with a placebo in COVID-19 patients of any age with cough, dyspnoea, or fever. The trial was stopped early after enrolling 203 participants. The percentage of patients reaching the primary endpoint (resolution of symptoms by day 7) was 40% in the ciclesonide group and 35% in the placebo group (adjusted risk difference 5.5% (95% CI: 7.8%–18.8%). The number (percentage) of participants with hospital admission by Day 14 was six (6%) in the ciclesonide arm and three (3%) in the placebo arm (adjusted risk difference 2.3% (95% CI: 3.0%–7.6%) [19]. Finally, in the phase 3 PRINCIPLE trial, 1856 adults aged over 50 years with comorbidities, or over 65 with or without comorbidities, were randomized to inhaled budesonide or SC. The rate of hospitalization or death was 6.8% in the budesonide group and 8.8% in the SC group. The time to recovery was 11.8 days in the budesonide group and 14.7 days in the SC group. In Bayesian piecewise exponential analysis, the former was considered nonsignificant and the latter significant [15].

PRINCIPLE and COVERAGE have similar target populations and a similar hard primary endpoint (including hospitalization and death). The difference between arms for this endpoint was nonsignificant in PRINCIPLE and led to the conclusion of futility in COVERAGE. Although the former used budesonide and the latter ciclesonide, both trials suggest that it will be difficult to prove that inhaled corticosteroid reduces the risk of clinical worsening in trials designed to include hundreds of participants, also suggesting that the efficacy of inhaled corticosteroid in reducing this risk, if any, would be small.

There were several limitations to our trial. First, it was open label. It is therefore possible that some hospitalization decisions were influenced by knowing what treatment was being provided. Second, daily symptoms were self-reported on fixed occasions. Time to clinical improvement and cure are therefore to be interpreted with caution because of the risk of interval censoring. Third, we did not record information of the number of people approached for the study and the reasons for exclusion. Finally, morbidity data collected during the study do not allow for conclusions about the safety profile of inhaled ciclesonide in this population.

In conclusion, it is now considered acceptable to include repurposed drugs with good safety profiles in efficacy trials on the basis of in vitro or ex vivo arguments alone, on two conditions: first, that animal research is conducted in parallel to provide the preclinical arguments that usually precede a clinical trial [9,20]; second, that interim analyses allow for early withdrawal of the drug if there are convincing arguments that the trial will never reach a conclusion on efficacy. This reasoning led to discontinuation of our ciclesonide arm. Our findings are consistent with the European Medicines Agency's COVID-19 taskforce (COVID-ETF) statement that there is currently insufficient evidence that inhaled corticosteroids are beneficial for people with COVID-19 [21]. The COVERAGE trial is currently continuing with an inhaled interferon-β1b arm.

Transparency declaration

The anonymized individual data and the data dictionary of the study will be made available to other researchers by the coordinating investigator, Professor Denis Malvy (denis.malvy@chu-bordeaux.fr), after approval of a methodologically sound proposal and the signature of a data access agreement. All authors declare no conflict of interest.

The trial protocol was registered in the European database EudraCT (2020-001435-27) and on clinicaltrials.gov (NCT04356495). The trial was supported by grants from the French Ministry of Health (PHRC-N COVID, 2020, COVID-19-20-0100), the French National Research Agency (ANR: ANR-20-COVI-0040-01), the University of Bordeaux, and Inserm/REACTing. CHU de Bordeaux is the sponsor of the study. The funders of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report.

Author contributions

AD and EL contributed equally to this work. LW, XA, and DM contributed equally to this work. AD, EL, RO, RS, DN, TP, RT, J-PJ, LR, LW, SB, RL, XA, and DM designed the study. AD, RO, XA, DM, JC, LP, CB, JD, AM, BL, J-MN, DN, TP, and OS-L enrolled and followed the patients and recorded clinical data. SD, M-EL, and MM supervised the virological and pharmacological aspects. CW, CR, AG, SK, VJ, EL, RS, RT, LR, and LW monitored the study. XdL chaired the Scientific Advisory Board. AD, XA, EL and RS performed the analysis. AD, EL, XA, and DM drafted the first version of the manuscript. All authors revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content and approved the final version before submission.

Acknowledgement

We thank all the persons who participated in the trial. We thank the city of Bordeaux for logistic support.

Editor: A. Huttner

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmi.2022.02.031.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Mesas A.E., Cavero-Redondo I., Álvarez-Bueno C., Sarriá Cabrera M.A., Maffei de Andrade S., Sequí-Dominguez I., et al. Predictors of in-hospital COVID-19 mortality: a comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis exploring differences by age, sex and health conditions. PloS One. 2020;15 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0241742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reilev M., Kristensen K.B., Pottegård A., Lund L.C., Hallas J., Ernst M.T., et al. Characteristics and predictors of hospitalization and death in the first 11 122 cases with a positive RT-PCR test for SARS-CoV-2 in Denmark: a nationwide cohort. Int J Epidemiol. 2020;49:1468–1481. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyaa140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gude-Sampedro F., Fernández-Merino C., Ferreiro L., Lado-Baleato Ó, Espasandín-Domínguez J., Hervada X., et al. Development and validation of a prognostic model based on comorbidities to predict COVID-19 severity: a population-based study. Int J Epidemiol. 2021;50:64–74. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyaa209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Indari O., Jakhmola S., Manivannan E., Jha H.C. An update on antiviral therapy against SARS-CoV-2: how far have we come? Front Pharmacol. 2021;12:632677. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2021.632677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.James N.D., Sydes M.R., Clarke N.W., Mason M.D., Dearnaley D.P., Anderson J., et al. Systemic therapy for advancing or metastatic prostate cancer (STAMPEDE): a multi-arm, multistage randomized controlled trial. BJU Int. 2009;103:464–469. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.08034.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Noor N.M., Pett S.L., Esmail H., Crook A.M., Vale C.L., Sydes M.R., et al. Adaptive platform trials using multi-arm, multi-stage protocols: getting fast answers in pandemic settings. F1000Research. 2020;9:1109. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.26253.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dillman A., Zoratti M.J., Park J.J.H., Hsu G., Dron L., Smith G., et al. The landscape of emerging randomized clinical trial evidence for COVID-19 disease stages: a systematic review of global trial registries. Infect Drug Resist. 2020;13:4577–4587. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S288399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tzou P.L., Tao K., Nouhin J., Rhee S.-Y., Hu B.D., Pai S., et al. Coronavirus Antiviral Research Database (CoV-RDB): an online database designed to facilitate comparisons between candidate anti-coronavirus compounds. Viruses. 2020;12:1006. doi: 10.3390/v12091006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Duvignaud A., Anglaret X. Research on COVID-19 therapy: putting the cart alongside the horse. EBioMedicine. 2021;67:103342. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2021.103342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bateman E., Karpel J., Casale T., Wenzel S., Banerji D. Ciclesonide reduces the need for oral steroid use in adult patients with severe, persistent asthma. Chest. 2006;129:1176–1187. doi: 10.1378/chest.129.5.1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ukena D., Biberger C., Steinijans V., von Behren V., Malek R., Weber H.H., et al. Ciclesonide is more effective than budesonide in the treatment of persistent asthma. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2007;20:562–570. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2006.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Matsuyama S., Kawase M., Nao N., Shirato K., Ujike M., Kamitani W., et al. The inhaled steroid ciclesonide blocks SARS-CoV-2 RNA replication by targeting the viral replication-transcription complex in cultured cells. J Virol. 2020;95:e01648. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01648-20. 20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ko M., Chang S.Y., Byun S.Y., Ianevski A., Choi I., Pham Hung d’Alexandry d’Orengiani A.-L., et al. Screening of FDA-approved drugs using a MERS-CoV clinical isolate from South Korea identifies potential therapeutic options for COVID-19. Viruses. 2021;13:651. doi: 10.3390/v13040651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jeon S., Ko M., Lee J., Choi I., Byun S.Y., Park S., et al. Identification of antiviral drug candidates against SARS-CoV-2 from FDA-approved drugs. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2020;64:e00819–e00820. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00819-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yu L.-M., Bafadhel M., Dorward J., Hayward G., Saville B.R., Gbinigie O., et al. Inhaled budesonide for COVID-19 in people at high risk of complications in the community in the UK (PRINCIPLE): a randomised, controlled, open-label, adaptive platform trial. The Lancet. 2021;398:843–855. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01744-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Song J.-Y., Yoon J.-G., Seo Y.-B., Lee J., Eom J.-S., Lee J.-S., et al. Ciclesonide inhaler treatment for mild-to-moderate COVID-19: a randomized, open-label, phase 2 trial. J Clin Med. 2021;10:3545. doi: 10.3390/jcm10163545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ramakrishnan S., Nicolau D.V., Langford B., Mahdi M., Jeffers H., Mwasuku C., et al. Inhaled budesonide in the treatment of early COVID-19 (STOIC): a phase 2, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2021;9:763–772. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(21)00160-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Clemency B.M., Varughese R., Gonzalez-Rojas Y., Morse C.G., Phipatanakul W., Koster D.J., et al. Efficacy of inhaled ciclesonide for outpatient treatment of adolescents and adults with symptomatic COVID-19: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2022;182:42–49. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2021.6759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ezer N., Belga S., Daneman N., Chan A., Smith B.M., Daniels S.-A., et al. Inhaled and intranasal ciclesonide for the treatment of covid-19 in adult outpatients: CONTAIN phase II randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2021;375 doi: 10.1136/bmj-2021-068060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liesenborghs L., Spriet I., Jochmans D., Belmans A., Gyselinck I., Teuwen L.-A., et al. Itraconazole for COVID-19: preclinical studies and a proof-of-concept randomized clinical trial. EBioMedicine. 2021;66:103288. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2021.103288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.EMA’s COVID-19 Taskforce . Eur Med Agency; 2021. Insufficient data on use of inhaled corticosteroids to treat COVID-19.https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/news/insufficient-data-use-inhaled-corticosteroids-treat-covid-19 (Accessed December 31, 2021) [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.