Abstract

Fluorescence microscopy is a broadly used technique within a variety of different fields, including life sciences and medical research, and its quantitative aspects are becoming emphasized. The challenge now lies in improving the accuracy and precision of the measurements obtained from fluorescence microscopy. Improving these will facilitate the comparison of results between different instruments/institutions and therefore ensure the reproducibility of results. In this review, recent standardization procedures, including the benchmarking of the instrument performance and the standardization of the image itself, as well as the reference materials for calibration are summarized, and an overview of the advances in fluorescence microscopy standardization and the current limitations are presented. A procedure for the comparison of the image data obtained using different instruments, by different analysts and/or at different times, should be developed to improve the standardization of this data. The standardization of image data would lead to the development of new applications of fluorescence microscopy not only in academic research but also in regulatory science.

Keywords: Fluorescence microscopy, Standardization, Reference materials, Microscope benchmarking

Introduction

Fluorescence microscopy is employed globally as a general method to study the morphology of cells and tissues in the life sciences and medical research fields. The quantitative aspects of fluorescence microscopy are becoming emphasized, in line with the development of systems biology (Megason and Fraser 2007), high-content analysis, imaging-based drug screening (Leonard et al. 2015), and digital pathology (Bera et al. 2019).

The challenge now lies in improving the accuracy and precision of the measurements obtained using fluorescence microscopy. Improving this will facilitate the comparison of results between different instruments/institutions and therefore ensure the reproducibility of the results (Llopis et al. 2021). For example, if imaging data is obtained using two different instruments with different detector sensitivities, the resulting intensity values will be difficult to compare. Many specific measurement methods and analysis algorithms based on fluorescence microscopy have been proposed, but their procedures for data treatment and assessment are not standardized. Thus, the comparability of the values is not sufficiently assured. This demonstrates the need for a simple and user-friendly standardization procedure.

Recently, new calibration procedures have been proposed (Deagle et al. 2017; Llopis et al. 2021) and new materials for fluorescence microscope calibration, such as fluorescence-patterned glass slides (Royon and Converset 2017) and DNA-origami-based probes (Steinhauer et al. 2009), have been developed and are available from several ambitious companies. In addition, the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) developed the international standard for confocal microscopy measurements in 2019 (ISO21073: 2019). This standard provides guidelines to ensure reproducible fluorescence confocal microscopy. A community-driven initiative, the Quality Assessment and Reproducibility for Instruments & Images in Light Microscopy (QUAREP-LiMi), was established to improve reproducibility of light microscopy image data (Boehm et al. 2021). The initiative includes several working groups to discuss the topics described in this review, such as illumination power, detection system performance, resolution, image quality, and standards.

Although the general concept of calibration is undergoing development, the standardization needed to allow comparability of fluorescence intensity is still difficult to achieve. The reason for this is the lack of reference materials that have determined absolute fluorescence intensity. However, the calibration of relative fluorescence using reference materials with undetermined absolute values of fluorescence emission is still possible, although only briefly for comparability, as long as the reference material is sufficiently stable.

Super-resolution microscopy is generally based on fluorescence microscopy, and the instruments include relatively complex mechanics and/or specific algorithms such as deconvolution. If the measurement conditions, including the optical setup and setting parameters, are inappropriate, the resulting image quality in some cases will be significantly deteriorated. To ensure appropriate measurement conditions, the benchmark of the system performance in each institute and each system is much more important for super-resolution microscopy than for conventional microscopy.

In this review, recently developed standardization procedures, including benchmarking the instrument performance, standardization of the image itself, and reference materials for calibration, are summarized. Moreover, an overview of the advances in fluorescence microscopy standardization and current limitations are also presented.

Benchmarking the instruments

Fluorescence microscope components

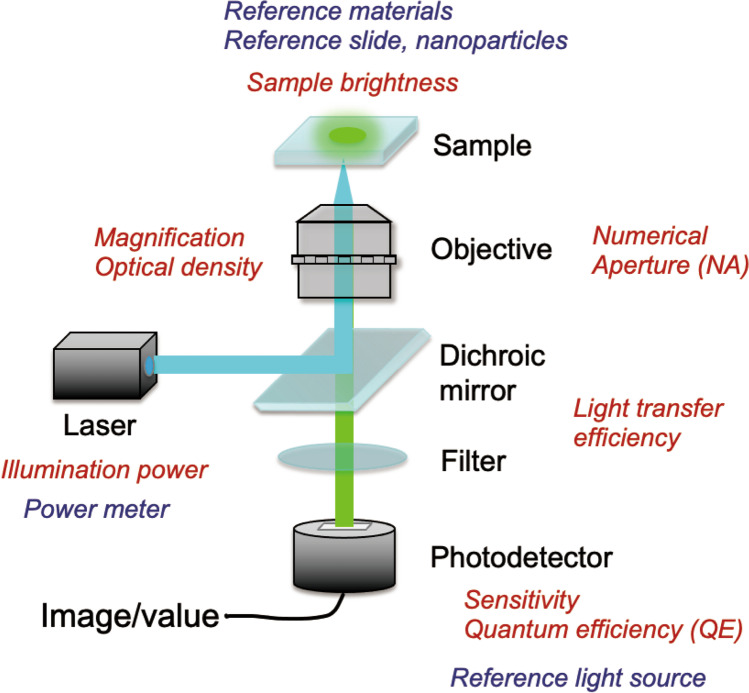

Fluorescence microscopy generally includes light sources (lasers), dichroic mirrors, objective lenses, filters, and photodetectors. Every component is responsible for image quality and signal quantity, and the performance of the entire system is a convolution of the effect of each component (Fig. 1). The coverglass and immersion fluid of the objective lens are also included as optical parts of the microscope; coverglass thickness, correction ring adjustment, and type of immersion fluid should be selected correctly by users. Difficulty arises because the component performance changes depending on the wavelength of light used (Deagle et al. 2017). Therefore, the performance of a microscope is affected not only by the system setup but also by the properties of the sample. Procedures for the adjustment and care of the microscope and its components are critical for robust and accurate quantitative microscopy. For example, the alignment and stability of light source, the position of the optical elements such as the pinhole, and the extent of oil and dust accumulated on the surface of the objective lens and other optical components can affect the image quality (Deagle et al. 2017).

Fig. 1.

Schematic image of microscope components responsible for the resulting image data. The parameters to be evaluated/calibrated and reference materials for the evaluation/calibration are shown in red and blue, respectively

Parameters to be calibrated

Illumination power

Illumination power is a critical parameter for fluorescence imaging. The power is related to the fluorescence intensity, signal-to-noise ratio (S/N), photophysical reaction, and photobleaching. When the illumination power is too high, photobleaching can occur and detection signal linearity can collapse due to the detector saturation (Waters 2009, Jost and Waters 2019). The illumination power for fluorophore excitation can be measured by a power meter, which is a sensor calibrated to international system of units (SI), watt (W). The challenge is that it is difficult to determine the actual flux density of illumination at the focal position because the optical density depends on the illumination area (for wide-field microscopy) and focal radius (for confocal microscopy). These are determined by the optical setup, i.e., the magnification and numerical aperture (NA) of the objective lens used. The protocol used to estimate the power density of the excitation light in the objective plane is described by Grünwald et al. (2008). Fluorescence intensity and photobleaching are both related to the excitation efficiency of the fluorescent molecule at the wavelength irradiated, and the selection of the illumination wavelength is also important for reproducibility and intersystem comparison.

Spatial resolution

The spatial resolution of a microscopy image is related to the pixel size resolution of the detector and the optical resolution (resolving power) of the microscope optics/objective lens. In situations where the number of pixels in the digital image is superior to the optical resolution, the spatial resolution of the resulting digital image is limited only by optical resolution. Optical resolution is determined by the performance of the microscope optics and the diffraction limit. Resolving power can be monitored on patterned glass slides. The performance of a confocal microscope system is partly dependent on point-spread function (PSF), which is determined by observing the sub-diffraction-sized fluorescent beads (generally 100 nm). Benchmarking the system performance and calibration of spatial resolution, including the determination of the size and shape of the PSF, are critical for super-resolution microscopy. In super-resolution microscopy, specific techniques included in the system such as stimulated emission depletion (STED) and the parameter settings of the instrument directly affect the resulting resolution of images. Additionally, fluorophore properties such as excitation/emission wavelength, which are used in the experiment, also affect the resolution in the case of STED imaging. Therefore, the benchmark of system performance on the setup of each measurement condition is very important. The PSF measurement procedure for STED microscopy using a newly developed test sample has been reported by van der Wee et al. (2021).

Sensitivity (detector and optics)

The sensitivity of the system (final output) is integral to the quantum efficiency (QE) of the photodetector and the light transfer efficiency of the optics from the sample to the photodetector. Detector sensitivity and linearity need to be evaluated to achieve accurate and reproducible data acquisition. There are two types of methods to monitor system sensitivity: calibration slide observation with determined excitation laser power and observation of external light source with calibrated light emission.

A benchmarking/calibration procedure for the absolute sensitivity of imaging systems for bioluminescence signals has been proposed by Enomoto et al. (2018), and its application to quantitative immunochemistry using protein microarray and bioluminescent protein is performed by Wang et al. (2020). The tool, a reference standard light-emitting diode (LED), for use as a calibrated external light source for calibration is commercially available. The procedure is also applicable to the calibration of photodetectors for fluorescence microscopy.

The signal to noise ratio (S/N) is an important specification in sensitivity of fluorescence microscopy, especially in the measurement of dim samples. To detect the movement of single molecules, image acquisition speed and interval are also important, in addition to QE and S/N. The background noise and dynamic range of the detector should be evaluated by reference measurements to improve the confidence of fluorescence intensity measurements.

Benchmarking procedures

The concepts and procedures for wide-field fluorescence microscopy benchmarks and calibration (Deagle et al. 2017; Halter et al. 2014; Model et al. 2009; Waters 2009) for quantitative measurements have been previously proposed, and some standardization documents have been published by organizations such as ASTM (American Society for Testing and Materials) international (ASTM F3294-18, 2018). Confocal microscopy is included in the target for benchmarking (Murray et al. 2007, Hng and Dormann 2013), and an international standard for confocal microscopy measurement has been developed by ISO (ISO21073: 2019). Table 1 summarizes the examples of benchmarking procedures and reference materials which could be applied for typical fluorescence microscopy techniques. These include evaluating and comparing general system performance including excitation light power, detector sensitivity, field uniformity, and spatial resolution. However, calibration of absolute fluorescence intensity in the microscopy image is still challenging because the procedure and reference materials are not yet available.

Table 1.

Examples of benchmarking procedures and reference materials for various microscopy techniques

| Light source/detector | Examples of benchmarking procedures | Examples of reference materials | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Widefield | Mercury lamp, LED/CCD, CMOS camera |

Halter et al. (2014) ASTM F3294 |

Fluorescent slides (e.g., Argolight slide, Schott colored glass) |

| Confocal | |||

| Point scan | Laser (spot)/PMT, APD |

Hng and Dormann (2013) Murray et al. (2007) |

Fluorescent beads (e.g., TetraSpeck microspheres) Fluorescent dye (e.g., SRM1932) |

| Spinning disk | Laser (multiple spots)/CCD, CMOS camera |

Jonkman et al. (2020) ISO21073:2019* |

|

| STED | Laser (spot), STED laser/PMT, APD | van der Wee et al. (2021) | DNA origami (e.g., nanoruler) |

| TIRF | Laser (evanescent wave)/CCD, CMOS camera |

Mattheyses et al. (2010) Oheim et al. (2019) |

Fluorescent beads |

| Light-sheet microscopy | Laser (sheet)/CCD, CMOS camera | Keller et al. (2008) | Fluorescent beads |

*Only for point-scan confocal microscopy

Fluorescence correlation spectroscopy (FCS), used for quantifying the molecular number and diffusion properties of samples (Elson and Magde 1974), can also be used for benchmarking confocal microscopy systems (Sasaki et al. 2019). The FCS measurement values are quite sensitive to the performance of the microscope components. In addition, this method requires a finely tuned microscope setup; for example, FCS was used to evaluate photodetector properties in a study by Yamashita et al. (2014). STED-FCS can be applied to evaluate the performance of super-resolution imaging microscopes with STED. STED microscopy is based on decreasing the confocal volume (i.e., FCS observation volume); FCS can monitor this decrease in the confocal volume (Eggeling et al. 2009). Instead of image observation and analysis of the PSF, STED-FCS can evaluate and compare the system performance quantitatively and statistically using only a simple reference measurement of the fluorescent dye solution.

Reference materials

Reference materials are important tools for calibrating measurement systems for fluorescence measurements, and are not just limited to fluorescence microscopy (DeRose et al. 2008; Resch-Genger et al. 2010). Appropriate reference materials, including fluorescent dyes, micro/nanospheres, and reference slides, are key for benchmarking the system and image standardization. A stage micrometer is traditionally used to calibrate the scale of microscopes. Fluorescent beads and nanoparticles are used for PSF measurements. For example, TetraSpeck microspheres stained with four different colors of fluorescent dyes are widely used to compensate for chromatic aberration of channels of different colors.

Recently, developed reference materials include fluorescent solution (Butzlaff et al. 2015) and patterned glass slides (Engel et al. 2006, Royon and Converset 2017), DNA origami-based nanorulers (Steinhauer et al. 2009), and laser-written fluorescence patterns (Corbett et al. 2018). Such reference materials are useful to determine the spatial resolution, field uniformity, and dynamic range determination and to verify day-to-day performance of the microscope system. However, the limitation of the current commercial reference materials is that it is difficult to standardize the absolute fluorescence intensity, because reference materials that have SI-traceable calibrated intensity are still undeveloped.

Furthermore, few primary, certified reference materials, such as fluorescein solution (SRM 1932) developed by the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) in the USA, with known concentrations (and sizes), exist that can be used for microscope calibration. It is, therefore, necessary for further development of reference materials with a wide range of fluorescence spectra, and a simple and universal method to determine the properties (concentration, brightness, size, etc.) of the candidate reference materials. So far, an FCS-based method for SI-traceable concentration determination for reference materials has been proposed by Sasaki et al. (2018).

Standardization of microscopy images

As of late, many programs and algorithms have been developed for automated image analysis. The validation of the results of segmentation of cellular components from cell images and quantification of the shape and texture is needed to improve the confidence of automatically derived data and its comparison (Dima et al. 2011). High-content imaging techniques have become widely used in pharmaceutical research (Leonard et al. 2015). A large amount of image data is derived from such analysis, and the data should be broadly shared as a dataset in a public database that can be used for big data analysis such as machine learning to accelerate drug development.

The signal intensity of the fluorescence image data is related to both the illumination power and sensitivity. A system with low detector sensitivity and high illumination (excitation) power and a system with high detector sensitivity and low illumination power may produce images of the same intensity, but the analysis of the data will have a different meaning. The setting with high detector sensitivity and low illumination power will produce better data that is less biased by the effects of photobleaching, saturation, photophysical reaction, and photodamage to living organisms (Jost and Waters 2019, Magidson and Khodjakov 2013). In addition, pixel size is a parameter to be considered, which is related to the signal intensity. When pixel size is reduced (i.e., in the case as super-resolution microscopy), detected photons at that pixel decrease. Conversely, binning of signal from several pixels can increase intensity value. Correcting raw image data for non-uniform field effects is also important for quantitative intensity measurements. The effect is a bias offset present in the intensity from each pixel of the detector due to non-uniform field illumination and/or different detection sensitivity at each pixel. Correction strategies are described in ASTM F3294 as an example. Furthermore, sample preparation methods, such as the strength of fluorescence staining, directly affect the image intensity and will be different between samples. In experiments on the expression of fluorescent proteins in living cells, it will be difficult to determine the concentration of the expressed fluorescent protein from the obtained images. Even if the images have the same fluorescence intensity, this could be a result of many different combinations of factors. For example, high-protein expression (large number of fluorescent molecules) with low excitation power (dim single-molecule brightness) or low-protein expression (small number of fluorescent molecules) with high excitation power (bright single-molecule-brightness) would produce fluorescence of the same intensity. Molecular interaction analysis using FRET (Förster resonance energy transfer) biosensors is widely employed to evaluate cellular responses, such as intracellular signal transduction (Nakamura et al. 2021), in living cells. In such cases, knowing the concentration of biosensor/target molecules in a specific region of living cells is challenging. FCS and number and brightness (N&B) analysis (Digman et al. 2008; Fukushima et al. 2018), one of the techniques of image correlation spectroscopy (Kolin and Wiseman 2007, Petersen et al. 1993), are promising techniques for evaluating molecular concentration of the fluorescent molecule within the images of living cells. N&B can determine the molecular number and single-molecule brightness in each pixel of time-lapse images. This technique will improve the standardization of the microscopy images, as it converts relative units of fluorescence images to absolute concentrations, which can be more easily compared between systems (Politi et al. 2018).

Medical use could be the next frontier of bioimaging; however, in the field of medicine, standardization is mandatory for safety and regulation. Digital pathology is a technique based on imaging of whole pathological slides and computational analysis, including artificial intelligence (AI), to support pathologists, and is quickly becoming realized. To make reliable decisions, the optical quality of the system and the color of the image are important; therefore, the standardization procedure of the optical quality is proposed by Shakeri et al. (2015), and the standardization procedure of the color variation of images caused by scanning process, viewer, display, and so on is proposed by Inoue and Yagi (2020). Standardization is useful not only for assisting pathologists’ decisions but also for improving the compatibility of AI algorithms developed by different manufacturers.

To maintain the traceability and reproducibility of image quality and quantity, providing information on the measurement conditions is essential to compare the image data and extract biological meaning from the comparison. Adjusting the images to the same intensity by changing the parameters such as illumination power is not sufficient for meaningful comparisons. The guidelines for reporting metadata in fluorescence microscopy have been developed by Llopis et al. (2021). The guideline describes parameters for reproducible and comparable microscopy experiments. The data format of the digital image to facilitate appropriate data sharing is an important issue in the bioimaging community, and a guideline for open image data format has been proposed by Swedlow et al. (2021), which makes the digital image data accessible and reusable.

Conclusion—future insight

A procedure for image data comparison between data obtained using different instruments, by different persons, and/or at different times should be developed to standardize image data. Preferably, a consensus of standardization procedures should be reached in the international academic/business community.

Further development of appropriate reference materials and standard protocols is necessary to achieve accurate quantitative fluorescence imaging. By establishing a concrete evidence for the validity of the measurement results and improving inter-laboratory comparability, the value of digital image data can be improved, which would promote better sharing of quantitative data in the academic/business community for big-data construction.

Standardization of image data could lead to new development in different applications of imaging techniques such as high-content imaging and quantitative biology. Standardization is also important not only in academic research but also in regulatory science, relating the fields of digital pathology, image-based medical diagnosis, and regenerative medicine.

Funding

This work was partly supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number 19K06590.

Declarations

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Bera K, Schalper KA, Rimm DL, Velcheti V, Madabhushi A. Artificial intelligence in digital pathology—new tools for diagnosis and precision oncology. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2019;16:703–715. doi: 10.1038/s41571-019-0252-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butzlaff M, Weigel A, Ponimaskin E, Zeug A (2015) eSIP: a novel solution-based sectioned image property approach for microscope calibration. PLoS One 10:e0134980. 10.1371/journal.pone.0134980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Boehm U, Nelson G, Brown CM, et al. QUAREP-LiMi: a community endeavor to advance quality assessment and reproducibility in light microscopy. Nat Methods. 2021 doi: 10.1038/s41592-021-01162-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbett A, Shaw M, Yacoot A, et al. Microscope calibration using laser written fluorescence. Opt Express. 2018;26:21887–21899. doi: 10.1364/OE.26.021887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deagle R, Wee T, Brown C. Reproducibility in light microscopy: maintenance, standards and SOPs. Int J Biochem & Cell Biol. 2017;89:120–124. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2017.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeRose PC, Wang L, Gaigalas AK, et al. (2008) Need for and metrological approaches towards standardization of fluorescence measurements from the view of national metrology institutes. In: Resch-Genger U. (eds) Standardization and Quality Assurance in Fluorescence Measurements I. Springer Series on Fluorescence, vol 5. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. 10.1007/4243_2008_049

- Digman MA, Dalal R, Horwitz AF, Gratton E. Mapping the number of molecules and brightness in the laser scanning microscope. Biophys J. 2008;94:2320–2332. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.114645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dima AA, Elliott JT, Filliben JJ, Halter M, et al. Comparison of segmentation algorithms for fluorescence microscopy images of cells. Cytometry A. 2011;79:545–559. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.21079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eggeling C, Ringemann C, Medda R, et al. Direct observation of the nanoscale dynamics of membrane lipids in a living cell. Nature. 2009;457:1159–U1121. doi: 10.1038/nature07596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elson EL, Magde D. Fluorescence correlation spectroscopy I conceptual basis and theory. Biopolymers. 1974;13:1–27. doi: 10.1002/bip.1974.360130102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel A, Ottermann C, Resch-Genger U et al. (2006) Glass based fluorescence reference materials used for optical and biophotonic applications. Biophotonics and New Therapy Frontiers 6191. 10.1117/12.663627

- Enomoto T, Kubota H, Mori K, et al. Absolute bioluminescence imaging at the single-cell level with a light signal at the Attowatt level. Biotechniques. 2018;64:270–274. doi: 10.2144/btn-2018-0043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukushima R, Yamamoto J, Ishikawa H, Kinjo M. Two-detector number and brightness analysis reveals spatio-temporal oligomerization of proteins in living cells. Methods. 2018;140:161–171. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2018.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grünwald D, Shenoy SM, Burke S, Singer RH. Calibrating excitation light fluxes for quantitative light microscopy in cell biology. Nat Protocols. 2008;3:1809–1814. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halter M, Bier E, DeRose P, et al. An automated protocol for performance benchmarking a widefield fluorescence microscope. Cytometry A. 2014;85A:978–985. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.22519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hng KI, Dormann D (2013) ConfocalCheck-a software tool for the automated monitoring of confocal microscope performance. PloS one 8:e79879. 10.1371/journal.pone.0079879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Inoue T, Yagi Y. (2020) Color standardization and optimization in whole slide imaging. Clin and diagn pathol, 4, 10.15761/cdp.1000139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Jonkman J, Brown CM, Wright GD, et al. Tutorial: guidance for quantitative confocal microscopy. Nat Protocols. 2020;15:1585–1611. doi: 10.1038/s41596-020-0313-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jost APT, Waters JC. Designing a rigorous microscopy experiment: validating methods and avoiding bias. J Cell Biol. 2019;218:1452–1466. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201812109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller PJ, Stelzer EH. Quantitative in vivo imaging of entire embryos with digital scanned laser light sheet fluorescence microscopy. Curr Opinion Neurobiol. 2008;18:624–632. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2009.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolin DL, Wiseman PW. Advances in image correlation spectroscopy: measuring number densities, aggregation states, and dynamics of fluorescently labeled macromolecules in cells. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2007;49:141–164. doi: 10.1007/s12013-007-9000-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard A, Cameron R, Speiser J, et al. Quantitative analysis of mitochondrial morphology and membrane potential in living cells using high-content imaging, machine learning, and morphological binning. BBA-Mol Cell Res. 2015;1853:348–360. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2014.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llopis P, Senft R, Ross-Elliott T, et al. Best practices and tools for reporting reproducible fluorescence microscopy methods. Nat Methods. 2021 doi: 10.1038/s41592-021-01156-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magidson V, Khodjakov A. Circumventing photodamage in live-cell microscopy. Methods in Cell Biol. 2013;114:545–560. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-407761-4.00023-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattheyses AL, Simon SM, Rappoport JZ. Imaging with total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy for the cell biologist. J Cell Sci. 2010;123:3621–3628. doi: 10.1242/jcs.056218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Megason S, Fraser S. Imaging in systems biology. Cell. 2007;130:784–795. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Model MA, Reese JL, Fraizer GC. Measurement of wheat germ agglutinin binding with a fluorescence microscope. Cytometry A. 2009;75:874–881. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.20787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray J, Appleton P, Swedlow J, Waters J. Evaluating performance in three-dimensional fluorescence microscopy. J Microscopy. 2007;228:390–405. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2818.2007.01861.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura A, Goto Y, Kondo Y, Aoki K. (2021) Shedding light on developmental ERK signaling with genetically encoded biosensors. Development, 148. 10.1242/dev.199767 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Oheim M, Salomon A, Weissman A, et al. Calibrating evanescent-wave penetration depths for biological TIRF microscopy. Biophys J. 2019;117:795–809. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2019.07.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen NO, Höddelius PL, Wiseman PW, Seger O, Magnusson KE. Quantitation of membrane receptor distributions by image correlation spectroscopy: concept and application. Biophys J. 1993;65:1135–1146. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(93)81173-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Politi AZ, Cai Y, Walther N, et al. Quantitative mapping of fluorescently tagged cellular proteins using FCS-calibrated four-dimensional imaging. Nat Protocols. 2018;13:1445–1464. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2018.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resch-Genger U, Hoffmann K, Würth C et al (2010) The toolbox of fluorescence standards: flexible calibration tools for the standardization of fluorescence-based measurements. In Sensors, and Command, Control, Communications, and Intelligence (C3I) Technologies for Homeland Security and Homeland Defense IX (Vol. 7666, p 76661J). International Society for Optics and Photonics. 10.1117/12.853133

- Royon A, Converset N. Quality Control of Fluorescence Imaging Systems: a new tool for performance assessment and monitoring. Optik & Photonik. 2017;12:22–25. doi: 10.1002/opph.201700005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki A, Halter M, Elliott JT. Fluorescence correlation methods for determining absolute numbers of molecules from microscopy images. Bioimages. 2019;27:13–22. doi: 10.11169/bioimages.27.13. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki A, Yamamoto J, Kinjo M, Noda N. Absolute quantification of RNA molecules using fluorescence correlation spectroscopy with certified reference materials. Anal Chem. 2018;90:10865–10871. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.8b02213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shakeri SM, Hulsken B, van Vliet LJ, Stallinga S. Optical quality assessment of whole slide imaging systems for digital pathology. Opt Express. 2015;23:1319–1336. doi: 10.1364/OE.23.001319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinhauer C, Jungmann R, Sobey T, Simmel F, Tinnefeld P. DNA origami as a nanoscopic ruler for super-resolution microscopy. Angewandte Chemie-International Edition. 2009;48:8870–8873. doi: 10.1002/anie.200903308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swedlow J, Kankaanpaa P, Sarkans U, et al. A global view of standards for open image data formats and repositories. Nat Methods. 2021 doi: 10.1038/s41592-021-01113-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Wee E, Fokkema J, Kennedy C, et al. 3D test sample for the calibration and quality control of stimulated emission depletion (STED) and confocal microscopes. Commun Biol. 2021;4:909. doi: 10.1038/s42003-021-02432-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang K, Wu C, Shimajiri S, et al. Quantitative immunohistochemistry using an antibody-fused bioluminescent protein. Biotechniques. 2020 doi: 10.2144/btn-2020-0006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters J. Accuracy and precision in quantitative fluorescence microscopy. J Cell Biol. 2009;185:1135–1148. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200903097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamashita T, Liu D, Miki S, et al. Fluorescence correlation spectroscopy with visible-wavelength superconducting nanowire single-photon detector. Opt Express. 2014;22:28783–28789. doi: 10.1364/OE.22.028783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]