Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the efficacy and safety of olokizumab (OKZ) in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis despite treatment with methotrexate (MTX).

Methods

In this 24-week multicentre, placebo-controlled, double-blind study, patients were randomised 1:1:1 to receive subcutaneously administered OKZ 64 mg once every 2 weeks, OKZ 64 mg once every 4 weeks, or placebo plus MTX. The primary efficacy endpoint was the proportion of patients achieving an American College of Rheumatology 20% (ACR20) response at week 12. The secondary efficacy endpoints included percentage of subjects achieving Disease Activity Score 28-joint count based on C reactive protein <3.2, Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index at week 12, ACR50 response and Clinical Disease Activity Index ≤2.8 at week 24. Safety and immunogenicity were assessed throughout the study.

Results

A total of 428 patients were randomised. ACR20 responses were more frequent with OKZ every 2 weeks (63.6%) and OKZ every 4 weeks (70.4%) than placebo (25.9%) (p<0.0001 for both comparisons). There were significant differences in all secondary efficacy endpoints between OKZ-treated arms and placebo. Treatment-emergent serious adverse events (TESAEs) were reported by more patients in the OKZ groups compared with placebo. Infections were the most common TESAEs. No subjects developed neutralising antidrug antibodies.

Conclusions

Treatment with OKZ was associated with significant improvement in signs, symptoms and physical function of rheumatoid arthritis without discernible differences between the two regimens. Safety was as expected for this class of agents. Low immunogenicity was observed.

Trial registration number NCT02760368.

Keywords: arthritis, rheumatoid, antirheumatic agents, cytokines

Key messages.

What is already known about this subject?

Olokizumab (OKZ) is a new humanised monoclonal antibody targeting interleukin 6 ligand.

Two placebo-controlled randomised phase II trials of OKZ in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) showed that it was significantly better than placebo across a range of doses; however, these studies were conducted in patients who had previously failed antitumour necrosis factor therapy and were of 12 weeks’ duration.

Long-term extension studies of these two controlled trials were conducted, but they were open-label and uncontrolled and all patients received the same dose of OKZ, 120 mg given every 2 weeks.

What does this study add?

This study is the first of three phase III randomised controlled trials of OKZ in RA.

In contrast to the phase II studies that were conducted in patients who had failed anti-TNF therapy, the current study was performed in patients who had an inadequate response to methotrexate.

This phase III study was of 6 months’ duration and tested two regimens of OKZ versus placebo and met all primary and ranked secondary efficacy endpoints.

This study provides important information on the efficacy, safety and quality of life effects of OKZ that were not previously known.

Key messages.

How might this impact on clinical practice or future developments?

The current phase III study of OKZ will be part of future registration of this agent in various countries.

OKZ was already approved for use in the Russian Federation.

The data provided in the study will be very important for clinicians who might want to use this agent in their practice once it is approved since it provides meaningful controlled data on the efficacy and safety of this agent in a population of patients with inadequate response to methotrexate.

Introduction

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic inflammatory disease that if left inadequately treated can lead to significant disability, morbidity and mortality.1–3 Current guidelines recommend a treat to target strategy in order to attain acceptable level of disease control and prevent long-term disability.1 3 A number of effective therapies with different modes of action are currently available for RA; however, many patients with active RA fail to achieve defined targets of therapy, namely low disease activity or remission.1 3 4

The proinflammatory cytokine interleukin 6 (IL-6) plays a significant role in the pathogenesis of RA and two anti-IL-6 receptor (IL-6R) antibodies have been shown to be relatively safe and effective and are approved for treatment of RA.5–9 Olokizumab (OKZ) is an anti-IL-6 monoclonal antibody that binds directly to IL-6 at a specific site and neutralises its activity through blocking hexamer formation of the extracellular signalling complex inhibiting transmembrane signalling.10 In early clinical studies it was shown that OKZ resulted in a rapid reduction in the level of IL-6 and C reactive protein (CRP) that lasted over an extended period of time due to OKZ’s long half-life of approximately 31 days.11

OKZ in doses ranging from 60 mg to 240 mg administered every 2 weeks or every 4 weeks was relatively safe and effective in reducing signs and symptoms of RA in two phase II randomised controlled trials in patients with RA who had failed to respond to antitumour necrosis factor (anti-TNF) therapy.12 13 Based on findings from these two studies, as well as information from earlier studies, two doses of OKZ, 64 mg every 2 weeks and 64 mg every 4 weeks, were selected for advancement to phase III.11 The lowest two doses tested in phase II were chosen to achieve efficacy while minimising potential adverse effects. Here we report the full results of the first completed phase III study of OKZ in patients with active RA despite treatment with methotrexate (MTX).

Methods

Study design

This phase III, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, multicentre trial was conducted at 42 hospitals in Russia, Belarus and Bulgaria from May 2016 to April 2019. Written informed consent was obtained from each patient.

After week 24, patients had the choice of either enrolling into an ongoing open-label study or entering the safety follow-up period.

Patient inclusion and exclusion criteria

Adults were eligible for inclusion if they had active RA (swollen joint count ≥6 (66-joint count), tender joint count ≥6 (68-joint count) and CRP >6 mg/L) classified by the American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism 2010 revised classification criteria14 for at least 12 weeks prior to screening and had an inadequate response to treatment with MTX for at least 12 weeks at a dose of 15–25 mg/week (or ≥10 mg/week if intolerant to higher doses). The dose and route of administration of MTX must have been stable for at least 6 weeks.

Exclusion criteria were other inflammatory or rheumatic diseases and Steinbrocker class IV functional capacity. Also excluded were those who had a prior exposure to IL-6 or IL-6R inhibitors, Janus kinase inhibitors, those treated with cell-depleting agents or those concurrently on disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) other than MTX. Prior use of biologic DMARDs was an exclusion criterion with the exception of subjects who discontinued anti-TNF therapy due to reasons other than lack of efficacy. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and glucocorticoids in doses less than or equal to 10 mg/day prednisone or equivalent were allowed if their doses were stable during the 2 weeks prior to study enrolment. Patients with a history of malignancies within the last 5 years (successfully treated carcinoma of the cervix in situ, basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma of the skin were allowed if beyond 1 year prior to screening), recurrent infections, primary or secondary immunodeficiency, hepatitis B or C, active tuberculosis (TB) or other uncontrolled medical conditions, or prespecified abnormal laboratory values were excluded. Patients with latent TB infection were allowed to participate if they had started appropriate anti-TB therapy at least 30 days prior to randomisation (see online supplemental material for additional selection criteria).

annrheumdis-2021-219876supp001.pdf (357.4KB, pdf)

Randomisation and blinding

Patients were randomised 1:1:1 to receive subcutaneous injections of OKZ 64 mg every 2 weeks, OKZ 64 mg once every 4 weeks, or placebo (PBO) for 24 weeks with continuation of their background MTX using an automated randomisation system. Subjects who discontinued the randomised treatment earlier were required to continue the study without study treatment administration; patients could discontinue study treatment but completed the study.

All patients, investigators, clinical site staff, contract research organisation’s staff and the sponsor’s staff directly involved in the study were blinded. Joint assessments were performed by independent assessors, blinded to study drug assignment and all other study assessments (see online supplemental material for additional details).

Rescue medication

Starting at week 14, non-responders, defined as subjects in any treatment group who did not improve by at least 20% in both swollen and tender joint counts (66–68 joints), were prescribed rescue medication (sulfasalazine and/or hydroxychloroquine) in addition to their study treatment (see online supplemental material for details of the prior and concomitant medications).

Endpoints

The primary endpoint was the proportion of patients achieving the American College of Rheumatology 20% (ACR20) response at week 12.

Ranked secondary endpoints were percentage of subjects achieving Disease Activity Score 28 based on C reactive protein (DAS28-CRP) <3.2 at week 12, improvement in physical ability from baseline to week 12 measured by the Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index (HAQ-DI), ACR50 response at week 24 and percentage of subjects with Clinical Disease Activity Index (CDAI) ≤2.8 (remission) at week 24.

Quality of life was assessed using several questionnaires including Short Form-36 (SF-36) Physical Component Summary (PCS), Mental Component Summary (MCS) and total scores, and the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Fatigue Scale (FACIT-F).

Standard safety monitoring, including assessment of adverse events, serious adverse events and laboratory tests via the central laboratory, was performed regularly.

Determination of antidrug antibodies (ADA) in plasma samples was done using electrochemiluminescence assay (Covance Laboratories, Harrogate, North Yorkshire, UK). For detection of neutralising ADAs, a cell-based assay was used (Eurofins BioPharma Product Testing Munich, Planegg/Munich, Germany).

An independent external Data and Safety Monitoring Board reviewed the safety data throughout the study. Major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) were adjudicated by a Cardiovascular Adjudicated Committee and were defined as cardiovascular death or death from undetermined cause, non-fatal myocardial infarction, non-fatal stroke, transient ischaemic attack, hospitalisation for unstable angina requiring unplanned revascularisation and coronary revascularisation procedures.

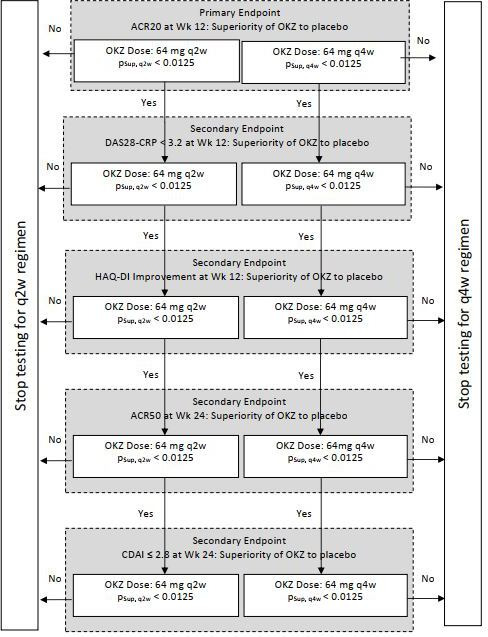

Statistical analyses

The ACR20 response at week 12 for each of the active treatment groups was compared with PBO using a 2×2 χ2 test for equality of proportions. To control the overall type I error rate at a one-sided α=0.025, Bonferroni adjustment was used for the tests related to each of the OKZ dose regimens versus PBO (ie, one-sided α=0.0125 for each dose). A gate-keeping strategy with a fixed order of hypothesis was used for the primary and secondary endpoints within each OKZ dose regimen independently (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Gate-keeping strategy. pSup, q2w and pSup, q4w represent p values from a one-sided test of superiority versus placebo for OKZ dose regimens 64 mg q2w and q4w. ACR, American College of Rheumatology response; CDAI, Clinical Disease Activity Index; DAS28-CRP, Disease Activity Score 28 based on C reactive protein; HAQ-DI, Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index; OKZ, olokizumab; q2w, every 2 weeks; q4w, every 4 weeks; Wk, week.

To detect a difference between at least one OKZ dose regimen and PBO, a sample size of 420 patients randomised in a 1:1:1 ratio was estimated to ensure sufficient disjunctive power (100% for testing the primary hypothesis (ACR20 at week 12) and 98% for the secondary endpoint of DAS28-CRP <3.2 rate at week 12).

The secondary endpoints that were binary in nature were analysed as per the primary endpoint. For analyses of binary variables, inability to remain on randomised treatment through the time point of interest was defined as non-response with respect to the corresponding endpoint. For analyses of binary variables, in case of missing visits or assessments not performed for reasons other than treatment or study discontinuation intermediate missing data were imputed using surrounding visits.

Efficacy endpoints that were continuous in nature were analysed using an analysis of covariance model adjusted for the baseline value of the corresponding parameter. For analyses of continuous endpoints, subjects who discontinued randomised treatment prematurely but remained in the study through the time point of interest were included using all collected measurements, including those from assessments post treatment discontinuation. In case of missing values, return to baseline values was assumed and was implemented using multiple imputation accounting for the uncertainty of missing data according to the methodology of Rubin.15

The primary analysis was performed for intention-to-treat population, defined as all randomised patients. The safety population included all subjects who received at least one dose of the study treatment.

Protocol-specified statistical analyses were performed using Statistical Analysis System V.9.4 or higher.

Results

Disposition

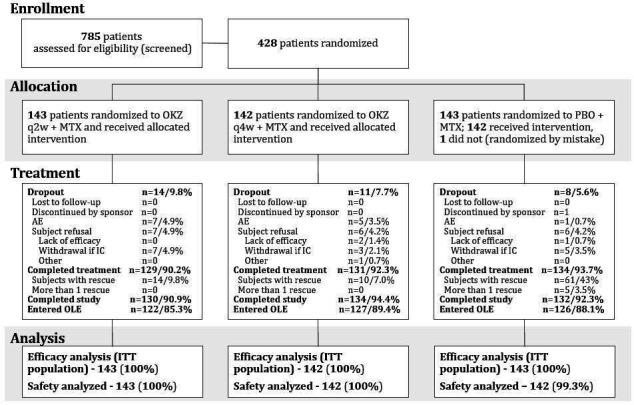

A total of 428 patients were randomised to OKZ 64 mg every 2 weeks (n=143), OKZ 64 mg every 4 weeks (n=142) or PBO (n=143). One patient failed screening, was randomised in error to the PBO group and was withdrawn once the error was discovered, before receiving study treatment; the safety population consisted of 427 subjects (figure 2). The three treatment groups were well balanced for baseline demographic and disease characteristics (table 1).

Figure 2.

Patient disposition. AE, adverse event; IC, informed consent; ITT, intention-to-treat; MTX, methotrexate; OKZ, olokizumab; OLE, open-label extension; PBO, placebo; q2w, every 2 weeks; q4w, every 4 weeks.

Table 1.

Demographic and other baseline characteristics (ITT population)*

| Characteristics, mean (SD) unless otherwise specified | OKZ every 2 weeks N=143 |

OKZ every 4 weeks N=142 |

PBO N=143 |

| Age (years) | 52.0 (11.8) | 49.1 (12.1) | 52.7 (11.3) |

| Female (%) | 81.1 | 83.1 | 83.9 |

| Duration of RA (years) | 8.7 (8.0) | 7.3 (7.0) | 8.4 (7.8) |

| MTX dose (mg)† | 16.1 (3.4) | 16.3 (3.4) | 16.1 (3.7) |

| Duration of prior MTX use (weeks) | 201.5 (232.1) | 157.4 (165.6) | 210.1 (208.2) |

| Glucocorticoid use, n (%) | 52 (36.4)‡ | 50 (35.2)‡ | 41 (28.7)‡ |

| Prednisone dose or equivalent (mg) | 7.6 (6.0) | 6.1 (2.3) | 6.6 (2.4) |

| Prior exposure to TNF inhibitors, n (%) | 0 | 0 | 4 (2.8) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.6 (5.1) | 26.4 (5.5) | 26.9 (5.0) |

| RF+ (≥15 IU/mL), n (%) | 115 (80.4) | 122 (85.9) | 127 (88.8) |

| Anti-CCP+ (>10 IU/mL), n (%) | 110 (76.9) | 115 (81.0) | 117 (81.8) |

| CRP (mg/L)§ | 23.5 (23.1) | 22.7 (22.7) | 25.8 (28.7) |

| TJC¶ | 24.4 (11.4) | 22.2 (10.3) | 24.0 (11.3) |

| SJC¶ | 14.8 (6.5) | 14.5 (6.7) | 14.6 (6.9) |

| DAS28-CRP | 6.0 (0.7) | 5.9 (0.7) | 6.0 (0.8) |

| CDAI score (0–76) | 40.5 (9.8) | 38.7 (9.4) | 40.4 (10.5) |

| HAQ-DI score | 1.74 (0.47) | 1.64 (0.50) | 1.78 (0.49) |

| PtGA (VAS) (mm) | 70.4 (16.0) | 68.5 (14.5) | 69.6 (15.9) |

| Pain (VAS) (mm) | 70.2 (16.3) | 67.4 (18.5) | 68.3 (17.6) |

| PGA (VAS) (mm) | 70.5 (13.9) | 66.4 (14.2) | 68.0 (14.3) |

Pain: patient assessment of pain.

*All patients with exception of one were Caucasian.

†100% patients were on MTX.

‡P=0.33 (χ2 test).

§Upper limit of normal: >6 mg/L.

¶Joint counts were assessed based on 66–68 joint counts.

anti-CCP+, anticyclic citrullinated peptide positivity; BMI, body mass index; CDAI, Clinical Disease Activity Index; CRP, C reactive protein; DAS28-CRP, Disease Activity Score 28 based on C reactive protein; HAQ-DI, Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index; ITT, intention-to-treat; MTX, methotrexate; N, number of subjects; OKZ, olokizumab; PBO, placebo; PGA, Physician Global Assessment of Disease Activity; PtGA, Patient Global Assessment of Disease Activity; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; RF+, rheumatoid factor positivity; SJC, swollen joint count; TJC, tender joint count; TNF, tumour necrosis factor; VAS, Visual Analogue Scale.

A total of 92.1% (n=394) of subjects completed the treatment period: 92.3% (n=131) in OKZ every 4 weeks, 90.2% (n=129) in OKZ every 2 weeks and 93.7% (n=134) in the PBO group. The most common reasons for treatment discontinuation were withdrawal of informed consent and adverse events (figure 2).

A higher proportion of patients in the PBO group (43%) received rescue medication(s) compared with patients on OKZ every 4 weeks (7%) or OKZ every 2 weeks (9.8%).

At week 24 of the study, 122 (85.3%) patients on OKZ every 2 weeks, 127 (89.4%) on OKZ every 4 weeks and 126 (88.1%) on PBO were enrolled in the open-label extension study.

Efficacy

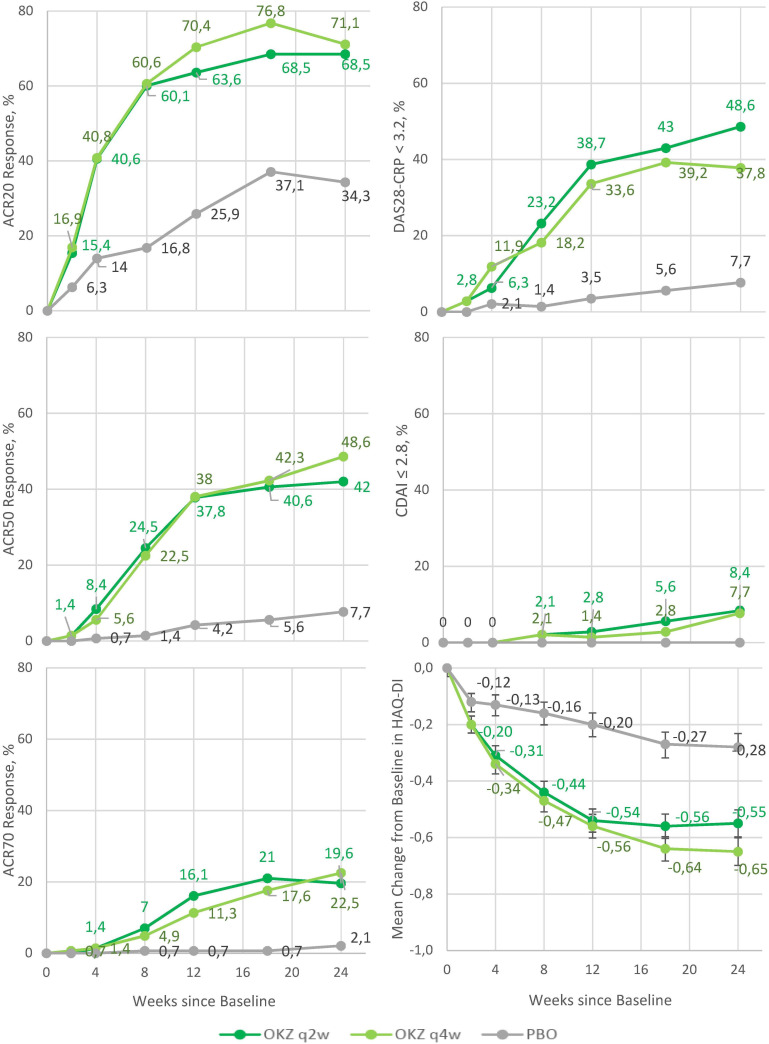

The primary efficacy endpoint, ACR20 response rate at week 12, was 70.4% in OKZ every 4 weeks and 63.6% in OKZ every 2 weeks, both significantly greater than 25.9% in the PBO group (p<0.0001 for both comparisons) (table 2). Separation of the ACR20 response in the OKZ treatment groups from PBO was seen starting around week 2 and plateauing at week 12 (figure 3).

Table 2.

Efficacy results in the intent‐to‐treat population (NRI)

| OKZ every 2 weeks N=143 |

OKZ every 4 weeks N=142 |

PBO N=143 |

|

| ACR20 response, n (%), week 12 (primary endpoint) | 91 (63.6)* | 100 (70.4)* | 37 (25.9) |

| ACR50 response, n (%), week 24 | 61 (42.7)* | 69 (48.6)* | 11 (7.7) |

| ACR70 response†, n (%), week 24 | 28 (19.6) | 32 (22.5) | 3 (2.1) |

| DAS28-CRP <3.2, n (%), week 12 | 48 (33.6)* | 55 (38.7)* | 5 (3.5) |

| HAQ-DI week 12 | |||

| LSM (SE) | −0.54 (0.04) | −0.56 (0.04) | −0.20 (0.04) |

| Treatment comparison vs PBO LSM difference (SE) |

−0.34* (0.06) | −0.36* (0.06) | |

| 97.5% CI for LSM difference | −0.47 to −0.21 | −0.49 to −0.23 | |

| CDAI ≤2.8, n (%), week 24 | 12 (8.4)‡ | 11 (7.7)‡ | 0 |

| DAS28-CRP <2.6†, n (%), week 24 | 31 (21.7) | 40 (28.2) | 5 (3.5) |

| DAS28-CRP, change from baseline, week 24 LSM (SE) |

−2.5 (0.1) | −2.8 (0.1) | −1.2 (0.1) |

| Treatment comparison vs PBO LSM difference (SE) |

−1.4 (0.1) | −1.7 (0.2) | |

| 97.5% CI for LSM difference | −1.7 to −1.0 | −2.0 to −1.4 | |

| CDAI <10†, n (%), week 12 | 37 (25.9) | 40 (28.2) | 7 (4.9) |

*P value difference from PBO <0.0001.

†Results for other than primary and secondary endpoints were not tested for significance.

‡P value difference from PBO <0.001.

ACR, American College of Rheumatology response; CDAI, Clinical Disease Activity Index; DAS28-CRP, Disease Activity Score 28 based on C reactive protein; HAQ-DI, Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index; LSM, least squares mean; N, number of subjects; n, number of responders; NRI, non-responder imputation; OKZ, olokizumab; PBO, placebo.

Figure 3.

Efficacy results during the double‐blind treatment period (ITT population). ACR, American College of Rheumatology response; CDAI, Clinical Disease Activity Index; DAS28-CRP, Disease Activity Score 28 based on C reactive protein; HAQ-DI, Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index; ITT, intention-to-treat; OKZ, olokizumab; PBO, placebo; q2w, every 2 weeks; q4w, every 4 weeks.

The secondary endpoint of DAS28-CRP <3.2 at week 12 was achieved by 33.6% and 38.7% of patients on OKZ every 2 weeks and every 4 weeks, respectively, significantly higher than those in the PBO group (3.5%, p<0.0001 for both comparisons) (table 2, figure 3).

Significant improvements in physical function as assessed with HAQ-DI were observed at week 12 for subjects in both OKZ dosage groups compared with PBO. HAQ-DI improvements from baseline (least squares mean change) were 0.56, 0.54 and 0.20 for every 4 weeks, every 2 weeks and PBO groups, respectively (p<0.0001 for both comparisons) (table 2, figure 3).

The ACR50 response at week 24 was achieved by 48.6% of patients on OKZ every 4 weeks, 42.7% on OKZ every 2 weeks and 7.7% on PBO (p<0.0001 for comparisons of OKZ groups vs PBO) (table 2, figure 3).

Disease remission, defined as CDAI ≤2.8, was achieved at week 24 by 7.7% of patients on OKZ every 4 weeks and by 8.4% on OKZ every 2 weeks. No subjects achieved this endpoint in the PBO group (p=0.0003 for OKZ every 4 weeks vs PBO and p=0.0002 for OKZ every 2 weeks vs PBO comparisons) (table 2, figure 3). The percent mean changes in ACR response criteria parameters and CDAI score parameters are presented in online supplemental figure 1. The number of missing observations for key efficacy outcomes is presented in online supplemental table 1. The results of the primary and ranked secondary endpoints were confirmed by predefined sensitivity analyses and a post-hoc linear mixed model analysis (data available on request).

Subgroup analyses of the ACR20 response did not show influence of country, gender, age, weight, body mass index, baseline disease severity, time since diagnosis, duration of prior MTX use, or anticyclic citrullinated peptide and rheumatoid factor status on the efficacy of OKZ (data available on request).

In parallel with the main efficacy endpoints, there were marked increases (improvement) in SF-36 mental component scores from baseline to week 24 of approximately 8.9, 6.2 and 2.5 in patients on OKZ every 4 weeks, OKZ every 2 weeks and PBO, respectively. Corresponding values for SF-36 physical component scores were 8.7, 7.8 and 3.5. Likewise, FACIT-F improvements were 10.6, 8.5 and 3.7 (table 3). Other quality of life measures showed similar trends in improvement (table 3, online supplemental table 2).

Table 3.

Patient-reported outcome measures at months 3 (12 weeks) and 6 (24 weeks)*

| Week 12 | Week 24 | |||||

| OKZ every 2 weeks N=143 |

OKZ every 4 weeks N=142 |

PBO N=142 |

OKZ every 2 weeks N=143 |

OKZ every 4 weeks N=142 |

PBO N=142 |

|

| PtGA | −30.6 (1.7) 17.5 (2.5) −23.0 to −12.0 |

−31.0 (1.7) −17.9 (2.5) −23.4 to −12.4 |

−13.1 (1.8) | −32.1 (1.9) −12.7 (2.7) −18.8 to −6.6 |

−36.3 (2.0) −16.8 (2.8) −23.0 to −10.6 |

−19.4 (1.9) |

| Pain | −31.6 (1.8) −18.7 (2.6) −24.6 to −12.9 |

−31.8 (1.8) −19.0 (2.6) −24.8 to −13.1 |

−12.8 (1.9) | −34.5 (2.1) −13.0 (2.9) −19.5 to −6.5 |

−37.1 (2.1) −15.7 (2.9) −22.3 to −9.1 |

−21.4 (2.1) |

| Pain, patients with >30% improvement, n (%) | 94 (65.7) | 86 (60.6) | 37 (25.9) | 96 (67.1) | 95 (66.9) | 57 (39.9) |

| Pain, patients with >50% improvement, n (%) | 69 (48.3) | 60 (42.3) | 18 (12.6) | 69 (48.3) | 74 (52.1) | 25 (17.5) |

| Pain, patients with level of <10 mm, n (%) | 12 (8.4) | 13 (9.2) | 0 (0.0) | 23 (16.1) | 24 (16.9) | 6 (4.2) |

| Pain, patients with level of <20 mm, n (%) | 38 (26.6) | 27 (19.0) | 8 (5.6) | 41 (28.7) | 37 (26.1) | 16 (11.2) |

| Pain, patients with level of <40 mm, n (%) | 78 (54.5) | 80 (56.3) | 29 (20.3) | 80 (55.9) | 85 (59.9) | 41 (28.7) |

| HAQ-DI† | −0.55 (0.05) −0.27 (0.07) −0.43 to −0.12 |

−0.65 (0.05) −0.37 (0.07) −0.53 to −0.22 |

−0.28 (0.05) | |||

| HAQ-DI <0.5, n (%) | 13 (9.1) | 13 (9.2) | 2 (1.4) | 17 (11.9) | 21 (14.8) | 5 (3.5) |

| SF-36 PCS | 6.7 (0.6) 4.5 (0.8) 2.7 to 6.3 |

6.0 (0.6) 3.8 (0.8) 2.0 to 5.6 |

2.2 (0.6) | 7.8 (0.7) 4.3 (0.9) 2.2 to 6.4 |

8.7 (0.7) 5.2 (1.0) 3.1 to 7.4 |

3.5 (0.7) |

| SF-36 MCS | 6.5 (0.7) 3.0 (1.0) 0.7 to 5.3 |

7.0 (0.7) 3.6 (1.1) 1.2 to 5.9 |

3.5 (0.8) | 6.2 (0.8) 3.7 (1.1) 1.2 to 6.2 |

8.9 (0.8) 6.4 (1.1) 3.8 to 8.9 |

2.5 (0.8) |

| EQ-5D score | 19.7 (1.7) 12.2 (2.4) 6.8 to 17.6 |

18.7 (1.7) 11.2 (2.4) 5.8 to 16.7 |

7.4 (1.7) | 20.9 (2.0) 12.6 (2.7) 6.5 to 18.7 |

23.6 (2.0) 15.3 (2.8) 8.9 to 21.7 |

8.3 (2.0) |

| FACIT-F | 8.2 (0.7) 4.6 (1.0) 2.4 to 6.8 |

8.7 (0.7) 5.1 (1.0) 2.9 to 7.3 |

3.6 (0.7) | 8.5 (0.8) 4.8 (1.1) 2.3 to 7.3 |

10.6 (0.8) 6.9 (1.1) 4.3 to 9.5 |

3.7 (0.8) |

Pain: patient’s assessment of arthritis pain.

*With the exception of pain, n (%) LSM change from baseline (SE), treatment comparison vs placebo LSM difference (SE), and 97.5% CI for LSM difference are presented.

†Secondary endpoint (refer to table 2).

EQ-5D, European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions; FACIT-F, Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Fatigue Scale (MCID ≥4 units); HAQ-DI, Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index; LSM, least squares mean; MCID, minimal clinically important difference; MCS, Mental Component Score (MCID ≥2.5 units); N, number of subjects; OKZ, olokizumab; PBO, placebo; PCS, Physical Component Score (MCID ≥2.5 units); PtGA, Patient Global Assessment of Disease Activity; SF-36, Short Form-36.

Safety

Two hundred and twenty-six patients (52.9%) reported treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAE) with similar incidences across the treatment groups (table 4).

Table 4.

TEAE by system organ class and preferred term and key serious treatment-emergent adverse events (safety population)

| System organ class (preferred term) |

OKZ every 2 weeks N=143, n (%) |

OKZ every 4 weeks N=142, n (%) |

PBO N=142, n (%) |

| Number of subjects with at least one TEAE reported for 4% of subjects in any treatment group | 83 (58.0) | 81 (57.0) | 62 (43.7) |

| Investigations | 50 (35.0) | 51 (35.9) | 26 (18.3) |

| ALT increased | 25 (17.5) | 33 (23.2) | 11 (7.7) |

| AST increased | 16 (11.2) | 22 (15.5) | 10 (7.0) |

| White cell count decreased | 7 (4.9) | 6 (4.2) | 4 (2.8) |

| Neutrophil count decreased | 6 (4.2) | 7 (4.9) | 3 (2.1) |

| Blood cholesterol increased | 6 (4.2) | 4 (2.8) | 3 (2.1) |

| Gamma-glutamyltransferase increased | 3 (2.1) | 6 (4.2) | 4 (2.8) |

| Infections and infestations | 22 (15.4) | 20 (14.1) | 23 (16.2) |

| Nasopharyngitis | 4 (2.8) | 3 (2.1) | 6 (4.2) |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 2 (1.4) | 6 (4.2) | 4 (2.8) |

| Blood and lymphatic system disorders | 17 (11.9) | 18 (12.7) | 15 (10.6) |

| Leucopenia | 8 (5.6) | 7 (4.9) | 4 (2.8) |

| Neutropaenia | 5 (3.5) | 9 (6.3) | 2 (1.4) |

| Anaemia | 4 (2.8) | 3 (2.1) | 6 (4.2) |

| Metabolism and nutrition disorders | 9 (6.3) | 7 (4.9) | 3 (2.1) |

| Musculoskeletal and connective tissue disorders | 6 (4.2) | 7 (4.9) | 6 (4.2) |

| Skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders | 8 (5.6) | 3 (2.1) | 2 (1.4) |

| Number and percentage with at least one key TESAE | 8 (5.6) | 8 (5.6) | 4 (2.8) |

| Investigations | 2 (1.4) | 4 (2.8) | 1 (0.7) |

| ALT increased | 2 (1.4) | 4 (2.8) | 1 (0.7) |

| AST increased | 0 | 3 (2.1) | 0 |

| Infections and infestations | 4 (2.8) | 0 | 2 (1.4) |

| Subcutaneous abscess | 2 (1.4) | 0 | 0 |

| Gastroenteritis | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.7) |

| Pneumonia | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.7) |

| Pulmonary tuberculosis | 1 (0.7) | 0 | 0 |

| Staphylococcal sepsis | 1 (0.7) | 0 | 0 |

| Toxic shock syndrome | 1 (0.7) | 0 | 0 |

| Herpes zoster | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Hepatobiliary disorders | 0 | 1 (0.7) | 0 |

| Drug-induced liver injury | 0 | 1 (0.7) | 0 |

| Neoplasms benign, malignant and unspecified (including cysts and polyps) |

0 | 1 (0.7) | 0 |

| Cervix carcinoma stage II | 0 | 1 (0.7) | 0 |

| Gastrointestinal disorders | 0 | 1 (0.7) | 0 |

| Obstructive pancreatitis | 0 | 1 (0.7) | 0 |

| Gastrointestinal perforation | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Vascular disorders | 0 | 1 (0.7) | 0 |

| Diabetic vascular disorder | 0 | 1 (0.7) | 0 |

| Venous thromboembolism | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Death | 1 (0.7) | 0 | 0 |

All AEs were collected from the signature of the informed consent form until the last visit of the subject in the study (up to 22 weeks after the final dose of study treatment) regardless of relationship to study treatment, thus up to approximately 44 weeks.

A TEAE is defined as an AE that first occurred or worsened in severity after the first dose of the study treatment.

%, percentage of subjects calculated relative to the total number of subjects in the population.

MedDRA (Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities, V.21.1) was used to code AEs.

AE, adverse event; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; n, number of subjects with events; N, number of subjects; OKZ, olokizumab; PBO, placebo; TEAE, treatment-emergent adverse event; TESAE, treatment-emergent serious adverse event.

Most TEAEs were mild to moderate in severity and non-serious, leading to study treatment discontinuation in 3.5%, 4.9% and 0.7% of patients on OKZ every 4 weeks, OKZ every 2 weeks and PBO, respectively. The most common TEAEs were investigations reported for 35.9% of patients on OKZ every 4 weeks, 35.0% on OKZ every 2 weeks and 18.3% on PBO, and infections reported for 14.1% on OKZ every 4 weeks, 15.4% on OKZ every 2 weeks and 16.2% on PBO. Injection site reactions were reported by two subjects (1.4%) in each OKZ group. A total of 20 treatment-emergent serious adverse events (TESAEs) were reported.

Incidences of TESAEs were numerically higher in patients on OKZ every 4 weeks and OKZ every 2 weeks, compared with PBO: 5.6%, 5.6% and 2.8%, respectively. The most frequently reported serious events were serious infections: 2.8% in patients on OKZ every 2 weeks and 1.4% on PBO (no serious infections were reported for OKZ every 4 weeks). One TEAE leading to death was reported in the study, septicaemia due to Staphylococcus aureus and toxic shock syndrome in the OKZ group every 2 weeks. There were no reports of gastrointestinal perforations or anaphylaxis.

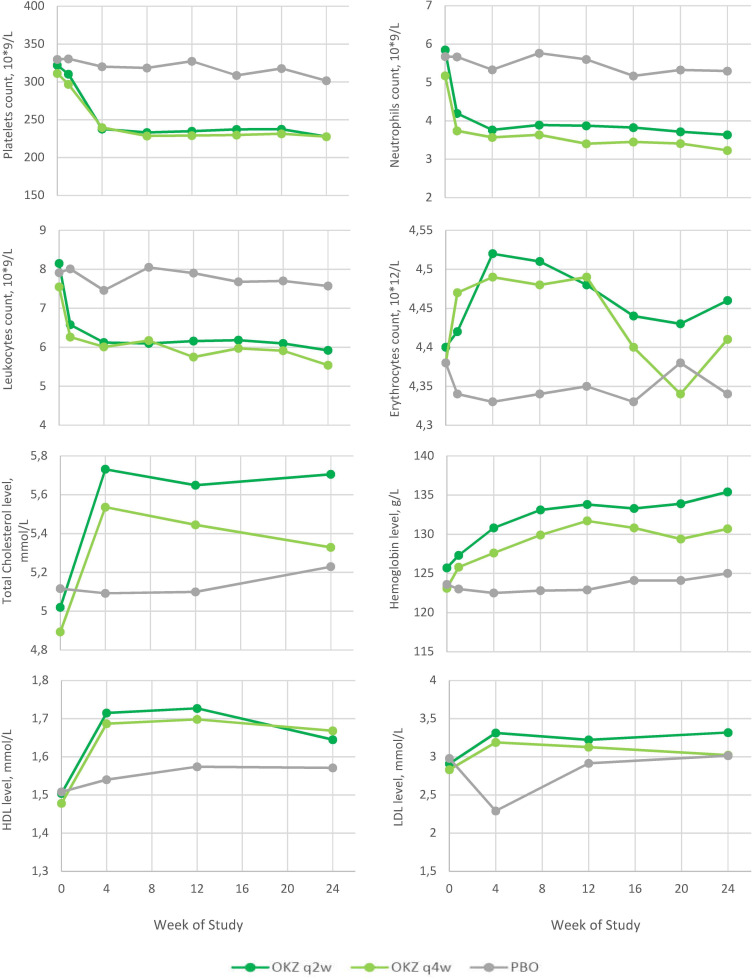

As reported with other anti-IL-6 therapies, there were early rises in mean serum lipids noted from week 4, with a plateau that reached around week 8 (figure 4); however, no MACE was observed. Likewise, early decreases in mean blood platelets and neutrophils were seen, with a plateau reached at week 4. No patients had grade 3 or higher neutropaenia in accordance with the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events version 4.0. Elevations in serum alanine aminotransferase values above 3× ULN at any time during the study were seen in 11.4%, 9.2% and 5.0% of patients on OKZ every 4 weeks, OKZ every 2 weeks and PBO, respectively, with no concomitant elevations in serum bilirubin above 2× ULN. Selected abnormal haematology and chemistry assessments are presented in online supplemental tables 3 and 4.

Figure 4.

Mean changes in laboratory values during the double‐blind treatment period (safety population). HDL, high-density lipoproteins; LDL, low-density lipoproteins; OKZ, olokizumab; PBO, placebo; q2w, every 2 weeks; q4w, every 4 weeks.

Immunogenicity

Positive confirmed ADA tests at any time post baseline were reported in six subjects (4.4%) on OKZ every 2 weeks and in nine subjects (6.6%) on OKZ every 4 weeks. No subjects had a positive result for neutralising antibodies.

Discussion

CREDO 1 trial, a phase III study of OKZ in patients with active RA despite MTX, achieved the primary and all ranked secondary efficacy endpoints. This study evaluated two effective doses with a frequency of injection of once per 2 weeks and once per month, and both regimens of OKZ were superior to PBO in reducing signs and symptoms and improving disability and quality of life over a period of 24 weeks. The onset of efficacy of OKZ was rapid as detected by differences in ACR20 response rates between OKZ and PBO that were apparent within 2 weeks from the start of treatment. The study was specifically designed and sized to detect differences between OKZ and PBO, so small differences seen between OKZ doses in one variable could be by chance, especially since they were not consistently detected across efficacy endpoints. ACR20 was used as the primary endpoint due to its widely accepted and validated value in assessing the efficacy of drugs in RA over many years. While higher levels of response such as ACR50 or ACR70 responses could have been chosen as the primary outcome, use of ACR20 allows for easier comparisons with other compounds evaluated in the past that used ACR20. While ACR20 was the primary endpoint, the study included ACR50 as a ranked secondary endpoint, as well as DAS28-CRP <3.2 and CDAI ≤2.8 (remission), all of which confirmed the results of the ACR20 analysis. In this study patients had relatively high disease activity at baseline, making it more difficult to achieve DAS28-CRP <3.2 status by week 12, as compared with becoming ACR20 responders. Despite this, the data regarding DAS28-CRP <3.2 are consistent with what has previously been reported for anti-IL-6R antibodies, in the same population.8 9 16

Disability is an important aspect of RA that originates from joint pain and joint damage and should be directly assessed in RA clinical trials.17 One of the secondary endpoints in the study was assessment of disability using the HAQ-DI questionnaire.18 19 The study showed that both regimens of OKZ resulted in significantly more improvement in disability than PBO. Additionally, in this patient population and investigational setting, 89 (62.2%) and 94 (66.2%) patients treated with OKZ had improvement in their HAQ-DI score with more than minimally detectable difference of 0.22, compared with 63 (47.6%) in the PBO group.

Chronic arthritis can have a profound effect on patients’ quality of life.20 In this study it was shown that the improvements seen in signs and symptoms and disability of RA were mirrored by positive effects on quality of life measures including SF-36 and FACIT-F. SF-36 is a multidomain questionnaire that assesses different aspects of a person’s life, summarised into PCS and MCS. Treatment with OKZ resulted in improvements across all of these domains (table 3). Certain mental ailments such as sleep disorders and fatigue in RA may be linked to high levels of circulating IL-6.21 22 OKZ treatment resulted in marked improvements in fatigue, consistent with its mechanism of action as an inhibitor of IL-6.

CREDO 1 trial also evaluated the safety of OKZ over 24 weeks and confirmed that OKZ has a safety profile similar to approved anti-IL-6R antagonists and no unexpected safety findings.23 24

As expected, there were more adverse events observed in the OKZ-treated patients, but they were mostly mild to moderate with few serious adverse events and no unexpected safety findings and relatively low number of dropouts due to an adverse event. In this relatively small study few serious infections, including opportunistic infection (pulmonary TB) and one fatal event, were reported for OKZ every 2 weeks and none for OKZ every 4 weeks.

There are several limitations to the study. First, there was no active comparator in this study, limiting the ability to compare with other agents. Second, the study did not include radiographic assessments. An analysis of RA trials of anti-TNF biologics showed a trend towards decreasing rate of radiographic progression, possibly due to more effective patient management, and to reliably show a positive radiographic effect one must include large numbers of patients on PBO, a possible ethical issue.25 Third, this study was conducted in a limited geographical location with limited racial diversity and its findings should be confirmed in other phase III controlled trials that include a more diverse patient population.

Conclusion

In this first phase III trial of OKZ in patients with active RA despite treatment with an adequate dose of MTX, OKZ demonstrated significant improvements in signs and symptoms of RA, including in disability and quality of life measures, compared with PBO. OKZ was reasonably well tolerated over a period of 24 weeks with no unexpected safety findings.

Acknowledgments

We thank all patients who participated in CREDO 1 and the investigators, including the principal investigators: D Abdulganieva, G Arutyunov, D Bichovska, G Chumakova, O Ershova, L Evstigneeva, I Gordeev, E Grunina, N Izmozherova, R Kamalova, A Kastanayan, L Knyazeva, N Korshunov, D Krechikova, T Kropotina, A Maslyanskiy, G Matsievskaya, V Mazurov, I Menshikova, S Moiseev, T Mihailova, N Nikulenkova, D Penev, S Pimanov, T Plaksina, S Polyakova, T Raskina, A Rebrov, T Salnikova, L Savina, Y Schwartz, E Shmidt, E Smolyarchuk, M Stanislav, R Stoilov, T Tyabut, N Vezikova, I Vinogradova, K Yablanski, A Yagoda, S Yakushin and E Zonova. Medical writing assistance, under the direction of the authors, and editorial support were provided by Sofia Kuzkina, MD (CJSC R-Pharm, RF) according to CONSORT 2010 Statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel-group randomised trials (https://www.bmj.com/content/340/bmj.c332)andGoodPublicationPracticeguidelines(http://annals.org/aim/article/2424869).

Footnotes

Handling editor: Josef S Smolen

Presented at: Elements of these data were presented at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology 2019 and the EULAR conference 2020.

Contributors: CJSC R-Pharm was involved in the study design, collection and analysis, interpretation of data, and checking of information provided in the manuscript. MS, SF and EK were involved with study conceptualisation and conducted the data analysis. All authors had unrestricted access to study data and contributed to the interpretation of the results. All authors were responsible for all content and editorial decisions.

Funding: This randomised controlled trial was funded by CJSC R-Pharm. The authors received no honoraria related to the development of this publication.

Competing interests: EN: speakers’ bureau for AbbVie, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Novartis, Pfizer. SF: consulting fees from R-Pharm International, ICON and PPD contract research organisations, shareholder of Pfizer, INC stocks. EF: research grants from BMS, Eli Lilly, Novartis, Roche; consulting fees from AbbVie, BMS, Eli Lilly, Gilead Sciences, Galapagos, Novartis, Roche, Sanofi, Sobi; speakers’ bureau for AbbVie, BMS, Eli Lilly, Gilead Sciences, Galapagos, Medac, Novartis, Roche, Sanofi, Sobi. MI: speakers’ bureau for AbbVie, Eli Lilly, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, UCB. EK: employee of R-Pharm, with no R-Pharm stock. DGK: speakers’ bureau for Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, UCB; research grants from BMS, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Pfizer, R-Pharm. ALM: consulting fees from R-Pharm; speakers’ bureau for AbbVie, Boehringer Ingelheim, Novartis, R-Pharm; other activities for AbbVie, Johnson, MSD, Novartis, Roche, outside the submitted work. MS: employee of R-Pharm, with R-Pharm stock. RS: speakers’ bureau for AbbVie, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, Janssen, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, UCB. EVZ: research grants from AbbVie, Celgene, Janssen, Novartis, Amgen, Pfizer, speakers’ bureau and consultant for AbbVie, Celgene, Janssen, Novartis, Pfizer, Sanofi, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bayer, Sandoz. MG: employee of Gilead Sciences, with Gilead Sciences stock.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information. Data in the form of pdf files can be provided upon reasonable request. The requests should be submitted to Sofia Kuzkina at R-Pharm International at the following email address: kuzkina@rpharm.ru.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

Ethics approval

The study was reviewed by the Ethics Council of the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation (extract of minutes #122, date: 5 April 2016). Prior to the RCT initiation, the study protocol was approved by the ethics committee and regulatory authorities. The study was conducted in accordance with the ICH GCP and the Declaration of Helsinki requirements.

References

- 1. Singh JA, Saag KG, Bridges SL, et al. 2015 American College of rheumatology guideline for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol 2016;68:1–26. 10.1002/art.39480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. McInnes IB, Schett G. The pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med 2011;365:2205–19. 10.1056/NEJMra1004965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Smolen JS, Landewé RBM, Bijlsma JWJ, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: 2019 update. Ann Rheum Dis 2020;79:685–99. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-216655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Winthrop KL, Weinblatt ME, Bathon J, et al. Unmet need in rheumatology: reports from the targeted therapies meeting 2019. Ann Rheum Dis 2020;79:88–93. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-216151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dayer J-M, Choy E. Therapeutic targets in rheumatoid arthritis: the interleukin-6 receptor. Rheumatology 2010;49:15–24. 10.1093/rheumatology/kep329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hunter CA, Jones SA. Il-6 as a keystone cytokine in health and disease. Nat Immunol 2015;16:448–57. 10.1038/ni.3153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Nakashima Y, Kondo M, Harada H, et al. Clinical evaluation of tocilizumab for patients with active rheumatoid arthritis refractory to anti-TNF biologics: tocilizumab in combination with methotrexate. Mod Rheumatol 2010;20:343–52. 10.3109/s10165-010-0290-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Genovese MC, Fleischmann R, Kivitz AJ, et al. Sarilumab plus methotrexate in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis and inadequate response to methotrexate: results of a phase III study. Arthritis Rheumatol 2015;67:1424–37. 10.1002/art.39093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Genovese MC, McKay JD, Nasonov EL, et al. Interleukin-6 receptor inhibition with tocilizumab reduces disease activity in rheumatoid arthritis with inadequate response to disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: the tocilizumab in combination with traditional disease-modifying antirheumatic drug therapy study. Arthritis Rheum 2008;58:2968–80. 10.1002/art.23940 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Shaw S, Bourne T, Meier C, et al. Discovery and characterization of olokizumab: a humanized antibody targeting interleukin-6 and neutralizing gp130-signaling. MAbs 2014;6:774–82. 10.4161/mabs.28612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kretsos K, Golor G, Jullion A, et al. Safety and pharmacokinetics of olokizumab, an anti-IL-6 monoclonal antibody, administered to healthy male volunteers: a randomized phase I study. Clin Pharmacol Drug Dev 2014;3:388–95. 10.1002/cpdd.121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Genovese MC, Fleischmann R, Furst D, et al. Efficacy and safety of olokizumab in patients with rheumatoid arthritis with an inadequate response to TNF inhibitor therapy: outcomes of a randomised phase IIb study. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:1607–15. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Takeuchi T, Tanaka Y, Yamanaka H, et al. Efficacy and safety of olokizumab in Asian patients with moderate-to-severe rheumatoid arthritis, previously exposed to anti-TNF therapy: results from a randomized phase II trial. Mod Rheumatol 2016;26:15–23. 10.3109/14397595.2015.1074648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Aletaha D, Neogi T, Silman AJ, et al. 2010 rheumatoid arthritis classification criteria: an American College of Rheumatology/European League against rheumatism collaborative initiative. Arthritis Rheum 2010;62:2569–81. 10.1002/art.27584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rubin D. Multiple Imputation for Nonresponse in Surveys. Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Yazici Y, Curtis JR, Ince A, et al. Efficacy of tocilizumab in patients with moderate to severe active rheumatoid arthritis and a previous inadequate response to disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: the rose study. Ann Rheum Dis 2012;71:198–205. 10.1136/ard.2010.148700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Orbai A-M, Bingham CO. Patient reported outcomes in rheumatoid arthritis clinical trials. Curr Rheumatol Rep 2015;17:1–10. 10.1007/s11926-015-0501-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Barber CEH, Zell J, Yazdany J, et al. 2019 American College of rheumatology recommended patient-reported functional status assessment measures in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res 2019;71:1531–9. 10.1002/acr.24040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kingsley G, Scott IC, Scott DL. Quality of life and the outcome of established rheumatoid arthritis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2011;25:585–606. 10.1016/j.berh.2011.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gilbert AL, Lee J, Ehrlich-Jones L, et al. A randomized trial of a motivational interviewing intervention to increase lifestyle physical activity and improve self-reported function in adults with arthritis. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2018;47:732–40. 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2017.10.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Choy EHS, Calabrese LH. Neuroendocrine and neurophysiological effects of interleukin 6 in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology 2018;57:1885–95. 10.1093/rheumatology/kex391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mihara M, Hashizume M, Yoshida H, et al. IL-6/IL-6 receptor system and its role in physiological and pathological conditions. Clin Sci 2012;122:143–59. 10.1042/CS20110340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Genovese MC, van der Heijde D, Lin Y, et al. Long-Term safety and efficacy of sarilumab plus methotrexate on disease activity, physical function and radiographic progression: 5 years of sarilumab plus methotrexate treatment. RMD Open 2019;5:e000887. 10.1136/rmdopen-2018-000887 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hushaw LL, Sawaqed R, Sweis G. Critical appraisal of tocilizumab in the treatment of moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis. Ther Clin Risk Manag 2010;6:143–52. 10.2147/tcrm.s5582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Rahman MU, Buchanan J, Doyle MK, et al. Changes in patient characteristics in anti-tumour necrosis factor clinical trials for rheumatoid arthritis: results of an analysis of the literature over the past 16 years. Ann Rheum Dis 2011;70:1631–40. 10.1136/ard.2010.146043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

annrheumdis-2021-219876supp001.pdf (357.4KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information. Data in the form of pdf files can be provided upon reasonable request. The requests should be submitted to Sofia Kuzkina at R-Pharm International at the following email address: kuzkina@rpharm.ru.