Abstract

We examined a conceptual model for the associations of prenatal exposure to tobacco (PTE) and marijuana with child reactivity/regulation at 16 months of age. We hypothesized that PTE would be associated with autonomic reactivity and regulation that these associations would be indirect via maternal anger/hostility, depression/stress, or harsh parenting assessed at 2 months and that these effects would be most pronounced among children exposed to both tobacco and marijuana (PTME). Participants were 247 dyads (81 PTE, 97 PTME, and 69 nonexposed) who were followed up at 2 (N = 247) and 16 months (N = 238) of child age. Results from model testing indicated an indirect association between PTME and autonomic functioning during the second year of life, which was mediated by harsh parenting during caregiver–infant interactions. This study fills an important gap in the literature on PTE, PTME, and autonomic regulation during the toddler years, highlighting the role of maternal parenting as important intervening variables.

Keywords: autonomic reactivity/regulation, maternal psychopathology, prenatal marijuana exposure, prenatal tobacco exposure, respiratory sinus arrhythmia

1 |. INTRODUCTION

The prenatal period is a time of enhanced vulnerability during which substance exposures and comorbid risks may have long-term effects on development through a biological mechanism such as alteration of the epigenome, an idea that has been termed the “fetal origins hypothesis” (Almond & Currie, 2011). In fact, a large body of literature has examined the association between maternal substance use, including cigarettes, during pregnancy, and child development. However, many of these studies are methodologically flawed with poor control for demographic differences between substance using and comparison women, reliance on retrospective data, the use of single-item measures to assess substance use during pregnancy, and failure to use biochemical verification of substance use. Moreover, although prenatal tobacco exposure (PTE) is often used together with marijuana (PTME), the combined effect of PTME has seldom been examined. The majority of these studies also treat psychological symptoms during pregnancy as covariates rather than as cooccurring risks for child outcomes. This is a significant gap in the literature given the fact that pregnant smokers report high levels of perceived stress and more symptoms of depression and anger (Allen, Prince, & Dietz, 2009).

The purpose of this study was to examine pathways from maternal stress, depression, and anger during pregnancy, and maternal use of tobacco and marijuana to child autonomic reactivity and regulation. In addition to tobacco exposure, we examined the joint effect of tobacco and marijuana use and comorbid prenatal psychological symptoms. We tested a conceptual model that included pathways to physiological reactivity and regulation during later infancy via parenting and maternal psychological symptomatology in early infancy. We employed a prospective design beginning in the first trimester of pregnancy with multiple measures of substance use including biochemical verification and a demographically similar control group to address methodological limitations in existing studies.

1.1 |. Autonomic reactivity and regulation

There is robust evidence of the association between PTE and arousal dysregulation (USDHHS, 2014, review) and a growing body of evidence linking prenatal marijuana exposure (PME) to arousal dysregulation, including exaggerated startle responses and poor habituation to novel stimuli in infants (Jutras-Aswad, DiNieri, Harkany, & Hurd, 2009; Richardson, Day, & Goldschmidt, 1995). There are both direct and indirect mechanisms by which marijuana and tobacco may contribute to arousal dysregulation. Nicotine and marijuana both readily cross the placental barrier becoming concentrated in the fetal tissue (Hurd et al., 2005; Lambers & Clark, 1996). Nicotine restricts blood flow to the fetus due to vasoconstrictive effects of catecholamines associated with nicotine activation and also interacts with nicotinic acethylcholine receptors which are present early on in fetal brain development (Lambers & Clark, 1996; Lichtensteiger, Ribary, Schiumpf, Odermatt, & Widemer, 1988; Slotkin, 1992). In particular, PTE has been associated with both morphological and functional alterations in the fetal brainstem in both animals and human studies (e.g., Lavezzi, Ottaviani, & Matturri, 2005; Lichtensteiger et al., 1988; Slotkin, Orband-Miller, Queen, Whitmore, & Seidler, 1987), the portion of the brain that is instrumental for autonomic regulation. The neural pathway from PME to fetal brain development is less well understand but PME does alter the endocannabinoid system (Harkany et al., 2007) which is present early in fetal development and plays a major role in fetal brain development (Fernandez-Ruiz, Berrendero, Hernandez, & Ramos, 2000).

The importance of individual differences in reactivity and regulation has been highlighted in the psychobiological model of temperament which defines temperament as biologically based individual differences in reactivity and regulation (Rothbart & Bates, 2006). Thus, one particularly useful measure of regulation is respiratory sinus arrhythmia (RSA) which is a measure of the higher frequency portion of heart rate variability that occurs within the frequency range at which respiratory occurs (Porges, Doussard-Roosevelt, Portales, & Greenspan, 1996). RSA is widely believed to be a physiological correlate of emotion regulation that reflects parasympathetic dominance over cardiac functioning in the autonomic nervous system (ANS: Beauchaine, 2001). Baseline RSA (BRSA), which is a measure of the child’s ability to maintain physiological homeostasis during periods of minimal external stimulation, is one commonly used index of autonomic regulation (Porges, 1996). A second measure of RSA quantifies changes in RSA during environmental demands (Bornstein & Suess, 2000; Calkins, 1997). When an infant or toddler faces environmental demands, the myelinated vagal system optimally responds by applying a “brake” to regulate cardiac output (Porges et al., 1996) such that RSA is suppressed during stressful situations. This suppression of RSA allows heart rate to increase and the child to meet environmental demands. Thus, greater suppression during environmental challenge is believed to be indicative of a more adaptive physiological system which facilitates the ability of infants and toddlers to modulate their behavioral response to environmental challenge. RSA suppression is associated with more optimal state regulation in infancy (Brooker & Buss, ; DeGangi, DiPietro, Greenspan, & Porges, 1991), decreased behavior problems in preschool-aged children (Porges et al., 1996), and more adaptive behavior during attention and affect eliciting tasks in both preschool-aged children (Calkins, 1997; Suess, Porges, & Plude, 1994). Individual differences in autonomic regulation may reflect the impact of a wide range of developmental influences, including prenatal influences.

1.2 |. Prenatal tobacco and marijuana exposure

Among these prenatal influences, maternal use of various substances is a potent and primary risk factor for poor fetal development, with cigarettes being one of the most commonly used substances throughout pregnancy, especially among young, low-income women with low education (USDHHS, 2014, review). Despite concerted efforts to increase awareness of the dangers of smoking during pregnancy for both the mother and child, recent data from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health in the United States indicates that 15.9% of pregnant women continue to smoke during pregnancy (Substance Abuse & Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA], 2013). Approximately 24%–30% of pregnant women who smoke during pregnancy also report using marijuana (SAMHSA, 2013), with this number likely to rise with increasing marijuana legalization in many states.

1.3 |. Maternal depression/stress and anger/hostility

Substance use during pregnancy is a marker for a number of related risk factors that may also be important predictors of infant regulation (Mark, Desai, & Terplan, 2016; Massey et al., 2016). For example, mothers who continue to use substances during pregnancy are more likely to be stressed or depressed (Ludman et al., 2000; Mark et al., 2016; Massey et al., 2016) and have higher symptoms of anger and hostility (Eiden et al., 2011; Schuetze, Lopez, Granger, & Eiden, 2008). Theoretically, the neurobiological model of regulation suggests that mother–infant coregulation mediates the association between brainstem dysfunction due to pre- and perinatal risks and child self-regulation (Geva & Feldstein, 2008). Mother–infant coregulation may be jeopardized in the context of maternal anger and stress, thus leading to poor infant regulation. Continuity in these maternal experiences from prenatal to the postnatal period in the context of prenatal substance exposure may also exacerbate risk for poor regulation due to increasing allostatic load (McEwen, 2000). Indeed, empirical evidence from both animal and human studies indicates that maternal stress during pregnancy (e.g., Davis, Glynn, Waffarn, & Sandman, 2011; Kapoor, Petropoulos, & Matthews, 2008) and in the postnatal period disrupts the development of regulatory behavior in the exposed offspring (Sidor, Fischer, Eickhorst, & Cierpka, 2013). In addition to stress, studies indicate that cigarette smoking is positively associated with hostility, characterized by negative attitudes and beliefs toward other people and frequent, intense bouts of anger, and aggression (Miller, Smith, Turner, Guijarro, & Hallet, 1996). Trait hostility consistently predicts higher smoking rates in both men and women (e.g., Whiteman, Fowkes, Deary, & Lee, 1997). Although, to date, levels of anger have not been directly examined among pregnant marijuana users, marijuana users have been reported to have higher levels of hostility while under the influence of marijuana, or in their same day and next day behavior (Ansell, Laws, Roche, & Sinha, 2015; Smith, Homish, Leonard, & Collins, 2013). Furthermore, in a study of school-aged children who were exposed to alcohol, marijuana and/or tobacco, scores of maternal hostility predicted measures of attention (Leech, Richardson, Goldschmidt, & Day, 1999). Maternal hostility and harshness have been associated with externalizing behaviors and poor self-regulation in young children (Bradley & Corwyn, 2007; Velders et al., 2011). Thus, the relationship between prenatal risks and infant reactivity and regulation may also be mediated by maternal experiences of stress and anger during and after pregnancy.

1.4 |. Role of parenting as a mediator

One of the most significant environmental influences on managing stress and/or arousal in infancy is the quality of mother–infant interactions (Blair, Granger, Willoughby, & Kivlighan, 2006). In fact, the role of parenting behavior in the development of regulation has been discussed extensively in the broader developmental literature (Calkins & Hill, 2007; Eisenberg, Spinrad, & Morris, 2011; Kochanska & Thompson, 1997). A number of parenting dimensions have been implicated as being critical for the development of optimal self-regulation. However, one of the most critical aspects of parenting that has long been known to have a detrimental impact on regulatory processes is maternal power assertion, negativity, or harshness in the context of mother–child interactions (Kochanska & Knaack, 2003; Maccoby & Martin, 1983). For example, higher levels of maternal harshness/insensitivity have been associated with negative child outcomes including poor self-regulation in young children (Bradley & Corwyn, 2007). Thus, the relationship between prenatal risks and autonomic reactivity and regulation may be explained, at least in part, by levels of maternal harshness during mother–infant interactions.

1.5 |. Current study

The first goal of this study was to explore the associations between PTE, PTME, and the mediating (maternal depression/stress, anger/hostility, and parenting) and autonomic regulation variables. Developmentally, the ANS is experiencing rapid change during the first year of life. Longitudinal studies have demonstrated increases in RSA during the first six months of life which gradually taper during the second half of the first year (Fracasso, Porges, Lamb, & Rosenberg, 1994; Izard et al., 1991). Thus, we examined measures of autonomic regulation at 16 months of age, a point in time when developmental rates of RSA have stabilized. Given the strong and consistent effects of alcohol on the outcomes of interest, we excluded heavy drinkers at recruitment. Thus, although we examined alcohol effects on toddler outcomes, given restricted variability, we did not expect that in this sample, alcohol would pay a major role. We then examined a conceptual model for the examining the associations between PTE, PTME, and toddler autonomic regulation. We hypothesized that PTE would be associated with autonomic regulation/reactivity at 16 months of age and that these associations would be indirect via maternal anger/hostility, depression/stress or harsh parenting assessed at 2 months. Furthermore, we hypothesized that the effects would be more pronounced among toddlers with both PTE and PME. Thus, we tested an a priori model that included these measures of maternal psychopathology and parenting as intervening variables between PTE, PME, and infant regulation.

2 |. METHOD

2.1 |. Procedure

Informed written consent was obtained from interested, eligible women at their first laboratory visit. Prenatal assessments were conducted once in each trimester of pregnancy, and postnatal assessments occurred at 2, 9, and 16 months of infant ages, at age corrected for prematurity. The study (study name removed for blinded review) protocol #03RIAR3 was approved by (removed for blinded review). Participants were informed that data confidentiality was protected by a Federal Certificate of Confidentiality issued by the National Institute on Drug Abuse. Participants received compensation for completed assessments at all visits.

2.2 |. Sample selection

Women who presented for care at a large urban hospital’s prenatal clinic were screened during their first prenatal appointment. Eligible women were invited to participate in an ongoing longitudinal study of maternal health and child development. Initial exclusionary criteria included: more than 20 weeks gestation, maternal age of less than 18 years, and expected multiple births. Additional eligibility criteria were: no illicit drug use (other than marijuana based on maternal self-reports, salivary assays in each trimester, and infant meconium assays), and no heavy alcohol use (more than 1 drink/day on average or 4 drinks on one occasion based on maternal self-reports on a calendar-based interview) after pregnancy recognition, and primary language English. Because, as described above, maternal smoking during pregnancy is a marker for numerous other risk factors, we based our recruitment on the presence of maternal smoking during pregnancy. For all smokers, tobacco was used in the form of cigarettes.

At the end of each recruitment month, the closest matching nonsmoker (based upon age and education) was invited to participate. Cigarette smokers were oversampled so that one nonsmoker was recruited for every two smokers (taking the average of age and education of both). Participants included 258 mother–infant dyads. One dyad was dropped from analyses because infant meconium was positive for methamphetamine, two were dropped due to hydrocephaly, one was dropped because of a later diagnosis of autism, one because of binge drinking during pregnancy, four because of maternal diagnosis of bipolar disorder, one because of loss of custody, and one was excluded due to low maternal cognitive functioning, resulting in a final sample size of 247 infants. Of these dyads, 81 were PTE, 97 were PTME, and 69 were not exposed to tobacco or marijuana.

Maternal age ranged from 18 to 39 years at the time of their first appointment (M = 24.01, SD = 4.96). The women in the sample were 52% African American, 30% Caucasian, 18% Hispanic, and 8% other or mixed race, with several identifying as more than one race. Forty-five percent of the expectant mothers were married or living with their partner, 33% were in a relationship, but not living with their partner, 21% were single, and 1% were divorced. Twenty-nine percent of women had less than a high school education, 29% completed high school, 29% completed some college, 9% had a vocational/technical or associates degree, and 4% had a bachelor’s degree. Thus, the sample was largely comprised of single minority women with a high school diploma or less.

2.3 |. Maternal prenatal substance use

Maternal pregnancy smoking status was determined through a combination of self-report and maternal saliva sample results obtained once in each trimester of pregnancy and meconium testing. At each prenatal interview, the Timeline Follow-Back Interview (TLFB; Sobell & Sobell, 1995) was used to gather daily tobacco, alcohol, and marijuana use for the previous 3 months. Participants were provided a calendar and asked to identify events of personal interest (e.g., holidays, birthdays, vacations) as anchor points to aid recall. The method has been established as a reliable and valid method of obtaining data on substance use patterns including cigarettes, has good test–retest reliability, and is highly correlated with other intensive self-report measures (Brown et al., 1998). The TLFB also assessed postnatal maternal substance use at each postpartum visit (2 and 9 months of infant age) to assess postnatal substance use. The TLFB yielded data on average number of cigarettes smoked per day, average number of drinks per day, and average number of marijuana joints per day during each trimester. Mothers who smoked marijuana in the form of blunts (rolled in tobacco paper) were asked about the number of joints they could roll with the amount of marijuana in each blunt, in order to have a measure of number of joints per day for all women who used marijuana.

Maternal saliva was collected at each prenatal interview to provide objective evidence of recent exposure. The saliva specimens were analyzed by the US Drug Testing Laboratory (Des Plaines, IL) for Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), the psychoactive component of marijuana, by immunoassay screening (4.0 μg/L cutoff) and GC–MS confirmation (4.0 μg/L cutoff). Cotinine, the primary metabolite of nicotine, was assayed with ELISA or liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (LC–MS/MS), and a 10 μg/L cutoff was used for both assay methods (Jarvis et al., 2003). Maternal salivary cotinine ranged from 0 to 569 μg/L saliva.

After birth, meconium specimens were collected from soiled diapers twice daily until the appearance of milk stool, transferred to storage containers, and frozen until transport to the National Institute on Drug Abuse for analysis. Meconium specimens were assayed with a validated LC–MS/MS method (Gray et al., 2010a) for the concentrations of nicotine, cotinine, and trans-3-hydroxycotinine (OHCOT) as evidence of fetal nicotine exposure (Gray et al., 2010a). Meconium samples were also assayed with a validated two-dimensional GC–MS method for THC, 8β, 11-dihydroxy-THC, 11-nor-9-carboxy-THC, and cannabinol (Gray et al., 2010b). Mother–infant dyads were assigned to the PTE group if they reported smoking cigarettes after conception on the TLFB, if they had salivary cotinine levels greater than 10 μg/L in any trimester of pregnancy, and if the infants had any tobacco marker in their meconium. Mother–infant dyads were assigned to the PME if they reported smoking marijuana after conception on the TLFB, if they had salivary THC concentrations greater than 4.0 μg/L in any trimester of pregnancy, or if the infants had any marijuana metabolites in their meconium.

2.4 |. Parenting

Harsh parenting was assessed using behavioral observation during a mother–infant feeding interaction during early infancy. Mothers were asked to feed their infants as they normally would at home. These interactions were coded by blind coders using a collection of global 5-point rating scales developed by Clark (1999). A composite scale for harsh parenting was created from four items (expressed negative affect, angry/hostile mood, depressed/withdrawn mood, and displeasure/disapproval/criticism), with higher scores indicating more harshness. These behaviors were coded on the basis of maternal vocalizations, tone of voice, facial expressions, and behaviors toward the infant following the details in the coding manual provided by Clark (1999). This composite scale had high internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.84). Inter-rater reliability for maternal harshness was conducted on a random selection of 13% of dyads(n = 33), with an intraclass correlation coefficient of 0.72.

2.5 |. Maternal anger/hostility

Symptoms of maternal anger and hostility were measured using the anger and hostility subscales of the Buss-Perry Aggression Questionnaire (BPAQ; Buss & Perry, 1992), which was administered during the third trimester and at the 2-month laboratory visit. High scores indicate higher anger or hostility. Reliabilities for the two scales ranged from 0.78 to 0.85 at both time points.

2.6 |. Maternal depression/stress

Perceived stress was assessed during the second and third trimesters at and the 2-month laboratory visit using the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS; Cohen, Kamarck, & Mermelstein, 1983), a global measure of the level of stress experienced in the last month consisting of 14 items. The PSS items assess the degree to which respondents find their lives unpredictable, uncontrollable, and overwhelming. Respondents rate how often a particular thought/feeling occurred in the last month on a 5-point scale ranging from “never” to “very often.” Respondents report the prevalence of an item within the last month on a 5-point scale, ranging from never to very often. Reliability of the scale was good, α = 0.81 and α = 0.83 for the second and third trimesters respectively, and for the 2-month visit, α = 0.81. Scores were averaged across the two prenatal time points (M = 25.19, SD = 7.46, Range = 8–45) to derive a composite variable for prenatal stress.

Symptoms of maternal depression were assessed during the prenatal interviews at the end of the second and third trimesters and during the 2-month laboratory visit using the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II; Beck, Steer, & Brown, 1996). The BDI-II is a widely accepted self-report measure to assess the severity of depressive symptomatology. It has high reliability in a range of populations and high internal consistency and well-established construct validity (Sharp & Lipsky, 2002). Reliability of the scale was good, α = 0.88 and α = 0.86 for the second and third trimesters respectively, and for the 2-month visit, α = 0.88. Scores were averaged across the two prenatal time points (M = 15.45, SD = 7.71) to derive a composite variable for prenatal depression.

2.7 |. Assessment of autonomic reactivity and regulation

Toddler autonomic reactivity and regulation were assessed using a gentle arm restraint paradigm that is a widely used, well-validated measure of anger/frustration used to assess infant regulation and reactivity (Stifter & Braungart, 1995a, 1995b). In this paradigm, the child was presented and encouraged to play with an attractive toy for 30 s. The experimenter stood behind the child, placed her hands on the child’s forearms, moved them to the child’s sides, holding them there for 30 s, while maintaining a neutral expression (first negative affect trial). After the first trial, the child was allowed to play with the toy for 30 s followed by a second arm restraint (negative affect trial 2). The child was again allowed to play with the toy after the 30 s of arm restraint. The session was stopped at the caregiver’s request or if the child reached a maximum distress code, defined as the child reaching the highest intensity of negative affect of a full cry. This occurred for six toddlers (one nonexposed and five cigarette-exposed) who were not included in subsequent data analyses.

Recording of the autonomic data began once the toddler was observed to be in a stable, quiet, alert state which was induced by having the child watch a 3-min segment of a neutral videotape “Baby Einstein” (see Calkins, 1997). A five-channel Bioamp (James Long Company, Caroga Lake, & NY, 1999) recorded respiration and electrocardiograph (ECG) data. Disposable electrodes were triangulated on the child’s chest. A respiration bellows was placed at the bottom of the sternum (zyphoid process) to measure inspiration and expiration.

IBI Analysis software (James Long Company, Caroga Lake, & NY, 1999) processed the HR data and calculated RSA. HR samples, which were collected every 10 ms, were used to calculate mean HR. A level detector was triggered at the peak of each R-wave. The interval between sequential R-waves was calculated to the nearest millisecond. Data files of R-wave intervals were later manually edited to remove incorrect detection of the R-wave or movement artifacts that occurred in less than 2% of cases. The software computes RSA using respiration and interbeat interval data as suggested by Grossman (1983). The difference between maximum interbeat interval during expiration and the minimum interbeat interval during inspiration was calculated. The difference, measured in seconds, is considered to be a measure of RSA, and is measured twice for each respiration cycle (once for each inspiration and once for each expiration). The time for inspirations and expirations is assigned as the midpoint for each. The time for each arrhythmia sample is assigned as the midpoint between an inspiration time and an expiration time. The software synchronizes with respiration and is, thus, relatively insensitive to arrhythmia due to tonic shifts in heart rate, thermoregulation, and baroreceptor.

The average RSA was calculated for the 3-min baseline period and for each of the two negative affect tasks. Two RSA change scores, from the baseline to each of the two negative affect tasks, were calculated to assess autonomic reactivity. There was substantial variability in how quickly toddles reacted to the negative affect trial. Consequently, we chose to focus on reactivity during the second trial for these analyses. Negative scores indicate a decrease in RSA and are reflective of more optimal parasympathetic regulation.

3 |. ANALYTIC STRATEGY

We first examined associations among the different prenatal substance exposure variables, demographics, maternal psychological functioning, and child autonomic regulation using Pearson correlations or ANOVAs as appropriate. Prenatal substance exposure variables included the smoking group status variable that was a combination of all indices of PTE, the marijuana group status variable that was a combination of all indices of marijuana exposure, and the dose–response variables of the average number of cigarettes and marijuana per day. Analyses of potential confounds were conducted next using correlations or ANOVAs as appropriate.

Structural equations modeling (SEM) was used to test the hypothesized model with harsh parenting, maternal depression/stress, and maternal anger/hostility in early infancy as mediating variables between prenatal substance exposure and toddler RSA variables. Indirect effects were tested using the bias-corrected bootstrap method. This method provided a more accurate balance between Type 1 and Type 2 errors compared with other methods used to test indirect effects (MacKinnon, Lockwood, Hoffman, West, & Sheets, 2002). One thousand bootstrap draws and the 95% bias-corrected confidence intervals (CIs) were used to test significance of indirect effects.

Exploratory analyses1 examining potential interaction of pre- and postnatal exposure effects on toddler RSA regulation were conducted by including the interaction terms in the model. Multiple group analyses were used to examine potential moderation by child sex. Nested χ2 difference tests were used for model comparisons. All SEM analyses were conducted in Mplus 7.4 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2015).

3.1 |. Missing data

As expected in any longitudinal study, there were some incomplete data for some of the participants at one or more of the three assessment points included in this study. Of the 247 mother–infant dyads who completed the pregnancy and 2-month assessments, 9 were missing at 16-month assessments. 2There were no significant differences between families with complete versus missing on any of the variables included in this study and demographics at any age.

Missing data were accounted for using full-information maximum likelihood (FIML) estimation procedures, which can provide accurate parameter estimates and standard errors (Arbuckle, 1996).

4 |. RESULTS

4.1 |. Prenatal substance exposure, maternal psychological functioning, and toddler autonomic regulation

The first goal of the current study was to explore the preliminary associations among substance exposure, maternal psychological functioning (maternal depression/stress, anger/hostility), harsh parenting, and toddler autonomic reactivity/regulation. The control group had a highest percentage of ethnically minority mothers. As would be expected, mothers in the exposure groups had more smoking partners and used more tobacco both prenatally and postnatally, compared to those in the control group. Similarly, compared to the other two groups, PTME mothers used more cannabis both prenatally and postnatally. Children in both the PTME and PTE groups had higher tobacco exposure than the control group at 2 months of age. We note these in the Table 1 for descriptive purposes.

TABLE 1.

Group differences in substance exposure and demographics

| Non-smoking (control) | Tobacco only (PTE) | Tobacco & cannabis (PTME) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M/% | SD | M/% | SD | M/% | SD | F/χ2 | Partial η2 | Groups differed | |

| Demographics | |||||||||

| Maternal age | 24.45 | 5.02 | 24.90 | 5.19 | 23.81 | 4.77 | 0.78 | 0.01 | |

| Maternal years of education | 12.55 | 1.90 | 12.25 | 1.84 | 12.23 | 1.90 | 0.69 | 0.01 | |

| Maternal occupation | 2.13 | 1.63 | 2.24 | 1.80 | 1.95 | 1.43 | 0.72 | 0.01 | |

| Parity | 1.51 | 1.61 | 1.86 | 1.61 | 1.46 | 1.68 | 0.88 | 0.01 | |

| Race (% Minority) | 82.6% | 58.2% | 68.0% | χ2 = 10.30** | |||||

| Married/cohabiting | 53.6% | 49.4% | 37.1% | χ2 = 5.21 | |||||

| TANF | 13.8% | 13.8% | 15.5% | χ2 = 0.22 | |||||

| Medicaid | 65.2% | 64.5% | 69.1% | χ2 = 0.42 | |||||

| Food stamps | 52.2% | 52.5% | 56.7% | χ2 = 0.45 | |||||

| Partner smoking | 40.5% | 70.7% | 91.7% | χ2 = 21.87*** | |||||

| Prenatal exposurea | |||||||||

| # Joints/day across pregnancy | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.57 | 0.86 | 33.05 *** | 0.21 | Control & PTE vs. PTME |

| # Cigarettes/day across pregnancy | 0.00 | 0.00 | 4.28 | 4.61 | 5.56 | 4.63 | 42.27 *** | 0.26 | Control vs. PTE vs. PTME |

| Postnatal exposurea | |||||||||

| # Joints/day at 2 months | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.14 | 0.28 | 0.69 | 11.00 *** | 0.08 | Control & PTE vs. PTME |

| # Cigarettes at 2 months | 0.00 | 0.09 | 3.85 | 4.81 | 5.81 | 5.30 | 36.67 *** | 0.23 | Control vs. PTE vs. PTME |

| Infant cotinine at 2 months | 0.68 | 0.98 | 3.84 | 7.02 | 5.78 | 9.26 | 9.83 *** | 0.08 | Control & PTE vs. PTME |

TANF: Temporary Assistance to Needy Families.

Scores were skewed and homogeneity of variance across the three exposure groups were violated. Outlying scores were winsorized to 3 SD with rank order maintained, which alleviated both issues of skewness and heterogeneity of variance. ANOVAs were conducted using the transformed data.

p < 0.01.

p < 0.001.

As shown in Table 2, PTE and PTME mothers had higher anger/hostility than the control group both prenatally and postnatally. Similarly, mothers in both the exposure groups were more depressed and stressed than controls during pregnancy as well as postnatal period. Mothers used both tobacco and cannabis tended to demonstrate higher harsh parenting than those in the control group at 2 months of child age. There were no group differences in toddler RSA.

TABLE 2.

Group differences in harsh parenting, maternal psychopathology, and toddler autonomic regulation

| Non-smoking (Control) | Tobacco only (PTE) | Tobacco & cannabis (PTME) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | F | Partial η2 | Groups differed | |

| Maternal anger/hostility pregnancy | 2.41 | 0.76 | 2.82 | 0.80 | 2.89 | 0.79 | 7.88 *** | 0.07 | Control vs. PTE & PTME |

| Maternal depression/stress pregnancy | −0.27 | 0.90 | 0.14 | 0.93 | 0.07 | 0.85 | 4.42 ** | 0.04 | Control vs. PTE & PTME |

| Maternal anger/hostility postnatal | 2.08 | 0.78 | 2.58 | 0.80 | 2.58 | 0.78 | 10.08 *** | 0.08 | Control vs. PTE & PTME |

| Maternal depression/stress postnatal | −0.20 | 0.79 | 0.19 | 1.01 | −0.04 | 0.80 | 3.68 * | 0.03 | Control vs. PTE |

| Maternal harsh parenting | 1.14 | 0.27 | 1.23 | 0.36 | 1.31 | 0.57 | 2.95 * | 0.02 | Control vs. PTME |

| RSA baseline | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.11 | 0.00 | |

| RSA change | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.84 | 0.01 | |

Note. Maternal depression/stress used standardized scores.

AR: Arm Restraint; RSA: respiratory sinus arrhythmia.

p < 0.10.

p < 0.05.

p < 0.001.

Correlations among maternal psychological functioning and toddler RSA variables (Table 3) revealed that maternal psychopathology were moderately stable from pregnancy to 2 months after child birth. In addition, maternal harsh parenting at 2 months of child age was positively and concurrently associated with maternal depression/stress. Maternal harsh parenting was also associated with lower BRSA in 16-month-olds.

TABLE 3.

Correlations among maternal harsh parenting, maternal psychopathology, and toddler autonomic regulation

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Maternal anger/hostility pregnancy | — | ||||||

| 2. Maternal depression/stress pregnancy | 0.53 ** | — | |||||

| 3. Maternal anger/hostility postnatal | 0.62 ** | 0.43 ** | — | ||||

| 4. Maternal depression/stress postnatal | 0.42 ** | 0.63 ** | 0.50 ** | - | |||

| 5. Maternal harsh parenting | 0.13 * | 0.01 | 0.10 | 0.15 * | — | ||

| 6. RSA baseline | −0.08 | −0.01 | −0.05 | −0.13 | −0.15* | — | |

| 7. RSA change | 0.06 | −0.06 | 0.13 | −0.04 | 0.01 | −0.05 | — |

Note. Outlying scores were winsorized to 3 SD with rank order maintained. Given their severe skewness, the respiratory sinus arrhythmia (RSA) change scores were transformed into three meaningful categories: negative change compared to baseline RSA (BRSA), no change, and positive change. The categorizing was recoded as an ordinal category variable (1, 2, and 3) with higher scores indicating increased RSA relative to baseline. This ordinal category variable was also used in subsequent model testing.

p < 0.05.

p < 0.01.

4.2 |. Covariates

As noted above, there were more ethnically minority mothers in the control group than the PTE group (r = −0.16, p = 0.012) and race minority was also correlated with BRSA (r = 0.26, p < 0.001). Maternal age was associated with both maternal harsh parenting (r = −0.14, p = 0.038) and BRSA (r = 0.17, p = 0.021). Both race minority and maternal age were controlled for in subsequent model testing.

4.3 |. Model testing

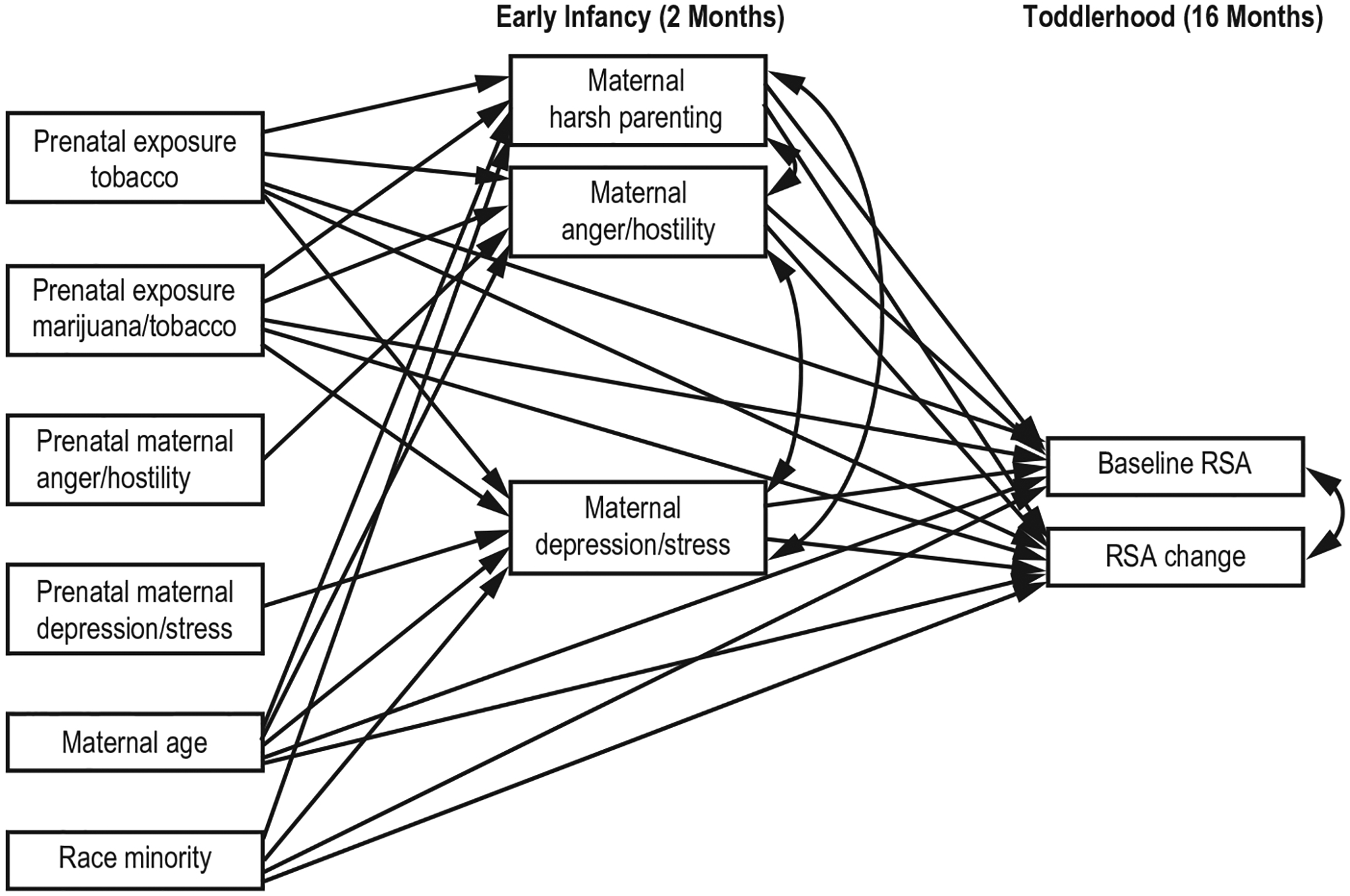

We tested the hypothesized model (Figure 1) in two steps. The first model (Model 1) included prenatal substance exposure and prenatal maternal depression/stress and anger/hostility as the exogenous variable, harsh parenting, depression/stress and anger/hostility in infancy (2 months) as mediators, and the two autonomic variables of BRSA and RSA change as the endogenous variables. Both maternal age and race minority were controlled for. The within time associations between harsh parenting and maternal psychology as well as that between toddler RSA regulation, were also examined.

FIGURE 1.

Hypothesized model

In developmental studies with longitudinal data, the presumption of the direct effects of predictors on outcomes no longer holds. During a developmental process, the effects of distal influences can diminish or even totally disappear, without the operating of more proximal mediators (e.g., Shrout & Bolger, 2002). Statistically, this notion is more explicable.

According to Hayes (2009), there is no such constraint that the size of c (the direct effect) would constrain the size of a (path between predictor and mediator) and b (path between mediator and outcome). In light of this, we estimated the indirect associations between prenatal substance exposure and toddler RSA regulation via harsh parenting and maternal psychopathology in Model 1. The potential direct paths between prenatal substance exposure and autonomic variables, were added in the next step (Model 2).

Model 1 fit the data adequately (Marsh et al., 2000), χ2(12) = 19.69, p = 0.073; CFI = 0.96; and RMSEA = 0.05 with 90% CI 0.00–0.09. Model 2 was then estimated. As the mean- and variance-adjusted weighted least squares estimator (WLSMV) were used in model testing, a correct Chi-square difference testing using the DIFFTEST option indicated that Model 2 did not fit the data better than Model 1, Δχ2 (4) = 1.86, p = 0.761. Thus, Model 1 was chosen as the final model.

As shown in Figure 2, maternal comorbid use of tobacco and marijuana during pregnancy was associated with higher harsh parenting in infancy and which in turn, was predictive of lower toddler BRSA. At a trend level, maternal comorbid use of tobacco and marijuana during pregnancy was also associated with higher postnatal anger/hostility at 2 months controlling for maternal anger/hostility in pregnancy. Maternal postnatal anger/hostility was associated with positive RSA change (increased RSA relative to baseline) in toddlers at 16 months of age. Maternal depression/stress at 2 months of child age was not related to either prenatal substance exposure or toddler RSA regulation. There was an indirect association between combined tobacco and marijuana exposure and toddler BRSA via harsh parenting, β = −0.02, 95% CI [−0.06, −0.01]. However, the indirect pathway through maternal postnatal anger/hostility to toddler RSA change was not significant, β = 0.03, 95% CI [−0.01, 0.17]. This model explained 15% of the variance in toddler BRSA and 7% of the variance in RSA change.

FIGURE 2.

Final model

5 |. DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study was to examine if PTE, and/or PTME were associated with autonomic regulation at 16 months of age after controlling for maternal age, race minority, and prenatal maternal psychosocial functioning, and if these associations between prenatal exposure and toddler reactivity/regulation were mediated by parenting or maternal psychosocial functioning during early infancy. Results from model testing indicated that there were no direct effects of any of the prenatal variables on regulatory processes at 16 months of age. Although numerous studies have found effects of PTE on neonatal neurobehavioral functioning and on behavior during middle childhood (Wakschlag, Pickett, Cook, Benowitz, & Leventhal, 2002; Willoughby, Greenberg, Blair, & Stifter, 2007), the effects of PTE later in infancy have been inconsistent. While some studies have found evidence of direct effects of PTE on behavior among infants and toddlers such as increased negative affect (e.g., Schuetze & Eiden, 2006), other studies have not found evidence of direct effects among toddlers or during early childhood (Lavigne et al., 2011; Schuetze, Eiden, Leonard, Huestis, & Colder, 2017). While these inconsistencies may be due to variations across studies in dose, timing and duration of exposure, the methods used to assess maternal smoking and the nature of the comparison groups, Lavigne et al. (2011) hypothesize that direct effects of smoking might not emerge until later in childhood. Others have pointed to the fact that the only consistent effects of PTE are on fetal growth and that other findings are the result of genetic liability associated with individual differences in maternal personality rather than direct effects of PTE on development (Massey et al., 2016).

Although there were no direct associations between prenatal exposure and regulatory processes at 16 months of age, harsh parenting during early infancy, mediated the association between PTME and BRSA. Toddlers who were prenatally exposed to both tobacco and marijuana experienced higher levels of harsh parenting which was, in turn, associated with less optimal baseline autonomic regulation. It is important to note that, although PTME was only marginally associated with maternal anger/hostility, toddlers who had mothers with higher levels of anger/hostility displayed less optimal autonomic reactivity during environmental challenge. These findings can be interpreted within the context of the neurobiological model of regulation which posits that mother–infant coregulation mediates the association between brainstem dysfunction due to pre and perinatal risks and child self-regulation (Geva & Feldman, 2008). Mothers with higher levels of anger/hostility and negative affect are likely to be less responsive, less positive during interactions and may spend less time in caregiving activities (Garstein, Bridgett, Young, Panksepp, & Power, 2013). Given the large body of literature indicating that higher levels of maternal harshness and maternal anger/hostility are associated with poorer regulation in children (Bradley & Corwin, 2007; Kochanska & Knaak, 2003; Maccoby & Martin, 1983), our findings provide empirical evidence supporting specific mechanisms by which prenatal exposure may impact behavior during the toddler years. Furthermore, these findings can be considered within the context of a vulnerability model which indicates that experiencing aspects of nonoptimal caregiving such as adverse maternal psychosocial functioning in the presence of substance exposure increases developmental vulnerability (Luther & Zelazo,). It is also important to note that there were no effects of maternal depression/stress on toddler autonomic reactivity or regulation. Although there is an extensive body of literature showing negative outcomes among young children of depressed mothers (Horwitz, Briggs-Gowan, Storfer-Isser, & Carter, 2009; Madigan, Moran, Schuengel, Pederson, & Otten, 2007; Martins & Gaffan, 2000), maternal depression is highly comorbid with maternal anger/hostility (Goodman & Gotlib, 1999; Marmorstein & Iacono, 2004; McCarty & McMahon, 2003). Thus, when we include both symptoms of maternal anger/hostility and maternal depression in the model, only maternal anger/hostility accounted for unique variance n toddler reactivity and regulation.

This study has several strengths and limitations. First, accurate assessment of substance use is difficult. Although care was taken in the present study to identify substance use in this sample, the accurate assessment of substance use is always difficult, particularly among pregnant women. Pregnant women are often hesitant to divulge information regarding the use of substances, including cigarettes and marijuana, during pregnancy. To address this issue, multiple indices of substance use were used including self-report using the reliable TLFB interview as well as maternal saliva and infant meconium samples. Each of these measures has its own limitations. However, when used in combination, they greatly increase the likelihood of accurately identifying prenatal cigarette smoking and other substance use. Moreover, they reflect different aspects of prenatal exposure (dose–response, timing, presence vs. absence). Although these findings highlight the importance of considering maternal psychological symptoms and parenting when examining child outcomes, the scope of this study did not permit us to consider an exhaustive list of psychiatric functioning. In particular, recent work has indicated a link between cigarette smoking and personality disorders (Zvolensky, Jenkins, & Goodwin, 2011) and, thus, future studies should consider other aspects of maternal psychological functioning.

We also did not have a group of women who use marijuana during pregnancy in the absence of tobacco. Thus, it is unclear if the effects of PTME in this study were specific to marijuana use during pregnancy or if marijuana and tobacco co-use during pregnancy has a symbiotic impact on development. Future studies should consider the inclusion of a PME only group to separate out the effects of PME from those of the combination of prenatal marijuana and PTE. Finally, another limitations is that the behavioral and physiological measures of infant regulation and reactivity was limited to a single, brief task and, thus, can only be generalized to this context. Although the behavioral measure was a standardized, objective, observation-based measure of reactivity and regulation that does not have the method biases associated with widely used maternal reports, future studies should explore pathways from prenatal influences to child reactivity/regulation in a wider range of contexts. Despite these limitations, our study had several strengths, including the use of multiple measures of child reactivity/regulation and prenatal substance exposure, the prospective measurement of maternal psychological symptoms and substance sue, the consideration of the combined effects of PTE and PME, careful control for alcohol exposure, and a demographically similar control group.

In conclusion, this study fills an important gap in the literature on PTE, PME, and regulation/reactivity during the toddler years, highlighting the role of maternal psychological symptoms and parenting as important intervening variables. Results suggest that interventions with this high risk sample of substance using mothers may focus on reducing symptoms of maternal anger/hostility as well as reducing prenatal substance exposure. Addressing both these aspects of maternal behavior may have a positive impact on the regulatory behaviors of these high risk toddlers.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the parents and children who participated in this study and research staff who were responsible for conducting numerous assessments with these families. Special thanks to Dr. Amol Lele for collaboration on data collection at Women and Children’s Hospital of Buffalo. Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse of the National Institutes of Health under award R01DA01963201. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Funding information

National Institute on Drug Abuse, Grant/Award Number: R01 DA 019632

Footnotes

The interactions between pre- and postnatal exposure in their prediction of toddler RSA functioning were not statistically significant. There were no sex differences in any of the model paths.

The results based on 238 cases were similar to those using 247 cases.

REFERENCES

- Allen AM, Prince CB, & Dietz PM (2009). Postpartum depressive symptoms and smoking relapse. American Journal of Preventative Medicine, 36, 9–12. 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.09.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almond D, & Currie J (2011). Killing me softly: The fetal origins hypothesis. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 25, 153–172. 10.1257/jep.25.3.153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ansell EB, Laws HB, Roche MJ, & Sinha R (2015). Effects of marijuana use on impulsivity and hostility in daily life. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 148, 136–142. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.12.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arbuckle JL (1996). Full information estimation in the presence of incomplete data. In Marcoulides GA, & Schumacker RE (Eds.), Advanced structural equation modeling: Issues and techniques (pp. 243–277). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Beauchaine T (2001). Vagal tone, development, and Gray’s motivational theory: Toward an integrated model of autonomic nervous system functioning in psychopathology. Development & Psychopathology, 13, 183–214. 10.1017/S0954579401002012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, & Brown GK (1996). Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory–II. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Blair C, Granger D, Willoughby M, & Kivlighan K (2006). Maternal sensitivity is related to hypothalmic-pituitary-adrenal axis stress reactivity and regulation in response to emotion challenge in 6-month-old infants. Annals of the New York Academy of Science, 1094, 263–267. 10.1196/annals.1376.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein M, & Suess P (2000). Physiological self-regulation and information-processing in infancy: Cardiac vagal tone and habituation. Child Development, 71, 273–287. 10.1111/1467-8624.00143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley RH, & Corwyn RF (2007). Externalizing problems in fifth grade: Relations with productive activity, maternal sensitivity, and harsh parenting from infancy through middle childhood. Developmental Psychology, 43, 1390–1401. 10.1037/0012-1649.43.6.1390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RA, Burgess ES, Sales SD, Whiteley JA, Evans DM, & Miller I (1998). Reliability and validity of a smoking timeline follow-back interview. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 12, 101–112. 10.1037/0893-164X.12.2.101 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Buss AH, & Perry M (1992). The aggression questionnaire. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 63, 452–459. 10.1037/0022-3514.63.3.452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calkins SD (1997). Cardiac vagal tone indices of temperamental reactivity and behavioral regulation in young children. Developmental Psychobiology, 31, 125–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calkins SD, & Hill A (2007). Caregiver influences on emerging emotion regulation: Biological and environmental transactions in early development. In Gross JJ (Ed.), Handbook of emotion regulation (pp. 229–248). New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Clark R (1999). The parent-child early relational assessment: A factorial validity study. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 59, 821–846. 10.1177/00131649921970161 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Kamarck T, & Mermelstein R (1983). A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 24, 385–396. 10.2307/2136404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis EP, Glynn LM, Waffarn F, & Sandman CA (2011). Prenatal maternal stress programs infant stress regulation. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychaitary, 52, 119–129. 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02314.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeGangi GA, DiPietro JA, Greenspan SI, & Porges SW (1991). Psychophysiological characteristics of the regulatory disordered infant. Infant Behavior & Development, 14, 37–50. 10.1016/0163-6383(91)90053-U [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eiden RD, Leonard KE, Colder C, Homish G, Schuetze P, Gray T, & Huestis MA (2011). Anger, hostility, and aggression as predictors of persistent smoking during pregnancy. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 72(6), 926–932. 10.15288/jsad.2011.72.926 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Spinrad TL, & Morris A (2011). Empathy-related responding in children. In Killen M, & Smetana JG (Eds.), Handbook of moral development (pp. 517–549). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Ruiz J, Berrendero F, Hernandez ML, & Ramos JA (2000). The endogenous cannabinoid system and brain development. Trends in Neuroscience, 23, 14–20. 10.1016/S0166-2236(99)01491-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fracasso MP, Porges SW, Lamb ME, & Rosenberg AA (1994). Infant temperament and cardiac vagal tone: Reliability and stability of individual differences. Infant Behavior and Development, 17, 277–284. [Google Scholar]

- Garstein MA, Bridgett DJ, Young BN, Panksepp J, & Power T (2013). Origins of effortful control: Infant and parent contributions. Infancy, 18, 149–183. 10.1111/j.1532-7078.2012.00119.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geva R, & Feldman R (2008). A neurobiological model for the effects of early brainstem functioning on the development of behavior and emotion regulation in infants: Implications for prenatal and perinatal risk. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 49, 1031–1041. 10.1111/j.1459-7610.2008.01918.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman SH, & Gotlib IH (1999). Risk for psychopathology in the children of depressed mothers: A developmental model for understanding mechanisms of transmission. Psychological Review, 106, 458–490. 10.1037/0033-295X.106.3.458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray T, Eiden R, Leonard K, Connors G, Shisler S, & Huestis M (2010a). Nicotine and metabolites in meconium as evidence of maternal cigarette smoking during pregnancy and predictors of neonatal growth deficits. Nicotine and Tobacco Research, 12, 658–664. 10.1093/ntr/ntq068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray TR, Eiden RD, Leonard KE, Connors GJ, Shisler S, & Huestis MA (2010b). Identifying prenatal cannabis exposure and effects of concurrent tobacco exposure on neonatal growth. Clinical Chemistry, 56(9), 442–450. 10.1373/clinchem.2010.147876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossman P (1983). Respiration, stress, and cardiovascular function. Psychophysiology, 20, 284–299. 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1983.tb02156.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harkany T, Guzman M, Galve-Roperh I, Berghuis P, Devi LA, & Mackie K (2007). The emerging functions of endocannabinoid signaling during CNS development. Trends in Pharmacological Science, 28, 83–92. 10.1016/j.tips.2006.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF (2009). Beyond Baron and Kenny: Statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. Communication Monographs, 76, 408–420. 10.1080/03637750903310360 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Horwitz SM, Briggs-Gowan MJ, Storfer-Isser A, & Carter AS (2009). Persistence of maternal depressive symptoms throughout the early years of childhood. Journal of Women’s Health, 18, 637–645. 10.1089/jwh.2008.1229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurd YL, Wang X, Anderson V, Beck O, Minkoff H, & Dow-Edwards D (2005). Marijuana impairs growth in mid-gestation fetuses. Neurotoxicology & Teratology, 27, 221–229. 10.1016/j.ntt.2004.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izard CE, Porges SW, Simons RF, Haynes OM, Hyde C, Parisi M, & Cohen B (1991). Infant cardiac activity: Developmental changes and relations with attachment. Developmental Psychology, 27, 432–441. 10.1037/0012-1649.27.3.432 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- James Long Company. (1999). IBI analysis system reference guide. Caroga, NY: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Jarvis M, Primatesta P, Erends B, Feyerabend C, & Bryant A (2003). Measuring nicotine intake in population surveys: Comparability of saliva cotinine and plasma cotinine estimates. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 5, 349–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jutras-Aswad D, DiNieri JA, Harkany T, & Hurd YL (2009). Neurobiological consequences of maternal cannabis on human fetal development and its neuropsychiatric outcome. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 259, 395–412. 10.1007/s00406-009-0027-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapoor A, Petropoulos S, & Matthews SG (2008). Fetal programming of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis function and behavior by synthetic glucocorticoids. Brain Research Reviews, 57, 586–595. 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2007.06.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochanska G, & Knaack A (2003). Effortful control as a personality characteristic of young children: Antecedents, correlates, and consequences. Journal of Personality, 71, 1087–1112. 10.1111/1467-6494.7106008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochanska G, & Thompson RA (1997). The emergence and development of conscience in toddlerhood and early childhood. In Grusec JE, & Kuczynski L (Eds.), Parenting and children’s internalization of values: A handbook of contemporary theory (pp. 53–77). New York, NY: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Lambers D, & Clark K (1996). The maternal and fetal physiologic effects of nicotine. Seminars in Perinatology, 20, 115–126. 10.1016/S0146-0005(96)80079-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavezzi AM, Ottaviani G, & Matturri L (2005). Adverse effects of prenatal tobacco smoke exposure on biological parameters of the developing brainstem. Neurobiology of Disease, 20, 601–607. 10.1016/j.nbd.2005.04.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavigne J, Hopkins J, Gouze K, Bryant F, Lebailly S, Binns H, … P. M. (2011). Is smoking during pregnancy a risk factor for psychopathology in young children? A methodological caveat and report on preschoolers. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 36, 10–24. 10.1093/jpepsy/jsq044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leech SL, Richardson GA, Goldschmidt L, & Day NL (1999). Preantal substance exposure: Effects on attention and impulsivity of 6-year-olds. Neurotoxicology and Teratology, 21, 109–118. 10.1016/S0892-0362(98)00042-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtensteiger W, Ribary U, Schiumpf M, Odermatt B, & Widemer HR (1988). Prenatal adverse effects of nicotine on the developing brain. Progress in Brain Research, 73, 137–157. 10.1016/S0079-6123(08)60502-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludman EJ, McBride CM, Nelson JC, Curry SJ, Grothaus LC, Lando HA, & Pirie PL (2000). Stress, depressive symptoms, and smoking cessation among pregnant women. Health Psychology, 19, 21–27. 10.1037/0278-6133.19.1.21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maccoby EE, & Martin JA (1983). Socialization in the context of the family: Parent-child interaction. In Mussen PH (Ed.), Handbook of child psychology (4th ed., p. 474). New York, NY: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman JM, West SG, & Sheets V (2002). A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychological Methods, 7, 83–104. 10.1037/1082-989X.7.1.83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madigan S, Moran G, Schuengel C, Pederson DR, & Otten R (2007). Unresolved maternal attachment representations, disrupted maternal behavior and disorganized attachment in infancy: Links to toddler behavior problems. Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry, 48, 1042–1050. 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01805.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mark K, Desai A, & Terplan M (2016). Marijuana use and pregnancy: Prevalence, associated characteristics, and birth outcomes. Archives of Women’s Mental Healthy, 19, 105–111. 10.1007/s00737-015-0529-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marmorstein NR, & Iacono W (2004). Major depression and conduct disorder in youth: Associations with parental psychopathology and parent-child conflict. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 45, 377–386. 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00228.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh HW, Ludtke O, Muthén B, Asparouhov T, Morin AJS, Trautwein U, … Gaffan EA (2000). Effects of early maternal depression on patterns of infant-mother attachment: A meta-analytic investigation. Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry, 41, 737–746. 10.1017/S0021963099005958 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martins C, & Gaffin EA (2000). Effects of early maternal depression on patterns of infant-mother attachment: A meta-analytic investigation. Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry, 41, 737–746. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massey S, Reiss D, Neiderhiser J, Leve L, Shaw D, & Ganiban J (2016). Maternal personality traits associated with patterns of prenatal smoking and exposure: Implications for etiologic and prevention research. Neurotoxicology & Teratology, 53, 48–54. 10.1016/j.ntt.2015.11.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarty CA, & McMahon RJ (2003). Mediators of the relation between maternal depressive symptoms and child internalizing and disruptive behavior disorders. Journal of Family Psychology, 17, 545–556. 10.1037/0893-3200.17.4.545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen BS (2000). Allostasis and allostatic load: Implications for neuropsychopharmacology. Neuropsychopharmacology, 22, 108–124. 10.1016/S0893-133X(99)00129-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller T, Smith T, Turner C, Guijarro M, & Hallet A (1996). A meta-analytic review of research on hostility and physical health. Psychological Bulletin, 119, 322–348. 10.1037/0033-2909.119.2.322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, & Muthén BO (1998–2015). M-plus user’s guide. Los Angeles, CA: Muthen & Muthen. [Google Scholar]

- Porges SW (1996). Physiological regulation in high risk infants: A model for assessment and potential intervention. Development and Psychopathology, 8, 43–58. 10.1017/S0954579400006969 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Porges SW, Doussard-Roosevelt JA, Portales AL, & Greenspan SI (1996). Infant regulation of the vagal “brake” predicts child behavior problems. A psychobiological model of social behavior. Developmental Psychobiology, 29, 697–712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson GA, Day NL, & Goldschmidt L (1995). Prenatal alcohol, marijuana, and tobacco use: Infant mental and motor development. Neurotoxicology & Teratology, 17, 479–487. 10.1016/0892-0362(95)00006-D [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart MK, & Bates JE (2006). Temperament. In Damon W, Lerner R, & Eisenberg N (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 3. Social, emotional, and personality development (6th ed., pp. 99–166). New York, NY: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Schuetze P, & Eiden RD (2006). The association between maternal smoking and secondhand exposure and autonomic functioning at 2–4 weeks of age. Infant Behavior and Development, 29, 32–43. 10.1016/j.infbeh.2006.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuetze P, Eiden RD, Leonard K, Huestis M, & Colder C (2017). Prenatal risk and infant regulation: Indirect pathways via fetal growth, prenatal stress and maternal aggression/hostility. Child Development, 10.1111/cdev.12801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuetze P, Lopez FA, Granger DA, & Eiden RD (2008). The association between prenatal exposure to cigarettes and cortisol reactivity and regulation in 7-month-old infants. Developmental Psychobiology, 50, 819–834. 10.1002/dev.20334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp LK, & Lipsky MS (2002). Screening for depression across the lifespan: A review of measures for use in primary care settings. American Family Physician, 15, 1001–1008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrout PE, & Bolger N (2002). Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods, 7(422), 445. 10.1037//1082-989X.7.4.422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidor A, Fischer C, Eickhorst A, & Cierpka M (2013). Influence of early regulatory problems in infants on their development at 12 months: a longitudinal study in a high-risk sample. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 7(1), 35– 10.1186/1753-2000-7-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slotkin TA (1992). Prenatal exposure to nicotine: What can we learn from animal models? In Zagon IS, & Slotkin TA (Eds.), Maternal Substance Abuse and the Developing Nervous System (pp. 97–124). San Diego, CA: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Slotkin TA, Orband-Miller L, Queen KL, Whitmore WL, & Seidler FJ (1987). Effects of prenatal nicotine exposure on biochemical development of rat brain regions: Maternal drug infusions via osmotic minipumps. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapy, 240, 602–611. 10.1016/0361-9230(87)90130-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith PH, Homish GG, Leonard KE, & Collins RL (2013). Marijuana withdrawal and aggression among a representative sample of U.S. marijuana users. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 132, 63–68. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.01.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, & Sobell MB (1995). Alcohol timeline followback users’ manual. Toronto, Canada: Addiction Research Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Stifter CA, & Braungart JM (1995a). The regulation of negative reactivity in infancy: Function and development. Developmental Psychology, 31, 448–455. 10.1037/0012-1649.31.3.448 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stifter CA, & Braungart JM (1995b). The regulation of negative reactivity: Function and development. Developmental Psychology, 38, 448–455. [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA, Office of Applied Studies). (2013). Results from the 2012 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Detailed Tables. Rockville, MD: SAMHSA, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. [Google Scholar]

- Suess PE, Porges SW, & Plude DJ (1994). Cardiac vagal tone and sustained attention in school-age children. Psychophysiology, 31, 17–22. 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1994.tb01020.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United States Department of Health and Human Services (USDHHS). (2014). The health consequences of smoking: 50 years in progress. A report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office of Smoking and Health. [Google Scholar]

- Velders FP, Dieleman G, Henrichs J, Jaddoe VWV, Hofman A, Verhulst FC, … Tiemeier H (2011). Prenatal and postnatal psychological symptoms of parents and family functioning: The impact on child emotional and behavioural problems. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 20, 341–350. 10.1007/s00787-011-0178-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Von Suchodoletz A, Trommsdorf G, & Heikamp T (2011). Linking maternal warmth and responsiveness to children’s self-regulation. Review of Social Development, 20, 486–503. 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2010.00588.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wakschlag LS, Pickett KE, Cook E Jr, Benowitz NL, & Leventhal BL (2002). Maternal smoking during pregnancy and severe antisocial behavior in offspring: A review. American Journal of Public Health, 92(6), 966–974. 10.2105/AJPH.92.6.966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteman M, Fowkes F, Deary I, & Lee A (1997). Hostility, cigarette smoking and alcohol consumption in the general population. Social Science & Medicine, 44, 1089–1096. 10.1016/S0277-9536(96)00236-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willoughby M, Greenberg M, Blair C, & Stifter C & The Family Life Investigative Group (2007). Neurobehavioral consequences of prenatal exposure to smoking at 6 to 8 months of age. Infancy, 12, 273–301. 10.1111/j.1532-7078.2007.tb00244.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zvolensky MJ, Jenkins EF, & Goodwin RD (2011). Personality disorders and cigarette smoking among adults in the United States. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 45, 835–841. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2010.11.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]