Abstract

The unprecedented severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) pandemic has called for substantial investigations into the capacity of the human immune system to protect against reinfection and keep pace with the evolution of SARS-CoV-2. We evaluated the magnitude and durability of the SARS-CoV-2–specific antibody responses against parental WA-1 SARS-CoV-2 receptor-binding domain (RBD) and a representative variant of concern (VoC) RBD using antibodies from 2 antibody compartments: long-lived plasma cell–derived plasma antibodies and antibodies encoded by SARS-CoV-2–specific memory B cells (MBCs). Thirty-five participants naturally infected with SARS-CoV-2 were evaluated; although only 25 of 35 participants had VoC RBD–reactive plasma antibodies, 34 of 35 (97%) participants had VoC RBD–reactive MBC-derived antibodies. Our finding that 97% of previously infected individuals have MBCs specific for variant RBDs provides reason for optimism regarding the capacity of vaccination, prior infection, and/or both, to elicit immunity with the capacity to limit disease severity and transmission of VoCs as they arise and circulate.

Keywords: COVID-19, memory B-cell, variant of concern, limiting dilution assay, antibody, disease severity

Following natural infection, antibody responses vary significantly between individuals; however, memory B cells (MBCs) that recognize the receptor-binding domain of variants of concern were detected in 97% of participants, regardless of disease severity. These antibody and MBC responses further increased following mRNA vaccination.

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), the causative agent of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), emerged in 2019, resulting in 249 million cases and 5.03 million deaths worldwide (as of 5 November 2021). SARS-CoV-2 infection leads to illness ranging from asymptomatic to severe, requiring hospitalization, mechanical ventilation, and often leading to death [1]. SARS-CoV-2–specific antibodies are a likely correlate of immunity and are thought to protect against repeat infection [2], and antibody-mediated protection has been observed in humans, nonhuman primate studies, and in passive transfer of neutralizing antibodies [2–7]. However, SARS-CoV-2–specific serum antibodies decline in the months following natural infection or vaccination [3–7], and neutralizing antibody titers have been reported to be low in many convalescent, naturally infected individuals, with even lower titers against emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern (VoCs), calling into question both the durability and breadth of antibody-mediated protection against SARS-CoV-2 [4–8].

When they encounter their cognate antigen, B cells differentiate in peripheral lymph nodes, where they either become plasma cells that secrete pathogen-specific antibodies present in plasma or serum or become memory B cells (MBCs). Short-lived plasma cells/plasmablasts transiently secrete antibodies before undergoing apoptosis, while long-lived plasma cells (LLPCs) traffic to bone marrow and secrete antibodies for months to years postinfection [9], protecting against repeat infections with homologous or closely related pathogens. MBCs also differentiate in germinal centers and then circulate in low numbers in peripheral blood. They do not secrete antibodies, but instead survey the periphery for invading pathogens, poised to quickly respond by proliferating and differentiating into a new population of antibody-secreting plasma cells/plasmablasts upon repeat infection/vaccination. MBCs have been found to respond to antigenically diverse pathogens that evade preexisting plasma antibodies [10, 11]. Consequently, MBCs have the potential to play a critical role in developing host and herd immunity to SARS-CoV-2, especially in the face of waning antibody titers and the emergence of antigenic variants that differ from early-lineage SARS-CoV-2.

The emergence of specific Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)–defined [12] SARS-CoV-2 VoCs has led to concerns that some SARS-CoV-2 viruses may evolve to escape human antibody-mediated protection. These variants include Alpha (B.1.1.7), Beta (B.1.351), Gamma (P.1), and Delta (B.1.617.2). Mutations, particularly those in the receptor-binding domain (RBD) on the spike protein, have been shown to increase transmissibility through better binding to the host angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor [13, 14] as well as reduce antibody-mediated neutralization by human convalescent immune, COVID-19 vaccine sera [15–19] and therapeutic monoclonal antibodies [20]. While SARS-CoV-2–specific MBCs have recently been characterized [5, 8, 21–23], studies assessing functional binding of MBC-derived antibodies against VoCs have been limited. Such studies would answer the central question of whether the preexisting SARS-CoV-2–specific MBC antibody repertoire can recognize and quickly respond to VoC reinfection with an antibody milieu that can either protect against or mitigate severity of VoC infection.

To address this question, we undertook a longitudinal study to investigate the magnitude, durability, and breadth of antibody-mediated immune memory following SARS-CoV-2 infection. We recruited a cohort of 35 COVID-19 convalescent immune participants from 1 to 14 months postinfection, who tested positive early in the pandemic (March–July 2020), including 10 participants who were vaccinated following natural infection. These participants experienced a range of disease severity ranging from asymptomatic to severe disease. This work provides a framework to define and predict long-lived immunity to SARS-CoV-2 and emerging variants after natural infection and/or vaccination. We nonspecifically stimulated study participants peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) to become antibody-secreting cells [24, 25] and assessed MBC-derived antibody binding to SARS-CoV-2 early-lineage strain WA-1 RBD, the only strain circulating in Oregon until Alpha (B.1.1.7) was detected in December 2020, and a VoC RBD containing the K417N, E484K, and Y501N mutations present in currently circulating VoCs: Y501N is present in the Alpha, Beta, Gamma, and Delta variants and has been shown to increase transmission via enhanced binding to the ACE2 receptor [13]. E484K is present in 15% of strains circulating in the United States (CDC reporting 21 May 2021). K417N and E484K are present in the Beta and Gamma strains [13, 26, 27].

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Human Research Ethics

The study was reviewed and approved by the Oregon Health and Science University (OHSU) Institutional Review Board (IRB number 21230). Informed consent was obtained from participants on initiation of their participation in the study.

Human Subjects

Participants with polymerase chain reaction (PCR)–confirmed COVID-19 infection were approached as inpatients at OHSU hospital, through study recruitment letters sent out by the Oregon Health Authority, or PCR-positive individuals who visited occupational health at OHSU. All participants included in this study tested positive early in the pandemic, March–July 2020. Upon enrollment, a comprehensive medical history was taken in addition to serum, plasma, and PBMCs. When possible, 1 or more follow-up serial sample visits were arranged. Blood samples (n = 67) were collected from 35 convalescent participants with confirmed COVID-19 infection (OHSU IRB number 21230), between 1 and 14 months postinfection, as well as banked samples from 6 pre-2020 healthy controls. Forty milliliters of whole blood was collected for PBMCs and plasma (BD Vacutainer lavender top ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid tubes). Whole blood was centrifuged at 1000g for 10 minutes and the plasma fraction was collected and stored at –80°C until use. PBMCs were subsequently isolated using Sepmate tubes (Stemcell) spun at 800g for 20 minutes, rinsed, counted, aliquoted, and stored in liquid nitrogen until needed.

Human MBC Limiting Dilution Analysis

PBMCs were thawed and resuspended in RPMI 1640 (Gibco), 1× Anti-Anti (Corning), 1× non-essential amino acids (HyClone), 20 mM HEPES (Thermo Scientific), 50 μM β-mercaptoethanol, and 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (VWR). Cells were cultured in serial 2-fold diluted doses (10 wells per dose), starting with 3–5 × 105 PBMCs per well at the highest dose, in 96-well round-bottom plates in a final volume of 200 μL per well. Cells were incubated with 1000 U/mL IL-2 (Prospec) and 2.5 µg/mL R848 (InvivoGen) [25]. To determine background absorbance values, supernatants were used from 8 wells of unstimulated PBMCs only. Plates were incubated at 37°C and 5% CO2 for 7 days. Stimulation was determined by total immunoglobulin G (IgG) enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Antigen-specific MBC frequencies were calculated by assaying limiting dilution assay (LDA) supernatants by antigen-specific ELISA [24].

Antigen-Specific ELISA for Plasma and LDA

Ninety-six–well (plasma, Corning-3590) or half-well (LDA, Greiner Bio-one) ELISA plates were coated with 100 μL (plasma) or 50 µL (LDA) of 1 µg/mL antigen in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), recombinant RBD (provided by Dr David Johnson), recombinant spike subunit 1 (40 591-V08H, Sino Biological), and recombinant VoC RBD. Plates were incubated overnight at 4°C, washed with PBS-T (0.05% Tween) and blocked for 1 hour with 5% milk prepared in PBS-T. For plasma, samples were serially 3-fold diluted in dilution buffer and 100 µL was added to wells. Plates were incubated at room temperature for 1 hour. For LDA, following stimulation, 20 μL of LDA supernatants was added to each well and incubated at room temperature for 1 hour. Plates were washed 4 times with wash buffer, and 100 μL (plasma) or 50 μL (LDA) of 1:3000 dilution of antihuman IgG horseradish peroxidase (BD Pharmingen, 555 788) detection antibody was added and incubated at room temperature for 1 hour. Plates were washed 4 times with wash buffer, 100 μL (plasma) or 50 μL (LDA) of colorimetric detection reagent containing 0.4 mg/mL o-phenylenediamine and 0.01% hydrogen peroxide in 0.05 M citrate buffer (pH 5) were added, and the reaction was stopped after 20 minutes by the addition of 1 M HCl. Optical density (OD) at 492 nm was measured using a CLARIOstar ELISA plate reader. Plasma antibody endpoint titers were set as the lowest dilution with an OD 4-fold above PBS-only wells. LDA wells were scored positive at ODs at least 2-fold above background (unstimulated PBMC wells).

MBC Frequency

MBC precursor frequencies were calculated by the semi-logarithmic plot of the percentage of negative cultures vs the cell dose per culture, as previously described [24], and frequencies were calculated as the reciprocal of the cell dilution at which 37% of the cultures were negative for antigen-specific IgG production. Rows that yielded 0% negative wells were excluded, since this typically resides outside of the linear range of the curve and artificially reduced the MBC precursor frequency. For participants with low frequency of antigen-specific antibody-secreting cells, frequency was determined by number of positive wells divided by the total number of IgG-positive secreting wells, multiplied by 1 million, giving a frequency per million PBMCs stimulated.

Generation of VoC RBD and Protein Expression

To generate the triple mutant VoC RBD, we subjected the wild-type RBD encoding nucleotide sequence to site-directed mutagenesis to make the following changes: N501Y, E484K, K417N using Q5 site-directed mutagenesis kit (NEB). Purified SARS-CoV-2 VoC RBD protein was prepared as described previously [28, 29]. In brief, His-tagged VoC RBD bearing lentivirus was produced in HEK 293-T cells and used to infect HEK 293-F suspension cells. The suspension cells were allowed to grow for 3 days, shaking at 37°C, 8% CO2. Cells were centrifuged at 4000g for 10 minutes, supernatant collected, sterile filtered, and purified by Ni-NTA chromatography. The purified protein was then buffer-exchanged into PBS and concentrated.

Statistical Methods

Fisher exact test was used to calculate the P values in Table 1. Kruskal–Wallis nonparametric tests were used to compare groups based on disease severity. Samples from participants who were vaccinated prior to subsequent blood sample collections were included in the longitudinal data, but excluded from all statistical analysis. Paired t test was used to compare ELISA titers between RBD-WA-1 and RBD-VoC as well as used to compare log-transformed specific MBC frequencies against WA-1 and VoC RBD. Spearman rank-order correlation was performed for all correlation analysis. All analysis was done in GraphPad Prism version 9.1.1.

Table 1.

Summary of Coronavirus Disease 2019 Cohort Participant Demographics

| Hospitalized | Total (N = 35) | P Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (n = 7) | No (n = 28) | |||

| Age, y | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 66.9 (12.6) | 56.1 (13.1) | 58.2 (13.6) | .059 |

| Median (range) | 65.0 (54–86) | 57.5 (22–80) | 58 (22–86) | |

| Sex, No. (%) | ||||

| Female | 1 (14.3) | 14 (50.0) | 15 (42.9) | .20a |

| Male | 6 (85.7) | 14 (50.0) | 20 (57.1) | |

| Ethnicity, No. (%) | ||||

| Hispanic | 1 (14.3) | 0 (0) | 1 (2.9) | .20a |

| Non-Hispanic | 6 (86.7) | 28 (100.0) | 34 (97.1) | |

| Race, No. (%) | ||||

| White | 6 (85.7) | 27 (96.4) | 33 (94.3) | .36a |

| Pacific Islander | 0 (0) | 1 (3.6) | 1 (2.9) | 1.0a |

| Declined | 1 (14.3) | 0 (0) | 1 (2.9) | .20a |

| Recruitment population, No. (%) | ||||

| Inpatient OHSU | 3 (42.9) | 0 (0) | 3 (8.6) | <.01a |

| Oregon Health Authority | 4 (57.1) | 20 (71.4) | 24 (68.6) | .65a |

| Occupational Health | 0 (0) | 8 (28.6) | 8 (22.9) | .17a |

| Admitted to ICU, No. (%) | ||||

| Yes | 3 (42.9) | NA | 3 (8.6) | |

| No | 4 (57.1) | NA | 4 (11.4) | |

| Time to first draw postinfection, months | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 5.5 (3.4) | 5.5 (2.3) | 5.5 (2.5) | .99 |

| Median (range) | 6.6 (0.6–9.9) | 5.3 (1.5–13.5) | 5.9 (0.6–13.5) | |

Abbreviations: ICU, intensive care unit; NA, not applicable; OHSU, Oregon Health and Science University; SD, standard deviation.

Fisher exact test.

Univariate and Multivariable Analyses

We conducted univariate analyses with each predetermined clinical covariate of interest and MBC frequency was log transformed. Each univariate analysis was conducted as follows: age (continuous), age (categorical, <50 vs ≥50), disease severity (ordinal), disease severity (categorical, <5 vs ≥5), and hospitalization status (yes vs no). For multivariable models our first model included age (continuous), disease severity score (ordinal), and the interaction between age and disease severity. Contrast estimates were evaluated for each disease severity score interaction with age to determine if any effects within each score and mean age existed. Our second model included age, hospitalization status, and the interaction between hospitalization status and age. Student t test was used to compare mean S1-IgG MBC frequencies between paired samples and showed no significant difference (20 paired samples, P = .792); therefore, S1-IgG MBC frequency from the initial draw was used for both of the multivariable analysis models.

All analyses are based on the data for the first blood draw, since repeat draws were not available for all participants. Student t test was used to compare participants with 2 blood draws to determine if there was a significant difference in S1 MBC frequency between time points and it was not statistically significant (P < .05). All statistical analyses were performed in SAS version 9.4.

RESULTS

COVID-19 Cohort Population

Thirty-five SARS-CoV-2 PCR–positive participants were recruited in Oregon under an OHSU IRB–approved protocol (IRB number 21230) (Table 1). The participants included in this investigation tested positive early in the pandemic (March–July 2020). Time postinfection, defined by months post–PCR diagnosis, ranged from 1 to 14 months. World Health Organization disease severity scores [30] ranged from 1 (asymptomatic) to 6 (severe, requiring intubation and mechanical ventilation), with 2 asymptomatic participants, 26 symptomatic/not hospitalized participants, and 7 hospitalized participants. Forty-three percent of participants were female, and the median age of participants was 58 years (Table 1). Of the 35 participants, 10 were vaccinated before their final time point, providing comparator samples for vaccine-elicited boosting vs natural decay in unboosted participants.

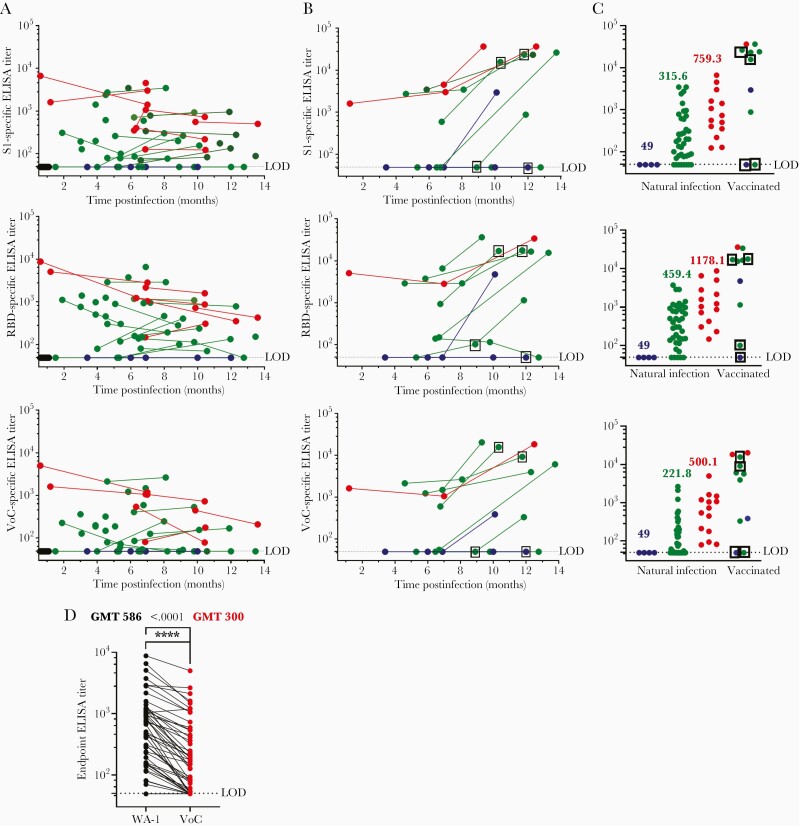

Magnitude, Durability, and Breadth of LLPC-Derived Antibodies

A total of 70 plasma samples were collected from 35 participants 21 or more days postinfection, with 26 participants providing multiple time points. Plasma antibody concentrations were assayed by IgG ELISA using wild-type WA-1 RBD and VoC RBD (Figure 1). Antibody ELISA titers were below our lower limit of detection for 2 asymptomatic study participants at 2 separate time points (Figure 1A and 1B) against full-length S1, RBD, and VoC RBD. All but 4 symptomatic nonhospitalized cases had detectable antibody titers by ELISA against parental WA-1 RBD, but 8 symptomatic participants had S1 ELISA titers at or below the limit of detection (at least 1 time point), and 10 participants fell below the limit of detection against VoC RBD (at least 1 time point) (Figure 1A). All of the hospitalized participants’ ELISA titers were above the limit of detection against S1, WA-1 RBD, and VoC RBD. Overall geometric mean ELISA titers across antigens were highest for the hospitalized participants (S1, 759; RBD, 1178; VoC, 500), with symptomatic, nonhospitalized participants having lower overall geometric mean ELISA titers vs S1 (315), WA-1 RBD (459), and VoC RBD (221) compared to hospitalized participants (Figure 1C) (P < .0001). Ten vaccinated participants are included in the longitudinal data (Figure 1B), 4 samples following a single dose of messenger RNA (mRNA) vaccine (boxed samples) and 7 samples following 2-dose mRNA vaccine series. Most samples showed a boost in ELISA titer postvaccination, with some achieving the highest ELISA titers against both RBDs in this study. The vaccines were excluded from statistical analyses. There was a significant 1.95-fold decrease in VoC ELISA geometric mean titers when compared to WA-1 (Figure 1D) across all convalescent samples analyzed.

Figure 1.

Plasma antibody titers over time, stratified by disease severity. A, Plasma enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) titers for pre-2020 plasma (black, n = 6), asymptomatic (blue, n = 4 from 2 participants), nonhospitalized (green, n = 39 from 26 participants), and hospitalized (red, n = 14 from 7 participants) samples. B, Plasma endpoint ELISA titer following messenger RNA vaccination. Boxed samples indicate draw after 1 dose (11–33 days post–first dose); other samples taken after second dose (16–72 days post–second dose). C, Magnitude of antibody responses, stratified by disease severity. Geometric mean titers are listed above each group. D, Comparison between ELISA titers against receptor-binding domain (RBD) WA-1 and variant of concern RBD. Samples from participants who received a vaccination prior to the second draw were excluded from the data analysis. Paired t test was performed indicating significant differences between the values (P < .0001); significance denoted by ∗∗∗∗. Limit of detection is set at 50; all samples below the limit of detection are assigned an arbitrary value of 49. Abbreviations: ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; GMT, geometric mean titer; LOD, limit of detection; RBD, receptor-binding domain; VoC, variant of concern.

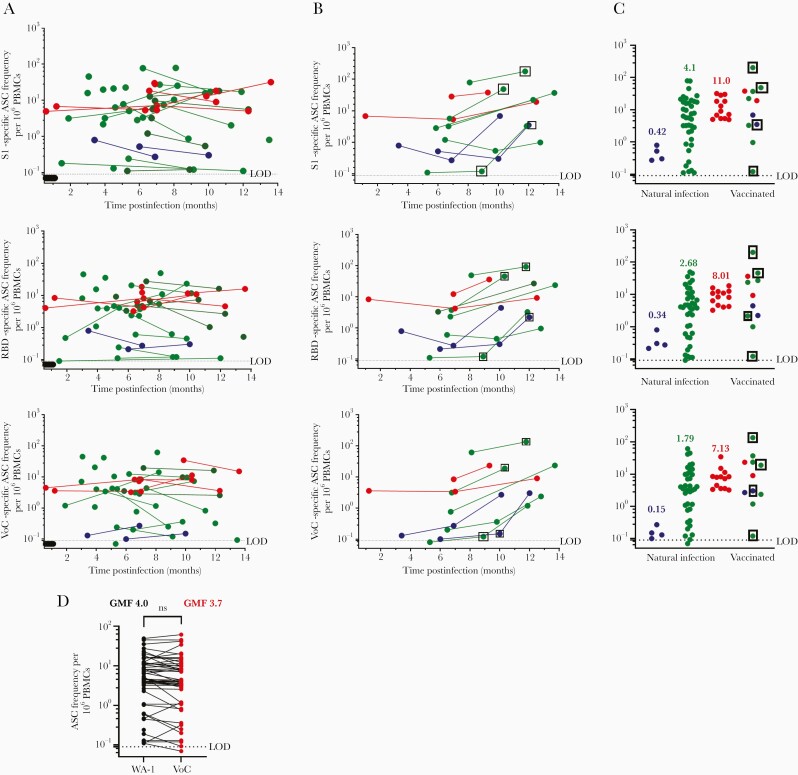

Detection of SARS-CoV-2–Specific MBC Frequency

Sixty-seven PBMC samples were collected from 35 participants, with 26 participants providing multiple time points. In contrast to plasma antibody titers, SARS-CoV-2 S1 and RBD-specific MBCs were present above the limit of detection in all participants in this analysis, even asymptomatic participants (Figure 2A). Moreover, SARS-CoV-2 S1 and RBD-specific MBCs remained detectable for as long as 14 months postinfection (Figure 2A). One subject had a VoC RBD MBC frequency below the limit of detection. Some participants experienced an increase in MBC frequency over time; this is consistent with previous reports of reactive germinal centers persistent for months following infection, leading to further affinity maturation over time in response to SARS-CoV-2 infection [5, 8, 31]. When stratified by disease severity, SARS-CoV-2–specific MBC frequencies were closely grouped within asymptomatic and hospitalized participants compared to nonhospitalized participants, whose frequencies spanned the entire range from asymptomatic to hospitalized (Figure 2C; P = .01). Ten vaccinated participants were included in Figure 2B, including 4 samples following a single dose of an mRNA vaccine (boxed samples) and 7 samples following a 2-dose mRNA vaccine series. Most participants showed evidence of postvaccination boost and had high overall SARS-CoV-2–specific MBC frequencies. In contrast to LLPC-derived antibodies RBD-WA-1 and RBD-VoC, MBC-derived antibodies showed little variability in their ability to recognize RBD-WA-1 vs RBD-VoC (Figure 2D), with no significant difference detected between groups.

Figure 2.

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2)–specific memory B-cell (MBC) frequency over time and stratified by disease severity. A, MBC SARS CoV-2–specific frequency for pre-2020 (black, n = 6), asymptomatic (blue, n = 4 from 2 participants), nonhospitalized (green, n = 39 from 26 participants), and hospitalized (red, n = 13 from 7 participants) samples. B, MBC frequency following messenger RNA vaccination. Boxed samples indicate draw after 1 dose (11–33 days post–first dose); other samples taken after second dose (16–72 days post–second dose). C, Magnitude of MBC frequencies, stratified by disease severity. Geometric mean frequencies are listed above each group. D, Comparison between receptor-binding domain (RBD)–specific MBC frequency against WA-1 RBD and variant of concern (VoC) RBD. t test of log-transformed data, with no statistically significant difference between WA-1 and VoC MBC antibody binding. Limit of detection is set at 0.1; all samples below the limit of detection are assigned an arbitrary value of 0.07. Abbreviations: ASC, antibody-secreting cell; GMF, geometric mean frequency; LOD, limit of detection; ns, not significant; PBMCs, peripheral blood mononuclear cells; RBD, receptor-binding domain; VoC, variant of concern.

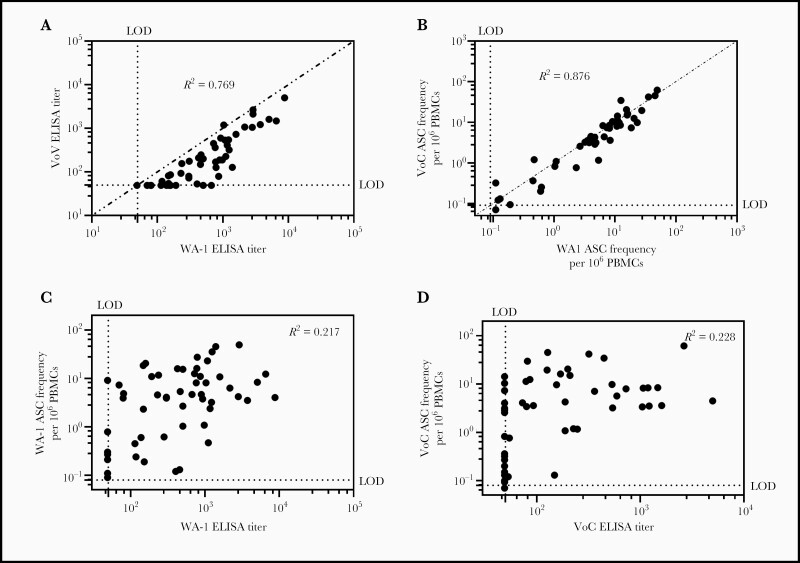

Relationship Between WA-1 and VoC IgG ELISA Titer and MBC Frequency

We next examined the relationship between RBD-WA-1–specific plasma antibodies and RBD-VoC–specific plasma antibodies. We observed a strong linear correlation between WA-1 and VoC RBD–specific antibodies (Spearman correlation coefficient [R2] = 0.769; P < .0001), with ELISA titers against RBD-VoC approximately 2-fold lower than RBD-WA-1 across all participants (Figure 1D); WA-1 and VoC RBD–specific MBC frequencies were also strongly correlated as well (R2 = 0.876; P < .0001), with some samples exhibiting lower frequency to VoC RBD, but many exhibiting a nearly 1:1 ratio between both WA-1 and VoC RBDs (Figure 3B). Finally, we noted a much weaker relationship between WA-1 or VoC RBD–specific ELISA titers and WA-1–specific (R2 = 0.217; P = .0003) and VoC (R2 = 0.228; P = .0004) MBC frequency (Figure 3C and 3D).

Figure 3.

The relationship between WA-1 and variant of concern (VoC) antibody binding and memory B-cell (MBC) frequency as well as the relationship between long-lived plasma cell–derived antibody titers and MBC frequency for each antigen. A, Correlation between VoC and WA-1 receptor-binding domain (RBD)–specific enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) titers. Spearman correlation coefficient (R2) = 0.769; P < .0001. B, Correlation between RBD-VoC and RBD-WA-1–specific MBC frequency. Dotted line signifies line of identity. Spearman correlation coefficient (R2) = 0.876; P < .0001. C, Correlation between WA-1 RBD MBC frequency and ELISA titer (R2 = 0.217) and between VoC RBD MBC frequency and ELISA titer (R2 = 0.228). Abbreviations: ASC, antibody-secreting cell; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; LOD, limit of detection; PBMCs, peripheral blood mononuclear cells; VoC, variant of concern.

Relationship Between Clinical/Disease Severity and MBC Frequency

We tested the relationship between reported symptoms and hospitalization status using Fisher exact test (Supplementary Table 1). Differences in MBC frequency were tested individually with age, clinical score, and hospitalization status using analysis of variance and simple linear regression models, with no significant findings (Supplementary Table 2). To complete this evaluation, we then analyzed 2 multivariable models testing the relationship between age and clinical score and MBC frequency. When including an interaction term between age and clinical score, there was no significant relationship (P = .204; Supplementary Table 3). Because the distribution of ordinal clinical scores was largely determined by hospitalization status, we revised the model to test the relationship between age, hospitalization status, and MBC frequency, again including an interaction term for age and hospitalization status, and again finding no significant relationship (P = .114).

DISCUSSION

Breakthrough infections and the emergence of VoCs highlight the limitations of SARS-CoV-2 S–specific plasma antibodies alone to recognize and protect against VoCs, and work by our group and others [15, 20, 32, 33] has shown that serum or plasma antibodies elicited by natural infection have reduced neutralization potency against several VoCs. However, serologic studies do not capture the antibodies that will be secreted by MBCs when they are stimulated, expand, and differentiate into a new population of antibody-secreting cells on repeat infection. Here we characterized the SARS-CoV-2–specific MBC-derived antibodies, with 3 critical findings: (1) SARS-CoV-2 RBD–specific MBCs can be detected in asymptomatic, seronegative, PCR-positive participants; (2) MBC populations elicited following primary infection appear relatively stable over time, up to 1 year postinfection; and (3) in contrast to plasma antibodies, the antibodies these MBCs are programmed to secrete recognize both parental and VoC RBDs at roughly equivalent frequencies. These results are consistent with MBC studies of other pathogens that show MBCs retain pathogen-specific antibody diversity that is different from LLPC-derived antibodies [10, 11, 34]. Because of this additional line of antibody defense latent in SARS-CoV-2–specific MBCs, we contend there is reason for optimism regarding the capacity of vaccination, prior infection, and/or both, to limit disease severity and transmission of VoCs as they inevitably emerge in the setting of ongoing transmission. The observation that the high ELISA titers were seen in previously infected participants who got vaccinated suggests that vaccines may be particularly effective in previously infected persons; this has been shown previously [35].

While SARS-CoV-2–specific antibodies were detected in 66% of all samples tested and not detected in either of the 2 asymptomatic participants in our study, SARS-CoV-2–specific MBCs were detectable in the peripheral blood of all participants, including asymptomatic participants. This result supports a recent finding that SARS-CoV-2–specific MBCs are present in the peripheral blood of participants with no detectable SARS-CoV-2 serum antibodies [36–39]. In this study, SARS-CoV-2–specific MBC frequency remained stable over time, sometimes even increasing, consistent with other reports [5, 8, 31] and consistent with evidence of extended germinal center activity that remains long after viral clearance, resulting in an increase of MBC frequency as well as an increase in diverse, high-affinity MBCs. As with plasma antibodies, we observed an increase in MBC frequency with an increase in disease severity. We hypothesize that higher and more prolonged antigen load associated with more serious illness correlates with higher antibody titers, similar to what has been shown in Middle East respiratory syndrome [40] as well as in SARS-CoV-2 human cohorts [41].

Study limitations include a small number of asymptomatic and hospitalized patients from whom only a subset of longitudinal samples could be collected. Moreover, our LDA approach screened antibodies specific only for S1, RBD, and a specific set of known variant mutations in the RBD, while there are VoC-associated mutations outside of RBD. Nevertheless, RBD has been widely identified as the most important region for neutralizing antibody epitopes, and although there are likely to be additional RBD mutations that emerge in the future, the principle that MBC-derived antibody diversity extends beyond that seen in circulating antibodies is likely to hold. As more subject antibody responses are studied, more nuanced patterns than those reported here may emerge. Finally, this study evaluates the specificity of plasma IgG and IgG-secreting MBCs. As SARS-CoV-2 is a respiratory pathogen, we expect that immunoglobulin A (IgA) and MBCs programmed to secrete IgA may also play a role in protection against the variants. Additional studies that address these limitations are critically needed to further our understanding of the multifaceted roles that antibodies continue to play in controlling the COVID-19 pandemic.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at The Journal of Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Notes

Financial support. This work was supported in part by federal funds from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases NIAID 1R01AI145835 (WBM), by the Oregon National Primate Research Center grant, 8P51 OD011092 (MKS) and a pilot project grant from the OHSU Foundation (MKS), and Oregon Health & Science University Innovative IDEA grant 1018784 (FGT).

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: No reported conflicts of interest.

All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1. Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet 2020; 395:497–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rydyznski Moderbacher C, Ramirez SI, Dan JM, et al. Antigen-specific adaptive immunity to SARS-CoV-2 in acute COVID-19 and associations with age and disease severity. Cell 2020; 183:996–1012.e19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sette A, Crotty S.. Adaptive immunity to SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19. Cell 2021; 184:861–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zost SJ, Gilchuk P, Chen RE, et al. Rapid isolation and profiling of a diverse panel of human monoclonal antibodies targeting the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. Nat Med 2020; 26:1422–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gaebler C, Wang Z, Lorenzi JCC, et al. Evolution of antibody immunity to SARS-CoV-2. Nature 2021; 591:639–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rudberg A-S, Havervall S, Månberg A, et al. SARS-CoV-2 exposure, symptoms and seroprevalence in health care workers. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Madariaga MLL, Guthmiller JJ, Schrantz S, et al. Clinical predictors of donor antibody titre and correlation with recipient antibody response in a COVID-19 convalescent plasma clinical trial. J Intern Med 2020; 289:559–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dan JM, Mateus J, Kato Y, et al. Immunological memory to SARS-CoV-2 assessed for up to 8 months after infection. Science 2021; 371:eabf4063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Slifka MK, Antia R, Whitmire JK, Ahmed R.. Humoral immunity due to long-lived plasma cells. Immunity 1998; 8:363–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Purtha WE, Tedder TF, Johnson S, et al. Memory B cells, but not long-lived plasma cells, possess antigen specificities for viral escape mutants. Exp Med 2011; 208:2599–606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wong R, Belk JA, Govero J, et al. Affinity-restricted memory B cells dominate recall responses to heterologous flaviviruses. Immunity 2020; 53:1078–94.e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Galloway SE, Paul P, MacCannell DR, et al. Emergence of SARS-CoV-2 B.1.1.7 lineage—United States, December 29, 2020–January 12, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2021; 70:95–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Davies NG, Abbott S, Barnard RC, et al. Estimated transmissibility and impact of SARS-CoV-2 lineage B.1.1.7 in England. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tegally H, Wilkinson E, Giovanetti M, et al. Detection of a SARS-CoV-2 variant of concern in South Africa. Nature 2021; 592:438–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bates TA, Leier HC, Lyski ZL, et al. Neutralization of SARS-CoV-2 variants by convalescent and vaccinated serum. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wang Z, Schmidt F, Weisblum Y, et al. mRNA vaccine-elicited antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 and circulating variants. bioRxiv [Preprint]. Posted online 30 January 2021. doi: 10.1101/2021.01.15.426911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hajjo R, Sabbah DA, Bardaweel SK.. Emerging SARS-CoV-2 lineages in Middle Eastern Jordan with increasing mutations near antibody recognition sites. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Stamatatos L, Czartoski J, Wan Y-H, et al. Antibodies elicited by SARS-CoV-2 infection and boosted by vaccination neutralize an emerging variant and SARS-CoV-1. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cele S, Gazy I, Jackson L, et al. Escape of SARS-CoV-2 501Y.V2 variants from neutralization by convalescent plasma. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chen RE, Zhang X, Case JB, et al. Resistance of SARS-CoV-2 variants to neutralization by monoclonal and serum-derived polyclonal antibodies. Nat Med 2021; 27:717–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hartley GE, Edwards ESJ, Aui PM, et al. Rapid generation of durable B cell memory to SARS-CoV-2 spike and nucleocapsid proteins in COVID-19 and convalescence. Sci Immuno 2020; 5:eabf8891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sokal A, Chappert P, Barba-Spaeth G, et al. Maturation and persistence of the anti-SARS-CoV-2 memory B cell response. Cell 2021; 184:1201–13.e14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Cohen KW, Linderman SL, Moodie Z, et al. Longitudinal analysis shows durable and broad immune memory after SARS-CoV-2 infection with persisting antibody responses and memory B and T cells. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Amanna IJ, Slifka MK.. Quantitation of rare memory B cell populations by two independent and complementary approaches. J Immuno Methods 2006; 317:175–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Pinna D, Corti D, Jarrossay D, Sallusto F, Lanzavecchia A.. Clonal dissection of the human memory B-cell repertoire following infection and vaccination. Eur J Immunol 2009; 39:1260–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Jangra S, Ye C, Rathnasinghe R, et al. SARS-CoV-2 spike E484K mutation reduces antibody neutralisation. Lancet Microbe 2021; 2:e283–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wang P, Nair MS, Liu L, et al. Antibody resistance of SARS-CoV-2 variants B.1.351 and B.1.1.7. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Stadlbauer D, Amanat F, Chromikova V, et al. SARS-CoV-2 seroconversion in humans: a detailed protocol for a serological assay, antigen production, and test setup. Curr Protoc Microbiol 2020; 57:e100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bates TA, Weinstein JB, Farley SE, Leier HC, Messer WB, Tafesse FG.. Cross-reactivity of SARS-CoV structural protein antibodies against SARS-CoV-2. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. World Health Organization. Novel coronavirus COVID-19 therapeutic trial synopsis, R&D blue print. 2020. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/covid-19-therapeutic-trial-synopsis. Accessed 8 June 2021.

- 31. Rodda LB, Netland J, Shehata L, et al. Functional SARS-CoV-2-specific immune memory persists after mild COVID-19. Cell 2021; 184:169–83.e17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wibmer CK, Ayres F, Hermanus T, et al. SARS-CoV-2 501Y.V2 escapes neutralization by South African COVID-19 donor plasma. Nat Med 2021; 27:622–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Faulkner N, Ng KW, Wu M, et al. Reduced antibody cross-reactivity following infection with B.1.1.7 than with parental SARS-CoV-2 strains. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wec AZ, Haslwanter D, Abdiche YN, et al. Longitudinal dynamics of the human B cell response to the yellow fever 17D vaccine. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2020; 117:6675–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Leier HC, Bates TA, Lyski ZL, et al. Previously infected vaccinees broadly neutralize SARS-CoV-2 variants. medRxiv [Preprint]. Posted online 29 April 2021. doi: 10.1101/2021.04.25.21256049. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Winklmeier S, Eisenhut K, Taskin D, et al. Persistence of functional memory B cells recognizing SARS-CoV-2 variants despite loss of specific IgG. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Marklund E, Leach S, Axelsson H, et al. Serum-IgG responses to SARS-CoV-2 after mild and severe COVID-19 infection and analysis of IgG non-responders. PLoS One 2020; 15:e0241104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Oved K, Olmer L, Shemer-Avni Y, et al. Multi-center nationwide comparison of seven serology assays reveals a SARS-CoV-2 non-responding seronegative subpopulation. EClinicalMedicine 2020; 29–30:100651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bilich T, Nelde A, Heitmann JS, et al. T cell and antibody kinetics delineate SARS-CoV-2 peptides mediating long-term immune responses in COVID-19 convalescent individuals. Sci Transl Med 2021; 13:abf7517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sariol A, Perlman S.. Lessons for COVID-19 immunity from other coronavirus infections. Immunity 2020; 53:248–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Robbiani DF, Gaebler C, Muecksch F, et al. Convergent antibody responses to SARS-CoV-2 in convalescent individuals. Nature 2020; 584:437–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.