Abstract

Transactive response DNA-binding protein 43 kDa (TDP-43) is aberrantly aggregated and phosphorylated in frontotemporal lobar degeneration of the TDP-43 type (FTLD-TDP), and in limbic-predominant age-related TDP-43 encephalopathy neuropathologic change (LATE-NC). We examined data from the National Alzheimer's Coordinating Center to compare clinical features of autopsy-confirmed LATE-NC and FTLD-TDP. A total of 265 LATE-NC and 92 FTLD-TDP participants were included. Cognitive and behavioral symptoms were compared, stratified by level of impairment based on global clinical dementia rating (CDR) score. LATE-NC participants were older at death, more likely to carry APOE ε4, more likely to have Alzheimer disease neuropathology, and had lower (i.e. less severe) final CDR global scores than those with FTLD-TDP. Participants with FTLD-TDP were more likely to present with primary progressive aphasia, or behavior problems such as apathy, disinhibition, and personality changes. Among participants with final CDR score of 2–3, those with LATE-NC were more likely to have visuospatial impairment, delusions, and/or visual hallucinations. These differences were robust after sensitivity analyses excluding older (≥80 years at death), LATE-NC stage 3, or severe Alzheimer cases. Overall, FTLD-TDP was more globally severe, and affected younger participants, whereas psychoses were more common in LATE-NC.

Keywords: Frontotemporal, FTD, Neuropsychiatric, Plaques, Tangles

INTRODUCTION

Limbic-predominant age-related transactive response DNA-binding protein 43 kDa (TDP-43) encephalopathy neuropathologic change (LATE-NC) is increasingly being recognized as a common contributor to cognitive impairment, especially in older age. Abnormally phosphorylated TDP-43 has also been found in other neurodegenerative diseases, including amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and frontotemporal lobe degeneration (FTLD-TDP) (1–3). LATE-NC implies the presence of TDP-43 proteinopathy in one or more of the amygdala, hippocampus, and/or middle frontal gyrus (4), in an anatomic pattern that can usually be discriminated from FTLD-TDP pathology (5). LATE-NC was detected in over 20% of brains in community autopsy series and is especially common (up to 50%) in people over 80 years (4, 6). LATE-NC often co-exists with Alzheimer disease neuropathologic change (ADNC) and/or other neuropathologic entities (7).

This is a fast-moving field, and some controversy exists—particularly in how LATE-NC overlaps with FTLD-TDP and ADNC, both in terms of neuropathologic characteristics and clinical implications (4, 5, 8, 9). It has been suggested that FTLD-TDP and LATE-NC are part of the same spectrum, or that TDP-43 proteinopathy is an “additive” co-pathology with ADNC and therefore requires no diagnostic terminology. However, there are compelling grounds for LATE-NC being a useful diagnostic term. FTLD-TDP is a far rarer condition (i.e. ∼1:1000 lifetime risk) that tends to occur in a younger age group and to present with a wide range of possible neurologic consequences depending on the subtype and the individual, such as behavioral changes (e.g. disinhibition, apathy), language difficulties (e.g. semantic dementia, nonfluent aphasia), and/or cognitive decline (10, 11). By contrast, LATE-NC is far more common, tends to occur in older age, and to present with cognitive decline with similar characteristics, but milder, to that of ADNC (12, 13). In cases with ADNC, those with comorbid LATE-NC have a relatively more severe cognitive impairment compared to those with ADNC alone (6, 14–17).

Relatively few studies have been focused on comparing the clinical features of LATE-NC and FTLD-TDP. One article used a clustering algorithm to detect groupings of types of neuropathologic change and associated those groups with symptoms. Persons with FTLD-TDP had greater degrees of appetite problems, disinhibition, and primary progressive aphasia (PPA). Persons with LATE-NC had cognitive decline, which was relatively slow when it existed in isolation, but more rapid when it co-existed with ADNC and Lewy body disease (18).

Given the high prevalence of LATE-NC, it is important to have better understanding of its cognitive implications and health burden. In addition, being able to differentiate the clinical syndromes associated with LATE-NC and FTLD-TDP and their differing prognoses could help with the management of individual patients. For these reasons, we sought to examine how symptomatic presentation and cognitive performances compared between persons with autopsy-confirmed LATE-NC and FTLD-TDP.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants and Data Source

Data were obtained from the National Alzheimer's Coordinating Center (NACC), which is the data repository for past and present Alzheimer's Disease Research Centers (ADRC) funded by the National Institute of Aging (NIA). Participants are assessed using the standardized Uniform Data Set (UDS) approximately annually at their local ADRC. The UDS collects a robust set of data including participant demographics, health history, physical and neurological exams, Alzheimer disease (AD) and related dementias symptomology, the clinical dementia rating (CDR) Dementia Staging Instrument plus NACC FTLD Behavior and Language Domains, and a neuropsychological test battery. Participants who met the study’s eligibility criteria were selected from the September 2020 data freeze and included cross-sectional data from the participant’s most recent UDS visit prior to death, collected from January 2012 through December 2019. Additional details about the UDS are described elsewhere (19–23). ADRCs obtained written informed consent from their participants and maintain their own separate IRB review and approval from their institution prior to submitting data to NACC.

Neuropathologic Features

Standardized data collection on neuropathological features present at the time of death are available for participants who were assessed with the UDS and who consented to autopsy (19, 23). The NACC neuropathology (NP) form is used by the ADRCs and provides guidance based on established criteria for evaluation of the presence of amyloid, tau, TDP-43, α-synuclein, cerebrovascular injuries, as well as rare pathologies like Huntington disease. Version 10 of the NACC NP (NPv10) form, implemented in January 2014, introduced the assessment of FTLD-TDP and more generally, the presence of TDP-43 immunoreactive inclusions in the spinal cord, amygdala, hippocampus, entorhinal/inferior temporal cortex, and neocortex. In this study, LATE-NC was defined as the presence of TDP-43 inclusions in amygdala, hippocampus, and/or neocortex, and the absence of an overall diagnosis of FTLD-TDP. Determination of FTLD-TDP was based on clinical-pathological consensus at the respective ADRCs. Final FTLD-TDP consensus diagnosis is made by a team of clinicians at the ADRCs, usually primarily by a neuropathologist in consultation with a behavioral neurologist trained in dementia diagnosis.

Inclusion Criteria

Our sample includes participants who died within 3 years of their last UDS visit and have NP data from the NPv10 form. We excluded participants with rare pathologies present (such as Down syndrome, pigment-spheroid degeneration/neurodegeneration with brain iron accumulation (NBIA), multiple system atrophy, trinucleotide disease, Huntington disease, Spinocerebellar ataxia (SCA), other), malformation of cortical development, metabolic/storage disorder of any type, white matter disease (leukodystrophy, multiple sclerosis or other demyelinating disease), contusion/traumatic brain injury of any type (acute or chronic), neoplasm (primary or metastatic), infectious process of any type (encephalitis, abscess, etc.), herniation (any site), Prion disease, FTLD-tau, ALS/motor neuron disease, cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy, or other FTLD. Participants were also excluded if they were missing data on the presence of TDP-43 inclusions in the amygdala, hippocampus, and neocortex, or the presence of FTLD-TDP.

Statistical Analyses

To compare the demographic characteristics, clinical measures, and neuropathologic features between LATE-NC and FTLD-TDP groups, Pearson’s chi-square or Fisher exact tests for the categorical variables, and two-sample t-tests for the continuous variables were applied. Clinical characteristics examined included age at death, presence of the APOE ε4 allele, cognitive status at most recent UDS visit, presumptive etiologic diagnosis at most recent visit, and domain and global CDR scores at most recent UDS visit, including the NACC FTLD Behavior and Language Domains. Neuropathologic features investigated include Thal phase, Braak stage, neuritic plaque density, Lewy bodies, hippocampal sclerosis (HS), brain arteriolosclerosis, infarcts or lacunes, microinfarcts, and hemorrhages and microbleeds. Separate linear regression models unadjusted and adjusted for covariates were run for CDR sum of boxes (CDR-SB), comparing LATE-NC with FTLD-TDP as a reference group. The covariates included known confounders in dementia research (i.e. age at death, sex, years of education), or potential confounders in the relationship between LATE-NC or FTLD-TDP with CDR-SB that were found to have significantly different (at p < 0.05) distributions between our LATE-NC and FTLD-TDP samples (i.e. AD neuropathologic change, presence of Lewy bodies, and presence of microinfarcts). Models were stratified by global CDR score (i.e. CDR = 0.5–1 and 2–3) to examine whether differences are present within groups of participants with similar severity of cognitive impairment. Differences in the presence of cognitive and behavioral symptoms, assessed based on clinician judgment, were also investigated using Pearson’s chi-square or Fisher exact tests, and these comparisons were also stratified by global CDR score. All analyses were run using SAS version 9.4. We used p < 0.05 as the level of statistical significance.

We also ran several sensitivity analyses to assess the robustness of the comparisons of LATE-NC and FTLD-TDP. These reflect various assumptions about the definitions and delineations of the 2 entities. First, we re-ran the analyses using a more restrictive definition of LATE-NC. A hallmark of FTLD-TDP is often the presence of TDP-43 in the middle frontal gyrus. Although TDP-43 proteinopathy can occur in the third stage of LATE-NC, it is usually minimal. Hence, we repeated the analyses deleting participants with stage 3 LATE-NC (i.e. TDP-43 in middle frontal gyrus). Second, we re-ran the analyses using a more restrictive definitions as regards co-occurrence of ADNC. LATE-NC and ADNC often occur together and their co-occurrence is associated with worsened cognitive symptoms. Hence, we repeated the analyses deleting participants with high degrees of ADNC. Third, we re-ran the analyses restricting the sample to only younger participants. The 2 groups differed by age, with LATE-NC having a mean age at death of 11 years older than FTLD-TDP (Table 1). There is also debate as to whether the 2 disorders involve same NP, but with different manifestations at different ages. Hence, we repeated the analyses only looking at the group of participants who died younger, at ages 50–79 years.

TABLE 1.

Participant Demographic and Clinical Characteristics Among LATE-NC and FTLD-TDP

| LATE-NC (n = 265) | FTLD-TDP (n = 92) | p value* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at death, mean (SD) | 83.6 (9.1) | 72.3 (9.7) | <0.001 |

| Female, n (%) | 134 (50.6) | 45 (48.9) | 0.78 |

| Non-white race, n (%) | 20 (7.6) | 2 (2.2) | 0.06 |

| Years of education, mean (SD) | 16.0 (2.9) | 16.0 (2.7) | 0.91 |

| APOE ε4 carrier, n (%) | 146 (59.6) | 23 (29.1) | <0.001 |

| Cognitive status, n (%) | 0.13 | ||

| Normal cognition | 10 (3.8) | 0 (0.0) | |

| MCI | 11 (4.2) | 2 (2.2) | |

| Impaired, not MCI | 3 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Dementia | 241 (90.9) | 90 (97.8) | |

| Primary clinical diagnosis, n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| Normal cognition | 10 (3.8) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Alzheimer disease | 218 (82.3) | 22 (23.9) | |

| Lewy body disease | 12 (4.5) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Frontotemporal disorders | 8 (3.0) | 69 (75.0) | |

| Other | 17 (6.4) | 1 (1.1) | |

| CDR, sum of boxes | 12.4 (5.5) | 14.8 (4.5) | <0.001 |

| CDR, global score | <0.001 | ||

| None | 10 (3.8) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Questionable | 22 (8.3) | 3 (3.3) | |

| Mild | 37 (14.0) | 10 (10.9) | |

| Moderate | 78 (29.4) | 14 (15.2) | |

| Severe | 118 (44.5) | 65 (70.7) |

Missing: LATE-NC education (n = 3), race (n = 1), APOE genotype (n = 20); FTLD-TDP education (n = 1), APOE genotype (n = 13).

CDR, Clinical Dementia Rating; MCI, mild cognitive impairment; SD, standard deviation.

Differences between groups were tested using t-tests for continuous variables, and chi-square or Fisher exact test analysis for categorical variables. Bold values indicate significance at the 0.05 level.

RESULTS

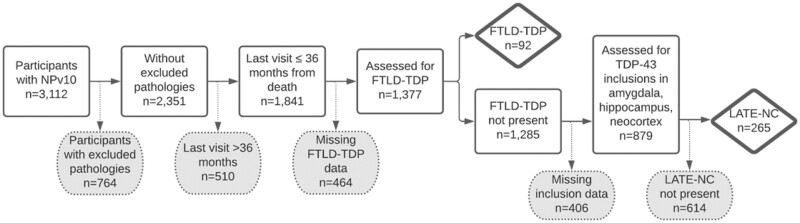

The analytic sample included 357 participants: 265 with LATE-NC and 92 with FTLD-TDP (Fig. 1). There was a significant difference in the mean age at death: those with LATE-NC (mean 83.6 years, standard deviation [SD] 9.1 years) were older than those with FTLD-TDP (mean 72.3 years, SD 9.7 years, p < 0.001; Table 1). Over 80% of LATE-NC cases were presumed to have AD clinically at their most recent visit prior to autopsy; other diagnoses included Lewy body disease (4.5%) and frontotemporal disorders (3.0%). Those with FTLD-TDP were predominantly diagnosed clinically with frontotemporal disorders (75%) or AD (24%). For participants with FTLD-TDP (n = 92), additional categories of dementia subtypes included: semantic PPA: 18.5%; nonfluent/agrammatic PPA: 4.4%; behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia (bvFTD) syndrome: 46.7%; PPA not otherwise specified: 4.4%.

FIGURE 1.

Sample inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Participants with LATE-NC were 2 times more likely than the FTLD-TDP group to be an APOE ε4 carrier (59.6% vs 29.1%, p < 0.001). Despite being more likely to have this dementia risk allele, the LATE-NC group had less severe global CDR scores at their most recent visit prior to death compared to those with FTLD-TDP.

Participants with LATE-NC were more likely to have more severe Thal A-beta phase, Braak neurofibrillary tangle stage, and CERAD neuritic plaque density compared with FTLD-TDP (Table 2). As such, 88.2% of the LATE-NC group had intermediate or high AD neuropathologic change compared to 20.7% of those with FTLD-TDP (p < 0.001). LATE-NC was also more likely to have Lewy bodies (p < 0.001) and microinfarcts (p = 0.006) present as co-pathologic features. No differences were observed between the 2 groups for HS or hemorrhages/microbleeds. LATE-NC participants were more likely to have moderate to severe brain arteriolosclerosis and infarcts/lacunes present compared to FTLD-TDP.

TABLE 2.

Co-Neuropathologic Features Present at Autopsy Among LATE-NC and FTLD-TDP

| LATE-NC (n = 265) |

FTLD-TDP (n = 92) |

p value* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| AD neuropathologic change, n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| Not AD | 6 (2.3) | 39 (42.4) | |

| Low | 25 (9.5) | 34 (37.0) | |

| Intermediate | 36 (13.6) | 10 (10.9) | |

| High | 197 (74.6) | 9 (9.8) | |

| Thal phase, n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| 0 | 6 (2.3) | 39 (42.4) | |

| 1–2 | 13 (4.9) | 25 (27.2) | |

| 3–4 | 62 (23.4) | 18 (19.6) | |

| 5 | 184 (69.4) | 10 (10.9) | |

| Braak stage, n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| 0 | 0 (0.0) | 24 (26.1) | |

| I–II | 22 (8.3) | 40 (43.5) | |

| III–IV | 37 (14.0) | 18 (19.6) | |

| V–VI | 205 (77.7) | 10 (10.9) | |

| Neuritic plaque density, n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| None | 21 (7.9) | 56 (60.9) | |

| Sparse | 20 (7.6) | 12 (13.0) | |

| Moderate | 36 (13.6) | 13 (14.1) | |

| Frequent | 188 (70.9) | 11 (12.0) | |

| Lewy bodies, n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| No Lewy body pathology | 124 (46.8) | 79 (85.9) | |

| Brainstem predominant | 8 (3.0) | 3 (3.3) | |

| Limbic or amygdala predominant | 78 (29.4) | 7 (7.6) | |

| Neocortical | 47 (17.7) | 2 (2.2) | |

| Present, region unspecified | 8 (3.0) | 1 (1.1) | |

| Hippocampal sclerosis, n (%) | 92 (34.9) | 30 (33.0) | 0.74 |

| Vascular brain injury, n (%) | |||

| Brian arteriolosclerosis (moderate/severe) | 151 (57.6) | 39 (45.4) | 0.05 |

| Infarcts or lacunes | 34 (12.8) | 5 (5.4) | 0.05 |

| Microinfarcts | 72 (27.2) | 12 (13.0) | 0.006 |

| Hemorrhages and microbleeds | 15 (5.7) | 3 (3.3) | 0.58 |

Missing: LATE-NC ADNC (n = 1), Braak stage (n = 1), hippocampal sclerosis (n = 1), brain arteriolosclerosis (n = 3); FTLD-TDP hippocampal sclerosis (n = 1), hemorrhages and microbleeds (n = 2), brain arteriolosclerosis (n = 6).

AD, Alzheimer disease; ADNC, Alzheimer disease neuropathologic change.

Differences between groups were tested using chi-square or Fisher exact test. Bold values indicate significance at the 0.05 level.

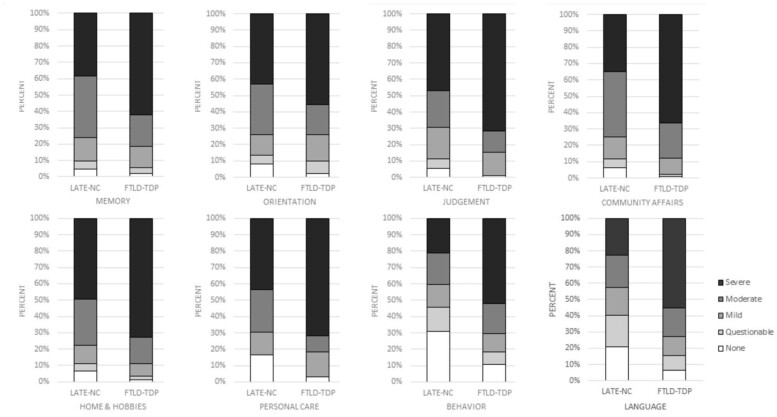

When examining the domain scores of the global CDR, we observed more severe cognitive symptoms among FTLD-TDP in all 8 domains (p < 0.001; Fig. 2). For example, 84.7% of FTLD-TDP participants had moderate to severe impairment in judgment and problem solving, compared to 69.5% of those with LATE-NC. Behavior and language domains, which are captured on the CDR plus NACC FTLD, showed an even starker contrast between the 2 groups with 20%–30% of LATE-NC participants reported as not having impairment in these domains compared to approximately 10% or less of the FTLD-TDP group. Approximately 40% of LATE-NC participants had moderate to severe impairment in these domains, compared to over 70% of those with FTLD-TDP.

FIGURE 2.

CDR dementia staging instrument plus NACC FTLD domain scores among LATE-NC (n = 265) and FTLD-TDP (n = 92)*.

*FTLD-TDP associated with higher CDR categories, at p < 0.001, for all CDR domains. CDR, clinical dementia rating; NACC, National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center.

No differences in CDR-SB scores were detected between the 2 groups among those with global CDR = 0.5–1 or mild impairment; however, participants with more severe impairment showed differences in CDR-SB where those with FTLD-TDP performed worse than those with LATE-NC (p = 0.04). This difference remained statistically significant after adjusting for covariates, including co-occurring neuropathologies, such as ADNC (p = 0.01; Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Unadjusted and Adjusted Mean Difference in CDR-SB at Last Visit Prior to Autopsy Comparing LATE-NC Versus FTLD-TDP (Ref)

| CDR = 0.5–1 |

CDR = 2–3 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β est (95% CI) | p value | β est (95% CI) | p value** | |

| Unadjusted | ||||

| CDR-SB* | −0.01 (−1.74 to 1.72) | 0.99 | −1.23 (−2.43 to −0.04) | 0.04 |

| Adjusted | ||||

| CDR-SB* | −0.54 (−1.92 to 0.84) | 0.44 | −1.46 (−2.63 to −0.30) | 0.01 |

| Adjusted for | ||||

| Age at death | −0.06 (−0.09 to −0.02) | <0.01 | −0.07 (−0.10 to −0.03) | <0.01 |

| Female (male = ref) | 0.76 (−0.43 to 1.95) | 0.21 | 0.50 (0.00–1.01) | 0.05 |

| Years of education | −0.06 (−0.24 to 0.12) | 0.52 | 0.04 (−0.05 to 0.13) | 0.43 |

| ADNC present (none = ref) | ||||

| Low | 1.65 (0.12–3.19) | 0.03 | 0.22 (−0.72 to 1.17) | 0.64 |

| Intermediate | 1.15 (−0.73 to 3.02) | 0.23 | 1.18 (−0.03 to 2.39) | 0.06 |

| High | 2.90 (1.19–4.61) | <0.01 | 0.30 (−0.59 to 1.19) | 0.51 |

| Lewy bodies present (no = ref) | −0.23 (−1.35 to 0.89) | 0.69 | 0.15 (−0.44 to 0.74) | 0.62 |

| Microinfarcts present (no = ref) | −0.23 (−1.31 to 0.85) | 0.68 | −0.21 (−1.04 to 0.62) | 0.62 |

ADNC, Alzheimer disease neuropathologic change; CDR, clinical dementia rating; CI, confidence interval.

A negative value implies worsened functioning for FTLD-TDP participants compared with LATE-NC participants.** Bold values indicate significance at the 0.05 level.

Several differences between LATE-NC and FTLD-TDP emerged when examining cognitive and behavioral symptoms present at the most recent visit prior to death, as determined by clinicians’ judgment (Table 4). Among participants with milder impairment (i.e. CDR = 0.5–1), a larger proportion of participants with FTLD-TDP demonstrated apathy (p = 0.01), disinhibition (p = 0.01), and personality changes (p < 0.001), symptoms typically associated with behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia (bvFTD). These differences were also observed among those with more severe impairment (i.e. CDR = 2–3). Nearly 99% of FTLD-TDP participants exhibited impairments in language, compared to 91% of LATE-NC participants (p = 0.02). LATE-NC participants with severe impairment were more likely to have problems with visuospatial function compared to those with FTLD-TDP (83.4% vs 62.9%, p < 0.001). The severely impaired LATE-NC sample also experienced symptoms of psychosis at a higher percentage than those with FTLD-TDP. Approximately 18% of those with LATE-NC experienced visual hallucinations compared to less than 3% of the FTLD-TDP sample (p = 0.002). Similarly, LATE-NC participants with severe impairment were 3 times more likely to experience delusions than their FTLD-TDP counterparts (p = 0.002).

TABLE 4.

Cognitive and Behavior Symptoms Present at Last UDS Visit Among LATE-NC and FTLD-TDP by Global CDR Score

| CDR = 0.5–1 |

CDR = 2–3 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LATE-NC (n = 59) |

FTLD-TDP (n = 13) |

p value | LATE-NC (n = 196) |

FTLD-TDP (n = 79) |

p value | |

| Cognitive symptoms, n (%) | ||||||

| Memory* | 56 (94.9) | 11 (84.6) | 0.22 | 196 (100.0) | 78 (100.0) | n/a |

| Executive function* | 53 (89.8) | 11 (84.6) | 0.63 | 193 (100.0) | 79 (100.0) | n/a |

| Language | 33 (55.9) | 8 (61.5) | 0.71 | 173 (90.6) | 78 (98.7) | 0.02 |

| Visuospatial* | 20 (35.1) | 3 (23.1) | 0.52 | 152 (83.5) | 44 (62.9) | <0.001 |

| Attention | 21 (35.6) | 8 (61.5) | 0.08 | 156 (83.9) | 64 (85.3) | 0.77 |

| Fluctuating cognition* | 4 (7.1) | 2 (15.4) | 0.31 | 39 (20.9) | 11 (15.1) | 0.29 |

| Behavioral symptoms, n (%) | ||||||

| Apathy | 23 (39.7) | 10 (76.9) | 0.01 | 115 (59.6) | 61 (79.2) | 0.002 |

| Depressed mood* | 21 (35.6) | 4 (30.8) | 1.00 | 61 (32.5) | 16 (22.5) | 0.12 |

| Visual hallucinations* | 3 (5.2) | 0 (0.0) | 1.00 | 32 (17.7) | 2 (2.8) | 0.002 |

| Auditory hallucinations*,† | 0 (0.0) | 1 (7.69) | 0.18 | 4 (2.3) | 3 (4.3) | 0.41 |

| Delusions* | 6 (10.3) | 2 (15.4) | 0.63 | 47 (25.7) | 6 (8.5) | 0.002 |

| Disinhibition* | 6 (10.5) | 7 (53.9) | 0.001 | 47 (24.5) | 44 (56.4) | <0.001 |

| Irritability* | 18 (31.0) | 4 (30.8) | 1.00 | 67 (34.7) | 29 (36.7) | 0.75 |

| Agitation* | 6 (10.3) | 3 (23.1) | 0.35 | 76 (39.2) | 30 (38.0) | 0.85 |

| Personality change* | 5 (8.8) | 7 (53.9) | <0.001 | 28 (14.6) | 35 (44.9) | <0.001 |

| Predominant domain first change* | 0.09 | <0.001 | ||||

| Cognition | 54 (93.1) | 9 (75.0) | 182 (96.8) | 57 (74.0) | ||

| Behavior | 4 (6.9) | 3 (25.0) | 6 (3.2) | 20 (26.0) | ||

Missing: CDR 0.5–1 LATE-NC visuospatial (n = 2), fluctuating cognition (n = 3), apathy (n = 1), visual hallucinations (n = 1), auditory hallucinations (n = 1), delusions (n = 1), disinhibition (n = 2), irritability (n = 1), agitation (n = 1), personality change (n = 2), predominant domain first change (n = 1); FTLD-TDP predominant domain first change (n = 1).

CDR 2–3 LATE-NC executive function (n = 3), language (n = 5), visuospatial (n = 14), attention (n = 10), fluctuating cognition (n = 9), apathy (n = 3), depressed mood (n = 8), visual hallucinations (n = 15), auditory hallucinations (n = 19), delusions (n = 13), disinhibition (n = 4), irritability (n = 3), agitation (n = 2), personality change (n = 4), predominant domain first change (n = 8); FTLD-TDP memory (n = 1), visuospatial (n = 9), attention (n = 4), fluctuation cognition (n = 6), apathy (n = 2), depressed mood (n = 8), visual hallucinations (n = 8), auditory hallucinations (n = 9), delusions (n = 8), disinhibitions (n = 1), personality change (n = 1), predominant domain first change (n = 2).

CDR, clinical dementia rating; n/a, •••; UDS, Uniform Data Set.

Among participants with CDR = 0.5–1, differences between groups were tested using Fisher exact tests due to a large proportion of cells with n < 5. Otherwise, differences between groups were tested using chi-square tests. Bold values indicate significance at the 0.05 level.

Among participants with CDR = 2–3, differences between groups were tested using Fisher's exact tests due to a large proportion of cells with n < 5. Otherwise, differences between groups were tested using chi-square tests. Bold values indicate significance at the 0.05 level.

We ran several sensitivity analyses. The first used a more restrictive definition of LATE-NC, in which only stages 1 and 2 were included (and stage 3 deleted). We found minimal changes compared with the main analyses (Supplementary Data Table S1). Significantly worsened performance of the FTLD-TDP group on adjusted CDR-SB scores persisted for the CDR = 2–3 strata (Table 3 and Supplementary Data Table S1A). Out of 11 cognitive and behavioral symptoms that were significantly different between LATE-NC and FTLD-TDP on the main analysis (Table 4), 10 were still significantly different on the first sensitivity analysis (Supplementary Data Table S1B). Likewise, when examining the domain scores of the global CDR, we observed more severe cognitive symptoms among FTLD-TDP in all 8 domains in the main analysis (Fig. 2), all of which were also significantly different on sensitivity analysis (Supplementary Data Table S1C).

The second sensitivity analysis excluded participants with high ADNC from both LATE-NC and FTLD-TDP. In the main analysis, participants in the more severely impaired strata (global CDR of 2 or 3) showed differences in CDR-SB in which participants with FTLD-TDP performed significantly worse than those with LATE-NC (Table 3). On the sensitivity analysis, these differences were no longer significantly different (Supplementary Data Table S2A). It is interesting to note that the magnitude of the differences between FTLD-TDP and LATE-NC increased, but at least in part because of the notably smaller sample size, the differences were no longer significant. Out of 11 cognitive and behavioral symptoms that were significantly different between LATE-NC and FTLD-TDP on the main analysis (Table 4), 9 were still significantly different on the second sensitivity analysis (Supplementary Data Table S2B). Among less impaired participants (CDR = 0.5–1), the 2 groups no longer differed significantly for apathy, but now did differ for attention. When examining the domain scores of the global CDR, we observed more severe cognitive symptoms among FTLD-TDP in all 8 domains in the main analysis (Fig. 2), all of which were also significantly different on sensitivity analysis (Supplementary Data Table S2C).

The third sensitivity analysis included only participants who had died young, at ages 50–79 years. Significantly worsened performance of the FTLD-TDP group on adjusted CDR-SB scores persisted for the CDR = 2–3 strata (Table 3 and Supplementary Data Table S3A). Out of 11 cognitive and behavioral symptoms that were significantly different between LATE-NC and FTLD-TDP on the main analysis (Table 4), 8 were still significantly different on the second sensitivity analysis (Supplementary Data Table S3B). When examining the domain scores of the global CDR in the main analysis, we had observed more severe cognitive symptoms among FTLD-TDP in all 8 domains in the main analysis (Fig. 2). Only 2 of these were also significantly different on the age-restricted sensitivity analysis (Supplementary Data Table S3C), personal care, and language. It should be noted that almost all of the other comparisons persisted in their direction of worsened outcome for FTLD-TDP, but with diminished statistical significance.

Hence, the findings of the main analysis were largely robust to various assumptions on sensitivity analysis, other than the differences in domain scores when the analysis was restricted to younger participants.

DISCUSSION

We examined how clinical presentation and cognitive performance compared between autopsy-confirmed LATE-NC and FTLD-TDP. FTLD-TDP was associated with a younger age at death and tended to be a more severe disease in terms of global cognition, with a higher percentage of participants in the moderate and severe categories of the CDR global scores. Participants with FTLD-TDP were more likely to have symptoms of apathy, disinhibition, and personality change than participants with LATE-NC. However, some cognitive domains and symptomatology were more adversely affected in persons with LATE-NC than FTLD-TDP. Among participants with more severe impairment (CDR global score of 2–3), participants with LATE-NC were more likely to have difficulties with visuospatial performance and to have symptoms of “psychoses”—visual hallucinations and delusions.

Given the key role of TDP-43 proteinopathy in both LATE-NC and FTLD-TDP, there are ongoing efforts to better delineate the differences between these 2 entities, both in terms of neuropathologic characteristics and clinical implications (4, 5). LATE-NC tends to occur in older age and to present with cognitive decline with similar amnestic-type characteristics, but milder, to that of AD (12, 13). On the other hand, FTLD-TDP can present with behavioral changes (e.g. disinhibition, apathy), language difficulties (e.g. semantic dementia, nonfluent aphasia), or decline in other cognitive domains (11).

A prior study by Katsumata et al was also based on NACC data and used a clustering algorithm to detect groupings of types of neuropathologic change with symptoms, among participants with TDP-43 proteinopathy. It identified several clusters of NP and symptoms, including FTLD-TDP, LATE-NC without ADNC, and LATE-NC with ADNC. Persons with FTLD-TDP had appetite problems, disinhibition, and PPA. Persons with LATE-NC had cognitive decline, which was relatively slow when it existed in isolation, but more rapid when it co-existed with ADNC (18).

The current study builds on the above-noted prior study using different methodologies. Although both studies were based on participants in the NACC database, Katsumata et al used all persons in the NACC database who had TDP-43 in at least one of the regions (amygdala, hippocampus, or neocortex), whereas the current study focused on a smaller number of participants who had sufficient data to evaluate staging for LATE-NC. In terms of analytic methods, Katsumata et al used clustering analysis (irrespective of the final pathological diagnostic entities of FTLD-TDP and LATE-NC), whereas the current study used a focused direct comparison of the cognitive function and behavioral symptoms of persons with LATE-NC and FTLD-TDP. Finally, Katsumata et al used symptom data captured by the Neuropsychiatric Inventory Questionnaire, an informant-based assessment, whereas the current study used clinician-assessed symptoms. An important question in our study is whether or not the delusions and hallucinations were attributable to the ADNC. The Katsumata et al study affirms that such is not the case. Hence, the 2 studies are complementary.

The current study confirmed the finding of a higher proportion of individuals with disinhibition among FTLD-TDP participants. It also showed a very high proportion of persons who reported any language difficulties. Severe problems in the language domain were more common for FTLD-TDP participants according to the CDR Dementia Staging Instrument plus NACC FTLD Domains. The current study also found a higher proportion of persons with apathy among the FTLD-TDP group than the LATE-NC group. It is notable that not all the cognitive domains were more severely impaired or affected in FTLD-TDP in comparison to LATE-NC. There was worse visuospatial performance and higher levels of symptoms of visual hallucinations and delusions among LATE-NC participants compared to FTLD-TDP participants. This underscores that the clinical features associated with LATE-NC are not merely milder than those associated with FTLD-TDP, they are different.

Relative to comparisons between LATE-NC and FTLD-TDP, more attention has been directed towards comparisons between LATE-NC and ADNC. Kapasi et al (15) used data from Rush University’s autopsy cohorts and found that cognitive decline was most severe in the presence of ADNC + LATE-NC, followed by ADNC alone, followed by LATE-NC alone, followed by neither pathology. Similar findings have been described in the University of Kentucky AD Research Center and other autopsy cohorts (16, 24, 25). Liu et al used data from the Brains for Dementia Research cohort in the United Kingdom. They found that LATE-NC along with ADNC was not associated with greater neuropsychiatric symptom burden compared with ADNC alone (17). By contrast, in a study of 1716 participants using NACC NP data, Sennik et al (26) found that symptoms associated with ADNC with comorbid TDP-43 proteinopathy included “delusions, hallucinations, and depression, but not irritability, aberrant motor behavior, sleep, and nighttime behavioral changes.”

LATE-NC has been associated with comorbid HS pathology (4, 14, 27). In the current study, we did not show a difference in proportion of participants with HS for LATE-NC versus FTLD-TDP, with both conditions having approximately 30% of participants with HS (Table 2). Katsumata et al (18) correspondingly found the prevalence of HS to be similar among the LATE-NC and FTLD-TDP-enriched clusters and these findings are also consistent with results of a recent study that focused on FTLD-TDP (28).

One could make an argument that our study design reflected circular logic: many of the cases with FTLD-TDP were placed into that group partly due to clinical symptoms (although, we note, ∼1/4th of the FTLD-TDP cases were diagnosed clinically as “Probable AD”; Table 1). This point needs to be kept in mind but does not negate the importance of the data presented. Instead, this consideration reframes the project to a broader question: Is there a common, aging-related, clinical-pathological entity that differs according to clinical and pathological parameters from the far rarer, younger-onset frontotemporal dementia (FTD) clinical syndrome with TDP-43 proteinopathy? We could set aside the large differences in the age of onset and death, and the FTD-type findings of behavioral and language symptoms that helped steer the diagnostic categories. Even if so, the global cognition which is more severe in FTLD-TDP (Fig. 2), the co-pathologies (Table 2), and the neuropsychiatric symptoms that are worse in LATE-NC (Table 4) differ substantially between LATE-NC and FTLD-TDP. Presumably, there are some pathogenetic mechanisms that are shared between LATE-NC and FTLD-TDP (as there are between LATE-NC and ADNC, and ADNC and DLB), but the usefulness of LATE-NC as a diagnostic term is corroborated for clinical and research purposes.

It is also possible that TDP-43 pathology exists along a continuum with different clinical phenotypes of disease expressed in earlier onset versus later onset cases. Parallels exist for AD and other neurologic disorders. As such, the use of clinicopathologic diagnosis may confound the present findings. On the other hand, the striking difference in clinical phenotypes between the cases presented in this report with FTLD-TDP and LATE-NC may suggest that such clinical phenotypes are distinct diseases sharing convergent pathologic features (i.e. TDP-43 proteinopathy). Such concepts have clearly been noted for other disorders. Just as tau inclusions may be a sign of FTLD-Tau, they are also common features of AD, primary age-related tauopathy, corticobasal degeneration, progressive supranuclear palsy, aging-related tau astrogliopathy, chronic traumatic encephalopathy, and others. Similar examples include α-synuclein pathologies in Parkinson disease, dementia with Lewy bodies, and multiple system atrophy. It is widely accepted that such clinical-pathologic defined disease states are distinct, and likewise TDP-43 inclusions are not disease-specific, but rather represent a pathologic feature for at least 15 other neurologic diseases (3). As such, the present work underscores that TDP-43 proteinopathy is not only a marker for diseases on the ALS/FTLD-TDP spectrum.

To be clear, we are not suggesting that clinical criteria should be used as the sole basis for differentiation of neurodegenerative diseases. Better identification of biomarker, neuropathologic, and genetic criteria to differentiate FTLD-TDP and LATE-NC is a necessary step for future work. Some progress has already been made on this. For example, recent work has shown that the density of TDP-43 proteinopathy in neocortical regions is substantially more severe in FTLD-TDP than in LATE-NC, enabling the accurate diagnosis of those conditions in >95% of cases from 2 large autopsy cohorts (5). We note that there are also examples of diagnostic border zone issues for unusual cases with tauopathies and α-synucleinopathies as well.

Regarding the effects of age, it is notable that in the third sensitivity analysis (restricted to people who had died younger than age 80), the significance of the differences in CDR global score domain scores which had been present in the main analysis (Fig. 2) was decreased in the sensitivity analysis (Supplementary Data Table S3C). This may indicate that younger people with LATE-NC tend to have more severe manifestations (and hence less differences from FTLD-TDP in terms of severity). On the other hand, the statistical finding also reflects the sharply reduced sample size after eliminating the older LATE-NC participants.

Other potential limitations of the current study should also be considered. First, study participants were more highly educated and more likely to be Caucasian than the general population, limiting the generalizability to more diverse populations. Second, there remains controversy in differentiating LATE-NC and FTLD-TDP neuropathologically (5). Third, the study involved cross-sectional data, which may be less sensitive than longitudinal data in detecting subtle differences, especially early in cognitive dysfunction (29, 30). Finally, there was a high percentage of intermediate and high ADNC among participants with LATE-NC. Substantial amounts of the symptoms in this group were presumably driven by the ADNC rather than by the LATE-NC. We have, in part, addressed this issue through adjusting for ADNC on multivariable analysis (Table 3) and by restricting the analyses to persons with high ADNC (Supplementary Data Tables S2A–C).

Despite these limitations, this study has key strengths. It is based on multi-institutional data, drawing on a large, sex-balanced group of participants from across the United States, and the questionnaires through which the data are collected were administered in standardized fashion at all the different research centers. Likewise, neuropathological changes were assessed at autopsy using standardized up-to-date techniques (all autopsies reported after the year 2014) and reporting methods (23, 31). The inclusion of 92 autopsy-confirmed FTLD-TDP cases in a study with detailed clinical testing is a relatively large study sample by historical standards. The great majority of participants in both study groups had dementia so the groups could be compared stage-for-stage. Thus, these data allowed us to draw conclusions about the symptomatic presentation and cognitive performance and to compare between cognitively impaired participants with autopsy-confirmed LATE-NC and FTLD-TDP.

In conclusion, we found that LATE-NC tended to have a clinical phenotype that differed substantially in comparison to FTLD-TDP. Participants with FTLD-TDP died younger and were more likely to have symptoms of apathy, disinhibition, and personality change. This was true across the spectrum from mild cognitive impairment to advanced dementia. By contrast, participants with LATE-NC (even those lacking severe ADNC) were more likely to have difficulties with visuospatial performance and to have symptoms of visual hallucinations and delusions. These data allow better understanding of the public health burden accruing from each of these entities.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to the research volunteers, their families and caregivers, and our colleagues at the NIA-funded Alzheimer's Disease Research Centers.

Contributor Information

Merilee A Teylan, From the National Alzheimer's Coordinating Center, Department of Epidemiology, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, USA.

Charles Mock, From the National Alzheimer's Coordinating Center, Department of Epidemiology, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, USA.

Kathryn Gauthreaux, From the National Alzheimer's Coordinating Center, Department of Epidemiology, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, USA.

Jessica E Culhane, From the National Alzheimer's Coordinating Center, Department of Epidemiology, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, USA.

Gregory Jicha, Sanders-Brown Center on Aging, University of Kentucky, Lexington, Kentucky, USA.

Yen-Chi Chen, From the National Alzheimer's Coordinating Center, Department of Epidemiology, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, USA.

Kwun C G Chan, From the National Alzheimer's Coordinating Center, Department of Epidemiology, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, USA.

Walter A Kukull, From the National Alzheimer's Coordinating Center, Department of Epidemiology, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, USA.

Peter T Nelson, Sanders-Brown Center on Aging, University of Kentucky, Lexington, Kentucky, USA; Division of Neuropathology, Department of Pathology, University of Kentucky, Lexington, Kentucky, USA.

Yuriko Katsumata, From the National Alzheimer's Coordinating Center, Department of Epidemiology, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, USA; Department of Biostatistics, University of Kentucky, Lexington, Kentucky, USA.

The NACC database is funded by NIA/NIH Grant U01 AG016976. NACC data are contributed by the NIA-funded ADRCs: P30 AG019610 (PI Eric Reiman, MD), P30 AG013846 (PI Neil Kowall, MD), P50 AG008702 (PI Scott Small, MD), P50 AG025688 (PI Allan Levey, MD, PhD), P50 AG047266 (PI Todd Golde, MD, PhD), P30 AG010133 (PI Andrew Saykin, PsyD), P50 AG005146 (PI Marilyn Albert, PhD), P50 AG005134 (PI Bradley Hyman, MD, PhD), P50 AG016574 (PI Ronald Petersen, MD, PhD), P50 AG005138 (PI Mary Sano, PhD), P30 AG008051 (PI Thomas Wisniewski, MD), P30 AG013854 (PI Robert Vassar, PhD), P30 AG008017 (PI Jeffrey Kaye, MD), P30 AG010161 (PI David Bennett, MD), P50 AG047366 (PI Victor Henderson, MD, MS), P30 AG010129 (PI Charles DeCarli, MD), P50 AG016573 (PI Frank LaFerla, PhD), P50 AG005131 (PI James Brewer, MD, PhD), P50 AG023501 (PI Bruce Miller, MD), P30 AG035982 (PI Russell Swerdlow, MD), P30 AG028383 (PI Linda Van Eldik, PhD), P30 AG053760 (PI Henry Paulson, MD, PhD), P30 AG010124 (PI John Trojanowski, MD, PhD), P50 AG005133 (PI Oscar Lopez, MD), P50 AG005142 (PI Helena Chui, MD), P30 AG012300 (PI Roger Rosenberg, MD), P30 AG049638 (PI Suzanne Craft, PhD), P50 AG005136 (PI Thomas Grabowski, MD), P50 AG033514 (PI Sanjay Asthana, MD, FRCP), P50 AG005681 (PI John Morris, MD), P50 AG047270 (PI Stephen Strittmatter, MD, PhD). Dr. Nelson is supported by NIA/NIH grants R01 AG061111, RF1 NS118584. Dr. Katsumata is supported by NIA/NIH grants R56AG057191, R01AG057187, R21AG061551, R01AG054060, and the UK-ADC P30AG028383 from the National Institute on Aging.

The authors have no duality or conflicts of interest to declare.

Supplementary Data can be found at academic.oup.com/jnen.

REFERENCES

- 1. Cairns NJ, Bigio EH, Mackenzie IR, et al. ; Consortium for Frontotemporal Lobar Degeneration. Neuropathologic diagnostic and nosologic criteria for frontotemporal lobar degeneration: Consensus of the consortium for frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Acta Neuropathol 2007;114:5–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Neumann M, Sampathu DM, Kwong LK, et al. Ubiquitinated TDP-43 in frontotemporal lobar degeneration and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Science 2006;314:130–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chornenkyy Y, Fardo DW, Nelson PT. Tau and TDP-43 proteinopathies: Kindred pathologic cascades and genetic pleiotropy. Lab Invest 2019;99:993–1007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Nelson PT, Dickson DW, Trojanowski JQ, et al. Limbic-predominant age-related TDP-43 encephalopathy (LATE): Consensus working group report. Brain 2019;142:1503–27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Robinson JL, Porta S, Garrett FG, et al. Limbic-predominant age-related TDP-43 encephalopathy differs from frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Brain 2020;143:2844–57 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Nag S, Barnes LL, Yu L, et al. Limbic-predominant age-related TDP-43 encephalopathy in Black and White decedents. Neurology 2020;95:e2056–64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Josephs KA, Martin PR, Weigand SD, et al. Protein contributions to brain atrophy acceleration in Alzheimer's disease and primary age-related tauopathy. Brain 2020;143:3463–76 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Josephs KA, Mackenzie I, Frosch MP, et al. LATE to the PART-y. Brain 2019;142:e47. Erratum in: Brain 2019;142:e73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Nelson PT, Dickson DW, Trojanowski JQ, et al. Reply: LATE to the PART-y. Brain 2019;142:e48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Coyle-Gilchrist IT, Dick KM, Patterson K, et al. Prevalence, characteristics, and survival of frontotemporal lobar degeneration syndromes. Neurology 2016;86:1736–43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mann DMA, Snowden JS. Frontotemporal lobar degeneration: Pathogenesis, pathology and pathways to phenotype. Brain Pathol 2017;27:723–36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Boyle PA, Yang J, Yu L, et al. Varied effects of age-related neuropathologies on the trajectory of late life cognitive decline. Brain 2017;140:804–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Josephs KA, Dickson DW, Tosakulwong N, et al. Rates of hippocampal atrophy and presence of post-mortem TDP-43 in patients with Alzheimer's disease: A longitudinal retrospective study. Lancet Neurol 2017;16:917–24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Besser LM, Teylan MA, Nelson PT. Limbic predominant age-related TDP-43 encephalopathy (LATE): Clinical and neuropathological associations. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 2020;79:305–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kapasi A, Yu L, Boyle PA, et al. Limbic-predominant age-related TDP-43 encephalopathy, ADNC pathology, and cognitive decline in aging. Neurology 2020;95:e1951–62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Karanth S, Nelson PT, Katsumata Y, et al. Prevalence and clinical phenotype of quadruple misfolded proteins in older adults. JAMA Neurol 2020;77:1299–307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Liu KY, Reeves S, McAleese KE, et al. Neuropsychiatric symptoms in limbic-predominant age-related TDP-43 encephalopathy and Alzheimer's disease. Brain 2020;143:3842–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Katsumata Y, Abner EL, Karanth S, et al. Distinct clinicopathologic clusters of persons with TDP-43 proteinopathy. Acta Neuropathol 2020;140:659–74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Beekly DL, Ramos EM, van Belle G, et al. ; NIA-Alzheimer's Disease Centers. The National Alzheimer's Coordinating Center (NACC) database: An Alzheimer disease database. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 2004;18:270–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Morris JC, Weintraub S, Chui HC, et al. The Uniform Data Set (UDS): Clinical and cognitive variables and descriptive data from Alzheimer Disease Centers. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 2006;20:210–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Beekly DL, Ramos EM, Lee WW, et al. ; NIA Alzheimer's Disease Centers. The National Alzheimer's Coordinating Center (NACC) database: The Uniform Data Set. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 2007;21:249–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Besser LM, Kukull W, Knopman DS, et al. ; Neuropsychology Work Group, Directors, and Clinical Core leaders of the National Institute on Aging-funded US Alzheimer's Disease Centers. Version 3 of the National Alzheimer's Coordinating Center's Uniform Data Set. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 2018;32:351–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Besser LM, Kukull WA, Teylan MA, et al. The revised National Alzheimer's Coordinating Center's neuropathology form—Available data and new analyses. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 2018;77:717–26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Nelson PT, Abner EL, Schmitt FA, et al. Modeling the association between 43 different clinical and pathological variables and the severity of cognitive impairment in a large autopsy cohort of elderly persons. Brain Pathol 2010;20:66–79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Nelson PT, Smith CD, Abner EL, et al. Hippocampal sclerosis of aging, a prevalent and high-morbidity brain disease. Acta Neuropathol 2013;126:161–77 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sennik S, Schweizer TA, Fischer CE, et al. Risk factors and pathological substrates associated with agitation/aggression in Alzheimer's disease: A preliminary study using NACC data. J Alzheimers Dis 2017;55:1519–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Amador-Ortiz C, Lin WL, Ahmed Z, et al. TDP-43 immunoreactivity in hippocampal sclerosis and Alzheimer's disease. Ann Neurol 2007;61:435–45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sieben A, Van Langenhove T, Vermeiren Y, et al. Hippocampal sclerosis in frontotemporal dementia: When vascular pathology meets neurodegeneration. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 2021;80:313–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Knopman DS, Caselli RJ. Appraisal of cognition in preclinical Alzheimer's disease: A conceptual review. Neurodegener Dis Manag 2012;2:183–95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Riley KP, Jicha GA, Davis D, et al. Prediction of preclinical Alzheimer's disease: Longitudinal rates of change in cognition. J Alzheimers Dis 2011;25:707–17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Montine TJ, Monsell SE, Beach TG, et al. Multisite assessment of NIA-AA guidelines for the neuropathologic evaluation of Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement 2016;12:164–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.