Abstract

The two groups of chromosomal β-lactamases from Klebsiella oxytoca (OXY-1 and OXY-2) can be overproduced 73- to 223-fold, due to point mutations in the consensus sequences of their promoters. The different versions of promoters from blaOXY-1 and blaOXY-2 were cloned upstream of the chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (CAT) gene of pKK232-8, and their relative strengths were determined in Escherichia coli and in K. oxytoca. The three different mutations in the OXY β-lactamase promoters resulted in a 4- to 31-fold increase in CAT activity compared to that of the wild-type promoter. The G→T transversion in the first base of the −10 consensus sequence caused a greater increase in the promoter strength of the wild-type promoter than the two other principal mutations (a G-to-A transition of the fifth base of the −10 consensus sequence and a T-to-A transversion of the fourth base of the −35 sequence). The strength of the promoter carrying a double mutation (transition in the Pribnow box and the transversion in the −35 hexamer) was increased 15- to 61-fold in comparison to that of the wild-type promoter. A change from 17 to 16 bp between the −35 and −10 consensus sequences resulted in a ninefold decrease of the promoter strength. The expression of the blaOXY promoter in E. coli differs from that in K. oxytoca, particularly for promoters carrying strong mutations. Furthermore, the blaOXY promoter appears not to be controlled by DNA supercoiling or an upstream curved DNA, but it is dependent on the gene copy number.

β-Lactamases catalyze the hydrolysis of the β-lactam ring of β-lactam antibiotics. Genes that encode β-lactamases can be found on the bacterial chromosome or on plasmids (21). Expression of chromosomal β-lactamase is either inducible (most chromosomal β-lactamases) or constitutive (29). Klebsiella oxytoca is a bacterium that carries a chromosomally encoded β-lactamase, which is naturally synthesized constitutively at a low level.

In a recent study, the chromosomal β-lactamase genes of K. oxytoca were divided into two main groups: blaOXY-1 and blaOXY-2. Some plasmid-encoded β-lactamases, such as MEN-1 (3) and TOHO-1 (16), are derived from these K. oxytoca β-lactamases. The two β-lactamase genes blaOXY-1 and blaOXY-2 were found to be very similar (nucleotide identity, 87.3%) (12). However, it has been demonstrated that OXY-2 β-lactamase hydrolyzed β-lactams differently from OXY-1 β-lactamases, and within the OXY-1 group, some differences in the catalytic efficiencies were also observed (11). Several strains can overproduce β-lactamase 73- to 223-fold (8, 10). This β-lactamase overproduction confers on the bacteria resistance to penicillins and some extended-spectrum β-lactams, especially aztreonam. The molecular basis of this overproduction is point mutations in the promoter consensus sequences of the β-lactamase gene (10). Three types of mutation were described: a G-to-A transition of the fifth base of the −10 consensus sequence, a G-to-T transversion of the first base of the same hexamer, and a T-to-A transversion of the fourth base of the −35 sequence (9). Rarely, a double mutation is observed (9). However, the amounts of β-lactamase in strains carrying the same promoter can be slightly different (9, 10). This could be explained by the difference in β-lactamase substrate profile (11).

In order to verify that the mutations previously described increase the promoter strength and to quantify the effects of these mutations on the promoters, we determined the relative strengths of the different versions of the promoters from blaOXY-1 and blaOXY-2 in two different species, Escherichia coli and K. oxytoca, using a promoter-probe vector. As OXY-1 and OXY-2 β-lactamases have different catalytic efficiencies, the blaOXY promoters were cloned upstream of the cat gene. A 4- to 31-fold increase was observed when the promoter was carrying one of the previously described mutations. The influence of several factors involved in constitutive promoter regulation (supercoiling, upstream promoter DNA sequence, and gene copy number) was also studied.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

The strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. All K. oxytoca strains used for the cloning of promoters were previously identified and analyzed for the promoter sequences and the types (OXY-1 or OXY-2) of their β-lactamases (12).

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Genotype or relevant characteristic(s)a | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| E. coli HB101 | F′ Δ(gpt-proA)62 leuB6 supE44 ara-14 galK2 lacY1 Δ(mcrC-mrr) xyl-5 mtl-1 recA13 rpsL20 (Strr) | Invitrogen |

| K. oxytoca SL781 | Wild-type strain (OXY-1) | 8 |

| K. oxytoca SL7811 | In vitro-overproducing mutant of K. oxytoca SL781 carrying a mutation in the promoter (OXY-1) | 8 |

| K. oxytoca SL901 | Wild-type strain (OXY-1) | 10 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pKK232-8 | Promoter selection vector, replicon pMB1, Apr | Pharmacia |

| pBGS18+ | Cloning vector, replicon pMB1, Kmr | 31 |

| pBluescript II KS(+) | Cloning vector, Apr | Stratagene |

| pBOF-1 | 4-kb EcoRI chromosomal fragment containing bla gene from strain SL781 cloned into pBGS18+ | 8 |

| pBOF-4 | 4-kb EcoRI chromosomal fragment containing bla gene from strain SL7811 cloned into pBGS18+ | 8 |

| pLQ880 | 96-bp HindIII-BamHI fragment containing the tac promoter cloned in pKK232-8 | 19 |

| pLQ921 | 60-bp EcoRI-AluI fragment from pBOF-1 cloned into pBluescript II KS(+) | This study |

| pLQ923 | 60-bp EcoRI-AluI fragment from pBOF-4 cloned into pBluescript II KS(+) | This study |

| pLQ922 | 60-bp BamHI-HindIII fragment from pLQ921 cloned into pKK232-8 | This study |

| pLQ924 | 60-bp BamHI-HindIII fragment from pLQ923 cloned into pKK232-8 | This study |

| pLQ925 to pLQ939 | 360-bp BamHI-HindIII PCR products containing the bla promoters from different K. oxytoca strains cloned into pKK232-8 | This study |

| pLQ940 | 450-bp AvaII (filled)-NarI fragment containing the tac promoter cloned into pBluescript II KS(+) | This study |

| pLQ941 | 450-bp XhoI (filled)-BamHI fragment from pLQ940 containing the tac promoter subcloned into pKK232-8 | This study |

| pLQ943 | Promoter selection vector, replicon pSC101, Apr (constructed from pKK232-8 by replacement of the replicon) | This study |

| pLQ944 to pLQ949 | 360-bp BamHI-HindIII fragments containing the bla promoters from different K. oxytoca strains subcloned into pLQ943 | This study |

| pBF9 | 1.1-kb BamHI-SmaI PCR fragment containing entire bla gene from SL781 cloned into pBGS18+ | This study |

| pBF10 | 1.1-kb BamHI-SmaI PCR fragment containing entire bla gene from SL7811 cloned into pBGS18+ | This study |

| pBF11 | 200-bp EcoRI (filled)-HindIII PCR fragment containing bla promoter without 160-bp fragment upstream of the promoter cloned into pKK232-8 | This study |

Str, streptomycin; Ap, ampicillin; Km, kanamycin.

MICs.

MICs for K. oxytoca strains of novobiocin were determined by an agar dilution method as previously described (8).

Cloning of the bla promoter in pKK232-8.

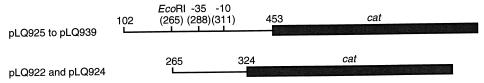

The 480-bp EcoRI-PstI fragments of pBOF-1 and pBOF-4 (8) were isolated and cut with AluI. The 60-bp EcoRI-AluI fragment was cloned into pBluescript II KS(+) (Stratagene) cut with the EcoRI plus EcoRV enzymes to create pLQ921 and pLQ923, respectively. These clones were recut with BamHI plus HindIII, and the fragments were cloned into pKK232-8 (Pharmacia Canada) cut with BamHI plus HindIII to create pLQ922 and pLQ924, respectively (Table 1) (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Maps of DNA fragments cloned in this study. The fragments containing the bla promoters (——) were cloned upstream of the cat gene (■). The EcoRI site and the −35 and −10 regions are also indicated. The numbers refer to the positions of the base pairs according to the sequence of blaOXY-1 (EMBL, GenBank, and DDBJ data library accession no. Z30177).

Other promoter sequences were amplified by PCR by using primers (5′-GGG GAT CCA GCC GGG GCC AA-3′, containing the BamHI site, and 5′-ATC AGC AAG CTT TTG ATG GAT AGC ATC G-3′, containing the HindIII site) and genomic DNA from the different K. oxytoca strains. The PCR products (360 bp) were cut with BamHI plus HindIII and cloned into pKK232-8 cut with BamHI-HindIII to create pLQ925 to pLQ939 (Table 1) (Fig. 1).

The plasmid pMAL-p2 (New England Biolabs) was cut with AvaII, filled in with the Klenow fragment of E. coli DNA polymerase I, and cut with NarI. The resulting 446-bp fragment containing the tac promoter was inserted into pBluescript II KS(+), which was cut with XhoI, filled in with the Klenow fragment, and cut with ClaI. The new plasmid, pLQ940, was cut with EcoO109I, filled in with the Klenow fragment, and cut with BamHI. This fragment was cloned into pKK232-8, which was cut with SalI, filled in with the Klenow fragment, and cut with BamHI. The resulting plasmid, pLQ941, contains the tac promoter upstream of the cat gene.

The 360-bp BamHI-HindIII PCR product amplified from pLQ925 was cut with EcoRI, filled in with the Klenow fragment, and cut with BamHI. The resulting 200-bp fragment containing the bla promoter without the DNA sequence upstream of the promoter was inserted into pKK232-8 cut by SmaI and HindIII to give pBF11 (Table 1).

All promoters were sequenced after their final insertion into plasmids to verify that no mutations occurred during PCR or cloning.

Cloning of the bla gene into pBGS18+.

The entire chromosomal β-lactamase genes of SL781 and SL7811 were cloned into pBGS18+. The primer containing a BamHI site described above and another, previously described, primer containing an SmaI site (11) were used. The PCR products from SL781 and SL7811 cut by BamHI and SmaI were cloned into pBGS18+ (31) cut by the same enzymes to give pBF9 and pBF10, respectively (Table 1).

Enzyme assays.

Enzyme activities were assayed in crude extracts prepared by sonication in 1 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.6) (19). Protein concentrations were measured by the Bradford protein assay (Bio-Rad). Chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (CAT) activity was determined with the phase-extraction assay previously described by Seed and Sheen (30). Crude extracts were diluted in order to have an activity within the linear range of the assay, i.e., 0.5 to 19% butyrylated chloramphenicol. β-Lactamase activity was determined spectrophotometrically at 25°C by using cephaloridine as the substrate as previously described (20).

Plasmid pLQ943 construction.

Plasmid pSC101 (6) was cut by StuI and ligated to eliminate the 1.5-kb region between the two sites. The resulting plasmid, pLQ942, was digested by SphI and EcoRV. The resulting 3.0-kb fragment contained the pSC101 replicon. Plasmid pKK232-8 was digested by AlwNI. The nuclease Bal-31 eliminated about 100 bp of the beginning of RNAII (of the pMB1 replicon). The plasmid was then filled in with the Klenow fragment and cut with NspI. The resulting 3.9-kb fragment containing the bla and cat genes was ligated with the SphI-EcoRV fragment of pSC101 to create the recombinant plasmid pLQ943 (Table 1).

To confirm that the replicon pSC101 was present and that the replicon of pKK232-8 (replicon pMB1) was not functional, two different experiments were performed. First, introduction of a p15A replicon (plasmid pACYC177), which uses a replication mechanism entirely unrelated to those of pMB1 and pSC101, into cells containing the replicon pMB1 (plasmid pBGS18+) or pSC101 (plasmid pSC101) resulted in compatibility between the resident and the incoming plasmids, and this construct was used as a control. If plasmid pLQ943 was introduced into cells containing pBGS18+, the number of transformants was similar to that in the compatibility control and to that in the cells containing the double transformation pSC101-pBGS18+. In contrast, introduction of pLQ943 into cells containing pSC101 resulted in a 10-fold decrease of the efficiency of the transformation. Second, the effect of pLQ943 on the extent of incompatibility expressed by pSC101 or pBGS18+ was further evaluated by an assay that measures the rate of segregation of incompatible plasmids. The pLQ943 plasmid was retained when it was combined with pBGS18+, but it was lost after one subculture when combined with pSC101 (data not shown).

Copy number measurement.

Plasmid pACYC177 was used as an internal control and introduced into the strains carrying the different plasmid constructions. Plasmid DNA concentrations were determined in unfractionated detergent sodium dodecyl sulfate lysates by using the method of Chiang et al. (5). The ethidium bromide-stained agarose gels were photographed, and the DNA bands were quantitated by scanning the photographs with a Bioimage, Visage 110S (Millipore). The density of the larger band was normalized to that of the smaller band (from pACYC177) according to their molecular weights.

RESULTS

β-Lactamase promoter strength in pKK232-8.

The promoters of different OXY β-lactamase genes were cloned upstream of the cat gene of pKK232-8. This plasmid carries a cat gene without a promoter and a blaTEM-1 gene. The CAT activity is proportional to the blaOXY promoter strength, and the TEM β-lactamase activity is proportional to the plasmid copy number (2): determination of the CAT activity to TEM β-lactamase activity ratios was used to avoid effects due to plasmid copy number. These plasmids were introduced into either E. coli HB101 or K. oxytoca SL901. The ratios and the sequences of the promoters are shown in Table 2. The strengths of the wild-type promoters from the β-lactamase genes blaOXY-1 and blaOXY-2 (from plasmids pLQ925 and pLQ927, respectively) were similar: less than a twofold difference was observed. In E. coli, the G→T transversion in the first base of the −10 consensus sequence resulted in a 20-fold increase of the promoter strength of plasmid pLQ925. This increase is greater than that produced by the two other principal mutations. With the same transversion from the blaOXY-2 gene only a fivefold increase was observed. The two other mutations, a transition (G→A at position 5 of the −10 consensus sequence) and a transversion (T→A at position 4 of the −35 consensus sequence), had similar effects, resulting in a four- to ninefold increase over wild-type promoter strength. One promoter carries both of these mutations (transition in the Pribnow box and transversion in the −35 hexamer) (plasmid pLQ939). This promoter resulted in a 15-fold increase in CAT expression in E. coli. Secondary mutations (T→C and G→C at 6 and 4 bp upstream of the −35 consensus sequence, respectively) did not significantly modify the promoter strength either in the wild-type promoter (pLQ926) or in the strong promoters (pLQ929, pLQ930, pLQ933, and pLQ934). However, a G→A mutation at 3 bp downstream of the −10 consensus sequence (plasmid pLQ931) seemed to increase the promoter strength by about twofold.

TABLE 2.

Promoter sequences cloned upstream of the cat gene in pKK232-8 and ratios of CAT activities to TEM β-lactamase activities for these different promoters

| Gene or promoter | Plasmid | Sequencea | CAT activity/TEM β-lactamase activity ratiob in:

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli HB101 | K. oxytoca SL901 | |||

| blaOXY-1 | pLQ925 | GACATAGTGCTTGTCAAAAGCGCGGGAGTCGCGGATAGTCCGGGCAG | 225 ± 26 | 229 ± 13 |

| pLQ922c | ----------------------------------------------- | 136 ± 16 | 179 ± 16 | |

| pLQ926 | ----C------------------------------------------ | 218 ± 36 | NDd | |

| pLQ928 | -------------------------------------A--------- | 1,780 ± 435 | 3,000 ± 128 | |

| pLQ929 | ------C------------------------------A--------- | 1,720 ± 319 | ND | |

| pLQ930 | ----C--------------------------------A---------- | 1,420 ± 180 | ND | |

| pLQ931 | -------------------------------------A---A----- | 2,910 ± 514 | ND | |

| pLQ932 | ---------------------------------T------------- | 4,520 ± 632 | 7,050 ± 38 | |

| pLQ933 | ------C--------------------------T------------- | 4,570 ± 494 | ND | |

| pLQ934 | ----C----------------------------T------------- | 4,450 ± 349 | ND | |

| pLQ924 | ----------------------------- ---T------------- | 300 ± 52 | 314 ± 28 | |

| pLQ935 | -------------A--------------------------------- | 1,920 ± 148 | 2,850 ± 276 | |

| blaOXY-2 | pLQ927 | AATAAATTGCTTGTCAAAATAGCGGGAGTCGCAGATAGTCCGCTGCG | 367 ± 51 | 254 ± 30 |

| pLQ936 | -------------------------------------A--------- | 2,620 ± 376 | 2,600 ± 278 | |

| pLQ937 | ---------------------------------T------------- | 1,800 ± 261 | 2,210 ± 223 | |

| pLQ938 | -------------A--------------------------------- | 1,510 ± 171 | 1,390 ± 91 | |

| pLQ939 | -------------A-----------------------A--------- | 5,590 ± 662 | 15,400 ± 147 | |

| tac | pLQ880 | AAATGAGCTGTTGACA ATTAATCATCGGCTCGTATAATGTGTGGAA | 5,980 ± 797 | ND |

| pLQ941 | ---------------- ------------------------------ | 18,600 ± 427 | 23,400 ± 2,780 | |

The −35 and −10 regions are underlined. The transcriptional start site is shown in bold. Spaces indicate base pair deletions.

Ratios of CAT activity (percent/minute/milligram of protein) to TEM β-lactamase activity (nmoles/minute/milligram of protein) (10−3). All determinations were performed in triplicate. The background CAT activity (pKK232-8) in this assay was not detectable.

Same promoter as pLQ925 but cloned as a 60-bp fragment instead of a 360-bp fragment (see text).

ND, not determined.

The 60-bp fragment of the plasmid pBOF-1 carrying the wild-type promoter was subcloned upstream of the cat gene. The new plasmid, pLQ922, had a CAT activity/TEM β-lactamase activity ratio slightly lower than that of the plasmid pLQ925, probably due to the smaller size of the cloned fragment (the AluI site used in the cloning is close to the transcription initiation site) (Table 2) (Fig. 1). The plasmid pLQ924 carried the same 60-bp fragment harboring the G→T transversion and a one-base deletion located 4 bp upstream of the −10 consensus sequence from pBOF-4. The change of 17 to 16 bp between the two consensus sequences resulted in a ninefold decrease of the promoter strength relative to that of pLQ932, which carries only the transversion.

The strength of the tac promoter was determined with two different plasmids, i.e., plasmid pLQ880, which carries a 90-bp fragment (19), and pLQ941, which carries a 450-bp fragment. A significant difference was observed between the activities of the two plasmids. The CAT activity/TEM β-lactamase activity ratio of pLQ941 was threefold higher than that of plasmid pLQ880, probably again due to the larger size of the cloned fragment.

In K. oxytoca SL901, expression of the wild-type blaOXY-1 and blaOXY-2 promoters was similar to that in E. coli: the difference was less than twofold. However, the ratios of the mutated promoters compared to those of wild type were much higher than those in E. coli for blaOXY-1 and blaOXY-2. This effect was particularly noticeable with the strong mutations, such as the G→T transversion (position 1, Pribnow box) and the double mutation of the plasmid pLQ939. With this plasmid, the ratio became 61-fold instead of 15-fold as in E. coli.

When we quantify the strengths of these mutated promoters on the chromosome by measuring the β-lactamase activity, the promoter mutations are found to increase the promoter strength of the wild-type promoter 76- to 223-fold (8–10). When the ratios of the activities of chromosomally located mutated promoters to wild-type promoters were compared to those obtained with the same promoters located on plasmids (Table 2), a sevenfold lesser difference was observed when the promoters were cloned into a plasmid. We decided to determine the origin of this difference.

Effect of supercoiling on promoter strength.

In order to study the effect of supercoiling on the blaOXY promoter, K. oxytoca SL901 containing the plasmid pLQ925 carrying a wild-type promoter was grown for 2 h during the exponential phase in the presence of three different concentrations of novobiocin (2, 6, and 12 μg/ml, corresponding to 1/15, 1/5, and 1/2.5 of the MIC of novobiocin). Novobiocin inhibits DNA gyrase and reduces supercoiling. However, the CAT and TEM β-lactamase activities of the cells grown in the presence of novobiocin were similar to those of the cells grown in the absence of novobiocin (data not shown), suggesting that the bla promoter is not controlled by supercoiling.

Effect of an upstream DNA sequence on promoter strength.

When we sequenced the region upstream of the β-lactamase gene, we found another apparent divergently transcribed gene whose putative promoter overlapped that of the β-lactamase gene (data not shown). This new gene had similarity with several other genes for which sequences are deposited in the data libraries. These genes, a dehydrogenase involved in rhizopine catabolism in Rhizobium meliloti and a glucose-fructose oxidoreductase of Zymomonas mobilis, are both regulated. This finding suggested that the β-lactamase promoter could be influenced by the regulation of this upstream gene. In order to determine if the DNA located upstream of the promoter influenced blaOXY promoter strength, the BamHI-HindIII fragment containing the wild-type bla promoter was truncated 160 bp by using an EcoRI site present at 18 bp upstream of the −35 consensus sequence of the blaOXY promoter. The putative promoter of the divergently transcribed gene was removed from this new fragment. The activity of this plasmid, pBF11, was compared to that of pLQ925, which carries the whole 360-bp promoter fragment. No significant difference between the CAT activity/TEM β-lactamase activity ratios of pBF11 and pLQ925 was observed (data not shown), indicating that this putative gene does not affect the expression of β-lactamase.

Effect of gene copy number on promoter strength.

In order to verify that the observed difference was related to the plasmid copy number, a plasmid with a copy number lower than that of pKK232-8 was constructed. In plasmid pLQ943, the replicon of plasmid pSC101 was substituted for the pMB1 replicon of pKK232-8. The relative plasmid copy number was determined by two methods. First, the plasmid DNA was extracted and analyzed in agarose gels with pACYC177 used as an internal control. The gel photograph was then scanned. pKK232-8 showed a copy number of 25 copies per cell either in E. coli or in K. oxytoca, while pLQ943 showed copy numbers of 10 copies per cell in E. coli and 7 copies per cell in K. oxytoca. Second, the TEM β-lactamase activities produced by both plasmids were determined. The TEM β-lactamase activity was proportional to the copy number of the plasmid (2). In E. coli, the quantity of β-lactamase produced by pLQ943 was 3.9-fold lower than that produced by pKK232-8, and in K. oxytoca, the difference was 4.7-fold. This confirmed that the plasmid pLQ943 has a copy number about fourfold lower than that of pKK232-8.

The strengths of the different promoters cloned into pLQ943 are shown in Table 3. The ratios of CAT activities to TEM β-lactamase activities are increased by 2.7-fold in E. coli and 2.9-fold in K. oxytoca. As previously mentioned, the TEM β-lactamase activities were decreased fourfold, but the CAT activities in cells containing pLQ943 were only 1.5-fold lower than those in cells containing pKK232-8, indicating an increase of the expression of the promoter as the plasmid copy number decreases. Ratios between the wild-type promoter and the different mutated promoters were higher than that obtained for pKK232-8, particularly for the double mutant: for the plasmid pLQ948, the ratio was 1.7 to 2.1-fold higher than that for the plasmid derived from pKK232-8.

TABLE 3.

Ratios of CAT activities to TEM β-lactamase activities of cells containing the different promoters cloned into pLQ943

| Gene or promoter | Plasmid | Promotera

|

CAT activity/TEM β-lactamase activity ratiob in:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| −35 | ←bp→ | −10 | E. coli HB101 | K. oxytoca SL901 | ||

| blaOXY-1 | pLQ944c | TTGTCA | 17 bp | GATAGT | 614 ± 8 | 663 ± 126 |

| pLQ945 | ------ | 17 bp | ----A- | 6,810 ± 164 | 8,670 ± 564 | |

| pLQ946 | ------ | 17 bp | T----- | 13,000 ± 560 | 28,000 ± 3,030 | |

| pLQ947 | ---A-- | 17 bp | ------ | 11,000 ± 1,100 | 13,300 ± 1,190 | |

| blaOXY-2 | pLQ948 | ---A-- | 17 bp | ----A- | 32,300 ± 3,220 | 76,800 ± 10,100 |

| tacc | pLQ949 | ---A-- | 16 bp | T---A- | 35,000 ± 2,680 | 79,400 ± 6,970 |

The 360-bp BamHI-HindIII fragments of plasmids derived from pKK232-8 (Table 2) were subcloned in pLQ943.

Ratios of CAT activities to β-lactamase activities (see footnote b of Table 2 for units). All measurements were made with at least three independent determinations. The background CAT activity (pLQ943) in this assay was not detectable.

pLQ944 and tac promoters were derived from plasmids pLQ925 and pLQ941, respectively (Table 2).

Two blaOXY genes carrying the 360-bp fragment of the promoter in addition to the entire chromosomal β-lactamase gene were cloned into pBGS18+. One clone carried a wild-type promoter, and the other had the transversion in the −10 consensus sequence. The OXY β-lactamase activities for these plasmids pBF9 (wild-type) and pBF10 (mutated) were determined as well as those for the chromosomal β-lactamase. The results are shown in Table 4. First, between chromosomal wild-type and mutated β-lactamases, a 243-fold increase was observed as previously described (10). Second, between wild-type chromosomal and plasmid-mediated β-lactamase, a 24-fold increase was observed. As described above, the copy number of plasmids carrying the pMB1 replicon as pBGS18+ or pKK232-8 is 25 per cell. The 24-fold increase obtained between the chromosomal and plasmid-mediated locations correlates well with this result. Third, between plasmid-mediated wild-type and mutated β-lactamase promoters, we observed only a 24-fold increase, which correlates well with the 31-fold increase observed for pLQ932 relative to pLQ925 (Table 2). Fourth, the difference between the mutated chromosomal β-lactamase and the mutated plasmid-mediated β-lactamase is only 2.5-fold instead of the expected 25-fold due to the plasmid copy number of pBGS18+. This result indicated that the difference observed between the chromosomal and plasmid-mediated positions is due to the mutated promoter that is not fully overexpressed when it is on the plasmid.

TABLE 4.

Comparison of OXY β-lactamase activities of chromosomal and plasmid-mediated β-lactamase genes

| Strain/plasmid | β-Lactamase promotera

|

OXY β-lactamase activityb | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chromosome | Plasmid | ||

| SL781/none | Wild type | 82 ± 12 | |

| SL7811/none | Mutant | 20,000 ± 2,490 | |

| SL781/pBF9 | Wild type | Wild type | 1,980 ± 284 |

| SL781/pBF10 | Wild type | Mutant | 48,500 ± 8,950 |

The mutated promoter carries the mutation G→T at the first base of the −10 consensus sequence.

See footnote b of Table 2 for units of β-lactamase activity. All measurements were made with at least three independent determinations.

DISCUSSION

The core promoter is composed of the −35 and −10 hexamers separated by a spacer. The promoter specifies more-rapid transcription as its elements approach the consensus sequences: the −35 hexamer (TTGACA), the −10 hexamer (TATAAT), and the spacer between these two sequences (17 bp) (13, 15). Alterations in the strength of nonconsensus promoters are usually dependent on both the position of the substitution and the particular base substituted (17). The three different up-promoter mutations in the β-lactamase promoters cloned into pKK232-8 resulted in a 4- to 31-fold increase of the CAT activity produced by the wild-type (pLQ925) promoter. The G→T transversion of blaOXY-1 in the first base of the −10 consensus sequence causes a greater increase (20-fold in E. coli and 31-fold in K. oxytoca) in the promoter strength for the wild-type promoter than the two other principal mutations. With the same transversion from the blaOXY-2 gene only a fivefold increase is observed. It is difficult to explain the difference observed between the blaOXY-1 and blaOXY-2 promoters carrying the same mutation. However, the base pair just upstream of the −10 consensus sequence is different: it is a G in blaOXY-1 and an A in blaOXY-2 (Table 1). The mutation G→A at this position was shown to decrease 10-fold the activity of the trp promoter (25). This single base-pair difference just upstream of the first base of the −10 hexamer could perhaps affect the efficiency of the up-promoter mutation in the adjacent base. The G→A mutation at 3 bp downstream of the −10 consensus sequence (plasmid pLQ931) seemed to increase the promoter strength about twofold. This mutation is situated between the −10 consensus sequence and the transcriptional start site. The base pair at this position does not seem to be particularly conserved according to the study of compiled promoters (14). However, some up-promoter mutations observed correspond to nonconsensus base pairs (outside the conserved hexamers) altered to other nonconsensus base pairs. These data suggest that a hierarchy of base pair preference could exist at some positions around the hexamers.

The change from 17 to 16 bp in the G→T mutant resulted in a ninefold decrease of the promoter strength in comparison with the level observed for the transversion alone. In the promoter compilation study, 92% of promoters had interregion spacing of 17 bp (14). Maximum activity was observed at a spacer length of 17 bp (1).

It is interesting that the expression of the cloned blaOXY promoters in E. coli is different from that in K. oxytoca, particularly for promoters carrying strong mutations. This might be explained by the fact that E. coli and K. oxytoca RNA polymerases may read the promoter differently. We can speculate that the nature of the RNA polymerases or their relative concentrations within the two cells could affect the relative values of the promoter strength.

The G→T mutant promoter is sevenfold less overexpressed, in comparison to the range observed on the chromosome, when the promoters are cloned into a plasmid. Mechanisms, such as gene amplification, that could contribute to disproportionate overexpression of chromosomal β-lactamase production were eliminated in previous work (10). In addition, our group showed in previous studies (8, 9) that the spontaneous single-step mutants obtained in vitro always carry one mutation in the chromosomal promoter along with a 70- to 200-fold increase of the β-lactamase activity. Finally, we introduced plasmid pLQ925, which carries the wild-type promoter, into K. oxytoca SL781 and SL7811. SL7811, which is a single-step mutant obtained from the wild-type strain SL781, carries the transversion in the −10 consensus sequence and overproduces its chromosomal β-lactamase 223-fold (8). The CAT activities measured from these two strains were similar (data not shown), indicating that no factor acting in trans is involved in this overproduction mechanism. These findings indicate that the promoter mutation alone is responsible for the huge increase of the chromosomal blaOXY production and that the sevenfold difference observed between the cloned and chromosomally located promoters is due only to the former being plasmid borne. Different hypotheses could explain this observation.

The production of β-lactamase in K. oxytoca is constitutive (10, 18). Constitutive promoters are defined as carrying in their sequences all instructions specifying the transcriptional efficiency of their complexes with RNA polymerase, in contrast to regulated promoters, which need positive or negative effectors. During the last decade of research on transcription, it has been shown that several factors could modify the activity of a constitutive promoter. One of the most-studied factors is DNA supercoiling: it influences the expression of many bacterial genes, enhancing or repressing the activity of some of them while having no apparent influence on many others (4, 23, 28). Plasmids in general are much more supercoiled than chromosomal DNA. However, we showed that novobiocin concentrations approaching the MIC do not modify blaOXY promoter strength, suggesting that supercoiling is not a factor involved in expression.

The major determinants of promoter strength are the −35 and −10 hexamers and the conformation of their spacer sequence. However, sequences outside this region but cis to it can strongly influence activity. A survey of nucleotide sequences of promoters indicates a clear relationship between promoter strength and the presence of upstream regions of curved DNA (24, 27). The deletion of the 160-bp sequence upstream of the blaOXY promoter does not modify its activity, indicating that this upstream sequence is not necessary to the promoter strength. Furthermore, no sequences associated with curved or bent DNA were found in this region (data not shown). Another hypothesis is interaction between promoters due to the presence of another gene transcribed divergently from the β-lactamase gene. The promoters of the two genes might have a certain degree of overlap. One of the two promoters may be subject to positive regulation by a factor which represses the activity of the second (and otherwise constitutive) promoter. Although this situation is frequently observed in the regulation of metabolic operons (7, 26), an unrelated gene upstream of the β-lactamase gene could influence the expression of the β-lactamase promoter. Although we found an unrelated gene transcribed divergently from the β-lactamase gene, this gene does not seem to interfere with β-lactamase expression.

The most probable explanation is that promoters that are close to the consensus sequence may be limited in their activities by promoter clearance or by competition among strong promoters for the available RNA polymerase. When we cloned the OXY β-lactamase gene on a pMB1 replicon plasmid, the mutated promoter was not fully overexpressed in comparison to the wild-type promoter (Table 4). Furthermore, when the plasmid copy number was decreased, the expression of all blaOXY promoters remained similar, indicating that the strength of this promoter is dependent on the gene copy number. As it is a strong promoter, particularly when it is mutated, the transcriptional machinery might not support a high level of transcription of one kind of mRNA. There is a limitation in the expression of strong promoters cloned into multicopy plasmids.

This study confirmed that the mutations in the promoter are responsible for the overproduction of the chromosomal β-lactamases in K. oxytoca. Broadening of the spectrum of resistance caused by an overproduction of chromosomal β-lactamases has previously been described. Bacteria increase production of chromosomal β-lactamase by several mechanisms: by promoter mutations or acquisition of insertion sequences that take over promoter function, as occurs with the constitutive β-lactamase of E. coli; by mutation in a regulator gene, as occurs with the inducible β-lactamases of Enterobacter cloacae and Pseudomonas species; or by increased gene copy numbers through gene amplification (22).

In addition, we showed that the three different mutations in the OXY β-lactamase promoters resulted in a 4- to 31-fold increase of the strength of the cloned wild-type promoter. The G→T transversion in the first base of the −10 consensus sequence causes a greater increase in the promoter strength of the wild-type promoter than the two other principal mutations. The expression of the blaOXY promoter in E. coli is different from that in K. oxytoca, particularly for promoters carrying strong mutations. Furthermore, the blaOXY promoter appears not to be controlled by supercoiling or an upstream curved DNA, but it is dependent on the gene copy number.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

B.F. was supported in part by a fellowship from the Ministère de la Recherche et de l’Espace of France, and A.G. was supported by a fellowship from the Medical Research Council (MRC) of Canada. This work was supported by grant MT-13564 from the MRC of Canada to P.H.R. and in part by grant AI23988 from the National Institutes of Health to D.C.H.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aoyama T, Takanami M, Ohtsuka E, Taniyama Y, Marumoto R, Sato H, Ikehara M. Essential structure of Escherichia coli promoter: effect of spacer length between the two consensus sequences on promoter function. Nucleic Acids Res. 1983;11:5855–5864. doi: 10.1093/nar/11.17.5855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arini A, Tuscan M, Churchward G. Replication origin mutations affecting binding of pSC101 plasmid-encoded Rep initiator protein. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:456–463. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.2.456-463.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barthélémy M, Péduzzi J, Bernard H, Tancrède C, Labia R. Close amino acid sequence relationship between the new plasmid-mediated extended-spectrum β-lactamase MEN-1 and chromosomally encoded enzymes of Klebsiella oxytoca. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1992;1122:15–22. doi: 10.1016/0167-4838(92)90121-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brahms J G, Dargouge O, Brahms S, Ohara Y, Vagner V. Activation and inhibition of transcription by supercoiling. J Mol Biol. 1985;181:455–465. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(85)90419-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chiang C-S, Xu Y-C, Bremer H. Role of DnaA protein during replication of plasmid pBR322 in Escherichia coli. Mol Gen Genet. 1991;225:435–442. doi: 10.1007/BF00261684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cohen S N, Chang A C Y. Recircularization and autonomous replication of a sheared R-factor DNA segment in Escherichia coli transformants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1973;70:1293–1297. doi: 10.1073/pnas.70.5.1293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Lorenzo V, Herrero M, Giovannini F, Neilands J B. Fur (ferric uptake regulation) protein and CAP (catabolite activator protein) modulate transcription of fur gene in Escherichia coli. Eur J Biochem. 1988;173:537–546. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1988.tb14032.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fournier B, Arlet G, Lagrange P H, Philippon A. Klebsiella oxytoca: resistance to aztreonam by overproduction of the chromosomally encoded β-lactamase. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1994;116:31–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1994.tb06671.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fournier B, Lagrange P H, Philippon A. β-Lactamase gene promoters of 71 clinical strains of Klebsiella oxytoca. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:460–463. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.2.460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fournier B, Lu C Y, Lagrange P H, Krishnamoorthy R, Philippon A. Point mutation in the Pribnow box, the molecular basis of β-lactamase overproduction in Klebsiella oxytoca. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:1365–1368. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.6.1365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fournier B, Roy P H. Variability of chromosomally encoded β-lactamases from Klebsiella oxytoca. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:1641–1648. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.8.1641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fournier B, Roy P H, Lagrange P H, Philippon A. Chromosomal β-lactamase genes of Klebsiella oxytoca are divided into two main groups: blaOXY-1 and blaOXY-2. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:454–459. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.2.454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gralla J D. Promoter recognition and mRNA initiation by Escherichia coli Eς70. Methods Enzymol. 1990;185:37–54. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(90)85006-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harley C B, Reynolds R P. Analysis of Escherichia coli promoter sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 1987;15:2343–2361. doi: 10.1093/nar/15.5.2343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hawley D K, McClure W R. Compilation and analysis of Escherichia coli promoter DNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 1983;11:2237–2255. doi: 10.1093/nar/11.8.2237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ishii Y, Ohno A, Taguchi H, Imajo S, Ishiguro M, Matsuzawa H. Cloning and sequence of the gene encoding a cefotaxime-hydrolyzing class A β-lactamase isolated from Escherichia coli. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:2269–2275. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.10.2269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kobayashi M, Nagata K, Ishihama A. Promoter selectivity of Escherichia coli RNA polymerase: effect of base substitutions in the promoter −35 region on promoter strength. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:7367–7372. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.24.7367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Labia R, Morand A, Guionie M, Heitz M, Pitton J S. Bêta-lactamases de Klebsiella oxytoca: étude de leur action sur les céphalosporines de troisième génération. Pathol Biol. 1986;34:611–615. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lévesque C, Brassard S, Lapointe J, Roy P H. Diversity and relative strength of tandem promoters for antibiotic-resistance genes of several integrons. Gene. 1994;142:49–54. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90353-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lupski J R, Ruiz A A, Godson G N. Promotion, termination, and antitermination in the rpsU-dnaG-rpoD macromolecular synthesis operon of Escherichia coli K-12. Mol Gen Genet. 1984;195:391–401. doi: 10.1007/BF00341439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Matthew M, Hedges R W, Smith J T. Types of β-lactamase determined by plasmids in gram-negative bacteria. J Bacteriol. 1979;138:657–662. doi: 10.1128/jb.138.3.657-662.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Medeiros A A. Evolution and dissemination of β-lactamases accelerated by generations of β-lactam antibiotics. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;24:S19–S45. doi: 10.1093/clinids/24.supplement_1.s19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meiklejohn A L, Gralla J D. Activation at the lac promoter and its variants. Synergistic effects of catabolite activator protein and supercoiling in vitro. J Mol Biol. 1989;207:661–673. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(89)90236-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ohyama T, Nagumo M, Hirota Y, Sakuma S. Alteration of the curved helical structure located in the upstream region of the β-lactamase promoter of plasmid pUC19 and its effect on transcription. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:1617–1622. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.7.1617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Oppenheim D S, Bennett G N, Yanofsky C. Escherichia coli RNA polymerase and trp repressor interaction with the promoter-operator region of the tryptophan operon of Salmonella typhimurium. J Mol Biol. 1980;144:133–142. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(80)90029-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pagel J M, Winkelman J W, Adams C W, Hatfield G W. DNA topology-mediated regulation of transcription initiation from tandem promoters of the ilvGMEDA operon of Escherichia coli. J Mol Biol. 1992;224:919–935. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)90460-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pérez-Martin J, Rojo F, de Lorenzo V. Promoters responsive to DNA bending: a common theme in prokaryotic gene expression. Microbiol Rev. 1994;58:268–290. doi: 10.1128/mr.58.2.268-290.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pruss G J, Drlica K. DNA supercoiling and prokaryotic transcription. Cell. 1989;56:521–523. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90574-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sanders C C. Inducible β-lactamase and non-hydrolytic resistance mechanisms. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1984;13:1–3. doi: 10.1093/jac/13.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Seed B, Sheen J-Y. A simple phase-extraction assay for chloramphenicol acyltransferase activity. Gene. 1988;67:271–277. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90403-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Spratt B G, Hedge P J, Heesen S T, Edelman A, Broome-Smith J K. Kanamycin-resistant vectors that are analogues of plasmids pUC8, pUC9, pEMBL8 and pEMBL9. Gene. 1986;41:337–342. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(86)90117-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]